Abstract

Background

Exposure to isoflurane increases apoptosis among postnatally-generated hippocampal dentate granule cells. These neurons play important roles in cognition and behavior, so their permanent loss could explain deficits following surgical procedures.

Methods

To determine whether developmental anesthesia exposure leads to persistent deficits in granule cell numbers, a genetic fate-mapping approach to label a cohort of postnatally-generated granule cells in Gli1-CreERT2::GFP bitransgenic mice was utilized. GFP-expression was induced on postnatal day seven (P7) to fate-map progenitor cells, and mice were exposed to six hours of 1.5% isoflurane or room air two weeks later (P21). Brain structure was assessed immediately after anesthesia exposure (n=7 controls, 8 anesthesia), or following a 60-day recovery (n's=8 and 8). A final group of C57BL/6 mice was exposed to isoflurane at P21 and examined using neurogenesis and cell death markers following a 14-day recovery (n=10 controls, 16 anesthesia).

Results

Isoflurane significantly increased apoptosis immediately after exposure, leading to cell death among 11% of GFP-labeled cells. 60 days following isoflurane exposure, the number of GFP-expressing granule cells was indistinguishable from control animals. Rates of neurogenesis were equivalent among groups at both two weeks and two months after treatment.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that the dentate gyrus can restore normal neuron numbers following a single, developmental exposure to isoflurane. Our results do not preclude the possibility that the affected population may exhibit more subtle structural or functional deficits. Nonetheless, the dentate appears to exhibit greater resiliency relative to non-neurogenic brain regions, which exhibit permanent neuron loss following isoflurane exposure.

Introduction

All commonly used anesthetics increase brain cell death in developing animals.1 An analogous phenomenon has been described for anticonvulsant medications, many of which have similar mechanisms of action to anesthetics.2,3 Prospective clinical studies are ongoing to establish whether anesthesia exposure in childhood is associated with long-term cognitive deficits. Early results from the general anesthesia and awake-regional anesthesia in infancy (GAS) study are encouraging, providing no evidence of neurocognitive deficits in children at two years following <1 hour exposure in infancy.4 This is consistent with animal studies, which find little evidence for structural brain abnormalities following brief exposures. Retrospective clinical studies of longer or repeat exposures, on the other hand, have linked childhood anesthesia to subsequent language impairment, cognitive abnormalities and learning disabilities,5-8 although not all groups have found deficits.9,10 Prospective clinical studies will require several years to complete and are unlikely to cover all clinical scenarios, especially for prolonged exposure times. There is significant concern, therefore, that anesthesia exposure early in life may have long-term deleterious effects on the developing brain.

Increased apoptotic cell death has been one of the most dramatic findings among anesthesia-exposed animals. Establishing whether there is a net loss of cells persisting into adulthood, however, has been challenging for three main reasons: Firstly, the most vulnerable period for anesthetic exposure coincides with the period of naturally-occurring apoptosis – a normal process which “prunes” excess neurons. Accelerated loss of neurons fated to die anyway could produce the well-characterized increase in apoptosis, while still having no effect on final neuron numbers. By contrast, loss of neurons that should have survived to adulthood will reduce neuronal density in the mature brain. Traditional cell death markers cannot distinguish between these possibilities, and cell counts in adult animals have returned conflicting results. 11,12 A second complicating factor is the potential for compensatory neurogenesis among certain neuronal populations sensitive to anesthesia-induced death. Specifically, we and others have recently demonstrated that hippocampal dentate granule cells are especially vulnerable to anesthesia-induced neurotoxicity in 21 day-old (P21) mice,13,14,15 a brain maturational stage comparable to human infants.16 Granule cells, however, are produced throughout life in animals and humans, 17 so it is conceivable that the dentate could regenerate lost cells. Finally, within the dentate there is the potential for loss of the progenitor cells responsible for adult neurogenesis. Progenitor cell loss would eliminate future generations of daughter cells, compounding neuronal loss well beyond the number of initially affected cells. The effect of such a loss is poorly captured by traditional approaches.

Given the importance of hippocampal granule cells for cognition, 18-20 we queried whether anesthesia produces a net deficit in their numbers. We genetically fate-mapped a cohort of granule cell progenitors in developing mice by inducing persistent green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression among the population. Since all daughter cells of labelled progenitor cells express GFP, the net number of neurons produced can be counted. Changes in apoptosis or neurogenesis rates occurring over days, weeks or even months, therefore, are revealed by the number of GFP-expressing cells.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All procedures conformed to National Institute of Health and Cincinnati's Children Hospital Medical Center guidelines (Cincinnati, Ohio, USA) for the care and use of animals. Sample sizes were estimated based on past experience with similar anatomical measures.21 To generate animals for the present study, hemizygous Gli1-CreERT2 mice,22,23 expressing a conditional, tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre-recombinase, were crossed to homozygous CAG-CAT-EGFP (GFP) reporter mice.24 A total of 36 Gli1-CreERT2::GFP bitransgenic offspring from this cross were used for experiments. Mice were housed on a 14/10 (light/dark) cycle with access to food and water ad libitum. All animals were maintained on a C57BL/6 background.

Bi-transgenic Gli1-CreERT2::GFP offspring were treated with 250 mg/kg tamoxifen (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) on P7 to activate cre-recombinase in Gli1-expressing neural progenitor cells,23,25 leading to the persistent expression of GFP in these cells and all their progeny. On P21, animals were randomized to fasting in room air or 1.5% isoflurane (Isothesia, Henry Schein Animal Health, Dublin, OH) in 30% oxygen for six hours. Inspired anesthetic and oxygen concentrations were monitored using a gas analyzer (RGM 5250; Datex-Ohmeda, Louisville, CO). Animals were housed in padded acrylic containers inside incubators warmed to 34°C during the six hours. Rectal temperature measurements in a separate group of five mice revealed a gradual increase in temperature over the six hour exposure, from 35.6±0.3°C at 30 minutes to 38.0±0.0°C at six hours. These temperatures appear to be in the normal range.26-28 Mice were killed either immediately after treatment, or 60 days after treatment, generating four study groups: (1) P21 control: three-week-old mice exposed to room air and perfused immediately (n=7 [male=3, female=4]; (2) P21 anesthesia: three-week-old mice exposed to isoflurane and perfused immediately (n=8 [male=6, female=2]; (3) P81 control: mice exposed to room air on P21 and perfused 60 days later (n=8 [male=3, female=5]) and (4) P21 anesthesia+60 days, mice exposed to isoflurane on P21 and perfused 60 days later (n=8 [male=4, female=4]). Group numbers do not include three animals that died during anesthesia exposure, and two P81 control mice that died during the two-month recovery period. For perfusions, mice were euthanized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (20 mg/kg), acepromazine (0.5 mg/kg) and xylazine (1 mg/kg) (triple cocktail prepared by the CCHMC vivarium, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA), then transcardially perfused with 0.1M phosphate buffered saline (PBS)+1U/ml heparin followed by 4% paraformaldehyde with 5% sucrose and 5% glycerol in PBS, pH 7.4. Brains were removed, post-fixed overnight in the same fixative, cryoprotected in an ascending sucrose series (10, 20 and 30%) in PBS and snap-frozen in 2-methyl-pentane at −25°C. Brains were sectioned sagittally at 60 μm on a cryostat and sections were mounted to gelatin-coated slides and stored at −80°C.

BrdU Pulse-Chase Experiments

To determine whether anesthesia exposure altered cell proliferation, a group of C57BL/6 mice was exposed to isoflurane or room air on P21, in identical fashion to other animals in this study. Following anesthesia exposure, animals received BrdU (100 mg/Kg/dose; Sigma) on days two, four, six, eight, and ten after treatment, for a total of five doses. Animals were euthanized and perfused two weeks after anesthesia exposure, on P35. A total of 11 animals were exposed to room air and 19 to isoflurane. There was no mortality in either group, however, 1 control and 3 anesthesia-treated mice were excluded for technical reasons (poor perfusion). Final groups included 10 control (P35 control; 4 male, 6 female) and 16 anesthesia treated (P21 anesthesia + 14 days; 6 male, 10 female) mice. Brains were prepared and sectioned as described for other animals in the study.

Immunohistochemistry

Sagittal sections between 0.60 and 0.84 mm lateral to the midline were used.29 The slices were incubated in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4) for ten minutes. Slide-mounted sections were permeabilized for four hours in 5% Tween-20 and 7.5% glycine in PBS on a shaker plate. Sections were blocked for one hour at room temperature in 5% normal goat serum, 5% Tween-20, 0.75% glycine and 0.5% non-fat dry milk in PBS before the primary antibodies were added.

Slides with up to four brain sections were immunostained with 1:1000 chicken anti-GFP (ab13970; Abcam, Boston, MA) and 1:100 rabbit anti-caspase-3 (9661L; Cell signaling, Danvers, MA) for the P21 groups; or anti-GFP, 1:200 mouse anti-calretinin (MAB1568; Millipore, Billerica, MA) and 1:200 rabbit anti-Ki67 (VP-K451; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for the P81 groups. P35 groups were immunostained with anti-caspase-3, anti-calretinin and anti-Ki67. Sections were incubated with the primary antibodies at room temperature overnight. The next day sections were rinsed in 5% Tween-20 and 7.5% glycine in PBS and incubated in AlexaFluor 488 goat anti-chicken, AlexaFluor 594 goat anti-rabbit, AlexaFluor 594 goat anti-mouse or AlexaFluor 647 goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR), as appropriate to match primary antibody species. All secondary antibodies were used at 1:750. Sections were washed in PBS, dehydrated in an ascending ethanol series, cleared in xylenes and mounted with Krystalon (Harleco, Darmstadt, Germany).

Brain sections from the P35 group were also immunostained for BrdU. Slides with up to four brain sections were permeabilized in 0.5% Igepal Tris-HCL buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. Slides were then incubated at 37°C in 3μg/ml protease (#53702, EMD Millipore, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) Tris-HCL with CaCl2 buffer for 30 minutes, ice-cold 0.1M HCL for 10 minutes, and 2M HCL for 20 minutes. Slides were blocked in 5% normal donkey serum before the primary antibody was added. Slides were incubated overnight at 4°C with 1:200 rat anti-BrdU (#347580; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The next day slides were rinsed in 5% normal donkey serum and 0.5% Igepal in PBS and incubated in 1:750 AlexaFluor 488 donkey anti-rat. Sections were washed in PBS, dehydrated in an ascending ethanol series, cleared in xylenes and mounted with Krystalon (Harleco, Darmstadt, Germany).

GFP and calretinin immunostaining failed in one P81 control mouse. BrdU staining failed in one P21 anesthesia + 14 day mouse. Calretinin staining failed in three P35 control mice, and four P21 anesthesia + 14 day mice. Immunostaining failures are attributed to technical problems with immunohistochemical procedures. In some of these cases, all available tissue from an animal was used up such that it was not possible to repeat immunohistochemical stains. Decisions to exclude immunostained brain sections were made without knowledge of treatment group according to pre-established criteria (e.g. tissue lost or damaged during processing, positive controls are negative). Animal numbers (n) for each measure are reported in the text.

Confocal Microscopy and Histological Analyses

All image collection and analyses were conducted by an investigator unaware of group assignment. GFP/Caspase-3 double labeling (P21 groups) and GFP/calretinin/Ki67 triple labeling (P81 groups) was imaged using a Leica SP5 confocal system set up on a DMI 6000 inverted microscope equipped with a 63X oil immersion objective (NA 1.4). Images were collected at 1 μm increments to generate three-dimensional confocal “z-stacks”. Specifically, confocal image stacks through the z-depth were collected from the midpoint of both the upper and lower blades of the dentate cell body layer (2 confocal z-stacks/animal, each with a field size of 240 × 240 μm). Image stacks were then imported into Neurolucida software (V10.31; MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT) for quantification. For the P35 groups, Calretinin, Ki67 and BrdU immunostained sections were imaged using a Nikon A1 confocal microscope equipped with a 20X, 0.75 NA objective. Images of an entire dentate gyrus from each mouse were collected at 1 μm increments through the z-depth of the tissue. Image sets were quantified using IMARIS software (version 64 7.7.2) for calretinin and Ki67 and both Imaris and Neurolucida software for BrdU-labeled sections (Investigator-conducted BrdU counts using Neurolucida were used to validate the automated Imaris counting approach; Neurolucida counts are reported for BrdU). The number of caspase 3 immunopostive cells in the dentate gyri of P35 mice was counted using a DMI 6000 inverted microscope under a 63X oil immersion objective (NA 1.4). Two to four dentate gyri/mouse were counted (damaged sections were excluded). The number of GFP-expressing hilar/molecular layer granule cells in the P81 groups were counted using an identical strategy. All cell counting approaches used a variation of the optical dissector method to prevent bias due to changes in cell size .14Counts were normalized to the volume of dentate present in each region of interest. Cell numbers/hippocampus were converted to density (mm3) using the following equation (# cells per dentate/[DGC layer area X 20 μm volume]) X 109. No adjustments were made for tissue shrinkage.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Data were tested for normality (Shapiro-Wilk) and equal variance (Brown-Forsythe). Parametric data were compared using two-tailed Student's t-tests. Data that failed tests for either normality or equal variance were either transformed to normalize the data or compared using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. For all analyses, statistical significance was determined using Sigma Stat software (version 12.3). Specific statistical tests used are noted in the results. All parameters examined were statistically equivalent between males and females (data not shown), so data were pooled for analysis. Measurements from the upper and lower blades of the dentate gyrus were also found to be statistically equivalent for all parameters examined (data not shown), so upper and lower blade data sets were combined for simplicity. Statistical significance was accepted for P<0.05.

Figure preparation

Figures were prepared using Adobe Photoshop (CS5-Extended). Brightness and contrast were adjusted to optimize cellular detail. Identical adjustments were made to all images meant for comparison.

Results

Anesthetic exposure significantly increases cell death among two-week-old dentate granule cells

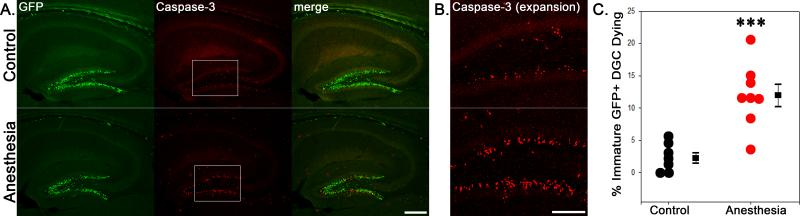

GFP-expressing granule cells were evident in the dentate hilus and inner third of the dentate granule cell body layer in control and anesthetized animals immediately following exposure on P21, consistent with the known proliferation and migration patterns of these neurons.30 The density and localization of GFP-expressing cells was similar in control and anesthesia-treated mice (Fig.1; P21 control, n=7, 241,000±26,000 GFP positive cells/ mm3; P21 anesthesia, n=8, 243,000±24,000 cells/mm3; P=0.961, t-test), demonstrating that progenitor cell labeling was equivalent between the two groups. Exposure to isoflurane, however, led to a dramatic increase in the number of caspase-3 immunoreactive cells in the dentate gyrus (Fig.1), consistent with previous studies.13,14 Moreover, quantification of caspase-3 immunolabeling in GFP-expressing cells revealed a five-fold increase in double-labeled cells relative to controls. Specifically, in 21-day-old control animals, 2.05±0.75% of GFP-expressing cells co-labeled with caspase-3, while 11.03±1.75% of cells in the P21 anesthesia group expressed caspase-3 (Fig.1; P<0.001, t-test). Our results demonstrate that these young, ≈two-week-old GFP-expressing cells are vulnerable to anesthesia-induced cell death.

Figure 1.

A: Anesthetic exposure increases caspase-3 expression in two week-old dentate granule cells (DGC) immediately following exposure. Confocal maximum projections of hippocampal sections from representative 21-day-old mice exposed to 1.5% isoflurane (anesthesia) or room air (control) for six hours. Sections are immunostained for green fluorescent protein (GFP) and caspase-3, a marker of apoptotic cell death. Scale bar = 250 μm. B: Boxed regions in A are shown at higher resolution. Scale bar = 125 μm. C: Scatterplot shows the percentage of GFP-expressing cells in the dentate gyrus that were also immunoreactive for caspase-3 immediately following exposure. Each dot represents one animal. Boxes are means ± SEM. ***P<0.001, Student's t-test.

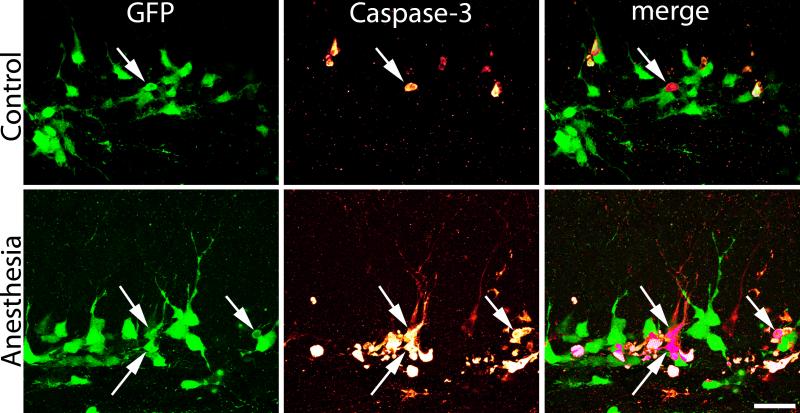

GFP expression reveals the morphology of caspase-3 immunoreactive cells

One advantage of the fate-mapping approach used here is that the morphology of dying cells can be readily assessed. In the P21 anesthesia group, GFP-expressing, caspase-3 immunoreactive granule cells exhibited morphological changes consistent with cell degeneration. Specifically, cells had small, condensed cell bodies suggestive of pyknosis (Fig.2). Indeed, caspase-3-immunoreactive cells could be easily identified by this feature when examining GFP-expression alone. When present, the processes of GFP-expressing, caspase-3 immunoreactive cells ran either parallel to the granule cell layer, indicative of Type II progenitor cells, or projected perpendicularly into the granule cell layer. Processes of these latter cells lacked dendritic spines and terminated prior to reaching the outer molecular layer – morphological features possessed by immature granule cells. Combined, these morphological criteria suggest that anesthesia induces neuronal pyknosis and cell death in late progenitor and immature granule cells; a conclusion consistent with prior work showing that dying cells express the progenitor cell and early differentiation markers NeuroD1 and calretinin.14

Figure 2.

Green fluorescent protein (GFP) reveals the cellular morphology and integrity of dentate granule cells in control and anesthesia-exposed mice. Images show representative cells after a six-hour exposure to room air or isoflurane. Isoflurane dramatically increased caspase-3 immunoreactivity. Arrows denote double-labeled cells. In the anesthesia-treated animal, the two cells in the center of the image have short, aspiny dendrites projecting into the dentate molecular layer; morphological features of immature granule cells. Morphology suggests cellular disintegration. Scale bar = 20 μm.

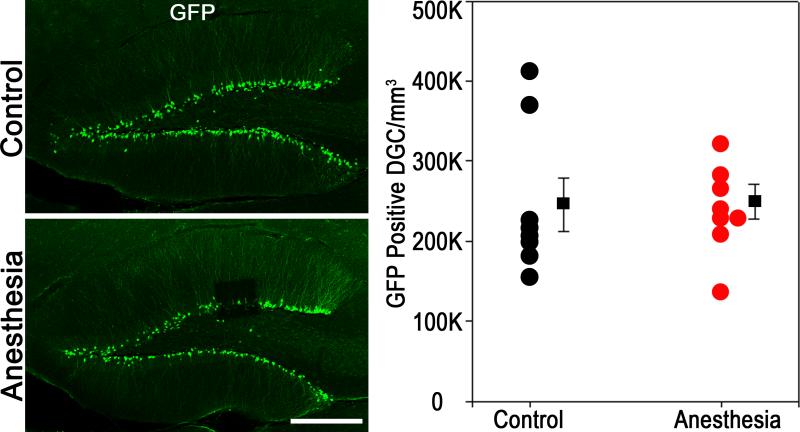

Fate-mapped dentate granule cell numbers recover 60 days after anesthesia exposure

Quantification of GFP-expressing cells in the dentate 60 days after isoflurane exposure revealed similar densities in 81 day-old control mice and 81 day-old mice exposed to isoflurane at P21 (Fig.3; P81 control, n=7, 245,000±33,000 GFP-expressing cells/mm3; P21 anesthesia+60 days, n=8, 250,000±22,000 cells/mm3; P=0.915, t-test). These findings may reflect either a regeneration of this population, presumably by increased proliferation of surviving, GFP-expressing progenitor cells, or alternatively, anesthesia exposure might have simply accelerated the death of newborn cells fated to undergo natural apoptosis at a later stage.

Figure 3.

Anesthesia-induced apoptotic cell death in two week-old dentate granule cells (DGC) does not lead to long-term diminution in neuronal density in this population. Confocal maximum projections show immunostaining for green fluorescent protein (GFP) in representative two month-old animals exposed to six hours of 1.5% isoflurane (anesthesia) or room air (control) on P21. No differences between control and anesthesia-treated mice were found. Scale bar = 250 μm. Scatterplot shows the density of GFP-expressing cells in the dentate granule cell body layer. Circles represent individual animal means, while squares reflect group means ± SEM. The two groups were statistically equivalent (P=0.915, Student's t-test).

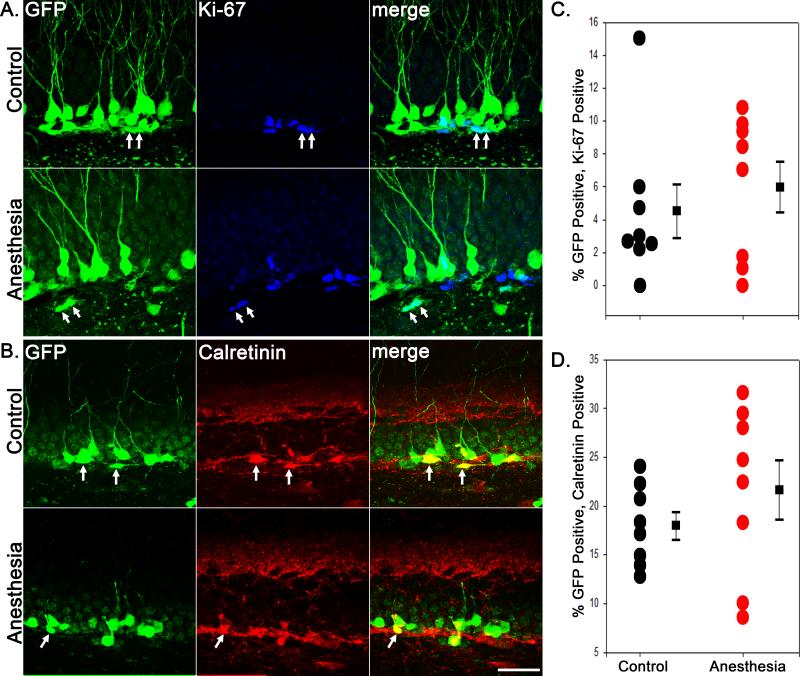

The cohort of fate-mapped GFP-expressing granule cells exhibits similar rates of proliferation 60 days after anesthesia exposure

It is conceivable that the observed anesthesia-induced loss of immature granule cells in 21-day-old mice might produce a lasting alteration in adult granule cell neurogenesis, since neurogenesis is very sensitive to a variety of physiological and pathological stimuli.31 To explore this possibility, we co-labeled GFP-expressing neurons with the proliferative cell marker Ki-67, and the immature granule cell marker calretinin. No significant differences were found in the percentage of GFP-positive granule cells that coexpressed either Ki-67 or calretinin 60 days after exposure (Fig.4). In P81 controls, 4.49±1.62% (n=8) and 17.94±1.41% (n=7) of GFP-labeled cells expressed Ki-67 or calretinin, respectively. In the P21 anesthesia+60 days, 5.99±1.55% of GFP-labeled cells expressed Ki-67 (n=8, P=0.517, t-test compared with control) and 21.65±3.06% expressed calretinin (n=8, P=0.291, t-test compared with control). These findings indicate that the cohort of granule cell progenitors labeled with GFP exhibits normal proliferation rates at this time point. These findings also demonstrate active proliferation within the GFP-expressing cell population in these animals, consistent with the possibility that neurons lost to anesthesia exposure may be replaced by subsequent neurogenesis.

Figure 4.

Anesthesia-induced apoptotic cell death in two week-old dentate granule cells does not lead to alterations in neuronal proliferation in this population. Confocal maximum projections showing green fluorescent protein (GFP)+Ki67 (A) and GFP+Calretinin (B) immunostaining in the hippocampal granule cell layer. Double-labeled cells are denoted by arrows. Scale bar = 30 μm. Scatterplots show the percentage of GFP-expressing cells double-labeled with Ki67 (C) or calretinin (D). Circles represent individual animal means, while squares reflect group means ± SEM. The two groups were statistically equivalent for both Ki67 and calretinin.

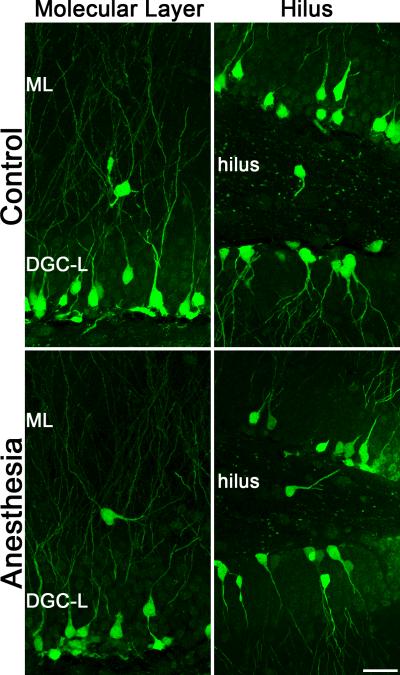

Mice exposed to anesthesia on P21 show no evidence of granule cell migration defects in adulthood

Postnatally-generated granule cells are produced in the subgranular zone, located immediately below the granule cell body layer, and migrate short distances (10s of microns) to occupy final positions in the inner third of the granule cell layer. Smaller numbers of granule cells migrate to the middle and outer thirds of the cell body layer in healthy animals. A variety of brain insults, such as seizures, can disrupt granule cell migration. Under pathological conditions, large numbers of granule cells can migrate in the wrong direction to reside ectopically in the dentate hilus; or they can migrate too far, traveling through the granule cell layer to take final positions in the dentate molecular layer.32-34 To determine whether anesthesia exposure disrupted granule cell migration, the number of GFP-expressing granule cells in the dentate hilus and molecular layer was determined. The number of GFP-expressing ectopic cells in the hilus (P81 control, n=8, 3.31±0.57 cells/hippocampal section; P21 anesthesia+60 days, n=8, 4.25±0.85; P=0.372, t-test compared with control) and molecular layer (P81 control, n=8, 1.38±0.26 cells/hippocampal section; P21 anesthesia+60 days, n=8, 1.88±0.61; P=0.464, t-test compared with control) was similar between groups, suggesting that cells born after anesthesia treatment followed normal migration patterns (Fig.5).

Figure 5.

Confocal maximum projections from P81 control and P21 anesthesia + 60 day mice showing green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing cells misplaced to either the dentate molecular layer (ML) or hilus. No differences in the frequency of ectopic cells were evident between groups, and the overwhelming majority of GFP-labeled cells were correctly localized to the granule cell body layer (DGC-L). Scale bar = 25 μm.

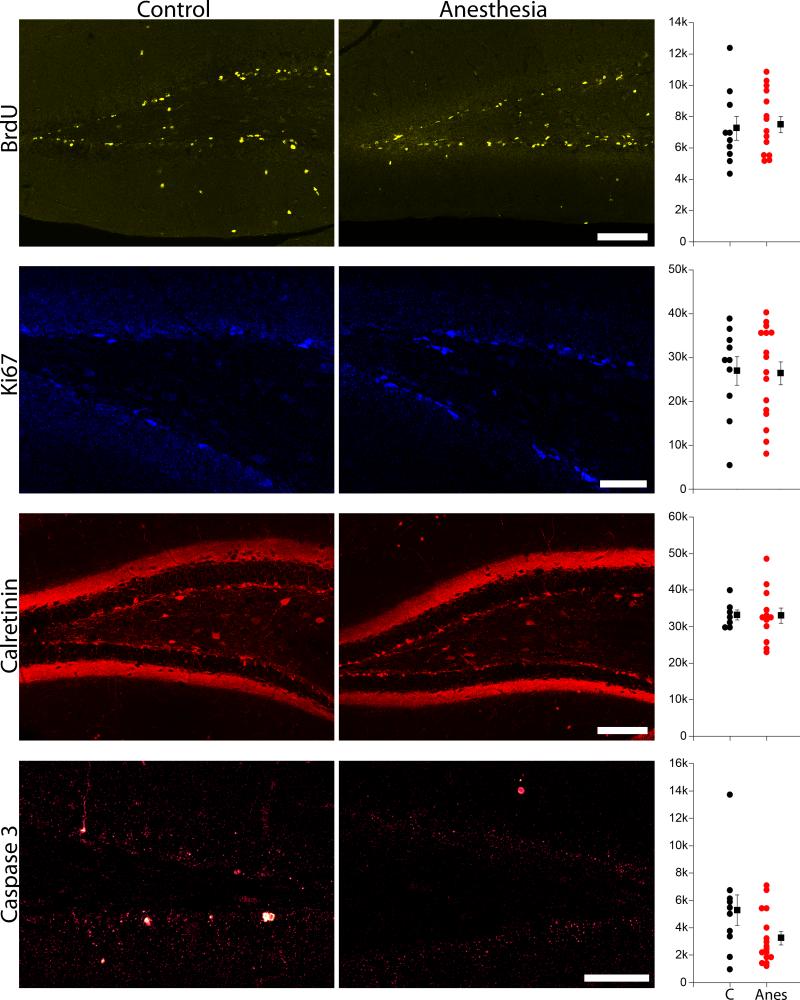

Neurogenesis is not increased in the weeks after anesthesia exposure

To determine whether the recovery in GFP-expressing granule cell numbers reflected increased proliferation in the dentate, a second group of mice was treated with the S-phase proliferative marker BrdU two, four, six, eight and ten days after isoflurane treatment on P21. This BrdU injection protocol covers a period during which increased cell proliferation was previously demonstrated following adult exposure to isoflurane.35 Mice were sacrificed 14 days after anesthesia treatment on P35. No difference in the density of BrdU stained cells was evident between the two groups (Fig.6; P35 control, n=10; P21 anes+14 days, n=15; t-test, p=0.771), suggesting that proliferation was not increased during the time period of BrdU injections.

Figure 6.

BrdU, Ki67, calretinin and caspase 3 labeling in P35 control (C) and P21 anesthesia + 14 day (Anes) mice. Scale bars = 100 μm (BrdU, calretinin) and 50 μm (Ki67 and caspase 3). Scatterplots shows the density of labeled cells in the dentate granule cell body layer for each corresponding image set. Circles represent individual animal means, while squares reflect group means ± SEM. The two groups were statistically equivalent for all measures (P>0.05, Student's t-test).

The P35 control and P21 anesthesia+14 day groups were also immunostained for the proliferative cell marker Ki67. Ki67 provides a snapshot of cycling cells at the time the animals were perfused (P35). No difference in the density of Ki67 positive cells in the dentate gyrus was evident between the two groups (Fig.6; P35 control, n=10; P21 anes+14 days, n=16; t-test, p=0.904), indicating similar numbers of proliferating cells at the time of sacrifice.

Finally, the P35 control and P21 anesthesia+14 day groups were immunostained with the immature granule cell marker calretinin, which is expressed in granule cells roughly 14 to 28 days old. Calretinin staining provides a measure of neurogenesis rates two to four weeks earlier. No differences in the number of calretinin-labeled cells were evident between groups (Fig.6; P35 control, n=7; P21 anes+14 days, n=12; t-test, p=0.964).

Anesthesia-treated mice show a trend towards reduced apoptosis two weeks after anesthesia exposure

The recovery in granule cell numbers two months after isoflurane exposure could reflect increased neurogenesis, or decreased apoptosis (or both). To explore the possibility that survival might be enhanced following isoflurane treatment, P35 control and P21 anesthesia + 14 day groups were immunostained for activated caspase 3. Anesthesia-treated mice showed a non-significant trend towards reduced density of caspase 3 immunoreactive neurons in the dentate (Fig.6; P35 control, n=10; P21 anes+14 days, n=16; t-test on square root transformed data, P=0.075). We interpret this trend cautiously, however, as it is partly driven by the presence of an outlier in the control group (P=0.201 with outlier removed).

Discussion

In the present study, we examined anesthesia-induced cell death among immature hippocampal granule cells produced by a cohort of Gli1-expressing granule cell progenitors. GFP expression among progenitor cells was induced on postnatal day seven, and animals were exposed to isoflurane on postnatal day 21. GFP-labeled immature granule cells, therefore, would be up to two weeks old at the time of exposure. Isoflurane treatment produced a five-fold increase in apoptosis among GFP-labeled daughter cells, confirming that this age-range is vulnerable to anesthesia-induced cell death. However, despite the loss of GFP-expressing cells immediately after isoflurane exposure, no differences in the density of GFP-labeled cells were evident 60 days later, when the animals were young adults. This finding demonstrates that isoflurane treatment does not produce persistent cell loss among the cohort of GFP-labeled neurons. Integration of the GFP-labeled granule cells was also grossly normal, with no evidence of migration defects among the population. Finally, we did not observe any change in the rate of hippocampal neurogenesis between isoflurane-treated animals and controls either two weeks or two months after exposure. Taken together, these findings indicate that the murine hippocampus can restore neuron numbers following anesthesia exposure, possibly via modest reductions in apoptosis that occur below levels of detection.

Cell fate-mapping to assess the impact of anesthesia exposure

A key strength of the fate-mapping approach utilized here is that it provides an accurate measure of net neurogenesis/apoptosis rates over the entire experimental time window. Other approaches commonly used to assess the impact of anesthetic neurotoxicity -- such as BrdU labeling, cell death markers and immunohistochemical markers of neurogenesis -- only provide snapshots of neurogenesis/cell death rates at the time the animal is killed, significantly limiting conclusions about the net effects of anesthesia exposure. Repeated histological assessments at different time points following anesthetic exposure can mitigate these limitations, but still risk missing critical windows of vulnerability during time periods not examined. Moreover, traditional approaches poorly capture a second source of neuronal elimination; loss of progenitor cells. Specifically, although caspase-3 immunostaining can detect the death of a single progenitor cell, it provides no information about the number of daughter cells the progenitor might have produced had it survived. Finally, there is evidence from in vitro studies of human neural progenitor cell lines that isoflurane can inhibit cell proliferation.36 In order to capture changes in cell proliferation and the aforementioned effects on cell loss, fate mapping provides an attractive measure of net progenitor cell productivity (e.g. the number of daughter cells that were produced and survived to the experimental endpoint).

Reduced natural apoptosis post-anesthesia may restore neuron numbers in the dentate gyrus

We have previously demonstrated that postnatally-generated granule cells are selectively vulnerable to anesthesia-induced cell death about two weeks after they are generated using BrdU birthdating and immunohistochemical phenotyping techniques.14 The fate mapping approach utilized here confirms our prior findings, demonstrating significant loss of immature granule cells following anesthesia exposure.

Our earlier work did not reveal whether the cell death observed immediately after isoflurane exposure captured the bulk of the cell loss; whether it was merely the “tip of the iceberg,” with secondary waves of cell loss occurring hours, days or even weeks later; or whether cell numbers recovered. We now demonstrate an absence of detectable change in the density of GFP-expressing cells in adult animals treated with isoflurane on P21. This result reveals that the dentate is able to reestablish appropriate neuron numbers during the two month interval following the insult. This result partly contrasts with work by Zhu and colleagues (2010) in rats, who found a modest decrease in granule cell numbers ten weeks after four, 35 minute isoflurane exposures between days 14-17.37 Whether the different treatment paradigm, species or earlier exposure accounts for the opposing results remains to be determined, but all could be critical variables. Notably, even earlier, P7 treatment with isoflurane has been shown to decrease neurogenesis and lead to learning deficits in adulthood,38 while treatment of 12-week-old rats does not appear to alter proliferation.39 Together, these findings suggest that the window of vulnerability for long-term reductions in cell numbers closes prior to P21. Restated, the most pronounced loss occurs around P7, more modest loss is evident following exposure a week later (P14), and P21 exposure produces damage that is qualitatively adult-like, impacting neurogenic brain regions which then recover. Quantitatively, P21 exposure produces greater acute cell loss than observed in adults, reflecting the larger population of vulnerable, immature neurons present during this developmental period. Whether the greater degree of acute cell loss at P21 produces any subtle changes which are distinct from adults remains to be determined.

To explore possible mechanisms by which appropriate cell numbers might be restored, calretinin and Ki67 immunostaining was conducted at the two month time point, and calretinin, Ki67, BrdU and caspase 3 labeling was examined in an additional group of animals collected two weeks after exposure. Ki67 labels actively proliferating cells, providing a snapshot of cell division at the animals time of death, and calretinin labels two- to four-week-old granule cells,40 providing measures of neurogenesis around the time of anesthesia treatment. The cell birthdating marker BrdU was injected between two and ten days after isoflurane exposure to assess neurogenesis during this period. A wide variety of stimuli can induce hippocampal neurogenesis,41-43 including neuronal loss,43-45 so restoration of cell numbers by increased neurogenesis is quite plausible.

Despite a multi-pronged approach to gather information about neurogenesis rates at numerous time points after isoflurane exposure, no evidence of increased neurogenesis was found. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that neurogenesis is increased at remaining time points not examined here, it seems increasingly likely that the injury caused by P21 isoflurane-exposure does not induce a dramatic burst of neurogenesis in the dentate. It remains possible that a modest, but prolonged, increase in neurogenesis replaces lost neurons. Such an increase might be sufficient to replace the lost cells, while still remaining below detection thresholds of the techniques used here.

A second possibility that cannot be fully excluded by the present findings is that there is a modest increase in the survival of newborn granule cells. Granule cells are produced in significant excess, and many undergo apoptosis under normal conditions. Inactive granule cells are preferentially eliminated.46 Anesthesia-induced loss of granule cells could be naturally offset by increased neuronal activity funneled to the remaining cells, thereby enhancing their survival. Such a mechanism might operate over weeks to months, making it difficult to detect.

Significance and limitations of the present findings

It remains possible that subtle changes in granule cell structure or function might lead to long-lasting deficits in hippocampal-dependent tasks. Indeed, Briner and colleagues demonstrated a persistent increase in spine density among cortical neurons following exposure to propofol in rats at 15, 20 and 30 days,47 and Mintz and colleagues have shown that isoflurane can disrupt axonal targeting in cultured neocortical slices.48 Additional studies to characterize the morphology and physiology of exposed granule cells will be needed to determine whether they function normally.49

A question worth considering is whether a temporary loss of two week-old hippocampal granule cells might produce lasting changes in brain function. Even though our findings support the conclusion that these lost neurons are ultimately replaced, it presumably still takes several weeks to regenerate the lost cells. Newborn granule cells transiently exhibit a variety of unique physiological properties during a period occurring approximately three to six weeks after they are generated. These properties include increased excitability, lower inhibition and enhanced long-term potentiation.31 The functional significance of this unique population of granule cells remains controversial; however, numerous lines of evidence suggest they are important for memory and cognition. Loss of this population of cells – even temporarily – might have a profound impact on the hippocampal circuit. This could be particularly relevant for the developing brains of young children. Consistent with this idea, experimental manipulations that transiently deplete adult-generated granule cells have been shown to produce a variety of behavioral deficits, including disruption of hippocampal dependent memory,50-52 impaired responses to anti-depressant medications53-55 and altered responses to convulsant drugs.56,57 Deficiencies in recollection memory have recently been observed five to ten years following anesthesia and surgery in infancy, 58 possibly reflecting long-term consequences of transient hippocampal disruption. Animal and human studies designed to detect such transient deficits should be carefully timed with regard to the exposure period to optimize the chances of observing an effect.

In summary, exposing three-week-old mice -- comparable in brain development to human infants -- to a clinically relevant dose of isoflurane for six hours increased apoptotic cell death among two-week-old dentate granule cells. Fate-mapping the exposed population, however, did not reveal a reduction in neuronal numbers after the animals reached adulthood. Taken together, these findings indicate that overt neuronal loss may not be a significant consequence of P21 anesthesia exposure in this regenerative population. The results leave open the possibility, however, that more subtle changes in neuronal structure or function may still occur in dentate.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Masimo-China-CCHMC Pediatric Anesthesia Research Fellowship Program (Cincinnati, Ohio, USA) and the National Institutes of Health (SCD, 2R01-NS-065020, 1R03-NS-064378 and 2R01-NS-062806)(Bethesda, Maryland, USA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke or the National Institutes of Health. We thank Keri Kaeding (MFA, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA) for assistance with previous versions of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests

References

- 1.Lin EP, Lee J-R, Loepke AW. Anesthetics and the Developing Brain: The Yin and Yang. Current Anesthesiology Reports. 2015;5:177–189. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim JS, Kondratyev A, Tomita Y, Gale K. Neurodevelopmental impact of antiepileptic drugs and seizures in the immature brain. Epilepsia. 2007;48(Suppl 5):19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forcelli PA, Kim J, Kondratyev A, Gale K. Pattern of antiepileptic drug-induced cell death in limbic regions of the neonatal rat brain. Epilepsia. 2011;52:e207–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson AJ, Disma N, de Graaff JC, Withington DE, Dorris L, Bell G, Stargatt R, Bellinger DC, Schuster T, Arnup SJ. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years of age after general anaesthesia and awake-regional anaesthesia in infancy (GAS): an international multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2016;387:239–250. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00608-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilder RT, Flick RP, Sprung J, Katusic SK, Barbaresi WJ, Mickelson C, Gleich SJ, Schroeder DR, Weaver AL, Warner DO. Early exposure to anesthesia and learning disabilities in a population-based birth cohort. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:796–804. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000344728.34332.5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun L. Early childhood general anaesthesia exposure and neurocognitive development. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105(Suppl 1):i61–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Backeljauw B, Holland SK, Altaye M, Loepke AW. Cognition and Brain Structure Following Early Childhood Surgery With Anesthesia. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e1–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ing CH, DiMaggio CJ, Malacova E, Whitehouse AJ, Hegarty MK, Feng T, Brady JE, von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Davidson AJ, Wall MM, Wood AJJ, Li G, Sun LS. Comparative Analysis of Outcome Measures Used in Examining Neurodevelopmental Effects of Early Childhood Anesthesia Exposure. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:1319–32. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen TG, Pedersen JK, Henneberg SW, Pedersen DA, Murray JC, Morton NS, Christensen K. Academic performance in adolescence after inguinal hernia repair in infancy: a nationwide cohort study. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:1076–85. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31820e77a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartels M, Althoff RR, Boomsma DI. Anesthesia and cognitive performance in children: no evidence for a causal relationship. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2009;12:246–53. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.3.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nikizad H, Yon JH, Carter LB, Jevtovic-Todorovic V. Early exposure to general anesthesia causes significant neuronal deletion in the developing rat brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1122:69–82. doi: 10.1196/annals.1403.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loepke AW, Istaphanous GK, McAuliffe JJ, 3rd, Miles L, Hughes EA, McCann JC, Harlow KE, Kurth CD, Williams MT, Vorhees CV, Danzer SC. The effects of neonatal isoflurane exposure in mice on brain cell viability, adult behavior, learning, and memory. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:90–104. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818cdb29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng M, Hofacer RD, Jiang C, Joseph B, Hughes BA, Danzer SC, Loepke AW. Brain regional vulnerability to anaesthesia-induced neuronal cell death shifts with age during exposure and extends into adulthood for some regions. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:443–51. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofacer RD, Deng M, Ward CG, Joseph B, Hughes EA, Jiang C, Danzer SC, Loepke AW. Cell age-specific vulnerability of neurons to anesthetic toxicity. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:695–704. doi: 10.1002/ana.23892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krzisch M, Sultan S, Sandell J, Demeter K, Vutskits L, Toni N. Propofol Anesthesia Impairs the Maturation and Survival of Adult-born Hippocampal Neurons. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:602–10. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182815948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Workman AD, Charvet CJ, Clancy B, Darlington RB, Finlay BL. Modeling transformations of neurodevelopmental sequences across mammalian species. J Neurosci. 2013;33:7368–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5746-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spalding KL, Bergmann O, Alkass K, Bernard S, Salehpour M, Huttner HB, Bostrom E, Westerlund I, Vial C, Buchholz BA, Possnert G, Mash DC, Druid H, Frisen J. Dynamics of hippocampal neurogenesis in adult humans. Cell. 2013;153:1219–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Keefe J, Nadel L. The hippocampus as a cognitive map. Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press; Oxford, New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scoville WB, Milner B. Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:11–21. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.20.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kesner RP, Rolls ET. A computational theory of hippocampal function, and tests of the theory: new developments. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;48:92–147. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hester MS, Hosford BE, Santos VR, Singh SP, Rolle IJ, LaSarge CL, Liska JP, Garcia-Cairasco N, Danzer SC. Impact of rapamycin on status epilepticus induced hippocampal pathology and weight gain. Experimental neurology. 2016;280:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn S, Joyner AL. Dynamic changes in the response of cells to positive hedgehog signaling during mouse limb patterning. Cell. 2004;118:505–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahn S, Joyner AL. In vivo analysis of quiescent adult neural stem cells responding to Sonic hedgehog. Nature. 2005;437:894–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura T, Colbert MC, Robbins J. Neural crest cells retain multipotential characteristics in the developing valves and label the cardiac conduction system. Circ Res. 2006;98:1547–54. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000227505.19472.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy BL, Pun RY, Yin H, Faulkner CR, Loepke AW, Danzer SC. Heterogeneous integration of adult-generated granule cells into the epileptic brain. J Neurosci. 2011;31:105–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2728-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harkness J, Wagner J. The Biology and Medicine of Rabbits and Rodents. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore (MD): 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talan M. Body temperature of C57BL/6J mice with age. Experimental gerontology. 1984;19:25–29. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(84)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams CS. Practical guide to laboratory animals. CV Mosby Co.; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates, Compact 2nd edition. Elsevier Academic Press; Amsterdam ; Boston: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathews EA, Morgenstern NA, Piatti VC, Zhao C, Jessberger S, Schinder AF, Gage FH. A distinctive layering pattern of mouse dentate granule cells is generated by developmental and adult neurogenesis. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:4479–90. doi: 10.1002/cne.22489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christian KM, Song H, Ming GL. Functions and dysfunctions of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2014;37:243–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-014134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jessberger S, Zhao C, Toni N, Clemenson GD, Jr., Li Y, Gage FH. Seizure-associated, aberrant neurogenesis in adult rats characterized with retrovirus-mediated cell labeling. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9400–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2002-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy BL, Danzer SC. Somatic translocation: a novel mechanism of granule cell dendritic dysmorphogenesis and dispersion. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2959–64. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3381-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hester MS, Danzer SC. Accumulation of abnormal adult-generated hippocampal granule cells predicts seizure frequency and severity. J Neurosci. 2013;33:8926–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5161-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin N, Moon TS, Stratmann G, Sall JW. Biphasic change of progenitor proliferation in dentate gyrus after single dose of isoflurane in young adult rats. Journal of neurosurgical anesthesiology. 2013;25:306. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e318283c3c7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao X, Yang Z, Liang G, Wu Z, Peng Y, Joseph DJ, Inan S, Wei H. Dual effects of isoflurane on proliferation, differentiation, and survival in human neuroprogenitor cells. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:537–49. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182833fae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu C, Gao J, Karlsson N, Li Q, Zhang Y, Huang Z, Li H, Kuhn HG, Blomgren K. Isoflurane anesthesia induced persistent, progressive memory impairment, caused a loss of neural stem cells, and reduced neurogenesis in young, but not adult, rodents. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2010;30:1017–1030. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stratmann G, Sall JW, May LD, Bell JS, Magnusson KR, Rau V, Visrodia KH, Alvi RS, Ku B, Lee MT. Isoflurane differentially affects neurogenesis and long-term neurocognitive function in 60-day-old and 7-day-old rats. The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 2009;110:834–848. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819c463d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erasso DM, Camporesi EM, Mangar D, Saporta S. Effects of isoflurane or propofol on postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in young and aged rats. Brain research. 2013;1530:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao C, Deng W, Gage FH. Mechanisms and functional implications of adult neurogenesis. Cell. 2008;132:645–660. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malberg JE, Eisch AJ, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9104–10. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09104.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kempermann G, Gast D, Gage FH. Neuroplasticity in old age: sustained fivefold induction of hippocampal neurogenesis by long-term environmental enrichment. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:135–43. doi: 10.1002/ana.10262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dash PK, Mach SA, Moore AN. Enhanced neurogenesis in the rodent hippocampus following traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Res. 2001;63:313–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20010215)63:4<313::AID-JNR1025>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yeung ST, Myczek K, Kang AP, Chabrier MA, Baglietto-Vargas D, Laferla FM. Impact of hippocampal neuronal ablation on neurogenesis and cognition in the aged brain. Neuroscience. 2014;259:214–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gould E, Tanapat P. Lesion-induced proliferation of neuronal progenitors in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat. Neuroscience. 1997;80:427–36. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tashiro A, Sandler VM, Toni N, Zhao C, Gage FH. NMDA-receptor-mediated, cell-specific integration of new neurons in adult dentate gyrus. Nature. 2006;442:929–933. doi: 10.1038/nature05028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Briner A, Nikonenko I, De Roo M, Dayer A, Muller D, Vutskits L. Developmental Stage-dependent Persistent Impact of Propofol Anesthesia on Dendritic Spines in the Rat Medial Prefrontal Cortex. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:282–293. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318221fbbd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mintz CD, Barrett KM, Smith SC, Benson DL, Harrison NL. Anesthetics interfere with axon guidance in developing mouse neocortical neurons in vitro via a gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor mechanism. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:825–33. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318287b850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagner M, Ryu YK, Smith SC, Patel P, Mintz CD. Review: Effects of anesthetics on brain circuit formation. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2014;26:358–62. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saxe MD, Battaglia F, Wang JW, Malleret G, David DJ, Monckton JE, Garcia AD, Sofroniew MV, Kandel ER, Santarelli L, Hen R, Drew MR. Ablation of hippocampal neurogenesis impairs contextual fear conditioning and synaptic plasticity in the dentate gyrus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17501–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607207103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakashiba T, Cushman JD, Pelkey KA, Renaudineau S, Buhl DL, McHugh TJ, Rodriguez Barrera V, Chittajallu R, Iwamoto KS, McBain CJ, Fanselow MS, Tonegawa S. Young dentate granule cells mediate pattern separation, whereas old granule cells facilitate pattern completion. Cell. 2012;149:188–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tronel S, Belnoue L, Grosjean N, Revest JM, Piazza PV, Koehl M, Abrous DN. Adult-born neurons are necessary for extended contextual discrimination. Hippocampus. 2012;22:292–8. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, Surget A, Battaglia F, Dulawa S, Weisstaub N, Lee J, Duman R, Arancio O, Belzung C, Hen R. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science. 2003;301:805–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu MV, Hen R. Functional dissociation of adult-born neurons along the dorsoventral axis of the dentate gyrus. Hippocampus. 2014;24:751–61. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miller BR, Hen R. The current state of the neurogenic theory of depression and anxiety. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2015;30:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iyengar SS, LaFrancois JJ, Friedman D, Drew LJ, Denny CA, Burghardt NS, Wu MV, Hsieh J, Hen R, Scharfman HE. Suppression of adult neurogenesis increases the acute effects of kainic acid. Exp Neurol. 2015;264:135–49. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cho KO, Lybrand ZR, Ito N, Brulet R, Tafacory F, Zhang L, Good L, Ure K, Kernie SG, Birnbaum SG, Scharfman HE, Eisch AJ, Hsieh J. Aberrant hippocampal neurogenesis contributes to epilepsy and associated cognitive decline. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6606. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stratmann G, Lee J, Sall JW, Lee BH, Alvi RS, Shih J, Rowe AM, Ramage TM, Chang FL, Alexander TG, Lempert DK, Lin N, Siu KH, Elphick SA, Wong A, Schnair CI, Vu AF, Chan JT, Zai H, Wong MK, Anthony AM, Barbour KC, Ben-Tzur D, Kazarian NE, Lee JY, Shen JR, Liu E, Behniwal GS, Lammers CR, Quinones Z, Aggarwal A, Cedars E, Yonelinas AP, Ghetti S. Effect of general anesthesia in infancy on long-term recognition memory in humans and rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:2275–87. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]