Abstract

The performances of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) risk calculator and other risk calculators for prostate cancer (PCa) prediction in Chinese populations were poorly understood. We performed this study to build risk calculators (Huashan risk calculators) based on Chinese population and validated the performance of prostate-specific antigen (PSA), PCPT risk calculator, and Huashan risk calculators in a validation cohort. We built Huashan risk calculators based on data from 1059 men who underwent initial prostate biopsy from January 2006 to December 2010 in a training cohort. Then, we validated the performance of PSA, PCPT risk calculator, and Huashan risk calculators in an observational validation study from January 2011 to December 2014. All necessary clinical information were collected before the biopsy. The results showed that Huashan risk calculators 1 and 2 outperformed the PCPT risk calculator for predicting PCa in both entire training cohort and stratified population (with PSA from 2.0 ng ml−1 to 20.0 ng m). In the validation study, Huashan risk calculator 1 still outperformed the PCPT risk calculator in the entire validation cohort (0.849 vs 0.779 in area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [AUC] and stratified population. A considerable reduction of unnecessary biopsies (approximately 30%) was also observed when the Huashan risk calculators were used. Thus, we believe that the Huashan risk calculators (especially Huashan risk calculator 1) may have added value for predicting PCa in Chinese population. However, these results still needed further evaluation in larger populations.

Keywords: biopsy, China, prostate cancer, prostate-specific antigen, risk calculator

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most common cancer and one of the leading causes of death among men worldwide.1 The incidence of PCa in China is relatively low compared with Western countries; however, it has been progressively rising in recent decades.2

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is the most widely used biomarker for prostate cancer screening and early detection of PCa. However, its relatively low specificity has resulted in large number of unnecessary biopsies.3 To solve this problem, several independent factors have been considered for predicting PCa, for example, age, results from digital rectal exam (DRE), and several PSA derivatives such as ratio of free to total PSA (%fPSA), PSA density (PSAD), and PSA velocity (PSAV).4 In some studies, prediction tools (such as nomograms and risk calculators) were based on these factors, which might provide added value to PSA testing for predicting PCa or high-grade PCa. Among those prediction tools, the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) risk calculator and the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) risk calculator were most widely used in Western populations. The PCPT reported a risk calculator that was built based on age, race, PSA, digital rectal examination (DRE), family history, and history of a previous negative prostate biopsy. It was reported that use of the PCPT risk calculator can avoid 1% and 2% of unnecessary biopsies if a threshold probability of 20% and 30% is used for patients with PSA from 0.5 to 50 ng ml−1, respectively. ERSPC risk calculator included PSA, DRE, transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) findings, and prostate volume (PV). It was reported that use of ERSPC risk calculator can avoid 9% and 23% of unnecessary biopsies if a threshold probability of 20% and 30% is used for patients with PSA from 0.5 to 50 ng ml−1, respectively.5 The utility of these risk calculators had been externally validated in Western populations and observed to outperform PSA and %fPSA for predicting PCa.6,7,8

However, limited data on the performance of PCa risk calculators had been reported in Chinese populations. Since PCPT and ERSPC risk calculators were based on screening populations (most participants in PCPT had PSA below 6.0 ng ml−1 and participants in ERSPC had a mean PSA of 1.7 ng ml−1),9,10 they would not be appropriate for clinical-based populations in China. In addition, a lack of information on family history (due to the inadequate healthcare policy in the past decades) and different ancestry (Han race in China vs Caucasian or African-American in Western countries) could also limit the effectiveness of those risk calculators. In this study, we used a training cohort to build risk calculators (Huashan risk calculators) based on the Chinese population, followed by a prospective observational study to validate the performance of our risk calculators. We also compared the performance of PSA, PCPT risk calculator, and Huashan risk calculators in both substudies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

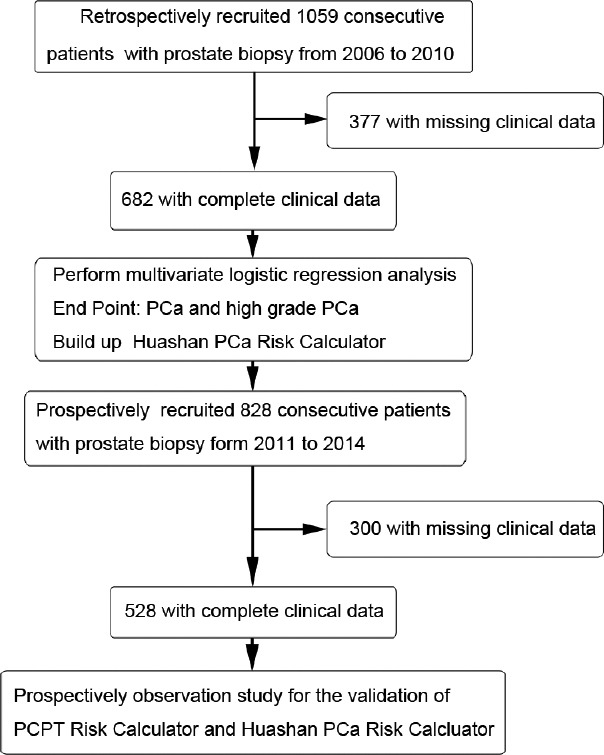

The complete study design is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study population and study design.

Population of the training study

All men (n = 1059) who underwent initial prostate biopsy from January 2006 to December 2010 in Huashan Hospital were recruited in the training cohort. All the clinical information were collected before biopsy. The patients were excluded if any essential clinical data on age, PSA, %fPSA, PV, DRE result, or TRUS result were missing. The characteristics of tertiary health institutes in China were described in our previous study.11

Population of the validation study

Patients (n = 828) who underwent initial prostate biopsy from January 2011 to December 2014 were consecutively enrolled in our prospective, observational validation study. Participants who completed all the examinations (PSA, fPSA, DRE, and TRUS) before biopsy were included in the final analysis. All the clinical data were collected and entered into the Huashan Risk calculators to generate the Huashan Risk Index. In the validation study, the Huashan Risk index did not influence the decision-making of prostate biopsy. In both training and validation studies, all men underwent an ultrasound-guided transperineal needle prostate biopsy with 6-core before October 2007 or 10-core thereafter. The indications for prostate biopsy at our institute were the following: (1) tPSA >4.0 ng ml−1, (2) tPSA <4.0 ng ml−1 with suspicious fPSA/tPSA <0.16 or PSA density >0.15 (PSAD = tPSA/PV, PV (ml) = height (cm) × length (cm) × width (cm) × 0.52), (3) positive findings from a digital rectal exam (DRE) with any level of tPSA, and (4) positive findings from imaging techniques such as transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with any level of tPSA.

Sample collection

All specimens were diagnosed by the same group of pathologists from the Pathology Department of Huashan Hospital. All blood samples were collected before biopsy and were measured by the Department of Clinical Laboratory for tPSA and fPSA. The protocol of the current study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China. Both written and verbal informed consent were obtained from patients for their participation in the study.

Statistical analysis

Based on our former studies, we built two risk calculators in the training cohort (n = 1059) from 2006 to 2010.11 Risk calculator 1 (RC1) was built according to the rules of a logistic regression model based on age, result of DRE, PV, logPSA (logarithm of PSA), %fPSA, and TRUS result. Risk calculator 2 (RC2) was built according to the rules of a logistic regression model based on age, result of DRE, logPSA (logarithm of PSA), and %fPSA. The dichotomous variables (TRUS and DRE results) were considered as 1 for positive and 0 for negative in the risk calculators. Then, we evaluated the performances of PSA, PCPT risk calculator, and Huashan RC1 and RC2 for predicting PCa and high-grade PCa in the training cohort, the validation cohort and their subgroups (e.g., population with PSA ranging from 2.0 ng ml−1 to 20.0 ng ml−1 and population with PSA ranging from 2.0 ng ml−1 to 10.0 ng ml−1).

In the current study, the PCPT risk calculation was performed using the available formula.9 PSA was also used as a reference prediction tool in our analysis. The high-grade PCa was defined as PCa with a Gleason Score ≥8 according to the Chinese Urological Association (CUA) guideline.12 Evaluation of the PCPT risk calculator was excluded in high-grade PCa in the criteria for high-grade PCa in the CUA guidelines12 and EAU (European Association of Urology) guidelines. Since the epidemiological database was not well established in China, the risk factor of family history in PCPT risk calculator was ignored in the analysis. The baseline characteristics (age, prostate volume, logPSA, and %fPSA) between two cohorts were compared using t-test for continuous variables or Chi-squared test for categorical variables (DRE result, TRUS result, and PCa detection rate under 6- or 10-core). Z-test was performed to evaluate the differences among area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUCs) of the two risk calculators, PCPT risk calculator and PSA. Two-sided test with P = 0.05 was used. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 (Statistical Product and Service Solutions, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

A total of 1059 patients were included in the training study and 828 patients were included in the validation study.

Training study

The characteristics of the study population and the stratified subgroups (PSA ranging from 2.0 ng ml−1 to 20.0 ng ml−1) are shown in Supplementary Table 1 (1.4MB, tif) . In the training cohort and its subgroup with PSA ranging from 2.0 ng ml−1 to 20.0 ng ml−1, the mean age, logPSA, and positive rates of DRE result and TRUS result were statistically higher in men diagnosed with PCa than in men without PCa whereas the mean PV and %fPSA were lower in PCa group (all P < 0.05). When the patients were categorized by Gleason Score ≥8 as high-grade PCa and others, the differences in age, PV, and %fPSA became less significant or nonsignificant in two groups, whereas the differences in logPSA, positive rates of DRE results and TRUS results remained significant.

Clinical characteristics of the training cohort†

Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate each factor in the training cohort. We observed that age, DRE result, TRUS result, PV, PSA, and %fPSA were still associated with PCa and high-grade PCa (all had P < 0.05). On the basis of the results from the logistic regression analysis and the consensus risk factors (e.g., age, DRE result, TRUS result, PV, PSA, and %fPSA), we constructed the Huashan risk calculators as follows:

-

(i)

Huashan risk calculator I (RC 1) for PCa: risk points = −7.552 + 0.05 × age + 1.636 × DRE − 0.035 × PV + 3.675 × logPSA − 0.02× %fPSA + 1.137 × TRUS

-

(ii)

Huashan risk calculator I (RC 1) for high-grade PCa: risk points = −4.041 − 0.006 × age + 0.455 × DRE + 1.325 × logPSA + 0.008× %fPSA − 0.013 × PV + 1.513 × TRUS

-

(iii)

Huashan risk calculator II (RC 2) for PCa: risk points = −7.983 + 0.051 × age + 2.333 × DRE + 3.146 × logPSA − 0.047× %fPSA

-

(iv)

Huashan risk calculator II (RC 2) for high-grade PCa: risk points = −4.417 + 0.004 × age + 1.055 × DRE + 1.252 × logPSA + 0.009× %fPSA.

In further analysis, the prediction accuracy of PSA, PCPT risk calculator, and Huashan risk calculators were evaluated in the training cohort. The area under the receiver operating curves (AUCs) of the different PCa risk calculators in the training cohorts and its subgroup are shown in Supplementary Table 2 (1MB, tif) . In the training cohort and its subgroup, when predicting PCa, the AUCs of RC 1 and RC 2 were 0.926 and 0.901, respectively, which indicated that both performed better than the PCPT risk calculator (AUC = 0.860) (P < 0.05). Similar results were also observed in patients with PSA ranging from 2.0 to 10.0 ng ml−1 in the training cohort (Supplementary Table 3 (245.3KB, tif) ). When predicting high-grade PCa (a Gleason score ≥8), there was no significant difference among the AUCs of PSA (AUC = 0.781), RC 1 (AUC = 0.838), and RC 2 (AUC = 0.814) in the training cohort.

Evaluation of the area under the receiver operating curves (AUCs) of different PCa risk calculators

Evaluation of the area under the curves (AUCs) of different PCa risk calculators

Validation study

In the subsequent validation study, we evaluated the performance of the Huashan risk calculators in a prospective cohort. The characteristics of the validation cohort and its subgroup (PSA ranging from 2.0 ng ml−1 to 20.0 ng ml−1) are shown in Supplementary Table 4 (964.8KB, tif) . In this cohort and its subgroup, the baseline characteristics were consistent with those of the training group.

Clinical characteristics of the validation cohort†

When we evaluated the prediction abilities of the risk calculators in the validation cohort and its subgroup, RC 1 outperformed the PCPT risk calculator (0.849 vs 0.779 in the whole validation cohort and 0.765 vs 0.663 in its subgroup) whereas no significant difference in the AUCs was observed between the PCPT risk calculator and RC 2 in predicting PCa. Similar results were also observed in patients with PSA that ranged from 2.0 to 10.0 ng ml−1 in the validation cohort (Supplementary Table 3 (245.3KB, tif) ). When predicting high-grade PCa, there was no significant difference among the AUCs of PSA (AUC = 0.879), RC 1 (AUC = 0.855), and RC 2 (AUC = 0.886) in the entire validation cohort.

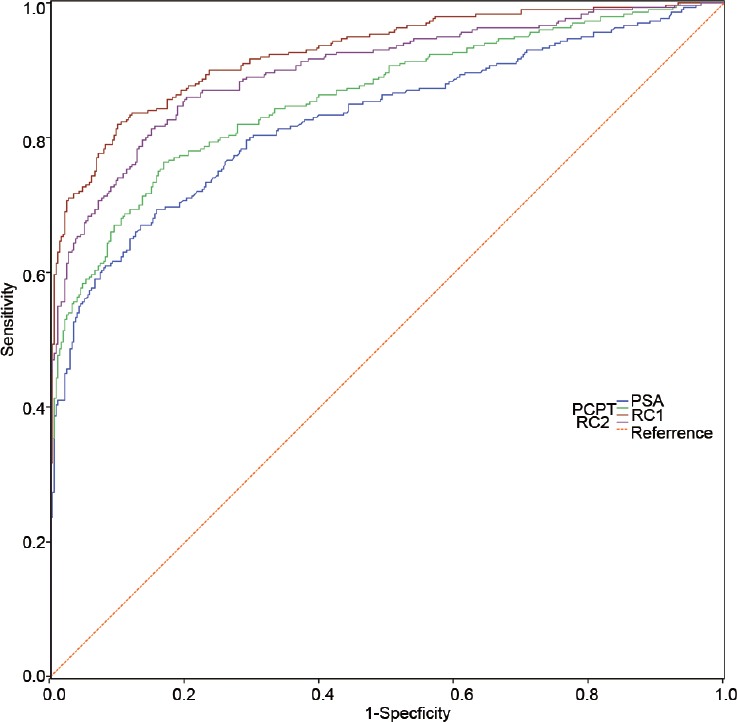

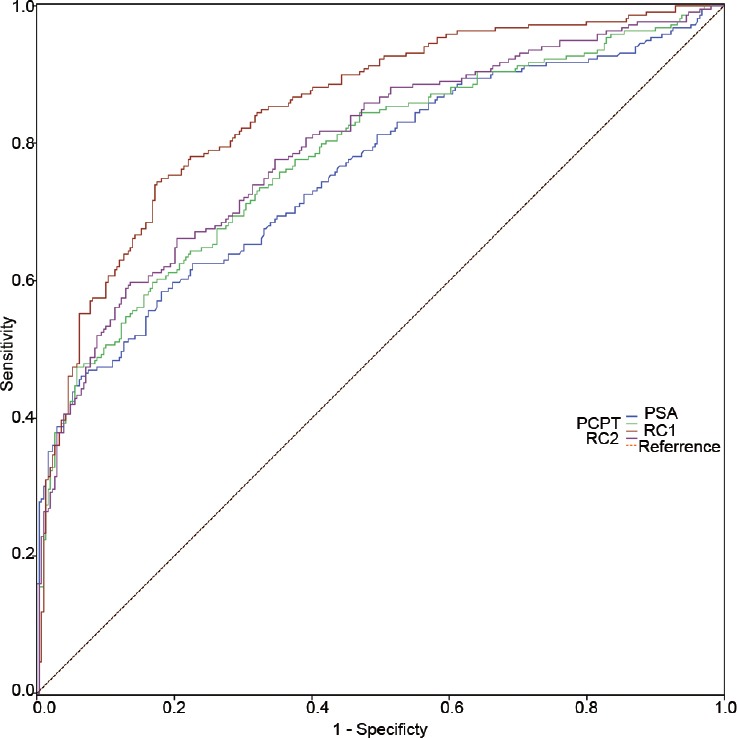

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of PSA, PCPT risk calculator, RC 1, and RC 2 in predicting PCa in two cohorts are shown in Figures 2 and 3. The ROC curves of the RCs in predicting PCa in the subgroups with PSA ranged from 2.0 ng ml−1 to 20.0 ng ml−1 are provided in Supplementary Figures 1 (504.1KB, tif) and 2 (502.9KB, tif) .

Figure 2.

The ROC curves of PSA, PCPT risk calculator, RC 1, and RC 2 in predicting PCa in the training cohort. ROC: receiver operating characteristic; PCa: prostate cancer.

Figure 3.

The ROC curves of PSA, PCPT risk calculator, RC 1, and RC 2 in predicting PCa in the validation cohort. ROC: receiver operating characteristic; PCa: prostate cancer.

The ROC curves of PSA, PCPT risk calculator, RC 1, and RC 2 in predicting PCa in the subgroups of training cohort with PSA ranged from 2.0 ng ml−1 to 20.0 ng ml−1. ROC: receiver operating characteristic; PCa: prostate cancer.

The ROC curves of PSA, PCPT risk calculator, RC 1, and RC 2 in predicting PCa in the subgroups of the validation cohort with PSA ranged from 2.0 ng ml−1 to 20.0 ng ml−1. ROC: receiver operating characteristic; PCa: prostate cancer.

We also evaluated the reduction of biopsy cases using different PCa risk calculators compared with using PSA only (Supplementary Table 5 (205.7KB, tif) ). For instance, with a sensitivity of 80%, the PCPT risk calculator, RC 1, and RC 2 could spare 6.67%, 22.74%, and 18.60%, respectively, of the patients in the training cohort who did not have PCa from undergoing unnecessary procedures. For patients in the validation cohort, the PCPT risk calculator, RC 1, and RC 2 at a sensitivity of 80% could spare 25.60%, 29.67%, and 16.94%, respectively, of unnecessary biopsies.

Number of biopsies reduced by different PCa risk calculators comparing with PSA

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to build a risk calculator based on Chinese patients who underwent prostate biopsy. First, we performed univariate and multivariate analyses in a retrospective training cohort and built the Huashan risk calculators (RC 1 and RC 2). We found that the Huashan risk calculators (especially RC 1) performed better than the PCPT risk calculator and PSA alone for predicting PCa. Second, we validated the Huashan risk calculators in a prospective, observational study. We found that RC 1 performed better than the PCPT risk calculator in the validation cohort as well. Finally, we evaluated the reduction rate of biopsy using risk calculators and found that RC 1 still had added value on avoiding unnecessary biopsies.

The goal of PCa screening is to identify the presence of curable disease while minimizing unnecessary biopsies. Using PSA and other clinical information at the time of screening, it is possible to predict the risk of PCa more precisely than using PSA alone. Thus, several PCa risk calculators had been developed in several studies and validated in a variety of populations (e.g., non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, and African Americans).

The two most widely used risk calculators are the PCPT risk calculator and ERSPC risk calculator 3. A recent meta-analysis showed that the summary AUC of the PCPT risk calculator was 0.66 (95% CI: 0.62–0.70) and the AUC of the ERSPC RC 3 was 0.79 (95% CI: 0.77–0.81). In the initial screening, the PCPT risk calculator was slightly better than PSA at predicting PCa whereas ERSPC was much better.13

In the current study, our risk calculators were based on available information without any further invasive procedures. The PCPT risk calculator included the variables of PSA, family history of prostate cancer, DRE, a prior negative prostate biopsy, race, and age. It had been previously evaluated in Western populations and a Chinese population, and it was widely recognized. The AUCs of the PCPT risk calculator in the Western populations ranged from 0.57 to 0.69, and the AUC was higher (0.78) in the Chinese population.6,7,8,14 However, the incompleteness of epidemiologic data in China was incomplete in the past decades due to ineffective health-care policies might have weakened the utility of the PCPT risk calculator (which uses race and family history) for predicting PCa in the Chinese population. Thus, we attempted to improve the PCa risk calculator for Chinese population. For the ERSPC risk calculator 3, the variable of age was not included. While age is considered an important risk factor for PCa and has been evaluated in several studies in both Western and Chinese populations,15,16,17,18 we included age in our risk calculators. Moreover, the characteristics of the cohorts in the current study were different from the PCPT risk calculator cohort, particularly with respect to the inclusion in the initial study cohort (all the participants in this study had indications for prostate biopsy, whereas the participants in PCPT had PSA ≤3.0 ng ml−1) and biopsy cores (most of the participants in this study underwent the 10-core biopsy whereas 80% of the participants in PCPT underwent the 6-core biopsy). Since there is no PSA screening in the Chinese population due to the large population and social burden, we decided that the PCa risk calculator should be tailored more to a biopsy population than to a screening population.

Overall, in both training cohort and validation cohort, the overall positive detection rate of PCa was approximately 45%, which was higher than that in Western screening populations.5,6 The AUCs of PSA in the training and validation cohorts were 0.827 and 0.757, respectively, which were relatively high compared with Western studies (slightly above 0.5). This finding might be attributable to the fact that the current study was based on a biopsy population at higher risk for PCa. For example, some of the patients came to the urology department because of elevated PSA while others seeking help for their urinary symptoms.

Our results showed that RC 1, which included age, result of DRE, PV, PSA (logarithm of PSA), %fPSA, and TRUS result, performed best among three risk calculators. This may be due to the fact that RC 1 considered both prostate volume and TRUS results. Thus, our results implied that TRUS might be a useful diagnostic tool in predicting PCa in the Chinese population and that it had its value in helping both patients and urologists make the decision as to whether to perform a prostate biopsy in China.

In the stratification analysis, the positive rate of PCa in the patients with PSA ranged from 2.0 to 20.0 ng ml−1 was approximately 23%–31%, which was comparable to the positive rate in Caucasian populations with PSA ranged from 2.0 to 10.0 ng ml−1.19,20 Other studies have also shown that the PCa positive rate in the Chinese biopsy population with PSA ranging from 4.0 to 10.0 ng ml−1 was approximately 20%, which was lower than the percentage reported in the Western population.11,21,22 Therefore, in this study, we performed subgroup analysis in patients with PSA in the range of 2.0-20.0 ng ml−1 to determine whether the PCPT risk calculator and our risk calculators could improve the PCa prediction ability. The results showed that RC 1 outperformed the PCPT risk calculator in the subgroup analysis whereas RC 2 did not. In addition, we evaluated the AUCs of different PCa risk calculators in the subgroups with PSA in the range of 2.0–10.0 ng ml−1 (the Western gray zone), and the result remained the same.

In addition, compared with using PSA alone, we demonstrated that using RC 1 led to a reduction in the number of unnecessary biopsies by at least 20% while maintaining a sensitivity of 80%. While maintaining a sensitivity of 90%, the reduction was as much as 50% and 38% in the training and validation cohorts, respectively. This finding indicated that urologists could reduce a proportion of unnecessary biopsies by adding the needed clinical variables into their consideration. This approach could both relieve the socioeconomic burden and avoid unnecessary invasive procedures.

In our study, the Huashan risk calculator 1 provided an index that ranked from−3 to 4. According to our data, if a patient with Huashan risk calculator index of ≤−2 undergoes a prostate biopsy, the positive rate will be <10%. When a patient has Huashan risk calculator index of ≥2, the risk of PCa is 80%–90%. For high-grade PCa risk calculator, if a patient with a Huashan risk calculator index of ≤−4 undergoes prostate biopsy, the positive rate of the high-grade PCa will be <10%. When a patient has Huashan risk calculator index of ≥−1, the risk of high-grade PCa will be 70%–90% (Data were not shown in the results). These estimates indicated that our risk calculators could provide an intuitive means of using the data to help patients.

The current study had several strengths: (i) we built two logistical models based on a biopsy population, and we validated two RCs and the PCPT risk calculator in a subsequent biopsy population; this approach implied that this was a retrospective and prospective study; (ii) a contemporary standard 10-core biopsy was used in most of the training cohort and the whole validation cohort; (iii) indications for prostate biopsy were based on the current Chinese guidelines without research inclusion criteria; and (iv) because TRUS is widely used in China to help urologists make the decision as to whether to biopsy, we included the PV and TRUS results in RC 1 to determine whether TRUS really works. However, there were several limitations in our study. First, the study population was from a single tertiary health institute which could lead to selection bias. Nevertheless, as we mentioned above, tertiary health institutes in China, receive patients from all over the country. Therefore, our study population could be partially representative of the Chinese population. Second, the study population was at relatively high risk for PCa as we noted above, and thus the risk calculator might be more applicable to other biopsy populations rather than to screening populations. Third, the use of a different definition of high-grade PCa in the Chinese guidelines might restrict the application of the risk calculators for predicting high-grade PCa in other populations. Fourth, the performance of ERSPC RC 3 was not tested in the current study for lack of formulae. Since ERSPC risk calculator is also a logistic regression based risk calculator and is known to perform better than PCPT risk calculator, it might perform equivalent to the Huashan risk calculators. Although the Huashan risk calculators were more tailored to a Chinese biopsy population with relatively high risk, it still required further refinement and validation.

In future study, we first intend to enlarge the sample size of the cohort and conduct a multicenter study. Second, we will modify the formulas of our risk calculators in the enlarged training population to make it more accurate and stable. Third, we will validate the risk calculators in other populations from the joint center and community. If the risk calculators truly work, we will build a website or an app and recommend that urologists use it to assess their patients before prostate biopsy.

CONCLUSION

The Huashan risk calculators might have added value for predicting PCa in the Chinese population; it also resulted in a considerable reduction in unnecessary biopsies for PCa while missing only a few cases. However, it requires further evaluation in larger populations.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

YSW, RN, QD, JFX, and YHS conceived and designed the study. YSW, SHL, NZ, YHC, and HWJ performed the experiments. YSW, RN analyzed the data. PDB, SJT, LMZ, and MBH contributed materials and analysis tools. YSW, NZ, and SHL wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

All authors declared no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the people who took part in this study. This study was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81272835 and No. 81402339) and the Clinical Science and Technology Innovation Project of Shanghai Shen Kang Hospital Development Center (No. SHDC12015105).

Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the study on the Asian Journal of Andrology website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu M, Wang JY, Zhang YG, Zhu SC, Lu ZH, et al. [Detection of urological and male genital tumors diagnosed in Beijing hospital 1995-2004] Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2007;87:2423–5. [Article in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loeb S, Bjurlin MA, Nicholson J, Tammela TL, Penson DF, et al. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65:1046–55. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.12.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gann PH, Ma J, Catalona WJ, Stampfer MJ. Strategies combining total and percent free prostate specific antigen for detecting prostate cancer: a prospective evaluation. J Urol. 2002;167:2427–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavadas V, Osorio L, Sabell F, Teves F, Branco F, et al. Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial and European randomized study of screening for prostate cancer risk calculators: a performance comparison in a contemporary screened cohort. Eur Urol. 2010;58:551–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parekh DJ, Ankerst DP, Higgins BA, Hernandez J, Canby-Hagino E, et al. External validation of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial risk calculator in a screened population. Urology. 2006;68:1152–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eyre SJ, Ankerst DP, Wei JT, Nair PV, Regan MM, et al. Validation in a multiple urology practice cohort of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial calculator for predicting prostate cancer detection. J Urol. 2009;182:2653–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guyen CT, Yu C, Moussa A, Kattan MW, Jones JS. Performance of Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial risk calculator in a contemporary cohort screened for prostate cancer and diagnosed by extended prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2010;183:529–33. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson IM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. Assessing prostate cancer risk: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:529–34. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roobol MJ, Zhu X, Schroder FH, van Leenders GJ, van Schaik RH, et al. A calculator for prostate cancer risk 4 years after an initially negative screen: findings from ERSPC Rotterdam. Eur Urol. 2013;63:627–33. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Na R, Jiang H, Kim ST, Wu Y, Tong S, et al. Outcomes and trends of prostate biopsy for prostate cancer in Chinese men from 2003 to 2011. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Na Y, Sun Y, Cao D, Gao X, Hu Z, et al. Prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment guidelines. In: Na Y, Ye Z, Sun Y, Sun G, Huang J, et al., editors. Chinese Urological Association Guidelines. 2014th ed. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House; 2014. pp. 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louie KS, Seigneurin A, Cathcart P, Sasieni P. Do prostate cancer risk models improve the predictive accuracy of PSA screening? A meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:848–64. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu Y, Wang JY, Shen YJ, Dai B, Ma CG, et al. External validation of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial and the European randomized study of screening for prostate cancer risk calculators in a Chinese cohort. Asian J Androl. 2012;14:738–44. doi: 10.1038/aja.2012.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan TO, Jacobsen SJ, McCarthy WF, Jacobson DJ, McLeod DG, et al. Age-specific reference ranges for prostate-specific antigen in black men. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:304–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608013350502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lein M, Koenig F, Jung K, McGovern FJ, Skates SJ, et al. The percentage of free prostate specific antigen is an age-independent tumour marker for prostate cancer: establishment of reference ranges in a large population of healthy men. Br J Urol. 1998;82:231–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kao CH. Age-related free PSA, total PSA and free PSA/total PSA ratios: establishment of reference ranges in Chinese males. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:1361–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Na R, Wu Y, Xu J, Jiang H, Ding Q. Age-specific prostate specific antigen cutoffs for guiding biopsy decision in Chinese population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruno JJ, 2nd, Armenakas NA, Fracchia JA. Influence of prostate volume and percent free prostate specific antigen on prostate cancer detection in men with a total prostate specific antigen of 2.6 to 10.0 ng/ml. J Urol. 2007;177:1741–4. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vickers AJ, Sjoberg DD, Ankerst DP, Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, et al. The Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial risk calculator and the relationship between prostate-specific antigen and biopsy outcome. Cancer. 2013;119:3007–11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng XY, Xie LP, Wang YY, Ding W, Yang K, et al. The use of prostate specific antigen (PSA) density in detecting prostate cancer in Chinese men with PSA levels of 4-10 ng/mL. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:1207–10. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang P, Du W, Xie K, Deng X, Fu J, et al. Transition zone PSA density improves the prostate cancer detection rate both in PSA 4.0-10.0 and 10.1-20.0 ng/ml in Chinese men. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:744–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Clinical characteristics of the training cohort†

Evaluation of the area under the receiver operating curves (AUCs) of different PCa risk calculators

Evaluation of the area under the curves (AUCs) of different PCa risk calculators

Clinical characteristics of the validation cohort†

The ROC curves of PSA, PCPT risk calculator, RC 1, and RC 2 in predicting PCa in the subgroups of training cohort with PSA ranged from 2.0 ng ml−1 to 20.0 ng ml−1. ROC: receiver operating characteristic; PCa: prostate cancer.

The ROC curves of PSA, PCPT risk calculator, RC 1, and RC 2 in predicting PCa in the subgroups of the validation cohort with PSA ranged from 2.0 ng ml−1 to 20.0 ng ml−1. ROC: receiver operating characteristic; PCa: prostate cancer.

Number of biopsies reduced by different PCa risk calculators comparing with PSA