Abstract

Investigating sleep in mental disorders has the potential to reveal both disorder-specific and transdiagnostic psychophysiological mechanisms. This meta-analysis aimed at determining the polysomnographic (PSG) characteristics of several mental disorders.

Relevant studies were searched through standard strategies. Controlled PSG studies evaluating sleep in affective, anxiety, eating, pervasive developmental, borderline and antisocial personality disorders, ADHD, and schizophrenia were included. PSG variables of sleep continuity, depth, and architecture, as well as rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep were considered. Calculations were performed with the “Comprehensive Meta-Analysis” and “R” softwares. Using random effects modeling, for each disorder and each variable, a separate meta-analysis was conducted if at least 3 studies were available for calculation of effect sizes as standardized means (Hedges’g). Sources of variability, i.e., sex, age, and mental disorders comorbidity, were evaluated in subgroup analyses.

Sleep alterations were evidenced in all disorders, with the exception of ADHD and seasonal affective disorders. Sleep continuity problems were observed in most mental disorders. Sleep depth and REM pressure alterations were associated with affective, anxiety, autism and schizophrenia disorders. Comorbidity was associated with enhanced REM sleep pressure and more inhibition of sleep depth. No sleep parameter was exclusively altered in one condition; however, no two conditions shared the same PSG profile.

Sleep continuity disturbances imply a transdiagnostic imbalance in the arousal system likely representing a basic dimension of mental health. Sleep depth and REM variables might play a key role in psychiatric comorbidity processes. Constellations of sleep alterations may define distinct disorders better than alterations in one single variable.

Keywords: meta-analysis, sleep continuity, sleep depth, REM sleep, mental disorders

Introduction

Sleep is a fundamental operating state of the central nervous system, occupying up to a third of the human life span. As such, it may be one of the most important psychophysiological processes for brain function and mental health e.g. (Regier, Kuhl, Narrow & Kupfer, 2012; Harvey, Murray, Chandler & Soehner, 2011). Decades of research have shown that sleep disturbances are highly prevalent in mental disorders and have been associated with adverse effects for cognitive, emotional, and interpersonal functioning (e.g. Kahn, Sheppes & Sadeh, 2013; Rasch & Born, 2013; Walker, 2009). While traditional models proposed that distinct sleep alterations would map to specific mental disorders (e.g. Kupfer, Reynolds, Grochocinski, Ulrich & McEachran, 1986; Kupfer, 1976; Kupfer & Foster, 1972), novel models emphasize the transdiagnostical nature of sleep disturbances as a dimension for brain and mental health (e.g. Harvey et al., 2011; Harvey, 2009). Surprisingly, however, sleep characteristics of mental disorders have not yet been sufficiently described, with data being either limited by methodological variance as for major depression or scarce as for most other disorders. The present meta-analysis aims at filling this gap and at discussing the specific versus dimensional role of sleep disturbances in psychopathology both with respect to research and clinical implications.

Sleep and its assessment

For centuries sleep has been conceptualized as a passive state of absolute repose of the brain (e.g. Coriat, 1912). Only in 1953 with the discovery of rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM (NREM) sleep (Aserinsky & Kleitman, 1953), it became clear that sleep is an active process fundamental for brain function. The question ‘why we sleep’ has started to receive some answers starting from animal research showing the necessity to sleep for survival and key physiological processes, as thermoregulation (e.g. Rechtschaffen, Bergmann, Everson, Kushida, & Gilliand, 1989; Rechtschaffen & Bergmann, 2002). Furthermore, in the last decades, human research on sleep deprivation demonstrated a central role of sleep for mental health, influencing a wide range of cognitive and emotional functions, e.g. memory consolidation and reorganization (e.g. Landmann et al., 2015; Rasch & Born, 2013; Stickgold & Walker, 2013); problem solving and creativity (e.g. Landmann et al., 2014; Wagner, Gais, Haider, Verleger & Born, 2004; Walker, Liston, Hobson & Stickgold, 2002); emotional reactivity and regulation (e.g. Kahn et al., 2013; Baglioni, Spiegelhalder, Lombardo & Riemann, 2010; Walker, 2009); emotional empathy (e.g. Guadagni, Burles, Ferrara & Iaria, 2014); and management of interpersonal conflicts (e.g. Gordon & Chen, 2013).

The gold standard of sleep assessment is polysomnography (PSG) including electrophysiological recordings of brain activity (EEG), muscle activity (EMG), and eye movements (EOG). The recording is scored into different variables defining the continuity and the architecture of sleep. ‘Sleep continuity’ variables relevant for the present meta-analysis are:

Sleep Efficiency Index (SEI): Ratio of Total Sleep Time (TST) to Time in Bed (TIB) x 100 % (or to time from sleep onset until final awakening, i.e. Sleep Period Time - SPT);

Sleep Onset Latency (SOL): Time from lights out until sleep onset (generally defined as first epoch of sleep stage 2)

Total Sleep Time (TST): The total time spent asleep during the recording night;

Number of Awakenings (NA): The total number of awakenings during the night.

Wake After Sleep Onset (WASO): The duration of wake during the night generally defined as the difference between SPT and TST;

‘Sleep architecture’ refers to the distribution of the distinct sleep stages – wake, sleep stage 1, sleep stage 2, slow wave sleep (SWS), rapid eye movement sleep (REM) – that occur in cycles through the night. Sleep architecture variables relevant for the present meta-analysis are:

Total time awake during the night (WAKE): The amount of wake stages as identified through PSG recordings generally presented as percentage of SPT or TST;

Stage 1 (S1): Duration of sleep stage 1 generally presented as percentage of SPT or TST;

Stage 2 (S2): Duration of sleep stage 2 generally presented as percentage of SPT or TST;

Slow Wave Sleep (SWS): Duration of SWS generally presented as percentage of SPT or TST;

Rapid Eye Movement Sleep (REM): Duration of REM generally presented as percentage of SPT or TST.

Finally, different aspects of REM are often further evaluated. REM sleep is a unique state in the sleep-wake cycle characterized by rapid eye movements, a desynchronized EEG (with theta and alpha waves), muscle atonia, and the experience of vivid dreaming. During this sleep state, posture control is lost and autonomic activity is highly unstable, such as sudden intensifications of heart rate and blood pressure occur, breathing becomes irregular and thermoregulation is lowered or suspended (Amici & Zoccoli, 2014). It occurs cyclically throughout sleep in intervals of circa 90 minutes and takes up approximately 20% of the sleep time of healthy adults. Although REM sleep is not divided into stages as NREM sleep (including S1, S2 and SWS), phasic and tonic aspects of this particular sleep stage are often distinguished. Phasic aspects refer to transient and periodic events, such as the rapid eye movements. Phasic events during REM sleep also include peri-orbital integrated potentials, middle ear muscle activity, and skeletal muscle twitches that often appear in correspondence with rapid eye movements. Tonic REM sleep refers to periods in which atonia and desynchronized EEG are present in absence of phasic events (Mallick, Pandi-Perumal, McCarley, & Morrison, 2011). Important REM sleep variables for our work are:

REM Latency (REML): the interval between sleep onset and the onset of the first REM sleep period;

REM Density (REMD): An index that represents the frequency of rapid eye movements during REM sleep.

PSG research in mental disorders psychopathology

PSG research in major depression

The relationship between major depression and sleep has been noted since ancient times. Philosophers and physicians like Plato or Hippocrates already noted that patients afflicted with melancholia complained about sleep disturbances, including problems falling asleep, maintaining sleep, or waking up too early in the morning (described in the book by R. Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in 1621). In the last century, the founder of modern psychiatry, Emil Kraepelin (1909), based on clinical observations, proposed that different types of depression may be accompanied by specific forms of sleep disturbances. In his nosology, neurotic (psychological) depression was characterized by problems falling asleep (prolonged sleep latency), whereas endogenous (biological) depression was accompanied by sleep maintenance problems and early morning awakenings. PSG research in psychopathology started in the 1960s with studies showing that major depression was characterized by alterations of sleep continuity, shortened time in SWS and increased REM sleep pressure, i.e. longer REM sleep duration, shortened REM latency, a prolongation of the first REM period, and increased REM density (Riemann, Hohagen, Bahro & Berger, 1994; Berger & Riemann, 1993; Lauer, Riemann, Wiegand & Berger, 1991; Kupfer et al., 1986; Berger, Doerr, Lund, Bronisch & Zerssen, 1982; Kupfer, 1976; Kupfer & Foster, 1972). With respect to REM variables, shortened REM latency was initially proposed to represent the most specific biological marker of depression (Kupfer et al., 1986; Kupfer, 1976; Kupfer & Foster, 1972), while following studies indicated increased REM density as a more specific sleep marker of the disorder (Riemann et al., 1994; Berger & Riemann, 1993; Lauer et al., 1991).

After these pioneer studies, PSG research in major depression continued producing a rich literature, which however is limited by many conflicting findings, probably due to modest sample sizes and methodological variance between studies (Swanson, Hoffmann & Armitage, 2010). Indeed, confounding factors such as sex, age, comorbidity, or medication intake have frequently not been well controlled (Newell, Mairesse, Verbanck & Neu, 2012). A recent meta-analysis of 46 studies reporting PSG recordings in patients with depression compared to control groups aimed at overpassing these limitations by accounting for sampling error across studies and by aggregating data from multiple samples, thus providing a greater statistical power (Pillai, Kalmbach & Ciesla, 2011). The results confirmed REM density as a possible biological marker for the disorder: more specifically, the authors suggested that major depression may be related to a combination of diminished SWS duration and increased REM density. However, in this meta-analytic work the authors did not control whether patients suffered also from other psychopathological conditions commonly associated with depression, as anxiety disorders. Comorbidity being rather the rule than the exception in clinical settings, it is likely that many patients with depression present mixed clinical profiles. Thus, comorbidity may be a relevant factor to consider with respect to sleep physiology associated to distinct disorders.

PSG research in other mental disorders than major depression

While most research focused on depression, less consideration was given to other disorders, with few exceptions, such as a recent meta-analysis evaluating PSG studies in patients with schizophrenia (Chouinard, Poulin, Stip & Godbout, 2004). In this work, 20 studies were evaluated comparing 321 patients with schizophrenia without antipsychotic treatment at the time of sleep recording with 331 healthy controls. Results showed that patients presented with sleep alterations, as increased total time awake and shorter duration of stage 2 sleep during the night, even if never treated. Thus, sleep disruptions seem to be an intrinsic feature of schizophrenia. Disorders comorbidity was however not controlled or further evaluated in subgroup analyses. Moreover, apart from this relevant work on sleep in patients with schizophrenia, sleep characteristics associated with mental disorders different from major depression have been little investigated. Thus, the answer to the question whether sleep variables represent genetic/biological markers of distinct mental disorders is still not clear.

The previous meta-analysis: Benca et al. 1992

The most widely cited analysis which tested the specificity of sleep markers for mental disorders was performed by Benca and co-authors in a meta-analysis published in 1992 (Benca, Obermeyer, Thisted & Gillin, 1992). The authors quantitatively summarized the polysomnographic literature in mental disorders. Data for this meta-analysis included all studies published in English and listed in Index Medicus. The diagnoses of the patient samples were based on available standardized research diagnostic criteria and publications had to report the mean age of the groups. Moreover, the polysomnographic records had to be visually scored by standard criteria (i.e. Rechtschaffen & Kales, 1968). Finally, all patients had to be ill at the time of the study and drug free for at least 14 days before the sleep recordings, although exceptions were made for some studies in which patients had been drug-free for only 7 days. A total of 177 studies were found including data from 7151 patients and controls. The authors considered the following disorders: affective disorders (15 studies, 13 major depression and 2 dysthymic disorder), anxiety disorders (10 studies, 4 generalized anxiety disorder, 4 panic disorder, 1 obsessive compulsive disorder and 1 generalized anxiety disorders or phobias), alcoholism (6 studies), borderline personality disorder (4 studies), dementia (10 studies), eating disorders (8 studies, 6 bulimia and anorexia nervosa and 2 bulimia only), insomnia (7 studies), schizophrenia (12 studies), and narcolepsy (11 studies). The results showed that patients with affective disorders differed significantly from their corresponding healthy comparisons more often than did any other diagnostic category. Moreover, patients with affective disorders differed from healthy controls in all sleep variables considered (including total sleep time, sleep onset latency, sleep efficiency index, SWS duration, REM duration, REM latency, REM density, and other REM variables). Particularly, alterations of REM sleep like shortened REM latency occurred more frequently in patients with affective disorders than in any other psychopathological condition. Nevertheless, it was noted that a shortened REM latency was also associated with schizophrenia. In addition, alterations in any of the sleep variables were not specifically linked to single disorders, thus questioning the specificity of any sleep variable for a particular mental disorder. The single exception was a REM density increase found exclusively in affective disorders, although analyses for this sleep parameter were limited to only some of the disorders due to an insufficient number of studies.

This impressive work still represents the only effort made until now to summarize the biological aspects of sleep in different mental disorders. However, as a first work published around 20 years ago, it includes many limitations which might have affected the results. Specifically, Kupfer and Reynolds (1992) pointed out that the authors did not consider important interfering factors, such as family history of mental disorders in control subjects, different definitions of sleep variables in the studies (considered only for REM latency), subtypes of mental disorders (particularly bipolar depression and different anxiety disorders), studies with overlapping subjects, studies conducted on children, adolescents and elderly. Moreover, the sleep variables considered referred to either only one night or to the average of the nights recorded. As a consequence, no attempt was made to contrast a possible “first night effect”, which is the tendency for individuals to sleep worse during the first night of PSG, or “reverse first night effect”, which may be encountered in some patients with insomnia who sleep better because the maladaptive conditioning between the bed and poor sleep does not generalize to new environments (e.g. Hirscher et al., 2015).

Sleep disturbances as transdiagnostic and dimensional

The results of the meta-analysis from Benca and co-authors did not support the idea that disorder-specific sleep profiles could be observed through polysomnography. Based on the categorical approach to nosology and on the previous finding on REM sleep variable alterations in major depression, this idea was at the time of the publication supported by most sleep researchers. For this reason the findings of this pioneer meta-analysis were initially interpreted with caution and much attention was dedicated to methodological limitations which could have explained the unexpected results.

As in the last decades clinical and research interest in psychopathology focused on a better understanding of comorbidity and psychophysiological mechanisms shared between disorders, the results of the meta-analysis conducted from Benca and co-authors were reinterpreted on the basis of a different theoretical focus. Thus, it inspired modern theories to highlight transdiagnostic and dimensional aspects of sleep disturbances (Harvey et al., 2011). Sleep biology is reciprocally related with emotion regulation and its neurophysiological substrates. Moreover, genetics showed that genes associated with circadian rhythms have been also related to a range of mental disorders. In addition to this, dopaminergic and serotonergic function interplays with circadian and sleep biological mechanisms (Harvey et al., 2011). These new findings have been integrated in a new transdiagnostic and dimensional aetiological and clinical perspective for sleep problems in psychopathology: a) sleep difficulties play a relevant role in facilitating and maintaining mental disorders; b) transdiagnostic treatment of sleep disturbance could be standardly implied in clinical settings (Harvey et al., 2011). A recent study based on 220 patients with post-traumatic stress disorder and problematic alcohol use showed support for the sleep dimensional hypothesis. Presence of insomnia was found to be a transdiagnostic process linked with mental symptoms severity after controlling for emotion dysregulation and depressed mood (Fairholme, Nosen, Nillni, Schumacher, Tull, & Coeffey, 2013).

Sleep, considered as a fundamental operating state of the central nervous system, and occupying up to a third of the human life span, may be one of the most important basic dimensions of brain function and mental health (e.g. Regier et al., 2012; Harvey et al., 2011). Investigating PSG sleep variables in mental disorders has the potential to reveal neurobiological mechanisms of specific disorders (endophenotypic approach) and to evidence neural pathways cutting across diagnostic categories (dimensional approach).

The present meta-analysis

The aim of this meta-analysis was to evaluate nocturnal sleep alterations in mental disorders considering both the endophenotypic and the dimensional approaches. We focused on seven mental disorder categories based on DSM-IV classification (APA, 1994): i.e. affective, anxiety, eating, externalizing (attention-deficit/hyperactivity), pervasive developmental, personality (borderline and antisocial), and schizophrenia disorders. These categories were chosen based on the meta-analysis by Benca et al. (1992). In contrast to the previous work, disorders involving neurologic damage (i.e. dementia and narcolepsy) or substance abuse (i.e. alcoholism) were not considered because we sought to exclude disorders with a known neurobiological or substance-related etiology. Because a meta-analysis on PSG studies in insomnia disorder was recently published (Baglioni et al., 2014), we did not include insomnia disorder here. Instead, we decided to include additional categories such as externalizing and pervasive developmental disorders. Of these, for the first category, we searched only for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) because most sleep research in externalizing disorders focused on this condition (Owens et al., 2013). By adding these two further categories we aimed to address the role of sleep for developmental psychopathology, as this has been recently stressed (e.g. Sadeh, Tikotzky & Kahn, 2014). In line with this choice, within the personality disorders category, we searched also for antisocial personality disorder which is often related to history of ADHD in childhood (McCracken et al., 2000). While sleep problems have been classically linked with depression and anxiety, recent attention has addressed the role of sleep for aggression and impulsivity behaviors especially in adolescence and early adulthood (e.g. Gregory & Sadeh, 2012). Thus, we aimed to evaluate sleep physiology characteristics associated with several mental disorder categories covering various symptomatic profiles.

Methods

This meta-analysis followed MOOSE (Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines (Stroup et al., 2000: see Document S1 in the Supplemental Materials Online).

Study selection

We included nocturnal PSG studies evaluating the disorders noted above but did not consider diurnal studies because of limited data. For inclusion, studies were required to meet the following criteria:

Written in English, German, Italian, Spanish or French;

Diagnosis of mental disorders based on DSM-IV (APA, 1994) or ICD-10 (WHO, 2010);

Discontinuation of psychoactive medication for at least 1 week before and during the PSG examination;

Current episode of mental disorder at the time of the PSG recordings;

Inclusion of a healthy control group;

Report of PSG parameters as means and standard deviations;

Use of standard sleep scoring criteria (Iber et al., 2007; Rechtschaffen & Kales, 1968);

Exclusion of the first sleep laboratory night (i.e. adaptation night) from the analysis;

Report of the average age of participants;

Non-overlap of samples across studies.

We did not include data from unpublished studies in order to focus on those with the most rigorous research methodology subject to peer review.

Search Procedure

We used several strategies to identify our final study sample. First, we conducted computer-based searches using PubMed and PsychInfo according to the following keywords, capturing the title and the abstract: (polysomnogr* OR sleep architecture OR sleep recordings OR sleep stages) AND ((depress* OR affective OR unipolar OR bipolar OR mania) OR (GAD OR anxiety OR posttraumatic stress disorder OR PTSD OR phobia OR panic OR obsessive compulsive disorder OR OCD) OR (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder OR ADHD) OR (autis* OR Asperger OR pervasive developmental disorder) OR (border* OR borderline personality disorder) OR (eating OR anorex* OR bulim*) OR (antisocial personality disorder OR sociopath*) OR (schizophren*)). The search was conducted from January 1992, the date in which the earlier meta-analysis was published (Benca et al., 1992), to July 2015. The first author conducted the literature search in PsycInfo and the third author in PubMed, screening titles and abstracts of potentially eligible studies, collaborating whenever the inclusion or exclusion of one study was doubtful. The first and the second authors examined the full texts and extracted the data for the analyses.

Second, we expanded our search through identifying further studies from the references of the screened full-texts. Third, we contacted authors in the field to obtain further studies and, if needed, to obtain additional information, especially on potential overlaps between samples of different studies (see Acknowledgments).

Data extraction

The literature search lead to the selection of studies evaluating sleep efficiency index (SEI), sleep onset latency (SOL), total sleep time (TST), number of awakenings (NA), wake during the night (WAKE/WASO: we considered these 2 parameters together in one single variable due to the closeness of the 2 definitions and the interchangeable use of the 2 terms in our sample of studies. This decision was made in order to evaluate the largest number of studies possible), REM latency (REML), REM density (REMD), percentages of stage 1 (S1), stage 2 (S2), SWS (SWS), and REM (REM) sleep in the following seven categories of mental disorders:

Affective disorders

The analyses were first conducted for all affective disorders considered together. Afterwards, separate analyses were computed for each specific affective disorder for which a sufficient number of studies was available (at least 3 studies, see paragraphs below for more information on the methodological procedure). Considering our final sample of studies (see Results for details), separate analyses for specific affective disorders were possible to be conducted only for major depression and seasonal affective disorder.

Anxiety disorders

Similarly to affective disorders, first all studies were analyzed together. Afterwards, separate analyses were computed for specific anxiety disorders for which at least 3 studies were available. Analyses could be computed only for panic disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Eating disorders

All studies included in this category focused on anorexia nervosa.

Externalizing disorders

For this category we searched exclusively for Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Pervasive developmental disorders

All studies included in this category focused either on autistic disorder or Asperger syndrome. We considered these two disorders only separately to evaluate possible differences depending on the degree of cognitive impairment. Moreover, most studies selected for Asperger syndrome included also a group with autistic disorder and compared both patients’ samples with the same control group. This methodological issue was a further reason for analyzing the conditions only separately.

Personality disorders

For this category we focused on borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder. However, for this last condition, only 2 studies were selected in the final database, thus it was not evaluated in meta-analytic computations. Of note, by searching for antisocial personality disorder, we found a study evaluating polysomnography in patients with conduct disorder, which was added in the externalizing disorders category and described in this systematic review. However, this study was not considered in meta-analytic computations.

Schizophrenia

All subtypes were considered together, and no further analysis considering subtypes separately could be conducted due to a lack of a sufficient number of studies.

Table 1 and Table S1 give an overview of descriptive and clinical characteristics of the selected studies, such as demographic information, PSG characteristics, comorbidity in the patient samples, and past personal and family histories of mental disorders in the control samples.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| Disorder | N_studies | N_comparisons* | N_patients | N_controls | Age_range | F % | QA (mean ± sd) | QA (median) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective disorders | 43 | 55 | 1627 | 1217 | x< 18 yrs: 6 st. | 48.5 (patients) 44.3 (controls) |

8.56 ± 1.26 | 9 |

| 18 < x < 60 yrs: 29 st. | ||||||||

| x>60 yrs: 2 st. | ||||||||

| >18: 5 st; adolescents + adults: 1 st | ||||||||

| Major depression | 38 | 50 | 1524 | 1128 | x< 18 yrs: 6 st. | 44.9 (patients) 39.8 (controls) |

8.63 ± 1.15 | 8.5 |

| 18 < x < 60 yrs: 25 st. | ||||||||

| x>60 yrs: 2 st. | ||||||||

| >18: 4 st; adolescents + adults: 1 st | ||||||||

| Seasonal affective disorder | 3 | 3 | 55 | 41 | x< 18 yrs: 0 st. | 92.8 (patients) 92.8 (controls) |

7.33 ± 2.52 | 7 |

| 18 < x < 60 yrs: 2 st. | ||||||||

| x>60 yrs: 0 st. | ||||||||

| >18: 1 st | ||||||||

| Mixed unipolar and bipolar affective disorders | 2 | 2 | 48 | 48 | x< 18 yrs: 0 st. | 49.1 (patients) 55.5 (controls) |

9.00 ± 0.00 | 9 |

| 18 < x < 60 yrs: 2 st. | ||||||||

| x>60 yrs: 0 st. | ||||||||

| Anxiety disorders | 21 | 21 | 397 | 409 | x< 18 yrs: 1 st. 18 < x < 60 yrs: 19 st. x>60 yrs: 1 st. |

28.6 (patients) 51.3 (controls) |

8.57 ± 0.81 | 9 |

| Panic disorder | 4 | 4 | 60 | 50 | all 18 < x < 60 yrs | 61.6 (patients) 60.0 (controls) |

8.75 ± 0.50 | 9 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 13 | 13 | 255 | 195 | x< 18 yrs: 0 st. | 21.4 (patients) 33.0 (controls) |

8.46 ± 0.97 | 8 |

| 18 < x < 60 yrs: 12 st. | ||||||||

| x>60 yrs: 1 st. | ||||||||

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 1 | 1 | 22 | 22 | 18 < x < 60 yrs | 54.5 (patients) 45.5 (controls) |

Score=9 | |

| Specific phobia | 1 | 1 | 19 | 25 | 18 < x < 60 yrs | 47.4 (patients) 36.0 (controls) |

Score=9 | |

| Social phobia | 1 | 1 | 17 | 16 | 18 < x < 60 yrs | 17.6 (patients) 31.3 (controls) |

Score=8 | |

| Mixed anxiety disorders | 1 | 1 | 24 | 101 | < 18 yrs | 58.3 (patients) 46.5 (controls) |

Score=9 | |

| Eating disorders (only studies on anorexia nervosa were found) | 5 | 5 | 58 | 50 | < 18 yrs: 1 st. mixed adolescents and adults: 2 st.; young adults: 2 st |

100 (patients) 100 (controls) |

8.60 ± 1.52 | 8 |

| adults: 2 st | ||||||||

| Externalizing disorders• | 7 | 8.29 ± 0.95 | 8 | |||||

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 6 | 11 | 128 | 114 | x< 18 yrs: 4 st. 18 < x < 60 yrs: 2 st. x>60 yrs: 0 st. |

17.2 (patients) 28.1 (controls) |

8.50 ± 0.84 | 8 |

| Conduct disorder | 1 | No meta-analysis | 15 | 20 | < 18 yrs: 1 st. | 60.0 (patients) 55.0 (controls) |

Score=7 | |

| Pervasive developmental disorder• | 7 | 8.14±1 .57 | 8 | |||||

| Asperger syndrome | 3 | 3 | 34 | 38 | < 18 yrs: 1 st. | 20.6 (patients) 23.7 (controls) |

8.67 ± 2.08 | 8 |

| 18 < x < 60 yrs: 1 st. | ||||||||

| mixed adolescents and adults: 1 st. | ||||||||

| Autistic disorder | 6 | 7 | 103 | 71 | x< 18 yrs: 4st. | 13.6 (patients) 28.2 (controls) |

7.75 ± 1.26 | 8 |

| mixed adolescents and adults: 2 st. | ||||||||

| Personality disorders• | 6 | 8.5±1. 05 | 8.5 | |||||

| Borderline personality disorder | 5 | 5 | 89 | 85 | 18 < x < 60 yrs | 86.0 (patients) 84.7 (controls) |

8.4 ± 1.14 | 8 |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 1 | No meta-analysis | 19 | 11 | x< 18 yrs: 0 st. | 0.0 (patients) 27.5 (controls) |

Score=7 | |

| 18 < x < 60 yrs: 1 st. | ||||||||

| Schizophrenia disorder | 8 | 10 | 154 | 121 | < 18 yrs: 1 st. 18 < x < 60 yrs: 7 st. |

25.3 (patients) 22.8 (controls)° |

8.5 ± 1.41 | 8 |

Comparisons refer to the number of contrasts available from the studies selected (i.e., some studies were considered in more than one meta-analytic calculation if data were reported separately depending on one or more variables (e.g. mental disorders, gender, age, disorder duration, etc.).

Abbreviations: st=study/studies; yrs= years; QA= quality assessment; sd=standard deviation; F%=percentage of women.

Age range > 18 yrs: including both adults and elderly.

The study of Yang & Winkelman (2006) did not specify how many of patients/controls were females and for that reason it was not included in the calculation of the percentage of female patients with schizophrenia.

Seven main “mental disorders” categories were considered: affective, anxiety, eating, externalizing, pervasive developmental, personality and schizophrenia disorders. Nevertheless, only affective and anxiety disorders were considered also as whole categories, and not only for specific disorders. Indeed, the category “eating disorders” included studies evaluating anorexia nervosa only. No subcategory was found for “schizophrenia” disorder. For “externalizing” disorders only attentional deficit hyperactivity disorder was searched. Although keywords lead to one more study for this category focusing on conduct disorder, this could not be evaluated through meta-analytic computations. For “personality” disorders, borderline and antisocial disorders were searched. However, for this last only one study was selected, thus no analyses were performed. Finally, being 2 of the 3 studies with patients with Asperger syndrome including also a group of patients with autism and comparing both groups with the same control participants, no analyses for the category “pervasive developmental disorders” were performed.

In order to compute meta-analytic parameters for continuous outcome variables, means and standard deviations were used. Table 2 includes the number of studies for each mental disorder and each sleep variable available for use in meta-analytic computations. Most studies reported multiple sleep variables. Of note, for the duration of sleep stages, we considered only studies reporting the value as a percentage of total sleep time or sleep period time (i.e. we did not consider studies reporting the duration in minutes).

Table 2.

Number of comparisons which could be considered for meta-analytic calculations for each disorder and for each sleep variable

| SEI | SOL | TST | NA | WAKE/ WASO(%)1 |

REML | REMD | S1(%) | S2(%) | SWS(%) | REM(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sleep Efficiency Index |

Sleep Onset Latency |

Total Sleep Time |

Number of Awakenings |

Wake after sleep onset |

REM Latency |

REM Density |

Duration of stage 1 sleep |

Duration of stage 2 sleep |

Duration of Slow wave sleep |

Duration of REM sleep |

|

| Affective disorders (N=55)2 | 48 | 52 | 36 | 10 | 15 | 52 | 38 | 43 | 42 | 46 | 49 |

| MDD (N=50) | 44 | 48 | 33 | 10 | 15 | 47 | 35 | 40 | 39 | 43 | 45 |

| SAD (N=3) | 3 | 3 | 3 | / | / | 3 | / | / | / | / | 3 |

| Anxiety disorders3 (N=21) | 17 | 19 | 19 | 11 | 3 | 18 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 17 |

| PD (N=4) | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | / | 4 | / | / | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| PTSD (N=13) | 10 | 11 | 13 | 6 | / | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 11 |

| Eating disorders (N=5)4 | |||||||||||

| Anorexia nervosa (N=5) | 4 | 3 | 3 | / | / | 5 | / | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Externalizing disorders (N=6)5 | |||||||||||

| ADHD (N=6) | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | / | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Pervasive developmental disorders (N=10)6 | |||||||||||

| Asperger syndrome (N=3) | 3 | 3 | 3 | / | / | 3 | / | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Autistic disorder (N=7) | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Personality disorders (N=5)7 | |||||||||||

| Borderline personality disorder (N=5) | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Schizophrenia8 (N=10) | 10 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 |

/ indicates that none or less than 3 studies were available and for this reason no meta-analysis was conducted.

ABBREVIATIONS: MDD= Major Depression Disorder; SAD= Seasonal Affective Disorder; PD= Panic Disorder; PTSD= Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; AN= Anorexia Nervosa; ADHD= Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

WAKE and WASO generally refer to 2 different parameters: while WASO is generally defined as the difference between SPT and TST; WAKE is generally defined as the amount of wake stages as identified through polysomnographic recordings. Nevertheless, in our sample of studies the 2 parameters were often confused, with one study using the first definition for a parameter named WAKE or the other way round. Due to the closeness of the 2 definitions we decide to consider them in one single variable in order to evaluate the largest number of studies possible.

The group “affective disorders” included studies evaluating mixed affective disorders (e.g. mixed unipolar and bipolar affective disorders; this group was not further evaluated); studies focusing on major depression and studies focusing on seasonal affective disorders.

The group “anxiety disorders” included studies evaluating mixed anxiety disorders, social phobia, specific phobia, obsessive compulsive disorder, panic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Because of the number of studies available, only panic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder could be further evaluated in subgroup analyses.

The group “eating disorders” included studies focusing on anorexia nervosa.

The group “externalizing disorders” included 6 studies focusing on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and 1 study evaluating Conduct disorder. Thus, only the 6 studies analyzing PSG in patients with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder were considered in the meta-analysis.

The group “pervasive developmental disorders” included 7 studies in total, 2 of them included both a group of patients with autism and a group of patients with Asperger syndrome and compared them with the same control group. For this reason, we analyzed the two disorders separately and no analyses for the category “pervasive developmental disorders” were performed.

The group “personality disorders” included 5 studies focusing on Borderline Personality Disorder, and 1 study evaluating Antisocial Personality Disorder. Thus, only the 5 studies analyzing PSG in patients with Borderline Personality Disorder were considered in the meta-analyses.

For schizophrenia, no further subgroups were considered.

Quality assessment

For quality assessment, we referred to Section A of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Tool for Case-Control studies (Bradley & Hill, 2001). This section includes 6 questions aimed at assessing the validity of the results. Some questions were adapted for the specific aims of this meta-analysis.

Specifically, the following points were assessed:

Question 1) Did the results address a clear focused issue?

Question 2) Did the authors use an appropriate method to answer this question?

Question 3) Were the cases recruited in an acceptable way? Considering the aims of our work, were the patients assessed via a validated diagnostic interview or not (i.e. through validated questionnaires only)?

Question 4) Were the controls selected in an acceptable way? For our aims, were the controls matched for age and sex?

Question 5) Was the exposure accurately measured to minimize bias? For our work: 5.1.) Was an adaptation night recorded and excluded from the analyses or reported separately? 5.2) Were PSG scorers blind to group assignation? 5.3) Were measurement methods similar in cases and controls? 5.4) Were outcomes measured through standard PSG and scored through standard sleep scoring criteria?

Question 6) What confounding factors were assessed? For our work: 6.1) Were mental disorders comorbidity checked and reported? 6.2) Were interfering variables checked and reported (at least one of body mass index, education level, ethnicity, and socioeconomical status)? 6.3) Was the duration of the psychothropic drug free interval prior to PSG > or = 2 weeks?

In order to calculate a total score, for each of the 11 question, 1 was assigned when the answer was YES and 0 was assigned for NO, higher score (max=11) reflecting better methodological quality.

Statistical analyses: Meta-analytic calculations

In order to evaluate sleep continuity and architecture characteristics, as well as REM variables, related to each disorder, we grouped the 11 specific sleep variables in three main domains, namely:

Sleep continuity: defined by higher sleep efficiency, shorter sleep onset latency, and reduced number of awakenings;

Sleep depth: defined by shorter duration of stage 1 sleep, and longer duration of stage 2 and slow wave sleep;

REM pressure: defined by shorter REM latency, increased REM density, and longer duration of REM sleep.

Meta-analytic calculations for sleep domains were performed using the statistical software package R (http://www.R-project.org/). Effect sizes of single variables (Hedges’g with standard errors) were entered into one meta-analysis for each sleep domain, adjusted for direction (e.g. effect size multiplied by -1 for sleep latency in the sleep continuity domain). Each study could therefore contribute multiple times to the same domain, according to the number of variables the particular study reported in the domain. Robust Variance Estimation (RVE, R package “robumeta”) was used to cater for potentially statistically dependent effect sizes (e.g. Hedges, Tipton, & Johnson, 2010; Tanner-Smith & Tipton, 2014). For this method, results with degrees of freedom < 4 could indicate too few cases for reliable variance estimation. Based on the endophenotypic approach, each sleep variable could be specifically altered in one disorder only. Therefore, a separate meta-analysis for each mental disorder was also conducted considering single sleep variables. Two variables were not considered in sleep domains analyses, but only separately for analyses for each sleep variable: total sleep time, as already included in the definition of sleep efficiency, and WAKE/WASO, as the combination of these two variables together made it complicated to separate these variables for continuity vs architecture. Meta-analytic calculations for each sleep variable were performed using the software “Comprehensive Meta-Analysis” version 3 (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins & Rothstein, 2005).

For all analyses, significant results were considered with p<0.05, while marginally significant results were considered for p between 0.05 and 0.07.

Effect sizes were calculated as standardized means (Hedges’g). The random-effects model was used because of the considerable heterogeneity between studies (different populations, different settings, etc.). To test for heterogeneity, chi-squared tests and the I2 statistic derived from the chi-squared values were used (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins & Rothstein, 2009). Meta-analyses were performed when at least 3 studies were available. Possible sources of variability between the studies were controlled through meta-analytic subgroup analyses whenever a sufficient number of studies was available for the subgroup. Sex, age, and mental disorders comorbidity were considered for subgroup analysis. Before performing each meta-analysis, we identified possible outliers by exploring standardized residuals. Studies with standardized residuals > |3|were winsorized, i.e. residuals were reduced to = +/−3. Publication bias was assessed both graphically by using funnel plots and numerically by considering the classical safe-fail number for each significant result evidenced by main analyses.

Results

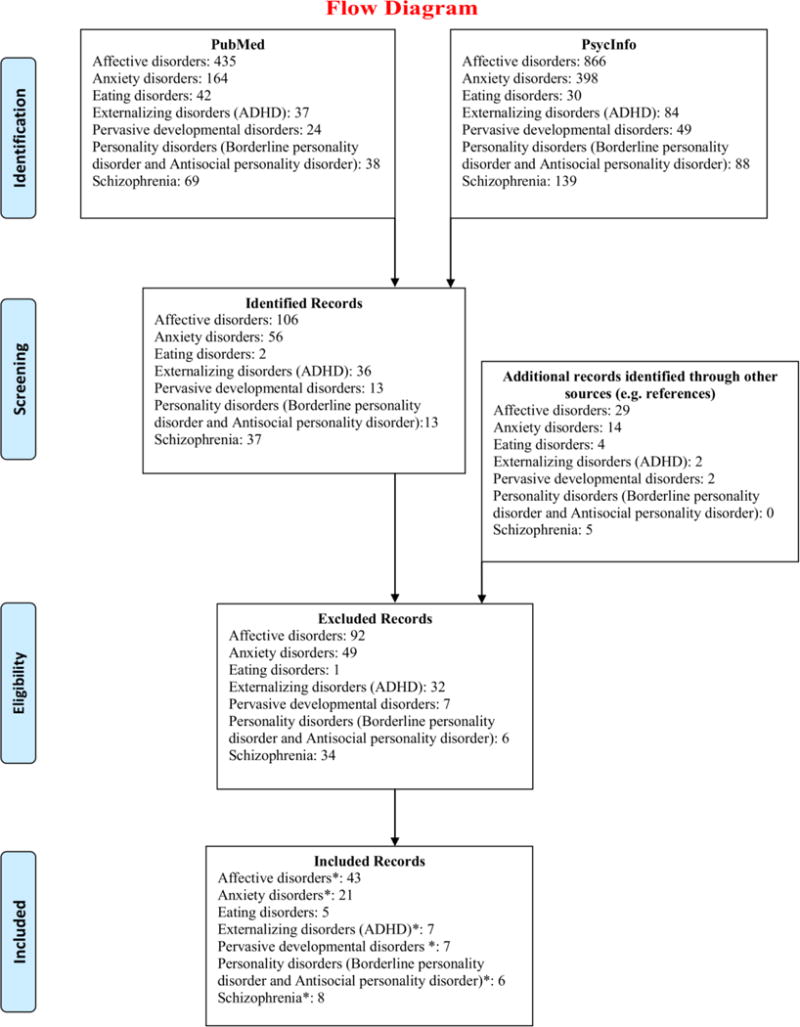

Figure 1 illustrates the search flow of the studies included in the present meta-analysis. The 91 studies (listed below in the list of references) selected (Table 1) corresponded to 114 different comparisons because some reported data separately for different groups such as women and men, age groups or duration of the disorder (see Table S1 for detailed information about each study). Of those, 55 comparisons referred to affective disorders, 50 evaluating major depression, 3 seasonal affective disorders, and 2 mixed unipolar and bipolar affective disorders. Separate analyses for specific affective disorders could be done only for major depression and seasonal affective disorder. Anxiety disorders were evaluated in 21 comparisons, of which 13 focused on PTSD, 4 on panic disorder, 1 on obsessive-compulsive disorder, 1 on specific phobia, 1 on social phobia, and 1 on mixed anxiety disorders. Consequently, separate analyses for specific anxiety disorders considered only panic disorder and PTSD. Five comparisons investigated polysomnographic characteristics of patients with eating disorders, all presenting anorexia nervosa. The externalizing disorders category included 6 comparisons for ADHD and 1 for conduct disorder. Seven studies were classified in pervasive developmental disorders, resulting in 3 comparisons for Asperger syndrome and 6 for autistic disorder. For personality disorders, we could find 5 comparisons with respect to borderline personality disorder and 1 for antisocial personality disorder. For lack of studies, conduct and antisocial personality disorders were not considered in meta-analytic computations. Finally, 8 studies, including 10 comparisons, were found for schizophrenia.

Figure 1.

Search flow with respect to each disorder.

*Six studies were considered for more than one disorder: 4 for both affective and anxiety disorders; 1 for affective and borderline personality disorder; and 1 for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Moreover for pervasive developmental disorders, studies focused either on autistic disorder or Asperger syndrome. Two studies included both a group with autistic disorder and a group with Asperger syndrome. In total, we could analyze 6 studies for autistic disorder and 3 for Asperger syndrome. In addition, searching for ‘antisocial personality disorder’, one study was found comparing subjects with conduct disorder with healthy controls, which was added to the list “externalizing disorders”. Finally, some of the included studies compared more than two groups, for example considering sex or age differences, which resulted in a total of 114 comparisons to analyze (from 91 studies). Please refer to Table S1 for detailed information for each included study.

The examination of the full texts led to the exclusion of 205 studies (some studies included more than one sample of patients – e.g. a group with major depression, a group with schizophrenia, and a control group –. For this reason the number of excluded comparisons according to the search flow is 221 and not 205). The excluded studies are listed below in the list of references.

Quality assessment

Appraisal of methodological quality of each study is reported in Table S2 and summarized for disorder categories in Table 1. Of note, Table S2 includes 97 studies as each disorder category was considered independently. All studies were estimated to address a clear focused issue and use an appropriate method to answer to the research’s questions (1 & 2). Eighty-one studies (of 91) based patients’ diagnoses on validated clinical interview, while 10 studies used validated questionnaires. Only 34 of 91 studies matched groups for age and sex. All studies excluded the first night from the analyses as this was an exclusion criterion of our meta-analysis, apart from one study which was included as the authors specifically reported that they tested that the exclusion of the first night from the analyses did not change the results (see Table S1 for more details). About half of the studies (49 of 91) specify that scorers were blind to group assignment, while the remaining 42 either not specify this information or conducted no blind scoring. Six studies of 91 followed slightly different procedural protocols for cases and controls. All included studies measured and scored PSG through standard sleep scoring criteria. Sixty-five studies provided detailed information on mental disorders comorbidity. Only 23 of 91 studies reported information on at least one possible interfering variable, such as body mass index, education level, ethnicity, and socioeconomical status. Finally, 71 of 91 studies required the patient group to be free of psychotropic drug medication for 2 weeks or more prior to PSG.

Global quality scores ranged between 5 and 11. Thirty-four studies scored 8; 24 scored 9; 13 scored 10; other 13 scored 7; 5 scored 11; 2 scored 6 and one study scored 5. As shown in Table 1, median scores for most disorder categories ranged between 8 and 9.

Meta-analyses computations

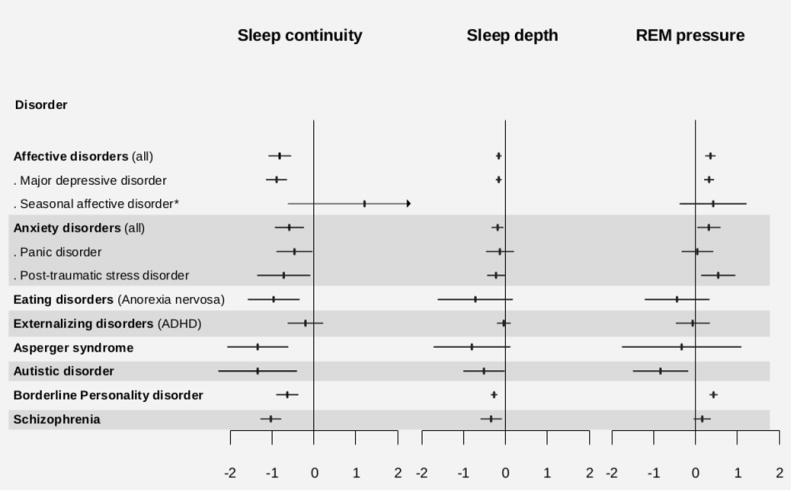

Results for sleep continuity, sleep depth and REM pressure are graphically summarized in Figure 2. Effect sizes are reported respectively in Table 3 for sleep continuity, Table 4 for sleep depth and Table 5 for REM pressure results. Table S3 reports number of participants, effect sizes and heterogeneity indices for computations conducted for separate sleep variables in each mental disorder.

Figure 2.

Graphical summary of the main results for sleep domains. Effect sizes and significance values are reported in Tables 3,4 and 5.

*No analyses for sleep depth in seasonal affective disorder (SAD) could be run due to lack of a sufficient number of studies.

Table 3.

Results for sleep continuity domain.

| SLEEP CONTINUITY | MAIN RESULTS | AGE < 18 yrs. | WOMEN | MEN | COMORBIDITY | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | |

| Affective disorders | −0,82 | 0,13 | −6,23 | 48,17 | 0,000 | −1,16 | 0,44 | −2,65 | 7,97 | 0,029 | −0,75 | 0,40 | −1,88 | 9,95 | 0,089 | −0,83 | 0,27 | −3,04 | 15,34 | 0,008 | −0,78 | 0,26 | −3,02 | 15,13 | 0,009 |

| Major depressive disorder | −0,90 | 0,12 | −7,26 | 44,26 | 0,000 | −1,16 | 0,44 | −2,65 | 7,97 | 0,029 | −1,15 | 0,21 | −5,53 | 7,81 | 0,001 | −0,83 | 0,27 | −3,04 | 15,34 | 0,008 | −0,78 | 0,26 | −3,02 | 15,13 | 0,009 |

| Seasonal affective disorder | 1,21 | 0,93 | 1,30 | 1,99 | 0,324 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Anxiety disorders | −0,59 | 0,17 | −3,43 | 17,80 | 0,003 | −0,92 | 0,41 | −2,22 | 6,07 | 0,068 | −0,58 | 0,24 | −2,45 | 1,96 | 0,136 | ||||||||||

| Panic diosrder | −0,47 | 0,21 | −2,17 | 2,85 | 0,123 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | −0,72 | 0,32 | −2,27 | 10,27 | 0,046 | −0,92 | 0,41 | −2,22 | 6,07 | 0,068 | |||||||||||||||

| Eating disorder | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anorexia nervosa | −0,96 | 0,31 | −3,10 | 2,74 | 0,060 | −0,96 | 0,31 | −3,10 | 2,74 | 0,060 | |||||||||||||||

| Externalizing disorders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Attentional deficit hyperactivity disorder | −0,20 | 0,21 | −0,97 | 5,89 | 0,372 | −0,15 | 0,17 | −0,88 | 4,09 | 0,429 | −0,24 | 0,25 | −0,96 | 4,05 | 0,389 | ||||||||||

| Pervasive developmental disorders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Asperger syndrome | −1,35 | 0,37 | −3,67 | 1,97 | 0,069 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Autistic disorder | −1,35 | 0,47 | −2,84 | 5,64 | 0,032 | −0,95 | 0,27 | −3,57 | 3,85 | 0,025 | −1,47 | 0,19 | −7,65 | 1,91 | 0,019 | ||||||||||

| Personality disorders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Borderline Personality disorder | −0,64 | 0,13 | −4,87 | 3,54 | 0,011 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Schizophrenia | −1,03 | 0,12 | −8,54 | 8,46 | 0,000 | −0,89 | 0,03 | −28,88 | 1,99 | 0,001 | −1,12 | 0,24 | −4,76 | 2,75 | 0,021 | ||||||||||

Abbreviations: ES= effect size (Hedges’g); SE= standard error; t=t-test; dfg=degrees of freedom. Significant results are evidenced in bold if dgf>or=4 (dgf<4 could indicate too few cases for the application of the robust variance estimation method). Marginally significant results (0.05–0.07) are evidenced in bold and italics if dgf> or =4.

Table 4.

Results for sleep depth domain.

| SLEEP DEPTH | MAIN RESULTS | AGE < 18 yrs. | WOMEN | MEN | COMORBIDITY | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | |

| Affective disorders | −0,16 | 0,03 | −4,60 | 38,82 | 0,000 | −0,11 | 0,06 | −1,74 | 8,01 | 0,121 | −0,13 | 0,07 | −1,73 | 7,71 | 0,124 | −0,19 | 0,10 | −2,00 | 9,76 | 0,074 | −0,13 | 0,05 | −2,32 | 12,89 | 0,038 |

| Major depressive disorder | −0,16 | 0,04 | −4,51 | 35,92 | 0,000 | −0,11 | 0,06 | −1,74 | 8,01 | 0,121 | −0,15 | 0,08 | −1,83 | 6,77 | 0,111 | −0,19 | 0,10 | −2,00 | 9,76 | 0,074 | −0,13 | 0,05 | −2,32 | 12,89 | 0,038 |

| Seasonal affective disorder | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anxiety disorders | −0,19 | 0,07 | −2,61 | 14,93 | 0,020 | −0,18 | 0,16 | −1,16 | 4,82 | 0,299 | −0,19 | 0,19 | −1,04 | 1,98 | 0,407 | ||||||||||

| Panic diosrder | −0,13 | 0,17 | −0,78 | 2,64 | 0,498 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | −0,23 | 0,11 | −2,11 | 8,63 | 0,066 | −0,18 | 0,16 | −1,16 | 4,82 | 0,299 | |||||||||||||||

| Eating disorder | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anorexia nervosa | −0,72 | 0,46 | −1,57 | 2,99 | 0,214 | −0,72 | 0,46 | −1,57 | 2,99 | 0,214 | |||||||||||||||

| Externalizing disorders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Attentional deficit hyperactivity disorder | −0,04 | 0,08 | −0,47 | 4,95 | 0,656 | 0,00 | 0,13 | −0,01 | 2,96 | 0,992 | −0,11 | 0,05 | −2,09 | 2,95 | 0,129 | ||||||||||

| Pervasive developmental disorders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Asperger syndrome | −0,80 | 0,47 | −1,72 | 2,00 | 0,228 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Autistic disorder | −0,51 | 0,25 | −2,05 | 5,99 | 0,086 | 0,07 | 0,22 | 0,34 | 3,95 | 0,754 | −0,82 | 0,31 | −2,66 | 2,00 | 0,117 | ||||||||||

| Personality disorders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Borderline Personality disorder | −0,27 | 0,04 | −6,53 | 3,93 | 0,003 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Schizophrenia | −0,34 | 0,13 | −2,65 | 8,42 | 0,028 | −0,13 | 0,31 | −0,42 | 1,89 | 0,720 | −0,57 | 0,22 | −2,64 | 2,94 | 0,079 | ||||||||||

Abbreviations: ES= effect size (Hedges’g); SE= standard error; t=t-test; dfg=degrees of freedom. Significant results are evidenced in bold if dgf>or=4 (dgf<4 could indicate too few cases for the application of the robust variance estimation method). Marginally significant results (0.05–0.07) are evidenced in bold and italics if dgf> or =4.

Table 5.

Results for REM pressure domain.

| REM PRESSURE | MAIN RESULTS | AGE < 18 yrs. | WOMEN | MEN | COMORBIDITY | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | ES | SE | t | dgf | p-Value | |

| Affective disorders | 0,35 | 0,06 | 5,79 | 43,92 | 0,000 | 0,16 | 0,13 | 1,20 | 7,16 | 0,267 | 0,22 | 0,17 | 1,32 | 7,89 | 0,225 | 0,42 | 0,10 | 4,11 | 13,48 | 0,001 | 0,09 | 0,06 | 1,50 | 14,03 | 0,157 |

| Major depressive disorder | 0,32 | 0,06 | 5,34 | 39,74 | 0,000 | 0,16 | 0,13 | 1,20 | 7,16 | 0,267 | 0,12 | 0,18 | 0,66 | 6,35 | 0,531 | 0,42 | 0,10 | 4,11 | 13,48 | 0,001 | 0,07 | 0,06 | 1,15 | 13,22 | 0,272 |

| Seasonal affective disorder | 0,42 | 0,41 | 1,03 | 1,79 | 0,422 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Anxiety disorders | 0,32 | 0,14 | 2,22 | 17,08 | 0,040 | 0,75 | 0,29 | 2,53 | 5,07 | 0,052 | −0,04 | 0,16 | −0,27 | 1,91 | 0,816 | ||||||||||

| Panic diosrder | 0,04 | 0,19 | 0,22 | 2,57 | 0,841 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 0,54 | 0,21 | 2,58 | 9,91 | 0,028 | 0,75 | 0,29 | 2,53 | 5,07 | 0,052 | |||||||||||||||

| Eating disorder | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anorexia nervosa | −0,44 | 0,39 | −1,13 | 3,76 | 0,326 | −0,44 | 0,39 | −1,13 | 3,76 | 0,326 | |||||||||||||||

| Externalizing disorders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Attentional deficit hyperactivity disorder | −0,07 | 0,21 | −0,33 | 4,97 | 0,752 | −0,03 | 0,33 | −0,08 | 2,99 | 0,942 | 0,09 | 0,24 | 0,38 | 2,96 | 0,728 | ||||||||||

| Pervasive developmental disorders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Asperger syndrome | −0,34 | 0,73 | −0,46 | 2,00 | 0,689 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Autistic disorder | −0,84 | 0,34 | −2,48 | 5,75 | 0,049 | 0,00 | 0,31 | 0,01 | 3,66 | 0,994 | −1,45 | 0,24 | −5,90 | 1,93 | 0,030 | ||||||||||

| Personality disorders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Borderline Personality disorder | 0,43 | 0,05 | 8,84 | 3,72 | 0,001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Schizophrenia | 0,16 | 0,10 | 1,51 | 8,16 | 0,169 | −0,25 | 0,06 | −4,02 | 1,94 | 0,060 | 0,06 | 0,10 | 0,66 | 2,94 | 0,559 | ||||||||||

Abbreviations: ES= effect size (Hedges’g); SE= standard error; t=t-test; dfg=degrees of freedom. Significant results are evidenced in bold if dgf>or=4 (dgf<4 could indicate too few cases for the application of the robust variance estimation method). Marginally significant results (0.05–0.07) are evidenced in bold and italics if dgf> or =4.

Sleep continuity disturbance were evidenced in all disorders, with the exception of seasonal affective disorder, panic disorder and ADHD. The result was marginally significant for eating disorder and Asperger syndrome, although this may be dependent on the small number of studies available for these categories (respectively N=5 and N=3). Indeed, degrees of freedoms were < 4 for both these categories. In addition to this, the significant result found for borderline personality disorder showed also degrees of freedom < 4, indicating that more studies are needed with respect to this condition. Analyses for each single variable evidenced some diversions from results for domains. Panic disorder was linked with poorer sleep efficiency, marginally significant longer sleep onset latency and shortened total sleep time compared to controls. Instead, no significant result was evidenced for ADHD in analyses for each sleep variable, similarly to sleep domains analyses. Seasonal affective disorder was associated only with marginally significant shortened total sleep time compared to controls. Finally, sleep onset latency was not statistically different between controls and patients with PTSD, anorexia nervosa, and borderline personality disorder.

Sleep depth was altered in affective, anxiety and schizophrenia disorders. Borderline personality disorder seems also to be associated with reduction of sleep depth, but degrees of freedom were < 4. Within categories, reduction of sleep depth was found in major depression and PTSD (although the result was only marginally significant), but not in panic disorders. Analyses for single sleep variables evidenced no alterations of SWS in patients with major depression, or more generally, in patients with affective disorders. Patients with anxiety disorders, and in particular PTSD, presented shortened SWS, but no alterations in duration of S1 and S2.

REM pressure was increased in affective, anxiety and autistic disorders. Borderline personality disorder seems also to be associated with increased REM pressure, but degrees of freedom were < 4. Within categories, enhanced REM sleep pressure was found in major depression and PTSD, but not in seasonal affective and panic disorders. Analyses for single sleep variables evidenced shortened REML in patients with anxiety disorders, and in particular PTSD, but no alterations in REMD and REM duration. Differently, patients with autism spent shorter time in REM compared to controls, but did not present alterations in REML nor REMD. Finally, patients with borderline personality disorder showed reduced REML compared to controls.

Affective disorders and major depression were associated with alterations in most variables compared to healthy controls (10 of 11), with the exception of SWS duration. Instead, no sleep alteration was observed in ADHD and seasonal affective disorder (apart from marginally significant shortened TST), although analyses for this last condition were limited. Within anxiety disorders, PTSD was associated with severe alterations of sleep continuity, sleep depth and REM variables, while panic disorder was characterized by poor sleep efficiency, latency and quantity only. Anorexia nervosa was associated with sleep discontinuity and lighter sleep, although this last result was only marginally significant. Within pervasive developmental disorders, Asperger syndrome was not associated with alterations of sleep architecture and REM, while autistic patients spent reduced time in REM sleep. Borderline personality disorder was linked with sleep discontinuity and shorter REM latency. Nevertheless, neither patients with anorexia nervosa nor with borderline personality disorder spent more time to fall asleep than controls. Finally, schizophrenia was associated with alteration of sleep continuity, sleep architecture and longer REM latency.

Sample sizes varied relevantly depending on disorder and sleep variable. The largest sample available for calculations related to REM latency for affective disorders included 1597 patients and 1178 controls. Instead, analyses for Asperger syndrome (34 patients vs 24 controls) included the smallest sample size. Moreover, analyses for eating and autistic disorders also referred to small sample sizes (for details see Table S3). Of note, because of lack of sufficient number of studies, we could not run the analyses for number of awakenings in seasonal affective disorder, anorexia nervosa, and Asperger syndrome; for total time awake at night in seasonal affective disorder, panic disorder, PTSD, anorexia nervosa and Asperger syndrome; for REM density in seasonal affective disorder, panic disorder, anorexia nervosa, ADHD, and Asperger syndrome; for duration of stage 1 sleep in panic disorder; and for duration of stage 2 and slow-wave sleep for seasonal affective disorder.

Subgroup analyses

Sex

Analyses were repeated considering only those studies including exclusively women or men or reporting data separately for the two sexes. Results are reported in detail in Tables 3,4,5 and S3. Analyses for women were possible for affective disorders, depression, and anorexia nervosa. Of note, for this last disorder results of the subgroup analyses were identical to the main analyses as all included studies focused exclusively on female samples. Male samples with affective disorders, depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD, and schizophrenia were considered. Of note, within affective disorders, studies reporting data for men focused all on major depression, and, similarly, within anxiety disorders, studies reporting data for men focused all on PTSD.

With respect to depression, sleep continuity and depth, as well as REM pressure were all altered in male patients compared to controls, while in female samples only sleep continuity was found to be disturbed. Similarly, shorter sleep time and increased time awake during the night were found only in male samples with depression. REM sleep variables (REM latency, REM density and REM sleep duration) were all altered only in men with depression, and not in women, for whom only a marginally significant increased REMD was noted. Instead, women, but not men, with depression spent longer time in stage 1 sleep than controls.

Sleep depth was no longer reduced in patients with PTSD and schizophrenia, when focusing only on male populations. Enhanced sleep onset latency was observed in men with PTSD. Longer REM sleep duration was found in men with schizophrenia compared to controls. REM latency was, instead, no longer shorter than controls in male patients with schizophrenia disorders.

Age

To evaluate sleep changes during the life span in the mental disorders considered, the analyses were repeated wherever possible categorizing the studies in 3 groups: < 18/19 years: children and/or adolescents; between 18/19 and 60 years: working age adults; > 60 years: elderly. The working age adults group was evaluated in the majority of the studies, thus, the results related to this age group did not differ substantially from the main results.

Because of lack of sufficient data, we could not run analyses separately for children (< 13 yrs.) vs adolescents (13–18/19 yrs.). Indeed, 17 of 91 studies reported data on pediatric patients, seven of those included young patients with major depression, 1 with anorexia nervosa, 4 with ADHD, 1 with Asperger syndrome, 3 with autistic disorder, and 1 with schizophrenia. Age in the seven studies for major depression ranged between 7 and 18 yrs. One study did not report the age range, but only information on mean (15 yrs.). One study reported data separately for children aged less than 13 yrs. and adolescents (13–17 yrs.). One study included female patients with anorexia nervosa aged between 10 and 17 yrs. All other studies in this category focused on samples of mixed adolescents and young adults. ADHD studies conducted on pediatric samples included age ranges between 5 and 15 yrs. In 1 study including children with autistic disorder, age range was not reported, but only information on mean age (5 yrs.). The other studies focusing on pediatric patients with autistic disorder reported age ranges between 5 and 19 yrs. (including the only study for Asperger syndrome). Finally, one study included patients with schizophrenia aged between 13 and 19 yrs. For detailed information, refer to Table S1.

Separate analyses for the pediatric groups are presented in detail in Tables 3,4,5 and S3. Children and/or adolescents with major depression, presented, in comparison with the main results, only marginally significant poorer sleep continuity compared to controls, but no alterations of sleep depth and REM sleep pressure. Considering specific sleep variables, we found no change in total sleep time, REMD, and duration of S1 and REM sleep compared to controls. Moreover, duration of REML was only marginally shortened compared to healthy controls. Children with autism presented poorer sleep continuity compared to controls, but no alterations in sleep depth and REM pressure. Although these results in sleep domain analyses are limited by degrees of freedom < 4, the same profile was observed considering analyses for each sleep variable. As for main analyses, no significant result was found for ADHD.

Separate analyses for the elderly group were possible to be conducted only for major depression. Compared to main results, findings for elderly individuals with depression, indicated only a marginally significant increased REM density, and no longer altered duration of stages 1 and 2.

Comorbidity excluded

In this subgroup analyses we focused exclusively on studies which carefully excluded all possible mental comorbidities, thus, evaluated specific groups of patients presenting only one diagnosis. We could run these analyses for affective, anxiety, autistic, schizophrenia disorders, depression and ADHD. Of note, within the category of affective disorders, all studies including patients with only one diagnosis referred to major depression. Results are shown in Tables 3,4,5 and S3.

In the absence of comorbidities, major depression was no longer associated with increased REM sleep pressure. Considering each variable separately, results for REM latency, and REM duration showed no significance. S1 duration was also not impaired. Similarly, anxiety disorders without comorbidities were no longer associated with alterations in sleep domains. With respect to each sleep variable, we could observe in patients with anxiety disorders, only poor sleep efficiency and shortened total sleep time. Patients with autism presented enhanced REM latency compared to controls. Of note, REMD could not be calculated for anxiety and autistic disorders. Considering specific sleep variables, REML and SWS duration were no longer shortened in patients with schizophrenia.

Publication bias

Fifty-four funnel plots were visually inspected and related fail-safe classical numbers were calculated for the corresponding significant findings. Summarizing, plots showed few asymmetries, and smaller fail-safe numbers indicating higher publication bias risk were found mostly in association with small study samples. Plots and computations are reported in detail in Document S2.

Discussion

This meta-analysis investigated polysomnographic sleep in several mental disorders and identified both transdiagnostic and disorder-specific sleep alterations. Sleep continuity disturbances cut across current diagnostic entities and were found in all investigated disorders, with the exception of ADHD and seasonal affective disorder. Similarly to Benca et al. (1992), we found that no single sleep variable alteration was specific for one single disorder. Nevertheless no two conditions had the same sleep profile. Sleep depth and REM sleep pressure disturbances were altered in a smaller number of disorders and occurred rarely in a single condition in the absence of comorbidities. For example, even sleep variables that had previously been considered to be related to depression, such as REM latency or duration, were not significantly altered in depression without comorbidity. Sleep architecture and REM sleep variables may be associated with neurobiological pathways underlying different alterations of emotional and cognitive processes, thus, leading to distinct symptoms associations. These results suggest that constellations of sleep alterations may define distinct disorders better than alterations in one single sleep variable.

Sleep and hyperarousal as dimensions for mental health

Findings support the notion of transdiagnostic disruptions of sleep continuity, based on physiological (PSG) data. This implies that the neurobiological balance between arousal and de-arousal is disturbed in most mental disorders and very likely represents a basic dimension for brain function and mental health. Clinically, insomnia, the most prevalent sleep continuity disorder, is known to be highly comorbid with mental and somatic disorders and to increase the risk of some of them, as for example major depression (Baglioni et al., 2011), suicidal behaviors (Biøngaard, Bjerkeset, Romundstad & Gunnel, 2011) and cardiovascular disease (Laugsand, Strand, Platou, Vatten & Janszky, 2013). While classically seen as a predominantly psychological disorder, Riemann et al. (2010; 2012; 2015) pointed out that insomnia is characterized, beyond the better known cognitive/behavioral symptoms, by deviations of neuroendocrine and neuroimmunological variables, as well as electro- and neurophysiological, and functional alterations of the brain, all related to increased levels of psychophysiological arousal. A better understanding of the neurobiological aspects of insomnia may help to identify relevant pathophysiological pathways not only to insomnia but to virtually all mental disorders.

Sleep neural pathways are closely connected and in part overlap with neural pathways regulating affect, cognition and other important brain functions. Sleep can be studied across multiple units of analysis, including genetics, neurophysiology, neurocircuitry, epidemiology, and psychology. The strict categorical approach in psychopathology underestimates the reciprocal influences of neuropsychobiological mechanisms. Comorbidity is indeed the rule and not the exception in mental disorders, which makes it important to spread the focus from specific disorders to psychobiological mechanisms which cut across mental disorders. A dimensional approach to sleep research is in line with the new approach in psychopathology aiming at identifying basic dimensions that cut across diagnostic categories, which should bypass the limitations of the categorical approach embedded in major diagnostic systems (e.g. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, ICD-10, World Health Organization, WHO, 2010; and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-IV, American Psychiatric Association, APA, 1994). These limitations mainly relate to high rates of comorbidity and the neglect of symptoms not included in the primary diagnosis. Major attention to basic dimensions of psychopathology, such as psychomotor activity, mood, anxiety, cognition, suicidal ideation, psychotic symptoms, and sleep-wake functioning, informs the latest revision of DSM (Kupfer, Kuhl & Regier, 2013). DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, APA, 2013) follows a new approach, combining categorical and dimensional measurement (Kupfer et al., 2013; Regier et al., 2012). Nevertheless, a great amount of work is necessary to understand which dimensions are crucial for brain and mental health. To this end, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) proposed the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) Project (Morris, Rumsey & Cuthbert, 2014; Cuthbert & Kozak, 2013; Sanislow et al., 2010) to identify basic dimensions of brain/mind disorders to be studied across multiple units of analysis, from genes to neural circuits to behaviors. Our results suggest that sleep could be investigated within the RDoC concept as a likely basic dimension in mental health.

Further longitudinal studies should evaluate the causal sequences between sleep alterations and changes in relevant aspects of mental health functioning. In particular, it should be better understood the causal interaction between disruption of NREM and REM sleep variables with reduced performance in cognitive daily tasks or alteration of emotional processes, such as heightened emotional reactivity or difficulties in regulating affective responses. Indeed, reduction of sleep depth and increased REM sleep pressure were related to disorders comorbidity. Thus, diverse constellations of sleep architecture and REM sleep alterations may underline specific comorbidities in psychopathology and clarify why some disorders often present together.

Sleep in each mental disorder category

Affective disorders

Most PSG studies focused on major depression. In this meta-analysis we found that major depression was associated with the most severe sleep continuity, sleep depth and REM sleep pressure alterations; in contrast seasonal affective disorder was associated with no alteration in any sleep variable. No analyses could be conducted for bipolar disorder for absence of studies. While Benca et al. (1992) found reduced SWS duration in depression, a result which was confirmed also by a more recent meta-analytic work (Pillai et al., 2011), our study showed no reduction in SWS duration in this group of patients. The different result may depend on procedural differences, i.e. in our study we did not consider data from first PSG night in order to control for the so-called first-night effect (e.g. Hirscher et al., 2015). Slow Wave Sleep disruption could be more evident in patients with major depression in the first night in the laboratory as a result of adaptation to the new environment, more than being a specific feature of the disorder. Future studies should, however, be conducted to assess better this finding, for example through the application of more complex EEG measures such as power spectral analysis, cyclic alternating patterns, or event-related potentials. Subgroup analyses for sex showed more severe sleep impairment in male samples compared to female samples. This may indicate either biological sex differences in the disorder or social differences. For example, men may seek help only when the disorder is severe, while women may seek help earlier. Thusmajor attention should be dedicated to sex differences in future PSG research. When considering only young patients aged less than 18 years old, results showed a slight disruption of sleep continuity in those with depression compared to controls, while no alteration in sleep depth and REM sleep pressure was observed. As sleep architecture and REM variables are related with cognitive and emotional functioning, this result may indicate that sleep disturbances in childhood are less severe and may be associated with better clinical outcome. Because of the limited literature, this can only be said in a speculative way. However, potential clinical implications are so critical, which strongly suggests future PSG research to better explain the role of physiological changes in sleep during development. Future PSG research should be conducted to assess sleep in well-defined samples of children (aged < 13 years) and teens (13–19 years) with depression in controlled studies.

REM variables are strongly altered in major depression, being the only disorder associated with alteration in all three REM variables included (REM latency, REM density and REM sleep duration). Subgroup analyses focusing on only those studies which carefully excluded for mental disorders comorbidity, however, showed that in patients with depression without comorbidity REM latency and REM duration were not altered anymore. In contrast, increased REM density seems to be characteristics of the disorder even when presenting without any comorbidity. Consistent with early theories of depression (see Palagini, Baglioni, Ciapparelli, Gemignani, & Riemann, 2013) and pharmacological studies in healthy subjects (e.g. Nissen et al., 2006), central cholinergic activity and supersensitivity, responsible for the generation of rapid eye movements, may be excessively increased in depression and may represent a relevant neurobiological factor in the regulation of affect. The association between REM sleep variables and affect regulation was evidenced also by neuroimaging studies (van der Helm et al., 2011; Nofzinger et al., 2004). Furthermore, increased REM activity and time are related with suicidal behaviors in individuals with depression (Sabo, Reynolds, Kupfer & Berman, 1991) and in psychotic patients (Keshavan et al., 1994). It could be possible that changes in REM density may precede the onset of a major depression episode by triggering aspects of the emotional functioning. It would be of great interest to investigate whether these possible changes are genetically determined, i.e. they are present from childhood, or precipitate a first depressive episode and persist after the resolution of the episode or are limited to the episode, i.e. are state-dependent. New studies combining physiological (e.g. use of power spectral analysis or neuroimagining techniques) and behavioral (e.g. measures of emotional reactivity or regulation) approaches in patients with mental disorders and healthy controls should clarify the role of REM density for emotional processes.

Anxiety disorders