Abstract

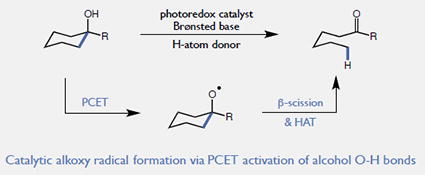

We report a new photocatalytic protocol for the redox-neutral isomerization of cyclic alcohols to linear ketones via C-C bond scission. Mechanistic studies demonstrate that key alkoxy radical intermediates in this reaction are generated via the direct homolytic activation of alcohol O-H bonds in an unusual intramolecular PCET process, wherein the electron travels to a proximal radical cation in concert with proton transfer to a weak Brønsted base. Effective bond strength considerations are shown to accurately forecast the feasibility of alkoxy radical generation with a given oxidant/base pair.

Graphical abstract

Alkoxy radicals are versatile synthetic intermediates, enabling both H-atom abstraction from unfunctionalized alkanes and the cleavage of adjacent C-C bonds via β-scission.1,2 In principle, alkoxy radicals can be accessed via direct hydrogen atom transfer from the hydroxyl groups of aliphatic alcohols. However, the pronounced homolytic stability of these bonds (OH BDFEs ~ 105 kcal/mol) presents a challenge to the design of such schemes, and general catalytic methods for the selective homolysis of alcohol O-H bonds are currently unknown.3

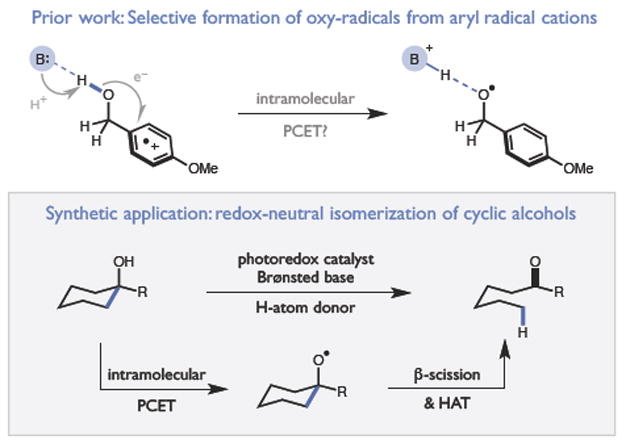

Our group has recently become interested in an alternative approach to the homolytic activation of strong bonds based on proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET).4 In oxidative PCET reactions, a one-electron oxidant and a Brønsted base function together to remove a proton and an electron from a substrate in a concerted elementary step. As the oxidant and base can be varied independently, the thermochemistry of PCET processes can be rationally modulated over a wide range of energies to facilitate the homolytic cleavage of strong bonds that cannot be activated using conventional H-atom transfer catalysts.5 With respect to alcohol PCET reactivity, we were intrigued by elegant spectroscopic studies from Bacchioici, Bietti, and Steenken, who demonstrated that the O-H bonds of alcohols adjacent to arene radical cations undergo selective deprotonation at near diffusion-controlled rates with modest driving forces to furnish discrete alkoxy radical intermediates (Figure 1).6 While the precise mechanism of the intramolecular charge transfer event was not delineated in these studies, the authors suggested that concerted PCET may play a role.

Figure 1.

Catalytic ring opening of cyclic alcohols via PCET

Here we provide support for this hypothesis in the context of a novel catalytic method for the isomerization of cyclic aryl alkanols to linear ketones. This redox-neutral process is mediated by a key alkoxy radical intermediate that is generated through an unusual intramolecular PCET event between a tertiary hydroxyl group and a proximal radical cation in the presence of a weak Brønsted base (Figure 1). Notably, this protocol allows alkoxy generation from alcohols that are spatially removed from the arene radical cation, providing a means to selectively cleave distal C-C bonds. This reaction represents a rare example of catalytic alcohol O-H homolysis,7 and may provide new opportunities for the strategic use of C-C bond cleavage transforms in synthesis. The design, scope, and preliminary mechanistic evaluation of this process are presented herein.

Reaction Design and Optimization

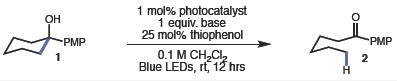

Our synthetic studies examined the catalytic isomerization of alcohol 1 to ketone 2 using a ternary catalyst system comprised of a visible light photoredox catalyst, a Brønsted base, and a thiol hydrogen atom donor (Figure 2). We anticipated a catalytic cycle wherein oxidation of the electron-rich arene by the excited state of the redox catalyst would furnish a transient radical cation. An intramolecular PCET reaction would follow (vide infra), in which deprotonation of the hydroxyl group by the Brønsted base catalyst occurs in concert with one-electron reduction of the radical cation to provide the key alkoxy radical intermediate. It is well known that alkoxy radicals substantially weaken adjacent C-C bonds,8 enabling favorable ring opening to generate an aryl ketone and a distal alkyl radical. A catalytic H-atom donor, such as thiophenol, could then intercept and reduce the nascent alkyl radical,9,10 affording a linear ketone product. Reduction of the resulting thiyl by the reduced state of the photocatalyst and protonation by the conjugate acid of the Brønsted base would complete the catalytic cycle.

Figure 2.

Proposed catalytic cycle

Gratifyingly, we found that when 1 (Ep/2 = 1.22 V vs. Fc/Fc+) was exposed to sufficiently oxidizing Ir photocatalysts under blue light irradiation in the presence of thiophenol and a number of weak Brønsted bases, ring-opened product 2 was observed (entries 1–7). The most oxidizing catalyst evaluated in the series, [Ir(dF(CF3)ppy)2(5,5’d(CF3)bpy)](PF6) (C) (*E1/2 = 1.30 V vs. Fc/Fc+), proved optimal, while collidine was found to be the most efficient proton acceptor (entry 3). Up to 91% yield of 2 was observed when 3 equivalents of collidine were used, however lower base loadings were also effective (entries 3, 8, 9). Control experiments run in the absence of light, photocatalyst or Brønsted base provided essentially no product. Reactions excluding thiophenol produced 2 in 50% yield, presumably due to HAT from the benzylic C-H bonds of collidine to the alkyl radical. The use of CD2Cl2 solvent did not result in deuterium incorporation.

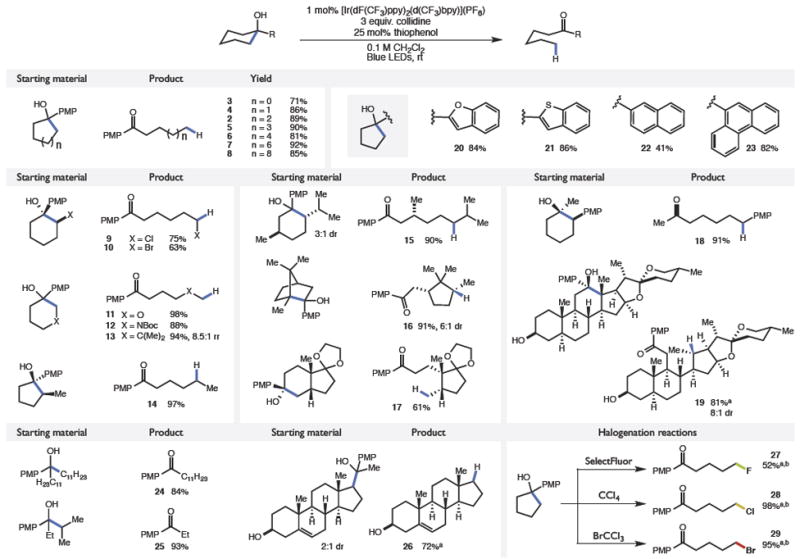

Substrate Scope

With these optimized conditions, we evaluated the scope of the isomerization process. On preparative scale the model reaction was successful, furnishing ketone 2 in 89% yield. We also observed that numerous other ring sizes could be accommodated (3–8) suggesting that ring strain is not a pre-requisite for efficient bond scission.11 In unsymmetrical ring systems, high selectivities were observed for bond scissions that eject the more stable radical intermediate (9–12, 14). Moreover, this selectivity was also manifested in β-substituted substrates such as those leading to 13, which demonstrated 8.5:1 selectivity for cleavage to form a neopentyl radical. Importantly, successful cleavage to form 18 demonstrates the electron-rich PMP group need not reside on the same carbon as the alcohol. Additionally, this ring-opening strategy can be applied towards more complex cyclic and bicyclic structures such as 15, 16, and 17 without compromising proximal stereocenters. Complex natural product-derived substrates such as hecogenin analog 19 were also successful. Notably, while the substrate leading to 19 exhibits two distinct hydroxyl groups, β-scission occurs exclusively on the alcohol proximal to the PMP-group.

In addition to p-methoxyphenyl, a number of arenes can be accommodated as the initial site of oxidation, including benzofuran (20), benzothiophene (21), naphthyl (22), and phenanthryl (23). Furthermore, the reaction conditions can be used to extrude free alkyl radical fragments from linear alcohols (24–26). Again, high selectivities were observed for bond cleavage to form the more stabilized radical leaving group. Lastly, we found that fluorine-, chlorine- and bromine-atom donors could all be readily incorporated into the catalytic cycle in place of the thiol catalyst to produce distally halogenated ketones 27, 28, and 29. With respect to limitations, this protocol is unsuccessful with arenes that cannot be oxidized by C (such as the simple phenyl analog of 1), as well as non-aryl tertiary alkyl carbinols. Efforts to address these constraints are ongoing.

Mechanistic Studies

In addition to these synthetic studies, we have also examined the initial steps of the proposed catalytic cycle. With respect to the first electron transfer event, Stern-Volmer analysis revealed that the excited state of iridium catalyst C is efficiently quenched by admixtures of collidine and the cyclooctyl analog of 1 in CH2Cl2 at rt. Independently varying the concentrations of these two components revealed a first order dependence on the concentration of alcohol and a zero order dependence on the concentration of collidine, suggesting that direct arene oxidation, rather than O-H PCET, is the dominant mechanism of excited state charge transfer. Based on potential difference this excited state ET reaction is exergonic by ~ 90 mV.

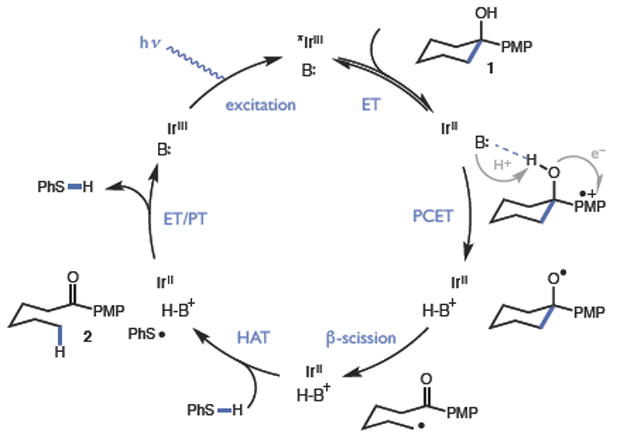

To determine whether the subsequent charge transfer event between the arene radical cation and the O-H bond proceeds via stepwise PT/ET or concerted PCET, we evaluated the C-C cleavage reactivity of a series of substrates with an increasing number of methylene groups between the alcohol and the arene (Figure 3). This line of inquiry was guided by the assumption that the pKa of the scissile O-H bond should rapidly increase as a function of increasing distance from the radical cation, ultimately approaching that of an isolated tertiary alkanol (~ 40 in MeCN).5c In this limiting regime, deprotonation of the hydroxyl by collidine (pKa = 15.0 in MeCN)12 would be prohibitively endergonic (ΔG° ~ +34 kcal/mol) and unable to compete with charge recombination between the arene radical cation and the reduced Ir(II) state of the photocatalyst (ΔG° = −53 kcal/mol). Conversely, the thermochemistry of concerted PCET is expected to be modestly ex-ergonic (ΔG° ~ −1 kcal/mol) virtually irrespective of the ET distance.13 Experimentally, we found that C-C cleavage reactivity was indeed observed for substrates with up to four carbon atoms separating the arene and the alcohol – a remarkable outcome that is strongly suggestive of a concerted PCET mechanism.14 In addition to their mechanistic significance, these observations suggest interesting synthetic possibilities wherein oxidation at a remote site might be relayed to a specific hydroxyl group to induce selective cleavage of a distal C-C bond.

Figure 3.

Distal C-C bonds cleaved via long-range PCET

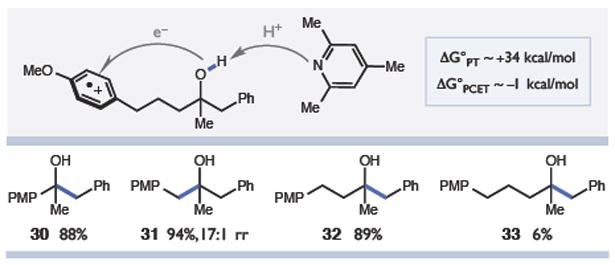

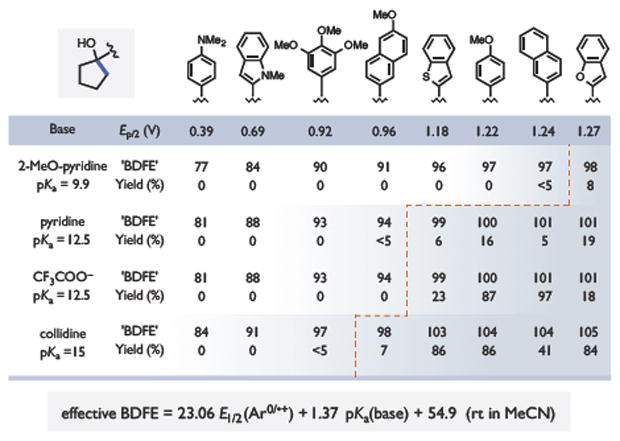

Based on the observations above, we also sought to evaluate how reaction outcomes varied as a function of the thermodynamic driving force for the PCET event. As noted by Mayer, the capacity of any given oxidant/base pair to function as a formal H• acceptor can be quantified as an effective bond strength (‘BDFE’) derived from the pKa and reduction potential of its constituents (see equation in Figure 4).4b In our proposed mechanism, the relevant reduction potential is that of the arene radical cation that serves as an internal oxidant. To examine the relationship between effective BDFEs and reaction outcomes, we evaluated the isomerization reaction for eight substrates bearing different arenes with oxidation potentials spanning a range of ~ 900 mV. In conjunction with four different Brønsted bases, we were able to generate a set of 32 unique combinations with effective bond strengths ranging from 77 to 105 kcal/mol. Remarkably, in all cases wherein the effective BDFE of the oxidant/base combination approaches or exceeds that of the substrate (O-H BDFE ~ 102 kcal/mol),13 the reactions were successful and generated the expected ketone products. However, all combinations with effective BDFEs less than ~ 98 kcal/mol furnished little or no ring-opened products. These energetic correlations provide further support for the notion that simple thermodynamic considerations can be used to accurately forecast the feasibility of a given PCET process.15

Figure 4.

Effective BDFE correlations with reactivity

In conclusion, we have developed a new catalytic method for the redox-neutral isomerization of cyclic alkanols to linear ketones that proceeds via C-C bond β-scission. Moreover, this work represents a rare example of alkoxy radical generation via multisite PCET activation of alcohol O-H bonds. Efforts to expand these results to include simple alcohol substrates are currently ongoing.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Reaction optimization

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Entry | Photocatalyst | Base | Yield (%) |

| 1 | [Ir(dF(CF3)ppy)2(dtbbpy)](PF6) (A) | collidine | 0 |

| 2 | [Ir(dF(CF3)ppy)2(bpy)](PF6) (B) | collidine | 9 |

| 3 | [Ir(dF(CF3)ppy)2(5,5'd(CF3)bpy)](PF6) (C) | collidine | 79 |

| 4 | [Ir(dF(CF3)ppy)2(5,5'd(CF3)bpy)](PF6) (C) | pyridine | 6 |

| 5 | [Ir(dF(CF3)ppy)2(5,5'd(CF3)bpy)](PF6) (C) | TBA+ (PhO)2POO− | 4 |

| 6 | [Ir(dF(CF3)ppy)2(5,5'd(CF3)bpy)](PF6) (C) | TBA+ CF3COO− | 48 |

| 7 | [Ir(dF(CF3)ppy)2(5,5'd(CF3)bpy)](PF6) (C) | TBA+ PhCOO− | 8 |

| 8 | [Ir(dF(CF3)ppy)2(5,5'd(CF3)bpy)](PF6) (C) | collidine (2 eq) | 83 |

| 9 | [Ir(dF(CF3)ppy)2(5,5'd(CF3)bpy)](PF6) (C) | collidine (3 eq) | 91 |

Optimization reactions were performed on a 0.05 mmol scale. Yields determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixtures. Structures and potential data for all photocatalysts are included in the SI.

Table 2.

Substrate scope

|

Reactions run on 1.0 mmol scale. Reported yields are for isolated and purified material and are the average of two experiments. Diastereomeric ratios were determined by 1H NMR or GC analysis of the crude reaction mixtures.

0.5 mmol scale.

For experimental details of halogenations, see SI.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the NIH (R01 GM113105). R.R.K is a fellow of the A. P. Sloan Foundation. We thank Istvan Pelczer for help with NMR experiments and Laura Wilson for help with sample purification.

Footnotes

Experimental procedures and characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Majetich G, Wheless K. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:7095.Feray L, Kuznetsov N, Renaud P. In: Radicals in Organic Synthesis. Renaud P, Sibi MP, editors. Vol. 2. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2001. pp. 246–278.Suárez E, Rodriguez MS. In: Radicals in Organic Synthesis. Renaud P, Sibi MP, editors. Vol. 2. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2001. pp. 440–454.

- 2.Barton DHR, Beaton JM, Geller LE, Pechet MM. J Am Chem Soc. 1960;82:2640.Kochi JK. J Am Chem Soc. 1962;84:1193.Walling C, Wagner PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1964;86:3368.Avila DV, Brown CE, Ingold KU, Lusztyk JJ. Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:466.Weber M, Fischer H. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:7381.Salamone M, Bietti M. Synlett. 2014;25:1803.

- 3.For a stoichiometric example, see: Wang D, Farquhar ER, Stubna A, Munck E, Que L. Nat Chem. 2009;1:145. doi: 10.1038/nchem.162.Wang D, Que L. Chem Comm. 2013;49:10682. doi: 10.1039/c3cc46391e.

- 4.Reece SY, Nocera DG. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:673. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.080207.092132.Warren JJ, Tronic TA, Mayer JM. Chem Rev. 2010;110:6961. doi: 10.1021/cr100085k.Weinberg DR, Gagliardi CJ, Hull JF, Murphy CF, Kent CA, Westlake BC, Paul A, Ess DH, McCafferty DG, Meyer TJ. Chem Rev. 2012;112:4016. doi: 10.1021/cr200177j.

- 5.Choi GJ, Knowles RR. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:9226. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b05377.Tarantino KT, Liu P, Knowles RR. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:10022. doi: 10.1021/ja404342j.Waidmann CR, Miller AJM, Ng CA, Scheuermann ML, Porter TR, Tronic TA, Mayer JA. Energy Environ Sci. 2012;5:7771.

- 6.Baciocchi E, Bietti M, Steenken S. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:4078.Baciocchi E, Bietti M, Lanzalunga O, Steenken S. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:11516.Baciocchi E, Bietti M, Lanzalunga O. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:243. doi: 10.1021/ar980014y.

- 7.Select examples of β-scission of cyclic alcohols with stoichiometric oxidants: Chiba S, Cao Z, Bialy SAAE, Narasaka K. Chem Lett. 2006;35:18.Zhao H, Fan X, Yu J, Zhu C. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:3490. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00939.Ren S, Feng C, Loh TP. Org Biomol Chem. 2015;13:5105. doi: 10.1039/c5ob00632e.Wang S, Guo LN, Wang H, Duan XH. Org Lett. 2015;17:4798. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02353.Jia K, Zhang F, Huang H, Chen Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:1514. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b13066.

- 8.DFT predicts the BDE of the scissile C-C bond in the alkoxy radical of 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)propan-2-ol to be ~0 kcal/mol. See SI for details.

- 9.Nguyen TM, Nicewicz DA. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9588. doi: 10.1021/ja4031616.Miller DC, Choi GJ, Orbe HS, Knowles RR. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:13492. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b09671.

- 10.For a discussion of the compatibility of thiols with strong excited state oxidants, see: Romero NA, Nicewicz DA. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:17024. doi: 10.1021/ja506228u.

- 11.For β-scission rates as a function of ring size, see: Bietti M, Salamone M. J Org Chem. 2005;70:1417. doi: 10.1021/jo048026m.

- 12.Kaljurand I, Kutt A, Soovali L, Rodina T, Maemets V, Leito I, Koppel IA. J Org Chem. 2005;70:1019. doi: 10.1021/jo048252w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.See SI for details

- 14.β-scission of 31 has been studied: Baciocchi E, Bietti M, Manduchi L, Steenken S. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:6624.

- 15.Nguyen LQ, Knowles RR. ACS Cat. 2016;6:2894.Yayla HG, Knowles RR. Synlett. 2014;20:2819.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.