Abstract

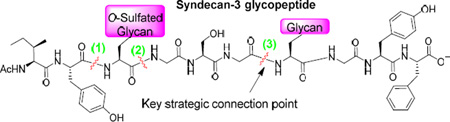

Proteoglycans play critical roles in many biological events. Due to their structural complexities, strategies towards synthesis of this class of glycopeptides bearing well-defined glycan chains are urgently needed. In this work, we give the full account of the synthesis of syndecan-3 glycopeptide (53–62) containing two different heparan sulfate chains. For assembly of glycans, a convergent 3+2+3 approach was developed producing two different octasaccharide amino acid cassettes, which were utilized towards syndecan-3 glycopeptides. The glycopeptides presented many obstacles for post-glycosylation manipulation, peptide elongation, and deprotection. Following screening of multiple synthetic sequences, a successful strategy was finally established by constructing partially deprotected single glycan chain containing glycopeptides first, followed by coupling of the glycan-bearing fragments and cleavage of the acyl protecting groups.

Keywords: Carbohydrates, Glycopeptides, Glycosylation, Protecting groups, Synthesis design

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Many naturally existing proteins contain glycan chains due to post-translational modifications.1–2 Glycans can have broad effects on the parent peptides and proteins, ranging from tertiary structure stabilization, enhanced stability against proteolysis, to altered physiochemical properties and biological functions.2–4 As the expression of glycans is not directly controlled by genes, glycoproteins and glycopeptides isolated from nature often exist as a heterogeneous mixture containing various glycans attached to the same peptide/protein backbone. Therefore, to decipher the structure and activity relationship, it is critical that glycoproteins and glycopeptides bearing homogeneous glycan chains can be synthesized.

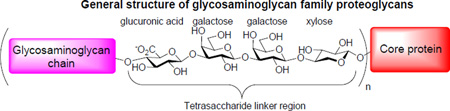

Structurally, native glycoproteins are classified into two major types: N-glycans and O-glycans.2,5 In N-glycans, carbohydrate residues are covalently linked to an asparagine residue in the protein backbone through an N-acetyl glucosamine. O-glycans can be further divided into two main classes, i.e., the mucin type and the glycosaminoglycan family proteoglycans. The mucin type O-glycans contain an N-acetyl galactosamine linkage to serine or threonine, while the proteoglycan family glycopeptides share the general structure of glycosaminoglycan chains connected to a serine of the core protein typically through a tetrasaccharide linker consisted of glucuronic acid-β-1,3-galactose-β-1,3-galactose-β-1,4-xylose.6 Many creative chemical7–23 and chemoenzymatic24–30 methods have been developed to synthesize glycopeptides bearing sophisticated structures of N-glycans and mucin type O-glycans.31–38 Great successes have been achieved in these areas with molecules approaching the sizes and complexities of native glycoproteins produced via total synthesis.7–9 In comparison, methodologies for the preparation of glycopeptides carrying homogenous glycosaminoglycan are under developed. Much synthetic work related to proteoglycans has been on the synthesis of glycosaminoglycan oligosaccharides39–44,45–68 and the tetrasaccharide linker.69–79 Recently, we have begun to develop a strategy towards the proteoglycan family glycopeptides with syndecan-3 as the target.80 With the highly complex structure, many obstacles were encountered during the synthesis. Herein, we provide the full details for the successful synthesis of syndecan-3 (53–62) glycopeptides bearing two different heparan sulfate glycan chains.

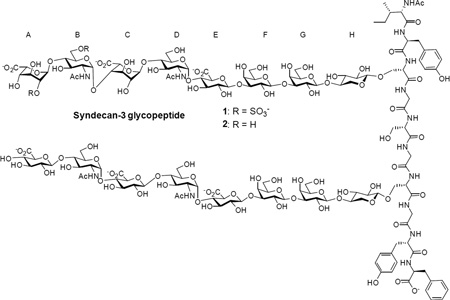

Syndecan-3 is a transmembrane proteoglycan highly expressed in neural cells with its extracellular domain bearing heparan sulfate chains.6,81–82 Syndecan-3 is involved in a wide range of biological events such as cell-cell interaction,83 skeletal muscle growth and repair,84–87 and viral infection.88 Our synthetic targets are syndecan-3 extracellular domain glycopeptides 1 and 2 (corresponding to amino acids 53–62),89–90 which contain typical structural features of heparan sulfate proteoglycans including different heparan sulfate chains, the tetrasaccharide linkers, 2-O sulfation, 6-O sulfation, glucosamine αlinked to both glucuronic acid and iduronic acid, and N-acetylation.

Results and Discussion

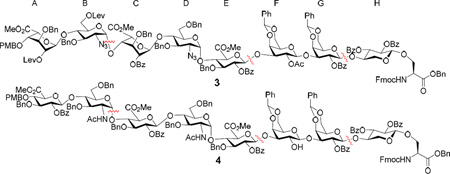

Synthetic design and preparation of iduronic acid containing octasaccharide serine cassette 3

In order to prepare syndecan-3 glycopeptides, we adapted a cassette approach91 where iduronic acid containing octasaccharide serine cassette 3 and glucuronic acid containing 4 were utilized as cassettes for glycopeptide assembly. Due to the large sizes of the glycan chains in cassettes 3 and 4, we aim to develop a convergent route where oligosaccharide modules were synthesized and then joined to improve the overall synthetic efficiency.

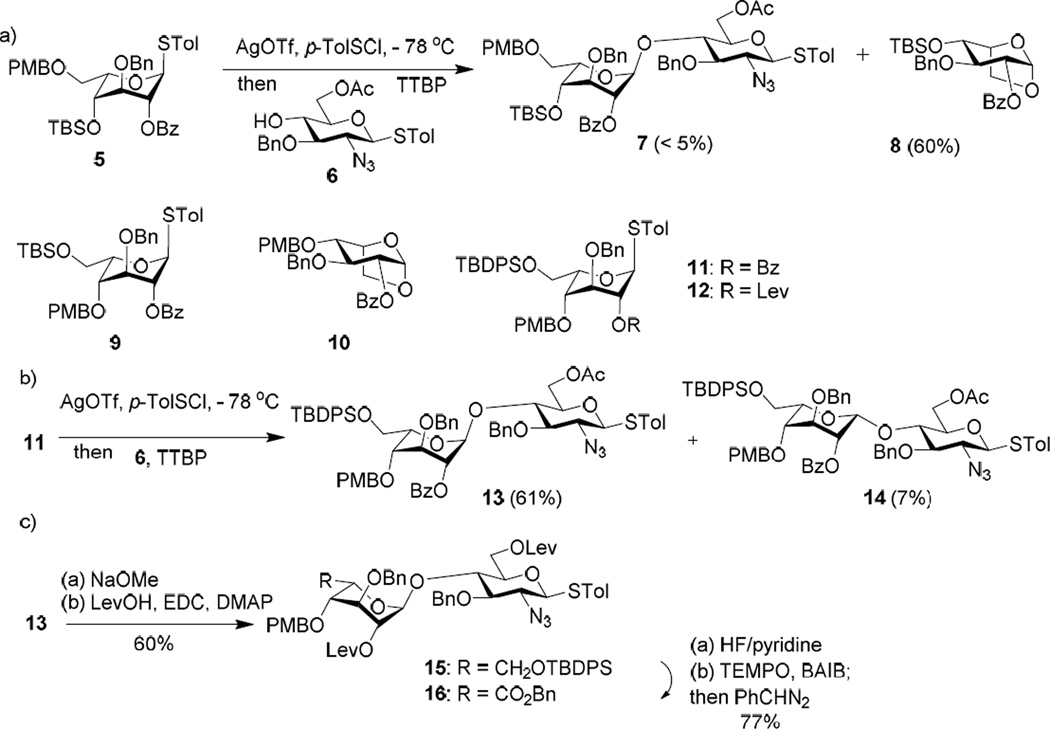

Our initial design towards the serine derivative 3 was a 2+3+2+1 approach making the strategic disconnections of the octasaccharide at the B/C, E/F and G/H linkages. Although uronic acid thioglycosyl and trichloroacetimidate donors have been successfully utilized in glycosaminoglycan synthesis,92–93 in our experience, the corresponding hexose donors tend to give higher glycosylation yields.94 Thus, idose and glucose building blocks were used for constructing the glycosyl linkages, which would be followed by oxidation to uronic acids.95 The synthesis started from the preparation of the non-reducing end AB disaccharide by reacting donor 5 with acceptor 6.53 The glycosylation reaction was initiated by pre-activating idosyl donor 5 with p-TolSOTf,96 which was formed in situ through reaction of AgOTf and p-TolSCl at −78 °C (Scheme 1a). Following complete activation of the donor 5, acceptor 6 was added to the reaction mixture together with a non-nucleophilic base tri-tbutyl-pyrimidine (TTBP).97 Unfortunately, no desired disaccharide 7 was obtained. Analysis of the reaction mixture showed that most acceptor 6 was recovered (~ 63%) with the major side product as the 1,6-anhydro idoside 8 (~ 60%). The 1,6-linkage in 8 was presumably formed by nucleophilic attack of the anomeric center upon donor activation by 6-O due to the electron rich 6-O-p-methoxybenzyl (PMB) moiety. To address this problem, we tested donor 9 bearing the 6-O-tbutyldimethylsilyl (TBS) group in reaction with acceptor 6, which gave the 1,6-anhydro sugar 10 as the major side product. To reduce the remote participation by the 6-O moiety, the tbutyldiphenylsilyl (TBDPS) group was examined next as the protective group (donor 11). Gratifyingly, the TBDPS ether was sufficiently bulky, which effectively suppressed the 1,6-anydro sugar formation leading to 61% yield of the desired disaccharide 13 along with 7% of the epimer 14 (Scheme 1b). The Ac and Bz groups in 13 were then exchanged with levulinate (Lev) as sites for future O-sulfation producing disaccharide donor 15 (Scheme 1c). The TBDPS moiety from 15 was removed and the free hydroxyl group oxidized by 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO) and [bis(acetoxy)iodo]benzene (BAIB)92 followed by benzyl ester formation with phenyl diazomethane95 (donor 16).

Scheme 1.

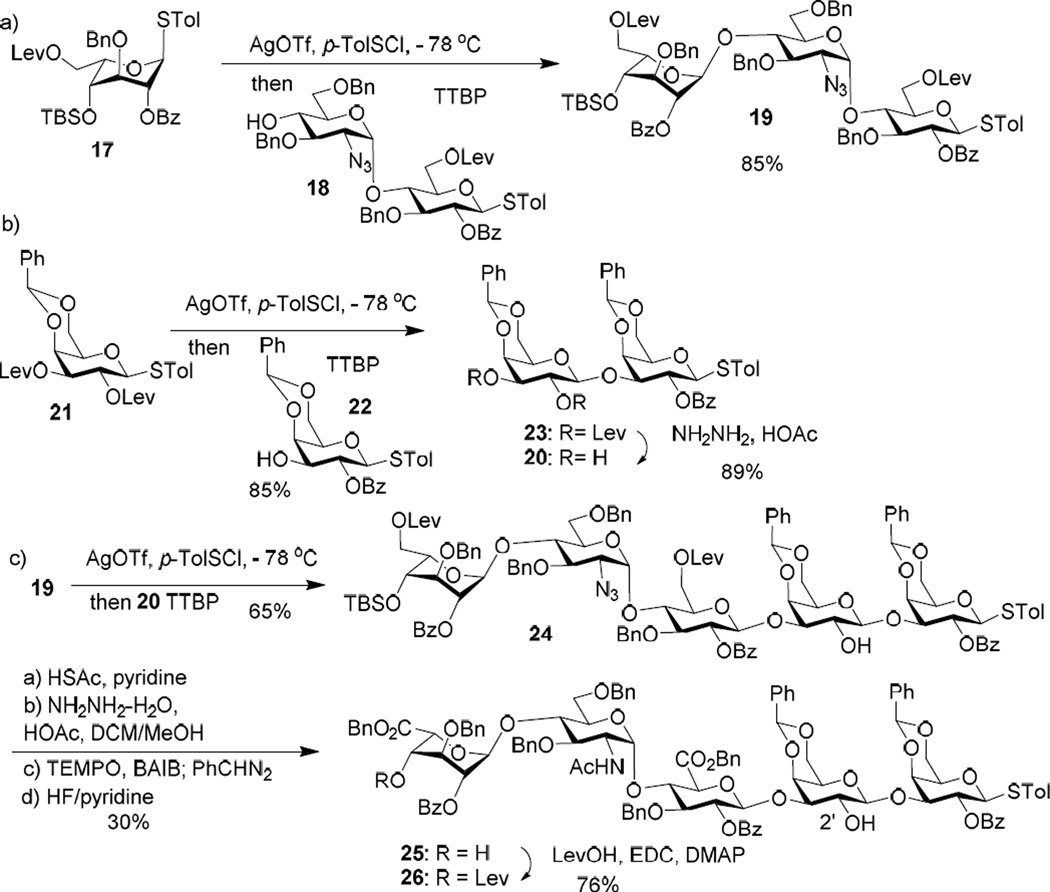

With the AB module in hand, we moved onto the preparation of the CDE and FG modules. The α-linked disaccharide acceptor 1853 was successfully glycosylated by the idosyl donor 17 producing CDE trisaccharide 19 in 85% yield (Scheme 2a). The FG di-galactoside 20 was synthesized by reacting di-Lev galactosyl donor 2198 with galactoside 2298 followed by hydrazine acetate treatment to selectively remove the Lev groups (Scheme 2b). Trisaccharide 19 was then joined with di-galactoside acceptor 20 forming CDEFG pentasaccharide module 24 in 65% yield (Scheme 2c). The azide moiety in 24 was converted to acetamide and the product was further transformed to acceptor 25. The non-reducing end hydroxyl group of 25 was protected with Lev generating CDEFG pentasaccharide donor 26. The hindered 2’-OH in 25 did not undergo acylation under the reaction condition as it was flanked by two bulky glycan rings.

Scheme 2.

Merging the AB and CDEFG modules turned out to be highly problematic. Reaction of donor 16 with pentasaccharide acceptor 25 failed to lead to any desired heptasaccharide 27 (Scheme 3a). To test the possibilities of acetamide99 or the electron withdrawing benzyl ester groups negatively impacting glycosylation, donor 15 and idose/azide bearing thioglycosyl trisaccharide acceptor 28 were examined, which did not lead to successful glycosylation either. Several side products due to acceptor activation were observed from these reactions. To avoid acceptor activation, hexasaccharide acceptor 30 was prepared by reacting 26 with xylosyl serine 29 followed by Lev removal (Scheme 3b). Although the yield was not high (~20%), sufficient quantity of hexasaccharide 30 was acquired. However, reaction of 16 with 30 again did not provide the desired octasaccharide 31 (Scheme 3c). These unsuccessful attempts suggest that it is difficult to form the BC glycosyl linkage using oligosaccharide building blocks.

Scheme 3.

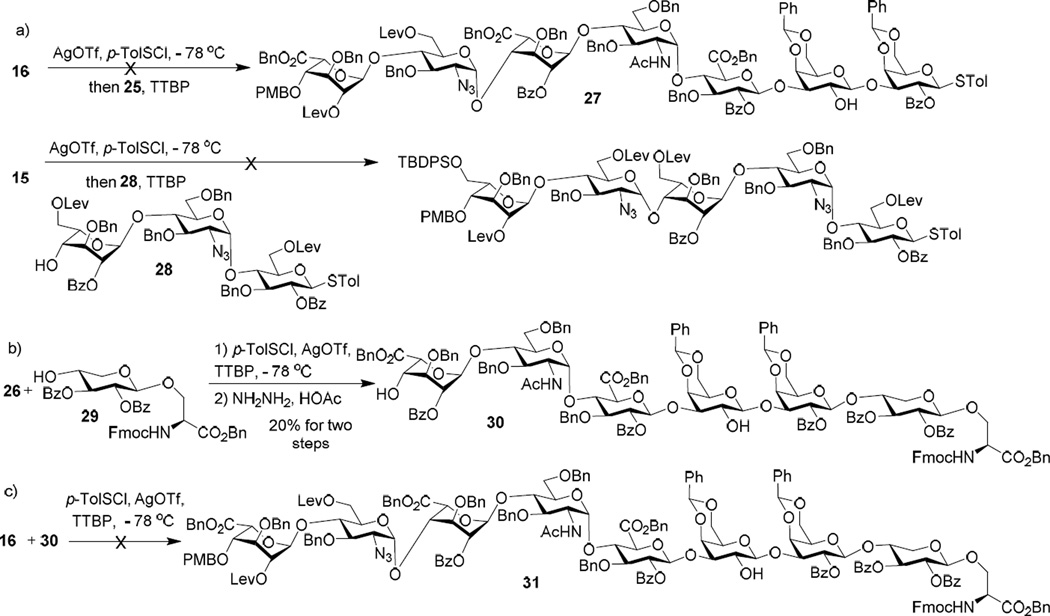

To overcome the aforementioned difficulty, a second generation approach was designed to avoid the late stage formation of the B/C linkage by adapting a 3+2+3 strategy using building blocks consisted of ABC trisaccharide, DE disaccharide and FGH trisaccharide. To form the key B/C linkage, glycosylation of idosyl acceptor 33 by glucosamine donor 32 was carried out (Scheme 4a). Gratifyingly, this reaction proceeded smoothly, forming the BC disaccharide 34 in 80% yield with the αanomer as the sole stereoisomer isolated. The stereochemistry of the newly formed glycosidic linkage was confirmed by NMR analysis (1JC1’-H1’ = 169 Hz).100 The low reactivities of the oligosaccharide building blocks such as 16, 26 and 28 are presumably due to electron withdrawing power and/or steric hindrance associated with the additional glycan rings.101–103 Protective group manipulation of 34 produced disaccharide acceptor 35, which was glycosylated by the idosyl donor 12 giving ABC trisaccharide 36 (Scheme 4b). The DE disaccharide 40 was formed by reaction of azido glucoside donor 37 with glucoside 38 followed by protective group adjustment (Scheme 4c). In order to avoid the remote participation by the 6-O-PMB moiety in future glycosylation, the PMB group in 39 was replaced with TBDPS (disaccharide 40). The reducing end FGH trisaccharide module was prepared by glycosylating the xylosyl serine 29 with galactoside donor 4198 leading to disaccharide 42 in 81% yield (Scheme 4d). This yield was significantly higher than that for the formation of 30, again suggesting higher reactivity of monosaccharide building blocks compared to the corresponding oligosaccharide donor. The Lev group in 42 was removed, which subsequently underwent glycosylation with galactoside donor 21 followed by hydrazine treatment to generate FGH trisaccharide 44.

Scheme 4.

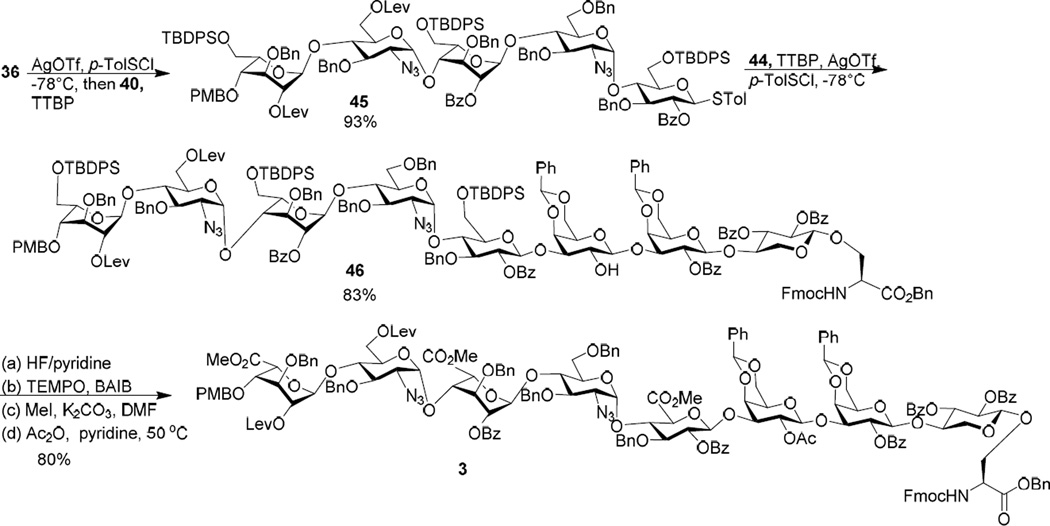

With the three modules prepared, their union was tested next (Scheme 5). Under the pre-activation condition, glycosylation of disaccharide DE acceptor 40 by ABC trisaccharide donor 36 led to pentasaccharide 45 in an excellent 93% yield. Pentasaccharide 45 was a competent donor, successfully glycosylating the FGH trisaccharide module 44 and producing the octasaccharide module 46. The successful assembly of 46 indicates that the C/D and E/F linkages are suitable strategic linkage points for constructing the octasaccharide module. In order to prepare the compound 3, glycosyl serine 46 was de-silylated followed by oxidation of the three newly freed hydroxyl groups to carboxylic acids, methyl ester formation and acetylation. Elevated reaction temperature and excess acetic anhydride were necessary for acetylation due to the low reactivity of the free hydroxyl group in 46.

Scheme 5.

Assembly of the glucuronic acid containing octasaccharide serine cassette 4

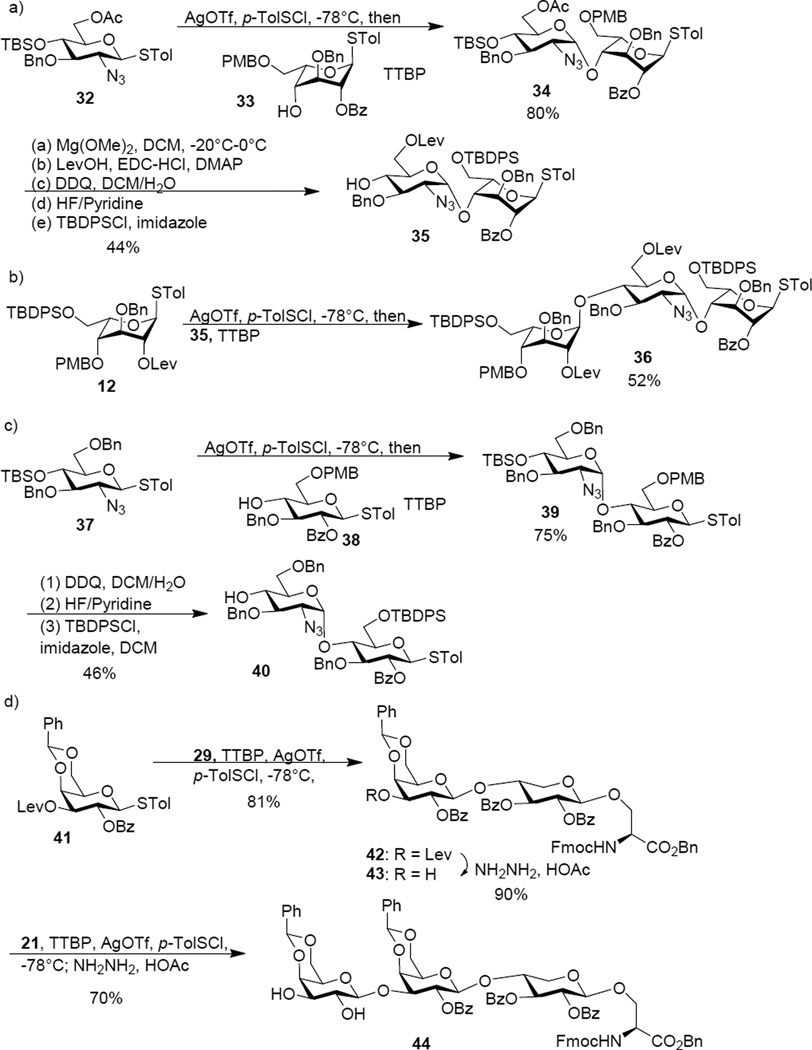

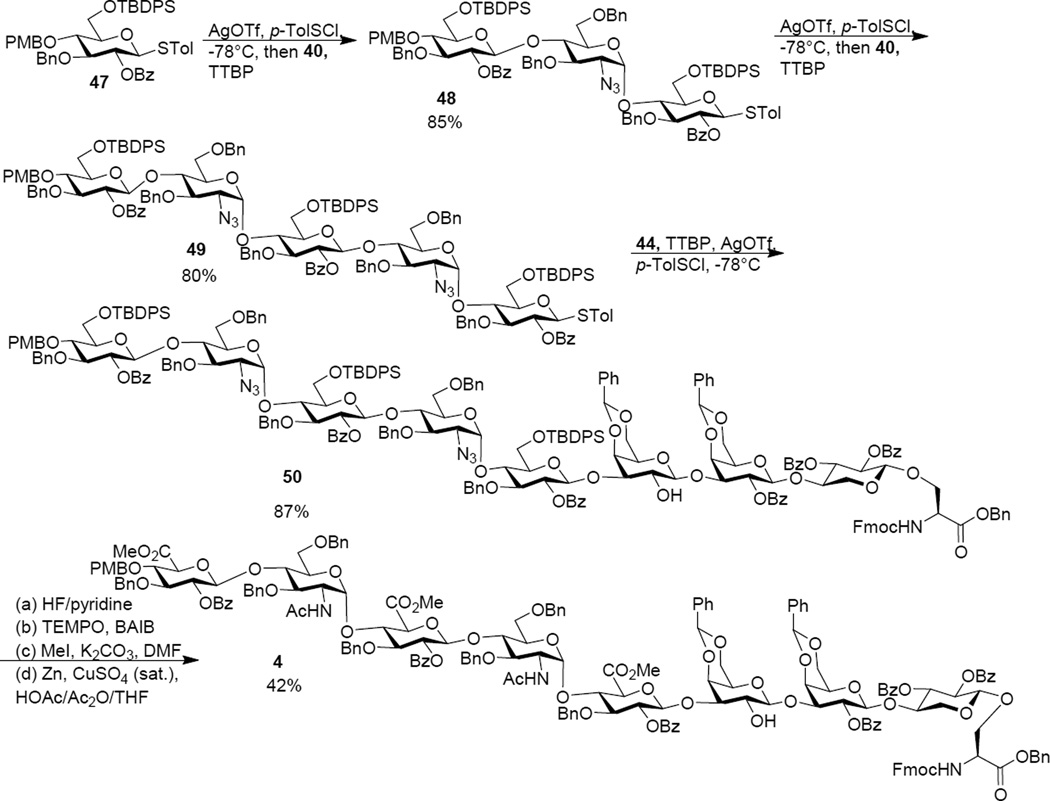

With the knowledge gained in preparing octasaccharide 3, the octasaccharide serine cassette 50 was synthesized following the same 3+2+3 approach (Scheme 6). The glucoside donor 47, pre-activated by p-TolSCl/AgOTf, glycosylated disaccharide 40 generating ABC trisaccharide 48 in 85% yield. The 3+2 glycosylation between trisaccharide 48 and disaccharide 40 went smoothly producing pentasaccharide 49, which subsequently glycosylated the trisaccharide serine unit 44 leading to the octasaccharide cassette 50 in an excellent 87% yield. The successful preparation of octasaccharide 50 demonstrated the generality of the 3+2+3 route. The TBDPS silyl ether groups in 50 were removed by HF/pyridine to expose the three primary hydroxyls, which were oxidized to carboxylic acids92 and subsequently converted to methyl esters. The two azide groups were transformed to N-acetyl moieties through a one pot reduction/acetylation procedure104 to afford octasaccharide 4.

Scheme 6.

Obstacles in glycopeptide synthesis

The glycopeptide assembly was explored next. With the high sensitivity of O-sulfates to acid and the propensity of the glycopeptide to undergo base promoted β-elimination,105–107 common amino acid side chain protective groups such as Boc and trityl should be avoided and the sequence and condition of deprotection need to be optimized.

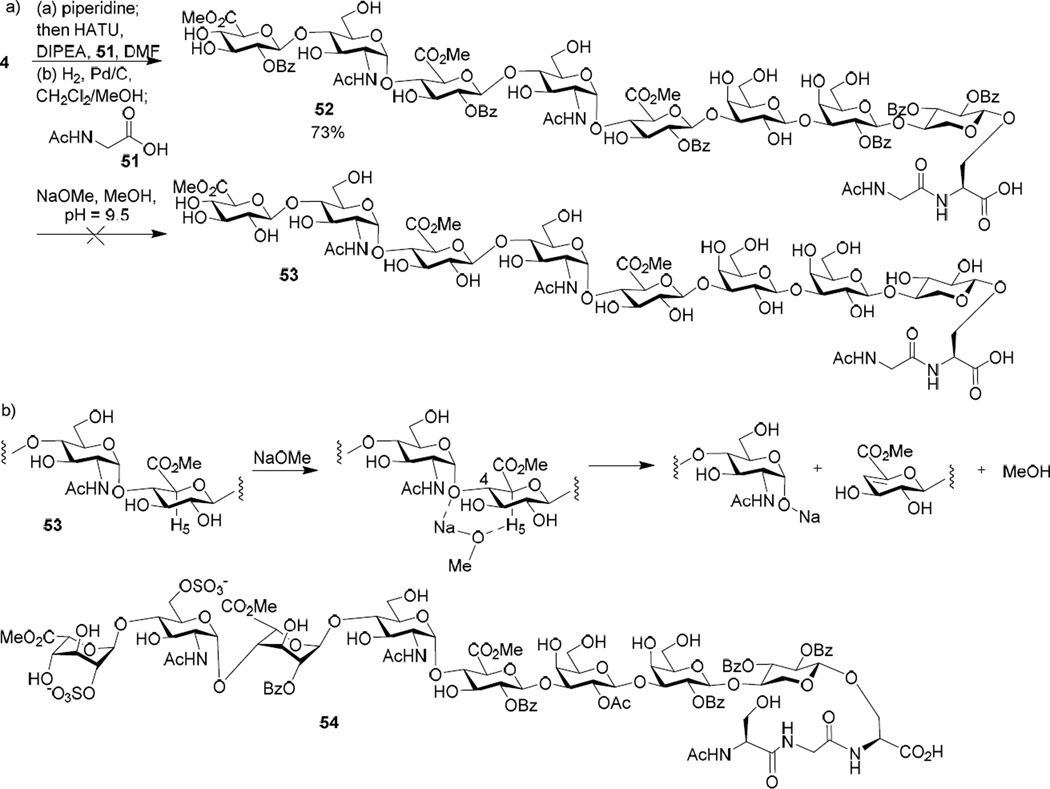

To test the deprotection condition, octasaccharide 4 was treated with piperidine108 to remove the N-terminal Fmoc followed by coupling with glycine 51 and catalytic hydrogenolysis to produce glycopeptide 52 (Scheme 7a). The next step was transesterification using NaOMe/MeOH (~ pH 9.5) to remove the Ac and Bz groups. Although this condition was previously successfully applied to an iduronic acid containing octasaccharide module 54, multiple fragments from backbone cleavages at non-reducing ends of glucuronic acids of 53 were observed based on mass spectrometry analysis. The higher lability of glycopeptide 53 to base treatment was possibly because the 4-O can coordinate with Na+ ion thus bringing the NaOMe closer to the acidic axial proton on the adjacent C-5 center (Scheme 7b). This in turn can facilitate the removal of the H-5 arranged in 1,2-cis geometry to the 4-O. Neighboring group assisted glycan cleavages are known.51,109

Scheme 7.

The base sensitivity of the glycopeptide suggests a less basic yet stronger nucleophile such as hydrazine78,110 would be needed for deacylation. A model glycopeptide 55 was treated with hydrazine, which successfully cleaved the Bz and Lev groups without affecting the sulfates or the glycan/peptide linkage. In order to apply the hydrazine reaction to syndecan-3 glycopeptides, the carboxylic acid moieties of uronic acids cannot be protected as esters during the hydrazine treatment to prevent the potential hydrazide formation. This consideration led to the design of a new route, where the full length glycopeptide 56 was to be assembled from two fragments: glycopeptides 57 and 58, which could be prepared through peptide coupling. The uronic methyl esters of 56 can be converted to free carboxylic acids by mild base treatment for subsequent hydrazinolysis.

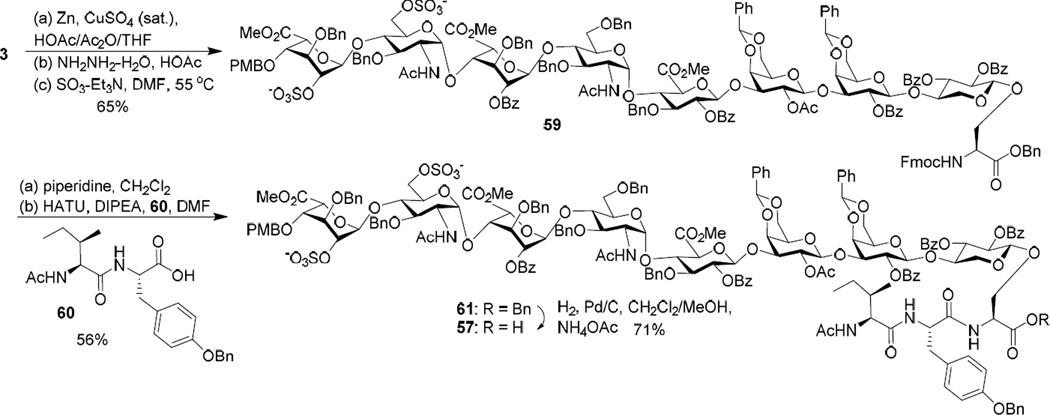

In order to synthesize glycopeptide 57, glycosyl serine 3 was transformed to octasaccharide 59 through conversion of azides to acetamides, Lev group removal by hydrazine acetate and sulfation of the free hydroxyl groups.111 The Fmoc group in octasaccharide 59 was removed and the resulting amine was coupled with dipeptide 60 to produce glycopeptide 61. The tyrosine hydroxyl group in the side chain of peptide 61 was protected with Bn, which can be deprotected under hydrogenation conditions. The benzyl ester in glycopeptide 61 was selectively removed under hydrogenation in the presence of NH4OAc114 leading to free carboxylic acid glycopeptide 57 (Scheme 8).

Scheme 8.

Similarly, hydrogenation of octasaccharide 4 in the presence of NH4OAc112 afforded glycopeptide 62 containing the free C-terminal carboxylic acid (Scheme 9). Peptide elongation with tripeptide 63 gave glycopeptide 64. Treatment of 64 with piperidine followed by coupling with tripeptide 65 and Fmoc deprotection led to the free amine bearing glycopeptide 58.

Scheme 9.

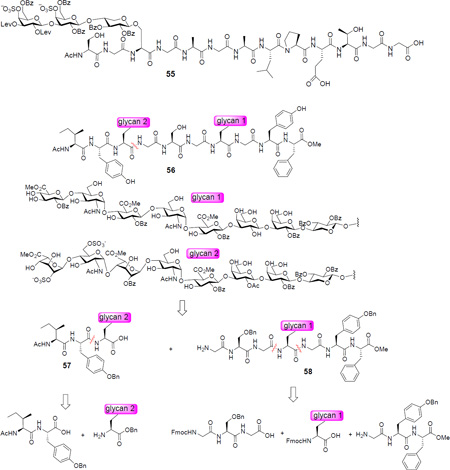

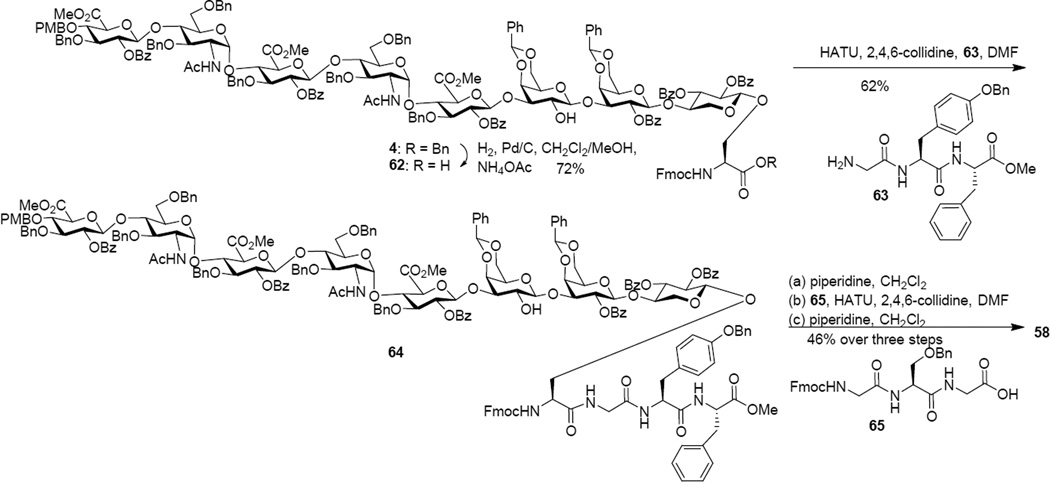

Glycopeptides 57 and 58 were united in a peptide coupling reaction promoted by O-(7-azabenzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HATU) to generate glycopeptide 66 bearing two different glycans (Scheme 10). Glycopeptide 66 was hydrogenated with Pearlman’s reagent or Pd/C under atmospheric pressure of hydrogen gas in mixed solvents of CH2Cl2 and methanol to remove the benzyl ethers, PMB and benzylidene groups. However, no desired product 56 was obtained. It is possible that the partially deprotected glycopeptides formed during hydrogenation aggregated due to solubility changes preventing access to the palladium catalyst. Colloidal Pd nanoparticles were tested next as the Wong group reported that these nanoparticles could remove benzyl ethers from solid phase bound glycans.113 Various solvents including tetrahydrofuan, methanol/water and hexafluoro-isopropanol, were also examined to disrupt the potential aggregate. Other conditions tested included various pH values, reaction temperature and elevated hydrogen pressure. However, the desired compound 56 was not found with decomposition products observed in mass spectrometry analysis. The difficulty with glycopeptide 66 was not unique as several other glycopeptides bearing two heparan sulfate glycans decomposed as well when subjected to hydrogenation. Hojo, Nakahara and coworkers reported a procedure using low acidity triflic acid to remove benzyl ethers from O-sulfated glycopeptides.114 In our hands, this condition cleaved the O-sulfates from glycopeptide 66 without successful debenzylation.

Scheme 10.

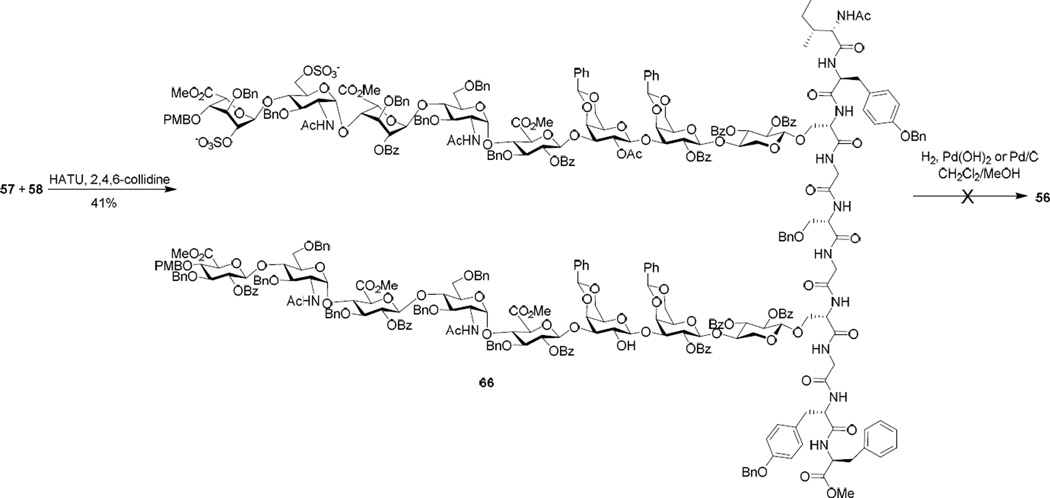

Successful synthesis of glycopeptide 1

Due to the unexpected difficulty in the hydrogenation of 66, an alternative was to perform hydrogenation on glycopeptides 61 and 58 bearing a single heparan sulfate chain. The iduronic acid containing non-sulfated glycopeptide 67 was tested first, which was prepared analogously to 61. Catalytic hydrogenation of compound 67 under a slightly acidic condition (pH ~ 5.5) using Pearlman’s catalyst went smoothly and gave the desired product 68 in quantitative yield (Scheme 11). Similarly, sulfated glycopeptide 61 was successfully hydrogenated yielding 69. The reason for the increase in fragility of glycopeptides bearing two heparan sulfate chains towards hydrogenation is not clear.

Scheme 11.

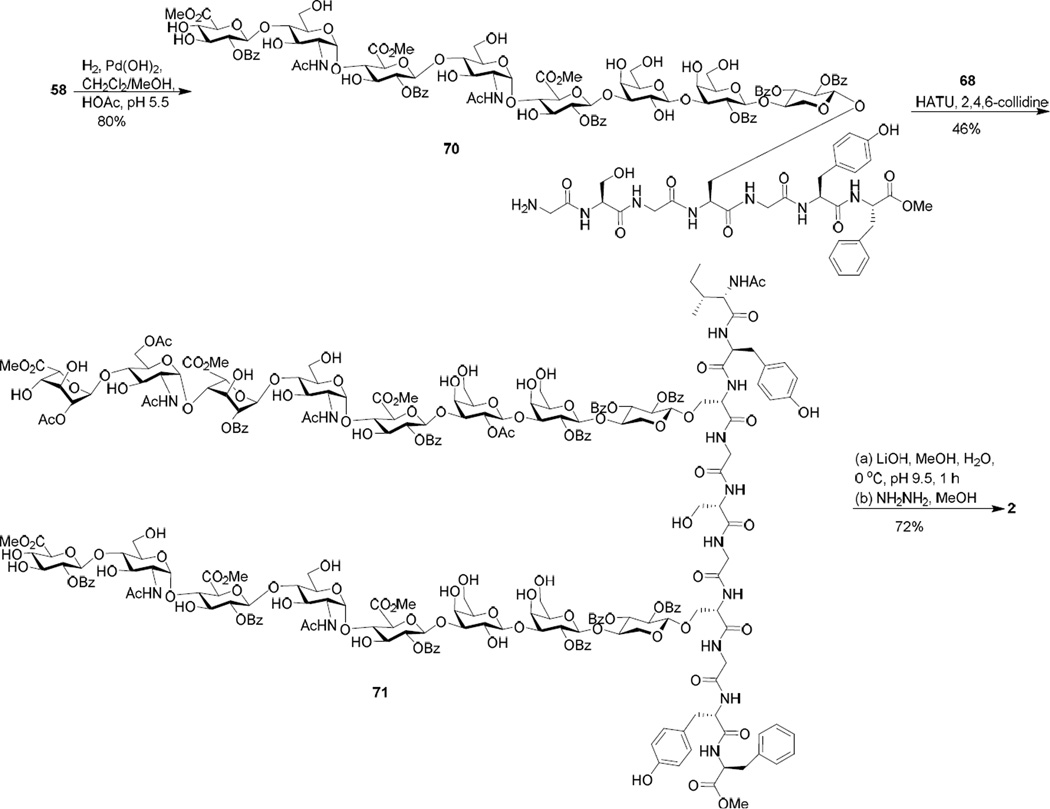

The hydrogenation of glycopeptide 58 was performed next to generate amine 70 (Scheme 12). This reaction was slower than those of 61 and 67 and needed to be closely monitored to prevent over-reduction. 70 was coupled with carboxylic acid 68 (2 eq) producing glycopeptide 71 in 46% yield. To complete the deprotection, the three methyl esters in 71 were cleaved by LiOH (pH 9.5) followed by hydrazine to afford the fully deprotected glycopeptide 2 in 72% yield over the two steps (Scheme 12).

Scheme 12.

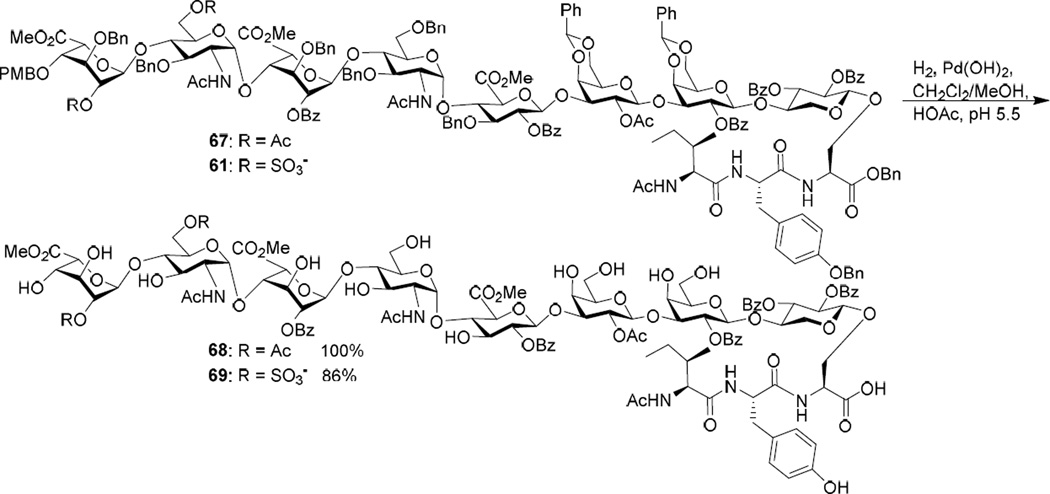

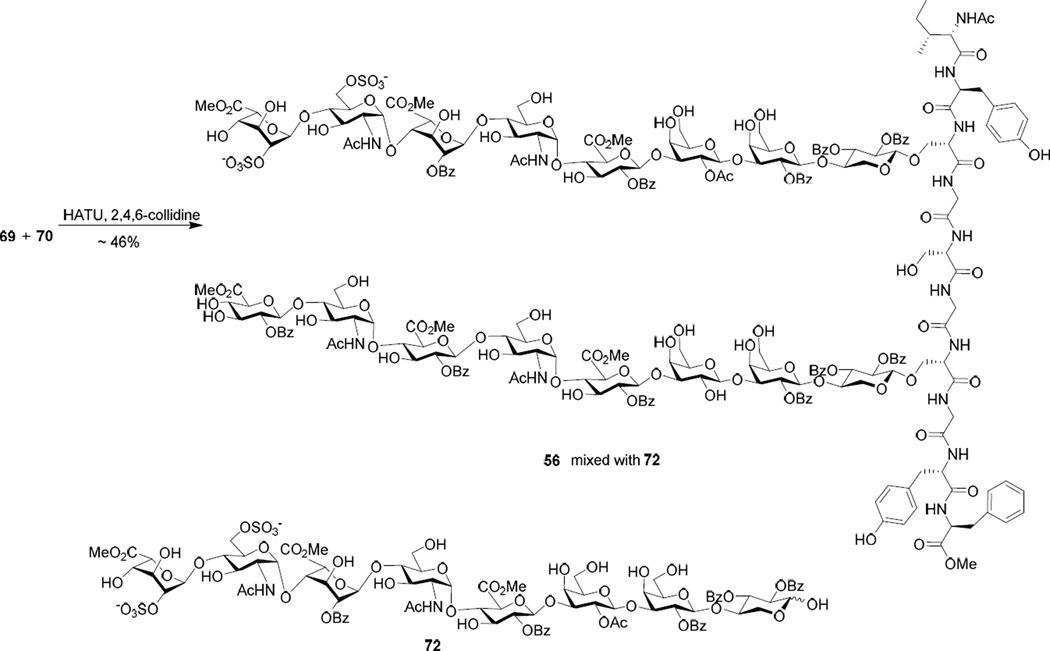

The synthesis of the sulfated glycopeptide 1 was tested next. When 2 eq of carboxylic acid 69 was utilized in the HATU mediated coupling with amine 70, the desired product 56 was observed, but contaminated with glycan 72 resulting from β-elimination of 69 (Scheme 13). The separation of 72 from 56 turned out to be very difficult. When 1.5 equiv of glycopeptide 69 was utilized, the coupling yield was much lower.

Scheme 13.

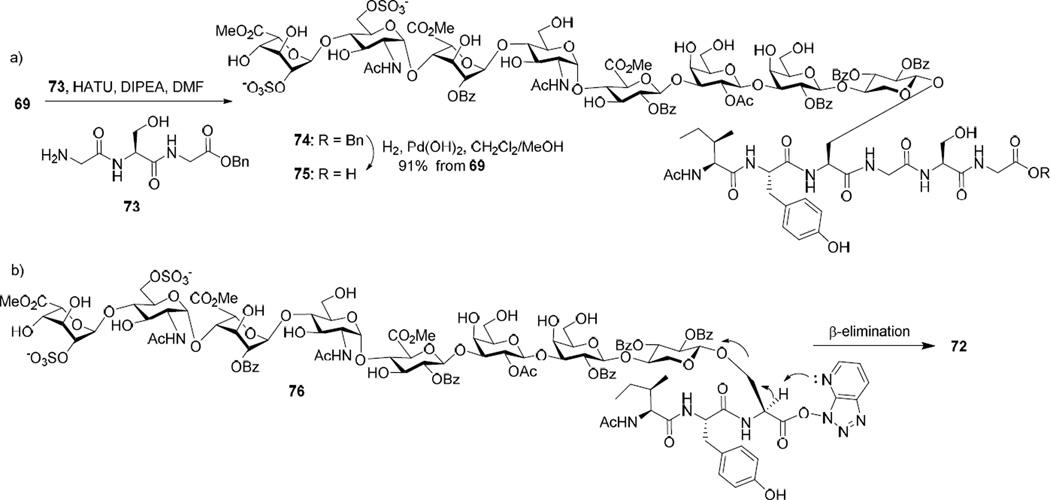

To overcome the elimination problem, we adjusted the sequence for peptide chain elongation by coupling carboxylic acid 69 with tripeptide 73 first (Scheme 14a). We envisioned the smaller tripeptide 73 should be a better nucleophile than amine 70. Indeed, the reaction of glycopeptide 69 with tripeptide 73 went smoothly with no β-elimination product 72, which led to glycopeptide 75 after hydrogenation. This suggests the formation of 72 (Scheme 13) was not because of the inherent instability of glycopeptide 56 under the peptide coupling condition. Rather, it was possibly due to the enhanced lability of the activated ester 76 formed between 71 and HATU towards β-elimination (Scheme 14b), which could outcompete the desired amide bond formation reaction with the more bulky and presumably less reactive amine 70.

Scheme 14.

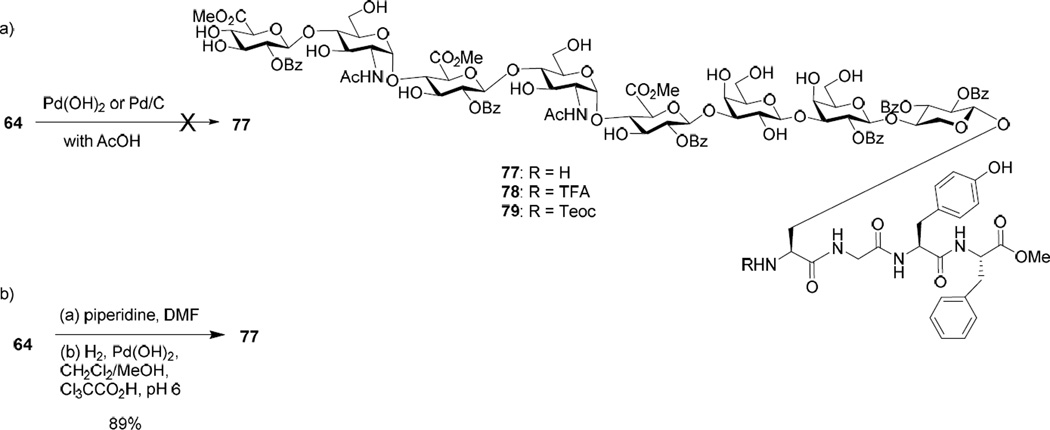

To complete the glycopeptide synthesis, amine 77 was needed. Catalytic hydrogenation of 64 catalyzed by Pd(OH)2 or Pd/C proceeded very slowly (Scheme 15a). With prolonged reaction time, multiple side products due to methylation of the free N-terminus115 and reduction of phenyl rings were formed, which could not be separated from the desired product. To address this issue, an alternative route was explored by installing a protective group onto the N-terminus, which is stable under hydrogenation condition and yet known to be removable under mild conditions. Several amine protective groups including trifluoroacetamide (TFA), 2-trimethylsilylethoxycarbonyl (Teoc)116 and 2-pyridylethoxycarbonyl (Pyoc)117 were examined. Global hydrogenolysis went smoothly on the TFA and Teoc protected glycosyl serine, while Pyoc protected one gave multiple unidentified side products. After peptide coupling leading to compounds 78 and 79, we focused on deprotection to generate the free amine. However, with 78, TFA could not be removed under basic or NaBH4 reductive condition118 without affecting the methyl esters in the molecule. The Teoc group in 79 could not be cleaved by HF/pyridine. Treatment of 79 with tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF) led to the cleavage of glycan chain. These unsuccessful attempts prompted us to re-examine the substrate for hydrogenation. After many trials, a viable route was established by first removing the Fmoc from glycopeptide 64 (Scheme 15b). The resulting amine was successfully hydrogenated under a slightly acidic condition (pH 6 with the addition of CCl3CO2H).119 No over-reduction or amine alkylation side products were observed. The usage of trichloroacetic acid was important as the reaction was not successful with acetic acid.

Scheme 15.

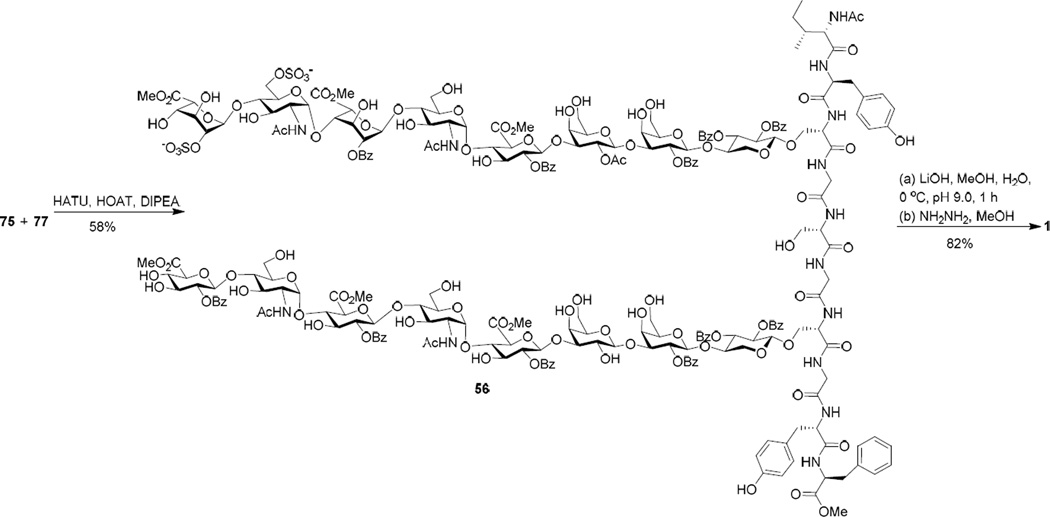

With amine 77 in hand, its coupling with 75 was carried out with 1.3 eq of 75 and HATU providing 56 in 58% yield (Scheme 16). No β-elimination side product 72 was observed from this reaction, which was consistent with the formation of 74. Final deprotection of 56 was performed under a mild basic condition. The sulfated glycan chain was very sensitive to base as pH 9.5 LiOH led to partial chain cleavage. Instead, the methyl ester removal was performed at pH 9.0 with frequent monitoring using mass spectrometry, which was followed by hydrazinolysis to afford glycopeptide 1 in 82% yield.

Scheme 16.

Conclusion

A successful strategy was developed for the assembly of syndecan-3 (53–62) glycopeptides bearing two heparan sulfate chains. Many obstacles were encountered during the syntheses of these highly complex molecules. For construction of the glycan chains, among many potential routes, we found the difficult B/C glycosyl linkages should be formed early due to higher reactivities of the monosaccharide building blocks. Furthermore, as the size of the molecule grows larger, unique reactivity and stability problems can emerge as evident from the instability of glycopeptides containing two heparan sulfate chains to the catalytic hydrogenation condition. To overcome this obstacle, the hydrogenation reaction was performed on the glycopeptide bearing a single glycan chain. Performing the hydrogenation reaction with addition of trichloroacetic acid at pH6 was found to significantly improve the yield and suppress side product formation. Another challenge encountered was the propensity of glycopeptide bearing glycan chain at the C-terminus to undergo competing β-elimination during peptide elongation reaction with larger and less reactive amine partners. This was overcome by varying the peptide coupling sequences. Following the union of partially deprotected fragments, the final deprotection of the glycopeptide required the cleavage of all ester protective groups, which was accomplished by mild base treatment (pH 9.0) followed by hydrazinolysis. The hydrazinolysis procedure was critical to ensure complete removal of all acyl protective groups without the undesired β-elimination or cleavage of the highly sensitive glycan chain. Efforts are ongoing to extend the peptide backbone and glycan chains of glycopeptides as well as applying the strategy to synthesis of other glycosaminoglycan family glycopeptides bearing multiple heparan sulfate chains.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A convergent synthesis of heparan sulfate chain with linkage region was developed.

Glycopeptides with two glycan chains showed unusual lability during hydrogenation.

Glycopeptide coupling sequence was crucial to avoid elimination of the glycan chain.

Heparan sulfate glycopeptides with multiple glycan chains were synthesized.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (CHE 1507226) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, NIH (R01GM072667, U01 GM116262 and U01 GM102137).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supporting information: Complete experimental procedures and characterizations are provided, including 1H and 13C NMR spectra of all new compounds.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Apweiler R, Hermjakob H, Sharon N. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1473:4–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dwek RA. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:683–720. doi: 10.1021/cr940283b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helenius A, Aebi M. Science. 2005;291:2364–2369. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varki A. Glycobiology. 1993;3:97–130. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pratt MR, Bertozzi CR. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005;34:58–68. doi: 10.1039/b400593g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernfield M, Götte M, Park PW, Reizes O, Fitzgerald ML, Lincecum J, Zako M. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:729–777. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piontek C, Varón Silva D, Heinlein C, Pöhner C, Mezzato S, Ring P, Martin A, Schmid FX, Unverzagt C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:1941–1945. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang P, Dong S, Shieh J-H, Peguero E, Hendrickson R, Moore MAS, Danishefsky SJ. Science. 2013;342:1357–1360. doi: 10.1126/science.1245095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murakami M, Kiuchi T, Nishihara M, Tezuka K, Okamoto R, Izumi M, Kajihara Y. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1500678. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu C, Lam HY, Zhang Y, Li X. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:6200–6202. doi: 10.1039/c3cc42573h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Izumi R, Matsushita T, Fujitani N, Naruchi K, Shimizu H, Tsuda S, Hinou H, Nishimura S-I. Chem. Eur. J. 2013;19:3913–3920. doi: 10.1002/chem.201203731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai H, Chen M-S, Sun Z-Y, Zhao Y-F, Kunz H, Li Y-M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:6106–6110. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ullmann V, Raedisch M, Boos I, Freund J, Poehner C, Schwarzinger S, Unverzagt C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:11566–11570. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkinson BL, Stone RS, Capicciotti CJ, Thaysen-Andersen M, Matthews JM, Packer NH, Ben RN, Payne RJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:3606–3610. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakamoto I, Tezuka K, Fukae K, Ishii K, Taduru K, Maeda M, Ouchi M, Yoshida K, Nambu Y, Igarashi J, Hayashi N, Tsuji T, Kajihara Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:5428–5431. doi: 10.1021/ja2109079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang P, Dong S, Brailsford JA, Iyer K, Townsend SD, Zhang Q, Hendrickson RC, Shieh J, Moore MAS, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:11576–11584. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen R, Tolbert TJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3211–3216. doi: 10.1021/ja9104073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanki AK, Talan RS, Sucheck SJ. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:1886–1896. doi: 10.1021/jo802278w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crich D, Sasaki K, Rahaman MY, Bowers AA. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:3886–3893. doi: 10.1021/jo900532e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Y-Y, Ficht S, Brik A, Wong C-H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7690–7701. doi: 10.1021/ja0708971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto N, Tanabe Y, Okamoto R, Dawson PE, Kajihara Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:501–510. doi: 10.1021/ja072543f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shao N, Xue J, Guo Z. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:1569–1573. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin Y, Winans KA, Backes BJ, Kent SBH, Ellman JA, Bertozzi CR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:11684–11689. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hojo H, Tanaka H, Hagiwara M, Asahina Y, Ueki A, Katayama H, Nakahara Y, Yoneshige A, Matsuda J, Ito Y, Nakahara Y. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:9437–9446. doi: 10.1021/jo3010155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Z, Guo X, Wang Q, Swarts BM, Guo Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1567–1571. doi: 10.1021/ja906611x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heidecke CD, Ling Z, Bruce NC, Moir JWB, Parsons TB, Fairbanks AJ. Chem Biochem. 2008;9:2045–2051. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li B, Zeng Y, Hauser S, Song H, Wang L-X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:9692–9693. doi: 10.1021/ja051715a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takano Y, Hojo H, Kojima H, Nakahara Y. Org. Lett. 2004;6:3135–3138. doi: 10.1021/ol048827b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.George SK, Schwientek T, Holm B, Reis CA, Clausen H, Kihlberg J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11117–11125. doi: 10.1021/ja015570t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Witte K, Sears P, Wong C-H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:2114–2118. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Unverzagt C, Kajihara Y. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42:4408–4420. doi: 10.1039/c3cs35485g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siman P, Brik A. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:5684–5697. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25149c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Payne RJ, Wong C-H. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:21–43. doi: 10.1039/b913845e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gamblin DP, Scanlan EM, Davis BG. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:131–163. doi: 10.1021/cr078291i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L-X. Carbohydr. Res. 2008;343:1509–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2008.03.025. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hojo H, Nakahara Y. Biopolymers. 2007;88:308–324. doi: 10.1002/bip.20699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herzner H, Reipen T, Schultz M, Kunz H. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:4495–4537. doi: 10.1021/cr990308c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meldal M, Bock K. Glycoconjugate J. 1994;11:59–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00731144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dulaney SB, Huang X. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 2012;67:95–136. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396527-1.00003-6. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noti C, Seeberger PH. In: Chemistry and Biology of Heparin and Heparan Sulfate. Garg HG, Linhardt RJ, Hales CA, editors. Oxford: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 79–142. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petitou M, van Boeckel CAA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3118–3133. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300640. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Codée JDC, Overkleeft HS, van der Marel GA, van Boeckel CAA. Drug Discovery Today: Technol. 2004;1:317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poletti L, Lay L. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003:2999–3024. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karst NA, Linhardt RJ. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003;10:1993–2031. doi: 10.2174/0929867033456891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hansen SU, Miller GJ, Cliff MJ, Jayson GC, Gardiner JM. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:6158–6164. doi: 10.1039/c5sc02091c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hansen SU, Miller GJ, Cole C, Rushton G, Avizienyte E, Jayson GC, Gardiner JM. Nature Commun. 2013;4 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheng GJ, Oh YI, Chang S-K, Hsieh-Wilson LC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:10898–10901. doi: 10.1021/ja4027727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu Y, Wang Z, Liu R, Bridges AS, Huang X, Liu J. Glycobiology. 2012;22:96–106. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr109. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu Y, Masuko S, Takeiddin M, Xu H, Liu R, Jing J, Mousa SA, Linhardt RJ, Liu J. Science. 2011;334:498–501. doi: 10.1126/science.1207478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu Y-P, Lin S-Y, Huang C-Y, Zulueta MML, Liu J-Y, Chang W, Hung S-C. Nature Chem. 2011;3:557–563. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tiruchinapally G, Yin Z, El-Dakdouki M, Wang Z, Huang X. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:10106–10112. doi: 10.1002/chem.201101108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Czechura P, Guedes N, Kopitzki S, Vazquez N, Martin-Lomas M, Reichardt N-C. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:2390–2392. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04686h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Z, Xu Y, Yang B, Tiruchinapally G, Sun B, Liu R, Dulaney S, Liu J, Huang X. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:8365–8375. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arungundram S, Al-Mafraji K, Asong J, Leach FE, Amster IJ, Venot A, Turnbull JE, Boons GJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17394–17405. doi: 10.1021/ja907358k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baleux F, Loureiro-Morais L, Hersant Y, Clayette P, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Bonnaffé D, Lortat-Jacob H. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:743–748. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.207. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen J, Zhou Y, Chen C, Xu W, Yu B. Carbohydr. Res. 2008;343:2853–2862. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dilhas A, Lucas R, Loureiro-Morais L, Hersant Y, Bonnaffe D. J. Comb. Chem. 2008;10:166–169. doi: 10.1021/cc8000019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tatai J, Fügedi P. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:9865–9873. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Polat T, Wong C-H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12795–12800. doi: 10.1021/ja073098r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Noti C, de Paz JL, Polito L, Seeberger PH. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:8664–8686. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Codée JDC, Stubba B, Schiattarella M, Overkleeft HS, van Boeckel CAA, van Boom JH, van der Marel GA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:3767–3773. doi: 10.1021/ja045613g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Paz JL, Martin-Lomas M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005:1849–1858. and references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fan R-H, Achkar J, Hernandez-Torres JM, Wei A. Org. Lett. 2005;7:5095–5098. doi: 10.1021/ol052130o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ojeda R, Terenti O, de PJ-L, Martin-Lomas M. Glycoconjugate J. 2004;21:179–195. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000045091.18392.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lucas R, Hamza D, Lubineau A, Bonnaffé D. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004:2107–2117. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Poletti L, Fleischer M, Vogel C, Guerrini M, Torri G, Lay L. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001:2727–2734. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Petitou M, Herault J-P, Bernat A, Driguez P-A, Duchaussoy P, Lormeau J-C, Herbert J-M. Nature. 1999;398:417–422. doi: 10.1038/18877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sinaÿ P, Jacquinet JC, Petitou M, Duchaussoy P, Lederman I, Choay J, Torri G. Carbohydr. Res. 1984;132:C5–C9. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90633-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ait-Mohand K, Lopin-Bon C, Jacquinet JC. Carbohydr. Res. 2012;353:33–48. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2012.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang T-Y, Zulueta MML, Hung S-C. Org. Lett. 2011;13:1506–1509. doi: 10.1021/ol200192d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tamura J-i, Nakamura-Yamamoto T, Nishimura Y, Mizumoto S, Takahashi J, Sugahara K. Carbohydr. Res. 2010;345:2115–2123. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shimawaki K, Fujisawa Y, Sato F, Fujitani N, Kurogochi M, Hoshi H, Hinou H, Nishimura S-I. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:3074–3079. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thollas B, Jacquinet J-C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004;2:434–442. doi: 10.1039/b314244b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tamura J, Yamaguchi A, Tanaka J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002;12:1901–1903. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00327-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Allen JG, Fraser-Reid B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:468–469. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yasukochi T, Fukase K, Suda Y, Takagaki K, Endo M, Kusumoto S. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1997;70:2719–2725. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Neumann KW, Tamura J, Ogawa T. Glycoconjugate J. 1996;13:933–936. doi: 10.1007/BF01053188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rio S, Beau JM, Jacquinet JC. Carbohydr. Res. 1994;255:103–124. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen L, Kong F. Carbohydr. Res. 2002;337:1373–1380. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(02)00169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yoshida K, Yang B, Yang W, Zhang Z, Zhang J, Huang X. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:9051–9058. doi: 10.1002/anie.201404625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tkachenko E, Rhodes JM, Simons M. Circ. Res. 2005;96:488–500. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000159708.71142.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zimmermann P, David G. FASEB J. 1999;13:S91–S100. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.9001.s91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bespalov MM, Sidorova YA, Tumova S, Ahonen-Bishopp A, Magalhaes AC, Kulesskiy E, Paveliev M, Rivera C, Rauvala H, Saarma M. J. Cell Biol. 2011;192:153–169. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pisconti A, Cornelison DDW, Olguin HC, Antwine TL, Olwin BB. J. Cell Biol. 2010;190:427–441. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Casar JC, Cabello-Verrugio C, Olguin H, Aldunate R, Inestrosa NC, Brandan E. J. Cell. Sci. 2004;117:73–84. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cornelison DDW, Wilcox-Adelman SA, Goetinck PF, Rauvala H, Rapraeger AC, Olwin BB. Genes. Dev. 2004;18:2231–2236. doi: 10.1101/gad.1214204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kosher RA. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1998;43:123–130. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19981015)43:2<123::AID-JEMT5>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.de Witte L, Bobardt M, Chatterji U, Degeest G, David G, Geijtenbeek TB, Gallay P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:19464–19469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gould SE, Upholt WB, Kosher RA. Dev. Biol. 1995;168:438–451. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gould SE, Upholt WB, Kosher RA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:3271–3275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen X-T, Sames D, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:7760–7769. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Van den Bos LJ, Codee JDC, Van der Toorn JC, Boltje TJ, Van Boom JH, Overkleeft HS, Van der Marel GA. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2165–2168. doi: 10.1021/ol049380+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Blatter G, Jacquinet J-C. Carbohydr. Res. 1996;288:109–125. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(96)90785-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huang L, Huang X. Chem. Eur. J. 2007;13:529–540. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Huang L, Teumelsan N, Huang X. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:5246–5252. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Huang X, Huang L, Wang H, Ye X-S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:5221–5224. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Crich D, Smith M, Yao Q, Picione J. Synthesis. 2001:323–326. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Miermont A, Zeng Y, Jing Y, Ye X-S, Huang X. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:8958–8961. doi: 10.1021/jo701694k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liao L, Auzanneau F-I. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:6265–6273. doi: 10.1021/jo050707+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bock K, Pedersen C. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2. 1974:293–297. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zeng Y, Wang Z, Whitfield D, Huang X. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:7952–7962. doi: 10.1021/jo801462r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Koeller KM, Wong C-H. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:4465–4493. doi: 10.1021/cr990297n. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang Z, Ollman IR, Ye X-S, Wischnat R, Baasov T, Wong C-H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:734–753. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vohra Y, Buskas T, Boons G-J. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:6064–6071. doi: 10.1021/jo901135k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yang B, Yoshida K, Yin Z, Dai H, Kavunja H, El-Dakdouki MH, Sungsuwan S, Dulaney SB, Huang X. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:10185–10189. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Borgia JA, Malkar NB, Abbasi HU, Fields GB. J. Biomol. Tech. 2001;12:44–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sjölin P, Elofsson M, Kihlberg J. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:560–565. doi: 10.1021/jo951817r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vuljanic T, Bergquist K-E, Clausen H, Roy S, Kihlberg J. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:7983–8000. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gao J, Thomas DA, Sohn CH, Beauchamp JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:10684–10692. doi: 10.1021/ja402810t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Glunz PW, Hintermann S, Williams LJ, Schwarz JB, Kuduk SD, Kudryashov V, Lloyd KO, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:7273–7279. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Al-Horani RA, Desai UR. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:2907–2918. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.02.015. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kim KS, Kim JH, Lee YJ, Lee YJ, Park J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:8477–8481. doi: 10.1021/ja015842s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kanie O, Grotenbreg G, Wong C-H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:4545–4547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kawahira K, Tanaka H, Ueki A, Nakahara Y, Hojo H, Nakahara Y. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:8143–8153. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Xu C-P, Xiao Z-H, Zhuo B-Q, Wang Y-H, Huang P-Q. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:7834–7836. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01487g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Shute RE, Rich DH. Synthesis. 1987:346–348. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kunz H, Birnbach S, Wernig P. Carbohydr. Res. 1990;202:207–223. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(90)84081-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Weygand F, Frauendorfer E. Chem. Ber. 1970;103:2437–2449. doi: 10.1002/cber.19701030816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Boger DL, Kim SH, Mori Y, Weng J-H, Rogel O, Castle SL, McAtee JJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:1862–1871. doi: 10.1021/ja003835i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.