Abstract

Purpose

To demonstrate the use of anatomic MRI-visible 3D-printed phantoms and to assess process accuracy and material MR signal properties.

Methods

A cervical spine model was generated from Computed Tomography (CT) data and 3D-printed using an MR signal-generating material. Printed phantom accuracy and signal characteristics were assessed using 120 kVp CT and 3 Tesla MR imaging. The MR relaxation rates and diffusion coefficient of the fabricated phantom were measured and 1H spectra were acquired to provide insight into the nature of the proton signal. Finally, T2-weighted imaging was performed during cryoablation of the model.

Results

The printed model produced a CT signal of 102±8 HU, and an MR signal roughly 1/3rd that of saline in short-TE/short-TR GRE MRI (456±36 versus 1526±121 arbitrary signal units). Compared to the model designed from the in vivo CT scan, the printed model differed by 0.13±0.11 mm in CT, and 0.62±0.28 mm in MR. The printed material had T2~32 ms, T2*~7 ms, T1~193 ms, and a very small diffusion coefficient less than olive oil. MRI monitoring of the cryoablation demonstrated iceball formation similar to an in vivo procedure.

Conclusion

Current 3D printing technology can be used to print anatomically accurate phantoms that can be imaged by both CT and MRI. Such models can be used to simulate MRI-guided interventions such as cryosurgeries. Future development of the proposed technique can potentially lead to printed models that depict different tissues and anatomical structures with different MR signal characteristics.

Keywords: T2 decay, T1 decay, CPMG, multiexponential, phantom, 3D Printing, Image-Guided Therapy

Introduction

Additive manufacturing, more broadly known as three-dimensional (3D) printing has been employed sporadically for medical applications since the late ‘90s (1). Its roots lie in skeletal radiology, where there is a more than 20-year history of applications in cranio-maxillofacial reconstruction (2,3). As 3D printing technologies have matured in terms of equipment, software and cost, they are now being integrated into medical practice, rapidly transitioning from niche applications to more routine utilization particularly in reconstructive surgeries but also in complicated cardiovascular and neuro-interventions (1).

There have been very few applications of 3D printing in MRI to date. The earliest is by Markl et al. who 3D-printed a phantom of a patient’s thoracic aortic vasculature (4) to enable in vitro time-resolved MR velocity-encoded hemodynamic experiments for vascular pathology variations. More recently, Hermann et al. printed a customized radiofrequency receiver coil housing platform and fixation device that enabled MRI of the mouse brain with reduced motion artifact (5). For such applications, the 3D-printed phantom is either not desired to have an MR signal (e.g., custom MR-compatible accessories), or, an MR signal is irrelevant to the use of the model (e.g., flow experiments).

The foremost envisioned use of “medical 3D printing” is to enable personalized precision interventions, namely interventions planned and simulated on a patient’s specific anatomy prior to the surgeon entering the operating room. This confers the ability to identify high-risk areas and anticipate potential complications, determine the need for specialty surgery assistance and communicate the surgical approach amongst a team before a procedure begins. These benefits can potentially lead to improved patient outcomes and reduced healthcare costs (1).

Achieving these benefits for MRI-guided minimally invasive interventions is a particular challenge; it necessitates not only the ability to print anatomically precise phantoms from clinical images, but also to provide materials that possess an MRI signal. There have been no reports of directly 3D-printing a phantom visible by MRI to date. Menikou et al. 3D-printed the skull bone from a computed tomography (CT) scan in acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) plastic using a fused deposition material 3D printer and filled it with a doped agar gel for the simulation of MRI-guided focused ultrasound ablations. This yielded a model with no signal in the printed skull bone, and homogeneous signal in the agar-filled skull cavity with an estimated T2 of 66 ms and T1 of 852 ms that could be used for MR thermometry (6). Such an approach, i.e., 3D-printing a “negative” mold in which to cast-mold a substance with an abundance of water hydrogen protons such as agarose is straightforward for simpler geometries with piecewise homogeneous components. Stiffer phantoms can be similarly produced using polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) as a basis.

Ideally, one would be able to directly 3D-print a complex anatomic model that would possess an MRI signal. If the process can additionally yield models with different MRI signal characteristics at prescribed locations corresponding to the different tissues involved in the pathology, for example a tumor printed with a different T2 and/or T1 relaxation time than the tissue it invades so that each may be differentiated in the MR images of the phantom, its usefulness would be potentially further increased.

Material jetting is a high-resolution 3D printing technology used extensively in medical applications (1). It can print models of arbitrarily complex anatomy either in a single material or using mixtures of a few base materials at prescribed locations so as to achieve a prescribed combination of e.g., durometer (hardness) and color of the base materials. The technology can potentially be similarly used to print models containing different MR signal intensities if one or more of the base material can generate an MR signal. The primary purpose of this work was to assess whether materials used in this 3D printing technology can generate an MRI signal. Having identified one such material, we used it to print a model of a diseased human cervical spine. We determined the accuracy of the printed model, characterized the printed material CT and MR signal properties, and explored the mechanism that enables the MR signal generation. Finally, we performed a cryoablation used for head, neck and spine tumor cryotherapy treatments (7) in this model, and monitored the procedure with MRI.

Methods

3D Printing Material

Material jetting uses liquid photo-reactive resins that undergo polymerization when subjected to typically ultraviolet light (1). Vat photopolymerization (also known as stereolithography) is a related 3D printing technology that uses the same photo-reactive chemistry, although is limited to single-material printing by printer design. We tested 17 materials, both flexible and rigid, and both transparent and opaque in those two printer categories (Supporting Table S1). A single material produced an MR signal, including with the use of ultra-short echo time sequences, with sufficient intensity to motivate more detailed studies of its signal properties. The material (Objet High Temperature RGD525 (8), Stratasys) is intended to simulate the thermal performance of engineering plastics. The major components of the tested compounds in resin form (15% by weight or more) are acrylic monomers and/or acrylic oligomers with some compounds also having substantial quantities of 2-propenoic acid, 1,7,7 trimethylbicyclo[2.2.1]hept-2-yl-ester or isobornyl acrylate. The RGD-525 compound contains primarily two types of acrylic monomers and isobornyl acrylate. Among its minor constituents (< 2% by weight) was a naptha, petroleum, light aromatic solvent (Chemical Abstract Service Registry Number 64742-95-6) which was not listed in any of the other compounds studied.

Phantom

A cervical spine with a C7 right pedicle osteoid osteoma was imaged with a 64×0.625 mm detector row computed tomography scanner (LightSpeed VCT, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI) at a gantry rotation time of 0.8 sec, spiral pitch of 5.8, 120 kVp tube voltage and 255 mA current. Images were reconstructed at 2.5 mm slice thickness with 0.625 mm spacing, using the manufacturer’s standard body filter convolution kernel. A 3D-printable model of the C6 to C8 vertebrae inclusive of the bone tumor was created from this scan by segmentation of the CT images using the bone segmentation algorithm of a commercial post-processing workstation (Vitrea 6.7, Vital Images, Minnetonka, MN). The segmentation was exported directly from the workstation as a printable standard tessellation language (STL; also known as stereolithography) file and was subsequently post-processed, including remeshing, light smoothing and trimming using the 3-matic additive manufacturing software (Materialise NV, Leuven, Belgium). The processed model was printed on an Objet 500 (Stratasys) printer in the RGD-525 material. CT multiplanar images with an overlay of the segmentation are shown in Figure 1. The final STL model and printed phantom are shown in Figure 2.

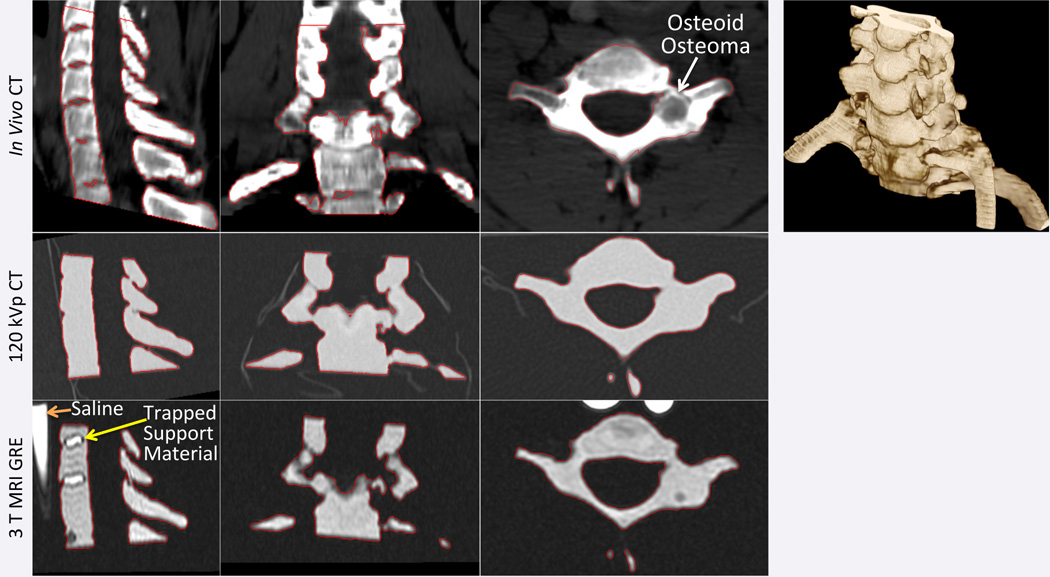

Figure 1.

Source CT images and volume rendering (top row) of cervical spine with a C7 right pedicle osteoid osteoma (white arrow in axial plane) show the segmentation used to produce the STL model (red outline in source images). CT (middle row) and MR (bottom row) images of the printed phantom are shown at matching planes with the segmentation of the phantom from each modality also outlined. Trapped support material in certain regions in between vertebrae that were enclosed by bone are visible in the printed model with MRI but not CT.

Figure 2.

STL model of a spine created from a patient’s non-contrast CT cervical spine examination and printed using an MRI-visible material with a high-resolution material jetting 3D printer.

Imaging Equipment

MR relaxometry, diffusion and high resolution 3D imaging experiments of the printed phantom were performed on a 3 Tesla GE HDx scanner (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI) using an 8-channel phased array head coil for radiofrequency (RF) signal reception. 1H spectra were acquired on a 3 Tesla Siemens Trio scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) using a 32-channel head coil for RF reception. A cryoablation performed in the model was monitored with a Siemens 3 Tesla Verio scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) using the chest phased array coil for RF reception with automated coil element selection. Finally, a CT scan of the phantom was acquired with a positron emission tomography (PET)/CT device with 40×1.2 mm detector rows (Biograph40, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany).

Comparison of Phantom by MR & CT Imaging vs Designed Model

The CT scan of the phantom was performed at 120 kVp, 18 mA and 0.5 sec rotation time. Images were reconstructed at 1.5 mm thickness with 0.5 mm spacing using the manufacturer’s sharp convolution kernel (B50f) (Figure 1). The high-resolution 3D MRI scan of the phantom was performed with a gradient recalled echo (GRE) sequence using a 16 cm field of view (FOV), 2 mm slice thickness, 160×160×88 matrix, 1.5/3.6 ms echo/repetition times, 8° flip angle, and ±20 kHz bandwidth (Figure 1). Two syringes filled with saline were placed in the scan FOV to enable assessment of relative signal magnitudes.

An STL model was derived by segmentation of the resulting images of the printed phantom from each modality. For the CT scan, the STL model was derived using the same segmentation algorithm as the in vivo scan. For the MRI scan, the model was derived using the thresholding algorithm in Mimics version 17.0 (Materialise NV), with a segmentation range of 90 to maximum (2558) signal intensity units, which sufficed to capture the phantom and avoid the noise. No further post-processing was applied to these STL models.

The CT- and MR-derived STL models were subsequently registered to the original STL model designed from the in vivo scan. Registration was performed in 3-matic (Materialise NV) initially using the “N-point” alignment algorithm (rigid transformations) with 8 manually-picked points followed by an automated “global registration” algorithm (parameters: 4 mm distance threshold, 10 iterations, 15% subsampling) for fine registration. The shortest distance between each vertex of the registered STL models to the surface of the original STL model was computed using the same software (“part comparison analysis” algorithm) and exported as a scalar field for analysis.

MR & CT Imaging Measurements

Fifteen regions-of-interest (ROI) were placed in CT and MR images of the phantom to establish the CT Hounsfield Units (HU) and MR signal amplitude of the printed material. In MR images, 10 ROIs were additionally placed in the saline-filled syringes, and another 10 in regions containing support material trapped within the printed phantom (Figure 1). Support material for the particular 3D printer used is a water-soluble material deposited by the 3D printer underneath any overhangs of the model being printed in order to support them, since a printer cannot deposit a layer of material atop empty space. The spine model contained empty spaces in between the vertebrae that required the use of such support material but that were fully enclosed by bone and thus could not be removed by the cleaning process subsequent to printing (Figure 1).

MR Relaxation and Diffusion Properties

The sequences and parameters used to measure transverse and longitudinal relaxation rates and the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) of the printed phantom are provided in Table 1. T2 measurements were first performed with a 3D non-selective multi-echo Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) sequence designed to minimize echoes from indirect and stimulated echo pathways (9,10). A total of 16 echoes with 5.8 ms echo spacing were acquired from this experiment. A second set of T2 measurements were performed using a single-echo spin echo 2D imaging sequence. The sequence was repeated to acquire 8 echo times. T2* relaxation measurements were performed using a multi-echo GRE sequence with 8 equally-spaced echoes from 2.4 to 24.4 ms. T1 measurements were performed using a single-echo spin echo sequence repeated for 9 repetition times ranging from 50 ms to 4 sec (Table 1). Finally, diffusion coefficient measurements were performed with a line scan diffusion sequence (11,12) at 8 evenly spaced diffusion weightings (b-factors) between 5 and 5,000 s/mm2 (δ=34.8 ms, Δ=44.4 ms) and between 5 and 50,000 s/mm2 (δ=67.2 ms, Δ=75.5 ms) along three orthogonal diffusion encoding directions. For this experiment, one syringe containing olive oil and one containing saline were included in the scan FOV.

Table 1.

Pulse sequences and their parameters used in MR relaxometryand diffusion experiments.

| Sequence | Flip Angle (°) |

FOV (cm) |

Matrix | Slice thickness/ Spacing (mm) |

TE (ms) [# echoes/echo spacing (ms)] |

TR (ms) | BW (kHz) |

NEX | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2 | 3D CPMG | 90x/90x− 180y−90x |

14×9.8×16 | 96×68×80 | 2/NA | 5.8–92.7 [16/5.8] |

800 | ±62.5 | 1 | |

| T2 | Single-echo Spin Echo | 90x/180y | 13 | 128×128 | 2/3 | 8–52.2 [8/5.8*] |

800 | ±62.5 | 3 | |

| T2* | Multi-echo Fast GRE | 30 | 18 | 128×128 | 2/3 | 2.4–24.4 [8/3.144] |

800 | ±62.5 | 2 | |

| T1 | Single-echo Spin Echo | 90x/180y | 11 | 128×128 | 2/3 | 9 | 50–4000§ | ±31.25 | 4–16¶ | |

| Diffusion | Line scan Spin Echo |

5–5,000 s/mm2 |

90x/180y | 12×9 | 128×96 | 5/4 | 88 | 3200 | ±7.8 | 1 |

| 5–50,000 s/mm2 |

20×10 | 128×64 | 8/4 | 150.7 | ||||||

The first echo spacing was 3.6 ms (i.e., 11.6 ms TE), 5.8 ms thereafter.

Intermediate TR times acquired were 100, 250, 500, 750, 1000, 2000, and 3000 ms.

NEX was progressively increased for increasingly short TR acquisitions.

The average signal observed in ROIs for each experiment was analyzed to yield the respective parameter by fitting to an appropriate, idealized signal model. R2 and R2* rates were obtained by fitting to the mono-exponential model , where R2 or R2* the relaxation rate, t the echo times, and α a constant (reflecting the spin density and sequence characteristics). For the 3D CPMG experiment, a bi-exponential signal model, , where α and β are constants corresponding to the relative signal fractions of the two components was additionally fitted to the data. R1 was obtained by fitting to the model s(t) = k(1 − e−tR1), where t the experiment repetition times and k a constant as before (13). The diffusion coefficient was measured by fitting the geometric mean of the diffusion signals measured along the three orthogonal diffusion encoding directions to the model s̄(b) = me−Db, where D the diffusion coefficient, b the acquired b-values and m a constant. All fits were performed using iterative non-linear optimization routines implemented in Matlab R2008b (Mathworks, Natick, MA) or the C programming language (diffusion experiments). Mean values of each fitted parameter were derived by averaging the individual values fitted in each of 10–15 ROIs per experiment.

1H Spectroscopy

1H spectra of the printed material were acquired at 3 echo times (30, 144, and 288 ms) using a single voxel point resolved spectroscopy (PRESS) sequence with a 1.5 s TR, voxel volume of 1.2 × 1.2 × 1.2 cm3 and 96 signal averages. Raw data was Fourier transformed and phased using vendor-supplied software to obtain absorption mode spectra.

MRI monitoring of Cryoablation

A tract was drilled to the C7 right pedicle of the printed phantom using standard instrumentation and a 17-gauge IceSeed (Galil Medical, Minneapolis, MN) Argon gas-based cryoprobe was advanced through the tract. A 15 min freeze cycle was performed during which intermittent sagittal T2-weighted turbo spin echo images were acquired. The sequence and parameters (103 ms/4.4 sec TE/TR, 27 echo train length, 2 signal averages, 28 cm FOV, 256×163 matrix, 2 mm slice thickness, ±32 kHz bandwidth) matched those used to monitor MRI-guided spine cryoablations at our institution (7). Images of the iceball formation during the phantom procedure were retrospectively visually compared with those of the patient’s procedure.

Statistical Analysis

Average CT and MRI signal intensities are reported as mean and standard deviation. Differences between MRI signal intensities of the printed material versus that of support material were compared using the unpaired Student t-test. The distances between the CT- and MRI-derived STL models of the imaged phantom to that designed from the patient images were summarized by the mean and standard deviation and compared using the unpaired Student t-test. For the 3D CPMG data, where both a mono- and a bi-exponential signal model were fitted, the F-test was used to determine if any reduction in χ2 was statistically significant relative to the differences in degrees of freedom for each of the fits (9,14). Here, a statistically significant p value implied that a bi-exponential fit is statistically more appropriate than a mono-exponential fit. Comparison of mean fitted T2 decay times measured with the CPMG versus the single echo spin echo experiments was performed using the unpaired Student t-test. For all tests, a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Volumetric CT and MR Imaging and Model Accuracy

The average attenuation of the printed model in 120 kVp CT images was 102.4±7.54 HU. There was no visible difference between the HU of the printed material compared to the support material trapped within the model (Figure 1), indicating similar electron densities. Mean signal intensity in the 3D GRE MR images was 455.7±35.6, while that of the support material was 733.8±91.9 (t-test p<0.0001; Figure 1) and that of saline was 1526.1±121.3 (t-test p<0.0001).

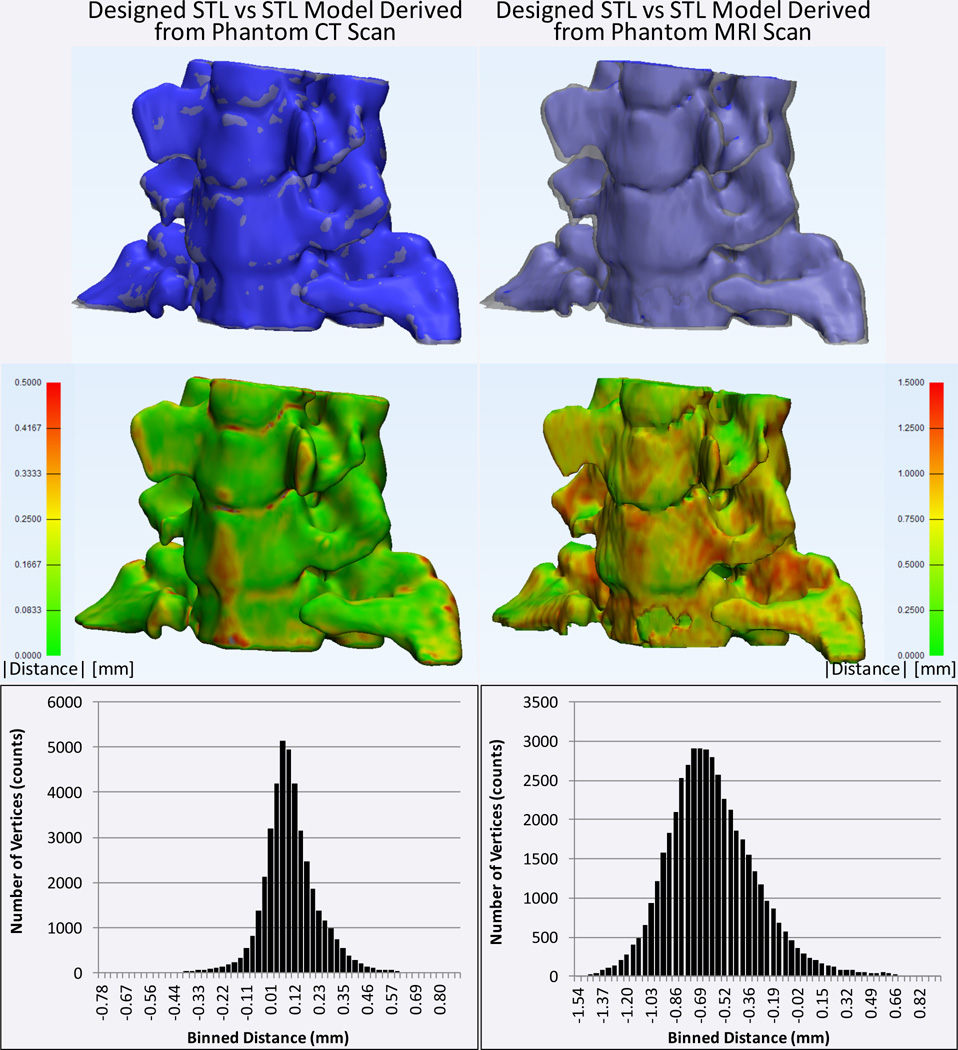

The average absolute and signed distance (i.e., difference) between the designed model and that derived from CT imaging of the printed phantom was 0.127±0.107 mm and 0.102±0.132, respectively. The average distance to the model derived from the MR images was statistically significantly larger, at 0.622±0.275 mm and −0.606±0.309 mm, for the absolute and signed distances respectively (p<0.0001 for both compared to corresponding CT distances; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of STL models obtained by segmentation of CT (left column) and MRI (right column) scans of the printed model to that initially derived from the patient CT images. Top row: the CT- and MRI-derived models are shown in blue and the STL model designed from the patient scan is shown in translucent gray. Middle row: absolute distance between the designed model and the models derived from the CT and MRI of the phantom are shown color-coded (green=0 mm to red≥1.5 mm). Bottom row: histograms of the minimum unsigned distances from each vertex of the original model to the surface of the models derived from the CT and MRI of the phantom.

MR Relaxometry, Diffusion and Spectroscopy

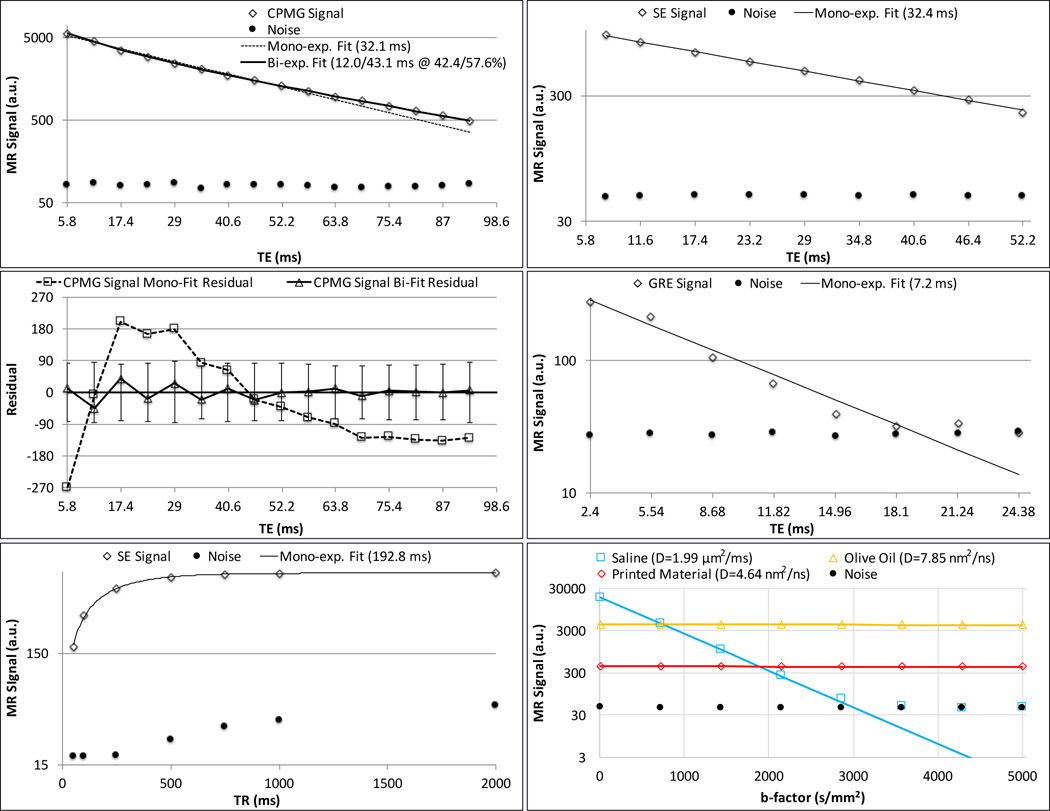

The CPMG data was statistically significantly better-fit by a bi-exponential model (minimum F-ratio 14.2, Table 2) with a fast-decaying component of T2=14.3±3.3 ms and a slower-decaying component of T2=45.5±6.1 ms (Figure 4). The two components were in roughly equal proportion (Table 2). The single echo spin echo data was adequately fit by a mono-exponential decay with a T2 of 32.8±0.2 ms (Figure 4) that was not significantly different than the mono-exponential fit to the CPMG data (T2=31.8±2.9 ms, t-test p=0.206). The T2* and T1 of the printed material were 7.2±0.5 ms and 193.5±2.2 ms (Figure 4; Table 2), respectively.

Table 2.

Printed material relaxation times.

| Mono-exponential Analysis | Bi-exponential Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relaxation Time [ms] | Relaxation Time [ms] | Long Component % |

F-ratio Mean, [range] |

||

| Short | Long | ||||

| 3D CPMG T2 | 31.8±2.9 | 14.3±3.3 | 45.5±6.1 | 52.7±15.4 | 111.0 [14.2–287.3] |

| SE T2 | 32.8±0.2 | ||||

| T2* | 7.2±0.5 | ||||

| T1 | 193.5±2.2 | ||||

Figure 4.

MR characteristics of the 3D-printed material at 3 T. Left panel: multi-echo CPMG signal with mono- and bi-exponential T2 fits (top row) and residuals for each T2 fit (middle row); single echo spin echo signal with mono-exponential T1 fit (bottom row, data not shown from 2 to 4 sec TR for clarity, see Table 1). Right panel: Single echo spin echo signal with mono-exponential T2 fit (top); multiple gradient recalled echoes with mono-exponential T2* fit (middle); and, line scan diffusion weighted signal with mono-exponential ADC fit for printed material, saline and olive oil (bottom). Filled circles in each plot indicate average noise signal in an empty space ROI. For CPMG fit, F-ratio is 279.7, indicating the bi-exponential fit to be more appropriate. Vertical error bars about the zero line in CPMG residual plot indicate the average noise signal.

There was a lack of any consistent decrease of signal with b-factor over both the initial 5–5,000 s/mm2 (D=4.64±0.74 nm2/ns, Figure 4) and the extended (5–50,000 s/mm2, D=−1.6±0.31 nm2/ns) b-factor ranges employed. This indicated an extremely small or non-existent diffusion coefficient compared to the very low ADC of oil, which was successfully measured at both the short and extended b-factor ranges (7.85±0.20 nm2/ns and 7.55±0.04 nm2/ns, respectively) i.e., coefficients in agreement with previously reported values (15,16).

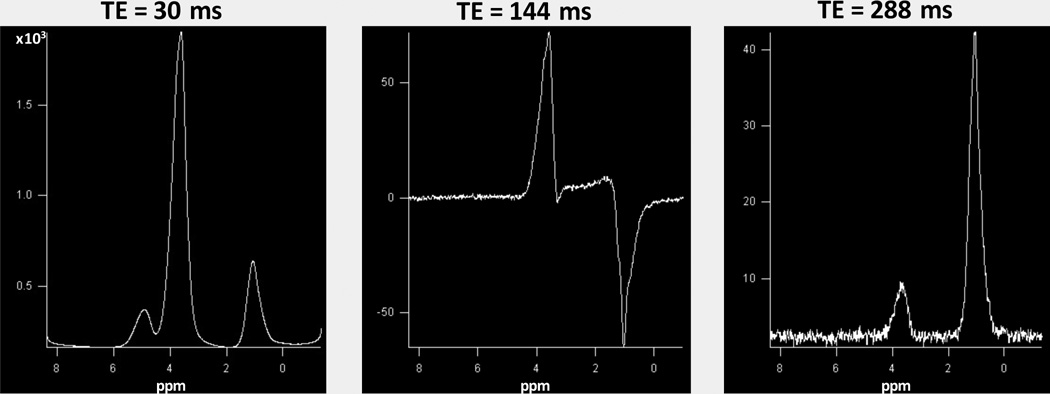

1H spectra at the three echo times are shown in Figure 5. As the sample was interrogated without a reference, zero ppm was set based on previous literature of similar compounds (17–20), with the peak furthest to the right at ~1.0 ppm (see Discussion). Two major resonances were observed at all three TEs (~1.0 and ~3.5 ppm). A smaller resonance was also seen (~3.7 ppm) only in the TE=30 ms spectrum. At 30 ms TE, all three resonances could be phased upright. At TE=144 ms, using phase settings similar to the 30 ms spectra, the resonance at ~3.5 ppm is upright while that at ~1.0 ppm is inverted. At TE=288 ms, the two primary resonances could be phased upright again, but with the resonance at ~3.5 ppm now being smaller than that at ~1.0 ppm, in contrast to the 30 ms TE spectra where the former dominated.

Figure 5.

1H spectra of the printed material acquired with a single-voxel PRESS sequence at three different echo times. The zero ppm reference is based on literature values of the first resonance of similar compounds (see text). The two major resonances (~1.0 and ~3.5 ppm) are seen to be phased upright at 30 and 288 ms while at 144 ms TE the resonance at ~1.0ppm is inverted.

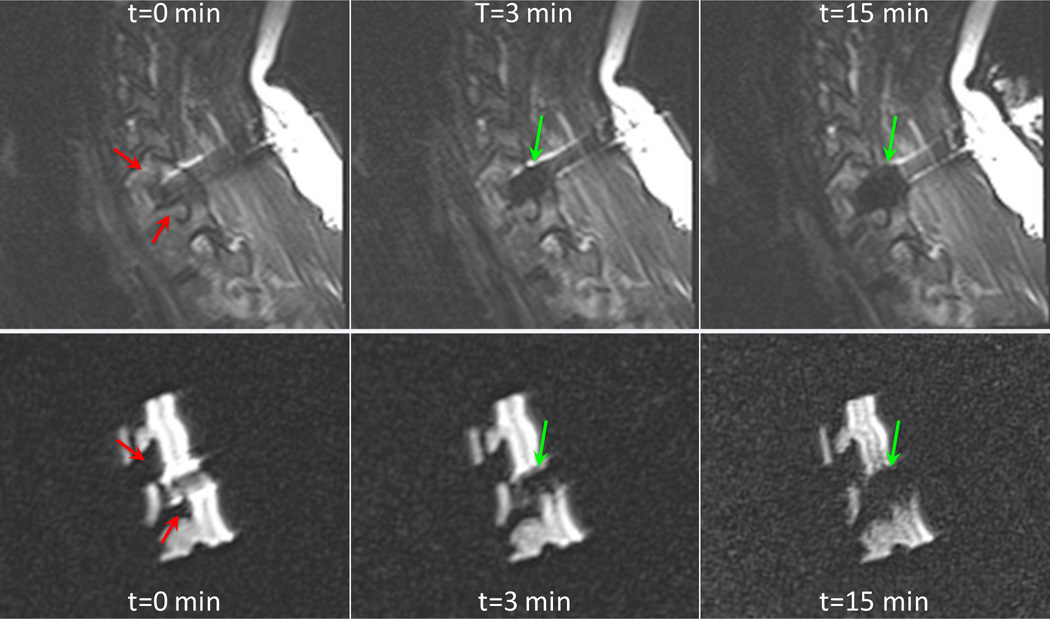

Phantom Cryoablation

Monitoring images are shown in Figure 6 at three time points, contrasted with images at similar time points in the first freeze cycle of the patient procedure. Similar ellipsoidal cryoablation zone expansion was observed in the model as in the patient.

Figure 6.

Sagittal fast spin echo T2-weighted images (TE=103 ms, TR=4370 ms) of the patient and 3D-printed model undergoing cryoablation at t=0 min, 3, and 10 min. Expansion of an ellipsoidal cryoablation zone is indicated by green arrows and neural foramina indicated by red arrows.

Discussion

3D-printable materials can be seen by X-ray imaging modalities including CT and fluoroscopy that are often used to guide minimally-invasive interventions such as endovascular procedures (21,22). However, to date no technique has been presented to 3D-print an anatomical model that produces an MR signal. The overall goal of this work was to 3D-print arbitrarily complex anatomical models derived from in vivo imaging that could be imaged with MRI. Such models may offer the opportunity to simulate and test MRI-guided interventions such as focused ultrasound, laser, microwave and RF, and cryotherapy focal ablations that have diverse applications including the treatment of brain lesions (23), head, neck and spine tumors (7) and prostate cancer (24). The ability to 3D-print materials visible by MRI could also potentially become important for the non-invasive monitoring of patient-specific printable implants that are now being developed (25). We discovered a single material in the photo-curable resin material category (1) that possesses an MRI signal after photopolymerization. The material had a reasonable T2 of ~32 ms, a short T2* of ~7 ms, and a short T1 of 193 ms. The shorter T2* than T2 indicates the presence of non-negligible internal susceptibility gradients, most probably due to small air/polymer interfaces. These characteristics certainly allow it to be used for many MR applications.

The precise chemical composition of the material is proprietary and thus the source of the MR signal, while of significant interest for developing and optimizing future MRI applications, is unknown. The particular material in resin form contained two types of acrylic monomers and isobornyl acrylate plus a <2% by weight petroleum naphtha which was not listed in any of the other compounds studied. Whether the inclusion of this minor component resulted in polymers having some protons with sufficient mobility to escape substantial dipolar broadening and ultra-short T2 values affecting all other materials tested is an interesting, if unresolved question. The proton spectroscopic studies offer some insight into the nature of the observed signal. Based on previous high-field literature of similar compounds (17–20), we speculate that both major resonances arise from methyl (CH3) groups, with the group at ~3.5 ppm bonded to oxygen, and the group at ~1.0 ppm bonded to a carbon with a methine proton providing J-coupling similar to lactate for the CH3 group, accounting for the inversion at a TE of 144 ms for this resonance (c.f., Figure 5). Any doublet structure that might be expected as a consequence of this coupling is most probably washed out by a combination of dipolar line broadening, small chemical shifts among the CH3 groups, and susceptibility-induced broadening due to air/polymer interfaces. NMR spectra of similar compounds, including copolymers of isobornyl – acrylate-methyl methacrylate have indicated a ~2.5 ppm difference between these two methyl groups with the carbon-bonded methyl groups assigned to the 1.0 ppm region (17–20), motivating our choice of ppm scale. It is further reasonable to assume that the signal observed from the material is from methyl groups whose spinning about the bond axes most likely reduces dipolar broadening, leaving T2 values sufficiently long to allow for detection at typical imaging TEs.

The diffusion experiments discount any translational diffusion of these groups over the typical time scales probed with standard ADC measurements, leaving us to surmise that only rotational motions decrease dipolar broadening sufficiently for signal detection with the imaging sequences we have applied. The biexponential CPMG decay curve observed from magnitude image data may reflect a longer T2 for the carbon-bonded methyl group versus the oxygen-bonded methyl group since the former is larger than the latter in the 288 ms TE spectra, reversing their relative sizes compared to the 30 ms TE spectra. Nonetheless, without more detailed information regarding the chemical composition, beyond that provided in the manufacturer safety data sheets, these spectral assignments are speculative.

Assuming the signals are due to the methyl groups posited, the experiment with the liquid nitrogen cryoablation probe demonstrates that low temperatures suffice to slow the rotational motion of these groups enough to drastically shorten T2 (and probably lengthen T1) to produce “iceball” features similar to those observed from the water signal in tissue undergoing cryoablation. This renders the material potentially attractive for testing patient-specific cryosurgery plans, e.g., to ensure using intra-procedural MRI that the ablation zone does not extend to tissues that should not be ablated, such as a compressed nerve in a neural foramen. Although the material thermal properties are likely homogeneous, not variable as in a patient, the cryoablation zone in our experiment approximated that in the patient’s bone (c.f., Figure 6), where it grows to an approximately ellipsoidal shape with a predictable, fixed size. Significant deformation of the cryoablation zone can occur if there are heat sinks nearby, such as the carotid artery. However, with 3D printing, flow channels can be printed in a model to incorporate physiologic flow for more complex simulations as necessary.

For any medical application, fidelity of the printed model with respect to the designed model is of paramount importance. The cervical spine model we printed was anatomically accurate in comparison to that designed from the in vivo images given the imaging parameters used to ascertain its accuracy. The average difference from the designed model according to CT (~0.13 mm) was just over 1/3rd of the resolution of modern CT scanners (0.35–0.5 mm in plane, 0.5–0.625 mm slice thickness). Similarly, although the difference according to MRI was significantly larger (~0.62 mm), it was still less than 2/3rds of the imaging resolution used (1 mm in plane, 2 mm slice thickness). Of note regarding these differences, the printed model was slightly larger than the design model in CT (+0.1 mm on average, Figure 3), while in MR images it was smaller (−.61 mm on average, Figure 3) than the designed model. We hypothesize this is likely due to the relatively low GRE signal given the short T2* of the printed material, particularly at the edges of the model where susceptibility gradients at the air/polymer interface would be strongest, leading to diminished signal in the model periphery.

As 3D printing becomes increasingly incorporated into clinical practice for pre-surgical simulation and physician training (1), it is likely that manufacturers or researchers will aim to produce materials that can be imaged with MRI and that potentially have pre-specified MR characteristics. Experimentation is fairly straightforward for stereolithography, which produces a 3D print by selectively exposing the top or bottom surface of a vat containing the liquid resin. One can readily dope this resin toward achieving a polymer that has an MR signal, and potentially with specified relaxation times. The characterization of the signal-bearing protons and MR properties of the material in this work are a step in that direction. For example, it would be of interest to test whether addition of petroleum naphtha to other photo-curable resins can be made to similarly possess an MR signal. This would be valuable for a number of MR applications including generation of phantoms for pulse sequence development.

Unlike stereolithography, material jetting jets the liquid resin at the desired locations much like an ink-jet printer. Equipment in this category can mix different resins during the jetting process to achieve a range of colors and mechanical properties such as durometers. Our choice of this latter 3D printing technology for this first foray into MR-visible 3D printing was driven by the potential to use this option to print human anatomical models that have different HU and MR signal properties at different prescribed anatomic locations in order to emulate in the fabricated phantoms the diverse human tissue signal contrasts. For example, bone and tumor would ideally be differentiated both visually using different colors in a printed model, as well as by different signal in the MR images. The production of such models can be readily tested based on our results. For example, the cancerous bone could be printed using a small percentage of any of the materials for this printer that had no MR signal and the RGD-525 material for the remaining percentage, while healthy bone could be printed exclusively using the RGD-525 material. This should result in a phantom that possesses reduced MR signal for the tumor. This ability we believe will be invaluable for the creation of 3D-printed models that can be used to accurately simulate and practice MRI-guided intervention for pre-surgical planning.

Conclusion

Current material jetting 3D printing technologies can be used to print anatomically accurate phantoms that can be imaged using both CT and MRI. Anticipated uses of these models include the pre-operative simulation of minimally invasive MRI-guided therapies such as cryotherapies for bone tumors toward safe, precision interventions, as well as physician training for increasingly complex procedures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging (D.M.), grant number: K01 EB015868; Grant sponsor: Vital Images, a Toshiba Medical Systems Company (D.M.); Grant sponsor: Toshiba America Medical Systems (D.M.) Grant sponsor: National Institute of Biomedical Imaging (S.E.M.), grant numbers: R01 EB006867 and R01 EB010195; Grant sponsor: National Cancer Institute (S.E.M.), grant number: R01 CA160902; Grant sponsors: National Center for Research Resources, National Cancer Institute, and National Institute of Biomedical Imaging, grant number: R01 U41 RR019703.

References

- 1.Mitsouras D, Liacouras P, Imanzadeh A, Giannopoulos AA, Cai T, Kumamaru KK, George E, Wake N, Caterson EJ, Pomahac B, Ho VB, Grant GT, Rybicki FJ. Medical 3D Printing for the Radiologist. Radiographics. 2015;35(7):1965–1988. doi: 10.1148/rg.2015140320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'urso P, Atkinson R, Bruce I, Effeney D, Lanigan M, Earwaker W, Holmes A, Barker T, Thompson R. Stereolithographic (SL) biomodelling in craniofacial surgery. Br J Plast Surg. 1998;51(7):522–530. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1998.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGurk M, Amis AA, Potamianos P, Goodger NM. Rapid prototyping techniques for anatomical modelling in medicine. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1997;79(3):169–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markl M, Schumacher R, Kuffer J, Bley TA, Hennig J. Rapid vessel prototyping: vascular modeling using 3t magnetic resonance angiography and rapid prototyping technology. MAGMA. 2005;18(6):288–292. doi: 10.1007/s10334-005-0019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrmann KH, Gartner C, Gullmar D, Kramer M, Reichenbach JR. 3D printing of MRI compatible components: why every MRI research group should have a low-budget 3D printer. Medical engineering & physics. 2014;36(10):1373–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menikou G, Dadakova T, Pavlina M, Bock M, Damianou C. MRI compatible head phantom for ultrasound surgery. Ultrasonics. 2015;57:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Himes NC, Chansakul T, Lee TC. MR Imaging–Guided Spine Interventions. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2015.05.007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stratasys. OBJET RGD525 Safety Data Sheet. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitsouras D, Mulkern RV, Rybicki FJ. Strategies for inner volume 3D fast spin echo magnetic resonance imaging using nonselective refocusing radio frequency pulses. Medical physics. 2006;33(1):173–186. doi: 10.1118/1.2148331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitsouras D, Owens CD, Conte MS, Ersoy H, Creager MA, Rybicki FJ, Mulkern RV. In vivo differentiation of two vessel wall layers in lower extremity peripheral vein bypass grafts: application of high-resolution inner-volume black blood 3D FSE. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62(3):607–615. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gudbjartsson H, Maier SE, Mulkern RV, Morocz IA, Patz S, Jolesz FA. Line scan diffusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36(4):509–519. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maier SE, Gudbjartsson H, Patz S, Hsu L, Lovblad KO, Edelman RR, Warach S, Jolesz FA. Line scan diffusion imaging: characterization in healthy subjects and stroke patients. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 1998;171(1):85–93. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.1.9648769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whittall KP, MacKay A. Quantitative interpretation of NMR relaxation data. J Magn Reson. 1989;84:134–152. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark PR, Chua-anusorn W, St Pierre TG. Bi-exponential proton transverse relaxation rate (R2) image analysis using RF field intensity-weighted spin density projection: potential for R2 measurement of iron-loaded liver. Magnetic resonance imaging. 2003;21(5):519–530. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(03)00080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tofts PS, Lloyd D, Clark CA, Barker GJ, Parker GJ, McConville P, Baldock C, Pope JM. Test liquids for quantitative MRI measurements of self-diffusion coefficient in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2000;43(3):368–374. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200003)43:3<368::aid-mrm8>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maier SE, Mitsouras D, Mulkern RV. Avian egg latebra as brain tissue water diffusion model. Magn Reson Med. 2013 doi: 10.1002/mrm.24941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kriz J, Masar B, Plestil J, Pospisil HDD. Three-layer micelles of an ABC block copolymer: NMR, SANS, and LS study of a poly (2-ethylhexyl acrylate)-block-poly(methyl methacrylate)-block-poly(acrylic acid) copolymer in D2O. Macromolecules. 1998;31:41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khandelwal D, Hooda S, Brar AS, Shankar R. Stereochemical assignments of the nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of isobornyl acrylate/methacrylonitrile copolymers. J Appl Polymer Sci. 2012;126:916–928. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khandelwal D, Hooda S, Brar AS, Shankar R. 1D and 2D NMR studies of isobornyl acrylate – methyl methacrylate copolymers. J Mol Structure. 2011;1004:121–130. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pardini OR, Amalvy JI. FTIR, 1H-NMR spectra, and thermal characterization of water-based polyurethane/acrylic hybrids. J Appl Polymer Sci. 2008;(107):1207–1214. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russ M, O'Hara R, Nagesh SVS, Mokin M, Jimenez C, Siddiqui ABD, Rusin S, Ionita CN. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng 9417, Medical Imaging 2015: Biomedical Applications in Molecular, Structural, and Functional Imaging. Orlando, FL: 2015. Treatment planning for image-guided neuro-vascular interventions using patient-specific 3D printed phantoms; p. 941726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mokin M, Setlur Nagesh SV, Ionita CN, Levy EI, Siddiqui AH. Comparison of modern stroke thrombectomy approaches using an in vitro cerebrovascular occlusion model. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2015;36(3):547–551. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medvid R, Ruiz A, Komotar RJ, Jagid JR, Ivan ME, Quencer RM, Desai MB. Current Applications of MRI-Guided Laser Interstitial Thermal Therapy in the Treatment of Brain Neoplasms and Epilepsy: A Radiologic and Neurosurgical Overview. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2015 doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bomers JG, Sedelaar JP, Barentsz JO, Futterer JJ. MRI-guided interventions for the treatment of prostate cancer. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2012;199(4):714–720. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrison RJ, Hollister SJ, Niedner MF, Mahani MG, Park AH, Mehta DK, Ohye RG, Green GE. Mitigation of tracheobronchomalacia with 3D-printed personalized medical devices in pediatric patients. Science translational medicine. 2015;7(285):285ra264. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.