Abstract

Background

Recent evidence suggests transient postoperative atrial fibrillation leads to future cardiovascular events, even in noncardiac surgery. The long-term effects of postoperative atrial fibrillation in gastrectomy patients are unknown.

Methods

The Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project State Inpatient Databases identified patients undergoing gastrectomy for malignancy between 2007 and 2010. Patients were matched by propensity scores based on various factors. Adjusted Kaplan-Meier and Cox proportional hazards models assessed the effect of postoperative atrial fibrillation on cardiovascular events.

Results

A higher incidence of cardiovascular events occurred over the 1st year in patients who developed postoperative atrial fibrillation. Cox proportional hazards regression confirmed an increased risk of cardiovascular events in postoperative atrial fibrillation patients.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that patients undergoing gastrectomy for malignancy who develop postoperative atrial fibrillation are at increased risk of cardiovascular events within 1 year. Physicians should be vigilant in assessing postoperative atrial fibrillation, given the increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Gastrectomy, Myocardial infarction, Postoperative complications, Stroke

Atrial fibrillation is the most common reported arrhythmia after surgery. Its development after cardiac surgery has been thoroughly investigated and is well documented throughout the literature. It has a reported incidence of approximately 12% to 40% after coronary artery bypass surgery and even higher after valve replacement surgery, approaching 50% to 60%.1 In this setting, the development of postoperative atrial fibrillation is associated with increased morbidity and/or mortality, longer hospital stay, and higher hospital cost. Given the different etiologic mechanisms of atrial fibrillation after cardiac and noncardiac surgery, additional investigation into the latter is warranted. For this reason, the development of postoperative atrial fibrillation after major noncardiac surgery has garnered increased attention.

The reported incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation after noncardiac surgery ranges from 3.0% to 12.3%.2 Similar to cardiac surgery, recent studies have established that the development of postoperative atrial fibrillation after noncardiac surgical procedures is associated with adverse perioperative outcomes, including an increased length of stay, increased healthcare costs, and in-hospital mortality.2 Atrial fibrillation as a chronic condition confers increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and mortality3 prompting the need to characterize the long-term effects of postoperative atrial fibrillation in this patient population.

The purpose of this study was to determine if the development of transient postoperative atrial fibrillation after gastrectomy portends higher risk of a long-term cardiovascular event. Although this has been clearly delineated in the cardiac surgery patients, there is a paucity of long-term data in noncardiac surgery patients, specifically, patients undergoing gastrectomy for malignancy. We studied patients with no prior diagnosis of atrial fibrillation and determined whether patients with postoperative atrial fibrillation were at an increased risk of developing stroke and/or acute myocardial infarction compared with a risk-matched cohort of patients who did not develop postoperative atrial fibrillation. We hypothesized that despite similar pre-existing cardiac risk factors, the cohort of patients who developed postoperative atrial fibrillation would experience a higher rate of cardiovascular events up to 1 year after their surgery.

Patients and Methods

We performed a retrospective review using the Health Care Utilization Project State Inpatient Databases, which was developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to inform health-related decisions.4 The Health Care Utilization Project State Inpatient Databases include deidentified, protected, and patient discharge records for all payers, with each state inpatient database unique to its individual state. We used the state inpatient database for Florida and California, including patient data encompassing years 2006 to 2011. As of 2007, diagnoses could be labeled as present on admission, allowing pre-existing conditions to be identified, and differentiated from those arising during the hospitalization.5 To follow patients longitudinally over multiple hospital admissions, a unique linkage variable is assigned to individual patients within each state inpatient database, allowing for identification of preoperative medical conditions, and complications after the initial surgical hospitalization.6 Patients of interest were identified using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) procedure and diagnosis codes.

Patients were included if they were 18 years of age or older and underwent partial or total gastrectomy (ICD-9: 43.5, 43.6, 43.7, 43.8×, 43.9×) for a diagnosis of malignancy (pancreatic (157.××), esophageal (150.××), or gastric (151.××) carcinoma) in either the state of California or Florida between the years of 2007 to 2010. Data from years 2006 and 2011 were included to provide at least 1 year of inpatient hospitalization records for identification of preoperative medical comorbidities, as well as postoperative admissions and complications, respectively.

The diagnosis of atrial fibrillation was identified using ICD-9 codes (427.3×) as previously described6,7 and further classified as pre-existing atrial fibrillation vs postoperative atrial fibrillation using data from prior inpatient admissions and the presence-on-admission indicator. Patient baseline comorbidities were assessed via linked hospital admission records that occurred before the surgical admission, to identify diagnoses of atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease or angina, and/or cerebral vascular accident, or transient ischemic attack. Additional patient clinical and demographic variables available in the Health Care Utilization Project State Inpatient Databases database were used for analysis, including age at surgery, race, primary insurance type, and chronic conditions of chronic renal failure, obesity, congestive heart failure, valvular heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus.

The primary outcome of interest was the occurrence of a cardiovascular event diagnosed after gastrectomy within 1 year postoperatively. This composite endpoint of a cardiovascular event was the occurrence of either of 2 established cardiovascular sequelae of atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, or cerebrovascular accident.

Patients were excluded if they had a preoperative diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, history of cerebrovascular accident/transient ischemic attack, or history of myocardial infarction/coronary artery disease. Thus, our final cohort comprised all patients who underwent partial or total gastrectomy for malignancy, in Florida or California between 2007 and 2010, without a prior diagnosis of myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular accident, and/or transient ischemic attack, or a pre-existing diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.

Propensity score matching was performed to control for patient characteristics and medical comorbidities that may contribute to the composite endpoint. Matching was performed based on patient age as a continuous variable, and categorical variables of sex, race, primary insurance provider, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, congestive heart failure, valvular heart disease, coronary artery disease, chronic renal failure, and peripheral vascular disease. Matching was performed in a one-to-one fashion, caliper of .1, and without replacement.7 Adequate balance was determined by improvement of standardized percent bias of covariates to 10% or less.8

Statistical analysis included independent t tests and Chi-square tests to compare baseline patient characteristics in the unmatched postoperative atrial fibrillation/no postoperative atrial fibrillation cohorts. After matching, paired t tests and McNemar's test were used to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively. An adjusted Kaplan-Meier time-to-event analysis on the matched cohort was performed to assess the cumulative incidence of cardiovascular event over the 1st year postoperatively. Right censoring occurred at the date of last follow-up or date of death, and at the time of readmission with a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation to assess only patients who developed transient postoperative atrial fibrillation. This allowed transient postoperative atrial fibrillation patients to be assessed, as opposed to those with persistent atrial fibrillation after surgery. An adjusted log-rank test, accounting for the matched pair, was used to compare matched postoperative atrial fibrillation and nonpostoperative atrial fibrillation patient cohorts.9 Finally, a stratified Cox proportional hazards regression model was fit on the matched sample to estimate the contribution of postoperative atrial fibrillation on the risk of cardiovascular event.

Results

Between 2007 and 2010, 5,065 patients 18 years of age or older underwent gastrectomy for malignancy in California and Florida. New-onset postoperative atrial fibrillation occurred in 408 (8.1%) of patients without a prior diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. The remaining 4,637 patients did not develop postoperative atrial fibrillation. Baseline characteristics for the study population are reported in Table 1. Patients who experienced postoperative atrial fibrillation were more likely older, Caucasian, male, and carry Medicare as their primary insurance provider. These patients were also more likely to have medical comorbidites of obesity, hypertension, congestive heart failure, valvular heart disease, chronic renal failure, and peripheral vascular disease. In addition, they were also likely to have a higher CHA2DS2-VASc score (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics by atrial fibrillation status postoperatively.

| Postoperative atrial fibrillation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| No n = 4,657 | Yes n = 408 | ||

|

|

|

||

| n (n%) | n (n%) | P value | |

| Age (y), mean (SD) | 65.0 (13.1) | 72.6 (9.7) | <.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 2,714 (58.3%) | 294 (72.1%) | <.001 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 1,892 (40.6%) | 269 (65.9%) | <.001 |

| Primary Insurance provider | |||

| Medicare | 2,224 (47.8%) | 287 (70.3%) | <.001 |

| Medicaid | 579 (12.4%) | 26 (6.4%) | |

| Private insurance | 1,620 (34.8%) | 87 (21.3%) | |

| Obese | |||

| Yes | 295 (6.3%) | 44 (10.8%) | .001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||

| Yes | 976 (21.0%) | 93 (22.8%) | .4 |

| Hypertension | |||

| Yes | 2,306 (49.5%) | 249 (61.0%) | <.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | |||

| Yes | 160 (3.4%) | 62 (15.2%) | <.001 |

| Valvular heart disorder | |||

| Yes | 135 (2.9%) | 26 (6.4%) | <.001 |

| Chronic renal failure | |||

| Yes | 197 (4.2%) | 43 (10.5%) | <.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | |||

| Yes | 135 (2.9%) | 26 (6.4%) | <.001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 5.0 (3.1) | 5.3 (3.1) | .1 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score, mean (SD) | 2.0 (1.4) | 2.6 (1.3) | <.001 |

Given HCUP restrictions on reporting tabular data when the patient number is less than 10, data for race are only reported as Caucasian, and primary insurance type is reported as Medicare/Medicare and private insurance.

SD = standard deviation.

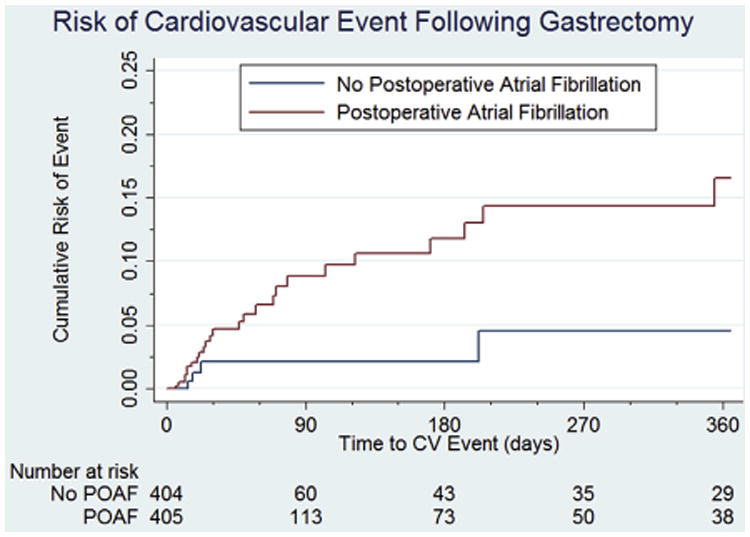

Propensity score matching was conducted with adequate balance between postoperative atrial fibrillation and non-postoperative atrial fibrillation populations (standardized percent bias <10% for all covariates). All pre-existing differences between the groups were accounted for after matching. In the matched cohort, a significantly higher cumulative incidence of cardiovascular events occurred over the 1st year in patients who developed postoperative atrial fibrillation (16.7% vs 4.5%; Fig. 1). Cox proportional hazards regression confirmed an increased risk of cardiovascular events in postoperative atrial fibrillation patients (HR = 3.7, P =.046). When evaluating our matched cohorts at 3 -month intervals; patients that developed postoperative atrial fibrillation were at least 3 times more likely to experience a cardiovascular event at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months, respectively.

Figure 1.

Adjusted Kaplan-Meier estimate of cardiovascular events after gastrectomy.

Comments

In a large cohort of patients who underwent gastrectomy for malignancy, the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation was 8.1%. After matching for cardiovascular comorbidities, patients who developed transient postoperative atrial fibrillation were found to have a significantly increased risk of myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident over the 1st postoperative year. This finding supports our hypothesis that patients who develop transient postoperative atrial fibrillation are at an increased risk for cardiovascular comorbidity after gastrectomy.

Although there is increasing literature describing the development of postoperative atrial fibrillation after noncardiac surgery, this study is unique in that it evaluates the long-term sequelae these patients experience, despite only transiently developing the arrhythmia in the perioperative period; a relatively new concept. Although previous studies focused on large cohorts of noncardiac surgery patients, we instead elected to evaluate a subset of noncardiac surgery patients. Patients undergoing gastrectomy were selected because, anecdotally, at our institution they appeared to experience postoperative atrial fibrillation at a greater frequency than other surgical patients. However, when comparing our incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation with other noncardiac surgery cohorts, our findings are consistent with the range currently reported.

To date, there has been no large prospective or retrospective study that has evaluated postoperative atrial fibrillation in gastrectomy patients, making it difficult to draw any direct comparisons with our results. However, in a large retrospective study by Bhave, et al,2 they evaluated all patients that underwent major noncardiac surgery at 375 US hospitals over a 1 -year period. The reported incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation was 3.0%. Although this incidence is less than described in our study; similar to our findings, they identified advancing age, hypertension, and congestive heart failure as risk factors for the development of postoperative atrial fibrillation. They also found that patients developing postoperative atrial fibrillation had significantly higher mortality, along with longer and more costly hospital stays. Another study by Blackwell, et al,10 found that patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer, who developed postoperative atrial fibrillation were at increased risk for cardiovascular events within 1 year of their surgery, which parallels our findings.

In another study by Gialdini et al,11 they investigated the long-term risk of stroke in surgical patients who developed transient postoperative atrial fibrillation. In that study, all surgical patients in California between 2007 and 2010 were included. They excluded patients with any atrial fibrillation diagnoses recorded during encounters before the index hospitalization for surgery. They found a significant association between perioperative atrial fibrillation and long-term risk of ischemic stroke, even when controlling for potential confounders. In fact, the strength of this association was significantly greater for postoperative atrial fibrillation that occurred in the setting of noncardiac surgery, rather than cardiac surgery. This could potentially be due to the use of prophylactic medications administered preceding cardiac surgery to prevent the development of postoperative atrial fibrillation. This could also be due to the etiology of the postoperative atrial fibrillation, given the direct cardiac manipulation inherent to cardiac surgery, compared with the physiologic changes, fluid shifts, or possible unmasking of underlying/untreated cardiac disease thought to contribute to postoperative atrial fibrillation after noncardiac surgical procedures.

Limitations in our analysis warrant discussion. First, the duration of postoperative atrial fibrillation at the time of diagnosis is unknown. It is possible that brief, self-terminating episodes of postoperative atrial fibrillation are not documented, thus both underestimating the overall incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation in this group, and selecting for patients with more clinically significant diagnoses. In addition, we did not evaluate how each episode of atrial fibrillation was treated. Likely, a patient that was symptomatic and required cardioversion would be at greater risk for a cardiac event than the patient that only required rate control medication. Similarly, it would be useful to know what medication regimen these patients were discharged home, and if appropriate follow up was arranged.

A known limitation of this database is its lack of outpatient data. The number of these episodes that result in persistent atrial fibrillation would best be captured by outpatient data with ambulatory monitoring. To limit our analysis to patients who developed transient postoperative atrial fibrillation, as has been reported previously,6 censoring was performed at the time of readmission with a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. Even by excluding patients in this fashion, a significant increase in cardiovascular events was demonstrated. Presumably, a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, if present, would be clinically relevant and recorded at readmission for a cardiovascular event, suggesting our findings are accurate.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that patients undergoing gastrectomy for malignancy who develop transient postoperative atrial fibrillation are at a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events within 1 year postoperatively. Physicians should be vigilant in assessing postoperative atrial fibrillation, even when transient, given the increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity. A better understanding of the etiology, prevention, and management of postoperative atrial fibrillation in noncardiac surgical patients is a topic which warrants further evaluation.

Acknowledgments

No industry sponsorship of current work.

References

- 1.Andrews TC, Reimold SC, Berlin JA, et al. Prevention of supraventricular arrhythmias after coronary artery bypass surgery. A meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Circulation. 1991;84:236–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhave PD, Goldman LE, Vittinghoff E, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes associated with postoperative atrial fibrillation after major noncardiac surgery. Am Heart J. 2012;164:918–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soliman EZ, Safford MM, Muntner P, et al. Atrial fibrillation and the risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:107–14. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. [Accessed January 13, 2015]; Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov.

- 5.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP methods series: the case for the POA indicator. [Accessed January 13, 2015]; Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/2011_05.pdf.

- 6.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP methods series: methodological issues when studying readmissions and revisits using hospital administrative data. [Accessed January 13, 2015]; Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/2011_01.pdf.

- 7.Leuven E, Sianesi B. PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. [Accessed January 13, 2015];2003 Available at: http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s432001.html.

- 8.Harder VS, Stuart EA, Anthony JC. Propensity score techniques and the assessment of measured covariate balance to test causal associations in psychological research. Psychol Methods. 2010;15:234–49. doi: 10.1037/a0019623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Austin PC. A tutorial and case study in propensity score analysis: an application to estimating the effect of in-hospital smoking cessation counseling on mortality. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46:119–51. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.540480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackwell RH, Ellimootil C, Bajic P, et al. New onset post-operative atrial fibrillation predicts long-term cardiovascular events following radical cystectomy. J Urol. 2015;194:944–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.03.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gialdini G, Nearing K, Bhave PD, et al. Perioperative atrial fibrillation and the long-term risk of ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2014;312:616–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]