Abstract

Capacity to make one's own decisions is fundamental to the autonomy of the individual. Capacity is a functional assessment made by a clinician to determine if a patient is capable of making a specific decision. Competency is a global assessment and legal determination made by a judge in court. Capacity evaluation for a patient with dementia is used to determine whether the patient is capable of giving informed consent, participate in research, manage their finances, live independently, make a will, and have ability to drive. Patients with dementia cannot be assumed to have impaired capacity. Even a patient with moderate or severe dementia, with obviously impaired capacity may still be able to indicate a choice and show some understanding. Four key components of decision-making in a capacity evaluation include understanding, communicating a choice, appreciation, and reasoning. Assessment of capacity requires a direct interview with the patient using open-ended questions and may include both informal and formal approaches depending on the situation and the context. A baseline cognitive evaluation with a simple test to assess executive function is often useful in capacity evaluation. All capacity evaluations are situation specific, relating to the particular decision under consideration, and are not global in scope. The clinician needs to spend adequate time with the patient and the family allaying their anxieties and also consider the sociocultural context. The area of capacity has considerable overlap with law and the clinician treating patients with dementia should understand the complexities of assessment and the implications of impaired capacity. It is also essential that the clinician be well informed and keep meticulous records. It is crucial to strike a balance between respecting the patient autonomy and acting in his/her best interest.

Key Words: Capacity issues, competency, decision making, dementia

“Not knowing where I am doesn't mean I don't know what I like”

–Mozley et al. 1999[1]

Introduction

Capacity to make one's own decisions is fundamental to individual autonomy. Most of us have had a parent, a grandparent, or an elderly relative whose declining cognition caused us concern and raise questions about their ability to live independently, drive or manage their finances. Sometimes, these issues may be more critical and make a difference to whether the person lives independently or is placed in a facility. The clinician may be involved in formal certification of capacity of a patient with dementia. The main determinant of impaired capacity is cognition and any condition affecting cognition can affect capacity. Capacity can be impaired in head injury, psychiatric diseases, delirium, depression, and dementia.[2] Capacity may be financial, testamentary, for driving, voting, consent to research and treatment, and to live independently. In this paper, we discuss capacity in relation to dementia and highlight some important areas.

Terminology

It is important to make a distinction between capacity and competency, which have overlapping meanings, but the context of use is different.[3] Capacity refers to a person's ability to make a particular decision at a specific time or in a specific situation. Competency refers to legal capacity and is determined by a judge in court. It is a threshold requirement imposed by society for an individual to retain decision-making power in a particular activity or set of activities.[3,4]

Most clinicians familiar with the patient can make a capacity assessment. The clinician determines whether the patient has the capacity to understand, make his/her own decisions, and take responsibility for the consequences of the decision while the courts determine whether the person has competence or legal right to make independent decisions. The medical concept of capacity is universal while the judicial concept is restricted by the rules of the national legal system, which will differ from country to country.

Capacity and Dementia

Patients with dementia cannot be assumed to be incapable of making decisions. Patients with mild to moderate dementia can evaluate, interpret, and derive meaning in their lives. The law assumes that all adults have capacity unless there is contrary evidence.[5]

Capacity must be assessed in relation to the particular decision an individual needs to make at the time the decision needs to be made. A person is without capacity if, at the time that a decision needs to be taken, he or she is unable by reason of mental disability to make a decision on the matter in question, or unable to communicate a decision on that matter because he or she is unconscious or for any other reason.[6] It is worth emphasizing that capacity is not global in scope. For a particular decision, the person has either capacity or lacks capacity. Most decisions of life are made by people independently. Decisions are also constrained by our personal choice, values, relationships, and culture and may not be always based on logic or deliberation. Education and occupation also influence decision-making ability.[7] There are four decision-making abilities that characterize capacity: Understanding, appreciation, reasoning, and expressing a choice.[8] Decision-making ability is also not static. Fluctuations, medications, delirium, infections, drowsiness, and sundowning can affect capacity, and these factors should be taken due note of.[3,7] Treatment of reversible conditions can improve capacity.

Capacity is required for valid informed consent. Capacity, though dependent on cognition, is not the same as cognition. It is also different from functional activities. A person unable to do a task may be capable of deciding who can assist her or him to do the task.

Impaired decision-making was found in 44–69% of residents in nursing homes.[9,10,11] Marson et al. found that nearly all patients with mild-moderate Alzheimer's disease (AD) were impaired at decision-making (understanding component) but could still perform as well as controls on appreciation, reasoning, and choice.[12] Ability to express a choice and provide some reasoning is often preserved in patients with AD. They can make a decision about preference related to daily care but not make a decision about complex treatment choice. Even a patient with advanced dementia may have capacity to appoint a health-care proxy but not make a living will. Patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia may perform well on standard neuropsychological tests but show impaired judgment and decision-making.[13]

Patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI) were able to express choice but were impaired on appreciation, reasoning, and understanding compared to controls.[14] The same authors investigated longitudinal change in medical decision-making capacity in MCI and found a significant decline in understanding over 3 years but not on the other three decision-making abilities though these were also impaired compared to controls.[15]

In a study on research consent capacity, patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) with borderline cognitive impairment had impaired decisional capacity, and Montreal Cognitive Assessment was more sensitive in detecting patients at risk as compared to mini–mental state examination (MMSE).[16]

Assessment of Capacity

Capacity should be assessed in a semi-structured direct interview with the patient.[3,7] The patient should have adequate and relevant information about the issue under discussion (disease, treatment options, etc.). The clinician uses open-ended questions to evaluate at least one of the four aspects of decision-making abilities.[3,7] Assess understanding first (ability to understand meaning of information – e.g., “what is dementia” or “what is PD,” “what are the risks and benefits of a particular treatment?“) and then ask for a choice (selecting a clear choice when given multiple options – “yes I understand the risks of not taking levodopa but I do not want to start now”). Assess appreciation and reasoning about the choice next. Appreciation is applying facts to one's own life (“how disease like PD may affect me now and in future”). Reasoning is the ability to compare options and then make a choice with understanding of the consequences of the choice. Finally, a reassessment of choice should be done. This should be consistent and stable over time (e.g., 24 h).[3]

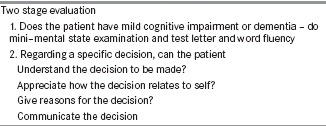

Capacity evaluation is a two-step process. First, the clinician assesses a person's decisional abilities as described above. A judgment regarding the person's capacity for a particular decision (e.g., consent) is reached using these results, considering the context and the risk–benefit ratio of the various options. While determining capacity, one should strike a balance between respecting patient's autonomy and acting in their best interest. A clinician has a clinical and ethical responsibility to accurately assess the decision-making capacity of a patient. It is also possible that these decisions are sometimes reviewed critically in a court of law. Capacity assessments should be done carefully, cautiously, and completely. If the patient is harmed by the treatment, the doctor could be held responsible for not making a thorough assessment of the patient's capacity.[17] Capacity assessment must be very rigorous in situ ations where there are serious consequences of the decision-making. All four components of the assessment may not carry equal weight, and it would depend on the situation and context.

A person's capacity is a point along a continuum.[3] Capacity can be rated as adequate, inadequate, and marginal. Sometimes, the patient refuses assessment or the family disagrees with the assessment. In such situations, the clinician should be not only tactful and cautious but also communicate clearly the need for further assessment or the reasons for inadequate capacity and keep adequate records.

If the clinician makes a diagnosis of impaired capacity, there may be several implications depending on the severity of the cognitive impairment, situation, and decision. In urgent situations, a reliable caretaker should be appointed. The clinician should also look for any reversible or treatable factors.[3,7]

Assessment Tools

MacArthur Competence Assessment Tools for Treatment is a frequently used tool to assess competence and has been validated in patients with dementia. The test consists of a hospital chart review followed by a semi-structured interview and scored for four domains of capacity.[18]

Tests such as the Assessment of Capacity for Everyday Decision-making are useful to understand, if a person who has a functional deficit, (such as problems managing money) understands and appreciates this problem, understands and appreciates the risks and benefits of solutions to that problem, and can reason through choices about how to solve this problem.[19]

Formal assessment of capacity is not required in each patient. It may be obvious that the patient may have adequate capacity for a particular decision in mild dementia or may lack the capacity as in severe dementia. Formal testing may be required in situ ations, in which capacity is unclear, there is disagreement among family members or surrogate decision makers or a judicial involvement is anticipated.

Role of Neuropsychological Tests

Neuropsychological tests help understand the neural basis of decision-making abilities, indicate interventions, and also act as a tool to assess capacity.[11,12,20,21] Marson et al. worked extensively on developing a “neurological model of incompetence” and stressed the importance of testing executive functions in predicting impairment in decisional ability.[20] Bedside, tests such as the executive interview[22] and formal neuropsychological tests such as tests of conceptualization,[20] Trails A,[21] and fluency tests[23] can be used to measure aspects of executive function. Verbal memory is also important as the patient has to attend to information, encode it, and then recall the information.[3,7]

The level of cognitive function and level of decisional ability for any single individual would vary. It is important for clinicians to understand the relationship between these two parameters as it has a significant impact on their judgment regarding the patient's capacity.[24]

The MMSE is a widely used tool of cognition in clinical practice. It is easy to administer, requires no formal training, and is easily available. Various studies have also shown correlation with the MMSE scores, scores below 16 were highly correlated with impaired capacity whereas >24 score correlated with retained ability.[9,10] However, a normal MMSE does not rule out impaired capacity. Although high scores may indicate better decision-making ability,[10] it would be preferable to use the MMSE in conjunction with other neuropsychological tests and interventions to improve the patient's comprehension of the tasks to be done. Tests of capacity are often used to determine the extent of an individual's independence and therefore making judgments based on only one parameter would be erroneous.

There is currently no single test, which could be considered a gold standard test for capacity assessments. In clinical practice, a combination of clinicians judgment with a structured capacity interview[25] and neuropsychological tests that include executive function tests would be ideal [Box 1].

Box 1.

Assessment of mental capacity

In the following section, we discuss briefly capacity in specific situations.

Disclosure of Diagnosis

In the past, it was common practice for doctors not to talk to patients directly. Increasingly, however, patients today want to actively participate in the treatment discussion. This is no different in dementia, certainly in the early stages. Patients have a right to know, and this may help in persuading the patient to accept help and also make decisions about driving, medication, and future care.[26] The stage of the illness at the time of disclosure of diagnosis should also be considered. As dementia progresses, decision-making capacity and competency will be affected, and the ability to understand the diagnosis and its implications is limited. In the later and severe stages of the illness, comprehension is affected to such a degree that it will not matter to the patient and disclosure would be futile.[27]

There is debate over the content of the disclosure, but in general, there is consensus that the majority of the patients with dementia wish to be told the diagnosis. A study by Pinner and Bouman which explored the differences in attitudes of patients in early stages and their caregivers found that nearly 92% of patients wished to be fully informed, and the number of carers who felt disclosure is essential was also high.[28] When faced with a situation when the carer feels the diagnosis should be withheld, it is important to discuss with them their fears and anxieties and acknowledge their desire not to cause any distress to the patient. By carefully discussing the issue and dealing with the disclosure in a sensitive manner, much of the anxiety and pain associated with the disclosure can be mitigated.[29] There is little evidence to suggest that patients come to any long-term harm such as depression, anxiety, or suicide, following the diagnosis.[30]

Driving and Dementia

We have an aging population that has driven their own car for most of their adult life. As clinicians, we come across strong protests from patients and their spouses when advised not to drive. In a country, where traveling by public transport is still an ordeal, driving one's own car gives a person an immense sense of freedom and independence.

Drivers with dementia will pose a risk to themselves and other road users, particularly as the illness progresses. However, it is not fair to generalize the rules, as not everyone with dementia is at the same stage of the illness and even the type of dementia will vary.[31] A study by Croston et al. found that patients with AD have difficulty with traffic awareness, maintaining appropriate speeds, and staying in lane.[32] Drivers with a score of 1 on clinical dementia rating scale were found to have an increased risk of crashes and abnormal driving behaviors than those with scores of 0.5.[33]

Asking the carers to make a decision about the patient's driving also has its limitations. Carers often feel guilty of being the person who made the patient give up their license,[34] and long-standing family dynamics may come in the way of the decision and convincing. A doctor or authority figure is in a better position to make the recommendation to stop driving.[35]

Clinicians may need to check about right-left orientation, reaction speed, and judgment, determine if there have been any recent accidents or episodes of disorientation, and ask the caregiver to be more alert and vigilant about these areas and inform at the earliest signs of concern. It is advisable that clinicians discuss driving cessation with patients as early as possible as it is more likely that the patient will be able to participate in the discussion. In early stages, the patient may be advised to stick to familiar routes and avoid driving at night. Molnar et al. found that one of the most pertinent questions for relatives or cares would be “Would you feel it was safe if a 5-year-old child was in the car alone with the person driving?”[36] An opportunity to review the patient every 6 months would be ideal. If the patient consents to stop driving when they are deemed no longer fit, there is not a problem. However, if the clinician is not able to persuade the patient to stop even when there is clear evidence of it being unsafe, then the clinician's decision regarding capacity to drive should be clearly documented in the patient's notes. It may help if the patient is informed that if a doctor has declared them unfit, then they will not be protected for their insurance claims after that date.

Prescribing Medication in Dementia

Apart from the cholinesterase inhibitors, patients with dementia are often prescribed psychotropic medication for behavior disturbances and agitation associated with the illness. In many cases, the patient is not aware of these medicines. It is important to determine to what extent the patient can participate in the discussion of prescribing and their mental capacity. Patients who comply but incapacitated are perhaps the most vulnerable and good quality care with adequate safeguards must be exercised to prevent abuse.[37]

In those patients where capacity to make decisions regarding medication is intact, the clinician should spend enough time discussing the benefits and risks of the medications and answer questions. Patient information leaflets cannot be solely relied upon.[38]

Testamentary Capacity

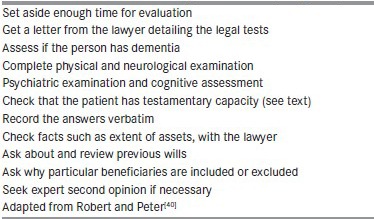

Testamentary capacity is the legal status of being able to execute a will, with regard to distribution and disbursement of assets and property after one's death. The Indian succession Act, 1925 (sec 59) stipulates among other things that any person of sound mind can make a will. Testamentary capacity would include the ability to understand the nature and effect of making a will, extent of his or her property and assets, consequences of his or her actions, and claims of the expected beneficiaries. There should be no mental illness.[39] As with other capacities, testamentary capacity is both task-specific and situation-specific. When medical opinion is requested for an assessment of testamentary capacity, Jacoby and Steer have suggested a few key points to ensure no omissions [Box 2].[40] It is important to check with the patient why if they have already made a will they feel the need to change it.

Box 2.

Process for assessing testamentary capacity

Capacity to Consent to Research

Consent from the individual and family is a key requirement for research. This along with approval of appropriate Research Ethics Committee ensures in safeguarding the interests of the participating individual. The research participant must be adequately informed about relevant facts of the research study and must provide free and informed consent.[41] The assessment of risk involved is also a vital part of the discussion. To be properly informed the participant must be able to ask valid questions about the risk of any procedure or intervention and be able to weigh the risks in relation to their health and other benefits. As the illness progresses in dementia, this is clearly not possible.

When a person is incapable of giving expressed consent, a substituted consent can be taken from their legal guardian. This is called proxy consent, and the decision is made by a surrogate decision maker. The generally accepted order is spouse, adult child, parents, siblings, and lawful guardian. The consent process should be clearly documented. However, from a moral and ethical perspective, we need to bear in mind that the legal representative may not be so familiar with the person participating in the research and that in consenting they may not be complying with the wishes of the incapacitated person.[42] Legal representatives may also find it difficult to provide consent because of feelings of guilt and find it stressful to bear the burden of decision-making.

Advanced care planning may include a statement of wishes and preferences, an advance directive (or living will) and proxy decision maker or power of attorney. See chapter “Palliative Care and the Indian Neurologists” in this issue for more details. Until advance directives in research come into practice, it may help to start discussing research with our patients, so they in turn can let their legal representatives know about their preferences. This would certainly be a step closer to ensuring some degree of autonomy in the decision-making process.

Record Keeping

A major pitfall in most cases when there is a legal case is inadequate records maintained by the medical professional. A doctor may have taken great pains to elicit information, engage the patient, or ensure that the patient has made an informed decision, but unless this is documented clearly in medical records the whole exercise would be futile. A few pointers on what needs to be documented would include date, names of relatives, relationship to patient, concerns raised and solutions offered, medications, dosages, side effects if any, diagnosis, and follow-up dates.[5]

Record keeping in India does not follow a uniform pattern in all institutions and either the patient has all the records or none. If the best practice is to be followed, then both parties need to hold on to relevant bits of information discussed during consultation. Record keeping keeps other professionals involved in the patients care to be informed. This ensures continuity of care and better coordination among health providers. There may be situations when doctors pick up something from the discussion which they feel is relevant to the diagnosis but not something they wish to share with the patient. In this case, this information may be documented in the doctors’ notes but not in the patient's copy.

Conclusion

A person's capacity to decide and make choices is an important part of who they are and how they wish to live. The assessment and question of one's capacity as discussed falls on a spectrum and varies according to the situation. As clinicians, it is our duty to not just assess but ensure that we have provided the conditions for the optimal level of functioning of the individual to enable them to make a decision.

This includes spending time to educate the person and their families, alleviating their anxieties, taking into account lucid intervals, and any physical conditions such as difficulty in speech, which may interfere with capacity. Only in doing so would we have acted in the patient's best interest.

Assessments of capacity are generally done over two to three settings each with an interval of a few days to ensure that responses are consistent on all occasions. It may still be that in spite of gathering all the information and evaluating in detail an error in deduction may occur. This happens because the clinician can only base their decision on the information provided to them and often this may be incomplete. It is never possible to interview all family members or have access to all records pertaining to the case. This should be explicitly stated in all reports. What a clinician states is merely an opinion or expert point of view, and the final decision is usually made by court in case of any contention.

From a legal perspective, all individuals, irrespective of age, are treated as the same and enjoy the same liberties and fall under the same jurisdiction. However, an elder may be more vulnerable and in need of more protection from law due to their life situation or illness such as dementia. This requires issues of capacity to be dealt with utmost sensitivity and care so that our patient's rights are always considered and protected.

While evaluating patients in our clinics, the thought that something we say or write may require justification in the future rarely crosses our mind. However, many clinicians are faced with the dilemma of having to prepare court reports for deceased patients in case of disputes over a will or provide reports for why a patient with dementia may not be able to attend a court summons. It is worth emphasizing that meticulous records are a must.

The area of capacity has considerable overlap with the law. Clinicians who regularly deal with patients who have deficits in cognition would need to be aware of the complexities of assessment and the implications of their judgment. This will ensure that their patient's interests are protected, and they can live their lives with maximum autonomy.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mozley CG, Huxley P, Sutcliffe C, Bagley H, Burns A, Challis D, et al. “Not knowing where I am doesn't mean I don't know what I like”: Cognitive impairment and quality of life responses in elderly people. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14:776–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binder RL, Guze SB, Appelbaum PS, Lieberman JA, Rabins PV, Oldham JM, et al. Guidelines for assessing the decision-making capacities of potential research subjects with cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1649–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karlawish J. Measuring decision-making capacity in cognitively impaired individuals. Neurosignals. 2008;16:91–8. doi: 10.1159/000109763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filakovic P, Eric AP, Mihanovic M, Glavina T, Molnar S. Dementia and legal competency. Coll Antropol. 2011;35:463–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong JG, Clare IC, Gunn MJ, Holland AJ. Capacity to make health care decisions: Its importance in clinical practice. Psychol Med. 1999;29:437–46. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Assessment of Mental Capacity: Guidance for Doctors and Lawyers. London: British Medical Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1834–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp074045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing Competence to Consent to Treatment: A Guide for Physicians and Other Health Professionals. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SY, Karlawish JH, Caine ED. Current state of research on decision-making competence of cognitively impaired elderly persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:151–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pruchno RA, Smyer MA, Rose MS, Hartman-Stein PE, Henderson-Laribee DL. Competence of long-term care residents to participate in decisions about their medical care: A brief, objective assessment. Gerontologist. 1995;35:622–9. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.5.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Royall DR, Cordes J, Polk M. Executive control and the comprehension of medical information by elderly retirees. Exp Aging Res. 1997;23:301–13. doi: 10.1080/03610739708254033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marson DC, Ingram KK, Cody HA, Harrell LE. Assessing the competency of patients with Alzheimer's disease under different legal standards. A prototype instrument. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:949–54. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540340029010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manes F, Torralva T, Ibáñez A, Roca M, Bekinschtein T, Gleichgerrcht E. Decision-making in frontotemporal dementia: Clinical, theoretical and legal implications. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2011;32:11–7. doi: 10.1159/000329912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okonkwo OC, Griffith HR, Belue K, Lanza S, Zamrini EY, Harrell LE, et al. Cognitive models of medical decision-making capacity in patients with mild cognitive impairment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008;14:297–308. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708080338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okonkwo OC, Griffith HR, Copeland JN, Belue K, Lanza S, Zamrini EY, et al. Medical decision-making capacity in mild cognitive impairment: A 3-year longitudinal study. Neurology. 2008;71:1474–80. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000334301.32358.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlawish J, Cary M, Moelter ST, Siderowf A, Sullo E, Xie S, et al. Cognitive impairment and PD patients’ capacity to consent to research. Neurology. 2013;81:801–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a05ba5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson E, Warner J. How much do doctors know about consent and capacity? J R Soc Med. 2002;95:601–3. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.95.12.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi C. The MacCAT-T: A clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:1415–9. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.11.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai JM, Gill TM, Cooney LM, Bradley EH, Hawkins KA, Karlawish JH. Everyday decision-making ability in older persons with cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:693–6. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31816c7b54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marson DC, Chatterjee A, Ingram KK, Harrell LE. Toward a neurologic model of competency: Cognitive predictors of capacity to consent in Alzheimer's disease using three different legal standards. Neurology. 1996;46:666–72. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bassett SS. Attention: Neuropsychological predictor of competency in Alzheimer's disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1999;12:200–5. doi: 10.1177/089198879901200406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Royall DR, Mahurin RK, Gray KF. Bedside assessment of executive cognitive impairment: The executive interview. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:1221–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb03646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marson DC, Cody HA, Ingram KK, Harrell LE. Neuropsychologic predictors of competency in Alzheimer's disease using a rational reasons legal standard. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:955–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540340035011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marson DC, Hawkins L, McInturff B, Harrell LE. Cognitive models that predict physician judgments of capacity to consent in mild Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:458–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Etchells E, Darzins P, Silberfeld M, Singer PA, McKenny J, Naglie G, et al. Assessment of patient capacity to consent to treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:27–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00277.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinner G. Truth-telling and the diagnosis of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:514–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.6.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinner G, Bouman WP. To tell or not to tell: On disclosing the diagnosis of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14:127–37. doi: 10.1017/s1041610202008347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinner G, Bouman WP. Attitudes of patients with mild dementia and their carers towards disclosure of the diagnosis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2003;15:279–88. doi: 10.1017/s1041610203009530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyers BS. Telling patients they have Alzheimer's disease. BMJ. 1997;314:321–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7077.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bahro M, Silber E, Sunderland T. How do patients with Alzheimer's disease cope with their illness? A clinical experience report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:41–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson S, Pinner G. Driving and dementia: A clinician's guide. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2013;19:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Croston J, Meuser TM, Berg-Weger M, Grant EA, Carr DB. Driving retirement in older adults with dementia. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2009;25:154–162. doi: 10.1097/TGR.0b013e3181a103fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dubinsky RM, Stein AC, Lyons K. Practice parameter: Risk of driving and Alzheimer's disease (an evidence-based review): Report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;54:2205–11. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.12.2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adler G, Rottunda S, Bauer M, Kuskowski M. Driving cessation and Alzheimer's dementia: Issues confronting patients and family. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2000;15:212–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown LB, Ott BR, Papandonatos GD, Sui Y, Ready RE, Morris JC. Prediction of on-road driving performance in patients with early Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:94–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molnar FJ, Byszewski AM, Marshall SC, Man-Son-Hing M. In-office evaluation of medical fitness to drive: Practical approaches for assessing older people. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:372–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Treloar A, Beck S, Paton C. Administering medicines to patients with dementia and other organic cognitive syndromes. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2001;7:444–50. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collier J. Patient-information leaflets and prescriber competence. Lancet. 1998;352:1724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79823-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiloha RC. Mental capacity/testamentary capacity. In: Gautam S, Avasthi A, editors. Clinical Practice Guidelines on Forensic Psychiatry. New Delhi: Indian Psychiatric Society; 2009. pp. 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacoby R, Steer P. How to assess capacity to make a will. BMJ. 2007;335:155–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39232.706840.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 118–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shalowitz DI, Garrett-Mayer E, Wendler D. The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:493–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]