Abstract

The increased use of tissue expander in the past decades and its potential market values in near future give enough reasons to sum up the consequences of tissue expansion. Furthermore, the patients have the right to know underlying mechanisms of adaptation of inserted biomimetic, its bioinspired materials and probable complications. The mechanical strains during tissue expansion are related to several biological phenomena. Tissue remodeling during the expansion is highly regulated and depends on the signal transduction. Any alteration may lead to tumor formation, necrosis and/or apoptosis. In this review, stretch induced cell proliferation, apoptosis, the roles of growth factors, stretch induced ion channels, and roles of second messengers are organized. It is expected that readers from any background can understand and make a decision about tissue expansion.

Keywords: tissue expansion, growth factors, focal adhesion complex, apoptosis, ion channels, secondary messengers

Introduction

Since the first utilization in 1957 (Neumann, 1957), the use of tissue expansions have become widespread in maxillary and craniofacial surgery (Kobus, 2007), burn scar excision (Hafezi et al., 2009), breast reconstruction following mastectomy (Lohsiriwat et al., 2013), ophthalmology (Hou et al., 2012), management of omphalocele (Clifton et al., 2011), nasal reconstruction (Kheradmand et al., 2011), scalp alopecia (Guzey et al., 2015) and other deformities in plastic reconstructive surgery (Motamed et al., 2008; Laurence et al., 2012; Santiago et al., 2012). Tissue expander generates new tissues, by exploiting the viscoelastic properties of the skin and adjusted histological changes which follows the principle of the controlled mechanical skin overstretch (Argenta, 1984; Pamplona et al., 2014). It involves the insertion of a biomimetic and bioinspired material (i.e., hydrogel tissue expander) adjacent to a wound or defect that needs to be resurfaced (Motamed et al., 2008; Swan et al., 2012). The expanded tissue can then be used to resurface a defect or incorporate permanent prostheses (Kasper et al., 2012; Swan et al., 2012).

Nevertheless, tissue expansion for the reconstructive surgery are also associated with a variety of complications (Adler et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2011). Swan et al. (2012) observed mucoperiosteal ulceration while using uncoated self-inflating anisotropic hydrogel tissue expander in the porcine hard palate. Minor side effects on skin histology and circulation resulted in skin stretching with staples or hypodermic needles, thus proving the Pavletic device to be non-feasible in primary wound closure (Tsioli et al., 2015). Incidence of infection, being the most common complication (Huang et al., 2011), has witnessed a total of 16 cases out of 215 children who underwent reconstruction with tissue expanders (Adler et al., 2009). However, the pivotal concern is to ensure normal tissue patterning and prevent tumor or scar formation (Huang and Ingber, 1999; Aarabi et al., 2007).

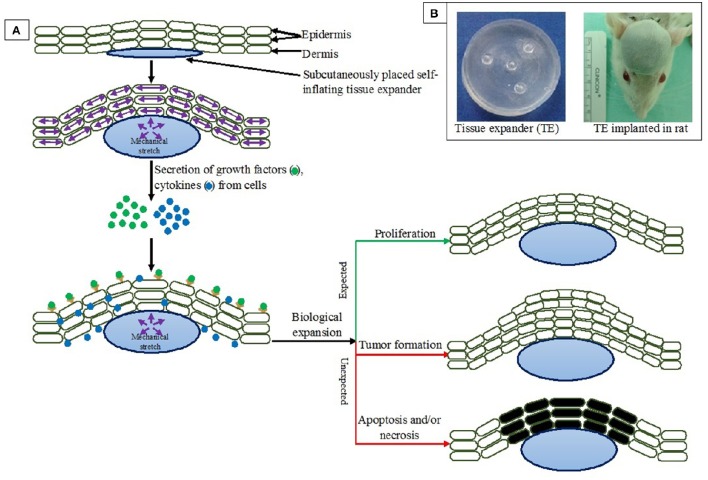

Recent studies revealed that rapid changes in extension, alignment, and collagen adapt to mechanical expansion (i.e., stretch or strain). Both elastin and collagen realign in a parallel fashion in response to stretch and/or expansion (Verhaegen et al., 2012; Tsioli et al., 2015), and the elongation occurs to the direction of stretching (Figure 1). Mechanical stretch on tissue is related to several physiological phenomena such as cellular growth enhancement and/or expansion with a significantly higher vascularity of expanded tissue (Yano et al., 2004). Strain beyond physiological limit may lead to alteration of cell function such as tumor formation, necrosis and/or apoptosis (Chen et al., 1997; Huang and Ingber, 1999; Wernig et al., 2003; Knies et al., 2006). Hence lies the clinical implications of tissue expansion (Swenson, 2014; Kwon et al., 2016).

Figure 1.

(A) Effects of tissue expansion on surrounding tissues. (B) Tissue expander before implantation and implanted in rat. Pictures taken from ongoing research in author's lab.

In physiological condition, tissue development and remodeling are highly regulated. A number of studies have focused on the cellular and molecular mechanisms (such as integrated network of cascades, implicating growth factors, cytoskeleton, protein kinase family, synthesis of DNA, expression of gene) leading to the increase of skin surface area (Plenz et al., 1998; Takei et al., 1998; Skutek et al., 2003; Knies et al., 2006; Jaalouk and Lammerding, 2009; Wong et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2015). Under mechanical stress, the cell phenotype and the nature of the physical stimuli determine which signal transduction pathways are activated during tissue expansion (Hsieh and Nguyen, 2005). This review, will focus the reports of molecular events of skin-derived cells in response to mechanical strain. The response of cells to mechanical stretch, the roles of growth factors, effects on extracellular matrix, cell membrane, and stretch induced ion channels, roles of second messengers, and cellular interactions will be organized from the extracellular to intracellular pathways with future perspectives in the conclusion.

Response of cells to mechanical stretch

The viscoelastic properties of skin to increase surface area in response to forces are the basic biology of tissue expansion (Bascom and Wax, 2002). The external forces are transmitted through the multi-layered skin which consists of epidermis connected to the dermis and the underlying subcutaneous tissues (Schwartz and DeSimone, 2008). The morphological and physiological consequences of tissue expansion on various layers of skin and other cellular and muscular components are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Responses of tissues to expansion.

| Tissues | Effects observed | References |

|---|---|---|

| Epidermis |

|

Austad et al., 1982; Vander Kolk et al., 1987; van Rappard et al., 1988; Silver et al., 1992. |

| Dermis |

|

Austad et al., 1982; Pasyk et al., 1988; Johnson et al., 1993. |

| Fat |

|

Leighton et al., 1988; Pasyk et al., 1988; Takei et al., 1998. |

| Muscle |

|

Pasyk et al., 1982; Sasaki and Pang, 1984; Stark et al., 1987; Johnson et al., 1993. |

| Capsule |

|

Austad et al., 1982; Johnson et al., 1993. |

| Blood vessels |

|

Sasaki and Pang, 1984; Stark et al., 1987; Saxby, 1988. |

| Nerve |

|

Swenson, 2014. |

| Bone |

|

Antonyshyn et al., 1988; Moelleken et al., 1990; Johnson et al., 1993. |

| Vascular plexus |

|

Saxby, 1988; Nikkhah et al., 2015. |

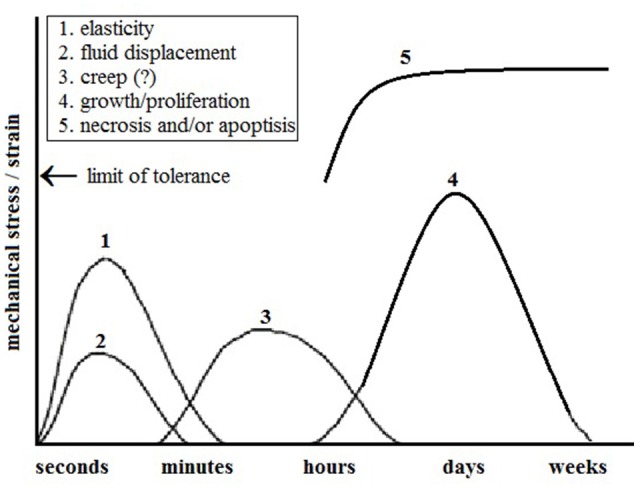

Numerous researchers have linked the mechanisms that lead to an increased length with skin's elasticity (Kenedi et al., 1975; Bader and Bowker, 1983; Larrabee Jr and Sutton, 1986). Gibson et al. (1965) associated the increase in skin length with the interstitial displacement of fluids and skin's creep behavior. Austad et al. (1982) reported that the increased length was as a result of cellular proliferation. Siegert et al. (1993) simplified these findings relating the strain, time and mechanism of skin expansion as shown in Figure 2. Because of its elasticity, the skin expands practically without temporal delay after expansion pressure is exerted. Interstitial displacement of fluids can be seen (in oedema) after skin expansion. Larrabee Jr et al. (1986), Gibson et al. (1965) and Wilhelmi et al. (1998) suggested that the biological creep (i.e., the generation of new tissue) is due to the chronic stretching forces. It is also most likely that similar events such as interstitial fluid displacement and elasticity beyond the tolerance limit of the tissue might induce necrosis and/or apoptosis of the tissue (Linder-Ganz and Gefen, 2004).

Figure 2.

Physiological and cellular response of skin to mechanical stress. It is most likely that mechanical stress beyond the limit of tolerance of elasticity might induce necrosis and/or apoptosis at the cellular level (Modified from Siegert et al., 1993).

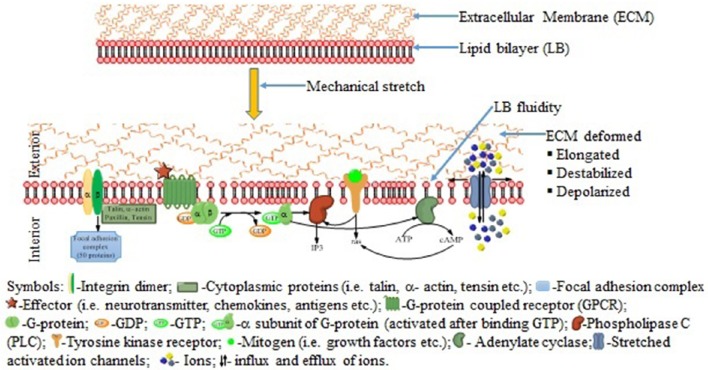

Cell stretching, in some contexts causes apoptosis, and in others promotes cell proliferation (Takei et al., 1998; Skutek et al., 2003). Similarly, apoptosis and proliferation pathways share many common elements, and they converge and influence each other at different levels (Wernig et al., 2003). Application of mechanical stretch (stimulus) activates mechanosensitive ion channels, G-protein coupled receptors, protein kinases, integrin-matrix interactions and other membrane-associated signal-transduction molecules to convert physical cues to biologic responses (Schwartz and DeSimone, 2008; Jaalouk and Lammerding, 2009) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Possible signaling pathways activated in response to mechanical stretch. Upon application of forces, extracellular matrix deformed and the plasma membrane altered resulting activation of the ion channel and activate the integrins, G-protein coupled receptors, tyrosine kinase receptors and others membrane bound signaling pathways.

Stretch induced proliferation

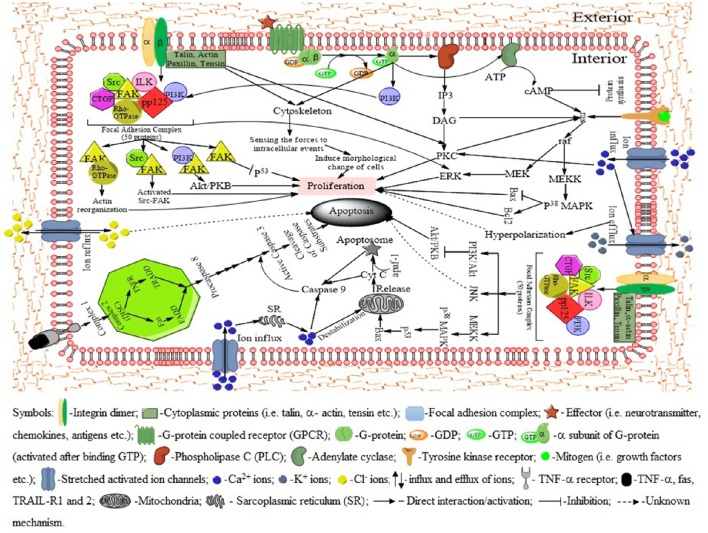

In response to mechanical stretch, cells of the cutaneous tissues, such as fibroblasts, receive the signals and prepare to proliferate (Silver et al., 2003). The extracellular matrix (ECM) plays a central role in strain-induced cell proliferation (Hynes, 2002). The extracellular forces transmitted through the ECM leading to the deformation of the matrix, followed by alteration of plasma membrane and adhesion complexes (Chien, 2007). The transmembrane protein integrin communicate with both extracellular matrix and cytoplasmic proteins such as talin, paxilin, and vinculin. Integrins also sense the physical properties of the ECM and organize the cytoskeleton accordingly (Zamir and Geiger, 2001). Binding of talin to the integrin cytoplasmic tail induce a conformational change from an inactivated to an activated state with an increase affinity for the ECM (Tadokoro et al., 2003). Upon the activation of integrins, the β subunit complexes with numerous structural and signaling proteins to form a focal adhesion complex (FAC) to provide both the physical link between integrin-adhesion receptors and the actin cytoskeleton, as well as sites of signal transduction into the cell interior (Carragher and Frame, 2004; Wozniak et al., 2004). The activated FAC then activate signal transduction pathways that co-ordinate cell proliferation (Figure 4). Hence it is well evident that a number of growth factors in ECM regulate cell proliferation (Singh et al., 2009; Bush and Pins, 2010).

Figure 4.

Signaling pathways activated by mechanical stretch leading to either cell proliferation or apoptosis. The integrins organize the cytoskeleton according the physical properties of the extracellular matrix (ECM). The membrane bound ion channels, G-protein, tyrosine kinase receptor and other molecules activate specific pathways to proliferation. In case of apoptosis, receptor-like molecules such as integrins, focal adhesion proteins become activated and these molecules in turn activate a limited number of protein kinase pathways (p38 MAPK, PI3K/Akt, JNK etc.), which amplify the signal and activate enzymes (caspases) that promote apoptosis. Activation of death receptors (Fas and/or TNFR) leads to the formation of a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC), resulting in the cleavage of procaspase-8 to its active form. Caspase-8 in turn activates downstream proteins that lead to apoptosis. Bax, induces the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria and promotes apoptosis. Moreover, cytochrome c complexes with apaf-1 and procaspase-9 to form an apoptosome. This leads to the activation of caspase-9, which in turn activates effector caspases (3, 6, and 7) and subsequent apoptosis. Among the stretch-activated ion channels, rapid influx of Ca2+ activate several pathways including signal transduction cascades leading to cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell contraction, activation of potassium channel. Potassium channels play roles in maintaining optimal membrane potentials. Mechanical forces and calcium influx also open chloride channels which act as apoptotic agents through a delineated mechanism.

Recently, Jiang et al. (2016) demonstrated that, static stretch conditions can increase collagen I levels but decrease fibronectin levels compared to a cyclic stretch conditions where collagen I is significantly reduced but fibronectin is markedly increased. Thus, cyclic stretch suppressed human fibroblast proliferation compared to that with static stretch. Again, nuclear envelope proteins such as emerin or lamin A/C were shown to play critical roles in suppressing vascular smooth muscle cells hyperproliferation induced by hyperstretch (Qi et al., 2016).

Stretch induced apoptosis

A balanced cell proliferation/growth and apoptosis is a pre-requisite for normal development and for adaptation to a changing environment (Jacobson et al., 1997). Too little apoptosis can promote cancer and autoimmune diseases; whereas, too much apoptosis can augment ischaemic conditions and drive neurodegeneration (Czabotar et al., 2014). Apoptosis can be triggered either by external receptor-dependent stimuli (ligation of death receptors with their cognate ligands, such as FasL, TRAIL or TNF) or internal mitochondria-mediated signaling (Adams, 2003; Özören and El-Deiry, 2003).

Different stimuli such as intracellular damage, cytotoxic compounds and developmental activates the mitochondrial (intrinsic) pathway of apoptosis (Liao et al., 2004, 2005). In this pathway, stretch activates pro-apoptotic effectors Bax and Bak, which then disrupt the mitochondrial outer membrane resulting in the release of cytochrome c (Figure 3). Cytochrome c then leads to the formation of the apoptosome with the help of apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 (apaf-1) that promotes caspase 9 activation (Li et al., 1997; Luo et al., 1998; Zou et al., 1999). In the death receptor-mediated pathways (extrinsic) of apoptosis, certain death receptor ligands of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family (such as Fas ligand and TNF) bind with their cognate death receptors (FAS and TNFR1, respectively) on the plasma membrane, leading to caspase 8 activation via the Fas-associated death domain protein (FADD) and the TNFR-associated death domain protein (TRADD) in a cytosolic death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) also known as complex II (Wang et al., 2008; He et al., 2009). These two pathways converge at activation of the effector caspases (caspase 3, caspase 7, and caspase 6) (Adams, 2003).

Necrosis, known as a catastrophic form of death, is typically not associated with caspases activation and mediates cells' demise in response to severe injuries or in case of a pathological evet (Vanden Berghe et al., 2004). Although, apoptosis and necrosis may occur simultaneously in response to specific stimuli, the morphological characteristics of cell undergoing necrosis are distinct from those seen in cells undergoing apoptosis (Kroemer and Levine, 2008). However, mechanisms of necrosis due to tissue expansion are not fully understood.

Major roles of growth factors in tissue expansion

The cellular growth, tissue integrity and eventually the reestablishment of the barrier function of the skin is executed and regulated by the coordinated efforts of several cell types (keratinocytes, fibroblasts, macrophages, platelets etc.) and numerous growth factors (biologically active polypeptides) (Werner et al., 2007; Gurtner et al., 2008). The epidermal growth factor (EGF) family, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) family, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), interleukin (IL) family are all important in stress (either mechanical or physiological) induced cell growth (Werner et al., 1994; Shimo et al., 1999; Steiling and Werner, 2003; Shirakata et al., 2005; Secker et al., 2008). The functions of growth factors depend on source and binding with specific receptors and can act by paracrine, autocrine, juxtacrine, and endocrine mechanisms (Barrientos et al., 2008). Earlier studies showed that, EGF, FGF-2, TGF-β, PDGF, and VEGF levels are increased in early after injury and decreased at chronic states and IL-1 and 6, and TNF-α levels increased both in early and chronic states (Brown et al., 1986; Frank et al., 1995). The functions of various growth factors are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Growth factors in response to mechanical or physical stress on different tissues.

| Growth factor | Native cells | Experimental condition (expansion or stress) | Effect on growth factor | Major observations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidermal growth factor (EGF) | Macrophages, Fibroblasts | Burn injuries | ↑ | Keratinocyte proliferation and migration | Grayson et al., 1993 |

| 2 mm incisional wounds on the PU.1 null mouse | ↑ | Reepithelialisation | Martin et al., 2003 | ||

| Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor (HB-EGF) | Macrophages | Keratinocyte-specific HB-EGF-deficient mice | ↓ | Wound closure was markedly impaired | Shirakata et al., 2005 |

| Cells treated with tetracycline (TET) | ↑↑ | Overexpression of HB-EGF inhibits proliferation | Stoll et al., 2012 | ||

| Fibroblast growth factor 1, 2, and 4 (FGF 1, 2, and 4) | Fibroblasts, Macrophages, Endothelial cells, Smooth muscle cells, Chondrocytes, Mast cells | Cultured fibroblasts stimulated with IL-1α | ↑ | Fibroblast proliferation Angiogenesis | Maas-Szabowski and Fusenig, 1996 |

| Transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α) | Macrophages, Keratinocytes | Macrophages isolated from a wound site | ↑ | Keratinocyte migration and reepithelialisation | Rappolee et al., 1988 |

| Transforming growth factor-β1-3 (TGF-β1-3) | Macrophages, Fibroblasts, Keratinocytes, Neutrophils | Adult and fetal wounds | II ↑ |

Reepithelialisation of skin Epidermal differentiation | Cowin et al., 2001a |

| Fetal and adult sheep incisional skin wounding | ↑ | TGF-β3 is anti-scarring | Scheid et al., 2002 | ||

| Amphiregulin (AR) | Keratinocytes | Serum free cultured human keratinocytes | ↑ | Keratinocyte proliferation | Piepkorn et al., 1994 |

| Keratinocyte growth factor (KGF or FGF7) | Fibroblasts | Wounded mice skin | ↓ | Delayed re-epithelialization due to reduced proliferation rate of epidermal keratinocytes | Werner et al., 1994 |

| Platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) | Macrophages, Endothelial cells | Acute incisional wounds in an aging mouse colony | ↓ | The low levels of PDGF in the old cause initial delay in fibroblasts and inflammatory cell infiltration and proliferation within the wounds | Ashcroft et al., 1997 |

| Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) | Mesenchymal cells, Hepatocytes, Adipocytes, Keratinocytes | Adult rat excisional wounds | ↑ | Keratinocyte migration, and proliferation Angiogenesis | Cowin et al., 2001b |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) | Neutrophils, Macrophages, Endothelial cells, Fibroblasts, | Immobilized VEGF in porous collagen scaffold | ↑ | Endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis | Shen et al., 2008 |

| Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) | Fibroblasts, Endothelia | Scratched human corneal epithelial cells | ↑ | CTGF is strongly induced and caused pathophysiology in tissues by inducing matrix deposition, conversion of fibroblasts into contractile myofibroblasts | Secker et al., 2008 |

| Insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) | Fibroblasts, neutrophils, macrophages, hepatocytes and skeletal muscle | Estrogen-deprived mice | ↑ | Keratinocyte and fibroblast proliferation and migration Collagen synthesis and re-epithelialization | Emmerson et al., 2012 |

| Rat surgical incision | ↑ | Re-epithelization | Todorovic et al., 2008 | ||

| Interleukin-I α and β (IL-I α and β) | Neutrophils, Monocytes, Macrophages, Keratinocytes | Irradiated fibroblasts | ↑ | Keratinocyte activation, migration and proliferation Induce KGF expression and fibroblasts creation | Maas-Szabowski et al., 2000 |

| Endothelin-I (ET-I) | Keratinocytes, Fibroblasts, Endothelial cells | Cyclic stretch of cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells (raSMC) and porcine aortic endothelial cells (PAEC) | ↑ (PAEC) ↓ (raSMC) |

Reveal central role for the endothelin system in stretch-induced apoptosis of the smooth muscle cells. ET-1 binding to the ETB receptor subtype results in apoptosis rather than proliferation | Cattaruzza et al., 2000, 2001. |

| Activin | Keratinocytes, Fibroblasts, Inflammatory cells, Macrophages | Normal and wounded skin | ↑ | Stimulates keratinocyte migration, fibroplasia, and matrix production | Hübner et al., 1996 |

↑, increased in response to mechanical strain; ↓, decreased in response to mechanical strain; ↑↑, overexpression in response to mechanical strain; II, unchanged in response to mechanical strain.

Among the growth factors families, the EGF family and the TGF-β family are thought to play central roles (Hashimoto, 2000) and they provide dual-mode regulation of keratinocyte growth via the proliferation-stimulating effect of EGF and the proliferation-inhibiting effect of TGF-β (Amendt et al., 2002; Secker et al., 2008). Although, these growth factors appear to share several downstream pathways of cell membrane molecules, the direct effects of mechanical stress on TGF and EGF are yet to be investigated (Takei et al., 1998). Although, human epidermal keratinocytes express ErbB1, ErbB2, and ErbB3, they do not express ErbB4 (Hashimoto, 2000). Similarly, signals originating from ErbB1 play crucial roles in mediating the pro-survival and proliferative programs of keratinocytes (Shirakata et al., 2010). The expression of cadherins, integrins, and various other ECM components that contribute to the maturation of new blood vessels are regulated by FGF2 (Cross and Claesson-Welsh, 2001). HB-EGF shows a starring role in the reepithelialisation and granulation tissue formation (Marikovsky et al., 1996). The strongest autocrine stimulation to cell growth is provided by amphiregulin (Piepkorn et al., 1994).

Ion channel related to mechanical strain

Mechanical stress to the cell surface activates the mechanosensitive ion channels along with other membrane-associated signal-transduction molecules (De Filippo and Atala, 2002; Wang et al., 2009). The precise mechanism of activation and modulation of ion channels by mechanical forces that results in biologically meaningful signals are subjects of intensive research (Martinac, 2014). Sachs (1991) reported that, in order to make conformational changes of a channel, external forces must do work on the channel and be dominated by the distance the force move. Howard and Hudspeth (1988) estimated that the stress activated channels change their dimensions by 4 nm between the closed and open states. These stretch-induced ion channels are mainly cation (Ca2+, K+, and Na+) channels and a few anion (Cl−) channels (Jackson, 2000; Nilius and Droogmans, 2001).

The vast majority of channels open because of the changes in lipid bilayer, membrane fluidity or tension and are regulated by voltage, extracellular ligands, phosphorylation, influx of Ca2+ and direct (physical interactions between G-protein subunits and the channel protein) or indirect (via second messengers and protein kinases) interaction with activated G proteins (Christensen, 1987; Maroto et al., 2005; Lumpkin and Caterina, 2007; Hahn and Schwartz, 2009). The mechanosensitive activities of ion channels are cell dependent and vary from cell to cell (Hsieh and Nguyen, 2005). The elevated intracellular Ca2+ levels are cytotoxic and provide the apoptotic stimulus in multiple cell types. The studies of past decades indicated the involvement of different ions in stretch induced response and cytoskeleton are also associated (Jackson, 2000; Wang et al., 2001). However, the precise ion channels related mechanisms for tissue expansion are yet to be studied.

Second messengers system in strain-induced responses

The exact role of second messengers system in response to tissue expansion (i.e., epithelial cell proliferation) is not clearly elucidated (De Filippo and Atala, 2002). Several investigations in last decades of the past century reported that, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) plays an important role to influence cell growth, differentiation, proliferation and protein synthesis depending on the source of cells and experimental conditions (Bang et al., 1992; Florin-Christensen et al., 1993; Zhang et al., 2016). Takei et al. (1997) found significant increase of protein production in keratinocytes subjected to cyclic strain. Moreover, net collagen amount decreases when the levels of cAMP in skin fibroblasts is increased. Study of Acute and chronic cyclic strain reduces adenylate cyclase activity in cultured coronary vascular smooth muscle cells that could promote strain-induced cell contraction (Wiersbitzky et al., 1994). The findings of previous researches on second messengers are listed in the Table 3.

Table 3.

Effects of mechanical strain on major second messengers.

| Second messenger | Experimental condition (expansion or stress) | Effects on second messenger | Major observation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) | Cyclical elongation and relaxation of smooth muscle cells grown on elastic membrane | ↑ | Collagen production inhibited by raised cAMP. | Kollros et al., 1987 |

| Round tissue expanders were placed dorsally | ↓ | Protein production increased in expanded tissue | Johnson et al., 1988 | |

| Constant and cyclic strain (150 mmHg for 5 days) of human keratinocytes | ↓ | Protein production significantly increased | Takei et al., 1997 | |

| Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) | Cyclical elongation and relaxation of smooth muscle cells grown on elastic membrane | ↑ | Collagen production inhibited by increased PGE2. | Kollros et al., 1987 |

| Constant and cyclic strain (150 mmHg for 5 days) of human keratinocytes | ↓ | Protein production significantly increased | Takei et al., 1997 | |

| Phosphodiesterase IV (PDE IV) | Constant and cyclic strain (150 mmHg for 5 days) of human keratinocytes | ↑ | Controll cAMP levels in human keratinocytes | Takei et al., 1997 |

↑, increased in response to mechanical strain; ↓, decreased in response to mechanical strain.

Inositol phosphate (IP), c-fos, and phospholipids (PL) are thought to mediate extracellular signals to the nucleus but the precise mechanisms need further reaserch (Takei et al., 1998). Moreover, Molinari (2015), proposed hydrogen ion (H+) as a second messenger to mediate Ca2+ mobilization especially in IP3/Ca2+ signaling pathway. At the beginning of 21st century, Buscà et al. (2000) reported that the BRAF gene (which mediates growth signaling at a level just below RAS) can be activated by cAMP in melanocytes. Extracellular signals (growth factors) that activate G-protein-couples receptor can result in the activation of adenylate cyclase to upregulate cAMP leading to the activation of RAS and further activation of BRAF and the downstream cascades (Simonds, 1999; Davies et al., 2002; Pollock and Meltzer, 2002). Likewise the studies on second messengers have been done on different cell lines, this study was also performed with cultured cell lines derived from human tumors, so further investigations are needed to be executed with expanded tissue and acutely stretched skins to determine the precise roles of the ubiquitous and archetypal intracellular second messengers.

Conclusion and future perspectives

In this article, recent advances in tissue expansion in the field of plastic and reconstructive surgery were described with a special focus on the biological response and the activated pathways leading to either proliferation or apoptosis. Emphasis was given on the roles of membrane bound molecules such as integrins, G-protein, growth factors, stretch-activated ion channels, and secondary messengers. Although, studies of past decades demonstrated that, mechanical stimulation is capable to activate highly integrated signaling cascades resulting in the new skin production, questions remain on how different types of stimulation works on, different cells following different signal transduction pathways. For example, studies on the cells from the kidney differ significantly compared to the cells of skin which are subjected to constant expansion or mechanical forces. Moreover, studies using cultured cells rather than intact tissue (skin) cannot clarify the exact effects of tissue expansion. Similarly, stimulus such as shearing, heat, and shock cannot provide natural microenvironment to better understand how cell adapt to changes during tissue expansion. Furthermore, the signaling pathways activated by different biochemical factors were investigated in linear methods such as single pathway analysis, which is insufficient to describe multiple signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation and/or apoptosis. Therefore, in depth comparative proteomic and genomic analysis with expanded tissue or acutely stretched skin would reveal the pathways and molecules responsible for cell proliferation and/or apoptosis ultimately skin regeneration.

Author contributions

Concept development: MTR. Writing the manuscript: MAR, MTR, MSH, ZR, NY, and JC. Literature review for data collection: MAR, MTR, MSH, and ZR. Figure and Tables: MAR, MTR, MSH.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by grant (UM.C/625/1/HIR/MOHE/DENT/21) from Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia, to Associate Professor ZR Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya. Authors wish to acknowledge Marzouq Abedur Rahman for language editing.

References

- Aarabi S., Longaker M. T., Gurtner G. C. (2007). Hypertrophic scar formation following burns and trauma: new approaches to treatment. PLoS Med. 4:e234. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams J. M. (2003). Ways of dying: multiple pathways to apoptosis. Genes Dev. 17, 2481–2495. 10.1101/gad.1126903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler N., Dorafshar A. H., Bauer B. S., Hoadley S., Tournell M. (2009). Tissue expander infections in pediatric patients: management and outcomes. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 124, 484–489. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181adcf20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amendt C., Mann A., Schirmacher P., Blessing M. (2002). Resistance of keratinocytes to TGFβ-mediated growth restriction and apoptosis induction accelerates re-epithelialization in skin wounds. J. Cell Sci. 115, 2189–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonyshyn O., Gruss J. S., Mackinnon S. E., Zuker R. (1988). Complications of soft tissue expansion. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 41, 239–250. 10.1016/0007-1226(88)90107-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argenta L. C. (1984). Controlled tissue expansion in reconstructive surgery. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 37, 520–529. 10.1016/0007-1226(84)90143-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft G. S., Horan M. A., Ferguson M. W. (1997). The effects of ageing on wound healing: immunolocalisation of growth factors and their receptors in a murine incisional model. J. Anat. 190(Pt 3), 351–365. 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1997.19030351.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austad E. D., Pasyk K. A., McClatchey K. D., Cherry G. W. (1982). Histomorphologic evaluation of guinea pig skin and soft tissue after controlled tissue expansion. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 70, 704–710. 10.1097/00006534-198212000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader D. L., Bowker P. (1983). Mechanical characteristics of skin and underlying tissues in vivo. Biomaterials 4, 305–308. 10.1016/0142-9612(83)90033-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang Y. J., Kim S. J., Danielpour D., O'Reilly M. A., Kim K. Y., Myers C. E., et al. (1992). Cyclic AMP induces transforming growth factor beta 2 gene expression and growth arrest in the human androgen-independent prostate carcinoma cell line PC-3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 3556–3560. 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos S., Stojadinovic O., Golinko M. S., Brem H., Tomic-Canic M. (2008). Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 16, 585–601. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00410.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bascom D. A., Wax M. K. (2002). Tissue expansion in the head and neck: current state of the art. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 10, 273–277. 10.1097/00020840-200208000-00005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. L., Curtsinger L., III, Brightwell J. R., Ackerman D. M., Tobin G. R., Polk H. C., et al. (1986). Enhancement of epidermal regeneration by biosynthetic epidermal growth factor. J. Exp. Med. 163, 1319–1324. 10.1084/jem.163.5.1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscà R., Abbe P., Mantoux F., Aberdam E., Peyssonnaux C., Eychène A., et al. (2000). Ras mediates the cAMP-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) in melanocytes. EMBO J. 19, 2900–2910. 10.1093/emboj/19.12.2900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K. A., Pins G. D. (2010). Carbodiimide conjugation of fibronectin on collagen basal lamina analogs enhances cellular binding domains and epithelialization. Tissue Eng. Part A. 16, 829–838. 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carragher N. O., Frame M. C. (2004). Focal adhesion and actin dynamics: a place where kinases and proteases meet to promote invasion. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 241–249. 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaruzza M., Dimigen C., Ehrenreich H., Hecker M. (2000). Stretch-induced endothelin B receptor-mediated apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. FASEB J. 14, 991–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaruzza M., Eberhardt I., Hecker M. (2001). Mechanosensitive transcription factors involved in endothelin B receptor expression. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36999–37003. 10.1074/jbc.M105158200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. S., Mrksich M., Huang S., Whitesides G. M., Ingber D. E. (1997). Geometric control of cell life and death. Science 276, 1425–1428. 10.1126/science.276.5317.1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien S. (2007). Mechanotransduction and endothelial cell homeostasis: the wisdom of the cell. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292, H1209–H1224. 10.1152/ajpheart.01047.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen O. (1987). Mediation of cell volume regulation by Ca2+ influx through stretch-activated channels. Nature 330, 66–68. 10.1038/330066a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton M. S., Heiss K. F., Keating J. J., Mackay G., Ricketts R. R. (2011). Use of tissue expanders in the repair of complex abdominal wall defects. J. Pediatr. Surg. 46, 372–377. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin A. J., Holmes T. M., Brosnan P., Ferguson M. W. (2001a). Expression of TGF-beta and its receptors in murine fetal and adult dermal wounds. Eur. J. Dermatol. 11, 424–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin A. J., Kallincos N., Hatzirodos N., Robertson J. G., Pickering K. J., Couper J., et al. (2001b). Hepatocyte growth factor and macrophage-stimulating protein are upregulated during excisional wound repair in rats. Cell Tissue Res. 306, 239–250. 10.1007/s004410100443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross M. J., Claesson-Welsh L. (2001). FGF and VEGF function in angiogenesis: signalling pathways, biological responses and therapeutic inhibition. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 22, 201–207. 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01676-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czabotar P. E., Lessene G., Strasser A., Adams J. M. (2014). Control of apoptosis by the BCL-2 protein family: implications for physiology and therapy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 49–63. 10.1038/nrm3722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies H., Bignell G. R., Cox C., Stephens P., Edkins S., Clegg S., et al. (2002). Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 417, 949–954. 10.1038/nature00766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filippo R. E., Atala A. (2002). Stretch and growth: the molecular and physiologic influences of tissue expansion. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 109, 2450–2462. 10.1097/00006534-200206000-00043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmerson E., Campbell L., Davies F. C., Ross N. L., Ashcroft G. S., Krust A., et al. (2012). Insulin-like growth factor-1 promotes wound healing in estrogen-deprived mice: new insights into cutaneous IGF-1R/ERα cross talk. J. Invest. Dermatol. 132, 2838–2848. 10.1038/jid.2012.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florin-Christensen M., Missero C., Florin-Christensen J., Tranque P., Cajal S. R., Dotto G. P. (1993). Counteracting Effects of E1a transformation on cAMP growth inhibition. Exp. Cell Res. 207, 57–61. 10.1006/excr.1993.1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S., Hubner G., Breier G., Longaker M. T., Greenhalgh D. G., Werner S. (1995). Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in cultured keratinocytes. Implications for normal and impaired wound healing. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 12607–12613. 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson T., Kenedi R. M., Craik J. E. (1965). The mobile micro-architecture of dermal collagen: a bio-engineering study. Br. J. Surg. 52, 764–770. 10.1002/bjs.1800521017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson L. S., Hansbrough J. F., Zapata-Sirvent R. L., Dore C. A., Morgan J. L., Nicolson M. A. (1993). Quantitation of cytokine levels in skin graft donor site wound fluid. Burns 19, 401–405. 10.1016/0305-4179(93)90061-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner G. C., Werner S., Barrandon Y., Longaker M. T. (2008). Wound repair and regeneration. Nature 453, 314–321. 10.1038/nature07039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzey S., Alhan D., Sahin I., Aykan A., Eski M., Nisanci M. (2015). Our experiences on the reconstruction of lateral scalp burn alopecia with tissue expanders. Burns 41, 631–637. 10.1016/j.burns.2014.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafezi F., Naghibzadeh B., Pegahmehr M., Nouhi A. (2009). Use of overinflated tissue expanders in the surgical repair of head and neck scars. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 62, e413–e420. 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.03.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn C., Schwartz M. A. (2009). Mechanotransduction in vascular physiology and atherogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 53–62. 10.1038/nrm2596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K. (2000). Regulation of keratinocyte function by growth factors. J. Dermatol. Sci. 24, S46–S50. 10.1016/S0923-1811(00)00141-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S., Wang L., Miao L., Wang T., Du F., Zhao L., et al. (2009). Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-α. Cell 137, 1100–1111. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Z., Yang Q., Chen T., Hao L., Li Y., Li D. (2012). The use of self-inflating hydrogel expanders in pediatric patients with congenital microphthalmia in China. J. AAPOS. 16, 458–463. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J., Hudspeth A. J. (1988). Compliance of the hair bundle associated with gating of mechanoelectrical transduction channels in the Bullfrog's saccular hair cell. Neuron 1, 189–199. 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90139-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh M. H., Nguyen H. T. (2005). Molecular mechanism of apoptosis induced by mechanical Forces 245, 45–90. 10.1016/s0074-7696(05)45003-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Ingber D. E. (1999). The structural and mechanical complexity of cell-growth control. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, E131–E138. 10.1038/13043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Qu X., Li Q. (2011). Risk factors for complications of tissue expansion: a 20-year systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 128, 787–797. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182221372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübner G., Hu Q., Smola H., Werner S. (1996). Strong induction of activin expression after injury suggests an important role of activin in wound repair. Dev. Biol. 173, 490–498. 10.1006/dbio.1996.0042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R. O. (2002). Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110, 673–687. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00971-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaalouk D. E., Lammerding J. (2009). Mechanotransduction gone awry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 63–73. 10.1038/nrm2597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson W. F. (2000). Ion channels and vascular tone. Hypertension 35(1 Pt 2), 173–178. 10.1161/01.HYP.35.1.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson M. D., Weil M., Raff M. C. (1997). Programmed cell death in animal development. Cell 88, 347–354. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81873-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M., Qiu J., Zhang L., Lü D., Long M., Chen L., et al. (2016). Changes in tension regulates proliferation and migration of fibroblasts by remodeling expression of ECM proteins. Exp. Ther. Med. 12, 1542–1550. 10.3892/etm.2016.3497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P. E., Kernahan D. A., Bauer B. S. (1988). Dermal and epidermal response to soft-tissue expansion in the pig. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 81, 390–397. 10.1097/00006534-198803000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. M., Lowe L., Brown M. D., Sullivan M. J., Nelson B. R. (1993). Histology and physiology of tissue expansion. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 19, 1074–1078. 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1993.tb01002.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper E. M., Ridgway E. B., Rabie A., Lee B. T., Chen C., Lin S. J. (2012). Staged scalp soft tissue expansion before delayed allograft cranioplasty: a technical report. Neurosurgery 71(1 Suppl Operative), 15–20. discussion: 21. 10.1227/neu.0b013e318242cea2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenedi R. M., Gibson T., Evans J. H., Barbenel J. C. (1975). Tissue mechanics. Phys. Med. Biol. 20, 699–717. 10.1088/0031-9155/20/5/001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheradmand A. A., Garajei A., Motamedi M. H. (2011). Nasal reconstruction: experience using tissue expansion and forehead flap. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 69, 1478–1484. 10.1016/j.joms.2010.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knies Y., Bernd A., Kaufmann R., Bereiter-Hahn J., Kippenberger S. (2006). Mechanical stretch induces clustering of β1-integrins and facilitates adhesion. Exp. Dermatol. 15, 347–355. 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2006.00422.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobus K. F. (2007). Cleft palate repair with the use of osmotic expanders: a preliminary report. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 60, 414–421. 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.01.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollros P. R., Bates S. R., Mathews M. B., Horwitz A. L., Glagov S. (1987). Cyclic AMP inhibits increased collagen production by cyclically stretched smooth muscle cells. Lab. Invest. 56, 410–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G., Levine B. (2008). Autophagic cell death: the story of a misnomer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 1004–1010. 10.1038/nrm2529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H., Paschos N. K., Hu J. C., Athanasiou K. (2016). Articular cartilage tissue engineering: the role of signaling molecules. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 1173–1194. 10.1007/s00018-015-2115-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrabee W. F., Jr, Sutton D. (1986). A finite element model of skin deformation. II. An experimental model of skin deformation. Laryngoscope 96, 406–412. 10.1288/00005537-198604000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrabee W. F., Jr, Sutton D., Galt J. A. (1986). A finite element model of skin deformation: I - Biomechanics of skin and soft tissue: a review; II - An experimental model of skin deformation; III - The finite element model. Laryngoscope 96, 399–419. 10.1288/00005537-198604000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurence V. G., Martin J. B., Wirth G. A. (2012). External tissue expanders as adjunct therapy in closing difficult wounds. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 65, e297–e299. 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton W. D., Russell R. C., Feller A. M., Eriksson E., Mathur A., Zook E. G. (1988). Experimental pretransfer expansion of free-flap donor sites: II. Physiology, histology, and clinical correlation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 82, 76–87. 10.1097/00006534-198882010-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Nijhawan D., Budihardjo I., Srinivasula S. M., Ahmad M., Alnemri E. S., et al. (1997). Cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of Apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell 91, 479–489. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80434-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao X. D., Wang X. H., Jin H. J., Chen L. Y., Chen Q. (2004). Mechanical stretch induces mitochondria-dependent apoptosis in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes and G2/M accumulation in cardiac fibroblasts. Cell Res. 14, 16–26. 10.1038/sj.cr.7290198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao X., Wang X., Gu Y., Chen Q., Chen L.-Y. (2005). Involvement of death receptor signaling in mechanical stretch-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Life Sci. 77, 160–174. 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder-Ganz E., Gefen A. (2004). Mechanical compression-induced pressure sores in rat hindlimb: muscle stiffness, histology, and computational models. J. App. Physiol. 96, 2034–2049. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00888.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohsiriwat V., Peccatori F. A., Martella S., Azim H. A., Jr., Sarno M. A., Galimberti V., et al. (2013). Immediate breast reconstruction with expander in pregnant breast cancer patients. Breast 22, 657–660. 10.1016/j.breast.2013.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumpkin E. A., Caterina M. J. (2007). Mechanisms of sensory transduction in the skin. Nature 445, 858–865. 10.1038/nature05662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X., Budihardjo I., Zou H., Slaughter C., Wang X. (1998). Bid, a Bcl2 interacting protein, mediates cytochrome c release from mitochondria in response to activation of cell surface death receptors. Cell 94, 481–490. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81589-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas-Szabowski N., Fusenig N. E. (1996). Interleukin-1-induced growth factor expression in postmitotic and resting fibroblasts. J. Invest. Dermatol. 107, 849–855. 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12331158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas-Szabowski N., Stark H.-J., Fusenig N. E. (2000). Keratinocyte growth regulation in defined organotypic cultures through IL-1-induced keratinocyte growth factor expression in resting fibroblasts. 114, 1075–1084. 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00987.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marikovsky M., Vogt P., Eriksson E., Rubin J. S., Taylor W. G., Sasse J., et al. (1996). Wound fluid-derived heparin-binding EGF-Like Growth Factor (HB-EGF) is synergistic with Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I for Balb/MK keratinocyte proliferation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 106, 616–621. 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12345413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroto R., Raso A., Wood T. G., Kurosky A., Martinac B., Hamill O. P. (2005). TRPC1 forms the stretch-activated cation channel in vertebrate cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 179–185. 10.1038/ncb1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P., D'Souza D., Martin J., Grose R., Cooper L., Maki R., et al. (2003). Wound healing in the PU.1 null mouse—tissue repair is not dependent on inflammatory cells. Curr. Biol. 13, 1122–1128. 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00396-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinac B. (2014). The ion channels to cytoskeleton connection as potential mechanism of mechanosensitivity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1838, 682–691. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moelleken B. R., Mathes S. J., Cann C. E., Simmons D. J., Ghafoori G. (1990). Long-term effects of tissue expansion on cranial and skeletal bone development in neonatal miniature swine: clinical findings and histomorphometric correlates. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 86, 825–834. 10.1097/00006534-199011000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinari G. (2015). Is hydrogen ion (H+) the real second messenger in calcium signalling? Cell. Signal. 27, 1392–1397. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motamed S., Niazi F., Atarian S., Motamed A. (2008). Post-burn head and neck reconstruction using tissue expanders. Burns 34, 878–884. 10.1016/j.burns.2007.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann C. G. (1957). The expansion of an area of skin by progressive distention of a subcutaneous balloon: use of the method for securing skin for subtotal reconstruction of the ear. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 19, 124–130. 10.1097/00006534-195702000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikkhah D., Yildrimer L., Bulstrode N. W. (2015). Tissue expansion, in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: Approach and Techniques. 1st Edn., eds Farhadieh R. D., Bulstrode N. W., Cugno S. (West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd; ), 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B., Droogmans G. (2001). Ion channels and their functional role in vascular endothelium. Physiol. Rev. 81, 1415–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özören N., El-Deiry W. S. (2003). Cell surface death receptor signaling in normal and cancer cells. Semin. Cancer Biol. 13, 135–147. 10.1016/S1044-579X(02)00131-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamplona D. C., Weber H. I., Leta F. R. (2014). Optimization of the use of skin expanders. Skin Res. Technol. 20, 463–472. 10.1111/srt.12141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasyk K. A., Argenta L. C., Hassett C. (1988). Quantitative analysis of the thickness of human skin and subcutaneous tissue following controlled expansion with a silicone implant. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 81, 516–523. 10.1097/00006534-198804000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasyk K. A., Austad E. D., McClatchey K. D., Cherry G. W. (1982). Electron microscopic evaluation of guinea pig skin and soft tissues “expanded” with a self-inflating silicone implant. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 70, 37–45. 10.1097/00006534-198207000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piepkorn M., Lo C., Plowman G. (1994). Amphiregulin-dependent proliferation of cultured human keratinocytes: autocrine growth, the effects of exogenous recombinant cytokine, and apparent requirement for heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. J. Cell. Physiol. 159, 114–120. 10.1002/jcp.1041590115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plenz G., Löffler A., Siegert R., Weerda H., Müller P. K. (1998). The effect of tissue expansion on the expression of collagen type I and type III mRNA in distinct areas of skin in the dog as an animal model. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 255, 473–477. 10.1007/s004050050102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock P. M., Meltzer P. S. (2002). Cancer: lucky draw in the gene raffle. Nature 417, 906–907. 10.1038/417906a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y. X., Yao Q. P., Huang K., Shi Q., Zhang P., Wang G. L., et al. (2016). Nuclear envelope proteins modulate proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells during cyclic stretch application. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 5293–5298. 10.1073/pnas.1604569113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappolee D. A., Mark D., Banda M. J., Werb Z. (1988). Wound macrophages express TGF-alpha and other growth factors in vivo: analysis by mRNA phenotyping. Science 241, 708–712. 10.1126/science.3041594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs F. (1991). Mechanical transduction by membrane ion channels: a mini review. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 104, 57–60. 10.1007/BF00229804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago G. F., Bograd B., Basile P. L., Howard R. T., Fleming M., Valerio I. L. (2012). Soft tissue injury management with a continuous external tissue expander. Ann. Plast. Surg. 69, 418–421. 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31824a4584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki G. H., Pang C. Y. (1984). Pathophysiology of skin flaps raised on expanded pig skin. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 74, 59–67. 10.1097/00006534-198407000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxby P. J. (1988). Survival of island flaps after tissue expansion: a pig model. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 81, 30–34. 10.1097/00006534-198801000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid A., Wenger R. H., Schäffer L., Camenisch I., Distler O., Ferenc A., et al. (2002). Physiologically low oxygen concentrations in fetal skin regulate hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and transforming growth factor-beta3. FASEB J. 16, 411–413. 10.1096/fj.01-0496fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M. A., DeSimone D. W. (2008). Cell adhesion receptors in mechanotransduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 551–556. 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secker G. A., Shortt A. J., Sampson E., Schwarz Q. P., Schultz G. S., Daniels J. T. (2008). TGFβ stimulated re-epithelialisation is regulated by CTGF and Ras/MEK/ERK signalling. Exp. Cell Res. 314, 131–142. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y. H., Shoichet M. S., Radisic M. (2008). Vascular endothelial growth factor immobilized in collagen scaffold promotes penetration and proliferation of endothelial cells. Acta Biomater. 4, 477–489. 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimo T., Nakanishi T., Nishida T., Asano M., Kanyama M., Kuboki T., et al. (1999). Connective tissue growth factor 1induces the proliferation, migration, and tube formation of vascular endothelial cells in vitro, and angiogenesis in vivo. J. Biochem. 126, 137–145. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakata Y., Kimura R., Nanba D., Iwamoto R., Tokumaru S., Morimoto C., et al. (2005). Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor accelerates keratinocyte migration and skin wound healing. J. Cell Sci. 118(Pt 11), 2363–2370. 10.1242/jcs.02346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakata Y., Tokumaru S., Sayama K., Hashimoto K. (2010). Auto- and cross-induction by betacellulin in epidermal keratinocytes. J. Dermatol. Sci. 58, 162–164. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegert R., Weerda H., Hoffmann S., Mohadjer C. (1993). Clinical and experimental evaluation of intermittent intraoperative short- term expansion. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 92, 248–254. 10.1097/00006534-199308000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver F. H., Kato Y. P., Ohno M., Wasserman A. J. (1992). Analysis of mammalian connective tissue: relationship between hierarchical structures and mechanical properties. J. Long Term Eff. Med. Implants 2, 165–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver F. H., Siperko L. M., Seehra G. P. (2003). Mechanobiology of force transduction in dermal tissue. Skin Res. Technol. 9, 3–23. 10.1034/j.1600-0846.2003.00358.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonds W. F. (1999). G protein regulation of adenylate cyclase. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 20, 66–73. 10.1016/S0165-6147(99)01307-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P., Chen C., Pal-Ghosh S., Stepp M. A., Sheppard D., Van De Water L. (2009). Loss of integrin α9β1 results in defects in proliferation, causing poor re-epithelialization during cutaneous wound healing. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 217–228. 10.1038/jid.2008.201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skutek M., van Griensven M., Zeichen J., Brauer N., Bosch U. (2003). Cyclic mechanical stretching of human patellar tendon fibroblasts: activation of JNK and modulation of apoptosis. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 11, 122–129. 10.1007/s00167-002-0322-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark G. B., Hong C., Futrell J. W. (1987). Rapid elongation of arteries and veins in rats with a tissue expander. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 80, 570–581. 10.1097/00006534-198710000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiling H., Werner S. (2003). Fibroblast growth factors: key players in epithelial morphogenesis, repair and cytoprotection. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 14, 533–537. 10.1016/j.copbio.2003.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll S. W., Rittié L., Johnson J. L., Elder J. T. (2012). Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 132, 2148–2157. 10.1038/jid.2012.78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan M. C., Bucknall D. G., Czernuszka J. T., Pigott D. W., Goodacre T. E. (2012). Development of a novel anisotropic self-inflating tissue expander: in vivo submucoperiosteal performance in the porcine hard palate. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 129, 79–88. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182362100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson R. W. (2014). Controlled tissue expansion in facial reconstruction, in Local Flaps in Facial Reconstruction: Expert Consult, ed Baker S. R. (Atlanta, GA: Elsevier Health Sciences; ), 671–696. [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro S., Shattil S. J., Eto K., Tai V., Liddington R. C., de Pereda J. M., et al. (2003). Talin binding to integrin ß tails: a final common step in integrin activation. Science 302, 103–106. 10.1126/science.1086652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei T., Mills I., Arai K., Sumpio B. E. (1998). Molecular basis for tissue expansion: clinical implications for the surgeon. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 102, 247–258. 10.1097/00006534-199807000-00044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei T., Rivas-Gotz C., Delling C. A., Koo J. T., Mills I., McCarthy T. L., et al. (1997). Effect of strain on human keratinocytes in vitro. J. Cell. Physiol. 173, 64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic V., Pesko P., Micev M., Bjelovic M., Budec M., Micic M., et al. (2008). Insulin-like growth factor-I in wound healing of rat skin. Regul. Pept. 150, 7–13. 10.1016/j.regpep.2008.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsioli V., Papazoglou L. G., Papaioannou N., Psalla D., Savvas I., Pavlidis L., et al. (2015). Comparison of three skin-stretching devices for closing skin defects on the limbs of dogs. J. Vet. Sci. 16:99. 10.4142/jvs.2015.16.1.99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanden Berghe T., van Loo G., Saelens X., Van Gurp M., Brouckaert G., Kalai M., et al. (2004). Differential signaling to apoptotic and necrotic cell death by Fas-associated death domain protein FADD. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 7925–7933. 10.1074/jbc.M307807200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Kolk C. A., McCann J. J., Knight K. R., O'Brien B. M. (1987). Some further characteristics of expanded tissue. Clin. Plast. Surg. 14, 447–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rappard J. H., Molenaar J., van Doorn K., Sonneveld G. J., Borghouts J. M. (1988). Surface-area increase in tissue expansion. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 82, 833–839. 10.1097/00006534-198811000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaegen P. D., Schouten H. J., Tigchelaar-Gutter W., van Marle J., van Noorden C. J., Middelkoop E., et al. (2012). Adaptation of the dermal collagen structure of human skin and scar tissue in response to stretch: an experimental study. Wound Repair Regen. 20, 658–666. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00827.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Du F., Wang X. (2008). TNF-α induces two distinct caspase-8 activation pathways. Cell 133, 693–703. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N., Tytell J. D., Ingber D. E. (2009). Mechanotransduction at a distance: mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 75–82. 10.1038/nrm2594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.-Q., Song L.-S., Lakatta E. G., Cheng H. (2001). Ca2+ signalling between single L-type Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors in heart cells. Nature 410, 592–596. 10.1038/35069083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner S., Krieg T., Smola H. (2007). Keratinocyte-fibroblast interactions in wound healing. J. Invest. Dermatol. 127, 998–1008. 10.1038/sj.jid.5700786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner S., Smola H., Liao X., Longaker M. T., Krieg T., Hofschneider P. H., et al. (1994). The function of KGF in morphogenesis of epithelium and reepithelialization of wounds. Science 266, 819–822. 10.1126/science.7973639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernig F., Mayr M., Xu Q. (2003). Mechanical stretch-induced apoptosis in smooth muscle cells is mediated by 1-integrin signaling pathways. Hypertension 41, 903–911. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000062882.42265.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersbitzky M., Mills I., Sumpio B. E., Gewirtz H. (1994). Chronic cyclic strain reduces adenylate cyclase activity and stimulatory G protein subunit levels in coronary smooth muscle cells. Exp. Cell Res. 210, 52–55. 10.1006/excr.1994.1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmi B. J., Blackwell S. J., Mancoll J. S., Phillips L. G. (1998). Creep vs. stretch: a review of the viscoelastic properties of skin. Ann. Plast. Surg. 41, 215–219. 10.1097/00000637-199808000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong V. W., Rustad K. C., Galvez M. G., Neofytou E., Glotzbach J. P., Januszyk M., et al. (2011). Engineered pullulan-collagen composite dermal hydrogels improve early cutaneous wound healing. Tissue Eng. Part A. 17, 631–644. 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak M. A., Modzelewska K., Kwong L., Keely P. J. (2004). Focal adhesion regulation of cell behavior. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1692, 103–119. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W., Gu S., Sun C., He W., Xie X., Li X., et al. (2015). Altered FGF signaling pathways impair cell proliferation and elevation of palate shelves. PLoS ONE 10:e0136951. 10.1371/journal.pone.0136951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano S., Komine M., Fujimoto M., Okochi H., Tamaki K. (2004). Mechanical stretching in vitro regulates signal transduction pathways and cellular proliferation in human epidermal keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 122, 783–790. 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22328.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamir E., Geiger B. (2001). Molecular complexity and dynamics of cell-matrix adhesions. J. Cell Sci. 114(Pt 20), 3583–3590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Zhang L., Qi Y., Xu H. (2016). Mitochondrial cAMP signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 73, 4577–4590. 10.1007/s00018-016-2282-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H., Li Y., Liu X., Wang X. (1999). An APAF-1.cytochrome c multimeric complex is a functional apoptosome that activates procaspase-9. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 11549–11556. 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]