Abstract

Aim

To determine the burden and characteristics of fatal and hospitalised injuries among youth in Fiji.

Methods

We conducted a cross‐sectional analysis of the Fiji Injury Surveillance in Hospitals database – a prospective population‐based trauma registry – to examine the incidence and epidemiological characteristics associated with injury‐related deaths and hospital admissions among youth aged 15–24 years. The study base was Viti Levu, Fiji, during the 12‐month period concluding on 30 September 2006.

Results

One in four injuries in the Fiji Injury Surveillance in Hospitals database occurred among youth (n = 515, incidence rate 400/100 000). Injury rates were higher among men, those aged 20–24 years compared with 15‐ to 19‐year‐olds, and indigenous Fijians (iTaukei) compared with Indians. The leading causes among indigenous Fijians were being hit by a person/object (men) and falls (women), whereas for Indians, it was road traffic injuries (men) and intentional poisoning (women). Most injuries occurred at home (39%) or on the road (22%). Of the 63 fatal events, 57% were intentional injuries, and most deaths (73%) occurred prior to hospitalisation. Homicide rates were four times higher among indigenous Fijians than Indians, whereas suicide rates were five times higher among Indians compared with indigenous Fijians.

Conclusions

Important ethnic‐specific differences in the epidemiology of fatal and serious non‐fatal injuries are apparent among youth in Fiji. Efforts to prevent the avoidable burden of injury among Fiji youth thus requires inter‐sectoral cooperation that takes account of important sociocultural, environmental and health system factors such as unmet mental healthcare needs and effective pre‐hospital trauma services.

Keywords: accident, adolescent, developing country, Pacific Island, wound and injury

What is already known on this topic

Of the approximately five million injury deaths per annum, over 90% occur in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Youth aged 15 to 24 years account for 16% of injury fatalities worldwide, the commonest causes being road traffic injuries, self‐harm and violence.

Contemporary published literature on the overall epidemiology of injuries among youth living in the Pacific Islands is sparse.

What this paper adds

Youth aged 15–24 years account for a quarter of all injuries resulting in death or hospital admission in Viti Levu, Fiji.

Three‐quarters (73%) of the injury deaths in this age group occurred prior to hospital presentation.

Injury prevention efforts must take account of sociocultural factors that may account for important differences in the epidemiology of injuries in the two major ethnic groups with indigenous Fijian (iTaukei) youth having higher rates of injury overall and assault/homicide events while Indian youth having five times higher rates of self‐harm.

Of the 5.1 million injury‐related deaths reported worldwide, 16% occur in the 15‐ to 24‐year age group.1 Accounting for almost half (45%) of all deaths among adolescents and youth,2, 3 injuries are gaining long‐overdue global attention as a major public health problem for this age group.2, 4, 5, 6 This is of particular importance in low‐ and middle‐income countries, which experience over 90% of injury deaths,1 and where youth mortality rates (particularly among men) have been static or increasing over recent decades.7

Despite the disproportionate burden of injuries borne by youth in low‐ and middle‐income countries, injury prevention efforts in these settings are hindered by significant gaps in knowledge regarding associated epidemiological characteristics and contextual factors.8, 9 This places, these young people and their families at risk of being trapped in poverty, with adverse societal effects in terms of escalating health‐care costs and impacts on productivity and economic development.10

These are particularly acute challenges for vulnerable economies in the Pacific region where youth make up one‐fifth of the total population (1.6 million) in the 22 Pacific Island countries and territories. With the majority of these Pacific nations categorised as low‐ or middle‐income and a projected rapid increase in the youth population over the next two decades, proactive measures are required to ensure their health and wellbeing.11, 12, 13, 14

Research on the burden of injuries among youth in Pacific Island countries and territories has largely focussed on descriptive studies examining self‐harm and its attendant risks.15, 16, 17, 18 This reflects broader concerns regarding suicide rates in the Pacific region, which are among the highest in the world.19, 20, 21, 22, 23 To the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies from a less‐resourced Pacific Island country providing an epidemiological overview of all fatal and hospitalised injuries among youth. We considered such an overview as particularly important in Fiji, the second most populous Pacific Island country, as the country's ethnic composition could result in distinct and more complex injury profiles that require specific consideration in national injury prevention efforts. Viti Levu is the main island in Fiji and home to 70% of the Fiji population. In the 2007 census, youth aged 15–24 years (n = 130 000) made up one‐fifth of the Viti Levu population. Indigenous Fijians (iTaukei) and Indians comprised 55% and 39% of the youth population respectively.24

We conducted a secondary analysis of data gathered in a prospective population‐based surveillance system to quantify the incidence‐associated epidemiological characteristics of fatal and hospitalised injuries among youth aged 15 to 24 years in Viti Levu. This analysis complements the information previously published on the epidemiology of childhood injuries in Fiji.25

Methods

The Fiji Injury Surveillance in Hospitals (FISH) database was a study‐specific prospective trauma registry established in all trauma‐admitting hospitals in Viti Levu, Fiji, as part of the traffic‐related injury in the Pacific (TRIP) research project. Using a methodology previously described26 and a pre‐defined set of variables recommended by the World Health Organization injury surveillance guidelines,27 the FISH database recorded information on the demographic and associated characteristics of injury deaths and hospital admissions for 12 h or more, over a 12‐month period up to 30 September 2006. Eligible cases were identified from hospital accident and emergency registers, admission records and mortuary registers. Data recorded included: the reported intent and mechanism of injury, nature of the principal injury, activity and location of injury, circumstances (conflict situation, leisure/play/sport, travel, work, other) and the clinical outcome (fatal, non‐fatal). The variable ‘circumstances’ related to the particular activity the injured person was engaged in or exposed to at the time of the injury. A conflict situation was defined as a disagreement (verbal or physical) with another person and/or a situation consistent with a significant psychological stressor.

We also sought data on the use of alcohol, kava (a root plant with anxiolytic and sedative properties commonly consumed in Fiji)28, 29 and other substances, in the 6 h prior to the injury. Cases eligible for analysis in this study were all injury presentations in the FISH database of youth aged 15 to 24 years.

We analysed data using Microsoft® Excel Version 2010, and STATA® Version 12 statistical software. Population data from the Fiji census (2007)24 was used to estimate injury incidence rates. This study was approved by the Fiji National Research Ethics Review Committee of the Ministry of Health.

Results

The 515 injury events among youth aged 15–24 years accounted for 24% of all injuries recorded in the FISH database, and an annual injury incidence rate for youth of 400/100 000 population. The major causes of injury were being hit by a person or object (27%), falls (18%), road traffic injury (RTI) (17%) and poisoning (13%). Intentional injuries (self‐harm or interpersonal violence) accounted for 36% of injuries. Common types of injury were fractures (32%), cuts/open wounds (22%) and head injuries (11%). Most injuries occurred in homes (39%), highways/roads (22%) and recreational areas (14%). Although 14% and 3% of youth reported consuming alcohol and kava, respectively within 6 h of the injury, the high rate of missing information (20% and 26% respectively) made it difficult to interpret these results.

Injury profiles by age group and ethnicity

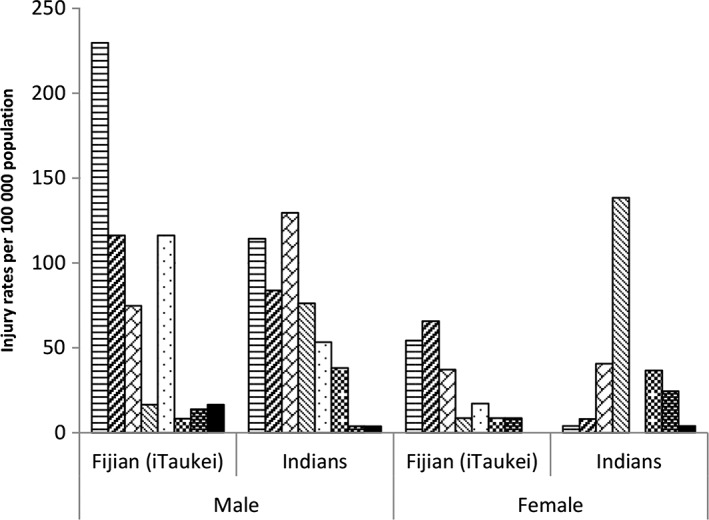

In general, injury rates were higher among older youth (20 to 24 years) compared with those aged 15 to 19 years and twice as high among men compared with women (Table 1). While overall injury rates were higher among indigenous Fijians compared with Indians, there were important ethnic‐specific differences. Injuries arising from ‘leisure, play, or sporting activities’ were more common among indigenous Fijians, compared with a ‘conflict situation’ among Indians. The rate of self‐harm was five times higher among Indians while interpersonal violence‐related injury was four times higher among indigenous Fijians. The leading causes of injury for indigenous Fijian men were being hit by a person or object, falls and stabs/cuts. Among Indian men, these were RTI, being hit by a person or object and falls (Fig. 1). Poisonings were the commonest cause among Indian women, while falls and being hit by a person/object were leading causes among indigenous Fijian women.

Table 1.

Incidence rates (per 100 000) of fatal and hospitalised injuries by age and ethnicity (1 October 2005–30 September 2006)

| Demographic and injury characteristics | Age group | Ethnic group | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–19 years (n = 196) | 20–24 years (n = 319) | Fijian (iTaukei) (n = 293) | Indian (n = 197) | ||||||||||

| n | Rate | (95% CI) | n | Rate | (95% CI) | n | Rate | (95% CI) | n | Rate | (95% CI) | ||

| Total | 196 | 311.9 | (268.3–355.6) | 319 | 482.1 | (429.2–535.0) | 293 | 411.9 | (364.7–459.1) | 197 | 387.7 | (333.5–441.8) | |

| Sex | Male | 140 | 434.2 | (362.3–506.2) | 230 | 680.6 | (592.6–768.5) | 219 | 606.0 | (525.8–686.3) | 133 | 506.6 | (420.5–592.7) |

| Female | 56 | 183.1 | (135.1–231.0) | 89 | 274.9 | (217.8–332.0) | 74 | 211.5 | (163.3–259.6) | 64 | 260.6 | (196.7–324.4) | |

| Age (years) | 15–19 | 120 | 334.0 | (274.2–393.8) | 67 | 285.0 | (216.7–353.2) | ||||||

| 20–24 | 173 | 491.4 | (418.2–564.7) | 130 | 476.1 | (394.3–557.9) | |||||||

| Intent | Unintentional | 128 | 203.7 | (168.4–239.0) | 183 | 276.6 | (236.5–316.6) | 192 | 269.9 | (231.7–308.1) | 104 | 204.7 | (165.3–244.0) |

| Intentional | 64 | 101.9 | (76.9126.8) | 120 | 181.4 | (148.9–213.8) | 90 | 126.5 | (100.4–152.7) | 85 | 167.3 | (131.7–202.8) | |

| Interpersonal violence | 23 | 36.6 | (21.6–51.6) | 66 | 99.7 | (75.7–123.8) | 71 | 99.8 | (76.6–123.0) | 14 | 27.6 | (13.1–42.0) | |

| Self‐harm | 41 | 65.3 | (45.3–85.2) | 54 | 81.6 | (59.8–103.4) | 19 | 26.7 | (14.7–38.7) | 71 | 139.7 | (107.2–172.2) | |

| Cause of injury | Hit by person or object | 43 | 68.4 | (48.0–88.9) | 95 | 143.6 | (114.7–172.4) | 102 | 143.4 | (115.6–171.2) | 31 | 61.0 | (39.5–82.5) |

| Fall | 49 | 78.0 | (56.2–99.8) | 48 | 72.5 | (52.0–93.1) | 65 | 91.4 | (69.2–113.6) | 24 | 47.2 | (28.3–66.1) | |

| Road traffic injury | 25 | 39.8 | (24.2–55.4) | 62 | 93.7 | (70.4–117.0) | 40 | 56.2 | (38.8–73.7) | 44 | 86.6 | (61.0–112.2) | |

| Poisoning | 28 | 44.6 | (28.1–61.1) | 38 | 57.4 | (39.2–75.7) | 9 | 12.7 | (4.4–20.9) | 54 | 106.3 | (77.9–134.6) | |

| Stab/cut | 21 | 33.4 | (19.1–47.7) | 42 | 63.5 | (44.3–82.7) | 48 | 67.5 | (48.4–86.6) | 14 | 27.6 | (13.1–42.0) | |

| Choking/hanging | 11 | 17.5 | (7.2–27.9) | 16 | 24.2 | (12.3–36.0) | 6 | 8.4 | (1.7–15.2) | 19 | 37.4 | (20.6–54.2) | |

| Drowning | 7 | 11.1 | (2.9–19.4) | 3 | 4.5 | (0.0–9.7) | 6 | 8.4 | (1.7–15.2) | 2 | 3.9 | (0.0–9.4) | |

| Nature of injury | Fracture | 62 | 98.7 | (74.1–123.2) | 102 | 154.2 | (124.2–184.1) | 97 | 136.4 | (109.2–163.5) | 56 | 110.2 | (81.3–139.1) |

| Cut/bite, open wound | 39 | 62.1 | (42.6–81.6) | 76 | 114.9 | (89.0–140.7) | 90 | 126.5 | (100.4–152.7) | 22 | 43.3 | (25.2–61.4) | |

| Head injury/concussion | 17 | 27.1 | (14.2–39.9) | 41 | 62.0 | (43.0–80.9) | 37 | 52.0 | (35.3–68.8) | 21 | 41.3 | (23.7–59.0) | |

| Asphyxia | 17 | 27.1 | (14.2–39.9) | 17 | 25.7 | (13.5–37.9) | 12 | 16.9 | (7.3–26.4) | 19 | 37.4 | (20.6–54.2) | |

| Sprain/strain/dislocation/bruise | 18 | 28.6 | (15.4–41.9) | 24 | 36.3 | (21.8–50.8) | 28 | 39.4 | (24.8–53.9) | 12 | 23.6 | (10.3–37.0) | |

| Circumstance | Conflict situation | 45 | 71.6 | (50.7–92.5) | 99 | 149.6 | (120.1–179.1) | 66 | 92.8 | (70.4–115.2) | 70 | 137.8 | (105.5–170.0) |

| Leisure/play/sport | 85 | 135.3 | (106.5–164.0) | 72 | 108.8 | (83.7–133.9) | 111 | 156.1 | (127.0–185.1) | 38 | 74.8 | (51.0–98.6) | |

| Travel | 27 | 43.0 | (26.8–59.2) | 69 | 104.3 | (79.7–128.9) | 52 | 73.1 | (53.2–93.0) | 41 | 80.7 | (56.0–105.4) | |

| Work | 27 | 43.0 | (26.8–59.2) | 51 | 77.1 | (55.9–98.2) | 49 | 68.9 | (49.6–88.2) | 26 | 51.2 | (31.5–70.8) | |

| Other/unknown | 12 | 19.1 | (8.3–29.9) | 28 | 42.3 | (26.6–58.0) | 15 | 21.1 | (10.4–31.8) | 22 | 43.3 | (25.2–61.4) | |

Figure 1.

Fiji youth injury rates per 100 000 population, by cause, sex and ethnic group. ( ), Hit by person or object; (

), Hit by person or object; ( ), fall; (

), fall; ( ), road trafic injury; (

), road trafic injury; ( ), poisoning; (

), poisoning; ( ), stab/cut; (

), stab/cut; ( ), choking/hanging; (

), choking/hanging; ( ), fire/heat/electricity; (

), fire/heat/electricity; ( ), drowning.

), drowning.

Fatal injuries

Twelve per cent (n = 63) of injury events were fatal, and almost three‐quarters (n = 46) of these deaths occurred before hospital admission. Among indigenous Fijians, fatal injuries were more common among men while no gender difference was apparent among Indians (Table 2). Two‐thirds of all fatalities occurred in the 20‐ to 24‐year age group, most of whom were Indians. The majority of fatalities were intentional (57%) with a high proportion among Indian youth (70%), largely because of self‐harm. While choking/hanging and RTI were the leading causes of injury deaths among indigenous Fijian and Indian youth, drowning was also an important cause among indigenous Fijians.

Table 2.

Frequency of fatal and non‐fatal hospitalised injuries among Fiji youth, by ethnic group (1 October 2005–30 September 2006)

| Non‐fatal hospitalised injuries (n = 452) | Fatal injuries (n = 63) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 452) | Fijian (iTaukei) (n = 272) | Indian (n = 160) | Total (n = 63) | Fijian (iTaukei) (n = 21) | Indian (n = 37) | ||

| Sex | Male | 334 (73.9) | 205 (75.4) | 114 (71.3) | 36 (57.1) | 14 (66.7) | 19 (51.4) |

| Female | 118 (26.1) | 67 (24.6) | 46 (28.8) | 27 (42.9) | 7 (33.3) | 18 (48.7) | |

| Age (years) | 15–19 | 174 (38.5) | 109 (40.1) | 58 (36.2) | 22 (34.9) | 11 (52.4) | 9 (24.3) |

| 20–24 | 278 (61.5) | 163 (59.9) | 102 (63.8) | 41 (65.1) | 10 (47.6) | 28 (75.7) | |

| Intent | Unintentional | 286 (63.3) | 179 (65.8) | 94 (58.8) | 25 (39.7) | 13 (61.9) | 10 (27.0) |

| Intentional | 148 (32.7) | 83 (30.5) | 59 (36.9) | 36 (57.1) | 7 (33.3) | 26 (70.3) | |

| Interpersonal violence | 88 (19.5) | 70 (25.7) | 14 (8.8) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (4.8) | 0 | |

| Self‐harm | 60 (13.3) | 13 (4.4) | 45 (28.1) | 35 (55.6) | 6 (28.6) | 26 (70.3) | |

| Undetermined/unknown | 18 (4.0) | 10 (3.4) | 7 (4.4) | 2 (3.2) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.7) | |

| Cause | Hit by person or object | 137 (30.3) | 101 (37.1) | 31 (19.4) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (4.8) | 0 |

| Fall | 95 (21.0) | 63 (23.2) | 24 (15.0) | 2 (3.2) | 2 (9.5) | 0 | |

| Road traffic injury | 74 (16.4) | 35 (12.9) | 36 (22.5) | 13 (20.6) | 5 (23.8) | 8 (21.6) | |

| Poisoning | 60 (13.3) | 9 (3.3) | 50 (31.3) | 6 (9.5) | 0 | 4 (10.8) | |

| Stab/cut | 62 (13.7) | 48 (17.7) | 13 (8.1) | 1 (1.6) | 0 | 1 (2.7) | |

| Choking/hanging | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 25 (39.7) | 6 (28.6) | 18 (48.7) | |

| Fire/heat/electrical | 10 (2.2) | 7 (2.6) | 3 (1.9) | 5 (7.9) | 1 (4.8) | 4 (10.8) | |

| Drowning | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 (15.9) | 6 (28.6) | 2 (5.4) | |

| Sexual assault, other, unknown | 12 (2.7) | 9 (3.3) | 2 (1.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Circumstance | Conflict situation | 117 (25.9) | 61 (22.4) | 51 (31.9) | 27 (42.9) | 5 (23.8) | 19 (51.4) |

| Leisure/play/sport | 147 (32.5) | 105 (38.6) | 36 (22.5) | 10 (15.9) | 6 (28.6) | 2 (5.4) | |

| Travel | 83 (18.4) | 46 (16.9) | 34 (21.3) | 13 (20.6) | 6 (28.6) | 6 (18.9) | |

| Work | 75 (16.6) | 46 (16.9) | 26 (16.3) | 3 (4.8) | 3 (14.3) | 0 | |

| Other/unknown | 30 (6.6) | 14 (5.2) | 13 (8.1) | 10 (15.9) | 1 (4.8) | 9 (24.3) | |

| Location | Private house/compound | 162 (35.8) | 80 (29.4) | 73 (45.6) | 36 (57.1) | 8 (38.1) | 25 (67.6) |

| Highway/road | 98 (21.7) | 58 (21.3) | 36 (22.5) | 14 (22.2) | 6 (28.6) | 8 (21.6) | |

| Area of recreation | 65 (14.4) | 52 (19.1) | 11 (6.9) | 5 (7.9) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (2.7) | |

| School | 18 (4.0) | 14 (5.2) | 4 (2.5) | 1 (1.6) | 0 | 1 (2.7) | |

| Work place | 52 (11.5) | 31 (11.4) | 19 (11.9) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (4.8) | 0 | |

| Other | 17 (3.8 | 12 (4.4) | 5 (3.1) | 4 (6.4) | 3 (14.3) | 1 (2.7) | |

| Unknown | 40 (8.9) | 25 (9.2) | 12 (7.5) | 2 (3.2) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.7) | |

| Nature | Fracture | 161 (35.6) | 94 (34.6) | 56 (35.0) | 3 (4.8) | 3 (14.3) | 0 |

| Cut/bite, open wound | 114 (25.2) | 90 (33.1) | 21 (13.1) | 1 (1.6) | 0 | 1 (2.7) | |

| Head injury/concussion | 48 (10.6) | 33 (12.1) | 15 (9.4) | 10 (15.9) | 4 (19.1) | 6 (16.2) | |

| Asphyxia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 (54.0) | 12 (57.1) | 19 (51.4) | |

| Sprain/strain/dislocation/bruise | 42 (9.3) | 28 (10.3) | 12 (7.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Burn | 7 (1.6) | 4 (1.5) | 3 (1.9) | 5 (7.9) | 1 (4.8) | 4 (10.8) | |

| Internal injuries chest/abdomen | 8 (1.8) | 4 (1.5) | 3 (1.9) | 3 (4.8) | 0 | 2 (5.4) | |

| Other/unknown | 72 (15.9) | 19 (7.0) | 50 (31.3) | 7 (11.1) | 1 (4.8) | 5 (13.5) | |

Non‐fatal hospital admissions

One‐third of non‐fatal injuries were deemed intentional with interpersonal violence being more common among indigenous Fijians and self‐harm more common among Indians (Table 2). Indigenous Fijian youth were more commonly injured after being hit by a person/object or falling, sustained most injuries at home, on the road and recreational areas, with the circumstances of injury most commonly attributed to leisure, play and sporting activities. In contrast, Indian youth were more commonly injured from poisoning and RTI.

Discussion

In this population‐based study from Fiji, youth aged 15 to 24 years accounted for one in four serious injuries resulting in death or hospital admission for 12 h or more. In general, injury rates were higher among men and older youth. Indigenous Fijians had higher overall rates of injury (i.e. deaths and hospital admissions combined) but Indians had higher rates of fatal injury. Among indigenous Fijians, injured men were most commonly hit by a person/object while women were injured in falls. Among Indians, men were most often injured in road crashes while (intentional) poisoning comprised the commonest injury among women. Most fatal injury events occurred at home, and three‐quarters of injury deaths occurred prior to hospital admission. Almost two‐thirds of fatal injuries were intentional, the majority of which were due to self‐harm among Indians. Rates of youth suicide among Indians were five times that of indigenous Fijians.

The prospective trauma registry established as part of the wider TRIP project in Viti Levu, Fiji, provided a unique opportunity to investigate the population‐based epidemiology of life‐threatening injuries among youth. By including data from mortuaries as well as all trauma‐admitting hospitals, the study also addressed some common biases in hospital or trauma centre‐based studies, which do not typically capture data on pre‐hospital deaths and deny the opportunity to estimate population‐based incidence of injury. Applying this approach in Fiji helped distinguish ethnic‐specific differences in the epidemiology of serious injuries among Fiji youth.

Notwithstanding these strengths, our findings must be interpreted in light of several limitations. The precision of the estimates is limited by the relatively small size of the population base, and the limited period of FISH data collection (12 months). The latter also precluded the ability to examine year to year variations and trends over time. While a standardised quality‐assured data collection method was employed using World Health Organization guidelines for less‐resourced settings,26, 30 the data accessible from clinical records precluded an analysis of details such as the types of road users involved in RTI or degrees of exposure to environmental hazards. Furthermore, while we generated a broad profile of injuries resulting in death or hospital admissions for 12 h or more (most serious injuries are considered likely to present to hospitals in Fiji), less severe injuries (in terms of immediate threat to life) were outside the scope of this study. Injuries that are not life threatening are more common in the community and can result in disabling consequences, substantial out‐of‐pocket costs and attendant stresses to young people and their families.

The high rate of interpersonal violence among indigenous Fijians in this study is similar to findings from a population‐based self‐report survey of students aged 14 to 17 years in three Pacific Islands (Pohnpei, Tonga, Vanuatu) in which 24 to 62% of participants reported experiencing intentional physical injuries (by implication, these referred to interpersonal violence) in the preceding 12 months.31 Factors associated with these injuries included school bullying and the use of tobacco (Tonga, Vanuatu) and illicit drugs (Pohnpei, Vanuatu).

The high rates of fatalities by choking or hanging among Indians in this study is consistent with previous studies focussing on suicide in Fiji.17, 32 In a comparative study of suicides in Pacific Island countries and territories, the highest rates were observed in youth from Fiji of Indian ethnicity, the Chuuk State of the Federated States of Micronesia, Samoa and Guam, with overall rates higher among men, except among Fiji‐Indian and Samoan women.32 The preponderance of injuries occurring in the home environment also reflects a high proportion of self‐harm events in this setting, a finding consistent with a study examining Pacific youth suicide in Auckland, New Zealand.33

Our study was not designed to explore the specific circumstances surrounding injuries, such as those occurring in the context of sport and recreation, violence or self‐harm among Fiji youth. However, our findings alongside the existing literature reveal the need to explore the complex sociocultural, geopolitical, intergenerational and environmental factors that require attention to address this avoidable mortality.22, 31, 32, 34, 35 It has been reported that a high proportion of children in Fiji experience direct physical punishment in Fiji,36 a factor that could be associated with injuries relating to interpersonal violence.35 Other researchers attribute the high rates of suicides among young Indians to intergenerational and family conflicts relating to peer relationships and marriage.17, 37 While the specific sociocultural contexts and other associated characteristics may vary among both indigenous Fijian and Indian communities, the roles that parents, families and caring adults could play in interrupting cycles of inter‐ and intrapersonal violence require greater attention. Furthermore, the availability and access to culturally appropriate, youth‐friendly, mental health and counselling services should be a high priority. These are aspects of health care which have historically been poorly resourced in the Pacific Islands.17, 19, 22 Given most injury deaths (74%) occurred prior to hospital admission, access to high quality pre‐hospital care and emergency response services also requires urgent attention.

Findings regarding RTIs are generally consistent with studies from Papua New Guinea and the Pacific region in terms of the high proportion of young male crash victims and pre‐hospital deaths.38 The relatively low number of workplace injuries while possibly reflecting a lower youth employment rate in these settings requires further investigation. Similarly, for indigenous Fijians, serious injuries in the context of sport and recreation would benefit from context‐appropriate evidence‐based preventative measures.

Previous studies of RTIs and self‐harm in the Pacific suggest alcohol to be an important contributor, especially among injuries involving young men.22, 38, 39 Harm reduction approaches are likely to be challenged by the sale, supply and availability of alcohol in poorly regulated environments in the Pacific Islands. Some international regulatory authorities have cautioned against consuming kava or products containing kava and driving or using heavy machinery, but the associations involved require more rigorous evaluation, particularly in contexts where recreational consumption of kava is common.40

Conclusion

Despite the disproportionate burden of injury borne by youth in low‐ and middle‐income countries, there are remarkable gaps in infrastructure and service investment in youth health, social, educational and economic policies in these settings.8, 9 The complex sociopolitical issues confronting small Pacific Island nations compound the perils of neglect for youth in these settings. National and regional efforts should focus on culturally appropriate injury control interventions that take account of underlying determinants and stresses experienced by vulnerable youth in Pacific Islands, while also drawing on their sources of strength and resilience.6, 17, 32, 41 Periodic community surveys of key risk and protective factors for injury could usefully inform context‐specific prevention initiatives.42, 43, 44 Effective injury and risk factor surveillance systems can also serve as vital monitoring instruments to evaluate the impact of interventions designed to reduce premature death, morbidity and disability among Pacific youth.10, 18 This study highlights the need for intersectoral efforts that achieve these objectives as a regional health priority.

Although the data were collected a decade ago, our study has added critical injury information not previously available to Fiji and the Pacific region. To our knowledge, there have been no major changes in the epidemiology of injuries because the collection of these data and the rates of fatal injury events for this age group captured by the Fiji Ministry of Health have remained relatively constant. Consequently, this study continues to inform current Pacific Island country road safety initiatives including the Cook Islands Road Safety Strategy 2016–2020 and the World Health Organization Regional Action Plan for Violence and Injury Prevention in the Western Pacific (2016–2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by an international collaborative research grant awarded by the Wellcome Trust of the United Kingdom (GR071671AIA) and the Health Research Council of New Zealand (04/498).

The authors acknowledge the support of the Fiji Ministry of Health including the former Permanent Secretary Dr Lepani Waqatakirewa, Fiji Police Force and Land Transport Authority, and all staff and students of the Fiji Medical School. We gratefully acknowledge members of the TRIP project team including Professor Rod Jackson, Professor Sitaleki Finau, Dr Robyn McIntyre, Asilika Naisaki, Mabel Taoi, Ravi Reddy, Ramneek Goundar, Litia Vuniduvu and Nola Vanualailai.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380: 2095–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blum RW, Nelson‐Mmari K. The health of young people in a global context. J. Adolesc. Health 2004; 35: 402–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K et al Global and Regional Mortality from 235 Causes of Death for 20 Age Groups in 1990 and 2010: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010 [Appendix]. Available from: http://www.healthmetricsandevaluation.org/publications/research‐articles [accessed 24 April 2013]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. Krug EG, Sharma GK, Lozano R. The global burden of injuries. Am. J. Public Health 2000; 90: 523–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC et al. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2011; 377: 2093–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization . Health for the World's Adolescents – A Second Chance in the Second Decade. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Viner RM, Coffey C, Mathers C et al. 50‐year mortality trends in children and young people: A study of 50 low‐income, middle‐income, and high‐income countries. Lancet 2011; 377: 1162–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patton GC, Coffey C, Cappa C et al. Health of the world's adolescents: A synthesis of internationally comparable data. Lancet 2012; 379: 1665–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM et al. Global patterns of mortality in young people: A systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2009; 374: 881–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chandran A, Hyder AA, Peek‐Asa C. The global burden of unintentional injuries and an agenda for progress. Epidemiol. Rev. 2010; 32: 110–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Secretariat of the Pacific Community . Table 4: Population by Sex and 5-year Age-groups, at the Two Most Recent Censuses. Statistics for Development 2012. Available from: http://www.spc.int/sdp/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat_view&gid=104&Itemid=&lang=en [accessed 3 May 2013].

- 12. Bedford R, Hugo G. Population Movement in the Pacific: A Perspective on Future Prospects. Wellington: Labour and Immigration Research Centre, New Zealand Department of Labour, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goodburn EA, Ross DA. Young people's health in developing countries: A neglected problem and opportunity. Health Policy Plan. 2000; 15: 137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mayer PA, Bauman KA. Health practices, problems, and needs in a population of Micronesian adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health Care 1986; 7: 338–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pinhey TK, Millman SR. Asian/Pacific Islander adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk in Guam. Am. J. Public Health 2004; 94: 1204–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rubinstein DH. Epidemic suicide among Micronesian adolescents. Soc. Sci. Med. 1983; 17: 657–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grambeau M. Causes and Perceptions: An Exploratory Study of Suicide in Indo-Fijian and Fijian Youth. Available from: http://digitalcollections.sit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1207&context=isp_collection [accessed 25 April 2013].

- 18. Lippe J, Brener ND, Kann L et al Youth risk behaviour surveillance – Pacific Island United States Territories, 2007. MMWR CDC surveillance summaries : Morbidity and mortality weekly report CDC surveillance summaries/Centers for Disease Control 2008; 57 (SS12): 28–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baravilala W. Suicide in the Pacific – a mental health epidemic. Pac. Health Dialog 2001; 8: 4–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pridmore S, Lawler A, Couper D. Hanging and poisoning autopsies in Fiji. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 1996; 30: 685–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hezel FX. Cultural patterns in Trukese suicide. Ethnology 1984; 23: 193–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bourke T. Suicide in Samoa. Pac. Health Dialog 2001; 8: 213–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bridges FS. Social integration and suicide in the Western Pacific Islands. Psychol. Rep. 2008; 102: 683–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fiji Islands Bureau of Statistics . Fiji 2007 Census of Population and Housing. Available from: http://www.statsfiji.gov.fj/ [accessed 30 April 2010].

- 25. Naisaki A, Wainiqolo I, Kafoa B et al. Fatal and hospitalised childhood injuries in Fiji (TRIP Project‐3). J. Paediatr. Child Health 2013; 49: 63–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wainiqolo I, Kafoa B, McCaig E, Kool B, McIntyre R, Ameratunga S. Development and piloting of the Fiji Injury Surveillance in Hospitals System (TRIP Project‐1). Injury 2013; 44: 126–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holder Y, Peden M, Krug E, Lund J, Gururaj G, Kobusingye O. Injury Surveillance Guidelines. Geneva: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta and World Health Organization, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wheatley D. Medicinal plants for insomnia: a review of their pharmacology, efficacy and tolerability. J. Psychopharmacol. 2005; 19: 414–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pittler MH, Ernst E. Kava extract for treating anxiety. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003; 1: CD003383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wainiqolo I, Kafoa B, Kool B, Herman J, McCaig E, Ameratunga S. A profile of injury in Fiji: Findings from a population–based injury surveillance system (TRIP‐10). BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith BJ, Phongsavan P, Bampton D et al. Intentional injury reported by young people in the Federated States of Micronesia, Kingdom of Tonga and Vanuatu. BMC Public Health 2008; 8: 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Booth H. Pacific Island suicide in comparative perspective. J. Biosoc. Sci. 1999; 31: 433–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tiatia J, Coggan C. Young Pacifican suicide attempts: A review of emergency department medical records, Auckland, New Zealand. Pac. Health Dialog 2001; 8: 124–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Milner A, De Leo D. Suicide research and prevention in developing countries in Asia and the Pacific. Bull. World Health Organ. 2010; 88: 795–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pridmore S, Ryan K, Blizzard L. Victims of violence in Fiji. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 1995; 29: 666–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Save the Children Fiji . The Physical and Emotional Punishment of Children in Fiji: A Research Report. Suva: Save the Children Fiji, 2006.

- 37. Haynes RH. Suicide in Fiji: A preliminary study. Br. J. Psychiatry 1984; 145: 433–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Herman J, Ameratunga S, Jackson R. Burden of road traffic injuries and related risk factors in low and middle‐income Pacific Island countries and territories: A systematic review of the scientific literature (TRIP 5). BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Herman J, Ameratunga S, Wainiqolo I, Kafoa B, McCaig E, Jackson R. The case for improving road safety in Pacific Islands: A population‐based study from Fiji (TRIP 6). Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2012; 36: 427–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wainiqolo I, Kool B, Nosa V, Ameratunga S. Is driving under the influence of kava associated with motor vehicle crashes? A systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2015; 39: 495–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hezel FX. Truk suicide epidemic and social change. Hum. Organ. 1987; 46: 283–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Corner H, Rissel C, Smith B et al. Sexual health behaviours among Pacific Island youth in Vanuatu, Tonga and the Federated States of Micronesia. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2005; 16: 144–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Phongsavan P, Olatunbosun‐Alakija A, Havea D et al. Health behaviour and lifestyle of Pacific youth surveys: A resource for capacity building. Health Promot. Int. 2005; 20: 238–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smith BJ, Phongsavan P, Bauman AE, Havea D, Chey T. Comparison of tobacco, alcohol and illegal drug usage among school students in three Pacific Island societies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007; 88: 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]