Abstract

Laparoscopic rectal surgery has demonstrated its superiority over the open approach, however it still has some technical limitations that lead to the development of robotic platforms. Nevertheless the literature on this topic is rapidly expanding there is still no consensus about benefits of robotic rectal cancer surgery over the laparoscopic one. For this reason a review of all the literature examining robotic surgery for rectal cancer was performed. Two reviewers independently conducted a search of electronic databases (PubMed and EMBASE) using the key words “rectum”, “rectal”, “cancer”, “laparoscopy”, “robot”. After the initial screen of 266 articles, 43 papers were selected for review. A total of 3013 patients were included in the review. The most commonly performed intervention was low anterior resection (1450 patients, 48.1%), followed by anterior resections (997 patients, 33%), ultra-low anterior resections (393 patients, 13%) and abdominoperineal resections (173 patients, 5.7%). Robotic rectal surgery seems to offer potential advantages especially in low anterior resections with lower conversions rates and better preservation of the autonomic function. Quality of mesorectum and status of and circumferential resection margins are similar to those obtained with conventional laparoscopy even if robotic rectal surgery is undoubtedly associated with longer operative times. This review demonstrated that robotic rectal surgery is both safe and feasible but there is no evidence of its superiority over laparoscopy in terms of postoperative, clinical outcomes and incidence of complications. In conclusion robotic rectal surgery seems to overcome some of technical limitations of conventional laparoscopic surgery especially for tumors requiring low and ultra-low anterior resections but this technical improvement seems not to provide, until now, any significant clinical advantages to the patients.

Keywords: Robotic surgery, Robotic rectal surgery, DaVinci rectal surgery, Robotic rectal cancer, Robotics for rectal cancer, Robotic rectal resection

Core tip: Laparoscopic rectal surgery has progressively expanded. However it has some technical limitations. The need to overcome these limitations leads to the development of robotic platforms. Although the positive feedback is by the surgeons, there is still no evidence in literature about the superiority of robotic rectal surgery when compared to traditional laparoscopy.

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic colorectal surgery has progressively expanded since a number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs)[1-3], review articles[4,5], meta-analysis[6] and case series[7] have demonstrated its better postoperative outcomes when compared to open surgery. However, laparoscopic surgery has some technical limitations such as poor ergonomics, 2-dimension view, coning and fulcrum effect, that may influence surgery in narrow anatomical fields such as in the pelvis during rectal surgery. The need to overcome these limitations leads to the development of robotic platforms. The da Vinci robotic surgical system is the only totally robotic platform available. After approval by Food and Drug Administration in 2000, its use progressively spreaded as demonstrated by the increasing number of publications. Three-D high definition vision, wrist-like movement of instruments (endowristTM), stable camera holding, motion filter for tremor-free surgery and improved ergonomics for the surgeon are the advantages of the robotic system that may make rectal surgery more affordable and theoretically should provide better outcomes for the patient. Although the positive feedback is by the surgeons, there is still no evidence in literature about the superiority of robotic rectal surgery when compared to traditional laparoscopy. The aim of this study was to review the rapidly expanding literature in order to focus on the current state and assess any benefits of robotic rectal cancer surgery.

RESEARCH AND LITERATURE

A review of the literature examining robotic surgery for rectal cancer during the period from 2000 to 2015 was performed. Two reviewers independently conducted a search of electronic databases (PubMed and EMBASE) using the key words “rectum”, “rectal”, “cancer”, “laparoscopy”, “robot”. The reference lists provided by the identified articles were additionally hand-searched to prevent article loss by the search strategy. This method of cross-references was continued until no further relevant publications were identified. The last search was performed on December 2015. Inclusion criteria were prospective, retrospective, randomized, comparative studies about robotic rectal surgery for cancer including anterior resections, low anterior resections, ultralow anterior resections, abdominoperineal resections, proctectomies, proctocolectomies. Exclusion criteria were: Abstracts, letters, editorials, technical notes, expert opinions, reviews, meta-analysis, studies reporting benign pathologies, studies in which the outcomes and parameters of patients were not clearly reported, studies in which it was not possible to extract the appropriate data from the published results, overlap between authors and centers in the published literature, non-English language papers.

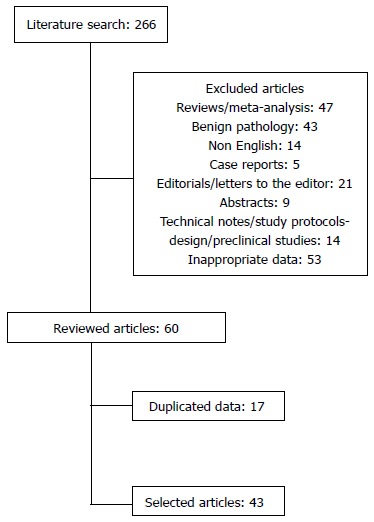

The literature search yielded 266 papers, the process is listed in Figure 1. After the 1st filtering, the remaining 60 studies were 33 comparative, 26 case series, and 1 RCT. Then 17 studies were excluded due to duplicated data. They were 7 comparative and 9 case series. After this process a total of 43 papers, 27 comparative including only 1 RCT and 16 case series were included and reviewed.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search.

STUDIES OVERVIEW

The number of publications about robotic rectal surgery for cancer has been constantly increasing. Among the papers we included there was only 1 paper per year published in 2006, 2007, 2008, 3 papers in 2009, 2 in 2010, 5 per year in 2011 and 2012, 10 in 2013 and 15 in 2014. With regard to the nationality of the 1st author there were 16 studies in the South Korea (37.2%), 11 in the United States (25.5%), 4 in Italy (9.3%), 2 in Turkey (4.6%), 2 in the Singapore (4.6%), 1 in Japan (2.3%), 1 in Denmark (2.3%), 1 in Spain (2.3%), 1 in Romania (2.3%), 1 in Brazil (2.3%), 1 in Canada (2.3%), 1 in Taiwan (2.3%), 1 in China (2.3%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Studies overview

| Ref. | Year | Country | Study design | Surgical technique | Platform | No. of pts Robot | No. of pts Lap | No. of pts Open |

| Park et al[8] | 2015 | South Korea | Comparative | Hybrid | DV | 133 | 84 | |

| Levic et al[9] | 2014 | Denmark | Comparative | NS | DV | 56 | 36 | |

| Yoo et al[10] | 2014 | South Korea | Comparative | Tot rob | NS | 44 | 26 | |

| Koh et al[11] | 2014 | Singapore | Comparative | NS | NS | 19 | 19 | |

| Melich et al[12] | 2014 | Canada | Comparative | Tot rob | DV | 92 | 106 | |

| Barnajian et al[13] | 2014 | United States | Comparative | Hybrid | DV-S | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Ielpo et al[14] | 2014 | Spain | Comparative | Tot rob | NS | 56 | 87 | |

| Tam et al[15] | 2014 | United States | Comparative | Hybrid | DV | 21 | 21 | |

| Ghezzi et al[16] | 2014 | Brazil | Comparative | Tot rob | DV-S | 65 | 109 | |

| Kuo et al[17] | 2014 | Taiwan | Comparative | Tot rob | DV | 36 | 28 | |

| Park et al[18] | 2014 | South Korea | Comparative | Hybrid | DV | 32 | 32 | |

| Saklani et al[19] | 2013 | South Korea | Comparative | NS | NS | 74 | 64 | |

| Fernandez et al[20] | 2013 | United States | Comparative | Hybrid | DV-S | 13 | 59 | |

| Erguner et al[21] | 2013 | Turkey | Comparative | Hybrid | NS | 27 | 37 | |

| D’Annibale et al[22] | 2013 | Italy | Comparative | Tot rob | DV-S | 50 | 50 | |

| Kang et al[23] | 2013 | South Korea | Comparative | Tot rob | NS | 165 | 165 | 165 |

| Park et al[24] | 2013 | South Korea | Comparative | Hybrid | DV | 40 | 40 | |

| Kim et al[25] | 2012 | South Korea | Comparative | Tot rob | DV | 62 | 147 | |

| Kim et al[26] | 2012 | South Korea | Comparative | Hybrid | DV | 30 | 39 | |

| Bertani et al[27] | 2011 | Italy | Comparative | Tot rob | DV | 52 | 34 | |

| Kwak et al[28] | 2011 | South Korea | Comparative | Tot rob | DV | 59 | 59 | |

| Baek et al[29] | 2011 | United States | Comparative | NS | NS | 41 | 41 | |

| Park et al[30] | 2011 | South Korea | Comparative | Hybrid | DV | 52 | 123 | 88 |

| Patriti et al[31] | 2009 | Italy | Comparative | Hybrid | DV | 29 | 37 | |

| Baik et al[32] | 2008 | South Korea | Comparative | Hybrid | DV | 18 | 18 | |

| Pigazzi et al[33] | 2006 | United States | Comparative | Hybrid | DV | 6 | 6 | |

| Parisi et al[34] | 2014 | Italy | Case series | Hybrid | DV Si | 40 | ||

| Baek et al[35] | 2014 | South Korea | Case series | NS | NS | 182 | ||

| Shiomi et al[36] | 2014 | Japan | Case series | Hybrid | DV | 113 | ||

| Kim et al[37] | 2014 | South Korea | Case series | Tot rob | DV-S | 200 | ||

| Stănciulea et al[38] | 2013 | Romania | Case series | Tot rob | DV-Si | 100 | ||

| Zawadzki et al[39] | 2013 | United States | Case series | Hybrid | DV | 77 | ||

| Sng et al[40] | 2013 | South Korea | Case series | Tot rob | DV-S | 197 | ||

| Du et al[41] | 2013 | China | Case series | Tot rob | DV | 22 | ||

| Alimoglu et al[42] | 2012 | Turkey | Case series | Tot rob | DV | 7 | ||

| Akmal et al[43] | 2012 | United States | Case series | Hybrid | DV | 80 | ||

| Park et al[44] | 2012 | United States | Case series | Hybrid | DV-S | 30 | ||

| Kang et al[45] | 2011 | South Korea | Case series | Hybrid | DV | 389 | ||

| deSouza et al[46] | 2010 | United States | Case series | Hybrid | DV | 44 | ||

| Pigazzi et al[47] | 2010 | United States | Case series | Hybrid | DV | 143 | ||

| Choi et al[48] | 2009 | South Korea | Case series | Tot rob | DV | 50 | ||

| Ng et al[49] | 2009 | Singapore | Case series | Hybrid | DV | 8 | ||

| Hellan et al[50] | 2007 | United States | Case series | Hybrid | DV | 39 |

Tot rob: Totally Robotic; DV: Da Vinci; NS: Not specified.

Surgical technique

A total of 3013 robotic operations were performed. Sixteen studies[10,12,14,16,17,22,23,25,27,28,37,38,40-42,48] (1257 patients) reported a totally robotic procedure which was carried out with either a single[10,16,17,22,23,25,27,28,37,38,40-42,48] or a double docking[12,28] technique. In 22 studies[8,13,15,18,20,21,25,26,30-34,36,39,43-47,49,50] (1384 patients) an hybrid robotic technique was performed: The inferior mesenteric vessels ligation and splenic flexure mobilization were performed laparoscopically whereas pelvic dissection and total mesorectal excision were performed robotically. In 5 studies[9,11,19,29,35] (372 patients) the robotic technique was not specified. Laparoscopic procedures described in the 27 comparative studies[8-33] were performed in the same manner as robotic surgery using laparoscopic instruments (Table 1).

Demographics and preoperative data

Most of patients were male (1911, 63%), the mean age was 58, the mean BMI was 26.6. Nine hundred-eight patients (20%) underwent a neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 71 (2.3%) a neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy and 8 (0.2%) radiotherapy only. With regard to the type of operation, 1450 (48.1%) were low anterior resections, 997 (33%) were anterior resections (AR), 393 (13%) ultra-low anterior resections (ULAR) and 173 (5.7%) abdominoperineal resections (APR). In the studies where the type of operation was not specified and where it was stated that a TME was performed[27,29,41] we assumed that all operations were low anterior resections (LAR) (Table 2)

Table 2.

Demographics and preoperative data

| Ref. | M/F | Age | BMI |

ASA |

Preop CHT |

Type of operation |

||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | AR | LAR | ULAR | APR | |||||

| Park et al[8] | 86/47 | 59.2 (32-86) | 23.1 (14.6-32.8) | 94 | 31 | 8 | 0 | 15 | 100 | 33 | 0 | 0 |

| Levic et al[9] | 34/22 | 65 (23-83) | 24.8 (16-34.5) | 17 | 35 | 4 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 411 | 0 | 15 |

| Yoo et al[10] | 35/9 | 59.77 (+ 12.33) | 24.13 (+ 3.33) | 26 | 17 | 1 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 44 | 0 |

| Koh et al[11] | 15/4 | 62 (47-92) | - | 5 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 2 |

| Melich et al[12] | 52/40 | 60 (57.7-62.2) | 23.1 (22.5-23.7) | 1 (1-3) | 13 | 0 | 92 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Barnajian et al[13] | 12/8 | 62 (44-82) | 22 (18-31) | 0 | 4 | 16 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 5 |

| Ielpo et al[14] | 25/31 | 43.4 (+ 11) | 22.8 (+ 2.5) | 11 | 32 | 11 | 0 | 46 | 0 | 40 | 1 | 15 |

| Tam et al[15] | 10/11 | 60 (41-73) | 25 (20-37) | _ | _ | _ | _ | 18 | 11 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Ghezzi et al[16] | 41/24 | 61 | 24.7 | 12 | 49 | 4 | 0 | 47 | 0 | 44 | 11 | 102 |

| Kuo et al[17] | 21/15 | 55.9 (30-89) | - | 0 | 33 | 3 | 0 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 0 |

| Park et al[18] | 32/0 | - | 23.8 | - | - | - | - | 15 (+ RT) | 0 | 22 | 9 | 1 |

| Saklani et al[19] | 50/24 | 59.6 (32-85) | 23.4 (16.9-29.8) | 50 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 74 | 0 | 46 | 26 | 2 |

| Fernandez et al[20] | 13/0 | 67.9 (+ 2.1) | - | 0 | 0 | 11 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 8 |

| Erguner et al[21] | 14/13 | 54 (24-78) | 28.3 (19.8-30.8) | - | - | - | - | 4 | 0 | 27 | 0 | 0 |

| D’Annibale et al[22] | 30/20 | 66 (+ 12.1) | - | - | - | - | - | 34 (+ RT) | 17 | 33 | 0 | 0 |

| Kang et al[23] | 104/61 | 61.2 (+ 11.4) | 23.1 (+ 2.8) | 109 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 39 | 1653 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Park et al[24] | 41/21 | 56 | 24.2 | 33 | 28 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 51 | 10 | 1 |

| Kim et al[25] | 28/12 | 57.3 | 23.9 | 27 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 |

| Kim et al[26] | 18/12 | 54.13 (+ 8.52) | 24.36 (+ 2.4) | 29 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 29 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Bertani et al[27] | 31/21 | 59.6 (+ 11.6) | 24.8 (+ 3.62) | 49 | 3 | 24 | 0 | 52 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Kwak et al[28] | 39/20 | 60 (53-68) | 23.3 (21.8-25.2) | 28 | 27 | 4 | 0 | 8 (RT) | 0 | 54 | 5 | 0 |

| Baek et al[29] | 25/16 | 63.6 (48-87) | - | 0 | 18 | 22 | 1 | 33 | 0 | 33 | 2 | 6 |

| Park et al[30] | 28/24 | 57.3 | 23.7 | 21 | 26 | 5 | 0 | 12 (+ RT) | 52 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Patriti et al[31] | 11/18 | 68 | 24 | 2 | 13 | 14 | 0 | 7 (+ RT) | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Baik et al[32] | 14/4 | 57.3 (37-79) | 22.8 (19.4-31.7) | 12 | 6 | 0 | 0 | - | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pigazzi et al[33] | 2/4 | 60 (42-78) | 31 (25-36) | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Parisi et al[34] | 19/21 | 67 (39-86) | 25.22 (18.36-33.20) | 20 | 14 | 6 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 35 | 0 | 5 |

| Baek et al[35] | 117/65 | 57.6 (26-78) | 23.4 (14.8-30.5) | 111 | 65 | 6 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 182 | 0 | 0 |

| Shiomi et al[36] | 78/35 | 64 (23-84) | 23.4 (16.7-30.6) | 39 | 74 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 11 | 71 | 23 | 8 |

| Kim et al[37] | 134/66 | 58.15 | 23.85 | - | - | - | - | 43 | 0 | 200 | 0 | 0 |

| Stănciulea et al[38] | 66/34 | 62 (32-84) | 26 (16.4-38) | - | - | - | - | 58 | 30 | 39 | 8 | 23 |

| Zawadzki et al[39] | 45/32 | 60.1 (34-82) | 28 (18-43) | 62 | 15 | 0 | 48 | 0 | 68 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Sng et al[40] | 131/66 | 60 (20-89) | 23.5 (16.9-33.1) | 117 | 71 | 9 | 0 | 54 | 3 | 126 | 55 | 13 |

| Du et al[41] | 14/8 | 56.4 (+ 7.8) | 22.5 (+ 2.1) | - | - | - | - | - | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Alimoglu et al[42] | 5/2 | 52.9 (32-88) | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Akmal et al[43] | 50/30 | 60.35 (24-85) | 27.2 (18-44) | 0 | 37 | 39 | 4 | 62 | 0 | 40 | 21 | 19 |

| Park et al[44] | 16/14 | 58 | 27.6 | 0 | 12 | 18 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 5 | 19 | 6 |

| Kang et al[45] | 252/137 | 59 (26-86) | - | 280 | 107 | 2 | 0 | 72 | 382 | 13 | 0 | 6 |

| deSouza et al[46] | 28/16 | 63 | - | 4 | 27 | 13 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 30 | 6 | 8 |

| Pigazzi et al[47] | 87/56 | 62 (26-87) | 26.5 (16.5-44) | 0 | 0 | 57 | 93 (+ RT) | 0 | 80 | 32 | 31 | 0 |

| Choi et al[48] | 32/18 | 58.5 (30-82) | 23.2 (19.4-29.2) | 27 | 19 | 4 | 0 | 3 (+ RT) | 0 | 40 | 8 | 2 |

| Ng et al[49] | 5/3 | 55 (42-80) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Hellan et al[50] | 21/18 | 58 (26-84) | 26 (16-44) | 0 | 0 | 17 | 33 | 0 | 22 | 11 | 6 | |

9 hartmann;

1 Posterior pelvic exenteration;

1 hartmann. AR: Anterior resections; ULAR: Ultra-low anterior resections; APR: Abdominoperineal resections; CHT: Chemotheraypy; BMI: Body mass index; ASA: American society anesthesiologists.

Operative data

The mean robotic operative time ranged from 202 min[31] to 485.8 min[17]. For the 1345 laparoscopic patients in the selected comparative studies the mean operative time ranged from 158.1[30] to 374.3 min[17]. This difference was statistically significant in 12 comparative studies[10,14,17-24,27,28,30] with a longer time for robotic surgery. Levic et al[9] were the only authors that reported a longer laparoscopic operative time (P = 0.055), but all interventions were performed with a single port technique (Table 3).

Table 3.

Operative data

| Ref. | Patients | Mesorectum | Technique | Mean operative time (min) | EBL (mL) | Conversion to open (%) | Stoma (%) |

| Park et al[8] | 133 | RME | Hybrid | 205.7 (109-505) | 77.6 (0-700) | 0 (0) | 29 (21.8) |

| 84 | LME | Tot lap | 208.8 (94-407) | 82.3 (0-1100) | 6 (7.1) | 20 (23.8) | |

| Levic et al[9] | 56 | RME | NS | 247 (135-111)1 | 50 (0-400)1 | 3 (5.4) | 31 (55.3) |

| 36 | LME | SP | 295 (108-465)1 | 35 (0-400)1 | 0 (0) | 9 (25) | |

| Yoo et al[10] | 44 | RME | Tot rob | 316.43 (+ 65.11) | 239.77 (+ 278.61) | 0 (0) | 44 (100) |

| 26 | LME | Tot lap | 286.77 (+ 51.46) | 215.38 (+ 247.29) | 0 (0) | 26 (100) | |

| Koh et al[11] | 19 | RME | NS | 390 (289-771)1 | - | 1 (5.2) | 17 (89) |

| 19 | LME | HAL | 225 (130-495)1 | - | 5 (26.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Melich et al[12] | 92 | RME | Tot rob | 285 (266-305) | 201 (165-237) | 1 (1.1) | - |

| 106 | LME | Tot lap | 262 (252-272) | 232 (191-272) | 4 (3.8) | - | |

| Barnajian et al[13] | 20 | RME | Hybrid | 240 (150-540)1 | 125 (50-650)1 | 0 (0) | 11 (55) |

| 20 | LME | Tot lap | 180 (140-480)1 | 175 (50-900)1 | 2 (10.5) | 11 (55) | |

| 20 | OME | Open | 240 (115-475)1 | 250 (50-800)1 | na | 12 (60) | |

| Ielpo et al[14] | 56 | RME | Tot rob | 309 (150-540) | 280 (0-4000) | 2 (3.5) | 28 (50) |

| 87 | LME | Tot lap | 252 (180-420) | 240 (0-4000) | 10 (11.5) | 53 (60.9) | |

| Tam et al[15] | 21 | RME | Hybrid | 274.8 (189-449) | 252.6 (30-2000) | 1 (4.7) | 13 (62) |

| 21 | LME | Tot lap | 236.3 (171-360) | 271.4 (50-1200) | 0 (0) | 11 (52) | |

| Ghezzi et al[16] | 65 | RME | Tot rob | 299 (+ 58) | 0 (0-175)1 | 1 (1.5) | 51 (91.1) |

| 109 | OME | Open | 207 (+ 56.5) | 150 (0-400)1 | na | 66 (63.3) | |

| Kuo et al[17] | 36 | RME | NS | 485.8 (315-720) | 80 (30-200) | 0 (0) | 7 (19.4) |

| 28 | LME | Tot lap | 374.3 (210-570) | 103.6 (30-250) | 0 (0) | 13 (46.4) | |

| Park et al[18] | 32 | RME | Hybrid | - | - | - | 3 (9.4) |

| 32 | LME | Tot lap | - | - | - | 3 (9.4) | |

| Saklani et al[19] | 74 | RME | NS | 365.2 (150-710) | 180 (0-1100) | 1 (1.4) | 53 (71.6) |

| 64 | LME | Tot lap | 311.6 (180-530) | 210 (0-1200) | 4 (6.3) | 35 (54.7) | |

| Fernandez et al[20] | 13 | RME | Hybrid | 528 (416-700)1 | 157 (50-550)1 | 1 (8) | - |

| 59 | LME | HAL | 344 (183-735)1 | 200 (25-1500)1 | 10 (17) | - | |

| Erguner et al[21] | 27 | RME | Hybrid | 280 (175-480) | 50 (20-100) | 0 (0) | 19 (70.3) |

| 37 | LME | Tot lap | 190 (110-300) | 125 (50-400) | 0 (0) | 13 (35.1) | |

| D’Annibale et al[22] | 50 | RME | Tot rob | 270 (240-315)1 | - | 0 (0) | - |

| 50 | LME | Tot lap | 280 (240-350)1 | - | 6 (12) | - | |

| Kang et al[23] | 165 | RME | Tot rob | 309.7 (+ 115.2) | 133 (+ 192.3) | 1 (0.6) | 41 (25) |

| 165 | LME | Tot lap | 277.8 (+ 81.9) | 140.1 (+ 216.4) | 3 (1.8) | 43 (27.2) | |

| 165 | OME | Open | 252.6 (+ 88.1) | 275.4 (+ 368.4) | na | 47 (31.8) | |

| Kim et al[25] | 62 | RME | Tot rob | 390 (+ 97) | - | 3 (4.8) | 22 (35.5) |

| 147 | LME | Tot lap | 285 (+ 80) | - | 5 (3.4) | 34 (23.1) | |

| Park et al[24] | 40 | RME | Hybrid | 235.5 (+ 57.5) | 45.7 (+ 40) | 0 (0) | 14 (35) |

| 40 | LME | Tot lap | 185.4 (+ 72.8) | 59.2 (+ 35.8) | 0 (0) | 6 (15) | |

| Kim et al[26] | 30 | RME | Hybrid | - | - | - | - |

| 39 | LME | Tot lap | - | - | - | - | |

| Bertani et al[27] | 52 | RME | Tot rob | 260 (190-570) | 100 (50-1000) | - | - |

| 34 | OME | Tot lap | 164 (100-350) | 120 (50-2000) | - | - | |

| Kwak et al[28] | 59 | RME | Tot rob | 270 (241-325)1 | - | 0 (0) | 25 (42.4) |

| 59 | LME | Tot lap | 228 (177-254)1 | - | 2 (3.4) | 26 (44.1) | |

| Baek et al[29] | 41 | RME | NS | 296 (150-520) | 200 (20-2000)1 | 3 (7.3) | 33 (94.3) |

| 41 | LME | NS | 315 (174-584) | 300 (17-1000)1 | 9 (22) | 14 (40) | |

| Park et al[30] | 52 | RME | Hybrid | 232.6 (+ 54.2) | - | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) |

| 123 | LME | Tot lap | 158.1 (+ 49.2) | - | 0 (0) | 5 (4.1) | |

| 88 | OME | Open | 233.8 (+ 59.2) | - | na | 4 (4.5) | |

| Patriti et al[31] | 29 | RME | Hybrid | 202 (+ 12) | 137.4 (+ 156) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 37 | LME | Tot lap | 208 (+ 7) | 127 (+ 169) | 7 (19) | 0 (0) | |

| Baik et al[32] | 18 | RME | Hybrid | 217.1 (149-315) | - | 0 (0) | - |

| 18 | LME | Tot lap | 204.3 (114-297) | - | 2 (11) | - | |

| Pigazzi et al[33] | 6 | RME | Hybrid | 264 (192-318) | 104 (50-200) | 0 (0) | - |

| 6 | LME | Tot lap | 258 (198-312) | 150 (50-300) | 0 (0) | - | |

| Parisi et al[34] | 40 | RME | Hybrid | 340 (235-460)1 | 50 (20-250)1 | 0 (0) | 22 (55) |

| Baek et al[35] | 182 | RME | NS | - | - | - | - |

| Shiomi et al[36] | 113 | RME | Hybrid | 302 (135-683)1 | 17 (0-690)1 | 0 (0) | - |

| Kim et al[37] | 200 | RME | Tot rob | 308.3 | - | 1 (0.5) | 9 (4.5) |

| Stănciulea et al[38] | 100 | RME | Tot rob | - | 150 (0-250)1 | 4 (4) | 64 (64) |

| Zawadzki et al[39] | 77 | RME | Hybrid | 327 (178-510)1 | 189 (30-1000)1 | 3 (3.9) | 53 (69) |

| Sng et al[40] | 197 | RME | Tot rob | 278.7 (145-515) | < 50 (50-1500)1 | 0 (0) | - |

| Du et al[41] | 22 | RME | Tot rob | 220 (152-286) | 33 (10-70) | 0 (0) | - |

| Alimoglu et al[42] | 7 | RME | Tot rob | - | - | 0 (0) | - |

| Akmal et al[43] | 80 | RME | Hybrid | 303.5 | - | 4 (5) | 46 (57.5) |

| Park et al[44] | 30 | RME | Hybrid | 369 (306-410)1 | 100 (75-200)1 | - | - |

| Kang et al[45] | 389 | RME | Hybrid | 322.35 | - | 3 (0.7) | 93 (24) |

| deSouza et al[46] | 44 | RME | Hybrid | 347 (155-510)1 | 150 (50-1000)1 | - | 34 (77.2) |

| Pigazzi et al[47] | 143 | RME | Hybrid | 297 (90-660) | 283 (0-6000) | 7 (4.9) | 71 (50) |

| Choi et al[48] | 50 | RME | T Tot rob | 304.8 (190-485) | - | 0 (0) | 16 (32) |

| Ng et al[49] | 8 | RME | Hybrid | 278.7 (145-515) | - | 0 (0) | 6 (75) |

| Hellan et al[50] | 39 | RME | Hybrid | 285 (180-540)1 | 200 (25-6000)1 | 1 (2.5) | 4 (10.2) |

Tot rob: Totally robotic; Tot lap: Totally laparoscopic; HAL: Hand assisted laparoscopy; SP: Single port; NS: Not specified.

Median. EBL: Estimated blood loss; RME: Robotic mesorectal excision; LME: Laparoscopic mesorectal excision; OME: Open mesorectal excision.

The estimated blood loss (EBL) was not reported in 14 studies. The mean value ranged from 17 mL[36] to 280 mL[14] with the robotic approach and from 59.2[18] to 271.4[15] in the laparoscopic group. Among 16 comparative studies[8-10,12-15,17,19-21,23,24,29,31,33] that evaluated the EBL only Kang et al[23] and Erguner et al[21] reported a significantly lower EBL with the robotic approach when compared to the laparoscopic one.

Thirty seven studies reported the conversion rate to open surgery. Three[8,22,31] out of 22 comparative studies[8-15,17,19-25,28-33] showed a significantly lower conversion rate in the robotic series when compared to laparoscopy. The difference in overall conversion rate reported by Ielpo et al[14] was not statistically significant. However, when data were analyzed according to the tumor location (upper, mid, lower rectum), the conversion rates between robotic and laparoscopic procedures for lower rectal cancers were respectively 1.8% and 9.2% (P = 0.04).

The rate of patients that underwent a protective ileostomy creation ranged from 0%[30] to 100%[10] both in the robotic and laparoscopic group. The difference in protective ileostomy creation was statistically significant in 5 studies. Kuo et al[17] reported a lower rate in the robotic vs the laparoscopic group whereas Saklani et al[19], Erguner et al[21], Kim et al[25], Baek et al[29] showed a lower rate in the laparoscopic vs the robotic group.

Postoperative data

The mean postoperative day to first flatus ranged from 1.9[48] to 3.2[30] d in the robotic cases and from 2.4[23] to 3.4[17] in the laparoscopic ones. No statistically significant difference between robotic and laparoscopic cases was reported in any of the articles reviewed (Table 4).

Table 4.

Postop data

| Ref. | Pts | Mesorectum | Flatus (POD) | Liquid diet (POD) | Solid diet (POD) | Length of stay (d) | 30 d mortality (%) | Reinterventions (%) | |

| Park et al[8] | 133 | RME | 2.42 (1-6) | - | 4.92 (3-11) | 5.86 (4-14) | 0 (0) | - | |

| 84 | LME | 2.47 (1-6) | - | 5.19 (2-11) | 6.54 (3-25) | 0 (0) | - | ||

| Levic et al[9] | 56 | RME | - | - | - | 8 (4-100) | 0 (0) | - | |

| 36 | LME | - | - | - | 7 (3-51) | 2 (5.6) | - | ||

| Yoo et al[10] | 44 | RME | - | - | 2.58 (+ 1.62) | 11.41 (+ 5.56) | 0 (0) | - | |

| 26 | LME | - | - | 2.48 (+ 1.53) | 11.04 (+ 6.33) | 0 (0) | - | ||

| Koh et al[11] | 19 | RME | - | - | - | 7 (4-21)1 | 0 (0) | 1 (5.2) | Bleeding |

| 19 | LME | - | - | - | 6 (4-28)1 | 0 (0) | 3 (15.7) | Adhesive SBO, colonic infarction, anastomotic leak | |

| Melich et al[12] | 92 | RME | - | - | - | 9.6 (8.3-11) | - | 6 (6.5) | 6 leak/abscess |

| 106 | LME | - | - | - | 9.9 (8.5-11.3) | - | 5 (4.7) | 4 leak/abscess, 1 obstruction due to adhesions | |

| Barnajian et al[13] | 20 | RME | 3 (1-8)1 | - | 4 (2-9)1 | 6 (4-31)1 | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | Presacral bleeding, pelvic abscess |

| 20 | LME | 4 (3-13)1 | - | 4 (4-14)1 | 7 (5-36)1 | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | Pancreatic tail injury | |

| 20 | OME | 4 (2-8)1 | - | 4.5 (2-9)1 | 7 (3-16)1 | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | Presacral bleeding, enterotomy | |

| Ielpo et al[14] | 56 | RME | - | - | - | 13 (5-60) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.3) | NS |

| 87 | LME | - | - | - | 10 (5-16) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.4) | NS | |

| Tam et al[15] | 21 | RME | - | - | - | 8.7 (4-23) | - | 0 (0) | |

| 21 | LME | - | - | - | 6 (3-14) | - | 1 (5) | Bleeding | |

| Ghezzi et al[16] | 65 | RME | 2 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | - | 6 (5-8)1 | 0 (0) | 3 (4.6) | NS |

| 109 | OME | 3 (2-5) | 5 (4-6) | - | 9 (8-10)1 | 0 (0) | 2 (1.8) | NS | |

| Kuo et al[17] | 36 | RME | 2.9 (1-6) | - | 6.4 (4-12) | 14.2 (9-27) | - | - | |

| 28 | LME | 3.4 (1-11) | - | 5.8 (3-16) | 15.1 (7-57) | - | - | ||

| Park et al[18] | 32 | RME | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 32 | LME | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Saklani et al[19] | 74 | RME | 2.45 (1-10) | - | 4.6 (2-13) | 8 (4-21) | 0 (0) | - | |

| 64 | LME | 2.48 (1-6) | - | 5.1 (2-14) | 9.2 (5-29) | 0 (0) | - | ||

| Fernandez et al[20] | 13 | RME | - | - | - | 131 | 0 (0) | 2 (15) | SBO |

| 59 | LME | - | - | - | 81 | 1 (2) | 7 (12) | NS | |

| Erguner et al[21] | 27 | RME | - | - | - | - | 1 (3.7) | 1 (3.7) | Colonic necrosis |

| 37 | LME | - | - | - | - | 1 (2.7) | 3 (8.1) | 1 ileostomy retraction, 2 anastomotic leak | |

| D’Annibale et al[22] | 50 | RME | - | 3 (3-5)1 | - | 8 (7-11)1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 50 | LME | - | 5 (4-6)1 | - | 10 (8-14)1 | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | Anastomotic leak | |

| Kang et al[23] | 165 | RME | 2.2 (+ 1.1) | - | 4.5 (+ 1.9) | 10.8 (+ 5.5) | 0 (0) | 15 (9) | NS |

| 165 | LME | 2.4 (+ 1.2) | - | 5.2 (+ 2.4) | 13.5 (+ 9.2) | 0 (0) | 5 (15) | NS | |

| 165 | OME | 3 (+ 1.4) | - | 6.4 (+ 2.5) | 16 (+ 8.6) | 0 (0) | 9 (5.4) | NS | |

| Kim et al[25] | 62 | RME | - | - | 6 (+ 5) | 12 (+ 6) | - | - | |

| 147 | LME | - | - | 7 (+ 5) | 14 (+ 9) | - | - | ||

| Park et al[24] | 40 | RME | 2.4 (+ 1.6) | - | 7.5 (+ 3.5) | 10.6 (+ 4.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | Anastomotic leak |

| 40 | LME | 2.5 (+ 1.3) | - | 7.7 (+ 2.3) | 11.3 (+ 3.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | Anastomotic leak | |

| Kim et al[26] | 30 | RME | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 39 | LME | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Bertani et al[27] | 52 | RME | 2 (1-5) | 2 (1-13) | - | 6 (4-51)1 | - | 2 (4) | |

| 34 | OME | 3 (1-9) | 3 (2-12) | - | 7 (4-24)1 | - | 0 (0) | ||

| Kwak et al[28] | 59 | RME | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 59 | LME | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Baek et al[29] | 41 | RME | - | 2.3 (1-13) | - | 6.5 (2-33) | 0 (0) | - | |

| 41 | LME | - | 2.4 (1-9) | - | 6.6 (3-20) | 0 (0) | - | ||

| Park et al[30] | 52 | RME | 3.2 (+ 1.8) | - | 6.7 (+ 3.8) | 10.4 (+ 4.7) | 0 (0) | - | |

| 123 | LME | 3 (+ 1.1) | - | 6.1 (+ 2.7) | 9.8 (+ 3.8) | 0 (0) | - | ||

| 88 | OME | 4.4 (+ 3) | - | 7.6 (+ 3.3) | 12.8 (+ 7.1) | 1 (1.1) | - | ||

| Patriti et al[31] | 29 | RME | - | - | - | 11.9 (6-29) | 0 (0) | - | - |

| 37 | LME | - | - | - | 9.6 (5-37) | 0 (0) | - | - | |

| Baik et al[32] | 18 | RME | 1.8 (1-2)1 | - | - | 6.9 (5-10)1 | - | 0 (0) | |

| 18 | LME | 2.4 (1-6)1 | - | - | 8.7 (6-12)1 | - | 0 (0) | ||

| Pigazzi et al[33] | 6 | RME | - | - | - | 4.5 (3-11) | - | 0 (0) | |

| 6 | LME | - | - | - | 3.6 (3-6) | - | 0 (0) | ||

| Parisi et al[34] | 40 | RME | 1 (1-3)1 | 1 (1-5)1 | 2 (2-6)1 | 5 (3-18)1 | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | Anastomotic leak |

| Baek et al[35] | 182 | RME | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Shiomi et al[36] | 113 | RME | 2 (1-3)1 | 3 (3-7)1 | - | 7 (6-24)1 | 0 (0) | 2 (1.8) | Anastomotic leak |

| Kim et al[37] | 200 | RME | 2.4 | - | 5 | 10.7 | 16 (8) | ns | |

| Stănciulea et al[38] | 100 | RME | - | - | - | 10 (6-38)1 | - | 6 (6) | 3 anastomotic leak, 1 bowel obstruction, 1 bleeding, 1 bowel injury |

| Zawadzki et al[39] | 77 | RME | - | - | - | 6.4 (3-26) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.9) | Anastomotic leak |

| Sng et al[40] | 197 | RME | - | - | - | 9 (5-122)1 | - | - | |

| Du et al[41] | 22 | RME | 2.6 (1.41-4.37)1 | - | - | 7.8 (7-13)1 | - | - | |

| Alimoglu et al[42] | 7 | RME | - | - | - | 8.1 (5-10)1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Akmal et al[43] | 80 | RME | - | 2.75 (1-19) | - | 7.55 (2-33) | 0 (0) | - | |

| Park et al[44] | 30 | RME | - | - | - | 4 (3-6)1 | 0 (0) | - | |

| Kang et al[45] | 389 | RME | 2.3 | 3.9 | - | 13.5 | 0 (0) | 36 (9.2) | ns |

| deSouza et al[46] | 44 | RME | - | - | - | 5 (3-36)1 | 1 (0.46) | 2 (0.92) | 1 anastomotic leak |

| Pigazzi et al[47] | 143 | RME | - | 2.7 (1-19) | - | 8.3 (2-33) | 0 (0) | - | |

| Choi et al[48] | 50 | RME | 1.9 (1-3) | 2.6 (2-12) | - | 9.2 (5-24) | - | 0 (0) | |

| Ng et al[49] | 8 | RME | - | - | - | 5 (4-30)1 | 0 (0) | - | - |

| Hellan et al[50] | 39 | RME | - | 2 (1-11)1 | - | 4 (2-22)1 | 0 (0) | 4 (10.3) | Anastomotic leak |

Values are expressed as mean, solid diet includes soft diet. SBO: Small bowel obstruction; RME: Robotic mesorectal excision; LME: Laparoscopic mesorectal excision; OME: Open mesorectal excision; POD: Post operative day.

The day of first postoperative liquid diet was available in 11 studies[6,22,27,29,34,36,43,45,47,48,50] ranging from 1[16] to 3.9[45] d in the robotic cases. Only two[22,29] comparative studies reported the first postoperative liquid diet in their robotic and laparoscopic series, in one[22] of these the difference was statistically significant in favour of robotic surgery (3 d vs 5 d, P = 0.005).

The day of first postoperative solid diet was available in 11 studies[8,10,13,17,19,23-25,30,34,37] ranging from 2.58[10] to 7.5[18] d in the robotic cases and from 2.48[10] to 7.7[18] d in laparoscopic cases. Among 9 comparative studies[8,10,13,17,19,23-25,30] only Kang et al[23] reported a significant earlier oral intake in the robotic group (4.5 d vs 5.2 d. P = 0.004) when compared to the laparoscopic one.

The mean length of hospital stay ranged from 4.5[33] to 14.2[17] and from 3.6[33] to 15.1[17] d after robotic and laparoscopic surgery respectively. Among 8 comparative studies, Tam et al[15], Levic et al[9] and Park et al[30] reported a shorter length of stay in their laparoscopic series whereas 5[8,22-24,32] studies reported a significant shorter length of stay after robotic surgery.

No statistically significant differences in the overall 30 d mortality between the robotic and laparoscopic approach was found among 15 comparative studies[8-11,13,14,19-24,29-31] (0.10% and 0.45% respectively).

Twenty-three studies reported the reintervention rate. In the robotic series it ranged from 0%[8,22,32,33,42,48] to 15%[20] whereas it ranged from 0%[32,33] to 15.7%[11] after laparoscopic surgery. The most common cause of reintervention was anastomotic leak in both the robotic and laparoscopic groups. No statistically significant differences were found in any of the 12 comparative studies[11-15,20-24,32,33].

The overall complication rate in the robotic and laparoscopic groups was 24.5% and 27.7% respectively. No significant differences in this parameter were reported between the robotic and laparoscopic series[8-11,13-15,19-25,28-33]. The most frequent complication in both the robotic and laparoscopic cases was anastomotic leak followed by bowel obstruction and urinary complications (Table 5). Thirteen studies[10,18,19,22-24,26,31,37,38,40,44,45] reported urinary and sexual dysfunction after rectal surgery, 9 of these were comparative. Park et al[18] reported an earlier and significant restoration of erectile function after robotic surgery when compared to the laparoscopic one. Kim et al[26] observed an earlier recover of urinary function after robotic intervention within six months from the operation (P = 0.001). After 6 mo the difference was no more statistically significant.

Table 5.

Complications according to Clavien Dindo classification

| Ref. | Pts | Mesorectum | Complicated pts (%) | 1 (%) | 2 (%) |

3 (%) |

4 (%) | 5 (%) | |

| 3a | 3b | ||||||||

| Park et al[8] | 133 | RME | 26 (19.5) | 11 (42.3) | 5 (19.2) | 9 (34.6) | 1 (3.8) | ||

| 84 | LME | 19 (22.6) | 7 (36.8) | 4 (21) | 6 (31.6) | 2 (10.5) | |||

| Yoo et al[10] | 44 | RME | 17 (38.6) | 13 (76.5) | 4 (23.5) | ||||

| 26 | LME | 7 (26.9) | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.5) | |||||

| Koh et al[11] | 19 | RME | 3 (15.7) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | ||||

| 19 | LME | 7 (36.8) | 4 (57) | 3 (43) | |||||

| Melich et al[12] | 92 | RME | 17 (18.4) | 11 (64.7) | 6 (35.3) | ||||

| 106 | LME | 18 (17) | 13 (72.2) | 5 (27.8) | |||||

| Barnajian et al[13] | 20 | RME | 8 (40) | 3 | 3 (37.5) | 2 (25) | |||

| 20 | LME | 4 (10) | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 20 | OME | 8 (40) | 5 | 2 | 1 (33.3) | ||||

| Ielpo et al[14] | 56 | RME | 15 (26.8) | 11 (73.3) | 4 (26.7) | ||||

| 87 | LME | 20 (23) | 15 (75) | 5 (25) | |||||

| Ghezzi et al[16] | 65 | RME | 27 (41.5) | 22 (81.5) | 5 (18.5) | ||||

| 109 | OME | 45 (41.3) | 38 (84.5) | 7 (15.5) | |||||

| Kuo et al[17] | 36 | RME | 11 (30.5) | 4 (36.3) | 3 (27.2) | 4 (36.3) | |||

| 28 | LME | 14 (50) | 11 (78.6) | 1 (7) | 2 (14.2) | ||||

| Fernandez et al[20] | 13 | RME | 2 | ||||||

| 59 | LME | ||||||||

| Erguner et al[21] | 27 | RME | 3 (11.1) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | ||||

| 37 | LME | 8 (21.6) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | |||||

| D’Annibale et al[22] | 50 | RME | 5 (10) | 5 (100) | |||||

| 50 | LME | 10 (20) | 7 (70) | 3 (30) | |||||

| Kang et al[23] | 165 | RME | 34 (20.6) | 16 (47.1) | 3 (8.8) | ||||

| 165 | LME | 46 (27.9) | 20 (43.5) | 1 (2.2) | |||||

| 165 | OME | 41 (24.8) | 30 (73.2) | 2 (4.9) | |||||

| Park et al[24] | 40 | RME | 6 (15) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | ||||

| 40 | LME | 5 (12.5) | 4 (80) | 1 (20) | |||||

| Park et al[30] | 52 | RME | 10 (19.2) | 6 (60) | 4 (40) | ||||

| 123 | LME | 15 (12.2) | 9 (60) | 6 (40) | |||||

| 88 | OME | 18 (20.5) | 9 (50) | 9 (50) | |||||

| Baik et al[32] | 18 | RME | 4 (22.2) | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | ||||

| 18 | LME | 1 (5.5) | 1 (100) | ||||||

| Pigazzi et al[33] | 6 | RME | 1 (16.6) | 1 (100) | |||||

| 6 | LME | 1 (16.6) | 1 (100) | ||||||

| Parisi et al[34] | 40 | RME | 4 (10) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | |||

| Shiomi et al[36] | 113 | RME | 23 (20.3) | 10 (43.5) | 10 (43.5) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (8.7) | ||

| Kim et al[37] | 200 | RME | 16 (59.2) | ||||||

| Stănciulea et al[38] | 100 | RME | 18 (18) | 10 (55.5) | 2 (5.5) | 6 (38.9) | |||

| Zawadzki et al[39] | 77 | RME | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Sng et al[40] | 197 | RME | 74 (37) | 58 (78.3) | 5 (6.8) | 9 (12.1) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Du et al[41] | 22 (4.5) | RME | 1 (4.5) | 1 (100) | 0 | ||||

| Alimoglu et al[42] | 7 | RME | 2 (28.5) | 2 (100) | |||||

| Kang et al[45] | 389 | RME | 74 (19) | 34 (45.9) | 4 (5.4) | 36 (48.6) | |||

| deSouza et al[46] | 44 | RME | 19 (43) | 15 (79) | 1 (5.2) | 1 (5.2) | 1 (5.2) | 1 (5.2) | |

| Choi et al[48] | 50 | RME | 9 (18) | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.5) | ||||

| Hellan et al[50] | 39 | RME | 15 (38.4) | 11 (73.3) | 4 (26.7) | ||||

RME: Robotic mesorectal excision; LME: Laparoscopic mesorectal excision; OME: Open mesorectal excision.

Table 6 shows the studies which classified complications according to the Clavien Dindo Scoring System. Clavien-Dindo 1 and 2 were the most frequent complications in both groups (13.8% robotic vs 12.4% laparoscopic).

Table 6.

Short term oncologic outcomes

| Ref. | Pts | Mesorectum | DSF% (yr) | LR (%) | Distant metastases (%) | OS % (yr) | F-u mo (median) |

| Park et al[8] | 133 | RME | 81.9 (5) | 3 (2.3) | 16 (12) | 92.8 (5) | 58 (4-80) |

| 84 | LME | 78.7 (5) | 1 (1.2) | 14 (16.6) | 93.5 (5) | 58 (4-80) | |

| Levic et al[9] | 56 | RME | 0 (0) | 8 (14.3) | 12 (1-31) | ||

| 36 | LME | 0 (0) | 2 (5.6) | 10 (1-33) | |||

| Yoo et al[10] | 431 | RME | 76.7 (3) | 6 (12.8) | 95.2 (3) | 33.9 (4.4-61.3) | |

| 26 | LME | 75 (3) | 2 (8.3) | 88.5 (3) | 36.5 (3.7-69.9) | ||

| Ghezzi et al[16] | 65 | RME | 73.2 (5) | 2 (3.2) | 19 (29.6) | 85 (5) | 60 |

| 109 | OME | 69.5 (5) | 17.5 (16.1) | 26 (24.2) | 76.1 (5) | 60 | |

| Saklani et al[19] | 74 | RME | 77.7 (3) | 2 (2.7) | 90 (3) | 30.1 (11-61)2 | |

| 64 | LME | 78.8 (3) | 4 (6.3) | 92.1 (3) | 30.1 (11-61)2 | ||

| Kim et al[25] | 62 | RME | 0 (0) | 3 (4.2) | 98 (1.5) | 17.4 | |

| 147 | LME | 1 (0.7) | 8 (5.4) | 98 (1.7) | 20.6 | ||

| Kwak et al[28] | 59 | RME | 1 (1.8) | 2 (3.6) | 17 (11-25) | ||

| 59 | LME | 1 (1.9) | 2 (3.7) | 13 (9-22) | |||

| Patriti et al[31] | 29 | RME | 100 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 96.6 (2.4) | 29.22 |

| 37 | LME | 83.7 (3) | 2 (5.4) | 4 (6) | 97.2 (1.5) | 18.72 | |

| Stănciulea et al[38] | 100 | RME | 2 (2) | 90 (3) | 24 (9-63) | ||

| Alimoglu et al[42] | 7 | RME | 100 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 100 (1) | 12 (6-21)2 |

| Pigazzi et al[47] | 143 | RME | 77.6 (3) | 2 (1.4) | 13 (9) | 97 (3) | 17.4 (0.1-52.5)2 |

1 patient excluded (palliative ISR);

Mean. DSF: Disease free survival rate; LR: Local recurrence; OS: Overall survival; RME: Robotic mesorectal excision; LME: Laparoscopic mesorectal excision; OME: Open mesorectal excision.

Oncological outcome

The mean number of harvested nodes ranged from 10[14] to 20.6[48] and from 9[14] to 21[10] in the robotic and laparoscopic cases respectively. Three of 22 comparatives[8-15,17,19-25,28-33] studies reported a statistically significant difference in the number of harvested nodes between the robotic and laparoscopic approach: Levic et al[9] and D’Annibale et al[22] showed an higher number of examined nodes after robotic surgery whereas Yoo et al[10] showed an higher number of examined nodes after laparoscopic surgery (Table 7).

Table 7.

Histopathological data

| Ref. | Pts | Mesorectum | Harvested nodes | Quality of mesorectum (complete) | Proximal margin (mm) | Distal margin (mm) | Distal margin + (%) | CRM (mm) | CRM + (%) |

pTpN stage (%) |

||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Park et al[8] | 133 | RME | 16.34 (2-43) | - | 111.7 (40-350) | 27.5 (10-140) | 0 (0) | - | 9 (6.8) | 0 (0) | 49 (36.8) | 36 (27.1) | 48 (36.1) | 0 (0) |

| 84 | LME | 16.63 (2-49) | - | 105.1 (40-340) | 28.7 (10-90) | 0 (0) | - | 6 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 22 (26.2) | 28 (33.3) | 34 (40.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Levic et al[9] | 56 | RME | 21 (7-83)1 | 34 | - | 30 (5-80) | 1 (0.56) | 9 (0-60)1 | - | 3 (5.4) | 12 (21.4) | 20 (35.7) | 21 (37.5) | 0 (0) |

| 36 | LME | 13 (3-33)1 | 26 | - | 30 (5-75) | 0 (0) | 10 (1-43)1 | - | 1 (2.8) | 6 (16.7) | 15 (41.7) | 14 (38.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Yoo et al[10] | 44 | RME | 13.93 (+ 9.27) | - | 225.2 (+ 102.5) | 13.3 (+ 9.7) | - | - | 4 (9.1) | 5 (11.4) | 14 (31.8) | 11 (25) | 9 (20.5) | 5 (11.4) |

| 26 | LME | 21.42 (+ 15.71) | - | 208.4 (+ 89.5) | 16.7 (+ 30) | - | - | 5 (19.2) | 1 (3.8) | 7 (26.9) | 8 (30.8) | 8 (30.8) | 2 (7.7) | |

| Koh et al[11] | 19 | RME | 16 (4-24)1 | 19 | - | - | 1 (5.2) | - | 1 (5.2) | 2(10.5) | 3 (15.7) | 4 (21) | 9 (47.3) | 1 (5.2) |

| 19 | LME | 14 (5-27)1 | 19 | - | - | 0 (0) | - | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (26.3) | 4 (21) | 9 (47.3) | 1 (5.2) | |

| Melich et al[12] | 92 | RME | 17.2 (15-19.5) | - | - | - | 1 (1.1) | - | 3 (3.3) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 106 | LME | 16.3 (14.4-18.1) | - | - | - | 0 (0) | - | 3 (2.8) | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Barnajian et al[13] | 20 | RME | 14 (3-22)1 | 16 | - | 20.5 (5-50)1 | - | 10.5 (1-30)1 | - | 0 (0) | 6 (40) | 4 (25) | 10 (35) | 0 (0) |

| 20 | LME | 11 (4-18)1 | 19 | - | 21.5 (1-55)1 | - | 4 (0-30)1 | - | 0 (0) | 7 (35) | 3 (15) | 10 (50) | 0 (0) | |

| 20 | OME | 12 (4-20)1 | 19 | - | 20.5 (1-45)1 | - | 8 (0-30)1 | - | 0 (0) | 8 (40) | 3 (15) | 9 (45) | 0 (0) | |

| Ielpo et al[14] | 56 | RME | 10 (0-29) | - | - | - | - | - | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 14 (25) | 21 (37.5) | 21 (37.5) | 0 (0) |

| 87 | LME | 9 (0-17) | - | - | - | - | - | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 19 (21.8) | 38 (43.6) | 30 (34.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Tam et al[15] | 21 | RME | 19.7 (8-40) | - | - | 460 (10-180) | 0 (0) | - | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 5 (24) | 4 (19) | 9 (43) | 1 (5) |

| 21 | LME | 14.8 (8-21) | - | - | 510 (5-80) | 1 (5) | - | 1 (5%) | 3 (14) | 7 (33) | 4 (19) | 7 (33) | 0 (0) | |

| Ghezzi et al[16] | 65 | RME | 20.1 | - | - | 27 (16-44) | - | - | 0 (0) | 10 (15.4) | 5 (7.7) | 17 (26.2) | 27 (41.5) | 6 (9.2) |

| 109 | OME | 14.1 | - | - | 22 (15-30) | - | - | 2 (1.8) | 15 (13.8) | 10 (9.2) | 38 (34.9) | 42 (38.5) | 4 (3.7) | |

| Kuo et al[17] | 36 | RME | 14 (2-33) | - | - | 22 (4-42) | 0 (0) | 6.7 (0-18) | 4 (11.1) | 7 (19.4) | 4 (11.1) | 11 (30.5) | 14 (38.8) | 0 (0) |

| 28 | LME | 13.9 (3-31) | - | - | 17.9 (1-60) | 1 (3.6) | 7 (0-16) | 4 (14.2) | 6 (21.4) | 2 (7.1) | 8 (28.6) | 12 (42.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Park et al[18] | 32 | RME | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 32 | LME | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Saklani et al[19] | 74 | RME | 11.6 (1-36) | - | 128 (50-240) | 17 (1-60) | - | - | 3 (4) | 18 (24.3) | 16 (21.6) | 22 (29.7) | 18 (24.3) | 0 (0) |

| 64 | LME | 14.7 (1-27) | - | 140 (55-280) | 22 (2-70) | - | - | 1 (1.6) | 8 (12.5) | 13 (20.3) | 23 (35.9) | 20 (31.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Fernandez et al[20] | 13 | RME | 16 | 9 | - | - | 0 (0) | - | 0 (0) | - | - | - | - | |

| 59 | LME | 20 | 24 | - | - | 1 (2) | - | 1 (2) | - | - | - | - | ||

| Erguner et al[21] | 27 | RME | 16 (3-38) | 19 | 120 (40-180) | 40 (30-80) | 0 (0) | 4 (2-8) | - | 0 (0) | 15 (55.5) | 11 (40.7) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0) |

| 37 | LME | 16 (3-31) | 17 | 140 (45-230) | 25 (5-50) | 0 (0) | 4 (1-10) | - | 0 (0) | 17 (46) | 16 (43.2) | 4 (10.8) | 0 (0) | |

| D’Annibale et al[22] | 50 | RME | 16.5 (11-44) | - | - | 30 (20-70) | - | - | 0 (0) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 50 | LME | 13.8 (4-29) | - | - | 30 (10-60) | - | - | 6 (12) | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Kang et al[23] | 165 | RME | 15 (+ 9.4) | - | 120 (+ 49) | 19 (+ 14) | 0 (0) | - | 7 (4.2) | 4 (2.4) | 56 (33.9) | 51 (30.9) | 54 (32.7) | 0 (0) |

| 165 | LME | 15.6 (+ 9.1) | - | 113 (+ 51) | 20 (+ 17) | 0 (0) | - | 11 (6.7) | 9 (5.4) | 55 (33.1) | 47 (28.5) | 54 (32.7) | 0 (0) | |

| 165 | OME | 17.4 (+ 10.9) | - | 114 (+ 55) | 22 (+ 17) | 0 (0) | - | 17 (10.3) | 14 (8.5) | 55 (33.3) | 41 (24.8) | 55 (33.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Kim et al[25] | 62 | RME | 16 (+ 10) | - | - | 30 (+ 14) | - | - | 2 (3.2) | 4 (6.5) | 17 (27.4) | 16 (25.8) | 24 (38.7) | 0 (0) |

| 147 | LME | 16 (+ 9) | - | - | 25 (+ 16) | - | - | 4 (2.7) | 6 (4.1) | 55 (37.7) | 35 (24) | 46 (31.5) | 4 (2.7) | |

| Park et al[24] | 40 | RME | 12.9 (+7.5) | - | 198 (+ 69) | 14 (+ 9) | 0 (0) | 6.2 (4.7) | 3 (7.5) | 0 (0) | 19 (47.5) | 9 (22.5) | 11 (27.7) | 1 (2.5) |

| 40 | LME | 13.3 (+8.6) | - | 213 (+ 139) | 13 (+ 9) | 0 (0) | 6.9 (5.1) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 13 (32.5) | 15 (37.5) | 11 (27.5) | 1 (2.5) | |

| Kim et al[26] | 30 | RME | - | 29 | - | 27.9 (+ 10.2) | 0 (0) | - | 2 (6) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 39 | LME | - | 37 | - | 28.6 (+ 13.6) | 0 (0) | - | 1 (2.5) | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Bertani et al[27] | 52 | RME | 20.5 (5-43)1 | - | - | 26 (1-70) | - | - | 2 (4) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 34 | OME | 16 (6-46)1 | - | - | 26 (1-80) | - | - | 2 (6) | - | - | - | - | ||

| Kwak et al[28] | 59 | RME | 20 (12-27)1 | - | - | 22 (15-30) | 0 (0) | - | 1 (1.7) | 3 (5.1) | 16 (27.1) | 23 (39) | 13 (22) | 4 (6.8) |

| 59 | LME | 21 (14-28)1 | - | - | 20 (12-35) | 0 (0) | - | 0 (0) | 3 (5.1) | 16 (27.1) | 23 (39) | 12 (20.3) | 5 (8.5) | |

| Baek et al[29] | 41 | RME | 13.1 (3.33) | - | - | 36 (4-100) | 0 (0) | - | 1 (2.4) | 7 (17.1) | 12 (29.3) | 4 (9.8) | 15 (36.6) | 3 (7.3) |

| 41 | LME | 16.2 (5-39) | - | - | 38 (4-110) | 0 (0) | - | 2 (4.9) | 3 (7.3) | 15 (36.6) | 3 (7.3) | 19 (46.3) | 1 (2.4) | |

| Park et al[30] | 52 | RME | 19.4 (+ 10.2) | - | 165 (+ 60) | 28 (+ 19) | 0 (0) | 7.9 (+ 4.5) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 15 (28.8) | 15 (28.8) | 22 (42.3) | 0 (0) |

| 123 | LME | 15.9 (+ 10.1) | - | 169 (+ 84) | 32 (+ 21) | 0 (0) | 8.2 (+ 5.8) | 3 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 34 (27.6) | 52 (42.3) | 37 (30.1) | 0 (0) | |

| 88 | OME | 18.5 (+ 10.9) | - | 124 (+ 66) | 23 (+ 15) | 0 (0) | 8.5 (+ 5.7) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 27 (30.7) | 32 (36.4) | 29 (33) | 0 (0) | |

| Patriti et al[31] | 29 | RME | 10.3 (+ 4) | - | - | 21 (+ 9) | - | - | - | 0 (0) | 11 (38) | 9 (31) | 7 (24.1) | 2 (6.9) |

| 37 | LME | 11.2 (+ 5) | - | - | 45 (+ 72) | - | - | - | 0 (0) | 17 (46) | 8 (21.6) | 10 (27.2) | 2 (5.4) | |

| Baik et al[32] | 18 | RME | 20 (6-49) | 17 | 109 (75-200) | 40 (10-55) | - | - | 0 (0) | 5 (27.8) | 4 (22.2) | 9 (50) | 0 (0) | |

| 18 | LME | 17.4 (9-42) | 13 | 103 (55-85) | 37 (15-60) | - | - | - | 0 (0) | 5 (27.8) | 4 (22.2) | 9 (50) | 0 (0) | |

| Pigazzi et al[33] | 6 | RME | 14 (9-28) | - | - | 38 (18-90) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6 | LME | 17 (9-39) | - | - | 35 (22-50) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Parisi et al[34] | 40 | RME | 19 (6-35)1 | 32 | 118.5 (65-390)1 | 40 (20-80)1 | 0 (0) | - | - | 2 (5) | 10 (25) | 9 (22.5) | 19 (47.5) | 0 (0) |

| Baek et al[35] | 182 | RME | 14.8 (2-47) | - | - | 22 (+ 14.3) | - | - | 10 (5.5) | 5 (2.7) | 57 (31.3) | 52 (28.5) | 62 (34) | 6 (3.3) |

| Shiomi et al[36] | 113 | RME | 32 (11-112)1 | 113 | 180 (65-376) | 26 (5-100) | 0 (0) | - | 0 (0) | 5 (4.4) | 35 (31) | 28 (24.7) | 38 (33.6) | 7 (6.2) |

| Kim et al[37] | 200 | RME | 16.1 | - | 132.5 | 22 | 0 (0) | - | 2 (1) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Stănciulea et al[38] | 100 | RME | 14 (4-32)1 | - | - | 30 (2-70)1 | - | - | - | 5 (5) | 24 (24) | 43 (43) | 21 (21) | 7 (7) |

| Stănciulea et al[38] | 77 | RME | 12.9 (3-45) | - | - | - | 2 (2.6) | - | 1 (1.2) | 26 (34) | 8 (10) | 15 (19) | 26 (34) | 2 (3) |

| Sng et al[40] | 197 | RME | 16 (1-80)1 | - | - | 17 (0-8.3)1 | - | - | 2 (2.5) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Du et al[41] | 22 | RME | 14.3 (8-27)1 | 19 | - | 26 (10-55) | - | - | - | 0 (0) | 1 (4.5) | 9 (40.9) | 12 (54.5) | 0 (0) |

| Alimoglu et al[42] | 7 | RME | 16 (14-21) | - | - | - | - | - | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (42.8) | 1 (14.2) | 3 (42.8) | 0 (0) |

| Akmal et al[43] | 80 | RME | 14.2 (2-33) | - | - | 32.5 (2-100) | - | 1.8 (0-45) | - | 15 (18.8) | 20 (25) | 12 (15) | 27 (33.8) | 5 (6.3) |

| Park et al[44] | 30 | RME | 20 (14-25)1 | 25 | - | - | - | 11 (5-20) | 0 (0) | 6 (20) | 7 (23.3) | 4 (13.3) | 10 (33.3) | 3 (10) |

| Kang et al[45] | 389 | RME | 15.7 (+ 10) | - | 11.7 | 2.15 | - | - | 14 (3.6) | 24 (6.2) | 122 (31.4) | 103 (26.5) | 140 (36) | 0 (0) |

| deSouza et al[46] | 44 | RME | 14 (5-45) | - | - | - | 1 (2.7) | - | 0 (0) | 4 (9.1) | 14 (31.8) | 15 (34.1) | 8 (18.2) | 3 (6.8) |

| Pigazzi et al[47] | 143 | RME | 14.1 (1-39) | - | - | 29 (0-100) | - | 19 (1-45) | 1 (0.7) | 18 (12.6) | 36 (25.2) | 36 (25.2) | 53 (37) | 0 (0) |

| Choi et al[48] | 50 | RME | 20.6 (6-48) | - | - | 19 (5-45) | 0 (0) | - | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 10 (20) | 19 (38) | 19 (38) | 2 (4) |

| Ng et al[49] | 8 | RME | 15 (2-26)1 | - | - | - | - | - | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 0 |

| Hellan et al[50] | 39 | RME | 13 (7-28)1 | - | - | 26.5 (4-75)1 | 0 (0) | - | 0 (0) | 8 (20.5) | 13 (33.3) | 4 (10.3) | 13 (33.3) | 1 (2.6) |

Median. RME: Robotic mesorectal excision; LME: Laparoscopic mesorectal excision; OME: Open mesorectal excision.

The mean length of distal resection margins after robotic rectal surgery was available in 20 studies[8-10,13,15-17,19,21-38,40,41,43,45,48,50]. It ranged from 13.3 mm[10] to 460 mm[15]. Tumor involvement rate of distal margins was available 21 studies[8,9,11,12,15,17,20,21,23,25,26,28-30,34,36,37,39,46,48,50] and ranged from 0%[8,15,17,20,21,25,26,28-30,34,36,37,48,50] to 2.6%[39] of patients. An involvement of distal resection margin was found in 6 (0.47%) out of 1257 patients operated on with the robotic technique.

The mean length of distal resection margins after laparoscopic rectal surgery was available in 19[8-10,13,15,17,19,21-26,28-33] studies. It ranged from 13 mm[25] to 510 mm[15]. The involvement of distal margins was available in 14 studies[8,9,11,12,15,17,20,21,23,25,26,28-30] and ranged from 0%[8,9,11,12,15,21,23,25,26,28-30] to 5%[15] of patients. A distal margin positivity was reported in 3 (0.3%) out of 857 patients. Among the 19 comparative[8-10,13,15,17,19,21-26,28-33] studies only Park et al[24] reported a longer distal margin in the robotic than in the laparoscopic group (P = 0.04). No significant difference in distal margins tumor involvement was reported when the robotic and laparoscopic approaches were compared.

Mean circumferential resection margins (CRM) after robotic rectal surgery were reported in 9 studies[9,13,17,21,25,30,43,44,47] ranging from 1.8 mm[43] to 11 mm[44]. CRM tumor involvement was available in 32 studies[8,10-12,14-17,19,20,22-30,35-37,39,40,42,44-50] and ranged from 0%[15,16,20,22,36,42,44,46,49,50] to 11.1%[17] of patients with a 2.94 overall rate (76 out of 2583 patients).

Mean CRM after laparoscopic rectal surgery were reported in 6[9,13,17,21,25,30] comparative studies. It ranged from 4 mm[21] to 8.2 mm[30]. CRM involvement was reported in 17 studies[8,10-12,14,15,17,19,20,22-26,28-30] and occurred in 51 out of 1158 patients (4.4%) Where the 2 procedures where compared only D’Annibale et al[22] observed a significantly greater number of patients with positive CRM in the laparoscopic series when compared with the robotic one.

Only in 11 papers[9,11,13,20,21,26,32,34,36,41,44] reported the quality of mesorectum. Complete mesorectum excision ranged from 100%[11,36] to 60%[9] in the robotic series and from 100%[11] to 40.6%[9] after laparoscopy. Total mesorectal excision was achieved in 83.62% of robotic cases vs 77.22% of laparoscopic ones. None of the 7 comparative studies showed a significant difference in the quality of mesorectum between the 2 procedures.

Short-term oncologic outcomes

Only 11 authors[8-10,16,19,25,28,31,38,42,47] reported short term oncologic outcomes (Table 8). The main drawback is the heterogeneity of the length of follow up ranging from 1 mo[9,42] to 80 mo[8] making results difficult to compare. The disease free survival in the laparoscopic group ranged from 75%[10] to 89.2%[31] with local recurrence ranging from 0%[9,42] to 16.6%[8] and an overall survival ranging from 88.5%[10] to 98%[24]. The disease free survival in the robotic group ranged from 70.4%[16] to 100%[31,42] with local recurrence ranging from 0%[9,31,42] to 12.8%[10] and an overall survival ranging from 85%[16] to 100%[42].

Table 8.

Short term oncologic outcomes

| Ref. | Pts | Mesorectum | DSF% (yr) | LR (%) | Distant mtx (%) | OS % (yr) | F-u mo (median) |

| Park et al[8] | 133 | RME | 81.9 (5) | 3 (2.3) | 16 (12) | 92.8 (5) | 58 (4-80) |

| 84 | LME | 78.7 (5) | 1 (1.2) | 14 (16.6) | 93.5 (5) | 58 (4-80) | |

| Levic et al[9] | 56 | RME | 0 (0) | 8 (14.3) | 12 (1-31) | ||

| 36 | LME | 0 (0) | 2 (5.6) | 10 (1-33) | |||

| Yoo et al[10] | 431 | RME | 76.7 (3) | 6 (12.8) | 95.2 (3) | 33.9 (4.4-61.3) | |

| 26 | LME | 75 (3) | 2 (8.3) | 88.5 (3) | 36.5 (3.7-69.9) | ||

| Ghezzi et al[16] | 65 | RME | 73.2 (5) | 2 (3.2) | 19 (29.6) | 85 (5) | 60 |

| 109 | OME | 69.5 (5) | 17.5 (16.1) | 26 (24.2) | 76.1 (5) | 60 | |

| Saklani et al[19] | 74 | RME | 77.7 (3) | 2 (2.7) | 90 (3) | 30.1 (11-61)2 | |

| 64 | LME | 78.8 (3) | 4 (6.3) | 92.1 (3) | 30.1 (11-61)2 | ||

| Kim et al[25] | 62 | RME | 0 (0) | 3 (4.2) | 98 (1.5) | 17.4 | |

| 147 | LME | 1 (0.7) | 8 (5.4) | 98 (1.7) | 20.6 | ||

| Kwak et al[28] | 59 | RME | 1 (1.8) | 2 (3.6) | 17 (11-25) | ||

| 59 | LME | 1 (1.9) | 2 (3.7) | 13 (9-22) | |||

| Patriti et al[31] | 29 | RME | 100 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 96.6 (2.4) | 29.22 |

| 37 | LME | 83.7 (3) | 2 (5.4) | 4 (6) | 97.2 (1.5) | 18.72 | |

| Stănciulea et al[38] | 100 | RME | 2 (2) | 90 (3) | 24 (9-63) | ||

| Alimoglu et al[42] | 7 | RME | 100 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 100 (1) | 12 (6-21)2 |

| Pigazzi et al[47] | 143 | RME | 77.6 (3) | 2 (1.4) | 13 (9) | 97 (3) | 17.4 (0.1-52.5)2 |

1 patient excluded (palliative ISR);

Mean. DSF: Disease free survival rate; RME: Robotic mesorectal excision; LME: Laparoscopic mesorectal excision; OME: Open mesorectal excision.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

Robotic rectal surgery is constantly increasing over the years. Previous reviews have already demonstrated its safety and feasibility[51-53], although there are not published studies demonstrating its superiority over the laparoscopic approach mainly due to the lack of randomized control trials. This lack of evidence about the effectiveness of robotic rectal surgery is in contrast with the overall opinion of surgeons that report an easier surgical approach especially to narrow and difficult anatomic spaces such as the pelvis. Several authors[52-54] reported 3D high definition vision, wrist-like movement of instruments (endowristTM), stable camera holding, motion filter for tremor-free surgery and improved ergonomics as major improvements in rectal surgery but it seems that these technical benefits have not reflected better clinical outcomes yet. This review aimed to analyze robotic rectal surgery from the first report to nowadays in order to focus on the current state and assess any benefits of robotic rectal surgery and its evolution through the years.

A well-established finding of this review is the longer operative time of robotic surgery when compared to the laparoscopic one. This is most likely due not to longer dissection but to non-surgical technical time. In fact in the totally robotic approach the docking and undocking has to be performed twice and in the hybrid approach there is the need to switch from laparoscopy to robot. A totally robotic technique without undocking is feasible, but this approach is technically much more difficult and as a consequence, a longer operative time is needed[10,12,14,16,17,22-24,27,28,37,38,40-42,48]. Traditionally, longer operative time is related with increased morbidity, most likely related to the difficulty of the operation[53]. However prolonged times in robotic surgery are not associated with an increased complication rate as demonstrated by this review and previously published review and meta-analysis[55].

In our review 2[21,23], out of 16 comparative studies reported a significantly lower estimated blood loss after robotic rectal surgery confirming that there is still no evidence that robotic rectal surgery for cancer may be associated with a lower intraoperative blood loss.

As regards convertion rates to open surgery, 3[8,22,31] out of 22 comparative studies reported significant lower complication rates in robotic patients. Many authors associated these results to better visualization, 3D view, endowristTM technology and stable camera holding resulting in an easier dissection in narrow anatomical fields such as the pelvis[56]. Even the results reported by Ielpo et al[14] suggest that the robotic approach has lower conversion rates when the tumor location requests a low anterior resection and as a consequence, when the operations is technically more challenging. Since converted cases are associated to greater morbidity and tumor recurrence[57], robotic surgery could provide better oncologic long term results as well as a decreased perioperative morbidity.

The difference in protective ileostomy creation observed in this review can be related to several factors: The surgeon’s habit, the tumor location, the surgeon’s learning curve. Moreover, a trend toward an increasing stoma creation after robotic surgery could have been verified because of the initial worries about the new technique. On the bases of our findings the robotic approach seems associated with a higher rate of protective stoma creation.

One of the main benefits of minimally invasive surgery is the early recover. In this review we were unable to draw definitive results about any benefit of the robotic technique over conventional laparoscopy. Length of hospital stay, day of 1st flatus, 1st solid diet and 1st liquid diet were substantially similar in both the robotic and laparoscopic series even if some authors reported some advantages for either the robotic or the laparoscopic technique[8,9,15,22-24,30,32].

Anastomotic leak is the most severe surgical complication in rectal surgery. Well known risk factors for anastomotic leak are represented by cancers located less than 6 cm from anal verge, neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy, obesity and intraoperative blood transfusions[58-63]. In this review the overall anastomotic leak rates in the robotic and laparoscopic series were similar (7.3% vs 7.6%) with no comparative study reporting any significant difference between the 2 types of procedure. All together these results demonstrate that robotic surgery does not reduce the anastomotic leak rate. Nevertheless results of comparative studies are contradictory since 9[11,15,19,20-22,23,25,30] of these reported less anastomotic leaks in the robotic group and 9[8-10,14,17,24,28,29,31] in the laparoscopic one, but none of these results was significant. Looking at intraoperative complications, only Levic et al[9] reported a significant, higher rate in the robotic patients (4.48% vs 0%). However it must be considered that in this study there were more obese patients in the robotic group and all robotic and laparoscopic operations were performed in 2 different hospitals.

The number of harvested and examined lymph nodes is pivotal in the postoperative tumor staging whose accuracy increases with the number of nodes retrieved within the surgical specimen. The robotic platform with its 3D high definition vision and wrist-like movement of instruments should improve the lymph nodes retrieving. Nevertheless, the difference between the mean harvested lymph nodes in the robotic and laparoscopic series was not substantial in our review (15.1 vs 15.7 respectively) and only 2 authors[9,10] reported a significant higher number of retrieved lymph nodes in the robotic group.

The length of tumor involvement of both the distal and circumferential resection margins is considered an important parameter in evaluating the treatment of rectal cancer. Findings from the present review seems to determinate the lack of any advantages of robotic surgery over the laparoscopic approach. This issue might be explained by the likely surgeon’s trend to prefer robotic approach in more advanced and distal tumors because of the theoretical superiority of this technique in pelvic dissection. In this review indeed 7 authors[10,11,15,20,22,25,31] reported a significant lower distance of the tumor from anal verge when the robotic approach was compared with the laparoscopic one. Two comparative studies[13,22] reported even a significant wider CRM in their robotic series when compared to the laparoscopic ones. However a possible bias in the evaluation of this parameter is the non-uniform recording of data: some authors report median values, others the mean values making data not comparable. Even definition of circumferential resection margin is still not clear as it is currently considered as positive as positive if < 1 mm[8,11,14,19,24,25,30,35,64] by some authors and < 2 mm[10,12,15-17,20,22,23,26-29,36,37,39,40,42,44-50] by others.

Thanks to its technical characteristics the robot platform should help in performing total and complete mesorectal excision that is an important target in rectal surgery since it potentially reflects the radicality of the operation. Unfortunately even if this is a major parameter in evaluating the radicality of the intervention, only 11 out of 43 studies in this review have addressed this important parameter. On the basis of our results any superiority of robotic mesorectal excision over the laparoscopic one cannot be demonstrated.

Robotic surgery may help in the identification and preservation of autonomic nerves due to high definition 3D image. Common sites of potential nerve damage are the superior hypogastric plexus, leading to ejaculation dysfunction in males and impaired lubrification in females, and the pelvic splanchnic nerve/pelvic plexus leading to erectile dysfunction in men. According to results of the CLASSIC trial[59] the risk of an autonomic injury with sexual dysfunction in males is significantly higher in laparoscopic surgery when compared to the open approach. The perceived advantages of robotic surgery may translate to decreased incidence of urinary dysfunction and erectile dysfunction in males. Although some preliminary results suggested that robotic assisted rectal surgery is superior to conventional laparoscopic surgery in preventing sexual or urinary dysfunction[63,64], we cannot provide definitive results since only few studies addressed this issue with high heterogeneity in the scores systems used for the analysis. Furthermore not all the patients in the studies agreed in answering questionnaires and this could lead to a possible type II error. Some authors[26,18] reported an earlier recovery of erectile, sexual desire and urinary function when the robotic group was compared with the laparoscopic one but they did not report any difference in long-term follow-up.

In conclusion, results from the present review show that robotic surgery is as feasible and safe as conventional laparoscopy in the treatment of rectal cancer, with the only drawback of longer operative time. The magnified view, the improved ergonomics and dexterity might improve the diffusion of minimally invasive approach in the treatment of rectal cancer. Potential clinical benefits of the robotic technique must be demonstrated, if any, only by RCTs.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Authors declare no conflict of interest for this article. Authors declare no instance of Plagiarism or Academic Misconduct.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: March 15, 2016

First decision: May 19, 2016

Article in press: August 29, 2016

P- Reviewer: Agresta F, Aly EH, Brisinda G, Ouaissi M, Stanojevic GZ S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith AM, Heath RM, Brown JM. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1718–1726. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66545-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lacy AM, García-Valdecasas JC, Delgado S, Castells A, Taurá P, Piqué JM, Visa J. Laparoscopy-assisted colectomy versus open colectomy for treatment of non-metastatic colon cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2224–2229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09290-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veldkamp R, Kuhry E, Hop WC, Jeekel J, Kazemier G, Bonjer HJ, Haglind E, Påhlman L, Cuesta MA, Msika S, et al. Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:477–484. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuhry E, Schwenk WF, Gaupset R, Romild U, Bonjer HJ. Long-term results of laparoscopic colorectal cancer resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD003432. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003432.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKay GD, Morgan MJ, Wong SK, Gatenby AH, Fulham SB, Ahmed KW, Toh JW, Hanna M, Hitos K. Improved short-term outcomes of laparoscopic versus open resection for colon and rectal cancer in an area health service: a multicenter study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:42–50. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318239341f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham NS, Young JM, Solomon MJ. Meta-analysis of short-term outcomes after laparoscopic resection for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1111–1124. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cianchi F, Cortesini C, Trallori G, Messerini L, Novelli L, Comin CE, Qirici E, Bonanomi A, Macrì G, Badii B, et al. Adequacy of lymphadenectomy in laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery: a single-centre, retrospective study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:33–37. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31824332dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park EJ, Cho MS, Baek SJ, Hur H, Min BS, Baik SH, Lee KY, Kim NK. Long-term oncologic outcomes of robotic low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a comparative study with laparoscopic surgery. Ann Surg. 2015;261:129–137. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levic K, Donatsky AM, Bulut O, Rosenberg J. A Comparative Study of Single-Port Laparoscopic Surgery Versus Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Surgery for Rectal Cancer. Surg Innov. 2015;22:368–375. doi: 10.1177/1553350614556367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoo BE, Cho JS, Shin JW, Lee DW, Kwak JM, Kim J, Kim SH. Robotic versus laparoscopic intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer: comparison of the operative, oncological, and functional outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1219–1225. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh FH, Tan KK, Lieske B, Tsang ML, Tsang CB, Koh DC. Endowrist versus wrist: a case-controlled study comparing robotic versus hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24:452–456. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e318290158d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melich G, Hong YK, Kim J, Hur H, Baik SH, Kim NK, Sender Liberman A, Min BS. Simultaneous development of laparoscopy and robotics provides acceptable perioperative outcomes and shows robotics to have a faster learning curve and to be overall faster in rectal cancer surgery: analysis of novice MIS surgeon learning curves. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:558–568. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3698-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnajian M, Pettet D, Kazi E, Foppa C, Bergamaschi R. Quality of total mesorectal excision and depth of circumferential resection margin in rectal cancer: a matched comparison of the first 20 robotic cases. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:603–609. doi: 10.1111/codi.12634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ielpo B, Caruso R, Quijano Y, Duran H, Diaz E, Fabra I, Oliva C, Olivares S, Ferri V, Ceron R, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic rectal resection: is there any real difference? A comparative single center study. Int J Med Robot. 2014;10:300–305. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tam MS, Abbass M, Abbas MA. Robotic-laparoscopic rectal cancer excision versus traditional laparoscopy. JSLS. 2014;18 doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghezzi TL, Luca F, Valvo M, Corleta OC, Zuccaro M, Cenciarelli S, Biffi R. Robotic versus open total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: comparative study of short and long-term outcomes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:1072–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.02.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuo LJ, Lin YK, Chang CC, Tai CJ, Chiou JF, Chang YJ. Clinical outcomes of robot-assisted intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer: comparison with conventional laparoscopy and multifactorial analysis of the learning curve for robotic surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:555–562. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-1841-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park SY, Choi GS, Park JS, Kim HJ, Ryuk JP, Yun SH. Urinary and erectile function in men after total mesorectal excision by laparoscopic or robot-assisted methods for the treatment of rectal cancer: a case-matched comparison. World J Surg. 2014;38:1834–1842. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2419-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saklani AP, Lim DR, Hur H, Min BS, Baik SH, Lee KY, Kim NK. Robotic versus laparoscopic surgery for mid-low rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy: comparison of oncologic outcomes. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:1689–1698. doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1756-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez R, Anaya DA, Li LT, Orcutt ST, Balentine CJ, Awad SA, Berger DH, Albo DA, Artinyan A. Laparoscopic versus robotic rectal resection for rectal cancer in a veteran population. Am J Surg. 2013;206:509–517. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erguner I, Aytac E, Boler DE, Atalar B, Baca B, Karahasanoglu T, Hamzaoglu I, Uras C. What have we gained by performing robotic rectal resection? Evaluation of 64 consecutive patients who underwent laparoscopic or robotic low anterior resection for rectal adenocarcinoma. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:316–319. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31828e3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Annibale A, Pernazza G, Monsellato I, Pende V, Lucandri G, Mazzocchi P, Alfano G. Total mesorectal excision: a comparison of oncological and functional outcomes between robotic and laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1887–1895. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2731-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang J, Yoon KJ, Min BS, Hur H, Baik SH, Kim NK, Lee KY. The impact of robotic surgery for mid and low rectal cancer: a case-matched analysis of a 3-arm comparison--open, laparoscopic, and robotic surgery. Ann Surg. 2013;257:95–101. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182686bbd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park SY, Choi GS, Park JS, Kim HJ, Ryuk JP. Short-term clinical outcome of robot-assisted intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer: a retrospective comparison with conventional laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:48–55. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim YW, Lee HM, Kim NK, Min BS, Lee KY. The learning curve for robot-assisted total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:400–405. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182622c2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JY, Kim NK, Lee KY, Hur H, Min BS, Kim JH. A comparative study of voiding and sexual function after total mesorectal excision with autonomic nerve preservation for rectal cancer: laparoscopic versus robotic surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2485–2493. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertani E, Chiappa A, Biffi R, Bianchi PP, Radice D, Branchi V, Cenderelli E, Vetrano I, Cenciarelli S, Andreoni B. Assessing appropriateness for elective colorectal cancer surgery: clinical, oncological, and quality-of-life short-term outcomes employing different treatment approaches. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:1317–1327. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwak JM, Kim SH, Kim J, Son DN, Baek SJ, Cho JS. Robotic vs laparoscopic resection of rectal cancer: short-term outcomes of a case-control study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:151–156. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181fec4fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baek JH, Pastor C, Pigazzi A. Robotic and laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: a case-matched study. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:521–525. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park JS, Choi GS, Lim KH, Jang YS, Jun SH. S052: a comparison of robot-assisted, laparoscopic, and open surgery in the treatment of rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:240–248. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1166-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patriti A, Ceccarelli G, Bartoli A, Spaziani A, Biancafarina A, Casciola L. Short- and medium-term outcome of robot-assisted and traditional laparoscopic rectal resection. JSLS. 2009;13:176–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baik SH, Ko YT, Kang CM, Lee WJ, Kim NK, Sohn SK, Chi HS, Cho CH. Robotic tumor-specific mesorectal excision of rectal cancer: short-term outcome of a pilot randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1601–1608. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9752-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pigazzi A, Ellenhorn JD, Ballantyne GH, Paz IB. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1521–1525. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0855-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parisi A, Desiderio J, Trastulli S, Cirocchi R, Ricci F, Farinacci F, Mangia A, Boselli C, Noya G, Filippini A, et al. Robotic rectal resection for cancer: a prospective cohort study to analyze surgical, clinical and oncological outcomes. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1456–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baek SJ, Kim CH, Cho MS, Bae SU, Hur H, Min BS, Baik SH, Lee KY, Kim NK. Robotic surgery for rectal cancer can overcome difficulties associated with pelvic anatomy. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:1419–1424. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3818-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiomi A, Kinugasa Y, Yamaguchi T, Tomioka H, Kagawa H. Robot-assisted rectal cancer surgery: short-term outcomes for 113 consecutive patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1105–1111. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-1921-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim IK, Kang J, Park YA, Kim NK, Sohn SK, Lee KY. Is prior laparoscopy experience required for adaptation to robotic rectal surgery?: Feasibility of one-step transition from open to robotic surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:693–699. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-1858-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stănciulea O, Eftimie M, David L, Tomulescu V, Vasilescu C, Popescu I. Robotic surgery for rectal cancer: a single center experience of 100 consecutive cases. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2013;108:143–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zawadzki M, Velchuru VR, Albalawi SA, Park JJ, Marecik S, Prasad LM. Is hybrid robotic laparoscopic assistance the ideal approach for restorative rectal cancer dissection? Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1026–1032. doi: 10.1111/codi.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sng KK, Hara M, Shin JW, Yoo BE, Yang KS, Kim SH. The multiphasic learning curve for robot-assisted rectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3297–3307. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2909-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du XH, Shen D, Li R, Li SY, Ning N, Zhao YS, Zou ZY, Liu N. Robotic anterior resection of rectal cancer: technique and early outcome. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alimoglu O, Atak I, Kilic A, Caliskan M. Robot-assisted laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection for low rectal cancer. Int J Med Robot. 2012;8:371–374. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akmal Y, Baek JH, McKenzie S, Garcia-Aguilar J, Pigazzi A. Robot-assisted total mesorectal excision: is there a learning curve? Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2471–2476. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park IJ, You YN, Schlette E, Nguyen S, Skibber JM, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Chang GJ. Reverse-hybrid robotic mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:228–233. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823c0bd2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang J, Min BS, Park YA, Hur H, Baik SH, Kim NK, Sohn SK, Lee KY. Risk factor analysis of postoperative complications after robotic rectal cancer surgery. World J Surg. 2011;35:2555–2562. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.deSouza AL, Prasad LM, Marecik SJ, Blumetti J, Park JJ, Zimmern A, Abcarian H. Total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: the potential advantage of robotic assistance. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1611–1617. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181f22f1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pigazzi A, Luca F, Patriti A, Valvo M, Ceccarelli G, Casciola L, Biffi R, Garcia-Aguilar J, Baek JH. Multicentric study on robotic tumor-specific mesorectal excision for the treatment of rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1614–1620. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0909-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi DJ, Kim SH, Lee PJ, Kim J, Woo SU. Single-stage totally robotic dissection for rectal cancer surgery: technique and short-term outcome in 50 consecutive patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1824–1830. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b13536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]