Abstract

Objective

A major impediment to translating chemoprevention to clinical practice has been lack of intermediate biomarkers. We previously reported that rectal interrogation with low-coherence enhanced backscattering spectroscopy (LEBS) detected microarchitectural manifestations of field carcinogenesis. We now wanted to ascertain if reversion of two LEBS markers spectral slope (SPEC) and fractal dimension (FRAC) could serve as a marker for chemopreventive efficacy.

Design

We conducted a multicentre, prospective, randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled, clinical trial in subjects with a history of colonic neoplasia who manifested altered SPEC/FRAC in histologically normal colonic mucosa. Subjects (n=79) were randomised to 325 mg aspirin or placebo. The primary endpoint changed in FRAC and SPEC spectral markers after 3 months. Mucosal levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A6 genotypes were planned secondary endpoints.

Results

At 3 months, the aspirin group manifested alterations in SPEC (48.9%, p=0.055) and FRAC (55.4%, p=0.200) with the direction towards non-neoplastic status. As a measure of aspirin's pharmacological efficacy, we assessed changes in rectal PGE2 levels and noted that it correlated with SPEC and FRAC alterations (R=−0.55, p=0.01 and R=0.57, p=0.009, respectively) whereas there was no significant correlation in placebo specimens. While UGT1A6 subgroup analysis did not achieve statistical significance, the changes in SPEC and FRAC to a less neoplastic direction occurred only in the variant consonant with epidemiological evidence of chemoprevention.

Conclusions

We provide the first proof of concept, albeit somewhat underpowered, that spectral markers reversion mirrors antineoplastic efficacy providing a potential modality for titration of agent type/dose to optimise chemopreventive strategies in clinical practice.

Trial Number

Introduction

Despite significant medical advances, colorectal malignancies still ranks as the second leading cause of cancer death among Americans.1 Screening with colonoscopy or faecal tests has modestly impacted upon death rate but many hurdles remain, including test accuracy and patient compliance.2,3 This highlights the need for exploring alternate strategies to mitigate colorectal cancer (CRC) mortality such as chemoprevention.

Of the numerous chemopreventive agents with documented activity in pre-clinical or epidemiological studies, the best established are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), including aspirin.4 Indeed, large-scale randomised clinical trials indicate that aspirin approximately halves the colonic neoplasia risk.5 However, while aspirin has a relatively low toxicity rate (gastrointestinal (GI) ulcers, haemorrhage, perforation), when applied to a large population, the absolute number of complications can be significant. This is juxtaposed by the observation that only a minority of individuals (∼30–50%) will manifest a chemopreventive effect. Thus, the majority of patients are exposed to toxicity without any counterbalancing antineoplastic benefit. These considerations led the US Preventive Services Task Force to conclude that for primary chemoprevention, the harms outweigh the benefits.6

In order to improve this risk–benefit relationship, most approaches until now have focused on designing agents that retain antineoplastic activity while decreasing toxicity. However, clinical studies until now have been disappointing. For instance, cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-2-selective NSAIDS (celecoxib, rofecoxib) did have good antineoplastic efficacy with less GI toxicity but unfortunately were associated with increased cardiovascular events.7 A more practical solution would be to target the subset of patients likely to benefit from aspirin. Most studies have focused on pharmacogenomics, especially polymorphisms of the aspirin metabolising gene uridine diphosphate (UDP)-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)1A6.8 However, there are a copious other potential modulators of aspirin effect (polymorphisms in COX-2,9 ornithine decarboxylase (ODC),10 other inflammatory genes11), which may decrease the predictive ability of a single gene. In addition, CRC is a genetically heterogeneous disease and tumour characteristics may also determine aspirin sensitivity (COX-2 overexpression,12 phosphosoinositol 3 kinase13 or B-Raf mutations14). Finally, emerging evidence suggests the role of non-genomic factors (body mass index (BMI), gender, etc) in aspirin responsiveness.15,16 Thus, it appears unlikely that a simple blood test will be able to accurately predict aspirin chemopreventive efficacy.

Analysing the colonic mucosa represents an attractive modality for ascertaining chemopreventive effects. This is underpinned by the well-established concept of field carcinogenesis, which posits that the genetic/exogenous factors are diffuse providing a permissive mutational environment.17–19 Focal neoplastic lesions are a result from stochastic events (eg, truncation of the adenomatous polyposis coli tumour suppressor gene) in this fertile mutational field. The corollary is that biomarkers of field carcinogenesis should identify patients with a higher propensity for developing colonic tumours. The clinical implications of this concept include the need for colonoscopy in patients with adenoma detected on flexible sigmoidoscopy (increased risk of synchronous lesions) or previous colonoscopy (metachronous lesions).20 There have been numerous markers of field carcinogenesis in the predysplastic mucosa, including proteomic,21 genomic,22 methylation23 and microRNA.24 The most common markers for chemoprevention studies have been the reversal of the diffuse increase in proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis. However, the robustness of these markers has been questioned.

Our group has focused on field carcinogenesis assessment for risk stratification using low-coherence enhanced backscattering spectroscopy (LEBS).25 These optical biomarkers quantify the submicron architectural aberration that is well below the resolution of conventional light microscopy (hence, mucosa appears histologically normal). Previous reports demonstrate that rectal LEBS markers predict advanced adenomas (size ≥10 mm or high-grade dysplasia or ≥25% villous features) elsewhere in the colon with excellent accuracy (sensitivity 88–100%, specificity 72–80%).26,27 We therefore wanted to assess whether the reversal of the neoplastic LEBS signatures in the rectal mucosa could provide insights into chemoprevention.

We hypothesised that spectral markers would be responsive to aspirin in subjects at high risk for CRC. We implemented a phase IIb double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial of aspirin in subjects at risk for colonic neoplasia whose primary endpoint was reversion of a carcinogenic-associated spectral marker signature towards non-neoplastic values (increase in spectral slope (SPEC) and decrease in fractal dimension).

Methods

Study design

The study adhered to Good Clinical Practice as per the International Conference on Harmonisation and Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles.28 All subjects gave written informed consent. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) Division of Cancer Prevention performed scientific and statistical reviews of the protocol, sponsored and monitored the trial, provided aspirin and matched placebo and housed the data through Westat. All study data underwent quality check by two Northwestern University-based individuals and then by Westat. The data were then locked, unblinded and released to the study biostatistician, who analysed all data.

Subjects aged ≤70 years undergoing surveillance colonoscopy for adenoma or CRC resected within 6 years were eligible. Subjects on anticoagulants, NSAIDs or chemotherapy, with bone marrow, liver or renal dysfunction, coagulopathy and malignancy (within a year), with incomplete colonoscopy or inadequate bowel preparation, were excluded.

Baseline colonoscopy used a 4 L polyethylene glycol purge (eg, Golytely or NuLytely) and incorporated six biopsies of endoscopically normal rectum and two biopsies of mid-sigmoid. Spectral marker readings were from three rectal specimens and one mid-sigmoid specimen. An entry into the treatment phase required each LEBS parameter, SPEC and fractal dimension (FRAC), to be >1 SD from the value in normal subjects and towards the direction associated with carcinogenesis, as previously defined in cohorts of individuals without and with colonic neoplasia, respectively.26 Subjects were randomised 1:1 to placebo or 325 mg aspirin daily. Three-month biopsy was via flexible sigmoidoscopy, using an 8 oz magnesium citrate purgative. Sample size calculations were performed with assumptions regarding effect size from pilot azoxymethane-treated rat data.

All authors had access to the study data and had reviewed the manuscript.

Spectral marker determination

All endpoints were analysed in a blinded fashion. Analysis of spectral markers was performed as described, within 2 h of specimen acquisition (instrument described in supplementary figure 1).29,30 Briefly, we measured SPEC (units of micron−1), which characterises the size distribution of macromolecular complexes and other intracellular structures, with a decrease in value implying a shift in the size distribution of intracellular structures towards smaller sizes, and FRAC (a unitless parameter), which characterises the spatial autocorrelation function of mass density distribution in tissue.26,29–31 Both parameters provide measures of the fundamental characteristics of the tissue nanoscale architecture; both were multiplied by 103 in graphical presentations.

UUGT1A6 genotyping

Blood mononuclear cell isolation used BD Vacutainer CPT Mononuclear Cell Preparation Tubes, DNA extraction used TRIzol (Life Technologies), purification used Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega) and DNA amplification used Illustra Genomiphi V2 DNA Amplification Kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) as per the manufacturer's instructions. PCR used forward 5′-GGAAAATACCTAGGAGCCCTGTGA-3′ and reverse 5′-AGGAGCCAAATGAGTGAGGGAG-3′ primers, and products were digested with NsiI for T181A (giving fragments of 992 bp (for wild type), 992+616+376 bp (heterozygous) and 616+376 bp (homozygous)) or Fnu4HI for R184S (833+159 bp (wild type), 833+464+369+159 bp (heterozygous) and 464+369+159 bp (homozygous)).

Prostaglandin E2 determination

Tissue in indomethacin-containing buffer was sonicated, supernatant was passed over a prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) affinity column (Cayman Chemical Co) and an eluent was used in enzyme immunoassay (Cayman Chemical Co) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Means, SDs and ranges were computed for continuous demographic variables and for biomarkers at baseline and at 3 months. The difference for each subject between baseline and 3 months in the main outcomes, SPEC and FRAC, and biomarkers was computed for all subjects by treatment group (aspirin, placebo). The per cent change from baseline of SPEC and FRAC was also computed. The significance of the shift in distributions of mean differences between treatment groups (aspirin, placebo) was assessed via two-sample Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney non-parametric test. Alternative hypotheses for the two main outcomes, SPEC and FRAC, were one sided by prospective design, as stipulated in the protocol; all other alternative hypotheses were one sided. Frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical demographic variables and differences between treatment groups for these variables were evaluated via Fisher's exact test. For regression plots, non-parametric Spearman correlation coefficient, and the corresponding non-parametric test, provided the corresponding two-sided p value. Regression line slopes were computed using non-parametric correlation. Cohen's d was used to estimate the effect size in two main outcomes for some subgroups, as indicated. All p values are unadjusted based on all available data. Statistical analyses and graphics used SAS V.9.3 and R 2.15 software packages.

Results

Study population

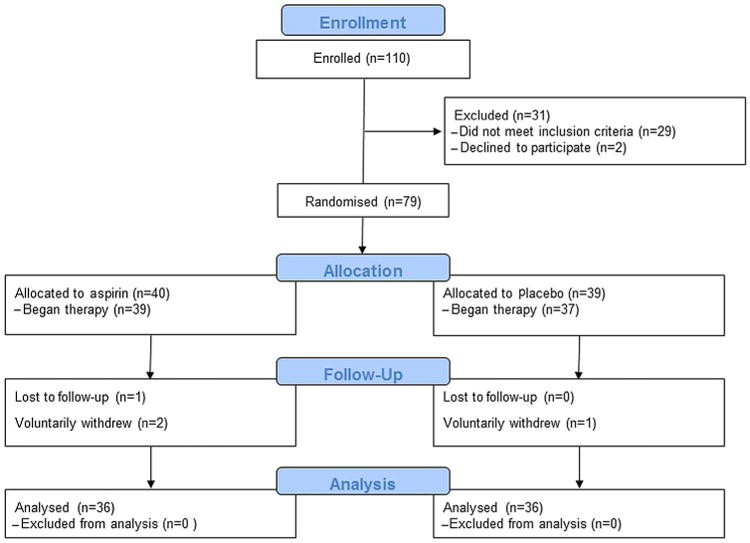

Of 110 subjects analysed, 81 (74%) had a neoplasia-associated spectral signature, as defined by the presence of both abnormal SPEC and FRAC parameters (figure 1). Seventy-nine of 81 (98%) were randomised, and 72 of 79 (89%) completed the primary endpoint (3-month tissue biopsy); 36 from each group. All 72 subjects took ≥80% of their doses, as determined by clinical assessments and by pill count. There were no significant differences in clinical characteristics between treatment groups (table 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of all enrolled subjects.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of accrued subjects.

| Placebo | Aspirin* | |

|---|---|---|

| Age(mean±SD) | 54±11 | 57±9 |

| Gender (% female) | 43 | 38 |

| Adenoma size ≥5 mm (%) | 15 | 13 |

| BMI (mean±SD) | 27±5 | 27±5 |

Differences between placebo and aspirin were not significant at the p<0.05 level. BMI, body mass index.

Eleven and 23 subjects in aspirin and placebo groups, respectively, experienced 18 and 36 adverse events (AEs); all were grade 1 or 2. Abdominal symptoms (mostly discomfort) in four and four subjects and low haemoglobin or bleeding in one subject and two subjects were experienced by those on aspirin and placebo, respectively. One aspirin subject elected to drop out after experiencing grade 1 nausea and abdominal discomfort. Interestingly, all other AEs, the majority of which related to pain and/or inflammatory processes, were experienced by 8 and 20 subjects in aspirin and placebo groups, respectively.

Spectral markers

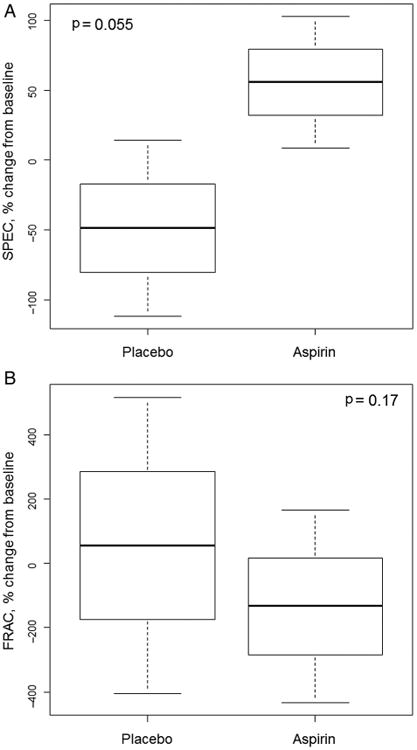

The two prespecified primary endpoints were the changes in values of SPEC and FRAC at month 3 compared with baseline. For SPEC, the mean per cent changes at 3 months for aspirin and placebo groups were 55.8% and −48.9%, respectively (p=0.055 for difference between groups) (figure 2A). The baseline SPEC value for both groups constituted a neoplasia-associated, or high-risk, signature. Importantly, the change in the aspirin group constituted reversion of that signature towards normal, that is, that seen in non-cancer-bearing subjects. For FRAC, the mean per cent changes for aspirin and placebo groups were −134.5% and 55.4%, respectively (p=0.17) (figure 2B). Here too, the baseline FRAC value reverted towards normal values in the aspirin group but not placebo.

Figure 2.

Plots of spectral markers for subjects treated with aspirin or placebo are shown as box plots of per cent changes in spectral slope (SPEC) (A) and fractal dimension (FRAC) (B) values at 3 months post-treatment with aspirin or placebo compared with baseline values, depicting mean (middle line), SD (box) and 95% confidence limits (whiskers). During field carcinogenesis, SPEC typically decreases and FRAC increases, so the data demonstrate a reversion towards less neoplastic signatures by aspirin.

Correlation of spectral marker alterations with measures of aspirin pharmacological efficacy

Several lines of evidence indicate that only a subset of the population benefits from aspirin therapy.5 Therefore, we first ascertained the therapeutic effectiveness of aspirin in individual subjects by determining whether it decreased rectal mucosal levels of PGE2, that is, a direct measurement of its pharmacological action upon the target organ. Then, we correlated changes in PGE2 with changes in SPEC or FRAC. Aspirin inhibits COX enzyme activity, thereby decreasing downstream synthesis of PGE2. Increased PGE2 levels have been implicated in colon carcinogenesis, while decreases directly reflect NSAID pharmacological action and chemoprevention efficacy.32

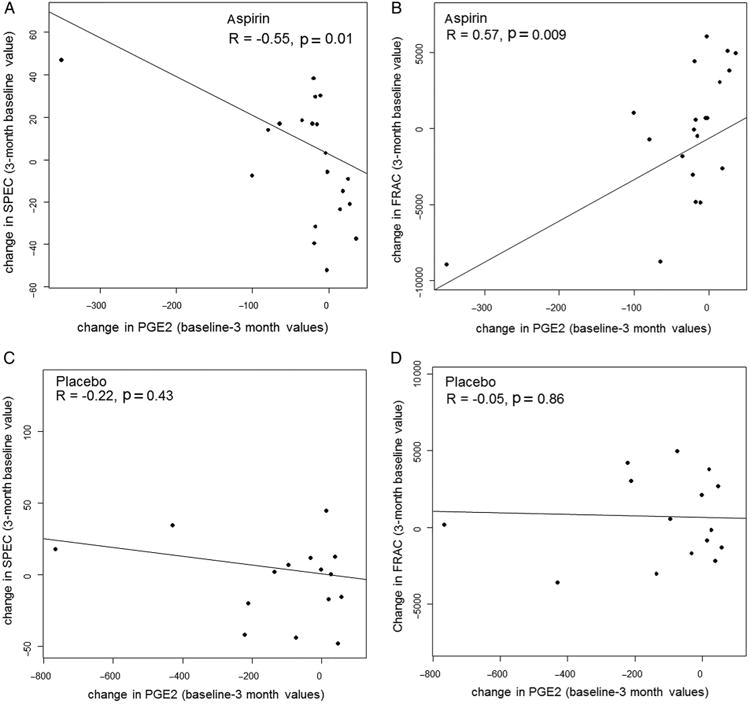

With aspirin subjects, the suppression of PGE2 significantly correlated with SPEC (R=−0.55, p=0.01; two-sided test for Spearman non-parametric correlation) and FRAC improvement (R=0.57, p=0.009) (figure 3A, B). In contrast, with placebo subjects there was no significant correlation with SPEC (R= −0.22, p=0.43) or FRAC (R=−0.05, p=0.86) (figure 3C, D). These findings demonstrate that in subjects experiencing a pharmacological effect by aspirin in the colon, both SPEC and FRAC spectral marker signatures significantly changed from neoplastic towards normal. They support the notion that ultrastructural changes characteristic of early carcinogenesis, measured by spectral analysis in histologically normal colonic epithelium in subjects at high risk for CRC, can be reverted towards normal by aspirin therapy.

Figure 3.

Plots of changes in spectral markers versus changes in prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) expression in tissue are shown as scatter plots of changes in spectral slope (SPEC) (A and C) and fractal dimension (FRAC) (B and D) versus changes in PGE2 for individual patients treated with aspirin (A and B) or placebo (C and D).

Previous reports suggest that aspirin chemopreventive efficacy is confined to subjects with homozygotic UGT1A6 variant polymorphisms, which predispose to slower aspirin metabolism.8 Since the frequency of homozygotic UGT1A6 variant alleles was low, heterozygotes and homozygotes were combined as a variant group (47% of the population) and compared with wild type (53%). In UGT1A6 variants, SPEC tended to increase (ie, normalise) with aspirin, compared with placebo, while FRAC tended to decrease (ie, normalise) with aspirin, figure 4A and B. While differences between aspirin and placebo subjects harbouring UGT1A6 variants were not significant, p=0.85 for SPEC and p=0.50 for FRAC, the effect size for the variant aspirin group versus variant placebo group was robust at 81% for SPEC and −136% for FRAC, with both markers normalising with aspirin. With UGT1A6 wild types, no such trend was observed.

Figure 4.

Plots of spectral markers based on UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)1A6 genotypes are shown as box plots of changes in spectral slope (SPEC) (A) and fractal dimension (FRAC) (B) in UGT1A6 variant subjects and wild-type subjects treated with aspirin or placebo. Plots depict the mean (middle line), SD (box) and 95% confidence limits (whiskers); p values are differences between cohorts demarcated by brackets.

Discussion

For clinically detectable cancer, a universal measure of therapeutic efficacy is available through the measurement of tumour size, typically through radiographic imaging. This relatively robust marker has served to allow the assessment of therapeutic efficacy. As such, it has made possible rapid advances in therapeutics observed in this field. In comparison with advanced cancer, the field of chemoprevention offers the advantage of therapeutic intervention in the context of a less complex backdrop of molecular aberrations. As increased molecular aberrations provide direct pathways to bypass or overcome therapeutic efficacy, a high therapeutic index is theoretically achievable through a chemopreventive approach. However, the field of chemoprevention has been severely hampered by a robust and rapid predictor of therapeutic efficacy. This report describes the first such measure. Although the SPEC biomarker fell 0.1% short of the p value of 0.05, the latter is arbitrarily set and our study was likely underpowered (the sample size calculations were partially determined based on animal model data which fail to recapitulate the heterogeneity of clinical trials). Moreover, while the definitive ‘gold standard’ for chemoprevention is lacking, the correlation with PGE2 levels and UGT1A6 genotype provides strong support for the notion that spectral markers may foreshadow long-term antineoplastic efficacy. In consideration of these factors, this technology may offer the ability to open up new vistas for advances in cancer chemoprevention strategies.

The approach for detecting alterations of field effect is particularly attractive since it encompasses the complexity engendered by the interplay of genetic/exogenous factors for colon carcinogenesis risk (the exposome concept).33 Furthermore, using biomarkers of field carcinogenesis allows more rapid and much less expensive studies than the typical studies which generally rely on colonoscopic-detected adenoma recurrence. Previously employed intermediate biomarkers of field effect include rectal aberrant crypt foci but the handful of chemoprevention studies until now have yielded discordant results.34 In the similar vein, proliferation and apoptosis, usually in the uninvolved rectal mucosa, are correlated with the presence of neoplasia elsewhere in the colon, although the reliability as a chemopreventive biomarker has been suboptimal.35–37

Our group has focused on microarchitectural manifestations of the genetic/epigenetic alterations in field carcinogenesis. The epithelium appears normal by light microscopy, but this is only informative about structures, but >∼200 nm (the diffraction limit of light).38 Thus, structures implicated in early carcinogenesis (eg, mitochondria, ribosomes, higher order chromatin, etc) can be profoundly altered without any histological evidence. LEBS-based markers are not only sensitive to structures >40 nm but highly quantitative, thus overcoming another major hurdle of imaging–biomarker translation.18 We have previously demonstrated that rectal spectral markers accurately assessed the risk of concurrent and future neoplasia (advanced adenomas and carcinomas).25–27 With regard to chemoprevention, our preclinical data have shown that spectral parameters are normalised by chemopreventive agents.30,31 These markers encompass the gamut of submicron architecture. For instance, FRAC represents the space-filling nature of the tissue and is well established in cancer biology.29,31 SPEC measures the complexity in size distribution of macromolecular complexes and other intracellular structures with the decrease of the SPEC, implying a shift in the size distribution of intracellular structures towards smaller sizes.28 The precise molecular determinants for FRAC and SPEC remain to be elucidated, but initial work implicates cytoskeleton (known to interact with many critical early colon carcinogenesis proteins, including adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), β-catenin and C-src) and high-order chromatin changes (which may reflect transcriptional status of the cell).39,40 While studies are ongoing, the lack of in-depth biological understanding does not impact upon the clinical utility of the biomarker.

Our demonstration that aspirin alterations in spectral markers occurred only in a subset of patients mirrors the epidemiological studies that only 30–50% of the population manifest an antineoplastic benefit from aspirin, thus underscoring the clinical imperative for developing robust intermediate biomarkers.5,32 While we demonstrate that in toto spectral markers tended to normalise with aspirin, the crux of the issue is whether it identified patient actually manifesting a chemopreventive benefit. In this short-term study, it is difficult to unequivocally determine. Predicting future chemopreventive responsiveness is difficult with numerous putative pharmacogenomics, exogenous (diet, BMI, etc) and inflammatory modulators.41–43 Molecular targets of NSAIDS would be logical but again there are a plethora of potential candidates (COX-2, peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor δ, β-catenin, NSAID-activating protein, cyclic guanine monophosphate (cGMP)-dependent protein, 15-PDGH, etc).44,45 Thus, instead of targeting one of the plethora of molecular targets, more generalisable intermediate biomarkers are needed. For this study with aspirin, we prospectively assessed rectal PGE2 levels and the pharmacogenomic parameter, UGT1A6 and noted that only when these parameters were suggestive of a chemopreventive milieu did the spectral markers revert to non-neoplastic values.

We initially focused on rectal PGE2 levels given its pleotropic proneoplastic effects on bioactive lipids. There are several lines of evidence to support the role of PGE2 in colon carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. PGE2 impacts upon numerous pathways, including cell growth, Wnt signalling, methylation and invasiveness.46 Urinary PGE2 derivatives have been shown to be a potentially robust screening test for CRC.47 With regard to chemoprevention, PGE2 is an important intermediate for both COX-2 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) delta, a well-established antineoplastic therapeutic target of NSAID. Indeed, the level of COX-2 appears to have a major influence on chemopreventive sensitivity. In familial adenomatous coli (FAP) patients, colonic mucosal PGE2 levels have been proposed as a robust biomarker for chemoprevention.48 On the other hand, there is evidence that there are non-prostaglandin-mediated pathways with NSAID derivatives lacking anti-COX activity (eg, sulindac sulfone) showing some chemopreventive activity. Furthermore, rectal PGE2 suppression plateaus at 81 mg of aspirin per day, while epidemiological studies indicate that adenoma/CRC suppression has a more linear dose–response curve.49,50 Viewed in toto, the weight of the evidence would suggest that PGE 2 is a reasonable albeit imperfect marker of the chemopreventive efficacy of aspirin. Our study demonstrates that PGE2 reduction with aspirin correlated with less neoplastic changes in both FRAC and SPEC. On the other hand, patients who did not manifest a benefit by spectral markers had no significant reduction in PGE2 levels. The respective controls prevent confounding from the slight (nonsignificant) reduction in rectal PGE2 levels in the placebo group.

From a pharmacogenomic perspective, we assessed UGT1A6 that inactivates aspirin via glucuronidation. Variant alleles lead to slower degradation of aspirin. Data from the Nurse Health Study demonstrated that aspirin was associated with decreased adenoma occurrence in only subjects with the variant UGT1A6.8 Our data demonstrated that aspirin had a much more dramatic effect on normalising SPEC and FRAC (albeit only the former approached statistical significance with a p value of 0.06 because of the larger variation in FRAC) in UGT1A6 variant rather when compared with wild type. The correlation, while suggestive, is imperfectly consistent with other potential aspirin-modulatory polymorphisms (ODC, COX-2, etc) along with exogenous factors such as BMI that were not explored in this study. Further supporting the relevance in our study is that PGE2 levels only decreased in patients with variant UGT1A6 but not wild type.

There are many strengths of this study. First is the novelty with this being the proof of concept for spectral markers and affirms initial reports in animal models. Conceptually, the advantage of evaluating the colonic mucosa as a means of assessing the complex gene–environmental interplay is very attractive and is bolstered by large amounts of clinical data in risk stratification (screening). Furthermore, since these microarchitectural alterations may represent a common pathway for heterogeneous genetic/epigenetic changes, this may be particularly accurate. Another strength is the rigorous study design. This includes prospective nature and double blinded. The endpoints were predetermined and bolstered by large-scale clinical trials on screening on both ex vivo and more recent preliminary in vivo data. Execution as assessed by compliance and dropout rate was excellent. Importantly, while the current study focused on aspirin and colon cancer, this technology has broad applicability across organ sites and therapeutic agents. It has already been demonstrated that this technology will identify individuals at high risk for lung and pancreatic cancers.51,52 This broad applicability relates to the ability of this technology to accurately measure fundamental changes in chromatin structure, and in particular, those changes associated with cancer progression. The applicability of this technology across therapeutic agents relates to the fact that aspirin's chemopreventive efficacy does not stem from its ability to directly affect DNA or chromatin structure, which it does not. But rather, aspirin's multiple other primary effects, including COX inhibition, result in reversion of carcinogenesis and is reflected by associated potential normalisation of high-order chromatin structure.

On the other hand, there are several limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, while the trends were strong for the primary endpoints, they did not meet classic criteria for statistical significance. It bears reiteration that statistical significance threshold of p<0.05 is arbitrary and SPEC of 0.055 for a short-term intervention appears quite promising. Furthermore, these findings need to be viewed in the context that only approximately half the patients would not be anticipated to manifest a chemopreventive benefit. In this regard, the sample size estimate was based on preclinical data which do not have the same interindividual variability or ‘patchiness’ of field carcinogenesis.53 Finally, since this was a short-term study, we did not have the ability to assess for unequivocal markers of aspirin efficacy (adenoma recurrence, etc). We were able to address these concerns by correlating our spectral markers with established secondary endpoints (rectal PGE2 and UGT1A6 status), which, while imperfect (thus, the need for novel biomarkers), were generally supportive.

In conclusion, we provide the proof of principle that spectral markers, which we have previously shown to be excellent markers of risk stratification, may also serve as a companion biomarker for chemoprevention. This study indicates that shortterm aspirin tended to normalise the spectral marker somewhat mirroring the suppression of PGE2 and permissive UGT1A6 status, probably the best (although clearly suboptimal) conventional predictors of chemoprevention. From a biological perspective, we demonstrate, for the first time, that aspirin reverses the profound microarchitectural aberrations in the predysplastic mucosa, which is a hallmark of field carcinogenesis. While there are a number of caveats in the data, including borderline statistical significance, viewed in toto these data appear very promising and provide the impetus to perform larger scale clinical trials (employing the newly developed fiberoptic LEBS probe).27 The potential clinical applications of the spectral marker-field carcinogenesis strategy include the following: (1) identifying patients at highest risk who may benefit from chemopreventive strategies, (2) in patients whose chemoprevention is initiated, monitor efficacy in order to titrate dosage/alter agent and (3) provide a platform for rapid clinical trials to provide initial validation of chemopreventive agents that demonstrated promise in animal models. This approach of using spectral markers may potentially be a vehicle to allow the era of personalised medicine to be applied to CRC prevention efforts.

Supplementary Material

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this subject?

Aspirin works as a chemopreventive agent against colon cancer reducing the risk by 30–50%.

Various polymorphisms can correlate with aspirin's chemopreventive efficacy, albeit imperfectly.

Changes in field carcinogenesis occur with chemopreventive agents.

Spectral markers appear to be a promising modality to detect microarchitectural markers of field effect and hence risk stratification.

What are the new findings?

Spectral markers rapidly reverted towards non-neoplastic levels in patients treated with aspirin.

This effect correlated with suppression of the proneoplastic aspirin target, prostaglandin E2.

Normalisation of spectral markers appeared to occur in the context of chemoprevention-permissive pharmacogenomics, although this trend did not reach statistical significance.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

The evaluation of rectal spectral markers may provide a modality for rapidly identifying patients who are benefiting from aspirin and enabling titration or switching agents for those not manifesting an antineoplastic response. This may also provide a modality for accelerating clinical studies of compounds with promise in preclinical settings.

Acknowledgments

Funding This work was supported by funding from the United States National Institutes of Health N01-CN-35157 to RCB and HKR.

Footnotes

Additional material is available. To view please visit the journal online (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309996).

Contributors The study idea was conceived by HKR and VB. The study was designed by HKR, BJ, GD, AU, LR, RCB and VB. Samples were acquired by HKR, MJG, LB, DTR and AB. Samples were processed for spectral markers by VT, AJR and VB, for immunohistochemistry by RW, MDLC and CTW, for prostaglandin measurement by RC and for polymorphism analysis by XH and SS. Data were analysed by HKR, BJ, GD, AU, LR, RCB, KP, ER and VB. All statistical analyses were performed by BJ and IBH The manuscript was initially drafted by HKR and then reviewed by all.

Competing interests HKR, MJG and VB are co-founders and shareholders of American BioOptics LLC and Nanocytomics LLC. These corporations were formed by these authors to advance the technology used within this manuscript.

Patient consent Obtained.

Ethics approval Institutional review boards of all sites.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, et al. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1106–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishihara R, Ogino S, Chan AT. Colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after screening. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2355. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1313116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jänne PA, Mayer RJ. Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1960–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006293422606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothwell PM, Wilson M, Elwin CE, et al. Long-term effect of aspirin on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: 20-year follow-up of five randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1741–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Routine aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the primary prevention of colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:361–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertagnolli MM, Eagle CJ, Zauber AG, et al. Celecoxib for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:873–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan AT, Tranah GJ, Giovannucci EL, et al. Genetic variants in the UGT1A6 enzyme, aspirin use, and the risk of colorectal adenoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:457–60. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barry EL, Sansbury LB, Grau MV, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 polymorphisms, aspirin treatment, and risk for colorectal adenoma recurrence--data from a randomized clinical trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2726–33. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barry EL, Mott LA, Sandler RS, et al. Variants downstream of the ornithine decarboxylase gene influence risk of colorectal adenoma and aspirin chemoprevention. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:2072–82. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sansbury LB, Bergen AW, Wanke KL, et al. Inflammatory cytokine gene polymorphisms, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, and risk of adenoma polyp recurrence in the polyp prevention trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:494–501. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS. Aspirin and the risk of colorectal cancer in relation to the expression of COX-2. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2131–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao X, Lochhead P, Nishihara R, et al. Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation, and colorectal-cancer survival. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1596–606. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishihara R, Lochhead P, Kuchiba A, et al. Aspirin use and risk of colorectal cancer according to BRAF mutation status. JAMA. 2013;309:2563–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim S, Baron JA, Mott LA, et al. Aspirin may be more effective in preventing colorectal adenomas in patients with higher BMI (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:1299–304. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartman TJ, Yu B, Albert PS, et al. Does nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use modify the effect of a low-fat, high-fiber diet on recurrence of colorectal adenomas? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2359–65. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lochhead P, Chan AT, Nishihara R, et al. Etiologic field effect: reappraisal of the field effect concept in cancer predisposition and progression. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:14–29. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Backman V, Roy HK. Light-scattering technologies for field carcinogenesis detection: a modality for endoscopic prescreening. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:35–41. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernstein C, Nfonsam V, Prasad AR, et al. Epigenetic field defects in progression to cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2013;5:43–9. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v5.i3.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis JD, Ng K, Hung KE, et al. Detection of proximal adenomatous polyps with screening sigmoidoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of screening colonoscopy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:413–20. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polley AC, Mulholland F, Pin C, et al. Proteomic analysis reveals field-wide changes in protein expression in the morphologically normal mucosa of patients with colorectal neoplasia. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6553–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen LC, Hao CY, Chiu YS, et al. Alteration of gene expression in normal-appearing colon mucosa of APC(min) mice and human cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3694–700. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paun BC, Kukuruga D, Jin Z, et al. Relation between normal rectal methylation, smoking status, and the presence or absence of colorectal adenomas. Cancer. 2010;116:4495–501. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunte DP, DelaCruz M, Wali RK, et al. Dysregulation of microRNAs in colonic field carcinogenesis: implications for screening. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy HK, Kim YL, Liu Y, et al. Risk stratification of colon carcinogenesis through enhanced backscattering spectroscopy analysis of the uninvolved colonic mucosa. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(3 Pt 1):961–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roy HK, Turzhitsky V, Kim Y, et al. Association between rectal optical signatures and colonic neoplasia: potential applications for screening. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4476–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radosevich A, Mutyal NN, Eshein A, et al. Rectal optical markers for in-vivo risk stratification of premalignant colorectal lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:4347–55. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Good clinical practice research guidelines reviewed, emphasis given to responsibilities of investigators: second article in a series. J Oncol Pract. 2008;4:233–5. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0854601. No authors listed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roy HK, Turzhitsky V, Kim YL, et al. Spectral slope from the endoscopically-normal mucosa predicts concurrent colonic neoplasia: a pilot ex-vivo clinical study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1381–6. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9384-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roy HK, Kunte DP, Koetsier JL, et al. Chemoprevention of colon carcinogenesis by polyethylene glycol: suppression of epithelial proliferation via modulation of SNAIL/ beta-catenin signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2060–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy HK, Iversen P, Hart J, et al. Down-regulation of SNAIL suppresses MIN mouse tumorigenesis: modulation of apoptosis, proliferation, and fractal dimension. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1159–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan AT, Arber N, Burn J, et al. Aspirin in the chemoprevention of colorectal neoplasia: an overview. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:164–78. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wild CP. The exposome: from concept to utility. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:24–32. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinsky PF, Fleshman J, Mutch M, et al. One year recurrence of aberrant crypt foci. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:839–43. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahnen DJ, Byers T. Proliferation happens. JAMA. 1998;280:1095–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.12.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West NJ, Courtney ED, Poullis AP, et al. Apoptosis in the colonic crypt, colorectal adenomata, and manipulation by chemoprevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1680–7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sinicrope FA, Half E, Morris JS, et al. Cell proliferation and apoptotic indices predict adenoma regression in a placebo-controlled trial of celecoxib in familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:920–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Backman V, Roy HK. Advances in biophotonics detection of field carcinogenesis for colon cancer risk stratification. J Cancer. 2013;4:251–61. doi: 10.7150/jca.5838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Damania D, Subramanian H, Tiwari AK, et al. Role of cytoskeleton in controlling the disorder strength of cellular nanoscale architecture. Biophys J. 2010;99:989–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stypula-Cyrus Y, Mutyal NN, Dela Cruz M, et al. End-binding protein 1 (EB1) up-regulation is an early event in colorectal carcinogenesis. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:829–35. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan AT, Ogino S, Giovannucci EL, et al. Inflammatory markers are associated with risk of colorectal cancer and chemopreventive response to anti-inflammatory drugs. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:799–808. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.041. quiz e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan AT, Sima CS, Zauber AG, et al. C-reactive protein and risk of colorectal adenoma according to celecoxib treatment. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:1172–80. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nan H, Hutter CM, Lin Y, et al. Association of aspirin and NSAID use with risk of colorectal cancer according to genetic variants. JAMA. 2015;313:1133–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gala MK, Chan AT. Molecular pathways: aspirin and Wnt signaling-a molecularly targeted approach to cancer prevention and treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1543–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fink SP, Yamauchi M, Nishihara R, et al. Aspirin and the risk of colorectal cancer in relation to the expression of 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (HPGD) Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:233re2. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia D, Wang D, Kim SH, et al. Prostaglandin E2 promotes intestinal tumor growth via DNA methylation. Nat Med. 2012;18:224–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cai Q, Gao YT, Chow WH, et al. Prospective study of urinary prostaglandin E2 metabolite and colorectal cancer risk. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5010–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giardiello FM, Casero RA, Jr, Hamilton SR, et al. Prostanoids, ornithine decarboxylase, and polyamines in primary chemoprevention of familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:425–31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sample D, Wargovich M, Fischer SM, et al. A dose-finding study of aspirin for chemoprevention utilizing rectal mucosal prostaglandin E(2) levels as a biomarker. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:275–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan AT, Giovannucci EL, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Long-term use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2005;294:914–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.8.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Radosevich AJ, Mutyal NN, Rogers JD, et al. Buccal spectral markers for lung cancer risk stratification. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mutyal NN, Radosevich AJ, Bajaj S, et al. In vivo risk analysis of pancreatic cancer through optical characterization of duodenal mucosa. Pancreas. 2015;44:735–41. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Payne CM, Holubec H, Bernstein C, et al. Crypt-restricted loss and decreased protein expression of cytochrome C oxidase subunit I as potential hypothesis-driven biomarkers of colon cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2066–75. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.