Abstract

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is an inducible form of the enzyme that catalyses the synthesis of prostanoids, including prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a major mediator of inflammation and angiogenesis. COX-2 is overexpressed in cancer cells and is associated with progressive tumour growth, as well as resistance of cancer cells to conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy. These therapies are often delivered in multiple doses, which are spaced out to allow the recovery of normal tissues between treatments. However, surviving cancer cells also proliferate during treatment intervals, leading to repopulation of the tumour and limiting the effectiveness of the treatment. Tumour cell repopulation is a major cause of treatment failure. The central dogma is that conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy selects resistant cancer cells that are able to reinitiate tumour growth. However, there is compelling evidence of an active proliferative response, driven by increased COX-2 expression and downstream PGE2 release, which contribute to the repopulation of tumours and poor patient outcome. In this review, we will examine the evidence for a role of COX-2 in cancer stem cell biology and as a mediator of tumour repopulation that can be molecularly targeted to overcome resistance to therapy.

1. Introduction

To date, intensive cancer research has culminated in an increased knowledge of primary tumour formation, the development of sophisticated therapies, and prolonged survival time of cancer patients. However, cancer remains a common and lethal disease worldwide with tumour repopulation and metastasis as major causes of cancer-related deaths. A definitive cure for cancer patients will rely upon further molecular dissection and targeting of these two processes. In this regard, there is growing evidence that cancer is a stem cell disease, where tumours are composed of a mixture of genetically and functionally distinctive cells that contribute to tumour outgrowth, and a small population of cancer stem cells (CSCs) that can drive tumour initiation, therapy resistance, tumour repopulation, and metastasis. The CSC model posits that tumours are organised hierarchically in a similar, albeit distorted, manner as normal tissues. In a normal tissue, stem cells, at the apex of this hierarchy, give rise to transit amplifying cells, which proliferate rapidly and finally enter a postmitotic, differentiated state, in which the cells fulfill the various functions of the specific organ. CSCs share important properties with normal stem cells, including self-renewal and multilineage differentiation potential, and drive tumour progression as they have the exclusive ability to perpetuate indefinitely the growth of the tumour and give rise to a diverse array of differentiated progeny that make-up the bulk of the tumour mass [1–5]. Seminal work by Bonnet and Dick in 1997 first identified CSCs in acute myeloid leukemia [6], and subsequently CSCs have been isolated from a majority of solid malignancies including breast [5, 7–9], brain [10], colon [11], osteosarcoma [12, 13], squamous cell carcinoma [14, 15], and prostate [16, 17]. Most of these studies have defined CSCs functionally by their elevated tumour-initiating ability when inoculated into immune-deficient mice, relative to that of non-CSC cancer cells. Similarly to normal stem cells, CSCs are highly resistant to the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy and are able to reinitiate tumour growth [8, 9, 18]. This is seen clinically where these therapies do shrink the bulk of the tumour, but after a remission period of variable length, most patients do relapse with frequent development of drug resistance and metastatic dissemination.

Tumours are not only clonal outgrowths of deregulated cancer cells but potentiate their own progression and survival by fostering a complex and highly dynamic microenvironment, consisting of the extracellular matrix, endothelial cells, immune cells, and a plethora of cytokines and growth factors [19, 20]. Importantly, inflammatory cells and the cellular mediators of inflammation are prominent constituents of the microenvironment of all tumours [21]. In some cancers, the inflammatory conditions precede the development of malignancy, for example, inflammatory bowel disease is associated with colon cancer. Alternatively, an oncogenic change can drive tumour-promoting inflammation in tumours that are epidemiologically unrelated to overt inflammatory conditions [22, 23]. This “smoldering” inflammation in the microenvironment has many tumour-promoting effects including tissue remodelling, angiogenesis, cancer cell survival, metastasis, and immune evasion [21, 24]. One key inflammatory mediator deregulated in many cancers is cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2). Elevated COX-2 expression, and that of its principle metabolic product prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), has been shown to be inversely associated with patient survival [25–27]. Epidemiological, clinical, and preclinical studies have shown that the inhibition of PGE2 synthesis through the use of either nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or specific COX-2 inhibitors has the potential to reduce the risk of developing certain cancers, including breast, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, osteosarcoma, pancreas, and prostate cancers, and to reduce the mortality caused by these cancers [28–35]. Recently, PGE2 has been linked to the “phoenix rising pathway,” in which tissue damage initiates tissue repair [36]. In the context of common cancer therapies, which employ DNA damaging agents to trigger apoptosis, there is evidence that apoptotic cells release PGE2, a potent growth factor, that can stimulate the proliferation of surviving CSCs, leading to accelerated tumour repopulation and patient relapse [37, 38]. In this review, we will focus on the role of COX-2 in cancer stem cell biology, and as a mediator of tumour repopulation, and ultimately resistance to therapy.

2. COX-2 Plays a Central Role in Cancer

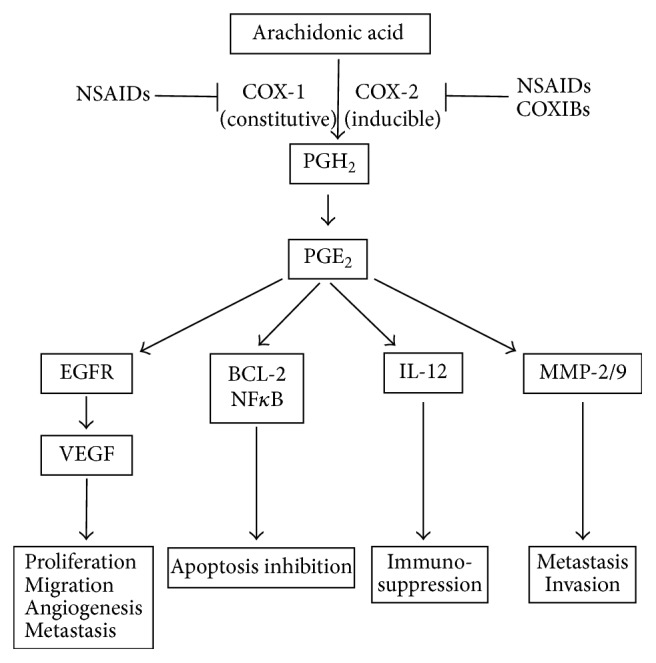

Cyclooxygenases are enzymes necessary for the metabolic conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins, including PGE2, a major mediator of inflammation and angiogenesis (Figure 1). PGE2 signals through four pharmacologically distinct G-protein coupled receptors, EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4, which each activate different downstream signalling pathways. In turn, PGE2 is catabolized to the inactive 15-keto-PGE2 by the enzyme 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase [40, 41]. There are two isoforms of cyclooxygenase: COX-1 and COX-2. Both exist as integral, membrane-bound proteins, located primarily on the luminal side of the endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear envelope [42]. COX-1 is characterised as a housekeeping enzyme required for the maintenance of basal level prostaglandins [43] and is expressed constitutively in most tissues. It is responsible for the maintenance of internal homeostasis by participating in processes such as platelet aggregation, cytoprotection of the gastric mucosa, vascular smooth muscle functioning, and renal function. By contrast, COX-2 usually remains undetected in healthy tissues and organs. In adults, it is found only in the central nervous system, kidneys, vesicles, and placenta, whereas in the fetus, it occurs in the heart, kidneys, lungs, and skin [40, 44]. COX-2 is highly inducible and can be rapidly upregulated in response to various proinflammatory agents, including cytokines, mitogens, and tumour promoters, especially in cells involved in inflammation, pain, fever, Alzheimer's disease, osteoarthritis, or tumour formation [42, 45]. Under normal conditions, acute inflammation is a tightly controlled self-limiting response, where upon abatement of the inflammatory stimulus, specific cytokines, including interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-6, exert feedback inhibition causing COX-2 expression and PGE2 production to cease and the inflammatory response to subside. However, with sustained exposure to proinflammatory stimuli, continued expression of COX-2 leads to the transition from acute to chronic inflammation [42, 46]. In recent decades, COX-2 overexpression has been reported in several human cancers including breast [47–49], lung [47, 50], skin [51], colon [47, 52, 53], bone [32, 54, 55], cervical [56], oesophageal [57], pancreatic [58], prostate [59], and bladder cancer [60]. Constitutive expression of COX-2 and sustained biogenesis of PGE2 appear to play predominant roles in the initiation and promotion of cancer progression. PGE2 can mediate these effects through numerous signalling pathways including activation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) leading to increased cell proliferation, metastatic and invasive potential, and angiogenesis [61]; increased expression of the protooncogenes, BCL-2, and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), through the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway, respectively [62, 63]; increased transcriptional activity of the antiapoptotic mediator nuclear factor κB (NFκB) [64]; enhanced metastasis and invasion by activation of matrix metalloproteases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) [65]; and suppression of the production of IL-12, leading to immunosuppression [66].

Figure 1.

Prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis and downstream cellular effects. Arachidonic acid is released from cellular membranes and converted to PGH2 through the activity of the COX enzymes. COX-1 is constitutively expressed in many cells, generating low levels of prostaglandins that are cytoprotective and maintain homeostasis. In contrast, COX-2 is absent from most cells and is induced by a number of inflammatory stimuli. PGH2 is rapidly converted to PGE2, which plays a predominant role in cancer progression by stimulating tumour cell proliferation, migration, angiogenesis, apoptosis resistance, invasion, and metastasis. NSAIDS and COXIBS can pharmacologically block the activity of the COX enzymes.

Within the context of stem cell biology, PGE2 has been heralded as an evolutionarily conserved regulator of haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) [67]. Stem cells are characterised by their unique abilities to both self-renew and differentiate to produce all mature cell lineages of a given tissue type [2]. In the adult vertebrate, HSCs reside in the bone marrow and are crucial to maintain lifelong production of all blood cells [68]. Utilising zebrafish and mouse models, the COX-2/PGE2 axis has been shown to be required for HSC formation [69], proliferation [70, 71], maintenance of the haematopoietic lineage [72], and bone marrow recovery following irradiation injury [69, 73]. Molecular dissection of the mechanisms by which PGE2 exerts these effects on HSCs has identified in vivo evidence that PGE2 enhances the activation of Wnt, a key regulator of stem cell self-renewal, during embryogenesis by stabilising β-catenin, and that Wnt-mediated regulation of HSC development is PGE2-dependent [67]. Given the stem-cell-enhancing activity of PGE2, and that PGE2 activates general cell survival and proliferation pathways, it is unsurprising that upregulation of COX-2 is associated with populations of CSCs isolated from several cancer types, including breast [74–77], colon [78, 79], and bone cancer [13, 80]. COX-2 is coexpressed with CSC markers including CD44, CD133, Oct3/4, LGR5, SOX-2, and ALDH [75, 78, 81–84]. A functional marker of CSCs is the ability to grow as spheroid colonies in defined serum-free culture conditions that supports the proliferation of undifferentiated cells [85]. Cells that overexpress COX-2 exhibit greater sphere forming efficiency and clonogenicity than those that express low levels of COX-2 [75, 86, 87]. In breast CSCs, isolated from the primary tumours of HER2/Neu transgenic mice, COX-2 expression was upregulated 30-fold in CSCs compared to non-CSCs, and constituted part of an eight-gene signature that correlated with breast cancer patient survival [88]. Furthermore, transfection of COX-2 into the ER-positive breast cancer cell line, MCF7, increased the ability of MCF7 cells to grow as spheres [86]. In our own work, we have shown that COX-2 expression is elevated 141-fold in the CSC population compared to the non-CSC population of canine osteosarcoma cells, and that COX-2 inhibition induced a dose-dependent decrease in sphere forming ability, indicating that COX-2 plays a major role in tumour initiation [13]. Our data is consistent with a previous study in which mouse embryonic stem cells lacking functional COX-2 have a normal growth rate and differentiation potential but are profoundly compromised in their ability to form teratocarcinomas in vivo [89]. Furthermore, CSCs isolated from human glioma cell lines, express constitutively high levels of COX-2 protein that correlates positively with radioresistance. Inhibition of COX-2 enhanced radiosensitivity of glioma CSCs and suppressed the expression of angiogenic and stemness-related genes [90]. Together, this data suggests that inhibiting COX-2 in CSCs reduces stem cell characteristics and that COX-2 plays a vital role in the maintenance and function of the CSC population.

3. Mechanisms of Resistance to Therapy

The death of all cancer cells in a tumour is the ultimate goal of cancer therapy. After surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy remain the most important treatment modalities of advanced carcinomas, and although they effectively shrink the tumour mass, some patients become progressively unresponsive and ultimately drug resistant [91]. Resistance can be divided into two broad groups: intrinsic or acquired. Intrinsic resistance indicates that, prior to receiving the therapy, resistance-mediating factors preexist in a subset of cancer cells that make the therapy ineffective, including increased drug efflux and aberrant DNA damage repair pathways. Acquired resistance can develop during treatment of tumours that were initially sensitive and can be caused by mutations arising during treatment, as well as through other adaptive responses, including activation of alternative compensatory signalling pathways and evasion of cell death [92]. Moreover, tumours contain a high degree of molecular heterogeneity; thus, drug resistance can arise through therapy-induced selection of a resistant population of cells that was present in the original tumour [2]. Recent studies have shown that the extensive heterogeneity observed within tumours occurs through mechanisms independent of CSC differentiation and supports a model whereby the CSC phenotype is dynamic rather than a fixed state. For example, induction of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), by ectopic expression of the transcription factors Twist or Snail, in mammary cancer cells is associated with CSC qualities and an increased propensity to form tumours [93, 94]. Similarly, melanoma cells can reversibly turn on and off the histone demethylase JARID1B, and cells that express JARID1B are more tumourigenic than those that do not [95]. And exposure of glioma cells to perivascular nitric oxide reversibly promotes their ability to form tumours [96]. These findings challenge the unidirectional hierarchical CSC model: signifying that non-CSCs can dedifferentiate and can acquire CSC-like properties under certain conditions.

Common cancer therapies produce toxic substances that destroy crucial cellular macromolecules, including DNA, leading to cell death. An unfortunate side effect is high toxicity to normal tissues: to avoid severe toxic reactions, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are often given in multiple doses, which are spaced out to allow the repopulation of surviving cells in normal tissues during the prolonged overall treatment time. However, surviving cancer cells also proliferate during the intervals between treatments and this process of repopulation is an important cause of treatment failure [97]. Furthermore, a long recognised phenomenon is that of accelerated repopulation, where the few surviving cancer cells that have escaped death after exposure to radiotherapy or chemotherapy can rapidly repopulate the badly damaged tumour by proliferating at a markedly accelerated rate. Subsequent tumour repopulation with resistant cancer cells often results in a more aggressive cancer phenotype with poor prognosis for the patient. There is ambiguity regarding tumour type and repopulation potential: some studies report that accelerated repopulation occurs only in the late stages of radiation treatment, whereas other studies, such as those in cervical cancer [98], squamous cell carcinomas [99], bladder cancer [100], and colorectal carcinomas [101], show that the onset time of accelerated repopulation is relatively short [102, 103]. This has implications for treatment regimes, and the efficacy of therapy. The molecular mechanisms underlying this process of accelerated tumour repopulation are not well understood. A seminal study has shown that CSCs, isolated from bladder urothelial carcinomas, actively proliferate in response to chemotherapy-induced damages and repopulate residual tumours between chemotherapy cycles, in a similar fashion to how normal tissue stem cells mobilise to the site of a wound during tissue repair [37].

Wound healing and tissue regeneration are essential processes for all multicellular organisms. Some organisms have the ability to entirely regenerate amputated limbs, such as salamanders [104], whereas other organisms can only partially replace damaged organs, such as humans [105]. The resident tissue stem cells play a crucial role in wound healing and tissue regeneration. Damaged tissues mobilise and recruit stem cells to the site of damage, where they proliferate, differentiate, and eventually replace the damaged tissue [106]. Several studies in Drosophila [107], Xenopus [108], Planaria [109], and Hydra [110] have indicated a facilitative role for apoptosis as a trigger for tissue remodelling in response to tissue injury, identifying caspase activation as a key requirement for cell proliferation and stem cell recruitment. Although counterintuitive, as apoptosis is generally considered as a means for multicellular organisms to dispose of damaged or unwanted cells, there is increasing evidence that dying cells can signal their presence to the surrounding tissues and, in doing so, elicit tissue repair and regeneration that compensates for any loss of function caused by cell death [111]. The first evidence of this in a mammalian model was provided by Li et al. [36] and coined the phrase “phoenix rising pathway,” in which tissue damage initiates tissue repair. This study revealed that mice deficient in caspase-3 and caspase-7, which are essential apoptotic proteases, exhibited reduced rates of tissue repair in dorsal skin wounds and defects in liver regeneration following partial hepatectomy. Mechanistically, apoptotic cells released PGE2 in a caspase-dependent manner, and this in turn stimulates stem cell proliferation and tissue regeneration [36]. Given that aberrant apoptosis is a hallmark of cancer [4] and that activation of caspases to induce apoptosis is the prevailing ideology of most cancer treatments, what is the role of apoptosis-induced compensatory proliferation in cancer development? Is the phoenix rising pathway clinically relevant?

Cancers often acquire mutations that prevent apoptosis, leading to the survival of precancerous cells (that would otherwise die) and giving rise to neoplasia. This model appears to be oversimplified, and data is emerging, which expands and links the role of apoptosis-induced compensatory proliferation in normal tissue repair and regeneration, to tumourigenesis. Studies of γ-irradiation-induced lymphoma formation in mice deficient in PUMA, a DNA damage induced proapoptotic mediator, showed a reduction in apoptosis and, surprisingly, a concurrent reduction in tumour incidence [112, 113]. Similarly, PUMA-deficient mice treated with diethylnitrosamine, a DNA-alkylating agent and hepatocarcinogen, showed a reduction in apoptosis of hepatocytes and decreased tumour incidence [114]. Although these studies lack mechanistic insight, this data indicates that PUMA-dependent apoptotic cell death may drive compensatory proliferation in lymphogenesis and hepatocarcinogenesis. Further to this, a seminal study by Huang et al. [39] illustrated, in vitro and in vivo, that the phoenix rising pathway is applicable to cancer biology, whereby apoptotic tumour cells can stimulate the repopulation of tumours from a small number of surviving cells, and that this process is caspase-3-dependent and involves upregulation of arachidonic acid and subsequent PGE2 production (Figure 2). In this study, labelled cancer cells were implanted into mice with or without lethally irradiated, apoptotic, mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (MEFs). The presence of apoptotic cells increased cell proliferation and tumour cell growth. However implantation of irradiated, caspase-3-deficient MEFs ablated these results. Exogenous treatment with PGE2 also caused cancer cells to grow at a faster rate than untreated cells. Subsequently, Allen et al. [115] utilised a panel of established human cancer cell lines to show that IR-induced, caspase-3-dependent, PGE2 production is a common response of irradiated tumour cells and that PGE2 production generally correlated with enhanced growth of cells that survive irradiation and of unirradiated cells cocultured with irradiated cells. Therefore, the caspase-3/PGE2 axis is a direct link between cell death and tumour repopulation, highlighting that tumours may exploit a tissue homeostatic mechanism to preserve themselves when damaged by cytotoxic therapy, and given the high radiation doses required to kill high numbers of tumour cells, the rare surviving cells are likely to experience significant DNA damage, and rapid proliferation of such cells may enhance mutagenesis and drive tumour progression toward a more metastatic state.

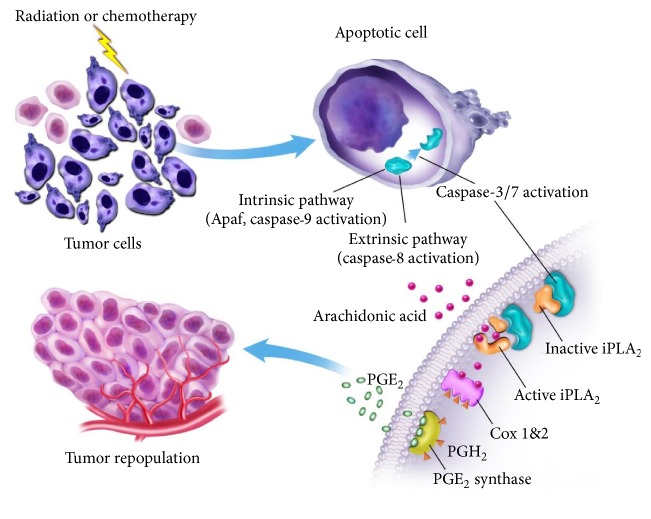

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of apoptosis-mediated tumour cell repopulation. In tumours damaged by cytotoxic therapies apoptotic cells activate caspase-3 and caspase-7 through either intrinsic pathways, involving Apaf and caspase-9 activation, or extrinsic pathways, involving caspase-8 activation. Activated caspase-3 and caspase-7 activate calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2), which increases the synthesis and release of arachidonic acid. Arachidonic acid is then converted into PGH2 by COX-1 and COX-2, which is subsequently converted into PGE2 by the enzyme PGE2 synthase. PGE2 stimulated cancer stem cell proliferation and tumour repopulation (figure was adapted from [39] with the permission of Professor Li).

4. Implications for Cancer Management and Therapy

There is accumulating evidence that the phoenix rising pathway is clinically relevant. In patients with head and neck cancer, high amounts of activated caspase-3 were correlated with high rates of tumour recurrence, and in patients with breast cancer, high caspase-3 levels were correlated with shorter survival time [39]. This has implications for cancer therapy: efforts to develop agents that activate caspases must be reexamined; and small molecule inhibitors of caspases should now be evaluated for their properties to enhance cancer chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Human clinical trials are currently lacking in this area, but several studies using mouse models indicate that blocking apoptosis may increase sensitivity to radiotherapy. For example, in a mouse model of lung cancer, treatment with a caspase-3 inhibitor led to an increase in autophagy and radiosensitivity [116]; and treatment with a pan-caspase inhibitor, zVAD, or small interfering RNA directed against caspase-3 and caspase-7 led to radiosensitivity and delayed tumour growth rates, in breast and lung xenografts [117]. In addition, a recent study has shown that low doses of radiation cause partial caspase-3 activation that leads to genome instability, both in vitro and in vivo, through the generation of persistent DNA strand breaks [118]. These findings implicate caspase-3 as a promising target to improve chemo- and radiation-therapy outcomes. However, inhibition of caspase-dependent apoptosis is counterintuitive, when taking into consideration that the aim of cytotoxic therapies is to induce apoptosis of cancer cells, and further research is required to determine if, in the absence of caspase-activity, cell death comes by an alternative pathway, such as necrotic cell death or senescence.

An alternative strategy is to prevent compensatory proliferation by targeting PGE2 production, which is downstream from caspase-3, by chemical inhibition of COX-1 and COX-2. NSAIDS effectively target cyclooxygenase enzymes and are widely used to treat common inflammatory diseases; for example, naproxen and ibuprofen are widely used and well tolerated. Selective COX-2 inhibitors, such as celecoxib, have been marketed but many have been withdrawn due to increased risk of myocardial infarction; however, the risk has not been assessed for short-term courses during cancer therapy. As we have previously discussed, overexpression of COX-2 and chronic inflammation has been attributed to the development of several cancer types, and there has been extensive preclinical and epidemiological studies that support the targeting of the COX-2 pathway for the prevention and treatment of malignancy (reviewed extensively here [119–121]). Several mouse studies have provided evidence of the synergistic effect of COX-2 inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy and radiotherapy including mouse models of nasopharyngeal carcinoma [122], pancreatic adenocarcinoma [123], and medulloblastoma-derived CSCs [124]. In the context of tumour repopulation, a seminal study by Kurtova et al. [37] used a human bladder cancer xenograft model to show that there is selective repopulation of the tumour from previously slowly proliferating bladder tumour cells that have markers of CSCs. This is the first study to effectively show that CSCs actively contribute to therapeutic resistance via the phoenix rising pathway, whereby chemotherapy effectively induces apoptosis and associated PGE2 release then promotes neighbouring CSC repopulation, akin to how tissue resident stem cells mobilise to wound sites during tissue repair. Additional studies have supported that repopulation can be abrogated by COX-2 inhibition of PGE2-signalling: treatment of a panel of human cancer cell lines with the pan COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitor, indomethacin, blocked radiation-induced PGE2 production, and inhibited cancer cell proliferation [115]; a study of prostate adenocarcinoma mouse xenografts showed that topical application of the NSAID, diclofenac, significantly reduced tumour growth in combination with 3 Gy irradiation [125]; and significantly, celecoxib delivered between rounds of gemcitabine and cisplatin substantially suppressed bladder urothelial carcinoma xenograft regrowth and enhanced the chemotherapeutic response in xenografts from a chemoresistant patient [37]. These results advocate that PGE2-stimulated tumour repopulation is a critical issue to consider during treatment planning and that prospective clinical trials are needed to define the effect of COX-2 inhibition on tumour repopulation between cycles of chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Several clinical studies have been conducted in which celecoxib has been used in combination with standard chemotherapy and radiotherapy and show varying results depending on the type and stage of cancer [119]. A meta-analysis of these trials showed a modest activity against advanced cancers, but no significant effect on one-year survival rate [126]. These studies were not in the context of blocking apoptosis-induced compensatory proliferation to enhance the efficacy of therapy. Future studies to address this clinical problem are needed to define optimum treatment regimes, the sensitivity of the CSC population to specific COX-2 inhibitors, and to determine different pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics associated with chemotherapy, as some drugs may be better or poorer induces of tumour repopulation. There is also a great diversity of tumours, and it is likely that some tumour types may be more reciprocal to apoptosis-driven tumour repopulation than others.

NSAIDS and selective COX-2 inhibitors target not only COX2 activity but also suppress the biosynthesis of other physiologically important prostanoids that are associated with the adverse effects of these drugs on cardiovascular function including increased risk of myocardial infraction and stroke [127]; therefore, alternative strategies to inhibit PGE2 production that would negate the cardiovascular risk and lead to safer therapeutic tools are currently being investigated, including selective targeting of individual prostanoids via inhibition of their corresponding terminal synthases and disruption of platelet-driven COX2 induction.

An attractive target for regulation of PGE2 levels is inhibition of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1). mPGES-1 is the inducible terminal synthase in PGE2 biosynthesis and is functionally coupled to COX-2: the induction of these two enzymes leads to increased PGE2 production [128]. In cancer, mPGES-1 is overexpressed in a number of cancers including gastrointestinal, lung, stomach, brain, breast, pancreas, prostate, and papillary thyroid carcinoma [129]. Moreover, mPGES-1 expression is associated with vascular invasion and poor prognosis in colorectal cancer [130]. The therapeutic potential of mPGES-1 has been proved in multiple studies using mice models with genetic deletion of mPGES-1, in which there was a decrease in the production of PGE2 and associated pain, fever, inflammation, and tumourigenesis [131–133]. Currently there are no selective mPGES-1 inhibitors available for clinical use. However, research is ongoing to identify and characterise specific mPGES-1 inhibitors, and we would advocate that this research should extend to studies looking at these drugs in combination radiotherapy and the impact on apoptosis-driven tumour cell repopulation.

Similarly, a growing body of evidence supports the central role of platelets in metastasis. There is extensive cross-talk between platelets and cancer cells, whereby tumours can stimulate platelet activation and activated platelets, in turn, promote tumour growth and metastasis. A central event involves an aberrant expression of COX-2 in the cancer cells, which influences cell-cycle progression and contributes to the acquisition of a cell migratory phenotype through the induction of EMT gene expression profile. Platelets are also activated in response to wound healing, and they secrete a number of factors that are important mediators of tissue remodelling at the site of injury. By extension, future research should focus on the role of platelets in the tumour microenvironment, the effect on the phoenix rising pathway and to determine if pharmacological inhibition of platelet function could prevent tumour repopulation and metastasis.

5. Conclusions

Recent evidence has challenged the paradigm that apoptosis is a barrier for carcinogenesis: the common goal of standard chemotherapy and radiotherapy is to kill cancer cells by inducing apoptosis. However, apoptosis may be a double-edged sword, leading initially to increased cell death of cancer cells, but accompanied by increased PGE2 secretion and subsequent growth stimulation of CSCs and repopulation of the tumour. Repopulation during chemotherapy and radiotherapy has long been recognised as an important cause of treatment failure. Here we have presented the phoenix rising pathway as a potential driver of compensatory proliferation, and advocated that the ability of COX-2 inhibitors to selectively inhibit the proliferation of tumour cells during therapy should be evaluated. Further understanding of the biological processes of compensatory cell proliferation may give therapeutically beneficial insight into tissue repair and aid the development of new strategies to inhibit tumour repopulation during therapy and improve clinical outcomes.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Pang L. Y., Argyle D. Cancer stem cells and telomerase as potential biomarkers in veterinary oncology. Veterinary Journal. 2010;185(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pang L. Y., Argyle D. J. The evolving cancer stem cell paradigm: implications in veterinary oncology. The Veterinary Journal. 2015;205(2):154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamburger A., Salmon S. E. Primary bioassay of human myeloma stem cells. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1977;60(4):846–854. doi: 10.1172/jci108839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanahan D., Weinberg R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visvader J. E., Lindeman G. J. Cancer stem cells: current status and evolving complexities. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(6):717–728. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonnet D., Dick J. E. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nature Medicine. 1997;3(7):730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Hajj M., Wicha M. S., Benito-Hernandez A., Morrison S. J., Clarke M. F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(7):3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pang L. Y., Blacking T. M., Else R. W., et al. Feline mammary carcinoma stem cells are tumorigenic, radioresistant, chemoresistant and defective in activation of the ATM/p53 DNA damage pathway. The Veterinary Journal. 2013;196(3):414–423. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pang L. Y., Cervantes-Arias A., Else R. W., Argyle D. J. Canine mammary cancer stem cells are radio- and chemo- resistant and exhibit an epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype. Cancers. 2011;3(4):1744–1762. doi: 10.3390/cancers3021744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh S. K., Clarke I. D., Terasaki M., et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Research. 2003;63(18):5821–5828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien C. A., Pollett A., Gallinger S., Dick J. E. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445(7123):106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbs C. P., Kukekov V. G., Reith J. D., et al. Stem-like cells in bone sarcomas: implications for tumorigenesis. Neoplasia. 2005;7(11):967–976. doi: 10.1593/neo.05394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pang L. Y., Gatenby E. L., Kamida A., Whitelaw B. A., Hupp T. R., Argyle D. J. Global gene expression analysis of canine osteosarcoma stem cells reveals a novel role for COX-2 in tumour initiation. PloS ONE. 2014;9(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083144.e83144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pang L. Y., Bergkvist G. T., Cervantes-Arias A., Yool D. A., Muirhead R., Argyle D. J. Identification of tumour initiating cells in feline head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and evidence for gefitinib induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. The Veterinary Journal. 2012;193(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prince M. E. P., Ailles L. E. Cancer stem cells in head and neck squamous cell cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(17):2871–2875. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizzo S., Attard G., Hudson D. L. Prostate epithelial stem cells. Cell Proliferation. 2005;38(6):363–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2005.00356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moulay M., Liu W., Willenbrock S., et al. Evaluation of stem cell marker gene expression in canine prostate carcinoma- and prostate cyst-derived cell lines. Anticancer Research. 2013;33(12):5421–5431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bao S., Wu Q., McLendon R. E., et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444(7120):756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calabrese C., Poppleton H., Kocak M., et al. A perivascular niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2007;11(1):69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones D. L., Wagers A. J. No place like home: anatomy and function of the stem cell niche. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2008;9(1):11–21. doi: 10.1038/nrm2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mantovani A., Allavena P., Sica A., Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.del Prete A., Allavena P., Santoro G., Fumarulo R., Corsi M. M., Mantovani A. Molecular pathways in cancer-related inflammation. Biochemia Medica. 2011;21(3):264–275. doi: 10.11613/bm.2011.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coussens L. M., Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420(6917):860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balkwill F., Charles K. A., Mantovani A. Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(3):211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallo O., Masini E., Bianchi B., Bruschini L., Paglierani M., Franchi A. Prognostic significance of cyclooxygenase-2 pathway and angiogenesis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Human Pathology. 2002;33(7):708–714. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.125376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiao G., Ren T., Lu Q., et al. Prognostic significance of cyclooxygenase-2 in osteosarcoma: a meta-analysis. Tumor Biology. 2013;34(5):2489–2495. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0998-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sicking I., Rommens K., Battista M. J., et al. Prognostic influence of cyclooxygenase-2 protein and mRNA expression in node-negative breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2014;14, article 952 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duan D.-P., Dang X.-Q., Wang K.-Z., Wang Y.-P., Hui Z., You W.-L. The cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor NS-398 inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in human osteosarcoma cells via downregulation of the survivin pathway. Oncology Reports. 2012;28(5):1693–1700. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenhough A., Smartt H. J. M., Moore A. E., et al. The COX-2/PGE2 pathway: key roles in the hallmarks of cancer and adaptation to the tumour microenvironment. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(3):377–386. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mullins M. N., Lana S. E., Dernell W. S., Ogilvie G. K., Withrow S. J., Ehrhart E. J. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in canine appendicular osteosarcomas. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2004;18(6):859–865. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2004)18<859:ceicao>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naruse T., Nishida Y., Hosono K., Ishiguro N. Meloxicam inhibits osteosarcoma growth, invasiveness and metastasis by COX-2-dependent and independent routes. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(3):584–592. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urakawa H., Nishida Y., Naruse T., Nakashima H., Ishiguro N. Cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression predicts poor survival in patients with high-grade extremity osteosarcoma: A Pilot Study. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2009;467(11):2932–2938. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0814-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arjona-Sánchez Á., Ruiz-Rabelo J., Perea M. D., et al. Effects of capecitabine and celecoxib in experimental pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 2010;10(5):641–647. doi: 10.1159/000288708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howe L. R., Subbaramaiah K., Patel J., et al. Celecoxib, a selective cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor, protects against human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2)/neu-induced breast cancer. Cancer Research. 2002;62(19):5405–5407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dandekar D. S., Lopez M., Carey R. I., Lokeshwar B. L. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib augments chemotherapeutic drug-induced apoptosis by enhancing activation of caspase-3 and -9 in prostate cancer cells. International Journal of Cancer. 2005;115(3):484–492. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li F., Huang Q., Chen J., et al. Apoptotic cells activate the “phoenix rising” pathway to promote wound healing and tissue regeneration. Science Signaling. 2010;3(110, article ra13) doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurtova A. V., Xiao J., Mo Q., et al. Blocking PGE2-induced tumour repopulation abrogates bladder cancer chemoresistance. Nature. 2015;517(7533):209–213. doi: 10.1038/nature14034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Q., Yuan W., Tong D., et al. Metformin represses bladder cancer progression by inhibiting stem cell repopulation via COX2/PGE2/STAT3 axis. Oncotarget. 2016;7(19):28235–28246. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang Q., Li F., Liu X., et al. Caspase 3-mediated stimulation of tumor cell repopulation during cancer radiotherapy. Nature Medicine. 2011;17(7):860–866. doi: 10.1038/nm.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simmons D. L., Botting R. M., Hla T. Cyclooxygenase isozymes: the biology of prostaglandin synthesis and inhibition. Pharmacological Reviews. 2004;56(3):387–437. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rouzer C. A., Marnett L. J. Cyclooxygenases: structural and functional insights. The Journal of Lipid Research. 2008;50(supplement):S29–S34. doi: 10.1194/jlr.r800042-jlr200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Claria J. Cyclooxygenase-2 biology. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2003;9(27):2177–2190. doi: 10.2174/1381612033454054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cha Y. I., DuBois R. N. NSAIDs and cancer prevention: targets downstream of COX-2. Annual Review of Medicine. 2007;58(1):239–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeWitt D. L., Meade E. A., Smith W. L. PGH synthase isoenzyme selectivity: the potential for safer nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. The American Journal of Medicine. 1993;95(2):S40–S44. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90396-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turini M. E., DuBois R. N. Cyclooxygenase-2: a therapeutic target. Annual Review of Medicine. 2002;53(1):35–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.103952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harris R. E., Casto B. C., Harris Z. M. Cyclooxygenase-2 and the inflammogenesis of breast cancer. World Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;5(4):677–692. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i4.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soslow R. A., Dannenberg A. J., Rush D., et al. COX-2 is expressed in human pulmonary, colonic, and mammary tumors. Cancer. 2000;89(12):2637–2645. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001215)89:12<2637::aid-cncr17>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Subbaramaiah K., Telang N., Ramonetti J. T., et al. Transcription of cyclooxygenase-2 is enhanced in transformed mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Research. 1996;56(19):4424–4429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hwang D., Scollard D., Byrne J., Levine E. Expression of cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 in human breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1998;90(6):455–460. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.6.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hida T., Yatabe Y., Achiwa H., et al. Increased expression of cyclooxygenase 2 occurs frequently in human lung cancers, specifically in adenocarcinomas. Cancer Research. 1998;58(17):3761–3764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buckman S. Y., Gresham A., Hale P., et al. COX-2 expression is induced by UVB exposure in human skin: implications for the development of skin cancer. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19(5):723–729. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.5.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maier T. J., Schilling K., Schmidt R., Geisslinger G., Grösch S. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)-dependent and -independent anticarcinogenic effects of celecoxib in human colon carcinoma cells. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2004;67(8):1469–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams C. S., Smalley W., DuBois R. N. Aspirin use and potential mechanisms for colorectal cancer prevention. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;100(6):1325–1329. doi: 10.1172/jci119651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee E. J., Choi E. M., Kim S. R., et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 promotes cell proliferation, migration and invasion in U2OS human osteosarcoma cells. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2007;39(4):469–476. doi: 10.1038/emm.2007.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodriguez N. I., Hoots W. K., Koshkina N. V., et al. COX-2 expression correlates with survival in patients with osteosarcoma lung metastases. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2008;30(7):507–512. doi: 10.1097/mph.0b013e31816e238c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kulkarni S., Rader J. S., Zhang F., et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 is overexpressed in human cervical cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2001;7(2):429–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shamma A., Yamamoto H., Doki Y., et al. Up-regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 in squamous carcinogenesis of the esophagus. Clinical Cancer Research. 2000;6(4):1229–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Molina M. A., Sitja-Arnau M., Lemoine M. G., Frazier M. L., Sinicrope F. A. Increased cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human pancreatic carcinomas and cell lines: growth inhibition by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Cancer Research. 1999;59(17):4356–4362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kamijo T., Sato T., Nagatomi Y., Kitamura T. Induction of apoptosis by cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in prostate cancer cell lines. International Journal of Urology. 2001;8(7):S35–S39. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2001.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mohammed S. I., Knapp D. W., Bostwick D. G., et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in human invasive transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urinary bladder. Cancer Research. 1999;59(22):5647–5650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu L., Stevens J., Hilton M. B., et al. COX-2 inhibition potentiates antiangiogenic cancer therapy and prevents metastasis in preclinical models. Science Translational Medicine. 2014;6(242) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008455.242ra84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sheng H., Shao J., Morrow J. D., Beauchamp R. D., DuBois R. N. Modulation of apoptosis and Bcl-2 expression by prostaglandin E2 in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Research. 1998;58(2):362–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buchanan F. G., Wang D., Bargiacchi F., DuBois R. N. Prostaglandin E2 regulates cell migration via the intracellular activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(37):35451–35457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m302474200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Poligone B., Baldwin A. S. Positive and negative regulation of NF-kappaB by COX-2: roles of different prostaglandins. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(42):38658–38664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106599200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Foda H. D., Zucker S. Matrix metalloproteinases in cancer invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis. Drug Discovery Today. 2001;6(9):478–482. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(01)01752-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harris S. G., Padilla J., Koumas L., Ray D., Phipps R. P. Prostaglandins as modulators of immunity. Trends in Immunology. 2002;23(3):144–150. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(01)02154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goessling W., North T. E., Loewer S., et al. Genetic interaction of PGE2 and Wnt signaling regulates developmental specification of stem cells and regeneration. Cell. 2009;136(6):1136–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Méndez-Ferrer S., Michurina T. V., Ferraro F., et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466(7308):829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.North T. E., Goessling W., Walkley C. R., et al. Prostaglandin E2 regulates vertebrate haematopoietic stem cell homeostasis. Nature. 2007;447(7147):1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/nature05883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Feher I., Gidali J. Prostaglandin E2 as stimulator of haemopoietic stem cell proliferation. Nature. 1974;247(5442):550–551. doi: 10.1038/247550a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lu L., Pelus L. M., Broxmeyer H. E., et al. Enhancement of the proliferation of human marrow erythroid (BFU-E) progenitor cells by prostaglandin E requires the participation of OKT8-positive T lymphocytes and is associated with the density expression of major histocompatibiliy complex class II antigens on BFU-E. Blood. 1986;68(1):126–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lorenz M., Slaughter H. S., Wescott D. M., et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 is essential for normal recovery from 5-fluorouracil-induced myelotoxicity in mice. Experimental Hematology. 1999;27(10):1494–1502. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(99)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hoggatt J., Mohammad K. S., Singh P., et al. Differential stem- and progenitor-cell trafficking by prostaglandin E2. Nature. 2013;495(7441):365–369. doi: 10.1038/nature11929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Singh B., Cook K. R., Vincent L., Hall C. S., Martin C., Lucci A. Role of COX-2 in tumorospheres derived from a breast cancer cell line. Journal of Surgical Research. 2011;168(1):e39–e49. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kundu N., Ma X., Kochel T., et al. Prostaglandin E receptor EP4 is a therapeutic target in breast cancer cells with stem-like properties. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2014;143(1):19–31. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2779-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Majumder M., Xin X., Liu L., Girish G. V., Lala P. K. Prostaglandin E2 receptor EP4 as the common target on cancer cells and macrophages to abolish angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, metastasis, and stem-like cell functions. Cancer Science. 2014;105(9):1142–1151. doi: 10.1111/cas.12475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boodram J. N., Mcgregor I. J., Bruno P. M., Cressey P. B., Hemann M. T., Suntharalingam K. Breast Cancer Stem Cell Potent Copper(II)-non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug complexes. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2016;55(8):2845–2850. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang D., Fu L., Sun H., Guo L., DuBois R. N. Prostaglandin E2 promotes colorectal cancer stem cell expansion and metastasis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1884–1895.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bitarte N., Bandres E., Boni V., et al. MicroRNA-451 is involved in the self-renewal, tumorigenicity, and chemoresistance of colorectal cancer stem cells. Stem Cells. 2011;29(11):1661–1671. doi: 10.1002/stem.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pang L. Y., Argyle S. A., Kamida A., Morrison K. O., Argyle D. J. The long-acting COX-2 inhibitor mavacoxib (Trocoxil™) has anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects on canine cancer cell lines and cancer stem cells in vitro . BMC Veterinary Research. 2014;10(1, article 184) doi: 10.1186/s12917-014-0184-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang K. H., Kao A. P., Chang C. C., et al. Increasing CD44+/CD24− tumor stem cells, and upregulation of COX-2 and HDAC6, as major functions of HER2 in breast tumorigenesis. Molecular Cancer. 2010;9, article 288 doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huang J., Zhang D., Xie F., Lin D. The potential role of COX-2 in cancer stem cell-mediated canine mammary tumor initiation: an immunohistochemical study. Journal of Veterinary Science. 2015;16(2):225–231. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2015.16.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Deng Y., Su Q., Mo J., Fu X., Zhang Y., Lin E. H. Celecoxib downregulates CD133 expression through inhibition of the Wnt signaling pathway in colon cancer cells. Cancer Investigation. 2013;31(2):97–102. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2012.754458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Guo Z., Jiang J. H., Zhang J., et al. COX-2 promotes migration and invasion by the side population of cancer stem cell-like hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Medicine. 2015;94(44):p. e1806. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wilson H., Huelsmeyer M., Chun R., Young K. M., Friedrichs K., Argyle D. J. Isolation and characterisation of cancer stem cells from canine osteosarcoma. The Veterinary Journal. 2008;175(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Singh B., Cook K. R., Vincent L., et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 induces genomic instability, BCL2 expression, doxorubicin resistance, and altered cancer-initiating cell phenotype in MCF7 breast cancer cells. Journal of Surgical Research. 2008;147(2):240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liao K., Xia B., Zhuang Q. Y., et al. Parthenolide inhibits cancer stem-like side population of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells via suppression of the NF-κB/COX-2 pathway. Theranostics. 2015;5(3):302–321. doi: 10.7150/thno.8387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kanojia D., Zhou W., Zhang J., et al. Proteomic profiling of cancer stem cells derived from primary tumors of HER2/Neu transgenic mice. Proteomics. 2012;12(22):3407–3415. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang X., Morham S. G., Langenbach R., Baggs R. B., Young D. A. Lack of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibits growth of teratocarcinomas in mice. Experimental Cell Research. 2000;254(2):232–240. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ma H.-I., Chiou S.-H., Hueng D.-Y., et al. Celecoxib and radioresistant glioblastoma-derived CD133+ cells: improvement in radiotherapeutic effects. Laboratory investigation. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2011;114(3):651–662. doi: 10.3171/2009.11.JNS091396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pang L. Y., Argyle D. J. Veterinary oncology: biology, big data and precision medicine. The Veterinary Journal. 2016;213:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Longley D., Johnston P. Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance. The Journal of Pathology. 2005;205(2):275–292. doi: 10.1002/path.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mani S. A., Guo W., Liao M. J., et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133(4):704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Morel A. P., Lièvre M., Thomas C., Hinkal G., Ansieau S., Puisieux A. Generation of breast cancer stem cells through epithelial-mesenchymal transition. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002888.e2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Roesch A., Fukunaga-Kalabis M., Schmidt E. C., et al. A temporarily distinct subpopulation of slow-cycling melanoma cells is required for continuous tumor growth. Cell. 2010;141(4):583–594. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Charles N., Ozawa T., Squatrito M., et al. Perivascular nitric oxide activates notch signaling and promotes stem-like character in PDGF-induced glioma cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(2):141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim J. J., Tannock I. F. Repopulation of cancer cells during therapy: an important cause of treatment failure. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2005;5(7):516–525. doi: 10.1038/nrc1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Huang Z., Mayr N. A., Gao M., et al. Onset time of tumor repopulation for cervical cancer: first evidence from clinical data. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2012;84(2):478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Marcu L., van Doorn T., Olver I. Modelling of post-irradiation accelerated repopulation in squamous cell carcinomas. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2004;49(16):3767–3779. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/16/021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maciejewski B., Majewski S. Dose fractionation and tumour repopulation in radiotherapy for bladder cancer. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 1991;21(3):163–170. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(91)90033-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Suwinski R., Taylor J. M. G., Withers H. R. Rapid growth of microscopic rectal cancer as a determinant of response to preoperative radiation therapy. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 1998;42(5):943–951. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Begg A. C., Hofland I., Kummermehr J. Tumour cell repopulation during fractionated radiotherapy: correlation between flow cytometric and radiobiological data in three murine tumours. European Journal of Cancer and Clinical Oncology. 1991;27(5):537–543. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(91)90211-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hopewell J. W., Nyman J., Turesson I. Time factor for acute tissue reactions following fractionated irradiation: a balance between repopulation and enhanced radiosensitivity. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 2003;79(7):513–524. doi: 10.1080/09553000310001600907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Brockes J. P., Kumar A. Plasticity and reprogramming of differentiated cells in amphibian regeneration. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2002;3(8):566–574. doi: 10.1038/nrm881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Taub R. Liver regeneration: from myth to mechanism. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2004;5(10):836–847. doi: 10.1038/nrm1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gurtner G. C., Werner S., Barrandon Y., Longaker M. T. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453(7193):314–321. doi: 10.1038/nature07039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fan Y., Bergmann A. Distinct mechanisms of apoptosis-induced compensatory proliferation in proliferating and differentiating tissues in the Drosophila Eye. Developmental Cell. 2008;14(3):399–410. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tseng A., Adams D. S., Qiu D., Koustubhan P., Levin M. Apoptosis is required during early stages of tail regeneration in Xenopus laevis . Developmental Biology. 2007;301(1):62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hwang J. S., Kobayashi C., Agata K., Ikeo K., Gojobori T. Detection of apoptosis during planarian regeneration by the expression of apoptosis-related genes and TUNEL assay. Gene. 2004;333:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chera S., Ghila L., Dobretz K., et al. Apoptotic cells provide an unexpected source of Wnt3 signaling to drive hydra head regeneration. Developmental Cell. 2009;17(2):279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zimmerman M. A., Huang Q., Li F., Liu X., Li C.-Y. Cell death-stimulated cell proliferation: a tissue regeneration mechanism usurped by tumors during radiotherapy. Seminars in Radiation Oncology. 2013;23(4):288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Michalak E. M., Vandenberg C. J., Delbridge A. R., et al. Apoptosis-promoted tumorigenesis: γ-irradiation-induced thymic lymphomagenesis requires Puma-driven leukocyte death. Genes & Development. 2010;24(15):1608–1613. doi: 10.1101/gad.1940110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Labi V., Erlacher M., Krumschnabel G., et al. Apoptosis of leukocytes triggered by acute DNA damage promotes lymphoma formation. Genes and Development. 2010;24(15):1602–1607. doi: 10.1101/gad.1940210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Qiu W., Wang X., Leibowitz B., Yang W., Zhang L., Yu J. PUMA-mediated apoptosis drives chemical hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Hepatology. 2011;54(4):1249–1258. doi: 10.1002/hep.24516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Allen C. P., Tinganelli W., Sharma N., et al. DNA damage response proteins and oxygen modulate prostaglandin E2 growth factor release in response to low and high LET ionizing radiation. Frontiers in Oncology. 2015;5, article 260 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kwang W. K., Hwang M., Moretti L., Jaboin J. J., Cha Y. I., Lu B. Autophagy upregulation by inhibitors of caspase-3 and mTOR enhances radiotherapy in a mouse model of lung cancer. Autophagy. 2008;4(5):659–668. doi: 10.4161/auto.6058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Moretti L., Kim K. W., Jung D. K., Willey C. D., Lu B. Radiosensitization of solid tumors by Z-VAD, a pan-caspase inhibitor. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2009;8(5):1270–1279. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.mct-08-0893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Liu X., He Y., Li F., et al. Caspase-3 promotes genetic instability and carcinogenesis. Molecular Cell. 2015;58(2):284–296. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Salehifar E., Hosseinimehr S. J. The use of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors for improvement of efficacy of radiotherapy in cancers. Drug Discovery Today. 2016;21(4):654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Liu B., Qu L., Yan S. Cyclooxygenase-2 promotes tumor growth and suppresses tumor immunity. Cancer Cell International. 2015;15(1, article 106) doi: 10.1186/s12935-015-0260-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Patrignani P., Patrono C. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors: from pharmacology to clinical read-outs. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2015;1851(4):422–432. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zhang S. X., Qiu Q. H., Chen W. B., Liang C. H., Huang B. Celecoxib enhances radiosensitivity via induction of G2-M phase arrest and apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2014;33(5):1484–1497. doi: 10.1159/000358713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Blanquicett C., Saif M. W., Buchsbaum D. J., et al. Antitumor efficacy of capecitabine and celecoxib in irradiated and lead-shielded, contralateral human BxPC-3 pancreatic cancer xenografts: clinical implications of abscopal effects. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(24, part 1):8773–8781. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-05-0627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yang M. Y., Lee H. T., Chen C. M., Shen C. C., Ma H. I. Celecoxib suppresses the phosphorylation of STAT3 protein and can enhance the radiosensitivity of medulloblastoma-derived cancer stem-like cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014;15(6):11013–11029. doi: 10.3390/ijms150611013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Inoue T., Anai S., Onishi S., et al. Inhibition of COX-2 expression by topical diclofenac enhanced radiation sensitivity via enhancement of TRAIL in human prostate adenocarcinoma xenograft model. BMC Urology. 2013;13, article 1 doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-13-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Chen J., Shen P., Zhang X. C., Zhao M. D., Yang L. Efficacy and safety profile of celecoxib for treating advanced cancers: a meta-analysis of 11 randomized clinical trials. Clinical Therapeutics. 2014;36(8):1253–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Korotkova M., Jakobsson P. Characterization of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 inhibitors. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2014;114(1):64–69. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Jakobsson P. J., Thoren S., Morgenstern R., Samuelsson B. Identification of human prostaglandin E synthase: a microsomal, glutathione-dependent, inducible enzyme, constituting a potential novel drug target. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(13):7220–7225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Chang H. H., Meuillet E. J. Identification and development of mPGES-1 inhibitors: where we are at? Future Medicinal Chemistry. 2011;3(15):1909–1934. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Seo T., Tatsuguchi A., Shinji S., et al. Microsomal prostaglandin e synthase protein levels correlate with prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Virchows Archiv. 2009;454(6):667–676. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0777-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Trebino C. E., Stock J. L., Gibbons C. P., et al. Impaired inflammatory and pain responses in mice lacking an inducible prostaglandin E synthase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(15):9044–9049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332766100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kamei D., Murakami M., Nakatani Y., Ishikawa Y., Ishii T., Kudo I. Potential role of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 in tumorigenesis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(21):19396–19405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m213290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kamei D., Yamakawa K., Takegoshi Y., et al. Reduced pain hypersensitivity and inflammation in mice lacking microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(32):33684–33695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m400199200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]