Abstract

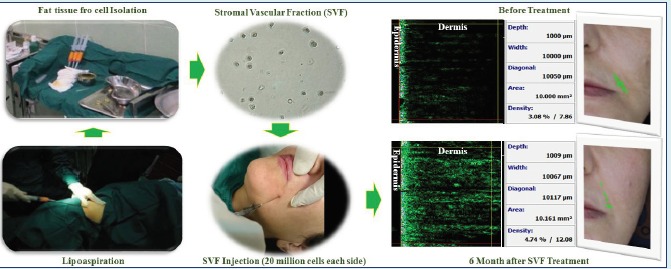

Introduction: The rejuvenation characteristics of fat tissue grafting has been established for many years. Recently it has been shown that stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of fat tissue contributes to its rejuvenation properties. As the SVF is a minimal processed cell population (based on FDA guidance), therefore it is a suitable cell therapy for skin rejuvenation. This clinical trial was aimed to evaluate the ultrastructural improvement of aging skin in the facial nasolabial region after transplantation of autologous SVF.

Methods: Our study was conducted in 16 patients aged between 38 and 56 years old that were interested in face lifting at first. All of the cases underwent the lipoaspiration procedure from the abdomen for sampling of fat tissue. Quickly, the SVF was harvested from 100 mL of harvested fat tissue and then transplanted at dose of 2.0×107 nucleated cells in each nasolabial fold. The changes in the skin were evaluated using Visioface scanner, skin-scanner DUB, Visioline, and Cutometer with multi probe adopter.

Results: By administration of autologous SVF, the elasticity and density of skin were improved significantly. There were no changes in the epidermis density in scanner results, but we noticed a significant increase in the dermis density and also its thickness with enrichment in the vascular bed of the hypodermis. The score of Visioface scanner showed slight changes in wrinkle scores. The endothelial cells and mesenchymal progenitors from the SVF were found to chang the architecture of the skin slightly, but there was not obvious phenotypic changes in the nasolabial grooves.

Conclusion: The current clinical trial showed the modification of dermis region and its microvascular bed, but no changes in the density of the epidermis. Our data represent the rejuvenation process of facial skin by improving the dermal architecture.

Keywords: Cell therapy, Dermatology, Facial skin, Regenerative medicine, Rejuvenation, SVF

Introduction

Human fat tissue is composed of mature adipocytes constituting about 90% of the tissue volume, and a stromal vascular fraction (SVF) including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, pre-adipocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, lymphocytes, resident monocytes/macrophages, and adipose derived stem cells (ADSCs). The multipotent mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) line within the SVF is known as ADSC.1 It is notable that fat tissue harbors approximately 50 fold greater number of MSCs in comparison with bone marrow.2 After more advances with Illouz’s liposuction technique in the 1980s,3 the large volumes of adipose tissue that were routinely discarded, it is now accessible for the plastic surgery and furthermore it could be used for the cell therapy and regenerative medicine purposes especially for skin rejuvenation.

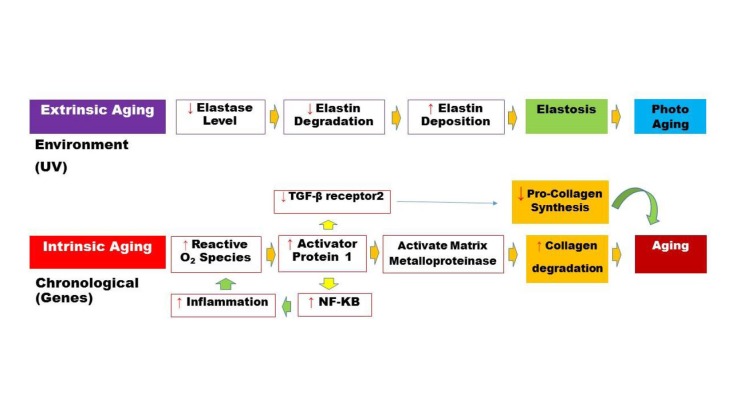

There are two distinct skin aging processes: photo-aging (extrinsic) and chronological (intrinsic) aging. Fig. 1 summarizes the molecular cues of skin aging. The characteristics of skin aging includes wrinkles, dryness, laxity, thinning, irregular pigmentation, and loss of elasticity4 that belong to the environment and genetic factors. Histology studies revealed that UV exposure turns skin into a flattened dermo-epidermal interface, with loss of dermal papillae. In this manner, the dermal thickness and vascularity is lowered. This phenomenon leads to the decreased fibroblast activity, and accidentally arranged elastin fibers.5 Various methods have been used to prevent or treat the symptoms of aging like many creams, lotions and such cosmeceuticals; however, up until now, the results are unsatisfactory. In recent years, cell therapies for rejuvenation have gained much importance. Fibrous collagen is very important for the strength and elasticity of skin, and the amount of this protein is generally decreased with aging. Many studies in the aesthetic field for skin rejuvenation6 confirm that ADSCs increase the dermal collagen synthesis and even vascularity via production of many cytokines and growth factors.7-9 It has been shown that ADSCs secrete growth factors that have an effect on fibroblast and keratinocyte proliferation.10-12 Some researchers reported that the ADSCs could be differentiated into epithelial lineage and make their effect on the aged or damaged skin.13,14

Fig. 1 .

A simplified schematic representation for extrinsic and intrinsic molecular pathways of skin aging.

On the ground that deriving SVF from the fat tissue is only a minimal manipulation process by closed or semi closed systems performed either enzymatically or non-enzymatically,15,16 it is believed to pose minimum risk of bacterial and/or fungal contamination. The process of SVF extraction can be done within approximately 30 min (vary between 15 to 90 min), 7,18 which makes this process a very safe and fast procedure for cell therapy. In this study, we evaluated the efficiency and reliability of SVF treatment on the skin rejuvenation and its architecture in a clinical trial.

Materials and methods

Patients

Between January 2014 and January 2015, we chose 16 candidates for SVF isolation and transplantation. The candidates (1 male and 15 females) were aged between 38 to 56 years. All the candidates shared a common problem: nasolabial grooves and marionette lines.

Isolation and characterization of SVF

The fat aspiration was performed through undergoing optimized abdominal lipoaspiration using a 3 mm cannula under topical anesthesia. The aspiration site was infiltrated with saline solution containing epinephrine (0.001%). One hundred mL of fat tissue was suctioned using a special lipoaspiration device with a filter.

The SVF was isolated from 100 mL aspirated fat tissue that was divided into two sterile falcon tubes (50 mL each) as described previously.6 Briefly, the tissue was washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), (Miltenyi Biotech, Cologne, Germany) in order to remove the majority of erythrocytes and leukocytes and then was digested with collagenase type I (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, USA) at 37°C for 20 min under constant shaking. Collagenase solution was made up just prior to use. Collagenase powder was added to the Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) in a final concentration of 0.2%. Digestion was stopped by washing with PBS for 3 times. Floating and lysed adipocytes were discarded and cells from the SVF were pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 500 ×g. The pellet was resuspended in the HBSS and incubated in an erythrocyte lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich Corp, St. Louis, USA) for 10 min at 37°C. This cell suspension was centrifuged at 500 ×g for 5 min, and cells were counted using trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich Corp, St. Louis, USA). A part of this suspension was subjected to flow cytometry (Partec, Görlitz, Germany) for analyzing cell surface markers.

Transplantation of SVF

The obtained SVF was injected into the subcutaneous layer of the skin at the dose of 2×107 total nucleated cells for each side. For injection into the nasolabial grooves, a 1 mL syringe with an 18 gauge blunt needle was used to obtain the diffuse distribution of the SVF. Visioface (D1000 ck, Cologne, Germany) and Visioline (LL 650 CK Germany) photographs of each patient were taken before and at each visit after treatment with a high-resolution digital camera. The skin scanner, DUB-TPA (EOTECH, Marcoussis, France) and multi probe adapter Cutometer (CK Elecronic, Cologne, Germany) were also used to calculate the skin layers’ thickness and elasticity before and after SVF transplantation, respectively. A 2 mm diameter probe of Cutometer was applied in this study that used a constant suction of about 350 mBar for 18 s followed by a 2 s relaxation time. After the suction phase, the vacuum in the probe was automatically switched to 0 mBar. The results were then observed on the clients. When the transplantation procedure was accomplished, clients were followed on day 15, 30, 60, and 180.

Side effects

All the patients, who were transplanted with autologous SVF, were surveyed for edema, erythema, ecchymosis, and tenderness during 4 weeks after injection.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of our data for different factors was assessed running Mann-Whitney test by using SPSS software, and significant differences were determined on p ≤ 0.05.

Results

SVF yield from fat tissue digestion

The nucleated cell yield was 7.0 ±1.5×105 cells/mL of aspirated fat tissue by the mentioned method. The viability of nucleated SVF cells isolated from all candidates was measured by trypan blue staining. The viability of cells was about 83 ± 8.4%.

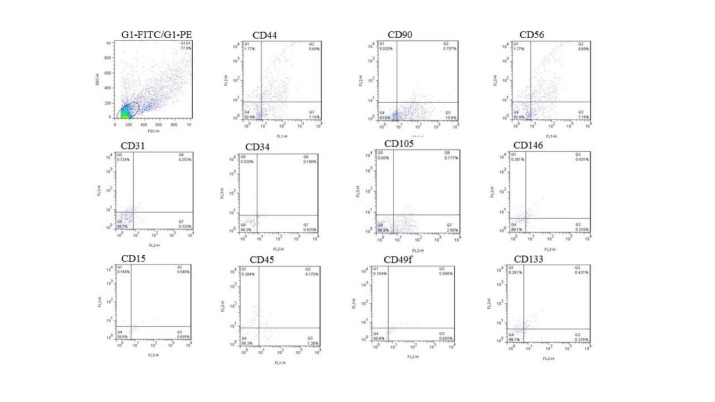

SVF flow cytometric analysis

The characteristics of SVF were analyzed by flow cytometry. The analysis of surface markers of the freshly isolated SVF showed the expression of endothelial markers CD31, CD34, and CD146. Moreover, there were expressions of mesenchymal markers including CD44, CD73, CD90, and CD105. Of these, CD44 is a receptor for hyaluronic acid that contributes in the dermal thickness. We used the intrinsic markers to evaluate the molecular cues of skin rejuvenation. Hematopoietic stem cell markers like CD49f and CD133 were found in our isolated SVF cell population. There was additionally hematopoietic markers (CD14, CD15, and CD45) and an abundance of natural killer cell marker CD56 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 .

The representative data shows flow cytometric analysis of freshly isolated SVF. Expression of endothelial markers CD31, CD34, CD146; mesenchymal markers CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105; hematopoietic markers CD49f, CD133, CD14, CD15, CD45 and natural killer cell marker CD56.

Patients’ outcome

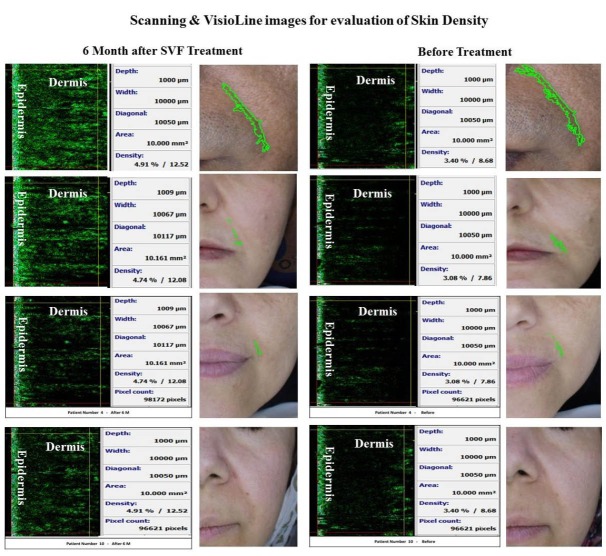

The patients’ data who received autologous SVF transplantation are summarized in Table 1. Based upon the Visioface data, there were not phenotypic changes on the nasolabial groove (Fig. 3).

Table 1 . Summary of patient’s data before and after SVF transplantation in this clinical trial .

| Variables | N | Means ± SD | p value | |

| Before | After 6 month | |||

| Visioface | 16 | 0.298±0.181 | 0.289±0.167 | 0.128 |

| Mexameter* melanin | 16 | 204.156±46.04 | 213±46.12 | 0.187 |

| Mexameter erythema | 16 | 416.95±73.85 | 422.97±64.33 | 0.669 |

| Tewa meter** | 16 | 29.087±10.67 | 21.51±10.44 | p<0.001 |

| Colorimeter | 16 | 31.94±8.70 | 30.25±8.47 | 0.085 |

| R2*** | 16 | 0.678±0.129 | 0.859±0.121 | p<0.001 |

| R5**** | 16 | 0.680±0.151 | 0.849±0.170 | P<0.001 |

| R7***** | 16 | 0.485±0.147 | 0.657±0.204 | p<0.001 |

| Skin density | 16 | 3.01±0.995 | 4.27±1.55 | p<0.001 |

| Skin thickness | 16 | 986.187±228.44 | 1200.75±208.92 | p<0.001 |

| Epidermis density | 16 | 6.90±7.065 | 7.68±7.96 | 0.078 |

| Epidermis thickness | 16 | 188.69±186.151 | 228.125±184.75 | 0.001 |

| Dermis density | 16 | 2.097±0.83 | 4.88±1.536 | p<0.001 |

| Dermis thickness | 16 | 799.31±140.40 | 976.50±169.90 | 0.002 |

* Levels of Pigmentation; ** Percent of water evaporation from skin surface; *** Ability of returning to the original position; **** Elastic part of the suction phase; ***** Portion of the elastic recovery compared to the complete curve.

Fig. 3 .

The face skin scan before and after stromal vascular fraction transplantation. Data show the significant increase in the dermis density and Visioface wrinkle scoring shows the 4.8% and 3.3% of the photograph area including the nasolabial groove before and after stromal vascular fraction transplantation, respectively.

Also the Mexameter system showed no change in the pigmentation and melanin production after 6 months of SVF transplantation. This evidence was confirmed by colorimetric assay (Table 1).

The percent of water evaporation from skin was found to be increased by aging. In this experiment, the water evaporation from skin surface was significantly decreased after SVF treatment. For the elasticity test some factors were considered by our team.

After the SVF administration, three main features (i.e., the ability of returning to the original position, elastic part of the suction phase, and a portion of the elastic recovery) were compared to the complete curve. It was found that the skin density was increased significantly in all cases (Table 1).

Unlike the epidermis thickness, we observed a significant increase in the dermis thickness and density (Fig. 3) that affected the whole skin density too.

The preliminary data showed that clinical outcomes were generally satisfactory without leaving any serious side effects such as erythema, edema, ecchymosis, tenderness, and cyst formation, suggesting that SVF cells are safe for clinical use.

Discussion

Our findings in this clinical trial indicate that transplantation of autologous SVF is very promising strategy to improve the architecture of depressed areas in the facial skin, despite the insignificant phenotypic changes of nasolabial grooves (Fig. 3). Maybe, it was due to the low number of transplanted cells into the nasolabial grooves. The different cell types in SVF (Fig. 2) alter the tissue microenvironment via the secretion of soluble factors that contribute considerably to rejuvenation process. To identify the SVF engraftment, Zuk et al. performed PCR experiments.1 It was found that the injected cells disappeared before one week. Therefore the probable mechanism was a paracrine effect of SVF cytokines that modulated extracellular matrix remodeling, angiogenesis, fibroblast mitosis and antioxidant effect that inhibited the aging process (Fig. 1).

On the other hand, the SVF transplantation must have another function because it is already applied clinically for other purposes such as cell enriched lipotransfer (CAL), wound healing, scar remodeling, and tissue engineering. These cases could not be solely related to the paracrine effect of SVF. For instance, it is known that CD44 is hyaluronic acid receptor that is decreased with aging and causes less density of dermis layer. A population of SVF cells expresses CD44 (Fig. 2) that could act as hyaluronic acid receptor. The increase of dermis density is shown in our experiment (Table 1, Fig. 3).

To induce skin rejuvenation, a wide variety of experiments have been conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of SVF. In 2009, Shamban surveyed the role of SVF in its derived secretory factors in the treatment of photo-damage skin.19 The results showed the efficacy of these factors in improving the extrinsic aged skin. These studies were continued and in 2013 Chang et al. performed a quantitative volumetric analysis of progressive hemifacial atrophy using SVF. They reported that the SVF-supplemented fat transplantation was safe and efficient for treating this kind of atrophy and SVF could enhance the fat tissue graft survival in the facial region.20 To conform the paracrine effect of SVF, an in vitro study in 2014 by Kim et al. revealed that adipose mesenchymal cells-conditioned media down-regulated melanogenic enzymes and therefore inhibited melanocyte proliferation and melanin synthesis,21 thereby decreasing the pigmentation of skin that contributes to the aging process. However, our direct transplantation of SVF into the nasolabial groove did not show any difference in skin pigmentation (Table 1).

A study in 2014 by Klar et al. showed that SVF derived endothelial cell population contained a highly efficient capillary plexus to develop vascular networks.22 The increase in dermis thickness after SVF administration in our trial confirms these findings. Additionally, Atalay et al. showed that SVF improves the burn wound healing by (a) acceleration of cell proliferation and increase in vascularization, (b) reduction of inflammation, and (c) elevation of fibroblasts activity.23 Although the rejuvenation process is different from burn wounds, our data showed that there was not inflammation after SVF transplantation in the facial skin. Similarly, Cheng et al. confirmed that autologous SVF transplantation enhances angiogenesis after skin grafting and improves the elasticity of skin grafts.24 Our data confirmed these findings in human and we showed the significant changes in the skin elasticity after SVF transplantation (Table 1).

In 2016, Rigotti et al. showed that SVF or ADSCs had a significant effect on skin rejuvenation 3 months after treatment.25 Our study by SVF after 1 to 6 months follow-up confirmed this idea. In a recent study in 2016, Klar et al. showed that the endothelial part of SVF exhibited the ability to form microvascular structures in vitro and support the accelerated blood perfusion in skin substitutes in vivo.9 This study confirmed their previous experiments and also the study conducted by Atalay et al. in 2014.22,23 The skin scanner results of our study (Fig. 3) was in accordance with these findings as we saw that more thickness of dermis layer needed more blood perfusion at the bedside of the hypodermis.

In addition to the clinical relevance and efficacy to use SVF, there is a major concern about safety and GMP preparation of all cell therapy products. SVF is “minimally manipulated”, and it is an advantage in cell therapy, which many believed would allow them to circumvent a large amount of regulatory oversight by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other regulatory agencies around the world like European Medical Agency (EMA).

Some previous studies showed that SVF cell yield from 1 gram of fat tissue is between 2.0× 104 to 2.0×106 nucleated cells by different methods of tissue processing.26-28 Therefore, the efficiency of the SVF isolation protocol is of importance. As there are automated closed systems that produce high yield of SVF without any risk of contaminations, it is imaginable to have SVF as a routine part of skin rejuvenation treatment in clinics. Autologous SVF transplantation for skin rejuvenation achieves higher rates of success, costs less, and has an easy-to-access reservoir.

Conclusion

SVF of adipose tissue represents an attractive cell source, in large part due to the ease of isolation and abundance of endothelial as well as mesenchymal stem cells. Its transplantation under the dermis layer exhibits the ability to thicken the dermal bed and form microvascular structure of aged skin to induce rejuvenation and modify the dermal-epidermal architecture.

Ethical approval

Written informed consents were obtained from all the patients, according to the protocol approved by Tehran University of Medical Sciences review board and Iranian Ministry of Health (Iranian Registry of Clinical Trial ID No. IRCT2014100719432N1). The candidates were also made aware about the study purpose, procedure, potential risks, and benefits. They were informed at the beginning of the procedure that they may leave at any time during the study.

Competing interests

Tere is none to be declared.

Acknowledgments

This project is part of PhD thesis belonging to the Skin and Stem cell Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The work was supported financially by the Iranian Council for the Development of Stem Cell Sciences and Technologies and in part by Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Research Highlights

What is current knowledge?

√ There is a prevailing wisdom about dramatic changes of skin wrinkles after SVF administration.

√ There were no data about changes in the skin pigmentation after cell therapy.

√ It has been known that the percent of water evaporation from the skin increases by aging.

What is new here?

√ According to our data obtained from Visioface, there were not phenotypic changes on the nasolabial groove.

√ After our SVF transplantation experiment, the Mexameter system showed no change in the pigmentation and melanin production even after 6 months.

√ We showed that the water evaporation from skin surface was significantly decreased after SVF treatment.

√ Unlike the epidermis thickness, we observed a significant increase in the dermis thickness and density; however, it could affect the whole skin density too.

References

- 1.Zuk P, Zhu M, Ashjian P. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotential stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4279–95. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strem BM, Hicok KC, Zhu M, Wulur I, Alfonso Z, Schreiber RE. et al. Multipotential differentiation of adipose tissue-derived stem cells. Keio J Med. 2005;54:132–41. doi: 10.2302/kjm.54.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman S. Facial recontouring with liposculpture. Clin Plast Surg. 1997;24:347–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konno M, Hamabe A, Hasegawa S, Ogawa H, Fukusumi T, Nishikawa S. et al. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells and regenerative medicine. Dev Growth Differ. 2013;55:309–18. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rokhsar CK, Lee S, Fitzpatrick RE. Review of photorejuvenation: devices, cosmeceuticals, or both? Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1166–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charles-de-Sá L, Gontijo-de-Amorim NF, Maeda Takiya C, Borojevic R, Benati D, Bernardi P. et al. Antiaging treatment of the facial skin by fat graft and adipose-derived stem cells. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:999–1009. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim WS, Park BS, Sung JH. Protective role of adiposederived stem cells and their soluble factors in photoaging. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011;301:329–36. doi: 10.1007/s00403-009-0951-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubina K, Kalinina N, Efimenko A. Adipose stromal cells stimulate angiogenesis via promoting progenitorvcell differentiation, secretion of angiogenic factors, and enhancing vessel maturation. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:2039–50. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klar A, Güven S, Zimoch J, Zapiórkowska NA, Biedermann T, Böttcher-Haberzeth S. et al. Characterization of vasculogenic potential of human adipose-derived endothelial cells in a three-dimensional vascularized skin substitute. Pediatr Surg Int. 2016;32:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s00383-015-3808-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SH, Jin SY, Song JS, Seo KK, Cho KH. Paracrine effects of adiposederived stem cells on keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:136–43. doi: 10.5021/ad.2012.24.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moon KM, Park YH, Lee JS, Chae YB, Kim MM, Kim DS. et al. The effect of secretory factors of adipose-derived stem cells on human keratinocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:1239–57. doi: 10.3390/ijms13011239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song SY, Jung JE, Jeon YR, Tark KC, Lew DH. Determination of adipose-derived stem cell application on photo-aged fibroblasts, based on paracrine function. Cytotherapy. 2011;13:378–84. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.530650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brzoska M, Geiger H, Gauer S, Baer P. Epithelial differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived adult stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;330:142–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sasaki M, Abe R, Fujita Y, Ando S, Inokuma D, Shimizu H. Mesenchymal stem cells are recruited into wounded skin and contribute to wound repair by transdifferentiation into multiple skin cell type. J Immunol Methods. 2008;180:2581–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doi K, Tanaka S, Iida H. Stromal vascular fraction isolated from lipo-aspirates using an automated processing system: bench and bed analysis. J Tiss Eng Regen Med. 2013;7:864–70. doi: 10.1002/term.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aronowitz JA, Ellenhorn JD. Adipose stromal vascular fraction isolation: a head-to-head comparison of four commercial cell separation systems. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:932e–9e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a80652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baer PC, Geiger H. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal/stem cells: tissue localization, characterization, and heterogeneity. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:812693. doi: 10.1155/2012/812693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bourin P, Bunnell BA, Casteilla L, Dominici M, Katz AJ, March KL. et al. Stromal cells from the adipose tissue-derived stromal vascular fraction and culture expanded adipose tissue-derived stromal/stem cells: a joint statement of the International Federation for Adipose Therapeutics and Science (IFATS) and the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) Cytotherapy. 2013;15:641–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shamban AT. Current and new treatments of photodamaged skin. Facial Plast Surg. 2009;25:337–46. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang Q, Li J, Dong Z, Liu L, Lu F. Quantitative volumetric analysis of progressive hemifacial atrophy corrected using stromal vascular fraction-supplemented autologous fat grafts. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1465–73. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim DW, Jeon BJ, Hwang NH, Kim MS, Park SH, Dhong ES. et al. Adipose-derived stem cells inhibit epidermal melanocytes through an interleukin-6-mediated mechanism. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:470–80. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klar AS, Güven S, Biedermann T, Luginbühl J, Böttcher-Haberzeth S, Meuli-Simmen C. et al. Tissue-engineered dermo-epidermal skin grafts prevascularized with adipose-derived cells. Biomaterials. 2014;35:5065–78. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atalay S, Coruh A, Deniz K. Stromal vascular fraction improves deep partial thickness burn wound healing. Burns. 2014;40:1375–83. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng C, Sheng L, Li H, Mao X, Zhu M, Gao B. et al. Cell-Assisted Skin Grafting: Improving Texture and Elasticity of Skin Grafts through Autologous Cell Transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:58e–66e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rigotti G, Charles-de-Sá L, Gontijo-de-Amorim NF, Takiya CM, Amable PR, Borojevic R. et al. Expanded Stem Cells, Stromal-Vascular Fraction, and Platelet-Rich Plasma Enriched Fat: Comparing Results of Different Facial Rejuvenation Approaches in a Clinical Trial. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36:261–70. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjv231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin K, Matsubara Y, Masuda Y, Togashi K, Ohno T, Tamura T. et al. Characterization of adipose tissue-derived cells isolated with the Celution system. Cytotherapy. 2008;10:417–26. doi: 10.1080/14653240801982979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boquest AC, Shahdadfar A, Fronsdal K, Sigurjonsson O, Tunheim SH, Collas P. et al. Isolation and transcription profiling of purified uncultured human stromal stem cells: alteration of gene expression after in vitro cell culture. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1131–41. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell JB, McIntosh K, Zvonic S. Immunophenotype of human adiposederived cells: temporal changes in stromal associated and stem cell-associated markers. Stem Cells Dev. 2006;24:376–85. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]