Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine whether the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), a measure of the systemic inflammatory response is associated with the overall prostate cancer detection rate in men who underwent contemporary multi (≥12)-core transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) biopsy. We reviewed the records of 3913 patients with initial prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels ranging from 4 to 10 ng ml−1 who underwent TRUS-guided prostate biopsy between April 2006 and May 2014. NLR was calculated by prebiopsy neutrophil and lymphocyte counts. We excluded patients who had evidence of acute prostatitis, a history of prostate surgery, and any systemic inflammatory disease. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to analyze prostate cancer detection. After adjusting for confounding factors, predictive values were determined according to the receiver operating characteristic-derived area under the curve, both including and excluding the NLR variable. In univariate analyses, NLR was a significant predictor of prostate cancer detection (P < 0.001). In multivariate analyses, a higher NLR was significantly associated with prostate cancer detection after adjusting for other factors (OR = 1.372, P = 0.038). The addition of NLR increased the accuracy from 0.712 to 0.725 (P = 0.005) in the multivariate model for prostate cancer detection. NLR may be a potentially useful clinical marker in the detection of prostate cancer among men with a PSA level in the 4–10 ng ml−1 range. These findings are derived from a retrospective analysis and should be validated in larger populations through prospective studies.

Keywords: inflammation, lymphocyte, neutrophil, prostate biopsy, prostate cancre

INTRODUCTION

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is secreted from prostate luminal cells, and the serum PSA level is a useful tool for detecting prostate cancer. After detecting elevated PSA levels, it is recommended that patients undergo a prostate biopsy, which is the only method currently available to confirm the diagnosis of prostate cancer. A significant percentage of men with an elevated PSA level >4 ng ml−1 who undergo an invasive prostate biopsy does not have prostate cancer1 as PSA lacks sufficient sensitivity and specificity for detecting prostate cancer.2 Furthermore, an invasive prostate biopsy may miss cancer in some men, given that up to 20% of men will have prostate cancer in a repeat biopsy.3

Systemic inflammation plays a role in the development and progression of cancer, and many epidemiological studies associate inflammatory markers, including the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) with many different types of cancer, including lung, colorectal, pancreatic, and ovarian cancers.4,5,6 NLR, which combines circulating neutrophil and lymphocyte counts, is one of the most common indicators of inflammation in cancer patients and has been reported to be significantly correlated with clinical outcomes in several types of cancer.7,8,9 In the last few years, increasing evidence has indicated that cancer development and progression depend on complex interactions between tumor and host factors, including the systemic inflammatory response.10,11 These host factors appear to be linked; e.g., patients with elevated C-reactive protein levels demonstrated increased weight loss and poor performance status. This finding suggests that systemic inflammation may be an important etiological factor for the nutritional and functional decline of patients during cancer development and progression.10,12

Although some histopathological, clinical, and epidemiological evidence suggests that chronic inflammation plays a role in prostate carcinogenesis, an association between inflammatory markers and the overall detection rate of prostate cancer remains controversial.13,14 A recent analysis demonstrated a positive association between prediagnostic circulating markers of inflammation and an increased risk of prostate cancer.15 Another report, however, suggested that low serum neutrophil count may be a positive predictor of prostate cancer detection during transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided biopsy.1 We, therefore, formed hypothesis that there was significant association between prebiopsy NLR and prostate cancer detection rate among men who underwent TRUS-guided biopsy. The study participants included Korean men who had PSA levels between 4 and 10 ng ml−1 and subsequently underwent prostate biopsy via the contemporary multi (≥12)-core approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After obtaining the approval of the Institutional Review Board at the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB No.: B-1406/202–111), we reviewed the records of men who underwent multi (≥12)-core TRUS-guided biopsy of their prostates at our institution. All data were analyzed anonymously. All men underwent TRUS prostate biopsies secondary to either elevated PSA levels, abnormal digital rectal exams (DREs), or hypoechoic lesions (as detected by TRUS). In all men, the prostate was routinely biopsied bilaterally near the base, mid-gland region, and apex, taking at least six biopsies per side. If necessary, additional biopsies were obtained to evaluate further suspicious lesions.

A total of 4335 men who underwent TRUS-guided biopsy between April 2006 and May 2014 and initial PSA levels of 4 to 10 ng ml−1 were enrolled. We excluded the patients who underwent biopsy prior to the implementation of the 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) modification of the Gleason scoring system.16 Among them, men who had evidence of acute prostatitis (n = 11), who had undergone prior biopsies at other institutions (n = 122), or had previous prostate surgery before receiving a biopsy at our institution (n = 14) were excluded from the study. And we excluded the patients who had medically active illness (n = 24), history of systemic inflammatory diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet disease, sarcoidosis, Sjógren syndrome, etc., (n = 19) and medicine history of anti-inflammatory drug history (n = 211). Also, patients were excluded if relevant data, including NLR, were missing (n = 21). For subjects who underwent more than one prostate biopsy at our institution, only data from the initial biopsy were analyzed. Accordingly, a total of 3913 men were included in our study.

The NLR value was calculated from the laboratory data obtained prior to the prostate biopsy. The results are shown as the median (IQR). Biopsy results, age, body mass index (BMI), DRE findings (abnormal vs normal), the presence of hypoechoic lesions on TRUS, the number of biopsy cores obtained, and the NLR results were also assessed using the Chi-square test or Mann–Whitney U-test to determine statistically significant differences. After adjusting for confounding factors, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the association between prostate cancer detection and NRL. The predictive accuracy of the multivariate model was assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC)-derived area under the curve (AUC) analysis. Two multivariate models, including either the presence or absence of NLR, were compared via the Mantel–Haenszel test. The IBM SPSS software package version 21.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences™, Chicago, IL, USA) and MedCalc software version 11 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium) were used for statistical analysis. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered as significant for all analyses.

RESULTS

The median age of the 3913 men analyzed in the present study was 65 years, the median BMI was 24.3 kg m−2, the median prostate volume was 40 ml, and the median PSA level was 6.04 ng ml−1. Of the 1845 men for whom sufficient data were available, 360 (19.5%) had abnormal DRE findings. A total of 420 (15.7%) of 2668 subjects had hypoechoic TRUS findings. Among all the subjects, prostate cancer was detected via biopsy in 1106 (28.3%). There were 116 (10.5%) men with a high Gleason prostate cancer score (≥4 + 3).

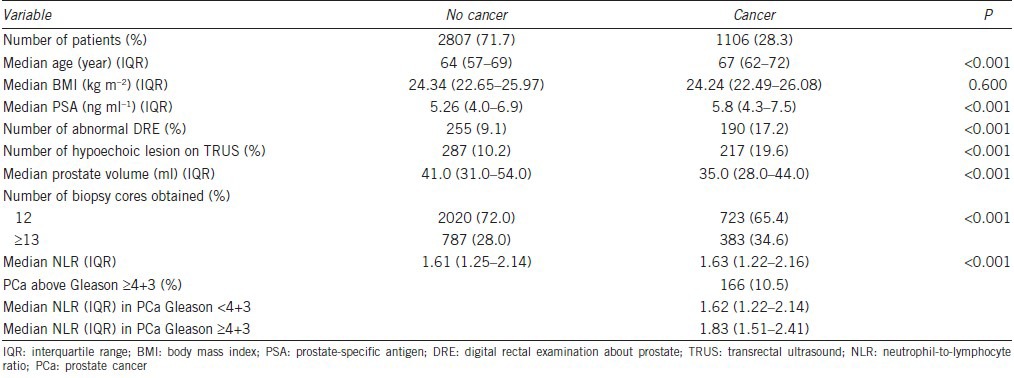

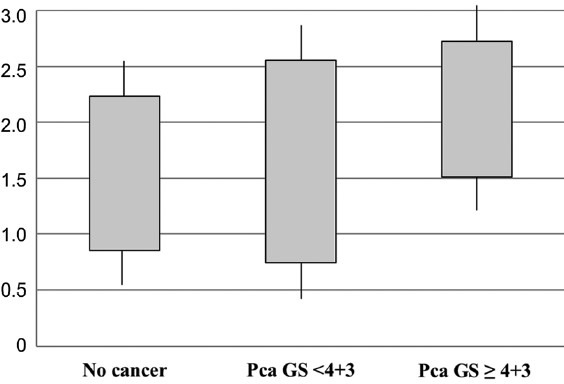

The subject characteristics according to the presence of prostate cancer are shown in Table 1. Among the patients in the total biopsy cohort, the prostate cancer patients were older (median age, 67 vs 64, P < 0.001), had higher PSA levels (median PSA, 5.80 vs 5.26, P < 0.001), higher rates of abnormal DRE findings (17.2% vs 9.1%, P < 0.001), hypoechoic lesions on TRUS (19.6% vs 10.2%, P < 0.001), and smaller prostate volumes (35.0 cc vs 41.0 cc, P < 0.001) compared to noncancer patients. The mean core number was also higher in the biopsy-positive group than in the biopsy-negative group. The NLR value was higher in the biopsy-positive group than in the biopsy-negative group (1.63 vs 1.61, P < 0.001). The NLR value in high Gleason prostate cancer (≥4 + 3) was 1.83, significantly higher than the biopsy-negative group and low-grade prostate cancer group (P < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects according to biopsy outcome

Figure 1.

Box plot of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in no cancer patients, low grade prostate cancer patients (Gleason score <4 + 3) and high grade prostate cancer patients (≥4 + 3) after transrectal ultrasound prostate biopsy.

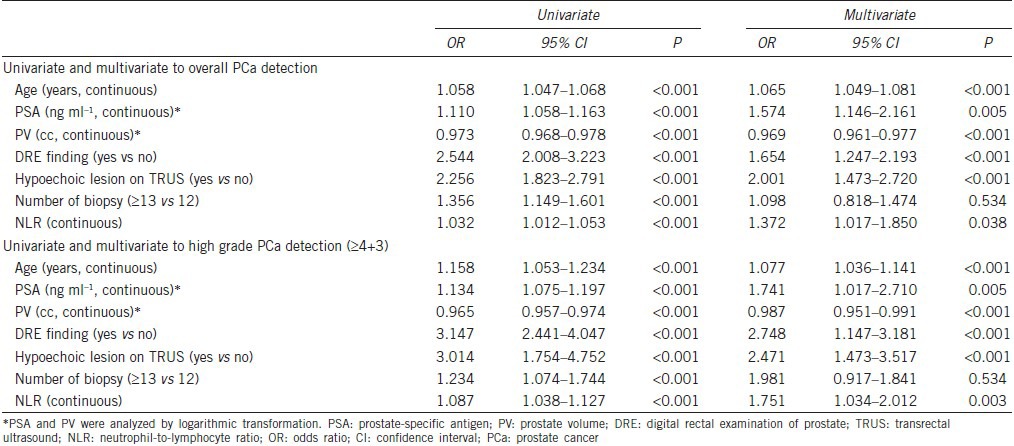

As shown in Table 2, age, PSA, prostate volume, abnormal DRE findings, hypoechoic lesions on TRUS, number of biopsy cores (≥13 vs 12), and NLR were all significant factors associated with prostate cancer detection that were determined by univariate logistic regression analysis. On multivariate analyses, a higher NLR (OR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.017–1.850, P = 0.038) was significantly associated with prostate cancer detection (after adjusting for age, serum prostate-specific antigen, prostate volume, abnormal DRE findings, presence of hypoechoic lesions on TRUS, and number of biopsy cores). In multivariate analysis to predict higher Gleason grade prostate cancer (≥4 + 3), NLR was significant predictor after adjusting aforementioned variables (OR = 1.75, 95% CI: 1.034–2.012, P = 0.003).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis on the potential association of analyzed variables and detection of PCa via prostate biopsy

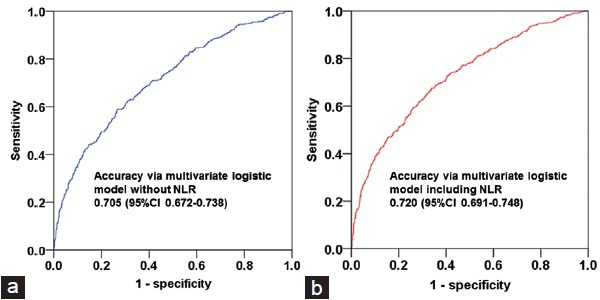

The predictive accuracy calculated (AUC) for the multivariate model (including age, PSA, and prostate volume as continuous variables + abnormal DRE findings, hypoechoic lesions on TRUS, and number of biopsy cores as categorical variables), excluding NLR, was 0.705 (95% CI, 0.672–0.738, Figure 2a). This accuracy level significantly increased to 0.720 from the multivariate model that NLR was additionally included aforementioned multivariate model (95% CI, 0.691–0.748; P = 0.005, Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristics curves of the multivariate logistic regression model, (a) excluding neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), (b) including NLR which was developed for prostate cancer detection via contemporary multi (≥12)-core transrectal ultrasound biopsy (P = 0.005).

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we observed that NLR was significantly associated with prostate cancer detection among men with PSA levels ranging from 4 to 10 ng ml−1 who underwent multi (≥12)-core TRUS-guided biopsy. After adjusting for confounding factors, multiple logistic regression analyses suggested that the NLR is positively associated with prostate cancer detection. Using the multivariate model, we identified an additional predictive factor, the NLR, for detecting prostate cancer via the ROC-derived AUC value.

Prediagnostic inflammatory factors have been positively associated with the detection of cancer and cancer mortality in solid organ cancers, including colorectal, lung, and gastric cancers.4,17,18,19 In a recently published prospective population-based study in Japan, elevated leukocyte counts were associated with a two-fold increased risk of gastric cancer.18 Similarly, in a cohort study in the United States, elevated leukocyte counts were associated with a 2.8-fold increased risk of lung cancer.19 However, there are few epidemiologic data that suggest a positive association between prostate cancer and systemic inflammation. In a study of 2571 men, Toriola et al. reported that prediagnostic inflammatory markers had a significantly positive association with prostate cancer and that an elevated leukocyte count was associated with a 2.57-fold increased risk of prostate cancer mortality.15

The functional relationship between inflammation and cancer has long been discussed. In 1863, Virchow hypothesized that cancer originated at the site of chronic inflammation and was triggered by chronic inflammation and increased cell proliferation.20 These inflammatory markers, along with some growth factors, have DNA damage-promoting properties, which may potentiate and/or promote neoplastic activity. Many cancers have been associated with inflammation, and the causal relationship between inflammation, innate immunity, and cancer has been widely accepted. However, many of the molecular and cellular mechanisms mediating this relationship remain unresolved. Coussens and Werb21 reported an association between inflammation and enhanced tumor growth mediated via a chemokine effect. In such a model, tumor-associated leukocyte and systemic inflammatory markers would be partially responsible for tumor initiation and growth. Some reports have shown a positive link between inflammation and prostate carcinogenesis.13,14 Experimental evidence has demonstrated that mice infected with bacteria developed prostatitis as early as 5 days, which subsequently progressed to chronic inflammation and dysplastic changes akin to prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia.22 Despite the aforementioned studies, the relationship between prostate inflammation and prostate cancer in men remains unclear.

Many studies have demonstrated that the histologic detection of inflammation is an indicator of a negative biopsy.1,23,24 Because serum PSA has been positively associated with prostate inflammation, it is possible for PSA to be elevated with no underlying prostate cancer. As such, a highly elevated PSA level is not strongly correlated with prostate cancer. Fujita et al.1 demonstrated that a low serum neutrophil count was a predictor of positive prostate biopsy in 323 Japanese men (OR = 0.408, P < 0.002). In reality, the PSA level was elevated secondary to prostate inflammation. Therefore, it was possible that the PSA was falsely elevated in men who had clinical prostatitis, not prostate cancer. These studies concluded that inflammation caused PSA elevation; therefore, decreased incidence of prostate cancer. However, most of these studies lack evidence that chronic prostatitis is associated with systemic inflammation. There are no definitive data regarding an association between elevation of a systemic inflammatory marker, chronic prostatitis, and cancer development. Therefore, it is important to avoid hasty conclusions.14,25

Two European cohort studies have shown results that are similar to ours. In a Swedish cohort, 44% increased prostate cancer risk was reported when leukocyte counts were elevated in relatively young men, and 60% increased prostate cancer risk was reported in a cohort in Finland.15,26 Similar to our results, in studies with large numbers of participants, a higher NLR led to 37.2% increase in the risk of prostate cancer compared with a low NLR. In advanced PCa studies, NLRs are important factors in survival outcome predictions.12,27 The NLR may be related to immune function. It has been described that low lymphocyte counts were associated with a generalized state of immunosuppression in several different types of cancer, and this immunosuppression seemed to be associated with the outcome of these patients.28

Further evidence of the role of inflammation in prostate carcinogenesis can be derived from studies showing that prostate carcinoma cells strongly express the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) enzyme in one report.29 COX-2 is necessary for prostaglandin synthesis and is an important mediator of the inflammatory cascade.21,30 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) inhibit COX-2 synthesis which leads to decreased activation of the inflammatory cascade and decreased epithelial proliferation.29 Studies have reported an inverse relationship between NSAID use and the risk of prostate cancer although the only NSAID examined was aspirin.31,32

This study had several limitations. First, it was a retrospective cohort study that involved manual extraction of clinical data. The second limitation was that neutrophil and lymphocyte counts varied from individual to individual due to various physiological, pathological, and physical factors. Although the NLR has been reported to be fairly stable11 and we excluded the patients who had medically active illness, history of systemic inflammatory disease and medicine history of anti-inflammatory drug history, NLR could be varied from person to person and various medical condition which was unknown factors. However, NLR is a useful marker for detecting prostate cancer, and it may be an effective and simple marker that can be assessed in blood samples. Another limitation was that we could not exclude patients who had pathological proven prostatitis after biopsy. To eliminate any bias derived from an association between PSA and prostatitis, ideally, future studies should enroll men who have normal prostate tissue or prostate cancer; however, this is impossible in a real clinical setting. The strengths of our study were the large sample size and the adjustment for confounding factors. We selected the NLR from prebiopsy data and excluded patients with evidence of acute and subacute prostatitis. Therefore, we recommend that if patients had high NLR and PSA was 4–10 ng ml−1 without systemic or prostate-related inflammation, they should be underwent TRUS-guided biopsy. Our results provided strong evidence linking inflammation with prostate carcinogenesis.

CONCLUSIONS

The NLR marker that is representative of systemic inflammation demonstrated its positive association with prostate cancer detection in men who underwent multi (≥12)-core TRUS-guided biopsy in the PSA gray zone. The NLR might be a promising, readily available, inexpensive biomarker with significantly accurate predictive power after adjusting for other confounding variables.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JJ Oh and O Kwon contributed the study concept and design. JJ Oh wrote the draft of the manuscript under the supervision of SK Hong, SS Byun, S Lee and SE Lee. JK Lee conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declared no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fujita K, Imamura R, Tanigawa G, Nakagawa M, Hayashi T, et al. Low serum neutrophil count predicts a positive prostate biopsy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012;15:386–90. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2012.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson IM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. Assessing prostate cancer risk: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:529–34. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ploussard G, Nicolaiew N, Marchand C, Terry S, Allory Y, et al. Risk of repeat biopsy and prostate cancer detection after an initial extended negative biopsy: longitudinal follow-up from a prospective trial. BJU Int. 2013;111:988–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Seruga B, Vera-Badillo FE, Aneja P, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju124. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guthrie GJ, Charles KA, Roxburgh CS, Horgan PG, McMillan DC, et al. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: experience in patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88:218–30. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buergy D, Wenz F, Groden C, Brockmann MA. Tumor-platelet interaction in solid tumors. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:2747–60. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keizman D, Ish-Shalom M, Huang P, Eisenberger MA, Pili R, et al. The association of pre-treatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio with response rate, progression free survival and overall survival of patients treated with sunitinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh SR, Cook EJ, Goulder F, Justin TA, Keeling NJ. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91:181–4. doi: 10.1002/jso.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chua W, Charles KA, Baracos VE, Clarke SJ. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio predicts chemotherapy outcomes in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:1288–95. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roxburgh CS, McMillan DC. Role of systemic inflammatory response in predicting survival in patients with primary operable cancer. Future Oncol. 2010;6:149–63. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:448–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nuhn P, Vaghasia AM, Goyal J, Zhou XC, Carducci MA, et al. Association of pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and overall survival (OS) in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) treated with first-line docetaxel. BJU Int. 2014;114:E11–7. doi: 10.1111/bju.12531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Marzo AM, Platz EA, Sutcliffe S, Xu J, Gronberg H, et al. Inflammation in prostate carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:256–69. doi: 10.1038/nrc2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutcliffe S, Platz EA. Inflammation in the etiology of prostate cancer: an epidemiologic perspective. Urol Oncol. 2007;25:242–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toriola AT, Laukkanen JA, Kurl S, Nyyssonen K, Ronkainen K, et al. Prediagnostic circulating markers of inflammation and risk of prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:2961–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC, Jr, Amin MB, Egevad LL. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus conference on Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1228–42. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000173646.99337.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Margolis KL, Rodabough RJ, Thomson CA, Lopez AM, McTiernan A. Prospective study of leukocyte count as a predictor of incident breast, colorectal, endometrial, and lung cancer and mortality in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1837–44. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iida M, Ikeda F, Ninomiya T, Yonemoto K, Doi Y, et al. White blood cell count and risk of gastric cancer incidence in a general Japanese population: the Hisayama study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:504–10. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sprague BL, Trentham-Dietz A, Klein BE, Klein R, Cruickshanks KJ, et al. Physical activity, white blood cell count, and lung cancer risk in a prospective cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2714–22. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–7. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elkahwaji JE, Hauke RJ, Brawner CM. Chronic bacterial inflammation induces prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in mouse prostate. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1740–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonald AC, Vira MA, Vidal AC, Gan W, Freedland SJ, et al. Association between systemic inflammatory markers and serum prostate-specific antigen in men without prostatic disease – The 2001-2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Prostate. 2014;74:561–7. doi: 10.1002/pros.22782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sadeghi N, Badalato GM, Hruby G, Grann V, McKiernan JM. Does absolute neutrophil count predict high tumor grade in African-American men with prostate cancer? Prostate. 2012;72:386–91. doi: 10.1002/pros.21440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sfanos KS, De Marzo AM. Prostate cancer and inflammation: the evidence. Histopathology. 2012;60:199–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Hemelrijck M, Jungner I, Walldius G, Garmo H, Binda E, et al. Risk of prostate cancer is not associated with levels of C-reactive protein and other commonly used markers of inflammation. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:1485–92. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Templeton AJ, Pezaro C, Omlin A, McNamara MG, Leibowitz-Amit R, et al. Simple prognostic score for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with incorporation of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio. Cancer. 2014;120:3346–52. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pond GR, Berry WR, Galsky MD, Wood BA, Leopold L, et al. Neutropenia as a potential pharmacodynamic marker for docetaxel-based chemotherapy in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2012;10:239–45. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta S, Srivastava M, Ahmad N, Sakamoto K, Bostwick DG, et al. Lipoxygenase-5 is overexpressed in prostate adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2001;91:737–43. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010215)91:4<737::aid-cncr1059>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ulrich CM, Bigler J, Potter JD. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for cancer prevention: promise, perils and pharmacogenetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:130–40. doi: 10.1038/nrc1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson JE, Harris RE. Inverse association of prostate cancer and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): results of a case-control study. Oncol Rep. 2000;7:169–70. doi: 10.3892/or.7.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahmud SM, Franco EL, Aprikian AG. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and prostate cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:1680–91. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]