ABSTRACT

The influenza A virus polymerase plays an essential role in the virus life cycle, directing synthesis of viral mRNAs and genomes. It is a trimeric complex composed of subunits PA, PB1, and PB2 and associates with viral RNAs and nucleoprotein (NP) to form higher-order ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. The polymerase is regulated temporally over the course of infection to ensure coordinated expression of viral genes as well as replication of the viral genome. Various host factors and processes have been implicated in regulation of the IAV polymerase function, including posttranslational modifications; however, the mechanisms are not fully understood. Here we demonstrate that ubiquitination plays an important role in stimulating polymerase activity. We show that all protein subunits in the RNP are ubiquitinated, but ubiquitination does not significantly alter protein levels. Instead, ubiquitination and an active proteasome enhance polymerase activity. Expression of ubiquitin upregulates polymerase function in a dose-dependent fashion, causing increased accumulation of viral RNA (vRNA), cRNA, and mRNA and enhanced viral gene expression during infection. Ubiquitin expression directly affects polymerase activity independent of nucleoprotein (NP) or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) assembly. Ubiquitination and the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway play key roles during multiple stages of influenza virus infection, and data presented here now demonstrate that these processes modulate viral polymerase activity independent of protein degradation.

IMPORTANCE The cellular ubiquitin-proteasome pathway impacts steps during the entire influenza virus life cycle. Ubiquitination suppresses replication by targeting viral proteins for degradation and stimulating innate antiviral signaling pathways. Ubiquitination also enhances replication by facilitating viral entry and virion disassembly. We identify here an addition proviral role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, showing that all of the proteins in the viral replication machinery are subject to ubiquitination and this is crucial for optimal viral polymerase activity. Manipulation of the ubiquitin machinery for therapeutic benefit is therefore likely to disrupt the function of multiple viral proteins at stages throughout the course of infection.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza viruses are a significant threat to human public health and a major cause of morbidity and mortality in both human and animal populations (1). Influenza A virus (IAV) is a member of the Orthomyxoviridae family, composed of eight minus-sense single-stranded RNA (−ssRNA) segments that make up its genome. Each −ssRNA segment associates with a viral polymerase and oligomeric nucleoproteins (NPs) to form large ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes that direct expression of viral genes and replication and packaging of the viral genome (2, 3). The ability of the virus to efficiently express its genes and replicate its genome is key to a successful infection as it enables modulation of the host cell environment by the virus to allow subsequent assembly of progeny virions. Transcription and replication of the genome are performed by the viral polymerase. The polymerase is a trimeric protein complex composed of the polymerase acidic (PA), polymerase basic 1 (PB1), and PB2 proteins. Viral genes are transcribed by a “cap-snatching” process where the polymerase acquires 5′ 7-methylguanosine (7mG) caps from host mRNAs and uses them to initiate synthesis of viral messages. The 7mG cap is bound by the cap-binding domain in the PB2 subunit, and the mRNA is subsequently cleaved 11 to 15 nucleotides (nt) downstream by the endonuclease domain in the PA subunit (4–6). The resulting short capped RNA is used to prime synthesis of viral mRNA by the polymerase catalytic site resident in the PB1 subunit. Transcription continues to the end of the template, where an iterative copy of a poly(U) tract appends a poly(A) tail to complete mRNA synthesis. Genome replication is performed by the polymerase during primer-independent synthesis of full-length plus-sense cRNA, which serves as a template for production of new genomic viral RNA (vRNA).

Influenza polymerase activity is impacted by the host cell environment and temporally regulated during the course of infection (7); i.e., it serves primarily as a transcriptase early in infection then is largely a replicase later in infection (8). Posttranslational modifications (PTMs) of viral proteins by host enzymes have been suggested to impact this change in activity. A number of PTMs have been reported to occur on NP and subunits of the viral polymerase, including phosphorylation of PB1, PB2, PA, and NP (9), sumoylation of PB1 and NP (10, 11), poly-ADP ribosylation of PB2 and PA (12), and ubiquitination of PB1 and NP (13, 14). These modifications can impact multiple steps in the assembly and function of RNPs. Phosphorylation and sumoylation of NP have been reported to impact its localization to the nucleus or export to the cytoplasm, respectively (11, 15, 16). Phosphorylation of NP has also been shown to regulate its homo-oligomerization and assembly of RNP complexes (17–19). Thus, the dynamic and reversible modification of proteins in the RNP is a likely regulator of genome transcription and replication, yet the mechanisms underlying this regulation are not fully understood.

Ubiquitination involves the conjugation of the 8.5-kDa ubiquitin (Ub) protein to specific lysine residues on substrate proteins. This follows a cascade of reactions transferring ubiquitin from the E1 ubiquitin-activating protein to the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating protein, and ultimately the E3 ubiquitin ligase attaches ubiquitin to the substrate (20). Monoubiquitination attaches a single ubiquitin moiety to sites on a substrate protein, whereas polyubiquitination attaches ubiquitin chains. The specific linkage between ubiquitin moieties in a chain determines the impact of polyubiquitination on the target protein. Ubiquitination regulates various cellular processes; however, polyubiquitin chains linked via lysine 48 (K48) within ubiquitin are most commonly associated with protein degradation via the proteasome, while chains linked by lysine 63 (K63) are involved in endocytic trafficking, potentially leading to lysosomal degradation, ribosomal modification, and DNA repair (20). The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway impacts multiple steps in the influenza virus cycle, and inhibition of this pathway is detrimental to the viral life cycle (21). During entry, the E3 ligase Itch is required for efficient release of virions from endosomes and the E3 Nedd4 is important for the turnover of the host protein IFITM3, an antiviral factor that blocks release from the endosome (22, 23). Following entry, free ubiquitin found within virions then targets the incoming viral core to the aggresome machinery to facilitate uncoating (24, 25). Multiple E3 ubiquitin ligases have been identified as key host factors regulating the IAV infectious cycle, and ubiquitination of viral proteins has been shown to regulate their stability and function (12–14, 22, 23, 26, 27). Indeed, ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation of IAV protein has recently been shown to restrict infection (12, 14).

To establish the role of ubiquitination in the regulation of the IAV polymerase function, we investigated whether the RNP is ubiquitinated and how this might impact transcription, genome replication, and viral infection. We show here that all of the protein components in the RNP are ubiquitinated during infection. This ubiquitination did not cause significant protein degradation, but rather resulted in a dramatic stimulation of polymerase activity and enhanced gene expression during infection. Disrupting the ubiquitin pathway by inhibiting the proteasome reduced polymerase activity. Primer extension assays demonstrated that ubiquitination is associated with increases in both transcription and replication by the IAV polymerase, which resulted in enhanced gene expression during infection. Our findings show that the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway plays diverse roles during viral infection, restricting infection in some cases, enhancing entry in others, and as our data show, stimulating gene expression and genome replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, antibodies, and reagents.

HEK293T cells were maintained in complete Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). All cells were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2. The antibodies used include M2 anti-FLAG (Sigma), anti-V5 (Bethyl), anti-RNP (BEI NR-3133), and anti-hemagglutinin (anti-HA [Roche]). MG132 was obtained from EMD Millipore.

Plasmids.

The IAV RNP reconstitution plasmids used throughout encode polymerase proteins and NP derived from A/WSN/1933 (H1N1) (WSN) and were described previously (28). Epitope-tagged PB2-FLAG and NP-V5 were expressed as C-terminal fusions (28). The vNA-Luc reporter plasmids encode a minus-sense luciferase gene flanked by untranslated regions (UTRs) from neuraminidase (NA) that is expressed from a polymerase I promoter and terminator (28). Mutants were created by PCR-based strategies and confirmed by sequencing. The wild-type (WT) Ub and K48R and K63R ubiquitin plasmids used were N-terminally tagged with HA-epitope (29) (a kind gift from D. Gabudza). A plasmid expressing a 77-nt vNP microgene was constructed following previously described microgenes (30). The influenza virus reverse genetics plasmids include pTMΔRNP, which expresses viral RNAs (vRNAs) for HA, NA, M, and NS and pBD-PB1, -PB2, -PB2-FLAG, -PA, and -NP (28).

Viruses.

Viruses stably encoding a C-terminal FLAG tag on PB2 required duplication of a portion of the PB2 open reading frame to maintain a contiguous packaging signal and were engineered following the strategy of Dos Santos Afonso et al. (31). WSN, WSN(PB2-FLAG), or reassortants encoding PB2-FLAG, PB1, PA, and NP derived from A/green-winged teal/OH/175/1983 (S009) or A/New York/312/2001 (NY312) were rescued in transfected HEK293T cells and amplified, and their titers were determined as described previously (32).

Polymerase activity assay.

HEK293T cells were transfected using TransIT-2020 (Mirus Bio) in triplicate with plasmids encoding PA, PB1, PB2-FLAG, NP, the vNA-Luc reporter plasmid, and increasing amounts of plasmid encoding HA-ubiquitin or an empty vector. The total DNA concentration for each transfection was kept constant. Cells were lysed 24 to 48 h posttransfection in cell culture lysis reagent (Promega), and luciferase activity was measured by using the luciferase assay system (Promega). Expression of IAV RNP components and HA-ubiquitin was analyzed by Western blotting.

Immunoprecipitations.

HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing PA, PB1, PB2-FLAG, NP, vNA-luciferase reporter, and HA-ubiquitin and lysed 24 to 48 h posttransfection. Alternatively, HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-ubiquitin plasmid, incubated for 16 to 18 h, and subsequently infected with PB2-FLAG virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1.0 for 16 to 18 h. Cells were lysed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitor cocktail. Clarified lysates were precleared and immunoprecipitated with M2 (anti-FLAG)-agarose beads (Sigma). The beads were washed extensively and then boiled in protein loading buffer, and immunoprecipitated complexes were analyzed by Western blotting.

Immunoprecipitation of denatured lysates.

HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing either PA-FLAG, PB1-FLAG, PB2-FLAG, NP-V5, NP-V5 K184R, or an empty plasmid. After 24 to 48 h posttransfection, the cells were lysed as described by Choo et al. (33). Briefly, cells were lysed in a mixture of 2% SDS, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton, and protease inhibitor cocktails, clarified by centrifugation, and boiled for 10 min to completely denature the same. Lysates were then renatured by dilution with 9 volumes of 10 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton. After renaturing, lysates were immunoprecipitated as described above.

RNA isolation and primer extension.

Total RNA was extracted from transfected 293T cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Seven nanograms from each of the RNA samples was analyzed by primer extension. RNA was mixed with an excess of 32P-labeled DNA primers that specifically recognize plus-sense or minus-sense viral RNAs and 5S host RNA (8). A different set of primers were used for the microgene primer extension analysis based on published work by Turrell et al. (30). Samples were denatured by heating at 95°C for 2 min, snap chilled on ice, and incubated for 2 min at either 50°C for Superscript III reverse transcriptase (RT) (Invitrogen) reactions or 42°C for Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) RT reactions prior to the addition of a transcription mix. The Superscript III RT transcription mix was added to create final conditions of 20 mM Tris (pH 8.4), 50 mM KCl, 0.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mix, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 40 U RNAseOUT, and 200 U Superscript III RT. The MMLV RT transcription was added to created final conditions of 50 mM Tris (pH 8.3), 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dNTP mix, 40 U RNAseOUT, and 1 μl MMLV RT. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h, terminated by the addition of an equal volume of formamide, and denatured by heating at 95°C for 5 min. Transcription products were separated on denaturing polyacrylamide gels, dried, and detected by autoradiography.

Viral gene expression assay.

HEK293T cells were transfected with either empty plasmid or increasing amounts of HA-ubiquitin. The total amount of DNA transfected was kept constant. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were infected at an MOI of 0.1 with PASTN virus (34) for 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, or 8 h. At the end of the infection, viral gene expression was measured using the NanoGlo assay kit (Promega).

Statistics.

Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P values of <0.05 are considered significant and are marked with asterisks on some of the figures.

RESULTS

All proteins in the influenza A virus RNP complex are ubiquitinated.

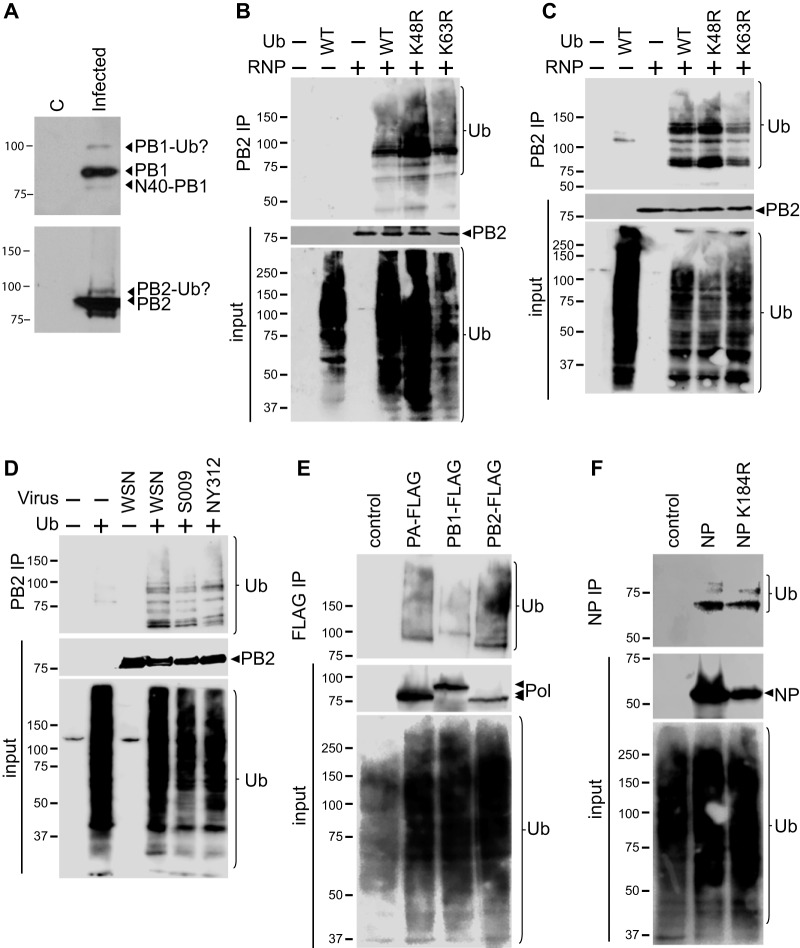

While probing lysates from cells infected with influenza virus, we detected unexpected higher-molecular-mass species of the polymerase subunits PB1 and PB2 (Fig. 1A). The shift in molecular mass was consistent with posttranslational modification by the addition of an 8-kDa ubiquitin moiety. Since the ubiquitin proteasome pathway has been implicated in the regulation of the IAV life cycle, including the viral polymerase function (13, 14, 23, 24), we sought to establish whether these new species were ubiquitinated forms and if the IAV RNP complex undergoes ubiquitination. The IAV RNP was reconstituted in cells expressing a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-based viral reporter gene, NP, and the polymerase subunits PB1, PB2, and PA. To detect ubiquitination, epitope tagged HA-ubiquitin or a control plasmid was included. The RNP was isolated by immunoprecipitation, and ubiquitination was detected by Western blotting. A significant amount of HA-ubiquitinated protein coprecipitated with the IAV RNP, but not in its absence, suggesting that components of the RNP complex are ubiquitinated (Fig. 1B). Moreover, the high-molecular-mass smearing is indicative of polyubiquitination. Since the two major linkages present in polyubiquitin chains occur via conjugation to lysine 48 (K48) or lysine 63 (K63) within Ub (4), we repeated RNP immunoprecipitations from cells expressing wild-type (WT) or mutant forms of ubiquitin that cannot support chain elongation (Fig. 1B). Purified RNPs still displayed high-molecular-mass polyubiquitin smears in the presence of both Ub K48R and Ub K63R. Ubiquitination of the RNP was then tested during viral infections. Cells expressing WT or mutant HA-ubiquitin were infected with the WSN strain encoding a C-terminally FLAG-tagged PB2 (PB2-FLAG). RNPs were immunoprecipitated from infected cells and probed for ubiquitination. Polyubiquitinated proteins were immunoprecipitated from infected cells in the presence of WT or mutant ubiquitin, but not from mock-infected cells (Fig. 1C), validating results obtained from transfected cells. In agreement with data from transfections, ubiquitination during infection was not solely dependent upon K48 or K63 linkages. We also detected ubiquitination of the RNP when cells were infected with virus encoding RNP subunits from primary human (NY312) and avian (S009) isolates (Fig. 1D).

FIG 1.

All subunits of the influenza A RNP are ubiquitinated. (A) Lysates from control (lane C) or infected cells were probed for PB1 and PB2 by Western blotting. In addition to the expected proteins, additional higher-molecular-mass products were specifically detected in infected cells. Molecular masses (in kilodaltons) are indicated. (B) The IAV RNP complex expressing PB2-FLAG was reconstituted in HEK293T cells. Where indicated, cells coexpressed WT or mutant HA-tagged ubiquitin. The RNP complex was immunoprecipitated (IP) using anti-FLAG antibody. Input proteins and coprecipitating HA-ubiquitin were detected by Western blotting. (C) HEK293T cells and those expressing WT or mutant HA-ubiquitin were infected with WSN (PB2-FLAG) at an MOI of 1 for 16 h. Viral RNPs were immunoprecipitated as in panel B, and coprecipitating HA-ubiquitin was analyzed by Western blotting. (D) HEK293T cells and cells expressing HA-ubiquitin were infected with either WSN PB2-FLAG or WSN-based PB2-FLAG reassortants carrying RNP genes from S009 or NY312. Viral RNPs were immunoprecipitated, and coprecipitating HA-ubiquitin was analyzed by Western blotting. (E) PA-FLAG, PB1-FLAG, and PB2-FLAG were individually coexpressed with HA-ubiquitin in HEK293T cells and immunoprecipitated under denaturing conditions, and coprecipitating HA-ubiquitin was detected by Western blotting. (F) WT NP-V5 and the NP-V5 K184R mutant were coexpressed with HA-ubiquitin in HEK293T cells and immunoprecipitated under denaturing conditions, and coprecipitating HA-ubiquitin was detected by Western blotting.

The RNP is composed of four different protein components: PB1, PB2, PA, and NP. Our data show that RNP-associated proteins are ubiquitinated, but it is not clear which subunits are involved. Therefore, to establish which components are ubiquitinated, we individually expressed each protein with WT HA-ubiquitin or a control. We tested whether the RNPs are directly ubiquitinated by eliminating any possible contribution of coprecipitating proteins by performing experiments with denatured lysates. Cells were lysed in denaturing buffer, boiled to disrupt protein complexes, and then immunoprecipitated as previously described (33). Under these stringent conditions, ubiquitinated proteins were still detected in immunoprecipitates of PB1, PB2, and PA (Fig. 1E) and NP (Fig. 1F), providing further evidence that the polymerase proteins and NP are ubiquitinated. A monoubiquitination site had previously been mapped to NP K184 (13). Nonetheless, the NP mutant K184R remained ubiquitinated in our assays, suggesting additional lysines within NP can be used for ubiquitin conjugation (Fig. 1F). These findings indicate that IAV RNPs from multiple isolates are ubiquitinated. Further, they suggest that all of the RNP subunits have the potential to be ubiquitinated and that the RNP displays a complex polyubiquitination profile that is not solely associated with protein degradation via Ub K48-linked or K63-linked chains. The specific nature of this profile remains to be determined, but it may result from polyubiquitination at one or more lysines, monoubiquitination at multiple sites, or other less common modifications.

Host proteasome activity is essential for influenza virus polymerase function.

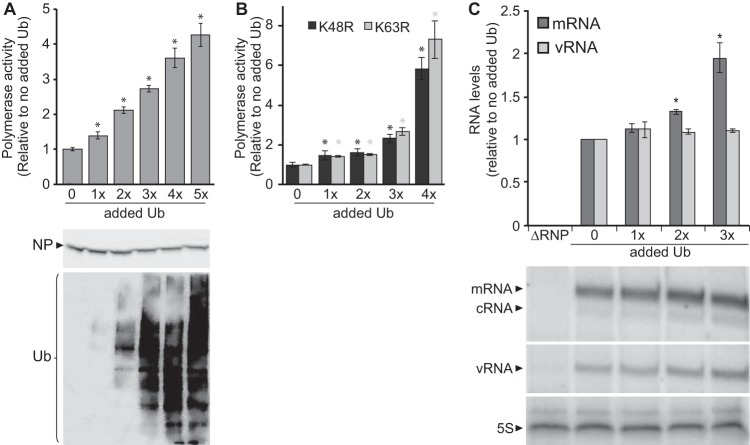

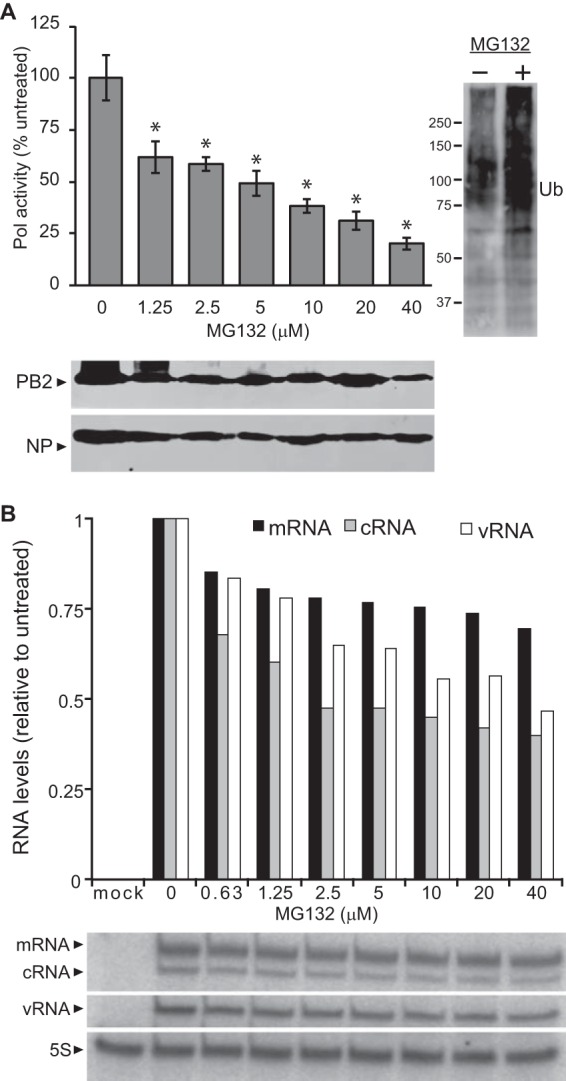

Ubiquitination mediates multiple cellular processes and is perhaps most commonly associated with proteasomal degradation (35). Ubiquitination had previously been associated with degradation of NP and free polymerase subunits (12, 14, 26). However, overexpression of WT or mutant forms of ubiquitin did not appreciably alter the steady-state levels of viral proteins (Fig. 1). Since IAV polymerase function is dependent on the stability of the RNP components, we sought to determine whether the proteasome had a significant effect on RNP steady-state levels and polymerase activity. IAV polymerase activity assays were performed with cells treated with increasing concentrations of proteasome inhibitor MG132. Polymerase activity decreased with increasing concentrations of MG132 (Fig. 2A). As expected, MG132 treatment stabilized proteins that would normally be degraded by the proteasome, resulting in increased levels of total polyubiquitinated proteins (Fig. 2A, right). Nonetheless, there were no overt changes in steady-state levels for PB2 or NP upon MG132 treatment (Fig. 2A). Primer extension assays were then performed to analyze production of viral mRNA, the replication intermediate cRNA, and the viral genome vRNA. These assays showed decreasing levels of all three RNA products with increase in MG132 concentration (Fig. 2B), indicating defects in both transcription and replication. These data suggest that host proteasome function is important for IAV polymerase activity independent of the degradation of RNP components, providing a discrete step in the viral life impacted by the previously identified postfusion role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (21).

FIG 2.

Host cell proteasome function is important for influenza A virus polymerase activity. (A) Influenza A virus polymerase activity assays were performed with HEK293T cells treated for 6 h with increasing concentrations of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 prior to lysis. NP protein expression was analyzed by Western blotting. Molecular masses in kDa are indicated. Data are normalized to untreated cells (n = 3 ± standard deviation). *, P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA compared to untreated control. (B) Primer extension assays were performed to quantify RNP transcription (mRNA) and replication (cRNA and vRNA) in the presence of increasing concentrations of MG132. 5S rRNA served as a loading control. The viral RNA levels under each condition were normalized to polymerase activity in the absence of MG132.

Ubiquitination enhances influenza A virus polymerase function.

Our data suggested that the IAV RNP components were ubiquitinated during infection and that the host proteasome function was essential for IAV polymerase activity, yet these processes did not have a major impact on protein steady state. This raised the question of whether ubiquitin exerts regulatory roles on the influenza polymerase function that are independent of proteasomal degradation, similar to other cellular activities that are regulated by ubiquitin and independent of proteasomal degradation, including protein-protein interactions, subcellular localization, and vesicular trafficking (35). Given that proteasomal activity maintains an equilibrium between free ubiquitin and conjugated ubiquitin, blocking proteasomal function would shift the equilibrium and deplete the free ubiquitin pool (35). We therefore, hypothesized that maintaining a pool of free unconjugated ubiquitin is necessary for IAV polymerase function given that inhibition of the proteasome decreased polymerase function (Fig. 2). To test this possibility, we performed polymerase activity assays of cells expressing increasing amounts of exogenous ubiquitin and demonstrated a strong correlation between enhanced polymerase activity and increased ubiquitin levels (Fig. 3A). Importantly, ubiquitin expression did not significantly alter the steady-state levels of NP, nor did it cause a bulk shift of NP into higher-molecular-mass ubiquitinated species (Fig. 3A). It is possible that only a fraction of total NP is ubiquitinated. Similar results were obtained using a GFP reporter, excluding any reporter-specific effects (unpublished data). Polymerase activity assays were repeated using K48R and K63R ubiquitin mutants and again demonstrated that increasing levels of ubiquitin enhanced polymerase activity (Fig. 3B), suggesting that these linkages were not essential for enhancement of IAV polymerase function. Primer extension assays then delineated the impact of ubiquitin expression on polymerase function. RNPs reconstituted with a vNA template produced larger amounts of all viral RNA products in cells expressing increased amounts of ubiquitin (Fig. 3C). cRNA levels were too close to the background level to be reliably quantified across all conditions, but they also showed a trend toward increased levels in the presence of excess ubiquitin. These results suggest that ubiquitin expression enhances global polymerase activity as we detected enhanced accumulation of all three RNA transcripts.

FIG 3.

Increased ubiquitination enhances influenza A virus polymerase function. (A) Polymerase activity assays were performed with HEK293T cells expressing the IAV RNP and increasing amounts of cotransfected HA-ubiquitin. HA-ubiquitin and NP protein expression was analyzed by Western blotting. (B) Polymerase activity assays were performed as in panel A with increasing amounts of cotransfected K48R or K63R mutant HA-ubiquitin. Data are normalized to cells lacking exogenous ubiquitin (n = 3 ± standard deviation). *, P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA compared to cells without exogenous ubiquitin. (C) Primer extension assays measured RNA transcripts generated in HEK293T cells expressing the IAV RNP, a vNA template, and increasing amounts of HA-ubiquitin. 5S rRNA served as a loading control. Quantified RNA levels were normalized to those present in cells lacking exogenous ubiquitin.

Ubiquitin mediated enhancement of IAV polymerase function is independent of NP.

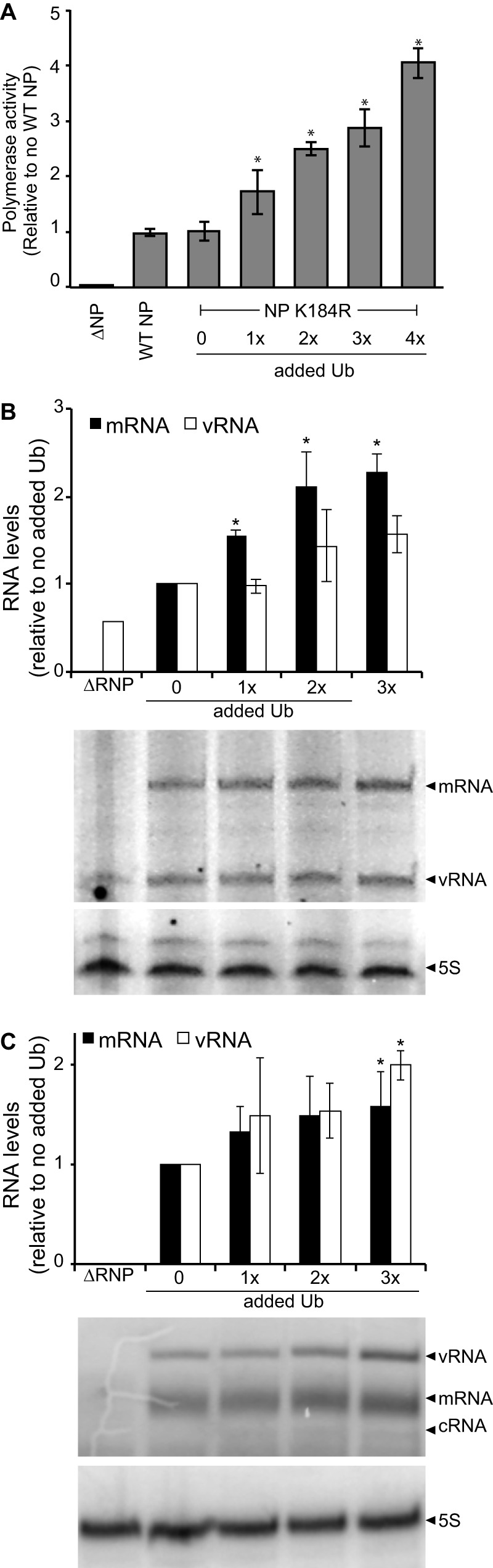

Ubiquitination of NP at K184 was previously reported to enhance RNA binding and replication of the viral genome (13). To establish whether the ubiquitin-mediated enhancement of polymerase function that we have detected was based on NP K184 ubiquitination, we tested the effect of increasing ubiquitin expression on polymerase activity of RNPs reconstituted with NP K184R (Fig. 4A). Despite the absence of this well-characterized ubiquitination site, the polymerase activity of NP K184R RNPs was enhanced by increased ubiquitin expression. Our prior analyses had also shown that NP K184R is ubiquitinated and demonstrate ubiquitination patterns similar to that of WT NP (Fig. 1F). We performed primer extension assays to quantify the different RNA species generated by NP K184R RNPs. Ubiquitin expression increased levels of mRNA, cRNA, and vRNA (Fig. 4B), consistent with the results of our polymerase activity assays. The NP K184R mutation did, however, reduce cRNA levels to the background level in the absence of added ubiquitin, such that they could not be reliably quantified (Fig. 4B). This agrees with prior data showing that the NP K184R mutant exhibits selective defects in RNA synthesis resulting in reduced levels of cRNA and vRNA (13). To further test the requirement of NP for ubiquitin-mediated enhancement, we performed primer extension assays using micro-vRNPs in the presence of increasing ubiquitin expression. Micro-vRNA-like templates are short RNAs (∼76 nt or less) containing viral UTRs that are replicated and transcribed by the polymerase in the absence of NP (30, 36). A 77-nt micro-vRNA generated from the NP gene segment was used as a template during primer extension assays performed with increasing amounts of ubiquitin but without NP. These assays revealed higher levels of all RNA products in response to increased ubiquitin, even in the absence of NP (Fig. 4C), paralleling results obtained in the presence of WT NP or the monoubiquitin-deficient NP K184R. cRNA is not routinely detected when using micro-vRNAs as a template (30) and thus could not be quantified here, even though we detect cRNA when polymerase activity is enhanced by ubiquitin expression. Collectively, the primer extension assays demonstrated decreased polymerase activity when the proteasome is inhibited (Fig. 2B) and increased activity in the presence of additional ubiquitin for WT RNPs (Fig. 3C), monoubiquitin-deficient NP K184R RNPs (Fig. 4B), and even for the NP-independent micro-vRNPS (Fig. 4C). Thus, it is likely that ubiquitination stimulates polymerase activity by directly impacting the polymerase, independent of NP or subsequent RNP assembly.

FIG 4.

Ubiquitin-mediated enhancement of influenza virus polymerase activity does not require NP. (A) Polymerase activity assays were performed with HEK293T cells expressing increasing amounts of HA-ubiquitin and IAV RNPs reconstituted with either WT NP, the mutant NP K184R, or empty plasmid (ΔNP). Data are normalized to cells expressing WT NP in the absence of exogenous ubiquitin (n = 3 ± standard deviation). *, P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA compared to NP K184R without ubiquitin. (B) Primer extension assays measured RNA transcripts generated in HEK293T cells expressing the IAV polymerase, mutant NP K184R, a vNA template, and increasing amounts of HA-ubiquitin. 5S rRNA serves as a loading control. RNA levels were normalized to those detected in cells expressing the RNP alone. (C) Influenza virus polymerase activity was reconstituted in the absence of NP using a 77-nt microgene template. Activity was measured in the presence of increasing amounts of HA-ubiquitin. RNA products were detected by primer extension, quantified, and normalized to levels present in the absence of HA-ubiquitin.

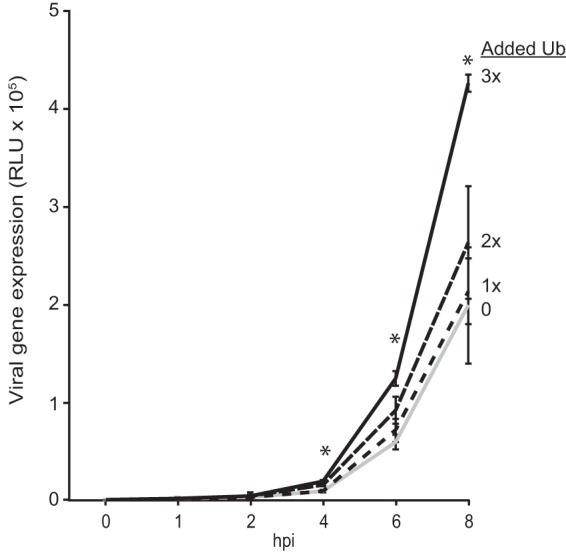

Ubiquitin expression enhances viral gene expression early during infection.

Our data have shown that ubiquitin expression enhanced polymerase function, predicting that viral gene expression during infection should also be enhanced under similar conditions. We therefore sought to establish whether ubiquitin expression impacts polymerase activity not only in polymerase assays but also during infection. Cells expressing increasing amounts of ubiquitin were infected with our highly sensitive NanoLuc reporter virus PASTN to quantify gene expression (34). We detected ubiquitin-dependent increases in viral gene expression as early as 2 h postinfection (hpi) that became more pronounced throughout the time course (Fig. 5). These data reinforce results from our polymerase activity and primer extension assays, and combined they demonstrate stimulation of polymerase activity by elevated ubiquitin expression in both the replicon-based assays and during infection.

FIG 5.

Ubiquitination enhances viral gene expression during infection. HEK293T cells expressing increasing amounts of HA-ubiquitin were infected with PASTN virus at an MOI of 0.1 for 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h. Following infection, gene expression was measured by a luciferase activity assay. RLU, relative light units. n = 3 ± standard deviation. *, P < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA between infection without added ubiquitin and cells treated with 3× ubiquitin.

DISCUSSION

The IAV RNP complex is the minimal viral component capable of RNA synthesis during viral infection (2, 3). The influenza virus polymerase transcribes viral mRNA, synthesizes the replication intermediate cRNA, and produces genomic vRNA. These processes are temporally regulated during the viral life cycle, in part by posttranslational modifications to NP and polymerase proteins. Here we show that ubiquitin and ubiquitination stimulate influenza virus polymerase activity and may be important regulators of polymerase activity during infection. RNPs from multiple viral strains were ubiquitinated, and all of the protein subunits in the RNP—PB1, PB2, PA, and NP—were subject to modification. Whereas ubiquitination is frequently associated with proteasomal degradation, we did not detect any notable change in protein steady-state levels either when ubiquitination of the viral proteins was increased or when the proteasome was inhibited. However, inhibition of the proteasome impaired polymerase function and alteration of ubiquitination changed production of viral mRNA, cRNA, and vRNA. These data suggest ubiquitination plays a regulatory role that stimulates activity of the viral polymerase independent of its proteasomal degradation.

Ubiquitin and the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway impact key steps during the life cycle of many viruses (37). These include important roles for ubiquitination in viral entry, endosomal sorting, degradation of host restriction factors, regulation of innate antiviral signaling pathways, control of viral protein localization and stability, and finally trafficking and budding of progeny virions (37). During influenza virus infection, the E3 ubiquitin ligases Itch and Nedd4 are important during entry for release from the endosome (22, 23), and ubiquitin found within virions is important for disassembly of incoming viral cores by the host aggresome (24). We have shown here that proteasome activity is important postentry for maximal activity of the viral polymerase (Fig. 2) and that ubiquitination of RNP subunits is associated with increased synthesis of all viral RNA products. Our data are supported by prior reports showing ubiquitination of individual subunits of the RNP (12–14, 26).

Whereas our data demonstrate stimulatory effects of ubiquitin on polymerase activity, ubiquitination of NP and the polymerase proteins can direct their degradation by the proteasome. The E3 ligases TRIM22 and TRIM32 have been reported to be antiviral as they mediate proteasomal degradation of NP and PB1, respectively (14, 26). Recent results have also shown an antiviral role for the ubiquitination and degradation of PB2 and PA, possibly associated with ADP ribosylation, another PTM these proteins undergo (12). It will be important to determine the E3 ligase(s) as well as the ADP ribosyltransferase(s) that target PB2 and PA.

Polyubiquitination of NP by the E3 ligase TRIM22 directs its degradation and restricts virus replication (26). In contrast, monoubiquitination at K184 is hypothesized to enhance replication of the viral genome (13, 26). Deubiquitination of NP K184 by the host ubiquitin-specific protease Usp11 decreased polymerase activity and reduced viral replication. We also detected NP ubiquitination in our assays; however, this was polyubiquitination and was not dependent on K184, implicating additional ubiquitination sites within NP. Moreover, increased ubiquitination of NP did not reduce steady-state levels in our experiments, nor did we detect any increase in NP levels when we inhibited the proteasome, suggesting ubiquitination of NP might have additional impacts. We therefore sought to establish whether the enhanced polymerase activity associated with increased ubiquitination was due to NP ubiquitination, as has been implicated before, or resulted from modification of the polymerase. When we tested the impact of increased ubiquitin expression on polymerase activity in the presence of the NP K184R mutant that lacks the monoubiquitination site, we still detected an enhancement in polymerase activity. Primer extension experiments on RNAs produced by RNPs containing the NP K184R mutant showed that mRNA, vRNA, and cRNA all increased with increasing ubiquitin expression. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the increase in polymerase activity was largely independent of NP; increased ubiquitin expression enhanced RNA synthesis in the microgene system that does not require NP (30, 36). Together, these data suggest that this increase in polymerase activity occurs via a different mechanism than the previously described monoubiquitination at NP K184 ubiquitination and is distinct from the antiviral ubiquitination catalyzed by TRIM22.

Since the IAV polymerase function is critical for the viral life cycle, we would expect that an enhancement of polymerase function would cause enhanced viral gene expression in an infection setting. We employed our recombinant reporter virus to measure viral gene expression during infection in increased ubiquitin expression (34). Our results showed that ubiquitin expression increased viral gene expression at early stages of infection; thus the enhanced polymerase function observed in replicon assays and primer extension is reflective of events that occur in a virus infection setting. This is consistent with prior work showing that the proteasome and ubiquitination are important during postfusion and postnuclear entry steps (21) and combined with our replicon assays directly implicates the viral polymerase in this process. Changes in entry might also contribute to the enhanced gene expression detected in infections with elevated ubiquitin levels. Inhibition of the proteasome blocks virion release from the endosome, and the E3 ligase Itch plays a key role in this process (23, 38). Elevated ubiquitin levels may increase both endosomal release and polymerase function. These enhancing activities of ubiquitin may be counteracted at other stages of infection when ubiquitination plays an antiviral role (e.g., the TRIM22-directed turnover of NP). The balance between these opposing functions may dictate how ubiquitination impacts the outcome of multicycle replications. The molecular mechanisms by which ubiquitination enhances polymerase function remain unclear. As all of the polymerase subunits are subject to ubiquitination, and this does not appear to be related to proteasomal degradation as we detected no significant changes in protein steady-state levels, it is possible that these modifications directly impact protein localization or protein-protein interactions. It has also been suggested that ubiquitination and the proteasome can have indirect effects that stimulate infection, such as activating the NF-κB pathway and other host factors that are important for viral replication or degrading cellular factors that restrict infection (21). Thus, influenza virus exploits and relies on the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway at multiple steps during the early stages of infection and may be particularly sensitive to therapeutic interventions that disrupt these host processes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Gabuzda for providing reagents and members of the Mehle laboratory for valuable contributions. Anti-RNP antibody (NR-3133) was obtained through the NIH Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository, NIAID, NIH.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R00GM088484 and R01AI125271), a Shaw Scientist award, and an American Lung Association Basic Research grant (RG-310016) to A.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaw ML, Palese P. 2014. Orthomyxoviruses, p 1151–1185. In Knipe DM, Howley PM (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehle A, McCullers JA. 2013. Structure and function of the influenza virus replication machinery and PB1-F2, p 133–145. In Webster RG, Monto AS, Braciale TJ, Lamb RA (ed), Textbook of influenza, 2nd ed John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fodor E. 2013. The RNA polymerase of influenza a virus: mechanisms of viral transcription and replication. Acta Virol 57:113–122. doi: 10.4149/av_2013_02_113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dias A, Bouvier D, Crepin T, McCarthy AA, Hart DJ, Baudin F, Cusack S, Ruigrok RW. 2009. The cap-snatching endonuclease of influenza virus polymerase resides in the PA subunit. Nature 458:914–918. doi: 10.1038/nature07745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guilligay D, Tarendeau F, Resa-Infante P, Coloma R, Crepin T, Sehr P, Lewis J, Ruigrok RW, Ortin J, Hart DJ, Cusack S. 2008. The structural basis for cap binding by influenza virus polymerase subunit PB2. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15:500–506. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan P, Bartlam M, Lou Z, Chen S, Zhou J, He X, Lv Z, Ge R, Li X, Deng T, Fodor E, Rao Z, Liu Y. 2009. Crystal structure of an avian influenza polymerase PA(N) reveals an endonuclease active site. Nature 458:909–913. doi: 10.1038/nature07720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Subbarao EK, London W, Murphy BR. 1993. A single amino acid in the PB2 gene of influenza A virus is a determinant of host range. J Virol 67:1761–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robb NC, Smith M, Vreede FT, Fodor E. 2009. NS2/NEP protein regulates transcription and replication of the influenza virus RNA genome. J Gen Virol 90:1398–1407. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.009639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutchinson EC, Denham EM, Thomas B, Trudgian DC, Hester SS, Ridlova G, York A, Turrell L, Fodor E. 2012. Mapping the phosphoproteome of influenza A and B viruses by mass spectrometry. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002993. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pal S, Santos A, Rosas JM, Ortiz-Guzman J, Rosas-Acosta G. 2011. Influenza A virus interacts extensively with the cellular SUMOylation system during infection. Virus Res 158:12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han Q, Chang C, Li L, Klenk C, Cheng J, Chen Y, Xia N, Shu Y, Chen Z, Gabriel G, Sun B, Xu K. 2014. Sumoylation of influenza A virus nucleoprotein is essential for intracellular trafficking and virus growth. J Virol 88:9379–9390. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00509-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu CH, Zhou L, Chen G, Krug RM. 2015. Battle between influenza A virus and a newly identified antiviral activity of the PARP-containing ZAPL protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:14048–14053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509745112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao TL, Wu CY, Su WC, Jeng KS, Lai MM. 2010. Ubiquitination and deubiquitination of NP protein regulates influenza A virus RNA replication. EMBO J 29:3879–3890. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu B, Wang L, Ding H, Schwamborn JC, Li S, Dorf ME. 2015. TRIM32 senses and restricts influenza A virus by ubiquitination of PB1 polymerase. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004960. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng W, Li J, Wang S, Cao S, Jiang J, Chen C, Ding C, Qin C, Ye X, Gao GF, Liu W. 2015. Phosphorylation controls the nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of influenza A virus nucleoprotein. J Virol 89:5822–5834. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00015-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neumann G, Castrucci MR, Kawaoka Y. 1997. Nuclear import and export of influenza virus nucleoprotein. J Virol 71:9690–9700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chenavas S, Estrozi LF, Slama-Schwok A, Delmas B, Di Primo C, Baudin F, Li X, Crepin T, Ruigrok RW. 2013. Monomeric nucleoprotein of influenza A virus. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003275. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mondal A, Potts GK, Dawson AR, Coon JJ, Mehle A. 2015. Phosphorylation at the homotypic interface regulates nucleoprotein oligomerization and assembly of the influenza virus replication machinery. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004826. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turrell L, Hutchinson EC, Vreede FT, Fodor E. 2015. Regulation of influenza A virus nucleoprotein oligomerization by phosphorylation. J Virol 89:1452–1455. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02332-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komander D, Rape M. 2012. The ubiquitin code. Annu Rev Biochem 81:203–229. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060310-170328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Widjaja I, de Vries E, Tscherne DM, García-Sastre A, Rottier PJ, de Haan CA. 2010. Inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome system affects influenza A virus infection at a postfusion step. J Virol 84:9625–9631. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01048-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chesarino NM, McMichael TM, Yount JS. 2015. E3 ubiquitin ligase NEDD4 promotes influenza virus infection by decreasing levels of the antiviral protein IFITM3. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005095. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su WC, Chen YC, Tseng CH, Hsu PW, Tung KF, Jeng KS, Lai MM. 2013. Pooled RNAi screen identifies ubiquitin ligase Itch as crucial for influenza A virus release from the endosome during virus entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:17516–17521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312374110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banerjee I, Miyake Y, Nobs SP, Schneider C, Horvath P, Kopf M, Matthias P, Helenius A, Yamauchi Y. 2014. Influenza A virus uses the aggresome processing machinery for host cell entry. Science 346:473–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1257037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw ML, Stone KL, Colangelo CM, Gulcicek EE, Palese P. 2008. Cellular proteins in influenza virus particles. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000085. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Pietro A, Kajaste-Rudnitski A, Oteiza A, Nicora L, Towers GJ, Mechti N, Vicenzi E. 2013. TRIM22 inhibits influenza A virus infection by targeting the viral nucleoprotein for degradation. J Virol 87:4523–4533. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02548-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe T, Watanabe S, Kawaoka Y. 2010. Cellular networks involved in the influenza virus life cycle. Cell Host Microbe 7:427–439. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehle A, Doudna JA. 2008. An inhibitory activity in human cells restricts the function of an avian-like influenza virus polymerase. Cell Host Microbe 4:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehle A, Strack B, Ancuta P, Zhang C, McPike M, Gabuzda D. 2004. Vif overcomes the innate antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by promoting its degradation in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem 279:7792–7798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313093200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turrell L, Lyall JW, Tiley LS, Fodor E, Vreede FT. 2013. The role and assembly mechanism of nucleoprotein in influenza A virus ribonucleoprotein complexes. Nat Commun 4:1591. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dos Santos Afonso E, Escriou N, Leclercq I, van der Werf S, Naffakh N. 2005. The generation of recombinant influenza A viruses expressing a PB2 fusion protein requires the conservation of a packaging signal overlapping the coding and noncoding regions at the 5′ end of the PB2 segment. Virology 341:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirui J, Bucci MD, Poole DS, Mehle A. 2014. Conserved features of the PB2 627 domain impact influenza virus polymerase function and replication. J Virol 88:5977–5986. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00508-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choo YS, Zhang Z. 19 August 2009. Detection of protein ubiquitination. J Vis Exp doi: 10.3791/1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tran V, Moser LA, Poole DS, Mehle A. 2013. Highly sensitive real-time in vivo imaging of an influenza reporter virus reveals dynamics of replication and spread. J Virol 87:13321–13329. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02381-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. 1998. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem 67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Resa-Infante P, Recuero-Checa MA, Zamarreno N, Llorca O, Ortin J. 2010. Structural and functional characterization of an influenza virus RNA polymerase-genomic RNA complex. J Virol 84:10477–10487. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01115-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo H. 2016. Interplay between the virus and the ubiquitin-proteasome system: molecular mechanism of viral pathogenesis. Curr Opin Virol 17:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khor R, McElroy LJ, Whittaker GR. 2003. The ubiquitin-vacuolar protein sorting system is selectively required during entry of influenza virus into host cells. Traffic 4:857–868. doi: 10.1046/j.1398-9219.2003.0140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]