Abstract

Background

Despite widespread use of adjuvant irradiation for head and neck cancer, the extent of damage to the underlying bone is not fully understood, but is associated with pathologic fractures, nonunion, and osteoradionecrosis. The authors’ laboratory previously demonstrated that radiation significantly impedes new bone formation in the murine mandible. We hypothesize that the detrimental effects of human equivalent radiation on the murine mandible results in a dose-dependent degradation in traditional micro-CT metrics.

Methods

Fifteen male Sprague-Dawley rats were randomized into three radiation dosage groups: low (5.91 Gy), middle (7 Gy), and high (8.89 Gy), delivered in five daily fractions. These dosages approximated 75, 100 and 150 percent, respectively, of the biologically equivalent dose that the human mandible receives during radiation treatment. Hemimandibles were harvested 56 days after radiation and scanned using microCT. Bone mineral density, tissue mineral density, and bone volume fraction were measured along with microdensitometry measurements.

Results

Animals demonstrated dose dependent side effects of mucositis, alopecia, weight loss and mandibular atrophy with increasing radiation. Traditional microCT parameters were not sensitive enough to demonstrate statistically significant differences between the radiated groups; however microdensitometry analysis showed clear differences between radiated groups and statistically significant changes between radiated and non-radiated groups.

Conclusions

The authors report dose-dependent and clinically significant side effects of fractionated human equivalent radiation to the murine mandible. The authors further report the limited capacity of traditional micro-CT metrics to adequately capture key changes in bone composition and present microdensitometric histogram analysis in order to demonstrate significant radiation induced changes in mineralization patterns.

INTRODUCTION

In conjunction with surgery, radiation therapy (XRT) has become the mainstay of treatment for head and neck cancer (HNC). While XRT has led to an increase in the complete recovery rate for HNC patients, it has also led to increasing attention to the pernicious sequelae of radiation treatment on the underlying bone within the field of radiation.[1] These sequelae, among others, include pathologic fracture as well as osteoradionecrosis. [2] [3] Although newer hyperfractionation schedules have decreased the soft tissue side effects, little evidence has shown how the underlying bone is affected. To our knowledge, no small animal models exist that demonstrate the effects of radiation on the involved mandible at doses that approximate human equivalent HNC treatment. [4-6]

While many plastic surgeons are familiar with the clinical effects of radiation on bone, either early or late, these effects are often not as predictable as we would like. Few studies have looked at the effects of soft tissue radiation on the underlying bone in a step-wise fashion. Even fewer studies have been able to quantitate those effects in a small animal model using a fractionated dosing schedule. [7-9]

Part of the difficulty in interpreting the effects of radiation on underlying bone is that not all tissues in a radiation field “see” the same dose. The overall effect of each delivered dose of radiation is influenced by three main variables: radiation type, tissue type, and the radiation schedule- all of which help to determine the biologically effective dose (BED) for each specific tissue.[10-12]

In an effort to address the lack of objective measurements of radiation induced damage to the underlying mandible during treatment of head and neck cancer, we aimed to quantify the clinically observed changes that occur at therapeutic dosing schedules and analyze radiomorphometrics derived from microcomputed topography (micro-CT). Our in vivo model quantitatively analyzes the micro-CT measured effects of XRT on craniofacial membranous bone using a fractionated dosing schedule, in order to determine dose dependency. Specifically, we investigated the XRT induced changes at a BED that approximates the same dosage a human mandible is exposed to during treatment for HNC. In an effort to establish a dose response, we also looked at a BED of both 75% and 150% of that seen clinically for HNC.

In Part I and Part II of this series our laboratory was able to demonstrate a dose dependent depletion of both essential osteogenic cells as well as biomechanical properties secondary to XRT in the murine mandible.[13, 14] This set of experiments attempts to discern the effects of radiation on the measurable micro CT parameters of bone at doses less than, equal to and greater than that received by patients undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer in a murine model of mandibular irradiation. We posit that the clinically significant side effects of weight loss, alopecia, mucositis, and mandibular atrophy will all worsen in a dose dependent fashion. We further hypothesize that the pathologic effects of XRT on membranous bones of the craniofacial skeleton follow a dose response relationship. Our specific aim is to measure the impact of differing dosages of XRT on the traditional micro-CT metrics of mineralization in the murine mandible.

METHODS

15 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (400 g) were obtained through the University of Michigan's University Lab Animal Medicine (ULAM) department in compliance with their subdivision of the University of Michigan's Committee for the Utilization and Care of Animals (UCUCA). They were randomly assigned in three experimental XRT dosages: low dose (5.91 Gy; n=5), middle dose (7 Gy; n=5) and high dose (8.89 Gy; n=5) as well as a control group of 10 animals who received no XRT. Doses were determined according to the Biologically Equivalent Dosing (BED=n * d * (1 + d/ (α/β)) in order to approximate 75, 100, and 150% of the dose administered to humans for HNC. The animals were subsequently paired in cages and placed in pathogen-free, restricted area, on a 12-hour light/dark schedule. They were weighed and fed standard rat chow and water ad libitum. Based on delivery date and XRT schedule, the rats had 7 days of acclimation prior to handling. Control animals were fed and housed in an identical manner.

BED=n * d * (1 + d/ (α/β)

n= number of fractions, or number of radiation sessions

d=dose of radiation per session

α/β= a specific ratio assigned to every tissue based on its radiosensitivity

Radiation

The rats were anesthetized with an Oxygen-Isoflurane mixture and placed right side down with a custom-designed lead shield over the body with a window cut to expose the left mandible. The rats’ left hemi-mandible received fractionated external beam XRT at the above dosage doses over five days via a Pantak DXT 300 orthovoltage unit. This method of delivering XRT has been performed for several years in the department of Radiation Oncology under ULAM and UCUCA approved protocols.

The rats were observed for 56 days, and during the initial recovery period subcutaneous infusion of buprenorphine (0.15m/kg) BID with 10 cc Lactated Ringer solution was given to any rats exhibiting signs of radiation-induced discomfort and/or pain.

Tissue harvesting

One animal died from the high dosage group. The remaining animals were euthanized and the left hemi-mandibles were harvested en-bloc, split between the incisors and scanned at 45-μm resolution with micro-CT at 56 days after XRT was completed. Analysis was then performed with Microview 2.2 (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) within the left posterior hemi mandible. Microview assigns each voxel a grayscale value (Hounsfield Unit); to calculate densities, it uses an algorithm that converts the grayscale value of each voxel to mineral content. Higher Hounsfield units (HU) correspond with increasing density of bone.

Contours were created on every fifth serial coronal section within the region of interest (ROI). Only bone within each section was selected. In cases where a part of the incisor or canal was present; the tooth, the canal and the periodontal tissue were excluded for uniformity.

Statistical Analysis

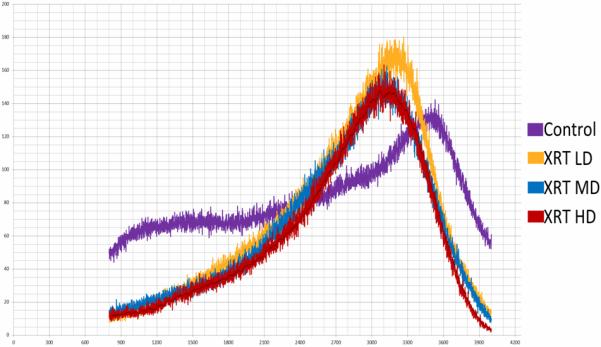

The independent samples t test was used for analyzing bone mineral density (BMD), bone volume fraction (BVF), tissue mineral density (TMD) and microdensitometric analysis of bone mineral density. (SPSS version 16.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Ill.) Results were accepted as statistically significant at a value of p<0.05. BVF was defined as the volume of newly remodeled bone divided by the total volume of the gap, which included air and soft tissue. BMD was defined as the mineral content of newly remodeled bone divided by the total volume of the gap. Histogram, or microdensitometric analysis, was also performed. A histogram is formed by plotting the HU of a specimen on the x-axis and the number of voxels per HU on the y-axis in order to give a pictorial representation of the microdensitometry pattern of the bone, or bone mineral density distribution (BMDD). BMDD is a more sensitive measure of changes in bone mineralization patterns capable of reflecting subtle differences in bone turnover and can be divided into usable metrics reflecting relevant biological events.

Histogram Analysis/BMDD

Background

In order to simplify the voluminous amount of information represented in the histogram, we divided the curve into usable metrics reflecting relevant biological events.

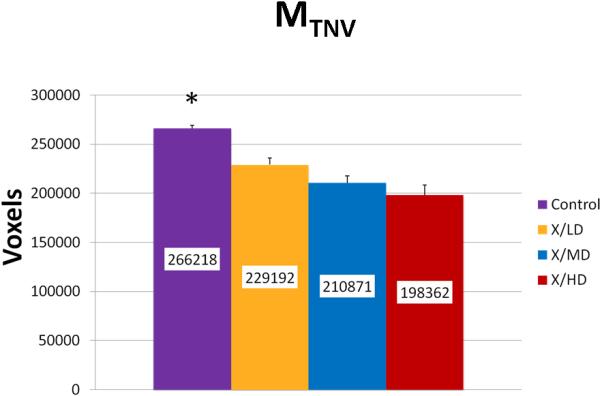

Volume Analysis

Volumetric changes can be compared using Mineralization Total Number of Voxels (MTNV). MTNV is a simple calculation indicating the overall volume of bone being analyzed. This metric may be used to observe small differences in the total mineral volume within the specimens being scanned or to quickly note sizable mineral volume changes due to experimental exposures (such as radiation) or treatment strategies.

Mineralization Quality Analysis

Mineralization Peak (Mpeak) is an indicator of bone quality identifying the most frequent level of mineral density achieved in a sample. Mineralization Width (Mwidth) reflects the array of HU corresponding to the diversity of mineralization densities that are possible in a sample. This parameter becomes important in processes where bone turnover is limited and the range of possible mineralization densities becomes restricted. Mineralization Weighted Mean (Mwmean) is the average weighted f per HU represented in the sample. Incidentally, this is the same calculation for the BMD metric and is used as an indicator of the average mineralization density represented in a volume of interest (VOI). It is worth noting here the wealth of information surrounding that metric that can be derived from a histogram analysis.

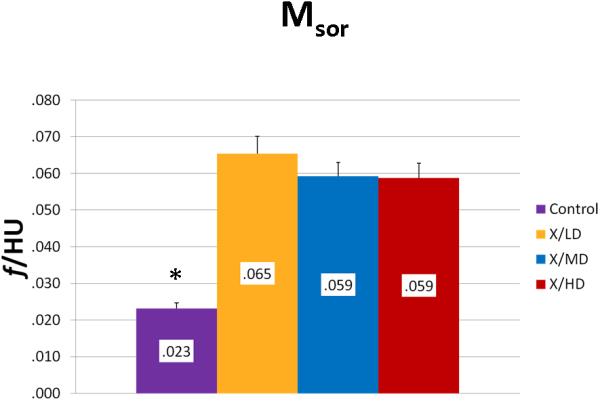

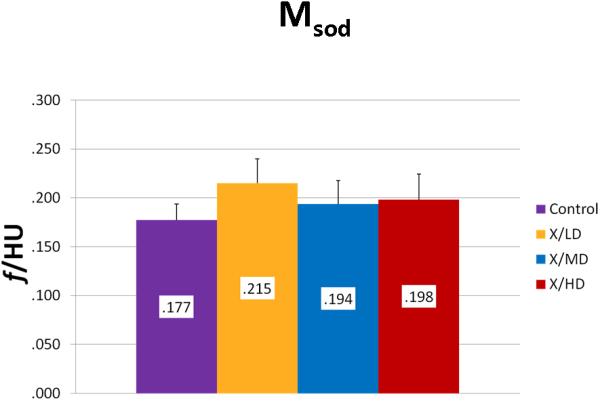

Bone Mineral Maturity/Growth Analysis

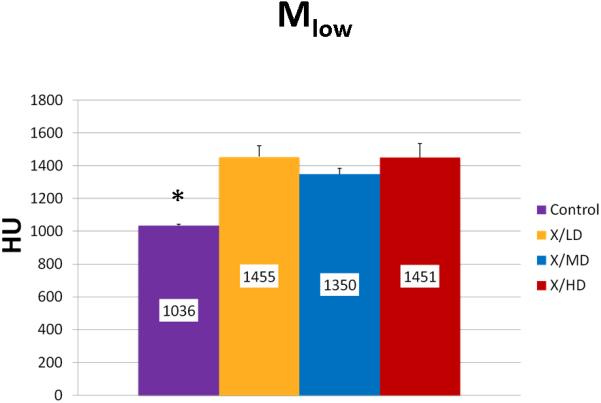

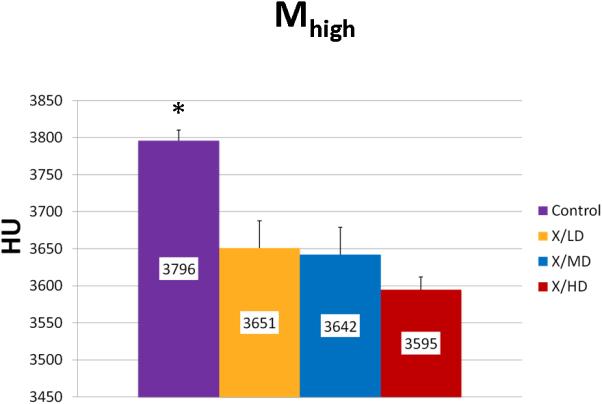

Mineralization Slope of Rise (Msor) and Mineralization Slope of Decline (Msod) are more specific indicators of diversity of mineralization before and after peak mineralization respectively, further, they also take into account the frequency of each mineralization. In general, steeper slopes are indicative of less diversity in mineralization and more concentration in a particularly smaller range of mineralization densities. This may represent a stunting of mineralization, and if taken together with a decreased overall volume (MTNV), a limitation of growth. Mineralization Low (Mlow) and Mineralization High (Mhigh) correspond to the 5th and 95th percentile of the whole curve represented as the HU's of mineralization at those values. In general these values represent the overall maturity and rate of turnover of a sample. For example a shift of Mlow to the right would be expected in processes of increased bone turnover and in cases where immature bone predominates. A shift to the left in Mhigh would be expected in processes bone turnover is hindered or in cases where mature mineral predominates.

RESULTS

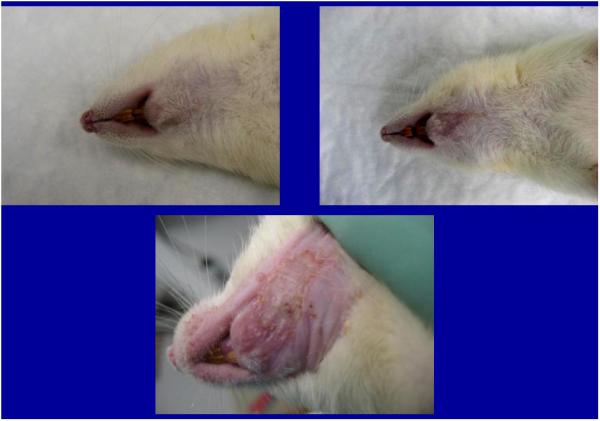

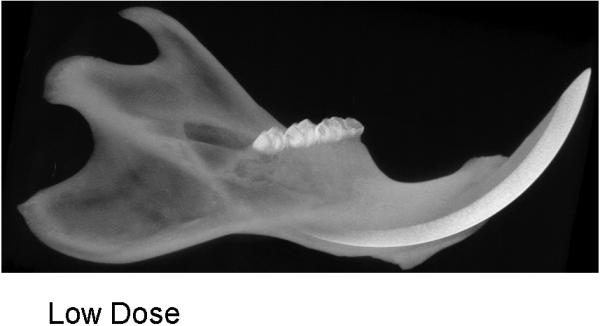

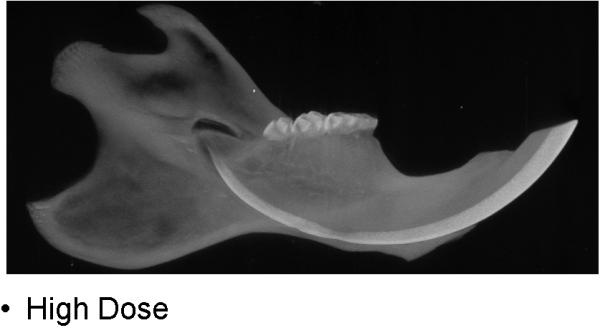

During the 56 days of recovery, one death occurred in the high dosage group. The middle and high dose XRT groups demonstrated signs of severe stress and alopecia (Figure 1). All animals had mucositis and weight loss in proportion to the XRT dose starting at post-radiation day four through eleven. Maximal weight lost from the pre-treatment weight was 8% (32 g) in the low dose, 15.8% (63 g) in the middle dose and 22.5% (90 g) in the high dose groups. All animals eventually gained weight and surpassed their pre-treatment weight. At time of harvest, the left hemi-mandibles were noticeably atrophied in proportion to dosages, with the high dose mandibles appearing nearly translucent. (Figure 2)

Figure 1.

Animals demonstrating dose-dependent alopecia

a. low dose

b. middle dose

c. high dose

Figure 2.

CT specimens demonstrating dose-dependent changes

a. low dose

b. middle dose

c. high dose

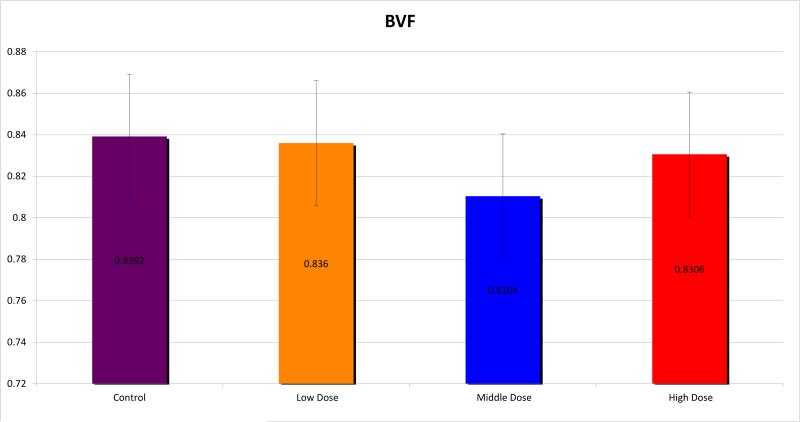

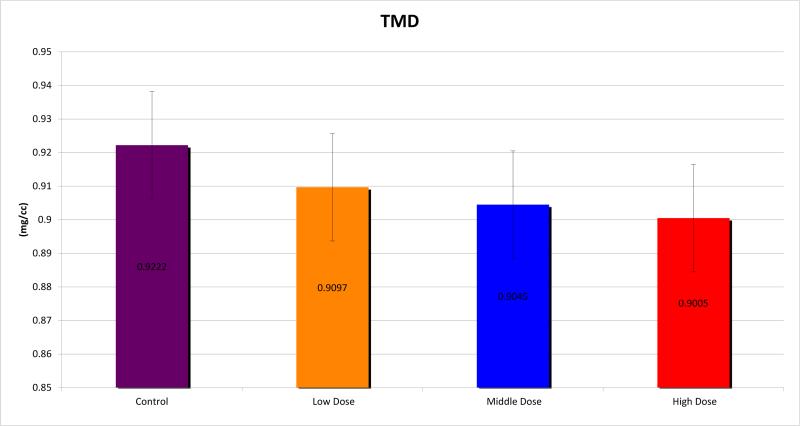

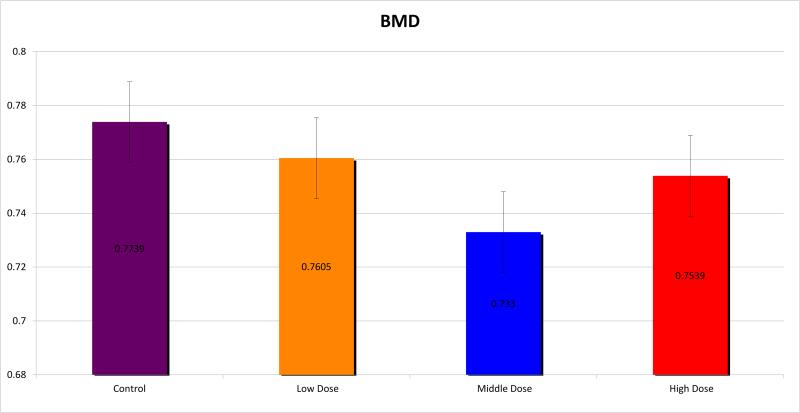

Micro CT analysis was undertaken and the mandibles were evaluated for BMD, TMD, BVF and histogram analysis or microdensitometry. Using standard micro-CT analysis, groups 1, 2 and 3 demonstrated TMD of 0.9097±0.016, 0.9045±0.012 and 0.9005±0.015 compared with 0.9222±0.009 for controls. (Figure 3) BMD was measured for the groups as 0.7605±0.040, 0.7330±0.018 and 0.7539±0.037 respectively, compared with 0.7739±0.015 for controls. (Figure 4) BVF was 0.8360±0.040, 0.8104±0.019 and 0.8306±0.057 compared with 0.8392±0.017 for controls. (Figure 5) Histogram analysis illustrated a diminution in both the low and highly mineralized bone illustrated by the decreased frequencies in the low and high HU's which results in a narrowing of the peak in the XRT samples reflecting a limitation in the range of possible mineral densities formed. Also revealed is a clear shift in the graphic representation of the bone density to the left with radiation compared to controls, diagrammatically illustrating that the radiated bone measured lower on the HU scale than controls. Furthermore, the peaks of the curves diminished with higher doses of radiation, with a larger difference seen between groups 1 and 2, than between groups 2 and 3. (Figure 6)

Figure 3.

Tissue Mineral Density (TMD)

Figure 4.

Bone Mineral Density (BMD)

Figure 5.

Bone Volume Fraction (BVF)

Figure 6.

Histogram demonstrating changes in mineralization patterns

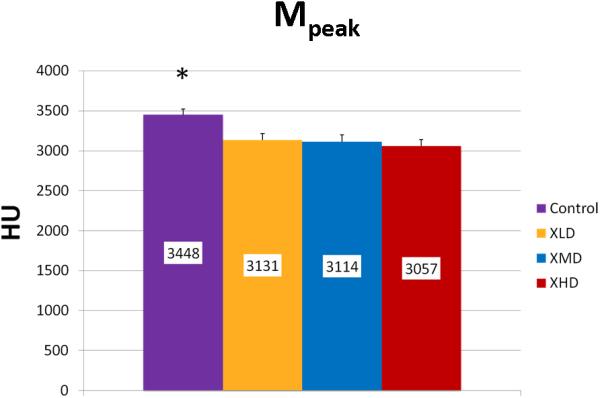

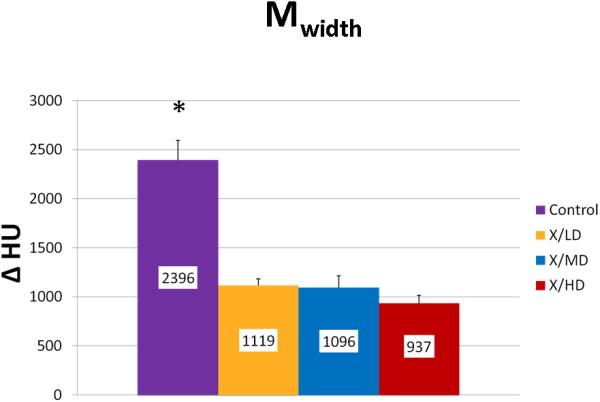

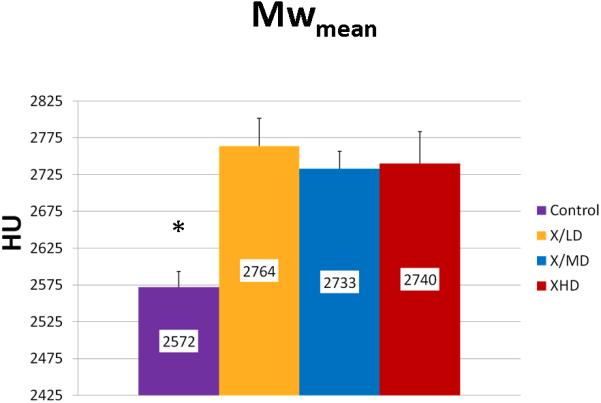

We observed statistically significant changes in Mineral Volume, Quality, and Maturity reflected by the calculated metrics between all irradiated groups and control. Radiation caused a significant depletion in Mineral Volume as reflected by MTNV, (Figure 7) in overall Mineral Quality as reflected by Mpeak, Mwidth, and Mwmean, (Figures 8, 9 and 10) and in Mineral Maturity as evidenced by differences in Msor, Msod, Mlow and Mhigh. (Figures 11, 12, 13 and 14) No statistically significant differences were found between the differing radiation dosages.

Figure 7.

Mineralization Total Number of Voxels (MTNV)

Figure 8.

Mineralization Peak (Mpeak)

Figure 9.

Mineralization Width (Mwidth)

Figure 10.

Mineralization Weighted Mean (Mwmean)

Figure 11.

Mineralization Slope of Rise (Msor)

Figure 12.

Mineralization Slope of Decline (Msod)

Figure 13.

Mineralization Low (Mlow)

Figure 14.

Mineralization High (Mhigh)

DISCUSSION

Radiation treatment for head and neck cancer severely attenuates bone healing, leading to a significant biomedical impediment and unforgiving sequelae, such as poor fracture and soft tissue healing, osteoradionecrosis and late pathologic fractures. However, little is known about the effects of XRT, at the doses used in head and neck cancer treatment, to the mandible, which often lies within the radiation field.

The linear-quadratic (LQ) formulation e−(αD+βD2) is often used to model specific tissues biological response to XRT. For instance, when applied to single fraction cell survival studies the surviving fraction (SF) is generally expressed as: SF = e−(αD+βD2) where D is the dose in Gray (Gy), α is the cell kill per Gy of the initial linear component (on a log-linear plot) and β the cell kill per Gy2 of the quadratic component of the survival curve. Curves for the individual LQ components e−αD and e−βD2intersect at the dose where the αD and βD2 components of cell killing are equal. This intersection happens to occur at a dose equal to the ratio of α to β, and is often referred to in the literature simply as α/β as it will be here. [12]

The biological effect (E) per fraction (n) of fractional dose (D) can be expressed as: En = (αD+βD2). The biologically effective dose (BED or E/α) is an approximate quantity by which different XRT fractionation regimens may be compared. For instance, for an external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) regimen employing n equal fractions of conventional size the BED will be: BED = E/α = nD (1 + (D / (α/β)))where n = number of fractions, D = dose/fraction, and nD = total dose.[15]

Thus, using the BED with appropriate α/β to compare differing fractionation schedules, a small animal model can be developed to specifically analyze the effect of human-equivalent doses of XRT on the underlying mandible. A high α/β ratio (i.e.10) is assigned to early-responding tissues (such as skin or mucosa) that are more susceptible to XRT injury. Conversely, late responding tissues, such as bone, have a lower α/β ratio (i.e.3). [15-17]

The total dose can be administered by various schedules, the more fractions used, the more the total delivered dose must be increased in order to obtain the same biologic effect. Conventional therapy for HNC involves the use of XRT with high energy X-rays with absorbed doses up to 70 Gy, delivered via a fraction size of 1.8-2Gy usually over 35 sessions. [18]

Indeed, modern radiation oncology has evolved to develop methods of dose delivery that would increase tumor control without increase in reactions in normal tissue or secondary targets. This has lead to the concept of fractionation scheme, total doses, timing of the initiation of radiotherapy and volume effects in normal tissue and tumors. However, XRT dose to the mandible is not routinely assessed in standard radiotherapy for HNC. Because bone proliferates slowly, it is less affected by XRT involving small fraction sizes or low total doses and is more susceptible to injury with increased fraction doses as is often used currently in most head and neck cancer protocols that strive to reduce the soft tissue adverse effects. [19, 20]

Previous studies in our laboratory examining XRT effects on the murine mandible have demonstrated biomechanical, histological and radiological changes consistent with a substantial influence of radiation on bone.[13, 14, 21-23] In Part I and Part II of this series our laboratory was able to demonstrate a dose dependent depletion of both osteogenic cells as well as biomechanical properties secondary to XRT.[13, 14] The purpose of this study was to determine a dose that would correlate with human cancer treatment and to investigate doses both above and below the target dose in order to identify measurable differences between radiated and non-radiated bone utilizing microCT analysis. Our global hypothesis is that XRT dosage and regimen are both critical and play a crucial role in bone healing properties.

In this study, we have successfully induced XRT damage with the application of a fractionated dosage regimen at levels approaching, equal to and greater than that received by humans undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer in a murine model of mandibular irradiation. Animals demonstrated clinically significant, dose dependent, worsening side effects of mucositis, alopecia, weight loss, and mandibular atrophy. Interestingly, although previous studies in our lab reported significant dose response in relation to histologic and cellular outcomes as well as measures of biomechanical breaking load and yield, traditional microCT parameters of BMD, TMD, and BVF, were not sensitive enough to demonstrate statistically significant differences between the radiated groups. Our findings in this regard could be due to a key difference in the way in which the mineralization process reacts to XRT in comparison to the other outcome metrics previously reported. These differences may well be temporally correlated or the small differences in traditional radiomorphometrics may have suffered from our small number of animals precluding us from reaching statistical significance. Either way we posit that this is a non-physiologic, short-term phenomenon that is likely to degrade over time as the long term insidious clinical consequences of radiation damage are undeniable. It was this puzzling outcome, however, that led us to further explore and mine our micro-CT data for clues to better understanding the radiation induced changes in mineralization. We elected to employ the analytical techniques of microdensitometry and BMDD in order to demonstrate radiation induced changes in mineralization that encompass and enhance conventional reporting of radiomorphometrics. Our efforts in this regard were fruitful as microdensitometric analysis via microCT derived histogram, did show clear dose dependent changes between radiated groups. Furthermore, BMDD analysis demonstrated statistically significant alterations in mineral volume, mineral quality, and mineral maturity, between radiated and non-radiated groups.

CONCLUSIONS

This set of experiments establishes a valuable analysis of fractionated XRT in a rodent model at doses equivalent to, and greater than that used for humans in the treatment of HNC. This study reports a dose-dependent deterioration of the clinically significant side effects of weight loss, alopecia, mucositis, and mandibular atrophy. This study also reports on the limited capacity of traditional micro-CT metrics to adequately capture key changes in bone composition and presents microdensitometric histogram analysis and Bone Mineral Density Distribution as a method to enhance conventional reporting of radiomorphometrics. These findings can now be utilized to develop therapies to remediate the effects of radiation on bone and measure the efficacy of such therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding was provided by the following grant: “Optimization of Bone Regeneration in the Irradiated Mandible,” NIH-R01#CA 125187-01; principal investigator, Steven R. Buchman, M.D. The authors thank Mary Davis, Dr. Avraham Eisbruch, and Dr. Ted Lawrence for providing their expert knowledge in radiation oncology.

Footnotes

Presented at Plastic Surgery 2009: American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) Annual Meeting in Seattle, Washington October 23-27, 2009

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Laura A. Monson, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA and University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

X. Lin Jing, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Alexis Donneys, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Aaron S. Farberg, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Steven R. Buchman, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vissink A, et al. Oral sequelae of head and neck radiotherapy. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14(3):199–212. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jereczek-Fossa BA, Orecchia R. Radiotherapy-induced mandibular bone complications. Cancer Treat Rev. 2002;28(1):65–74. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.2002.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marx RE. Osteoradionecrosis: a new concept of its pathophysiology. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41(5):283–8. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(83)90294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhuang Q, et al. Does radiation-induced fibrosis have an important role in pathophysiology of the osteoradionecrosis of jaw? Med Hypotheses. 2011;77(1):63–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenthal DI, et al. Beam path toxicities to non-target structures during intensity-modulated radiation therapy for head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72(3):747–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker JL, Jr., et al. Quantification of volumetric and geometric changes occurring during fractionated radiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer using an integrated CT/linear accelerator system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59(4):960–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang WB, et al. Bone regeneration after radiotherapy in an animal model. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(11):2802–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen M, et al. Animal model of radiogenic bone damage to study mandibular osteoradionecrosis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2011;32(4):291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie XT, et al. Experimental study of radiation effect on the mandibular microvasculature of the guinea pig. Chin J Dent Res. 1998;1(2):46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldman M. Ionizing radiation and its risks. West J Med. 1982;137(6):540–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz R, Hofmann W. Some comments on the concepts of dose and dose equivalent. Health Phys. 1984;47(4):603–11. doi: 10.1097/00004032-198410000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller-Runkel R, Vijayakumar S. Equivalent total doses for different fractionation schemes, based on the linear quadratic model. Radiology. 1991;179(2):573–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.179.2.2014314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tchanque-Fossuo CN, et al. Dose-response effect of human equivalent radiation in the murine mandible: Part II. A biomechanical assessment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(5):480e–487e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822b67ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tchanque-Fossuo CN, et al. Dose-response effect of human equivalent radiation in the murine mandible: part I. A histomorphometric assessment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(1):114–21. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31821741d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wollin M, Kagan AR, Norman A. Predicting normal tissue injury in radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21(5):1373–6. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90300-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nag S, Gupta N. A simple method of obtaining equivalent doses for use in HDR brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46(2):507–13. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00330-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fowler JF. 21 years of biologically effective dose. Br J Radiol. 2010;83(991):554–68. doi: 10.1259/bjr/31372149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chatterjee S, et al. Dosimetric and radiobiological comparison of helical tomotherapy, forward-planned intensity-modulated radiotherapy and two-phase conformal plans for radical radiotherapy treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Br J Radiol. 2011;84(1008):1083–90. doi: 10.1259/bjr/53812025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shibuya H. Current status and perspectives of brachytherapy for head and neck cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14(1):2–6. doi: 10.1007/s10147-008-0859-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thariat J, et al. New techniques in radiation therapy for head and neck cancer: IMRT, CyberKnife, protons, and carbon ions. Improved effectiveness and safety? Impact on survival? Anticancer Drugs. 2011;22(7):596–606. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328340fd2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fregene A, et al. Alteration in volumetric bone mineralization density gradation patterns in mandibular distraction osteogenesis following radiation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(4):1237–44. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b5a42f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarz DA, et al. Analysis of the biomechanical properties of the mandible after unilateral distraction osteogenesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(2):533–42. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181de2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarz DA, et al. Biomechanical assessment of regenerate integrity in irradiated mandibular distraction osteogenesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(2 Suppl):114S–22S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318191c5d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]