Abstract

A 39-year-old man presented to our hospital with a four-week history of headache and a two-week history of low-grade fever. Chest X-rays showed a tumor of approximately 50 mm in size in the right lower field. A histopathological examination of a transbronchial lung biopsy specimen from the right S9/10 revealed numerous fungal elements that appeared as encapsulated yeast with clear halos. Gadolinium-enhanced brain magnetic resonance images showed multiple cerebral nodules. Cryptococcus gattii (Genotype VGIIa) was isolated from the bronchial lavage and cerebrospinal fluid specimens. The patient was an immunocompetent Japanese man who had not recently traveled to a C. gattii-endemic area.

Keywords: Cryptococcus gattii, Japanese, immunocompetent, oversea travel, cryptococomma

Introduction

Cryptococcus infection is mainly caused by Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii (1-4). C. neoformans infection is a major worldwide cryptococcosis that primarily affects immunocompromised hosts (2-5). C. gattii has traditionally been considered to be exclusive to tropical and subtropical climates, where it infects both healthy and immunocompromised patients (2,5).

Recently, a reported outbreak of C. gattii in the temperate climate of the Pacific Northwest of North America has challenged our understanding of this disease (1-10). Harris et al. reported high morbidity and mortality among patients with C. gattii infections in the United States, with over 90% of patients requiring hospitalization and a case fatality rate of over 30% (6). Among the four C. gattii genotypes (VGI to VGIV, each containing subtypes), VGIIa isolates predominate in the northwest of North America (3,4,6,7). In Japan, where C gattii infections are recognized as an imported infectious disease, sporadic cases have been documented since 2001 (5,8,11-14).

We herein report a case of cerebral and pulmonary cryptococcosis caused by C. gattii genotype VGIIa in an immunocompetent Japanese man who had not recently traveled overseas. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of C. gattii VGIIa infection in an otherwise healthy Japanese patient, and the second reported case in Japan. The patient provided written informed consent for us to share these findings.

Case Report

In 2015, a 39-year-old man presented to our hospital with a four-week history of headache and a two-week history of low-grade fever. He was previously healthy and had not been taking any medications. He was a current smoker (15 pack-years) and occasionally consumed alcohol. Although he had traveled to Hawaii in 2005, Dalian in China in 2008, and Hong Kong in 2010, he had no other history of overseas travel. He had been working as electrical engineering technician, and had not been exposed to any imported timber or animals.

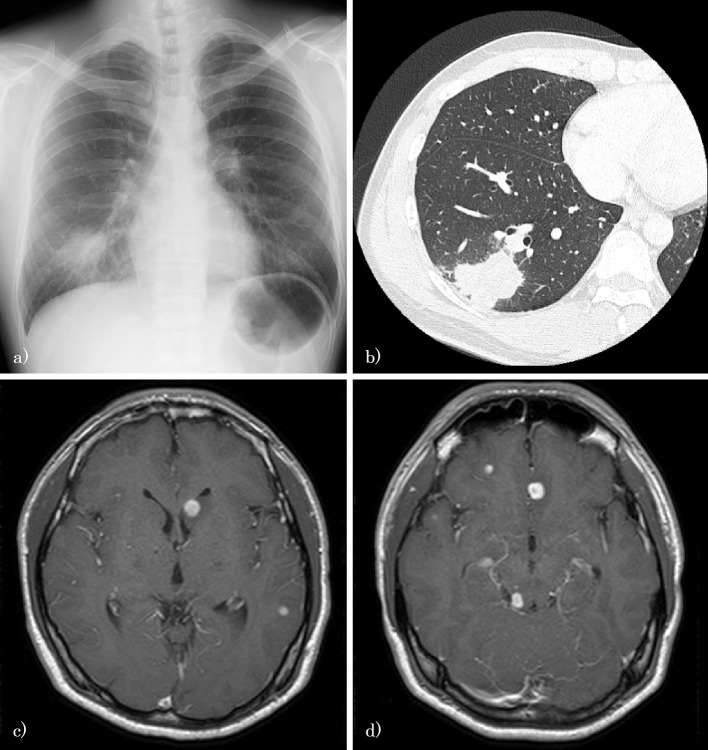

A physical examination revealed mild neck stiffness and a low-grade fever of 37.2°C. A chest X-ray showed a tumor of approximately 50 mm in size in the right lower field, and a chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed a 48×35 mm tumor with spiculation and notching on the right S9/10 (Fig. 1a and b). A gadolinium-enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed multiple brain tumors with ring enhancement (Fig. 1c and d). The patient's white blood cell (WBC) and platelet counts were high [WBC, 12,900/mm2 (normal range 4,000-9,000/mm2); platelet, 444,000/mm2 (normal range 150,000-370,000/mm2)], and the blood chemistry findings were normal, including the levels of glucose, hemoglobin A1c, tumor markers, immunoglobulin, and autoimmune antibodies.

Figure 1.

a) A chest X-ray film showing a tumor of approximately 50 mm in size in the right lower field. b) A chest CT scan showing a 48×35 mm tumor with spiculation and notching on the right S9/10. c, d) A gadolinium-enhanced brain MRI scan showing multiple brain tumors with ring enhancement.

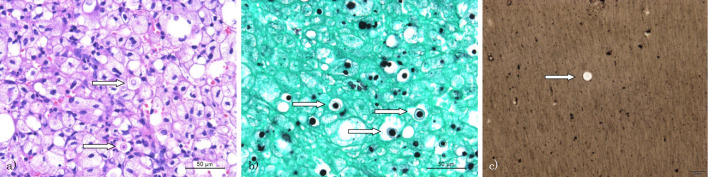

Based on the chest CT and brain MRI findings, we suspected lung cancer with multiple brain metastases, and performed a bronchoscopic examination. A histopathological examination of the transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) specimen from the right S9/10 revealed numerous fungal elements that appeared as encapsulated yeast with clear halos (Fig. 2a). The yeast was observed after periodic acid-Schiff and Grocott methenamine silver staining (Fig. 2b). A lumbar puncture had an elevated opening pressure (33 cm H2O), and the cerebrospinal fluid sample contained 264/mm2 cells, 84.1% of which were lymphocytes. India ink staining of the patients' cerebrospinal fluid revealed encapsulated Cryptococci as a halo against a black background (Fig. 2c). Additional serological tests revealed that the patient was negative for HIV-1/2 antibodies and positive for cryptococcal antigen; the CD4+ lymphocyte level in the patient's peripheral blood was normal. The cryptococcal strain isolated from the bronchial lavage and cerebrospinal fluid was identified as C. gattii genotype VGIIa using multi-locus sequence typing (MLST), based on a DNA sequence analysis of a set of polymorphic loci (8,15).

Figure 2.

The transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) specimens from the right S9/10 and India ink staining of cerebrospinal fluid. a) Numerous fungal elements are visible as encapsulated yeast with clear halos (Hematoxylin and Eosin staining, TBLB). b) Yeast (Cryptococcus) is visible after staining with periodic acid-Schiff and Grocott methenamine silver stains (TBLB). c) Encapsulated Cryptococci is visible as a halo against a black background (India ink staining, cerebrospinal fluid).

As a result, the patient was diagnosed with pulmonary and cerebral cryptococcosis induced by C. gattii genotype VGIIa infection. He was treated with liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg/day for more than 8 weeks), flucytosine (6,000 mg/body for more than 8 weeks). Percutaneous lumbar drainage was performed more than 15 times within the first month to manage his increased intracranial pressure. His subjective symptoms and radiological abnormalities improved gradually. After induction therapy, we are planning consolidation therapy and maintenance therapy with oral fluconazole.

Discussion

We herein describe a rare case of C. gattii infection that was diagnosed by the analysis of bronchoscopic and cerebrospinal fluid specimens. Both specimen cultures were positive for a cryptococcal strain, and MLST based on a DNA sequence analysis of a set of polymorphic loci was useful for identifying the isolates as C. gattii genotype VGIIa. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous reports of C. gattii VGIIa infection in a healthy Japanese individual without a history of recent travel to an endemic area.

C. gattii is a basidiomycetous yeast that is present in the environment, namely in eucalyptus trees and soil and within animal hosts such as koalas (1). Although C. gattii is recognized as an endemic pathogen in Australia, there have also been outbreaks of C. gattii in the Pacific Northwest of North America since the 1990s (1-3,7-10). C. gattii has been isolated from more than 50 tree species and a broad range of animals, including dogs and cats (1,8,16). The most common sites of C. gattii infection, which has an incubation period of 2 to 11 months, are the central nervous system (CNS) and lungs (1). Although the risk factors for C. gattii infection are not well defined, several risk factors, such as a history of smoking and host genetic factors, have been reported (1). Headache, vomiting, and neck stiffness are the common neurological manifestations, and cough, dyspnea, chest pain and hemoptysis are common symptoms of lung involvement. Systemic features such as chills, fever and weight loss are also common symptoms. Although the clinical features of cryptococcosis caused by C. neoformans and C. gattii are similar, C. gattii is associated with large mass lesions of the lungs and brain and tends to be resistant to antifungal drugs (1,6,12,13). C. gattii requires lengthy antifungal treatment and, particularly in infections of the CNS, the aggressive management of increased intracranial pressure along with percutaneous lumbar drainage (1,2,13,17). Thus, from a clinical point of view, the differential diagnosis of C. neoformans and C. gattii is very important. Nonetheless, in Japan, as there is no commercial laboratory test to distinguish between C. neoformans and C. gattii, C. gattii infections may have been misdiagnosed as C. neoformans.

Since 2001, there have been five reported cases of C. gattii infection in Japan (Table). The first reported case was a healthy 71-year-old man who had traveled to Australia for one week (genotype: unknown) (11). The second reported case was a 44-year-old man with untreated diabetes mellitus and no recent history of overseas travel (genotype: VGIIa) (5). The third reported case was a 34-year-old woman who had traveled to Korea and China, who had been treated for uterine cervical cancer one year previously (genotype: VGI) (12). The fourth reported case was an immunocompetent 33-year-old man with no history of overseas travel; however, he had been importing trees and soils from abroad to feed beetles (genotype: unknown) (13). The fifth reported case was a 41-year-old previously healthy man who had traveled to several cities in China (genotype: VGIIb) (8,14). Four of the five patients were in their 30s and 40s. None of the five cases noted the presence of HIV infection and/or immunosuppressive drug use. In addition, brain MRI scans showed cerebral cryptococcomas in all of the reported Japanese cases. The sources of C. gattii infection were suspected to have originated from overseas in four of the five patients. Only one patient was thought to have been infected in Japan. The characteristics of our case, including the patient's age, sex, and underlying disease status, are similar to these reported cases. The present case represents the second report of C. gattii VGIIa infection in a Japanese patient.

Table.

The Reported Cases of C. Gattii Infection in Japan.

| Reference No. | Age | Sex# | Prefecture* | Genotype | Underlying disease (including immunosupressive disease or drug use) | Recent oversea travel or exposure to imported subjects | Suspected location of C. gattii infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 71 | M | Tokyo | Unknown | None | Traveled to Australia | Australia |

| 5 | 44 | M | Tokyo | VGIIa | Diabetes mellitus | None | Japan |

| 12 | 34 | F | Hokkaido | VGI | Uterine cervical cancer (clinical stage I) | Traveled to Korea and China | China or Japan (unknown) |

| 13 | 33 | M | Hyogo | Unknown | None | Imported trees and soils | Foreign countries (unknown) |

| 8, 14 | 41 | M | Shizuoka | VGIIb | None | Traveled to China | China |

| This case | 39 | M | Aichi | VGIIa | None | None | Japan |

*: The location of hospital which the case was reported.

#; M: male, F: female.

Because the patient in the present case had no history of recent overseas travel, the C. gattii infection appears to have originated in Japan. Including our case, two cases are thought to have been infected with C. gattii within Japan, and the cryptococcal strain in both of these cases was genotype VGIIa. This also happens to be the strain that is most commonly isolated in the temperate climate of the Pacific Northwest of North America (5). In the clinical setting of Japanese hospitals, it is very difficult to distinguish C. neoformans and C. gattii in patients who are positive for Cryptococcus spp. infection. Japanese commercial laboratory tests report C. gattii as C. neoformans; thus, the number of C. gattii infections in Japan may have been underestimated. Nationwide investigations on cryptococcosis are necessary to assess the potential spread of C. gattii.

In conclusion, we experienced a case of C. gattii genotype VGIIa infection in a healthy Japanese man without a history of recent overseas travel. Our experience may provide further insight into cryptococcosis. Furthermore, particularly in immunocompetent patients with cryptococcoma, the present case emphasizes the importance of excluding C. gattii infection. Lastly, ecological and environmental investigations are warranted in Japan to better understand the epidemiological aspects of C. gattii infection.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1.Chen SC, Meyer W, Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus gattii infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 27: 980-1024, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center of Disease Control and Prevention Emergence of Cryptococcus gattii--Pacific Northwest, 2004-2010. Am J Transplant 11: 1989-1992, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lockhart SR, Iqbal N, Harris JR, et al. . Cryptococcus gattii in the United States: genotypic diversity of human and veterinary isolates. PLoS One 8: e74737, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, et al. . Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin Infect Dis 50: 291-322, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okamoto K, Hatakeyama S, Itoyama S, et al. . Cryptococcus gattii genotype VGIIa infection in man, Japan, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis 16: 1155-1157, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris JR, Lockhart SR, Debess E, et al. . Cryptococcus gattii in the United States: clinical aspects of infection with an emerging pathogen. Clin Infect Dis 53: 1188-1195, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SC, Slavin MA, Heath CH, et al. . Clinical manifestations of Cryptococcus gattii infection: determinants of neurological sequelae and death. Clin Infect Dis 55: 789-798, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawamura I, Kamei K, Yarita K, et al. . Cryptococcus gattii genotype VGIIb infection in Japan. Med Mycol J 55: E51-E54, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galanis E, Macdougall L, Kidd S, Morshed M. Epidemiology of Cryptococcus gattii, British Columbia, Canada, 1999-2007. Emerg Infect Dis 16: 251-257, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espinel-Ingroff A, Kidd SE. Current trends in the prevalence of Cryptococcus gattii in the United States and Canada. Infect Drug Resist 8: 89-97, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsunemi T, Kamata T, Fumimura Y, et al. . Immunohistochemical diagnosis of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii infection in chronic meningoencephalitis: the first case in Japan. Intern Med 40: 1241-1244, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horiuchi K, Yamada M, Shirai S, et al. . A case of successful treatment of brain and lung cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii. Rinsho Shinkeigaku (Clinical Neurology) 52: 166-171, 2012. (in Japanese, Abstract in English). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inada T, Imamura H, Kawamoto M, et al. . Cryptococcus Neoformans Var. Gattii meningoencephalitis with cryptococcoma in an immunocompetent patient successfully treated by surgical resection. No Shinkei Geka (Neurological Surgery) 42: 123-127, 2014. (in Japanese, Abstract in English). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakashima K, Akamatsu H, Endo M, Kawamura I, Nakajima T, Takahashi T. Endobronchial cryptococcosis induced by Cryptococcus gattii mimicking metastatic lung cancer. Respirol Case Rep 2: 108-110, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer W, Aanensen DM, Boekhout T, et al. . Consensus multi-locus sequence typing scheme for Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. Med Mycol 47: 561-570, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Springer DJ, Chaturvedi V. Projecting global occurrence of Cryptococcus gattii. Emerg Infect Dis 16: 1420, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franco-Paredes C, Womack T, Bohlmeyer T, et al. . Management of Cryptococcus gattii meningoencephalitis. Lancet Infect Dis 15: 348-355, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]