Abstract

BACKGROUND

Although interventions exist to reduce violent crime, optimal implementation requires accurate targeting. We report the results of an attempt to develop an actuarial model using machine learning methods to predict future violent crimes among U.S. Army soldiers.

METHODS

A consolidated administrative database for all 975,057 soldiers in the U.S. Army in 2004-2009 was created in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). 5,771 of these soldiers committed a first founded major physical violent crime (murder-manslaughter, kidnapping, aggravated arson, aggravated assault, robbery) over that time period. Temporally prior administrative records measuring socio-demographic, Army career, criminal justice, medical/pharmacy, and contextual variables were used to build an actuarial model for these crimes separately among men and women using machine learning methods (cross-validated stepwise regression; random forests; penalized regressions). The model was then validated in an independent 2011-2013 sample.

RESULTS

Key predictors were indicators of disadvantaged social/socio-economic status, early career stage, prior crime, and mental disorder treatment. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was .80-.82 in 2004-2009 and .77 in a 2011-2013 validation sample. 36.2-33.1% (male-female) of all administratively-recorded crimes were committed by the 5% of soldiers having highest predicted risk in 2004-2009 and an even higher proportion (50.5%) in the 2011-2013 validation sample.

CONCLUSIONS

Although these results suggest that the models could be used to target soldiers at high risk of violent crime perpetration for preventive interventions, final implementation decisions would require further validation and weighing of predicted effectiveness against intervention costs and competing risks.

Keywords: crime perpetration, physical violence, military violence, risk model, actuarial model, machine learning

Growing concern exists about violence committed by military personnel (Department of the US Army, 2012, Institute of Medicine, 2010). Between 305 and 399 violent felonies were committed per year during the years 2006-2011 for every 100,000 U.S. Army soldiers (Department of the US Army, 2012), while close to 4% of soldiers in post-deployment surveys reported recent physical fights where they used a knife or gun (Gallaway et al., 2012, MacManus et al., 2015, Sundin et al., 2014, Thomas et al., 2010). The U.S. Army has implemented several programs to address this problem (Department of Defense Instruction, 2014, Fort Lee, 2014), but these programs are mostly universal interventions aimed at training all soldiers in basic violence prevention strategies. Cost-effective prevention sometimes also requires more intensive targeted interventions for individuals at high risk (Foster and Jones, 2006, Golubnitschaja and Costigliola, 2012). Actuarial methods are needed to determine who is at high risk of perpetrating violence (Fazel et al., 2012, Skeem and Monahan, 2011). A number of actuarial violence prediction tools have been developed for this purpose to screen psychiatric patients (Higgins et al., 2005, Monahan et al., 2005), incarcerated criminals (Berk and Bleich, 2014, Monahan and Skeem, 2014), and workers (LeBlanc and Kelloway, 2002, Meloy et al., 2013) for high-risk preventive interventions, but no such tool has been developed for Regular Army soldiers. One way to do so would be to use the administrative databases available for all soldiers to develop an actuarial model based on modern machine learning methods (Berk, 2008). Although it is unclear how well the variables in existing administrative databases could predict future violent crimes, these data were recently used successfully to develop an actuarial model for post-hospitalization suicides among U.S. Army soldiers (Kessler et al., 2015). The current report presents the results of an attempt to develop a comparable model for violent crime perpetration among U.S. Army soldiers. We focus on non-familial physical violent crimes, excluding family violence and sexual violence , based on evidence that their predictors are different from the predictors of non-familial physical violence (Elbogen et al., 2010a, Marshall et al., 2005, Mohammadkhani et al., 2009, Sullivan and Elbogen, 2014).

METHOD

Sample

The sample in which the model was developed (referred to in the machine learning literature as the “training sample”) was the Historical Administrative Data System (HADS) of the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) (Ursano et al., 2014). Army STARRS is an epidemiological-neurobiological study of risk and resilience factors for suicide and related outcomes in the U.S. Army. The HADS was developed originally to provide administrative data on the correlates of soldier suicides. The HADS brings together data from 38 Army/Department of Defense administrative data systems (Appendix Table 1) for the 975,057 Regular U.S. Army soldiers serving between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2009 (Kessler et al., 2013). The outcome variable was a dichotomous measure of the first accusation of a major physical violent crime, not occurring within the soldier's family, for which the Army found sufficient evidence to warrant a full investigation (although not necessarily enough for a conviction). Such an event was recorded in the administrative records of 5,771 soldiers in the population.

As detailed below, we analyzed the HADS using discrete-time survival analysis (Willett and Singer, 1993) with person-month the unit of analysis. That is, each month in the career of each soldier over the time interval between January 2004 and December 2009 was used as a separate observational record. We developed actuarial models to predict whether soldiers who had never been accused of committing a major physical violent crime were accused of doing so in each of those months. The independent variables in the models were administrative variables available for the soldier the month prior to the month of the accusation. Person-months were censored either at termination of Regular Army service or after the month when the crime occurred, whichever came first. There were approximately 37 million person-months in the HADS, 5,771 of which were coded 1 on our dichotomous outcome variable. Rather than work with all possible control person-months (coded 0 on the outcome variable) in our analysis, we used the logic of case-control analysis (Schlesselman, 1982) to select a probability sample of control person-months that we weighted by the inverse of their probability of selection. Unbiased estimates of the odds-ratios of significant independent variables in the model were obtained by analyzing all cases along with this weighted probability sample of control person-months. We then tested the model in an independent validation sample of 43,248 soldiers who participated in Army STARRS surveys carried out in 2011-2012 and who were subsequently followed in administrative records through 2013 (roughly 10 million person-months). The STARRS survey samples, which are described in detail elsewhere (Kessler et al., 2013), consisted of probability samples of soldiers at all phases of the Army career.

Measures

Dependent variable

Data from 5 HADS datasets were combined to identify the date, type, and judicial outcome of all crimes that occurred over the study period. Crime types were classified using the Bureau of Justice Statistics National Corrections Reporting Program (NCRP) classification system (U.S. Department of Justice, 2009). We then defined our outcome as first founded major physical violent crimes committed against someone other than a family member. A “founded” crime is one for which the Army found evidence sufficient to warrant a full investigation based on NCRP codes for murder-manslaughter, kidnapping, aggravated arson, aggravated assault, and robbery. As noted above, 5,771 soldiers met this definition. Such “founded” cases exclude those that do not pass a test of probable cause based on review of the totality of the circumstances. This focus on founded offenses is consistent with other research (Department of the US Army, 2012, Army Suicide Prevention Task Force, 2010, Skeem et al., 2015, Steadman et al., 2015), which virtually always uses arrest rather than conviction as a dependent variable based on the fact that arrest records reflect actual violent behaviors much more closely than conviction records. Conviction records among founded cases, in comparison, largely reflect the vagaries of bureaucratic processing by the criminal justice system, including the fact that some soldiers with founded offenses escape conviction by accepting a Discharge Under Other Than Honorable Conditions (UOTHC) in lieu of court martial.

Our focus on first founded offenses is due to the fact that the vast majority of all founded major physical violent crimes in the U.S. Army are first offenses (75% among men and 84% among women) and most repeat offenses committed prior to initial apprehension. Recidivism in the classical sense (i.e., a repeat offense after being released from prison for the first offense) is rare in the military, as convicted major violent crime offenders typically receive a dishonorable discharge immediately after serving a sentence, while soldiers with founded crimes who accept UOTHC discharges are discharged immediately at the time of release from custody.

Our focus on non-familial physical violence (i.e., excluding familial violence and sexual assaults) was not based on the comparatively high prevalence of this type of crime. Indeed, the number of soldiers with founded non-familial major physical violence was smaller during the years of this study (n=5,771) than the number with familial physical violence (15,154), although non-familial sexual violent crime (6,198) was much more common than familial sexual violent crime (718). However, as noted in the introduction, previous research suggests that the predictors of these different types of violent crime vary (Elbogen et al., 2010a, Marshall et al., 2005, Mohammadkhani et al., 2009, Sullivan and Elbogen, 2014), leading us to focus on each of them separately. While the current report presents the results of our model-building efforts to predict non-familial major physical violence, separate reports will have the results of attempts to build comparable models for the other types of violence.

Potential predictors

Numerous epidemiological studies have examined predictors of violence among active duty military personnel (Gallaway et al., 2012, Killgore et al., 2008, MacManus et al., 2012a, MacManus et al., 2012b, MacManus et al., 2013) and veterans (Elbogen et al., 2014a, Elbogen et al., 2013, Elbogen et al., 2012, Elbogen et al., 2014b, Elbogen et al., 2010b, Hellmuth et al., 2012, Jakupcak et al., 2007, Sullivan and Elbogen, 2014). A recent review (Elbogen et al., 2010a) organized the significant predictors in these studies into four broad categories: socio-demographic and dispositional (e.g., sex, race-ethnicity, personality); historical (e.g., childhood experiences, military career experiences, prior violence); clinical (e.g., mental and physical disorders); and contextual-environmental (e.g., access to weapons). Given that our analysis was carried out opportunistically (i.e., selecting our measures of potential predictors from administrative data collected for other purposes), we were not able to operationalize all the significant predictors in previous studies. However, 446 HADS variables were found that could be used as indicators of previously-documented predictors. These included 21 socio-demographic variables, 38 variables defining military career experiences, 66 variables representing prior crime perpetration and victimization, 282 clinical variables (treated mental and physical disorders and medications), and 39 contextual-environmental variables (e.g., unit characteristics defined at the battalion level, registered weapons). A complete description of these independent variables is available online (Appendix Tables 3-6).

Analysis methods

Data analysis was carried out remotely by analysts from Harvard Medical School on the secure Army STARRS Data Coordination Center server at the University of Michigan. De-identified HADS analysis was approved by the Human Subjects Committees of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences for the Henry M. Jackson Foundation (the primary Army STARRS grantee), the University of Michigan, and Harvard Medical School. The governing IRBs did not require obtaining informed consent from individual soldiers because the data were de-identified.

Cross-tabulations were used to calculate outcome incidence. Incidence was expressed as the number of founded accusations per 1,000 person-years for descriptive purposes. However, model-building was not based on an incidence analysis, but rather on discrete-time person-month survival analysis (Willett and Singer, 1993). This is an important distinction because previous research has shown that the examination of risk factors based on incidence analysis can yield inaccurate results (Kraemer, 2009). It is noteworthy in this regard that our models examined risk factors for the first occurrence of a founded major physical violent crime in each month of the career of each soldier in the Army between January 2004 and December 2009. The models allowed for time-varying values of the risk factors as the vast majority of variables had values that changed over time (e.g., the soldier's rank, time in service, history of prior health care visits, etc.). Because of these time-varying values, the model could assign a different predicted probability of the outcome to a single soldier each month, allowing us to examine the possible existence of critical high-risk time periods in the careers of individual soldiers. This, coupled with the fact that the independent variables in our models are routinely updated for each soldier each month, means that the Army could use our models to generate a new predicted probability of committing a violent crime in the next 1, 6, or 12 months (or over any other designed future risk period) for each soldier each month. Given the existence of hypotheses suggesting that risk factors for violence are different for men and women (Whittington et al., 2013), separate sex-specific models were developed.

The major challenge in developing an actuarial prediction model from a data array of this type is that the existence of such a large number of predictors introduces the possibility of over-fitting, which would lead to poor performance of the model when it was applied to future time periods. Machine learning methods are designed to minimize this problem by using iterative cross-validation to select a stable and optimal subset of predictors (Kohavi, 1995). A six-step process was used to achieve this end.

-

(1)

Bivariate associations of temporally prior independent variables with the subsequent occurrence of the outcome were examined in our person-month dataset controlling for historical time using proc logistic in SAS Version 9.3(SAS Institute Inc., 2010). This step was conducted in a pooled dataset across the entire 72-month study period using a logistic link function and including control variables for time (i.e., month and year) to adjust for temporal trends in crime rates.

-

(2)

The functional forms of significant bivariate associations involving non-dichotomous independent variables were transformed to capture substantively plausible nonlinearities.

-

(3)

Multivariate associations were estimated in a logistic models that included all independent variables that were significant in bivariate analyses.

-

(4)

As coefficients in the multivariate models were unstable, the method of 10-fold cross-validated forward stepwise regression was used to select the optimal number of significant independent variables to maximize the proportion of observed crimes found among the 5% of soldiers with highest cross-validated predicted risk. Ten-fold cross-validation is a method that estimates 10 separate stepwise models, each time holding out a separate 10% of the population, and then uses the coefficients from each 90% subsample to generate a predicted probability only for the 10% of the population in the hold-out subsample (Kohavi, 1995). Changes in model fit associated with number of independent variables were then inspected in the aggregation of the 10 hold-out subsamples to determine the smallest number of independent variables needed to achieve optimal cross-validated prediction accuracy, thus minimizing risk of the over-fitting that often occurs when using stepwise regression analysis (Anderssen et al., 2006).

-

(5)

A search for stable interactions among independent variables in the optimal stepwise model was carried out using the R-package RandomForests (RF) (Liaw and Wiener, 2002). RF is a tree-based method that uses simulation across many different subsampled trees (in our models, 500 trees) to generate a single stable summary predicted outcome score capturing the significant interactions among the independent variables (Svetnik et al., 2003). The incremental improvement in fit achieved by using RF was determined by adding a variable representing the RF predicted probability to the optimal regression equation estimated in the previous step and determining the extent to which this led to an increase in the proportion of crimes committed by the 5% of soldiers with highest cross-validated predicted risk.

-

(6)

The R-package glmnet (Friedman et al., 2010) was then used to estimate elastic net penalized regression models. Penalized regression models trade off a small amount of bias in coefficients to increase the efficiency and stability of estimates (Zou and Hastie, 2005).

The coefficients in the optimal models were used to calculate the predicted probability of the outcome for each observation (person-month) in the dataset. The association between this predicted probability and the observed occurrence of the outcome (i.e., a given soldier actually being accused of committing one of the crimes considered here) was then used to calculate the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) as an estimate of model accuracy. In order to visualize this association, person-months were ranked by predicted probability from highest to lowest risk and then grouped into 20 categories of equal size (ventiles). The proportion of true-positive observations in each ventile was then calculated and graphed. Given the active debate about identifying high-risk individuals using information about race-ethnicity (Berk, 2009), all analyses were carried out both with and without race-ethnicity among the independent variables.

RESULTS

Incidence of perpetration by sex, time-in-service, and deployment status

Among soldiers who had never before been accused of one of the crimes considered here during their Army career, an average of 16.7 out of every 100,000 men and 7.5 out of every 100,000 women were accused of doing so in a given month over the study period. These numbers can be expressed equivalently as incidence rates of 2.0/1,000 person-years among men and 0.9/1,000 person-years among women. Incidence was significantly higher among men than women (χ21=329.9, p<.001) and inversely related to time-in-service (from highs of 3.8/1,000 person-years among men and 1.6/1,000 person-years among women in the second year of service to lows of 0.2-0.1/1,000 person-years after 20+ years of service; χ27=104.2-2002.6, p<.001). (Table 1) Over 50% of first occurrences of the outcome occurred in the first three years of service. Incidence was significantly lower among currently-deployed (0.9-0.3/1,000 person-years) than never-deployed (2.4-1.1/1,000 person-years) and previously-deployed (2.3-0.9/1,000 person-years; χ21=26.1-562.4, p<.001) men and women and generally declined with time-in-service in subgroups defined by the conjunction of sex and deployment status (Appendix Table 7).

Table 1.

Incidence/1,000 person-years of first founded accusations of non-familial major physical violent crime perpetration by time-in-service and sex among Regular Army soldiers in the Army STARRS 2004-2009 Historical Administrative Data Systems (HADS)a

| Men |

Women |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence/1,000 person-years |

Distribution of the crimes |

Population distribution |

Incidence/1,000 person-years |

Distribution of the crimes |

Population distribution |

|||||||||

| Years-in-Service | Est | (se) | (n)b | % | (se) | %c | (se) | Est | (se) | (n)b | % | (se) | %c | (se) |

| 0-1 | 2.6 | (0.1) | (823) | 15.3 | (0.5) | 12.1 | (0.1) | 0.8 | (0.1) | (48) | 12.1 | (1.6) | 13.8 | (0.5) |

| 1-2 | 3.8 | (0.1) | (1,105) | 20.6 | (0.6) | 11.1 | (0.1) | 1.6 | (0.2) | (86) | 21.7 | (2.1) | 12.0 | (0.5) |

| 2-3 | 3.4 | (0.1) | (924) | 17.2 | (0.5) | 10.3 | (0.1) | 1.5 | (0.2) | (67) | 16.9 | (1.9) | 10.6 | (0.5) |

| 3-4 | 3.1 | (0.1) | (732) | 13.6 | (0.5) | 8.8 | (0.1) | 1.2 | (0.2) | (47) | 11.9 | (1.6) | 9.4 | (0.4) |

| 4-5 | 2.2 | (0.1) | (377) | 7.0 | (0.4) | 6.4 | (0.1) | 1.1 | (0.2) | (39) | 9.8 | (1.5) | 7.9 | (0.4) |

| 5-10 | 1.7 | (0.1) | (943) | 17.5 | (0.5) | 20.9 | (0.2) | 0.7 | (0.1) | (70) | 17.7 | (1.9) | 22.0 | (0.6) |

| 10-20 | 0.7 | (0.0) | (431) | 8.0 | (0.4) | 24.2 | (0.2) | 0.4 | (0.1) | (37) | 9.3 | (1.5) | 20.0 | (0.6) |

| 20+ | 0.2 | (0.0) | (40) | 0.7 | (0.1) | 6.1 | (0.1) | 0.1 | (0.1) | (2) | 0.5 | (0.4) | 4.3 | (0.3) |

| Total | 2.0 | (0.0) | (5,375) | 100.0 | -- | 100.0 | -- | 0.9 | (0.0) | (396) | 100.0 | -- | 100.0 | -- |

| χ27 | 2002.6* | 104.2* | ||||||||||||

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test.

5,771 Regular Army soldiers had first onsets of major physical violence perpetration between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2009 out of the 975,057 Regular Army soldiers (821,807 men; 153,250 women) in active duty service over that time period.

n = number of soldiers with first founded accusations of non-familial major physical violent crime perpetration in the time interval represented by the row.

Percent of the total population person-months in the time interval represented by the row. Men had a total of 31,721,734 population person-months and women had a total of 5,181,659 population person-months.

Building the models

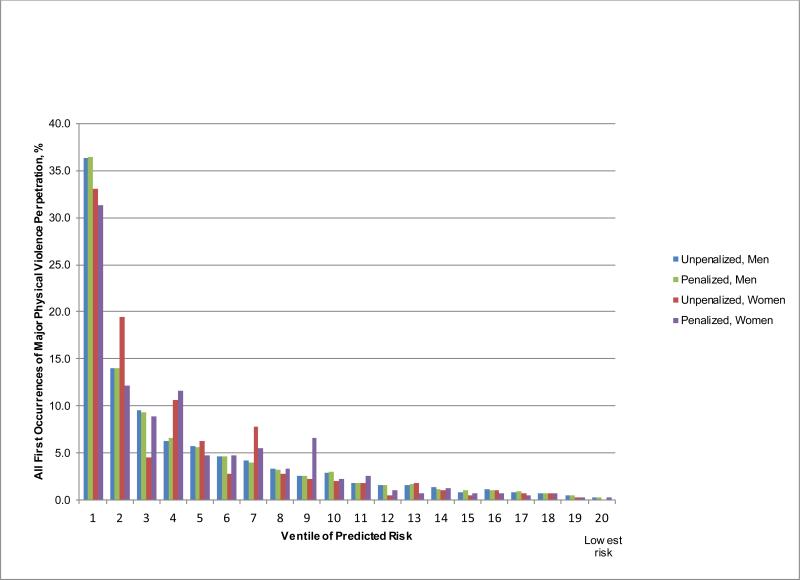

While the majority of the 456 HADS variables had significant (.05 level, two-sided tests) bivariate associations with the outcome among men (82.7%) and women (56.8%) (Appendix Tables 8-21), fewer (112 among men, 81 among women) entered the unrestricted stepwise model at the .05 level and fewer yet (24 among men, 15 among women) resulted in cross-validated improvements in overall model fit. AUC and the proportion of observed crimes committed by those in the top-ventile of predicted risk were similar whether or not the RF summary variable was added to the optimal cross-validated set of independent variables (Appendix Table 22), leading us not to include RF as part of the final models. Fit statistics were very similar in unpenalized and optimal penalized models (AUC=.81 in both models among men and .80-.82 among women; 36.2-36.4% of observed crime among men and 31.3-33.1% among women in those in with top 5% of predicted risk). (Figure 1) Incidence in the top-ventile of predicted risk (which, in the screening scale literature, would be referred to as the “positive predictive value” of the model at the 5% cut-point) was 14.7/1,000 person-years in both the unpenalized and penalized models among men (7.4 times the total-sample incidence) and 5.8-6.3/1,000 person-years among women (6.4-7.0 times the total-sample incidence).

Figure 1.

Proportion of observed crimes committed by Ventile of Predicted Risk Based on the Final Discrete-Time Survival Models for Men (24 predictors) and Women (15 predictors)a

a Ventiles are 20 groups of person-months of equal frequency dividing the total sample of person-months into equally sized groups defined by level of predicted perpetration risk

Coefficients in the optimal models

Five socio-demographics among men and one among women were significantly associated with elevated risk in the optimal models: young age, minority race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic Black the only significant socio-demographic variable among women), and less than at least some college education (Table 2). Seven Army career variables among men and six among women were also significant. Three with elevated risk were associated with early career stages: junior enlisted rank (E1-E4, men and women); intermediate enlisted rank (E5-6, women); and 0-10 years-in-service (men). Three other career-related variables discriminated among commands, with Forces Command (women; responsible for ground forces) and Area-based Component Commands (men and women; responsible for Army operations in specific regions of the world) having elevated risks and Training and Doctrine Command (men; responsible for recruiting and training) having low risk. The other four significant career-related variables associated with elevated risk were early age at enlistment (women), being an infantryman (only possible for men during the years of data collection), not being currently deployed (men and women), and recent demotion (men).

Table 2.

Coefficients (odds-ratios) from the final unpenalized survival models for first founded accusations of non-familial major physical violent crime perpetrationa

| Menb | Women | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | OR | (95% CI) | VIFc | % | (se) | OR | (95% CI) | VIFc | |

| 1. Socio-demographics | ||||||||||

| Age - 17-22 | 25.5 | (0.2) | 1.6* | (1.5-1.7) | 1.5 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Race/ethnicity - Non-Hispanic Black | 18.5 | (0.2) | 1.9* | (1.8-2.1) | 1.8 | 37.8 | (0.8) | 3.4* | (2.8-4.2) | 1.0 |

| Race/ethnicity - Any other than Non-Hispanic White | 34.8 | (0.2) | 1.3* | (1.2-1.4) | 1.8 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Education - Less than high school | 11.1 | (0.1) | 3.7* | (3.2-4.3) | 1.6 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Education - Completed high school but no college | 64.2 | (0. 2) | 2.3* | (2.0-2.6) | 1.6 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| II. Army career | ||||||||||

| Infantry occupation | 15.0 | (0.2) | 1.3* | (1.2-1.4) | 1.1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Previously or never deployed (i.e., not currently deployed) | 76.2 | (0.2) | 3.4* | (3.1-3.7) | 1.2 | 8 4.2 | (0.6) | 3.7* | (2.4-5.6) | 1.1 |

| Command TRADOC | 14.4 | (0.2) | 0.5* | (0.5-0.6) | 1.1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Command North/South America, Europe/Central/Africa, Pacific | 18.0 | (0.2) | 1.3* | (1.2-1.4) | 1.1 | 16.9 | (0.6) | 2.1* | (1.6-2.8) | 1.2 |

| Command FORSCOM | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 40.4 | (0.8) | 2.3* | (1.8-3.0) | 1.3 |

| Rank junior enlisted ( E1-E4) | 45.0 | (0.2) | 1.3* | (1.2-1.4) | 2.0 | 47.9 | (0.8) | 6.1* | (3.8-9.9) | 1.7 |

| Rank intermediate enlisted ( E5-E6) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 25.8 | (0.7) | 2.7* | (1.6-4.6) | 1.6 |

| Age of enlistment 17-21 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 61.7 | (0.8) | 1.7* | (1.3-2.2) | 1. 1 |

| Years in service 10 or less | 69.7 | (0.2) | 1.9* | (1.7-2.2) | 1.6 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Demotion in the past 12 months | 2.9 | (0.1) | 1.5* | (1.4-1.6) | 1.1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| III. Prior crime | ||||||||||

| Perpetrator of 1 type of crime (past 12 months) | 4.4 | (0.1) | 1.5* | (1.3-1.7) | 2.3 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Perpetrator of 2+ types of crime (past 12 months) | 1.5 | (0.1) | 2.2* | (1.9-2.5) | 1.5 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Perpetrator of minor physical violence (past 24 months) | 1.0 | (0.0) | 1.7* | (1.5-1.8) | 1.2 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Perpetrator of 1 + type of crime (past 24 months) | 9.0 | (0.1) | 1.8* | (1.6-2.1) | 2.8 | 7.0 | (0.4) | 2.3* | (1.8-2.9) | 1.1 |

| Perpetrator of verbal violence (past 12 months) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | <0.1 | (0.0) | 10.9* | (3.2-36.7) | 1.0 |

| Victim of any crime (past 12 months) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 4.5 | (0.3) | 2.5* | (1.9-3.3) | 1.0 |

| IV. Clinical factors | ||||||||||

| Suicide attempt in the past 12 months | 0.1 | (0.0) | 3.1* | (2.4-3.9) | 1.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Outpatient treatment for Conduct/ODD (past 12 months) | 0.1 | (0.0) | 2.7* | (2.0-3.6) | 1.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Outpatient treatment of any mental disorder (past 3 months)d | 14.0 | (0.2) | 1.1* | (1.0-1.1) | 1.4 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Outpatient treatment of stressor/adversity (past 12 months) | 9.4 | (0.1) | 1.3* | (1.2-1.4) | 1.3 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Outpatient treatment of alcohol disorder in past 12 months | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1.6 | (0.2) | 2.2* | (1.5-3.3) | 1.1 |

| Outpatient treatment of any mental disorder (past 12 months) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 34.8 | (0.7) | 1.8* | (1.4-2.2) | 1.0 |

| Outpatient treatment of drug-induced mental illness (past 12 months) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.2 | (0.1) | 7.4* | (3.5-15.5) | 1.0 |

| Any sedative-hypnotic prescription (past 12 months) | 4.6 | (0.1) | 1.4* | (1.3-1.6) | 1.1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 6+ days in the hospital for stressors/adversity (past 12 months) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | <0.1 | (0.0) | 21.1* | (5.6-79.2) | 1.0 |

| Hospitalization for depressive psychosis ( past 12 months) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.1 | (0.1) | 15.1* | (7.0-32.8) | 1.0 |

| V. Contextual factors | ||||||||||

| Median months in service of unit officers (Standardized)e | -- | (0.0) | 0.1* | (0.1-0.2) | 1.3 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Median months ever deployed of unit NCOs (E5-9) (Standardized)e | -- | (0.0) | 11.1* | (7.3-16.7) | 1.5 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; VIF, variance inflation factor; MPP, mixing parameter penalty; MOS, military occupational specialty; TRADOC, training and doctrine command; FORSCOM, forces command; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; WO, warrant officer; CO, commissioned officer; NCO, non-commissioned officer.

The analysis sample included all person-months with the outcome plus a probability sample of all other person-months in the population stratified by sex and marital status (total case-control sample of 201,121 person-months; 187,316 for men; 13,805 for women). All records in the control sample were weighted by the inverse of probability of selection. All independent variables shown here were significant at the .05 level (2-sided test).

One temporal control variable also stepped into the model for men (year of observation being in 2009) but is not shown here.

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for the coefficient associated with independent variable Xi in the above equation equals 1/(1-R2i), w here R2i is the coefficient of determination of a regression equation in w hich Xi is the dependent variable and all the other independent variables in the model are included as predictors of Xi. VIF ≥ 5.0 is typically considered an indicator of meaningful multicollinearity (Stine, 1995).

This was a categorical variable coded 0-4 (0=0 visits; 1=1-2 visits; 2=3-5 visits; 3=6-10 visits; 4=11 + visits). The percentage reported reflects that 14.0% of men had one or more days with outpatient visits in the past 3 months.

Pooled across unit officers/NCOs in the past 3 months. These variables were standardized to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1.

Four indicators of past 12-24 month criminality among men and three among women were associated with significantly elevated risk in the optimal models: perpetration of any crime (men and women); two or more types of crime (men); verbal violent crime (women; e.g., blackmail, intimidation); minor physical violent crime (men); and any crime victimization (women). Ten clinical factors (past 3-12 months) were also significant: any outpatient mental disorder treatment (women) and number of such visits (men); outpatient treatment of conduct/oppositional-defiant disorder (men), stress-related disorder (men), and alcohol or drug-induced disorder (women); inpatient treatment of major depression with psychosis or stressors/adversities (women); sedative-hypnotic prescriptions (men); and suicide attempts (men). Finally, two contextual variables were significant among men: there was an inverse association with tenure of unit officers (median time-in-service); and a positive association with deployment experience of noncommissioned officers (NCOs; median time-deployed).

Sensitivity analysis

To investigate the value of sex-specific models, we applied the coefficients from the unpenalized male model to the female sample and vice versa. Both AUC (.80-.79 for men and women, respectively) and the proportion of observed crimes committed by those in the topventile of predicted risk (31.6-27.7% for men and women, respectively) remained elevated, although somewhat lower than in the same-sex models, showing that core variables in the models are similar but not identical for men and women. Model-building was also repeated after excluding race-ethnicity as an eligible potential predictor. Results were quite similar to those in models that included race-ethnicity (Appendix Table 22).

As the models were designed to predict perpetration this month, further analysis was needed to evaluate prediction accuracy over longer time periods. We calculated the proportion of observed crimes committed by those in the top-ventile of predicted risk for all possible 1-month, 6-month, and 12-month follow-up periods from January 2004 through January 2009 and in 20-month (January 2004-August 2005; September 2005-April 2007; May 2007-January 2009) and 30-month (January 2004-June 2006; July 2006-January 2009) intervals. (February-December 2009 were excluded because we did not have 12-months of follow-up data after these months). The proportions were highest over 1-month periods (29.5-35.3%) (Table 3). This is to be expected given that some risk factors could have come into being only later (e.g., a new demotion), thereby leading to an increase in predicted risk with shorter time lags between predictors and the outcome. Nonetheless, the proportions remained elevated over 6-month (22.7-29.1%) and 12-month (18.3-24.1%) periods, documenting that most significant predictors are stable over these intervals of time. Proportions were also consistent across the five 20-month and 30-month time-intervals, indicating that model stability was quite good over the years 2004-2009.

Table 3.

Proportion of observed crimes committed by those in the top-ventile of predicted risk over 1-month, 6-month, and 12-month periods and across time-intervalsa

| Men |

Women |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-month | 6-month | 12-month | 1-month | 6-month | 12-month | |||||||

| Est | (se) | Est | (se) | Est | (se) | Est | (se) | Est | (se) | Est | (se) | |

| 1/04-1/09 | 35.3 | (0.7) | 29.1 | (0.3) | 24.1 | (0.2) | 29.5 | (2.5) | 22.7 | (0.9) | 18.3 | (0.6) |

| 1/04-8/05 | 33.9 | (1.3) | 28.9 | (0.5) | 24.6 | (0.4) | 32.6 | (4.8) | 22.6 | (1.8) | 18.4 | (1.2) |

| 9/05-4/07 | 34.4 | (1.2) | 29.4 | (0.5) | 24.8 | (0.3) | 30.8 | (4.5) | 26.0 | (1.7) | 19.2 | (1.1) |

| 5/07-1/09 | 37.2 | (1.2) | 29.2 | (0.5) | 23.0 | (0.3) | 26.3 | (3.8) | 20.1 | (1.4) | 17.3 | (1.0) |

| 1/04-6/06 | 35.1 | (1.1) | 29.4 | (0.4) | 24.7 | (0.3) | 32.1 | (4.0) | 24.1 | (1.5) | 18.8 | (1.0) |

| 7/06-1/09 | 35.5 | (0.9) | 28.9 | (0.4) | 23.6 | (0.3) | 27.7 | (3.2) | 21.7 | (1.2) | 17.9 | (0.8) |

Estimates are based on the predicted probabilities from the final total sample penalized models. February-December 2009 were excluded because we did not have 12-months of follow-up data after these months

Although time-in-service was strongly related to risk of being accused of committing the outcome, the fact that RF did not improve model fit meant that no interactions were found between time-in-service and other independent variables. However, this might have been because we lacked adequate statistical power to detect these interactions due to the high proportion of the outcome occurring in the early years of service. We evaluated this possibility by examining the proportion of observed crimes committed by those in the top-ventile of predicted risk within subgroups defined by time-in-service. (Table 4) Unsurprisingly, the proportion of soldiers in the top-ventile of predicted risk varied inversely with time-in-service among both men and women (χ27=2310.4-94.0, p<.001). However, when cut-points were recalibrated to focus on the 5% of soldiers at highest predicted risk within each time-in-service subsample, the association between time-in-service and the proportion of observed crimes committed by those in the top-ventile of predicted risk became insignificant (31.2% among men, χ27=8.0, p=.33; 27.0% among women, χ26=8.2, p=.23).

Table 4.

Incidence/1,000 person-years and the proportion of observed crimes committed by those in the top-ventile of predicted risk within time-in-service subsamples by sex and time-in-service among Regular Army soldiers in the Army STARRS 2004-2009 Historical Administrative Data Systems (HADS)a

| Overall ventiles with highest predicted risk |

Within time-in-service ventiles with highest predicted riskb |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence/1,000 person-years | Within-row predicted risk | Proportion of person-months in top-ventile | Incidence/1,000 person-years | Within-row predicted risk | ||||||

| Years-in- service | Est | (se) | Est | (se) | % | (se) | Est | (se) | Est | (se) |

| I. Men | ||||||||||

| 0-1 | 15.5 | (1.2) | 32.1 | (1.6) | 5.3 | (0.3) | 15.3 | (1.2) | 29.8 | (1.6) |

| 1-2 | 16.5 | (0.9) | 47.5 | (1.5) | 10.9 | (0.4) | 24.7 | (1.9) | 32.8 | (1.4) |

| 2-3 | 15.6 | (1.0) | 47.1 | (1.6) | 10.3 | (0.4) | 22.2 | (1.8) | 32.7 | (1.5) |

| 3-4 | 15.2 | (1.1) | 42.2 | (1.8) | 8.7 | (0.4) | 19.7 | (1.8) | 31.4 | (1.7) |

| 4-5 | 12.6 | (1.4) | 36.1 | (2.5) | 6.3 | (0.4) | 15.1 | (1.8) | 34.0 | (2.4) |

| 5-10 | 12.0 | (1.0) | 26.7 | (1.4) | 3.8 | (0.2) | 10.3 | (0.8) | 30.0 | (1.5) |

| 10-20 | 11.6 | (2.6) | 7.7 | (1.3) | 0.4 | (0.1) | 3.9 | (0.4) | 28.5 | (2.2) |

| 20+ | 5.3 | (4.2) | 5.0 | (3.5) | 0.2 | (0.1) | 1.1 | (0.4) | 22.5 | (6.6) |

| Total | 14.7 | (0.4) | 36.4 | (0.7) | 5.0 | (0.1) | 12.7 | (0.4) | 31.2 | (0.6) |

| χ27 | 17.3* | 434.4* | 2309.4* | 412.1* | 8.0 | |||||

| II. Women | ||||||||||

| 0-1 | 11.4 | (4.0) | 37.5 | (7.0) | 2.6 | (0.7) | 7.4 | (2.2) | 43.8 | (7.2) |

| 1-2 | 5.7 | (1.3) | 37.2 | (5.2) | 10.8 | (1.4) | 7.3 | (2.2) | 22.1 | (4.5) |

| 2-3 | 4.9 | (1.3) | 31.3 | (5.7) | 9.4 | (1.4) | 6.0 | (2.0) | 22.4 | (5.1) |

| 3-4 | 4.2 | (1.5) | 25.5 | (6.4) | 7.0 | (1.3) | 4.4 | (1.6) | 23.4 | (6.2) |

| 4-5 | 5.4 | (1.9) | 33.3 | (7.6) | 7.1 | (1.4) | 4.5 | (1.7) | 25.6 | (7.0) |

| 5-10 | 6.0 | (1.7) | 30.0 | (5.5) | 3.7 | (0.6) | 4.8 | (1.3) | 31.4 | (5.6) |

| 10+c | 5.4 | (2.6) | 18.0 | (6.2) | 1.2 | (0.4) | 1.8 | (0.6) | 23.1 | (6.8) |

| Total | 5.8 | (0.7) | 31.3 | (2.3) | 5.0 | (0.3) | 4.8 | (0.6) | 27.0 | (2.2) |

| χ26 | 4.6 | 7.2 | 94.0* | 14.0* | 8.2 | |||||

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test.

Estimates are based on the coefficients from the total sample penalized models (MPP=0.5 for men; MPP=0.1 for women)

Ventiles were re-classified independently within each time in service group so the top-ventile of predicted risk includes 5% of the person-months within each time in service category

There were only two person-months coded yes for a first occurrence of major physical violence perpetration among women with 20+ years-in-service. One of the two had a predicted probability in the top-ventile, resulting an unstable standardized rate of perpetration among women with 20+ years-in-service (2,400/1,000 PY). We consequently collapsed the 10-20 and 20+ years-in-service groups to form a 10+ years-in-service.

Validation of the model in the Army STARRS 2011-2013 survey sample

The coefficients estimated in the 2004-2009 HADS were applied to the sample of soldiers who participated in Army STARRS surveys in 2011-2011 (n=43,248) and were followed administratively through the end of 2013 (10,165,562 person-months). Men and women were combined because of the small number of instances of the outcome in this sample (n=16). AUC was .77 and the proportion of observed crimes committed by those in the top-ventile of predicted risk was 50.5%.

DISCUSSION

The administrative data used here, although broad in scope, were limited because they did not include indicators of some significant predictors found in previous studies (e.g., personality traits, social networks, early life experiences), because they had more missing and inconsistent values than would data collected for research purposes, and because they excluded perpetrators who eluded authorities. Within the context of these limitations, we showed that models could be developed with quite stable prediction accuracy across subgroups within the 2004-2009 training dataset and provisionally validated in an independent 2011-2013 dataset. Caution is needed in the latter regard, though, as the validation sample was small and a more complete validation is needed once HADS data become available for a more recent time period. It would be premature to use the tool in practice prior to a more thorough validation.

It is also important not to over-interpret the specific variables in our final models, as the stepwise selection method maximized overall prediction accuracy at the expense of individual coefficient accuracy. Three general observations about the variables in the final models are nonetheless noteworthy. First, these variables were highly consistent with previous military research in showing that violence was associated with young age and low rank, low socioeconomic and minority status, prior crime involvement, and mental disorders (Elbogen et al., 2014a, Elbogen et al., 2012, Elbogen et al., 2014b, Gallaway et al., 2012, Hellmuth et al., 2012, MacManus et al., 2012a, MacManus et al., 2013, Sullivan and Elbogen, 2014).

Second, our finding that never-deployed and previously-deployed soldiers had comparably elevated violent crime risk is striking given that recent research has suggested that combat exposure leads to increased violence among soldiers returning from deployment (MacManus et al., 2015). That the RF analysis failing to find evidence of meaningful interactions means that no evidence was found for differences in the strength of associations of predictors among the previously-deployed and never-deployed versus the currently-deployed. We also carried out post hoc analyses to include information on history and recency of deployment and the conjunction of combat arms occupation with deployment among the independent variables, but none of these was significantly associated with the outcome (Appendix Table 23). These findings suggest that the significantly elevated rates of violence found in previous research among soldiers with a history of combat deployment are explained by other variables in our model. It would be useful to investigate this matter formally in future studies by beginning with the gross associations of deployment with violence and determining which of the variables in our final models explained those gross associations.

Third, the opposite-sign coefficients associated with unit leader tenure/experiences are noteworthy. The distinction between officers and NCOs is artifactual (illustrating the caution noted above against over-interpreting the coefficients associated with specific significant predictors), as analysis of bivariate associations showed that time-in-service of both NCOs and officers was negatively associated with unit member violence, while time-deployed of both NCOs and officers was positively associated with unit member violence. This further analysis also showed that the opposite-sign bivariate associations were quite stable over time and existed among women as well as men (Appendix Table 24). To put the magnitudes of these associations in perspective, a policy simulation based on the provisional assumption that the coefficients represent causal effects suggested that randomly assigning soldiers to units led by officers with time-in-service one standard deviation above the Army-wide mean and by NCOs with time-deployed one standard deviation below the Army-wide mean would decrease incidence of the crimes considered here by nearly 40%. Of course, it is unclear if a causal interpretation is appropriate or, if so, what underlying mechanisms might account for these associations. Suggestions exist in the literature, such as that longer tenure of unit leaders is associated with both improved unit discipline (Shamir et al., 2000) and reduced aggression of unit members (Bliese et al., 2002), that the disciplinary climate created by unit leaders influences violence rates within units (Millikan et al., 2012), and that unit leaders who experience repeated deployments might become more tolerant of violence (Parmak et al., 2012). But systematic multivariate analysis and subsequent experimentation would be needed to determine which of these or other processes might account for the associations found here between unit leader tenure/experiences and unit member violent crimes.

It is interesting to compare the accuracy of our models with the accuracy of violence risk assessment tools developed in forensic and inpatient settings, even though the populations in these other studies are so different from the population considered here that such comparisons are no more than suggestive. Unlike our administrative data tool, these existing risk assessment tools are usually quite labor-intensive to administer in that they require clinicians to make in-depth assessments. Prediction accuracy is typically evaluated by calculating AUC. A recent comprehensive review of the 17 tools of this sort (including six that were developed specifically to predict sexual violence and one developed to predict domestic violence) evaluated in multiple settings found that 11 had mean AUC below .70 and the others AUC in the range .70-.79, with the highest AUC among instruments used in at least 5 studies being .73 (Whittington et al., 2013). Our models, in comparison, had AUC of .80-.82 in the training dataset and .77 in the validation dataset. These levels of prediction accuracy were achieved based entirely on administrative predictors available on an ongoing basis for all soldiers. Furthermore, unlike typical violence risk assessment tools, which focus on individual differences in risk over a single risk period (e.g., risk of committing a violent act in the next 12 months), our approach allows us to look not only as between-person variation in risk but also at within-person variation in risk over time (i.e., detection of critical periods of risk for individual soldiers).

The U.S. Army does not currently use actuarial methods to identify soldiers at high risk of committing violent crimes. However, the high AUC and high proportion of observed crimes committed by those in the top-ventile of predicted risk in our models raise the possibility that our models, if they are validated in future studies that go beyond the provisional validation reported here, might be useful for determining which soldiers should receive more intensive risk evaluations or interventions (Douglas et al., 2013, Naeem et al., 2009, Shea et al., 2013). It is important to recognize, though, that the crimes considered here are uncommon even in the 5% of soldiers classified as being at high risk. This means that targeted preventive interventions would only be cost-effective if (i) the value of preventing even a single case of violent crime was determined to be high, (ii) the intervention was inexpensive, and/or (iii) the intervention was effective in preventing not only violent crime but also other adverse outcomes associated with high violence risk (e.g., depression, substance abuse, self-harm). Competing risks would have to be considered under each scenario. Although evaluation of these scenarios is outside of the scope of the current report, such an evaluation would have to be a central focus of any future efforts to determine the feasibility and desirability of using our models to target preventive interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The data analyzed in this report were collected as part of the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Army STARRS was sponsored by the Department of the Army and funded under cooperative agreement number U01MH087981 with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health (NIH/NIMH). This research was conducted by Harvard Medical School and is funded by the Department of Defense, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Defense for Health Affairs, Defense Health Program (OASD/HA), awarded and administered by the U.S. Army Medical Research & Materiel Command (USAMRMC), at Fort Detrick, MD, under Contract Number: (Award # W81XWH-12-2-0113).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Dr. Stein has been a consultant for Care Management Technologies, received payment for his editorial work from UpToDate and Depression and Anxiety, and had research support for pharmacological imaging studies from Janssen. In the past three years, Dr. Kessler has been a consultant for Hoffman-La Roche, Inc., Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, and Sonofi-Aventis Groupe. Dr. Kessler has served on advisory boards for Mensante Corporation, Plus One Health Management, Lake Nona Institute, and U.S. Preventive Medicine. Dr. Kessler is a co-owner of DataStat, Inc. Dr. Monahan is a co-owner of the Classification of Violence Risk (COVR), Inc. The remaining authors declare nothing to disclose.

Ethical standards: The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Disclaimer: The views, opinions and/or findings contained in this research are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, Department of Health and Human Services, or NIMH and should not be construed as an official DoD/Army position, policy or decision unless so designated by other documentation. No official endorsement should be made.

REFERENCES

- Anderssen E, Dyrstad K, Westad F, Martens H. Reducing over-optimism in variable selection by cross-model validation. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems. 2006;84:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Army Suicide Prevention Task Force . Army health promotion, risk reduction, suicide prevention. Department of Defense; Washington, DC: 2010. [March 1, 2015]. ( http://www.army.mil/article/42934/) [Google Scholar]

- Berk RA. Statistical learning from a regression perspective. Springer Verlag; New York, NY.: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Berk RA. The role of race in forecasts of violent crime. Race and Social Problems. 2009;1:231–242. [Google Scholar]

- Berk RA, Bleich J. Forecasts of violence to inform sentencing decisions. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2014;30:79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bliese PD, Halverson RR, Schriesheim CA. Benchmarking multi-level methods in leadership: the articles, the model and the data set. Leadership Quarterly. 2002;13:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense Instruction Deparment of Defense, editor. [March 1, 2015];DoD Workplace Violence Prevention and Response Policy. 2014 ( http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/143806p.pdf).

- Department of the US Army . Army 2020: Generating Health & Discipline in the Force ahead of the Strategic Reset. US Army; Washington, DC: 2012. [March 1, 2015]. ( http://www.patriotoutreach.org/docs/army_gold_book.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Douglas KS, Hart SD, Webster CD, Belfrage H. HCR-20V3 Assessing Risk for Violence-User Guide. Mental Health, Law, and Policy Institute, Simon Fraser University; Burnaby, BC, Canada: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Cueva M, Wagner HR, Sreenivasan S, Brancu M, Beckham JC, Van Male L. Screening for violence risk in military veterans: predictive validity of a brief clinical tool. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2014a;171:749–757. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Fuller S, Johnson SC, Brooks S, Kinneer P, Calhoun PS, Beckham JC. Improving risk assessment of violence among military veterans: an evidence-based approach for clinical decision-making. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010a;30:595–607. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Johnson SC, Newton VM, Fuller S, Wagner HR, Beckham JC. Self-report and longitudinal predictors of violence in Iraq and Afghanistan war era veterans. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2013;201:872–876. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182a6e76b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Johnson SC, Wagner HR, Newton VM, Timko C, Vasterling JJ, Beckham JC. Protective factors and risk modification of violence in Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2012;73:e767–e773. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Johnson SC, Wagner HR, Sullivan C, Taft CT, Beckham JC. Violent behaviour and post-traumatic stress disorder in US Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. The British Journal of Psychiatry: the Journal of Mental Science. 2014b;204:368–375. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.134627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Fuller SR, Calhoun PS, Kinneer PM, Beckham JC. Correlates of anger and hostility in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010b;167:1051–1058. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09050739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Singh JP, Doll H, Grann M. Use of risk assessment instruments to predict violence and antisocial behaviour in 73 samples involving 24,827 people: systematic review and meta-analysis. [March 1, 2015];British Medical Journal. 2012 345:e4692. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4692. ( http://www.bmj.com/content/345/bmj.e4692.long) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fort Lee Human Resources . Prevention of Workplace Violence Program. U.S. Army; Fort Lee, Virginia: 2014. [March 1, 2015]. ( http://www.lee.army.mil/hrd/prevention.of.workplace.violence.program.aspx). [Google Scholar]

- Foster EM, Jones D. Can a costly intervention be cost-effective?: An analysis of violence prevention. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:1284–1291. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. Journal of Statistical Software. 2010;33:1–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallaway MS, Fink DS, Millikan AM, Bell MR. Factors associated with physical aggression among US Army soldiers. Aggressive Behavior. 2012;38:357–367. doi: 10.1002/ab.21436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golubnitschaja O, Costigliola V. General report & recommendations in predictive, preventive and personalised medicine 2012: white paper of the European Association for Predictive, Preventive and Personalised Medicine. The EPMA Journal. 2012;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1878-5085-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmuth JC, Stappenbeck CA, Hoerster KD, Jakupcak M. Modeling PTSD symptom clusters, alcohol misuse, anger, and depression as they relate to aggression and suicidality in returning U.S. veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25:527–534. doi: 10.1002/jts.21732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins N, Watts D, Bindman J, Slade M, Thornicroft G. Assessing violence risk in general adult psychiatry. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2005;29:131–133. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Returning Home fom Iraq and Afghanistan: Preliminary Assessment of Readjustment Needs of Veterans, Service Members, and their Families. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC.: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Conybeare D, Phelps L, Hunt S, Holmes HA, Felker B, Klevens M, McFall ME. Anger, hostility, and aggression among Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans reporting PTSD and subthreshold PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:945–954. doi: 10.1002/jts.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, Gebler N, Naifeh JA, Nock MK, Sampson NA, Schoenbaum M, Zaslavsky AM, Stein MB, Ursano RJ, Heeringa SG. Design of the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2013;22:267–275. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Warner CH, Ivany C, Petukhova MV, Rose S, Bromet EJ, Brown M, 3rd, Cai T, Colpe LJ, Cox KL, Fullerton CS, Gilman SE, Gruber MJ, Heeringa SG, Lewandowski-Romps L, Li J, Millikan-Bell AM, Naifeh JA, Nock MK, Rosellini AJ, Sampson NA, Schoenbaum M, Stein MB, Wessely S, Zaslavsky AM, Ursano RJ. Predicting suicides after psychiatric hospitalization in US Army soldiers: the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:49–57. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WD, Cotting DI, Thomas JL, Cox AL, McGurk D, Vo AH, Castro CA, Hoge CW. Post-combat invincibility: violent combat experiences are associated with increased risk-taking propensity following deployment. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42:1112–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohavi R. Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Vol. 2. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.; Montreal, Quebec, Canada: 1995. A study of cross-validation and bootstrap for accuracy estimation and model selection. pp. 1137–1143. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC. Events per person-time (incidence rate): a misleading statistic? Statistics in Medicine. 2009;28:1028–1039. doi: 10.1002/sim.3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc MM, Kelloway EK. Predictors and outcomes of workplace violence and aggression. The Journal of Applied Psychology. 2002;87:444–453. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw A, Wiener M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News. 2002;2:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- MacManus D, Dean K, Al Bakir M, Iversen AC, Hull L, Fahy T, Wessely S, Fear NT. Violent behaviour in U.K. military personnel returning home after deployment. Psychological Medicine. 2012a;42:1663–1673. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacManus D, Dean K, Iversen AC, Hull L, Jones N, Fahy T, Wessely S, Fear NT. Impact of pre-enlistment antisocial behaviour on behavioural outcomes among U.K. military personnel. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2012b;47:1353–1358. doi: 10.1007/s00127-011-0443-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacManus D, Dean K, Jones M, Rona RJ, Greenberg N, Hull L, Fahy T, Wessely S, Fear NT. Violent offending by UK military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: a data linkage cohort study. The Lancet. 2013;381:907–917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacManus D, Rona R, Dickson H, Somaini G, Fear N, Wessely S. Aggressive and violent behavior among military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: prevalence and link with deployment and combat exposure. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2015;37:196–212. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxu006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall AD, Panuzio J, Taft CT. Intimate partner violence among military veterans and active duty servicemen. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:862–876. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloy JR, White SG, Hart S. Workplace assessment of targeted violence risk: the development and reliability of the WAVR-21. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 2013;58:1353–1358. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.12196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millikan AM, Bell MR, Gallaway MS, Lagana MT, Cox AL, Sweda MG. An epidemiologic investigation of homicides at Fort Carson, Colorado: summary of findings. Military Medicine. 2012;177:404–411. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-11-00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadkhani P, Forouzan AS, Khooshabi KS, Assari S, Lankarani MM. Are the predictors of sexual violence the same as those of nonsexual violence? A gender analysis. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2009;6:2215–2223. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan J, Skeem JL. Risk redux: the resurgence of risk assessment in criminal sanctioning. Federal Sentencing Reporter. 2014;26:158–166. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Robbins PC, Appelbaum P, Banks S, Grisso T, Heilbrun K, Mulvey EP, Roth L, Silver E. An actuarial model of violence risk assessment for persons with mental disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:810–815. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.7.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeem F, Clarke I, Kingdon D. A randomized controlled trial to assess an anger management group programme. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist. 2009;2:20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Parmak M, Euwema MC, Mylle JJC. Changes in sensation seeking and need for structure before and after a combat deployment. Military Psychology. 2012;24:551–564. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc . SAS/STATR Software. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schlesselman JJ. Case-control Studies: Design, Conduct, Analysis. Oxford University Press; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Shamir B, Brainin E, Zakay E, Popper M. Perceived combat readiness as collective efficacy: individual-and group-level analysis. Military Psychology. 2000;12:105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Shea MT, Lambert J, Reddy MK. A randomized pilot study of anger treatment for Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2013;51:607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, Kennealy P, et al. Psychosis Uncommonly and Inconsistently Precedes Violence Among High-Risk Individuals. [August 1, 2015];Clinical Psychological Science. 2015 ( http://cpx.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/04/23/2167702615575879.abstract)

- Skeem JL, Monahan J. Current directions in violence risk assessment. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2011;20:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman HJ, Monahan J, et al. Gun Violence and Victimization of Strangers by Persons With a Mental Illness: Data From the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. Psychiatric services; 2015. [August 1, 2015]. ( http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/appi.ps.201400512?journalCode=ps). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine RA. Graphical interpretation of variance inflation factors. The American Statistician. 1995;49:53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan CP, Elbogen EB. PTSD symptoms and family versus stranger violence in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Law and Human Behavior. 2014;38:1–9. doi: 10.1037/lhb0000035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundin J, Herrell RK, Hoge CW, Fear NT, Adler AB, Greenberg N, Riviere LA, Thomas JL, Wessely S, Bliese PD. Mental health outcomes in US and UK military personnel returning from Iraq. The British Journal of Psychiatry: the Journal of Mental Science. 2014;204:200–207. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.129569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svetnik V, Liaw A, Tong C, Culberson JC, Sheridan RP, Feuston BP. Random Forest: A Classification and Regression Tool for Compound Classification and QSAR Modeling. Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences. 2003;43:1947–1958. doi: 10.1021/ci034160g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Riviere LA, McGurk D, Castro CA, Hoge CW. Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active component and National Guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:614–623. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Justice . National Corrections Reporting Program, 2009 (ICPSR 30799) National Achive of Criminal Justice Data; Ann Arbor, MI: 2009. [March 1, 2015]. ( http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NACJD/studies/30799?archive=NACJD&per mit%5B0%5D=AVAILABLE&q=30799&x=0&y=0). [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Kessler RC, Schoenbaum M, Stein MB. The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Psychiatry. 2014;77:107–119. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2014.77.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington R, Hockenhull JC, McGuire J, Leitner M, Barr W, Cherry MG, Flentje R, Quinn B, Dundar Y, Dickson R. A systematic review of risk assessment strategies for populations at high risk of engaging in violent behaviour: update 2002-8. Health Technology Assessment. 2013;17:i–xiv. 1–128. doi: 10.3310/hta17500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett JB, Singer JD. Investigating onset, cessation, relapse, and recovery: why you should, and how you can, use discrete-time survival analysis to examine event occurrence. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:952–965. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H, Hastie T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B. 2005;67:301–320. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.