Abstract

The engineered Salmonella typhimurium ΔppGpp (S.t ΔppGpp) has been studied in terms of its ability to carry imaging probes (bacterial luciferase, Lux) for tumor imaging or carry therapeutic molecules (Cytolysin A) to kill cancer cells. To establish a novel cancer therapy, bacterial therapy was combined with radiotherapy using the attenuated strain S.t ΔppGpp/pBAD-ClyA. Radiotherapy (21Gy) contributed to S. typhimurium colonization in a colon tumor (CT26) model of BALB/c mice. The combination of bacterial therapy and radiotherapy treatments reduced tumor growth compared with only bacterial therapy.

Keywords: bacterial luciferase, cytolysin A, radiotherapy, Salmonella typhimurium ΔppGpp, tumor

Introduction

In the past several decades, radiotherapy and chemotherapy have been employed as major tool for cancer treatment [1]. However, both radiotherapy and chemotherapy lead to so many problems in carcinoma patients, such as cytotoxicity, cancer cell resistance, and hypoimmunity, and they also failed to completely kill all cancer cells in most cases. Because it is difficult to acutely and/or chronically administer radiotherapy and chemotherapeutic agent to hypoxic and acidic regions in tumors, incomplete tumor targeting, inadequate tissue penetration, and limited toxicity in all cancer cells occurs [2]. Thus, viral or other vectors are used for selective tumor targeting or cancer therapy.

Certain strains of bacteria may selectively colonize and grow in tumors, such as Escherichia coli [3,4,5], Salmonella [6,7,8], and Clostridium [9]. A number of studies have reported that these bacteria have been engineered to express a reporter gene or cytotoxic protein that is used in tumor imaging or tumor treatment [10]. These genetically modified bacteria multiply in tumors 1000-fold greater than in normal tissue [6]. S. typhimurium has been used as a carrier to transfer converting enzymes and antigens to tumors [11].

The attenuated S. typhimurium ΔppGpp (guanosine 5′-diphosphate-3′-diphosphate) strain carries a pBAD plasmid that may produce the cytotoxic protein cytolysis A (ClyA) to kill tumor cells and bacterial luciferase (Lux) to generate imaging signals [12]. ClyA is 34-kDa pore-forming hemolytic protein that can be produced by E. coli and the attenuated strain S. typhimurium without posttranslational modification [13]. The cytotoxicity of ClyA towards mammalian cells and macrophages induces cell apoptosis. Nguyen et al. (2010) already demonstrated that attenuated strain S.t ΔppGpp/pBAD-ClyA was located in hypoxic and necrotic areas in tumors and expressed ClyA protein [12]. A major problem in radiotherapy is whether or not it affects cytotoxin-expressing Salmonella localized in a tumor.

Therefore, the effect of radiotherapy was observed after tail vein injection of attenuated strain S.t ΔppGpp/pBAD-ClyA in a mouse model of colon cancer to search for a more sensitive and efficient cancer therapy. The aim was to evaluate the efficiency of S.t ΔppGpp/pBAD-ClyA therapy for suppression of tumor growth after radiotherapy.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

The murine CT26 colon carcinoma cell was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (CRL-2638). The CT26 cells were grown in high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

Plasmid construct

The expression plasmid pBAD-RLuc8 has been previously described [12]. The clyA gene was amplified with the primer pair 5′-AGTCCATGGTTATGACCGGAATATTTGC-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-GATGTTTAAACTCAGACGTCAGGAACCTC-3′ (reverse primer) using the S. typhimurium genotype as a template. The PCR products were digested by NcoI and PmeI restriction enzymes, and RLuc8 was replaced by clyA in the same site.

Bacterial preparation

The attenuated Salmonella typhimurium strains SHJ2037 is a ΔppGpp, and it was kindly provided by R. M. Hoffman (AntiCancer, San Diego, CA, USA) [12]. The bacterial strains were grown in LB (Luria Bertani) media (Difco Laoratories, Detroit, MI, USA) containing appropriate antibiotics (S.t ΔppGpp/pBAD-ClyA, ampicillin, 100 µg/ml;S.t ΔppGpp Lux, kanamycin, 50 µg /ml; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). The strains were kept in LB media containing glycerol (20%) and stored at −80°C. The LB plate was also supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. A single colony was picked out from the plate and dipped in 10 ml LB/antibiotic solution incubated in a shaking incubator (37°C, 200 rpm) before bacterial injection. On the day of injection, 2.5% of bacterial solution was applied to a fresh culture in new media (LB/antibiotics liquid media) and incubated in a shaking incubator (37°C, 200 rpm) for 4 h. The bacteria were centrifuged (5,000 rpm, 10 min) and washed with PBS. The bacterial solution was analyzed by spectrophotometer (600 nm), and the bacterial number was calculated (1 OD means 0.8 × 109 CFU). The S.t ΔppGpp (3 × 107 CFU) was suspended in 100 µl PBS and injected into the lateral tail vein of the mouse tumor model with a 1-cc insulin syringe.

Animal models

The BALB/c mice (5- to 6-week-old male) were purchased from Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center (Guangzhou, Guangdong province, China), and cages, food, drinking water, and bedding were sterilized by autoclaving. All experiments involving mice were performed according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. To obtain a highly efficient therapeutic effect, fresh highly invasive bacteria were used. Anesthesia of mice was performed using isoflurane (2%) for imaging or a mixture of ketamine (200 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) for surgery. The CT26 cells (3 × 106) were harvested and suspended in 100 µl of PBS, and subcutaneously injected into mice for generation of colon tumors. The tumor volumes (mm3) were estimated using the formula (L × H × W)/2, where L was the length, W was the width, and H was the height.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy was commenced when the longest diameter of the subcutaneous tumor reached approximately 10 mm or its volume reached 150 mm3. A 6-MV X-ray was used via a linear accelerator (Clinac 1800, Varian, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The source to skin distance was one meter with a field size of 5 × 5 cm2 and a dose rate of 3 Gy/min. Water equivalent boluses with a thickness of 1 cm were placed under and above the mouse thigh bearing the tumor to establish dose homogeneity. The radiation was delivered using two anterior-posterior/posterior-anterior parallel opposing fields. To assess the tumor regression effects of different radiation doses, we irradiated tumors in fractions of 7 Gy, and the radiotherapy was performed every 3 days until the total doses reached 21 Gy.

Optical bioluminescence imaging

The mice were anesthetized and placed in a light-tight chamber of a xenogeny IVIS imaging system (Caliper). Photographs of mice were analyzed with the Living Image 4.0 software (Caliper). A region of interest was selected manually based on the signal intensity. The area of the region of interest was kept constant, and the intensity was recorded as the total photons count within each region of interest.

Data analysis

The bioluminescence data were analyzed with the Living Imaging 4.0 software (Caliper), and all the statistical calculations were analyzed with the Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). The two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to determine the statistical significances of differences in primary tumor growth between the control and treatment groups. A P value<0.05 was considered significant for all analyses. The survival data were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier curve and long- rank test. All data are expressed as means ± standard deviation.

Results

Engineered S. typhimurium target subcutaneously implanted into tumors after RT

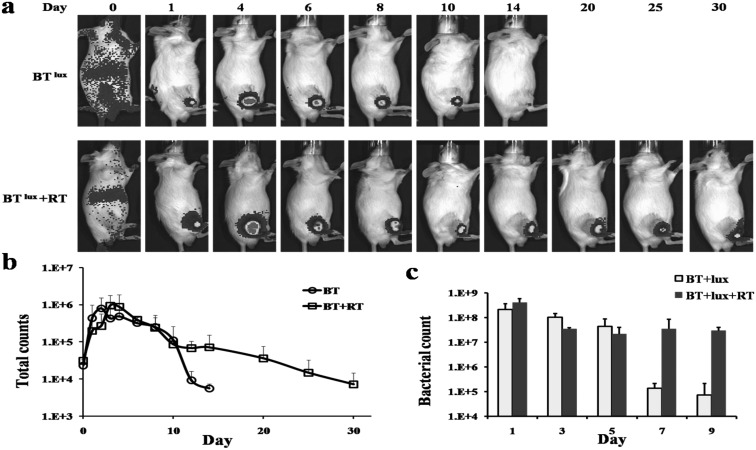

The S.t ΔppGpp-Lux was injected into tumor-bearing mice via the tail vein (BTlux), and expression of Lux was measured by IVIS for ever day. The bioluminescence was imaged in the BTlux and BTlux plus RT group. The bioluminescence signal was only detected in the tumor area of mice at day 1 after injection of S.t ΔppGpp-Lux (Fig. 1 a). The signal reached its peak between day 3 and day 5 in the BTlux group and BTlux plus RT group. The bioluminescence signal of the BTlux group was markedly decreased from day 10, but the signal of the BTlux plus RT group was maintained for than 24 days. The signal of the BTlux plus RT group was stronger than that of the BTlux group during the whole experiment (Fig. 1b). The bacterial counts of tumors also demonstrated that RT contributed to S. typhimurium colonization for tumor targeting (Fig. 1c). Our previous study indicated that E. coli could colonize tumors and survive after RT treatment in a mouse tumor model, and the present result further confirmed this [5].

Fig. 1.

Imaging and effect of Lux-expressing S. typhimurium in a mouse model of colon cancer after radiotherapy. a, Noninvasive in vivo imaging of bacterial bioluminescence. b, Changes in signal intensity. c, Changes in bacterial count of tumor.

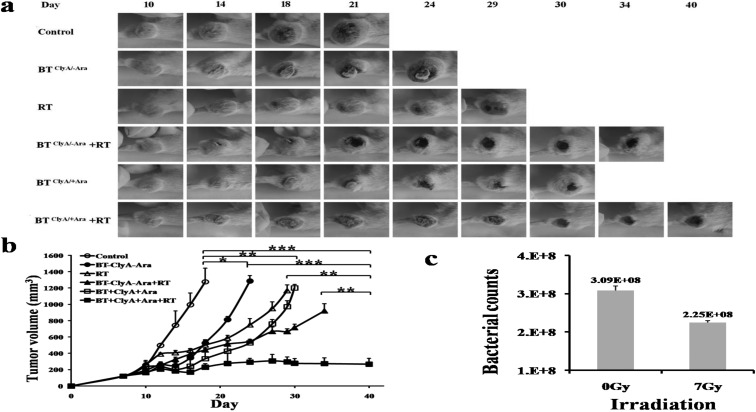

Tumor suppression by engineered S. typhimurium expressing ClyA

CT26 cells were subcutaneously injected into BALB/c mice to establish our mouse model of colon cancer at day 0, and then we divided the mice into three groups (control, BTClyA/-Ara, and BTClyA/+Ara). The tumor-bearing mice in the BTClyA/-Ara and BTClyA/+Ara group were injected with 3 × 107 CFU S.t ΔppGpp/pBAD-ClyA via the tail vein at day 10, and the control group was injected with PBS. The mice in the BTClyA/+Ara group were received an intraperitoneal injection of L-arabinose to every day from day 13 for activation of the pBAD promoter and production of ClyA. Tumor growth was suppressed in the BTClyA/-Ara or BTClyA/+Ara groups compared with the control group, and the efficiency of suppression of tumor growth was higher in the BTClyA/+Ara group than in the BTClyA/-Ara group, but the tumor volume still was increased (Fig. 2a). ClyA was secreted by S.t ΔppGpp/pBAD-ClyA after induction with L-arabinose, but it only inhibited tumor growth; it did not completely eliminate tumors.

Fig. 2.

Therapeutic effect of ClyA-expressing S.t ΔppGpp in tumor-bearing mice (n=5 in each group). a, Photographs of subcutaneous tumors in representative mice. b, Changes in tumor volume. c, Changes of bacterial counts after RT (7 Gy) in vitro.

Tumor suppression by engineered S. typhimurium combined with RT

To evaluate the efficiency of tumor suppression with the combination of BT and RT, tumor-bearing BALB/C mice were transplanted with CT26 carcinoma cells and subjected to RT treatment after S.t ΔppGpp/pBAD-ClyA injection. The mouse model of colon cancer was irradiated with a single dose of 7 Gy at days 1, 4, and 7 after BTClyA/+Ara treatment, and the total radiation dose was 21 Gy. BTClyA/+Ara plus RT treatment reduced tumor growth compared with only BTClyA/+Ara or the control group (Fig. 2a). The tumor volume was significantly decreased by BTClyA/+Ara plus RT, but tumors still could not be eliminated (Fig. 2b).

Effect of RT on the S.t ΔppGpp pBAD-ClyA strain

To observe the effect of RT on S.t ΔppGpp/pBAD-ClyA growth, plates were divided into 0 Gy and 7 Gy irradiation group, with each group having 3 plates containing 3 × 108 CFU. After irradiation, the bacteria were spread onto agar plates and incubated for 18 h in a 37°C incubator. The bacterial counts were significantly affected by RT (Fig. 2c, P=0.02). This result indicated that S.t ΔppGpp/pBAD-ClyA was sensitive to RT in vitro.

Discussion

Bacteria can become a new carrier for anticancer treatments, because they can target tumors and colonize within hypoxia area in tumors. Various explanations have been proposed for this, including that disorders of the vascular system cause inefficient transfer of oxygen and nutrients in tumors, which provides favorable conditions for colonization by anaerobic bacteria and facultative anaerobic bacteria. Furthermore, superior nutrient such as purine are released by necrotic cell in hypoxia zones of tumor, TGF-β (tumor growth factors β) is secreted in tumors, which reduced exposure to antibodies under low oxygen and high interstitial pressure, and the bactericidal activity of macrophages and neutrophils is impaired [14]. In this study, tumor images were obtained with the bioluminescence signal after injection of the S.t ΔppGpp-Lux strain, and radiotherapy extended the bacterial colonization time in tumors.

The S.t ΔppGpp/pBAD-ClyA showed high efficiency to suppress tumors, and this was mainly due to the ability of ClyA to penetrate the immune cell barrier in colonized tumors to kill the viable tumors. The pBAD promoter can effectively reduce the damage to normal tissue caused by ClyA, because it activates and produces ClyA in response to L–arabinose after the bacteria reach the tumors. However, S. typhimurium on its own can also affect tumor growth without ClyA. Although it showed a similar therapeutic effect, the therapeutic efficiency was lower than that in Nguyen’s report, and this may be related to the dose of cells injected into the tumors [12]. Various explanations have been proposed for how bacteria suppress tumors, including consumption of nutrients such as essential amino acids in tumors and production of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and toxins that suppress the formation of tumor blood vessels, which cause nonspecific inflammation that activates antitumor T cells in the region of the bacterial colonization, and penetrate deeply into the tumor tissue with flagellum motility [14].

Hypoxic cells are up to three times more resistant to ionizing radiation than normoxic cells [15]. Theoretically, radiation results in the transformation of tumor cell to anoxia cells, so hypoxia may be sustained or even increased after RT [1]. Therefore, the presence of S. typhimurium in the tumor is extended by RT. Our previously study already proved that E. coli could colonize tumors and survive after RT treatment in a mouse tumor model [16].

Traditional RT is given to patients at 1.8–2 Gy per day for 7 or 8 weeks, with cumulative dose of up to 65–70 Gy. A high radiation dose is usually accompanied by damage to the immune system and normal tissue. S.t ΔppGpp/pBAD-ClyA greatly improved the efficiency of the RT and significantly inhibited tumor growth, and the total cumulative radiation dose was reduced to 21 Gy, which is lower than the traditional dosage. However, S.t ΔppGpp/pBAD-ClyA combined with RT could not completely eliminate tumor cells, and this was different from a previous report that used an E.coli K-12/pA-ClyA strain [16]. This main reason for this is probably related to the different bacteria strains, because S.t ΔppGpp/pBAD-ClyA is more sensitive to RT than the E.coli K-12/pA-ClyA strain.

In conclusion, bacterial cancer therapy possessed many advantages in cancer therapy such as low production cost and less harm of tissue. Although the genetically engineered S. typhimurium could not completely eliminate tumors in mouse model of colon cancer, combination with RT contributes to bacterial colonization and tumor suppression. Therefore, exploration of bacterial therapy is quite valuable for clinical treatment of cancer, and combination of BT and RT treatments will probably become a new strategy for cancer therapy.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors has any financial or personal relationships that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of the paper.

Acknowledgments

SNJ was supported by the Science and Technology Program (ZDXM20130067) of Hainan, China. XDL was supported by the Nature Fund (314040), Social and Scientific Development Program (SF201421), and Science and Technology Program (ZDXM2015065) of Hainan, China.

References

- 1.Harrison L.B., Chadha M., Hill R.J., Hu K., Shasha D.2002. Impact of tumor hypoxia and anemia on radiation therapy outcomes. Oncologist 7: 492–508. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-6-492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wachsberger P., Burd R., Dicker A.P.2003. Tumor response to ionizing radiation combined with antiangiogenesis or vascular targeting agents: exploring mechanisms of interaction. Clin. Cancer Res. 9: 1957–1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Min J.J., Kim H.J., Park J.H., Moon S., Jeong J.H., Hong Y.J., Cho K.O., Nam J.H., Kim N., Park Y.K., Bom H.S., Rhee J.H., Choy H.E.2008. Noninvasive real-time imaging of tumors and metastases using tumor-targeting light-emitting Escherichia coli. Mol. Imaging Biol. 10: 54–61. doi: 10.1007/s11307-007-0120-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Min J.J., Nguyen V.H., Kim H.J., Hong Y., Choy H.E.2008. Quantitative bioluminescence imaging of tumor-targeting bacteria in living animals. Nat. Protoc. 3: 629–636. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu Y.A., Shabahang S., Timiryasova T.M., Zhang Q., Beltz R., Gentschev I., Goebel W., Szalay A.A.2004. Visualization of tumors and metastases in live animals with bacteria and vaccinia virus encoding light-emitting proteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 22: 313–320. doi: 10.1038/nbt937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Low K.B., Ittensohn M., Le T., Platt J., Sodi S., Amoss M., Ash O., Carmichael E., Chakraborty A., Fischer J., Lin S.L., Luo X., Miller S.I., Zheng L., King I., Pawelek J.M., Bermudes D.1999. Lipid A mutant Salmonella with suppressed virulence and TNFalpha induction retain tumor-targeting in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 17: 37–41. doi: 10.1038/5205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pawelek J.M., Low K.B., Bermudes D.2003. Bacteria as tumour-targeting vectors. Lancet Oncol. 4: 548–556. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(03)01194-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao M., Yang M., Li X.M., Jiang P., Baranov E., Li S., Xu M., Penman S., Hoffman R.M.2005. Tumor-targeting bacterial therapy with amino acid auxotrophs of GFP-expressing Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 755–760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408422102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agrawal N., Bettegowda C., Cheong I., Geschwind J.F., Drake C.G., Hipkiss E.L., Tatsumi M., Dang L.H., Diaz L.A., Jr, Pomper M., Abusedera M., Wahl R.L., Kinzler K.W., Zhou S., Huso D.L., Vogelstein B.2004. Bacteriolytic therapy can generate a potent immune response against experimental tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 15172–15177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406242101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dang L.H., Bettegowda C., Huso D.L., Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B.2001. Combination bacteriolytic therapy for the treatment of experimental tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 15155–15160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251543698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yam C., Zhao M., Hayashi K., Ma H., Kishimoto H., McElroy M., Bouvet M., Hoffman R.M.2010. Monotherapy with a tumor-targeting mutant of S. typhimurium inhibits liver metastasis in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. J. Surg. Res. 164: 248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen V.H., Kim H.S., Ha J.M., Hong Y., Choy H.E., Min J.J.2010. Genetically engineered Salmonella typhimurium as an imageable therapeutic probe for cancer. Cancer Res. 70: 18–23. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wai S.N., Lindmark B., Söderblom T., Takade A., Westermark M., Oscarsson J., Jass J., Richter-Dahlfors A., Mizunoe Y., Uhlin B.E.2003. Vesicle-mediated export and assembly of pore-forming oligomers of the enterobacterial ClyA cytotoxin. Cell 115: 25–35. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00754-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loeffler M., Le’Negrate G., Krajewska M., Reed J.C.2007. Attenuated Salmonella engineered to produce human cytokine LIGHT inhibit tumor growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 12879–12883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701959104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans S.M., Jenkins W.T., Shapiro M., Koch C.J.1997. Evaluation of the concept of “hypoxic fraction” as a descriptor of tumor oxygenation status. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 411: 215–225. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5865-1_26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang S.N., Phan T.X., Nam T.K., Nguyen V.H., Kim H.S., Bom H.S., Choy H.E., Hong Y., Min J.J.2010. Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis by a combination of Escherichia coli-mediated cytolytic therapy and radiotherapy. Mol. Ther. 18: 635–642. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]