Abstract

Youth advocacy for obesity prevention is a promising but under-evaluated intervention. The aims of this study are to evaluate a youth advocacy program’s outcomes related to youth perceptions and behaviors, develop an index of youth advocacy readiness, and assess potential predictors of advocacy readiness. Youth ages 9–22 in an advocacy training program (n = 92 matched pairs) completed surveys before and after training. Youth outcomes and potential predictors of advocacy readiness were assessed with evaluated scales. All 20 groups who completed the evaluation study presented their advocacy projects to a decision maker. Two of six perception subscales increased following participation in the advocacy program: self-efficacy for advocacy behaviors (p < .001) and participation in advocacy (p < .01). Four of five knowledge and skills subscales increased: assertiveness (p < .01), health advocacy history (p < .001), knowledge of resources (p < .01), and social support for health behaviors (p < .001). Youth increased days of meeting physical activity recommendations (p < .05). In a mixed regression model, four subscales were associated with the advocacy readiness index: optimism for change (B = 1.46, 95 % CI = .49–2.44), sports and physical activity enjoyment (B = .55, 95 % CI = .05–1.05), roles and participation (B = 1.81, 95 % CI = .60–3.02), and advocacy activities (B = 1.49, 95 % CI = .64–2.32). The youth advocacy readiness index is a novel way to determine the effects of multiple correlates of advocacy readiness. Childhood obesity-related advocacy training appeared to improve youths’ readiness for advocacy and physical activity.

Keywords: Childhood obesity, Built environment, Nutrition, Physical activity, Policy

There is a consensus that solutions for childhood obesity prevention rely on broad-based actions for social, environmental, and political changes that can improve nutrition and physical activity environments and policies for whole populations [1, 2]. Increasing participation in citizen advocacy through training programs is a promising approach for advancing policy change consistent with obesity prevention, but such interventions have not been consistently evaluated [3–5]. Advocacy refers to the process of increasing support for, recommending, and arguing to promote a cause or policy [6–8]. Training can target theory-based constructs such as outcome expectancies, perceived self-efficacy, proxy efficacy, perceived policy control, leadership competence, and sense of community. These factors can influence advocacy perceptions, skills, and behaviors that include media contact, public participation, and vocalizing one’s beliefs to decision makers [9, 10]. Youth advocacy has the potential to influence changes to nutrition and physical activity environments and policies, as well as produce co-benefits for youth well-being [4].

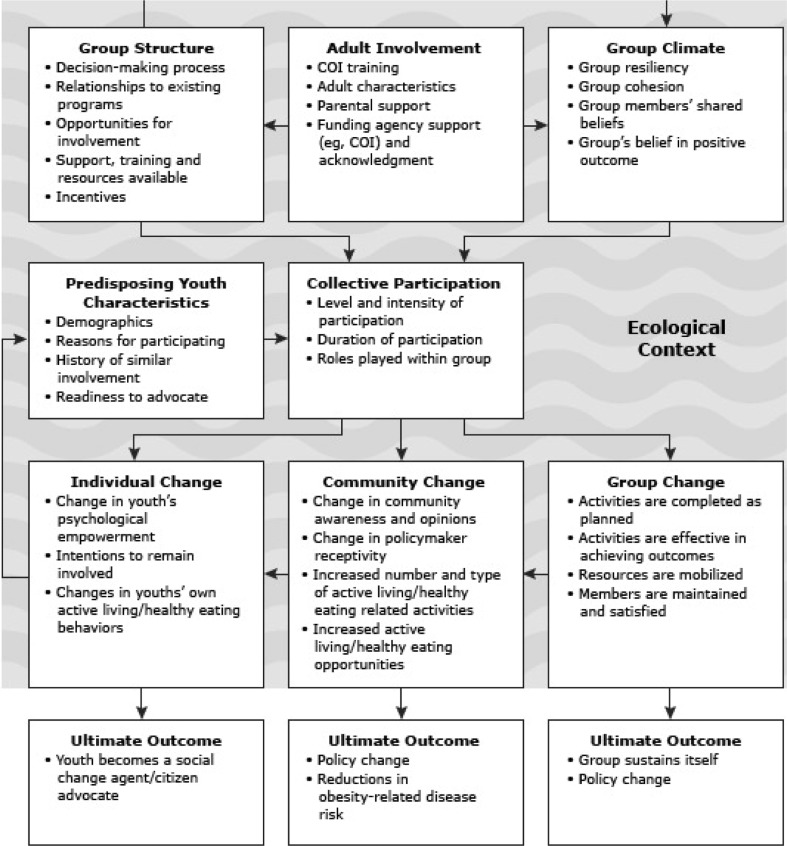

A previously published conceptual model by our group described individual, social, environmental, and policy-level factors and processes for youth advocacy for obesity prevention (Fig. 1) [3, 4]. Individual level dimensions of the model included self-efficacy [11], self-esteem [12], empowerment [13, 14], proxy efficacy [10, 15], perceptions, behavior change skills, and barriers, all of which influence nutrition, physical activity, and advocacy behaviors [11, 16]. Social-level factors in the model included social support, social capital, and group norms, with influences at the peer, family, and neighborhood levels. Youth advocacy group characteristics included group structure and climate, group cohesion, collective efficacy, group resiliency, sense of purpose, levels of and opportunities for responsibility, outcome efficacy, and decision-making processes [17, 18].

Fig 1.

A multilevel conceptual model of processes, evaluation targets, and outcomes of the YEAH! program, originally published in [3]

There are numerous evidence-based environmental and policy factors that could be targeted in advocacy efforts. Neighborhood built environment features have been identified as correlates of physical activity, including traffic volume and speed and proximity to parks and recreation facilities [19–21]. In the school environment, physical education classes, activity supervision, recreation facilities, school lunch quality, and vending machines have been targeted for changes to improve nutrition and physical activity outcomes [22, 23]. For instance, successful youth advocacy projects from this study’s policy evaluation led to adding a salad bar at a high school, having additional night lighting installed at a community center to increase pedestrian safety, and creating a female-only swim time at a YMCA [3].

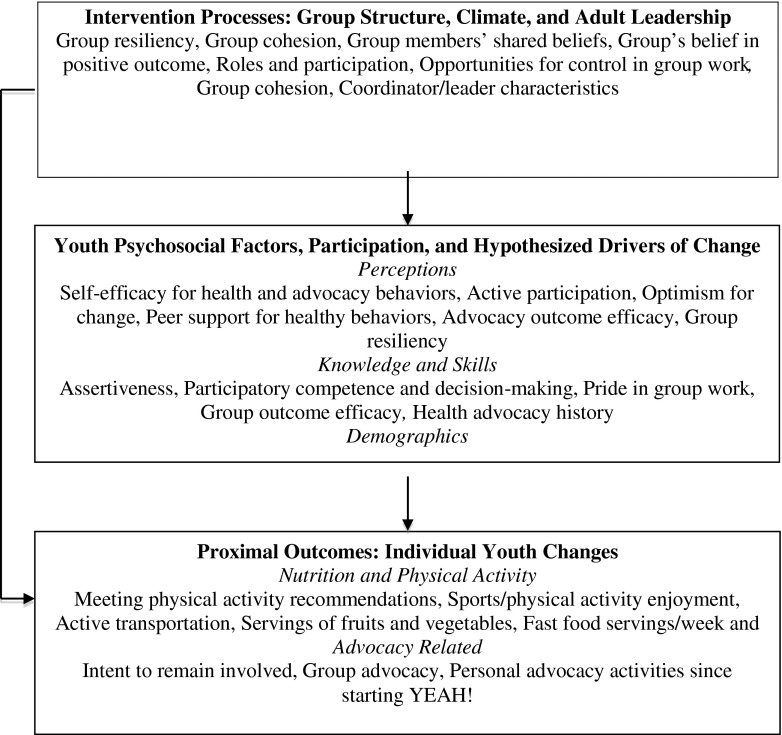

From the larger evaluation study model, we developed and measured youth advocacy-related subscales [5]. Based on that model, Fig. 2 presents a schematic conceptualization of the subscales assessed in the present study: intervention processes (e.g., group-level and adult leadership factors), youth-level factors and hypothesized drivers (e.g., youth perceptions, skills, attitudes), and proximal outcomes (e.g., youth’s advocacy, diet, physical activity behaviors). Given the diversity of obesity-related change targets and the potential of youth advocacy to address these varied environmental and policy factors, a next step is to evaluate youth advocacy training programs. Evaluation should include not only process measures such as context, reach, dose delivered, dose received, fidelity, implementation, and recruitment [24], but measures of change at the individual, social, built environment, and policy levels. Conducting process and outcome evaluations of youth advocacy for obesity prevention can generate evidence to refine training program practices and identify the most effective advocacy behaviors.

Fig 2.

The parallel constructs and subscales from the larger evaluation study, as examined in the present study. Some subscales were measured at posttest only

The present study is a noncontrolled initial evaluation of multiple outcomes of the Youth Engagement and Action for Health! (YEAH!) youth obesity prevention advocacy program, as well as correlates of the proximal outcome of advocacy readiness, based on a conceptual model [3, 4] and using previously evaluated measures [5]. The first goal was to assess youth changes, before and after completing advocacy projects, on measures of hypothesized psychosocial influences, intervention processes, and proximal outcomes of advocacy. The second goal was to create an index for youth advocacy readiness to serve as an inclusive and meaningful outcome. No validated youth obesity prevention advocacy evaluation tools designed specifically for youth existed before the present study, so our group developed surveys based on a conceptual model and relevant published measures when available [4, 5]. To further explore the relationships among these constructs, we aimed to create an index for youth advocacy readiness consisting of multiple subscales and subsequently evaluate the role of group, youth, and leadership factors in explaining youth advocacy readiness following participation in YEAH!

METHOD

Procedures

Background, training, and recruitment

Youth Engagement and Action for Health (YEAH!) was a training program of the San Diego County Childhood Obesity Initiative (SDCCOI). It was designed to engage youth and adult group leaders in community advocacy for school and neighborhood improvement projects that could impact nutrition and physical activity environments (http://ourcommunityourkids.org/domains--committees/community/youth-engagement--action-for-health.aspx). Table 1 summarizes key intervention components; see [3] for a detailed description of the YEAH! training and advocacy procedures. Briefly, the SDCCOI held biannual half-day YEAH! adult group leader advocacy trainings. Leaders of youth groups that were ongoing or forming (e.g., after school programs, community groups, religious groups) were recruited into the evaluation study.

Table 1.

Key components of the YEAH! training and intervention

| Introduction and background: Components of built environment that influence behaviors, the need for neighborhood environment changes |

| Obesity basics: Training youth and adults on healthy eating and physical activity behaviors |

| Gathering practical group resources: Identifying a project coordinator and community partners |

| Youth participation strategies: Logistics of working with youth, teamwork, conflict resolution |

| Choosing and conducting environmental audits: Schools, parks, fast food outlets, outdoor advertising, stores |

| Defining problems, selecting an advocacy target and recommended solutions, preparing presentations |

| Selecting decision maker(s) to advocate with, creating realistic suggested action plan(s) |

| Advocating for environment or policy changes with decision makers, playing the “policy game” |

During these trainings, adult leaders were introduced to the YEAH! manual, which included instructions on implementing community audits of modifiable environment factors, choosing a meaningful project, using community assessment tools, developing an advocacy action plan, and advocating for changes. The YEAH! manual provided recommendations for regular weekly meetings (2–4 h/week) including training, assessment, and advocacy periods extending over 4 to 6 months. Basic youth nutrition and physical activity recommendations were also included in the YEAH! manual. The groups met for an average of nine sessions over 10 weeks [3].

Advocacy projects

Advocacy projects were centered on one or more of five written, photographed, or videotaped (photovoice) environmental audits that the youth groups conducted in their local areas. Audits were completed around schools, parks, fast food outlets, stores, or outdoor food advertising; see [3, 5] for process details. Once groups finished the assessments, they worked together to compile their findings into an advocacy presentation. The group selected a relevant decision maker(s) (e.g., school board member, city council member) for whom to target their presentation. Advocacy presentations included the youth’s photovoice documentation of the relevant problems, suggested solutions, and a proposed timeline for changes to occur.

Youth inclusion criteria were as follows: boys and girls between 10 and 18 years old involved with nutrition or physical activity-related youth advocacy groups and their adult group leaders in San Diego County. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The youth, leader, and a parent must have provided informed consent (adult leader and parent) or assent (youth). This research project and all procedures were approved by our University’s IRB.

Measures

Given the dearth of appropriate measures in the literature, our group developed surveys based on a conceptual model and relevant published measures when available [5] (see Fig. 1). Some measures were adapted from tobacco control measures in the Statewide Youth Movement Against Tobacco Use (SYMATU) [17, 25, 26]. When relevant, we used or adapted items from SYMATU that assessed youth factors, process variables, and proximal outcomes. These included perceptions (e.g., self-efficacy, perceived socio-political control), knowledge/skills (e.g., assertiveness, advocacy experience, decision-making skills, participatory competence, perceived advocacy barriers), collective participation (e.g., reason for joining, level of involvement with other organizations), and group characteristics (e.g., outcome efficacy, group resiliency).

Nutrition and physical activity behaviors were addressed in the YEAH! manual. Given the program’s overarching goal of obesity prevention, and to assess whether advocacy-related constructs were associated with nutrition and physical activity, these outcomes were included in the present study. We added self-reports of physical activity [27] and fruit/vegetable, fast food, and beverage consumption [28] using previously validated measures. Additional validated measures important to obesity were included, such as availability of fast food within a 10-min walk from home or school, food store access, school vending machine access, school lunch options, and outdoor food/beverage advertising [29–34].

Youth baseline and follow-up survey data were used in the present analyses. The baseline youth survey inquired about participants’ current attitudes toward advocacy, current advocacy behaviors, psychosocial variables related to advocacy outcomes, and physical activity and nutrition behaviors. The youth follow-up survey was given to those who completed the baseline survey, at the conclusion of their advocacy projects. It inquired about the same constructs, plus perceptions of group dynamics, their leader’s style, ratings for their level of group participation, and follow-up about what they learned or gained from their project. Data collection was completed in March 2013.

Data analyses

All analyses were conducted in SPSS version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and MPlus version 6.1 (Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA). Analyses were conducted on youth with complete pre- and post-advocacy data (n = 92 matched pairs).

First, we assessed youth changes before and after completing advocacy projects on the measures of advocacy behaviors and processes, potential correlates and drivers, and proximal outcomes of nutrition and physical activity behaviors. Paired t tests were conducted to assess youth individual-level changes by determining significant mean subscale score changes over an average of 10 weeks.

Next, we created an advocacy readiness index to evaluate the role of group, youth, and leadership factors on youth advocacy readiness following participation in YEAH! projects. Standardized residualized change values were computed by linear regression for each of the six subscales with significant pre-post changes. Standardized residualized change scores were summed for those six subscales to create the youth advocacy readiness index.

Bivariate correlations were run between the advocacy readiness index score (outcome) and each of the hypothesized independent variables (the remaining perception, knowledge-based, and behavioral subscales). Variables with significant correlations (p < .10 to be inclusive given the small sample size) were included in the full generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) regression.

GLMM was used to analyze the demographic factors and significantly correlated covariates’ associations with youth changes on the advocacy readiness index. The group identifier was entered as the random effect variable to account for clustering of youth within groups. The youth demographics were forced to enter as covariates were age, gender, race/ethnicity, and relative self-rated school performance.

The independent variables in the GLMM were the subscales selected based on significant correlations with the index outcome. Though significantly correlated, the group advocacy (participation) variable was left out of the GLMM regressions to maximize sample size and variability because not all youth participated in advocacy. Unstandardized regression coefficients (Bs) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were reported to represent the change in the youth advocacy readiness outcome for every one unit change in continuous IVs or the reference level of the dichotomous IVs.

RESULTS

Youth baseline demographic and advocacy group characteristics have been reported previously [3] and are presented in Table 2. Briefly, the youth came from 21 groups, ranged in age from 9–22, and over two-thirds were female. Most youth were non-White, with the largest single minority group being Hispanic/Latino (35.6 %). Most of the youth groups focused on schools as their advocacy target (67.0 %). Twenty groups completed the follow-up questionnaires. Of those, all 20 groups presented their advocacy findings to a decision maker (e.g., school committee member, school principal, city council member).

Table 2.

Youth baseline demographic characteristics (n = 136)

| Characteristic | Number (%) or mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (range 9–22), mean (SD) | 15.3 (2.73) |

| Grade, mean (SD) | 10.2 (2.54) |

| Gender (n = 134), % | |

| Male | 36 (26.9) |

| Female | 98 (73.1) |

| Race/ethnicity, %a | |

| White non-Hispanic | 19 (13.0) |

| Black non-Hispanic | 34 (23.3) |

| Hispanic/Latino(a) | 52 (35.6) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian | 32 (21.9) |

| Other | 22 (15) |

| How well do you think you do in school? (range 1–5), mean (SD) | 2.13 (.78) |

| Type of YEAH! project/group focus, %a | |

| School | 69 (67.0) |

| Parks | 11 (10.7) |

| Fast food outlets | 4 (3.9) |

| Outdoor advertising | 12 (11.6) |

| Stores | 4 (3.9) |

| Never done any advocacy prior to this group, % | 38 (27.9) |

| Number of days per week physically active, mean (SD) | 3.7 (2.2) |

| Times per week eat fast food, mean (SD) | 1.6 (1.7) |

SD standard deviation

aRespondents could choose more than 1 category, so percentages do not add to 100

Youth subscale score changes before and after advocacy

All data presented are derived from the YEAH! evaluation study’s youth pre-advocacy and post-advocacy surveys developed for the present study. Table 3 presents the youth subscale descriptive statistics and paired t tests results.

Table 3.

Youth subscale descriptive statistics for matched pairs (n = 92)

| Subscale | No. of items | Pre-test | Posttest | t test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | Mean (SD) | Range | |||

| Youth psychosocial factors, participation, and hypothesized drivers of change | ||||||

| Perceptions | ||||||

| Self-efficacy for health and advocacy behaviors | 3 | 3.84 (.85) | 1.33–5 | 4.16 (.72) | 2.33–5 | t = 4.22*** |

| Perceived sociopolitical control (two subscales) | ||||||

| Active participation in advocacy | 2 | 2.60 (.92) | 1–5 | 2.89 (.91) | 1–5 | t = 2.93** |

| Optimism for change | 2 | 4.04 (.73) | 1–5 | 4.11 (.74) | 2–5 | t = .91 |

| Openness to healthy behaviors | 2 | 2.60 (1.15) | 0–5 | 2.76 (1.19) | 0–5 | t = 1.12 |

| Advocacy outcome efficacy | 2 | 4.45 (.56) | 2.5–5 | 4.34 (.61) | 2.67–5 | t = 1.72 † |

| Group resiliency | 1 | 4.56 (.70) | 2–5 | 4.58 (.72) | 1–5 | t = .11 |

| Knowledge and skills | ||||||

| Assertiveness | 3 | 3.74 (.95) | 1–5 | 4.00 (.70) | 2.0–5 | t = 3.23** |

| Health advocacy history | 2 | 1.81 (.99) | 0–4 | 2.16 (.90) | 0–4 | t = 3.52*** |

| Participatory competence and decision making | 2 | 3.94 (.67) | 2–5 | 4.03 (.64) | 2.5–5 | t = 1.11 |

| Knowledge of resources | 1 | 3.56 (1.15) | 1–5 | 3.93 (.96) | 1–5 | t = 3.24** |

| Social support for health behaviors | 1 | 3.44 (.82) | 1–5 | 3.92 (.96) | 1–5 | t = 3.84*** |

| Proximal outcomes | ||||||

| Nutrition and physical activity behaviors | ||||||

| Meeting physical activity recommendations | 2 | 3.62 (1.87) | 0–7 | 4.0 (1.57) | 0–7 | t = 2.28* |

| Sports and active transportation (split into two subscales) | ||||||

| Sports/Enjoyment of physical activity | 2 | 3.02 (1.19) | .5–5 | 3.17 (1.12) | 1–5 | t = 1.58 |

| Active transport | 2 | .81 (1.63) | 0–5 | .78 (1.61) | 0–5 | t = .10 |

| Servings of fruits and vegetables | 2 | 2.11 (1.01 | 0–4 | 2.18 (.97) | .5–4 | t = 1.16 |

| Fast food times per week | 1 | 1.40 (1.57) | 0–7 | 1.68 (2.58) | 0–15 | t = 1.64 |

| Fast food times per month | 1 | 5.38 (6.16) | 0–30 | 2.38 (7.26) | 0–60 | t = .11 |

| Advocacy behaviors (pre-post checklist) | ||||||

| Level/history of advocacy actions (sum of responses) | 8 | 1.09 (1.08) | 0–4 | 2.10 (1.75) | 0–8 | t = 3.97*** |

Pre-post advocacy changes were measured by paired t tests; t values are reported as absolute values

† p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Youth psychosocial factors, participation, and hypothesized drivers of change

Perceptions subscales

Two of the six perceptions subscales increased significantly following advocacy training (Table 3). The mean self-efficacy for health behaviors subscale score increased 8.3 % from baseline (p < .001). One of the perceived sociopolitical control subscales increased significantly: The active group participation mean score increased 11.1 % (p < .01).

Knowledge and skills subscales

Four of the five knowledge and skills subscale scores increased significantly following advocacy training (Table 3). The assertiveness subscale mean score increased 6.9 % from baseline to follow-up (p < .01). The health advocacy history subscale mean score increased 19.3 % (p < .001). The knowledge of resources mean score increased 10.4 % (p < .01). The social support for health behaviors subscale mean score increased 13.9 % (p < .001). Though not originally included in the hypotheses, the advocacy actions score increased by 85.0 % (p < .001) following participation.

Youth proximal outcomes

Nutrition and physical activity subscales

The nutrition and physical activity behavior subscales were not hypothesized to change significantly after advocacy training, because behavior change was not the goal, so these behaviors were considered secondary analyses. One of the six subscales improved significantly. Meeting physical activity recommendations increased from 3.62 (1.87) to 4.0 days/week (1.57), a 10.5 % increase from baseline (p < .05).

Youth follow-up only subscales

Several of the subscales were assessed only at the follow-up time point and can be considered as process evaluation (see Table 4). Included among these subscales were the youths’ perceptions and feelings about their participation, group processes, and group characteristics. Most of the follow-up only subscales displayed high levels of agreement: Youth felt strongly and positively about their experiences. For instance, most of the subscales were rated on 1 (low agreement) to 5 (high agreement) Likert scales, and almost all of the scores were above 4.0, indicating positive reflection on their groups, leaders, and their own participation.

Table 4.

Pearson’s correlations between the youth advocacy readiness index outcome and youth subscale variables (n = 80–83)

| Variable | r |

|---|---|

| Optimism for change (baseline) | .339** |

| Optimism for change (follow-up) | .506** |

| Openness to healthy behaviors (baseline) | −.133 |

| Openness to healthy behaviors (follow-up) | .093 |

| Advocacy outcome efficacy (baseline) | .019 |

| Advocacy outcome efficacy (follow-up) | .295** |

| Group resiliency (baseline) | .227* |

| Group resiliency (follow-up) | .258* |

| Participatory competence and decision making (baseline) | .146 |

| Participatory competence and decision making (follow-up) | .261* |

| Meeting physical activity recommendations (baseline) | .067 |

| Meeting physical activity recommendations (follow-up) | .083 |

| Sports/physical activity enjoyment (baseline) | .203† |

| Sports/physical activity enjoyment (follow-up) | .335** |

| Active transport (baseline) | −.027 |

| Active transport (follow-up) | −.050 |

| Servings of fruits and vegetables (baseline) | .124 |

| Servings of fruits and vegetables (follow-up) | .259** |

| Fast food times per week (baseline) | −.080 |

| Fast food times per week (follow-up) | −.043 |

| Fast food times per month (baseline) | −.068 |

| Fast food times per month (follow-up) | .109 |

| Level/history of advocacy actions (baseline) | .071 |

| Level/history of advocacy actions (follow-up) | −.004 |

| Posttest only subscales | |

| Pride in group work | .161 |

| Roles and participation: checklist | −.031 |

| Roles and participation: Likert | .538** |

| Benefits from participating | −.131 |

| Intent to remain involved | .394** |

| Opportunities for control | .332** |

| Opportunities for involvement | .196† |

| Collective efficacy | .230* |

| Group outcome efficacy | .279* |

| Group cohesion | .208† |

| Group advocacy (only if group met with a decision maker) | .391** |

| Follow-up group resiliency | .212† |

| Coordinator characteristics | .325** |

| Personal advocacy activities since starting YEAH! | .554** |

† p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Correlates of youth readiness for advocacy

Creating the advocacy readiness outcome index and selecting independent variables for the regression

The six subscales with significant pre-post advocacy changes were used to create the youth advocacy readiness outcome index: self-efficacy for health and advocacy behaviors, active participation, assertiveness, health advocacy history, knowledge of resources, and social support for health behaviors. The youth advocacy readiness index had a normal distribution (n = 83, mean .054, SD 3.13, range −8.83–6.05). Twenty of the 38 youth subscale variables were significantly correlated with the youth advocacy readiness outcome at p < .10. Table 4 displays the correlation results.

Full GLMM regression model

The mixed regression model results (Table 5) indicated that four of the youth subscales were significantly positively associated with the advocacy readiness outcome: optimism for change at follow-up (B = 1.46, 95 % CI = .49, 2.44), sports and physical activity enjoyment (B = .55, 95 % CI = .05, 1.05), roles and participation (B = 1.81, 95 % CI = .60, 3.02), and personal advocacy activities since starting YEAH! (B = 1.49, 95 % CI = .64, 2.32).

Table 5.

GLMM relations between youth demographic factors, psychosocial subscales, and group characteristics to youth advocacy readiness (n = 80)

| Variable | B | 95 % CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic covariates | |||

| Age | −.19 | −.44, .05 | .123 |

| Male (gender) | .73 | −.48, 1.95 | .235 |

| Hispanic or African American (race/ethnicity) | 1.07† | −.14, 2.29 | .082 |

| School performance | .17 | −.65, .99 | .684 |

| Independent variable subscales | |||

| Optimism for change (follow-up) | 1.46** | .49, 2.44 | .004 |

| Advocacy outcome efficacy (follow-up) | −1.65 | −4.13, .83 | .188 |

| Group resiliency (follow-up) | −.67 | −1.91, .57 | .282 |

| Participatory competence and decision making (follow-up) | .64 | −.34, 1.62 | .198 |

| Sports/physical activity enjoyment (follow-up) | .55* | .05, 1.05 | .033 |

| Servings of fruits and vegetables (follow-up) | .25 | −.36, .86 | .408 |

| Roles and participation (Likert) | 1.81** | .60, 3.02 | .004 |

| Intent to remain involved | −.42 | −1.45, .60 | .410 |

| Opportunities for control | −.50 | −1.54, .54 | .338 |

| Opportunities for involvement | .15 | −.53, .83 | .654 |

| Collective efficacy | .57 | −.68, 1.81 | .366 |

| Group outcome efficacy | .56 | −1.32, 2.44 | .556 |

| Group cohesion | .72† | .00, 1.43 | .050 |

| Follow-up group resiliency | −.45 | −1.37, .47 | .332 |

| Coordinator characteristics | −.38 | −1.40, .63 | .450 |

| Personal advocacy activities since starting YEAH! | 1.49** | .64, 2.32 | .001 |

† p < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01

DISCUSSION

The present study represents the first evaluation of a youth advocacy training for obesity prevention. There were apparent improvements on youth-reported confidence in advocacy, knowledge of resources, advocacy behaviors, and physical activity after participating in advocacy training and presentations to decision makers, suggesting numerous benefits for the participants in YEAH!. The outcome findings provided initial support for the childhood obesity advocacy model [3, 4] and suggested that advocacy training can provide youth development benefits in addition to any impacts related to childhood obesity. Further, a youth advocacy readiness index score was created that can be used as an outcome in other youth advocacy studies. The youth and group-level factors associated with the advocacy readiness index can be targeted more intensively in future advocacy interventions to enhance the training’s effects on youth. There is much policy and practice interest in the potential for citizen advocacy as a strategy for childhood obesity prevention, and the present results provide an indication that this strategy should be further developed and evaluated.

Pre-post changes among youth

Youth-reported changes following advocacy participation generally showed a pattern of increasing confidence and individual and social benefits. Among the hypothesized youth drivers of change, self-efficacy for health and advocacy behaviors, and active participation increased significantly, which can be considered among the most important scales. The self-efficacy improvement is particularly notable because of its central role in Social Cognitive Theory [11] and good evidence of its relation to behavioral outcomes. Based on Social Cognitive Theory and a youth advocacy model [3, 4], high or increasing self-efficacy for advocacy behaviors was expected to lead to youth health and advocacy behavior change. Self- and collective-efficacy (i.e., several of the high scoring subscales on the follow-up survey), coupled with increased engagement (i.e., active participation) and understanding of the environment, were thought to be primary drivers of advocacy behaviors. These pre-post changes suggest that the YEAH! intervention had several of the intended effects on participating youth.

Those subscales that did not change following YEAH! participation (optimism for group change, openness to healthy behaviors, outcome efficacy, group resiliency) may have been driven by groups that were not as successful with the advocacy process or outcomes. Based on the content of the scales, these constructs appear to be more dependent on group, rather than individual processes. Further, the optimism for change scale had a high initial mean (4.0 out of 5.0), so it would have been difficult to improve. The outcome efficacy subscale mean decreased marginally, which may indicate that the youth were more realistic about what their advocacy could achieve after experiencing the process.

Of the remaining hypothesized youth drivers, the assertiveness, health advocacy history, knowledge of resources, and social support for health behaviors subscales improved significantly. These increases indicate that the youth were participating, paying attention, and learning. The positive changes in social support for health behaviors can be considered a co-benefit of participation in YEAH! that may encourage personal behavior change. The level/history of advocacy actions scale increase can be explained by the youth reporting their advocacy behaviors that resulted from YEAH!

The nutrition and physical activity behavior proximal outcomes were included to see if there were positive youth co-benefits of participating in advocacy training. Days of meeting physical activity recommendations increased modestly, from 3.6 at baseline to 4 days per week at follow-up. This finding would need to be replicated in a larger sample and controlled design before drawing conclusions that YEAH! or youth advocacy consistently improves physical activity participation.

The tobacco control youth advocacy literature can help contextualize the present youth perceptions, knowledge, and skills changes. Two studies [9, 35] found that perceived self-efficacy significantly increased among youth following tobacco control advocacy activities. Youth outcome expectancy, leadership competence, and perceived policy control findings did not change significantly, similar to the present study’s findings [35]. However, in a follow-up tobacco study, outcome expectancy did significantly increase, following successful advocacy activities [9]. The latter study found that leadership competence significantly increased for boys but not girls. The present study did not directly assess leadership confidence, but the concept is related to several youth driver subscales in the present study (i.e., optimism for change, assertiveness, participatory competence, and decision making), and assertiveness significantly increased in the present study.

Correlates of change in youth advocacy readiness

The advocacy readiness outcome index represents the intended composite outcome of YEAH!: preparing youth to be confident advocates for obesity prevention. Four of the 20 potential correlates were significantly related to the advocacy readiness index: optimism for change, roles and participation, personal advocacy activities since starting YEAH!, and sports/physical activity enjoyment. Most of these were posttest only variables, suggesting that experiences specific to the YEAH! project were related to adolescents’ perceived readiness to be advocates.

Optimism for change was expected to be positively associated with advocacy readiness. It was an independent correlate of the outcome, remaining significant after controlling for the demographics and other independent variables. The present findings of optimism’s association with youth advocacy readiness appear to align with those of the previous research [26]. Optimism appears to be a strong component of youth’s perception of their advocacy experiences, perceived success, and empowerment [26]. The roles and participation subscale was also positively associated with the outcome index, which generally replicates the findings in tobacco control. This subscale was also adapted from the SYMATU studies, in which quantity and quality of participation were hypothesized to be a primary driver of their outcome, youth empowerment [18, 26]. Advocacy, assertiveness, self-efficacy, and perceived sociopolitical control were four of the six components of the youth advocacy readiness outcome. It is important that the roles and participation subscale were found to be associated with the outcome, providing encouraging evidence that the present analyses agree with tobacco advocacy results.

Another significantly associated subscale was personal advocacy activities since starting YEAH!, a follow-up survey subscale assessing youth’s attempts at advocating with their families or friends to make healthier schools or communities. Perhaps becoming an advocate within their social circles was a step toward preparing them to be confident advocates to decision makers, or a product of having practiced advocacy in the group setting. Sports and physical activity enjoyment at posttest was also significantly associated with the advocacy outcome. This was a surprising finding that may indicate that youth who were more active either tended to join these types of groups or got more out of the groups.

It was unexpected that the youth demographics were not significantly associated with the advocacy outcome. One previous tobacco advocacy study found that gender was associated with advocacy outcomes and that Black and Hispanic youth trended toward having higher advocacy readiness [35]. A high school-based youth empowerment for heart health study found that being Black (vs. White) was significantly associated with community participation [36]. This is an encouraging trend that youth who come from underrepresented groups or neighborhoods with greater health disparities may respond particularly well to advocacy or empowerment training.

Strengths and limitations

The present study used theory-based and evaluated survey measures that represented a range of potential proximal outcomes of youth advocacy for obesity prevention. The improvements on six of the youth pre-post subscales suggest positive changes among the participants in YEAH!, justifying further study of youth advocacy interventions. The youth advocacy readiness index is an innovative way to capture the constructs of interest. However, it may not be easily interpretable, so other outcome measures for advocacy and empowerment training should be developed and examined. Further, there is a possibility of ceiling effects on this outcome, and it should be further evaluated in different populations. Though there was a relatively wide range of youth ages, the majority of youth came from middle and high schools (95 % were ages 11–18), so we do not believe that age was a confounding factor in these analyses. Our sample was predominantly female, which could have attenuated the effects of gender on the outcome. Current results must be considered preliminary and interpreted with caution given the uncontrolled design and small sample size. The low average cluster size may have led to false negatives in the full model, as power to detect youth effects between groups was low. Youth and groups dropped out of the study for various reasons, as previously presented [3]. This is a common problem with advocacy studies in communities, suggesting a need to build in large enough recruitment targets or better engagement strategies.

Future research directions

Youth advocacy for obesity prevention is a promising avenue for future action and research. Training and supporting youth to advocate has the potential to contribute to changes in physical activity and nutrition environments and policies that can sustainably impact youth overweight and obesity [4]. It can be difficult to quantify objectives, so clear goals are a key determinant for such research [24]. Advocacy will likely best be used as one of many tools in preventing obesity. Present indications of positive effects of advocacy experiences on youth participants provide a rationale for further and more rigorous evaluations with larger samples of groups and youth. Including a control group with youth in non-advocacy clubs or activities would be useful for more rigorously assessing the impacts of YEAH! or other advocacy programs.

Implications for policy and practice

There is much interest in the potential for youth advocacy to contribute to policy and environment changes to support obesity prevention. Perhaps the most important implication of the present study is that youth advocacy for environment and policy change is a promising approach for obesity prevention. It would be useful to evaluate youth advocacy training integrated into settings where many youth could be engaged, such as schools, after school programs, YMCAs, and faith-based organizations, so effective programs could be institutionalized in these settings. Sustainability will be key to societal impact.

A research implication is that the measures developed for the present evaluation [5] were found to be sensitive to expected changes among participants in the YEAH! advocacy program. Thus, these measures can be recommended for use in future studies. Using a common set of measures in forthcoming advocacy studies will allow this field of research to move forward efficiently because results can be more easily compared across studies. Youth advocacy can be a mechanism for promoting more widespread implementation of evidence-based environment and policy changes that can facilitate improved eating and physical activity behaviors [37]. Youth advocacy should be considered one part of the multilevel, multisetting interventions that are recommended for youth obesity prevention [1].

Acknowledgments

Evaluation was performed at San Diego State University. Program funding for YEAH! is provided by The California Endowment and Kaiser Permanente.

Compliance with ethical standards

Funding

This paper was supported by a grant (# 68508) from the Active Living Research program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

Authors Millstein, Woodruff, Linton, and Edwards declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Author Sallis has received grants from the National Institutes of Health, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Active Living Research), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Nike Inc., and the California Endowment. He is also a part owner of Santech, Inc., and has a consulting relationship with the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, on an NIH grant.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Youth advocacy training for obesity-related environment and policy change has preliminary evidence of effectiveness and should be further developed for use in practice.

Policy: Youth advocacy is a promising strategy for engaging more people in the policy change process for improving health environments.

Research: The present evaluation documents positive short-term outcomes of youth advocacy training on youth participants, justifying more rigorous and longer-term evaluations.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine . Preventing childhood obesity: health in the balance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine . Accelerating progress in obesity prevention: solving the weight of the nation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linton LS, Edwards CC, Woodruff SI, et al. Youth advocacy as a tool for environmental and policy changes that support physical activity and nutrition: an evaluation study in San Diego County. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E46. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millstein RA, Sallis JF. Youth advocacy for obesity prevention: the next wave of social change for health. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:497–505. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0060-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millstein, RA, Woodruff SI, Linton LS, Edwards CC, Sallis JF. Development of measures to evaluate youth advocacy for obesity prevention. Revised manuscript under review: Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Carlisle S. Health promotion, advocacy and health inequalities: a conceptual framework. Health Promot Int. 2000;15:369–376. doi: 10.1093/heapro/15.4.369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin J. The role of advocacy. Preventing childhood obesity: evidence policy and practice. 2010; 192–199.

- 8.World Health Organization . Advocacy strategies for health and development: development communication in action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winkleby MA, Feighery E, Dunn M, et al. Effects of an advocacy intervention to reduce smoking among teenagers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:269–275. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dzewaltowski DA, Karteroliotis K, Welk G, et al. Measurement of self-efficacy and proxy efficacy for middle school youth physical activity. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2007;29:310–332. doi: 10.1123/jsep.29.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmerman MA. Psychological empowerment: issues and illustrations. Am J Community Psychol. 1995;23:581–599. doi: 10.1007/BF02506983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmerman MA, Rappaport J. Citizen participation, perceived control, and psychological empowerment. Am J Community Psychol. 1988;16:725–750. doi: 10.1007/BF00930023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryan GJ, Dzewaltowski DA. Comparing the relationships between different types of self-efficacy and physical activity in youth. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29:491–504. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Toward A. Comprehensive Model of Change. Springer; 1986.

- 17.Evans WD, Ulasevich A, Blahut S. Adult and group influences on participation in youth empowerment programs. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:564–576. doi: 10.1177/1090198104268546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holden DJ, Messeri P, Evans WD, et al. Conceptualizing youth empowerment within tobacco control. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:548–563. doi: 10.1177/1090198104268545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davison KK, Lawson CT. Do attributes in the physical environment influence children’s physical activity? A review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:19. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding D, Sallis JF, Kerr J, et al. Neighborhood environment and physical activity among youth: a review. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:442–455. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaczynski AT, Henderson KA. Environmental correlates of physical activity: a review of evidence about parks and recreation. Leis Sci. 2007;29:315–354. doi: 10.1080/01490400701394865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kain J, Gao Y, Doak C, et al. Obesity prevention in primary school settings: evidence from intervention studies. Preventing childhood obesity: evidence, policy, and practice. Oxford: BMJ Books, Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prosser L, Visscher TLS, Doak C, et al. Obesity prevention in secondary schools. Preventing Childhood Obesity. Evidence, Policy and Practice. Oxford: BMJ Books, Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steckler AB, Linnan L, Israel B. Process Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holden DJ, Evans WD, Hinnant LW, et al. Modeling psychological empowerment among youth involved in local tobacco control efforts. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32:264–278. doi: 10.1177/1090198104272336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holden DJ, Crankshaw E, Nimsch C, et al. Quantifying the impact of participation in local tobacco control groups on the psychological empowerment of involved youth. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:615–628. doi: 10.1177/1090198104268678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prochaska JJ, Sallis JF, Long B. A physical activity screening measure for use with adolescents in primary care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:554–559. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prochaska JJ, Sallis JF. Reliability and validity of a fruit and vegetable screening measure for adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34:163–165. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKenzie TL, Marshall SJ, Sallis JF, et al. Student activity levels, lesson context, and teacher behavior during middle school physical education. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000;71:249–259. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2000.10608905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKenzie TL, Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, et al. Evaluation of a two-year middle-school physical education intervention: M-SPAN. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1382–1388. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000135792.20358.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patrick K, Calfas KJ, Norman GJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a primary care and home-based intervention for physical activity and nutrition behaviors: PACE+ for adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:128–136. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patrick K, Norman GJ, Calfas KJ, et al. Diet, physical activity, and sedentary behaviors as risk factors for overweight in adolescence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:385–390. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grow H, Saelens B, Kerr J, et al. Where are youth active? Roles of proximity, active transport, and built environment. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:2071–2079. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181817baa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forman H, Kerr J, Norman GJ, et al. Reliability and validity of destination-specific barriers to walking and cycling for youth. Prev Med. 2008;46:311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winkleby MA, Feighery EC, Altman DA, et al. Engaging ethnically diverse teens in a substance use prevention advocacy program. Am J Health Promot. 2001;15:433–436. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-15.6.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altman DG, Feighery E, Robinson TN, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with youth involvement in community activities promoting heart health. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25:489–500. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sallis JF, Glanz K. Physical activity and food environments: solutions to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Q. 2009;87:123–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]