Abstract

(−)-Epicatechin (EPI) is cardioprotective in the setting of ischemia/reperfusion (IR) injury and doxycycline (DOX) is known to preserve cardiac structure/function after myocardial infarction (MI). The main objective of this study was to examine the effects of EPI and DOX co-administration on MI size after IR injury and to determine if cardioprotection may involve the mitigation of mitochondrial swelling. For this purpose, a rat model of IR was used. Animals were subjected to a temporary 45 min occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Treatment consisted of a single or double dose of EPI (10 mg/kg) combined with DOX (5 mg/kg). The first dose was given 15 min prior to reperfusion and the second 12 h post-MI. The effects of EPI +/− DOX on mitochondrial swelling (i.e. mPTP opening) were determined using isolated mitochondria exposed to calcium overload and data examined using isobolographic analysis. To ascertain for the specificity of EPI effects on mitochondrial swelling other flavonoids were also evaluated.

Single dose treatment reduced MI size by ~46% at 48 h and 44% at three weeks. Double dosing evidenced a synergistic, 82% reduction at 3 weeks. EPI plus DOX also inhibited mitochondrial swelling in a synergic manner thus, possibly accounting for the cardioprotective effects whereas limited efficacy was observed with the other flavonoids. Given the apparent lack of toxicity in humans, the combination of EPI and DOX may have clinical potential for the treatment of myocardial IR injury.

Keywords: Epicatechin, Doxycycline, Ischemia-reperfusion, Mitochondrial swelling

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Prompt and successful reperfusion is the most effective strategy for reducing the extent of injury and infarction (Kloner et al., 2012). However, reperfusion of myocardium is an injurious event for which effective therapies have proven elusive (Yellon and Hausenloy, 2007). Epidemiological studies indicate that modest consumption of dark chocolate, which contains the flavonoid (−)-epicatechin (EPI), is associated with a decreased risk of ischemic heart disease (Janszky et al., 2009; Buijsse et al., 2010).

Mitochondrial dysfunction, arising from the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), is thought to be involved in mediating ischemia/reperfusion (IR) injury (Piot et al., 2008). Under normal conditions, the mPTP is closed and can open in response to IR induced challenges such as those triggered by low pH, calcium overload, and/or oxidative stress (Solaini and Harris, 2005). The opening of the mPTP leads to mitochondrial swelling, increasing cytoplasmic Ca+ + and the release of apoptogenic proteins such as cytochrome C and Bcl-2 potentially resulting in cell death (Piot et al., 2008; Bernardi et al., 2006; Honda et al., 2005). Cyclosporine, a known potent inhibitor of mPTP opening, was recently reported in a small clinical study to trigger cardioprotective effects (Lim et al., 2011). However, cyclosporine is known to have toxic properties. In spite of promising preclinical results from multiple pharmacological interventions so far, none have translated into the clinic (Graham, 1994).

We previously demonstrated in rat models of IR (Yamazaki et al., 2008) and permanent coronary occlusion (Yamazaki et al., 2010) that pre-treatment by gavage (1 mg/kg/day) with EPI reduces MI size and the effect is sustained at 3 weeks. Recently, we also reported that 10 mg/kg IV EPI given 15 min prior to reperfusion, yields reductions in MI size an effect that can be further enhanced by providing a second dose 12 h after reperfusion (Yamazaki et al., 2014). This effect followed the protection of mitochondria structure/function and involves specific mechanisms that yield the stimulation of pyruvate transport or oxidation, increased NADH levels and maintenance of ATP levels (Stanely, 2013). However, we did not explore effects on mitochondrial swelling (Yamazaki et al., 2014).

Members of the tetracyclines family of antibiotics can also exert cardioprotective effects. Minocycline has the capacity to block mPTP opening and is a potent anti-apoptotic agent (Scarabelli et al., 2004). Minocycline and doxycycline (DOX) can also inhibit mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and suppress the mPTP induced by Ca2+ via the inhibition of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (Schwartz et al., 2013). We previously reported that DOX, which can also act as an effective matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor, when provided for a limited duration, reduces adverse post-MI remodeling in rodents (Villarreal et al., 2003). In a clinical study, this observation was recently validated as short term DOX therapy limited adverse post-MI left ventricular remodeling (Cerisiano et al., 2014).

Given the cardioprotective properties of EPI and DOX we hypothesized that their combination may lead to additive or synergistic reductions in MI size, which may be further reinforced by repeat dosing and that the effects may be due to a mitigation of mitochondrial swelling.

To ascertain for the specificity of EPI effects, we also compared its actions on mitochondrial swelling with other flavonoids including, quercetin, epigallocatechin and epigallocatechin gallate.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

All chemicals used in the study were purchased from SigmaAldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated.

2.2. Experimental groups and treatment

Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) of 250–300 g were used. All procedures were approved by the local IACUC Committee and conform to published NIH guidelines for animal research. There were nine different groups of animals (a minimum of n =6 each) that underwent IR. EPI and DOX were prepared fresh for each experiment, and dissolved in water (pH 7.4). For the single dose group, control animals received water and treated animals received EPI (10 mg/kg) plus DOX (5 mg/kg) IV via the jugular vein 15 min prior to reperfusion. The dose selected for EPI had previously demonstrated to reduce MI size (Yamazaki et al., 2014) in single and double dosing experiments, whereas the dose of DOX selected had no effect on MI size as per our preliminary studies (data not shown). For the double dose group, animals received the initial IV treatment and a second IV dose 12 h later. Short term and long term effects of treatment were evaluated at 48 h (single dose only) or 3 weeks (single and double doses).

2.3. Surgical procedures

Animals were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), intubated, and positive-pressure ventilated (Yamazaki et al., 2008). A left thoracotomy was performed and the pericardium was incised to expose the heart. Left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery was identified and ligated at approximately 2 mm distal to its origin with 6/0 Ethicon suture; a small vinyl tube was used to occlude the artery (Yamazaki et al., 2008, 2010, 2014; Ciuffreda et al., 2014). The LAD was ligated for 45 min, released and the suture left in place as a point of reference. Successful occlusion and reperfusion were verified by visual inspection of LV color (Yamazaki et al., 2008, 2010, 2014; Ciuffreda et al., 2014). The chest was closed in layers and animals were allowed to recover. The evaluation of ST-segment elevation is the best procedure to assess successful occlusion and reperfusion (Lemos and Braunwald, 2001), and will be used in further studies.

2.4. Tissue collection and MI size determination

Following euthanasia, hearts were excised and weighed. The myocardial area at risk (AAR) was determined by the reocclusion of the snare and infusion of trypan blue into the cannulated aorta. If an area at risk was not identified, these animals were excluded from the studies. Five 2 mm ring were taken from the middle of the left ventricle (LV) and stained using triphenyltetrazolium chloride. Computer assisted image analysis was used to measure infarct area (IA) and AAR. Results are expressed as IA/AAR.

2.5. Mitochondrial isolation and calcium-induced mitochondrial swelling

Cardiac mitochondria were isolated as follows. Normal rat ventricles were excised and homogenized (0.1 g/ml) in solution A (sucrose 2 M, EDTA 0.01 M, HEPES 0.5 M: pH = 7.4), centrifuged 10 min (800 × g) at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged 10 min (8000 × g) at 4 °C. The pellet was recovered and re-suspended in solution B (sucrose 2 M, EDTA 0.01 M, Tris 0.5 M-H2PO4−50 mM: pH = 7.4) and centrifuged 10 min (10,000 × g) at 4 °C. The mitochondrial pellet was re-suspended in 10 ml of solution C (sucrose 2 M, EDTA 0.01 M, Tris 0.5 M-H2PO4−50 mM, succinate 1 pH = 7.4). Protein concentration of samples was determined using the Lowry method. Each sample used 200 µg of protein (i.e. mitochondria). All experiments were repeated five times and done in triplicate.

We explored the effects of flavonoids and DOX on calcium-induced mitochondrial swelling, by monitoring changes in optical density (OD, light absorbance) of mitochondria in suspension isolated from homogenized ventricular tissue. Swelling was identified as a decrease in light absorbance. A microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek®) was used to measure OD changes at 535 nm, continuously monitored during 30 min. To induce mitochondrial swelling, CaCl2 [1e−3 M] was applied to microplates containing mitochondria, simultaneously with either; 1) vehicle (ethanol), 2) EPI [1e−8–1e−3 M], 3) quercetin [1e−7–1e−3 M], 4) epigallocatechin [1e−7–1e−3 M], 5) epigallocatechin gallate [1e−7–1e−3 M] or 6) DOX [1e−10–1e−5M].

2.6. Isobolographic analysis

After determining the concentration–responses curves for EPI and DOX, we conducted an isobolographic analysis. This method allows for the theoretical analysis of dose combinations and is based on work reported by Tallarida which evaluates quantitatively and graphically the type of interaction between any two drugs (Tallarida, 2007, 2006). Briefly, after the effective concentrations (EC) for each compound are calculated, the theoretical values (e.g. EC50, EC40 and EC30) of combinations in a fixed ratio 1:1 are obtained according to equation (Eq. (1)) then they are substituted. by experimental values (Eq. (2)). a Theoretical

| (1) |

Meaning that, to determine an additive effect 1/2 EPI effective dose plus 1/2 DOX effective dose must be equal to (1).

The interaction of EPI with DOX is then experimentally evaluated by the simultaneous administration of 1/2 EPI (ECx)+1/2 DOX (ECx) doses. The experimental results obtained with the combinations used, then allows for the determination of the type of interaction observed between the two compounds;

| (2) |

As mentioned, when the experiment produces a result equal to 1, there is an additive effect, if the result is < 1, there is a synergism or supradditive effect and if the result is > 1 the effect is antagonistic.

2.7. Data analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. Statistical analysis were performed using Student t-test or ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc tests as appropriate. Significance was considered at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. IR studies

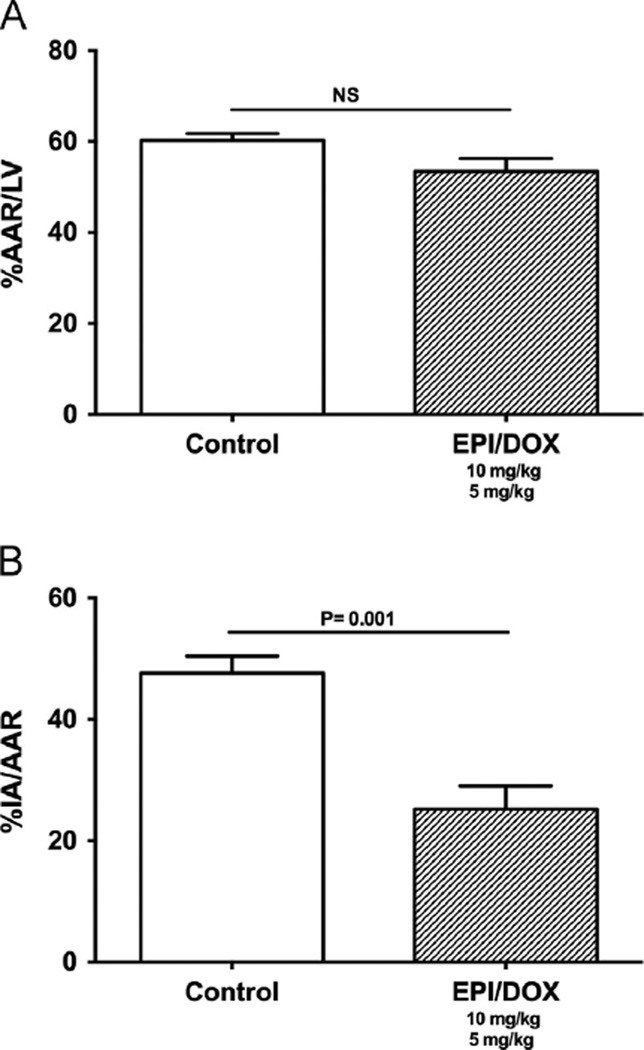

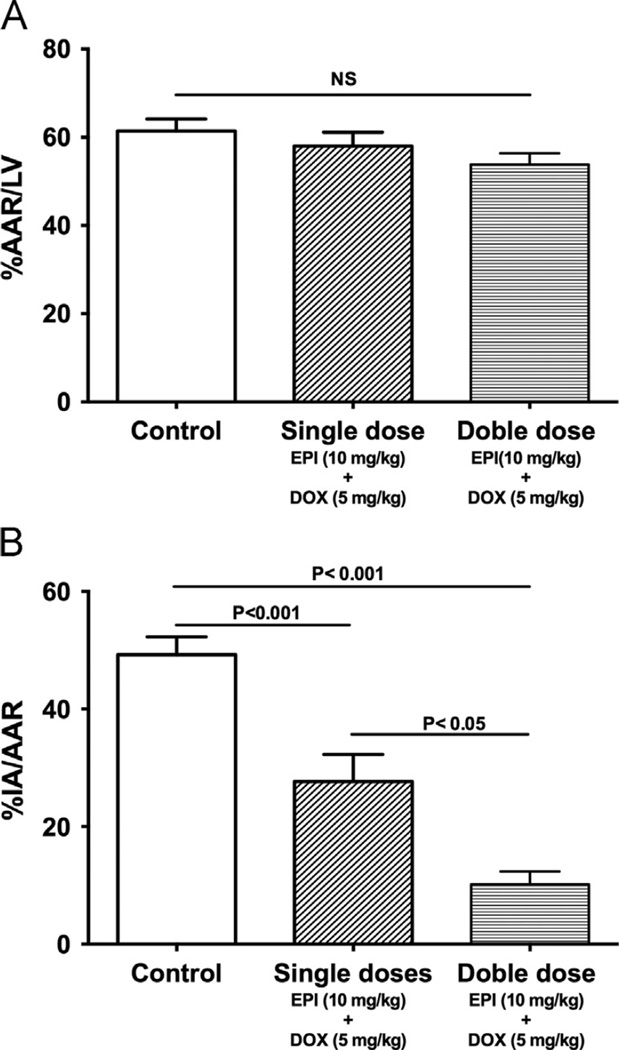

The results from the effects of single dose treatment 48 h after IR are plotted in Fig. 1. The two groups of animals examined (control and EPI plus DOX) had similar AAR (Fig. 1A). Fig. 1B illustrates the effects that single dose treatment exerted on MI size. Co-treatment led to a significant 46% (P < 0.001) reduction in IA/AAR. Results from the effects of single or double dose treatment 3 weeks after IR are shown in Fig. 2, where the AAR was comparable (Fig. 2A). After 3 weeks, single dose co-treatment led to a significant 44% reduction in IA/AAR (Fig. 2B). The effect was further reinforced by double dose co-treatment, which led to a significant 82% reduction in IA/AAR.

Figure 1.

Effects of single dose treatment in IR injury. (A) Effects of EPI and DOX co-treatment on 48 h area at risk (AAR) as percent of the total left ventricular area (LV). (B) Effects on infarct area (IA) normalized by AAR after ischemia reperfusion (IR) injury

Figure 2.

Effects of double dose treatment in IR injury at 3 weeks. (A) Effects of EPI and DOX co-treatment on 3 weeks area at risk (AAR) as a percent of the total left ventricular area (LV). (B) Effects on infarct area (IA) normalized by AAR after ischemia reperfusion (IR) injury after either single dose (n = 8) or double dose (n = 7) of EPI and DOX.

3.2. Calcium-induced swelling of isolated myocardial mitochondria

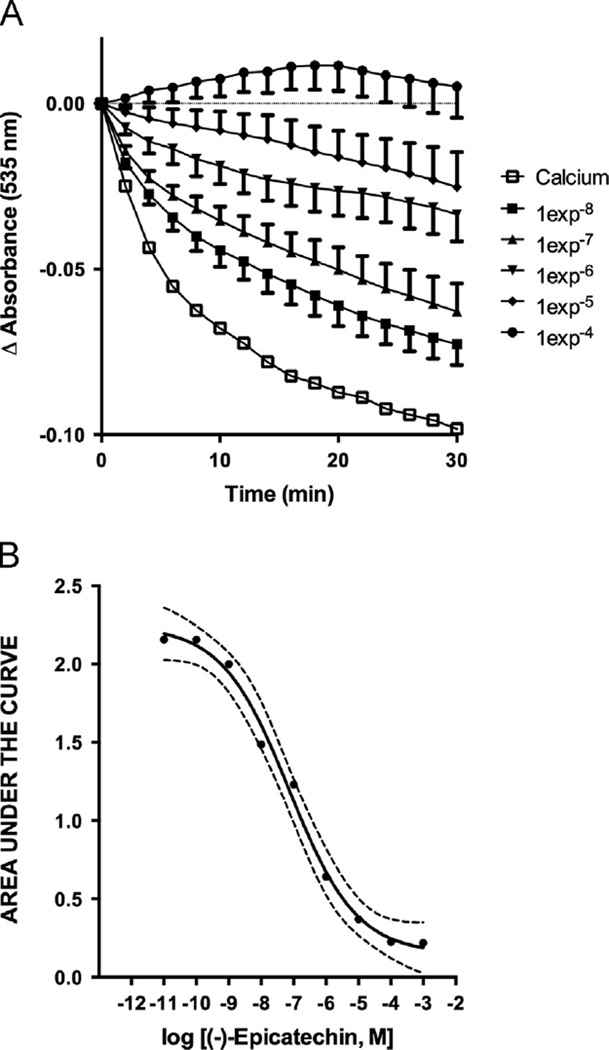

In preliminary experiments, we determined that calcium chloride [1e−3M] induced a significant decrease in light absorbance as result of mitochondrial swelling. Thus, this concentration was used for all experiments. Fig. 3 illustrates swelling values comparing calcium-induced effects vs. basal conditions (i.e. normal buffer). The addition of buffer and/or vehicle did not induced significant decreases in absorbance suggesting that mitochondria were stable during the experimental period of 30 min whereas calcium induced mitochondrial swelling was evidenced by reduced light absorbance.

Figure 3.

Effect of EPI on calcium induced mitochondrial swelling. A: Effects of EPI on temporal changes in calcium induced mitochondrial swelling, some time points and error bars were omitted for clarity. B: Concentration-swelling response curve analysis obtained from the area under the curve of the effect (n = 6, in triplicate)

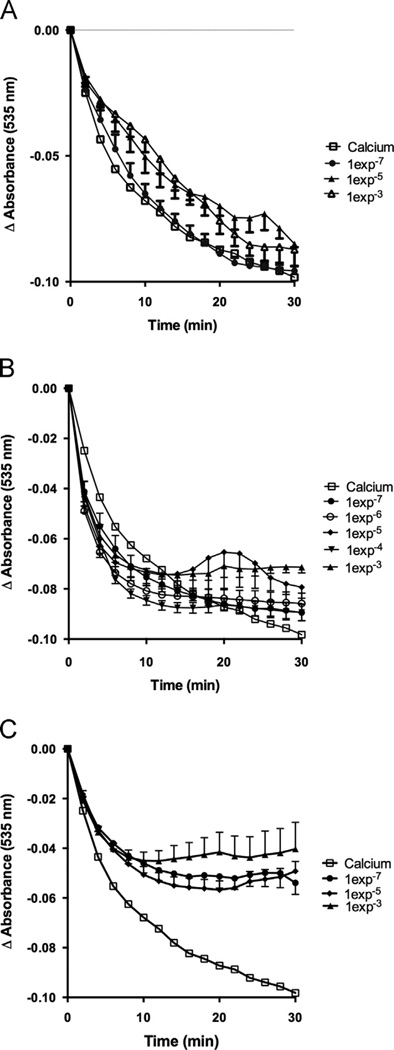

3.3. Effects of flavonoids on calcium-induced mitochondrial swelling

To assess EPI effects on calcium-induced mitochondrial swelling, increasing concentrations were used [1e−8–1e−3M]. EPI significantly inhibits calcium induced mitochondrial swelling (Fig. 3A). Plotting the area under the curve (blockage of swelling vs. time, (Fig. 3B) evidences a concentration-dependent effect. To determine if EPI–induced actions on mitochondrial swelling follow a general class effect, we evaluated epigallocatechin, epigallocatechin gallate and quercetin [1e−7–1e−3M]. Results indicate that epigallocatechin (Fig. 4A) and epigallocatechin gallate (Fig. 4B) have no significant effects on mitochondrial swelling. Quercetin induced a partial, (as compared with EPI) but significant reduction of mitochondrial swelling (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Epigallocatechin, epigallocatechin gallate and quercetin effects on calcium induced mitochondrial swelling. Effects of (A) epigallocatechin, (B) epigallocatechin gallate and C) Quercetin in calcium induced mitochondrial swelling. Some time points and error bars were omitted for clarity (n = 6)

3.4. Effects of DOX on calcium-induced mitochondrial swelling

To assess DOX effects on calcium-induced mitochondrial swelling, we used increasing concentrations of the compounds [1e−10–1e−5M]. Results indicate that DOX inhibits mitochondrial swelling (Fig. 5A). Plotting the area under the curve (Fig. 5B) also evidences a concentration-dependent effect.

Figure 5.

Effect of DOX on calcium induced mitochondrial swelling. (A): Effects of DOX on temporal changes in calcium induced mitochondrial swelling, some time points and error bars were omitted for clarity. (B): Concentration–response curve analysis obtained from the area under the curve of the effect (n = 8, in triplicate).

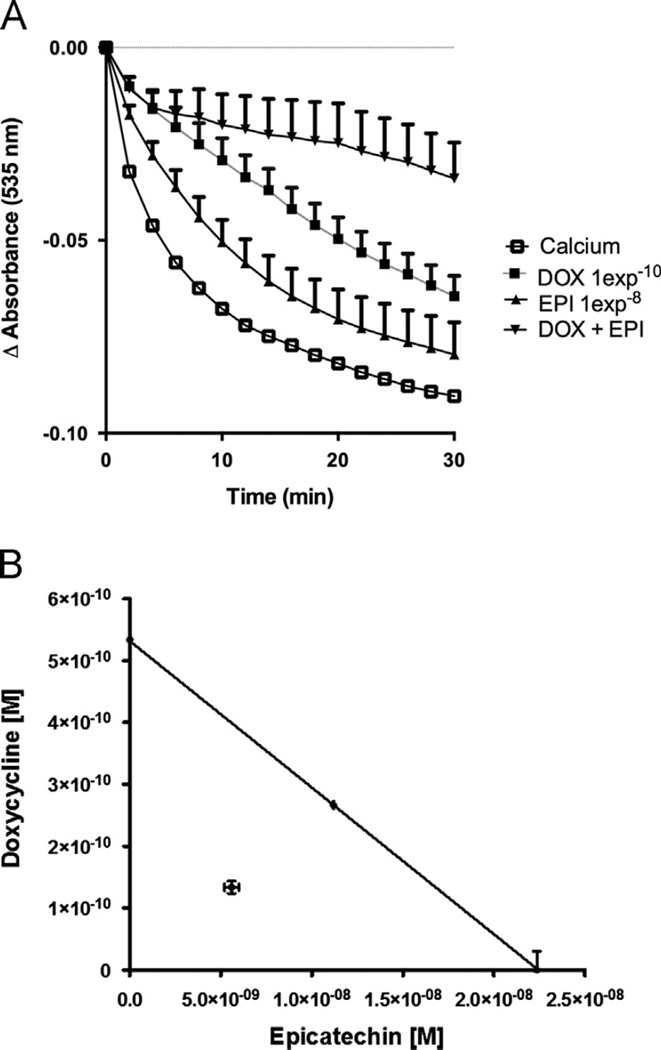

3.5. Effects of EPI in combination with DOX on calcium-induced mitochondrial swelling

After the effective concentrations for EPI and DOX were calculated (Table 1) from their respective concentration–response curves (Figs. 3 and 5B), a detailed isobolographic analysis was performed and the theoretical additive concentrations of the mixture of EPI and DOX were experimentally analyzed.

Table 1.

Effective concentration of Epicatechin and Doxycycline.

| Theoretical values | EPI [M] | DOX [M] |

|---|---|---|

| EC30 | 1.312e−9 | 3.169e−11 |

| EC40 | 2.2376e−8 | 5.338e−10 |

| EC50 | 3.811e−7 | 8.995e−9 |

An example of theoretical combined concentrations necessary to achieve 40% of maximal effect if an additive effect exist, is shown in Eq. (3). The result of this approach is equal to one (i.e. 1/2 of EPI concentration to achieve 40% of maximal effect plus 1/2 of DOX concentration to achieve 40% of maximal effect is = 1).

| (3) |

Fig. 5B shows a representative plot of EC40 for each drug, EPI [2.23e−8M] and DOX [5.33e−10M] (Eq. (4)) and the corresponding additive line.

The experimental testing for the combined effects of EPI and DOX document a significant blockade of mitochondrial swelling (Fig. 6A) as compared with the effects of each compound alone. The analysis of the experimentally combined concentrations of EPI plus DOX theoretically estimated to obtain 40% of maximal effect indicate graphically, that the inhibition of mitochondrial swelling falls below the additivity line (Fig. 6B) yielding an interaction value of 0.5 thus, evidencing a synergistic effect of EPI and DOX.

| (4) |

Figure 6.

Effect of the combination of EPI and DOX on calcium induced mitochondrial swelling. (A): Effects of EPI and DOX on temporal changes in calcium induced mitochondrial swelling. (B): The effective concentration 40 (CE40) for EPI and DOX are shown plotted graphically on the x- and y-axes, respectively. The isobolographic analysis demonstrates that the combination effect corresponds to a synergistic action (n = 6, in triplicate).

4. Discussion

Unique findings from this study indicate that co-treatment of EPI plus DOX leads to a reduction in IA of ~50% 48 h after IR and that this effect is sustained at 3 weeks. The use of a second dose of both compounds further increases the effect such that the reduction in IA by 3 weeks is ~80%. Thus, increasing the combined dosing scheme to twice after IR in essence essentially doubles the reduction in IA and provides a vigorously sustained effect. The synergistic inhibition of mitochondrial swelling by the combination of EPI and DOX reports on a novel mechanism for cardioprotection that has not been previously described. Furthermore, EPI effects do not appear to represent a class action as other flavonoids did not yield similar reductions on mitochondrial swelling.

Many compounds have been developed and examined for their cardioprotective potential (Muntean et al., 2014). The field is littered with compounds that failed clinical testing after yielding promising pre-clinical cardioprotective profiles. The reasons for such failure can be very complex and merit separate discussion. However, many of these studies have failed to consider the potential for multiple dosing schemes (i.e. to reinforce the protective effect of the compound). Furthermore, considerations as to the testing of possible combinations of drugs to reinforce complementary actions (while inherently complicated) have also been very limited.

Multiple epidemiological reports substantiate the cardiovascular risk reduction effects of products such as dark chocolate that are enriched for the flavonoid EPI. Further evidence is derived from studies of Kuna Indians (who consume high amounts of cacao based drink), which reveal an extremely low incidence of cardiovascular disease (Hollenberg, 2006). Published evidenced indicates that the beneficial effects of cacao is most likely mediated by EPI (Corti et al., 2009). Of the extensive body of literature published on studies using cacao-derived products none have reported adverse effects. Indeed, flavonoids in general are deemed to be a class of compounds that are likely non-toxic and well tolerated, in particular, when consumed in modest amounts (Galati and O'Brien, 2004).

In previous studies, we reported that oral pre-treatment of rats with low doses of EPI (1 mg/kg/day) yields cardioprotective effects. Cardioprotection was observed both in animal models of IR and permanent coronary occlusions (Yamazaki et al., 2008, 2010). Strikingly, 50% reduction in MI size was observed in both conditions raising the spectrum of unique capacities of EPI in protecting myocardium. While pre-treatment may offer the means to protect myocardium from ischemic injury (by having subjects intake modest amounts of EPI through natural foods or as a daily supplement) it does not address the “acute” potential of the flavanol to confer protection. In this regard, we recently pursued a study that tested this scenario using the same animal model as in this study. A single dose of EPI was able to reduce MI size by 27% at 48 h and 28% at 3 weeks, double dose treatment decreased MI size by ~80% at 48 h and ~50% by 3 weeks (Yamazaki et al., 2014). Thus, part of the protective effects upon double dosing was “lost” during post-MI healing a phenomenon that was apparently “pre-served” in the present study by using an unrelated class of drugs for the combined treatment approach.

Tetracyclines have been recognized as a genre of drugs with interesting pleiotropic properties, which include anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic and reactive oxygen species scavenging effects (Romero-Perez et al., 2008). Minocycline and DOX have been examined for the cardioprotective effects. Minocycline can readily cross cell membranes, concentrate in ischemic areas, has potent anti-apoptotic properties and can reduce IR injury in isolated cells and intact myocardium (Castro et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2003). DOX can also accumulate in ischemic tissues and is an effective inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases, which can importantly contribute to mediate IR damage and post-MI remodeling. DOX inhibits oxidative stress generation and improves NO bioavailability (Castro et al., 2012), these properties can be relevant in its cardioprotective effects in the IR model, since free radicals and nitric oxide play an important role in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-induced damage (Zweier and Talukder, 2006). We previously reported that limited exposure to DOX (30 mg/kg/day) can lead to the preservation of post-MI LV structure and function, partly due to MMP and serine protease inhibition. Given the above characteristics of the tetracyclines, it is reasonable to speculate that they may act in concert to limit IR injury (Castro et al., 2011). As with EPI, DOX has a well-recognized wide safety profile and is typically well-tolerated. This drug is available as an injectate and is commonly used in the clinical setting. Interestingly, a small clinical trial recently demonstrated that DOX provided to ST elevation MI patients orally at ~ 3 mg/kg/day for 7 days led to reductions in MI size and post-MI remodeling (Cerisiano et al., 2014). In our preliminary experiments we pre-determined that a single 5 mg/kg IV dose of DOX did not translate into MI size reduction effects and selected this dose for our experimental design.

Given the precedent data derived from our experience using EPI and DOX we speculated as to the possible complementary cardioprotective effects of both drugs when given prior to reperfusion and if such effects could be enhanced by multiple dosing schemes.

Results reported in the present work indicate that EPI and DOX co-treatment leads to a reduction in IA of ~ 46% at 48 h and that the effect is sustained at 3 weeks. The use of a double dose strikingly potentiates the effect such that the reduction in IA at 3 weeks is ~ 80% and favorably compares with the “lost” effect of only 50% MI reduction when only double dose EPI is given. Thus, increasing the combination dosing scheme to twice after reperfusion in essence doubles the reduction in IA and appears to enhance the cardioprotective effects of each drug. Since DOX at 5 mg/kg does not reduce MI size, its inclusion in our treatment scheme and enhancement of MI size reduction effects comprise a potentiation of EPI induced cardioprotection in a synergism like manner.

We recently reported that the protective effect of EPI on mitochondrial function was evident as early as 1 h after reperfusion when ventricular mitochondria demonstrated less respiratory inhibition, lower mitochondrial Ca2+ load, and a preserved pool of NADH that correlated with higher tissue ATP levels (Yamazaki et al., 2014).

Mitochondria are essential organelles because their primary function is the provision of ATP to cells. Mitochondria are also recognized as regulators of cell death via the modulation of apoptosis and necrosis. The mPTP appears to play an essential role in such processes. When mitochondria are challenged as with IR injury disruptive events such as calcium overload can occur, leading to pore formation allowing the organelle to swell and become dysfunctional compromising cell viability via the release of pro-apoptotic factors. Cyclosporine, is recognized as a potent inhibitor mPTP opening. In a small clinical trial of patients with acute ST elevation MI, cyclosporine (2.5 mg/kg IV) induced a ~25% but significant decrease in infarct size that was sustained at 6 months (Ghaffari et al., 2013).

In this study, we wished to determine if EPI and/or DOX exerted “protective” effects on mitochondrial swelling. Results obtained with EPI plus DOX on inhibition of mitochondrial swelling suggests that both compounds appear to stabilize mitochondria via distinct non-overlapping mechanisms given the synergistic effects observed. The inhibition of mitochondrial swelling by EPI and DOX is a novel mechanism for cardioprotection that has not been previously described. Of interest is that the mitochondrial actions do not appear to represent a general class effect as the other flavonoids tested (with similar antioxidant potential) either failed to inhibit swelling or yielded limited effects. Thus, these results dispel the notion that the effects observed represent anti-oxidant like effects of the compounds. However, it is possible that in the in vivo model, due to the free radical scavenger characteristics of EPI and DOX, a limited antioxidant effect could be present and coadyuvate in triggering the cardioprotective effects.

The main objective of this study was to analyze the potential for cardioprotective synergistic effects of EPI and DOX when applied in the clinically relevant scenario of IR. A potential mechanism that may explain the cardioprotective action is the synergistic reduction of mitochondrial swelling observed as per the modulation of the mPTP.

In conclusion, we believe that the combination of EPI and DOX represents a potential avenue for effective treatment of ischemic injury given their safety profile, favorable pleiotropic profiles and apparent complementary mechanisms of action. Further experiments are warranted in larger animal models before proceeding to clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

The work was partially funded by Conacyt Mexico Grant # 129889, IPN Mexico # 20140229 to GC; NIH HL-43617, AT004277, DK 092154 to FV and a Conacyt Fellowship to POV. Dr. Villarreal is a co-founder and Dr. Ceballos is a stockholder of Cardero Therapeutics.

References

- Bernardi P, Krauskopf A, Basso E, Petronilli V, Blachly-Dyson E, Di Lisa F, Forte MA. The mitochondrial permeability transition from in vitro artifact to disease target. FEBS J. 2006;273:2077–2099. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijsse B, Weikert C, Drogan D, Bergmann M, Boeing H. Chocolate consumption in relation to blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular disease in German adults. Eur. Heart J. 2010;31:1616–1623. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro MM, Kandasamy AD, Youssef N, Schulz R. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor properties of tetracyclines: therapeutic potential in cardiovascular diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2011;64:551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro MM, Rizzi E, Ceron CS, Guimaraes DA, Rodrigues GJ, Bendhack LM, Gerlach RF, Tanus-Santos JE. Doxycycline ameliorates 2K-1C hypertension-induced vascular dysfunction in rats by attenuating oxidative stress and improving nitric oxide bioavailability. Nitric Oxide. 2012;26:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerisiano G, Buonamici P, Valenti R, Sciagrà R, Raspanti S, Santini A, Carrabba N, Dovellini EV, Romito R, Pupi A, Colonna P, Antoniucci D. Early short-term doxycycline therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction and left ventricular dysfunction to prevent the ominous progression to adverse remodelling: the TIPTOP trial. Eur. Heart J. 2014;35:184–191. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciuffreda MC, Tolva V, Casana R, Gnecchi M, Vanoli E, Spazzolini C, Roughan J, Calvillo L. Rat experimental model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury: an ethical approach to set up the analgesic management of acute post-surgical pain. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti R, Flammer AJ, Hollenberg NK, Lüscher TF. Cocoa and cardiovascular health. Circulation. 2009;119:1433–1441. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galati G, O’Brien PJ. Potential toxicity of flavonoids and other dietary phenolics: significance for their chemopreventive and anticancer properties. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004;37:287–303). doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffari S, Kazemi B, Toluey M, Sepehrvand N. The effect of prethrombolytic cyclosporine-A injection on clinical outcome of acute anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2013;31:e34–e39. doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham RM. Cyclosporine: mechanisms of action and toxicity. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 1994;61:308–313. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.61.4.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda HM, Korge P, Weiss JN. Mitochondria and ischemia/reperfusion injury. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 2005;1047:248–258. doi: 10.1196/annals.1341.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janszky I, Mukamal KJ, Ljung R, Ahnve S, Ahlbom A, Hallqvist J. Chocolate consumption and mortality following a first acute myocardial infarction: the Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program. J. Intern. Med. 2009;266:248–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- K Hollenberg N. Vascular action of cocoa flavanols in humans: the roots of the story. J. Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;2:S99–102. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200606001-00002. discussion S19-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloner RA, Hale SL, Dai W, Gorman RC, Shuto T, Koomalsingh KJ, Gorman JH, 3rd, Sloan RC, Frasier CR, Watson CA, Bostian PA, Kypson AP, Brown DA. Reduction of ischemia/reperfusion injury with bendavia, a mitochondria-targeting cytoprotective peptide. J. Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e001644. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.001644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos JA, Braunwald E. ST segment resolution as a tool for assessing the efficacy of reperfusion theraphy. J. Am Coll. Cardiol. 2001;38:1283–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01550-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SY, Hausenloy DJ, Arjun S, Price AN, Davidson SM, Lythgoe MF, Yellon DM. Mitochondrial cyclophilin-D as a potential therapeutic target for post-myocardial infarction heart failure. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2011;15:2443–2451. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntean D, Duicu O, Privistirescu A, Danila M, Sturza A, Noveanu L, Baczko I, Jost N. Cardioprotection by pharmacological agents targeting mitochondria is preserved in isolated aged rat hearts (103) Cardiovasc. Res. 2014;15(Suppl 1):S26–S27. [Google Scholar]

- Piot C, Croisille P, Staat P, Thibault H, Rioufol G, Mewton N, Elbelghiti R, Cung TT, Bonnefoy E, Angoulvant D, Macia C, Raczka F, Sportouch C, Gahide G, Finet G, André-Fouët X, Revel D, Kirkorian G, Monassier JP, Derumeaux G, Ovize M. Effect of cyclosporine on reperfusion injury in acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:473–481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Perez D, Fricovsky E, Yamasaki KG, Griffin M, Barraza-Hidalgo M, Dillmann W, Villarreal F. Cardiac uptake of minocycline and mechanisms for in vivo cardioprotection. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;52:1086–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarabelli TM, Stephanou A, Pasini E, Gitti G, Townsend P, Lawrence K, Chen-Scarabelli C, Saravolatz L, Latchman D, Knight R, Gardin J. Minocycline inhibits caspase activation and reactivation, increases the ratio of XIAP to Smac/DIABLO, and reduces the mitochondrial leakage of cytochrome C and Smac/DIABLO. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004;43:865–874. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J, Holmuhamedov E, Zhang X, Lovelace GL, Smith CD, Lemasters JJ. Minocycline and doxycycline, but not other tetracycline-derived compounds, protect liver cells from chemical hypoxia and ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibition of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013;273:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solaini G, Harris DA. Biochemical dysfunction in heart mitochondria exposed to ischaemia and reperfusion. Biochem. J. 2005;390(Pt 2):377–394. doi: 10.1042/BJ20042006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanely Mainzen Prince P. (−) Epicatechin attenuates mitochondrial damage by enhancing mitochondrial multi-marker enzymes, adenosine triphosphate and lowering calcium in isoproterenol induced myocardial infarcted rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013;53:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida RJ. An overview of drug combination analysis with isobolograms. J Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;319(1):1–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida RJ. Interactions between drugs and occupied receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007;113:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal FJ, Griffin M, Omens J, Dillmann W, Nguyen J, Covell J. Early short-term treatment with doxycycline modulates postinfarction left ventricular remodeling. Circulation. 2003;108:1487–1492. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000089090.05757.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhu S, Drozda M, Zhang W, Stavrovskaya IG, Cattaneo E, Ferrante RJ, Kristal BS, Friedlander RM. Minocycline inhibits caspase-independent and -dependent mitochondrial cell death pathways in models of Huntington's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:10483–10487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832501100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki KG, Andreyev A, Ortiz-Vilchis P, Petrosyan S, Divakaruni AS, Wiley S, De La Fuente C, Perkins G, Ceballos G, Villarreal F, Murphy AN. Intravenous (−)-epicatechin reduces myocardial ischemic injury by protecting mitochondrial function. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014;175:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki KG, Romero-Perez D, Barraza-Hidalgo M, Cruz M, Rivas M, Cortez-Gomez B, Ceballos G, Villarreal F. Short- and long-term effects of (−)-epicatechin on myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008;295:H761–H767. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00413.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki KG, Taub PR, Barraza-Hidalgo M, Rivas MM, Zambon AC, Ceballos G, Villarreal F. Effects of (−)-epicatechin on myocardial infarct size and left ventricular remodeling after permanent coronary occlusion. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;55:2869–2876. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Myocardial reperfusion injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1121–1135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweier JL, Talukder MAH. The role of oxidants and free radicals in reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006;70:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]