Saba and collaborators show that dendritic cells generate the thymic sphingosine-1-phosphate gradient and regulate T cell egress.

Abstract

T cell egress from the thymus is essential for adaptive immunity and involves chemotaxis along a sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) gradient. Pericytes at the corticomedullary junction produce the S1P egress signal, whereas thymic parenchymal S1P levels are kept low through S1P lyase (SPL)–mediated metabolism. Although SPL is robustly expressed in thymic epithelial cells (TECs), in this study, we show that deleting SPL in CD11c+ dendritic cells (DCs), rather than TECs or other stromal cells, disrupts the S1P gradient, preventing egress. Adoptive transfer of peripheral wild-type DCs rescued the egress phenotype of DC-specific SPL knockout mice. These studies identify DCs as metabolic gatekeepers of thymic egress. Combined with their role as mediators of central tolerance, DCs are thus poised to provide homeostatic regulation of thymic export.

Introduction

The thymus supports the development of BM-derived lymphoid progenitors into mature T cells through positive and negative selection. The population of mature T cells egressing from the thymus exhibits a diverse repertoire of antigen recognition capable of mounting effective protective immunity, yet lacking autoreactivity. Tight regulation of thymic egress ensures full maturation and prevents potentially dangerous autoreactive T cells from entering the circulation (Gräler et al., 2005). Although the vast majority of thymocytes are eventually culled through the processes of positive and negative selection, ∼2% reach the final stage of maturity, exiting from the thymus and entering into the circulation (Berzins et al., 1999).

Thymic egress is an actively regulated process. Mature T cells egress from the thymus by chemotaxis in response to a sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) gradient (Schwab et al., 2005). S1P levels are highest in plasma and lowest in the lymphoid organs (Rivera et al., 2008). S1P is a ubiquitous bioactive sphingolipid that regulates diverse immunological functions including hematopoietic cell trafficking, vascular permeability, and mast cell activation (Spiegel and Milstien, 2011). S1P mediates many of its actions by signaling through its five cognate G protein–coupled receptors, S1P1–5. In the final stages of their maturation, thymocytes up-regulate the transcription factor Krüppel-like factor 2 and its target gene S1P1 (Carlson et al., 2006). S1P1 expression on mature single-positive (SP) cells enables their entry into the circulation after encountering extracellular S1P produced by neural crest–derived perivascular cells located at the corticomedullary junction (Matloubian et al., 2004; Zachariah and Cyster, 2010). There is evidence that activation of thymocytes such as by antigen challenge, infection, and cytokines is capable of modulating T cell export from the thymus (Nunes-Alves et al., 2013). However, the mechanisms responsible for this phenomenon are poorly understood.

Two sphingosine kinases are capable of phosphorylating sphingosine to form S1P, and five lipid phosphatases are capable of dephosphorylating S1P, thereby regenerating sphingosine (Pyne et al., 2009). In contrast to this reversible reaction, the enzyme S1P lyase (SPL), a resident protein of the ER membrane, degrades S1P irreversibly, providing global control over circulating and tissue S1P levels (Pyne et al., 2009). SPL expression is robust in mouse thymus starting early in development and continuing through adult life (Borowsky et al., 2012; Newbigging et al., 2013). A critical role for SPL in lymphocyte egress was revealed when the food additive tetrahydroxybutylimidazole was shown to cause lymphopenia via SPL inhibition (Schwab et al., 2005). Similarly, genetically modified mice globally deficient in SPL are lymphopenic (Vogel et al., 2009). The lymphopenia associated with SPL suppression is presumed to result from disruption of the S1P gradient maintained by thymic SPL activity (Schwab et al., 2005). Both S1P1 antagonism and SPL inhibition have been explored as therapeutic strategies for treatment of autoimmune disease by blocking lymphocyte egress from the thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs (Kappos et al., 2006; Bagdanoff et al., 2010; Weiler et al., 2014).

Despite the importance of S1P signaling in lymphocyte trafficking, little is known about the compartmentalization of S1P metabolism in the thymus and the cell types responsible for producing the S1P gradient. Thymic stromal cells provide the matrix and signaling cues necessary to foster proper thymocyte development. The stroma contains thymic epithelial cells (TECs) and vascular and perivascular cells, as well as BM-derived antigen-presenting cell types including macrophages, B cells, and DCs (Rodewald, 2008). B cells and DCs make up a small percentage of the stroma and are located mainly in the medulla and corticomedullary region (Perera et al., 2013). Thymic DCs have been shown to cross-present self-antigens acquired from medullary TECs to developing thymocytes and to facilitate the generation of regulatory T cells (Hubert et al., 2011; Lei et al., 2011). Peripheral DCs can recirculate to the thymus and also contribute to thymocyte selection events (Bonasio et al., 2006; Proietto et al., 2008). However, a role for DCs in homeostatic regulation of mature T cell egress from the thymus has not been identified.

In this study, we sought to identify the stromal cell population responsible for metabolizing S1P and thereby maintaining the chemical gradient required for thymic egress. Importantly, these studies identify DCs as metabolic gatekeepers of thymic egress. Combined with their role as mediators of central tolerance, DCs are thus poised to provide homeostatic regulation of thymic export.

Results

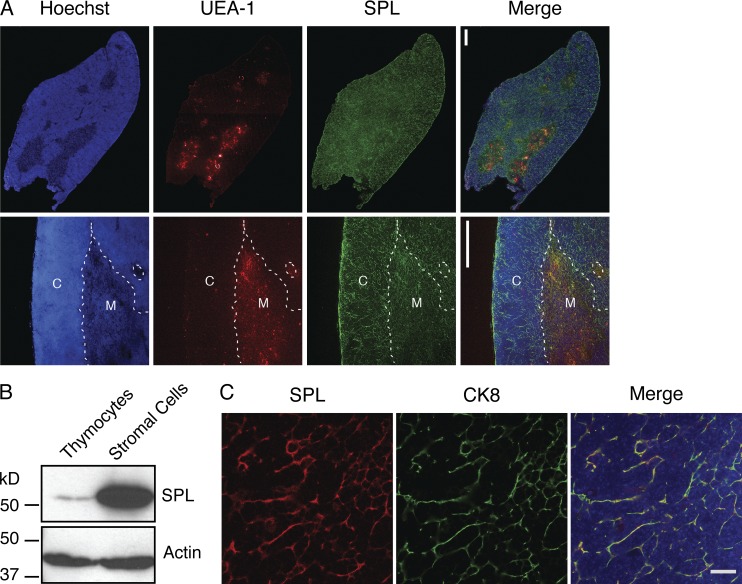

SPL expression in TECs is not required for lymphocyte egress

To determine the anatomical regions in which SPL is expressed, we performed immunofluorescence staining to detect SPL in thymuses of adult C57BL/6 mice. Costaining with UEA-1, a marker of the thymic medulla, was used to delineate cortical and medullary thymic regions. Strong SPL expression was observed in both cortical and medullary regions of the thymus (Fig. 1 A). The SPL expression pattern observed in the thymic cortex was reticular and suggested robust expression in thymic stroma. Western blotting of lysates prepared from enriched thymic stromal cells or thymocytes further established that SPL is abundantly expressed in thymic stromal cells but is expressed at barely detectible levels in thymocytes (Fig. 1 B). A major cellular component of the stroma is the TEC, wherein SPL is highly expressed (Borowsky et al., 2012). To confirm these findings, immunofluorescence microscopy was performed on frozen sections of WT mouse thymuses costained using antibodies against SPL and the epithelial marker cytokeratin 8 (CK8). SPL expression was robust in TECs, overshadowing SPL expression in any other thymic cell type (Fig. 1 C).

Figure 1.

SPL is highly expressed in TECs. (A) Confocal microscopy of WT thymus sections. 6-µm cryosections were fixed and stained with a lectin delineating the medulla (UEA-1), SPL antibody, and Hoechst to stain the nuclei. The top row shows one lobe of the thymus. The bottom row shows a close-up image of the cortex (C) and medulla (M). Dotted lines delineate the corticomedullary junction. SPL is expressed in all sections of the thymus. Bars, 100 µm. Images are representative of three thymuses analyzed. (B) Western blotting to detect SPL in whole cell extracts of thymocytes and thymic stromal cells separated by mechanical dissociation. Actin was used as a loading control. (C) SPL expression in TECs by immunofluorescence detection and confocal microscopy. Thymic sections from WT mice were stained for CK8 to detect TECs and SPL. DAPI staining (blue) indicates nuclei. The merged image shows SPL colocalizing with CK8. The image is representative of three thymuses analyzed. Bar, 20 µm. Shown are the representative results of three independent experiments.

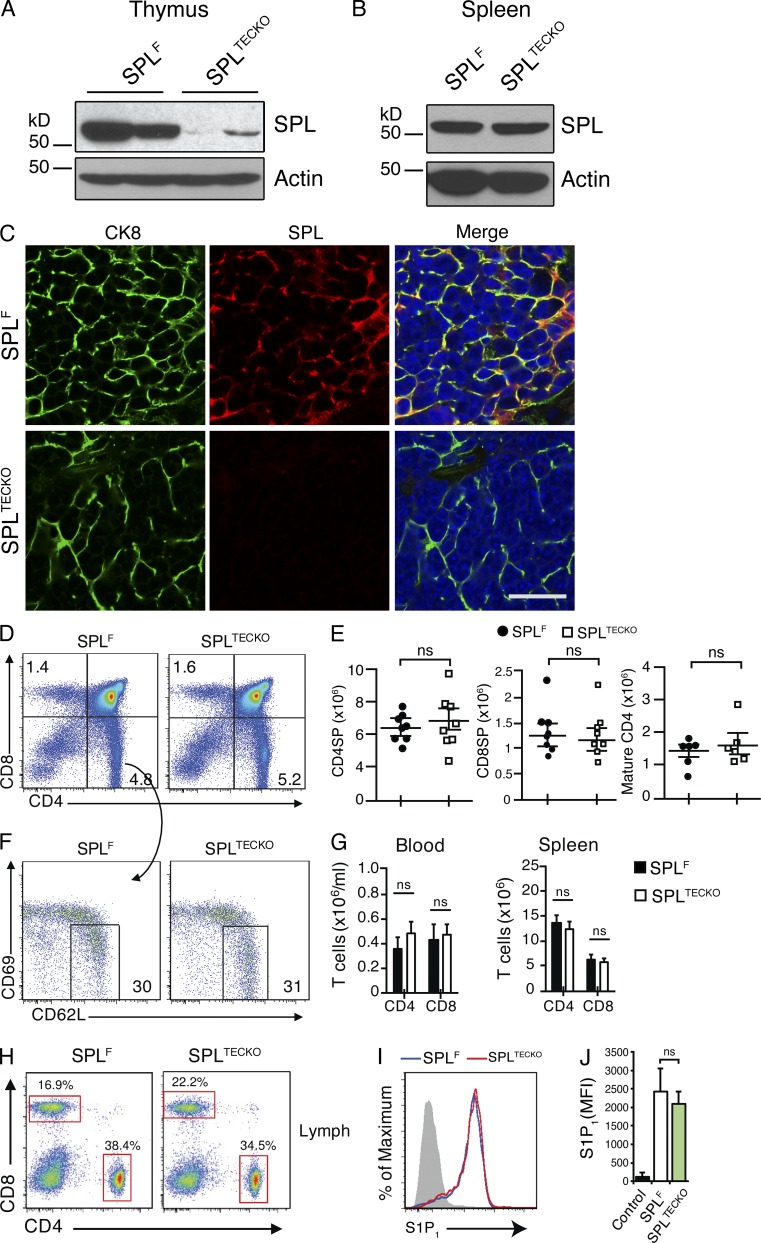

To determine the role of TEC SPL in thymic egress, we crossed mice harboring a floxed allele for Sgpl1 (Sgpl1fl/fl) previously generated in our laboratory (Degagné et al., 2014) with transgenic mice in which the Cre transgene was under the control of the FoxN1 promoter. FoxN1 drives recombination of floxed alleles in both cortical and medullary TECs (Gordon et al., 2007). Sgpl1fl/flFoxN1-Cre (designated SPLTECKO) mice appeared healthy. To confirm gene recombination in SPLTECKO mice, Western blotting was performed to detect SPL in tissue homogenates of whole thymuses from Sgpl1fl/fl (designated SPLF) and SPLTECKO mice. As shown in Fig. 2 A, SPL expression was nearly absent in thymuses from SPLTECKO mice. In contrast, no appreciable difference in SPL levels was observed in the splenic stromal cells of SPLTECKO and SPLF mice, demonstrating that absence of SPL expression was restricted to the thymus (Fig. 2 B). Furthermore, thymic sections from SPLTECKO mice stained with SPL antibody showed no detectable SPL in CK8+ cells, indicating highly efficient recombination in TECs (Fig. 2 C).

Figure 2.

SPL deficiency in TECs does not affect thymic egress. (A and B) Western blots detecting SPL expression in homogenates of SPLF and SPLTECKO mouse thymuses (A) and spleens (B). Actin was used as a loading control. SPL expression is lost in the thymus but not the spleen of SPLTECKO mice. (C) Immunofluorescence detection of SPL in frozen thymic sections from SPLF and SPLTECKO mice using CK8 to detect TECs, SPL antibody, and DAPI (blue). At the bottom (SPLTECKO), typical stromal staining for SPL is lost. Bar, 20 µm. Images are representative of three mice analyzed. (D) Flow cytometric analysis dot plots of total thymocytes in the thymuses of representative SPLF and SPLTECKO mice. Numbers indicate percentage of cells in the indicated quadrant. (E) Absolute numbers of CD4SP, CD8SP, and mature CD4SP cells in thymuses of SPLF and SPLTECKO mice (n = 6 mice/group for mature CD4SP, and n = 8 mice/group in CD4SP and CD8SP cells). (F) Flow cytometric analysis dot plots of CD4SP thymocytes of representative SPLF and SPLTECKO mice. Mature CD4SP and CD8SP T cells were gated as CD62LHiCD69Lo. Numbers indicate percentage of cells in the indicated gate. (G) Absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleens and blood of SPLF and SPLTECKO mice as indicated (Spleen analysis: SPLF, n = 11; SPLTECKO, n = 11. Blood analysis: SPLF, n = 8; SPLTECKO, n = 8). (E and G) Graphs represent a compilation of four independent experiments. (H) Dot plots show CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in lymph fluid, collected from the thoracic duct, from SPLF and SPLTECKO representative mice. Percentages correspond to the indicated gate. (I) S1P1 cell surface expression on mature CD4SP T cells from representative SPLF and SPLTECKO mice. The gray histogram denotes negative isotype control, and blue and red histograms denote a representative of SPLTECKO and SPLF, respectively. (J) Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of S1P1 (n = 3 mice/group). The results shown are representative of two independent experiments. (E, G, and J) Data are shown as mean ± SD for two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests.

To test whether SPLTECKO mice exhibit a block in lymphocyte egress, absolute numbers of SP and mature T cells were measured in thymuses of SPLF and SPLTECKO mice. We found no difference in the absolute numbers or percentages of mature CD4SP (CD4+CD8−CD62LHiCD69lo) cells among total CD4SP (CD4+CD8−) thymocytes in SPLTECKO mice compared with SPLF (Fig. 2, E and F). Similarly, no difference was detected in absolute numbers and percentages of CD4SP and CD8SP thymocytes between the two groups (Fig. 2, D and E). In addition, loss of SPL expression in TECs had no impact on the percentage or absolute numbers of T cells in secondary lymphoid organs, blood, and lymph of SPLTECKO mice when compared with SPLF (Fig. 2, G and H).

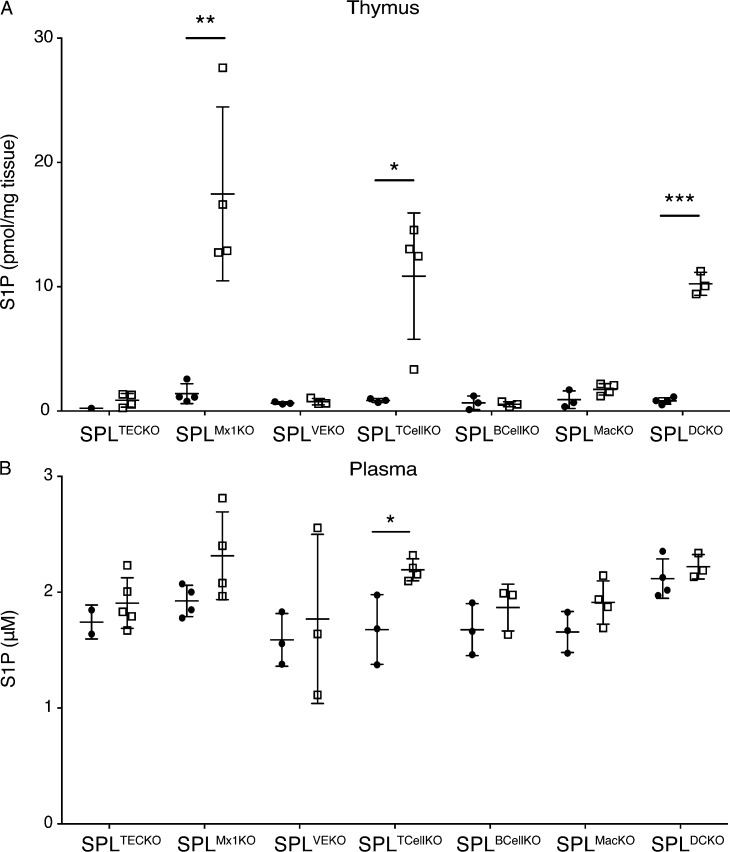

Elevation of S1P levels in the thymus by pharmacological agents or genetic approaches disrupts the S1P gradient and impairs the exit of mature SP cells from the thymus to blood (Schwab et al., 2005; Vogel et al., 2009; Weber et al., 2009). To explore the effect of SPL deficiency in TECs on the S1P gradient, S1P levels in thymuses and plasma were measured by liquid chromatography (LC) mass spectrometry (MS). Despite the high SPL expression in TECs, SPLTECKO mice showed no appreciable difference in thymic or plasma S1P levels compared with SPLF, as shown in Fig. 3 (A and B).

Figure 3.

S1P levels in thymus and plasma. (A and B) S1P levels in mouse thymuses (A) and plasma (B) of various mouse lines. Solid dots represent individual SPLF control, and squares represent specific SPLKO indicated at the bottom of the graph. Three to five mice per group were analyzed. Mean values ± SD are shown. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 for two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests between SPLF and each KO strain. Shown is a representative of two independent experiments.

Upon binding to extracellular S1P within their local environment, mature T cells internalize S1P1, and high local S1P levels produce sustained receptor internalization (Liu et al., 1999). The surface S1P1 expression level in mature SP T cells of SPLTECKO mice was similar to that of SPLF (Fig. 2, I and J). This finding suggested that the S1P levels in the vicinity of mature SP T cells were not sufficiently different from controls to influence S1P1 residence time at the plasma membrane. Collectively, these results show that the pool of SPL residing within TECs has no influence on the S1P gradient and, thus, no influence on thymic egress.

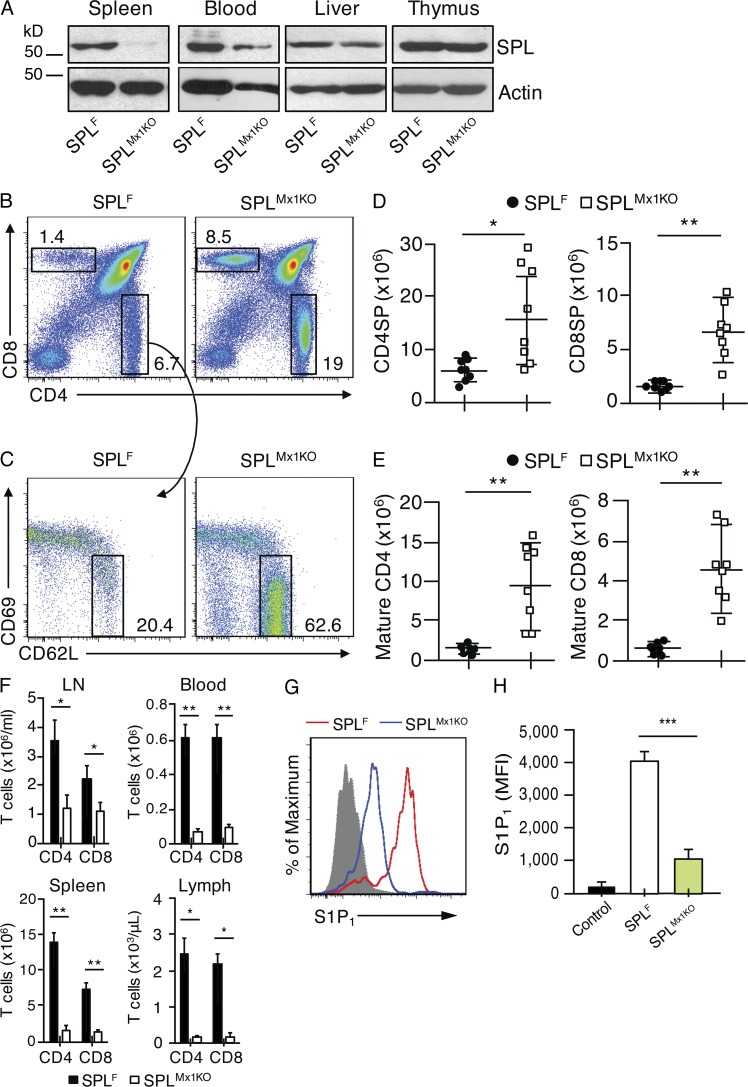

Endothelial cell SPL is not essential for mediating thymic egress

Besides TECs, the thymus is largely comprised of vascular or BM-derived blood cells. To explore whether SPL contained in endothelial and blood cells are required for lymphocyte egress, we crossed Sgpl1fl/fl mice with Mx1-Cre mice, wherein Cre transgene expression is driven by the interferon-inducible Mx1 promoter. The resulting Sgpl1fl/flMx1-Cre mice can be induced to undergo recombination of Sgpl1 in interferon-sensitive cells by treatment with the interferon inducer polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly[I:C]; Kühn et al., 1995). Sgpl1fl/flMx1-Cre pups were induced at 1 wk of age with poly(I:C). Henceforth, these are referred to as SPLMx1KO mice. In SPLMx1KO mice, SPL expression was significantly reduced in blood cells, undetectable in spleen, and modestly decreased in liver (Fig. 4 A). In contrast, there was no notable difference in thymic SPL expression between SPLMx1KO and SPLF mice (Fig. 4 A). These results establish the efficiency of recombination in the SPLMx1KO mice and confirm that TECs represent the main source of thymic SPL.

Figure 4.

SPL deficiency in BM and endothelial cells blocks thymic egress. (A) Western blotting to detect SPL in homogenates of spleens, white blood cells, liver, and thymuses isolated from SPLF and SPLMx1KO mice. Actin antibody was used as a loading control. (B) Flow cytometric analysis dot plots of total thymocytes of representative SPLF and SPLMx1KO mice. Numbers indicate the percentage of cells in the indicated gate. (C) Flow cytometric analysis dot plots of CD4SP thymocytes of representative SPLF and SPLMx1KO mice. Mature CD4SP and CD8SP T cells were gated as CD62LHiCD69Lo. Numbers indicate percentage of cells in the indicated gate. (D) Absolute numbers of CD4SP and CD8SP in SPLF and SPLMx1KO mice corresponding to the dot plot shown in B, summarized in graph format. (E) Absolute numbers of mature CD4SP and mature CD8SP from SPLF and SPLMx1KO mice corresponding to the dot plot shown in C, summarized in graph format. (F) Absolute numbers of T cells in the mesenteric LNs, blood, spleen, and lymph fluid of SPLF (black bars) and SPLMx1KO (white bars) mice. (D–F) n = 8 mice/group. Graphs represent a compilation of three independent experiments. (G) S1P1 surface abundance on mature CD4SP T cells in representative SPLF or SPLMx1KO mice. The gray histogram represents a negative isotype control. (H) Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of S1P1 (n = 3 mice/group). Shown is a representative of two independent experiments. (D–F and H) Mean values ± SD are shown. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 for two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests between SPLF and SPLMx1KO mice.

We next examined whether thymic egress was compromised in SPLMx1KO mice lacking SPL in both hematopoietic and endothelial cells. We observed a twofold increase in CD4SP and CD8SP, as well as a fivefold increase in mature CD4SP and mature CD8SP T cells in the thymuses of SPLMx1KO mice compared with SPLF mice (Fig. 4, B–E). A concomitant depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was observed in the blood, lymph, spleens, and mesenteric LNs of SPLMx1KO mice compared with SPLF mice (Fig. 4 F).

To investigate how loss of SPL expression in hematopoietic and endothelial cells affected the S1P gradient, we measured S1P levels in thymuses and plasma. We observed a striking 12-fold increase in thymic S1P levels but no change in plasma S1P levels in SPLMx1KO mice compared with SPLF mice (Fig. 3, A and B). Furthermore, the surface expression of S1P1 in mature CD4SP cells of SPLMx1KO mice was reduced by two thirds compared with that of mature CD4SP cells of SPLF mice, indicating that the mature T cells were encountering very high local extracellular S1P levels, i.e., disruption of the S1P gradient (Fig. 4, G and H).

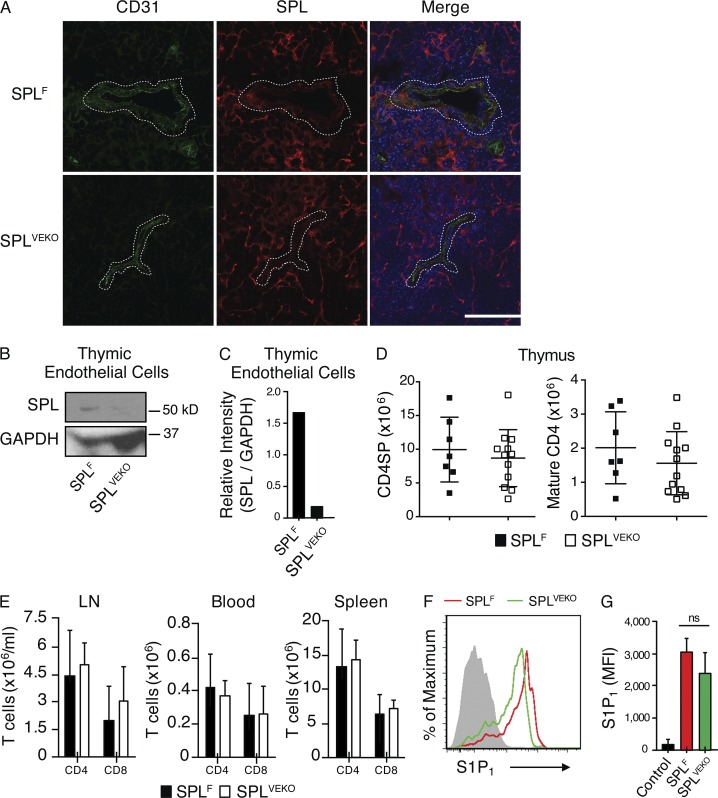

These findings suggest that SPL is required in endothelial cells, hematopoietic cells, or both to maintain the S1P gradient and support mature T cell egress. To distinguish among these possibilities, we first investigated the contribution of endothelial SPL to thymic output. To analyze the expression of SPL in endothelial cells, frozen sections of thymuses from SPLF mice were coimmunostained using antibodies against SPL and the endothelial marker CD31. Colocalization of SPL and CD31 signals demonstrated that endothelial cells express SPL (Fig. 5 A). We then crossed Sgpl1fl/fl mice with Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 transgenic mice, which upon induction with tamoxifen resulted in endothelial-specific recombination of the Sgpl1 gene (Wang et al., 2010). Thymic sections from tamoxifen-induced Sgpl1fl/flCdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 mice (designated SPLVEKO) and controls were coimmunostained with SPL and CD31 antibodies, and thymic endothelial cells (CD31+ CD45− CK8−) were sorted and analyzed by Western blotting. Thymic endothelial cells from SPLVEKO mice lacked SPL expression, confirming efficient recombination (Fig. 5, A–C).

Figure 5.

SPL deficiency in endothelial cells does not block thymic egress. (A) Immunofluorescence was performed on frozen thymic sections from SPLF and SPLVEKO mice using CD31, SPL antibody, and DAPI (blue) followed by staining with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies. Dotted lines delineate a blood vessel. Bar, 100 µm. Images shown are representative of five thymuses analyzed. (B) Western blot of whole-cell extracts of thymic endothelial cells (CD31+ CD45− CK8−) isolated from SPLF and SPLVEKO mice. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) Relative intensity of Western blot bands of SPL/GAPDH. The results shown are representative of two independent experiments. (D) Absolute number of CD4SP and mature CD4SP T cells from SPLF and SPLVEKO mice. (E) Absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the blood, mesenteric LN, and spleen. (D and E) Graphs represent a compilation of four independent experiments. SPLF, n = 7; SPLVEKO, n = 12. (F) S1P1 surface abundance on mature CD4SP T cells in representative SPLF and SPLVEKO mice. The gray histogram shows a negative isotype control. (G) Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of S1P1 (SPLF, n = 3; SPLVEKO, n = 3). The results shown are representative of two independent experiments. (D, E, and G) Data are shown as mean ± SD for two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests.

SPLVEKO mice exhibited normal thymic egress, as demonstrated by a lack of retained CD4SP and mature CD4SP T cells in the thymus (Fig. 5 D), and no difference from SPLF mice in the number of T cells in secondary lymphoid organs and blood (Fig. 5 E). Analysis of S1P levels in the thymuses and plasma of SPLVEKO mice revealed no significant differences compared with SPLF (Fig. 3, A and B). Mature CD4SP T cells of SPLVEKO mice also expressed similar levels of surface S1P1 as those of SPLF, indicating appropriately low extracellular S1P levels in their vicinity (Fig. 5, F and G). Thus, SPL activity in the endothelial cell compartment is not essential for generating the S1P gradient or promoting thymic egress.

A hematopoietic cell type harbors the SPL activity required for thymic egress

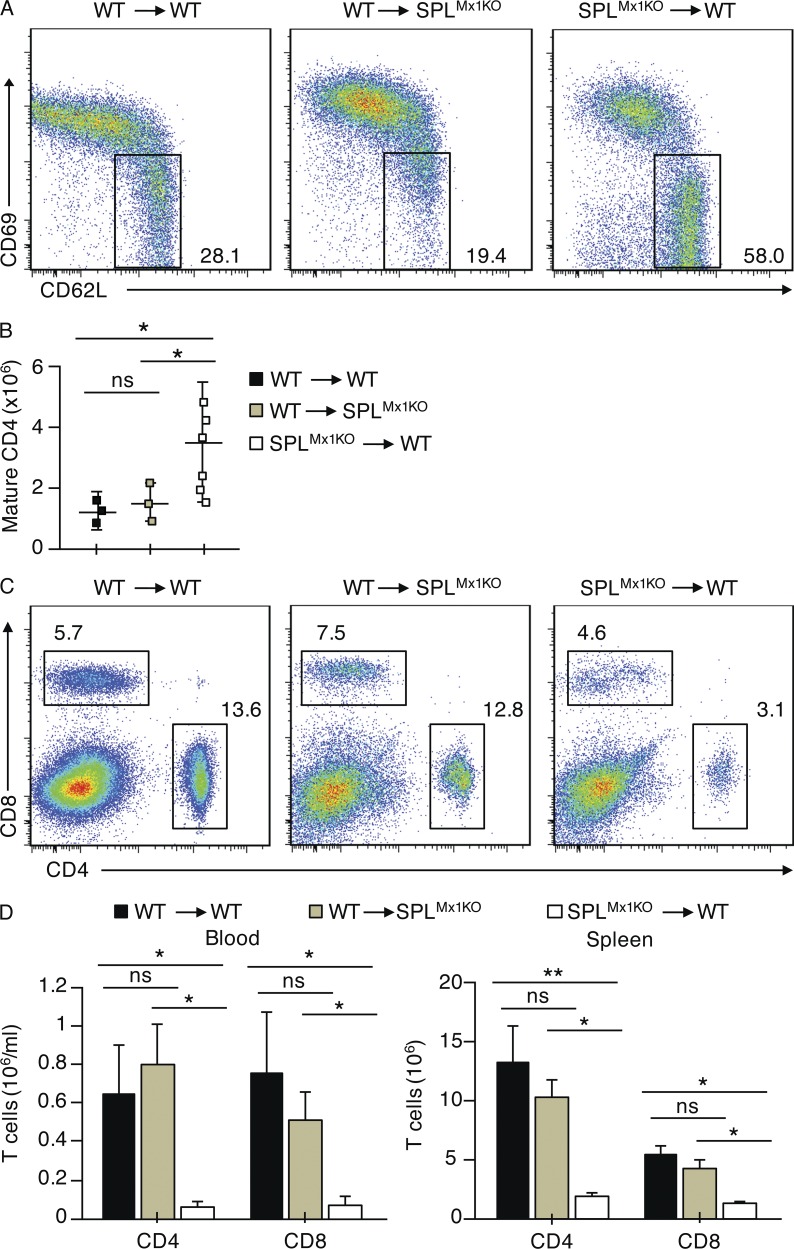

Our findings suggested that SPL deficiency in a hematopoietic cell type was responsible for the retention of mature SP T cells observed in SPLMx1KO mice. To confirm this hypothesis, BM reconstitution experiments were performed in which irradiated SPLMx1KO mice were transplanted with BM from WT CD45.1 congenic mice. We showed that BM transplantation effectively rescued the thymic egress defect of SPLMx1KO mice, as shown by the normal proportions of mature CD4SP T cells in the thymus and normal T cell numbers in the peripheral blood 7 wk after transplantation (Fig. 6, A–D). In parallel, the block in thymic egress observed in SPLMx1KO mice could be recapitulated in WT CD45.1 congenic mice transplanted with BM from SPLMx1KO mice, whereas WT mice transplanted with WT BM exhibited normal egress (Fig. 6, A–D). These findings confirm that SPL is required in BM-derived hematopoietic cells to promote mature T cells’ egress from the thymus.

Figure 6.

SPL expression is required in hematopoietic cells for thymic egress. (A–D) SPLMx1KO or congenic CD45.1 (WT) mice were lethally irradiated, and BM was reconstituted from SPLMx1KO or WT mice as indicated. Chimeric mice were analyzed 7 wk after transplantation. (A) Dot plots show CD4SP thymocytes and mature CD4SP cells gated as CD62LHiCD69Lo from a representative recipient mouse. Numbers indicate percentage of cells in the indicated gate. (B) Absolute numbers of mature CD4SP T cells among CD4SP cells are summarized in graph format (n = 3–6 mice/group). (C) Flow cytometric analysis dot plots of blood lymphocytes in representative recipient mice reconstituted from SPLMx1KO or WT mice as indicated. Numbers indicate percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. (D) Absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the blood and spleen of WT recipients transplanted with WT marrow (black bars), WT recipients transplanted with SPLMx1KO marrow (white bars), and SPLMx1KO recipients transplanted with WT marrow (green bars) are summarized in bar graph format (n = 3–6 recipient mice/group). (B and D) Graphs represent a compilation of three independent experiments. Mean values ± SD are shown. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 for two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests between recipient mice as indicated.

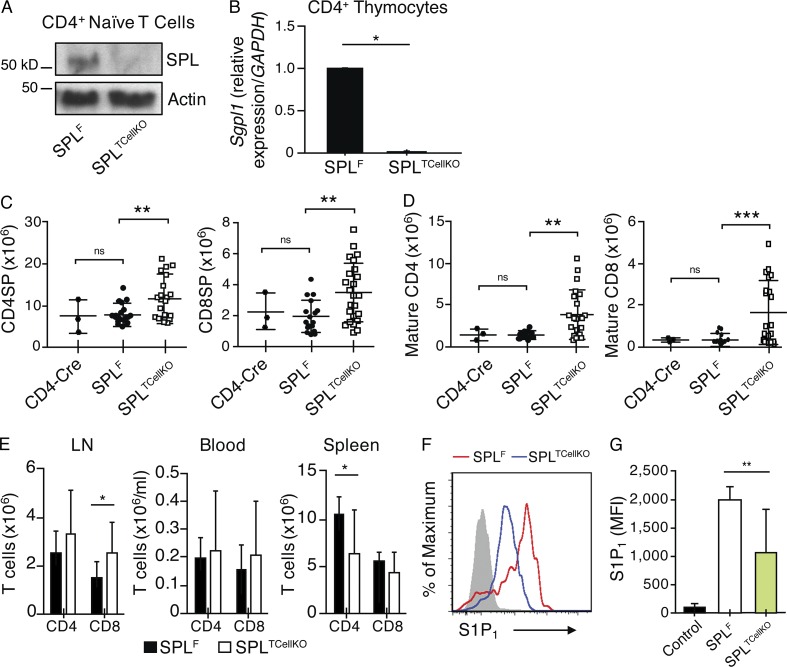

SPL expression in mature T cells contributes to efficient thymic egress

Four major hematopoietic cell types are present in the thymus, which include thymocytes, B cells, macrophages, and DCs. To investigate the possibility that SPL activity is required in mature SP T cells to promote their egress, we generated Sgpl1fl/flCD4-Cre (designated SPLTCellKO) mice, in which recombination of the floxed allele was induced in thymocytes at the double positive (DP) stage. SPLTCellKO mice exhibited no detectable expression of SPL protein or Sgpl1 messenger RNA in splenic CD4+ T cells and CD4+ thymocytes based on immunoblotting and quantitative RT-PCR, respectively (Fig. 7, A and B). We observed a twofold increase in SP and threefold increase in mature T cells in the thymuses of SPLTCellKO mice compared with floxed control mice (SPLF), indicating that some mature T cells are retained in the thymus of SPLTCellKO mice (Fig. 7, C and D). To verify that this phenotype was not associated with the Cre transgene itself, we analyzed a second control group that expressed the CD4-Cre transgene in a nonfloxed background (CD4-Cre). As expected, CD4-Cre mice exhibited a normal egress phenotype indistinguishable from that of SPLF mice, confirming that CD4-Cre itself was not responsible for the mature T cell accumulation observed in SPLTCellKO mice (Fig. 7, C and D). Peripheral CD4+ T cells were not reduced in the blood, although they were modestly reduced in the spleen compared with controls, whereas CD8+ T cells were increased in the mesenteric LNs of SPLTCellKO mice (Fig. 7 E). Overall, the disruption of SPL in thymocytes led to retention of mature T cells but did not recapitulate the severe egress phenotype and peripheral lymphopenia characteristic of SPL null mice or SPLMx1KO mice.

Figure 7.

SPL expression in mature T cells contributes to efficient egress. (A) Western blot to detect SPL in CD45RBHiCD4+ T cells isolated from spleens of SPLF and SPLTCellKO mice. Splenic T cells were sorted from SPLF and SPLTCellKO mice and prepared for Western blotting. Actin antibody was used as a loading control. (B) CD4+ thymocytes were flow sorted from SPLF and SPLTCellKO mouse thymuses. Purified cells were pooled from four mice/group. Gene expression of SPL (Sgpl1) was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR. (C) Absolute numbers of CD4SP (CD4-Cre, n = 3; SPLF, n = 15; SPLTCellKO, n = 19) and CD8SP (CD4-Cre, n = 3; SPLF, n = 16; SPLTCellKO, n = 24) thymocytes. (D) Mature CD4SP (CD4-Cre, n = 3; SPLF, n = 10; SPLTCellKO, n = 18) and mature CD8SP (CD4-Cre, n = 3; SPLF, n = 10; SPLTCellKO, n = 20) T cells. (E) Absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen, blood, and mesenteric LN of SPLF and SPLTCellKO mice as indicated (SPLF, n = 7; SPLTCellKO, n = 10). (C–E) Graphs represent a compilation of six independent experiments. (F) S1P1 surface abundance on mature CD4SP T cells in representative SPLF and SPLTCellKO mice as indicated. The gray histogram represents a negative isotype control. (G) Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of S1P1 (SPLF, n = 5; SPLTCellKO, n = 11). The graph represents a compilation of four independent experiments. (B–E and G) Mean values ± SD are shown. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001 for two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests between SPLF and SPLTCellKO.

S1P levels in the thymus of SPLTCellKO mice were 12-fold higher than in SPLF mice, and plasma levels were increased (Fig. 3, A and B). Furthermore, the mean S1P1 surface abundance on mature CD4SP T cells from SPLTCellKO mice was reduced compared with that of SPLF mice, indicating SPLTCellKO mature T cells were encountering higher than normal local extracellular S1P levels (Fig. 7, F and G). These cumulative results demonstrate that SPL intrinsic to mature T cells facilitates their efficient egress from the thymus but is unlikely to represent the main metabolic regulator of this process.

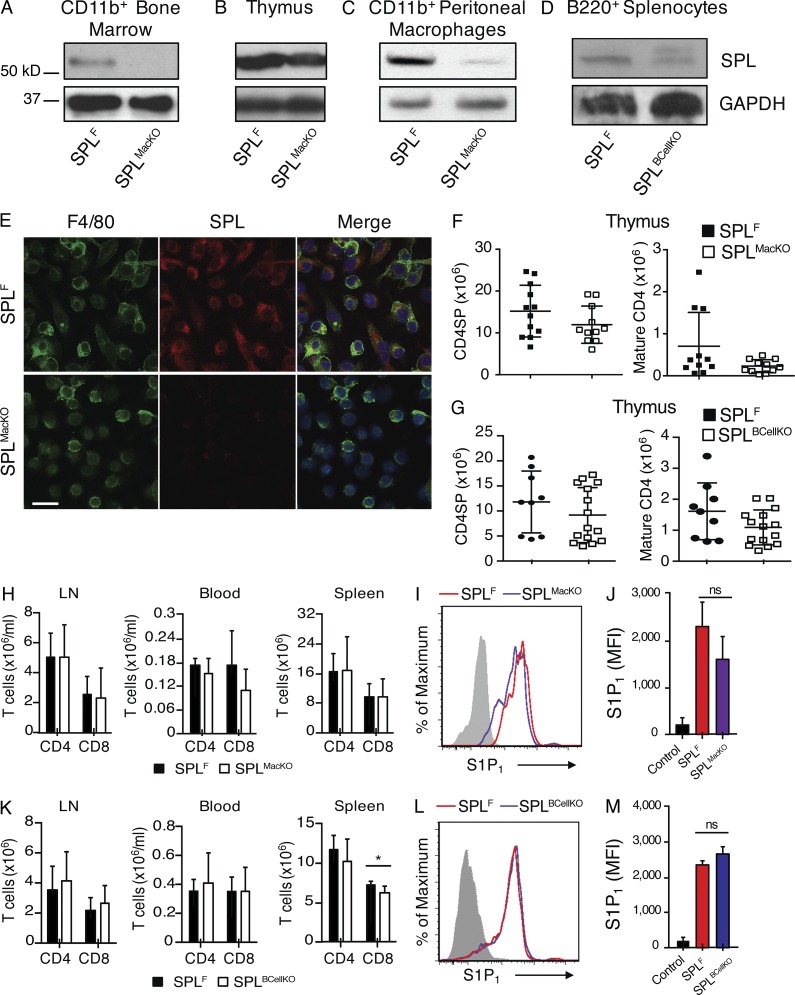

We therefore investigated the impact of disrupting SPL function in the other major hematopoietic-derived cell types found in the thymus. We generated Sgpl1fl/flCD11b-Cre (SPLMacKO) mice, which lack the expression of SPL in monocytes/macrophages, and Sgpl1fl/flCD19-Cre (SPLBCellKO) mice, which lack SPL in B lymphocytes. Efficient recombination and loss of SPL expression in the target cell population of each model was confirmed by immunoblotting of whole cell extracts from purified cells (Fig. 8, A–D). Immunofluorescence microscopy of BM-derived macrophages from SPLMacKO mice showed they exhibit no detectible SPL expression (Fig. 8 E). These mouse models exhibit normal total thymic S1P levels, and their mature T cells express amounts of surface S1P1 similar to those of SPLF, suggesting normal local extracellular S1P levels. Furthermore, the numbers of SP and mature T cells as well as peripheral T cells were similar to those of SPLF (Fig. 3, A and B; and Fig. 8, F–M). These findings establish that neither monocyte/macrophage nor B lymphocyte SPL activities play a significant role in thymic egress.

Figure 8.

SPL deficiency in monocytes/macrophages and B lymphocytes do not influence thymic egress. (A) Western blot to detect SPL in whole-cell extracts of CD11b+ BM cells from SPLF and SPLMacKO mice. CD11b+ cells were isolated by magnetic cell isolation from BM cells of SPLF and SPLMacKO mice and prepared for Western blotting. (B) Western blot to detect SPL in thymic extracts from SPLF and SPLMacKO mice. (C) Western blot to detect SPL in CD11b+ peritoneal macrophage extracts from SPLF and SPLMacKO mice. Peritoneal macrophages were collected as described in Materials and methods, and CD11b+ peritoneal macrophages were isolated by magnetic cell isolation. (D) Western blot to detect SPL in whole-cell extracts of sorted B220+ B cells of SPLF and SPLBcellKO mice. (A–D) GAPDH antibody was used as a loading control. (E) Immunofluorescence was performed using F4/80, SPL antibody, and DAPI (blue) on BM cells that were previously differentiated into macrophages using the growth factor G-CSF. The bottom (SPLMacKO) shows low SPL expression. Bar, 30 µm. The results shown are representative of two independent experiments. (F) Absolute numbers of CD4SP and mature CD4SP T cells from SPLF and SPLMacKO mice (SPLF, n = 12; SPLMacKO, n = 11). (G) Absolute numbers of CD4SP and mature CD4SP T cells from SPLF and SPLBCellKO mice (SPLF, n = 8; SPLBCellKO, n = 15). (H) Absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen, blood, and mesenteric LN of SPLF and SPLMacKO mice as indicated (SPLF, n = 8; SPLMacKO, n = 12). (I) S1P1 surface abundance on mature CD4SP T cells in representative SPLF and SPLMacKO mice. The gray histogram shows staining with negative isotype control. (J) Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of S1P1 (SPLF, n = 3; SPLMacKO, n = 3). The results shown are representative of two experiments. (K) Absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen, blood, and mesenteric LN of SPLF and SPLBCellKO mice as indicated (SPLF, n = 8; SPLBCellKO, n = 15). (L) S1P1 surface abundance on mature CD4SP T cells in representative SPLF and SPLBCellKO mice. The gray histogram shows a negative isotype control. (M) Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity of S1P1 (SPLF, n = 3; SPLBCellKO, n = 3). The results shown are representative of two experiments. (F–H and K) Graphs represent a compilation of three independent experiments. (F–H, J, K, and M) Mean values ± SD are shown. *, P < 0.05 for two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests between the indicated groups.

DCs harbor the metabolic activity essential for maintaining the S1P gradient and promoting thymic egress

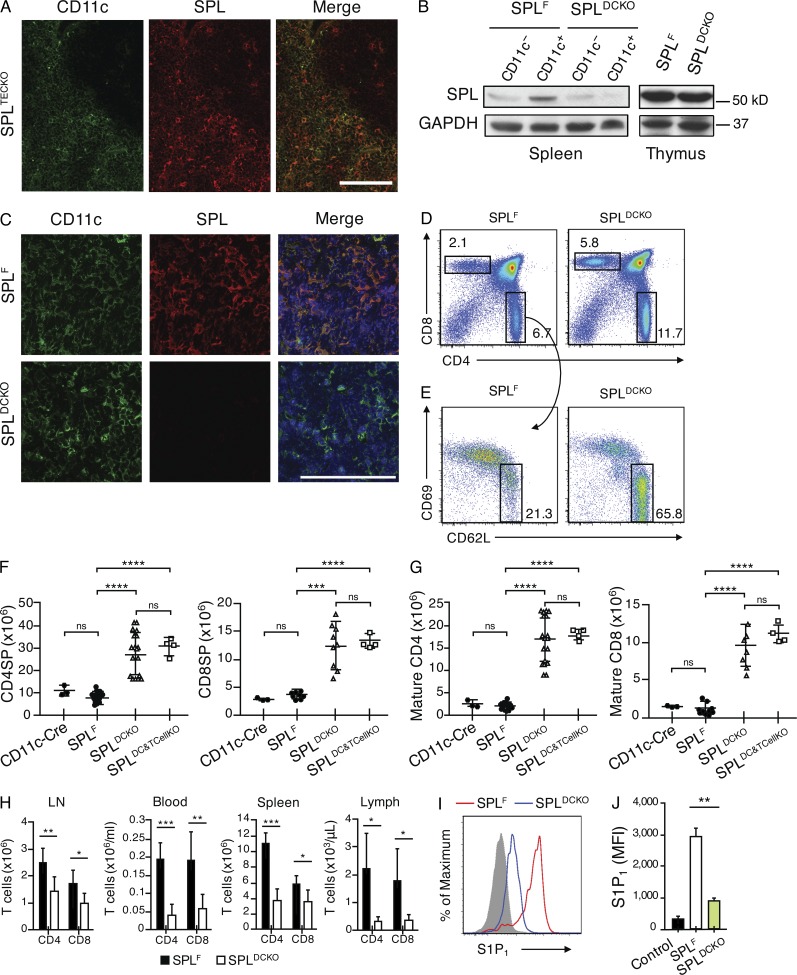

Thymic DCs localize to the medulla and corticomedullary junction (Wu and Shortman, 2005) where mature T cells egress the thymic parenchyma and enter the circulation via blood vessels (Zachariah and Cyster, 2010). To determine whether DC-specific SPL activity might be responsible for the profound egress phenotype observed in SPLMx1KO mice, we first investigated whether DCs express SPL. Because robust SPL expression in TECs obscures detection of SPL in other cell types, SPL expression was analyzed in thymic sections from SPLTECKO mice. DCs located in the medulla and at the corticomedullary junction were found to express SPL (Fig. 9 A).

Figure 9.

SPL expression in thymic DCs is required for thymic egress. (A) Immunofluorescence was performed on frozen thymic sections from SPLTECKO mice using CD11c and SPL antibody. Bar, 100 µm. The results shown are representative of three thymuses analyzed. (B) Western blot to detect SPL in whole-cell extracts of CD11c+ DCs isolated from spleens and whole thymic extracts of SPLF and SPLDCKO mice. GAPDH antibody was used as a loading control. (C) Immunofluorescence was performed on frozen thymic sections from SPLF and SPLDCKO mice using CD11c, SPL antibody, and DAPI (blue) to stain the nuclei. Bar, 100 µm. The results shown are representative of three thymuses analyzed. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of total thymocytes in representative SPLF and SPLDCKO mice. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of CD4SP thymocytes. Mature CD4SP cells were gated as CD62LHiCD69Lo in representative SPLF and SPLDCKO. (D and E) Numbers indicate percentage of cells in the indicated gate. (F) Absolute numbers of CD4SP and CD8SP SPLF and SPLDCKO mice corresponding to the dot plot shown in D, summarized in graph format (CD4SP: SPLF, n = 15; SPLDCKO, n = 18. CD8SP: n = 8/group). (G) Absolute numbers of mature CD4SP and mature CD8SP T cells from SPLF and SPLDCKO mice corresponding to the dot plot shown in E, summarized in bar graph format (Mature CD4: SPLF, n = 15; SPLDCKO, n = 18. Mature CD8: n = 8/group). (H) Absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen, blood, mesenteric LN, and lymph fluid (lymph) of SPLF and SPLDCKO as indicated (SPLF, n = 7; SPLDCKO, n = 15). (F–H) Graphs represent a compilation of five independent experiments. (I) S1P1 surface abundance on mature CD4SP T cells in representative SPLF and SPLDCKO mice. The gray histogram shows a negative isotype control. (J) Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of S1P1 (SPLF, n = 4; SPLDCKO, n = 4). The results shown are representative of two experiments. (F–H and J) Mean values ± SD are shown. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001 for two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests between SPLF and SPLDCKO.

We then generated Sgpl1fl/flCD11c-Cre (SPLDCKO) mice (Stranges et al., 2007), which lack SPL expression in DCs. Western blot analysis of CD11c+ DCs isolated from the spleens of SPLDCKO mice showed reduced SPL expression compared with SPLF DCs, confirming a DC-specific defect in SPL expression in these mice (Fig. 9 B). Whole thymus lysates of SPLDCKO and control mice express similar amounts of SPL, consistent with the observation that TECs harbor the majority of thymic SPL (Fig. 9 B). However, detection of SPL and CD11c in frozen thymic sections by immunofluorescence microscopy showed that thymic DCs in SPLDCKO mice indeed lack SPL expression (Fig. 9 C).

Importantly, SPLDCKO mice exhibited a threefold increase in thymic accumulation of SP cells and a ninefold increase in mature T cells retained in the thymus compared with SPLF controls (Fig. 9, D–G). A second control group that expresses the CD11c-Cre transgene in a nonfloxed background (CD11c-Cre) was indistinguishable from SPLF in egress phenotype, verifying that the phenotype observed in SPLDCKO was not associated with the CD11c-Cre transgene itself (Fig. 9, D–G). The number of T cells in the periphery was also significantly reduced in SPLDCKO mice (Fig. 9 H). S1P levels were 12-fold higher in thymuses, and there was no significant change in the plasma of SPLDCKO mice compared with controls, similar to the relative increase in total thymic S1P levels observed in SPLMx1KO and SPLTCellKO mice (Fig. 3, A and B). In addition, the surface S1P1 expression in mature CD4SP T cells from SPLDCKO mice was reduced by two thirds compared with SPLF, similar to the changes observed in SPLMx1KO mice and more than were observed in SPLTCellKO mice (Fig. 9, I and J). These findings indicate that DCs have a profound impact on extracellular S1P levels in the vicinity of mature T cells.

We next tested whether disruption of SPL in mature T cells’ thymic egress would enhance the egress phenotype of SPLDCKO mice. To this end, we generated a double KO mouse model (SPLDC&TCellKO). The double KO mice exhibited the same phenotype as SPLDCKO (Fig. 9, F and G). This finding demonstrates that SPL in T cells does not provide an additive contribution to DC regulation of thymic egress and that DCs are the main regulators of mature T cell egress. Our observations demonstrate that DCs play a previously unrecognized essential role in thymic egress, providing the metabolic function necessary to generate a highly localized S1P chemotactic gradient that promotes mature T cell egress.

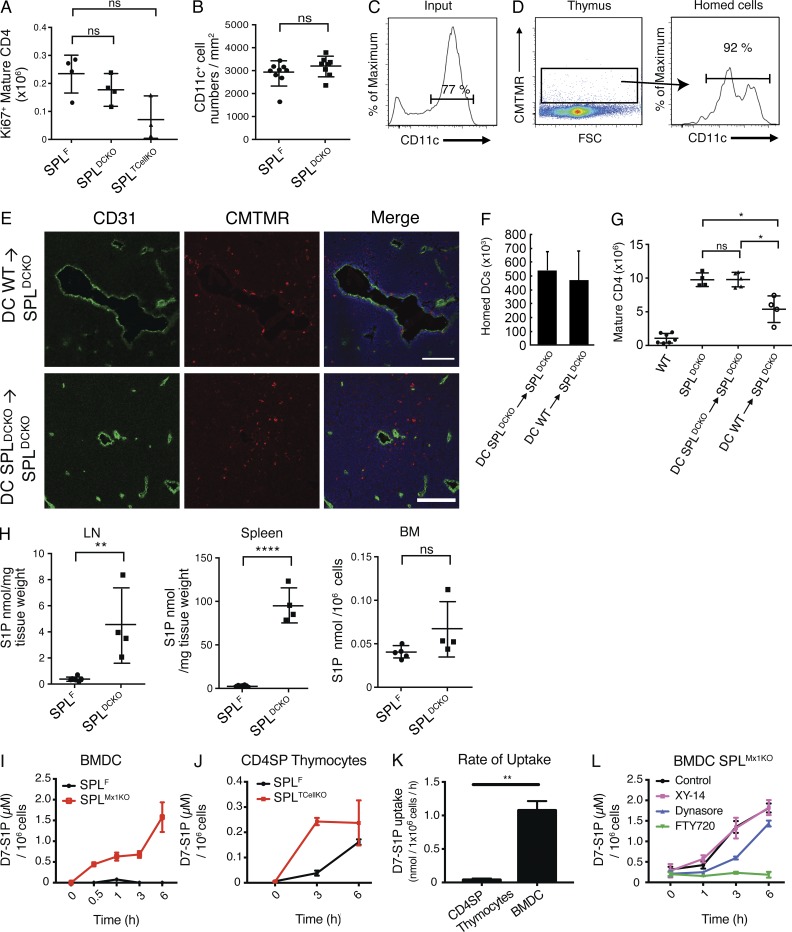

Adoptive transplant of WT peripheral DCs rescues the SPLDCKO egress phenotype

The high number of mature T cells in SPLTCellKO and SPLDCKO could have been a result of increase proliferation. To exclude this possibility, we measured the expression of Ki67, a protein only expressed in proliferating cells. The expression of Ki67 in SPLDCKO and SPLTCellKO was not significantly different from that of SPLF, suggesting that the high number of mature T cells in both models was not caused by an increase of proliferation (Fig. 10 A). SPL disruption in DCs could potentially influence thymic DC quantity. However, we observed no difference in the numbers of medullary DCs in SPLDCKO and SPLF mice (Fig. 10 B). To further confirm the critical role of DC SPL in regulating thymic egress, we took advantage of the fact that circulating DCs can migrate from the periphery to the thymus (Bonasio et al., 2006; Li et al., 2009). To test whether circulating DCs with functional SPL could rescue the block in the mature T cell egress seen in SPLDCKO mice, we performed adoptive transfer experiments in which enriched DC populations obtained from the spleens of WT and SPLDCKO donor mice were administered intravenously to SPLDCKO mice. To confirm the homing of DCs to the thymus, thymic sections of mice injected intravenously with DCs stained with CMTMR cell tracker dye were analyzed by immunofluorescence and flow cytometry. CMTMR+ cells were observed around the blood vessels, and no difference in homing efficiency was observed between WT and SPL-deficient DCs (Fig. 10, C–F). Furthermore, this population of CMTMR+ cells in the thymus was enriched for CD11c+ cells (Fig. 10 D). We showed that infusion of 60–80 × 106 DCs isolated from WT donor mice into SPLDCKO mice resulted in a significant reduction of mature SP T cells in the thymuses of the recipient mice, demonstrating rescue of the thymic egress retention phenotype characteristic of SPLDCKO mice (Fig. 10 G). In contrast, SPLDCKO mice that received infusion of DCs isolated from SPLDCKO donor mice exhibited persistent retention of mature SP T cells.

Figure 10.

WT DCs rescue the SPLDCKO thymic egress phenotype by uptake of S1P in a S1P1,3–5 receptor–dependent manner. (A) Absolute numbers of Ki67+ mature CD4SP T cells in SPLF, SPLDCKO, and SPLTcellKO mice. The results shown are representative of two independent experiments. (B) Number of medullary DCs per unit area. The graph is created from three thymuses per group. DCs were isolated from the spleens of either WT (DC WT) or SPLDCKO (DC SPLDCKO) donor mice as described in Materials and methods. Isolated DCs were administered intravenously into unirradiated SPLDCKO mice. (C) Flow cytometry of CD11c expression of the injected DCs (input). (D) 5 d later, thymuses were collected, and single-cell suspensions were analyzed. (Left) Thymocyte suspension showing homed CMTMR+ cells. FSC, forward side scatter. (Right) CD11c expression on gated CMTMR+ cells. (C and D) Numbers above the bracketed lines indicate the frequency of CD11c+ events. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (E) Immunofluorescence was performed on frozen thymic sections from SPLDCKO mice 24 h after injection using CD31 to stain the blood vessels and Hoechst (blue) to stain the nuclei. Bars, 100 µm. The results shown are representative of five thymuses analyzed. (F) Homing measured by flow cytometry for the presence CMTMR+ cells 5 d after injection. The graph represents a compilation of five thymuses per group. (G) 5 d after injection of DCs, SPLDCKO-recipient mice, as well as WT and SPLDCKO control mice, were euthanized, and mature (CD62LHiCD69Lo) CD4SP T cells were quantified by flow cytometry in whole thymuses. The graph represents a compilation of three independent experiments. (H) S1P levels in LN, spleen, and BM in SPLF and SPLDCKO mice. The graphs represent a compilation of two independent experiments. (I) Mature BMDCs from SPLF and SPLMx1KO were incubated with 1.5 µM D7-S1P, and their uptake was measure by LC/MS over time. The results shown are representative of two independent experiments. (J) CD4SP thymocytes isolated from SPLF and SPLTCellKO mice were incubated with D7-S1P, and their uptake was measured by LC/MS. The results shown are representative of two independent experiments. (K) Rate of D7-S1P uptake was calculated in SPL-deficient CD4SP thymocytes and mature BMDCs. The rate of change was calculated from two independent experiments. (L) Mature BMDCs were incubated for 24 h with either 10 µM XY-14, 5 µM FTY720, 80 µM of dynasore, or DMSO vehicle control before introducing 1.5 µM D7-S1P in the medium. Intracellular D7-S1P was quantified by LC/MS. The results shown are representative of two independent experiments. (A, B, and F–L) Mean values ± SD are shown. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001 for two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests between the indicated groups.

Combined with our other findings, these results establish that DCs play a critical metabolic role in regulating mature T cell egress from the thymus. Specifically, by providing the SPL enzyme activity that degrades extracellular S1P in the vicinity of maturing thymocytes located at the corticomedullary junction, thymic DCs generate a highly localized S1P gradient that is essential for T cells egress. S1P levels were also high in LN and spleen of SPLDCKO mice, demonstrating that DCs regulate S1P levels in other organs as well (Fig. 10 H).

DCs import extracellular S1P through S1P1,3–5 receptors

Our findings indicate that DCs are the primary cells responsible for generating the S1P gradient in the thymus by metabolizing S1P through the actions of intracellular SPL. However, SPL is an intracellular enzyme. Thus, it was important to establish whether DCs are capable of importing S1P from the extracellular environment. Because T cell SPL had some effect on thymic egress and localized S1P levels, we also investigated the ability of SP thymocytes to take up S1P. To this end, we first generated mature BMDCs in vitro and followed their ability to take up D7-S1P, a stable isotope introduced into the medium. Mature BMDCs from SPLF mice degraded D7-S1P rapidly and did not accumulate S1P, whereas those from SPLMx1KO mice accumulated D7-S1P over time (Fig. 10 I). Similarly, CD4SP thymocytes were able to take up D7-S1P (Fig. 10 J). Notably, DCs were able to take up D7-S1P at a significantly faster rate than CD4SP thymocytes (Fig. 10 K).

We hypothesized that mature DCs could import S1P and deliver it to SPL in conjunction with S1P receptor internalization by endocytosis, as has been previously reported (Gatfield et al., 2014). Alternatively, uptake could be mediated by a process of endocytosis independent of S1P receptors and/or via dephosphorylation by lipid phosphatase ectoenzymes (LPPs), the latter being a common mechanism for internalization of phosphorylated molecules and shown to occur with S1P uptake by cells (Zhao et al., 2007). To inhibit endocytosis, S1P1,3–5 receptors, LPPs, and BMDCs were preincubated with either dynasore, FTY720, or XY-14, respectively, for 24 h before introducing D7-S1P in the media. Mature BMDCs derived from SPLMx1KO mice in which S1P1,3–5 receptor activity was blocked with FTY720 entirely lost their ability to take up D7-S1P, whereas inhibition of endocytosis and lipid phosphatase activities only resulted in a reduced rate of uptake (Fig. 10 L). These data demonstrate that S1P1,3–5 receptors are essential for DC uptake of extracellular S1P.

Discussion

In this study, we have disrupted SPL expression in a series of thymic cell populations to clarify the role of S1P metabolism in thymic egress. Our findings revealed a novel and essential metabolic function of DCs in promoting the egress of mature T cells from the thymus. DCs perform this function by generating the S1P gradient through import and irreversible SPL-catalyzed degradation of a signaling pool of extracellular S1P. Considering the location of DCs in the thymic medulla and at the corticomedullary junction, it is likely that thymic DCs produce a localized chemical gradient that stimulates the chemotaxis of mature T cells from the thymic parenchyma, where S1P levels are actively kept low toward nearby perivascular cells and the intravascular space, where S1P levels are high.

Our conclusion is based on several findings. First, we observed a severe block in thymic egress in mice lacking SPL in a restricted fashion within cells expressing the DC marker CD11c. In the model we have used, the Cre transgene is expressed under the control of a 160-kb genomic fragment of Itgax and results in recombination of the floxed allele in a highly restricted fashion in classical and plasmacytoid DCs (Caton et al., 2007). In combination with the lack of phenotypes observed in other thymic stromal cell–specific SPL KO strains, our findings support a direct role for DCs in thymic lymphocyte egress. Second, SPL in thymic DCs is responsible for maintaining a localized S1P gradient within the immediate vicinity of mature T cells. SPL deletion in DCs caused a significant increase in the overall thymic S1P concentration (determined by S1P quantitation) and also in the immediate vicinity of mature T cells (determined by S1P1 expression). Third, we have shown that peripheral DCs isolated from WT mice can rescue the defect in mature T cell egress of SPLDCKO mice. We used immature DCs in these studies, as they were reported to have the highest ability to home to the thymus (Bonasio et al., 2006). Only WT mouse DCs and not SPLDCKO mouse DCs could correct the defect in mature T cell egress in SPLDCKO mice. This finding demonstrates the critical role played by SPL in DC-mediated rescue and, consequently, in mediating thymic egress. Lastly, disruption of T cell SPL did not provide any additive effect on thymocyte retention to SPLDCKO mice in a double KO model, confirming the major role of DC SPL in controlling thymic egress.

DCs comprise only 0.5% of thymic cells (Wu and Shortman, 2005). Despite their paucity, SPL-containing thymic DCs are strategically located for degrading S1P in the interstitial space navigated by mature T cells as they move toward the blood vessels in response to S1P generated by neuronal crest–derived pericytes (Zachariah and Cyster, 2010). Our in vitro experiments establish that extracellular S1P is efficiently imported by DCs through S1P1,3–5 receptors. Once inside the cell, S1P can be readily transported to the ER for irreversible degradation by SPL (Siow et al., 2010). This was illustrated by the rapid degradation of S1P by WT DCs, whereas SPL-deficient DCs accumulated intracellular S1P.

Despite having robust SPL expression, TECs do not contribute to maintaining low thymic S1P concentration and do not contribute to mature T cells’ egress. This pool of SPLs could be involved in thymocyte selection, T cell repertoire, or epithelial cell differentiation, survival, or other functions. Further investigation will be required to test these possibilities.

Several proteins involved in S1P synthesis (SphKs), catabolism (SPL and LPP3), and transport (Spns2) have been identified as regulatory factors necessary for maintaining a S1P gradient between the thymus and the circulation (Schwab et al., 2005; Vogel et al., 2009; Zachariah and Cyster, 2010; Fukuhara et al., 2012). SPL plays an essential role in maintaining low thymic S1P levels (Schwab et al., 2005; Vogel et al., 2009). However, it remains unclear how S1P-related proteins work together to promote egress. Our experiments show that phosphatases are not essential for S1P uptake by DCs. According to Bréart et al. (2011), dephosphorylation of extracellular S1P at the plasma membrane is required for its import. This may be necessary to control S1P import in other cell types but appears to have at most a minor role in DCs.

We observed that disruption of SPL in thymocytes does contribute to efficient thymic egress and localized S1P levels that influence mature T cells’ S1P1 expression. As thymocytes develop from DP to mature T cells, their SPL expression increases significantly (unpublished data). It has been proposed that SPL is needed for S1P1 recycling to the cell surface, which could potentially explain our findings of reduced surface S1P1 on mature T cells from SPLTCellKO mice (Gatfield et al., 2014). Alternatively, mature T cells may require SPL to eliminate S1P export and autocrine stimulation through inside-out signaling to promote efficient chemotaxis toward the point of thymic egress (Takabe et al., 2008). SP thymocytes were also able to take up D7-S1P in vitro. However, their rate of S1P uptake was significantly lower than that of DCs. Whether chemical cues, cell–cell interactions, or other factors in the thymic microenvironment are required for S1P uptake and/or SPL activation in thymocytes remains unknown.

The similar expression of Ki67 in mature T cells of SPLDCKO and SPLTCellKO mice to those of floxed controls demonstrates that the high numbers of mature T cells in their thymuses are not caused by increased proliferation rates but can be attributed directly to an egress defect. Others have reported that thymocyte development is halted in global SPL KO mice because of lack of immigration and settlement of early thymic progenitors (Weber et al., 2009). However, the absolute numbers of DP and double-negative thymocytes in SPLDCKO mice were similar to floxed controls, and in SPLTCellKO mice, only double-negative thymocytes were significantly elevated (unpublished data). These data demonstrate that, unlike in global SPL KO mice, settling and immigration of early thymic progenitors in SPLDCKO mice is not affected.

DCs are efficient antigen-presenting cells and play a crucial role in central tolerance through diverse mechanisms (Guerder et al., 2012; Weist et al., 2015). Our findings reveal a novel and fundamental role for DCs in the regulation of mature T cell egress, independent of their well-characterized functions in antigen presentation. There is precedent for such a role, as DCs were shown to contribute to vitamin A– and vitamin D–mediated imprinting required to program lymphocyte homing to the small intestines and to promote T cell migration into the epidermis by processing vitamins to their active forms (Sigmundsdottir and Butcher, 2008). However, our study reveals for the first time an essential role for DCs in the direct control of mature T cell egress from the thymus. Peripheral DCs appear to control S1P in LNs and spleen, as high levels of S1P were observed in SPLDCKO mice. Considering the ability of peripheral DCs to recirculate to the thymus, DCs are in a unique position to provide homeostatic regulation of global thymic output in response to events in the periphery. Thymic output is an actively regulated process and can be influenced by systemic or thymic infection, antigenic challenge, aging, and prematurity, and a variety of cytokines (Uldrich et al., 2006; Nunes-Alves et al., 2013). DCs are mediators of the crosstalk between the periphery and the thymus. Their ability to modulate thymic egress in response to information in the periphery by regulating the metabolism of extracellular S1P and controlling S1P levels in secondary lymphoid organs is highly intriguing. This could provide important avenues for modulating thymic egress for therapeutic benefit.

Although in this study we have focused on the role of SPL in T cell trafficking, other immune cells also depend on S1P gradients (Cinamon et al., 2004). In a preliminary analysis, we observed an accumulation of B cells in the LNs of SPLTCellKO, SPLBCellKO, and SPLDCKO mice, but only SPLDCKO showed accumulation of B cells in the spleen (unpublished data). These data further support the critical role of DCs in regulating lymphocyte trafficking through S1P metabolism.

In summary, our study has unveiled a novel metabolic role of thymic DCs in adaptive immunity, namely the generation of a localized S1P gradient essential for mature T cell egress. Thus, in addition to the well established role of DCs in antigen presentation and the development of central tolerance, DCs also are metabolic gatekeepers of lymphocyte trafficking. DCs are thus poised to exert control over thymic output in response to environmental conditions. We have also shown that intrinsic SPL expression in mature T cells facilitates their egress but does not provide additive effects to the major role of DC SPL in controlling thymic egress. Our findings provide a deeper understanding of the regulation of lymphocyte egress and the role of S1P metabolism in adaptive immunity. These findings are relevant to understanding changes in adaptive immunity and may reveal novel therapeutic strategies in a variety of clinical contexts including prematurity, childhood infections and immunizations, chronic infections, cancer, and thymic reconstitution after BM transplantation.

Materials and methods

Animals

Sgpl1fl/fl mice were generated in our laboratory and were backcrossed into the C57BL/6 background for at least six generations as previously described (Degagné et al., 2014). All other mouse lines are in C57BL/6 background and backcrossed for at least six generations. C57BL/6 WT (CD45.2) and congenic CD45.1 (B6.SJL-Ptprca/BoyAiTac) and CD4-Cre B6.Cg-Tg(CD4-cre)1Cwi N9 (Lee et al., 2001) mice were purchased from Taconic. FoxN1-Cre mice (Gordon et al., 2007) were provided by N. Manley (University of Georgia, Athens, GA). Mx1-Cre (C.Cg-Tg[Mx1-cre]1Cgn/J; Kühn et al., 1995), CD11c-Cre (B6.Cg-Tg[Itgax-cre]1-1Reiz/J; Caton et al., 2007), and CD19-Cre (C.Cg-Cd19tm1[cre]Cgn Ighb/J; Rickert et al., 1997) mice were from The Jackson Laboratory. CD11b-Cre mice were provided by J. Vacher (Institut de recherches cliniques de Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada; Ferron and Vacher, 2005). Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 mice were provided by R.H. Adams (Max Planck Institute for Molecular Biomedicine, Münster, Germany; Wang et al., 2010). CD4-Cre (Tg[Cd4-cre]1Cwi/BfluJ) and CD11c-Cre (B6.Cg-Tg[Itgax-cre]1-1Reiz/J) control mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. T cell and DC double KO mice were generated through breeding and verified by using specific primers for CD4-Cre (forward, 5′-TCTCTGTGGCTGGCAGTTTCTCCA-3′; and reverse 5′-TCAAGGCCAGACTAGGCTGCCTAT-3′) and CD11c-Cre (forward, 5′-ACTTGGCAGCTGTCTCCAAG-3′; and reverse, 5′-GCGAACATCTTCAGGTTCTG-3′) in a Sgpl1fl/fl background. Mice were housed in an AAALAC-accredited animal facility at the University of California, San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland. All animal experiment protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for use of live animals. For all different KO characterization and BM transplantation studies, mice were used between 6–8 wk of age or, for rescue studies, recipient mice were 13 wk old and donors were between 6 and 15 wk old. To study mice of the same age, in each experiment, SPLF (Cre−/SPL floxed) and KO (Cre+/SPL floxed) mice from the same litter were compared. Variation of absolute number of cells between experiments is accredited to the range of ages at which different litters were examined.

To induce recombination by Mx1-Cre, 1-wk-old mice received three doses of 25 mg/kg body weight low molecular weight poly(I:C) (InvivoGen) every 48 h through intraperitoneal route. To induce Cre activity in Sgpl1fl/flCdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 and gene deletion, mice were injected with 500 µg tamoxifen (T5648; Sigma-Aldrich) by intraperitoneal route every day from P10 to P15.

Antibodies

SPL-specific antibody has been described previously (Borowsky et al., 2012; Newbigging et al., 2013). Actin antibody and Hoechst stain solution were procured from Sigma-Aldrich. Fluorochrome- or biotin-conjugated monoclonal antibodies, CD4-efluor 450 (clone RM4-5), CD4-FITC (clone RM4-4), CD8-FITC (clone 53-6.7), CD8-PE (clone 53-6.7), CD62L-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone MEL-14), CD69-PE-Cy7 (clone H1.2F3), B220-APC (clone RA3-6B2), CD45.1-PE (clone A20), CD45.2-APC (clone 104), CD45RB-APC (clone C363.16A), and CD11c-biotin (clone N4118) were from eBioscience. Antibodies against CK8 (clone TROMA-1-C) and CD31 (clone 2H8-C) were from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank. F4/80 antibody (clone A3-1) and CD45-FITC (clone YW62.3) were from AbD Serotec. Ki67 antibody was from Vector Laboratories.

Cell dissociation and immunoblotting

Frozen tissues (thymus, spleen, vascular aorta, liver, and BM), cells isolated by mechanical dissociation by gently disrupting soft tissues with a homogenizer, or bead-isolated cells were homogenized in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 137 mM NaCl, and 1% Triton X-100. Lysis buffer was supplemented with protease inhibitors (PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail; Roche), 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 10 mM sodium fluoride. Proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred by electroblotting to nitrocellulose membranes. Immunoblotting was performed using SDS-PAGE Western blotting. Immunoreactive bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo Fisher Scientific). To quantify SPL expression in thymic endothelial cells, the relative intensity of bands on Western blot autoradiograms was quantified using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health).

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Thymus, spleen, and mesenteric LNs were harvested and dispersed into single-cell suspensions by forcing the tissue through a 70-µm cell strainer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Blood was collected from either retroorbital route or cardiac puncture. RBCs were lysed by hypotonic shock, and after washing, cells were suspended in FACS buffer (PBS containing 0.1% BSA and 0.01% sodium azide). Lymph was collected from mice as described previously (Matloubian et al., 2004). In brief, 10 ml RPMI medium was injected into the peritoneal cavity, and blood was collected by cardiac puncture. The abdominal cavity was cut open under a stereomicroscope (Wild Heerbrugg), and lymph was collected from cisterna chyli using a glass microcapillary tube (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Lymph volume was noted, and lymphocytes were stained and counted by flow cytometry.

Cells were counted using a Beckman Coulter counter, and 1–2 × 106 cells were stained with the indicated fluorochrome-conjugated antibody for 30 min on ice in the dark. For S1P1 surface detection, whole thymocytes were stained with rat anti-S1P1 mAb or rat IgG2A isotype control (713412; R&D Systems), biotinylated donkey anti–rat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.), and PE-conjugated streptavidin (eBioscience). Samples were acquired using an LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (BD) and FACSDiva software (BD). Data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

For cell sorting and isolation of CD4+ thymocytes, all thymocytes were stained with CD4-FITC. For cell sorting and isolation of B220+ splenocytes, splenocytes were stained with B220-APC. For isolation of CD45RBHighCD4+ T cells, CD4+ cells were negatively enriched from all splenocytes with a CD4 enrichment kit (11415D; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stained with CD45RB-APC and CD4-FITC. For isolation of thymic endothelial cells, stromal cells were digested with collagenases D and A (Roche) and incubated with CD31, CD45-FITC, and CK8 antibodies followed by incubation with specific fluorescent secondary antibodies. All cells were sorted on a FACSAria II cell sorter (BD).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Thymuses were embedded in optimal cutting temperature medium, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C. 5-µm cryosections were cut, air dried, and fixed in chilled acetone. Sections were incubated for 1 h in a humidified chamber with 5% serum from the same species in which secondary antibody has been raised. Then, sections were stained with the indicated primary antibody overnight at 4°C, and after washing, sections were stained with respective secondary antibodies for 1 h. Then, sections were counterstained with 100 ng/ml DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min or Hoechst stain solution (Sigma-Aldrich) and mounted in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). Images were captured using a laser-scanning microscope and software (LSM 710; ZEISS). Images were processed using Photoshop CS6 software (Adobe). The medulla was identified by staining with the lectin UEA-1 (Vector Laboratories). CD11c+ cell numbers were calculated by counting nucleated CD11c+ per unit area.

Plasma and thymus S1P quantification

S1P was extracted from plasma and thymic tissue using a previously described procedure (Bielawski et al., 2006) with the following modifications: 20-µl plasma samples were diluted in 1 ml PBS, and 100 µl of homogenized thymic tissue lysate was used. To these samples, 10 µl of 62.4 µmol/L of internal standard d-erythro–sphingosine-d7-1-phosphate (D7-S1P; Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.) was added. 2 ml of extraction buffer (isopropanol/ethyl-acetate; 15:85, vol/vol) was added, and the sample was vortexed for 30 s. These samples were subjected to centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. The upper organic phase was collected, and the samples were reextracted after the addition of 100 µl of concentrated formic acid. Organic phase extracts were pooled, and 1.5 ml of organic phase was dried under a constant stream of nitrogen gas. Dried samples were reconstituted in 150 µl of mobile phase B (MeOH containing 1 mM ammonium formate and 0.2% formic acid). For thymic samples, 100 mg of frozen samples were weighed and homogenized in 1 ml of homogenizer buffer (50 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.25 M sucrose, 25 mM KCl, and 0.5 mM EDTA) using a glass dounce homogenizer. 100 µL of the homogenate was spiked with 10 µl of 62.4 µmol/L of internal standard d-erythro–sphingosine-d7-1-phosphate (D7-S1P; Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.). To these samples, 2 ml of tissue S1P extraction buffer (isopropanol/water/ethyl acetate; 30:10:60, vol/vol/vol) was added and vortexed. These samples were sonicated in a bath sonicator for 30 s and briefly vortexed; this step was repeated three times. After sonication, samples were subjected to centrifugation for 10 min at 4,000 rpm at room temperature. The organic phase was collected, and the tissue pellet was reextracted. Organic phases from both extractions were pooled, and 1.5 ml of aliquot was dried under a constant stream of nitrogen and reconstituted in 150 µl of mobile phase B.

For analysis of S1P, a 1290 ultra–high-pressure LC system coupled to a mass spectrometer (6490 Triple Quadrupole; Agilent Technologies) equipped with Jet Stream–electrospray ionization interface (Agilent Technologies) was used. The instrument was operated by Mass Hunter Workstation software. Chromatographic separation was performed with a rapid resolution high definition column (2.1 × 150 mm; 1.8 µm; Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18) equilibrated at 50°C. A binary gradient of mobile phase A (water containing 0.2% formic acid and 2 mM ammonium formate) and B (methanol containing 0.2% formic acid and 1 mM ammonium formate) was delivered at a constant flow rate of 1 ml/min. The total run time was 4 min. The initial gradient was 70% B, increased to 100% B at 3 min, returned to baseline at 3.1 min, and maintained until 4 min.

Analysis was performed using multiple-reaction monitoring mode. The general source settings in the positive ionization modes were as follows: gas temperature, 200_C; gas flow, 16 liter, min_1; nebulizer, 20 psi; sheath gas temperature, 250 _C; sheath gas flow, 11 liter, min_1; capillary voltage, 3,000 V; and nozzle voltage, 0 V. The fragmentor voltage of 380 V and a dwell time of 200 ms were used for all mass transitions, and both Q1 and Q3 resolutions were set to nominal mass unit resolution. The multiple reaction monitoring transitions used for S1P and D7-S1P were m/z 380.6→264.2 (collision energy, 12 V) and m/z 387.2→271.3 (collision energy, 12 V), respectively. Peak area ratio between target analyte and its internal standard was used for quantitation.

BM chimeras

For BM chimeras, recipients were irradiated with two 6 Gray doses of x-ray total body irradiation separated by 3 h. The source of ionizing radiation was an x-ray generator (RS-2000 Biological Irradiator; Rad Source Technologies, Inc.) operating at 160 kV and 25 mA, yielding an absorbed dose rate of 2.2 Gy/min. 16 h after irradiation, BM was removed by flushing out femoral bones from donor mice with 5 ml of ice-cold RPMI media under sterile conditions. Cells were disaggregated with a 22-gauge needle and filtered through a sterile 40-µm cell strainer, and cells were resuspended in RPMI medium. Mice received 5–10 × 106 BM cells by retroorbital injection. Chimeras were analyzed 7 wk after transplantation.

DC and macrophage isolation

CD11b+ cells were isolated from BM of SPLF and SPLMacKO mice by a magnetic-activated cell-sorting–based system using CD11b microbeads (130-049-601; Miltenyi Biotec). Resident peritoneal macrophages were isolated as previously described (Ray and Dittel, 2010). CD11b+ peritoneal macrophages were isolated using CD11b microbeads. Splenic CD11c+ DCs were isolated by digesting whole spleens from SPLF and SPLDCKO mice with collagenase D (Roche) and using CD11c microbeads (130-052-001; Miltenyi Biotec). CD4SP thymocytes were isolated from SPLF and SPLTCellKO mice using a CD4+ T Cell Isolation kit (130-104-454; Miltenyi Biotec) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro differentiation of DCs and macrophages

DCs and macrophages were prepared according to a modified protocol described by Lutz et al. (1999). In brief, 2 × 106 BM cells from tibia and femur of SPLF and SPLMx1KO mice were cultured in RPMI 1640, 10% heat-inactivated FBS, β-ME, glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin supplemented with 100–200 ng/ml GM-CSF (Prospec) for DCs or 100–200 ng/ml M-CSF (Prospec) for macrophages for 6 or 7 d. DCs were matured for one additional day with 100 ng/ml LPS (Sigma-Aldrich).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from sorted cell populations using an Aurum total RNA mini kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) that included DNase I treatment. RT reactions were performed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Real-time PCR reactions were performed on a thermocycler (ABI 7900HT; Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The following primer sets were used: SGPL1 forward, 5′-GAACCGACCTCCTCAAGCTG-3′; SGPL1 reverse, 5′-AGGACACTCCACGCAATGAG-3′; GAPDH forward, 5′-AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG-3′; and GAPDH reverse, 5′-ACACATTGGGGGTAGGAACA-3′. To control for DNA contamination, primers were designed to span at least an intron, and a reaction without RT was performed in parallel for each sample/primer pair. Primer pairs were also tested for linear amplification over two orders of magnitude.

Adoptive transfer of peripheral DCs

C57BL/6 and SPLDCKO mice were injected subcutaneously with 4 × 106 to 6 × 106 B16 melanoma cells secreting Flt3 ligand to increase DC population of donor mice, as previously described (Mora et al., 2003). B16 melanoma cells secreting Flt3 ligand were provided by L. Fong (University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA). After 10–14 d, mice were euthanized, and DCs were purified by density gradient centrifugation over Optiprep medium (Sigma-Aldrich) by collection of the low-density fraction (Bonasio et al., 2006). This fraction constituted 70–80% CD11c+ cells. In some experiments, isolated cells were stained with 10 mM CMTMR (5-(and-6)-(((4-chloromethyl)benzoyl)amino)tetramethylrhodamine; Invitrogen). Then 60–80 × 106 isolated immature DCs were injected intravenously into SPLDCKO and SPLF littermate controls. Mice were sacrificed 5 d later. The number of mature CD4SP cells in their thymuses was analyzed using an LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (BD). The total number of homed DCs was calculated by multiplying the fraction of CMTMR+ events by the total cellularity of the thymus.

Measurement of extracellular D7-S1P uptake

Mature BMDCs from SPLF and SPLDCKO mice were incubated in 1.5 µM d-erythro–sphingosine-d7-1-phosphate (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.) for 0.5, 1, 3, and 6 h. Cells were washed three times with PBS, and D7-S1P was quantified in cell pellets by LC/MS. To study the mechanisms of uptake, BMDCs from SPLDCKO mice were matured for 24 h with 100 ng/ml LPS (Sigma-Aldrich). Mature BMDCs were then incubated for 24 h with control DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 µM XY-14 (Echelon), 5 µM FTY720 (Sigma-Aldrich), or 80 µM of dynasore (Sigma-Aldrich) before adding 1.5 µM D7-S1P in RPMI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. After 1-, 3-, and 6-h incubation, the medium was removed, cells were washed three times with PBS, and D7-S1P was quantified by LC/MS. Isolated CD4SP thymocytes from SPLF and SPLTCellKO mice were incubated in 1.5 µM D7-S1P for 0, 3, and 6 h. The medium was removed, cells were washed three times with PBS, and D7-S1P was quantified by LC/MS as described before using C17-S1P as an internal standard.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software), and results are presented as mean ± SD, as indicated. The mean of two groups was compared by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this manuscript to Alexander Lucas, a brilliant immunologist and treasured colleague.

We are grateful to Nancy Manley for FoxN1-Cre mice, Dr. Jean Vacher for CD11b-Cre mice, Dr. Ralf H. Adams for Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 mice, Dr. L. Fong for B16-Flt3L melanoma cells, Teresa Klask for expert administrative support, and members of the Saba laboratory for discussion and support. We also thank Dr. Joanna Halkias and Dr. Heather Melichar for their critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (CA129438) and Swim Across America funds (to J.D. Saba). Confocal images were acquired at the Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute Microimaging Facility supported by an NIH grant (S10RR025472) and the Children's Hospital Branches, Inc. S1P measurements were obtained using the Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute Mass Spectrometry Facility supported by an NIH Health grant (S10OD018070).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- CK8

- cytokeratin 8

- DP

- double positive

- LC

- liquid chromatography

- LPP

- lipid phosphatase ectoenzyme

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- poly(I:C)

- polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid

- S1P

- sphingosine-1-phosphate

- SP

- single positive

- SPL

- S1P lyase

- TEC

- thymic epithelial cell

References

- Bagdanoff J.T., Donoviel M.S., Nouraldeen A., Carlsen M., Jessop T.C., Tarver J., Aleem S., Dong L., Zhang H., Boteju L., et al. 2010. Inhibition of sphingosine 1-phosphate lyase for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: discovery of (E)-1-(4-((1R,2S,3R)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroxybutyl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl)ethanone oxime (LX2931) and (1R,2S,3R)-1-(2-(isoxazol-3-yl)-1H-imidazol-4-yl)butane-1,2,3,4-tetraol (LX2932). J. Med. Chem. 53:8650–8662. 10.1021/jm101183p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzins S.P., Godfrey D.I., Miller J.F., and Boyd R.L.. 1999. A central role for thymic emigrants in peripheral T cell homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:9787–9791. 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielawski J., Szulc Z.M., Hannun Y.A., and Bielawska A.. 2006. Simultaneous quantitative analysis of bioactive sphingolipids by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Methods. 39:82–91. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonasio R., Scimone M.L., Schaerli P., Grabie N., Lichtman A.H., and von Andrian U.H.. 2006. Clonal deletion of thymocytes by circulating dendritic cells homing to the thymus. Nat. Immunol. 7:1092–1100. 10.1038/ni1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky A.D., Bandhuvula P., Kumar A., Yoshinaga Y., Nefedov M., Fong L.G., Zhang M., Baridon B., Dillard L., de Jong P., et al. 2012. Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase expression in embryonic and adult murine tissues. J. Lipid Res. 53:1920–1931. 10.1194/jlr.M028084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bréart B., Ramos-Perez W.D., Mendoza A., Salous A.K., Gobert M., Huang Y., Adams R.H., Lafaille J.J., Escalante-Alcalde D., Morris A.J., and Schwab S.R.. 2011. Lipid phosphate phosphatase 3 enables efficient thymic egress. J. Exp. Med. 208:1267–1278. 10.1084/jem.20102551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson C.M., Endrizzi B.T., Wu J., Ding X., Weinreich M.A., Walsh E.R., Wani M.A., Lingrel J.B., Hogquist K.A., and Jameson S.C.. 2006. Kruppel-like factor 2 regulates thymocyte and T-cell migration. Nature. 442:299–302. 10.1038/nature04882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caton M.L., Smith-Raska M.R., and Reizis B.. 2007. Notch–RBP-J signaling controls the homeostasis of CD8− dendritic cells in the spleen. J. Exp. Med. 204:1653–1664. 10.1084/jem.20062648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinamon G., Matloubian M., Lesneski M.J., Xu Y., Low C., Lu T., Proia R.L., and Cyster J.G.. 2004. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 promotes B cell localization in the splenic marginal zone. Nat. Immunol. 5:713–720. 10.1038/ni1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degagné E., Pandurangan A., Bandhuvula P., Kumar A., Eltanawy A., Zhang M., Yoshinaga Y., Nefedov M., de Jong P.J., Fong L.G., et al. 2014. Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase downregulation promotes colon carcinogenesis through STAT3-activated microRNAs. J. Clin. Invest. 124:5368–5384. 10.1172/JCI74188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron M., and Vacher J.. 2005. Targeted expression of Cre recombinase in macrophages and osteoclasts in transgenic mice. Genesis. 41:138–145. 10.1002/gene.20108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara S., Simmons S., Kawamura S., Inoue A., Orba Y., Tokudome T., Sunden Y., Arai Y., Moriwaki K., Ishida J., et al. 2012. The sphingosine-1-phosphate transporter Spns2 expressed on endothelial cells regulates lymphocyte trafficking in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 122:1416–1426. 10.1172/JCI60746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatfield J., Monnier L., Studer R., Bolli M.H., Steiner B., and Nayler O.. 2014. Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) displays sustained S1P1 receptor agonism and signaling through S1P lyase-dependent receptor recycling. Cell. Signal. 26:1576–1588. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J., Xiao S., Hughes B. III, Su D.M., Navarre S.P., Condie B.G., and Manley N.R.. 2007. Specific expression of lacZ and cre recombinase in fetal thymic epithelial cells by multiplex gene targeting at the Foxn1 locus. BMC Dev. Biol. 7:69 10.1186/1471-213X-7-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gräler M.H., Huang M.C., Watson S., and Goetzl E.J.. 2005. Immunological effects of transgenic constitutive expression of the type 1 sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor by mouse lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 174:1997–2003. 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerder S., Viret C., Luche H., Ardouin L., and Malissen B.. 2012. Differential processing of self-antigens by subsets of thymic stromal cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 24:99–104. 10.1016/j.coi.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert F.X., Kinkel S.A., Davey G.M., Phipson B., Mueller S.N., Liston A., Proietto A.I., Cannon P.Z., Forehan S., Smyth G.K., et al. 2011. Aire regulates the transfer of antigen from mTECs to dendritic cells for induction of thymic tolerance. Blood. 118:2462–2472. 10.1182/blood-2010-06-286393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappos L., Antel J., Comi G., Montalban X., O’Connor P., Polman C.H., Haas T., Korn A.A., Karlsson G., and Radue E.W.. FTY720 D2201 Study Group . 2006. Oral fingolimod (FTY720) for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 355:1124–1140. 10.1056/NEJMoa052643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn R., Schwenk F., Aguet M., and Rajewsky K.. 1995. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science. 269:1427–1429. 10.1126/science.7660125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G.R., Fields P.E., and Flavell R.A.. 2001. Regulation of IL-4 gene expression by distal regulatory elements and GATA-3 at the chromatin level. Immunity. 14:447–459. 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00125-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y., Ripen A.M., Ishimaru N., Ohigashi I., Nagasawa T., Jeker L.T., Bösl M.R., Holländer G.A., Hayashi Y., Malefyt R.W., et al. 2011. Aire-dependent production of XCL1 mediates medullary accumulation of thymic dendritic cells and contributes to regulatory T cell development. J. Exp. Med. 208:383–394. 10.1084/jem.20102327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Park J., Foss D., and Goldschneider I.. 2009. Thymus-homing peripheral dendritic cells constitute two of the three major subsets of dendritic cells in the steady-state thymus. J. Exp. Med. 206:607–622. 10.1084/jem.20082232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.H., Thangada S., Lee M.J., Van Brocklyn J.R., Spiegel S., and Hla T.. 1999. Ligand-induced trafficking of the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor EDG-1. Mol. Biol. Cell. 10:1179–1190. 10.1091/mbc.10.4.1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz M.B., Kukutsch N., Ogilvie A.L., Rössner S., Koch F., Romani N., and Schuler G.. 1999. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods. 223:77–92. 10.1016/S0022-1759(98)00204-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloubian M., Lo C.G., Cinamon G., Lesneski M.J., Xu Y., Brinkmann V., Allende M.L., Proia R.L., and Cyster J.G.. 2004. Lymphocyte egress from thymus and peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on S1P receptor 1. Nature. 427:355–360. 10.1038/nature02284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora J.R., Bono M.R., Manjunath N., Weninger W., Cavanagh L.L., Rosemblatt M., and Von Andrian U.H.. 2003. Selective imprinting of gut-homing T cells by Peyer’s patch dendritic cells. Nature. 424:88–93. 10.1038/nature01726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbigging S., Zhang M., and Saba J.D.. 2013. Immunohistochemical analysis of sphingosine phosphate lyase expression during murine development. Gene Expr. Patterns. 13:21–29. 10.1016/j.gep.2012.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes-Alves C., Nobrega C., Behar S.M., and Correia-Neves M.. 2013. Tolerance has its limits: how the thymus copes with infection. Trends Immunol. 34:502–510. 10.1016/j.it.2013.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera J., Meng L., Meng F., and Huang H.. 2013. Autoreactive thymic B cells are efficient antigen-presenting cells of cognate self-antigens for T cell negative selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110:17011–17016. 10.1073/pnas.1313001110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]