Introduction

Vasectomy is a safe and effective method of birth control. Although it is a simple elective procedure, vasectomy is associated with potential minor and major complications. The early failure rate of vasectomy (presence of motile sperm in the ejaculate at 3–6 months post-vasectomy) is in the range of 0.3–9% and the late failure rate is in the range of 0.04–0.08%. The no-scalpel vasectomy technique is associated with a lower risk of early postoperative complications and the use of cautery or fascial interposition will reduce the risk of contraceptive failure. As such, detailed preoperative counselling and careful assessment of the post-vasectomy ejaculate (for presence of sperm) is imperative. Failure to provide and document adequate information and counselling to patients may lead to litigation.

The focus of this guideline is the management of men presenting for vasectomy. Specifically, the topics covered include: preoperative counselling, vasectomy efficacy and complications, technical aspects of vasectomy, post-vasectomy semen testing, and interpretation-communication of post-vasectomy semen results. By performing an extensive literature review, we have generated an evidence-based consensus on the management of these men. The objective of this guideline is to help standardize the treatment of men presenting for vasectomy.

1. Preoperative counselling

The procedure should be described during the initial consultation. Men must be informed about wound care and the potential for early complications: infection (0.2–1.5%), bleeding or hematoma (4–20%), and primary surgical failure 0.2–5%).1–5 Men should also be made aware of late complications: chronic scrotal pain (1–14%) and delayed vasectomy failure (0.05–1%).6–8 Such information should be given verbally and an information pamphlet should also be provided. The patient must be told that the vasectomy should be viewed as a permanent form of contraception with a high probability of reversibility.9 Preoperative sperm-banking and post-operative vasectomy reversal and sperm retrieval (for subsequent in vitro fertilization) can be discussed if patients are concerned about the permanent nature of the procedure. The association between vasectomy and prostate disease (cancer) may be discussed and patients can be reassured that the data do not demonstrate a clear association between vasectomy and prostate cancer.10 No other late complications have been associated with vasectomy (e.g., vascular disease, hypertension, testicular cancer) and, as such, these need not be discussed unless the patient inquires.

Most men are potentially fertile shortly after vasectomy. Moreover, in cases of early recanalization or technical failure (e.g., missed vas deferens), men will remain fertile. Therefore, couples must be reminded about the rate of primary surgical failure (0.2–5%) and instructed to use other contraceptive measures until post-vasectomy semen testing has confirmed absence of motile sperm.5 Redoing the vasectomy is recommended if motile spermatozoa continue to be present in the ejaculate at six months after the procedure. Although the relationship between this finding (motile spermatozoa in the ejaculate at six months postoperatively) and subsequent pregnancy has not been established (for obvious reasons), pregnancies have been attributed to unprotected intercourse during the immediate post-vasectomy period (pregnancy risk is ∼0.1% after vasectomy).11

While it is good practice to allow patients time for further reflection on their decision to undergo vasectomy, reconsider alternative contraceptive methods, and seek additional opinions from other healthcare providers, some patients may be fully ready to undergo vasectomy at the end of the initial consultation. In fact, it is logical to assume that most, if not all men in Canada seeking vasectomy have obtained information on the procedure from various sources, including the media, internet, friends/family with experience on vasectomy, or other healthcare providers. Currently, there is no good data in the literature suggesting that providing a “cool-down” period after initial encounter of vasectomy counselling correlates to better surgical outcomes or better patient satisfaction. Thus, in the absence of valid medical reasons, such as time required to discontinue certain medications (e.g., to reduce the risk of bleeding diathesis) or recovery from temporary change of health status (e.g., acute infection), vasectomy may be performed (in selected patients) shortly after the initial consultation.

With regards to the age limit of vasectomy, any man with the legal capacity to provide informed consent (this may vary from province to province) may undergo vasectomy. Recent studies in the U.S. indicate that it is rare for men below the age of 25 to choose vasectomy as a form of contraception.12,13 An earlier study indicates that men who underwent vasectomy in their 20s have a 12.5 times greater likelihood of subsequently seeking vasectomy reversal.14 Though data are lacking for men in their 20s seeking vasectomy, it is prudent to offer more time to these men (to reflect on their decision) prior to performing the surgery. Furthermore, when counselling about vasectomy in young patients, particularly minors and patients with an unclear level of understanding or motivation to undergo vasectomy, surgeons should be prepared to offer consultations for psychosocial and ethical assessment prior to performing the surgery.

Special consideration should be given when performing vasectomy in men with a clinical varicocele or with prior varicocelectomy. It has been estimated that varicoceles are found in 15% of the general male population, with a higher prevalence in men with primary or secondary infertility. Men who undergo surgical varicocelectomy for repair of a clinical varicocele may be left with only the deferential veins as the sole testicular venous return. In addition, during varicocelectomy, it is also possible to damage the testicular artery(ies), leaving the deferential artery as the principal arterial supply to the testis. Thus, when a vasectomy is performed in men who have undergone or may undergo varicocelectomy in the future, it is strongly advisable to isolate the vas deferens carefully and completely exclude the associated deferential arteries and veins so as to avoid potential injury to the deferential vasculature and minimize the risk of ipsilateral testicular injury.15

2. Vasectomy technique (approach and occlusion)

The technique of vasectomy has undergone significant modifications over the years. Furthermore, the equipment, materials, and methods of anesthesia have also evolved. While experienced surgeons may prefer their own approach(es) for vasectomy, it is advisable for surgeons to obtain regular continuing medical education focusing on various issues on vasectomy, from surgical techniques to new studies in current peer-reviewed journals and clinical guidelines.

Anesthetic

Local anesthesia is sufficient for most vasectomies; however, anxious patients or those with complicating factors, such as a previous orchidopexy or other scrotal surgery, may require sedation or a general anesthetic. There is controversy regarding the benefit of topical anesthetic before injection of local,16,17 however, a small 27–32-gauge needle is thought to be beneficial. Pneumatic injectors have not shown a clear benefit,18,19 but may be suitable for patents with a needle phobia. The use of buffered xylocaine has not been studied in vasectomy patients.

Conventional vs. no-scalpel vasectomy

The two most common surgical techniques for accessing the vas during vasectomy are the traditional incisional method and the no-scalpel vasectomy (NSV) technique. The conventional incisional technique involves the use of a scalpel to make one or two incisions and the NSV technique uses a sharp, forceps-like instrument to puncture the skin, the latter approach aimed to reduce adverse events (e.g., bleeding, infection, and pain).

A recent Cochrane review of two randomized, controlled trials indicates that the NSV is associated with a significantly lower risk of postoperative hematoma (odds ratio [OR] 0.20 [0.13, 0.32]), pain during surgery (OR 0.75 [0.61, 0.93]), postoperative scrotal pain (OR 0.63 [0.50, 0.80]), and wound infection (OR 0.21 [0.06, 0.78]), than the standard incision group.20–22 Based on the same review, NSV is a faster procedure than conventional surgery. However, there was no significant difference in the effectiveness (azoospermic or absence of motile sperm) of the two procedures.

Recommendation: NSV is associated with a significantly lower risk of postoperative complications (hematoma, pain, infection) than conventional vasectomy (Grade A–B) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Grades of guideline recommendations according to quality of evidence

| Grade A | Based on clinical studies of good quality and consistency with at least one randomized trial |

| Grade B | Based on well-designed studies (prospective, cohort), but without good randomized clinical trials |

| Grade C | Based on poorer quality studies (retrospective, case series, expert opinion) |

Modified from Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.

Fascial interposition vs. no fascial interposition

In a randomized, controlled trial of over 800 vasectomies, it was shown that the use of fascial interposition during vasectomy is associated with a significantly higher rate of azoospermia at three months than no interposition (OR 0.42 [0.26, 0.70]).4,23,24 However, fascial interposition may increase the complication rate of vasectomy.25

Recommendation: Fascial interposition during vasectomy is associated with a significantly higher rate of azoospermia at three months than no interposition (Grade B).

Cautery vs. fascial interposition

In a comparative (case-control) study, cautery of the vas was associated with a lower risk of failure (defined as >100 000 sperm in the ejaculate) than fascial interposition (1% vs. 4.9%, OR 4.8 [1.6–14.3]).3

Recommendation: Cautery of the vas is associated with a lower risk of failure (defined as >100 000 sperm in the ejaculate) than fascial interposition (Grade B).

Arguably, the above findings on azoospermia rates are somewhat confusing (“fascial interposition is better than no fascial interposition” and “cautery is better than fascial interposition”). However, the take-home message is that both cautery and fascial interposition are the best vas occlusion methods.

3. Contraceptive efficacy of vasectomy

The early failure rate of vasectomy (presence of motile sperm in the ejaculate at three to six months post-vasectomy) is in the range of 0.3–9% and has been linked to operator experience and the technique used by the surgeon.25 Both technical failure (e.g., missed vas deferens) and early recanalization of the vas deferens have been proposed as plausible explanations.

Late failure has been reported to be in the range of 0.04–0.08% (approximately 1/2000 cases) and is defined as the presence of motile spermatozoa in the ejaculate after documented azoospermia in two post-vasectomy semen analyses.7,26 In most cases, late failure is first identified as a pregnancy and later confirmed by semen analysis (documenting presence of motile spermatozoa).

The reappearance of sperm (mostly immotile) after documented azoospermia in two post-vasectomy semen samples may be much higher than 1/2000 according to the reported identification of spermatozoa in nearly 10% of ejaculates from men undergoing semen assessment prior to vasectomy reversal.27 It is unlikely that the reappearance (or persistence) of immotile sperm years after vasectomy is of clinical significance, as this has not been associated with documented pregnancies.28,29

4. Postoperative counselling

After the vasectomy has been performed, men should be told to remain in the clinic for 15–20 minutes to be assessed for possible scrotal bleeding or vaso-vagal reaction. It may be prudent to recommend that patients be driven home. Men should be instructed about proper wound and scrotal care and short-term physical limitations. Men should be told how to collect the semen sample (completeness and type of container) and reminded of the importance of submitting the sample to the laboratory in a timely fashion (within 30–60 minutes after producing the sample). They should also be told that semen samples should be collected after an abstinence period of two or more days and no more than seven days, and maintained at body temperature before delivery to the laboratory. A list of local laboratories that perform proper post-vasectomy semen analysis should be given to the patient. The men must be reminded to use other contraceptive measures until post-vasectomy semen testing has confirmed absence of motile sperm.

5. Post-vasectomy semen testing

The post-vasectomy semen analysis should be performed on the whole (unprocessed) semen and on the centrifuged semen to confirm the absence of low numbers of motile sperm. The laboratory should give an estimation of sperm concentration or numbers of spermatozoa observed per high-power field (×400 magnification).28–30

It is important to recognize that compliance with post-vasectomy semen testing is a significant issue, with up to 30% of men failing to submit a single sample.31,32

One vs. two post-vasectomy samples

Surveys have shown significant variability in the post-vasectomy testing protocols.33 Most agree that a single azoospermic semen sample is sufficient to deem the vasectomy effective.30,34 However, because spermatozoa are detected in 10–40% of the three-month post-vasectomy samples (the percent depends on the vasectomy technique and the accuracy of the semen analysis), it may be necessary for up to 40% of the men to submit a second semen sample.25,35 As such, requesting two semen samples at the onset may be more efficient, as this may reduce the number of post-vasectomy counselling sessions (e.g., phone calls or office visits), but this may also reduce the overall compliance.32

Recommendation: The evaluation of two post-operative semen samples is a better predictor of success than the evaluation of a single semen sample (Grade C).

Timing of post-vasectomy testing

Although most studies suggest that post-vasectomy testing be conducted at three months after vasectomy, the issue remains debatable, with some studies suggesting earlier examinations (with determination of failure based on the presence of motile sperm) and others proposing later examinations.32,36,37 The difficulty in establishing a set time point for semen testing stems largely from the variable success of the vasectomy occlusion techniques.25 Azoospermia is achieved much later with the ligation (and excision) compared to the cautery or fascial interposition techniques.25,35,36 The argument in favour of waiting at least three months is that this will reduce the number of false positive samples and minimize the need for repeat laboratory assessment and counselling.37

Recommendation: Post-vasectomy testing should be conducted three months after vasectomy (Grade C).

6. Interpreting and communicating results

Azoospermia or rare immotile sperm (<100 000 per ejaculate) as an indication of successful vasectomy

Contraceptive measures may be abandoned after the men have produced one azoospermic or two ejaculates with rare (<100 000) immotile spermatozoa. It is the physician’s responsibility (not the laboratory’s) to communicate these results to the patient and measures should be taken to ensure that patients not be lost to followup (e.g., provide followup phone calls to remind patients). Physicians must also remind couples about the risk of late failure (∼1/2000) despite azoospermia or rare immotile sperm on initial testing.

It is estimated that approximately 20–40% of samples have rare non-motile sperm at three months post-vasectomy, with a lower percentage having non-motile sperm at six months.31,35 When there is doubt regarding the analysis, physicians may want to contact the laboratory and confirm that there was no reporting error (i.e., that the sample was incorrectly labeled as “non-motile”). The literature has suggested that the risk of pregnancy occurring from these nonmotile sperm is small, perhaps no more than the risk of late pregnancy after two azoospermic semen samples as a result of spontaneous re-canalization.28,29 Similarly, rare non-motile sperm can appear in the ejaculate one year or more after vasectomy, with no increased risk of failure (pregnancy or motile sperm). Therefore, repeat semen testing in men with rare non-motile sperm is unnecessary because pregnancy is very unlikely to occur in this setting.

Recommendation: One postoperative azoospermic or two postoperative severely oligozoospermic semen samples (<100 000 immotile spermatozoa per ejaculate) are indicators of successful vasectomy (Grade C).

Motile sperm or large numbers of immotile sperm as a measure of failure

If any motile sperm or substantial numbers of immotile spermatozoa (>100 000) are detected, the physician must inform the patient to continue the use of other contraceptive measures and request that a repeat semen analysis be performed. A repeat vasectomy is indicated when there is persistence of motile sperm or large numbers of non-motile sperm in the ejaculate. However, no long-term studies have evaluated the risk of pregnancy in this setting.

Recommendation: Presence of any motile sperm or substantial numbers of immotile spermatozoa (>100 000) in the semen is an indication of vasectomy failure (Grade C).

Summary

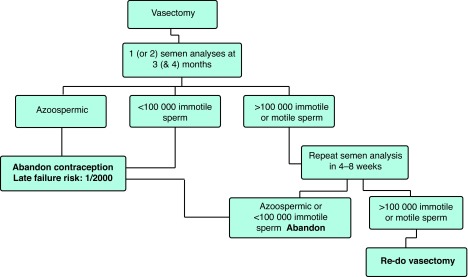

Vasectomy is a safe and effective method of birth control. The NSV technique is associated with a lower risk of early postoperative complications and the use of cautery or fascial interposition will reduce the risk of contraceptive failure. Post-vasectomy testing should consist of examination of one or two semen samples at approximately three (and four months) after vasectomy. The laboratory should examine a freshly produced seminal fluid specimen by direct microscopy and if no sperm are seen, the centrifuged sample should be examined for the presence of motile and non-motile spermatozoa. Other contraceptive measures may be abandoned after the production of one azoospermic ejaculate or two consecutive ejaculates with fewer than 100 000 immotile spermatozoa. Couples must be counselled (both pre- and postoperatively) about the risks of early and late failure (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Proposed algorithm for post-vasectomy testing protocol.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors report no competing personal or financial interests.

References

- 1.Philp T, Guillebaud J, Budd D. Complications of vasectomy: Review of 16 000 patients. Br J Urol. 1984;56:745–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1984.tb06161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Awsare NS, Krishnan J, Boustead GB, et al. Complications of vasectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2005;87:406–10. doi: 10.1308/003588405X71054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sokal D, Irsula B, Chen-Mok M, et al. A comparison of vas occlusion techniques: Cautery more effective than ligation and excision with fascial interposition. BMC Urol. 2004;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sokal D, Irsula B, Hays M, et al. Vasectomy by ligation and excision, with or without fascial interposition: A randomized, controlled trial. BMC Med. 2004;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benger JR, Swami SK, Gingell JC. Persistent spermatozoa after vasectomy: A survey of British urologists. Br J Urol. 1995;76:376–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwingl PJ, Guess HA. Safety and effectiveness of vasectomy. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:923–36. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(00)00482-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Philp T, Guillebaud J, Budd D. Late failure of vasectomy after two documented analyses showing azoospermic semen. Br Med J. 1984;289:77–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6437.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leslie TA, Illing RO, Cranston DW, et al. The incidence of chronic scrotal pain after vasectomy: A prospective audit. BJU Int. 2007;100:1330–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samplaski MK, Daniel A, Jarvi K. Vasectomy as a reversible form of contraception for select patients. Can J Urol. 2014;21:7234–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu LH, Kang R, He J, et al. Vasectomy and risk of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Andrology. 2015;3:643–9. doi: 10.1111/andr.12040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deneux-Tharaux C, Kahn E, Nazerali H, et al. Pregnancy rates after vasectomy: A survey of U.S. urologists. Contraception. 2004;69:401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson JE, Jamieson DJ, Warner L, et al. Contraceptive sterilization among married adults: National data on who chooses vasectomy and tubal sterilization. Contraception. 2012;85:552–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santomauro M, Masterson J, Marguet C, et al. Demographics of men receiving vasectomies in the U.S. military 2000–2009. Curr Urol. 2012;6:15–20. doi: 10.1159/000338863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potts JM, Pasqualotto FF, Nelson D, et al. Patient characteristics associated with vasectomy reversal. J Urol. 1999;161:1835–9. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68819-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee RK, Li PS, Goldstein M. Simultaneous vasectomy and varicocelectomy: Indications and technique. Urology. 2007;70:362–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper TP. Use of EMLA cream with vasectomy. Urology. 2002;60:135–7. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(02)01632-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas AA, Nguyen CT, Dhar NB, et al. Topical anesthesia with EMLA does not decrease pain during vasectomy. J Urol. 2008;180:271–3. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White MA, Maatman TJ. Comparative analysis of effectiveness of two local anesthetic techniques in men undergoing no-scalpel vasectomy. Urology. 2007;70:1187–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aggarwal H, Chiou RK, Siref LE, et al. Analysis of pain during anesthesia and no-scalpel vasectomy procedure among three different local anesthetic techniques. Urology. 2009;74:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook LA, Pun A, van Vliet H, et al. Scalpel vs. no-scalpel incision for vasectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Apr 18;:CD004112. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004112.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christensen P, al-Aqidi OA, Jensen FS, et al. Vasectomy: A prospective, randomized trial of vasectomy with bilateral incision versus the Li vasectomy. Ugeskrift for laeger. 2002;164:2390–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sokal D, McMullen S, Gates D, et al. A comparative study of the no-scalpel and standard incision approaches to vasectomy in five countries. The Male Sterilization Investigator Team. J Urol. 1999;162:1621–5. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook LA, van Vliet H, Lopez LM, et al. Vasectomy occlusion techniques for male sterilization. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Apr 18;:CD003991. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd003991.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen-Mok M, Bangiwala SI, Dominik R, et al. Termination of a randomized, controlled trial of two vasectomy techniques. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2003;24:78–84. doi: 10.1016/S0197-2456(02)00267-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labrecque M, Nazerali H, Mondor M, et al. Effectiveness and complications associated with two vasectomy occlusion techniques. J Urol. 2002;168:2495–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haldar N, Cranston D, Turner E, et al. How reliable is a vasectomy? Long-term followup of vasectomized men. Lancet. 2000;356:43–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02436-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemack GE, Goldstein M. Presence of sperm in the pre-vasectomy reversal semen analysis: Incidence and implications. J Urol. 1996;155:167–9. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66584-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies AH, Sharp RJ, Cranston D, et al. The long-term outcome following ‘special clearance’ after vasectomy. Br J Urol. 1990;66:211–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1990.tb14907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Knijff DW, Vrijhof HJ, Arends J, et al. Persistence or reappearance of nonmotile sperm after vasectomy: Does it have clinical consequences? Fertil Steril. 1997;67:332–5. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81920-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffin T, Tooher T, Nowakowski K, et al. How little is enough? The evidence for post-vasectomy testing. J Urol. 2005;174:29–36. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000161595.82642.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chawla A, Bowles B, Zini A. Vasectomy followup: Clinical significance of rare non-motile sperm in the postop semen analysis. Urology. 2004;64:1212–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bodiwala D, Jeyarajah S, Terry TR, et al. The first semen analysis after vasectomy: Timing and definition of success. BJU Int. 2006;99:727–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haws JM, Morgan GT, Pollack AE, et al. Clinical aspects of vasectomies performed in the U.S. in 1995. Urology. 1998;52:685–91. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(98)00274-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Badrakumar C, Gogoi NK, Sundaram SK. Semen analysis after vasectomy: When and how many? BJU Int. 2000;86:479–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2000.00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barone MA, Nazerali H, Cortes M, et al. A prospective study of time and number of ejaculations to azoospermia after vasectomy by ligation and excision. J Urol. 2003;170:892–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000075505.08215.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards IS. Earlier testing after vasectomy, based on the absence of motile sperm. Fertil Steril. 1993;59:431–6. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)55706-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Labrecque M, St-Hilaire K, Turcot L. Delayed vasectomy success in men with a first post-vasectomy semen analysis showing motile sperm. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:1435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]