Abstract

Aims:

Streptococcus mutans is the most common organism causing dental caries. Various chemotherapeutic agents are available that help in treating the bacteria, with each having their own merits and demerits. Recent research has shown that coconut oil has anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial action. Therefore, the present was conducted to determine the antibacterial efficacy of coconut oil and to compare it with chlorhexidine.

Materials and Methods:

A total of fifty female children aged 8–12 years were included in the study. Twenty five children were randomly distributed to each group, i.e., the study group (coconut oil) and the control group (chlorhexidine). The participants were asked to routinely perform oil swishing with coconut oil and chlorhexidine and rinse every day in the morning after brushing for 2–3 minutes. S. mutans in saliva and plaque were determined using a chairside method, i.e., the Dentocult SM Strip Mutans test. Patients were instructed to continue oil swishing for 30 days. S. mutans. counts in plaque and saliva on day 1, day 15, and day 30 were recorded and the results were compared using Wilcoxon matched pairs signed ranks test.

Results:

The results showed that there is a statistically significant decrease in S. mutans. count from coconut oil as well as chlorhexidine group from baseline to 30 days. The study also showed that in comparison of coconut oil and chlorhexidine there is no statistically significant change regarding the antibacterial efficacy.

Conclusion:

Coconut oil is as effective as chlorhexidine in the reduction of S. mutans.

Keywords: Coconut oil, dental caries, Streptococcus mutans

INTRODUCTION

Dental caries is a disease of multifactorial etiology. The diet, tooth morphology, oral environment, and microorganisms are associated with the caries process. The caries process is directly linked to the ability of microorganisms to colonize onto the tooth surface and form dental plaque. Streptococcus mutans is the predominant microorganism found in dental plaque associated with a caries lesion.[1] Therefore, prevention Therefore, prevention of dental caries should be directed toward the reduction of S. mutans.[1,2] Developme.[1,2] Development of a pr Development of a preventive regimen that targets the microbial risk factor is the most comprehensive and successful approach toward the prevention of caries. Even though mechanical methods of tooth cleaning are considered to be the most accepted and reliable method of oral health maintenance, chemotherapeutic agents are also used as adjuvants to reduce plaque formation.[3]

Ayurvedic literature mentions certain procedures such as Kavala graha or Gandoosha for oral hygien for oral hygiene maintenance.[4,5] They are discussed They are discussed in ancient texts of Charaka Samhita and Sushrutha's Samhitha.[6]. In Kavala graha or Gandoosha, an individual takes a certain amount of oil and holds it in the mouth for some time and swishes it all over the oral cavity, and when the oil turns milky white, it is spit out. Dr. F. Karach, a Russian scientist, popularized this procedure and described it as oil pulling in modern literature.[7] Newer studies of oil Newer studies of oil pulling therapy using various edible oils such as sunflower oil, sesame oil, and coconut oil were found to promote oral health.[8,9,10]

Coconut oil is widely used in Asian and Pacific regions as an edible oil. It differs from other edible oils because of high content of medium chain fatty acids. Coconut oil contains 92% saturated acids, with lauric acid being the main constituent. Lauric acid is seen in high concentration in human breast milk and has anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties.[11]

This study evaluated the efficacy of oil pulling therapy using coconut oil and compared it with chlorhexidine in reducing S. mutans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A comparative interventional study was performed to compare the antibacterial efficacy of coconut oil. The study was conducted in a residential educational centre for a period of 2 months. Three hundred children of age group 8–12 years were screened. Children were selected based on the inclusion criteria of decayed missing and filled (DMF) index of less than 2. Out of the 300 children, 50 were selected for the study. The sample size was derived by using the formula n = 4pq/d2. The exclu = 4pq/d2. The exclusion criteria were use of systemic or topical antibiotics, history of any dental treatment in the past 1 month, DMF scores of children more than 2, and children with any systemic or congenital diseases. The study and treatment protocol were explained in detail to the parents and informed consent was obtained. Institutional ethics committee approval was also obtained.

Each participant was assigned a specific numbassigned a specific number and a random sampling was done by using a table of random numbers. Fifty participants were divided into two groups with 25 children in each group

Group 1: Coconut oil group (study group)

Group 2: Chlorhexidine group (control group)

The number of S. mutans in plaque and saliva was determined using a chairside method, i.e., the Dentocult SM Strip Mutans test by Orion Diagnostica, ESPO, Finland.

The participants in each group were asked to routinely perform oil swishing with coconut oil or 2% chlorhexidine rinse every day in the morning after brushing for 2–3 minutes. Oil swishing was done under the observation of a care giver. The study was conducted by a single observer. The participants were given 5–10 ml of coconut oil/chlorhexidine and were asked to swish it all over the oral cavity with the mouth closed and to forcefully move it in between the teeth. No concealment of drugs was possible due to the taste difference in the materials used for the study. The plaque and saliva samples were collected within 30 minutes of oil/chlorhexidine swishing.

The samples were collected by a single examiner, who was blinded regarding the use of materials in the study. The examiner is a postgraduate student of dentistry possessing good knowledge about oral diseases. Day 0 was the baseline status of S. mutans in both the control and study groups. Plaque samples were collected from the buccal surface of the maxillary right molar, labial surface of the maxillary incisor, lingual surface of the mandibular incisor, and lingual surface of the mandibular left molar. These samples were gently spread on the rough surface of the plaque strip. For Saliva, samples were collected from each participant by chewing a paraffin pellet for 1 minute. The rough surface of Dentocult SM saliva strip was pressed against the saliva on the tongue. The strips were then placed in the selective cultural broth. The vials were labelled and incubated at 37°C for 48 hours with the cap opened one-quarter of a turn to allow microbial growth.

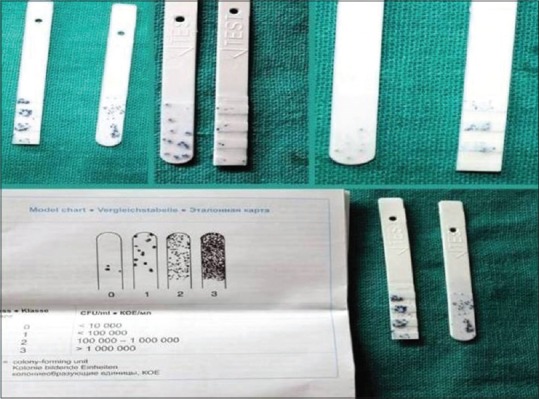

The presence of S. mutans was confirmed by the detection of light blue to dark blue, raised colonies on the inoculated surface of the strip and compared with the chart given by the manufacturer; the colonies were counted as per the manufacturer's instructions [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Raised colonies Raised colonies on strip with chart provided by manufacturer

Oil pulling with coconut oil was done for 30 days. The S. mutans counts in plaque and saliva samples were taken on day 1, day 15, and day 30. The growth of S. mutans colonies on the strips were counted and tabulated. Wilcoxon matched pairs signed ranks test was done to check the changes in mean scores, and Mann–Whitney U test was done to compare the results of two groups.

RESULTS

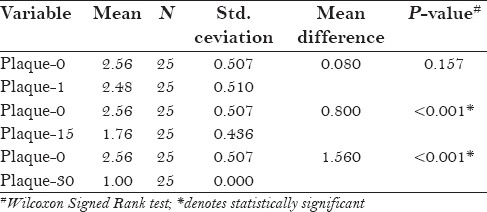

Changes in the mean scores of S. mutans in plaque samples from the baseline to day 30 in coconut oil group are shown in Table 1. Study shows that compare Study shows that compared to the baseline there was a statistically significant decrease in the S. mutans level from the plaque samples taken on day 15 and day 30 (P < 0.001) using the Wilcoxon Signed rank test.

Table 1.

Change in mean scores of S. mutans in plaque samples in group I

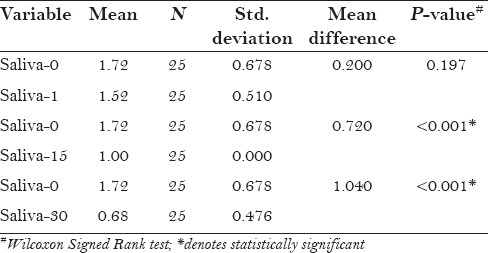

Table 2 shows changes in the mean scores of S. mutans in salivary samples in coconut oil. Study shows that compared to the baseline there is a statistically significant decrease in the S. mutans level from the saliva samples taken on day 15 and day 30 (P < 0.001) using Wilcoxon Signed rank test.

Table 2.

Change in mean scores of S. mutans in salivary samples in group I

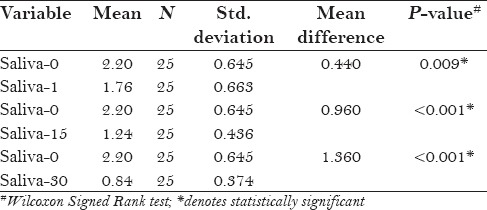

Changes in the mean scores of S. mutans in plaque samples in chlorhexidine are shown in Table 3. On day 15 and day 30, the mean difference was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.001) using Wilcoxon Signed rank test. There was a statistically significant (P < 0.001) reduction < 0.001) reduction of S. mutans in saliva from day 15, as shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Change in mean scores of S. mutans in plaque samples in group II

Table 4.

Change in mean scores of S. mutans in salivary samples in group II

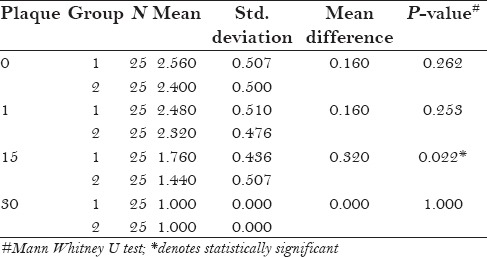

The mean scores of S. mutans in plaque between coconut oil group and chlorhexidine group were compared, as shown in Table 5. On day 15, the mean S. mutans score from plaque was 1.76 ± 0.436 in the coconut oil group and 1.440 ± 0.507 in the chlorhexidine group, which was found to be statistically significant (P = 0.022). Whereas on day 30, the mean S. mutans score from plaque in coconut oil group and chlorhexidine group was found to be statistically not significant (P = 1.000).

Table 5.

Comparison of mean scores of S. mutans in plaque between groups 1 and 2

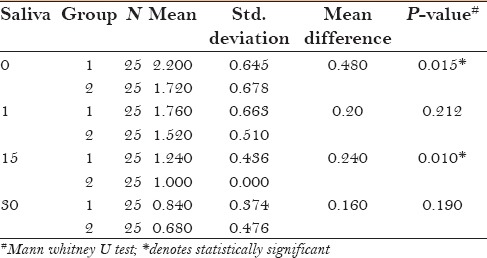

Table 6 shows the comparison of mean scores of S. mutans in saliva between coconut oil group and chlorhexidine group. On day 15, the mean S. mutans score from saliva was 1.24 ± 0.436 in group 1 and 1.00 ± 0.00 in group 2, the mean difference was 0.240, which was found to be statistically significant (P = 0.010) using Mann–Whitney U test. On day 30, the mean S. mutans score from saliva was found to be statistically not significant (P = 0.190).

Table 6.

Comparison of mean scores of S. mutans in saliva between groups 1 and 2

DISCUSSION

S. mutans considered as the most cariogenic of the oral microflora. It colonizes the tooth surfaces and produces significant amounts of extra and intracellular polysaccharides ans is responsible for the initial stage of oral biofilm formation and carious lesions.[12,13] Chemotherapeutic Chemotherapeutic agents can be used as an adjuvant in the reduction of S. mutans count.[14] In the present study In the present study, the results show that coconut oil is as effective as chlorhexidine in reducing the S. mutans count in the saliva and plaque.

Chlorhexidine is a potent chemotherapeutic agent considered to be the gold standard in the reduction of oral pathogens. Chlorhexidine readily binds to the charged bacterial surfaces and acts against gram positive and gram negative bacteria. The antibacterial action may also due to an increase in cellular membrane permeability followed by coagulation of the cytoplasmic macro molecules. It is representative of the cationic group that is highly effective against S. mutans infection. Its superior effect is due to the fact that it retains its antimicrobial effect as its remains adsorbed to the tooth surface even after its clearance from saliva.[14,15]

Coconut oil used in this study was commercially available for edible purposes. For oil pulling therapy, oil is gargled in the mouth and is moved between the teeth. The action of coconut oil is attributed to the emulsification, saponification, and antimicrobial action of contents action of coconut oil.

Studies using different oils by Thaweboon et al.[8] Asokan et al.,[16] Singla et al..[17] have shown than oil pulling can reduce the oral microorganisms especially S. mutans. However, the study by Jauhari et al.[18] showed no significant reduction in the bacterial counts.

Kaushik et al.[19] compared the saliva samples for S. mutans colonies count on participants using coconut oil, chlorhexidine, and distilled water for 15 days. A statistical reduction in S. mutans count was noted count was noted in coconut oil pulling and chlorhexidine group. The present study also showed statistically significant reduction in S. mutans count after 15 count after 15 and 30 days in both chlorhexidine and coconut oil group.

Studies by Peedikayil et al.[10]. showed coconut oil pulling could be an adjuvant procedure in decreasing plaque aggregation and plaque related gingivitis. Various hypotheses have been discussed on the mechanisms by which oil pulling may act in decreasing the plaque adhesion. The oil pulling exerts mechanical shear forces leading to its emulsification, thereby increasing the surface area of the oil. The oil film thus formed on the tooth surface can reduce plaque adhesion and bacterial aggregation. Studies have shown that coconut oil has a high saponification value, and is one of the most commonly used oil in making soaps. The soaps produced with coconut oil lather well and have an increased cleansing action. The alkalis in the saliva can also react with the oil leading to saponification and formation of a soap-like substance which leads to reduction in plaque adhesion.[19,20] The cleansing action and decreased plaque accumulation may be also due to the action of lauric acid in the coconut oil, which reacts with sodium hydroxide in saliva during oil pulling to form sodium laureate,[21] the main constituent of soap.

The antimicrobial effect of coconut oil was first reported by Hierholzer and Kabara.[22] Recent studies have shown that coconut oil has antimicrobial activity against various gram positive and gram negative organisms such as Escherichia vulneris, Enterococcer spp, Helicobater pylori, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus mutans, and Candia albicans.[23,24,25]

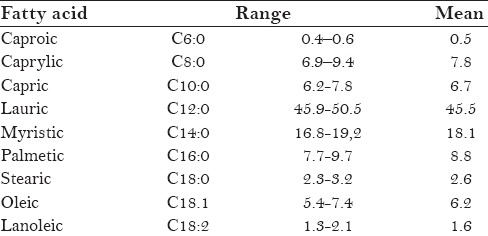

Coconut oil is a rich source of beneficial medium chain fatty acids (MCFAs), particularly, lauric acid, capric acid, caprylic acid, and caprioic acid [Table 7].[26] Electron microscopic Electron microscopic image showed that 15 minutes exposure to monolaurin, a monosaccharide present in coconut oil, caused cell shrinkage and cell disintegration of gram positive cocci.[27] The glycolipid compo The glycolipid compound sucrose monolaurate, a consitituent of coconut oil, has anticaries effect due to reduced glycolysis and sucrose oxidation in a noncompetitive manner on S. mutans, and thus preve, and thus prevents in vitro plaque.

Table 7.

Fatty acid composition of coconut oil (wt%)

Huang et al.[28] et al. studied the short-chain, medium-chain, and long-chain fatty acids which were specifically compared for their antimicrobial activity against S. mutans. The studies showed good antimicrobial activity at 25 μg/ml concentration. In ag/ml concentration. In another study by Huang et al.,[29], et al. medium chain trigl. medium chain triglycerides exhibited patterns of inhibition against oral microorganisms, with formic acid, capric acid, and lauric acid showing maximum bacterial inhibition.

Use of 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash exhibited mild staining of teeth in few participants, whereas no staining was observed in participants using coconut oil. Literature shows that long-term use of chlorhexidine alters taste sensation and produces brown staining on the teeth.[30]

Complications of oil Complications of oil pulling using sesame oil has been reported in the literature[31,32] No reports on adverse effects on coconut oil pulling has been reported. Coconut oil is commonly available in local market and is cheap when compared to other mouthwashes available in the market. Therefore, in coconut growing countries, coconut oil mouthwash can be a good alternative to 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the less number of participants examined. Minimum inhibitory concentration of the materials used also needs to be quantified in future studies. Future research with larger sample size and explaining the underlying mechanisms in detail are needed to shed more light for the use of coconut oil as a natural adjuvant for tooth brushing.

CONCLUSION

The study shows that coconut oil gargling is as effective as using chlorhexidine mouthwash. The combined effect of the emulsification, saponification, and the antimicrobial effects of medium chain triglycerides in coconut oil may be the reason for reduction of S. mutans.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Signoretto C, Burlacchini G, Faccioni F, Zanderigo M, Bozzola N, Canepari P. Support the role of Candida spp. in extensive caries lesions of children. New Microbiol. 2009;32:101–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krzyściak W, Jurczak A, Kościelniak D, Bystrowska B, Skalniak A. The virulence of Streptococcus mutans and the ability to form biofilms. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:499–515. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1993-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakade LS, Shah P, Shirol D. Comparison of antimicrobial efficacy of chlorhexidine and combination mouth rinse in reducing the Mutans streptococcus count in plaque. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2014;32:91–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.130780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asokan S. Oil pulling therapy. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:169. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.40476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hebbar A, Keluskar V, Shetti A. Oil pulling-Unravelling the path of mystic cure. J int Oral Health. 2010;2:11–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peedikayil FC, Sreenivasan P, Narayanan A. Oil pulling therapy and the role of coconut oil. EJOD. 2014;4:700–2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amith HV, Ankola AV, Nagesh L. Effect of oil pulling on plaque and gingivitis. J Oral Health Community Dent. 2007;1:12–18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thaweboon S, Nakaparksin J, Thaweboon B. Effect of Oil-Pulling on Oral Microorganisms in Biofilm Models. Asia J Public Health. 2011;2:62–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gbinigie O, Onakpoya I, Spencer E, McCall MacBain M, Heneghan C. Effect of oil pulling in promoting orodental hygiene: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Complement Ther Med. 2016;26:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peedikayil FC, Sreenivasan P, Narayanan A. Effect of coconut oil in plaque related gingivitis - A preliminary report. Niger Med J. 2015;56:143–7. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.153406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dayrit FM. The Properties of Lauric Acid and Their Significance in Coconut Oil. J Am Oil Chemists’oc. 2015;92:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkervold PR. Carranza's Clinical Periodontology. 12th ed. Elsevier, Saunders; 2014. p. 331. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marsh PD. Dental plaque: Biological significance of a biofilm and community life-style. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brecx M, Brownsfone E, MacDonald L, Gelskey S, Cheang M. Efficacy of Listerine®, Meridol® and chlorhexidine mouthrinses as supplements to regular tooth-cleaning measures. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:202–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb00640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hennessy T. Some antibacterial properties of chlorhexidine. J Periodont Res. 1973;8:61–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1973.tb02166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asokan S1, Rathan J, Muthu MS, Rathna PV, Emmadi P, Raghuraman, et al. Effect of oil pull. Effect of oil pulling on Streptococcus mutans count in plaque and saliva using Dentocult SM Strip mutans test: A randomized, controlled, triple-blind study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2008;26:12–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.40315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singla N, Acharya S, Martena S, Singla R. Effect of oil gum massage therapy on common pathogenic oral microorganisms - A randomized controlled trial. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18:441–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.138681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jauhari D, Srivastava N, Rana V, Chandna P. Comparative Evaluation of the Effects of Fluoride Mouthrinse, Herbal Mouthrinse and Oil Pulling on the Caries Activity and Streptococcus mutans Count using Oratest and Dentocult SM Strip Mutans Kit. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2015;8:114–8. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaushik M, Reddy P, Sharma R, Udameshi P, Mehra N, Marwaha A. The Effect of Coconut Oil pulling on Streptococcus mutans Count in Saliva in Comparison with Chlorhexidine Mouthwash. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2016;17:38–41. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alsberg CL, Taylor AE. The Fats and Oils - A General Overview (Fats and Oils Studies No. 1) Stanford University Press; 1928. [Last accessed on 2016 Mar 20]. p. 86. Available from http://journeytoforever.org/biofuel_library/fatsoils/fatsoils2.html . [Google Scholar]

- 21.PaviaDL, Lampman GM, Kriz GS, Engel RG. Introduction to Organic Laboratory Techniques: A Small Scale Approach. Brooks/Cole Laboratory series for organic chemistry. 2004:252–65. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hierholzer JC, Kabara JJ. In vitro effects of monolaurin compounds on enveloped RNA and DNA viruses. J Food Safety. 1982;4:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4565.1982.tb00429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shino B, Peedikayil FC, Jaiprakash SR, Bijapur GA, Kottayi S, Jose D. Comparison of Antimicrobial Activity of Chlorhexidine, Coconut Oil, Probiotics, and Ketoconazole on Candida albicans Isolated in Children with Early Childhood Caries: An In Vitro Study. Scientifi Study. Scientifica 2016. 2016:7061587. doi: 10.1155/2016/7061587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verallo-Rowell VM, Dillague KM, Syah-Tjundawan BS. Novel antibacterial and emollient effects of coconut and virgin olive oils in adult atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2008;19:308–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sado Kamdem S, Guerzoni ME, Baranyi J, Pin C. Effect of capric, lauric and α-linolenic acids on the division time distributions of single cells of Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;128:122–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossel JB. Fractionaation of lauric oils. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1985;62:385–90. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandal MD, Mandal S. Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.: Arecaceae): In health promotion and disease prevention. Asian Pacific J of Tropical Med. 2011;4:241–7. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang CB, George B, Ebersole JL. Antimicrobial activity of n-6, n-7 and n-9 fatty acids and their esters for oral microorganisms. Arch Oral Biol. 2010;55:555–60. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang CB, Altimova Y, Myers TM, Ebersole JL. Short- and medium-chain fatty acids exhibit antimicrobial activity for oral microorganisms. Arch Oral Biol. 2011;56:650–4. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eslami N, Ahrari F, Rajabi O, Zamani R. The staining effect of different mouthwashes containing nanoparticles on dental enamel. J Clin Exp Dent. 2015;7:e457–61. doi: 10.4317/jced.52199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim JY, Jung JW, Choi JC, Shin JW, Park IW, Choi BW, et al. Recurrent lipoid p Recurrent lipoid pneumonia associated with oil pulling. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18:251–2. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuroyama M, Kagawa H, Kitada S, Maekura R, Mori M, Hirano H. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia caused by repeated sesame oil pulling: A report of two cases. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15:135. doi: 10.1186/s12890-015-0134-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]