Abstract

A male with human immunodeficiency virus infection presented with febrile encephalopathy followed by seizures and left hemiparesis. Initial imaging with contrast computerized tomography (CT) scan brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination were normal. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging brain revealed bilateral parieto-occipital infarcts with bleed. He did not improve on treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics, anti-tubercular drugs, and antifungals. He finally succumbed to the disease. His CSF culture grew Aspergillus after 2 weeks. Central nervous system (CNS) aspergillosis can present with variable presentations, and initial CT scan and CSF examination can be normal, especially in the immunosuppressed. High index of suspicion is required for the diagnosis of invasive CNS Aspergillus in the immunosuppressed.

Key words: Aspergillosis, human immunodeficiency virus, meninigoencephalitis

INTRODUCTION

Aspergillus can affect the central nervous system (CNS) in immunocompromised individuals and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.[1,2,3,4] Here, we report a case of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture-proven CNS aspergillosis in a middle-aged male with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive illness who presented with febrile encephalopathy, seizures, and pancytopenia with normal contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CECT) scan brain and normal initial CSF studies. High index of suspicion is necessary in considering fungal infections as a cause of meningoencephalitis; early diagnosis and initiation of potent antifungal may reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with this condition.

CASE REPORT

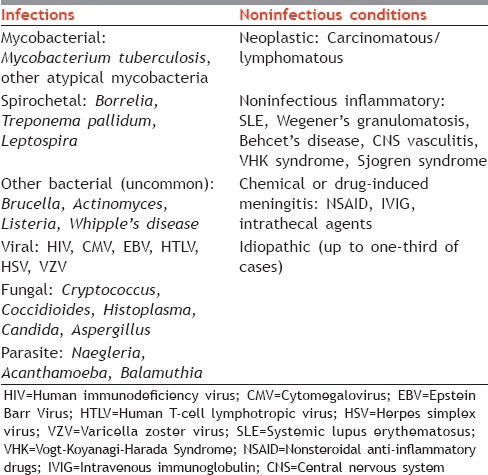

A 59-year-old male having HIV positive illness for around 10 years, without any documented evidence of adhering to specific antiretroviral therapy regimen, presented to our hospital with history of low-grade fever, reduced appetite, and weight loss over 2 months followed by headache for about 2 weeks with recent worsening in the form of development of left-sided focal seizure with secondary generalization followed by altered sensorium for 3 days. He was started on empirical antitubercular medicines for last 2 weeks by a private practitioner before presenting to us. On presentation, he was febrile and drowsy. He had left hemiparesis with generalized brisk reflexes, extensor plantar response, and positive meningeal signs. Other systemic examination was unremarkable. A diagnosis of chronic meningitis in an immunocompromised individual was considered. Chronic meningitis in an immunocompromised patient has multiple differentials as enlisted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of chronic meningitis (important causes to consider, especially in the immunosuppressed)

On investigations, he had pancytopenia (hemoglobin 6.8 g/dl, total leukocyte counts 3100/mm3, absolute neutrophil counts 2200/mm3, platelet counts 62,000/mm3) with normal glucose, electrolytes, and renal and hepatic functions. His chest X-ray showed right middle zone and left upper zone consolidation. Radiological differential diagnoses of this type of consolidation are bacterial pneumonia, tuberculosis, atypical mycobacterial infection, fungal infection, and lymphomatous or other neoplasm. He needed a CECT thorax and bronchoscopy-guided biopsy was advised but could not be done due to financial constraints and because the relatives declined any invasive procedure. His CECT head was normal [Figure 1]. CSF was acellular with normal glucose and protein level. CSF Gram stain, acid-fast bacillus stain, potassium hydroxide mount, India ink and cryptococcal antigen tests, and cytology for malignant cells were negative. CSF mycobacterial and fungal culture was also sent at the same time. As his focal deficits were not explained by a normal CECT head, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain was done which revealed small, fairly defined, multiple altered signal intensity areas in the posterior aspect of right temporal lobe, posterolateral aspects of both the occipital lobes and anteroinferior portion of right frontal lobe on the gray-white matter junction, showing blooming on gradient images and peripheral enhancement on contrast-enhanced study associated with minimal to mild surrounding edema with normal MR angiogram, suggestive of hemorrhagic infarcts secondary to vasculitis. A differential diagnosis of this imaging feature in an immunocompromised is enumerated in Table 2.

Figure 1.

(a) Plain computerized tomography scan of brain, (b) contrast-enhanced scan, (c) T1 axial view (d) T2 axial view, (e) fluid-attenuated inversion recovery axial view, (f) gradient image, (g) diffusion weighted image, (h) apparent diffusion coefficient image

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis of magnetic resonance imaging suggesting ischemic areas at gray-white interface along with intracerebral bleed (central nervous system vasculitis)

He was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, empirical antitubercular drugs, antiepileptic drugs, and other supportive measures without any significant clinical improvement or deterioration. His toxoplasma antibodies were negative. His blood sample was sent for CD4 count analysis, but we could not get countable CD4 cells on flow cytometry despite doing the test twice in two different laboratories. The method used for detection of CD4 cells in flow cytometry was pan-leukocyte (CD45+) gating strategy by single platform technique. To get final diagnosis, CT scan chest, bronchoscopy, galactomannan test, and brain biopsy were considered but could not be done due to financial constraints. Considering febrile encephalopathy in a patient with HIV, febrile neutropenia and no response to 2 weeks of antibiotics and antitubercular drugs given before coming to our hospital, empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics in the form of meropenem, vancomycin with voriconazole and amphotericin B were started. In developing countries like India, upper lobe consolidation with clinical spectrum of chronic meningitis in immunocompromised individuals like HIV, tuberculosis remains one of the important differential diagnoses. Hence, antitubercular therapy was continued in his case due to high index of suspicion, which was already started 2 weeks before his presenting to us, pending reports of sputum and blood culture. Despite the above therapy for 4 days of hospitalization, there was no major improvement in his condition. Due to financial and social reasons, patient took discharge against medical advice 4 days after hospitalization. Due to our keen interest in the condition of the patient as well as the atypical MRI brain and CSF findings, we continued with our efforts to find the cause of his condition by serial observing his blood and CSF cultures. After 10 days, his CSF culture showed growth of A. niger. We got aware of his death on following up later with the family.

DISCUSSION

Aspergillus is a ubiquitous fungus that lives in soil and decaying vegetation.[4,5] A. fumigatus is the most common species of Aspergillus family, others being A. niger and A. flavus.[4,5,6]Aspergillus most commonly involves lungs followed by sinus (maxillary > sphenoid), skin, eye, ear, and bones.[5] The incidence of invasive aspergillosis in HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients varies between 0% and 12%.[3] Portal of entry is respiratory tract with inhalation of spores although entry through the skin and gastrointestinal tract has also been reported.[4] CNS involvement is mainly due to hematogenous spread rather than via direct spread of infection from sinus, orbit, nose, and ear.[4,6,7,8]Aspergillus targets blood vessels and invades them producing a thrombus, hemorrhage, or rarely mycotic aneurysm.[1,4,9] Hemorrhagic infarct is the most common pathologic finding on autopsy.[10] Risk factors for developing this rare CNS infection are recipients of immunosuppressive disorders such as HIV/AIDS, solid organ transplants, patients on chemotherapy, diabetes, heroin abuse, long-term steroid or broad-spectrum antibiotics use, neutropenia, history of opportunistic infection, and use of ganciclovir/valacyclovir.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

Aspergillus has a worldwide distribution, most commonly growing in decomposing plant materials (i.e., compost) and in bedding. Aspergilli are found in indoor and outdoor air, on surfaces, and in water from surface reservoirs. The required size of the infecting inoculum is uncertain; however, only intense exposures (e.g., during construction work, handling of moldy bark or hay, or composting) are sufficient to cause disease in healthy immunocompetent individuals. The primary risk factors for invasive aspergillosis are profound neutropenia and glucocorticoid use; risk increases with longer duration of these conditions. Neutrophil and/or phagocyte dysfunction is also an important risk factor, as evidenced by aspergillosis in chronic granulomatous disease, advanced HIV infection, and relapsed leukemia. In HIV patients, it can occur irrespective of specific CD4 count. Patients with aspergillosis may also be immunocompetent except for some cytokine regulation defects, most of which are consistent with an inability to mount an inflammatory immune (Th1-like) response.[11] Aspergillosis among immunocompetent hosts may have less invasive course with early and better response to therapy and better prognosis compared to among immunosuppressed hosts.

The first case of aspergillosis involving the brain was reported by Oppe in 1897.[6,9] The first culture-proven case of brain abscess due to A. fumigatus was reported in a Brazilian AIDS patient.[3] Patients usually present with headache, seizures, altered mental status, paresthesia, and cranial nerve palsies.[4,6] Rhinocerebral form of aspergillosis can present with sinusitis followed by base of skull involvement with the development of cavernous sinus syndrome or orbital apex syndrome and is more common than isolated cerebral aspergillosis. CNS aspergillosis may present with varied manifestations including meningitis, meningoencephalitis, brain abscess or granuloma formation, subdural abscess, mycotic arteritis with intracerebral hemorrhage, and angioinvasive disease with vasculitis.[7] Lesions are located in cerebral hemispheres, basal ganglia, thalamus, corpus callosum, and perforating arterial territories. Strong clinical suspicion can lead to identification of this uncommon entity, and early diagnosis and treatment can be life-saving.[1,4] CSF examination may be acellular in CNS aspergillosis which is very unusual as far as any CNS infection is concerned.[1] Denning reviewed the therapeutic outcome in 1223 cases of invasive aspergillosis from 1972 to 1995. Case-fatality rates (CFRs) were 99%, 86%, and 66% for cerebral, pulmonary, and sinus aspergillosis, respectively. In Denning's review, therapeutic outcome varied according to underlying disease, site of infection, and antifungal management. Overall, CNS aspergillosis has CFR of 85–100%.[1,6] The exact incidence of CNS aspergillosis in India is not known, but in a retrospective study from southern India, Sundaram et al. reported 73 proven cases of CNS aspergillosis between 1988 and 2004.[12]

The patient's routine CSF studies were normal. Still CSF fungal culture was sent in view of severe pancytopenia, HIV positive status, and MRI findings suggestive of angioinvasive disease with infarcts as well as bleed suggestive of ongoing vasculitic process in the brain. CSF fungal culture is essential in immunocompromised patients even if CSF routine and microbiology investigations are normal. Early diagnosis and initiation of potent antifungal may reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with this condition. Furthermore, in patients with severe pancytopenia, CSF studies may not show pleocytosis despite on-going meningoencephalitis as the patients may not be able to mount an adequate inflammatory response to infection. Thus, high index of suspicion is necessary in considering fungal infections as a cause of meningoencephalitis especially in immunocompromised patients and a normal routine CSF examination should not deter the physicians from sending CSF fungal culture in such patients. Like in most immunocompromised individuals, no other sources of transmission of infection could be identified in our case. Though we had growth of Aspergillus on the CSF culture, we cannot deny that the patient also could have had combined tubercular and fungal infection; but we want to highlight by this case that in severely immunosuppressed individuals, a CSF may be normal despite the presence of meningitis.

There were some of the limiting factors in reporting this case. First, CD4 count assessment was not possible, despite trying in two different laboratories, it was not clear whether this was due to very low CD4 count leading to uncountable cells or due to some sampling error. Second, the patient's relatives withdrew from further treatment due to financial constraints and also a brain biopsy could not be done to further confirm the diagnosis. On telephonic follow-up, the patient was found to have died at home about 1 week after taking discharge against medical advice. The patient had severe immunosuppression due to HIV/AIDS and had associated disseminated pulmonary-CNS infection which may have led to severe sepsis and multiorgan failure leading to death; however, in the absence of pathologic autopsy, the final cause is difficult to be ascertained.

CNS angioinvasive presentation of aspergillosis can present with normal CSF findings and normal CECT head. CSF fungal culture should be sent in all immunocompromised patients with febrile encephalopathy. An acellular CSF should not be considered by physicians to be the absence of intracranial infection in such a setting of severe immunosuppression.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Norlinah MI, Ngow HA, Hamidon BB. Angioinvasive cerebral aspergillosis presenting as acute ischaemic stroke in a patient with diabetes mellitus. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:e1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinez R, Castro GD, Machado AA, Moya MJ. Primary aspergilloma and subacute invasive aspergillosis in two AIDS patients. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2009;51:49–52. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652009000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vidal JE, Dauar RF, Melhem MS, Szeszs W, Pukinskas SR, Coelho JF, et al. Cerebral aspergillosis due to Aspergillus fumigatus in AIDS patient: First culture-proven case reported in Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2005;47:161–5. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652005000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fasciano JW, Ripple MG, Saurez JI, Bhardwaj A. Central nervous system aspergillosis: A case report and literature review. Hosp Physician. 1999;35:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denning DW. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:781–803. doi: 10.1086/513943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pongbhaesaj P, Dejthevaporn C, Tunlayadechanont S, Witoonpanich R, Sungkanuparph S, Vibhagool A. Aspergillosis of the central nervous system: A catastrophic opportunistic infection. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2004;35:119–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JC, Lim DJ, Ha SK, Kim SD, Kim SH. Fatal case of cerebral aspergillosis: A case report and literature review. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012;52:420–2. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2012.52.4.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murthy JM. Fungal infections of the central nervous system: The clinical syndromes. Neurol India. 2007;55:221–5. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.35682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balasubramaniam P, Madakira PB, Ninan A, Swaminathan A. Response of central nervous system aspergillosis to voriconazole. Neurol India. 2007;55:301–3. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.35694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phuttharak W, Hesselink JR, Wixom C. MR features of cerebral aspergillosis in an immunocompetent patient: Correlation with histology and elemental analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:835–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denning DW. Aspergillosis. In: Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Fauci AS, Longo DL, Loscalzo JL, editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 19th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Publishers; 2015. p. 1345. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sundaram C, Umabala P, Laxmi V, Purohit AK, Prasad VS, Panigrahi M, et al. Pathology of fungal infections of the central nervous system: 17 years' experience from Southern India. Histopathology. 2006;49:396–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]