Abstract

In this study, we proposed a Regional Probabilistic Risk Assessment (RPRA) to estimate the health risks of exposing residents to heavy metals in different environmental media and land uses. The mean and ranges of heavy metal concentrations were measured in water, sediments, soil profiles and surface soils under four land uses along the Shunde Waterway, a drinking water supply area in China. Hazard quotients (HQs) were estimated for various exposure routes and heavy metal species. Riverbank vegetable plots and private vegetable plots had 95th percentiles of total HQs greater than 3 and 1, respectively, indicating high risks of cultivation on the flooded riverbank. Vegetable uptake and leaching to groundwater were the two transfer routes of soil metals causing high health risks. Exposure risks during outdoor recreation, farming and swimming along the Shunde Waterway are theoretically safe. Arsenic and cadmium were identified as the priority pollutants that contribute the most risk among the heavy metals. Sensitivity analysis showed that the exposure route, variations in exposure parameters, mobility of heavy metals in soil, and metal concentrations all influenced the risk estimates.

Rapid urbanization and industrialization have released toxic chemicals such as heavy metals into the environment, threatening human health1,2. Pollution assessment methods such as the Pollution Index and Enrichment Factors are commonly used to rapidly evaluate pollution levels in specific sampling sites that adopt national environment standard values or natural background values as the reference concentrations3,4. These assessments ignore the actual connections between contaminants and human health and are inherently inadequate to address how human behaviors and land use patterns affect the health risks posed by pollution. Health risk assessments evaluate the probability of deleterious effects by constructing conceptual risk models in terms of risk sources (pollutants in various environmental media), exposure routes, and risk receptors (the sensitive population)5,6. Health risk assessment was first used in field-scale studies such as evaluating contamination at Superfund sites6. Health risk assessments are therefore capable of distinguishing contaminated sites from virtually safe areas, identifying pathways of the highest risks for a given land use or at a site, and guiding the control of priority pollutants that are threatening human health7,8,9.

Health risk assessment retains large uncertainties in the procedure of exposure assessment10. Using soil as an example, the exposure routes of heavy metals in the environment include oral intake, dermal contact and inhalation. Calculating exposure frequency and durations of heavy metals to the sensitive population involves many site- or chemical-specific parameters11. Traditional health risk assessment is a deterministic process that adopts the reasonable maximum exposure parameters to obtain a conservative result12. However, deterministic risk assessments may under- or over-estimate the risks and, hence, are unconvincing13. In contrast, probabilistic risk assessment (PRA) attempts to characterize uncertainty and variability by calculating the risks based on the range and statistical distribution of the exposure parameters14. Thus, PRA provides complete and detailed risk information for environmental management15. Practical illustrations of PRA were limited because the computation processes and input data collection are more complicated and difficult than other assessment techniques16. Nevertheless, PRA is necessary for obtaining the risk distributions and evaluating the importance of each exposure route or input parameter in affecting the total risks.

Recently, regional heavy metals pollution caused by urbanization and industrialization has drawn great attention2,17. Different environmental media and land uses dramatically alter heavy metals exposure routes and the sensitive population. For example, river sediment may threaten only the population that swims periodically, whereas residential soils pose potential risks to children playing on the ground, and agricultural soils are sources of exposure to farmers5,18,19. The consideration of multiple media and multiple land uses in risk assessment introduces more parameters and uncertainties into the analysis16. Therefore, the traditional health risk assessments commonly focused on single media or land use12,13,20,21. At a regional scale, PRA would be more suitable for evaluating health risks than deterministic risk assessment as it can provides statistical information that explains spatial variations and individual differences20. It is imperative to include multimedia and land uses into regional-scale PRA. An ideal way is to identify firstly risk receptors (the most sensitive population) and exposure routes according to each media and land use, and then calculate risk probabilities respectively.

Drinking water supply areas in China are facing challenges because rapid urbanization has extended the sphere of urban influence17. Previous research showed that heavy metals accumulating in vegetable soils of flooded riverbank were significantly higher than non-flooded vegetable soils11. The Shunde Waterway, which is the drinking water source for the cities of Foshan and Guangzhou, was once located far away from the cities but has become incorporated into the suburban areas of Foshan during the urban sprawl process (Fig. S1). The increasing activity of the manufacturing industry in this area is threatening the safety of drinking water sources, and the growth of population has caused conversion of once-barren land to public green space and vegetable plots. The levels of risk exposure to heavy metals in this area are of concern, especially in vegetable soils near the flooded riverbank. In the study described herein, Regional-scale Probabilistic Risk Assessment (RPRA) was proposed to evaluate the health risks of heavy metals in the Shunde Waterway area as a function of different media and land uses. The purposes of the study were to demonstrate the application of PRA on regional scale and to identify heavy metal species that pose the highest risks and the priority exposure routes.

Materials and Methods

Procedures of probabilistic risk assessment at regional scale

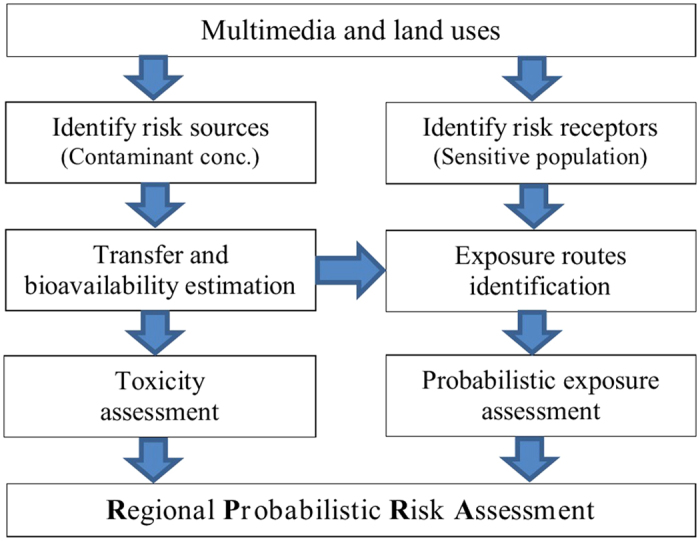

Health risk assessment involves several general procedures including (1) identification of risk sources and receptors, (2) exposure assessment, (3) toxicity analysis and (4) risk characterization6. Based on the general procedures of health risk assessment, we proposed a framework for regional probabilistic risk assessment under different land use and environmental media (Fig. 1). The risk sources are the heavy metals in the various environmental media, and the risk receptors are the most sensitive population varying with the media and land use types. The exposure routes and frequencies vary according to daily behaviors of the sensitive population. Coupled with Monte Carlo simulation, RPRA incorporates parameter variation into the calculation of the first two steps. The individual differences and spatial variations are represented by the ranges and distributions of the data parameters.

Figure 1. Framework of Regional-scale Probabilistic Risk Assessment (RPRA).

Non-carcinogenic risks arising from exposure to heavy metals in three media (water, sediment and soil) and two land uses (green space soil and agricultural soil) were evaluated. For soil, the sensitive population of green space was considered to be the residents who have regular outdoor activities; and the sensitive population of vegetable plots was farmers who worked on the sites. Exposure routes included incidental oral ingestion of soil particles, dermal contact with soil particles and inhalation of soil dust during outdoor activities. Additional risks posed by ingestion of groundwater and vegetables, by which heavy metals were transferred from soils, also were calculated. For water and sediments, the sensitive population was comprised of residents who have regular swimming activities. The exposure routes for these residents included the daily intake of water, incidental intake of sediment and dermal contact with water and sediment during swimming. The carcinogenic risks were not considered in the current study due to most of the metals are lack of validated carcinogenic slope factor to evaluate their carcinogenic effect8.

Risk assessment models

The non-carcinogenic health risks represented as hazard quotients (HQs) are equal to the chronic daily intake (CDI) divided by the chronic reference dose (RfD). Therefore, the risk assessment models vary depending on exposure routes such as oral ingestion, dermal contact and inhalation.

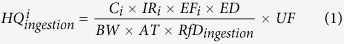

For ingestion of soil particles, sediment particles, surface water and ground water, the health risk models can be written as Eq. (1)7,22:

|

where i represents a target media or land use. IRi represents the ingestion rate, including soil ingestion rate IRs (mg/d), sediment ingestion rate IRsd (mg/d), daily water ingestion rate IRw (mL/d); and EFi represents the exposure frequency (d/yr) for indoor activities EFia, outdoor activities EFoa and swimming EFsd, respectively. ED indicates the exposure duration (yr), BW indicates the average body weight (kg), and AT indicates the average total time (d). RfDingestion denotes the chronic oral reference dose (mg/kg/d). UF represents a unit transfer factor, which is ×10−6 for soil and sediment and ×10−3 for water. Ci indicates the metal concentrations in the target media or land use (mg/kg for soil and sediment and μg/L for water).

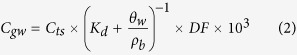

The metal concentrations in groundwater Cgw (μg/L) were calculated using a leaching equation and a dilution factor (DF) (Eq. 2)7:

|

where Cts (mg/kg) indicates the metal concentrations in the total soil profile (0–100 cm), Kd represents the soil-water partition coefficient (L/kg), θw represents the water-filled soil porosity (Lwater/Lsoil) and ρb is the dry soil bulk density (g/cm3).

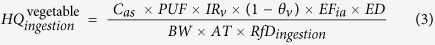

The risks arising from intake of heavy metals from vegetables planted in soil can be written as Eq. (3)14:

|

where Cas (mg/kg) indicates the metal concentrations in the agricultural soils (0–20 cm), PUF (unit-less) represents the plant uptake factor, IRv indicates the vegetable ingestion rate (kg/d), and θv (unit-less) is the vegetable water content.

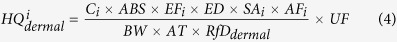

For dermal contact with soil, sediment and water, the health risk model is written as Eqs (4) and (5)7,22:

For soil and sediment

|

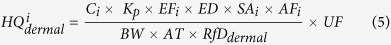

For water

|

where ABS (unit-less) represents the dermal absorption factor for soil and sediment. Kp (cm/h) represents the dermal permeability constant for heavy metals in water. SAi (m2) represents the skin surface area available for exposure in outdoor activities or in swimming. AFi (mg/cm2) represents the soil-to-skin adherence factor for farmers and adults. RfDdermal (mg/kg/d) is the chronic reference dose through dermal contact and UF represents a unit transfer factor (×10−6).

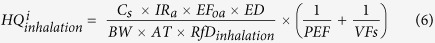

For inhalation routes, the health risk model for risks posed by inhalation of soil particles and vapors is Eq. (6)7,22.

|

where, IRa (m3/d) is the air inhalation rate, RfDinhalation (mg/kg/d) is the chronic inhalation reference dose, PEF (m3/kg) indicates the particulate emission factor and VF is the volatilization factor, which in this study was relevant only for elemental Hg (32,376.4 m3/kg)10.

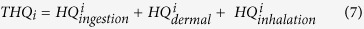

The total hazard quotient (THQ) is the sum of individual HQs for each media or land use, i, and is given by Eq. (7):

|

in which  is calculated only for heavy metals in surface soils. Values of HQ and THQ greater than 1 indicate potential health risks while those less than 1 suggest acceptable risks.

is calculated only for heavy metals in surface soils. Values of HQ and THQ greater than 1 indicate potential health risks while those less than 1 suggest acceptable risks.

Models parameters

Parameters for exposure frequency and duration, metal concentrations, and reference toxic dose are necessary to apply RPRA. The mean and ranges of the exposure parameters in the study area were collected mostly from the Chinese Exposure Factors Handbook23, in which nearly 100,000 questionnaires and surveys in China were compiled to obtain site-specific exposure parameters, such as the frequency of swimming, ingestion rate of water, air and vegetables, skin surface area and average body weight. The frequencies of indoor and outdoor activities were set to 350 d/yr and 225 d/yr, respectively23,24. The mean and ranges of PUF, θv, θv, ρb, DF, IRsd and AFsd were taken from published sources14,19,25,26,27. Other exposure parameters and chronic reference toxic doses (RfD) were taken from USEPA documents6,22,24. The values and distributions of the model parameters used in the current study are summarized in the Supplementary information (Tables S1 and S2). Parameters on heavy metal concentrations and soil pH were measured in field investigations.

Field data collection

Fifty-one surface soil samples (0–20 cm), 6 soil profiles (0–100 cm), 10 surface water samples and 10 river sediment samples were collected along the Shunde Waterway to obtain the mean and ranges of heavy metal concentrations in the study area for different media and land uses. The distribution of sampling sites is shown in Fig. S1. The sampling sites of surface soils can be classified into four categories according to their land use types, including riverbank vegetable plots (RVS, n = 7), riverbank green spaces (RGS, n = 13), private vegetable plots (PVS, n = 11) and public green spaces (PGS, n = 20). The RVS and RGS sites are close to the river while PVS and PGS sites are located further away from the riverbank, but still within 200 m to 2000 m from the river. Each surface soil sample was the composite of five subsamples collected within a 100 m2 area at each sampling site. The soil profiles were randomly sampled from vegetable plots, two of which were located at the riverbank and four were away from the riverbank. Each soil profile sample was the composite of five subsamples, each taken at 20-cm increments from the 100-cm deep profile. Water and sediment samples were randomly collected at 10 riverbank sites (near to the RVS and RGS sites). The concentrations of As, Hg, Cd, Zn, Pb, Cu, Cr and Ni in the samples were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectroscopy and inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry after acid digestion28.

Monte Carlo simulation

Monte Carlo simulations were conducted using Crystal Ball 11.1. Denver, USA. For each exposure parameter or metal concentration, the trial values were generated according to their mean value and data range. The statistical distributions for the parameters were primarily set to lognormal distributions, but some others were triangular distributions (Table S1). The dependences of parameters, including the correlations between BW and SA as well as between PUF and Kd, were assumed during the generation of trial values. To obtain robust results, each Monte Carlo simulation was set to 10,000 iterations for each of the parameters. Then the health risks were calculated by using the generated 10,000 parallel groups of the model parameters in Equations (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6).

Results and Discussion

Heavy metal concentrations

The concentrations of heavy metals in the water, sediments and soils from different land uses along the Shunde Waterway are summarized in Table 1. The concentrations of As, Cd, Zn, Pb, and Cu in the riverbank soils of RVS and RGS were significantly higher than those in the soils of PVS and PGS, respectively, and were higher than background values (Table 1) suggesting external inputs of these metals from anthropogenic activities. The sediments had concentrations of the heavy metals that were similar to the riverbank soils (Table 1). The riverbank soils receive deposits of suspended particulates from the river; these deposits provide nutrition for the growth of vegetables and ornamental vegetation. The anthropogenic As, Cd, Zn, Pb and Cu in the riverbank soils were most likely released from industrial facilities or villages in the upstream portion of the watershed and then transported downstream by water flow before being deposited on the riverbank. Rapid urbanization has caused the prosperity of the manufacturing industry in Shunde County, such as plastic materials production, furniture production, small appliances manufacturing, and textile and garment production29. The scattered and small manufacturing plants without strict supervision may releases heavy metals into the water network.

Table 1. Heavy metal concentrations in water, sediments and soil for different land uses along the Shunde Waterway.

| Land use and media | As | Hg | Cd | Zn | Pb | Cu | Cr | Ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soils | Mean ± Std. Deviation [Minimum, Maximum] (mg/kg) | |||||||

| Riverbank vegetable plot (RVS) | 72.3 ± 26.8 | 0.39 ± 0.12 | 2.25 ± 1.13 | 358.6 ± 249.6 | 100.3 ± 26.1 | 61.7 ± 20.4 | 71.5 ± 4.3 | 27.5 ± 5.2 |

| [34.7, 106.3] | [0.25, 0.59] | [1.02, 4.01] | [170.2, 907.7] | [59.0, 125.5] | [39.1, 99.6] | [66.7, 77.4] | [21.4, 36.2] | |

| Riverbank green space (RGS) (0–20 cm) | 42.5 ± 34.2 | 0.29 ± 0.10 | 1.02 ± 0.77 | 262.6 ± 354.9 | 80.6 ± 84.3 | 37.8 ± 21.6 | 66.8 ± 9.8 | 22.1 ± 5.0 |

| [14.9, 133.4] | [0.12, 0.45] | [0.28, 2.44] | [85.1, 1408.3] | [28.1, 324.7] | [10.4, 91.7] | [51.6, 87.4] | [14.6, 32.6] | |

| Private vegetable plot (PVS) (0–20 cm) | 17.5 ± 3.6 | 0.40 ± 0.41 | 0.55 ± 0.41 | 124.5 ± 59.3 | 36.8 ± 16.7 | 32.5 ± 17.8 | 68.6 ± 16.1 | 26.5 ± 10.8 |

| [12.6, 25.5] | [0.12, 1.43] | [0.12, 1.68] | [64.3, 289.1] | [21.1, 76.2] | [8.4, 66.3] | [42.1, 100.9] | [7.4, 42.8] | |

| Public green space (PGS) (0–20 cm) | 18.5 ± 7.6 | 0.24 ± 0.16 | 0.44 ± 0.22 | 111.6 ± 36.1 | 31.4 ± 12.0 | 18.8 ± 9.6 | 61.8 ± 10.8 | 19.2 ± 7.9 |

| [11.5, 47.0] | [0.03, 0.66] | [0.21, 1.16] | [59.1, 212.7] | [11.9, 56.0] | [5.1, 40.6] | [46.1, 78.7] | [3.0, 29.9] | |

| Total Soils (0–100 cm) | 27.8 ± 20.5 | 0.41 ± 0.24 | 1.29 ± 1.02 | 181.8 ± 158.0 | 52.5 ± 35.8 | 49.2 ± 28.1 | 73.3 ± 14.6 | 31.8 ± 7.3 |

| [11.6, 62.7] | [0.17, 0.74] | [0.43, 2.97] | [85.9, 501.5] | [26.9, 123.7] | [26.5, 103.9] | [52.0, 96.5] | [21.2, 41.0] | |

| River | ||||||||

| surface sediments | 47.8 ± 13.3 | 0.20 ± 0.12 | 1.76 ± 0.45 | 311.0 ± 118.1 | 93.3 ± 44.7 | 93.5 ± 58.4 | 106.0 ± 78.5 | 29.8 ± 8.0 |

| [22.7, 66.6] | [0.06, 0.51] | [0.65, 2.19] | [136.8, 481.8] | [29.8, 163.7] | [40.2, 236.0] | [54.2, 321.6] | [17.6, 39.8] | |

| Mean ± Std. Deviation [Minimum, Maximum] (μg/L) | ||||||||

| surface water | 3.2 ± 1.1 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.07 | 12.6 ± 4.0 | 2.3 ± 2.5 | 3.8 ± 2.2 | 2.4 ± 4.3 | 2.3 ± 2.0 |

| [2.2, 5.4] | [0.01, 0.03] | [0.03, 0.25] | [5.9, 19.4] | [0.7, 9.0] | [2.0, 8.0] | [0.5, 14.6] | [1.2, 7.6] | |

| Soil backgrounds | Heavy metal Background values in soil (mg/kg)28 | |||||||

| 16.2 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 109.6 | 50.1 | 43.8 | 62.0 | 32.6 | |

On the contrary, the soils of PVS and PGS, which were located away from the river, received heavy metals mainly from atmospheric deposition. These soils have slightly higher concentrations of As, Hg, Cd and Zn than the background values (Table 1). Cai, Xu30 reported that the Cd and As found in Shunde County were mainly related to industrial and agronomic practices, while Hg was released from coal burning, industrial fumes and traffic emissions. Atmospheric deposition is the major input pathway of Hg in the soils and leads to the small differences in Hg concentrations between the riverbank soils and other soils. The concentrations of Pb, Cu and Ni in the soils of PVS and PGS were slightly lower than the reported background values (Table 1). Because the soil backgrounds of heavy metals are spatially varied and their measurements can be affected by the choice of sampling sites and analytical methods31.

Compared with previous studies, the soil concentrations of As, Hg, Cd, Zn and Pb in the riverbank of the Shunde Waterway are considerably higher than that in the water source protection areas of Shanghai, Beijing, and the Pearl River delta17,32,33. The high concentrations of heavy metals in the riverbank soil and sediments along the waterway may threaten the health of local residents during outdoor recreation activities and consumption of vegetables planted on the riverbank. Therefore, identifying the risk levels of exposure to heavy metals in the study area is imperative.

Risks of different media and land uses

Table 2 summarizes the mean and 95th percentile values of HQs resulting from exposure to the heavy metals in different media and land uses. The 95th percentiles of HQs were widely used to provide conservative and protective risk estimates19. The 95th percentiles of THQs in the study area follows the gradient of RVS (3.57) > groundwater (1.46) > PVS (1.20) > surface water (0.84) > RGS (0.41) > river sediments (0.18) > PGS (0.17); the first three of these THQ values exceeds 1, suggesting potential health risks. The highest THQ was found in the RVS soils where the highest metal concentrations were measured. This finding suggests that the vegetable plots along the Shunde Waterway are threatening the health of local residents, especially farmers. In addition, the fertilization in riverbank vegetable plots may directly pollute the drinking water sources. Therefore, cultivation of edible crops on the riverbank soils should be discouraged.

Table 2. Hazard quotients of heavy metals in different media and land uses.

| Land use and media |

HQingestion |

|

HQinhalation |

|

THQ |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95th percentile | CV | Mean | 95th percentile | CV | Mean | 95th percentile | CV | Mean | 95th percentile | CV | Mean | 95th percentile | CV | |

| RVS | 0.207 | 0.392 | 47.5% | 0.110 | 0.219 | 54.9% | 0.024 | 0.038 | 35.8% | 1.338 | 3.162 | 81.1% | 1.678 | 3.567 | 66.3% |

| RGS | 0.131 | 0.293 | 71.1% | 0.046 | 0.114 | 81.6% | 0.018 | 0.031 | 38.7% | 0.195 | 0.408 | 62.2% | |||

| PVS | 0.066 | 0.114 | 39.0% | 0.032 | 0.059 | 45.5% | 0.024 | 0.064 | 106.3% | 0.476 | 1.061 | 67.6% | 0.598 | 1.195 | 54.8% |

| PGS | 0.065 | 0.119 | 45.7% | 0.023 | 0.045 | 56.6% | 0.015 | 0.033 | 68.3% | 0.102 | 0.169 | 37.0% | |||

| Groundwater | 0.570 | 1.457 | 94.8% | 0.570 | 1.457 | 94.8% | |||||||||

| Surface water | 0.446 | 0.839 | 54.3% | 0.001 | 0.002 | 83.0% | 0.447 | 0.840 | 54.2% | ||||||

| River sediments | 0.018 | 0.039 | 64.7% | 0.053 | 0.143 | 87.7% | 0.070 | 0.176 | 76.5% | ||||||

THQs are mainly dependent on the exposure routes and exposure frequencies that vary with media and land uses. The vegetable plot soils (RVS and PVS) had significantly higher THQs than the green space soils (RGS and PGS) (Table 2). The hazard quotients for the exposure route of vegetable ingestion contributed most to the THQs of RVS and PVS. Therefore, even though the riverbank soils of RGS had relatively high metal concentrations, they had low THQ due to the absence of risk from vegetable ingestion.

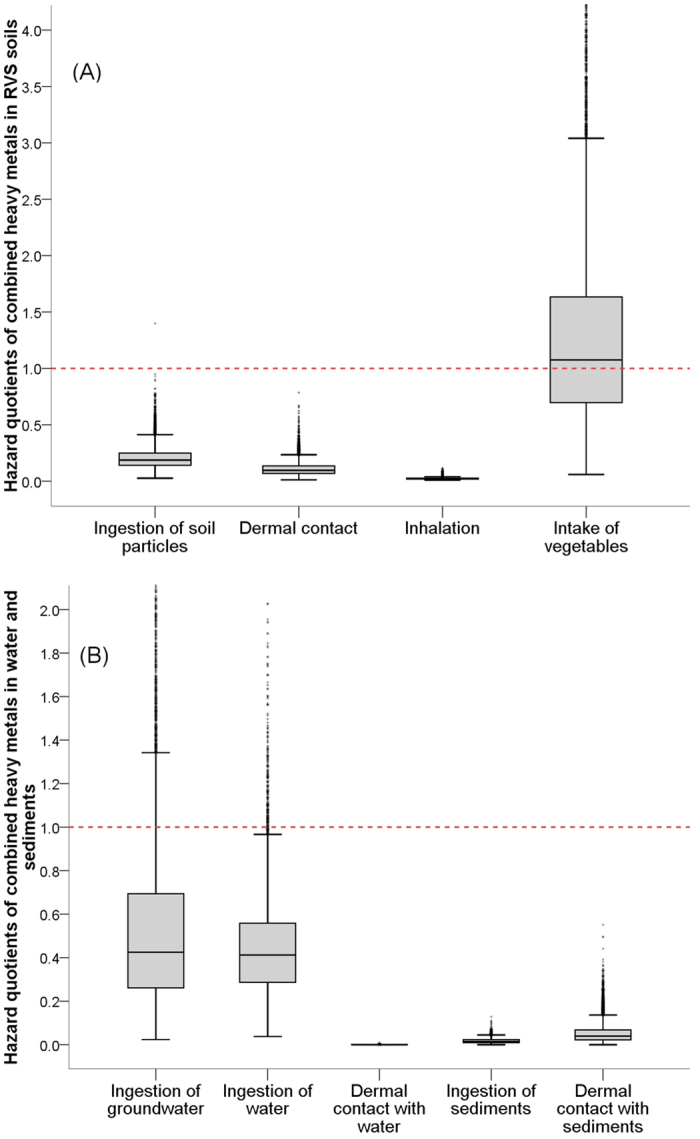

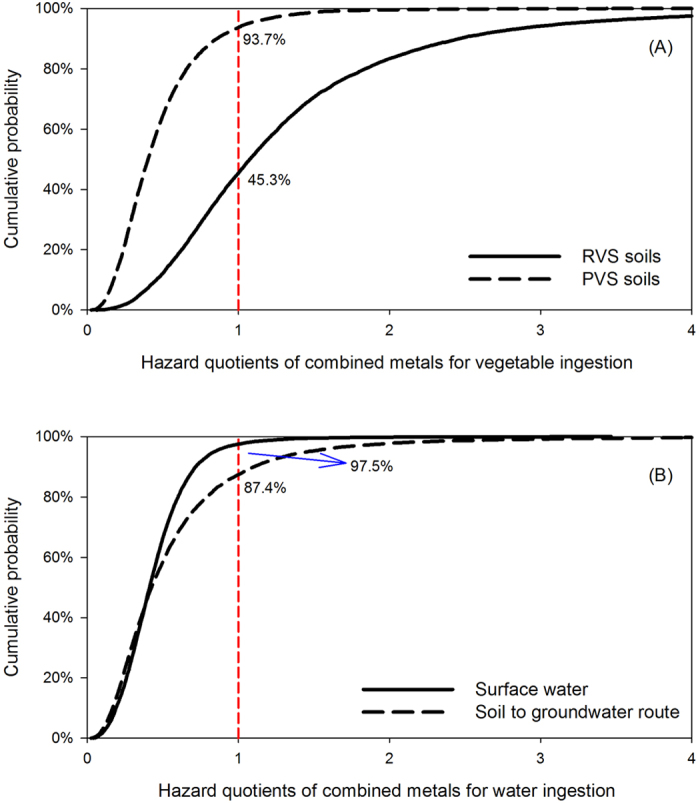

Figure 2 presents the box plots of the HQs in terms of the exposure routes, from which the major causes of the risks can be identified, namely vegetable ingestion, groundwater ingestion and water ingestion. Considering the individual differences and spatial variations, the HQingestion of vegetables in the RVS and PVS soils have 54.7% and 6.3% probabilities to exceed the threshold value of 1, respectively (Fig. 3A). The ingestion of groundwater and surface water have 12.6% and 2.5% chances, respectively, to exceed the safe level of heavy metal intake (Fig. 3B). The HQingestion for groundwater was calculated based on the leaching potential of heavy metals in vegetable soils according to Eq. (2). The estimated heavy metal concentrations in the groundwater were close to the measured concentrations in surface water. Therefore, the mean values of HQingestion between the groundwater and surface water were similar. Due to the large variances of Kd and DF (Supplementary information), the HQingestion of groundwater had a considerably larger coefficient of variation and higher 95th percentile value than that of surface water (Table 2). Overall, metal uptake by vegetables and metal leaching to groundwater are the two important transfer routes of heavy metals in soils and may threaten human health. To reduce these health risks, measures should be taken such as converting vegetable fields to green space, or applying soil amendments that will immobilize heavy metals and prevent crop uptake.

Figure 2. Box plots of hazard quotients for different exposure routes along the Shunde Waterway (The band inside the box represent the 50th percentile and the whiskers indicates 1.5 IQR from the 25th and 75th percentile).

Figure 3. Cumulative probability of hazard quotients for vegetable ingestion and groundwater ingestion.

(RVS = riverbank vegetable plot soils; PVS = private vegetable plot soils 200–2000 m from the riverbank).

Figure 2B illustrates that low HQs arise from ingestion of sediment and from dermal contact with water and sediment. These HQs are calculated based on the swimming frequencies of local residents. Neither HQingestion,  and HQinhalation in soil under the four land uses had a 95th percentile value that exceeded 1 (Table 2). These results suggest that the outdoor activities such as recreation, farming and swimming along the Shunde Waterway are theoretically safe for human health.

and HQinhalation in soil under the four land uses had a 95th percentile value that exceeded 1 (Table 2). These results suggest that the outdoor activities such as recreation, farming and swimming along the Shunde Waterway are theoretically safe for human health.

Risks of heavy metal species

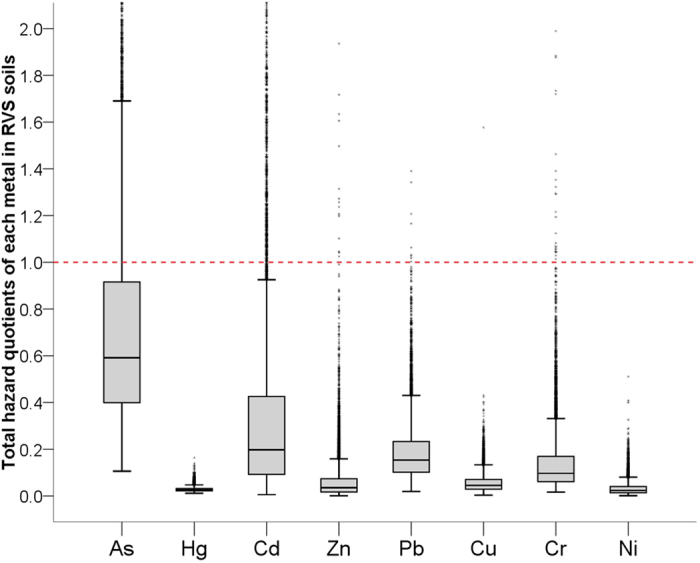

Knowledge about the risk contributions of individual metal species to the total risks is essential for identifying the priority pollutants for remediation and emission control. The HQs varied dramatically with heavy metal species due to differences in toxicity, concentrations and mobility. Figure 4 shows that the 95th percentile HQs follow the gradients of As (1.88) > Cd (1.30) > Pb (0.44) > Cr (0.39) > Zn (0.21) > Cu (0.13) > Ni (0.09) > Hg (0.05) in RVS soils. Similar risk gradients of the metal species were found in other land uses suggesting that As and Cd should be primarily considered for pollution management in the study area.

Figure 4. Box plots of total hazard quotients for metal species in RVS soils (riverbank vegetable plots).

For different exposure routes, the eight heavy metals showed varying contributions to the HQs (Table 3). For instance, As contributed 80% and 92% of HQingestion and HQdermal for RVS sites respectively, and 61% and 77% of that for PVS sites respectively. More than 98% of HQinhalation are caused by the volatilization of Hg; the contribution of other metal species is negligible. In RVS soils, As and Cd contributed 38.4% and 28.7% to HQingestion of vegetables respectively, followed by Pb and Cr. Arsenic also contributed more than 80% of HQingestion for groundwater and surface water. The results suggest that As and Cd were the primary risk sources in the high-risk exposure routes, including groundwater ingestion and vegetable ingestion. Therefore reducing As and Cd emissions or immobilizing them in the soils would be effective ways to control the health risk levels arising from these two contaminants.

Table 3. Contributions of heavy metal species to hazard quotients of the major exposure routes.

| As | Hg | Cd | Zn | Pb | Cu | Cr | Ni | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RVS | ||||||||

| HQingestion | 80.01% | 0.43% | 0.75% | 0.39% | 9.53% | 0.51% | 7.91% | 0.46% |

|

91.67% | 0.09% | 1.15% | 0.03% | 0.96% | 0.03% | 6.04% | 0.03% |

| HQinhalation | 0.12% | 98.63% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.01% | 0.00% | 1.23% | 0.00% |

|

38.41% | 0.30% | 28.70% | 4.81% | 12.50% | 4.11% | 8.82% | 2.35% |

| PVS | ||||||||

| HQingestion | 60.68% | 1.39% | 0.57% | 0.43% | 10.98% | 0.84% | 23.73% | 1.38% |

|

77.17% | 0.34% | 0.97% | 0.04% | 1.23% | 0.05% | 20.12% | 0.09% |

| HQinhalation | 0.03% | 98.77% | 0.00% | 0.05% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 1.15% | 0.00% |

|

26.09% | 0.86% | 19.25% | 4.69% | 12.85% | 6.08% | 23.78% | 6.40% |

| Groundwater | ||||||||

| HQingestion | 84.49% | 6.26% | 2.30% | 2.54% | 0.22% | 0.24% | 0.00% | 3.95% |

| Surface water | ||||||||

| HQingestion | 84.86% | 0.53% | 0.80% | 0.34% | 5.31% | 0.76% | 6.50% | 0.92% |

Sensitivity analysis

RPRA was used to estimate the probabilities of health risks based on the probabilities of input parameters. Consequently, the HQs showed large coefficients of variation ranging from 36% to 95% (Table 2). The variances of HQs were mainly dependent on the uncertainty and variability of the metal concentrations and exposure parameters. Correlation analysis was used to rank the importance of the input parameters on THQs for different media and land uses. Table 4 shows that PUF, IRv and θv were the key factors affecting the health risks associated with vegetable plots, while As concentrations in soil, IRs and AFsa were important determinants of the health risks associated with green space. The risks of groundwater ingestion were highly related to soil As concentrations, IRw and DF. Meanwhile, the THQWater was affected mostly by IRw and by the As and Cr concentrations in the water. These results indicate that in estimating health risks, the variations of exposure parameters and changes of metal mobility in soil may be more important than the metal concentrations. Traditional health risk assessment that adopts default values for exposure parameters is challenged to reflect the authentic levels of risks. RPRA, which includes the uncertainty and variability of exposure parameters in the risk calculations, is a powerful technique by which to identify the exposure routes of high risks and the key factors affecting the risk levels.

Table 4. Sensitivity parameters for total hazard quotients of heavy metals in different media and land uses.

| RANK | THQRVS | THQRGS | THQPVS | THQPGS | THQGroundwater | THQWater | THQSediments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PUFCd (0.475**) |

(0.864**) (0.864**) |

IRv (0.490**) |

(0.653**) (0.653**) |

(0.647**) (0.647**) |

IRw (0.737**) | EFsw (0.683**) |

| 2 | PUFAs (0.429**) | IRs (0.375**) | PUFAs (0.357**) | IRs (0.610**) | IRw (0.425**) |

(0.548**) (0.548**) |

AFsd (0.(0.551**) |

| 3 | IRv (0.410**) | AFsa (0.148**) | PUFCr (0.353**) | AFsa (0.266**) | DF (0.352**) |

(0.259**) (0.259**) |

(0.267**) (0.267**) |

| 4 | θv (−0.257**) |

(0.141**) (0.141**) |

PUFCd (0.323**) |

(0.260**) (0.260**) |

KdAs (−0.243**) |

(0.132**) (0.132**) |

(0.102**) (0.102**) |

| 5 |

(0.256**) (0.256**) |

BW (−0.078**) | θv (−0.315**) | BW (−0.144**) | BW (−0.055**) | BW (−0.131**) | IRsd (0.084**) |

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Conclusions

This research conducted regional-scale probabilistic risk assessment to estimate the health risks of exposure to heavy metals in water, sediments and soils for different land uses along the Shunde Waterway, a drinking water supply area in China. The risk receptors were set to the most sensitive population according to each media and land use. The Monte Carlo simulation was adopted to characterize the uncertainty and variability of exposure parameters and metal concentrations.

The 95th percentile total hazard quotients for vegetable plots on the riverbank and further away (200–2,000 m) were 3.57 and 1.20, respectively, suggesting that these land uses pose potential threats to human health. Uptake by vegetables and leaching to groundwater are the two major transfer routes of heavy metals in soils that may threaten human health. The results indicated that cultivation on the flooded riverbank should be discouraged. Outdoor activities such as recreation, farming and swimming along the Shunde Waterway are theoretically safe. The metals As and Cd in soils are major risk sources and pollutants that should be given priority for management. The presence of high-risk exposure routes and variations in sensitive exposure parameters have more influence on health risk estimates than do heavy metal concentrations.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Peng, C. et al. Regional probabilistic risk assessment of heavy metals in different environmental media and land uses: An urbanization-affected drinking water supply area. Sci. Rep. 6, 37084; doi: 10.1038/srep37084 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41401588, 31470703) and National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. 2014ZX07201-011-005).

Footnotes

Author Contributions The author Dr. Chi Peng wrote the main manuscript text, developed the risk assessment framework and prepared the tables figures. Dr. Yimin Cai provided the heavy metal data and processed preliminary data analysis. Prof. Tieyu Wang and Prof. Rongbo Xiao provided many suggestions on the sampling strategy and helped the data collection. Prof. Weiping Chen helped the manuscript writing and organization. In addition, Prof. Weiping Chen provided financial support for this study.

References

- Chen H. et al. Contamination features and health risk of soil heavy metals in China. Sci Total Environ. 512, 143–153 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng C. et al. Assessing the combined risks of PAHs and metals in urban soils by urbanization indicators. Environ Pollut. 178, 426–432 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defo C. et al. Assessment of heavy metals in soils and groundwater in an urban watershed of Yaounde (Cameroon-West Africa). Environ Monit Assess. 187, 77 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimann C. & Caritat P. D. Intrinsic Flaws of Element Enrichment Factors (EFs) in Environmental Geochemistry. Environ Sci Technol. 34, 5084–5091 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Kentel E. et al. Challenges in Development and Implementation of Health-Risk-Based Soil Quality Guidelines: Turkey’s Experience. Risk Anal. 31, 657–667 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund. Volume I: Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part A). United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C., EPA/540/1-89/002 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. Soil Screening Guidance: User’s Guide (Second Edition). United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC 20460 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Poggio L. et al. Introducing a method of human health risk evaluation for planning and soil quality management of heavy metal-polluted soils–An example from Grugliasco (Italy). Landscape Urban Plan. 8, 64–72 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Peng C. et al. Distribution and risks of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in suburban and rural soils of Beijing with various land uses. Environ Monit Assess. 188, 1–12 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Miguel E. et al. Risk-based evaluation of the exposure of children to trace elements in playgrounds in Madrid (Spain). Chemosphere 66, 505–513 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipter E. et al. Site-specific risk assessment in contaminated vegetable gardens. Chemosphere 71, 1301–1307 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng C. et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban soils of Beijing: Status, sources, distribution and potential risk. Environ Pollut. 159, 802–808 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini Koupaie E. & Eskicioglu C. Health risk assessment of heavy metals through the consumption of food crops fertilized by biosolids: A probabilistic-based analysis. J Hazard Mater. 300, 855–865 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander P., Bergbäck B. & Öberg T. Uncertain Numbers and Uncertainty in the Selection of Input Distributions—Consequences for a Probabilistic Risk Assessment of Contaminated Land. Risk Anal. 26, 1363–1375 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. Risk assessment guidance for superfund: Volume III. Part A: Process for conducting probabilistic risk assessment. United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C., EPA 540-R-02-002 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Lester R. R., Green L. C. & Linkov I. Site-Specific Applications of Probabilistic Health Risk Assessment: Review of the Literature Since 2000. Risk Anal. 27, 635–658 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y. et al. Impacts of urbanization on the distribution of heavy metals in soils along the Huangpu River, the drinking water source for Shanghai. Environ Sci Pollut R. 23, 5222–5231 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poggio L. & Vrščaj B. A GIS-based human health risk assessment for urban green space planning—An example from Grugliasco (Italy). Sci Total Environ. 407, 5961–5970 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipsson M. et al. Exposure to contaminated sediments during recreational activities at a public bathing place. J Hazard Mater. 171, 200–207 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Lang Y. & Li G. Cancer risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the soils from Jiaozhou Bay wetland. Chemosphere 112, 289–295 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabukdhara M. & Nema A. K. Heavy metals assessment in urban soil around industrial clusters in Ghaziabad, India: Probabilistic health risk approach. Ecotox Environ Safe. 87, 57–64 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. Supplemental Guidance for Developing Soil Screening Levels for Superfund Sites. United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C., OSWER 9355.4-24 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- MEP. The Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China, Chinese Exposure Factors Handbook. China environmental press (2013). [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. Exposure Factors Handbook: 2011 edition. United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C., EPA/600/R-09/052F (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z. The study of fluorquinolones antibioties in the vegetable of Guangzhou and Dongguan (in Chinese). Thesis, Jinan University (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. et al. Health risk of heavy metals in food crops grown on reclaimed tidal flat soil in the Pearl River Estuary, China. J Hazard Mater. 227–228, 148–154 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. et al. Accumulation of heavy metals in leaf vegetables from agricultural soils and associated potential health risks in the Pearl River Delta, South China. Environ Monit Assess. 186, 1547–1560 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y. et al. Spatial distribution and potential ecological risk assessment of heavy metalts in soils and sediments in Shunde Waterway, Southern China. Environmental Science (in Chinese) 37, 171–178 (2016). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FSDPSB. Shunde Statistical Yearbook (in Chinese). Foshan Shunde development planning and statistics bureau (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Cai L. et al. Multivariate and geostatistical analyses of the spatial distribution and source of arsenic and heavy metals in the agricultural soils in Shunde, Southeast China. J Geochem Explor. 148, 189–195 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Peng C. et al. Mass balance-based regression modeling of Cd and Zn accumulation in urban soils of Beijing. J Environ Sci-China. In Press (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W. et al. Watershed-scale assessment of arsenic and metal contamination in the surface soils surrounding Miyun Reservoir, Beijing, China. J Environ Manage. 91, 2599–2607 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y. et al. Assessing heavy metal pollution in the surface soils of a region that had undergone three decades of intense industrialization and urbanization. Environ Sci Pollut R. 20, 6150–6159 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.