Significance

Local protein synthesis is a highly used mechanism to create functional asymmetries within cells. It underlies diverse biological processes, including the development and function of the nervous and reproductive systems. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding (CPEB) proteins regulate local translation in early development, synaptic plasticity, and long-term memory. However, their binding specificity is not fully resolved. We used a transcriptome-wide approach and established that Drosophila representatives of two CPEB subfamilies, Orb and Orb2, regulate largely overlapping target mRNAs by binding to CPE-like sequences in their 3′ UTRs, potentially with a shift in specificity for motif variants. Moreover, our data suggest that a subset of these mRNAs is translationally regulated and involved in long-term memory.

Keywords: CPEB, CLIP, Orb2, translation, long-term memory

Abstract

Localized protein translation is critical in many biological contexts, particularly in highly polarized cells, such as neurons, to regulate gene expression in a spatiotemporal manner. The cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding (CPEB) family of RNA-binding proteins has emerged as a key regulator of mRNA transport and local translation required for early embryonic development, synaptic plasticity, and long-term memory (LTM). Drosophila Orb and Orb2 are single members of the CPEB1 and CPEB2 subfamilies of the CPEB proteins, respectively. At present, the identity of the mRNA targets they regulate is not fully known, and the binding specificity of the CPEB2 subfamily is a matter of debate. Using transcriptome-wide UV cross-linking and immunoprecipitation, we define the mRNA-binding sites and targets of Drosophila CPEBs. Both Orb and Orb2 bind linear cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-like sequences in the 3′ UTRs of largely overlapping target mRNAs, with Orb2 potentially having a broader specificity. Both proteins use their RNA-recognition motifs but not the Zinc-finger region for RNA binding. A subset of Orb2 targets is translationally regulated in cultured S2 cells and fly head extracts. Moreover, pan-neuronal RNAi knockdown of these targets suggests that a number of these targets are involved in LTM. Our results provide a comprehensive list of mRNA targets of the two CPEB proteins in Drosophila, thus providing insights into local protein synthesis involved in various biological processes, including LTM.

Local protein translation restricts protein synthesis to specific cellular domains. This mechanism of gene-expression regulation is essential for many biological processes, including the production of gametes (1), animal development (2, 3), and maintaining tissue polarity in adult organisms (2, 4). In the nervous system local protein synthesis is critical for the development of highly polarized cells such as neurons (5) and is necessary for dynamic changes in neural architecture in adulthood (6) including those that take place during long-term memory (LTM) formation (7). The molecular machinery controlling local protein synthesis has been best studied in vertebrate oocyte development during which members of the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding (CPEB) protein family, in concert with other RNA-binding proteins, control the temporal expression of maternal RNAs (8, 9). More recently, CPEB proteins also have been found to be expressed in adult nervous systems (10–13) where they are thought to be involved in synaptic plasticity and LTM (12, 14–17), suggesting evolutionary conservation of the mechanism of local translation across species, tissues, and developmental stages.

The Drosophila melanogaster genome encodes two CPEB proteins, Orb and Orb2, representing two distinct branches of this family: Orb belongs to the CPEB1 branch, and Orb2 is the single representative of the CPEB2 subfamily. Although both proteins play critical and nonredundant roles in germline formation (18, 19), Orb2 is also essential for nervous system development (13) and is acutely required for LTM (12, 20), as is Orb (15). Both proteins contain an unstructured N-terminal poly-glutamine (poly-Q) stretch and a well-conserved C-terminal RNA-binding domain (RBD) consisting of two RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) and a zinc finger (Znf) region (12). Most CPEB proteins exist in multiple isoforms (11). Orb2 has two variants, Orb2A and Orb2B (12), which differ in the composition of the N terminus preceding the poly-Q and share a common RBD (12). The poly-Q is required exclusively for LTM, whereas the RBD is required for both development and LTM (20), and its mutations are lethal (12, 13). Moreover, the RBD of Orb2 can be functionally replaced by the RBD of mouse CPEB2 (mCPEB2) but not by that of Orb or mCPEB1, suggesting the conservation of target specificity within but not between the CPEB subfamilies, at least in regard to their developmental function (20).

The function of the CPEB proteins is critically dependent on their ability to bind specific mRNA targets. However, our knowledge about their binding specificity remains incomplete. Although the CPEB1/Orb subfamily has a well-established specificity toward the T-rich cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE) sequence (21), reports about the Orb2 subfamily binding motif are conflicting. In a study involving SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment), the rodent Orb2 orthologs CPEB3 and CPEB4 (22) were shown to bind stem–loop RNA structures rather than the linear CPE sequence recognized by the CPEB1 paralogue. Other reports suggest that both CPEB1 and CPEB4 recognize and control at least partially overlapping sets of mRNA targets and bind the same motif (23–25). Although a small number of fly Orb2 mRNA targets was described (26), the authors could not identify the bound sequence unambiguously. Thus, the full spectrum of fly CPEB targets is largely unknown, with previous studies characterizing only a limited number of interacting mRNAs (26–28). Elucidation of the RNA-binding specificity of Orb2 and the identification of its mRNA targets is essential to understand the role of downstream effectors in local translation-dependent processes, including LTM formation.

In this study we aimed at the transcriptome-wide identification of Orb- and Orb2-binding sites and mRNA targets using cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP). Through an extensive bioinformatic analysis of the high-throughput sequencing data, we obtained a comprehensive list of mRNA targets regulated by Drosophila CPEB proteins and determined that Orb and Orb2 bind CPE-like sequences but potentially do so with shifted specificity for particular motif subtypes and length. We independently confirmed the requirement for this motif in Orb2-dependent translational repression and showed that a number of candidate Orb2 CLIP targets are translationally regulated in a cell-based assay and in fly head extracts. Finally, knockdown of a subset of the verified Orb2 targets impairs courtship LTM, suggesting the functional significance of these targets in this process in vivo. Our results suggest that both CPEB proteins might function as key regulators of local protein synthesis in a plethora of biological contexts, including LTM, by binding to distinct variants of the CPE motif and regulating a common set of target mRNAs.

Results

CPEB Proteins Bind 3′ UTRs of mRNA Targets Through the RRM but not the Znf.

To identify Orb and Orb2 RNA-binding sites and potential mRNA targets on a transcriptome-wide scale, we used UV CLIP (29). To generate CLIP libraries, we used the D. melanogaster S2 cell expression system (30) in which we expressed WT or mutant forms of fly CPEB proteins. Orb2 mRNA is expressed endogenously in S2 cells [average reads per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped (RPKM) = 8.5; n = 2], and more than 90% of their transcriptome is detectable (RPKM >1) in the neuronal and gonad tissues, which express CPEB proteins in vivo (SI Analysis) (31). This expression and the fact that S2 cells allow Orb2-mediated translational suppression (26) suggest that S2 cells constitute a suitable system for investigating the transcriptome-wide Orb2-binding profile. Importantly, in S2 cells the overexpressed Orb2A exists in the form of protein clusters, reflecting its endogenous propensity to aggregate (Fig. S1A). In contrast, the overexpressed Orb2B isoform forms smaller clusters that partially colocalize with the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) markers Trailer hitch (Tral) and Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) (Fig. S1 A and C), reminiscent of the endogenous Orb2 protein in Drosophila brain in vivo (20). CPEB aggregates are thought to be associated with their normal function, including LTM, and to be mediated by the poly-Q domain (20, 32–34). In comparison, Orb mRNA is not expressed in S2 cells (average RPKM = 0.1; n = 2), although the majority of its known interactors (88%) are present (RPKM >1) (35, 36). Also, overexpressed Orb forms particles that partially colocalize with RNP markers (Fig. S1 B and C). Nevertheless, we have generated inducible S2 cell lines for both proteins, with Orb serving as a reference for our approach because its binding specificity is well defined (21, 37).

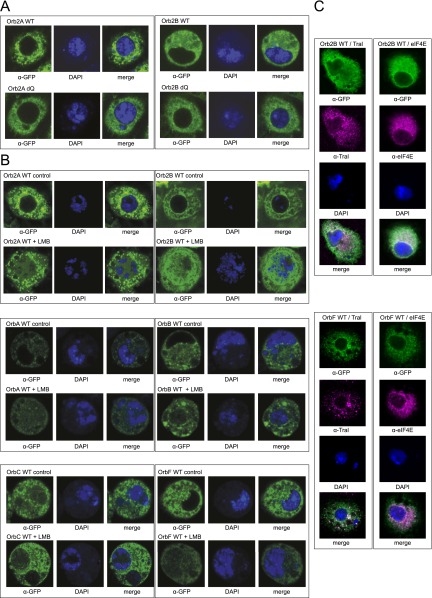

Fig. S1.

D. melanogaster CPEB proteins shuttle to the nucleus. (A) The C-terminally GFP-tagged Orb2A and Orb2B WT and poly-Q region-deleted isoforms were expressed in S2 cells. The WT but not the ΔQ Orb2A protein shows pronounced aggregates outside the nucleus. Neither the WT nor the ΔQ Orb2B isoform shows high levels of aggregation. (B) Representative images of S2 cells show the localization of C-terminally GFP-tagged Orb and Orb2 isoforms under normal growth conditions (control) and upon leptomycin B (LMB) treatment. Leptomycin B blocks nuclear protein export via the Crm1 pathway, thereby trapping the protein in the nucleus. The GFP signal is visualized in green and DAPI staining of the DNA is blue. Both Orb2 isoforms are primarily cytoplasmic but accumulate in the nucleus when nuclear export is inhibited. Note the characteristic aggregates formed by Orb2A but not by Orb2B protein in the cytoplasm. Orb A, B, and F isoforms are also primarily cytoplasmic, but the C isoform (which lacks a predicted proximal nuclear export signal sequence because of alternative splicing) can be detected in the nucleus even without leptomycin B treatment. (C) Representative images of S2 cells show that Orb2B (Upper) and OrbF clusters (Lower) (green) partially colocalize with the RNP markers Tral (magenta) and eIF4E (magenta). (Magnification: 63×.)

Several modifications of the original CLIP protocol (38) confer advantages in sample preparation and postexperimental data analysis. To increase UV cross-linking specificity and to facilitate robust bioinformatic analysis based on diagnostic mutations, we combined the PAR-CLIP (39) and iCLIP (40) protocols, allowing identification of cross-linking sites based on specific mutations and read termination events, respectively. Because efficient UV cross-linking is crucial for CLIP, we first assessed the ability of both Orb and Orb2 proteins to form UV-induced RNA cross-links. We expressed WT and mutated protein variants in S2 cells (30) in the presence of the photoactivatable nucleotide analog 4-thiouridine (4-SU). The proteins were tagged C-terminally with the myc epitope, which does not interfere with their in vivo function (12, 20).

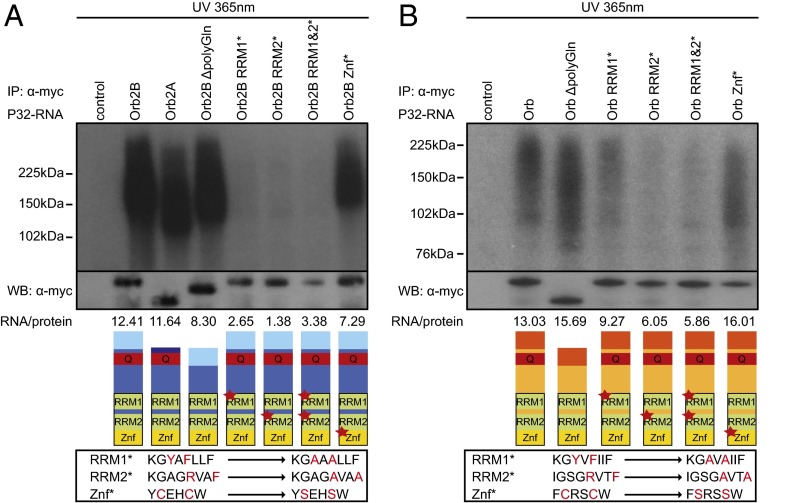

First we investigated whether UV cross-linking is mediated by the RBD. We expressed Orb2A and Orb2B in S2 cells (12, 20). Both isoforms cross-linked to RNA robustly (Fig. 1A); however, we focused on Orb2B because it requires intact RBD for its in vivo function (20). We generated mutations in the regions outside and within the RBD. Mutations of conserved residues in either of the RRM motifs (Y492/F494 and R601/F604) (20) in the proximal part of RBD abolished binding to control levels. Surprisingly, mutating the conserved cysteines (C669/C672) in the Znf of the RBD, previously implicated in RNA binding in vitro (22), had only a minor effect. Similarly, deletion of the Orb2 poly-Q region (Δ168–220), shown to be essential for LTM (12), had no impact on its RNA-binding ability. Analogous results were obtained for the corresponding mutations in the Orb protein, although the RRM1 mutation had a smaller effect (Fig. 1B). The lower UV cross-linking signal in Orb compared with Orb2 is likely caused by slightly lower Orb overexpression and possibly by intrinsic differences between the proteins, which share only about 40% of RBD homology. Detailed quantification of the RNA cross-linking can be found in Fig. S2A. These data show that modifications of the regions outside the RBD (poly-Q deletion or the substitution of an alternative N-terminal exon) do not influence the robustness of RNA cross-linking, but the RRM sequence (although not the Znf in the RBD) is necessary for efficient RNA binding in both proteins.

Fig. 1.

CPEB proteins bind to RNA using RRM but not Znf motifs. The RRM region of Orb2 (A) and Orb (B) RBD, but not the Znf or N-terminal regions, is necessary for UV-induced RNA cross-linking. Shown are autoradiography of P32-labeled complexes of UV cross-linked RNA with different Orb2 variants and corresponding Western blot images of immunoprecipitates (IP). Control indicates a mock precipitation of Orb2B-GFP (A) or Orb-GFP (B) protein with α-myc antibody. The UV wavelength and power are indicated above the image. All Orb2 mutations are derived from the B isoform. The WT A isoform differs from B isoform in its N-terminal exon. Schematics of Orb2 and Orb variants corresponding to tested constructs and RNA/protein signal ratios are shown below. The Q-rich region is shown in red; the RBD is outlined in black with RRM motifs in green and Znf in yellow. Alternative Orb2 exons are depicted with different shades of blue. Sequences of mutated regions are shown in boxes below the protein schematics.

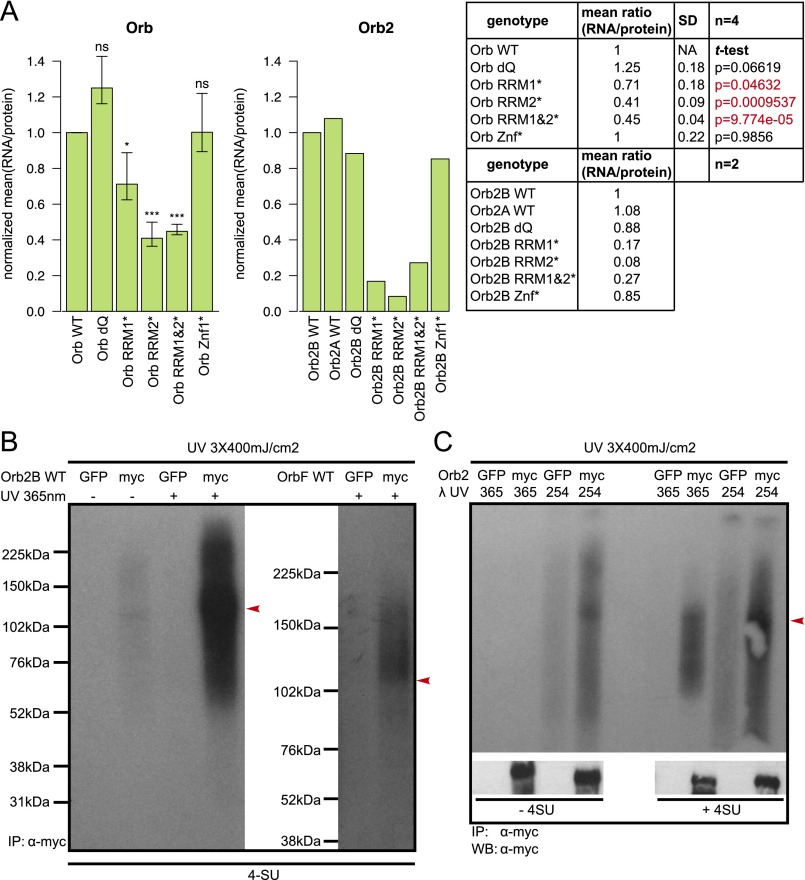

Fig. S2.

Quantification of the RNA cross-linking to the D. melanogaster CPEB proteins and of the specificity of the coimmunoprecipitation and RNA cross-linking. (A, Left) Bar plots show mean Orb and Orb2 RNA/protein signal ratios (for Orb ± SD/SEM) normalized to WT protein (first bar) as quantified from RNA autoradiography and corresponding Western blot images using Fiji software (76). (Right) The table provides the mean values (with statistical analysis for Orb protein). *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001. (B) Autoradiography gels illustrating the UV cross-linked P32-labeled protein/RNA complexes of Orb2B (Left) and OrbF (Right). No signal is detected in the absence of UV light or in the case of mock precipitation using GFP antibodies. (C) UV cross-linking using the 365-nm UV light is dependent on the use of photoactivatable 4-SU. The autoradiography gel illustrates the requirement for 4-SU for efficient protein/RNA cross-linking with the 365-nm but not with the 254-nm UV wavelength. The shorter wavelength also produces higher background signal in the mock precipitation conditions (GFP lanes).

To analyze the Orb- and Orb2-bound transcriptome, we performed PAR-CLIP experiments. We generated multiple replicate cDNA libraries from S2 cells expressing C-terminally myc-tagged Orb or Orb2 pretreated with 4-SU to enhance RNA cross-linking specificity (39) or with 6-thioguanosine (6-SG) to control for potential cross-linking bias. cDNA libraries were prepared with α-myc antibodies following an iCLIP protocol (40). We prepared six Orb2 and three Orb 4-SU cDNA libraries and a single 6-SG library for each genotype. As a negative control, we prepared a library from cells expressing the loss of the RNA-binding mutant protein, Orb2B RRM1&2*-myc. The RNA–protein cross-linking was specific, because additional controls (no UV illumination, no photoactivable nucleotide treatment, and mock precipitation with the α-GFP instead of α-myc antibodies) produced no signal on the autoradiography gel (Fig. S2 B and C). Details on CLIP sample preparation, sequencing, and analysis can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

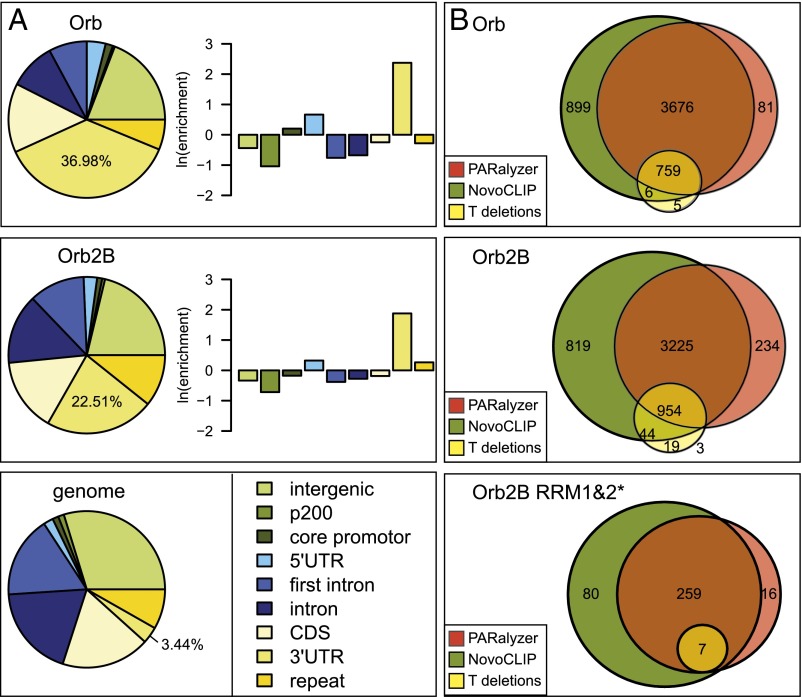

As expected from previous studies, the binding sites of Drosophila CPEB proteins (26, 27) are located preferentially in 3′ UTR regions: 22.5% of all Orb2-bound and 37% of all Orb-bound reads are located in 3′ UTR regions, although this genomic feature only covers 3.4% of the fly genome (6.6× and 10.8× enrichment, respectively) (Fig. 2A). Little binding was shown in intronic regions for either genotype. This finding is not surprising, because CPEB proteins are largely cytoplasmic under normal growth conditions, although they can shuttle to the nucleus (Fig. S1B).

Fig. 2.

CPEB proteins bind the 3′ UTR of target mRNAs. (A) Fly CPEB-binding sites are enriched in 3′ UTRs. Pie charts illustrate the relative contribution of reads in various gene regions in comparison with their genomic distribution shown at right. The percentages of reads mapping to 3′ UTRs are indicated. Bar plots depict the enrichment of reads in indicated regions as the natural logarithm of the ratio between sample and genomic read fraction in each region. (B) Primary CLIP targets based on 3′ UTR mapping clusters. Venn diagrams illustrate the number of CPEB targets identified with three complementary approaches. The numbers inside the circles represent the number of targets identified with the respective methods. Note that Orb2B RRM1&2* binds few targets.

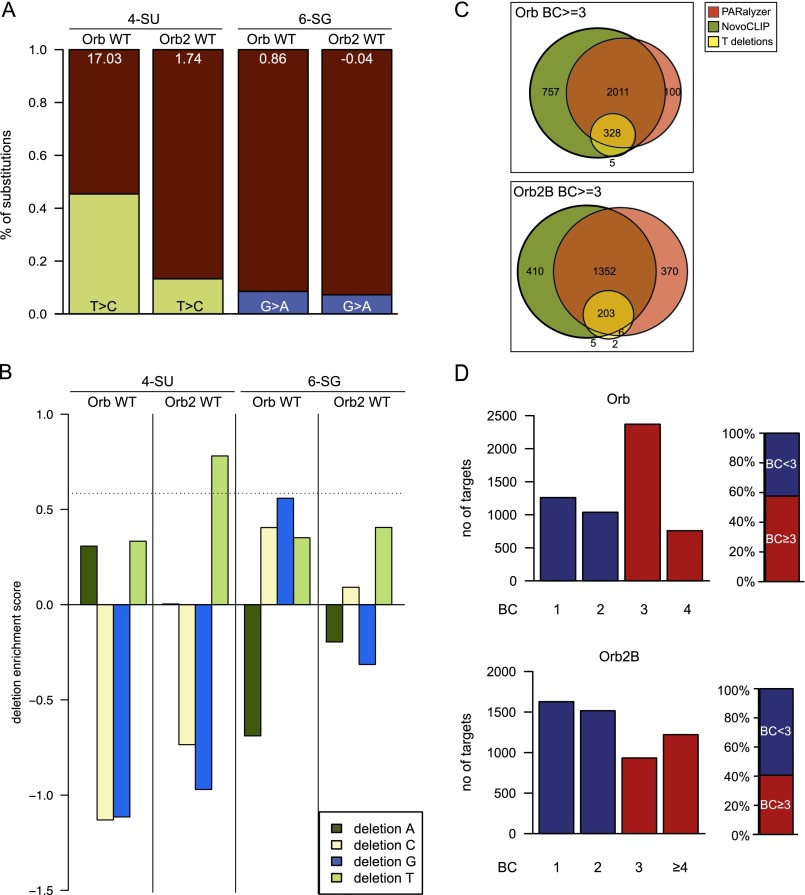

To identify the potential target genes, we used three complementary methods. First, we used the PARalyzer method (41), which is based on the diagnostic substitutions (T > C or G > A) at cross-link sites stemming from the use of photoactivatable nucleotide analogs (39). Second, we created an in-house method, NovoCLIP, which incorporates information based both on substitutions and on read termination positions characteristic of iCLIP protocol (40). Finally, because deletions were reported to be indicative of cross-linking sites (42), potential targets were scored using T or G deletions as diagnostic mutations. The Orb dataset is highly biased for T > C substitutions (Fig. S3A), whereas Orb2 shows a higher bias for T deletions (Fig. S3B); both datasets were used for analysis. Potential target genes were identified based on cross-linking sites overlapping the 3′ UTR regions of annotated genes. All methods led to largely overlapping results (82% and 79% of Orb and Orb2 targets were identified by both PARalyzer and NovoCLIP methods) (Fig. 2B), although deletion analysis yielded fewer target sites because of the relative rarity of such events.

Fig. S3.

The distribution of diagnostic mutation types in CPEB CLIP datasets prepared with 4-SU or 6-SG and characterization of the Orb2 RRM1&2* control library. (A) The fraction of diagnostic mutations (T > C for 4-SU and G > A for 6-SG libraries). The numbers inside the bars illustrate the nucleotide conversion bias (transition rate index). Note the high T > C mutation bias for Orb 4-SU samples. (B) The distribution of deletion types presented as enrichment scores. Enrichment scores are calculated as described in SI Materials and Methods. Orb2 samples are enriched for T deletions. In the 6-SG dataset the bias for G deletions is only slight in the Orb dataset and is absent in Orb2 libraries. The dashed line indicates the 1.5-fold enrichment threshold. (C) Reproducible CLIP targets (BC ≥ 3) based on 3′ UTR mapping clusters. The Venn diagrams illustrate the number of CPEB targets identified with three complementary approaches. The numbers inside the circles represent the number of targets identified with the respective methods. (D) Bar plots illustrate the fraction of Orb and Orb2B targets with the indicated reproducibility. Red bars show targets with BC ≥ 3; blue bars show targets with BC < 3. Plots on the right show the percentage of all targets with BC ≥ 3 (red) or <3 (blue).

Biological complexity (BC) is an established criterion used to filter CLIP datasets to minimize experimental noise (43). Candidate targets were filtered by their reproducibility in at least three independent libraries (BC ≥ 3). We identified 3,128 targets for Orb and 2,154 for Orb2. Most targets were identified by both PARalyzer and NovoCLIP: 73% for Orb and 66% for Orb2 (Fig. S3C). In contrast, the single Orb2B RRM1&2* control library identified only 376 genes. The list of genes containing CPEB cross-linking sites in their 3′ UTRs and their reproducibility are provided in Fig. S3D and Dataset S1.

Orb and Orb2 Bind to Linear CPE Motifs.

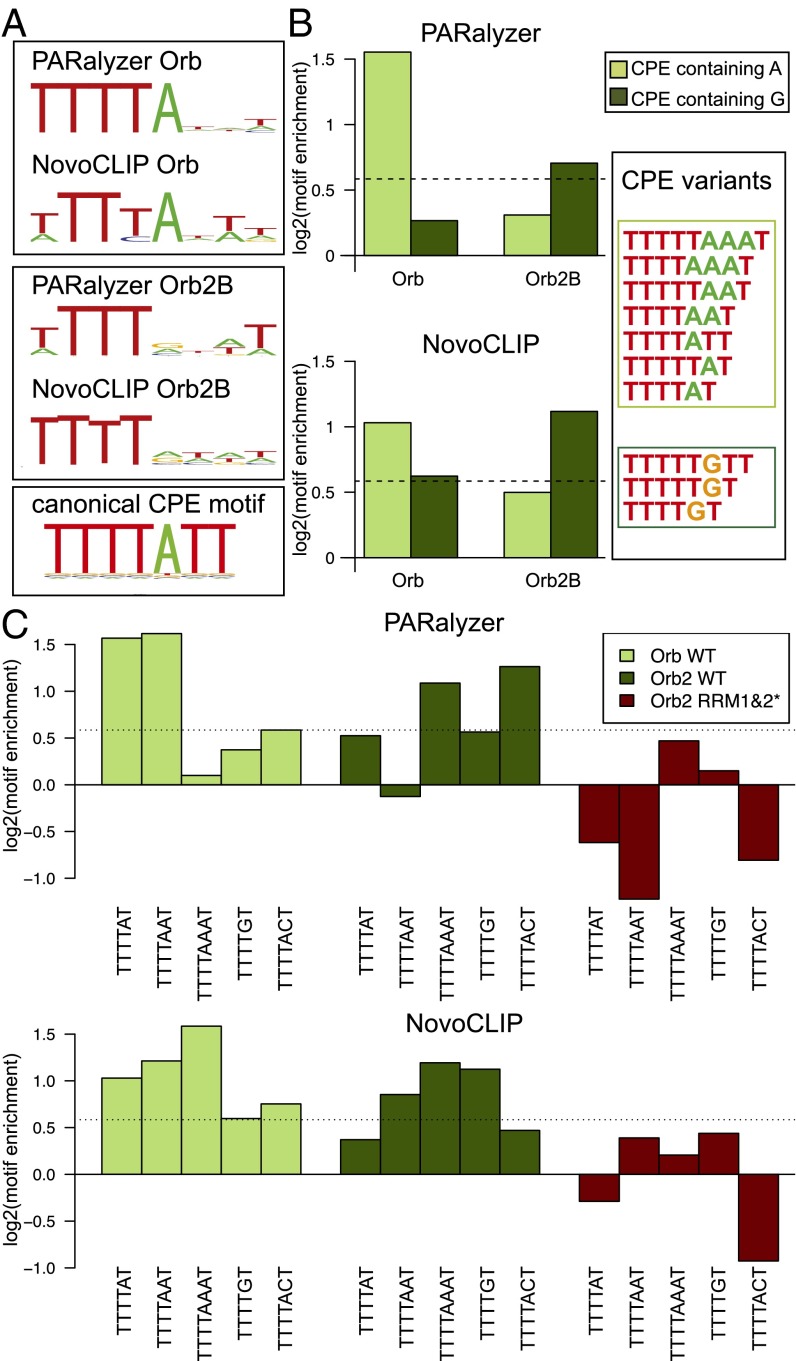

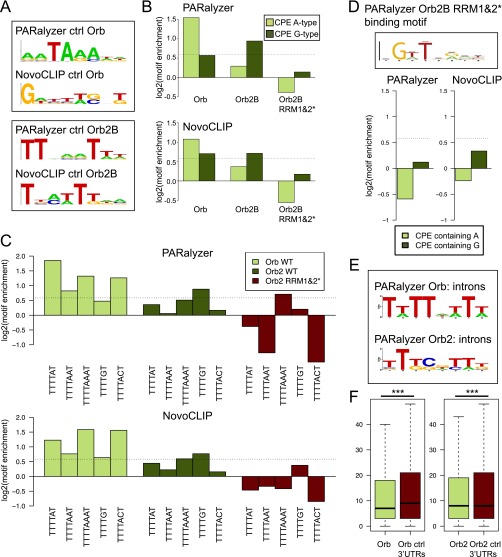

To resolve a long-standing question about the RNA-binding specificity of Orb2, we turned to de novo motif discovery using BioProspector (44). The analysis of the Orb dataset returned a T-rich binding motif comprising four T nucleotides followed by A in the fifth position. This motif closely resembles the linear CPE sequence bound by the vertebrate Orb ortholog CPEB1 (21, 37). In contrast, analysis of the Orb2 dataset revealed a T4 motif that could not be resolved toward the 3′ end (Fig. 3A). For comparison, nontarget 3′ UTR sequences are not enriched in CPE motifs (Fig. S4A).

Fig. 3.

Fly CPEB proteins bind the T-rich CPE sequence motif necessary for Orb2-mediated translational repression. (A) Sequence logos for Orb and Orb2 obtained using the PARalyzer and NovoCLIP methods separately. The canonical CPE motif is shown below. (B) CPE motifs are enriched in the CPEB CLIP dataset. Orb-binding sites are enriched in typical A-containing CPE motifs (light green), whereas Orb2 shows more preference for G-containing versions (dark green). The CPE variations used are listed on the right. (C) Enrichment scores for distinct versions of the CPE motif containing A or G in the fifth position. Orb and Orb2 are enriched for different CPE versions, whereas the Orb2 RRM1&2* mutant protein does not show enrichment for any analyzed sequences. Dashed lines indicate the 1.5-fold enrichment threshold.

Fig. S4.

Motif analysis compared with the nontarget 3′ UTR background: control Orb2B RRM1&2* and intronic motifs. (A) Motif logos for the nontarget 3′ UTR sequences generated with BioProspector. (Upper) Motif of the 3′ UTRs not identified as targets of Orb but expressed in S2 cells (RPKM >1) using either PARalyzer or NovoCLIP. (Lower) Corresponding logos for Orb2 control background 3′ UTRs. (B) CPE motifs are enriched in the CPEB CLIP dataset compared with the nontarget 3′ UTR background. Orb-binding sites are enriched in typical A-containing CPE motifs (light green), whereas Orb2 shows more preference for G-containing versions (dark green). The Orb2 RRM1&2* mutant protein does not show enrichment of CPE motifs. (C) Enrichment scores for distinct versions of the CPE motif containing A or G in the fifth position compared with the nontarget 3′ UTR background. Orb and Orb2 show a preference for different CPE versions, whereas the Orb2 RRM1&2* mutant protein does not show enrichment for any of the analyzed sequences. Dashed lines indicate the 1.5-fold enrichment threshold. (D) Orb2B RRM1&2* has no specificity for the CPE sequence. The sequence logo for Orb2B RRM1&2* CLIP dataset generated with BioProspector is shown for the PARalyzer method. The bar plots show that CPE motifs are not enriched in the Orb2B RRM1&2* CLIP dataset analyzed with either method. The dashed lines indicate the 1.5-fold enrichment threshold. (E) Sequence logos for Orb and Orb2 intron-mapping clusters obtained using the PARalyzer method reveal CPE (Orb) and T-rich CPE-like (Orb2) sequences. (F) The box plots illustrate the distances between CPE motifs and poly(A) signal sequences in CLIP targets (green) and control nontarget 3′ UTRs (dark red). The average distances for the CLIP targets are slightly but significantly shorter (Student t test, ***P < 0.001).

Because the 3′ variability in the CPE motif composition and length (45–48) can obscure the de novo analysis, we searched both datasets for CPE variants containing either A or G in fifth position (Fig. 3B) and calculated enrichment over background 3′ UTR control. The analyzed groups of CPE motifs were indeed enriched in CLIP sequences for both proteins. A-containing motifs are consistently enriched in the Orb dataset, as expected from de novo analysis. In contrast, the Orb2 dataset showed overall enrichment for G-containing motifs. A more detailed comparison of individual motif types shows that the Orb dataset is enriched in CPE variants containing A in the fifth position [TTTT(A)1–3T], whereas the TTTTGT and TTTTAAAT motifs are the most enriched in the Orb2 dataset (Fig. 3C); this difference could explain the difficulty in resolving the fifth nucleotide in de novo analysis. Modification of this analysis using only nontarget 3′ UTRs as the background model supports the strong preference of Orb protein for A-containing CPE variants (Fig. S4 B and C). Interestingly, in this case the Orb2 dataset enrichment of TTTTAAAT is much lower, whereas the TTTTGT sequence remains a predominant motif (Fig. S4 B and C). In contrast, no clear de novo motif or enrichment of the CPE sequences was found for the Orb2B RRM1&2* control dataset (Fig. S4D). A CPE-like motif also can be found in clusters derived from intronic binding (Fig. S4E), especially for Orb, although introns were not enriched in the CLIP dataset (Fig. 2A). Additionally, because CPEB proteins are known to influence splicing in proximity to poly(A) signal sequences (49), we analyzed the average distance between CPEB-bound motifs and poly(A) signal sequences (Fig. S4F). There is a small but significant difference in the average distance compared with the nontarget 3′ UTR background (13.8 for Orb and 14.9 for Orb2 compared with 17.3 and 16.8 for the control sets, Student t test, P < 0.001).

Taken together our results show that, although both CPEB proteins recognize CPE motifs, Orb has a clear preference for canonical TTTT(A)1–3T sequences. Orb2 appears to have a broader specificity that may include but not be restricted to motifs containing G in the fifth position. However, it must be mentioned that the results of the analysis of the Orb2 motif variant are influenced by the method used, and further biochemical studies will be needed to confirm the specificity shift between the paralogues and its functional significance.

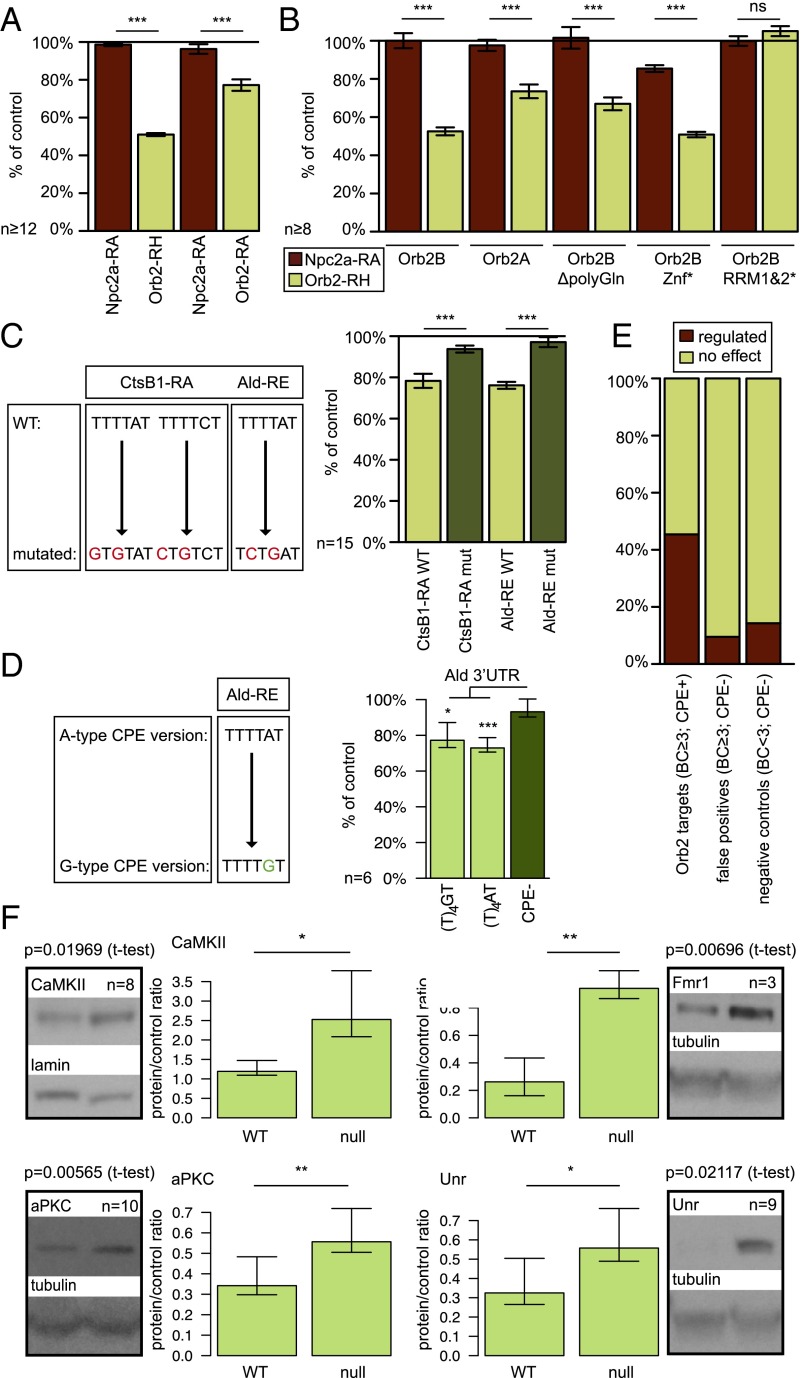

To confirm that the CPE motif is indeed required for the Orb2-mediated translational control, we turned to a dual luciferase reporter assay. Orb2 was previously shown to repress the translation of a small number of targets, including its own 3′ UTR (26). Indeed, expression of the firefly luciferase tethered to a long version of 3′UTR of Orb2 isoform H (RH) or short of Orb2 isoform A (RA), was repressed by Orb2 (RH: ratio 0.51 ± 0.01 SEM, RA: ratio 0.77 ± 0.03 SEM, Student t test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A). RRM mutations (Orb2B RRM1*, 2*, and 1&2*) abolish the repression of target translation (Student t test, P = 0.16), but poly-Q or Znf alterations have no effect (Student t test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B), as is consistent with the RNA UV cross-linking pattern (Fig. 1A). We did not assess the effect of Orb mutations in this assay, because WT Orb caused a widespread, unspecific repression of all tested 3′ UTRs, perhaps caused by pleotropic effects or by a requirement for additional components lacking in S2 cells.

Fig. 4.

The CPE motif is necessary for the Orb2-mediated translational regulation. (A) The dual luciferase reporter assay shows that Orb2B represses the translation of its own 3′ UTRs but not nontarget 3′ UTRs (Npc2a-RA) compared with the Orb2 RRM1&2* mutant. Results come from at least 12 independent transfections. (B) The effects of Orb2 mutations on translational repression. Neither N-terminal modifications nor a Znf mutation abolish translational repression of the Orb2-RH 3′ UTR, whereas RRM1&2* mutations cannot mediate translational repression. Results come from at least eight independent transfections. (C) CPE mutations (dark green) in CtsB1 and Ald 3′ UTRs abolish the repression of reporter translation by Orb2B in comparison with WT (light green). Mutations of CPE motifs are depicted on the left. Results come from n = 15 independent transfections. (D) The type of the CPE (TTTTAT vs. TTTTGT, both light green) does not affect the translational repression of the Ald 3′ UTR. Results come from six independent transfections. (E) Summary of the results of the dual luciferase reporter assay of the tested Orb2 target subset. The bar plot illustrates the proportion of regulated and unaffected targets within each category. (F) Quantitative Western blots for chosen proteins regulated by Orb2. The bar plots illustrate the quantification of protein levels in WT and orb2-null fly head extracts (mean ± SD/SEM). Representative blot images are shown next to the plots. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Having established that Orb2-mediated translational repression depends on its RRM regions, we tested the role of the CPE motifs in the 3′ UTRs of potential targets using the same assay. To allow easier analysis, we chose two Orb2 targets with relatively short 3′ UTRs containing a small number CPEs in close proximity: aldolase isoform E (Ald-RE) and cathepsin B1 isoform A (CtsB1-RA). Both these 3′ UTRs confer repression on the luciferase reporter (Ald-RE 0.76 ± 0.02 SEM, and CtsB1-RA 0.78 ± 0.03 SEM). The mutation of CPE motifs in these 3′ UTRs abolished this effect (Ald-RE no CPE 0.97 ± 0.02 SEM, and CtsB1-RA SEM 0.94 ± 0.02), which is significantly different from that seen in WT 3′ UTR variants (Student t test, both P < 0.001) (Fig. 4C). These results show that the presence of CPE motifs in target 3′ UTRs is necessary for Orb2-mediated translational control. Moreover, mutating the single CPE motif in Ald-RE from TTTTAT to TTTTGT leads to equally potent translational suppression mediated by Orb2 (Fig. 4D), indicating that Orb2 can bind both A- and G-containing CPE variants, at least under conditions of overexpression.

Orb2 Regulates the Translation of Its Targets in Vitro and in Vivo.

Having established that Orb2 regulates translation through a CPE motif, we narrowed the list of Orb2 targets to the most reproducible ones occurring in at least three independent libraries (BC ≥ 3) for which individual CLIP clusters overlap at least one CPE motif (CPE+) (Dataset S1). The final list contained 1,637 3′ UTRs (76% of BC ≥ 3 primary targets and 9% of Drosophila genes). Similarly, 2,691 Orb targets overlapped a CPE element (86% of BC ≥ 3 primary targets and 15% of Drosophila genes). More than 94% of identified Orb2 targets and 98% of Orb targets are also expressed in fly head extracts, suggesting that these mRNAs could be targets in vivo. In comparison only 94 3′ UTRs of all the Orb2B RRM1&2* targets have a cluster overlapping a CPE motif, as is consistent with the lack of enrichment for the motif in the mutant library.

To test functionally whether Orb2 regulates the translation of the identified target genes, we assessed the translational repression of the luciferase reporter induced by a set of target 3′ UTRs in the S2 cell-based assay as described above. We tested a set of 222 3′ UTRs representing 152 Orb2 target genes from the stringent dataset (BC ≥ 3, CPE+). Additionally, we tested 22 3′ UTRs of 21 genes classified as potential false positives: that is, genes with reproducibility of BC ≥ 3 but no CLIP cluster overlapping a CPE motif (BC ≥ 3, CPE−), and seven negative controls (BC < 3), whose RNA is expressed in the untransfected S2 cells with RPKM > 10 (Dataset S2). Of all the Orb2 target 3′ UTRs tested, 92 3' UTRs (41.4%) of 69 genes (45.4%) were regulated (all but two were repressed), compared with only two 3′ UTRs in the predicted false-positive set and a single 3′ UTR in the negative control set (Fig. 4E). In addition, we investigated the Orb2B regulated 3′UTRs for other 3′UTR features that might determine the regulation by Orb2. Although the 3′ UTRs regulated by Orb2 are longer on average and have higher CPE density (SI Analysis and Dataset S3), we failed to find any additional features that would predict whether a given CPE is active in Orb2-mediated translational repression (Fig. S5).

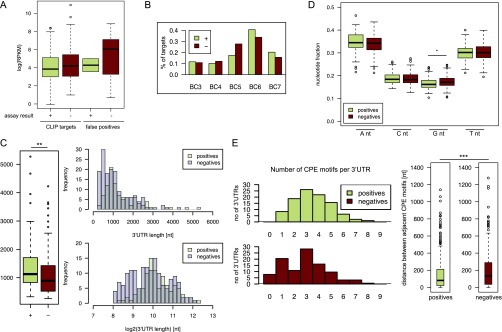

Fig. S5.

Comparison of 3′ UTR features in Orb2-regulated and unregulated sets as assessed using the luciferase reporter assay. (A) Expression levels of Orb2 CLIP targets and false positives. The 3′ UTRs regulated in the translational assay show a trend toward lower expression. (B) Orb2-regulated and unregulated target 3′ UTRs have similar reproducibility distribution. (C) Orb2-regulated 3′ UTRs are significantly longer than unregulated ones as shown by the box plot (Left) and length distribution histograms (Right). (D) Nucleotide composition does not differ significantly between Orb2-regulated and unregulated 3′UTRs except for a small increase in G nucleotides in the unregulated group. (E) All Orb2-regulated 3′ UTRs have at least one CPE motif, but motif presence is not sufficient for the regulation. (Left) Bar plots show the number of CPE motifs per 3′ UTR for regulated (Upper) and unregulated (Lower) sequences. (Right) Distances between CPE motifs are also significantly shorter in Orb2-regulated 3′ UTRs than in unregulated ones, as shown in the box plot. ***P < 0.001.

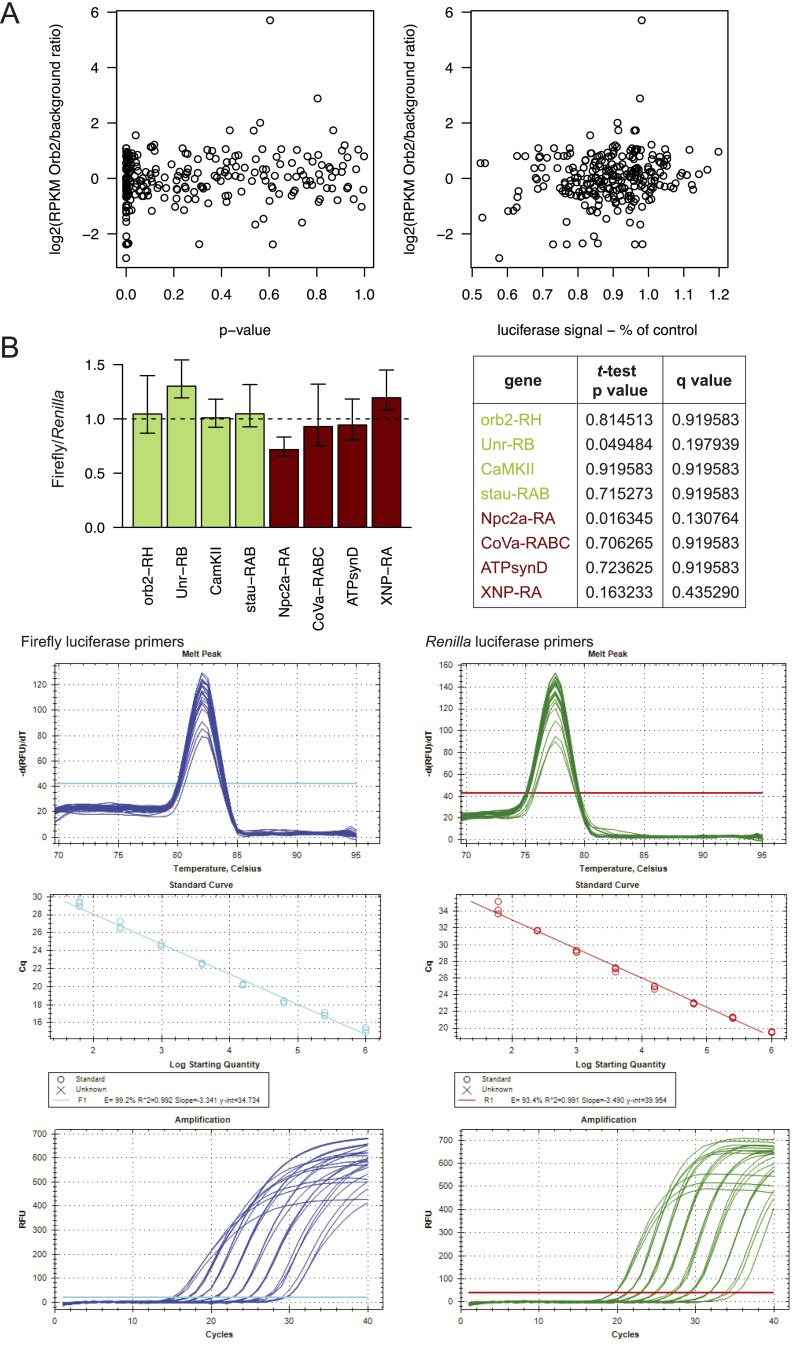

To test whether mRNA targets regulated by Orb2 in the S2 cell-based assay are also regulated in vivo, we investigated the expression of four proteins encoded by Orb2 targets [aPKC, Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), Fragile X mental retardation (Fmr1), and Upstream of N-ras (Unr)] in fly head extracts. We compared the protein levels in WT and Orb2-null fly heads using quantitative Western blotting (Fig. 4F). In all cases target protein levels are higher in heads of mutants lacking Orb2 suggesting that Orb2 acts as a translational repressor of these genes. The changes seen at the protein level are unlikely to be caused by Orb2’s effect on RNA transcription or stability, because the global S2 cell mRNA levels do not change drastically upon Orb2 overexpression except for a small number (169) of genes. Only 13% of the genes that change mRNA levels in the presence of Orb2 (22 genes) are Orb2 CLIP targets (Fig. S6A and Dataset S4). Moreover, quantitative PCR (qPCR) for chosen target and nontarget 3′ UTRs does not show a significant change in mRNA levels that would be consistent with translational regulation (Fig. S6B).

Fig. S6.

Expression levels of the CLIP targets in S2 cell line are not substantially affected by Orb2 overexpression. (A) Plots showing the relationship between the change in RNA level upon Orb2 overexpression in S2 cells (y axes) and outcomes of the in vitro luciferase reporter assay (x axes) expressed as P value (Left) or mean luciferase signal change (Right). There is no significant correlation between the change in RNA level and the result of the translational assay. (B) RT-qPCR assessment of the change in RNA level upon Orb2 overexpression in S2 cells. Representative regulated genes (green bars) and unchanged genes (dark red bars) that were tested in the in vitro luciferase assay were chosen for comparison. The bar plot indicates the mean RNA signal change (±SD/SEM) upon Orb2 expression. The table on the right provides the t test P values and corresponding q values. Standard melting curves for the tested (Firefly) and control (Renilla) primers are shown below.

Orb2 Targets Regulate Cell and Tissue Polarity Genes and Play a Role in Courtship LTM.

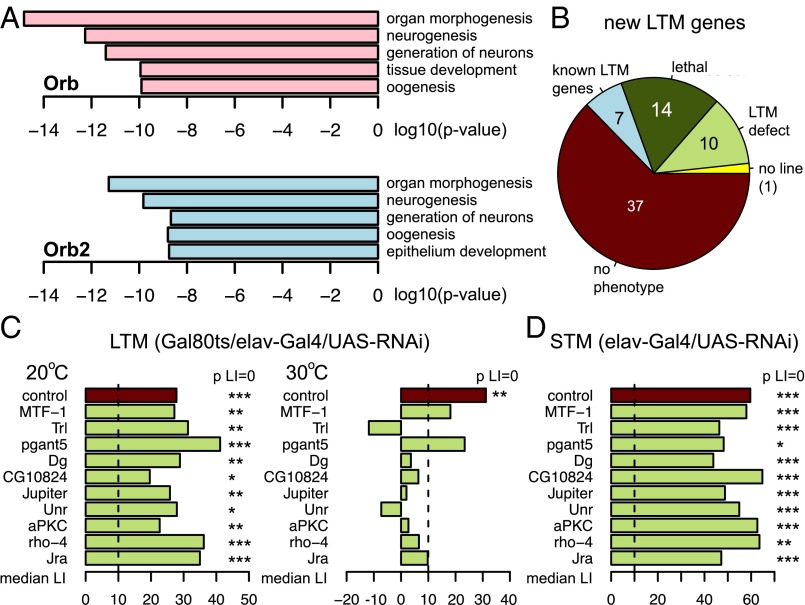

Orb2 has been best studied for its role in LTM formation and nervous system development, and some of its previously identified targets were suggested to contribute to these processes (12, 13, 19, 20, 26). To determine what other biological processes may be regulated by Orb2 targets,we turned to Gene Ontology (GO) analysis (50) performed with the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (51, 52). Neurogenesis is one of the top-ranking GO terms associated with Orb2 CLIP targets, supporting Orb2’s crucial role in this process (Fig. 5A) (12, 13, 20). Moreover, Orb2-bound transcripts are generally associated with the development of epithelial tissues and germline, suggesting that Orb2 may regulate a wide array of tissue-patterning and polarization processes (Dataset S5). Biological processes associated with Orb targets are reminiscent of Orb2, a finding that is unsurprising given the high overlap of Orb and Orb2 mRNA targets (Fig. 5A). The molecular function GO terms for the targets of both CPEB proteins shows a high involvement of protein kinases and small GTPases, suggesting regulation of signaling pathway components. The full list of significant terms for both proteins is provided in Dataset S5.

Fig. 5.

Orb2 target mRNAs are involved in neurogenesis and LTM. (A) The bar plots show the top five biological process GO terms for Orb and Orb2 targets ordered according to their corrected P value. (B) The pie chart shows the classes of phenotypes of translationally regulated Orb2 targets. (C) The bar plots illustrate the effect of RNAi knockdown of translationally regulated Orb2 targets on LTM tested in a courtship conditioning assay. Conditional pan-neuronal (elav-Gal4) knockdown in a restrictive temperature affects LTM (Right), whereas memory is normal in a permissive temperature (Left). Knockdown of two genes (pgant5 and MTF-1) causes a significant reduction in LTM but does not abolish it below the LI = 10 threshold. (D) The bar plot illustrates the effect of RNAi knockdown of translationally regulated Orb2 targets on STM tested in a courtship conditioning assay. Pan-neuronal (elav-Gal4) knockdown does not affect STM. Null hypothesis: LI = 0, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Because Orb2 is specifically required for LTM (12, 20, 32), we were interested in testing whether any of its translationally regulated targets have a role in this process. To this end, we knocked down candidate genes in all postmitotic neurons using the UAS-RNAi/Gal4 system and tested these flies for LTM induced by courtship conditioning (12, 53, 54). This form of memory is protein synthesis dependent (55) and requires an intact Orb2 RBD (20); thus the knockdown of relevant Orb2 RNA targets should impact LTM specifically. Of the 69 genes regulated by Orb2 in the luciferase reporter assay, seven are known to be involved in LTM [CaMKII, Fmr1, murashka (mura), pumilio (pum), spoonbill (spoon), signal-transducer and activator of transcription protein at 92E (Stat92E), and staufen (stau)]. We knocked down the expression of the remaining 61 candidates for which RNAi lines were available (there was no line for nct) in all neurons. Fourteen targets were lethal upon knockdown, possibly because of their involvement in the nervous system development, and were not analyzed further. The remaining 47 targets were tested using the LTM courtship conditioning assay. The knockdown of 10 (21.3%) of these genes was associated with the courtship LTM defect (Fig. 5B). This effect is specific to LTM and is not simply a developmental defect, because the function of these genes is required acutely for courtship LTM memory as assessed by conditional RNAi knockdown using the Gal80ts system (Fig. 5C). For all genes, knockdown under restrictive temperature resulted in impaired courtship LTM, although residual memory [learning index (LI) >10] was seen with the knockdown of two genes, polypeptide GalNAc transferase 5 (pgant5) and metal response element-binding transcription factor-1 (MTF-1); this result requires further validation. Moreover, the impairment of courtship LTM is not caused by a failure of flies to learn, given that the short-term courtship memory (STM) remains unaffected (Fig. 5D). Detailed statistical analysis of the behavioral assays can be found in Dataset S6.

SI Analysis

S2 Transcriptome Comparison.

To establish whether the relevant targets of CPEB proteins are expressed in S2 cells, we analyzed the S2 cell transcriptomes (cells overexpressing Orb2 and the background cell line) and compared them with published transcriptomes from tissues in which Orb or Orb2 are naturally present (testis, ovaries, and neural tissue). We used the data from modENCODE (Model Organism Encyclopedia of DNA Elements, www.modencode.org) dataset (S2 cell lines Sg4 and S2R, L3, and P8 CNS, ovary virgin and mated, and testis) (31) as well as our fly head transcriptome data. We applied the cutoff of RPKM >1 to classify mRNAs as expressed because it is the level detectable in the CLIP assay (13.6% of the Orb and 6.5% of Orb2 CLIP targets are expressed with RPKM 1–5 in the S2 cells).

We determined that more than 95% of the S2 cell transcriptome was transcribed in the fly head dataset. Conversely, a lower number (about 60%) of genes expressed in the fly heads were also detectable in S2 cells. Next, the subset of transcripts representing CLIP targets was analyzed separately for expression in fly heads and S2 cell lines. Only 33 Orb targets (1.2%) and 96 Orb2 targets (5.9%) are not expressed in the fly head transcriptome (RPKM <1). This analysis suggests that the great majority of detected CLIP targets can potentially be bound in vivo, although our method may miss some of the RNAs that are specific to neural tissue. Similar results were obtained when we compared the expression of CLIP targets in the S2 cells with the ModENCODE transcriptomes (cutoff RPKM >1). The results are presented in Table 2 of Dataset S3. The majority of CLIP targets (>90%) were expressed in all the relevant tissues, showing that, in principle, detected targets can be bound in vivo because their transcripts are expressed in the tissues containing CPEB proteins.

Features of Orb2 3′ UTR Targets.

This section presents the analysis of the features of 3′ UTR CLIP targets that show regulation in the in vitro luciferase reporter assay as opposed to those that do not. We included all the assayed 3′ UTRs (potential targets, CLIP targets classified as false positives, and negative controls) and divided them into two groups, those regulated by Orb2 in the in vitro assay and those that were unchanged. We analyzed the S2 cell expression levels, target reproducibility (BC), 3′ UTR length, nucleotide composition, motif type, frequency, and density.

Expression in the S2 cell line.

Orb2 CLIP targets that were not regulated in the translational assay show a trend toward higher mRNA expression levels than seen in regulated ones (mean and median RPKM values for negative and regulated 3′ UTRs were1,298.2 and 65.92 compared with 318.82 and 46.85, respectively). However, that difference is not significant (P = 0.1638, t test). The same trend is seen in genes classified as false positives (identified as Orb2 CLIP targets but not having a CPE site). Sequences found to be negative in the assay have mean and median RPKM values of 1,491.83 and 419.25, respectively, higher than those of the candidate CLIP targets that were negative in the assay; however, two of them, which were regulated in vitro, have lower expression (mean RPKM values of 91.22). Thus there is a tendency for false positives to be highly expressed genes; however a high level of expression should not by itself be used as an exclusion criterion, because some highly expressed genes [e.g., Ribosomal protein S11 (RpS11), Ribosomal protein L4 (RpL4), CG9894, and Ferritin 1 heavy chain homologue (Fer1HCH)] were confirmed as targets in the assay. The box plots in Fig. S5A illustrate the distribution of expression in various groups.

Target reproducibility.

The BC of targets regulated in vitro is similar to that of those not affected by Orb2 expression, although there is a small tendency toward higher BCs, as shown in Fig. S5B.

3′ UTR length.

The 3′ UTR sequences that confer regulation on the reporter in the S2 cell line are significantly longer (average and median lengths differ between the datasets: t test P = 0.0004643 on log2-transformed data, Mann–Whitney test, P = 0.001375). Nonetheless the length of 3′ UTRs in the two groups largely overlaps, as shown in Table 3 of Dataset S3 and in the length histograms and box plot in Fig. S5C.

Nucleotide composition.

We also analyzed nucleotide composition of the positive and negative datasets to see if a T-rich composition of a 3′ UTR could by itself bias the assay. We found no significant difference in the T nucleotide fraction in the datasets. More specifically, the mean and median frequency and the ranges for each nucleotide were similar in positive and negative 3′ UTRs (Dataset S3, Table 4). Moreover the differences found for T, A, and C nucleotides were nonsignificant (t test and Mann–Whitney test, P > 0.05), whereas the content of G nucleotide is slightly altered, as can be seen in Table 4 of Dataset S3 and boxplot in Fig. S5D.

We also wanted to know if the presence of T-rich stretches is required for regulation. All regulated 3′ UTR sequences have at least one TTTT sequence. Slightly fewer negative 3′ UTR have that motif (98.7%); 97.9% of positives and 90.4% of negatives also have a TTTTT motif. That finding suggests that, although T-richness of sequences overall is not a sufficient factor, T-rich clusters with at least four consecutive Ts (as in a CPE motif) may be required.

Motif type and frequency.

We analyzed the presence of different types of T-rich CPE-like short sequences and different versions of CPE elements. There is slightly higher contribution of T5 and T4A sequences in the regulated group, although both groups have a high share of T-rich sequences (Table 5 of Dataset S3).

Next, we assessed the presence of various types of the CPE motif (TTTTAT, TTTTAAT, TTTTAAAT, TTTTGT, TTTTGGT, TTTTGGGT, TTTTACT, TTTTAGT, and TTTTGAT) as summarized in Dataset S3, Table 6. All motives containing A at the fifth position and a single G-containing motif are enriched in the positive dataset. This finding agrees with the conclusions from the motif analysis for total Orb2 libraries, which point to enrichment in the same types of motifs (compare Fig. 3C and Table 6 of Dataset S3).

It is important to note that at least one CPE element is present in every single regulated sequence, whereas 7.7% of sequences in the negative dataset have no CPE at all. Therefore, although the presence of a CPE is not sufficient for regulation by Orb2, the fact that no 3′ UTRs within the positive subset lack this motif suggests that it is indeed required. However what determines the CPE to be “active” is unclear, because we failed to identify any other sequence that would explain this effect. The distribution of the number of CPE motifs per 3′ UTR is shown in Fig. S5E.

Motif density.

We also analyzed the distances between any the adjacent CPE motifs in 3′ UTR sequences that have more than one such sequence. We looked specifically at the four types of CPE motifs that were significantly enriched in the positive set (i.e., TTTTAT, TTTTAAT, TTTTAAAT, and TTTTGT). On average, the distances between CPE motifs are shorter for Orb2-regulated targets, although the ranges of the distance largely overlap (t test on log2-transformed data, P = 8.152981e-05; Mann–Whitney test, P = 5.335452e-06). A box plot showing the spread is given in Fig. S5E. We also looked at the position of the CPE motifs within the targeted 3′ UTR but found no consistent difference between the two datasets.

Comparison of Orb CLIP and Ovary Targets.

A list of Orb targets isolated from fly ovaries has been published previously (62). Therefore, we decided to compare these targets with the genes obtained using CLIP. Of the 699 potential targets identified in ovaries, 635 (90.8%) are expressed in S2 cells (RPKM >1). Of these genes 243 (38.3%) are stringent Orb targets (BC ≥ 3, CPE+) in the CLIP assay. An additional 69 genes (10.9%) are reproducibly present in the CLIP dataset but do not have clusters overlapping a CPE and would be classified as false positives by our criteria, and 163 genes (25.7%) were detected at BC = 1 or 2 and therefore were not classified as targets by our criteria. Twenty-five of the genes were not detected in our assay. The list of common targets is provided in Dataset S1.

We also compared the GO term analysis of the genes that were identified as targets by both methods with that of the genes identified only in the ovary RIP. In the analysis of biological processes the common targets are enriched in terms related to mitotic divisions and spindle organization, processes known to be under CPEB control. In contrast, the genes identified solely by RIP and not in our CLIP assay are enriched in terms related to mitochondria and metabolism. That difference suggests that the latter group may contain more false positives. The top five GO terms for each category are listed below:

CLIP and RIP common targets: mitotic spindle elongation, spindle elongation, mitotic spindle organization, spindle organization, translation

RIP only targets: cellular respiration, ATP synthesis-coupled electron transport, respiratory electron transport chain, translation, cellular protein metabolic process

SI Materials and Methods

S2 Cell Culture.

S2 cells were grown in semi-adhering liquid cultures at 27 °C in a water-jacketed incubator, with 5% CO2 in liquid Schneider’s Drosophila Medium (Invitrogen 11720-034) supplemented with 10% FCS and 100× Pen/Strep 15070 (1:100) (5,000 U/mL penicillin and 5,000 μg/mL streptomycin) (Invitrogen) without agitation. For imaging, Western blotting, and CLIP experiments, confluent S2 cell cultures were divided and added to fresh medium at a ratio of 1:3. The cultures then were grown overnight, washed with 1× PBS, and resuspended to a concentration of 2 million cells/mL before transfection with appropriate plasmids (800 ng) using Effectene Transfection Reagent (Qiagen, 301425) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After transfection cells were grown for 72 h and then were moved to selection medium containing hygromycin B (Roche, 10-843-555-001) at a concentration of 300 μg/mL. Confluent cells were split 1:3 and grown overnight before the induction of protein expression. On the following day CuSO4 (Sigma, C1297-100G) was added to a final concentration of 250 μM.

Generation of DNA constructs.

For inducible protein overexpression in S2 cells, appropriate Orb and Orb2 constructs were cloned from cDNA into expression vectors. For cDNA preparation, total RNA was isolated from w1118 fly heads using a modification of a standard procedure (65). Tissue was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and fly heads were collected through a metal sieve into an Eppendorf tube. One hundred microliters of TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, 15596-026) was added. Tissue was disrupted with a plastic pestle, and another 900 μL of TRIzol was added. The suspension was incubated for 5 min at room temperature and was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Then 200 μL of chloroform (Sigma, 288306–1L) was added to the lysate, mixed, and incubated at room temperature for 10 min before spinning at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The upper phase was transferred to another tube, mixed with 200 μL of chloroform, and spun down again at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The upper phase was transferred to another RNase-free tube (Ambion, AM12450), and 500 μL of isopropanol (Sigma, 278475-1L) was added for precipitation for 10 min at 30 °C. The RNA was pelleted for 10 min at 16,100 × g at 4 °C. Then the pellet was washed with 1 mL 75% ethanol (Sigma, 32221), spun down for 5 min at 7,500 × g at 4 °C, and dried for 5 min at 70 °C. The RNA was resuspended in 45 μL of UltraPure DNase/RNase-Free Distilled Water (Life Technologies, 10977035). DNA was removed by digestion using the DNA-free Kit (Ambion, AM1906). One microliter of recombinant DNase I (rDNase I) and 5 μL of 10× rDNase buffer were added to DNA and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Subsequently 1 μL of rDNase I was added, and incubation was continued for another 30 min. An 0.2 volume (10 μL) of DNase Inactivation Reagent was added to stop the reaction, mixed for 2 min at room temperature, and centrifuged for 2 min at 5,000 rpm (Eppendorf centrifuge 5418R) at room temperature. The supernatant was moved to another tube, and the RNA concentration was assessed at A260/A280 nm with a NanoDrop 8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). A cDNA library was prepared by reverse transcription using an oligo(dT)20 primer (Invitrogen, 18418-020). Forty to fifty microliters of total RNA (up to 50 μg) was mixed with 10 μL of 50-μM oligo(dT)20 primer, 10 μL of 10 mM dNTP Mix (Invitrogen, 18427-013), and RNase-free water to a volume of 130 μL. The reaction was incubated at 65 °C for 5 min and then was cooled for 1 min on ice. Seventy microliters of reaction premix [40 μL 5× First-Strand Buffer, 10 μL 0.1 M DTT, 10 μL SuperScript III RT enzyme (Invitrogen, 18080-093), and 10 μL RNaseOUT (Invitrogen 10777-019] was added to the preincubated RNA mix. The reaction was incubated for 1 h at 50 °C and was stopped for 5 min at 85 °C. The cDNA was cooled on ice, and 5 μL of RNaseH (Invitrogen, 18021-014) was added for 20 min at 37 °C. Typically, 2 μL of the cDNA library was used for a PCR.

First, the coding sequences were amplified with primers containing attB sites for the recombination of PCR products into a donor vector. For Orb2A WT, cDNA was PCR amplified with CP156/CP155. For Orb2B WT, cDNA was PCR amplified with CP154/CP155. For Orb2A ΔQ, cDNA was PCR amplified with CP157/CP155. For Orb2B ΔQ, cDNA was PCR amplified with CP154/CP158 and CP155/CP159. Products were overlapped with CP154/CP155. For Orb2B RRM1&2*, cDNA was PCR amplified with CP154/CP149 and CP155/CP148, and then PCR products were overlapped with CP154/CP155 to create the Orb2B RRM1* mutation. Next, the Orb2B RRM1* PCR product was amplified with CP154/CP151 and CP155/CP150, and products were overlapped with CP154/CP155. For Orb2B Znf*, cDNA was PCR amplified with CP154/CP153 and CP155/CP152. PCR products were overlapped with CP154/CP155. For Orb2A RRM1&2*, cDNA was PCR amplified with CP156/CP149 and CP155/CP148, and then PCR products were overlapped with CP156/CP155 to create the Orb2A RRM1* mutation. Next, the Orb2A RRM1* PCR product was amplified with CP156/CP151 and CP155/CP150, and products were overlapped with CP156/CP155. For Orb2A Znf*, cDNA was PCR amplified with CP156/CP153 and CP155/CP152. PCR products were overlapped with CP156/CP155. For Orb2A ΔQ, cDNA was PCR amplified with CP157/CP155. For OrbA, cDNA was PCR amplified with OrbAf/Orbr primers. For OrbB, cDNA was PCR amplified with OrbBf/Orbr primers. For OrbC, cDNA was PCR amplified with OrbCf/Orbr primers. For OrbF, cDNA was PCR amplified OrbFf/Orbr primers. For OrbF, the ΔQ WT template was amplified with OrbdQf/Orbr and OrbFf/OrbdQr primers, and the products were overlapped with OrbFf/Orbr primers. For OrbF RRM1*, the WT template was amplified with OrbFf/OrbRRM1r and OrbRRM1f/Orbr primer pairs, and the products were overlapped using OrbFf/Orbr primers. For OrbF RRM2*, the WT template was amplified with OrbFf/OrbRRM2r and OrbRRM2f/Orbr primer pairs, and the products were overlapped using OrbFf/Orbr primers. For OrbF RRM1&2*, the mutation was introduced as for OrbF RRM2* on the OrbF RRM1* template. For OrbF Znf*, the WT template was amplified with OrbZnff/Orbr and OrbFf/OrbZnfr primer pairs, and the products were overlapped using OrbFf/Orbr primers. All final PCR products were recombined into the pDONR221 vector (Invitrogen, 12536-017) using attB sites with Gateway BP Clonase II Enzyme Mix (Invitrogen, 11789-020) according to the manufacturer’s protocol to generate entry clones. All PCR products were purified from 1% Tris/borate/EDTA (TBE)-agarose gel using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, 28704) before the BP Clonase reaction. The destination vectors pMK/AWG and pMK/AWM were created by excising the expression cassette from Drosophila Gateway Vector Collection vectors pAWG and pAWM, respectively [https://emb.carnegiescience.edu/drosophila-gateway-vector-collection; Murphy, T. (2003-) The Drosophila Gateway Vector Collection]. Cassettes were excised with EcoRV/NheI (Roche) and cloned into the backbone of the pMK33/pMtHy vector (66) cut with EcoRV/SpeI (Roche). Entry clones then were recombined with pMK/AWG to generate expression vectors with a C-terminal GFP tag or with pMK/AWM to generate expression vectors with a C-terminal myc tag using Gateway LR Clonase Enzyme mix (Invitrogen, 11791-019) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

For the translational control assay in S2 cells, the protein expression vectors for transient transfection were cloned from pDONR221 entry clones containing Orb2B WT, Orb2A WT, Orb2B Znf*, and Orb2B RRM1&2* sequences. The vectors were recombined with pAWM to create expression constructs. To create control (Renilla) and test (Firefly) luciferase-expressing constructs, pAMW was cut with BamHI (Fermentas, FD0054), and the backbone fragment was ligated with a multiple cloning site (MCS) created by phosphorylated and annealed MCSf/MCSr oligonucleotides cut with BamHI. For the phosphorylation reaction, 1 μL of each 100-mM oligonucleotide was mixed with 1 μL of kinase buffer, 1 μL of 10-mM ATP, 5 μL of water, and 1 μL of T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (PNK) (Roche, 10838292001) and was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Annealing was done by heating the phosphorylated oligonucleotides to 90 °C in a thermoblock and slowly cooling it to RT. Next, the Gateway expression cassette was PCR amplified from pAMW with casAWMf/casAWMr primers and cloned into the pAMW-MCS linearized with NheI/Asp718 (Roche) to obtain the pAMW-cassette construct. For the pAMW-Fluc-cassette destination vector, the Firefly luciferase PCR product obtained by amplifying pAC-Fluc-6xBS with Flucf/Flucr primers was digested with SpeI/NheI and cloned into the NheI-cut pAMW-cassette vector. For pAMW-Rluc-cassette-poly(A), first the poly(A) signal sequence was amplified from pAMW with polAf/polAr primers and was cloned with Asp718/XhoI. Subsequently, Renilla luciferase was PCR amplified from pAC-Rluc with Rlucf/Rlucr primers, digested with SpeI/NheI, and cloned into the NheI-cut vector. To create the final pAMW-Rluc-SV403′UTR-poly(A) vector, the SV40 3′ UTR was PCR amplified from pAMW with SV403′UTRf/SV403UTRr primers and first was cloned into pDONR221 and then was recombined with the pAMW-Rluc-cassette-poly(A) vector. All plasmids were verified by sequencing. To insert the tested 3′ UTR sequences into the pAMW-Fluc-cassette vector, the appropriate target 3′ UTR sequences were PCR amplified from fly genomic DNA with primers adding the attB sites and were recombined with pDONR221. For the mutated 3′ UTR versions, the mutations were introduced by overlap PCR. For genomic DNA isolation 5 to 10 adult w1118 flies were placed in a Eppendorf tube and were frozen at −80 °C for at least 20 min. Fifty microliters of buffer A [100 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% SDS] were added, and tissue was disrupted with a plastic pestle. The lysate was incubated for 30 min at 65 °C, and 200 μL of freshly made LiCl/KAc solution (5 M LiCl solution mixed with 5 M potassium acetate solution at 3:1 ratio) was added. The lysate was incubated on ice for at least 10 min and was centrifuged for 15 min at room temperature at 16,100 × g. Two hundred fifty microliters of the supernatant was transferred to another tube, and DNA was precipitated with 150 μL of isopropanol. The precipitate was pelleted by spinning (16,100 × g) for 15 min at room temperature, and the pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and dried at room temperature in an open tube. The DNA was resuspended in 25 μL of 1× Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (10 mM Tris⋅HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8) and stored at −20 °C until use. Typically 2 μL of genomic DNA diluted 1:10 in water was used for a PCR. Primers were designed to extend about 200 nt downstream of the end of the 3′ UTR, into the genomic region, to include a native poly(A) signal. Resulting entry clones were recombined with the pAMW-Fluc-cassette to obtain pAMW-Fluc-3′ UTR plasmids. (All primer sequences are listed at the end of the SI text.) PCR reactions were set up with Herculase II Fusion Enzyme with dNTPs Combo (Agilent Stratagene, 600679) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All restriction enzymes used (Asp718, 10814245001, BamHI, 10656275001, EcoRV, 10667153001, NheI, 10885851001, SpeI, 11008951001, XhoI, and 10703770001) were from Roche unless otherwise indicated. All PCR reactions were performed with the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 56 or 58 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 3 min, and a final elongation at 68 °C for 4 min. Restriction reactions were set up in 40 μ at 37 °C for 2 h followed by dephosphorylation of backbone fragments with 2 μL of alkaline phosphatase (Roche, 10108146001) for 30 min at 37 °C. Digested fragments were purified from 1% TBE-agarose gel using the Qiagen kit. Ligation reactions were set up with T4 DNA ligase (Roche, 10716359001) and were incubated at least overnight at 16 °C before transformation into DH5α Escherichia coli-competent cells.

Preparation of CLIP samples.

Eight hours after induction S2 cells were treated with 4-SU (Sigma, T4509) or 6-SG (Sigma, 858412) (final concentration, 100 μM) and were grown overnight. UV cross-linking was done essentially as described in ref. 39. Induced S2 cells were collected by spinning for 5 min at 1,000 × g in a 15-mL tube and were washed once with RT 1× PBS buffer. The cell pellet was resuspended in 5 mL 1× PBS and was transferred to a cell-culture Petri dish for UV cross-linking (365 nm). Cross-linking was performed three times at 400 mJ/cm2 on ice for OrbF-expressing cells, and the cell solution was gently mixed between the UV exposures. Cells expressing WT Orb2B were prepared with different cross-linking powers: three times at 400 mJ/cm2 (6-SG replicate), 400 mJ/cm2 (three replicates), 100 mJ/cm2 (two replicates), or 10 mJ/cm2 (one replicate). The libraries prepared using these settings had comparable quality, so all were included in the final analysis. The Orb2B RRM1&2* library was prepared with a pulse of 400 mJ/cm2. Cells were pelleted immediately by spinning for 3 min at 16,100 × g at 4 °C in 1.5-mL tubes and were frozen in liquid nitrogen for further use. For each CLIP experiment constructs tagged with myc (the immunoprecipitation sample) and GFP (the control sample) were prepared in parallel. The iCLIP procedure was followed essentially as described (40), with minor modifications. To ensure the specificity of Orb2 CLIP data, two types of control samples were prepared. First, parallel samples from cells expressing the Orb2B protein C-terminally tagged with GFP were prepared with α-myc antibodies as an immunoprecipitation control. Second, an Orb2B RRM1&2* mutant sample was prepared to control for unspecific binding. Four replicate CLIP libraries were prepared from S2 cells expressing C-terminally myc-tagged Orb protein (isoform F) along with immunoprecipitation control samples from GFP-tagged protein.

Beads were prepared by cross-linking mouse monoclonal α-myc 9E10 antibodies (67) to Affi-Prep Protein A Support (Bio-Rad, 156-0005) beads. Briefly, beads were washed twice with 10 volumes of TBST buffer (1× Tris-buffered saline containing 0.04% Triton X-100) and were rotated at 15 rpm together with antibody (2.5 mg/1 mL beads) in 10 volumes of TBST for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, beads were washed three times with 10 volumes of TBST and three times with 10 volumes of 0.2 M sodium borate (pH 9.2). Antibodies were cross-linked to the beads with 20 volumes of freshly prepared 20 mM dimethyl pimelimidate (ThermoFisher Scientific, 21666) solution in 0.2 M sodium borate (pH 9.2) for 30 min at room temperature. Beads subsequently were washed twice with 10 volumes of 0.2 M Tris⋅HCl (pH 8) for 10 min at 15 rpm. Beads were additionally washed twice with 10 volumes of TBST and twice with 10 volumes of 0.1 M glycine (pH 2) (Sigma, G8898). Next, glycine was removed by washing three times with 10 volumes of TBST. Beads were stored in TBST containing 0.05% NaN3 (1:1, vol:vol) (Sigma, S2002) at 4 °C until use. Beads were equilibrated by washing three times with ice-cold iCLIP lysis buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS] containing protease [complete Mini inhibitor mixture tablets (Roche, 11 836 153 001)] and RNase inhibitors [anti-RNase, 1 uL/1 mL (Ambion, AM2692)]. Thirty microliters of settled beads per sample were used.

Cells were lysed by grinding with a plastic pestle in the presence of glass beads in 1 mL iCLIP lysis buffer with inhibitors. Two microliters of Turbo DNase (Ambion, AM2238) and 10 μL of 1:500 RNase I (Ambion, AM2295) in lysis buffer without inhibitors were added to each 1 mL of lysate. Reactions were mixed and incubated for 3 min at 37 °C with shaking at 1,100 rpm and then for 3 min on ice. Subsequently, the lysates were cleared by spinning for 20 min at 16,100 × g (Eppendorf centrifuge 5418R) at 4 °C. Lysates were added to beads and were rotated at 15 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C. Beads were washed twice with 1 mL high-salt buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4), 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8), 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS] and three times with 1 mL PNK buffer [20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2, 0.2% Tween20]. The supernatant was discarded, and 40 μL of dephosphorylation reaction mix was added to each tube. The dephosphorylation reaction mix comprised 8 μL of 5× PNK buffer (pH 6.5) [350 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 6.5), 50 mM MgCl2, 25 mM DTT], 1 μL T4 PNK with 3′phosphatase activity (New England BioLabs, M0201L), 1 μL RNasin ribonuclease inhibitor (Promega, N2511), and 30 μL RNase-free water. Reactions were incubated for 20 min at 37 °C with shaking (1,100 rpm) in an Eppendorf Thermomixer. Next, beads were washed rapidly once with 1 mL PNK buffer, once with 1 mL high-salt buffer for 1 min with rotation at 15 rpm at 4 °C, and twice rapidly with 1 mL PNK buffer. The supernatant was removed, and 40 μL of L3 linker ligation reaction mixture [8 μL 4× ligation buffer, 2 μL T4 RNA ligase (New England BioLabs, M0204S), 1 μL RNasin, 3 μL preadenylated L3-App linker (IDT, custom), 8 μL PEG400, 18 μL RNase-free water] was added to each tube. Reactions were incubated overnight at 16 °C with shaking at 1,100 rpm. On the next day the supernatant was removed, and beads were washed with 0.5 mL PNK buffer, twice with 1 mL high-salt buffer for 5 min with rotation at 15 rpm in a cold room, and twice rapidly with 1 mL PNK buffer. Twenty microliters of labeling reaction mixture [2 μL of 10× PNK buffer, 2 μL of P32γATP, 1 μL of T4 PNK enzyme (New England BioLabs, M0201L), 15 μL of RNase-free water)] was added to each tube, and reactions were incubated for 5 min at 37 °C. Beads were subsequently washed with 1 mL of high-salt buffer and 1 mL of PNK buffer. The supernatant was removed, and 20 μL of Novex reducing LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen) [5 μL NuPAGE LDS 4× sample buffer (Invitrogen, NP0007), 2 μL reducing agent (Invitrogen, NP0004), 13 μL RNase-free water] was added. Samples were incubated for 5 min at 70 °C, and the eluate was loaded on a Novex NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen, NP0321BOX). The gel was run in NuPAGE 1× MOPS SDS running buffer (Invitrogen, NP0001) at 180 V for ∼1.5 h at room temperature. Five microliters of Full-Range Rainbow Molecular Weight marker (Amersham, RPN800E) was loaded into a separate lane to allow size estimation and orientation. One lane between each sample was left empty to allow clean cutting of membrane pieces later in the protocol. The gel was transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Protran BA 85, 0.45 μm; Whatman, 10 401 197) using a Novex apparatus (Invitrogen) in 10% methanol NuPAGE transfer buffer (Invitrogen, NP0006-1) at 30 V for 2 h at room temperature. The membrane was rinsed with 1× PBS and was wrapped in Saran foil for exposure to autoradiography film (GE Healthcare, 28906845) overnight at 80 °C. The exposed film was used as a mask for cutting the membrane pieces contacting the protein–RNA complex for RNA extraction.

Membrane fragments were cut into small pieces with a clean scalpel blade and were transferred into 1.5-mL RNase-free tubes. Membrane pieces were washed with 1 mL cold PNK buffer for 10 min at 4 °C. The wash was removed, and 200 μL of PK buffer with 10 μL proteinase K (New England BioLabs, P8102S) was added to each tube to remove the protein from the complex and to allow RNA extraction. Digestion reactions were shaken at 1,100 rpm at 37 °C, for 20 min. Next, 200 μL of PK buffer containing urea was added to each tube and was shaken for an additional 20 min at 37 °C. Then the supernatant was added to 2-mL Phase Lock Gel Heavy tubes containing 400 μL of an RNA phenol/chloroform mixture. The tubes were shaken at 1,100 rpm at 30 °C for 5 min and were spun down for 5 min at 15,600 × g at room temperature. The upper layer containing RNA was moved to fresh nonstick RNase-free tubes. Then 40 μL of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.5), 0.5 μL glycogen, and 1 mL cold 100% ethanol were added to each tube and mixed, and RNA was precipitated overnight at −20 °C. The RNA was pelleted by spinning at 16,100 × g, 4 °C, for 15 min. The ethanol mixture was removed, and pellets were washed with 0.5 mL 80% ice-cold ethanol. All supernatant was removed carefully, and pellets were dried for 6 min at room temperature before resuspension in 6.25 μL of RNase-free water. Then 0.5 μL of 10 mM dNTP mixture and 0.5 μL of an appropriate 0.5 μM CLIP#RT primer were added to each sample in a PCR tube, and reactions were preincubated for 5 min at 70 °C in a PCR machine before fast cooling to 25 °C to unfold RNA molecules. Subsequently, 2.75 μL of reverse transcription reaction mixture [2 μL 5× RT buffer, 0.5 μL 0.1 M DTT, 0.25 μL SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, 180-80-044)] was added to each sample, and the reverse transcription PCR program was run (5 min at 25 °C, 20 min at 42 °C, 40 min at 50 °C, 5 min at 80 °C). cDNA was precipitated overnight by adding 40 μL of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.5), 0.5 μL glycogen, and 1 mL cold 100% ethanol to each 1.5-mL tube containing cDNA, mixing, and incubating at −20 °C. In most cases cDNA from the immunoprecipitation and control samples, labeled with different CLIP#RT primers (see the primer list at the end of the SI text), was mixed before precipitation.

On the following day cDNA was pelleted by spinning at 16,100 × g, 4 °C, for 15 min. The ethanol mixture was removed, and pellets were washed with 0.5 mL 80% ice-cold ethanol. All the supernatant was removed carefully, and pellets were dried for 6 min at room temperature before being resuspended in 6 μL of water. Then 6 μL of 2× TBE-urea loading dye was added to each tube, and samples were heated for 3 min at 80 °C. Meanwhile, 6% TBE-urea Novex gel was prepared by flushing the wells carefully with Novex 1× TBE running buffer (Invitrogen, LC6675), and all 12-μL samples were run in 1× TBE buffer at 180 V for 45 min at room temperature (with one empty lane between each sample to allow cutting). Six microliters of low molecular range DNA marker (New England BioLabs) diluted 1:30 in water was treated exactly as described for samples and was loaded to allow the gel regions to be cut according to size. After the run the marker lane was cut out and stained for 10 min in SYBR Green II, which stains ssDNA (2 μL in 10 mL 1× TBE buffer). Aligning the marker allowed three gel regions to be cut from each sample lane: upper, 120–200 nt; middle, 85–120 nt, and lower, 70–85 nt. From this point on, the samples from the different gel regions were treated separately. Each piece was placed in a 1.5-mL low-retention tube, incubated on dry ice for 2 min, and spun down for 15 min at 16,100 × g, 4 °C. Gel pieces then were crushed with a 1-mL syringe plunger in 400 μL of 1× TE buffer and were shaken for 1 h at 37 °C. The gel–buffer slurry was moved to dry ice for an additional 2 min and then was shaken again for 1 h at 37 °C. Costar SpinX columns (0.22 um cellulose acetate centrifuge tube filter; Corning 8161) were prepared by placing two round 1-cm glass prefilters (Whatman, 1823-010) into each column. The gel–buffer slurry was moved into the column and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 1 min at room temperature. Purified cDNA was precipitated overnight by adding 40 μL of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.5), 0.5 μL glycogen, and 1 mL cold 100% ethanol to each 1.5-mL tube containing cDNA, mixing, and incubating at −20 °C.

cDNA was pelleted by spinning at 16,100 × g, 4 °C for 15 min. The ethanol mixture was removed, and pellets were washed with 0.5 mL 80% ice-cold ethanol. All the supernatant was removed carefully, and pellets were dried for 6 min at room temperature. Pellets were resuspended in 8 μL of linker ligation mix (0.8 μL 10× CircLigase buffer II, 0.4 μL 50 mM MnCl2, 0.3 μL CircLigase II, and 6.5 μL water) (Epicentre, CL9025K) and were moved to PCR tubes. Reactions were incubated in the PCR machine for 1 h at 60 °C and were stored at 4 °C until the next step. Thirty microliters of oligo annealing mixture was added to each reaction (3 μL Fermentas 10× FastDigest buffer, 1 μL 10-μM cut oligo, and 26 μL water). Samples were incubated in the PCR machine at 95 °C for 2 min, and then the temperature was decreased stepwise from 95 °C to 25 °C in 1-min increments. When reactions reached 25 °C, 2 μL of BamHI FastDigest enzyme (Fermentas, FD0054) was added to each tube for 30 min at 37 °C. Reactions subsequently were moved to 1.5-mL low-retention tubes, and the DNA was precipitated overnight by adding 40 μL of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.5), 0.5 μL glycogen, and 1 mL cold 100% ethanol, mixing, and incubating at −20 °C. Next, DNA was pelleted by spinning at 16,100 × g, 4 °C, for 15 min. The ethanol mixture was removed, and pellets were washed with 0.5 mL 80% ice-cold ethanol. All supernatant was removed carefully, and pellets were dried for 6 min at room temperature before resuspension in 11 μL of water.

Two test PCR reactions [0.5 μL cDNA, 0.25 μL 10 mM P5/P3 Solexa primer mix, 5 μL 2× Phusion Premix (Thermo Scientific F-531L), 4.25 μL water] were assembled in a 10-μL volume of each sample to estimate the number of amplification cycles needed to obtain a reliable library. The PCR program was run (initial denaturation, 10 min at 95 °C; the estimated number of cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 65 °C and 30 s at 72 °C; and a final elongation for 3 min at 72 °C). After this step, PCR samples were handled in a separate room to avoid cross-contamination. Novex 5× TBE loading dye (2.5 μL) was added to each sample, and reactions were run on 6% native Novex polyacrylamide TBE gel in 1× TBE buffer for 30 min at 180 V at room temperature. The gel was stained with SYBR Green I (2 μL in 10 mL 1× TBE buffer). A 12.5-μL low molecular range DNA ladder diluted 1:30 in water was run in a separate lane to allow estimation of fragment size. For successful libraries one band was visible in each of the three lanes: a diffuse band, 150–200 nt, in the lane corresponding to upper gel band, a band of 145–150 nt in the lane corresponding to the middle gel band, and a band smaller than 145 nt in the lane corresponding to lower gel band from the cDNA purification step (a 128-bp band corresponds to primer dimer). The number of cycles needed to obtain a reliable library was estimated to be two less than the number that gives a signal in the test PCR.

To obtain a ready-for-sequencing library, 30 μL PCR reactions were assembled (10 μL cDNA, 0.75 μL 10 mM P5/P3 Solexa primer mix, 15 μL 2× Phusion Premix, 4.25 μL water) and were run with the estimated cycle number. Subsequently, 7.5 μL of 5× TBE buffer was added to each reaction, and samples were run on 6% native Novex polyacrylamide TBE gel in 1× TBE buffer for 30 min at 180 V at room temperature. A 10-μL low molecular range DNA ladder diluted 1:30 in water was run in a separate lane to allow estimation of fragment size. The gel was stained for 10 min in SYBR Green I (2 μL in 10 mL 1× TBE buffer), which stains dsDNA. cDNA was gel purified by cutting bands and moving them separately to 1.5-mL low-retention tubes. The tubes were put on dry ice for 2 min and were spun down for 15 min at 16,100 × g, 4 °C. Gel pieces then were crushed with a 1-mL syringe plunger in 400 μL 1× TE buffer and were shaken for 1 h at 37 °C. The gel–buffer slurry was moved to dry ice for an additional 2 min and was shaken again for 1 h at 37 °C. Costar SpinX columns were prepared by placing two round 1-cm glass prefilters in each column. The gel–buffer slurry was moved into the column and was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 1 min at room temperature. Purified cDNA was precipitated overnight by adding 40 μL of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.5), 0.5 μL glycogen, and 1 mL cold 100% ethanol to each 1.5-mL tube containing cDNA, mixing, and incubating at −20 °C. Next, DNA was pelleted by spinning at 16,100 × g, 4 °C, for 15 min. The ethanol mixture was removed, and the pellets were washed with 0.5 mL 80% ice-cold ethanol. The supernatant was removed carefully, and pellets were dried for 6 min at room temperature before resuspension in 30 μL water. The DNA concentration was assessed from the native 6% TBE gel. For sequencing, samples from the upper and middle cDNA bands were combined (1:1, vol:vol). Samples were deep sequenced using Illumina sequencing technology with a read length of 76 or 100 nt. Sequencing was performed at the CSF NGS Unit (www.vbcf.ac.at).

All sequencing data were submitted to the GEO database (accession no. GSE59611).

Preparation of RNA-Seq samples.