Abstract

Acute acalculous cholecystitis (AAC) is a severe disease seen in critically ill patients, including those with autoimmune diseases. We herein report the case of a 41-year-old female who developed macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) accompanied by a recurrence of Kikuchi disease. Abdominal imaging revealed marked thickening of the gallbladder wall and pericholecystic fluid, typically found in AAC. Treatment with intravenous pulse methylprednisolone induced in a significant improvement in the gallbladder wall, resulting in no need for surgical intervention. We should consider that patients with MAS may therefore sometimes develop AAC and that early immunosuppressive therapy can be effective in AAC cases associated with rheumatic or autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: acute acalculous cholecystitis, macrophage activation syndrome, Kikuchi disease

Introduction

Acute acalculous cholecystitis (AAC) is an acute necroinflammatory disease of the gallbladder without gallstones that is typically seen in critically ill patients (1,2). The pathology includes endothelial injury, gall bladder ischemia, and stasis and these conditions may cause a concentration of bile salts and gallbladder distension, eventually leading to necrosis of the gallbladder tissue (1,2). Marked gallbladder wall thickening (≥3.5 mm) and pericholecystic fluid are the most common imaging features of the disease (2). Approximately 10% of all acute cholecystitis cases are AAC, and the mortality is high in such cases without prompt treatment (1,2). AAC can be related to trauma, surgery, shock, burns, sepsis, total parenteral nutrition, and/or prolonged fasting (2), and it can also be accompanied by autoimmune diseases.

Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is an aggressive and potentially lethal syndrome of uncontrolled immune activation. In MAS, macrophages become activated and overproduce cytokines, thereby causing severe tissue damage and eventually leading to organ failure (3). MAS is thought to be a form of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) associated with a rheumatic disease. There are some reports describing the association of AAC with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and other autoimmune diseases (4-6), but the coexistence of AAC and MAS has so far only rarely been reported. We herein report a case of AAC complicating MAS, occurring in a patient with recurrent histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi disease) and Sjögren syndrome. Rheumatologists should be aware of this possible association and keep in mind the fact that AAC in rheumatic or autoimmune diseases can be successfully treated with early immunosuppressive therapy, although the risk of perforation and the mortality rate is high in AAC.

Case Report

A 41-year-old female was admitted to our hospital because of a high fever with lymphadenopathy that had appeared 4 days before admission. Kikuchi disease had been diagnosed 5 years earlier by a left cervical lymph node biopsy. She had been doing well at her last scheduled visit 10 days before admission. Sjögren syndrome had also been diagnosed 2 years earlier, but she did not meet the criteria for SLE. She had no history of any recent abdominal surgery or prolonged fasting.

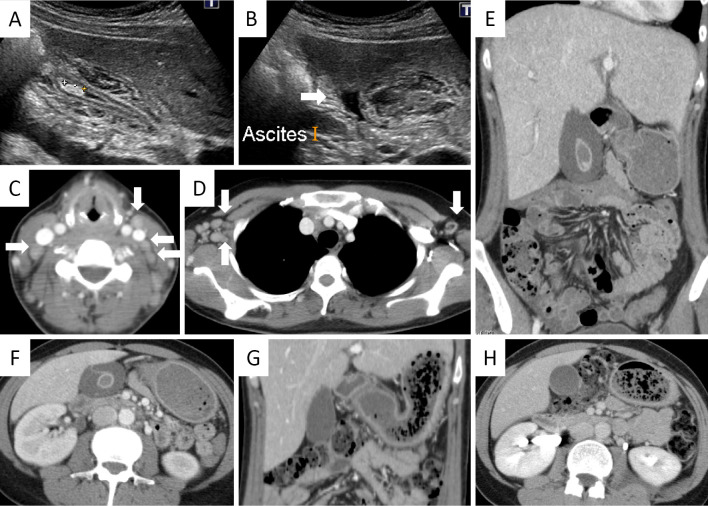

Physical examination revealed a temperature of 38.2℃, cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy with tenderness, but no tenderness in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. The blood pressure was 124/83 mmHg. Neither skin lesions nor peripheral neuropathy suggestive of vasculitis was observed. Laboratory tests showed thrombocytopenia and a coagulation disorder including hypofibrinogenemia (143.5 mg/dL), suggesting disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Elevation of hepatobiliary enzymes, C-reactive protein, lactate dehydrogenase, soluble interleukin-2 receptor (5,040 U/mL), and ferritin (9,176.1 ng/mL) were also noted (Table). Proteinuria was transiently observed, but it resolved within a few days. A histological examination of the lymph node was not performed because of the urgent need for treatment. MAS due to the recurrence of Kikuchi disease was diagnosed according to the 2004 diagnostic guidelines for HLH (7). Cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, marked thickening of the gallbladder wall (>15 mm), pericholecystic fluid, but no signs of intestinal obstruction were detected on computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography (Fig. 1A-F). A gallstone was also found in the fundus, but neither any impaction of the stone nor dilatation of the common bile duct was detected (Fig. 1A). So-called acute acalculous cholecystitis with a gallstone secondary to MAS was therefore diagnosed clinically and radiologically.

Table.

Laboratory Data on Admission.

| Complete blood count | Blood chemistry | Immunology | |||

| White blood cells | 38,000 /µL | Total protein | 7.2 g/dL | C-reactive protein | 5.03 mg/dL |

| Neutrophil | 89.0 % | Albumin | 3.9 g/dL | Procalcitonin | 30.69 mg/mL |

| Lymphocyte | 7.0 % | Total bilirubin | 2.03 mg/dL | Antinuclear antibody | 320 fold (Speckled) |

| Monocyte | 3.0 % | Direct bilirubin | 1.50 mg/dL | C3 | 80 mg/dL |

| Atypical lymphocyte | 1.0 % | Aspartate aminotransferase | 577 IU/L | C4 | 37 mg/dL |

| Red blood cells | 460×104 /µL | Alanine aminotransferase | 303 IU/L | IgG | 1,386 mg/dL |

| Hemoglobin | 12.0 g/dL | Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase | 119 IU/L | IgA | 301 mg/dL |

| Hematocrit | 35.1 % | Alkaline phosphatase | 619 IU/L | IgM | 64 mg/dL |

| Platelets | 8.4×104 /µL | Lactate dehydrogenase | 3,606 IU/L | Anti-dsDNA antibody | <10 IU/mL |

| Coagulation system | Blood urea nitrogen | 19.6 mg/dL | MPO-ANCA | <1.0 EU | |

| PT/INR | 1.50 | Creatinine | 0.81 mg/dL | PR3-ANCA | <0.1 EU |

| APTT | 50.5 sec | Sodium | 136.4 mEq/L | Soluble IL-2R | 5,040 U/mL |

| Fibrinogen | 143.5 mg/dL | Potassium | 3.83 mEq/L | ||

| Fibrin degradation protein | >200 µg/mL | Chloride | 103.5 mEq/L | ||

| D-dimer | >200 µg/mL | Ferritin | 9,176.1 ng/mL |

APTT: activated partial thromboplastin time, dsDNA: double-stranded DNA, IL-2R: interleukin-2 receptor, MPO-ANCA: myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, PR3-ANCA: proteinase 3 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, PT/INR: prothrombin time/international normalized ratio

Figure 1.

Imaging performed on admission (A-F) and the sixth day of admission (G, H). A, B: Ultrasonography showed marked thickening of the gallbladder wall, a gallstone (A), and pericholecystic fluid (B; arrow), but neither impaction of the stone nor dilatation of the common bile duct was detected. C: Cervical lymphadenopathy (arrows) and D: axial lymphadenopathy (arrows) were detected by contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT). E, F: Marked thickening of the gallbladder wall (>15 mm) and pericholecystic fluid were detected by CT. G, H: Follow-up CT performed on the sixth day of the admission showed a significant improvement of the gallbladder wall thickening and pericholecystic fluid.

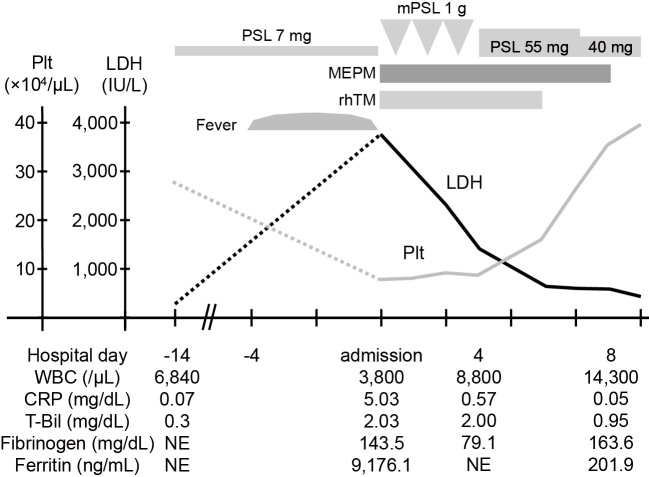

Intravenous pulse methylprednisolone (mPSL) 1 g/day for 3 days, followed by PSL 55 mg/day, and meropenem hydrate (1 g/day) were immediately initiated in addition to recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin (19,200 U/day) for DIC treatment. Both the fever and lymphadenopathy improved by the next day, as well as thrombocytopenia, coagulation disorder, and hyperferritinemia. On the sixth day of admission, follow-up CT revealed a dramatic improvement of the gallbladder wall thickening and pericholecystic fluid (Fig. 1G and H). The 2 sets of blood cultures collected on admission exhibited no growth. Antibiotic therapy was discontinued and PSL was tapered. She has remained clinically well without any relapse of Kikuchi disease or cholecystitis even after the PSL was tapered to 6 mg/day. The clinical course is summarized in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Clinical course of our patient. CRP: C-reactive protein, LDH: lactate dehydrogenase, MEPM: meropenem hydrate, mPSL: methylprednisolone, NE: not examined, Plt: platelet count, PSL: prednisolone, rhTM: recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin, T-Bil: total bilirubin, WBC: white blood cell count

Discussion

AAC can develop in patients with MAS, but this phenomenon has only rarely been reported. Although the association between AAC and MAS is still not fully understood, endothelial damage caused by the cytokine storm may be primarily involved in the pathogenesis of AAC (2,3,8). The pathogenesis of MAS is characterized by an impaired immune response with the hypersecretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the activation of cytotoxic cells (8). This excessive immune reaction results in endothelial injury and increased vascular permeability, possibly leading to local microvascular ischemia of gallbladder wall and bile stasis in AAC. Endothelial dysfunction has been suggested to play a central role in some forms of drug or infection-associated AAC cases (9,10). The incidence of AAC in MAS is not clear, but it may be relatively frequent in children with HLH. Schmidt et al. reported that 6 of 9 children with HLH had gallbladder wall thickening on ultrasonographic examination within 1 week of presentation (11). Chateil et al. reported that all of the 6 children with HLH examined by abdominal ultrasonography revealed thickening of the gallbladder wall, as well as in 14 of 21 children with HLH reported by Fitzgerald et al. (12,13). Lee et al. reported that of 67 children with AAC 4 of these children had HLH (14).

There is only one case report of an adult patient with MAS complicated with AAC. Park et al. reported the case of a 49-year-old female with a 7-year history of adult onset Still's disease (AOSD) who developed MAS and AAC (15). Unlike in children, there is no report evaluating the presence of gallbladder thickening in adult patients with MAS. These facts suggest that AAC could be more frequently associated with MAS in children than that in adults, although the pathogenesis of AAC is thought to be similar between children and adults (16). The precise mechanisms accounting for this difference are unknown, but one possible explanation is that children in critically ill and febrile conditions are more likely to develop hypovolemia, one of the risk factors for AAC (2). Another explanation could be that the treatment for MAS, using high-dose corticosteroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics, is normally initiated before abdominal imaging, which would thus improve AAC before it can be identified.

AAC associated with rheumatic or autoimmune diseases may possibly have a better response to immunosuppressive therapy, compared to that with other causes. In general, surgical intervention is recommended for patients with AAC because of the high risk of perforation. It is reported that perforation occurs in 10% and the mortality rate is 30% overall (17,18). A delay in treatment could raise the mortality rate up to as high as 75% (19). However, in the case reported by Park et al., the patient who developed MAS and AAC was successfully treated with PSL and cyclosporine A without surgical intervention (15). It has also been reported that some patients with SLE complicated by AAC were successfully treated with immunosuppressive therapy (4-6). Our patient recovered immediately after the initiation of intravenous pulse mPSL and the follow-up CT showed significant improvement in the gallbladder wall, resulting in no need for surgical intervention. Therefore, early immunosuppressive therapy under careful observation should be carried out for AAC cases with rheumatic or autoimmune diseases.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1.Barie PS, Eachempati SR. Acute acalculous cholecystitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 5: 302-309, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huffman JL, Schenker S. Acute acalculous cholecystitis: a review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 8: 15-22, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filipovich A, McClain K, Grom A. Histiocytic disorders: recent insights into pathophysiology and practical guidelines. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16: S82, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamimura T, Mimori A. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report and review of the literature. Lupus 7: 361-363, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi YJ, Yoon HY. A case of systemic lupus erythematosus initially presented with acute acalculous cholecystitis. J Rheumatic Diseases 21: 140-142, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin SJ, Na KS. Acute acalculous cholecystitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus with Sjögren's syndrome. Korean J Intern Med 17: 61-64, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 48: 124-131, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravelli A, Davì S, Minoia F, Martini A, Cron RQ. Macrophage activation syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 29: 927-941, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.da Fonseca LG, Barroso-Sousa R, Sabbaga J, Hoff PM. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in a patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. Clin Pract 4: 635, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guner R, Hasanoglu I, Yapar D, Tasyaran MA. A case of Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever complicated with acalculous cholecystitis and intraabdominal abscess. J Clin Virol 50: 162-163, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt MH, Sung L, Shuckett BM. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in children: abdominal US findings within 1 week of presentation. Radiology 230: 685-689, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chateil J, Brun M, Perel Y, Pillet P, Micheau M, Diard F. Abdominal ultrasound findings in children with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Eur Radiol 9: 474-477, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzgerald NE, MacClain KL. Imaging characteristics of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Radiol 33: 392-401, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JH, No YE, Lee YJ, Hwang JY, Lee JW, Park JH. Acalculous diffuse gallbladder wall thickening in children. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 17: 98-103, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park JH, Bae JH, Choi YS, et al. Adult-onset Still's disease with disseminated intravascular coagulation and multiple organ dysfunctions dramatically treated with cyclosporine A. J Korean Med Sci 19: 137-141, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poddighe D, Tresoldi M, Licari A, Marseglia GL. Acalculous acute cholecystitis in previously healthy children: general overview and analysis of pediatric infectious cases. Int J Hepatol 2015. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagino RT, Valentine RJ, Clagett GP. Acalculous cholecystitis after aortic reconstruction. J Am Coll Surg 184: 245-248, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barie PS, Eachampati SR. Acute acalculous cholecystitis. Gastroenteral Clin North Am 39: 343-357, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornwell EE 3rd, Rodriguez A, Mirvis SE, Shorr RM. Acute acalculous cholecystitis in critically injured patients. Preoperative diagnostic imaging. Ann Surg 210: 52-55, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]