Abstract

We used a combination of genomic techniques to monitor chromosomal evolution across hundreds of generations as Escherichia coli adapted to growth-limiting concentrations of either lactulose, methyl-galactoside, or a 72:28 mixture of the two. DNA microarrays identified 8 unique duplications and 16 unique deletions among 42 evolvants from 23 chemostat experiments. Each mutation was confirmed by sequencing PCR-amplified flanking genomic DNA and, except for one deletion, an insertion sequence was found at the break point. vPCR of insertion sequences identified these same mutations and 16 additional insertions (all confirmed by sequencing). The pattern of genomic evolution is highly reproducible. Statistical analyses show that duplications at lac and mutations in mgl are adaptations specific to lactulose and to methyl-galactoside, respectively. Adaptation to mixed sugars is characterized by similar mutations, but lac duplications and mgl mutations usually arise in different backgrounds, producing ecological specialists for each sugar. This suggests that an antagonistic pleiotropic tradeoff between duplications at lac and mutations in mgl retards the evolution of generalists. Other mutations that repeatedly appear in replicate experiments are adaptations to the chemostat environment and are not specific to one or the other sugar.

We have taken advantage of the repeatability of laboratory adaptation to investigate the roles of insertion sequences (IS) in the evolution of resource specialization.

The repeatability of laboratory adaptation is well documented (1–11) and is perhaps attributable to using large populations with simple ecologies. Large populations reduce the role of chance in evolution: random genetic drift is minimized, whereas mutation, always erratic in small populations, produces numerous allelic variants with each generation. In simple constant environments, selection becomes focused with great intensity on a few key genes. This makes experimental evolution far more reproducible than typically envisioned for small populations inhabiting complex natural environments (12). Reproducibility makes possible rigorous tests of adaptive hypotheses. For example, Cooper et al. (13) used DNA expression macroarrays to identify parallel changes in the expression profiles of two evolvants. Guided by the observation that many of the genes with changed expression belong to the ppGpp and CRP regulons, they identified a mutation in spoT in one population that, when reintroduced into the ancestral genetic background, increased fitness as well as reproducing many of the changes in expression.

IS elements are small (1- to 2-kb) segments of DNA capable of transposing within and between prokaryotic replicons (14). A major source of insertional mutations and chromosomal rearrangements (15), their evolutionary significance is a subject of perennial interest (16–20). Patterns of sequence polymorphism among natural isolates of Escherichia coli suggest a brisk turnover of elements (21), with both the numbers and locations of elements differing among even closely related strains (22–28). These observations suggest that IS elements are an important source of genetic variation on which selection acts.

We have been experimenting with the evolution of specialists and generalists using laboratory populations of E. coli competing for two sugars. Theory predicts, and experiments demonstrate, that two specialists may coexist whenever differential resource consumption generates stabilizing frequency-dependent selection (29). Small changes in fitness are predicted to destabilize the polymorphism, resulting in a selective sweep to monomorphism. Yet long-term cultures retain two resource specialists (30). More remarkably, strains sometimes switch resource specializations. The repeated independent evolution of resource switching and of new polymorphisms displaying greater specialization toward each sugar strongly suggests the existence of antagonistic pleiotropy.

We take an explicitly genomics approach to identify all large (>1-kb) deletions, duplications, and IS transpositions that arise during adaptation to mixed sugars. DNA microarrays are used to identify gene duplications and deletions, real-time PCR (rtPCR) is used to estimate copy numbers, and vectorette PCR (vPCR) is used to identify all IS transpositions in 42 evolved genomes. In so doing, we define the genomic roles played by IS elements in the evolution of resource specialization.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains. E. coli strains TD2 and TD10 carry different lac alleles but are otherwise genetically identical (29, 30). TD2 is fitter during competition for pure lactulose, whereas TD10 is fitter during competition for pure methyl-galactoside. Strains designated DD (e.g., DD2298) were isolated from 23 long-term chemostat experiments in which cultures consumed lactulose, methyl-galactoside, or a 72:28 mixture of both. Samples were taken every 48 generations and frozen at –80°C in 16% glycerol for future reference, as were all purified isolates. Strains designated R (e.g., TD10R) carry a selectively neutral genetic marker, fhuA–, that confers resistant to the bacteriophage T5 (31).

Microarrays. Duplications and deletions in genomic DNA (gDNA) were identified by using parallel two-color hybridization to whole-genome E. coli MG1655 spotted DNA microarrays, designed, printed, and probed as described (32, 33), and containing discrete sequence elements corresponding to 98.8% of all annotated ORFs (http://bmb.med.miami.edu/EcoGene/EcoWeb). Cy3 dUTP- and Cy5 dUTP-(Amersham Pharmacia) labeled probes were made from 0.5–1.0 μg of gDNA, extracted with a DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), and sheared by sonication to ≈500–1,000 bp, by extending random hexamers (Roche Applied Science) using Klenow (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), and purified by using a Microcon-30 (Millipore).

Replicate experiments were performed with a dye-swap (34) and analysis of significance carried out by using array experiments with two, three, and four DNA samples from replicate populations. After fitting the intensities into the fixed ANOVA model (35), adjusted relative expression levels (“mean intensity” + “sample-specific variance” + “experimental error”) were extracted and subjected to an exploratory analysis of false discovery rates (FDR) with a modified t test, B statistic (36). Significant differences in intensities were identified by using a 5% FDR cutoff.

Standard PCR and DNA Sequencing. Primers, designed using the genomic sequence of the K12 strain MG1665 (26), were used to amplify those regions identified by microarray analysis as flanking deletions or forming the junctions of tandem duplications. Routine PCR used Herculase DNA polymerase (Stratagene) with amplicons, purified using StrataPCR purification columns, sequenced at the Advanced Genetic Analysis Center at the University of Minnesota.

rtPCR. Gene duplications were verified by rtPCR by using the 2-ΔΔCt method (37). Primers were designed to amplify 100-bp fragments internal to either lacY or ymfD (a single-copy reference gene) using the SYBR green PCR core reagent kit (PE Biosystems). Reactions contained 75 ng of gDNA and 900 nM of each primer and were carried out in triplicate by using an ABI PRISM 7900 (Applied Biosystems) instrument with 2 min at 50°C and 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. Cycle threshold (Ct) values decrease linearly as the amount of DNA template (logarithmic value) increases. The difference in Ct values between lacY and ymfD, ΔCt, remains constant, indicating that copy number is robustly estimated across a broad range of gDNA concentrations.

vPCR. IS elements were mapped onto the K12 genome by sequencing gDNA fragments produced by vPCR (38). gDNA (0.5 μg) was digested overnight by using 10 units of RsaI in 50 μl of 1 × NEB (New England Biolabs) buffer no. 1 at 37°C. Next, 2 μl of the anchor bubble unit (38), 1 μl of 10 mM ATP, and 2 μl (800 units) of T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) were added and the reaction incubated for five cycles at 20°C for 1 hour followed by 37°C for 30 min. PCRs contained 1× Qiagen Multiplex PCR Master Mix, 0.2 μM outward IS primer and vectorette primer and 2 ng of DNA template. vPCR amplified products were separated in a 1.4% agarose gel, excised, purified, and sequenced. Fragments that comigrate on agarose gels with other similarly sized products produce bands that stain brighter and/or appear broad because of the additional DNA present. These can be identified by digesting gDNA with a different restriction enzyme (e.g., BstU 1) before vPCR or, if the location of the IS has been previously identified, confirmed by sequencing standard PCR products obtained by using primers complementary to known flanking sequences.

Results

Ancestral Genomes. All 37 IS elements found in the published genomic sequence of MG1655 (26) are found in our laboratory wild-type K12 strain CGSC6300 (an MG1655 obtained from the E. coli Genetic Stock Center, Yale University, New Haven, CT). Strains TD2 and TD10 lack element IS1-5 found in MG1655 and CGSC6300. Strains CGSC6300, TD2, and TD10 carry additional elements (Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), a consequence of their progenitors having been stored on agar slants at room temperature, conditions known to promote IS mobilization (22, 39).

The experimental strains TD2 and TD10 are genetically identical except for the regions surrounding their lac operons. DNA microarray analyses reveal that the genomic region between yahE and yahL is deleted in TD10. Sequenced PCR amplicons reveal that a 9.67-kb fragment in TD2 is replaced by IS1-b in TD10 (Fig. 1). Sequencing vPCR amplicons from TD10 also reveals an IS3-a insertion between betT and yahA. Both IS3-a and IS1-b were probably introduced along with the ECOR 16 lac operon during strain construction.

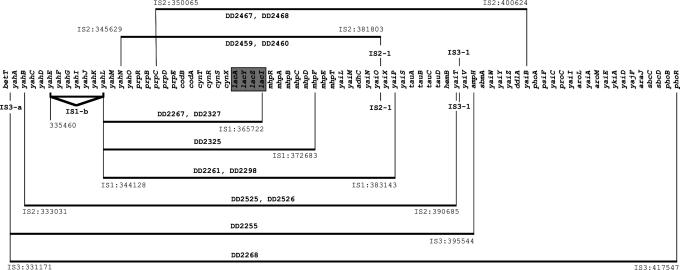

Fig. 1.

Duplications at lac always involve IS elements. Horizontal lines represent the extent of each duplication with the terminal IS elements located in base pairs on the MG1655 chromosome and DD numbers identifying the evolvants. Duplications above the chromosome are found in descendants of TD2, those below in descendants of TD10. Resident elements (bold typeface) are labeled above (TD2) and below (TD10) the chromosome. The lac operon is boxed in.

Evolved Genomes. A total of 50 isolates from 23 long-term chemostat adaptation experiments were analyzed. IS activity was monitored in 21 pairs of isolates from 15 long-term cultures (between 168 and 610 generations) by using microarrays and vPCR: four cultures were limited by lactulose alone, four cultures were limited by methyl-galactoside alone, and seven were limited by a 72:28 mixture of lactulose:methyl-galactoside (Table 1). Chemostats 20, 21, and 23, which contain cultures adapted to mixed resources, were sampled at multiple time points. Eight additional isolates, obtained from eight additional long-term cultures limited by single resources, were screened for lac duplications and mgl mutations only.

Table 1. Evolved strains.

| Chemostat | Adapted towards | Ancestor | Generation isolated | Strain | Fitness on lactulose* | Fitness on Me-Gal* | Iac duplications | Mutations in mgl/gaIS | Type II deletions | Insertions in cls | Other deletions | Other insertions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TD2 | 0 | TD2 | ||||||||||

| TD10R | 0 | TD10R | 0.91 ± 0.004 | 1.31 ± 0.004 | ||||||||

| 1 | LU | TD2 | 598 | DD2459 | IS2 | Yes | IS1 | |||||

| 1 | LU | TD2 | 598 | DD2460 | IS2 | Yes | Type IV | |||||

| 2 | LU | TD2R | 598 | DD2467R | IS2 | Yes | ||||||

| 2 | LU | TD2R | 598 | DD2468R | IS2 | Yes | IS5 | |||||

| 3 | LU | TD10 | 301 | DD2525 | IS2 | Yes | ||||||

| 3 | LU | TD10 | 301 | DD2526 | IS2 | Yes | ||||||

| 4 | LU | TD10 | 301 | DD2529 | ||||||||

| 4 | LU | TD10 | 301 | DD2530 | ||||||||

| 5 | LU | TD2 | 301 | DD2523 | —‡ | —‡ | ||||||

| 6 | LU | TD2 | 265 | DD2539 | Yes† | —‡ | —‡ | |||||

| 7 | LU | TD10 | 206 | DD2527 | Yes† | —‡ | —‡ | |||||

| 8 | LU | TD10 | 190 | DD2535 | —‡ | —‡ | ||||||

| 9 | MG | TD2 | 368 | DD2555 | mglA::IS1 | |||||||

| 9 | MG | TD2 | 368 | DD2556 | ΔgaIS-yeiB | uvrY::IS1:yecF | ||||||

| 10 | MG | TD2 | 332 | DD2557 | gaIS::IS1 | |||||||

| 10 | MG | TD2 | 332 | DD2558 | gaIS::IS1 | |||||||

| 11 | MG | TD10 | 336 | DD2559 | ΔgaIS-yeiA | |||||||

| 11 | MG | TD10 | 336 | DD2560 | ΔgaIS-mglA | |||||||

| 12 | MG | TD10 | 441 | DD2561 | ΔgaIS-yeiA | Yes | ||||||

| 12 | MG | TD10 | 441 | DD2562 | gaIS.IS1 | Yes | ||||||

| 13 | MG | TD2 | 309 | DD2552 | —‡ | —‡ | ||||||

| 14 | MG | TD2 | 168 | DD2554 | gaIS::IS1 | —‡ | —‡ | |||||

| 15 | MG | TD10 | 251 | DD2563 | gaIS::IS1 | —‡ | —‡ | |||||

| 16 | MG | TD10 | 251 | DD2565 | gaIS::IS1 | —‡ | —‡ | |||||

| 17 | MIX | TD2R | 477 | DD2509R | ||||||||

| 17 | MIX | TD2 | 477 | DD2510R | mglA::IS1 | |||||||

| 18 | MIX | TD2R | 441 | DD2511R | ||||||||

| 18 | MIX | TD2 | 441 | DD2512 | ||||||||

| 19 | MIX | TD10 | 471 | DD2268 | 1.23 ± 0.02 | 1.22 ± 0.01 | IS3 | gaIS::IS1 | Yes | Type III | narG::IS186 | |

| 19 | MIX | TD10R | 471 | DD2269R | ||||||||

| 20 | MIX | TD2R | 260 | DD2253R | ||||||||

| 20 | MIX | TD10 | 260 | DD2255 | 1.11 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.01 | IS3 | Yes | Type III | |||

| 20 | MIX | TD2R | 500 | DD2257R | Yes | Type IV | ||||||

| 20 | MIX | TD10 | 500 | DD2259 | Yes | Type III | ||||||

| 21 | MIX | TD10R | 349 | DD2298R | 1.30 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | IS1 | |||||

| 21 | MIX | TD2 | 349 | DD2300 | Yes | uvrY:IS1:yecF | ||||||

| 21 | MIX | TD10R | 610 | DD2302R | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 1.26 ± 0.01 | Yes | IS1 | ||||

| 21 | MIX | TD2 | 610 | DD2304 | Yes | IS2 | uvrY:IS1:yecF | |||||

| 22 | MIX | TD10R | 335 | DD2261R | 1.36 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | IS1 | Yes | IS1 | |||

| 22 | MIX | TD2 | 335 | DD2262 | ||||||||

| 23 | MIX | TD10 | 123 | DD2270 | gaIS::IS1 | |||||||

| 23 | MIX | TD10R | 123 | DD2324R | 1.38 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | ||||||

| 23 | MIX | TD10 | 232 | DD2271 | gaIS::IS1 | |||||||

| 23 | MIX | TD10R | 232 | DD2325R | 1.52 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | IS1 | Yes | ||||

| 23 | MIX | TD10 | 411 | DD2272 | gaIS::IS1 | |||||||

| 23 | MIX | TD10R | 411 | DD2326R | Yes | |||||||

| 23 | MIX | TD10 | 471 | DD2279 | gaIS::IS1 | |||||||

| 23 | MIX | TD10R | 471 | DD2327R | 1.21 ± 0.01 | 0.58 ± 0.01 | IS1 | IS1 | ||||

| 23 | MIX | TD10 | 471 | DD2266 | gaIS::IS1 | b2625 | ||||||

| 23 | MIX | TD10R | 471 | DD2267R | 1.67 ± 0.001 | 0.39 ± 0.01 | IS1 | IS1 |

Fitness of TD10 with respect to TD2.

Duplications detected by rtPCR. ISs not identified.

Not investigated.

Evolved Duplications. DNA microarray analysis identified eight independent duplications among the evolved strains. All include the lac operon (Fig. 1), and all arose in the presence of environmental lactulose. The largest duplicated region covers 74 genes from yahA to phoB, the shortest only 18 genes from yahL to lacI. All duplicate the 13 genes between prpC and lacI. Sequencing PCR amplicons, obtained by using divergent primers to genes at the ends of each duplication, reveal that an IS element lies at every junction in the tandem arrays. Six of the eight duplications involve IS elements resident in the ancestors. Duplications appear more often in TD10 than TD2, possibly because two additional nearby IS elements (IS3-a and IS1-b) augment duplication at lac.

Copy numbers of the duplicated lacY genes (encoding the lactose permease) were determined by using quantitative rtPCR. rtPCR estimates a mean copy number of 1.2 ± 0.06 lacY genes per genome in 10 isolates known not to carry duplications and a mean copy number of 3.41 ± 0.33 lacY genes per genome in 13 isolates identified as carrying lac duplications (Table 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), excluding DD2527, which carries an unusually large number (≈11) of lacY duplications. That duplications typically carry two additional copies of lacY is certainly an underestimate. Tandem arrays are inherently unstable and rapidly contract once selection is relaxed (ref. 15; all cultures were grown in minimal glucose medium). The large standard error associated with duplications reflects not only variation in amplification during growth in the chemostat but also variation generated as arrays contract during growth outside the chemostat.

Evolved Deletions. DNA microarray analysis detected gene deletions in four regions of the E. coli chromosome (Fig. 2). All but one are associated with IS1 or IS3 elements. Presumably, the latter are formed by replicative transposition of the IS into a neighboring gene followed by resolution of the resulting cointegrate to produce the observed deletion (14).

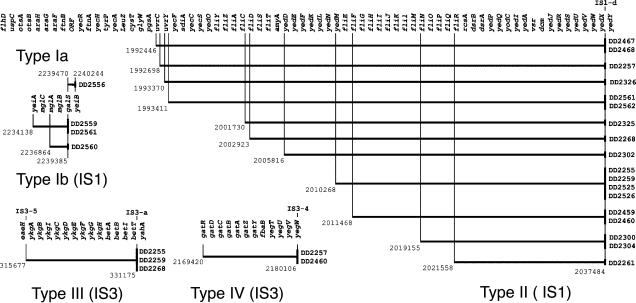

Fig. 2.

Four types of deletions always involve IS elements. Horizontal lines represent the extent of each deletion with the terminal IS elements located in base pairs on the MG1655 chromosome and DD numbers identifying the evolvants. Resident elements (bold typeface) are labeled above the chromosome. Unique to TD10 is IS3-a, which is associated with type III deletions and lac duplications in strains DD2255 and DD2268 but only with a type III deletion in DD2259.

The type Ia deletion is unique in not being associated with an IS. We found no evidence of sequence similarity, such as imperfect direct repeats, that might account for a deletion in this region. Type Ib deletions share a common IS1 element in galS (the mgl galactose transport operon repressor, ref. 40) that is not present in either parental strain (TD2 or TD10) but that evidently arose in the TD10 culture used as the frozen stock. Strains DD2559 and DD2561 are presumably derived from a common ancestor in which replicative transposition and cointegrate resolution of the IS1 in yeiA produced the observed 5.2-kb deletion of the entire mgl operon. In strain DD2560, the same IS1 insertion in galS resulted in a 2.5-kb deletion that removed all of mglB and much of mglA but left mglC intact.

Type II deletions are by far the most frequent, with 17 isolates representing a minimum of 11 unique events. DNA microarrays suggest that, although independently derived deletions vary in size from 18.3 to 45.0 kb, all end between yedX and yedY. Sequenced PCR amplicons confirm that the right breakpoint is always the IS1-d found at base pair 2037484 in the parental strains TD2 and TD10 (but not MG1655 or CGSC6300). Evidently, replicative transposition leftwards followed by resolution of the resulting cointegrates produced a family of deletions sharing a common breakpoint at IS1-d on the right.

Just to the right of all type II deletions lies IS5-7. Deletions extending in from IS5-7 are not observed, presumably because they remove several genes important to fitness (gnd, gluconate dehydrogenase, ref. 41; hisOGDCBHAFI, histidine biosynthesis, ref. 42). Deletions from IS5-6 and IS2-3, which are closer in, would contain no genes known to be deleterious, although one or more uncharacterized ORFs may be so.

Type III deletions are formed by recombination between two resident IS elements: IS3-1 found in all K12 strains and IS3-a, which is unique to TD10. The deleted region includes the entire bet operon encoding the osmoregulatory choline-glycine betaine pathway (43).

Both type IV deletions, isolated from independent experiments, are descended from a common frozen stock. The 10.69-kb deletion begins at the IS3-4 in gatR (the galactitol/dulcitol operon repressor), found in all K12 strains, proceeds through the entire gat operon (44) and the adjacent fbaB (a class II fructose bisphosphate aldolase also involved in galactitol metabolism) and several ORFs of unknown function to end in yegW.

Evolved Transpositions. IS transpositions were detected by using vPCR. Sixteen independent transpositions were detected among the 42 isolates: 11 IS1 transpositions, 3 IS5 transpositions, 1 IS2 transposition, and 1 IS186 transposition (Table 2). Sequencing amplicons obtained by using primers complementary to flanking gDNAs confirm that these 16 IS elements are not associated with duplications and deletions. Insertions were repeatedly found in a limited number of genes. IS1 transposed thrice into mglA and four times into galS. The galS insert at base pair 2239385, found as a simple insertion in four chemostats (12, 16, 20, and 24), also helped produce both type IV deletions in the mgl operon following additional transpositions into yeiA and mglA (chemostats 11 and 12). IS1 also transposed four times into cls (encoding a synthase for cardiolipin, a major component of E. coli membranes, ref. 45). IS2 and IS5 each transposed once into cls. IS5 also transposed into yfjI, and between uvrY and yecF. IS186 transposed into narG (a subunit of the dissimilatory nitrate reductase used during anaerobic respiration; ref. 46).

Table 2. IS insertions.

| Strains | Element | Position, bp | Orientation | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DD2268 | IS186 | 1282372 | - | narG |

| DD2459 | IS1 | 1305418 | + | cls |

| DD2302 | IS1 | 1305723 | + | cls |

| DD2267 | IS1 | 1305857 | - | cls |

| DD2261, DD2327 | IS1 | 1305866 | +,- | cls |

| DD2304 | IS2 | 1306535 | - | cls |

| DD2468 | IS5 | 1306585 | + | cls |

| DD2300, DD2304, DD2556 | IS5 | 1993421 | -,-,+ | uvrY/yecF |

| DD2510 | IS1 | 2236207 | - | mglA |

| DD2555 | IS1 | 2236671 | + | mglA |

| DD2557, DD2558 | IS1 | 2239250 | - | galS |

| DD2270 | IS1 | 2239391 | + | galS |

| DD2266, DD2268, DD2271, | IS1 | 2239385 | -,-,- | galS |

| DD2272, DD2279, DD2562, | -,-,- | |||

| DD2563 | - | |||

| DD2554 | IS1 | 2239695 | + | galS |

| DD2565 | IS1 | 2239768 | + | galS |

| DD2266 | IS5 | 2758187 | + | b2625 |

Repeatedly Isolated Mutations. Identical mutations isolated from different experiments are restricted to derivatives of TD2 only or to derivatives of TD10 only. They are likely identical by descent; originally present at low frequencies in frozen ancestral stocks, the parallel rise in frequencies in replicate experiments is attributable to natural selection.

Discussion

Statistical analyses suggest that lac duplications are adaptations to lactulose but not to methyl-galactoside, and that mutations at mgl are adaptations to methyl-galactoside but not to lactulose. Duplications, common among strains evolved on pure lactulose (found in five of eight chemostats, Table 1), are never seen in strains evolved on pure methyl-galactoside (0 of 8 chemostats; P = 0.013 by a one-tailed Fisher's exact test). Likewise, mutations at mgl are common among strains evolved on pure methylgalactoside (found in seven of eight chemostats, including IS element insertions in galS and mglA and type I deletions) but are never seen in strains evolved on pure lactulose (0 of 8 chemostats; P = 0.0007 by a one-tailed Fisher's exact test). These repeated associations between gene and environment indicate that lac duplications and mgl mutations are not simply adaptations to the chemostat environment in general but are instead specific adaptations to limitation by specific sugars.

Metabolic control analysis predicts that lac duplications should increase fitness during starvation on pure lactulose (47), just as they do during starvation on pure lactose (1). Metabolic control analysis also predicts that lac duplications should increase fitness during starvation on pure methyl-galactoside. However, strains adapted on methyl-galactoside never carry lac duplications. Instead, they either carry insertions in galS that cause the MglABC transporter (which efficiently translocates methyl-galactose but not lactulose, ref. 40) to be constitutively expressed or they carry mutations in mgl (type I deletions of mgl or IS1 insertions in mglA) that abolish function, forcing translocation through the lacY permease or perhaps through some other as-yet-unidentified transporter. Evidently, galS has pleiotropic fitness effects beyond those possibly associated with mgl expression.

Whereas adaptation on pure sugars favors the evolution of specialists, adaptation on mixed sugars provides an opportunity for generalists to evolve. Yet generalists are rare: only 1 has been isolated from 13 chemostat cultures grown on mixed sugars (including data from ref. 30). Strain DD2268 (Table 1) carries both a duplication at lac and an insertion in galS and is fitter than DD2269R, a very rare cohabiting partner, on both sugars. One pair of strains shows no evidence of adaptation toward either resource: even though DD2302R and DD2304 carry type II deletions and IS insertions at cls, neither carries a lac duplication or a mutation at mgl. Their relative fitnesses (on pure sugars) remain virtually unchanged after 610 generations of adaptation (Table 1). Mostly, however, adaptation to mixed sugars is characterized by the evolution of specialists (Table 1 and ref. 30), each fitter than its cohabiting partner on one sugar and less fit on the other.

Of the three mechanisms capable of producing specialists (mutation accumulation, independent specialization, and antagonistic pleiotropy), only antagonistic pleiotropy provides a ready explanation for the evolution of specialists, the near absence of generalists, and the phenomenon of resource switching (30). The latter occurs when specialists engaged in a balanced polymorphism during competition for mixed sugars swap resource preferences. For example, DD2261 (a descendant of the methylgalactoside specialist TD10) is fitter on pure lactulose than its paired competitor DD2262 (a descendant of the lactulose specialist TD2): similarly, DD2262 is fitter than DD2261 on pure methyl-galactoside. Mutation accumulation is eliminated by virtue of the design of the experiment: mutations that are selectively neutral with respect to one sugar and deleterious with respect to the second must be purged from cultures grown on mixed resources. Independent specialization, wherein mutations advantageous on one sugar are selectively neutral on the second, does not provide a mechanism to explain the scarcity of generalists that should be strongly favored in cultures growing on mixed resources (30).

Genomic analysis provides clues to the molecular basis of antagonistic pleiotropy. Resource switching in descendants of TD10 is always associated with duplications at lac– duplications that are specifically associated with adaptation to lactulose (Table 1). Theory (30) dictates that mutations causing a switch to methyl-galactoside must arise in TD2 for a balanced polymorphism to be maintained. An IS1 insertion in the galS of DD2270 offers the tantalizing suggestion that mutations increasing expression of mgl and that are associated with adaptation to methyl-galactoside (Table 1), are just those mutations (several other TD2 descendants that have switched to methyl-galactoside have point mutations in galS; unpublished observations). These results suggest that overexpressing lac and mgl in the same cell is deleterious. The one exception is the generalist DD2268, which carries both these mutations. Perhaps other changes in its genome ameliorate the impact of the proposed tradeoff.

Not all selected mutations affect resource use. Specialization is not associated with insertions at cls (including strains adapted to mixed sugars, P = 0.08 by a one-tailed Fisher's exact test) or with type II deletions (including strains adapted to mixed sugars, P = 0.14 by a one-tailed Fisher's exact test). Insertional inactivation of cls, which encodes cardiolipin synthase (48), affects many membrane functions (49–52), any one of which might be a target of selection. Motility is pointless in the well-stirred environment of a chemostat. By removing flagellar genes, type II deletions allow energy and resources to be diverted toward essential cell functions. Indeed, many “wild-type” laboratory strains are spontaneous nonflagellate mutants (53). Other genes removed by all type II deletions may also affect fitness: rcsA (an activator of colanic acid capsule synthesis, ref. 54), dsrA (an antisense RNA, ref. 55), vsr and dcm (very short patch repair, ref. 56), and hchA (yedU, chaperone Hsp31, ref. 57). The deletion of the rpoS translational activator, dsrA, is particularly interesting given that rpoS mutants are commonly favored during starvation (3, 58).

Although type III and IV deletions and the IS5 insertion between uvrY and yecF are too rare for statistical tests of association with selective regime, their repeated appearance in replicate experiments suggests some selective advantage. Type IV deletions undoubtedly save energy and resources by removing a galactitol operon rendered constitutive in all K12 strains by an IS3 insertion in its gatR repressor. The advantages conferred by type III deletions and the IS5 insertion near uvrY are not obvious. Several unique mutations, an IS186 insertion in narG and an IS5 insertion into b2625, may be advantageous, or they may have simply hitchhiked with advantageous mutations elsewhere in the genome.

Of 22 unique duplications and deletions, only 1 arose between a pair of elements already resident in a genome (type III deletion), 17 arose between a resident and a freshly transposed element, and 4 arose between a pair of freshly transposed elements (2 lac duplications and 2 type I deletions). Many independently arisen chromosomal rearrangements involve the same “strategically located” elements (e.g., IS1-d of type II deletions; see also ref. 10). Other nearby elements are not associated with genomic rearrangements, because they would produce highly deleterious mutations (e.g., IS1-5 and IS5-7 flanking type II deletions and possibly IS3-5 if duplicating the bet operon, removed by type III deletions, costs more than the benefit gained by duplicating lac). These observations suggest that the genomic locations of IS elements exert a marked influence on the pattern of genomic evolution over the short term but will have less effect over the long term (already 4 of 22 rearrangements involve freshly transposed pairs of elements).

We have demonstrated that IS movements are both major source of both genomic rearrangements and adaptive variation during adaptation and ecological specialization in laboratory environments. The extent to which these processes produce adaptive change in ecological niches, as in Shigella flexneri's recent shift from commensal to pathogen (28), remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We thank Betsy Martinez-Vaz for printing the arrays and Mark Lunzer for running the chemostats. We also thank Ben Kerr, Lauren Merlo, and Jeff Lawrence for thoughtful, constructive criticism. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants (to A.K., D.E.D., and A.M.D.).

Abbreviations: IS, insertion sequences; gDNA, genomic DNA; vPCR, vecterotte PCR; rtPCR, real-time PCR.

References

- 1.Horiuchi, T., Horiuchi, S. & Novick, A. (1963) Genetics 48, 157–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall, B. G. (1984) in Microorganisms as Model Systems for Studying Evolution, ed. Mortlock, R. P. (Plenum, New York), pp. 165–185.

- 3.Zambrano, M. M., Siegele, D. A., Almiron, M., Tormo, A. & Kolter, R. (1993) Science 259, 1757–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham, C. W., Jeng, K., Husti, J., Badgett, M., Molineux, I. J., Hillis, D. M. & Bull, J. J. (1997) Mol. Biol. Evol. 14, 113–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakatsu, C. H., Korona, R., Lenski, R. E., de Brujin, F. J., Marsh, T. L. & Forney, L. J. (1998) J. Bacteriol. 180, 4325–4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenzweig, R. F., Sharp, R. R., Treves, D. S. & Adams, J. (1994) Genetics 137, 903–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treves, D. S., Manning, S. & Adams, J. (1998) Mol. Biol. Evol. 15, 789–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Notley-McRobb, L. & Ferenci, T. (2000) Genetics 156, 1493–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wichman, H. A., Scott, L. A., Yarber, C. D. & Bull, J. J. (2000) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B 355, 1677–1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper, V. S., Schneider, D., Blot, M. & Lenski, R. (2001) J. Bacteriol. 183, 2834–2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riehle, M. M., Bennett, A. F. & Long, A. D. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 525–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gould, S. J. (1989) Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History (Norton, New York).

- 13.Cooper, T. F., Rozen, D. E. & Lenski, R. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1072–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahillon, J. & Chandler, M. (1998) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 725–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roth, J. R., Benson, N., Galitski, T., Haack, K., Lawrence, J. G. & Miesel, L. (1996) in Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology, ed. Neidhardt, F.C. (Am. Soc. Microbiol., Washington, DC), pp. 2256–2276.

- 16.Blot, M. (1994) Genetica 93, 5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlesworth, B., Sneigowski, P. & Stephan, W. (1994) Nature 371, 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papadopoulos, D., Schneider, D., Meier-Eiss, J., Arber, W., Lenski, R. E. & Blot, M. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3807–3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider, D., Duperchy, E., Coursange, E., Lenski, R. E. & Blot, M. (2000) Genetics 156, 477–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Notley-McRobb, L., Seeto, S. & Ferenci, T. (2002) Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B 270, 843–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawerence, J. G., Ochmann, H. & Hartl, D. L. (1992) Genetics 131, 9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green, L., Miller, R. D., Dykhuizen, D. E. & Hartl, D. L. (1984) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81, 4500–4504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawyer, S. A. & Hartl, D. L. (1986) Theor. Popul. Biol. 30, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawyer, S. A., Dykhuizen, D. E., DuBose, R. F., Green, L., Mutangadura-Mhlanga, T., Wolczyk, D. F. & Hartl, D. L. (1987) Genetics 115, 51–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall, B. G., Parker, L. L., Betts, P. W., DuBose, R. F., Sawyer, S. A. & Hartl, D. L. (1989) Genetics 121, 423–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blattner, F. R., Plunkett, G., III, Bloch, C. A., Perna, N. T., Burland, V., Riley, M., Collado-Vides, J., Glasner, J. D., Rode, C. K., Mayhew, G. F., et al. (1997) Science 277, 359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayashi, T., Makino, K., Ohnishi, M., Kurokawa, K., Ishii, K., Yokoyama, K., Han, C. G., Ohtsubo, E., Nakayama, K., Murata, T., et al. (2001) DNA Res. 8, 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin, Q., Yuan, Z., Xu, J., Wang, Y., Shen, Y., Lu, W., Wang, J., Liu, H., Yang, J., Yang, F., et al. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 4432–4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lunzer, M., Natarajan, A., Dykhuizen, D. E. & Dean, A. M. (2002) Genetics 162, 485–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dykhuizen, D. E. & Dean, A. M. (2004) Genetics, in press.

- 31.Dykhuizen, D. E. (1993) Methods Enzymol. 224, 613–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khodursky, A. B., Peter, B. J., Cozzarelli, N. R., Botstein, D., Brown, P. O. & Yanofsky, C. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 12170–12175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khodursky, A. B., Bernstein, J. A., Peter, B. J., Rhodius, V., Wendisch, V. F. & Zimmer, D. P. (2003) Methods Mol. Biol. 224, 61–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerr, M. K. & Churchill, G. A. (2001) Biostatistics 2, 183–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerr, M. K., Martin, M. & Churchill, G. A. (2000) J. Comput. Biol. 7, 819–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smyth, G. K., Yang, Y. H. & Speed, T. (2003) Methods Mol. Biol. 224, 111–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ingham, D. J., Beer, S., Money, S. & Hansen, G. (2001) BioTechniques 31, 132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riley, J. R., Butler, R., Olgilvie, D., Finniear, R., Jenner, D., Powell, S., Anand, R., Smith, J. C. & Markham, A. F. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 2887–2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naas, T., Blot, M., Fitch, W. M. & Arber, W. (1994) Genetics 136, 721–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin, E. C. C. (1996) in Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology, ed. Neidhardt, F. C. (Am. Soc. Microbiol., Washington, DC), pp. 307–342.

- 41.Hartl, D. L. & Dykhuizen, D. E. (1981) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78, 6344–6348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winkler, M. E. (1996) in Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology, ed. Neidhardt, F. C. (Am. Soc. Microbiol., Washington, DC), pp. 2256–2276.

- 43.Lamark, T., Røkenes, T. P., McDougall, J. & Støm, A. R. (1996) J. Bacteriol. 178, 1655–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nobelmann, B. & Lengeler, J. W. (1996) J. Bacteriol. 178, 6790–6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dowhan, W. (1997) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66, 199–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blasco F., Guigliarelli, B., Magalon, A., Asso, M., Giordano, G. & Rothery, R. A. (2001) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 58, 179–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dean, A. M. (1995) Genetics 139, 19–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tropp, B. E., Ragolia, L., Xia, W., Dowhan, W., Milkman, R., Rudd, K. E., Ivanisevic, R. & Savic, D. J. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177, 5155–5157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tropp, B. E. (1997) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1348, 192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pfeiffer, K., Gohil, V., Stuart, R. A., Hunte, C., Brandt, U., Greenberg, M. L. & Schägger, H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 52873–52880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Canet, S., Heyde, M., Portalier, R. & Laloi, P. (2003) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 225, 207–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van den Brink-van der Laan, E., Boots, J.-W. P., Spelbrink, R. E. J., Kool, G. M., Breukink, E., Killian, J. A. & de Kruijff, B. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185, 3773–3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.MacNab, R. M. (1996) in Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology, ed. Neidhardt, F. C. (Am. Soc. Microbiol., Washington, DC), pp. 123–145.

- 54.Ebel, W. & Trempy, J. E. (1999) J. Bacteriol. 181, 577–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hengge-Aronis, R. (2002) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66, 373–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lieb, M. (1991) Genetics 128, 23–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sastry, M. S., Korotkov, K., Brodsky, Y. & Baneyx, F. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 46026–46034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Notley-McRobb, L., King, T. & Ferenci, T. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 184, 806–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]