Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Because irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional medical condition for which there is no curative therapy, treatment goals emphasize relieving gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and optimizing the quality of life (QOL). This study sought to characterize the magnitude of the associations between QOL impairment, fear of IBS symptoms, and confounding variables.

METHODS

Subjects included 234 Rome III-diagnosed IBS patients (mean age, 41 years, 79%, female) without comorbid organic GI disease who were referred to two specialty care clinics of an National Institutes of Health trial for IBS. Subjects completed a testing battery that included the IBS-specific QOL (IBS-QOL), SF-12 (generic QOL), the UCLA GI Symptom Severity Scale, the Visceral Sensitivity Index, Trait Anxiety Inventory, and Brief Symptom Inventory.

RESULTS

Multiple linear regression was used to develop a model for predicting QOL. Data supported an overall model that included sociodemographic, clinical (e.g., current severity of GI symptoms), and psychosocial (e.g., fear of GI symptoms, distress, neuroticism) variables, accounting for 48.7% of the variance in IBS-QOL (F=15.1, P <0.01). GI symptom fear was the most robust predictor of IBS-QOL (β=−0.45 P <0.01), accounting for 14.4% of the total variance.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients’ fear that GI symptoms have aversive consequences, is a predictor of QOL impairment that cannot be fully explained by the severity of their GI symptoms, overall emotional well-being, neurotic personality style, or other clinical features of IBS. An understanding of the unique impact that GI symptom fears have on QOL can inform treatment planning and help gastroenterologists to better manage more severe IBS patients seen in tertiary care clinics.

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common, often disabling, gastrointestinal (GI) disorder characterized by abdominal pain associated with altered bowel habits (i.e., constipation and/or diarrhea) (1). As one of the most common diagnoses seen by gastroenterologists and primary care physicians (2), IBS exacts substantial economic (3) and social (4,5) costs. Its impact on health-related quality of life (QOL) rivals that of diabetes and end-stage renal disease (6).

Because IBS lacks a reliable biomarker, it is best understood from a biopsychosocial model (7) that emphasizes the reciprocal and interactive relationship among biological and psychosocial factors. With respect to psychosocial factors, the way patients’ process information—expressed through their beliefs, expectations, thinking style, and other cognitive variables—has a particularly strong impact on IBS outcomes. One cognitive variable that has received a great deal of attention is GI-specific anxiety (GSA (8)). GSA refers to a specific fear of GI symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain or discomfort). A person with high GSA is likely to become acutely fearful because of beliefs that GI symptoms have aversive physical, psychological, or social consequences. The belief that GI symptoms are signs of imminent threat is thought to increase the frequency or intensity of symptoms, heighten central nervous system hypervigilance toward potentially aversive visceral stimuli or their cues, and cause excessive avoidance of activities or situations where GI symptoms are expected to occur. GSA differs from other clinically relevant psychological variables such as general anxiety, which is “free-floating” and not linked to a specific cause or situation, or general distress.

Support for the importance of the GSA construct comes from research showing that fear of GI symptoms mediates the relationship between general distress and GI symptom severity and is a key predictor of IBS diagnosis (9). Regarded as a marker of overresponsiveness to visceral sensations, fear of GI symptoms is believed to aggravate symptoms through alterations in autonomic and pain facilitation, as well as cognitive mechanisms (9). Heightened fear of GI symptoms may also aggravate IBS-specific dimensions of the QOL, which is increasingly recognized as a critical health outcome, particularly for benign medical illnesses like IBS whose impact (and treatment response) is gauged by its day-to-day burden (10,11). The extent to which patients’ fears impact the specific dimensions of the QOL relevant to IBS patients (i.e., IBS-specific QOL) has not been explored. A meaningful relationship between IBS-QOL and GI symptom fear would require evidence that it is independent of the effects of confounding factors such as GI symptom severity, emotional distress, demographics, and personality style (e.g., neuroticism) that bear on QOL. To this end, we predicted the following: (i) fear of GI symptoms will be significantly associated with poorer IBS-specific QOL; (ii) the relationship between fear of GI symptoms and QOL will remain even after controlling for potentially confounding variables; and (iii) the magnitude of the relationship between QOL and fear of GI symptoms will be strongest for measures of QOL owing to IBS symptoms than for generic measures of QOL, which have been the primary focus of IBS researchers.

METHODS

Participants included 234 consecutively evaluated IBS patients recruited at two tertiary academic medical centers in Buffalo, NY and Chicago, IL, as part of an National Institutes of Health-funded clinical trial, the details of which can be found elsewhere (12). Participants were enrolled primarily through local media coverage, community advertising, and physician referral. To be eligible for the study, all participants must have met the Rome III diagnostic criteria (13) as determined by a board-certified gastroenterologist. Because this study was conducted as part of a clinical trial for moderate to severely affected patients with IBS (12) participants must have also reported IBS symptoms of at least moderate intensity (i.e., symptom frequency of at least twice weekly for a minimum duration of 6 months and causing life interference). Subjects with presence of a comorbid organic GI illness that would adequately explain GI symptoms, mental retardation, current or past diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders, current diagnosis of depression with suicidal ideation, and current diagnosis of psychoactive substance abuse were excluded. Institutional review board approval (University at Buffalo, 19 May 2009; Northwestern University, 19 December 2008) and written, signed, informed consent were obtained before study initiation. The study was completed in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Procedure

After a brief telephonic interview to determine eligibility, participants were scheduled for a medical examination administered by a board-certified gastroenterologist to confirm Rome diagnosis of IBS and testing drawn from a battery of psychometrically validated measures detailed below.

Measures

Fear of GI symptoms

Fear of GI symptoms was assessed using the validated (VSI (8)) 15-item Visceral Sensitivity Index. Items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale (0=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree) and specify a possible negative consequence to the experience of GI symptom-specific anxiety. Items were reverse scored and summed, yielding a range of scores from 0 (no fear of GI symptoms) to 75 (strong fear of GI symptoms).

IBS symptom severity

Global IBS symptom severity was measured using the single item UCLA Global Severity of GI Symptoms Scale. The UCLA Global Severity of GI Symptoms Scale is a validated (14) 21-Point rating scale that requires participants to rate the overall severity of their GI symptoms from 0 (no symptoms) to 20 (most intense symptoms imaginable) during the past week.

IBS-specific QOL

The IBS-QOL (15) is a 34-item measure constructed specifically to assess the perceived impact of IBS on the QOL in eight domains (dysphoria, interference with activity, body image, health worry, food avoidance, social reaction, sexual dysfunction, and relationships). Each item was scored on a five-point scale (1=not at all to 5=a great deal). Items were scored to derive an overall total score of IBS-related QOL ranging from 0 (poor QOL) to 100 (maximum QOL).

Global QOL

The 12-item Short Form or SF-12 (16) is a generic QOL measure based on the SF-36. The SF-12 captures approximately 90% of the variance of the SF-36 (17). The SF-12 provides two summary indices of health-related quality of life: the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS). PCS and MCS scores were computed using the scores of 12 questions and range from 0 to 100 (100 (M=50, s.d.=10), where zero indicates the lowest level of health measured by the scales and 100 indicates the highest level of health.

Neuroticism

We used the short form version of the Trait subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI Trait) to measure the trait of neuroticism. Its 20 items require subjects (18) to indicate how they generally feel by rating the frequency of their feelings of anxiety on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). High scores are characteristic of patients with a general disposition toward stress responsiveness.

Global distress

Psychological distress was assessed using the 18-item version of the Brief Symptom Inventory (19). The BSI-18 requires respondents to indicate on a five-point scale (0=not at all to 4=extremely) their level of distress of 18 somatic and psychological symptoms for three types of problems (e.g., anxiety, somatization, and depression). The average intensity of all items yields a composite index of psychological distress (the Global Severity Index (GSI)). The GSI has been used extensively to measure psychological distress in patients with IBS (20,21).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (e.g., means, s.d., and percentages) were used to summarize demographic and clinical data. Bivariate analyses were used to examine the relationships among the variables before multivariate modeling. Means and 95% confidence intervals were computed for the study (i.e., dependent) variables within the independent, categorical variables (i.e., gender, education, marital status, and IBS subtype). Pearson’s correlation coefficients were generated to characterize the association between independent, continuous variables, and the study variables. Alpha levels for determining statistical significance were set at 0.01 to correct for multiple analyses. For the confirmatory multivariate analyses, the independent variables were grouped into three conceptually distinct categories. The first category consisted of sociodemographics—age, sex, education, yearly income, and marital status (married vs. other). The second category consisted of clinical features—duration of symptoms, IBS subtype, IBS severity over the past 7 days, and psychological dysfunction (trait anxiety and global psychological distress). The third category consisted of fear of GI symptoms. Using hierarchical linear regression analyses, each category of predictors was entered in the following order for each dependent variable: sociodemographics (Step 1), clinical features (Step 2), and fear of GI symptoms (Step 3). Dependent variables consisted of IBS-QOL and two indices of generic QOL: the PCS score of the SF-12 (SF-12 PCS) and its MCS score (SF-12 MCS). We used SPSS version 22 (Chicago, IL) to perform all statistical analyses.

Although this is a secondary analysis of a larger data set of an National Institutes of Health study, the minimum number of subjects for this substudy was determined by an a p riori power analysis. On the basis of a probability level of 0.05, 11 predictors, an anticipated effect size of 0.15, and power level of 0.9, the minimum number of subjects was 152 (22,23). To increase rigor (i.e., reducing probability of making a Type 1 error), we conducted a retrospective power analysis using an alpha level of 0.01, which yielded a minimum sample size of 198. With a sample size of 234, it is unlikely that findings described below can be attributed to a limited sample size.

RESULTS

Descriptive analyses

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample IBS are presented in Table 1. The mean total score on the UCLA Global Severity of GI Symptoms Scale for the sample was 11.1 (s.d.=3.9), which corresponds to a moderate level of GI symptom severity on a 21-point scale, which is consistent with other studies (14). Patients with a mean of 56.5 (s.d.=18.9) on the IBS-QOL are regarded as having significant QOL impairment caused by IBS symptoms (24). Sample means for the physical component (SF-12 PCS; M=43.8, s.d.=9.4) and the mental component (SF-12 MCS; M=40.9, s.d.=10.7) of the global QOL measure fall within “impaired” ranges of mental and physical functioning for IBS patients (25). With respect to distress variables, the mean trait anxiety score (20.5, s.d.=6.2) fell at the 75th percentile, meaning that patients scored, on average, higher than the 75th percentile of other individuals completing the short form of the STAI-Trait (26). A raw score of 14.3 (s.d.=12.1) on the measure of global psychological distress (BSI-GSI) corresponds with a percentile rank of 56 (19).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics (N=234).

| M (s.d.) | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 40.9 (14.9) | |

| Gender (% female) | 183 (79.2) | |

| Race (% white) | 208 (88.9) | |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school diploma | 6 (2.6) | |

| High school diploma/GED | 55 (23.5) | |

| Associate/college degree | 102 (43.6) | |

| Graduate degree | 71 (30.3) | |

| Income | 62.5K (48.7 K) | |

| Duration of IBS sx (years) | 16.2 (14.0) | |

| IBS subtype | ||

| Constipation | 68 (29.1) | |

| Diarrhea | 97 (41.4) | |

| Mixed | 59 (25.2) | |

| Undifferentiated | 10 (4.3) | |

| IBS symptom severity | 11.1 (3.9) | |

| Neuroticism (STAI-Trait) | 20.5 (6.2) | |

| Global distress (BSI-GSI) | 14.3 (12.1) | |

| Fear of GI sx (VSI) | 44.7 (14.2) | |

| IBS-QOL | 56.5 (18.9) | |

| SF-12 PCS | 43.8 (9.4) | |

| SF-12 MCS | 40.9 (10.7) |

BSI-GSI, Brief Symptom Inventory-Global Severity Index; GED, General Equivalency Degree; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-QOL, IBS-specific Quality of Life; SF-12 PCS, SF-12 Physical Component Summary; SF-12 MCS, SF-12 Mental Component Summary; VSI, Visceral Sensitivity Index.

Bivariate analyses

Table 2 depicts the means and 95% confidence intervals of the study variables for each level of the categorical, independent variables. Participants with less than high school education had lower scores on the SF-12 PCS compared with all other participants. Similar scores were observed for the subcategories of gender, marital status, and IBS subtype on all of the three QOL outcome measures.

Table 2. Means and 95% confidence intervals of the study variables for categorical, independent variables.

| SF-12 PCS | SF-12 MCS | IBS-QOL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 46.3 (44.3–48.3) |

40.3 (37.4–43.0) |

58.1 (53.3–62.7) |

| Female | 43.1 (41.7–44.4) |

41.0 (39.4–42.6) |

56.1 (53.0–58.8) |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school diploma |

32.6 (25.5–41.0) |

39.9 (30.0–49.5) |

42.3 (34.6–52.8) |

| High diploma/GED | 42.2 (39.5–44.6) |

39.9 (36.8–43.1) |

52.5 (47.1–58.3) |

| Associate/college degree | 44.8 (43.1–46.5) |

40.1 (37.9–42.0) |

57.2 (53.1–60.5) |

| Graduate degree | 44.4 (42.1–46.6) |

42.8 (40.4–45.3) |

60.0 (56.2–63.4) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 44.0 (42.2–45.8) |

42.2 (40.2–44.3) |

56.2 (52.0–59.9) |

| Not married | 43.6 (41.8–45.3) |

39.9 (38.0–41.6) |

56.5 (53.4–59.6) |

| IBS subtype | |||

| Constipation | 43.5 (41.3–45.8) |

40.7 (38.1–43.1) |

56.0 (51.3–60.2) |

| Diarrhea | 43.2 (41.3–45.2) |

41.3 (39.2–43.3) |

55.6 (51.1–59.0) |

| Mixed | 44.4 (42.2–46.6) |

39.5 (36.8–42.3) |

57.1 (52.9–61.8) |

| Undifferentiated | 47.2 (41.3–52.5) |

45.9 (39.8–51.7) |

66.0 (56.8–74.3) |

GED, General Equivalency Degree; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-QOL, IBS-specific Quality of Life; SF-12-PCS, SF-12 Physical Component Summary; SF-12-MCS, SF-12 Mental Component Summary.

Generally speaking, clinical and potentially confounding variables and fear of GI symptoms were, as predicted, interrelated in the expected directions. Fear of GI symptoms was significantly and positively associated with both measures of psychological dysfunction (i.e. global distress and neuroticism). Individuals with stronger fears of GI symptoms reported higher levels of distress as measured by the BSI-GSI. They also reported higher levels of trait anxiety (neuroticism) as measured by the Trait Scale of the STAI. That is, individuals with stronger fears of GI symptoms reported a general disposition to respond fearfully to stressful situations. Fear of GI symptoms was significantly associated with global severity of IBS symptoms but not with duration of symptoms. With respect to QOL, fear of GI symptoms was correlated with both generic and disease-specific indices of QOL. With respect to these correlations, the strongest one was with the IBS-QOL, with patients with stronger fears of GI symptoms reporting greater QOL impairment due to IBS. Intercorrelations among all of the independent and dependent continuous variables are available as a Supplementary Table online.

Regression analyses

For each of the final models, data were screened for violations of the assumptions of linear regression prior to analysis. Boxplots and stem-and-leaf plots of the unstandarized residuals of each of the dependent variables suggest that the residuals are normally distributed. Also, Shapiro–Wilk statistics were all above 0.92 and nonsignificant. Scatterplots of the independent and dependent variables indicate linear relationships with no observed outliers. Durbin–Watson statistics were all between 1.4 and 2.6, which suggest independent errors. Examination of scatterplots of residuals vs predicted values indicates that the variances of the residuals are consistent over a range of predicted values and provide evidence of homogeneity of variance. Finally, multicollinearity does not appear to be an issue, with all variance inflation factors below 4.01 and tolerance factors above 0.29.

Table 3 shows the results of the sequential multiple linear regression analyses for the SF-12 PCS, SF-12 MCS, and IBS-QOL. In the first regression with the SF-12 PCS as the dependent variable, sociodemographic variables accounted for 13.7% of the variance. Yearly income was the only statistically significant independent predictor. In step 2, clinical variables explained an additional 14.0% of unique variance in the SF-12 PCS, with global severity of IBS symptoms and global psychological distress emerging as independent significant predictors. In the third and final step, fear of GI symptoms accounted for an additional 3.5% of the variance (P <0.01). To understand the nature of the relationship between fear of IBS symptoms and QOL impairment due to IBS, we relied on standardized coefficients, which are also called “beta weights” and designated by the Greek letter β (Table 3). They serve as standardized effect size statistics that are expressed in standard deviation units. It is difficult to compare the coefficient for different variables directly because they are typically measured on different scales. By converting numerical values to a common, standardized regression coefficient, we can directly compare the relationships between variables in the equation regardless of their unit of measurement (e.g., education levels, income, age, and pain intensity). Standardized regression coefficients measure change in the dependent variable that is produced by a 1 s.d. change in the predictor variable. In the first regression equation, a 1 s.d. change in fear of GI symptoms equals −0.22 s.d. in the SF-12 PCS in the direction of worse physical QOL.

Table 3. Sequential multiple regressions with the SF-12 PCS, SF-12 MCS, and the IBS-QOL as dependent variables.

| SF-12 PCS | SF-12 MCS | IBS-QOL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s.e. | β | s.e. | β | s.e. | β | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Age | 0.04 | −0.14 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.12 |

| Gender | 1.47 | −0.11 | 1.75 | 0.04 | 3.00 | −0.03 |

| Married | 1.38 | −0.09 | 1.65 | 0.06 | 2.82 | −0.12 |

| Education | 1.45 | −0.03 | 1.73 | 0.09 | 3.43 | −0.22 |

| Income | 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| Model: R2=0.137; ΔR2=0.137 | Model: R2=0.043; ΔR2=0.043 | Model: R2=0.099; ΔR2=0.099 | ||||

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Age | 0.04 | −0.20 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.11 |

| Gender | 1.39 | −0.12 | 1.40 | 0.01 | 2.67 | −0.07 |

| Married | 1.31 | −0.07 | 1.32 | 0.07 | 2.51 | −0.10 |

| Education | 1.34 | −0.08 | 1.35 | 0.07 | 4.18 | 0.09 |

| Income | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.03 |

| IBS Sx duration | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.05 |

| IBS Subtype | 1.96 | 0.07 | 2.99 | −0.07 | 5.86 | 0.04 |

| IBS Sx severity | 0.15 | −0.27 | 0.15 | −0.01 | 0.29 | −0.16 |

| Neuroticism | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.13 | −0.46 | 0.26 | −0.27 |

| Global distress | 0.07 | −0.26 | 0.07 | −0.24 | 0.14 | −0.24 |

| Model: R2=0.277; ΔR2=0.140 | Model: R2=0.441; ΔR2=0.398 | Model: R2=0.343; ΔR2=0.244 | ||||

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Age | 0.05 | −0.20 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| Gender | 1.36 | −0.11 | 1.41 | 0.01 | 2.37 | 0.04 |

| Married | 1.28 | −0.05 | 1.33 | 0.07 | 2.24 | 0.06 |

| Education | 1.32 | −0.07 | 1.37 | 0.06 | 2.30 | 0.06 |

| Income | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.03 |

| IBS sx duration | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.09 |

| IBS subtype | 2.91 | −0.15 | 3.02 | −0.08 | 5.20 | 0.09 |

| IBS sx severity | 0.15 | −0.24 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.26 | −0.10 |

| Neuroticism | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.14 | −0.45 | 0.24 | −0.11 |

| Global distress | 0.07 | −0.23 | 0.07 | −0.24 | 0.12 | −0.19 |

| Fear of GI sx | 0.05 | −0.22 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.45 |

| Model: R2=0.312; ΔR2=0.035 | Model: R2=0.441; ΔR2=0.000 | Model: R2=0.487; ΔR2=0.144 | ||||

GI, gastrointestinal; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-QOL, IBS-Quality of Life Instrument; SF-12 PCS, SF-12 Physical Component Summary; SF-12 MCS, SF-12 Mental Component Summary.

Note: Numerical values that are bolded are significant at P <0.01.

In the second regression with the SF-12 MCS as the dependent variable, sociodemographics accounted for only 4.3% of the variance. None of these factors in step 1 was a significant independent predictor. In step 2, the addition of clinical variables in the model predicted 39.8% of unique variance. Neuroticism and global psychological distress emerged as significant independent predictors of mental QOL. Finally, in step 3, fear of GI symptoms did not add any predictive value to the model. In the final model, clinical variables (i.e., neuroticism and global distress) were the best predictors of the mental aspect of QOL.

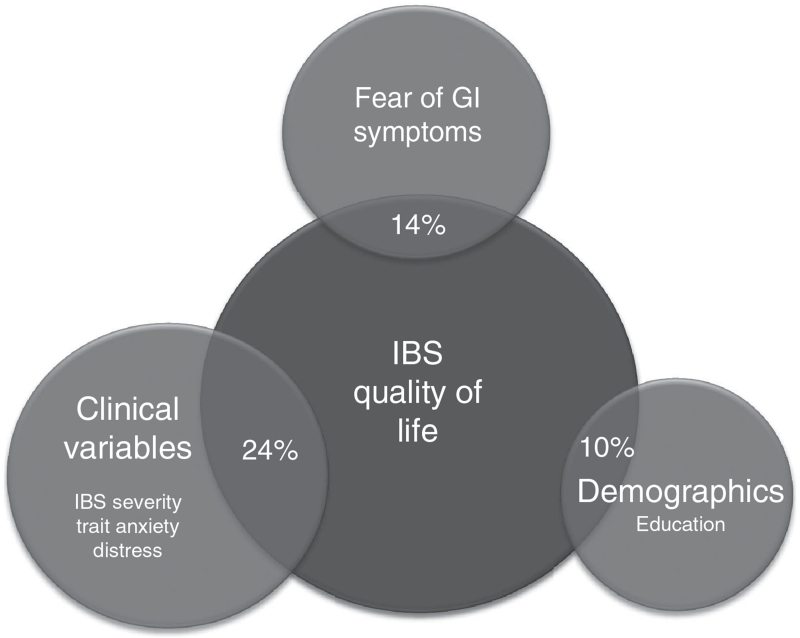

In the final regression analysis, sociodemographics (step 1) accounted for 9.9% of the variance in IBS-QOL, with education being the only significant independent predictor. In step 2, clinical variables explained an additional 24.4% of the variance in IBS-QOL, with IBS symptom severity, trait anxiety, and global psychological distress emerging as significant predictors. Finally, the addition of fear of GI symptoms in step 3 accounted for an additional 14.4% of the variance, making the complete final model account for 48.7% of the variation in IBS-QOL. Fear of GI symptoms was, on the basis of its β-value (β=−0.45), the most robust independent predictor of IBS-QOL. When holding all other independent variables constant, a one unit positive standard deviation change in fear of GI symptoms equals −0.45 s.d. change in IBS-QOL in the direction of worse QOL. By comparison, a 1 s.d. change in IBS symptom severity equals −0.10 s.d. change in IBS-QOL. These data are diagrammatically represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Total variation in IBS-QOL explained by all variables: 48%. The variance accounted for by fear of GI symptoms was above and beyond that accounted for by other variables (demographic and clinical variables). GI, gastrointestinal; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-QOL, IBS-specific quality of life.

DISCUSSION

This study sought to assess the relationship between QOL and the fears that IBS patients have about their IBS symptoms after taking into consideration potentially relevant clinical variables and patient characteristics. We found that a variety of physical (e.g., IBS symptom severity) and psychological (e.g., fear of IBS symptoms) variables were significantly associated with two (SF–12 PCS, IBS-QOL) of the three indices of QOL. The strongest relationships were with IBS-QOL. Fear of GI symptoms was the most robust predictor, uniquely explaining 14% of the variance in IBS disease-specific QOL. Patients with the strongest fears about GI symptoms experienced worse QOL as measured by the IBS-QOL. The relationship between fear of GI symptoms and IBS-QOL could not be explained by the severity of IBS symptoms, a neurotic personality, sociodemographic variables, or mental distress. These data argue against the notion that the often severe loss of quality of life reported by IBS patients is simply due to their mental state or the severity of their IBS symptoms. The impact of IBS on QOL hinges to a large extent on the fear patients have about their GI symptoms and their difficulty working around these fears.

To our knowledge, this study is the first linking fear of GI symptoms to IBS-QOL. Understanding the predictors of QOL is critical to clinicians’ ability to assess accurately, understand, and respond efficiently and effectively to changes in their patients’ QOL (27). Current guidelines suggest routine (28) assessment of QOL in all patients and recommend initiating treatment when QOL is found to be diminished. Because of the global focus of generic measures of QOL, even clinicians who comply with screening recommendations using these tools are hard pressed to determine whether the nature of QOL impairment or their fluctuations are owing to the problem for which IBS patients seek treatment or coexisting medical problems common to IBS. Previous research (21) shows that medical conditions highly comorbid with IBS and not with IBS per se are significant drivers of health-related QOL impairment at least as measured by global QOL measures. An advantage of disease-specific QOL measures like the IBS-QOL is that they gauge loss of QOL due to IBS. The way individuals experience a chronic illness like IBS encompasses many different areas and is influenced by numerous factors, including the severity of IBS symptoms as well as their impact on activities of daily living, emotional unpleasantness, and meaning such as the unpredictability and uncontrollability of symptoms (29). In our subjects, patients’ fear of symptoms was a stronger predictor of IBS QOL impairment than confounding variables including IBS symptom severity. Although somewhat counterintuitive, our data echo the broader health research that has found that fear of pain is more disabling than pain itself in low back pain patients (30).

In general, the current study expands the findings of previous research conducted by Jerndal et al. (31) that has linked fear of GI symptoms as measured with the VSI to generic QOL impairment. Like Jerndal et al. (31), we found that patients who report stronger fears of GI symptoms describe worse quality of life. There are, however, important differences between our data and theirs. They found that fear of GI symptoms, together with mental well-being and demographic factors (e.g., age), accounted for a statistically significant but small (7%) proportion of the variance in the mental QOL scale of the SF-36. In contrast, our results indicate that, after holding psychological distress variables constant, fear of GI symptoms did not contribute a significant amount of unique variance to mental quality of life. In other words, the relationship between fear of GI symptoms and the mental well-being aspect of generic quality of life is largely dependent on broad-based psychological factors including personality style (neuroticism), demographics, and the overall level of psychological distress. In addition, we found that fear of GI symptoms accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in physical well-being, which Jerndal et al. (31) found unrelated to the fear of GI symptoms. We are hard pressed to provide a definitive explanation of the different patterns of data. One possibility is that our statistical approach was able to tease out the shared variance due to fear of GI symptoms, demographic variables, and global distress. Jerndal et al. (31) did not systematically assess incremental variance due to each variable. This explanation does not, however, explain our finding that fear of GI symptoms is associated with generic physical QOL. The disparity cannot be explained by differences in sample demographics, although they were sampled in different countries (USA, Sweden). Subjects in both studies were similar across multiple demographic dimensions (e.g., age, bowel type, gender). One explanation may relate to clinical differences between the samples. Jerndal et al. (31) noted that the great majority of their patients reported meal-induced symptoms in which case their impact on quality of life may be more strongly governed by peripheral (e.g., exaggerated motor or sensory component of the gastrolic reflex) vs. central factors. It is believed that more severe IBS symptoms are subject to strong central influences compared with less severe symptoms (32). Consistent with this view is the fact that our patients had stronger GI symptom fears than those in the study by Jerndal et al. (31) (mean VSI=34 vs. 44) but comparable levels of mental and physical health-related quality of life.

Our findings have implications for the clinical gastroenterologist whose treatment goals for functional GI disorder patients often focus on maximizing the quality of life in the presence of continuing symptoms. Although relief from IBS symptoms is always a primary target for medical intervention, for many IBS patients complete or most complete resolution of symptoms is not possible. Therefore, the search for dietary or pharmacological treatments to significantly improve the QOL by reducing symptom severity can be a fruitless exercise because, as our study shows, IBS symptom severity and quality of life are to an important extent conceptually and empirically distinct. Further, the impact of GI symptom fears on QOL may actually exceed that of symptoms at least among more severely affected IBS patients seen in specialty care clinics (32,33). If a major goal of treatment is to improve patients’ QOL, then optimizing treatment gains may involve the integration of symptom self-management treatments (i.e. cognitive behavioral techniques) that tackle the psychological drivers of reduced QOL. Examples of empirically validated self-management treatment include cognitive techniques (34) that teach patients information processing skills to reduce the effect of biased or maladaptive thinking patterns and behavioral (35) strategies to identify patterns of excessive avoidance that interfere with function and give him/her an opportunity to practice more adaptive ways of behaving that will enhance the health related quality of life.

Our findings also have clinical value for the many gastroenterologists for whom cognitive behavioral techniques is not widely available. For example, the notion that IBS patients’ QOL is influenced by a host of factors beyond the severity of GI symptoms can prompt gastroenterologists to develop a broader picture of the complexity of their patients’ problems, the factors that impact them, and the constraints of therapies at their disposal. This information can help physician and patients proactively establish realistic and achievable treatment goals without assuming that the route to improved QOL necessarily depends on relief from GI symptoms. For many patients, symptom relief will improve the QOL. However, patients with strong fears of GI symptoms may experience residual QOL impairment that is beyond the reach of even the most robust medical therapies. The typical clinical gastroenterologist may not have the time, expertise, or inclination to fully address patients’ illness fears, but the present results at least call attention to the fact that the problems for which patients seek care are not simply a matter of symptom relief—an idea that creates an obligation on the part of the gastroenterologist to achieve an unachievable goal and one that for a significant cohort of more severe patients seen in tertiary care clinics is likely to fall short of therapeutic objectives at the cost of their relationship with their physician and the efficiency of care they receive.

We recognize that there are several limitations inherent in this study. Because our data are cross-sectional, we do not intend to suggest that the findings demonstrate causal relationships between fear of GI symptoms and quality of life. At best, our data can be construed as suggestive of a possible causal relationship between GI symptom fears and QOL that could be confirmed through longitudinal analyses. Although our measures satisfy accepted standards for psychometric soundness, data are based on a self-report, which means they are subject to some bias and measurement error. By relying on a single item measure of GI symptom severity (14), our findings are vulnerable to a greater measurement error and reduced reliability than had we used a multi-item measure (e.g., the IBS Symptom Severity Scale). We were concerned that, for the purpose of this study, the IBS Symptom Severity Scale would have introduced its own measurement error because it conceptualizes symptom severity in terms of patient satisfaction, which is regarded by some researchers as a defining aspect of QOL (36). A reasonable concern is whether the magnitude of the observed findings is due to measurement overlap of items of the VSI and QOL that assess the same underlying concept (e.g., negative emotion). Recognizing this possibility, we statistically controlled for the possible confounding effect of potential confounds (e.g., distress, symptom severity, and so on) to determine the amount of variance in QOL due to VSI above and beyond that explained by control variables. Even when these factors were controlled, fear of GI symptoms explained a significant amount of variance in the IBS-QOL and to a lesser extent the physical aspect of QOL. The strength of the bivariate correlation between VSI and the mental aspect of QOL (Supplementary Table) fell below significant levels when demographic and clinical variables were controlled in regression analyses. It is possible that a third, unexplored variable accentuates a relationship between VSI and IBS-QOL, in which case our results should be interpreted cautiously. Confidence in study findings would be strengthened had we included behavioral measures of functional impairment and not relied solely on patients’ perceptions of their functional limitations. Because IBS patients have a tendency to appraise situations in a negative light, it is unclear to what extent the reported functional limitations that define QOL reflect “true” impairment or a test taking style that predisposes them to endorse a wide range of personal problems (negative response bias). Because of the relative demographic homogeneity of our selected sample of patients (mostly white, female, chronically ill, and educated patients seeking nondrug treatment), our results may not generalize to a broader, more diverse population. To increase the generalizability of our findings, it will be important for follow-up studies to draw from populations other than those used in the present study.

Together, this study adds to the literature that patients’ fear of GI symptoms, as measured by the VSI, has an important role in the experience of IBS and its impact on the day-to-day lives of its sufferers. Fear of GI symptoms impacts IBS-QOL above and beyond IBS symptom severity and broader emotional, sociodemographic, clinical, and personality factors. By understanding the unique role that GI symptom fears have on QOL, gastroenterologists can better understand and manage more severe IBS patients seen in specialty care settings.

Supplementary Material

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

-

Quality of life (QOL) is an essential part of health-care evaluation, particularly for benign illnesses like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) for which there is no curative therapy.

-

The clinical predictors of QOL impairment due to IBS are unclear.

-

Fear of GI symptoms is a clinically important psychological factor of IBS whose impact on QOL is unknown.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

-

Fear of GI symptoms predicts IBS-specific QOL impairment, above and beyond IBS symptom severity and broader emotional, sociodemographic, clinical, and personality factors.

-

Patients with the strongest fears about GI symptoms experienced worse QOL due to IBS.

-

Understanding the predictors of QOL can strengthen gastroenterologists’ ability to accurately assess, understand, and manage more severe IBS patients seen in specialty care settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Outcome Study Research Group (Rebecca Firth, Jason Bratton, Darren Brenner, Ann Marie Carosella, Jim Jaccard, Leonard Katz, Laurie Keefer, Susan Krasner, Sarah Quinton, Christopher Radziwon, and Michael Sitrin) for their assistance on various aspects of the research reported in this paper. We thank Dr Paul Moayyedi for the comments on a previous version of this paper and Dr James Jaccard for statistical consultation.

Financial support: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health Grant DK77738.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/ajg

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Jeffrey M. Lackner, PsyD.

Specific author contributions: Jeffrey Lackner participated in study design, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation; Gregory Gudleski was involved in data analysis and manuscript preparation; Chang-Xing Ma participated in data analysis and manuscript preparation; Akriti Dewanwala was involved in manuscript preparation and Bruce Naliboff was involved in data analysis and manuscript preparation. Jeffrey Lackner supervised the study.

Potential competing interests: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayer EA. Clinical practice. Irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1692–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0801447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy RL, Von Korff MR, Whitehead WE, et al. Costs of care for irritable bowel syndrome patients in a health maintenance organization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3122–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitehead WE, Burnett CK, Cook EW, 3rd, et al. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:2248–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02071408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lackner JM, Gudleski GD, Zack MM, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: can less be more? Psychosom Med. 2006;68:312–20. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000204897.25745.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, et al. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:654–60. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.16484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naliboff B, Lackner JM, Mayer E. Psychosocial factors in the care of patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. In: Yamada T, editor. Principles of Clinical Gastroenterology. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2008. pp. 20–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Labus JS, Bolus R, Chang L, et al. The Visceral Sensitivity Index: development and validation of a gastrointestinal symptom-specific anxiety scale. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:89–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Labus JS, Mayer EA, Chang L, et al. The central role of gastrointestinal-specific anxiety in irritable bowel syndrome: further validation of the visceral sensitivity index. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:89–8. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31802e2f24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lea R, Whorwell PJ. Quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19:643–53. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200119060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong RK, Drossman DA. Quality of life measures in irritable bowel syndrome. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;4:277–84. doi: 10.1586/egh.10.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lackner JM, Keefer L, Jaccard J, et al. The Irritable Bowel Syndrome Outcome Study (IBSOS): rationale and design of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial with 12 month follow up of self- versus clinician-administered CBT for moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:1293–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ, et al. Rome III. The functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology And Treatment: A Multinational Consensus. 2nd edn. Degnon Associates; McLean, VA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spiegel B, Strickland A, Naliboff BD, et al. Predictors of patient-assessed illness severity in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2536–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Whitehead WE, et al. Further validation of the IBS-QOL: a disease-specific quality-of-life questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:999–07. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware J, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M. SF-36 Health Survey and Interpretation. Guide QualityMetric Incoporated; Lincoln, RI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Blanchard EB. Testing the sequential model of pain processing in irritable bowel syndrome: a structural equation modeling analysis. Eur J Pain. 2005;9:207–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) 18. National Computer System; Minneapolis: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorn SD, Palsson OS, Thiwan SI, et al. Increased colonic pain sensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome is the result of an increased tendency to report pain rather than increased neurosensory sensitivity. Gut. 2007;56:1202–09. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.117390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lackner JM, Ma CX, Keefer L, et al. Type, rather than number, of mental and physical comorbidities increases the severity of symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1147–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis For The Behavioral Sciences. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edn. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patrick DL, Drossman DA, Frederick IO. A quality of life measure for persons with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-QOL): user’s manual and scoring diskette for united states version. University of Washington; Seattle, Washington: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koloski NA, Boyce PM, Jones MP, et al. What level of IBS symptoms drives impairment in health-related quality of life in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome? Are current IBS symptom thresholds clinically meaningful? Qual Life Res. 2012;21:829–36. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9985-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spielberger CD. State-Trait Personality Inventory (STPI) Mind Garden; Redwood City: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spiegel BM, Gralnek IM, Bolus R, et al. Clinical determinants of health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1773–80. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.16.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American College of Gastroenterology Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Task F Evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:S1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(02)05656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spiegel BM, Bolus R, Agarwal N, et al. Measuring symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome: development of a framework for clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1275–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crombez G, Vlaeyen JWS, PHTG Heuts et al. Pain-related fear is more disabling than pain itself: evidence on the role of pain-related fear in chronic back pain disability. Pain. 1999;80:329–39. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jerndal P, Ringstrom G, Agerforz P, et al. Gastrointestinal-specific anxiety: an important factor for severity of GI symptoms and quality of life in IBS. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:646–e179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drossman DA, Chang L, Bellamy N, et al. Severity in irritable bowel syndrome: a Rome Foundation Working Team report. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1749–59. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.201. quiz 1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, et al. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut. 2007;56:1770–98. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.119446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Krasner SS. Self-administered cognitive behavior therapy for moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome: clinical efficacy, tolerability, feasibility. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:899–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ljótsson B, Hesser H, Andersson E, et al. Mechanisms of change in an exposure-based treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81:1113–26. doi: 10.1037/a0033439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frisch MB. Quality of life therapy and assessment in health care. Clin Psychol. 1998;5:19–40. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.