Abstract

Hormone receptor-positive (HR+) breast cancers express the estrogen (ERα) and/or progesterone (PgR) receptors. Inherited single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in ESR1, the gene encoding ERα, have been reported to predict tamoxifen effectiveness. We hypothesized that these associations could be attributed to altered tumor gene/protein expression of ESR1/ERα and that SNPs in the PGR gene predict tumor PGR/PgR expression. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded breast cancer tumor specimens were analyzed for ESR1 and PGR gene transcript expression by the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction based Oncotype DX assay and for ERα and PgR protein expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and an automated quantitative immunofluorescence assay (AQUA). Germline genotypes for SNPs in ESR1 (n = 41) and PGR (n = 8) were determined by allele-specific TaqMan assays. One SNP in ESR1 (rs9322336) was significantly associated with ESR1 gene transcript expression (P = 0.006) but not ERα protein expression (P > 0.05). A PGR SNP (rs518162) was associated with decreased PGR gene transcript expression (P = 0.003) and PgR protein expression measured by IHC (P = 0.016), but not AQUA (P = 0.054). There were modest, but statistically significant correlations between gene and protein expression for ESR1/ERα and PGR/PgR and for protein expression measured by IHC and AQUA (Pearson correlation = 0.32–0.64, all P < 0.001). Inherited ESR1 and PGR genotypes may affect tumor ESR1/ERα and PGR/PgR expression, respectively, which are moderately correlated. This work supports further research into germline predictors of tumor characteristics and treatment effectiveness, which may someday inform selection of hormonal treatments for patients with HR+ breast cancer.

Keywords: estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, genotype, RT-PCR, immunohistochemistry, AQUA

the estrogen (ERα) and progesterone (PgR) receptors are members of the family of nuclear hormone receptors (HR) and function as transcription factors in the nucleus when activated (37). The natural ligand 17β-estradiol and the selective estrogen receptor modulator tamoxifen exert their effects through the binding of ERα. Upon binding of an agonist to ERα, PgR associates with the activated ERα and modulates its transcriptional activity (33).

Tamoxifen is routinely used for treatment of early-stage and metastatic HR+ (ERα and/or PgR) breast cancer; however, its efficacy varies among patients. In the adjuvant setting tamoxifen decreases breast cancer recurrence by up to 40% in women whose tumors are HR+, but not women whose tumors are HR-negative (13). Not all HR+ tumors respond to tamoxifen, though tumors with higher ERα expression are somewhat more likely to respond (13). In women with advanced breast cancer, ∼40% of HR+ tumors are associated with de novo resistance to hormonal treatment, which may be partially attributable to activating somatic mutations in ESR1 (40, 43).

The mechanisms underlying variability in tamoxifen efficacy in patients with HR+ breast cancer have not been well described. Possible reasons, other than the level of ER/PgR expression and existence of somatic ESR1 mutations, include somatic differences in Her2 status, coactivators/repressors, and activation of alternative signaling pathways (5, 25, 53). It is also possible that the patient's germline genome contributes to this variability. Patients who inherit diminished activity single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in CYP2D6, who have lower concentrations of an active tamoxifen metabolite, endoxifen, may experience inferior treatment benefit, though results of these pharmacogenetic studies are highly discordant (17, 26, 39, 41).

ERα and PgR are encoded by the polymorphic ESR1 and PGR genes, both of which harbor potentially functionally consequential SNPs that affect females' risk of breast (2, 15, 29) and other reproductive (4, 6, 30) cancers. SNPs in these genes have also been associated with the efficacy and toxicity of hormonal treatment, including tamoxifen and the aromatase inhibitors (21, 23, 27, 35, 36, 48) in addition to associations with changes in serum lipid concentrations (14, 22) and bone mineral density (10) during estrogen replacement therapy. The mechanisms underlying these pharmacogenetic associations have not been determined.

We hypothesized that SNPs in ESR1 and PGR may affect response to tamoxifen by altering gene and protein expression levels within the patient's tumor. To test this hypothesis we evaluated associations between candidate germline polymorphisms in ESR1 and PGR and tumor gene (ESR1 and PGR) and protein (ERα and PgR) expression in a cohort of subjects with HR+ breast cancer treated on an observational study of tamoxifen therapy (23). Using the same cohort we also determined the correlation between gene and protein expression and between two alternative methods for quantifying protein expression: immunohistochemistry (IHC) and automated quantitative immunofluorescence analysis (AQUA).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples.

Archived formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tumor specimens were obtained from a subset of subjects who participated in a prospective multicenter observational study designed to identify associations between inherited SNPs in various genes and tamoxifen-related phenotypes. Complete details regarding the design and conduct of the parent study have been previously reported (23). All patients enrolled on the original trial had provided written informed consent prior to participation, including analysis of germline SNPs in multiple candidate genes.

Tumor specimens were obtained from the Department of Pathology at the University of Michigan (UM) for study participants who enrolled in the trial and had their breast cancer surgery performed at UM. The UM Institutional Review Board provided a waiver of informed consent to obtain primary tumor specimens for biomarker expression analysis. After pathological review, a tumor microarray (TMA) was constructed with the methodology of Nocito et al. (34). Each case was represented by two 1 mm diameter cores, obtained from the most representative, nonnecrotic area of the tumor based on hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Genotyping.

Whole blood was obtained from all patients at the time of study enrollment. Germline DNA was extracted from whole blood and genotyping was performed using the BioTrove OpenArray platform (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as previously described (21) for 41 SNPs in ESR1 and eight SNPs in PGR (Supplementary Data).1 SNPs were selected based on a literature review of known polymorphisms conducted at the time of project conceptualization. All genetic data underwent rigorous quality control: ∼15% of samples were genotyped in duplicate and SNPs with call rate <90%, minor allele frequency <0.05, or P value from Hardy-Weinberg analysis <0.001 were excluded from the analysis.

ESR1 and PGR gene transcript expression measurement.

Gene transcript expression of ESR1 and PGR were quantified using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on a subset of the available tumor blocks. To assess gene expression, 10 μm sections of each block were sent to Genomic Health (Redwood City, CA) for analysis with the commercially available 21 gene Recurrence Score assay (Oncotype DX) (38). Raw fluorescence data for each gene were obtained and normalized using the expression levels of the five reference genes.

ERα and PgR protein expression measurement.

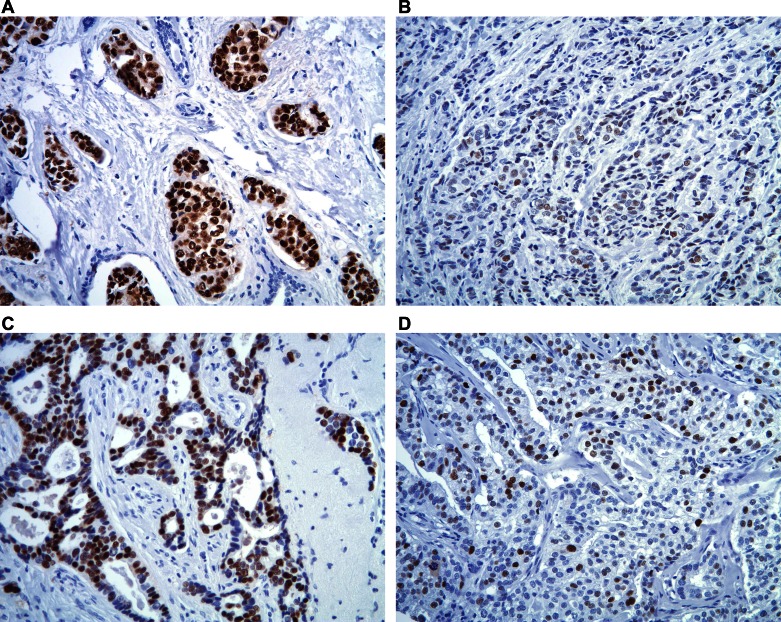

IHC staining was performed on the DAKO Autostainer (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) using DAKO Envision+ and diaminobenzadine as the chromogen. Deparaffinized sections of formalin-fixed TMA at 5 μm thickness were labeled with either anti-ERα (mouse monoclonal antibody, 1:50, DAKO, M-7047, clone 1D5) or anti-PgR A (mouse monoclonal antibody, 1:100, DAKO, M-3569, clone PgR636). Representative images of tumors with high and low IHC staining for ERα and PgR can be found in Fig. 1. Microwave citric acid epitope retrieval was used for all antibodies. Appropriate negative (no primary antibody) and known positive controls (breast carcinoma) were stained in parallel with each set of tumors studied.

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for estrogen receptor (ERα) and progesterone receptor (PgR). Representative images of tumors with high and low staining for ERα (high staining, A; low staining, B) and PgR (high staining, C; low staining, D).

IHC scoring was performed by the method of Harvey et al. (19) for ERα and PgR by two reviewers (D. T. and N. L. H.), who independently scored each TMA spot. Values ranged from 0 (for negative) to 8 (for strongly positive in >67% of samples). When the values for the two spots from a single tumor specimen differed, the higher of the two values was used. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved via repeat review of the TMA spots in question by the reviewers to reach consensus.

For assessment of ERα and PgR expression using the AQUA system, sections of TMA were subjected to double immunofluorescence staining as previously described (11). In brief, after deparaffinization and rehydration, TMA slides were subjected to microwave epitope retrieval, then endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 2.5% (vol/vol) H2O2 in methanol for 30 min. Nonspecific binding of the antibodies was extinguished by a 30 min incubation with “Background Sniper” (BioCare Medical, Concord, CA). The TMA slide was then incubated with the tumor-specific antibody, wide-spectrum cytokeratin (DAKO, Rabbit polyclonal antibody, Z-0622 1:250) overnight at 4°C. Slides were then incubated with the same antibody to ERα or to PgR as was used for IHC, at the same concentrations, for 60 min at room temperature. Slides were then incubated with a combination of goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to AF555 (Molecular Probes, Carpinteria, CA; A21424, 1:200) in goat anti-mouse Envision+ (DAKO) for 60 min at room temperature. The target image was developed by a CSA reaction of Cy5 labeled tyramide (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA; 1:50), then stained with the DNA staining dye 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) in a nonfading mounting media (ProLong Gold, Molecular Probes). The slides were allowed to dry overnight in a dark dry chamber and the edges were sealed.

The AQUA system (HistoRx, New Haven, CT) was used for the automated image acquisition and analysis. Briefly, images of each TMA core were captured with an Olympus BX51 microscope at three different extinction/emission wavelengths. Within each TMA spot, the area of tumor was distinguished from stromal and necrotic areas by creating a tumor specific mask from the anti-cytokeratin protein, which was visualized from Alexa Fluor 555 signal. The DAPI image was then used to differentiate between the cytoplasmic and nuclear staining within the tumor mask. Finally, the fluorescence pixel intensity of the ERα and PgR protein/antibody complex was obtained from the Cy5 signal and reported as pixel intensity. To determine the value for each tumor specimen, the pixel intensities from the two corresponding TMA spots were averaged.

Statistical analysis.

Linear regression was used to compare mean gene transcript expression of ESR1 and PGR across ESR1 and PGR genotypes, respectively, assuming an additive genetic model. Positive genetic associations were then tested for associations with ERα and PGR protein expression by IHC and AQUA in secondary analyses. Associations between ESR1/ERα and PGR/PgR expression by RT-PCR (gene expression), IHC, and AQUA (protein expression) were performed using Pearson's correlation coefficient. For the primary pharmacogenetic analysis of gene expression a more conservative, though not Bonferroni corrected, P value of <0.01 was considered statistically significant. For all other analyses a typical, uncorrected P value threshold of <0.05 was used.

RESULTS

Subjects and SNPs included in analysis.

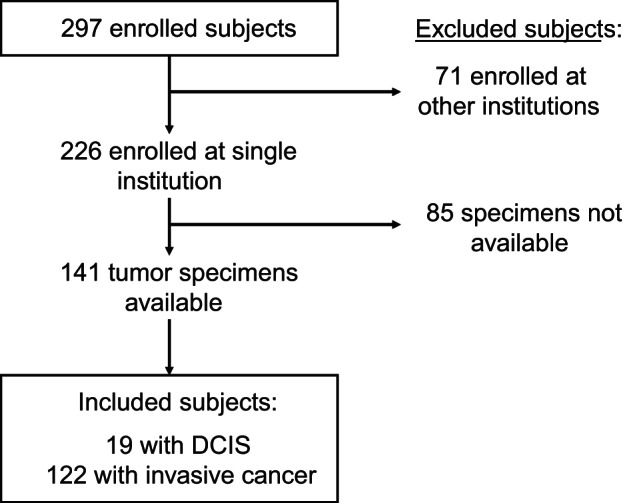

Of the 297 subjects enrolled in the parent multicenter study, 226 were enrolled at the UM, 141 of whom had their surgery performed at UM and had FFPE tumor specimens available (Fig. 2). Clinical and pathological characteristics of the evaluable subjects are listed in Table 1. Of the included samples, 19 subjects had ductal carcinoma in situ and 122 had invasive cancer. Of the three subjects with ER-negative invasive tumors, one was PgR positive, one had a contralateral ER-positive tumor, and one subject's primary tumor was ER/PR negative, but ER-positive cells were detected in an involved lymph node. Not all tumor specimens could be evaluated by both protein expression methods because of loss of tumor cores from the TMA or lack of tumor in the evaluated section. Patients were genotyped for 41 SNPs in ESR1 and eight SNPs in PGR. SNPs were eliminated during quality control due to inadequate call rate (<90%, n = 6), minor allele frequency (<5%, n = 7), or significant deviation from expected Hardy-Weinberg proportions [P < 0.001 (0.05/41), n = 2], leaving 34 SNPs for analysis, as reported in the Supplementary Data.

Fig. 2.

Consort diagram depicting patient flow from the observational clinical study into this secondary analysis. DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological characteristics of evaluable subjects in this study (n = 141)

| Characteristic | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Histology | DCIS | 19 (13.5) |

| invasive carcinoma | 122 (86.5) | |

| Grade of invasive carcinoma | grade 1 | 27 (22.1) |

| grade 2 | 62 (50.8) | |

| grade 3 | 19 (15.6) | |

| unknown | 14 (11.5) | |

| Stage of invasive carcinoma | I | 71 (58.2) |

| II | 32 (26.2) | |

| III | 19 (15.6) | |

| Clinical ERα status | positive (≥1%) | 132 (93.6) |

| negative | 3 (2.1) | |

| unknown | 6 (4.3) | |

| Clinical PgR status | positive (≥1%) | 104 (73.8) |

| negative | 18 (12.8) | |

| unknown | 19 (13.5) | |

DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; ER, estrogen receptor; PgR, progesterone receptor.

Associations between ESR1 SNPs and gene transcript expression.

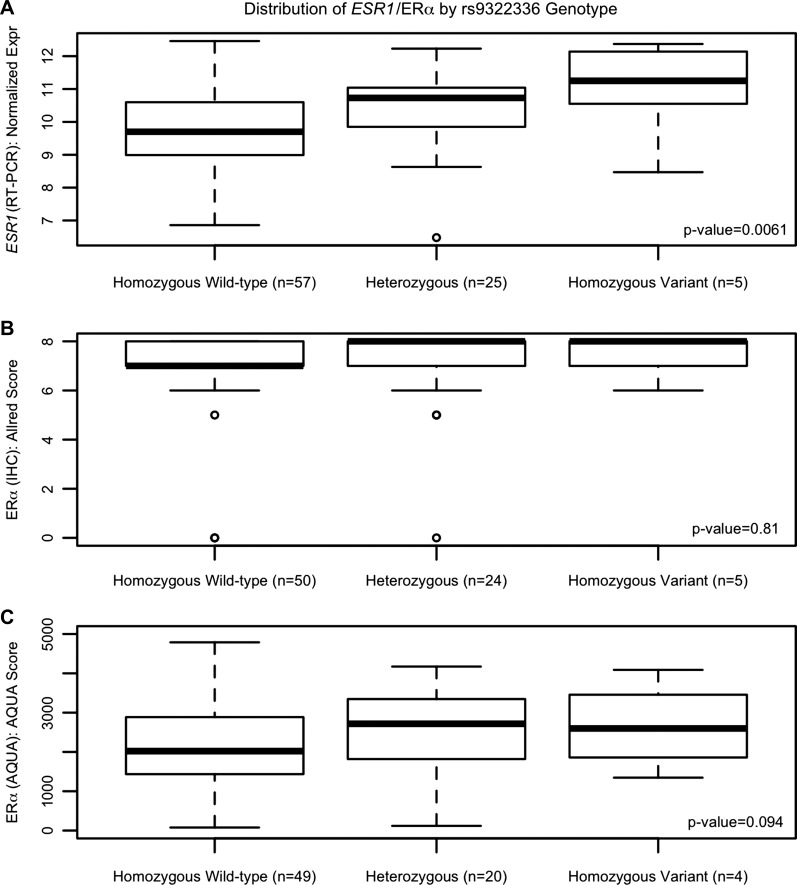

After proper quality control, germline genotypes for 27 ESR1 SNPs were evaluated for association with ESR1 gene transcript expression in breast cancer tissue from 93 patients. The SNPs analyzed, number of patients in each genotype group, mean expression levels by genotype, and results from the linear regression analysis are reported in Table 2. There was a statistically significant association between the ESR1 SNP rs9322336 and ESR1 gene transcript expression; for each variant allele a patient carries (0, 1, or 2) their relative ESR1 transcript expression increased by 0.640 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.193, 1.087, P = 0.0061, Fig. 3A]. The rs9322336 SNP was then tested for an association with ERα protein expression measured by IHC and AQUA; however, no significant association was detected [IHC: effect per variant allele = 0.072 (95% CI: −0.540, 0.684) P = 0.81, Fig. 3B, AQUA: effect per variant allele = 379.88 (95% CI: −58.10, 817.9) P = 0.094, Fig. 3C]. None of the other ESR1 SNPs were significantly associated with ESR1 gene transcript expression (all P > 0.01).

Table 2.

Associations between ESR1 and PGR SNPs and gene expression of ESR1 and PGR by RT-PCR

| Mean ESR1 or PGR Reference-normalized Gene Expression by Genotype (SD, n) |

Results from Additive Genetic Model |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | rsID | Homozygous Wild Type | Heterozygous | Homozygous Variant | Effect per Variant Allele (SE) | 95% CI (low) | 95% CI (high) | P Value |

| ESR1 | rs750686 | 9.78 (1.42, 31) | 10.22 (1.20, 50) | 9.56 (1.20, 12) | 0.034 (0.208) | −0.373 | 0.442 | 0.87 |

| rs1062577 | 9.97 (1.36, 78) | 10.02 (1.02, 9) | NA (NA, 0) | 0.054 (0.468) | −0.863 | 0.971 | 0.91 | |

| rs1884049 | 9.89 (1.35, 60) | 10.23 (1.20, 24) | 9.59 (1.32, 3) | 0.148 (0.259) | −0.360 | 0.656 | 0.57 | |

| rs2077647 | 10.00 (1.25, 22) | 9.89 (1.38, 52) | 10.19 (1.11, 18) | −0.083 (0.206) | −0.487 | 0.321 | 0.69 | |

| rs2228480 | 9.84 (1.30, 45) | 10.18 (1.35, 40) | 9.83 (0.744, 6) | 0.167 (0.221) | −0.266 | 0.600 | 0.45 | |

| rs2234693 | 10.22 (1.37, 20) | 9.94 (1.31, 54) | 9.88 (1.19, 19) | −0.169 (0.207) | −0.575 | 0.237 | 0.42 | |

| rs2347869 | 9.86 (1.26, 32) | 10.22 (1.31, 46) | 9.60 (1.22, 14) | −0.029 (0.199) | −0.419 | 0.361 | 0.89 | |

| rs2813543 | 10.11 (1.23, 61) | 9.67 (1.39, 26) | 10.74 (1.50, 3) | −0.159 (0.252) | −0.653 | 0.335 | 0.53 | |

| rs2982734 | 9.74 (1.41, 29) | 10.21 (1.21, 50) | 9.59 (1.26, 11) | 0.076 (0.215) | −0.345 | 0.498 | 0.72 | |

| rs3003917 | 9.93 (1.33, 50) | 10.08 (1.26, 28) | 10.35 (1.31, 6) | 0.184 (0.226) | −0.259 | 0.627 | 0.42 | |

| rs3020371 | 9.71 (1.52, 26) | 10.18 (1.19, 50) | 9.49 (1.31, 10) | 0.055 (0.232) | −0.400 | 0.510 | 0.81 | |

| rs3020376 | 9.81 (1.40, 49) | 10.39 (1.01, 26) | 9.77 (0.933, 10) | 0.156 (0.197) | −0.230 | 0.542 | 0.43 | |

| rs3020377 | 9.92 (1.34, 33) | 10.04 (1.28, 43) | 9.96 (1.35, 13) | 0.039 (0.203) | −0.359 | 0.437 | 0.85 | |

| rs3020410 | 9.81 (1.37, 64) | 10.46 (1.10, 22) | 10.77 (NA, 1) | 0.618 (0.294) | 0.042 | 1.194 | 0.039 | |

| rs3798577 | 10.17 (1.07, 20) | 9.85 (1.41, 52) | 10.16 (1.22, 18) | −0.010 (0.212) | −0.426 | 0.406 | 0.96 | |

| rs4870056 | 10.11 (1.31, 19) | 9.96 (1.30, 50) | 10.11 (1.34, 16) | −0.005 (0.220) | −0.437 | 0.426 | 0.98 | |

| rs4870061 | 9.74 (1.34, 54) | 10.16 (1.22, 26) | 10.77 (1.23, 8) | 0.478 (0.209) | 0.068 | 0.888 | 0.025 | |

| rs6930355 | 10.06 (1.29, 67) | 9.97 (1.19, 24) | 6.86 (NA, 1) | −0.336 (0.284) | −0.893 | 0.221 | 0.24 | |

| rs9322331 | 9.87 (1.32, 39) | 10.18 (1.25, 43) | 9.74 (1.40, 10) | 0.065 (0.206) | −0.339 | 0.469 | 0.75 | |

| rs9322335 | 9.84 (1.17, 51) | 10.18 (1.40, 34) | 10.33 (1.58, 7) | 0.288 (0.211) | −0.126 | 0.702 | 0.18 | |

| rs9322336 | 9.72 (1.27, 57) | 10.38 (1.24, 25) | 10.96 (1.57, 5) | 0.640 (0.228) | 0.193 | 1.087 | 0.0061 | |

| rs9340799 | 9.89 (1.33, 36) | 10.09 (1.23, 47) | 9.84 (1.51, 10) | 0.047 (0.209) | −0.363 | 0.457 | 0.82 | |

| rs9340835 | 10.27 (1.35, 40) | 9.66 (1.34, 37) | 9.70 (0.582, 9) | −0.404 (0.210) | −0.816 | 0.008 | 0.06 | |

| rs9340958 | 9.97 (1.36, 75) | 10.07 (1.00, 18) | NA (NA, 0) | 0.100 (0.341) | −0.569 | 0.768 | 0.77 | |

| rs9341004 | 10.10 (1.20, 75) | 9.73 (1.48, 15) | NA (NA, 0) | −0.376 (0.354) | −1.070 | 0.318 | 0.29 | |

| rs9341066 | 9.92 (1.28, 80) | 10.43 (1.33, 13) | NA (NA, 0) | 0.510 (0.385) | −0.245 | 1.265 | 0.19 | |

| rs9479188 | 10.02 (1.29, 65) | 9.94 (1.22, 22) | 8.28 (2.01, 2) | −0.324 (0.273) | −0.859 | 0.211 | 0.24 | |

| PGR | rs500760 | 7.45 (1.84, 46) | 8.09 (1.58, 26) | 8.33 (0.461, 6) | 0.521 (0.301) | −0.069 | 1.111 | 0.09 |

| rs506487 | 7.96 (1.79, 39) | 7.72 (1.38, 37) | 6.29 (2.17, 6) | −0.557 (0.294) | −1.133 | 0.019 | 0.06 | |

| rs516693 | 7.54 (1.62, 59) | 8.21 (1.82, 22) | 8.83 (NA, 1) | 0.670 (0.381) | −0.077 | 1.417 | 0.08 | |

| rs518162 | 7.97 (1.55, 65) | 6.88 (2.13, 10) | 4.94 (1.74, 2) | −1.285 (0.413) | −2.094 | −0.476 | 0.0026 | |

| rs660149 | 7.85 (1.62, 36) | 7.55 (1.74, 39) | 7.85 (1.80, 6) | −0.139 (0.303) | −0.733 | 0.455 | 0.65 | |

| rs1042838 | 7.64 (1.83, 64) | 8.06 (0.935, 18) | 8.32 (NA, 1) | 0.400 (0.404) | −0.392 | 1.192 | 0.33 | |

| rs11571171 | 7.71 (1.70, 32) | 7.46 (1.60, 33) | 8.88 (1.03, 15) | 0.453 (0.243) | −0.023 | 0.929 | 0.07 | |

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; CI, confidence interval, NA, not applicable. Boldface font indicates statistically significant association (P < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

Association between the ESR1 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs9322336 and ESR1 gene and ERα protein expression. There was a statistically significant association between rs9322336 in the ESR1 gene and normalized ESR1 gene expression (A); however, this SNP was not associated with ERα protein expression measured by IHC (B) or automated quantitative immunofluorescence assay (AQUA, C).

Associations between PGR SNPs and gene transcript expression.

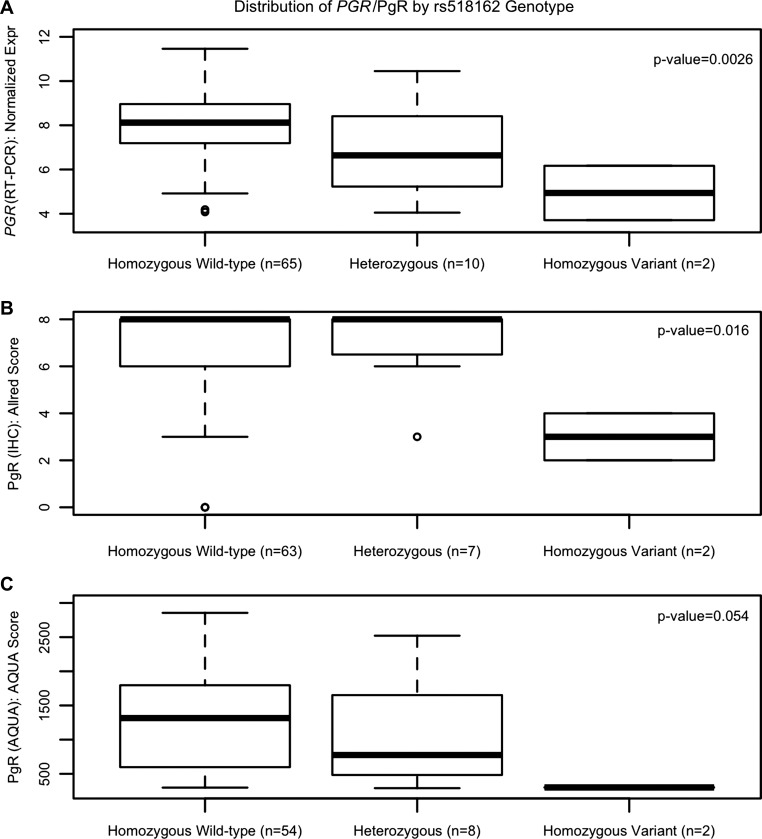

Germline genotypes for seven PGR SNPs were evaluated for association with tumor gene transcript expression of PGR. There was a statistically significant association between the PGR SNP rs518162 and expression of PGR. Each variant allele a patient carried decreased the relative PGR expression by 1.285 (95% CI: −2.094, −0.476, P = 0.0026, Fig. 4A). This SNP was then assessed for an association with PgR protein expression. A significant association was detected for PgR expression measured by IHC [effect per variant allele = −1.21 (95% CI: −2.166, −0.254), P = 0.016, Fig. 4B], but not by AQUA [effect per variant allele = −369.8 (95% CI: −739.5, −0.144), P = 0.054, Fig. 4C]. None of the other SNPs were significantly associated with PGR gene transcript expression (all P > 0.01).

Fig. 4.

Association between the PGR SNP rs518162 and PGR gene and PgR protein expression. There was a statistically significant association between rs518162 in the PGR gene and normalized PGR gene expression (A) and PgR protein expression measured by IHC (B) but not AQUA (C).

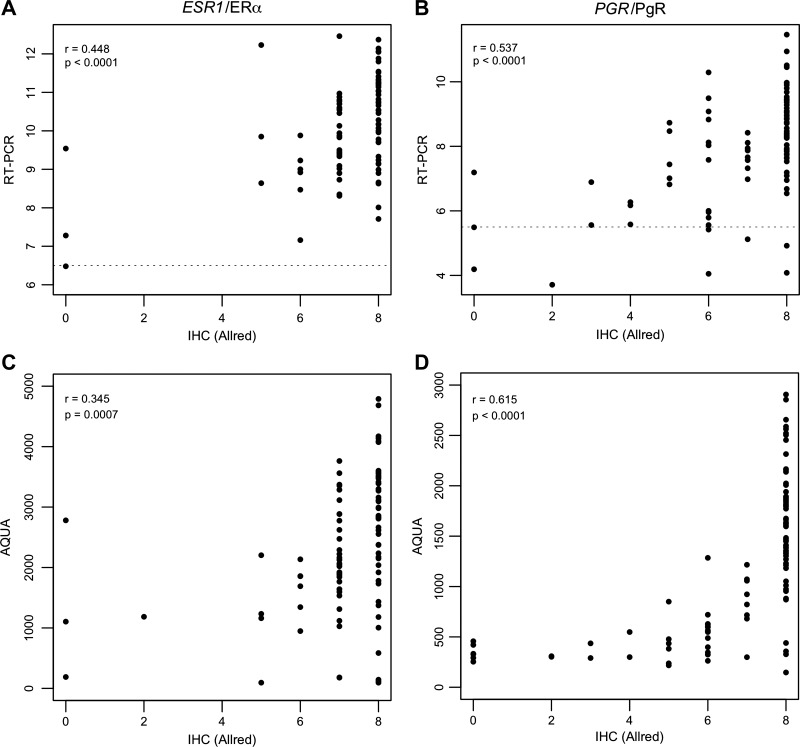

Correlations between gene and protein expression for ER and PgR.

A correlation matrix between the gene and protein expression levels for both genes can be found in Table 3. There was a modest, but highly statistically significant, correlation between gene and protein expression measured by IHC for ESR1/ERα (Pearson correlation r = 0.448, P < 0.0001, Fig. 5A) and a slightly stronger correlation for PGR/PgR (r = 0.537, P < 0.0001, Fig. 5B). The correlations between gene expression and protein expression measured by AQUA were slightly less strong for ESR1/ERα (r = 0.316, P = 0.005) but slightly stronger for PGR/PgR (r = 0.639, P < 0.0001). Finally, there was a modest correlation between the protein expression measured by IHC and AQUA for ERα (r = 0.345, P = 0.0007, Fig. 5C) and, again, somewhat stronger correlation for PgR (r = 0.615, P < 0.0001, Fig. 5D).

Table 3.

Correlation matrix of ESR1/PGR gene expression (RT-PCR) and ERα/PgR protein expression (IHC and AQUA)

| Expression Quantitation Method | RT-PCR (gene) | IHC (protein) |

|---|---|---|

| IHC (protein) | ESR1/ERα | |

| n = 86 | ||

| r = 0.448 | ||

| P < 0.0001 | ||

| PGR/PgR | ||

| n = 88 | ||

| r = 0.537 | ||

| P < 0.0001 | ||

| AQUA (protein) | ESR1/ERα | ERα |

| n = 79 | n = 93 | |

| r = 0.316 | r = 0.345 | |

| P = 0.0045 | P = 0.0007 | |

| PGR/PgR | PgR | |

| n = 78 | n = 99 | |

| r = 0.639 | r = 0.615 | |

| P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 |

RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; IHC, immunohistochemistry; AQUA, automated quantitative immunofluorescence assay.

Fig. 5.

Correlation of gene and protein expression. Moderate, but statistically significant, correlations were found for ESR1/ERα and PGR/PgR gene expression measured by RT-PCR and protein expression measured by IHC (A and B) and for protein expression measured by IHC and AQUA (C and D). p = P value, r = Pearson correlation coefficient. The dotted lines in A and B signify the cut-offs for ER and PgR positivity of the RT-PCR assay.

DISCUSSION

Understanding the variability in tamoxifen efficacy could lead to better treatment decision-making, especially regarding the selection of tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors for women with HR+ breast cancer. Recently, it was reported that germline polymorphisms in ESR1 are associated with reduced distant recurrence during tamoxifen and/or letrozole treatment (27) and may predict tumor responsiveness to tamoxifen (32). We hypothesized that these associations may be mediated by altered expression of ESR1/ERα and PGR/PgR in patients carrying these SNPs. In this cohort of women with HR+ breast cancer, we detected associations for a variant allele in ESR1 (rs9322336) and increased ESR1 gene transcript expression and an association for the variant rs518162 allele of PGR and decreased gene transcript and protein expression of PGR/PgR.

We previously reported that the variant rs9322336 allele, which was associated with increased tumor ESR1 expression in this analysis, was associated with a greater likelihood of discontinuing adjuvant endocrine treatment with exemestane for early-stage breast cancer due to treatment-related musculoskeletal toxicity (20). This polymorphism has also been reported as a predictor of migraines in a large meta-analysis of Europeans (28). To our knowledge this intronic variant has not been previously investigated for associations with breast tumor features or hormonal treatment efficacy. Finally, in The Cancer Genome Atlas analysis of breast tumors (5) this SNP was reported to be an expression quantitative trait loci of the tumor mRNA transcript HS.339700 (probeID ILMN_1873953) (P = 0.0055); however, the biological implications of this are unknown.

The PGR SNP rs518162 is located in the 5′-untranslated region, in a site that binds several breast cancer-relevant transcription factors including GATA3 and FOXA1 (49). Tumors from patients who carried the variant allele had lower expression of the PGR gene and PgR protein, as measured by IHC. Based on the correlations between PgR protein expression measured by IHC and AQUA, and the nearly statistically significant results, it is possible that this SNP would be associated with protein expression by AQUA if more samples were analyzed in an independent validation cohort. Prior studies have investigated the association between rs518162 and predisposition to multiple cancers, including the hormonally driven breast (18, 24) and endometrial (44) cancers, but no associations have been reported to our knowledge. Again, we are not aware of any reports that investigate whether this SNP is associated with breast tumors and/or their response to treatment. In fact, few studies have investigated associations between germline variants and somatic tumor characteristics. A prior study by Anghel et al. (1) reported that the ESR1 rs3798577 variant allele was more common in patients whose tumors expressed PgR by IHC but was not associated with ER status. We did not detect an association between this SNP and ERα expression, which is consistent with their findings. However, in an attempted secondary replication of their original report we did not detect a similar association between this variant and PgR transcript expression (P = 0.41).

Recently, Leyland-Jones et al. (27) performed a secondary pharmacogenetic analysis in the Breast International Group 1–98 Study, a large prospective clinical trial of tamoxifen and letrozole given alone or in sequence to postmenopausal patients with HR+ early breast cancer. They reported that each variant allele of ESR1 rs2077647 reduced distant recurrence during treatment (HR = 0.73, P < 0.001), with the effect seen in both the letrozole and tamoxifen monotherapy arms. We did not find any association between this SNP and ESR1 expression in this cohort (P = 0.69). Leyland-Jones et al. also reported that carriers of ESR1 rs9340799 (XbaI) had decreased risk of a breast cancer event (HR = 0.82, P = 0.05), and this effect may have been exclusive to the tamoxifen monotherapy group. This well-known variant has been intensely investigated for associations with the occurrence of hormone-relevant cancers (16, 42, 54) and other nononcologic diseases (7, 9, 31). Madeira et al. (32) also investigated the rs9340799 (XbaI) SNP, in addition to another well-known ESR1 polymorphism, rs2234693, referred to as PvuII (47, 51, 54), in relation to tamoxifen responsiveness. In a retrospective analysis of 44 tamoxifen treated patients, they found that all patients who were homozygous variant at both positions responded to tamoxifen, though this was a very small group and the association was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). In our cohort rs9340799 (XbaI) and rs2234693 (PvuII) were not associated with ESR1 expression (P = 0.82, 0.42).

A key strength of our study is assessment of ESR1/ERα and PGR/PgR expression via multiple methodologies, including both gene and protein expression. We found modest correlations between gene and protein expression (r = 0.448–0.537), which were similar to correlations reported by Du et al. (12) when comparing RT-QPCR to IHC status for ER (r = 0.527) and PgR (r = 0.631). Other groups have performed similar analyses and reported highly predictive thresholds for translating gene expression into clinical receptor status (3, 52). It is conceivable that automated, multiplexed gene expression assays will largely replace the cumbersome protein expression staining approaches that are currently standard of practice for clinical classification of breast tumors (46).

It is well known across genes and tissues that gene transcript expression is not always a meaningful predictor of protein expression (45), but it is particularly interesting that in this analysis the correlations between two protein quantification methodologies (IHC and AQUA) were not consistently stronger than gene-protein correlations. Stronger correlations between ERα status measured by IHC and AQUA have been reported (r = 0.8903) with substantial concordance when applying standard threshold of positivity (8). In another study the 10–20% of patients classified as ER+ by AQUA but ER− by IHC were found to have clinical outcomes similar to patients classified as ER+ by both methodologies, suggesting that AQUA may be more reflective of relevant tumor biology (50).

There are limitations of these analyses that should be considered. It is possible that other SNPs in ESR1 or PGR that were not included in our analysis could mediate tumor gene/protein expression. We interrogated several dozen candidate polymorphisms that captured the genetic variability in ESR1 and PGR based on a review of the literature. As more variants are discovered, and more powerful tools are available to predict functional consequence of genetic variation, our ability to make informed selection of candidate SNPs will improve. Also, given the relatively large number of variants evaluated and our limited cohort size we may have been unable to detect associations with smaller effects due to limited statistical power. It is also likely that the tumor's somatic genetic alterations contribute to the variability in estrogen and progesterone receptor expression found in tumors, particularly given recent confirmation of the existence of activating somatic ESR1 mutations (40, 43). Another potential limitation of this study is that the TMA spots used to measure protein expression may not represent the HR expression in all sections of the tumor, due to intratumor heterogeneity of HR expression (8). The two samples included in the TMA and those submitted for analysis with the 21 gene Recurrence Score assay were from the same tumor block but were not necessarily from the same region within the tumor specimen.

In conclusion, we discovered a SNP in ESR1 that is associated with increased ESR1 gene transcript expression and a SNP in PGR associated with decreased expression of the PGR gene transcript and possibly the PgR protein in HR+ breast tumors. However, these associations did not pass strict Bonferroni adjustment and therefore require validation in independent sample cohorts. We also confirmed moderate concordance between gene transcript and protein expression levels, and protein expression levels measured by two different assays. These findings support continued efforts to develop more accurate tumor classification systems using combinations of genomic approaches to inform selection of the ideal hormonal treatment in patients with HR+ breast cancer.

GRANTS

This work was supported by an American Society of Clinical Oncology Young Investigator Award (N. L. Henry); a Cancer Center Biostatistics Training Grant (5T32CA-083654-12, PI Jeremy Taylor, K. M. Kidwell); a Pharmacogenetics Research Network Grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (U-01 GM-61373, D. A. Flockhart); the Fashion Footwear Charitable Foundation/QVC Presents Shoes on Sale (D. F. Hayes); and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (J. M. Rae). This research was made possible by NIH Grant M01-RR-000042 (University of Michigan) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the NIH. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or NIH. Genomic Health, Inc. incurred the costs of performing the 21 gene Recurrence Score assay.

DISCLOSURES

N.L.H. receives research funding from Medivation and Celldex Therapeutics. A.G. is an employee of Genomic Health, Inc. T.C.S. has received speaking honoraria for Roche Diagnostics. V.S. has served as a consultant to Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Concert Pharmaceuticals and JDS Pharmaceuticals, and has received research funding from Pfizer and Novartis, and received honoraria from Astra Zeneca. D.F.H. has received research funding from AstraZeneca, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Pfizer, and Novartis. J.M.R. has received research funding from Pfizer. D.L.H., D.T., M.B., J.N.T., F.A., L.L., and C.G.K. have no disclosures to report.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.L.H., N.L.H., A.G., J.N.T., C.G.K., V.S., D.F.H., T.C.S., and J.M.R. interpreted results of experiments; D.L.H., N.L.H., K.M.K., K.S., J.N.T., V.S., and T.C.S. edited and revised manuscript; D.L.H., N.L.H., K.M.K., D.T., A.G., K.S., D.F.H., T.C.S., and J.M.R. approved final version of manuscript; N.L.H. drafted manuscript; K.M.K., D.T., F.A., K.S., L.L., and M.B. analyzed data; K.M.K. and K.S. prepared figures; D.T., A.G., and C.G.K. performed experiments; D.F.H., T.C.S., and J.M.R. conception and design of research.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the long-term support and expertise of the late Dr. David A. Flockhart, who was a founder and integral member of COBRA. We acknowledge Steven Shak, Claire Pomeroy, Kevin Chew, and David Rimm, for help and assistance on this project.

The results of this study were presented in part in a poster session at the 2008 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, San Antonio, TX, December 11–14, 2008.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anghel A, Raica M, Narita D, Seclaman E, Nicola T, Ursoniu S, Anghel M, Popovici E. Estrogen receptor alpha polymorphisms: correlation with clinicopathological parameters in breast cancer. Neoplasma 57: 306–315, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoniou AC, Kartsonaki C, Sinilnikova OM, Soucy P, McGuffog L, Healey S, Lee A, Peterlongo P, Manoukian S, Peissel B, Zaffaroni D, Cattaneo E, Barile M, Pensotti V, Pasini B, Dolcetti R, Giannini G, Putignano AL, Varesco L, Radice P, Mai PL, Greene MH, Andrulis IL, Glendon G, Ozcelik H, Thomassen M, Gerdes AM, Kruse TA, Birk Jensen U, Cruger DG, Caligo MA, Laitman Y, Milgrom R, Kaufman B, Paluch-Shimon S, Friedman E, Loman N, Harbst K, Lindblom A, Arver B, Ehrencrona H, Melin B, SWE-BRCA, Nathanson KL, Domchek SM, Rebbeck T, Jakubowska A, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, Huzarski T, Byrski T, Cybulski C, Gorski B, Osorio A, Ramon y Cajal T, Fostira F, Andres R, Benitez J, Hamann U, Hogervorst FB, Rookus MA, Hooning MJ, Nelen MR, van der Luijt RB, van Os TA, van Asperen CJ, Devilee P, Meijers-Heijboer HE, Gomez Garcia EB, HEBON, Peock S, Cook M, Frost D, Platte R, Leyland J, Evans DG, Lalloo F, Eeles R, Izatt L, Adlard J, Davidson R, Eccles D, Ong KR, Cook J, Douglas F, Paterson J, Kennedy MJ, Miedzybrodzka Z, EMBRACE, Godwin A, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Buecher B, Belotti M, Tirapo C, Mazoyer S, Barjhoux L, Lasset C, Leroux D, Faivre L, Bronner M, Prieur F, Nogues C, Rouleau E, Pujol P, Coupier I, Frenay M, CEMO Study Collaborators, Hopper JL, Daly MB, Terry MB, John EM, Buys SS, Yassin Y, Miron A, Goldgar D, Breast Cancer Family Registry, Singer CF, Tea MK, Pfeiler G, Dressler AC, Hansen T, Jonson L, Ejlertsen B, Barkardottir RB, Kirchhoff T, Offit K, Piedmonte M, Rodriguez G, Small L, Boggess J, Blank S, Basil J, Azodi M, Toland AE, Montagna M, Tognazzo S, Agata S, Imyanitov E, Janavicius R, Lazaro C, Blanco I, Pharoah PD, Sucheston L, Karlan BY, Walsh CS, Olah E, Bozsik A, Teo SH, Seldon JL, Beattie MS, van Rensburg EJ, Sluiter MD, Diez O, Schmutzler RK, Wappenschmidt B, Engel C, Meindl A, Ruehl I, Varon-Mateeva R, Kast K, Deissler H, Niederacher D, Arnold N, Gadzicki D, Schonbuchner I, Caldes T, de la Hoya M, Nevanlinna H, Aittomaki K, Dumont M, Chiquette J, Tischkowitz M, Chen X, Beesley J, Spurdle AB, kConFab investigators, Neuhausen SL, Chun Ding Y, Fredericksen Z, Wang X, Pankratz VS, Couch F, Simard J, Easton DF, Chenevix-Trench G, CIMBA . Common alleles at 6q251 and 1p112 are associated with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Hum Mol Genet 20: 3304–3321, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastien RR, Rodríguez-Lescure Á, Ebbert MT, Prat A, Munárriz B, Rowe L, Miller P, Ruiz-Borrego M, Anderson D, Lyons B, Álvarez I, Dowell T, Wall D, Seguí MÁ, Barley L, Boucher KM, Alba E, Pappas L, Davis CA, Aranda I, Fauron C, Stijleman IJ, Palacios J, Antón A, Carrasco E, Caballero R, Ellis MJ, Nielsen TO, Perou CM, Astill M, Bernard PS, Martin M. PAM50 breast cancer subtyping by RT-qPCR and concordance with standard clinical molecular markers. BMC Med Genomics 5: 44, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berchuck A, Schildkraut JM, Wenham RM, Calingaert B, Ali S, Henriott A, Halabi S, Rodriguez GC, Gertig D, Purdie DM, Kelemen L, Spurdle AB, Marks J, Chenevix-Trench G. Progesterone receptor promoter +331A polymorphism is associated with a reduced risk of endometrioid and clear cell ovarian cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13: 2141–2147, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490: 61–70, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhary S, Panda AK, Mishra DR, Mishra SK. Association of +331G/A PgR polymorphism with susceptibility to female reproductive cancer: evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS One 8: e53308, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S, Zhao L, Roffey DM, Phan P, Wai EK. Association between the ESR1 -351A>G single nucleotide polymorphism (rs9340799) and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J 23: 2586–2593, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung GG, Zerkowski MP, Ghosh S, Camp RL, Rimm DL. Quantitative analysis of estrogen receptor heterogeneity in breast cancer. Lab Invest 87: 662–669, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Gregori M, Diatchenko L, Ingelmo PM, Napolioni V, Klepstad P, Belfer I, Molinaro V, Garbin G, Ranzani GN, Alberio G, Normanno M, Lovisari F, Somaini M, Govoni S, Mura E, Bugada D, Niebel T, Zorzetto M, De Gregori S, Molinaro M, Fanelli G, Allegri M. Human genetic variability contributes to postoperative morphine consumption. J Pain 17: 628–636, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng HW, Li J, Li JL, Johnson M, Gong G, Davis KM, Recker RR. Change of bone mass in postmenopausal Caucasian women with and without hormone replacement therapy is associated with vitamin D receptor and estrogen receptor genotypes. Hum Genet 103: 576–585, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolled-Filhart M, Ryden L, Cregger M, Jirstrom K, Harigopal M, Camp RL, Rimm DL. Classification of breast cancer using genetic algorithms and tissue microarrays. Clin Cancer Res 12: 6459–6468, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du X, Li XQ, Li L, Xu YY, Feng YM. The detection of ESR1/PGR/ERBB2 mRNA levels by RT-QPCR: a better approach for subtyping breast cancer and predicting prognosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 138: 59–67, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 378: 771–784, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emre A, Sahin S, Erzik C, Nurkalem Z, Oz D, Cirakoglu B, Yesilcimen K, Ersek B. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on plasma lipoproteins and apolipoproteins, endothelial function and myocardial perfusion in postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor-alpha IVS1-397 C/C genotype and established coronary artery disease. Cardiology 106: 44–50, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fejerman L, Ahmadiyeh N, Hu D, Huntsman S, Beckman KB, Caswell JL, Tsung K, John EM, Torres-Mejia G, Carvajal-Carmona L, Echeverry MM, Tuazon AM, Ramirez C, Consortium COLUMBUS, Gignoux CR, Eng C, Gonzalez-Burchard E, Henderson B, Le Marchand L, Kooperberg C, Hou L, Agalliu I, Kraft P, Lindstrom S, Perez-Stable EJ, Haiman CA, Ziv E. Genome-wide association study of breast cancer in Latinas identifies novel protective variants on 6q25. Nat Commun 5: 5260, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu C, Dong WQ, Wang A, Qiu G. The influence of ESR1 rs9340799 and ESR2 rs1256049 polymorphisms on prostate cancer risk. Tumour Biol 35: 8319–8328, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goetz MP, Suman VJ, Hoskin TL, Gnant M, Filipits M, Safgren SL, Kuffel M, Jakesz R, Rudas M, Greil R, Dietze O, Lang A, Offner F, Reynolds CA, Weinshilboum RM, Ames MM, Ingle JN. CYP2D6 metabolism and patient outcome in the Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group trial (ABCSG) 8. Clin Cancer Res 19: 500–507, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold B, Kalush F, Bergeron J, Scott K, Mitra N, Wilson K, Ellis N, Huang H, Chen M, Lippert R, Halldorsson BV, Woodworth B, White T, Clark AG, Parl FF, Broder S, Dean M, Offit K. Estrogen receptor genotypes and haplotypes associated with breast cancer risk. Cancer Res 64: 8891–8900, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey JM, Clark GM, Osborne CK, Allred DC. Estrogen receptor status by immunohistochemistry is superior to the ligand-binding assay for predicting response to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 17: 1474–1481, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henry NL, Azzouz F, Desta Z, Li L, Nguyen AT, Lemler S, Hayden J, Tarpinian K, Yakim E, Flockhart DA, Stearns V, Hayes DF, Storniolo AM. Predictors of aromatase inhibitor discontinuation as a result of treatment-emergent symptoms in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 30: 936–942, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henry NL, Skaar TC, Dantzer J, Li L, Kidwell K, Gersch C, Nguyen AT, Rae JM, Desta Z, Oesterreich S, Philips S, Carpenter JS, Storniolo AM, Stearns V, Hayes DF, Flockhart DA. Genetic associations with toxicity-related discontinuation of aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 138: 807–816, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herrington DM, Howard TD, Hawkins GA, Reboussin DM, Xu J, Zheng SL, Brosnihan KB, Meyers DA, Bleecker ER. Estrogen-receptor polymorphisms and effects of estrogen replacement on high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in women with coronary disease. N Engl J Med 346: 967–974, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin Y, Hayes DF, Li L, Robarge JD, Skaar TC, Philips S, Nguyen A, Schott A, Hayden J, Lemler S, Storniolo AM, Flockhart DA, Stearns V. Estrogen receptor genotypes influence hot flash prevalence and composite score before and after tamoxifen therapy. J Clin Oncol 26: 5849–5854, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnatty SE, Spurdle AB, Beesley J, Chen X, Hopper JL, Duffy DL, Chenevix-Trench G, Kathleen Cuningham Consortium for Research in Familial Breast Cancer. Progesterone receptor polymorphisms and risk of breast cancer: results from two Australian breast cancer studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat 109: 91–99, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston SR. Enhancing endocrine therapy for hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer: cotargeting signaling pathways. J Natl Cancer Inst 107: djv212, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leyland-Jones B, Regan MM, Bouzyk M, Kammler R, Tang W, Pagani O, Maibach R, Dell'Orto P, Thurlimann B, Price KN, Viale G. Outcome according to CYP2D6 genotype among postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early invasive breast cancer randomized in the BIG 1–98 Trial. San Antonio, TX: 33rd Annual CTRC-AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, December 8–12, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leyland-Jones B, Gray KP, Abramovitz M, Bouzyk M, Young B, Long B, Kammler R, Dell'Orto P, Biasi MO, Thurlimann B, Harvey V, Neven P, Arnould L, Maibach R, Price KN, Coates AS, Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Pagani O, Viale G, Rae JM, Regan MM, BIG 1–98 Collaborative Group. ESR1 and ESR2 polymorphisms in the BIG 1–98 trial comparing adjuvant letrozole versus tamoxifen or their sequence for early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 154: 543–555, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ligthart L, de Vries B, Smith AV, Ikram MA, Amin N, Hottenga J, Koelewijn SC, Kattenberg VM, de Moor MH, Janssens AC, Aulchenko YS, Oostra BA, de Geus EJ, Smit JH, Zitman FG, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, Willemsen G, Nyholt DR, Montgomery GW, Terwindt GM, Gudnason V, Penninx BW, Breteler M, Ferrari MD, Launer LJ, van Duijn C, M, van den Maagdenberg AM, Boomsma DI. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association for migraine in six population-based European cohorts. Eur J Hum Genet 19: 901–907, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindstrom S, Thompson DJ, Paterson AD, Li J, Gierach GL, Scott C, Stone J, Douglas JA, dos-Santos-Silva I, Fernandez-Navarro P, Verghase J, Smith P, Brown J, Luben R, Wareham NJ, Loos RJ, Heit JA, Pankratz VS, Norman A, Goode EL, Cunningham JM, deAndrade M, Vierkant RA, Czene K, Fasching PA, Baglietto L, Southey MC, Giles GG, Shah KP, Chan HP, Helvie MA, Beck AH, Knoblauch NW, Hazra A, Hunter DJ, Kraft P, Pollan M, Figueroa JD, Couch FJ, Hopper JL, Hall P, Easton DF, Boyd NF, Vachon CM, Tamimi RM. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple loci associated with both mammographic density and breast cancer risk. Nat Commun 5: 5303, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu T, Chen L, Sun X, Wang Y, Li S, Yin X, Wang X, Ding C, Li H, Di W. Progesterone receptor PROGINS and +331G/A polymorphisms confer susceptibility to ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis based on 17 studies. Tumour Biol 35: 2427–2436, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma H, Wu W, Yang X, Liu J, Gong Y. Genetic effects of common polymorphisms in estrogen receptor alpha gene on osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med 8: 13446–13454, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madeira KP, Daltoe RD, Sirtoli GM, Carvalho AA, Rangel LB, Silva IV. Estrogen receptor alpha (ERS1) SNPs c454-397T>C (PvuII) and c454-351A>G (XbaI) are risk biomarkers for breast cancer development. Mol Biol Rep 41: 5459–5466, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohammed H, Russell IA, Stark R, Rueda OM, Hickey TE, Tarulli GA, Serandour AA, Birrell SN, Bruna A, Saadi A, Menon S, Hadfield J, Pugh M, Raj GV, Brown GD, D'Santos C, Robinson JL, Silva G, Launchbury R, Perou CM, Stingl J, Caldas C, Tilley WD, Carroll JS. Progesterone receptor modulates ERalpha action in breast cancer. Nature 523: 313–317, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nocito A, Kononen J, Kallioniemi OP, Sauter G. Tissue microarrays (TMAs) for high-throughput molecular pathology research. Int J Cancer 94: 1–5, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oesterreich S, Henry NL, Kidwell KM, Van Poznak CH, Skaar TC, Dantzer J, Li L, Hangartner TN, Peacock M, Nguyen AT, Rae JM, Desta Z, Philips S, Storniolo AM, Stearns V, Hayes DF, Flockhart DA. Associations between genetic variants and the effect of letrozole and exemestane on bone mass and bone turnover. Breast Cancer Res Treat 154: 263–273, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Onitilo AA, McCarty CA, Wilke RA, Glurich I, Engel JM, Flockhart DA, Nguyen A, Li L, Mi D, Skaar TC, Jin Y. Estrogen receptor genotype is associated with risk of venous thromboembolism during tamoxifen therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 115: 643–650, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osborne CK. Tamoxifen in the treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 339: 1609–1618, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paik S, Tang G, Shak S, Kim C, Baker J, Kim W, Cronin M, Baehner FL, Watson D, Bryant J, Costantino JP, Geyer CE Jr Wickerham DL, Wolmark N. Gene expression and benefit of chemotherapy in women with node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 24: 3726–3734, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rae JM, Drury S, Hayes DF, Stearns V, Thibert JN, Haynes BP, Salter J, Pineda S, Cuzick J, Doswsett M. Lack of correlation between gene variants in tamoxifen metabolizing enzymes with primary endpoints in the ATAC trial. San Antonio, TX: 33rd Annual CTRC-AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, December 8–12, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson DR, Wu YM, Vats P, Su F, Lonigro RJ, Cao X, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Wang R, Ning Y, Hodges L, Gursky A, Siddiqui J, Tomlins SA, Roychowdhury S, Pienta KJ, Kim SY, Roberts JS, Rae JM, Van Poznak CH, Hayes DF, Chugh R, Kunju LP, Talpaz M, Schott AF, Chinnaiyan AM. Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nat Genet 45: 1446–1451, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schroth W, Goetz MP, Hamann U, Fasching PA, Schmidt M, Winter S, Fritz P, Simon W, Suman VJ, Ames MM, Safgren SL, Kuffel MJ, Ulmer HU, Bolander J, Strick R, Beckmann MW, Koelbl H, Weinshilboum RM, Ingle JN, Eichelbaum M, Schwab M, Brauch H. Association between CYP2D6 polymorphisms and outcomes among women with early stage breast cancer treated with tamoxifen. JAMA 302: 1429–1436, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Srivastava A, Sharma KL, Srivastava N, Misra S, Mittal B. Significant role of estrogen and progesterone receptor sequence variants in gallbladder cancer predisposition: a multi-analytical strategy. PLoS One 7: e40162, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toy W, Shen Y, Won H, Green B, Sakr RA, Will M, Li Z, Gala K, Fanning S, King TA, Hudis C, Chen D, Taran T, Hortobagyi G, Greene G, Berger M, Baselga J, Chandarlapaty S. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nat Genet 45: 1439–1445, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Treloar SA, Zhao ZZ, Armitage T, Duffy DL, Wicks J, O'Connor DT, Martin NG, Montgomery GW. Association between polymorphisms in the progesterone receptor gene and endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod 11: 641–647, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vogel C, Marcotte EM. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat Rev Genet 13: 227–232, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallden B, Storhoff J, Nielsen T, Dowidar N, Schaper C, Ferree S, Liu S, Leung S, Geiss G, Snider J, Vickery T, Davies SR, Mardis ER, Gnant M, Sestak I, Ellis MJ, Perou CM, Bernard PS, Parker JS. Development and verification of the PAM50-based Prosigna breast cancer gene signature assay. BMC Med Genomics 8: 54, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang CL, Tang XY, Chen WQ, Su YX, Zhang CX, Chen YM. Association of estrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphisms with bone mineral density in Chinese women: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 18: 295–305, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J, Lu K, Song Y, Xie L, Zhao S, Wang Y, Sun W, Liu L, Zhao H, Tang D, Ma W, Pan B, Xuan Q, Liu H, Zhang Q. Indications of clinical and genetic predictors for aromatase inhibitors related musculoskeletal adverse events in Chinese Han women with breast cancer. PLoS One 8: e68798, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ward LD, Kellis M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res 40: D930–D934, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Welsh AW, Moeder CB, Kumar S, Gershkovich P, Alarid ET, Harigopal M, Haffty BG, Rimm DL. Standardization of estrogen receptor measurement in breast cancer suggests false-negative results are a function of threshold intensity rather than percentage of positive cells. J Clin Oncol 29: 2978–2984, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weng H, Zhang C, Hu YY, Yuan RX, Zuo HX, Yan JZ, Niu YM. Association between estrogen receptor-alpha gene XbaI and PvuII polymorphisms and periodontitis susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Dis Markers 2015: 741972, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson TR, Xiao Y, Spoerke JM, Fridlyand J, Koeppen H, Fuentes E, Huw LY, Abbas I, Gower A, Schleifman EB, Desai R, Fu L, Sumiyoshi T, O'Shaughnessy JA, Hampton GM, Lackner MR. Development of a robust RNA-based classifier to accurately determine ER, PR, and HER2 status in breast cancer clinical samples. Breast Cancer Res Treat 148: 315–325, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yin L, Wang ZY. Roles of the ER-α36-EGFR/HER2 positive regulatory loops in tamoxifen resistance. Steroids 111: 95–99, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y, Zhang M, Yuan X, Zhang Z, Zhang P, Chao H, Jiang L, Jiang J. Association between ESR1 PvuII, XbaI, and P325P polymorphisms and breast cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Med Sci Monit 21: 2986–2996, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.