Abstract

Objective(s):

Sugar cane molasses is a commonly used ingredient in several food products. Contrasting reports suggest that molasses may have potential adverse or beneficial effects on human health. However, little evidence exists that examines the effects of molasses on the different physiological systems. This study investigated the effects of sugar cane molasses on various physiological systems using in vivo and in vitro methods.

Materials and Methods:

Molasses was administered orally to BALB/c, male mice and animals were randomly assigned into either a treatment or control group. General physiological changes, body weight and molasses intake of animals were monitored. At the end of the exposure period, collected blood samples were evaluated for potential toxicity using plasma biomarkers and liver enzyme activity. Immunised treated and untreated mice were evaluated for antibody titre to determine the effect of molasses on the immune response. To investigate the impact of molasses on testicular steroidogenesis, testes from both treated and control groups were harvested, cultured and assayed for testosterone synthesis.

Results:

Findings suggest that fluid intake by molasses-treated animals was significantly increased and these animals showed symptoms of loose faeces. Molasses had no significant effect on body weight, serum biomarkers or liver enzyme activity (P>0.05). Immunoglobulin-gamma anti-antigen levels were significantly suppressed in molasses-treated groups (P=0.004). Animals subjected to molasses exposure also exhibited elevated levels of testosterone synthesis (P=0.001).

Conclusion:

Findings suggests that molasses adversely affects the humoral immune response. The results also promote the use of molasses as a supplement to increase testosterone levels.

Keywords: Humoral immunity, Immunosuppression, Liver enzymes, Male reproductive - system, Molasses

Introduction

Sugar cane molasses, also referred to as the final effluent of sugar refinement is a dense, darkly coloured substance teeming in minerals (1, 2). Molasses comprises mostly of sugars (approximately 46% w/w), non-sugar organic materials (e.g. phenolic compounds which are substances derived from the sugar cane plant) as well as other compounds synthesised during the manufacturing process (e.g. melanoidins, which are products of Maillard reactions) (3).

Traditionally, molasses has been used as an alternate sweetener to sugar and included as a common ingredient in various food products (4, 2). Worldwide, molasses is primarily used as feed for livestock as it enhances microbial growth in the rumen of animals that promotes the digestion of fibre and non-protein nitrogen (2). In addition, molasses has been widely advertised for its therapeutic properties believed to be a result of its rich mineral content (1). However, little or no scientific evidence exists to corroborate the suggest-ed health benefits of this substance (5).

The immune system plays an essential part of protecting healthy tissue against infectious patho-gens and disease (6). The immune system is a common target of endocrine modulators and research has shown that exposure to certain compounds (synthetic and natural compounds) may alter the immune response leading to various forms of toxicity (7, 8). Nagai and Koge have reported physiological actions of different sugar cane extracts (9, 10). Their results suggest that sugar cane extracts increase the defence against bacterial and viral infections, enhance immune reactions and possess hepatoprotective and antioxidant properties (5). Guimarães and colleagues (3) state that sugar cane components that display the above-mentioned characteristics are often contained in the resultant by-product, molasses. As a result, the biological activity of molasses should be investigated further.

In contrast to the proposed health benefits of molasses, research has shown that molasses has the potential to induce harmful effects in livestock (11). The supplementation of molasses in the diet of livestock has been reported to cause diseases such as molasses toxicity, urea toxicity and bloat (12). Masgoret and colleagues13 also reported the ability of molasses to induce endocrine disruptive effects in vitro. However, in a follow-up, in vivo study these effects could not be replicated in Holstein bull calves (13). Nevertheless, these reports suggest that molasses may be a potential risk factor in the development of animal and human disease and should therefore be screened for potential toxicity.

The reproductive and the liver organ systems are susceptible to endocrine modulators. The impact of certain toxicants on these physiological systems is detrimental and pathological effects have been observed in both humans and animals (14, 15). Food intake is the most common route of entry for various endocrine disruptors (16), emphasising the need for both manufacturers and consumers to be aware of possible adverse effects associated with commonly used food products. Currently, research investigating the physiological effects of sugar cane molasses is very limited and therefore further research is warranted.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of sample for dosing regimen

Range finding studies were initially conducted to determine the physiologically relevant dosage of sugar cane molasses that induced an effect in vitro (17, 18). Based on this data a dosage that ensures animal survival and that are without significant toxicity or distress to the animals was selected (19). For this study, commercially available molasses (Health Connections Wholefoods, South Africa) was used at a physiologically relevant concentration of 0.057 g molasses/ml of drinking water for all treated animals.

Experimental animals

All experimental procedures as well as the handling and care of animals were conducted in accordance with guidelines of the ethics committee at the University of the Western Cape. Pathogen-free, BALB/c, male mice weighing approximately 24-30 g were purchased from the University of Cape Town’s Animal Unit (Cape Town, South Africa). Animals were housed in plastic cages and kept in a well-ventilated room with a photoperiod of 12 hr and a temperature of 20 ± 2 °C. Standard mouse feed was always made readily available to all animals. For this study, animals were assigned into two treatment and two control groups comprising of six animals each. Animals were treated in vivo for the duration of two months. The treatment and control groups were classified as follows:

Treatment group 1 received 0.057 g molasses/ml of drinking water and was monitored for potential adverse effects on the male reproductive system.

Treatment group 2 received 0.057 g molasses/ml of drinking water and was immunised two weeks prior to the completion of the two-month feeding period (20). These animals were monitored for potential adverse effects on the immune system.

Control group 1 received normal drinking water and was monitored for potential adverse effects on the male reproductive system.

Control group 2 received normal drinking water and was immunised two weeks prior to the completion of the two-month feeding period (20). These animals were monitored for potential adverse effects on the immune system.

General observations

The molasses mixture was made accessible in calibrated drinking tubes similar to that described by Bachmanov et al (21). Consumption of molasses was monitored daily and body weights of animals were recorded every 10 days for the entire exposure period. General physiological changes were also monitored.

The effect of sugar cane molasses on the immune system

Two weeks prior to completion of the exposure period molasses treated and untreated mice were immunised according to the National Institute of Health protocol (1986-2010) (22). Xenopus plasma was used as an antigen due to its immunogenicity. The antigen for immunisation was prepared by mixing 50 μl Xenopus laevis plasma with 1450 μl of saline (0.9% NaCl). This was emulsified with an equal volume (1500 μl) of complete Freund’s adjuvant. Animals were immunised intraperitoneally (IP) with 200 μl of the emulsion. Blood samples (10 μl) for monitoring of the immune response were collected from the tail vein 2 weeks after immunisation. Blood samples were centrifuged at 1500 x g and the serum separated and stored at 4 °C until use. The serum was screened for antibody titre (Immunoglobulin-gamma (IgG)) using an optimised enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described in supplementary data.

ELISA to determine IgG titre

Flat bottom 96-well plates (Nunc, Serving Life Science, Denmark) were coated with 50 μl per/well of antigen diluted in 0.9% saline (1:1000) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. After this, non-specific binding sites were blocked with 1% BSA in saline (200 μl/well) for 1 hr at room temperature. At the end of this incubation period, the plate was washed four times with wash buffer (phosphate buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20). A doubling dilution of serum samples in 1% BSA in saline (ranging from 1:1000 to 1:64000) as well as a control sample (1% BSA in saline only) were added to respective wells at 50 μl per/well. The plate was sealed and incubated at room temperature for 2 hr. After four washings, 50 μl of rabbit-anti-mouse-IgG horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1:5000 in 0.1% BSA saline) was added to each well and incubated for 1 hr at room temperature. A final washing step of seven washes followed and 50 μl of warm substrate solution (Tetramethybenzidine solution) was added to all wells. The plate was incubated for 15 min at room temperature. The reaction was then stopped with the addition of 50 μl stop solution (1M H2SO4) and the absorbance read at 450 nm using a spectrophotometer (Original Multiskan EX, Type 355, Thermo Electron Corporation, China).

The effect of molasses on serum biomarkers

Blood collected by means of tail bleeds of mice were dispensed into heparinised capillary tubes (Lasec, SA). All samples were evaluated immediately for haematocrit using a micro-haematocrit reader (Hawskey, England). The plasma separated by centrifugation was collected and used to assess lactate dehydrogenase activity (LDH) and protein concentration. The protein concentration of all samples was determined according to the procedure described by Bradford (23). LDH activity in blood plasma was measured using a chromogenic cytotoxicity detection kit (Biovision, USA). Liver injury was also monitored by measuring the liver enzymes alkaline phosphatase (ALP), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in plasma samples. Commercially available diagnostic kits (BioQuant, CA) were used to measure the activity of the above-mentioned liver enzymes. Kits contained all components necessary for the assay and all procedures were performed using 96-well microtitre plates (Nunc, Serving Life Science, Denmark).

The effect of molasses on the male reproductive system

At the end of the two month exposure period, treated and untreated animals (treatment group 1 and control group 1) were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and their testes were dissected under aseptic conditions. Testicular cells were harvested, cultured and assayed as described by Rahiman and Pool (17). The testis of each mouse was finely minced and suspended in 2 ml of culture medium, which comprised of RPMI-1640 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) supplemented with 0.2% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 1% glutamax and 1% mixture of streptomycin, penicillin and fungizone (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Cell debris was removed and the supernatant containing cells was centrifuged at 1000 x g (Super mini centrifuge, MiniStar Plus, Hangzhou Allsheng Instruments, China) for 10 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in a final volume of 5 ml and incubated for 1 hr at 37 °C with 5% CO2. At the end of the incubation period, the cell suspension was centrifuged at 1000 x g for 10 min and the cell pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of fresh medium. Cells were incubated for a further 30 min at 37 °C with 5% CO2, after which cells were centrifuged as previously described and resuspended in 5 ml medium to give a final concentration of 1 x 106 cells/ml.

Cells (100 μl) were then dispensed into wells of a 96-well tissue culture plate (Nunc, Serving Life Science, Denmark). Cell preparations were either stimulated or not stimulated with 10 mU/ml human luteinizing hormone (100 μl per well) (LH) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 4 hr. The control used throughout this study comprised of cells in medium only. At the end of the incubation time, culture supernatants were harvested and screened for testosterone synthesis using commercially available testosterone enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (DRG Instruments GmbH, Germany). These kits supplied all the necessary reagents for the assay and the procedure was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions (17).

Statistical analysis

All data was statistically analysed using SigmaStat software (Systat Software Inc., USA). The t-test was performed to determine immunoglobulin synthesis between the molasses and control treated groups. One way ANOVA was used to determine testosterone synthesis between the molasses and control treated groups under stimulated and unstimulated conditions. All assays were performed in triplicate to prevent statistical errors and data was expressed as the mean±SEM.

Results

General observations, body weight, fluid intake

The molasses-treated mice appeared to be more aggressive than controls. For this reason, treated animals were further separated and housed as two mice per cage. After day 40 of molasses supplementation, mice exhibited signs of loose faeces. Between day 20 and day 60, treatment groups consumed significantly more fluid in comparison to the control groups (P<0.05) as shown in Table 1. However, there was no significant weight gain observed for treated or control groups (P>0.05) as per Table 2.

Table 1.

Drinking volumes (ml/mouse) obtained for molasses treated and control mice for exposure period

| Group | D10 | D20 | D30 | D40 | D50 | D60 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 5.17 ± 0.06 | 4.94 ± 0.05 | 5.16 ± 0.16 | 5.47 ± 0.08 | 4.94 ± 0.03 | 5.44 ± 0.08 |

| Molasses | 6.18 ± 0.45 | 7.79± 0.80* | 8.42 ± 0.78* | 8.57 ± 0.61* | 11.26 ± 0.85* | 12.83 ± 0.82* |

All values are expressed as the mean ± SEM, where n=6 for the control and treatment groups. Oral intake of each group was monitored for the exposure period D10-D60 i.e. Day 10 (oral consumption at day 10) up to Day 60 (oral consumption at end of experiment). An asterisk

designates the statistical difference when compared to the control (P<0.05)

Table 2.

Body weight (g/mouse) of molasses treated and control mice for exposure period

| Group | D0 | D10 | D20 | D30 | D40 | D50 | D60 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 29.02 ± 0.50 | 29.24 ± 0.39 | 30.13 ± 0.39 | 30.38 ± 0.51 | 30.87 ± 0.57 | 30.95 ± 0.51 | 31.68 ± 0.48 |

| Molasses | 27.54 ± 0.70 | 28.40 ± 0.58 | 29.13 ± 0.61 | 29.25 ± 0.58 | 29.39 ± 0.57 | 29.42 ± 0.77 | 30.01 ± 0.62 |

All values are expressed as the mean ± SEM, where n=6 for the control and treatment groups. Body weight (BW) was recorded for the exposure period D0-D60 i.e. Day 0 (initial BW at the start of the experiment) up to Day 60 (final BW at the end of the experiment)

Effect of molasses on serum biomarkers

Immunised and non-immunised animals that were exposed to molasses treatment showed no significant difference to their respective control groups when measuring haematocrit levels, total protein, LDH and plasma AST, ALT and ALP levels (P>0.05) (data not shown).

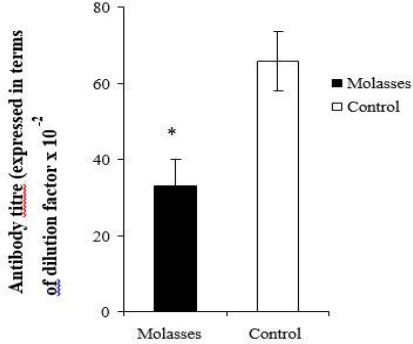

The effect of molasses on the immune system

The measurement of IgG anti-antigen was used to determine the impact of molasses on humoral immunity. Figure 1 shows a significant reduction in serum levels of IgG anti-antigen for the treatment group when compared to the control group (P=0.004).

Figure 1.

The effect of sugar cane molasses on IgG anti-antigen titre in molasses treated and untreated mice. Each point is the mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean) of three replicates (n=18). An asterisk (*) indicates statistical difference when compared to the control (P<0.05)

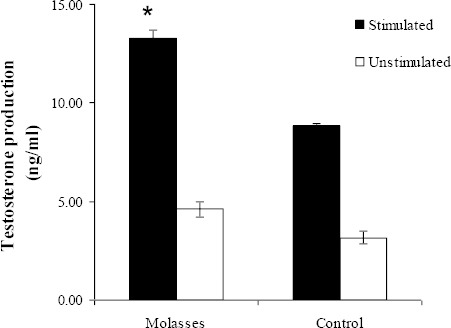

The effect of molasses on the reproductive system

Figure 2 illustrates the ex vivo effect of molasses on testosterone secretion using testicular cell cultures. Exposure of mice to molasses significantly increase LH induced testosterone production when compared to the control animals (P=0.001).

Figure 2.

The effect of sugar cane molasses on testosterone synthesis in testicular cell cultures. Each point is the mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean) of three replicates (n=18). An asterisk (*) indicates statistical difference when compared to the control (P<0.05). Stimulated=▄; Unstimulated=□

Discussion

The fluid intake of molasses-treated mice was significantly higher which appeared to provoke the onset of loose stools observed in treated animals. Total protein concentration levels of the experi-mental and control groups were similar, suggesting that the effects seen in the experimental group were due to molasses consumption and not as a consequence of dehydration. Studies have shown that cattle fed diets containing moderate to high levels of molasses suffer with loose faeces, which is often associated with diarrhoea. Sucrose and potassium in molasses have been implicated as causal factors in the development of digestive problems seen in animals and may also contribute to the laxative property of this compound (24).

This study investigated the effects of molasses on the humoral immune system by assessing antibody production in immunised animals. Molasses signi-ficantly inhibited the IgG response in treated animals, contrasting in vitro data which indicated that molasses stimulates humoral immunity (18). In vivo exposure to molasses may be associated with an inability to produce an effective humoral immune response when challenged with an antigen. IgG plays a defensive role against bacterial pathogens such as serogroup B and Neisseria meninigitis in humans (25) and a suboptimal immune response may be associated with an increased susceptibility to these extracellular pathogens. The immunosuppressive potential of molasses, resulting from prolonged exposure, may also enhance the risk of already immunocompromised individuals to the develop-ment of infection.

Testosterone production is an important index of potential reproductive toxicity. Any changes resulting in suppression of testosterone synthesis may lead to detrimental effects on reproductive processes such as spermatogenesis. This steroid hormone is vital in maintaining the function and organization of accessory sex glands in males (26). In vitro studies demonstrated the stimulatory effect of molasses on testosterone biosynthesis in male mice (20). In accordance with this finding, this study also shows that under stimulatory conditions molasses induces a significant elevation on plasma testosterone in vivo.

For many years, traditional healers have used plants, fungi and insects to enhance libido and improve fertility. The fungal parasite, Cordyceps sinensis has been used extensively by the Chinese as a tonic herb to improve and restore sexual performance. Studies have shown that Cordyceps sinensis exhibits an enhancing effect on testosterone secretion both in vitro and in vivo (27). It has been suggested that the stimulatory effect of C. sinensis on testosterone synthesis may prove to be beneficial in treating males that suffer from reproductive dysfunction as a result of inadequate testosterone synthesis (27). Since molasses displays a similar enhancing effect on testosterone secretion, the use of molasses may also be potentially favourable in improving reproductive function and sexual performance.

Conclusion

This study postulates that molasses has potential adverse or beneficial effects on certain physiological systems. Findings for this study show that exposure to molasses in vivo produces an immunosuppressive effect, suggesting that molasses may reduce the humoral immune response when administered daily over a prolonged period. The effect of molasses on the male reproductive system demonstrates its potential to enhance testosterone production in vivo. In accordance with previous studies, these findings promote the use of molasses as a supplement to enhance testosterone production, improving reproductive health. Data obtained from this study provides valuable information on the biological activity of molasses on various physiological systems that may prove to be useful in further in vivo testing.

Acknowledgment

We are thankful for the financial contribution by the National Research Foundation of South Africa and the DAAD (Deutscher Akademishcer Austausch Dienst) foundation in Germany to this project.

The results described in this paper were part of a student’s PhD thesis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wang BS, Chang LW, Kang ZC, Chu HL, Tai HM, Huang MH. Inhibitory effect of molasses on mutation and nitric oxide production. Food Chem. 2011;126:1102–1107. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reyed RM, El-Diwany A. Molasses as bifidus promoter on bifidobacteria and lactic acid bacteria growing in skim milk. [Accessed Feb 18 2010];Internet J Microbiol [serial online] 2008 5:21. Available from: http://www.ispub.com . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guimarães CM, Gi˜ao MS, Martinez SS, Pintado AI, Pintado ME, Bento LS, et al. Antioxidant activity of sugar molasses including protective effect against DNA oxidative damage. J Food Sci. 2007;72:C39–C43. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2006.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grandics P. Cancer: A single disease with a multitude of manifestions? [Accessed 2010 Aug 10];J Carcinog [serial online] 2003 2 doi: 10.1186/1477-3163-2-9. Available from: http://www.carcinogenesis.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saska M, Chou CC. Antioxidant properties of sugar cane extracts. Proceedings of the First Biannual World Conference on Recent Development in Sugar Technologies in USA. Delray Beach, Florida, USA: 2002. May 16-17, [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kubena K, McMurrray DN. Nutrition and the immune system: A review of nutrient-nutrient interactions. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;96:1156–1164. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Jong WH, Van Loveren H. Screening of xenobiotics for direct immunotoxicity in an animal study. Methods. 2007;41:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krzystyniak K, Tryphonas H, Fourier M. Approaches to the evaluation of chemical induced immunotoxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103:17–22. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagai Y, Mizutani T, Iwabe H, Araki S, Suzuk M. Physiological functions of sugar cane extracts. Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of Sugar Industry Technologists in Taiwan. Taipei, Taiwan: 2001. May, [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koge K, Nagai Y, Ebashi T, Iwabe H, El-Abasy M, Motobu M, et al. Physiological functions of sugar cane extracts: Growth promotion, immunopotentiation and anti-coccidial infection effects in chickens. Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of Sugar Industry Technologists in USA. Delray Beach, Florida, USA: 2002. May, [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cellar M. Molasses as a possible cause of endocrine disruptive syndrome in cattle. [dissertation] South Africa: Pretoria University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preston TR, Sansoucy R, Aarts G, editors. Molasses as animal feed: An overview. Proceedings of an FAO Expert Consultation on Sugarcane as Feed. Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masgoret MS, Botha CJ, Myburgh JG, Naudé TW, Prozesky L, Naidoo V, et al. Molasses as a possible cause of an “endocrine disruptive syndrome.”. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2009;76:209–225. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v76i2.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans JT. In: Reproductive toxicity and endocrine disruption. Veterinary Toxicology. Gupta RC, editor. New York: Elsevier Inc; 2007. pp. 206–244. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ncibi S, Othman NB, Akakha A, Krifi MN, Zourgui L. Opuntia ficus India extract protects against chlorpyrifos-induced damage to mice liver. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:797–802. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stamati PN, Pitsos MA. The impact of endocrine disruptors on the female reproductive system. Hum Reprod Upd. 2001;7:323–330. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahiman F, Pool EJ. Preliminary study on the effect of sugar cane (Saccharum officinarum) molasses on steroidogenesis in testicular cell cultures. Afr J Food Sci. 2010;4:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahiman F, Pool EJ. The effects of Saccharum officinarium (sugar cane) molasses on cytokine secretion by human blood cultures. J Immunoassay Immunochem. 2010;31:148–159. doi: 10.1080/15321811003617453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinemann WW, Hanks EM. Cane Molasses in Cattle Finishing Rations. J Anim Sci. 1977;45:13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowe JB, Bobadilla M, Fernandez A, Encarnacion JC, Preston TR. Molasses toxicity in cattle: rumen fermentation and blood glucose entry rates associated with this condition (1977) Trop Anim Prod. 1977;4:78–89. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bachmanov AA, Reed DR, Beauchamp GK, Tordoff MG. Food intake, water intake and drinking spout side preference of 28 Mouse Strains. Behav Genet. 2002;32:435–443. doi: 10.1023/a:1020884312053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institute of Health (US). Guidelines for the use of adjuvants in research. National Institute of Health, Office of animal care and use. 2007. [Accessed Jan 10, 2010]. Available from: http://www.oacu.od.nih.gov/ arac/-freunds.pdf .

- 23.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pate FM. Molasses in beef nutrition. In: Molasses in animal nutrition. Iowa: National Feed Ingredients Association; 1983. [Accessed 11 Feb 2009]. Available from: http://rcrec-ona.ifas.ufl.edu/pdf/publications/molasses-beef-nutrition.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin JY, Lu S, Liou YL, Liou HL. Increased IgA and IgG serum levels using a novel yam-boxthorn noodle in a BALB/C mouse model. Food Chem Toxicol. 2006;44:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karacaoğlu E, Selmanoğlu G. Effects of heat-induced food contaminant furan on reproductive system of male rats from weaning through postpuberty. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:1293–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu CC, Huanga YL, Tsaib SJ, Sheuc CC, Huanga BM. In vivo and in vitro stimulatory effects of Cordyceps sinensis on testosterone production in mouse Leydig cells. Life Sci. 2003;73:2127–2136. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00595-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]