Abstract

The GacS/GacA two-component system (also called GrrS/GrrA) is a global regulatory system which is highly conserved among gamma-proteobacteria. This system positively regulates non-coding small regulatory RNA csrB, which in turn binds to the RNA-binding protein CsrA. However, how GacS/GacA-Csr system regulates virulence traits in E. amylovora remains unknown. Results from mutant characterization showed that the csrB mutant was hypermotile, produced higher amount of exopolysaccharide amylovoran, and had increased expression of type III secretion (T3SS) genes in vitro. In contrast, the csrA mutant exhibited complete opposite phenotypes, including non-motile, reduced amylovoran production and expression of T3SS genes. Furthermore, the csrA mutant did not induce hypersensitive response on tobacco or cause disease on immature pear fruits, indicating that CsrA is a positive regulator of virulence factors. These findings demonstrated that CsrA plays a critical role in E. amylovora virulence and suggested that negative regulation of virulence by GacS/GacA acts through csrB sRNA, which binds to CsrA and neutralizes its positive effect on T3SS gene expression, flagellar formation and amylovoran production. Future research will be focused on determining the molecular mechanism underlying the positive regulation of virulence traits by CsrA.

Erwinia amylovora is the causal agent of fire blight, a devastating disease of apples and pears, which results in severe economic losses to growers around the world1,2,3. In order to colonize its host and cause disease, E. amylovora requires the deployment of effector proteins into the host cells by a type III secretion system (T3SS) and the production of the exopolysaccharide (EPS) amylovoran4,5,6. The T3SS in E. amylovora is encoded by the hypersensitive response and pathogenicity (hrp) island and is regulated by a HrpL-RpoN sigma factor cascade, which is further activated by the bacterial alarmone (p)ppGpp7,8,9,10,11,12. The T3SS is also controlled by several two-component signal transduction systems (TCST), including GacS/GacA (GrrS/GrrA) and EnvZ/OmpR systems13,14. On the other hand, amylovoran plays an important role in virulence, biofilm formation, and survival of the bacterium; and its biosynthesis is regulated by the RcsBCD, GrrS/GrrA and EnvZ/OmpR TCST systems5,13,14,15.

While widely-distributed among eubacteria, the bacterial CsrA-csrB/RsmA-rsmB system (for carbon storage regulator/repressor of secondary metabolism, respectively) is a well-characterized and vital small RNA (sRNA)-dependent regulatory system16, which regulates a plethora of important phenotypes, including carbon storage, secondary metabolism, motility, biofilm formation, peptide uptake, cyclic di-GMP and (p)ppGpp synthesis, quorum sensing, and expression of virulence genes17,18,19. In many pathogenic bacteria, GacA activates the transcription of one to five small non-coding regulatory RNAs, including csrB and csrC in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica, rsmY and rsmZ in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, rsmB, rsmY and rsmZ in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000, and rsmB in Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum20,21,22,23,24,25,26. These sRNAs contain many GGA sequences, which are required for sequestering the RNA binding protein CsrA (carbon storage regulator) or its homologs RsmA and RsmE (repressor of secondary metabolites), thus antagonizing its function.

The CsrA protein was first described as a repressor of glycogen metabolism, gluconeogenesis and cell size in E. coli27. Later studies showed that a csrA deletion mutation is not viable in rich medium due to excessive glycogen accumulation28. In addition to carbon metabolism, RsmA and RsmE proteins suppress the biocontrol activity of Pseudomonas protegens CHA0 by negatively regulating the synthesis of antifungal secondary metabolites29. As a major post-transcriptional regulator, CsrA could act both negatively and positively. Transcriptomic, RNA co-purification, and crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP)-seq data revealed a large posttranscriptional regulon in Salmonella, E. coli and Xanthomonas spp30,31,32,33. Genetic and biochemical studies showed that CsrA-mediated repression primarily affects translation or stability of target mRNAs by blocking ribosome binding through binding to the 5′ untranslated (UTR) regions and recognizing GGA motifs in the apical loops of the RNA secondary structures, one of which overlaps with the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) site16,34,35. Direct binding of CsrA can also stabilize the target mRNAs by masking of RNase E cleavage sites and protecting the transcripts from degradation, or activate translation by enhancing ribosome binding36,37,38. Additionally, CsrA also promotes premature transcription termination by altering Rho-dependent transcript structure39.

The Csr/Rsm system has been implicated in regulation of virulence in pathogenic bacteria. In P. aeruginosa, an rsmA mutation fails to cause actin depolymerization and cytotoxicity in bronchial epithelial cells due to its inability to secrete and translocate T3SS effector proteins40. In Xanthomonas campestris and X. oryzae, RsmA positively regulates exopolysaccharide production and T3SS41,42. In X.citri, RsmA stabilizes mRNA of the master regulator HrpG to activate T3SS30. In contrast, in P. carotovorum, the rsmA mutant was hypervirulent and produced higher levels of cell wall degrading enzymes40. In addition, RsmA negatively regulates T3SS in P. carotovorum by promoting degradation of the hrpL transcript, while rsmB is required for the hrpL expression43. Moreover, rsmB enhanced the stability of the hrpL transcript in Dickeya dadantii, suggesting that RsmA also negatively regulates the hrpL gene expression44. However, the role of CsrA-csrB system in E. amylovora has not been elucidated.

The goal of this study was to investigate the role of the CsrA-csrB system in E. amylovora virulence. Our results provide conclusive evidence that CsrA is a positive regulator of motility, amylovoran production, T3SS and virulence, while csrB sRNA, which is under the control of GrrS/GrrA TCST system13, negatively regulates these traits.

Results

CsrA and csrB sRNA from E. amylovora are highly conserved

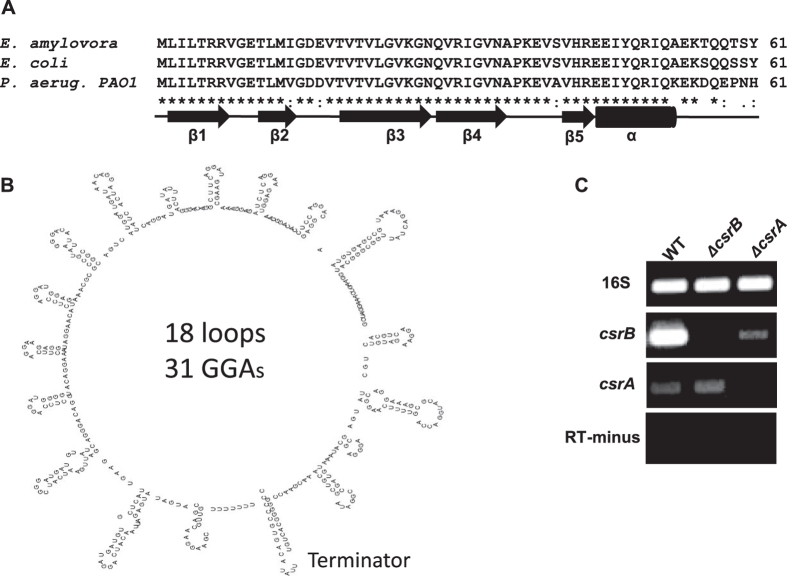

Analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence of E. amylovora CsrA (EAM_ 2637) shows that the 61-amino-acid protein is highly similar to its homologs CsrA from E. coli and RsmA from P. aeruginosa PAO1, sharing 97 and 85% identity, respectively (Fig. 1A). However, the csrB sRNA is not annotated in the E. amylovora sequenced genomes. Based on sequences reported in other species43,45, the csrB homolog sequence in E. amylovora EA273 genome was located about 200 bases downstream of EAM_2713 gene and 79 bases upstream of EAM_2712 gene (Supplementary Fig. S1). The non-coding csrB mRNA transcript is 455 nucleotides long and contains 31 GGA motifs, which are essential for CsrA binding46,47. The RNA folding prediction tool M-Fold predicted that the E. amylovora csrB RNA forms 18 loops, which could potentially sequester CsrA (Fig. 1B)47. Analysis of the upstream sequence of csrB showed that, starting 165 bases from the transcription start site, it contains 18 bp GacA binding site, TGTAAGAGATCGCTT GTA (underlined are conserved), indicating that csrB might be regulated by GacA (GrrA)48,49. An integration host factor (IHF)-binding site (TATCATCTGGTTA) in the upstream region of the rsmB sRNA was recently reported in E. amylovora50, and IHF was required for optimal GacA binding to and transcriptional activation of csrB in E. coli and S. enterica51.

Figure 1. Alignment of deduced amino acids of CsrA and secondary structure of csrB from Erwinia amylovora.

(A) Alignment of deduced amino acids of CsrA (accession # CBJ47311 and NP_417176) from E. amylovora and Escherichia coli; and RsmA (accession #AAG04294) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, and schematic map of the secondary structure of CsrA based on Schubert et al.56. Identical residues (*), conserved (:) and semi-conserved (.) substitutions are shown as underneath symbols. (B) Predicted secondary structure of csrB sRNA using the mfold program; (C) Gene expression of csrB and csrA by semi-quantitative PCR in wild type and the csrB and csrA mutants in MBMA medium. RT-minus indicates that no mRNA was added.

Semi-quantitative PCR was used to determine if CsrA or csrB affect each other’s RNA levels (Fig. 1C). As expected, corresponding PCR products were not detected in both mutant strains. The csrA RNA levels were not changed in the csrB mutant as compared to the wild type (WT) strain. In contrast, the csrB RNA levels were decreased about ∼60% in the csrA mutant relative to that of the WT strain (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that the csrB RNA may not be stable without CsrA protein, suggesting that CsrA is required for the csrB RNA accumulation, or that CsrA might indirectly stimulate csrB transcription by positively activating GrrA in a feedback regulation25,26,52.

Growth defect in the csrA mutant is independent from glycogen accumulation

During construction of the E. amylovora csrA mutant, we observed that the mutant grows very slowly in LB medium. Therefore, we evaluated the growth rate of the csrA and csrB mutant strains in both LB and MBMA media (Supplementary Fig. S2). The growth rate of the csrB mutant strain was similar to that of the WT in LB medium, while growth of the csrB mutant was slightly increased in MBMA medium (Supplementary Fig. S2A,B). However, growth of the csrA mutant was greatly reduced compared to the WT in LB and MBMA medium, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2A,B).

Since CsrA suppresses glycogen synthesis in E. coli, the excessive accumulation of glycogen impairs growth of a csrA deletion mutant and a glgCAP/csrA double mutation could restore the growth of the csrA mutant28. Therefore, we examined if a glgCAP mutation in E. amylovora could also restore the growth of the csrA mutant. Growth of the glgCAP mutant was similar to the WT in both media, whereas growth of the csrA/glgCAP double mutant only partially restored the growth of the csrA mutant in both media (Supplementary Fig. S2C,D). These results suggest that glycogen accumulation may not be responsible for the slow growth of the csrA mutant in E. amylovora.

We also determined whether CsrA-csrB regulates glycogen accumulation in E. amylovora. WT, glgCAP, csrA, and csrB mutants as well as the csrB complementation strain did not accumulate glycogen (Supplementary Fig. S3A)13. However, the csrA complementation strain showed increased glycogen accumulation, suggesting that in contrary to E. coli, E. amylovora CsrA protein positively regulates glycogen synthesis. In addition, these results further confirmed that the growth defect of the csrA mutant may not be due to increased glycogen accumulation.

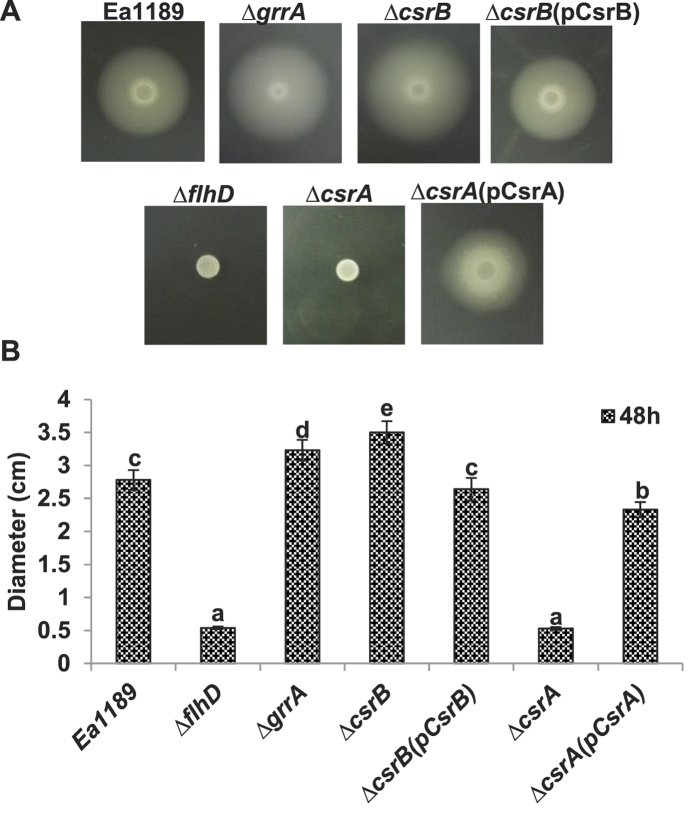

CsrA and csrB sRNA inversely regulate motility

We have previously reported that mutations on grrS /grrA gene exhibit increased motility compared to the WT strain6,13. Measurements of the diameters of the movement circles showed that the csrB mutant was hyper-motile similar to that of grrA mutant (Fig. 2A,B). In contrast, the csrA mutant was non-motile and remained restricted to the plating spot similar to the flhDC mutant (Fig. 2A,B). Complementation for the csrB and csrA mutants restored the motility to the WT levels (Fig. 2A). These results indicated that CsrA and csrB sRNA are positive and negative regulators of motility, respectively.

Figure 2. Effect of the csrA and csrB mutation on motility of Erwinia amylovora.

(A) motility of wild type, the grrA, flhD, csrA, csrB mutant and complementation strains on soft tryptone agar plates (3%) at 28 °C. Photographs were taken at 48 h; (B) Diameters of the circles were measured 48 h after inoculation.

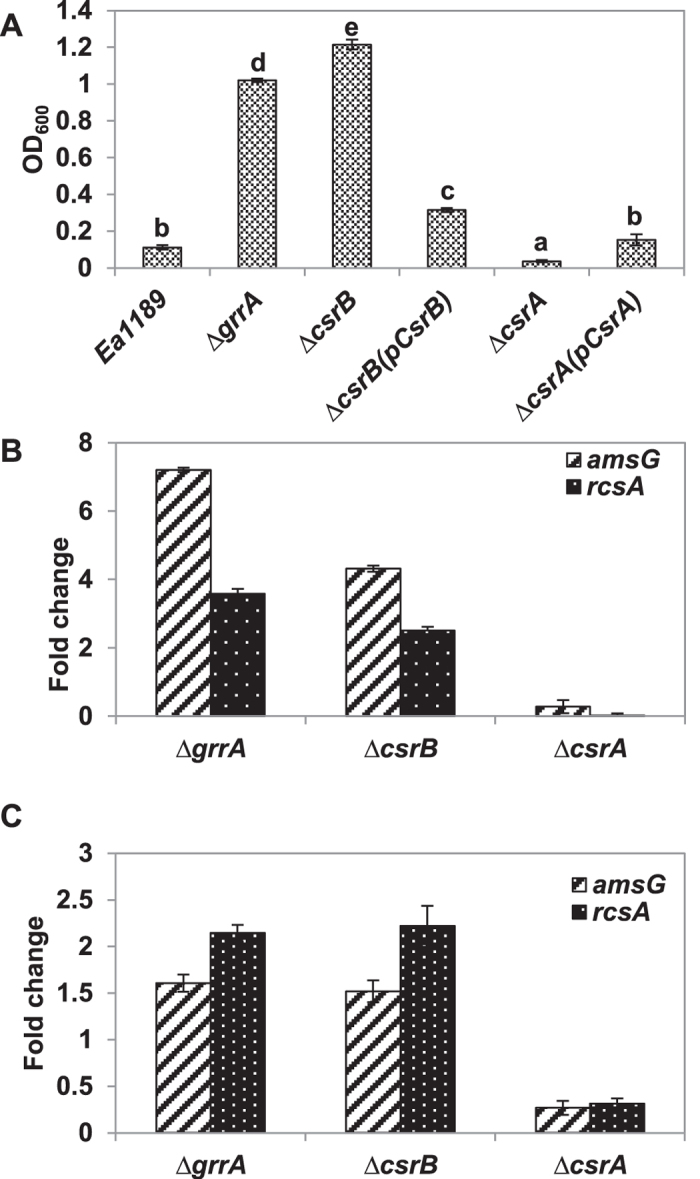

CsrA and csrB sRNA inversely regulate amylovoran production and amylovoran biosynthesis gene expression

We have previously reported that the GrrS/GrrA system negatively regulate amylovoran production in vitro6,13. The amount of amylovoran produced by the csrB mutant was ten folds higher than that of the WT after 24 h and similar to that of the grrA mutant (Fig. 3A), whereas the csrA mutant did not produce any amylovoran (Fig. 3A), which is similar to those of the rcsB and ams mutants5,6,14. Complementation of the csrB and csrA mutants partially restored amylovoran biosynthesis, producing approximately 0.31 and 0.15 units of OD600, respectively, as compared to 0.11 units for the WT. Consistent with amylovoran production, relative gene expressions of amsG (first gene of the amylovoran biosynthesis operon) and rcsA (a rate limit regulatory gene of amylovoran biosynthesis) in the csrB and grrA mutants were 4–7 and 2.5–3.5 fold higher, respectively, while their expressions were down-regulated 3.5 and more than 10 fold in the csrA mutant, respectively, as compared to the WT in vitro (Fig. 3B). Similarly, relative expression of amsG and rcsA genes in the csrA mutant was down-regulated 3.7 and 3.1 fold, respectively, as compared to the WT in vivo (Fig. 3C). In contrast, rcsA and amsG gene expression was increased by 2.2 and 1.5 fold in vivo in the csrB and grrA mutants as compared to the WT (Fig. 3C). These results indicated that CsrA is a positive regulator of rcsA gene expression and amylovoran production, while csrB negatively regulates expression of rcsA and amylovoran production.

Figure 3. Effect of the csrA and csrB mutation on amylovoran production and amylovoran biosynthesis and regulatory gene expression.

(A) Amylovoran production of wild type, the grrA, csrA, csrB mutants and complementation strains. Bacterial strains were grown in MBMA media supplemented with 1% sorbitol for 24 h at 28 °C with shaking. Amylovoran concentrations was measured by CPC method and normalized to a cell density of 1. Data points represent the means of three replicates ± standard deviations. OD600 = optical density at 600 nm. Each experiment was performed at least two times with similar results. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) Relative expression of amsG and rcsA genes in the grrA, csrB and csrA mutant strains compared to wild type in vitro by qRT-PCR. (C) Gene expression of amsG and rcsA genes in the grrA, csrB and csrA mutant strains as compared to wild type in vivo.

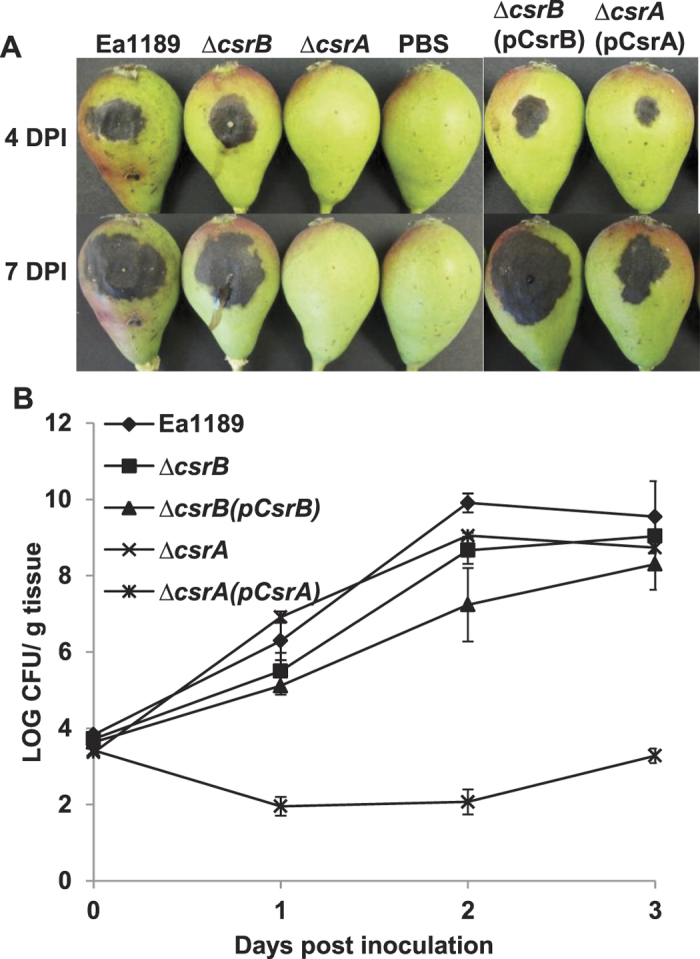

Mutation in csrA, but not csrB, renders E. amylovora non-pathogenic and abolishes its ability to elicit HR in tobacco

We then determined the ability of the csrA and csrB mutants in causing disease on immature pear fruits. For the csrA mutant, no symptoms were developed on immature pears, whereas complementation of the csrA mutant developed symptoms similar to that of the WT and the csrB mutant, but to a lesser degree (Fig. 4A). In addition, the csrA mutant was not able to elicit HR in tobacco, whereas WT, the csrB and complementation strains did (Supplementary Fig. S3B). These results demonstrated that CsrA, but not csrB, is required for causing disease and for eliciting HR in non-host tobacco.

Figure 4. Pathogenicity and growth of Erwinia amylovora wild type and mutant strains.

(A,B) Symptoms caused by wild type, the csrB and csrA mutants and their complementation strains on immature pear fruits. Immature pears were surface sterilized, pricked with a sterile needle and inoculated with 2 μL of bacterial suspensions. Symptoms were recorded and photos were taken at 4 and 7 days post-inoculation (dpi). (C) Growth of Erwinia amylovora wild type, mutants and complementation strains. Immature pears were surface sterilized, pricked with a sterile needle and inoculated with 2 μL of bacterial suspensions. Tissue surrounding the inoculation site was excised with a cork borer no.4 and homogenized in 1 mL of 0.5x PBS. Bacterial growth within the pear tissue was monitored after 1, 2 and 3 days post inoculation by dilution plating on LB with appropriate antibiotics.

In order to determine whether inability of the csrA mutant to cause disease is due to its ability in survival in planta, bacterial growth in pears for the csrA and csrB mutants were determined (Fig. 4B). At one day post inoculation (DPI), population of the WT, the csrB mutant, the csrB and csrA complementation strains increased from 4 log CFU/g tissue to 6.2, 5.4, 5.1, and 6.9 log CFU/g tissue, respectively. At two and three DPI, the population of these strains reached similar level, between 8–9 log CFU/g tissue. However, population of the csrA mutant decreased at one DPI, but gradually increased to 3.2 log CFU/g tissue at three DPI, which was about 6 log difference from that of the WT strain, but similar to the dspE and T3SS island deletion mutants6,11. This result indicated that the csrA mutant is able to survive in planta, but could not cause disease.

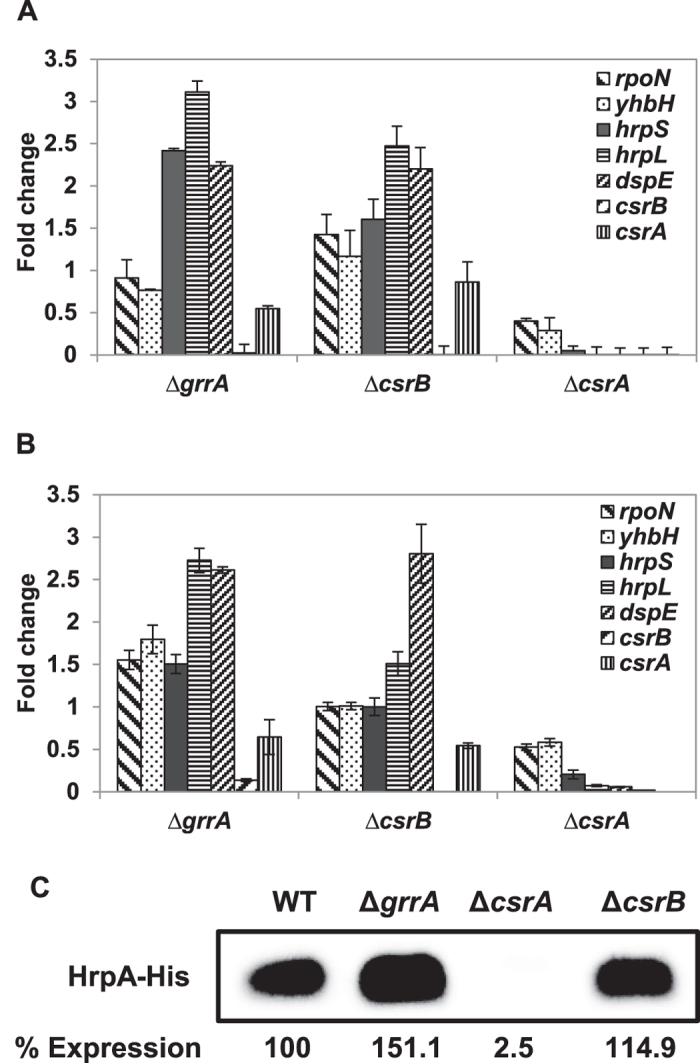

Expression of T3SS genes is abolished in the csrA mutant, but increased in the csrB mutant

To assess the role of CsrA and crsB on the expression of T3SS genes, we compared the relative expression of T3SS regulatory (rpoN, yhbH, hrpS, and hrpL) and dspE effector gene in grrA, csrB and csrA mutants to those of the WT. Expression of rpoN and yhbH was not affected in the csrB and grrA mutants under both in vitro and in vivo conditions, while expressions of hrpL and dspE were increased by 2.5–3 and 2.2 folds in vitro, and 1.5–2.5 and 2.5–2.8 folds in vivo, respectively (Fig. 5A,B). Expression of hrpS was not affected in the csrB mutant, but increased about 2.5 fold in the grrA mutant (Fig. 5A,B). In the csrA mutant, expression of rpoN and yhbH was down regulated by two folds under both in vitro and in vivo conditions; whereas expression of hrpS was down regulated by five and more than 10 folds under in vivo and in vitro conditions, respectively. Furthermore, hrpL and dspE expression was completely abolished in csrA mutant under both conditions. These results confirmed that T3SS gene expression is negatively regulated by csrB sRNA and positively regulated by CsrA.

Figure 5. Relative expression of type III secretion genes and accumulation of HrpA protein.

Relative expression of T3SS genes in the grrA,csrB and csrA mutant strains compared to wild type in HMM (A) and in pears (B). Relative gene expression of selected genes was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method, utilizing the 16S rRNA as endogenous control and compared to wild type strain. Fold changes were the result of the mean of three replicates. Each experiment was performed at least two times with similar results. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (C) Accumulation of HrpA protein is controlled by CsrA. Abundance of HrpA-His6 protein in WT, the grrA, csrA, and csrB mutant strains was detected by western blot using anti-histidine protein antibody after grown in hrp-inducing minimal medium (HMM) at 18 °C for 6 h. Relative protein abundance was calculated using ImageJ software by utilizing the average pixel value of the signals and utilizing the WT sample as 100%. Cropped blot was displayed and full length blot was presented in Supplementary Fig. S4 as a presentative of results obtained in repeated experiments.

Moreover, abundance of HrpA protein in WT and three mutants grown in HMM medium was detected by Western blot (Fig. 5C). Only approximately 2.5% protein signals were detected in the csrA mutant, but about 151 and 115% of protein signals were detected in the grrA and csrB mutants, respectively, as compared to that of the WT strain (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that CsrA is required for T3SS protein accumulation.

We also confirmed the relative expression of the csrA and csrB genes under the same condition. As expected, csrA and csrB expression was not detected in the csrA or csrB mutants, respectively (Fig. 5A,B). Expression of csrB was not detected in the csrA or grrA mutant strains (Fig. 5A,B), confirming the semi-quantitative PCR results that csrB is under direct control by GrrA51,53. In contrast, expression of csrA in the csrB mutant was not affected under in vitro condition, but down-regulated by two folds under in vivo condition, whereas expression of csrA in the grrA mutant was down-regulated by two folds under both conditions (Fig. 5A,B), suggesting CsrA is required for stabilizing csrB sRNA and expression of csrA is up-regulated in the WT in vivo.

Discussion

The GrrS/GrrA-csrB-CsrA system, composed of a two-component system, a non-coding small regulatory RNA csrB and a small RNA-binding protein CsrA, is a global dual regulatory system in many pathogenic and saprophytic bacteria54,55,56. Under certain environmental conditions, GrrS/GrrA system specifically activates the expression of csrB sRNA, which acts as a “molecular sponge” and binds to CsrA, thus sequestering and antagonizing its function16,47,53,54. The CsrA protein, which acts as a translational regulator, binds to target gene mRNA, either altering their translation or stability17,19. In this study, our results revealed a similar regulatory system exists in E. amylovora, and we have provided undeniable evidence that CsrA plays a central role in positively regulating virulence factors, while GrrS/GrrA-csrB act as a negative regulators, the latter antagonizing the positive role of CsrA. However, it remains to be determined whether the positive regulatory effect of CsrA on various virulence traits is direct or indirect.

As a global regulator, the GrrS/GrrA-csrB-CsrA system conveys pleiotropic effects on multicellular behavior, survival and virulence of various organisms, including glycogen accumulation, secondary metabolism, motility, EPS and enzyme production, T3SS and virulence17,19,54,57. As a dual regulator, this system acts as either negative or positive regulator depending on organisms or individual phenotype. However, the global effects of GrrS/GrrA were shown to be mediated by exclusively through its control over transcription of sRNAs in P. aeruginosa, E. coli and S. enterica51,53. Optimal GrrA binding to and transcription activation of csrB requires IHF in both E. coli and S. enterica51. In E. amylovora, mutation of GrrA/GrrS and csrB resulted in identical phenotypes, and expression of csrB also required IHF13,50, suggesting that the global effect of GrrS/GrrA might also be exclusively through control over the expression of csrB sRNA. Furthermore, the CsrA-csrB system in E. amylovora works very similarly to those reported in P. aeruginosa, where RsmA acts as a central positive regulator and the GrrS/GrrA- rsmB acts as a negative regulator31; contrary to those reported in other pseudomonads or in closely-related soft rot pathogens such as Pectobacterium and Dickeya21,44. Moreover, a csrA/glgCAP double mutant could not restore the slow growth of the csrA mutant in E. amylovora as it does in E. coli28, which may be due to that in E. amylovora, glycogen accumulation appears to be mainly regulated by another global regulator, the EnvZ/OmpR system13.

CsrA-mediated negative posttranscriptional regulation normally involves CsrA protein binding to the 5’ UTR or initially translated region of target mRNAs, which contains multiple CsrA-binding sites (GGA) and one overlapping with SD sequence47. Bound CsrA thus represses translation by competing with ribosome binding, leading to destabilization of the target mRNAs17,46. CsrA also can activate translation or stabilize target mRNAs by enhancing ribosome binding or by protecting the transcripts from RNase E-dependent degradation36,37. In E. amylovora, CsrA positively regulates motility as reported in E. coli and P. aeruginosa; and in contrast to those in Pectobacterium wasabiae and P. carotovorum38,58,59. It has been reported that CsrA in E. coli binds to two sites of the flhDC leader sequence and stabilizes the flhDC transcript by masking of the RNase E cleavage sites and protecting the transcript from degradation37. It is most likely that E. amylovora CsrA utilizes a similar mechanism to stabilize and protect the flhDC transcripts, which needs to be further proven.

Besides motility, CsrA also positively regulates both amylovoran production and T3SS in E. amylovora. The key question remaining is the underlying molecular mechanism of how CsrA positively regulates these virulence traits in E. amylovora. In E. amylovora, amylovoran biosynthesis is positively regulated by the RcsBCD phosphorelay system and RcsA, the rate limiting factor5,60; whereas GrrS/GrrA, EnvZ/OmpR, Lon protease, global regulator H-NS, and orphan protein AmyR (YbjN) are all known negative regulators of amylovoran production5,13,14,60,61,62,63. H-NS binds to the promoter of rcsA and suppresses its expression; whereas the RcsA protein is subject to Lon-dependent degradation. Additionally, AmyR/YjbN was characterized as a novel negative regulator of EPS production in both E. coli and E. amylovora and may act as a protein stabilizer62,63. Recent studies have shown that both lon and ybjN mRNA could be co-purified with CsrA protein in E. coli32, but CsrA only bound to the coding sequence of lon mRNA33. In this study, expression of rcsA gene was almost abolished in the csrA mutant. Therefore, further studies are needed to determine the molecular targets of CsrA in regulating amylovoran production.

In E. amylovora, transcription of the T3SS genes is positively activated by (p)ppGpp-mediated alternative sigma factor cascade, including the master regulator HrpL, alternative sigma factor RpoN, enhancer binding protein (EBP) HrpS, ribosome-binding protein YhbH, IHF, transcriptional factor DksA and (p)ppGpp biosynthesis proteins RelA and SpoT7,8,10,64; whereas GrrS/GrrA and EnvZ/OmpR systems negatively regulates T3SS gene expression13. In P. carotovorum, expression of hrpL is positively regulated by GacA/GacS-rsmB system, while RsmA negatively controls its expression43. Positive regulation of T3SS by RsmA is also reported in P. aeruginosa, X. campestris and X. citri30,31,40,41. It has been reported that RsmA activates T3SS by stabilizing the 5′ UTR of HrpG mRNA in Xanthomonas, suggesting that RsmA may regulate T3SS gene expression through HrpG, the master regulator of T3SS30. In addition, (p)ppGpp-mediated stringent response and CsrA regulons shared extensive overlap, suggesting that regulatory interaction exists between CsrA and (p)ppGpp-mediated stringent response regulatory system17,32. Therefore, CsrA -dependent control of T3SS gene expression via major transcription regulatory factors might be a conserved feature among pathogenic bacteria19. In this study, our results showed that CsrA is required for expression of T3SS genes in E. amylovora, including rpoN, yhbH, hrpS and hrpL regulatory genes, suggesting that these major regulatory genes might be potential targets of CsrA in E. amylovora. Additionally, a lon mutation in P. syringae increases the stability and accumulation of HrpR, another EBP similar to HrpS65,66. Therefore, future studies are needed to uncover the molecular mechanisms as how CsrA positively regulates T3SS in E. amylovora.

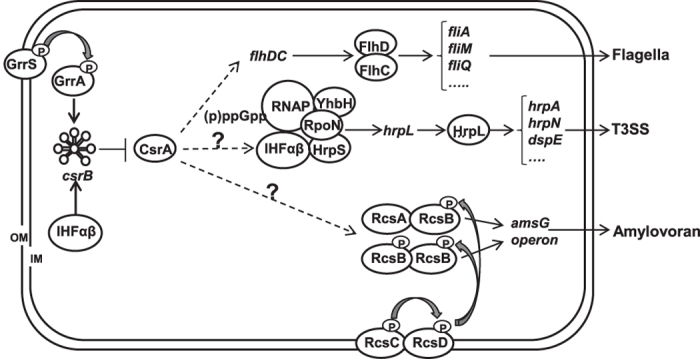

Based on our results and previous reported data7,8,9,10,13,14,50,60, we proposed the following working model as how the GrrS/GrrA-csrB-CsrA system might regulate virulence traits in E. amylovora (Fig. 6). In E. amylovora, the T3SS is activated by (p)ppGpp-mediated RpoN-HrpL sigma factor cascade; whereas amylovoran biosynthesis is positively regulated by the RcsABCD TCST system. In addition, the global GrrA/GrrS TCST along with integration host factor (IHF) specifically regulates the expression of csrB sRNA, which acts as a “sponge” to antagonize the effect of CsrA13,25,49,50,51,53. As discussed above, CsrA is a positive regulator of motility in E. amylovora possibly by stabilizing and protecting flhDC transcript from RNase E degradation as previously reported37. However, the targets of CsrA in positively regulating T3SS and amylovoran biosynthesis remain unknown. Currently, we are focusing on uncovering the underlying molecular mechanism of CsrA as a central positive regulator of virulence factors in E. amylovora.

Figure 6. A working model illustrated the role of the RNA-binding protein CsrA in Erwinia amylovora.

This model is based on findings obtained in this study as well as those reported in previously studies7,8,9,10,13,14,50,60. FlhDC: master regulator of flagellar formation; HrpL: an ECF sigma factor and master regulator of T3SS; HrpS: a σ54-dependent enhancer binding protein; Ihfα/β: integration host factor αβ; RpoN: a σ54 alternative sigma factor; YhbH: σ54 modulation protein (ribosome-associated protein); RNAP: RNA polymerase. (p)ppGpp: guanosine tetraphosphateand guanosine pentaphosphate; GrrS/GrrA; RcsABCD: two-component regulatory systems; csrB: small non-coding regulatory RNA; CsrA: RNA-binding protein; OM, outer membrane; IM, inner membrane; P, phosphorylation. Symbols: ↓, positive effect; ⊥, negative effect; dash line with/without ?: unknown mechanism.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. LB broth was used for routine growth of E. amylovora and E. coli strains. For amylovoran production assays, bacteria were grown in MBMA medium (3 g KH2PO4, 7 g K2HPO4, 1g [NH4]2SO4, 2 mL glycerol, 0.5 g citric acid, 0.03 g MgSO4) supplemented with 1% sorbitol5. A hrp-inducing minimum medium (HMM) (1g [NH4]2SO4, 0.246 g MgCl2•6H2O, 0.1 g NaCl. 8.708 g K2HPO4, 6.804 g KH2PO4) with 10 mM galactose as carbon source was used for inducing T3SS gene expression8,67. When required, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: 50 μg mL−1 Kanamycin, 100 μg mL−1 Ampicillin and 10 μg mL−1 chloramphenicol. Primers used for mutant construction, mutant confirmation, RT-qPCR and cloning in this study are listed in Table S1.

Table 1. Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains or plasmids | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. amylovora | ||

| Ea1189 | Wild type, isolated from apple | 71 |

| Z2946∆flhD | flhD::Km; KmR-deletion mutant of flhD of Ea1189, KmR | 14 |

| ∆csrA | csrA::Cm; CmR-deletion mutant of csrA of Ea1189, CmR | This study |

| ∆csrB | csrB::Cm; CmR-deletion mutant of csrB of Ea1189, CmR | 13 |

| ∆glgCAP | CmR-deletion mutant of glgCAP operon (5.2 kb) of Ea1189, CmR | This study |

| ∆csrA/glgCAP | csrA::Cm, glgCAP::Km; KmR-deletion mutant of glgCAP into ∆csrA | This study |

| Z2198∆grrA | grrA::Km; KmR-deletion mutant of grrA of Ea1189, KmR | 14 |

| DH10B E. coli strain | F– mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) Φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 endA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu) 7697 galU galK rpsL nupG λ | Invitrogen, CA |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKD46 | ApR, PBAD gam bet exo pSC101 oriTS | 68 |

| pKD32 | CmR, FRT cat FRT tL3 oriR6Kγ bla rgnB | 68 |

| pkD13 | KmR, FRT kan FRT tL3 oriR6Kγ bla rgnB | 68 |

| pHrpA-His6 | 803-bp DNA fragment containing promoter sequence of the hrpA gene and c-terminal His tag in pWSK29 | 8 |

| pGem®T-easy | ApR, PCR cloning vector | Promega WI |

| pCsrA | A 824 bp fragment containing csrA gene in pGemT-easy vector | This study |

| pCsrB | A 1.3-kb fragment containing csrB in pGemT-easy vector | This study |

Generation of single and double mutants by λ–Red recombinase cloning

E. amylovora mutant strains were generated using λ phage recombinase method as describe previously6,68. Briefly, overnight cultures of E. amylovora strains harboring pKD46 were inoculated in LB broth containing 0.1% arabinose and grown to exponential phase (OD600 = 0.8). Cells were harvested, made electrocompetent and stored at −80 °C. These cells were electroporated with recombination fragments of cat or kan genes with their own promoter. Cat and kan fragments were obtained by PCR amplification from pKD32 or pKD13 plasmids, respectively, flanked by a 50-nucleotide homology from the target genes. To confirm csrA, csrB, and glgCAP mutations, PCR amplifications from internal cat or kan primers to the external region of the target genes were performed. The coding region of the csrA, csrB, and glgCAP genes was absent from the corresponding mutant strains, except for the first and last 50 nucleotides.

Construction of the csrA and csrB complementation plasmids

For complementation of the mutant strains, the genomic region containing the promoter and gene sequence of csrA and csrB were PCR amplified, gel purified and cloned into pGEM-T-easy vector according to manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, WI). Plasmid DNA purification, PCR amplification of genes, isolation of fragments from agarose gels were performed using standard molecular procedures69. Plasmid verification was performed by sequencing at the UIUC Core Sequencing Facility. Final plasmids were designated as pCsrA and pCsrB and transformed by electroporation into corresponding mutant strains.

Motility assay

Bacterial strains were grown overnight in LB with appropriate antibiotics, harvested by centrifugation and washed three times with PBS. Bacterial suspensions were adjusted to an OD600 equal to 1.0, and 5 μL drops were placed onto the center of agar plates (10 g tryptone, 5 g NaCl, 3 g agar per liter) as previously described14. Plates were incubated at 28 °C and movement diameters were measured after 48 h post inoculation. The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times.

CPC assay to determine amylovoran concentration

Amylovoran concentration of the WT, mutant and complementation strains was quantitatively determined by the cetylpyrimidinium chloride (CPC) method as previously described70. Briefly, overnight cultures of bacterial strains were harvested by centrifugation and washed three times with PBS. Five mL MBMA medium supplemented with 1% sorbitol were inoculated to a final OD600 of 0.2 and incubated at 28 °C with shaking. After 24 h, 1 mL of each culture was centrifuged at 7,000 rpm for 10 min and 50 μL of CPC at 50 mg mL−1 was added to the supernatant. After 10 min of incubation, the turbidity of the suspension and cell density was determined by measuring OD600. Amylovoran was determined by normalizing the OD600 of the suspension to a cell density of 1.0. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times.

RNA isolation

Bacterial strains grown overnight in LB media with appropriate antibiotics were harvested by centrifugation and washed three times with 0.5X PBS before inoculating 5 mL of MBMA medium supplemented with 1% sorbitol. For hrp-inducing conditions, bacterial cells were washed three times with HMM before inoculated 5 mL of medium to a final OD600 = 0.2. After 18 h incubation for MBMA at 28 °C or 6 h incubation for HMM at 18 °C, 2 mL of RNA protect reagent (Qiagen) was added to 1 mL of bacterial cell culture mixed by vortex and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and RNA was extracted using RNeasy® mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNase I treatment was performed in column before elution and RNA was quantified using Nano-drop ND100 spectrophotometer. For in vivo conditions, overnight cultures of bacterial strains were harvested by centrifugation, washed three times and suspended in PBS. Immature pear fruits were cut in half and inoculated with bacterial suspensions. After 6 h incubation at 28 °C in a moist chamber, bacterial cells were collected by washing pear surfaces with RNA protect reagent (Qiagen) 2:1 with water and total RNA was extracted as described above.

Reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. One μL of cDNA was used as template for qPCR performed using the ABI 7300 System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Power SYBR® Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) was used to detect gene expression of selected genes with primers designed using Primer3 software. qPCR amplifications were carried out at 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. Dissociation curve analysis was performed after the program was completed to confirm amplification specificity. Three technical replicates were performed for each biological sample. Relative gene expression levels were calculated with the 2−∆∆Ct method using the 16s rRNA (rrsA) as endogenous control and wild type as reference value.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA from MBMA medium was extracted and reverse transcribed as described above. PCR reactions were performed on 10 ng of cDNA using csrA-rt and csrB-rt and 16S-rt primers listed in Table S1. RNA samples were used as template for RT-minus controls. PCR amplification was carried out at 94 °C for 2 min, followed 20 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s. PCR products were separated on an ethidium bromide pre-stained 1% agarose gel, and visualized in a Molecular Imager® Gel Doc™ XR System (Bio-Rad).

Virulence assays on immature pear fruits

Virulence assays were performed as described previously11,12. Briefly, overnight cultures of E. amylovora WT, mutants and complementation strains were harvested by centrifugation and suspended in 0.5x PBS. Immature pear fruits (Pyrus communis L. cv. ‘Bartlett’) were surface sterilized with 10% bleach, pricked with a sterile needle and inoculated with 2 μL of 100 X dilution of bacterial suspensions at OD600 = 0.1. Inoculated pears were incubated at 28 °C in a humidity chamber and disease symptoms were recorded after 4 and 7 days post inoculation. The experiment was performed in triplicate at least three times. For bacterial population studies, pears were inoculated as described above and the tissue surrounding the inoculation site was excised with a cork borer no.4 and homogenized in 1 mL of 0.5x PBS. Bacterial growth within the pear tissue was monitored after 1, 2 and 3 days post inoculation by dilution plating on LB with appropriate antibiotics11,12. For each time point and strain tested, fruits were assayed in triplicate. The experiment was performed three times.

Western blot

E. amylovora cells grown in HMM at 18 °C for 6 h were harvested, and equal amount of cell lysates was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels8. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore) and blocked with 5% milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To detect HrpA-6His, membranes were probed with rabbit anti-His antibodies (GeneScript, Piscataway, NJ) that were diluted to 1.0 μg/ml with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST). Immunoblots were then developed with horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (Amersham Biosciences) diluted 1: 10,000 in PBST, followed by enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Pierce). Images of the resulting blots were acquired using ImageQuant LAS 4010 CCD camera (GE Healthcare). The experiment was performed at least three times.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA and Student-Newmans-Kleus test (p = 0.05) was used to analyze the data. For WT, mutants and complementation strains, changes marked with the same letter did not differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Ancona, V. et al. The RNA-binding protein CsrA plays a central role in positively regulating virulence factors in Erwinia amylovora. Sci. Rep. 6, 37195; doi: 10.1038/srep37195 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program Grant no. 2016-67013-24812 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the Agricultural Experiment Station of Illinois, and University of Illinois.

Footnotes

Author Contributions V.A., J.H.L. and Y.Z. conceived and designed the experiments; V.A. and J.H.L. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; V.A. and Y.Z. wrote the manuscript.

References

- Khan M. A., Zhao Y. F. & Korban S. S. Molecular mechanisms of pathogenesis and resistance to the bacterial pathogen Erwinia amylovora, causal agent of fire blight disease in Rosaceae. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 30, 247–260 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. F. Genomics of Erwinia amylovora and related species associated with pome fruit trees. In Genomics of Plant-Associated Bacteria. Dennis Gross Ann Lichens-Park & Kole Chittaranjan (eds). pp1–36 (Springer, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. F. & Qi M. Comparative Genomics of Erwinia amylovora and related Erwinia Species-What do We Learn? Genes 2, 627–639 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh C.-S. & Beer S. V. Molecular genetics of Erwinia amylovora involved in the development of fire blight. Fed. Eur. Microbiol. Soc. Lett. 253, 185–192 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Korban S. S. & Zhao Y. F. The Rcs phosphorelay system is essential for pathogenicity in Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Plant Pathol. 10, 277–290 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. F., Sundin G. W. & Wang D. Construction and analysis of pathogenicity island deletion mutants of Erwinia amylovora. Can. J. Microbiol. 55, 457–464 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancona V., Li W. & Zhao Y. F. Alternative sigma factor RpoN and its modulator protein YhbH are indispensable for Erwinia amylovora virulence. Mol. Plant Pathol. 15, 58–66 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ancona V. et al. The bacterial alarmone (p)ppGpp activates type III secretion system in Erwinia amylovora. J. Bacteriol. 197, 1433–1443 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Sundin G. W. & Zhao Y. F. Identification of the HrpS binding site in the hrpL promoter and effect of the RpoN binding site of HrpS on the regulation of the type III secretion system in Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Plant Pathol. 17, 691–702 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally R. R. et al. Genetic characterization of the HrpL regulon of the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora reveals novel virulence factors. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13, 160–173 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. F., Blumer S. E. & Sundin G. W. Identification of Erwinia amylovora genes induced during infection of immature pear tissue. J. Bacteriol. 187, 8088–8103 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. F., He S.-Y. & Sundin G. W. The Erwinia amylovora avrRpt2EA gene contributes to virulence on pear and AvrRpt2EA is recognized by Arabidopsis RPS2 when expressed in Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19, 644–654 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Ancona V. & Zhao Y. F. Co-regulation of polysaccharide production, motility, and expression of T3SS genes by EnvZ/OmpR and GrrS/GrrA systems in Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Genet. Genomics 289, 63–75 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. F., Wang D., Nakka S., Sundin G. W. & Korban S. S. Systems level analysis of two-component signal transduction systems in Erwinia amylovora: role in virulence, regulation of amylovoran biosynthesis and swarming motility. BMC Genomics 10, 245 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koczan J. M., McGrath M., Zhao Y. F. & Sundin G. W. The contribution of the exopolysaccharide amylovoran and levan to biofilm formation: Implication in pathogenicity. Phytopathology 99, 1237–1244 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duss O. et al. Structural basis of the non-coding RNA RsmZ acting as a protein sponge. Nature 509, 588–592 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo T., Vakulsas C. A. & Babitzke P. Post-transcriptional regulation on a global scale: form and function of Csr/Rsm systems. Envrion. Microbiol. 15, 313–324 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans J. & Van Melderen L. Conditional essentiality of the csrA gene in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 191, 1722–1724 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakulskas C. A., Potts A. H., Babitzke P., Ahmer B. M. M. & Romeo T. Regulation of bacterial virulence by Csr (rsm) systems. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 79, 193–224 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altier C., Suyemoto M., Ruiz A. I., Burnham K. D. & Maurer R. Characterization of two novel regulatory genes affecting Salmonella invasion gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 35, 635–646 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A. et al. GacA, the response regulator of a two-component system, acts as a master regulator in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 by controlling regulatory RNA, transcriptional activators, and alternate sigma factors. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 16, 1106–1117 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Chatterjee A. & Chatterjee A. K. Effects of the two-component system comprising GacA and GacS of Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora on the production of global regulatory rsmB RNA, extracellular enzymes, and harpinEcc. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 14, 516–526 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortune D. R., Suyemoto M. & Altier C. Identification of CsrC and characterization of its role in epithelial cell invasion in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 74, 331–339 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay E. et al. Two GacA-dependendt small RNAs modulate the quorum-sensing response in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 188, 6026–6033 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K. et al. Regulatory Circuitry of the CsrA/CsrB and BarA/UvrY Systems of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184, 5130–5140 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Weilbacher T. et al. A novel sRNA component of the carbon storage regulatory system of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 657–670 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo T., Gong M., Liu M. Y. & Brun-Zinkernagel A. M. Identification and molecular characterization of csrA, a pleiotropic gene from Escherichia coli that affects glycogen biosynthesis, gluconeogenesis, cell size, and surface properties. J. Bacteriol. 175, 4744–4755 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans J. & Van Melderen L. Post-transcriptional global regulation by CsrA in bacteria. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67, 2897–2908 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimmann C., Valverde C., Kay E. & Haas D. Posttranscriptional repression of GacS/GacA-controlled genes by the RNA-binding protein RsmE acting together with RsmA in the biocontrol strain Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. J. Bacteriol. 187, 276–285 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade M. O., Farah C. S. & Wang N. The post-transcriptional regulator RsmA/CsrA activates T3SS by stabilizing the 5′ UTR of hrpG, the master regulator of hrp/hrc genes, in Xanthomonas. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1003945 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brencic A. & Lory S. Determination of the regulon and identification of novel mRNA targets of Pseudomonas aeruginosa RsmA. Mol. Microbiol. 72, 612–632 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A. N. et al. Circuitry linking the Csr and stringent response global regulatory systems. Mol. Microbiol. 80, 1561–1580 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist E. et al. Global RNA recognition patterns of post-transcriptional regulators Hfq and CsrA revealed by UV crosslinking in vivo. EMBO J. 35, 991–1011 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babitzke P. & Romeo T. CsrB sRNA family: sequestration of RNA-binding regulatory proteins. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 156–163 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo T. Global regulation by the small RNA-binding protein CsrA and the non-coding RNA molecule csrB. Mol. Microbiol. 29, 1321–1330 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren B., Shen H., Lu Z. J., Liu H. & Xu Y. The phzA2-G2 transcript exhibits direct RsmA-mediated activation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa M18. PloS ONE 9, e89653 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakhnin A. V. et al. CsrA activates flhDC expression by protecting flhDC mRNA from RNase E-mediated cleavage. Mol. Microbiol. 87, 851–866 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei B. L. et al. Positive regulation of motility and flhDC expression by the RNA-binding protein CsrA of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 40, 245–256 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa-Bossi N. et al. RNA remodeling by bacterial global regulator CsrA promotes Rho-dependent transcription termination. Genes Dev. 28, 1239–1251 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy H., O’Callaghan J., O’Grady E. P., Adams C. & O’Gara F. The posttranscriptional regulator RsmA plays a role in the interaction between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and human airway epithelial cells by positively regulating the type III secretion system. Infect. Immun. 74, 3012–3015 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao N. X. et al. The rsmA-like gene rsmAXcc of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris is involved in the control of various cellular processes, including pathogenesis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 21, 411–423 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P. L., Zhao S., Tang J. L. & Feng J. X. The rsmA-like gene rsmAXoo of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae regulates bacterial virulence and production of diffusible signal factor. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12, 227–237 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A., Cui Y. & Chatterjee A. K. Regulation of Erwinia carotovora hrpL(Ecc), which encodes an extracytoplasmic function subfamily of sigma factor required for expression of the HRP regulon. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 15, 971–980 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zeng Q., Ibekwe A. M., Biddle E. & Yang C.-H. Regulatory mechanisms of exoribonuclease PNPase and regulatory small RNA on T3SS of Dickeya dadantii. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 23, 1345–1355 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A., Cui Y. & Chatterjee A. K. RsmA and the quorum-sensing signal, N-[3-Oxohexanoyl]- L-homoserine lactone, control the levels of rsmB RNA in Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora by affecting its stability. J. Bacteriol. 184, 4089–4095 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey A. K., Baker C. S., Romeo T. & Babitzke P. RNA sequence and secondary structure participate in high-affinity CsrA-RNA interaction. RNA 11, 1579–1587 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapouge K. et al. RNA pentaloop structures as effective targets of regulators belonging to the RsmA/CsrA potein family. RNA Biol. 10, 1031–1041 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humair B., Wackwitz B. & Haas D. GacA-controlled activation of promoters for small RNA genes in Pseudomonas fluorescens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 1497–1506 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde C., Heeb S., Keel C. & Haas D. RsmY, a small regulatory RNA, is required in concert with RsmZ for GacA-dependent expression of biocontrol traits in Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. Mol. Microbiol. 50, 1361–1379 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H. & Zhao Y. F. Integration host factor is required for RpoN-dependent hrpL gene expression and controls motility by positively regulating rsmB sRNA in Erwinia amylovora. Phytopathology 106, 29–36 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zere T. R. et al. Genomic targets and features of BarA-UvrY (-SirA) signal transduction systems. PLoS One 10, e0145035 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudapaty S., Suzuki K., Wang X., Babitzke P. & Romeo T. Regulatory interactions of Csr components: the RNA binding protein CsrA activates csrB transcription in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183, 6017–6027 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brencic A. et al. The GacS/GacA signal transduction system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa acts exclusively through its control over the transcription of the RsmY and RsmZ regulatory small RNAs. Mol. Microbiol. 73, 434–445 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapouge K., Schubert M., Allain F. H. T. & Haas D. Gac/Rsm signal transduction pathway of γ-proteobacteria: from RNA recognition to regulation of social behaviour. Mol. Microbiol. 67, 241–253 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen H., Sivaneson M. & Filloux A. Key two-component regulatory systems that control biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 1666–1681 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert M. et al. Molecular basis of messanger RNA recognition by the specific bacterial repressing clamp RsmA/CsrA. Nature Struc. Mol. Biol. 14, 807–813 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heroven A. K., Böhme K. & Dersch P. The Csr/Rsm system of Yersinia and related pathogens: a post-transcriptional strategy for managing virulence. RNA Biol. 9, 379–391 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A., Cui Y., Chakrabarty P. & Chatterjee A. K. Regulation of motility in Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora: quorum-sensing signal controls FlhDC, the global regulator of flagellar and exoprotein genes, by modulating the production of RsmA, an RNA-binding protein. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23, 1316–1323 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kõiv V. et al. Lack of RsmA-mediated control results in constant hypervirulence, cell elongation, and hyperflagellation in Pectobacterium wasabiae. PloS ONE 8, e54248 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. et al. Genome-wide identification of genes regulated by the Rcs phosphorelay system in Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 25, 6–17 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand M., Aldridge P. & Geider K. Characterization of hns genes from Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Genet. Genomics 275, 310–319 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. et al. The orphan gene ybjN conveys pleiotropic effects on multicellular behavior and survival of Escherichia coli. PloS One 6, e25293 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Korban S. S., Pusey P. L. & Zhao Y. F. AmyR is a novel negative regulator of amylovoran production in Erwinia amylovora. PloS One 7, e45038 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z., Kim J. F. & Beer S. V. Regulation of hrp genes and type III protein secretion in Erwinia amylovora by HrpX/HrpY, a novel two-component system, and HrpS. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13, 1251–1262 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bretz J., Losada L., Lisboa K. & Hutcheson S. W. Lon protease functions as a negative regulator of type III protein secretion in Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Microbiol. 45, 397–409 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson S. W., Bretz J., Sussan T., Jin S. & Pak K. Enhancer-binding proteins HrpR and HrpS interact to regulate hrp-encoded type III protein secretion in Pseudomonas syringae strains. J. Bacteriol. 183, 5589–5598 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F. et al. Small-molecule inhibitors suppress the expression of both type III secretion and amylovoran biosynthesis genes in Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Plant Pathol. 15, 44–57 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko K. A. & Wanner B. L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6640–6645 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J. & Russel D. Molecular Cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.(Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Bellemann P., Bereswill S., Berger S. & Geider K. Visualization of capsule formation by Erwinia amylovora and assays to determine amylovoran synthesis. Int.J. Biol. Macromol. 16, 290–296 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Korban S. S. & Zhao Y. F. Molecular signature of differential virulence in natural isolates of Erwinia amylovora. Phytopathology 100, 192–198 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.