MPLA-mediated augmentation of innate immune responses is mediated by distinct contributions of the MyD88- and TRIF-dependent TLR signaling pathways.

Keywords: TLR4, innate immunity, cytokines, neutrophil, monocyte, myeloid progenitors

Abstract

Treatment with the TLR4 agonist MPLA augments innate resistance to common bacterial pathogens. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which MPLA augments innate immunocyte functions are not well characterized. This study examined the importance of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling for leukocyte mobilization, recruitment, and activation following administration of MPLA. MPLA potently induced MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling. A single injection of MPLA caused rapid mobilization and recruitment of neutrophils, a response that was largely mediated by the chemokines CXCL1 and -2 and the hemopoietic factor G-CSF. Rapid neutrophil recruitment and chemokine production were regulated by both pathways although the MyD88-dependent pathway showed some predominance. In further studies, multiple injections of MPLA potently induced mobilization and recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes. Neutrophil recruitment after multiple injections of MPLA was reliant on MyD88-dependent signaling, but effective monocyte recruitment required activation of both pathways. MPLA treatment induced expansion of myeloid progenitors in bone marrow and upregulation of CD11b and shedding of L-selectin by neutrophils, all of which were attenuated in MyD88- and TRIF-deficient mice. These results show that MPLA-induced neutrophil and monocyte recruitment, expansion of bone marrow progenitors and augmentation of neutrophil adhesion molecule expression are regulated by both the MyD88- and TRIF-dependent pathways.

Introduction

Monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA) is a TLR4 agonist that was originally derived by acid hydrolysis of native lipid A from Salmonella minnesota resulting in removal of the 1-phosphate group and varying degrees of deacylation [1, 2]. More recently, MPLA has been synthesized de novo [3]. The described structural changes, particularly removal of the 1-phosphate group, results in a form of lipid A that retains potent immunomodulatory activity but with ∼0.1% of the immunotoxicity of native diphosphoryl lipid A [1, 2, 4]. Because of these properties, MPLA is currently used as a component of the ASO4 vaccine adjuvant system, which is used clinically in the human papilloma virus (Ceravix; GlaxoSmithKline, London, UK) vaccine [5, 6]. As such, MPLA has been safely administered to thousands of patients, and there has been a low incidence of clinically significant adverse events [7]. In addition to low toxicity, MPLA serves as an attractive immunoadjuvant because of its ability to facilitate the activation of APCs and promote polarization, activation, and clonal expansion of Th1 cells [8]. Injection of MPLA stimulates the recruitment of monocytes and, to a lesser extent, dendritic cells to the site of injection and into draining lymph nodes [9]. MPLA-recruited APCs exhibit an activated phenotype characterized by increased MHCII and costimulatory molecule (CD80/CD86) expression, as well as enhanced cytokine and chemokine secretion [10]. MPLA-activated T cells exhibit robust IFN-γ secretion, characteristic of Th1 polarization and macrophage and B cell activation [8]. Consequently, the addition of MPLA to vaccine preparations boosts antibody titers by 10–20-fold [11].

In addition to its value as a vaccine adjuvant, MPLA retains the ability to nonspecifically enhance host resistance to viral, parasitic, and bacterial infections [12–14]. Recent studies from our laboratory showed that treatment with MPLA causes augmentation of innate host resistance to sepsis caused by cecal ligation and puncture and Pseudomonas burn wound infection [15–17]. Thus, the ability of MPLA to enhance innate antimicrobial immunity could have clinical value in patients that are vulnerable to bacterial and fungal infections, such as those who are critically ill, have suffered major burn injuries, or have undergone high risk surgical procedures. The augmented antimicrobial immunity is characterized by increased recruitment of neutrophils to sites of infection and improved bacterial clearance [15, 17]. However, the molecular mechanisms by which MPLA augments innate immune functions are not well understood.

All TLRs share an intracellular domain that can signal through MyD88 and TRIF pathways. TLR4 is unique, in that it is the only TLR that activates both the MyD88- and TRIF-dependent pathways [13, 18]. Studies have examined the contributions of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling to the immunoadjuvant properties of MPLA. Mato-Haro and colleagues [19] reported that the ability of MPLA to augment antigen-dependent T cell activation and expansion is mediated through TRIF-biased signaling. A more recent paper by Kolanowski and colleagues [20] reported that proinflammatory cytokine production by dendritic cells in response to MPLA is dependent on both MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling but upregulation of dendritic cell costimulatory molecule expression is TRIF dependent. To our knowledge, there are no published studies on the contributions of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling to MPLA-induced augmentation of innate antimicrobial immune responses and innate immunocyte functions. In the present study, we examined the signaling pathways by which MPLA facilitates innate immunocyte expansion, mobilization, and recruitment with specific emphasis on the contributions of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling.

METHODS

Mice

All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Vanderbilt University and complied with the U.S. National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals. Male 8- to 12-wk-old C57BL/6J, C57BL/10J, C57BL/10ScNJ, MyD88−/− (B6.129P2(SJL)-Myd88tm1.1Defr/J), and TRIF−/− (C57BL/6J-Ticam1Lps2/J) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). MyD88−/− (MyD88-KO) and TRIF−/− (TRIF-KO) mice were backcrossed onto the C57BL/6J background for at least 10 generations. C57BL/ScNJ (TLR4-KO) mice were derived after a spontaneous mutation of TLR4 in C57BL/10J mice.

MPLA

Monophosphoryl lipid A (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in endotoxin-free water containing 0.2% trimethylamine and sonicated in a 40°C water bath for 1 h. Dilutions of MPLA for injection were prepared using lactated Ringer’s solution.

Assessment of MPLA-induced neutrophil recruitment and cytokine/chemokine production

Mice received an injection of MPLA (20 µg in 0.2 ml LR solution, i.p.). The 20 μg dose of MPLA was chosen because it has been shown to be effective in augmenting innate antimicrobial immunity in our published studies [15, 17]. Vehicle-treated mice received the same volume of LR solution. Blood and peritoneal lavage fluid were harvested at 0, 3, and 6 h after MPLA injection. All cell counts were performed using a TC20 automated cell counter (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). After general anesthesia was achieved with 2.5% isoflurane, blood was collected via carotid artery laceration, transferred to heparinized tubes for plasma isolation and K3D tubes (Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmunster, Austria) for CBCs, and differential and immediately placed on ice. CBC measurements were performed with a Forcyte veterinary hematology analyzer (Oxford Science, Oxford, CT, USA). Plasma was collected after centrifugation of blood (4750 rpm for 10 min at 4°C). Peritoneal lavage fluid was obtained by lavage of the peritoneal cavity with 2 ml cold PBS. Cells were counted, centrifuged (300 g for 10 min), and suspended in PBS. Neutrophils (F4-80−Ly6G+) in peritoneal lavage fluid were identified by flow cytometry. Peritoneal lavage supernatant was retained for cytokine measurements.

Flow cytometry

Leukocytes were suspended in PBS (1 × 107 cells/ml) and incubated with anti-mouse CD16/32 (1 μl/ml; eBioscience, San Diego, C, USA) for 5 min to block nonspecific Fc receptor–mediated antibody binding. One million cells were then transferred into polystyrene tubes. Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies or isotype controls (0.5 μg/tube) were added, incubated at room temperature for 20 min, washed with 2 ml of cold PBS, centrifuged at 300 g for 10 min, and suspended in 250 μl cold PBS. Samples were run immediately on an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were analyzed with Accuri C6 software.

Antibodies used included anti-Ly6G-PE, anti-F4-80-FITC, anti-Ly6C-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-CD3-FITC, anti-CD19-PE, and Class II-PE-Cy5 and appropriate isotype controls (eBioscience). Neutrophils were identified as F4-80−/Ly6G+, monocytes as F4-80+/Ly6C+, T cells as CD3+, and B cells as CD19+/Class II MHC+.

Cytokine/chemokine measurements

Concentrations of G-CSF, CXCL-1, and CXCL-2 in plasma and peritoneal lavage fluid were measured with a custom-built Bio-Plex mouse bead array kit according to the manufacturer’s directions (Bio-Rad). Samples were analyzed with a Bio-Plex MagPix MultiPlex Reader (Bio-Rad).

Effect of chemokine/G-CSF neutralization on neutrophil mobilization and recruitment

C57BL/6J male mice received intravenous treatment with anti-mouse CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCR2, G-CSF, or IgG at 24 h before IP MPLA treatment (20 μg/0.2 ml). All mice received 100 μg of the respective antibody according to their group assignment, with the exception of the anti-CXCL1/CXCL2, which received 200 µg (100 µg CXCL1 + 100 µg CXCL2). Blood and peritoneal lavage fluid were collected at 3 h after administration of MPLA and examined for neutrophil counts.

Generation of BMDMs

Femurs were obtained from male C57/B6J mice and stripped of muscle. Bone marrow was flushed from the marrow cavity with PBS. Cells were washed and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (Corning, Inc., Corning, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (penicillin-streptomycin, Fungizone; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 10 ng/ml recombinant M-CSF (M-RPMI; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Cells were cultured in flasks with an ultralow attachment surface (Corning, Inc.) at 37°C and 5% CO2. On day 7 after harvest, cells were washed and resuspended in M-RPMI. BMDMs were confirmed to be >95% CD11b+ on day 8 and were incubated with vehicle or MPLA (1 μg/ml) for 30 min.

Western blot analysis

Cultured cells or peritoneal fluid cells were washed twice with HBSS and lysed with RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) containing PhosStop and complete Protease Inhibitor tablets (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Protein samples were mixed 1:1 with Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad) and separated by gel electrophoresis on Mini Protean precast 4–20% Tris-glycine gels (Bio-Rad). Proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% fraction V BSA (RPI Corp., Mount Prospect, IL, USA) for 1 h and incubated with primary antibodies in 5% BSA at 4°C overnight. Membranes were washed 3 times for 5 min in TBST. Protein bands were detected with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies in 5% BSA, washed 3 times for 5 min in TBST, and incubated for 60 s with ECL reagent. Images were cropped using ImageJ software from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA).

MPLA priming experiments

C57BL/6J, MyD88-KO, and TRIF-KO mice underwent IP or IV MPLA priming. MPLA priming is defined as administration of MPLA (20 µg in 0.2 ml LR) at 48 and 24 h before harvesting samples. This protocol replicates the one used to show MPLA-induced enhanced antimicrobial immunity in our previous studies. At 24 h after the second MPLA injection, peritoneal lavage fluid was harvested, and cells were counted using a TC20 automated cell counter (Bio-Rad). Peritoneal lavage fluid was obtained by lavage of the peritoneal cavity with 2 ml of cold PBS. The lavage fluid was centrifuged (300 g for 10 min) and the cellular fraction was suspended in PBS (1 × 107 cells/ml). Spleens were harvested, placed in 35-mm dishes containing RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS and homogenized by smashing with the plunger from a 10 ml syringe. The homogenate was passed through a 70 mm cell strainer, and erythrocytes were lysed with RBC Lysis Buffer (Sigma-Aldrich). The remaining cells were counted using TC20 Automated Cell Counter (Bio-Rad) and centrifuged (300 g for 10 min), and the cell pellet was resuspended in PBS for flow cytometry analysis.

Progenitor cell colony growth measurement

Proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells was measured with colony-forming cell assays (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) per the manufacturer’s specifications. After IV MPLA priming, femurs were isolated and flushed with 5 ml cold PBS + 2% FBS. Ammonium chloride solution was added for red blood cells lysis. Cells were counted and suspended at 1 × 105 cells per ml in MethoCult Medium. Cells were then plated onto pretested culture dishes and incubated for 9 d in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Colony morphologies were assessed and counted using an inverted microscope.

Ex vivo adhesion marker expression

The adhesion markers CD11b and CD62L (L-selectin) were measured on bone marrow neutrophils by flow cytometry after ex vivo stimulation with various concentrations of MPLA. Bone marrow cells were collected by flushing the medullary cavity of femurs with cold PBS. Cells were transferred onto 24-well plates at a concentration of 1 × 107/ml in FBS-supplemented RPMI-1640. The concentrations of MPLA included 1, 10, 100, and 1000 ng/ml. Cells were incubated in 5% CO2 for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were washed and stained for adhesion markers using fluorochrome-conjugated anti-CD11b or anti-CD62L (eBioscience). Analysis for expression of adhesion markers was done by the Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Statistics

All data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data from multiple group experiments were analyzed with 1-way ANOVA, followed by a post hoc Tukey multicomparison test. All values are presented as the mean ± SEM. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

MPLA activates both the MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling pathways

Studies were undertaken to assess the ability of MPLA to induce activation of the MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling pathways in bone marrow-derived macrophages (Fig. 1). Cultured BMDMs were incubated with MPLA or vehicle for 30 min. IRF3 and IKK phosphorylation were assessed as indices of TRIF-and MyD88-dependent signaling, respectively. MPLA induced phosphorylation of IRF3 and IKK to similar levels in BMDMs. IRF3 phosphorylation was markedly reduced in TRIF−/−, but not MyD88−/−, BMDMs. IKK phosphorylation was significantly decreased in both TRIF−/− and MyD88−/− BMDMs but to a greater degree in TRIF−/− BMDMs.

Figure 1. MPLA induces activation of the MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling pathways.

BMDMs were incubated with vehicle or MPLA for 30 min. IRF3 and IKK phosphorylation, as well as total IKK and IRF3 were determined by Western blot analysis. Assessment of phospho- and total IRF3 (top) and phospho- and total IKK (bottom) in WT, MyD88-KO, and TRIF-KO BMDMs. Graphs show results quantified by densitometry. The results are representative of 3 different runs. *P < 0.05 vs. WT, +P < 0.05, vs. MyD88-KO.

CXCR2 ligands and G-CSF are essential for MPLA-induced neutrophil mobilization and recruitment

Our previous studies show that enhanced neutrophil recruitment plays an important role in MPLA-induced augmentation of the host response to infection. Studies were undertaken to define the kinetics of MPLA-induced neutrophil recruitment and the chemokines responsible for rapid neutrophil mobilization to the site of MPLA injection. Mice received a single intraperitoneal injection of MPLA and neutrophil numbers in blood and peritoneal cavity were measured at 3 and 6 h after injection (Fig. 2). MPLA induced an increase in the percentage of neutrophils in blood and peritoneal cavity at 3 and 6 h after injection (Fig. 2A). Total blood neutrophil counts were increased at 3 h after MPLA but returned to baseline at 6 h. Total neutrophil counts in the peritoneal cavity were markedly increased at 3 and 6 h after treatment with MPLA.

Figure 2. MPLA-induced neutrophil mobilization and recruitment are mediated by CXCL1, CXCL2, and G-CSF.

Wild-type mice received an injection of 20 μg MPLA i.p. Whole blood, plasma, and peritoneal lavage fluid were harvested at 0, 3, and 6 h after MPLA challenge. (A) Neutrophil counts in blood and peritoneal lavage fluid. Blood neutrophils were counted with a clinical analyzer, and intraperitoneal neutrophils were measured by flow cytometry and identified as F4-80-Ly6G+; (B) CXCL1, CXCL2, and G-CSF were measured in the plasma and peritoneal lavage fluid using a magnetic bead reader. (C) Chemokine neutralization was achieved by administration of IgG or anti-mouse CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCR2+CXCR1, or G-CSF 24 h before intraperitoneal MPLA injection. The number of neutrophils in blood and peritoneal lavage fluid was measured at 3 h after MPLA challenge (n = 9–21/group). *P < 0.05 vs. 0 h control, +P < 0.05 vs. IgG control.

The chemokines CXCL1 and -2, as well as the hematopoietic factor G-CSF, play important roles in neutrophil recruitment and mobilization. Their concentrations were measured in plasma and peritoneal lavage fluid at 3 and 6 h after intraperitoneal treatment with MPLA (Fig. 2B). CXCL1, CXCL2, and G-CSF were elevated in both plasma and the peritoneal cavity at 3 h after MPLA injection. CXCL2 and G-CSF concentrations remained elevated in plasma at 6 h after MPLA injection, whereas concentrations of CXCL1 did not. Only CXCL2 remained elevated in the peritoneal cavity at 6 h after MPLA injection.

The contributions of CXCL1, CXCL2 and G-CSF to neutrophil mobilization and recruitment were assessed by blockade of each factor with factor-specific antibodies before MPLA challenge. Mice treated with nonspecific IgG served as controls. Neutrophils in blood and the peritoneal cavity were measured 3 h after intraperitoneal MPLA injection (Fig. 2C). MPLA induced an increased number of neutrophils in blood and the neutrophil percentage in the peritoneal cavity in mice treated with nonspecific IgG. Anti-CXCL1 caused a decreased percentage of neutrophils in the peritoneal cavity but did not significantly alter the number of neutrophils in blood compared to IgG-treated controls. CXCL2 blockade did not alter the number of MPLA-induced neutrophils in the blood or the percentage of neutrophils in the peritoneal cavity compared with nonspecific IgG. Coadministration of anti-CXCL1 and anti-CXCL2, anti-CXCR2 alone, or anti-G-CSF alone caused significant decreases in MPLA-induced neutrophils in blood and the peritoneal cavity compared to nonspecific IgG.

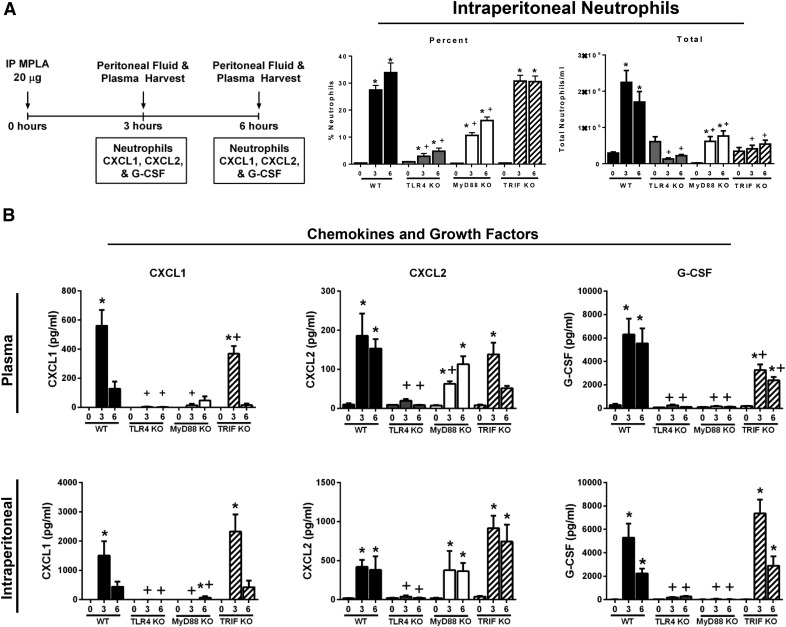

MPLA-induced neutrophil recruitment, CXCL1, and G-CSF production are attenuated in MyD88-KO and TRIF-KO mice

Studies were undertaken to determine the functional importance of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling in facilitating MPLA-induced neutrophil recruitment and induction of factors important in regulating neutrophil recruitment (Fig. 3). Neutrophil recruitment into the peritoneal cavity was assessed at 3 and 6 h after intraperitoneal injection of MPLA in WT, TLR4-KO, MyD88-KO, and TRIF-KO mice (Fig. 3A). WT and TRIF-KO mice showed a significant increase in the percentage of peritoneal neutrophils at 3 and 6 h after MPLA injection, which was nearly ablated in TLR4-KO mice and significantly decreased in MyD88-KO mice, as compared to WT controls at 3 and 6 h after MPLA injection. The total numbers of neutrophils in the peritoneal cavity after MPLA treatment were significantly decreased in TLR4-KO, MyD88-KO, and TRIF-KO mice compared with WT controls at 3 and 6 h after MPLA injection.

Figure 3. Neutrophil recruitment and cytokine production are attenuated in MyD88-deficient mice.

(A) Mice received an injection of 20 μg MPLA i.p. at 3 or 6 h before sample harvest. Intraperitoneal leukocytes were harvested at 0, 3, or 6 h after MPLA challenge and the number of neutrophils was measured by flow cytometry. Neutrophils were identified as F4/80−Ly6G+. (B) Plasma and peritoneal lavage fluid were harvested at 0, 3, and 6 h after MPLA challenge, and the cytokine levels were measured (n = 8–19/group). *P < 0.05 vs. time 0, +P < 0.05 vs. WT.

Production of CXCL1, CXCL2, and G-CSF were also assessed in WT, TLR4-KO, MyD88-KO, and TRIF-KO mice after MPLA injection (Fig. 3B). MPLA increased concentrations of CXCL1, CXCL2, and G-CSF in plasma and the peritoneal cavity of WT and TRIF-KO mice. TLR4-KO mice displayed markedly lower concentrations of all 3 factors in plasma and peritoneal cavity compared with WT mice. MyD88-KO mice exhibited significantly lower concentrations of plasma and intraperitoneal CXCL1 and G-CSF at 3 and 6 h after MPLA challenge compared with WT controls.

Myeloid cell mobilization and recruitment are attenuated in MyD88- and TRIF-deficient mice receiving multiple intraperitoneal MPLA injections

To characterize the importance of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling after priming with multiple MPLA injections, we conducted studies to assess myeloid cell recruitment at 24 h after 2 intraperitoneal MPLA injections in WT, MyD88- and TRIF-deficient mice (Fig. 4). This treatment protocol is identical to the one that we have used to demonstrate the efficacy of MPLA in models of infection (Fig. 4A). As compared to vehicle, a significant increase in both percentage and total number of neutrophils and monocytes was observed in the peritoneal cavity of WT mice after MPLA injection (Fig. 4B). TRIF-KO mice demonstrated a similar number of neutrophils compared to WT mice; however, monocyte counts were significantly lower in TRIF-KO mice than in the WT controls. MPLA treatment did not increase the total number of neutrophils or monocytes in the peritoneal cavity of MyD88-KO mice.

Figure 4. Myeloid cell recruitment is impaired in MyD88-KO mice after multiple intraperitoneal MPLA injections.

(A) Mice received injection of 20 μg MPLA i.p. 48 and 24 h before samples were harvested. (B) Intraperitoneal leukocytes were collected, and cells were stained for F4/80, Ly6G, and Ly6C. Neutrophils were identified as F4/80−Ly6G+. Monocytes were identified as F4/80+Ly6C+ (n = 8–14/group). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle, +P < 0.05 vs. WT.

MPLA treatment increases spleen weight and number of myeloid and lymphoid cells in the spleen

Studies were undertaken to assess the effect of MPLA treatment on leukocyte populations in the spleen and determine the contributions of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling. Measurements were made 24 h after 2 daily injections of MPLA via either the intraperitoneal or intravenous route (Fig. 5). Intraperitoneal MPLA treatment induced a small but significant increase in spleen weight in WT and MyD88-KO mice but not in TRIF-KO mice. Intraperitoneal MPLA did not yield an increase in splenocyte counts in any of the 3 groups (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. Intravenous MPLA injection increases spleen weight and cellularity.

(A) Mice received an injection of 20 μg MPLA i.p. 48 and 24 h before spleen harvest. The spleen was excised, weighed, and homogenized for total cell count analysis. (B) Mice received injections of 20 μg MPLA i.v. 48 and 24 h before spleen harvest. The spleen was excised, weighed, and homogenized for cell count analysis. Splenocytes were stained for F4/80, Ly6G, Ly6C, CD19, and Class II MHC. Neutrophils were identified as F4/80−Ly6G+, monocytes as F4/80+/Ly6C+, T cells as CD3+, and B cells as CD19+/MHC Class II+ (n = 10–20/group.). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle; +P < 0.05 vs. WT.

In contrast to intraperitoneal MPLA treatment, intravenous MPLA markedly increased both spleen weight and cellularity in the WT, and to a lesser degree, the MyD88-KO groups (Fig. 5B). No change in spleen weight or cellularity was observed in the TRIF group after MPLA injections. Predominant spleen myeloid and lymphoid cell populations were assessed and showed that intravenous MPLA primarily increased the numbers of neutrophils, monocytes, and B cells. Both neutrophil and monocyte total cell counts were markedly increased after intravenous MPLA injections in WT, and to a lesser degree, MyD88-KO mice. There was no change among any of the splenocyte populations in the TRIF-KO group. Intravenous MPLA treatment induced a large expansion of total B cell counts in the spleen in WT mice and, to a lesser degree, in the MyD88 group. No change in total B cell count was noted in the TRIF-KO group. There was no significant change in the number of splenic T cells in any of the groups.

MPLA-induced expansion of myeloid progenitor cells in bone marrow is regulated by both the MyD88- and TRIF-dependent pathways

Given the ability of MPLA to augment neutrophil mobilization into blood and recruitment at sites of injection, further experiments were undertaken to assess the ability of MPLA to induce proliferation and expansion of myeloid progenitors in bone marrow (Fig. 6). At 24 h after intravenous MPLA priming, the number of bone marrow progenitors was measured in WT, TRL4-KO, MyD88-KO, and TRIF-KO mice. MPLA markedly increased leukocyte myeloid progenitors in WT mice, primarily CFU-G, CFU-GM, and CFU-M. Expansion of all progenitors was significantly attenuated in MyD88-KO, TRIF-KO, and TLR4-KO mice.

Figure 6. MPLA-induced increase in the number of bone marrow progenitor cells is attenuated in MyD88- and TRIF-deficient mice.

Mice received an injection of 20 μg MPLA i.v. at 48 and 24 h before bone marrow cell harvest. Bone marrow cells were collected and cultured in 2 culture plates/sample. Progenitor CFUs were differentiated and quantified after 10 d. BFU-E=burst-forming unit erythroid; CFU-GEMM=CFU-granulocyte/erythroid/macrophage/megakaryocyte; and CFU-PreB=CFU pre-B cells (n = 5/group). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle; +P < 0.05 vs. WT.

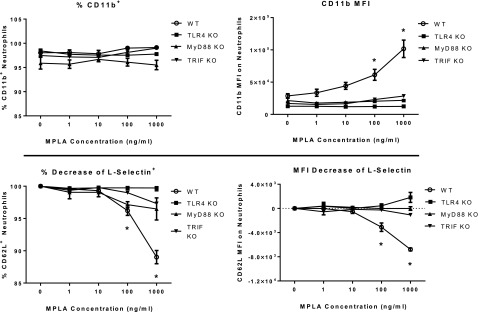

MyD88 and TRIF are necessary for MPLA-induced CD11b expression and L-selectin shedding on bone marrow neutrophils

Integrins and selectins play a key role in facilitating neutrophil adhesion during recruitment and chemotaxis. Studies were undertaken to assess the effect of MPLA on expression of CD11b and L-selectin and determine the contributions of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling on adhesion molecule expression (Fig. 7). Bone marrow cells were harvested from WT, TLR4-KO, MyD88-KO, and TRIF-KO mice and incubated with escalating doses of MPLA for 2 h. Expression of CD11b and L-selectin by neutrophils was determined by flow cytometry. Bone marrow neutrophils from the WT group demonstrated an increase in the CD11b MFI, but not the percentage, when incubated with 100 and 1000 ng/ml of MPLA. Likewise, there was a significant decline in the percentage of neutrophils expressing L-selectin and the L-selectin MFI at 100 and 1000 ng/ml of MPLA. MPLA did not change CD11b and L-selectin MFI or percentage in bone marrow from TLR4-KO, MyD88-KO, or TRIF-KO mice.

Figure 7. MPLA-induced neutrophil CD11b expression and L-selectin shedding are attenuated in MyD88- and TRIF-deficient mice.

Bone marrow cells were harvested from untreated mice from each group and incubated with increasing concentrations of MPLA for 2 h. Cells were washed; stained for F4/80, Ly6G, and either CD11b or L-selectin (CD62L); and analyzed with flow cytometry. Neutrophils were identified as F4/80−Ly6G+ (n = 5/group). *P < 0.05 vs. 0 ng.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of this study are that MPLA-induced neutrophil expansion, mobilization, and recruitment are mediated through differential contributions of the MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling pathways. These findings advance current knowledge by demonstrating the impact of the major TLR4-associated signaling pathways on MPLA-induced augmentation of innate immunocyte functions. MPLA potently facilitated neutrophil mobilization and recruitment, a function that was largely regulated by the CXCR2 ligands CXCL1 and -2, as well as the hematopoietic factor G-CSF and were reliant on both MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling, although some predominance of the MyD88-dependent pathway was evident. MPLA also induced expansion of leukocytes and their progenitors in spleen and bone marrow, as well as modulated the expression of neutrophil adhesion molecules. Those alterations were attenuated in both MyD88- and TRIF-deficient mice, suggesting contributions from both pathways.

Mata-Haro and colleagues [19] reported that the immunoadjuvant effects of MPLA are mediated through TRIF-biased signaling. They based their conclusions on the observations that MPLA is a weak inducer of MyD88-dependent cytokines compared to LPS, but its ability to induce production of TRIF-biased cytokines and T cell clonal expansion was equipotent with LPS. In further studies, they reported that MyD88-dependent signaling is delayed in response to MPLA, as compared to LPS, and that MPLA-mediated T cell activation and clonal expansion were attenuated in TRIF-, but not in MyD88-deficient mice. In a separate study, Gandhapudi et al. [18] reported that TRIF-dependent signaling is important for the maturation of APCs and T cell clonal expansion and survival in response to TLR4 agonists. They concluded that type I IFNs are the key TRIF-associated gene product driving the immunoadjuvant effects of TLR4 agonists. In a more recent study, Kolanowski and colleagues [20] reported that blockade of MyD88 or TRIF expression markedly decreased MPLA-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression by human dendritic cells. They further reported that costimulatory molecule expression is TRIF dependent and concluded that dendritic cell maturation requires the combined actions of TRIF- and MyD88-dependent signaling. Thus, in toto, current results point to TRIF-biased signaling as the key driving factor facilitating the immunoadjuvant effects of TLR4 agonists. Those findings inspired our interest in determining whether TRIF-dependent signaling mediates MPLA-induced augmentation of innate immunocyte functions. To our knowledge, there are no prior published studies defining the contributions of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling to MPLA-induced innate leukocyte mobilization, recruitment, and activation. This question is of importance, as previous work from our group showed that mice primed with MPLA have augmented innate antimicrobial immunity in several models of infection with common bacterial pathogens [15, 17]. Our previous studies show that MPLA priming causes neutrophil mobilization and enhanced neutrophil recruitment to sites of bacterial infection. In addition, the enhancement of antimicrobial immunity by MPLA was dependent on the presence of neutrophils, because neutrophil ablation neutralized the antimicrobial effects of MPLA. Thus, augmentation of neutrophil mobilization and recruitment appears to play a central role in MPLA’s enhancing innate antimicrobial immunity. However, several questions regarding the mechanisms by which MPLA enhances neutrophil-mediated antimicrobial immunity remained, including the underlying signaling mechanisms by which MPLA regulates innate immunocyte activation and recruitment. The present study provides new insight into the relative contributions of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling to augmented innate antimicrobial activity after MPLA treatment.

We examined IRF3 and IKK phosphorylation in BMDMs from WT, MyD88-KO, and TRIF-KO mice at 30 min after MPLA challenge. IRF3 phosphorylation was nearly ablated in BMDMs from TRIF-KO mice, whereas IRF3 phosphorylation was unchanged in BMDMs from MyD88-KO mice compared with WT controls. These results support prior knowledge that IRF3 activation is primarily TRIF dependent [21, 22]. IKK phosphorylation was noted to be significantly decreased in BMDMs from MyD88-KO and TRIF-KO mice. Thus, IKK phosphorylation is induced through both the MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling pathways. We noted significantly greater attenuation of IKK phosphorylation in TRIF-KO than in MyD88-KO BMDMs, which indicates that TRIF-dependent signaling plays a significant role in NF-κB activation in response to MPLA. TRIF-dependent activation of IKK in response to MPLA is likely caused by cross-talk between the TRIF- and MyD88-dependent pathways involving TRAF6 [23]. Overall, our results indicate that TRIF, but not MyD88, is essential for IRF3 phosphorylation, whereas both TRIF- and MyD88-dependent signaling contribute to IKK phosphorylation. These results are consistent with those of our functional studies, which showed that both pathways contribute to neutrophil activation, mobilization, and recruitment.

As part of our analysis, we aimed to evaluate neutrophil recruitment and cytokine production early after MPLA administration. To achieve that, we examined neutrophil mobilization and recruitment at 3 and 6 h after MPLA treatment and observed a surge in blood and intraperitoneal neutrophils in response to MPLA administration. We also observed marked increases in CXCL1, CXCL2, and G-CSF concentrations in plasma and peritoneal lavage fluid within 3 h of MPLA treatment. The functional importance of those cytokines as mediators of MPLA-induced mobilization and recruitment was demonstrated by blockade of MPLA-induced neutrophil trafficking after neutralization of CXCL1, CXCL2, and G-CSF. The CXCR2 ligands and G-CSF are known mediators of neutrophil mobilization and trafficking during infection and in response to challenge with LPS [24–27]. Metkar et al. [28] reported that MPLA will induce CXCR2 ligand expression and facilitate neutrophil recruitment. The present study confirmed and extended those reports by showing a cause-and-effect relationship between CXCR2 ligand and G-CSF production and MPLA-induced neutrophil recruitment. Our study further demonstrates that the MyD88-dependent signaling pathway is primarily responsible for facilitating neutrophil recruitment and regulating production of CXCR2 ligands and G-CSF after MPLA treatment.

In addition to assessing rapid neutrophil recruitment after MPLA injection, further studies characterized the effects of multiple MPLA injections on neutrophil and monocyte recruitment and the contributions of MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling to those processes. Our previous studies show that treatment with MPLA for 2 d before infection provides sustained resistance to polymicrobial sepsis or Pseudomonas burn wound infection [15, 17]. In the present study, we evaluated leukocyte recruitment to the site of MPLA treatment with an identical treatment regimen, as used in those prior studies and noted robust recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes to the site of MPLA injection. We further noted that neutrophil and monocyte recruitment were ablated in MyD88-deficient mice and that monocyte recruitment was also attenuated in TRIF-KO mice. These findings support the key contribution of the MyD88-dependent signaling pathway to MPLA-induced recruitment of innate immunocytes and provide evidence that TRIF-dependent gene products also contribute to monocyte recruitment in response to MPLA.

MPLA treatment induced marked expansion of hematopoietic progenitors in bone marrow, most notably CFU-M, CFU-G, and CFU-GM, corroborating our previous findings [17]. Expansion of those progenitor subsets was significantly diminished in both MyD88- and TRIF-deficient mice, suggesting that gene products regulated by both pathways contribute to progenitor cell expansion. Others have evaluated the contribution of TLRs to hematopoietic progenitor cell expansion during infection and in response to TLR agonists. Shi et al. [29] reported the importance of TLR4 signaling for the expansion of neutrophil progenitors after Escherichia coli challenge. However, they did not examine the contributions of the MyD88- and TRIF-dependent branches. Boettcher and colleagues [30] reported that endothelial cell–derived G-CSF is crucial for expansion of neutrophil precursors in bone marrow after LPS challenge, a process that was diminished in MyD88-deficient mice. That group emphasized the importance of G-CSF for expansion of granulocyte precursors in bone marrow, although GM-CSF is also likely to play a role [31]. Our study shows that MPLA induces G-CSF and bone marrow progenitor expansion in a MyD88-dependent manner. However, the TRIF-dependent signaling pathway also appears to contribute to myeloid progenitor expansion in response to MPLA through mechanisms that remain to be fully defined. A recent report from our lab showed that G-CSF plays a large role in MPLA-induced expansion of myeloid precursors, particularly CFU-G [17]. However, it is likely that other hematopoietic factors, such as IL-3 and GM-CSF, also contribute.

MPLA treatment increased spleen weight and cellularity, particularly when administered via the intravenous route. Intraperitoneal administration of MPLA caused a modest increase in spleen weight but no measured increase in splenic cellularity. Thus, intraperitoneal administration of MPLA had limited impact in the spleen. In contrast, the number of splenic neutrophils and monocytes was significantly increased after intravenous administration of MPLA but, on the basis of the total number, B cells accounted for greater than 75% of the increase in splenic cellularity. Expansion of spleen size and cellularity after MPLA treatment was attenuated in MyD88-KO mice and ablated in TRIF-KO mice, indicating contributions from both signaling pathways. A prior study reported the ability of LPS to induce splenomegaly [32]. However, there are few, if any, reports on the effects of MPLA on spleen weight and cellularity. Immunohistochemical staining showed an increased number of neutrophils and macrophage/monocytes in red pulp with increased splenic follicle size of mice treated with MPLA (data not shown). Neutrophils and monocytes were equally distributed, and no evidence of clustering that would indicate local proliferation was present. The latter results suggest neutrophil mobilization and splenic sequestration, rather than local proliferation, after MPLA treatment. MPLA is known to enhance the antigen-presenting functions of B cells and to enhance antigen-specific immunoglobulin production [8, 33]. The present study indicates that MPLA is able to induce B cell proliferation through processes that require activation of both the MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling pathways. The importance of B cell expansion during augmentation of innate antimicrobial responses after MPLA treatment remains to be determined.

Some studies have demonstrated the ability of LPS to induce emergency myelopoiesis and to induce expansion of cell populations that bear characteristics of MDSCs that were initially identified within solid tumors [30, 34]. MDSCs have been shown to suppress adaptive immune responses in cancer patients [35]. However, their role during acute infections is controversial. We did not specifically assess the MDSC phenotype in our study. However, treatment with MPLA at the doses tested in this study does not cause immune suppression, but rather augments the host response to infection [15, 17]. The neutrophils recruited by MPLA treatment have a mature F4-80-Gr-1+ phenotype, and our prior study show that they possess increased respiratory burst activity [17]. MPLA treatment also expanded the number of neutrophils in bone marrow and spleen. The bone marrow neutrophils are Ly6G+ (which means they are Gr1+) and CD11b+. Thus, they possess surface markers that are characteristic of the MDSC population. However, we did not assess the immunophenotype of those cells by studying their effect on antigen-specific T cell activation. Overall, MPLA-induced neutrophil expansion appears to be beneficial, given that blocking that response ablates the beneficial effects of MPLA [15, 17]. That finding is in agreement with the observations of Moldawer et al. [34] who have commented on the benefits of MDSC expansion as a means of improving immunosurveillance during acute inflammatory insults, such as burns and sepsis.

In further studies, we wanted to gain a better understanding of adhesion molecule expression on neutrophils among all groups of mice. Using the ex vivo model of bone marrow stimulation, we focused on CD11b and L-selectin because of their involvement in neutrophil adhesion during inflammation [36, 37]. In parallel to our previous study [17], upon ex vivo treatment with MPLA, we noted no differences in the percentage of neutrophils expressing CD11b. However, we noted increased CD11b expression per cell, as indicated by increased MFI, as well as a decrease in the percentage of neutrophils expressing L-selectin and a decrease in L-selectin MFI in the WT group. Those alterations were ablated in both MyD88- and TRIF-deficient mice. These results are consistent with the notion that MPLA induces neutrophil activation since shedding of L-selectin and increased CD11b expression are reliable markers of neutrophil activation [38, 39]. Furthermore, that process is dependent on both the MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling pathways.

In conclusion, our data demonstrated TLR4 dependence for mobilization and recruitment of neutrophils in response to MPLA, a process that is regulated primarily by the MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. MPLA treatment induces expansion of splenic and bone marrow myeloid cells and facilitated neutrophil activation. The latter effects are dependent on the presence of both signaling pathways. Our study provides new insight into the independent contributions of the MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signaling pathways during MPLA-induced activation and recruitment of innate immunocytes.

AUTHORSHIP

A.H., J.K.B., and E.R.S. designed and supervised the experiments; A.H., J.K.B., L.L., and B.A.F. performed the experiments; A.H., J.K.B., and B.A.F. analyzed the data; C.M. and J.W. performed some of the experiments; J.K.B., B.A.F., Y.G., N.K.P., and E.R.S. critically revised the article for important intellectual content; A.H. and E.R.S. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health, Institute of General Medicine Grants R01 GM104306 and F32 GM110811.

Glossary

- BMDM

bone marrow–derived macrophage

- CFU

colony forming unit

- CFU-G

granulocyte progenitors

- CFU-GM

granulocyte/macrophage progenitors

- CFU-M

megakaryocyte progenitors

- CXCL

chemokine ligand

- CXCR

chemokine receptor

- G-CSF

granulocyte colony stimulating factor

- IKK

IκB kinase

- IRF

IFN regulator factor

- KO

knockout

- LR

lactated Ringer’s

- MDSC

myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- MFI

mean fluorescent intensity

- MPLA

monophosphoryl lipid A

- My88

myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88

- TRIF

Toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) domain containing adaptor-inducing IFN-β

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Qureshi N., Takayama K., Ribi E. (1982) Purification and structural determination of nontoxic lipid A obtained from the lipopolysaccharide of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 11808–11815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bentala H., Verweij W. R., Huizinga-Van der Vlag A., van Loenen-Weemaes A. M., Meijer D. K., Poelstra K. (2002) Removal of phosphate from lipid A as a strategy to detoxify lipopolysaccharide. Shock 18, 561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maiti K. K., Decastro M., El-Sayed A. B. M. A. A., Foote M. I., Wolfert M. A., Boons G. J. (2010) Chemical synthesis and proinflammatory responses of monophosphoryl lipid A adjuvant candidates. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 80–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pichichero M. E. (2008) Improving vaccine delivery using novel adjuvant systems. Hum. Vaccin. 4, 262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casella C. R., Mitchell T. C. (2008) Putting endotoxin to work for us: monophosphoryl lipid A as a safe and effective vaccine adjuvant. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 3231–3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ZOE-50 Study Group (2015) Efficacy of an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit vaccine in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 2087–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans J. T., Cluff C. W., Johnson D. A., Lacy M. J., Persing D. H., Baldridge J. R. (2003) Enhancement of antigen-specific immunity via the TLR4 ligands MPL adjuvant and Ribi.529. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2, 219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Becker G., Moulin V., Pajak B., Bruck C., Francotte M., Thiriart C., Urbain J., Moser M. (2000) The adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A increases the function of antigen-presenting cells. Int. Immunol. 12, 807–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Veer M., Kemp J., Chatelier J., Elhay M. J., Meeusen E. N. (2012) Modulation of soluble and particulate antigen transport in afferent lymph by monophosphoryl lipid A. Immunol. Cell Biol. 90, 404–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin M., Michalek S. M., Katz J. (2003) Role of innate immune factors in the adjuvant activity of monophosphoryl lipid A. Infect. Immun. 71, 2498–2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldridge J. R., McGowan P., Evans J. T., Cluff C., Mossman S., Johnson D., Persing D. (2004) Taking a toll on human disease: Toll-like receptor 4 agonists as vaccine adjuvants and monotherapeutic agents. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 4, 1129–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogawa T., Nakazawa M., Masui K. (1996) Immunopharmacological activities of the nontoxic monophosphoryl lipid A of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Vaccine 14, 70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masihi K. N., Lange W., Brehmer W., Ribi E. (1986) Immunobiological activities of nontoxic lipid A: enhancement of nonspecific resistance in combination with trehalose dimycolate against viral infection and adjuvant effects. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 8, 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masihi K. N., Ribi E., Lange W., Werner H. (1988) Effects of nontoxic lipid A and endotoxin on resistance of mice to Toxoplasma gondii. J. Biol. Response Mod. 7, 535–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romero C. D., Varma T. K., Hobbs J. B., Reyes A., Driver B., Sherwood E. R. (2011) The Toll-like receptor 4 agonist monophosphoryl lipid a augments innate host resistance to systemic bacterial infection. Infect. Immun. 79, 3576–3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bohannon J. K., Hernandez A., Enkhbaatar P., Adams W. L., Sherwood E. R. (2013) The immunobiology of toll-like receptor 4 agonists: from endotoxin tolerance to immunoadjuvants. Shock 40, 451–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bohannon J. K., Luan L., Hernandez A., Afzal A., Guo Y., Patil N. K., Fensterheim B., Sherwood E. R. (2015) Role of G-CSF in monophosphoryl lipid A-mediated augmentation of neutrophil functions after burn injury. J. Leukoc. Biol. 99, 629–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gandhapudi S. K., Chilton P. M., Mitchell T. C. (2013) TRIF is required for TLR4 mediated adjuvant effects on T cell clonal expansion. PLoS One 8, e56855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mata-Haro V., Cekic C., Martin M., Chilton P. M., Casella C. R., Mitchell T. C. (2007) The vaccine adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A as a TRIF-biased agonist of TLR4. Science 316, 1628–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolanowski S. T., Dieker M. C., Lissenberg-Thunnissen S. N., van Schijndel G. M., van Ham S. M., ten Brinke A. (2014) TLR4-mediated pro-inflammatory dendritic cell differentiation in humans requires the combined action of MyD88 and TRIF. Innate Immun. 20, 423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kopp E., Medzhitov R. (2003) Recognition of microbial infection by Toll-like receptors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 15, 396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stockinger S., Reutterer B., Schaljo B., Schellack C., Brunner S., Materna T., Yamamoto M., Akira S., Taniguchi T., Murray P. J., Müller M., Decker T. (2004) IFN regulatory factor 3-dependent induction of type I IFNs by intracellular bacteria is mediated by a TLR- and Nod2-independent mechanism. J. Immunol. 173, 7416–7425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato S., Sugiyama M., Yamamoto M., Watanabe Y., Kawai T., Takeda K., Akira S. (2003) Toll/IL-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-beta (TRIF) associates with TNF receptor-associated factor 6 and TANK-binding kinase 1, and activates two distinct transcription factors, NF-kappa B and IFN-regulatory factor-3, in the Toll-like receptor signaling. J. Immunol. 171, 4304–4310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Del Rio L., Bennouna S., Salinas J., Denkers E. Y. (2001) CXCR2 deficiency confers impaired neutrophil recruitment and increased susceptibility during Toxoplasma gondii infection. J. Immunol. 167, 6503–6509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wareing M. D., Shea A. L., Inglis C. A., Dias P. B., Sarawar S. R. (2007) CXCR2 is required for neutrophil recruitment to the lung during influenza virus infection, but is not essential for viral clearance. Viral Immunol. 20, 369–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stadtmann A., Zarbock A. (2012) CXCR2: from bench to bedside. Front. Immunol. 3, 263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingersoll M. A., Kline K. A., Nielsen H. V., Hultgren S. J. (2008) G-CSF induction early in uropathogenic Escherichia coli infection of the urinary tract modulates host immunity. Cell. Microbiol. 10, 2568–2578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metkar S., Kim K. S., Silver J., Goyert S. M. (2012) Differential expression of CD14-dependent and independent pathways for chemokine induction regulates neutrophil trafficking in infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 92, 389–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi X., Siggins R. W., Stanford W. L., Melvan J. N., Basson M. D., Zhang P. (2013) Toll-like receptor 4/stem cell antigen 1 signaling promotes hematopoietic precursor cell commitment to granulocyte development during the granulopoietic response to Escherichia coli bacteremia. Infect. Immun. 81, 2197–2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boettcher S., Gerosa R. C., Radpour R., Bauer J., Ampenberger F., Heikenwalder M., Kopf M., Manz M. G. (2014) Endothelial cells translate pathogen signals into G-CSF-driven emergency granulopoiesis. Blood 124, 1393–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manz M. G., Boettcher S. (2014) Emergency granulopoiesis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 302–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liverani E., Rico M. C., Yaratha L., Tsygankov A. Y., Kilpatrick L. E., Kunapuli S. P. (2014) LPS-induced systemic inflammation is more severe in P2Y12 null mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 95, 313–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu X., Liu R., Zhu N. (2013) Enhancement of humoral and cellular immune responses by monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA) as an adjuvant to the rabies vaccine in BALB/c mice. Immunobiology 218, 1524–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cuenca A. G., Delano M. J., Kelly-Scumpia K. M., Moreno C., Scumpia P. O., Laface D. M., Heyworth P. G., Efron P. A., Moldawer L. L. (2011) A paradoxical role for myeloid-derived suppressor cells in sepsis and trauma. Mol. Med. 17, 281–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pico de Coaña Y., Poschke I., Gentilcore G., Mao Y., Nyström M., Hansson J., Masucci G. V., Kiessling R. (2013) Ipilimumab treatment results in an early decrease in the frequency of circulating granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells as well as their Arginase1 production. Cancer Immunol. Res. 1, 158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.García-Vicuña R., Díaz-González F., González-Alvaro I., del Pozo M. A., Mollinedo F., Cabañas C., González-Amaro R., Sánchez-Madrid F. (1997) Prevention of cytokine-induced changes in leukocyte adhesion receptors by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs from the oxicam family. Arthritis Rheum. 40, 143–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schubert N., Berthold T., Muschter S., Wesche J., Fürll B., Reil A., Bux J., Bakchoul T., Greinacher A. (2013) Human neutrophil antigen-3a antibodies induce neutrophil aggregation in a plasma-free medium. Blood Transfus. 11, 541–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rainer T. H., Lam N. Y., Chan T. Y., Cocks R. A. (2000) Early role of neutrophil L-selectin in posttraumatic acute lung injury. Crit. Care Med. 28, 2766–2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paugam C., Chollet-Martin S., Dehoux M., Chatel D., Brient N., Desmonts J. M., Philip I. (1997) Neutrophil expression of CD11b/CD18 and IL-8 secretion during normothermic cardiopulmonary bypass. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 11, 575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]