Abstract

Background

Prevalence of H.pylori infection varies greatly between populations in different countries. This study was conducted to determine the magnitude of H.pylori among adult patients with dyspepsia attending the gastroenterology unit at Bugando medical centre.

Methods

A cross sectional study involving 202 dyspeptic patients was conducted between June and July 2014. A Standardized data collection tool was used to collect socio-demographic characteristics. H.pylori antibodies were detected using rapid immunochromatographic tests according to manufacturer's instructions.

Results

The median age of study population was 42 (IQR: 33–54). Females 105 (51.9%) formed majority of the population studied. Of 202 participants; 119 (58.9%) were from rural areas. Seroprevalence of H.pylori infection was found to be 79/202 (39.1%, 95% CI: 32.3–45.7). As the age increased the risk of having H.pylori infection also increased (OR: 1.02 95% CI: 1–1.04, P=0.02). On multivariate logistic regression analysis untreated drinking water was found to predict H.pylori seropositivity (OR: 2.33, CI: 1.09–4.96, p=0.028).

Conclusion

The seroprevalence of H.pylori among dyspeptic patients is high in this setting. Therefore the community in Mwanza should be educated on the use of safe drinking water in order to minimize H. pylori infections.

Keywords: H.pylori, dyspepsia, Tanzania

Background

Helicobacter pylori is one of the major public health problems worldwide. More than half of the world's population is infected and humans are considered to be the only reservoirs1. H.pylori infections can lead to gastritis, peptic ulcer, gastric carcinoma and mucosal associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma2. Majority of the infected individuals are asymptomatic; nevertheless a small percentage tends to develop manifestations of peptic ulcer diseases later in life1.

H.pylori is commonly transmitted by fecal oral route through contaminated water and food3. Lack of proper sanitation, basic hygiene, poor diets and overcrowding have been found to play a significant role in H.pylori infection4. H.pylori infection is common throughout the world, the seroprevalence as high as >90% has been reported in many developing countries compared to 1.2–48.8% in developed countries5. In Africa the seroprevalence has been found to range between 19.26% and 92%6,7 while in Tanzania the prevalence range from 65%–79% among dyspeptic patients7,8. A wide variation in the seroprevalence of H.pylori infection within and between different populations has been observed. Despite these variations there is no single study in Mwanza to show the magnitude of previous H. pylori infections. This study was done for the first time in Mwanza, Tanzania to investigate the magnitude and factors associated with previous H.pylori infection.

Materials and methods

Study design and settings

This was a cross-sectional hospital based study conducted at gastroenterology unit at the Bugando Medical Centre (BMC) between June and July 2014 to investigate the magnitude of H.pylori infection. The study included all dyspeptic patients who consented to participate in the study. BMC is a tertiary, consultant and teaching hospital serving a population of about 13 million in the Lake zone of Tanzania.

Sample size and sampling

The sample size was determined by using Kish Leslie formula; a proportion of 22.5% was used9. The minimum sample size obtained was 188. Dyspeptic adult patients with no active bleeding were serially enrolled until the sample size was reached.

Data collection

A standardized structured data collection tool was used to collect associated factors such as demographic and general characteristics. Dyspepsia was defined as difficult, or disturbed digestion, which may be accompanied by symptoms such as epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, bloating and heartburn10. In this study illiterate and primary school level was defined as low education while secondary school and tertiary level were defined as high education. Treated drinking water was defined as water from the city supply or commercial available bottled water.

To determine H.pylori specific IgG antibodies about 4–5ml of blood sample was drawn from participants and placed in a plain vacutainer tubes (BD, UK). Specimens were taken to BMC laboratory where sera were extracted. H.pylori IgG antibodies were detected using rapid immunochromatographic kits (Flexsure-HP, SmithKline Diagnostics, Inc USA). The test has specificity and sensitivity of 95% and 96% respectively11.

Data analysis

Data was entered in the computer using excel software and analysed using STATA version 11(STATA Corp LP, USA). The main outcome in this study was being H.pylori IgG antibody positive. Categorical variables such as sex, residence, source of drinking water, education level, water treatment, and hand washing before eating were summarized as proportions while age was summarized as median with interquartile range (IQR). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis were done to determine factors predicting H.pylori infection. Factors with p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant at 95% confidence interval (CI).

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the joint CUHAS/BMC research ethics and review committee and permission was obtained from gastroenterology unit administration. Written informed consent was sought from each participant prior to enrolment in the study.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 202 patients were recruited at the gastroenterology unit with median age of 42(IQR: 33–54) years. Females 105(51.9%) formed majority of the study population. Of 202 participants; 119(59%) and 83(41%) were residing in rural and urban areas respectively. Regarding occupational status; 16(7.9%) were students, 46(22.7%) were employed and 140(69.3%) were unemployed.

Prevalence and factors associated with H.pylori infections

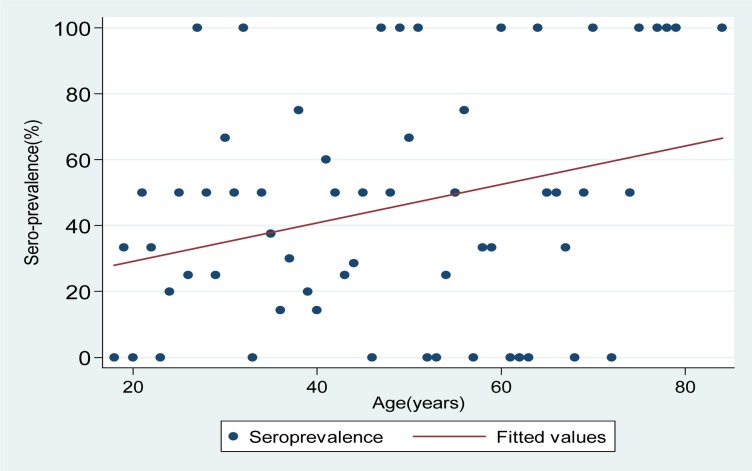

A total of 79(39.1%; 95% CI: 32.3–45.7) participants were sero-positive for H.pylori. As the age increased the risk of having H.pylori infection also increased (OR: 1.02 95% CI: 1–1.04, P=0.02) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

As the age increases the risk of having H.pylori infection also increases by 2% while the seroprevalence of H.pylori increases by 0.5%

On univariate logistic regression analysis; low education level was significantly associated with H.pylori seropositivity (49.5% vs. 28.7%; OR: 2.43, CI 1.36–4.35, P=0.003). Patients who used untreated drinking water had 2.33 times risk of getting H.pylori infection compared to those used treated water (58.7% vs.30%, P<0.001) table 1. Only water treatment was found to be an independent predictor of H.pylori seropositivity on multivariate logistic regression analysis (OR: 3.28, CI: 1.77–6.10, P=0.028). (Table 1)

Table 1.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with H.pylori infection among 202 adult patients

| Characteristics | Positive test (N, %) |

Univariate | Multivariate | ||

| OR(95% CI) | P value | OR(95% CI) | P value |

||

| Age(years) | 42(IQR:33–54) | 1.02(1–1.04) | 0.024 | 1.01(0.98–1.03) | 0.469 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male(97) | 36(37.11%) | 1 | |||

| Female (105) | 43(40.95%) | 1.17(0.66–2.07) | 0.577 | 1.31(0.69–2.44) | 0.410 |

| Occupation | |||||

| Students(16) | 4(25%) | 1 | |||

| Not employed(141) | 58(41.13%) | 2.09(0.64–6.82) | 0.219 | ||

| Employed(45) | 17(37.78%) | 1.82(0.51–6.56) | 0.359 | 1.93(0.92–4.02) | 0.08 |

| Education level | |||||

| High (101) | 29(28.7%) | 1 | |||

| Low (101) | 50(49.5%) | 2.43(1.36–4.35) | 0.003 | 1.32(0.64–2.67) | 0.448 |

|

Source of drinking water |

|||||

| Tape water(101) | 32(31.68%) | 1 | |||

| Other sources(101) | 47(46.53%) | 1.87(1.05–3.32) | 0.031 | 0.83(0.39–1.77) | 0.634 |

| Water treatment | |||||

| Yes(139) | 42(30.22%) | 1 | |||

| No(63) | 37(58.73%) | 3.28(1.77–6.10) | <0.001 | 2.33(1.09–4.96) | 0.028 |

|

Hand washing before eating |

|||||

| Yes(184) | 72(39.13%) | 1 | |||

| No(18) | 7(38.89%) | 1.02(0.37–2.7) | 0.984 | 1.11(0.37–3.30) | 0.854 |

| Residence | |||||

| Urban(83) | 27(32.5%) | 1 | |||

| Rural(119) | 52(43.70%) | 1.69(0.89–2.88) | 0.111 | 1.00(0.49–2.06) | 0.984 |

Discussion

Although many individuals with H. pylori gastric colonization are asymptomatic, often those who seek medical attention may present with dyspepsia. Prolonged infection may result in gastric ulcers formation. The current study indicates the true magnitude of H.pylori infection among dyspeptic patients in our settings. Based on the natural history of the disease the seropositive individuals in the present study have 10–20% life time risk of developing peptic ulcers12 with 1–2% of the infected subjects at risk of developing gastric cancer13. This study has found comparable prevalence of H.pylori infection among dyspeptic patients as previously reported in Africa7,8,14,15. As compared to other studies in Africa6,16 the observed prevalence in the current study is lower and this could be explained by geographical variation as documented previously17,18. Moreover; the sensitivity of the method used may explain such a difference.

However, this prevalence is higher as compared to previous reports from developed countries19–22. This could be explained by poor living conditions which favor H.pylori transmission in developing countries.

In this study the odds of having H.pylori infection increased as the age increased which coincides with what has been reported earlier14,15,23 and contrary to data from Uganda where the prevalence was found to decrease as the age increased24. This could be explained by different study populations whereby in Uganda study the population studied was patients with different levels of malignancies. As suggested earlier gastric changes such as malignancies may cause decline of H.pylori specific antibodies and is likely to occur in patients with advanced disease and age; which is not the case in our study25.

On univariate logistic regression analysis, the odds of having H.pylori infections were significantly higher in rural areas compared to urban areas. Similarly, the odds of having H.pylori infection were higher among people with low education level than those with higher education level. Our findings are inconsistent with the previous studies which reported higher prevalence rates in urban areas and those with good socioeconomic status26,27. In rural settings of Mwanza majority of population have low socioeconomic status whereby the main economic activities are small scale farming and fishing unlike in urban areas where majority of the urban population have high education level and good socioeconomic status.

In the present study, untreated drinking water was independently found to predict H.pylori infections. These findings are in agreement with what has been reported earlier3,4 whereby unsafe drinking water and poor hygiene were found to be associated with H.pylori infection. Moreover; low education level in almost half of these participants and majority being from rural areas may explain why they cannot afford to treat water despite the fact that it is unsafe to drink.

Study limitations

Due to limited resources, endoscopy was not done; this resulted in failure to diagnose active disease because urease/histopathological and breath tests were not done. In addition stool antigen tests and other differentials of dyspepsia were not established28.

Conclusion and recommendations

Drinking untreated water and increasing age have been found to be associated with H. pylori infection. More studies should focus on assessing incidence rates in relation to age. Improving drinking water in our setting will reduce H.pylori transmission and its associated complications such as gastritis, gastric ulcers and gastric malignancies. Moreover, community in Mwanza should be educated on the preventive measures as one of the efforts to control gastric diseases associated with H.pylori infection.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical support provided by Mr.Vitus Silago. We thank all staff in gastroenterology unit at Bugando Medical Centre. This study was supported by research grant from CUHAS to HJ

Conflict of interest

None declared

Authors' contributions

HJ, MMM, MM and SEM participated in the design of the work. HJ MFM and LW participated in the collection of specimens and clinical data. MMM, JS and LW performed serological tests. MMM, MM, JS and SEM analyzed and interpreted the data. MMM, MFM and SEM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MMM and SEM critically revised the final draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Logan R, Gummett P, Schaufelberger H, Greaves R, Mendelson G, Walker M, Thomas P, Baron J, Misiewicz J. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori with clarithromycin and omeprazole. Gut. 1994;35:323–326. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egan BJ, Holmes K, O'Connor HJ, O'Morain CA. Helicobacter pylori gastritis, the unifying concept for gastric diseases. Helicobacter. 2007;12:39–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cave DR. Transmission and epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori. The American journal of medicine. 1996;100:12S–18S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)80224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt R, Xiao S, Megraud F, Leon-Barua R, Bazzoli F, Van der Merwe S, Vaz Coelho L, Fock M, Fedail S, Cohen H. Helicobacter pylori in developing countries. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guideline. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20:299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hazell S. Helicobacter pylori. Springer; 1994. H. pylori in developing countries; pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asombang AW, Kelly P. Gastric cancer in Africa: what do we know about incidence and risk factors? Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2012;106:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arun V, Mchembe M. Endoscopic Findings And Prevalence Of Helicobacter Pylori In Dyspeptic Patients Referred For Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy In Dar-EeSalaam. PMJUMU | PIONEER MEDICAL JOURNAL UMUAHIA. 2012:2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mbulaiteye SM, Hisada M, El-Omar EM. Helicobacter pylori associated global gastric cancer burden. Frontiers in bioscience: a journal and virtual library. 2009;14:1490. doi: 10.2741/3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mujeere MP. Prevalence and factors associated with helicobacter pylori infection among children aged one month to twelve years in Mulago hospital. Makerere University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ford AC, Marwaha A, Lim A, Moayyedi P. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in individuals with dyspepsia. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2010;8:401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham DY, Evans DJ, Jr, Peacock J, Baker JT, Schrier WH. Comparison of rapid serological tests (FlexSure HP and QuickVue) with conventional ELISA for detection of Helicobacter pylori infection. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1996:91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusters JG, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2006;19:449–490. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00054-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Correa P, Piazuelo MB. Natural history of Helicobacter pylori infection. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2008;40:490–496. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mbulaiteye SM, Gold BD, Pfeiffer RM, Brubaker GR, Shao J, Biggar RJ, Hisada M. H. pylori-infection and antibody immune response in a rural Tanzanian population. Infect Agent Cancer. 2006:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanih N, Okeleye B, Ndip L, Clarke A, Naidoo N, Mkwetshana N, Green E, Ndip R. Helicobacter pylori prevalence in dyspeptic patients in the Eastern Cape province: race and disease status. SAMJ: South African Medical Journal. 2010;100:734–737. doi: 10.7196/samj.4041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baako B, Darko R. Incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Ghanaian patients with dyspeptic symptoms referred for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. West African Journal of Medicine. 1995;15:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez-Perez GI, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2004;9:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-4389.2004.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman RA, Eccersley AJP, Hardie JM. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori: acquisition, transmission, population prevalence and disease-to-infection ratio. British Medical Bulletin. 1998;54:39–53. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chong V, Lim K, Rajendran N. Prevalence of active Helicobacter pylori infection among patients referred for endoscopy in Brunei Darussalam. Singapore Medical Journal. 2008;49:42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahim AA, Lee YY, Majid NA, Choo KE, Raj SM, Derakhshan MH, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori infection among Aborigines (the Orang Asli) in the northeastern region of Peninsular Malaysia. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2010;83:1119–1122. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roosendaal R, Kuipers EJ, Buitenwerf J, Van Uffelen C, Meuwissen S, Van Kamp GJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C. Helicobacter pylori and the birth cohort effect: evidence of a continuous decrease of infection rates in childhood. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1997;92:1480–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loffeld R, Van Der Putten A. Changes in prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in two groups of patients undergoing endoscopy and living in the same region in the Netherlands. Changes. 2003;38:938–941. doi: 10.1080/00365520310004740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bureš J, Kopáčová M, Koupil I, Voříšek V, Rejchrt S, Beránek M, Seifert B, Pozler O, Živný P, Douda T. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in the Czech Republic. Helicobacter. 2006;11:56–65. doi: 10.1111/j.0083-8703.2006.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newton R, Ziegler JL, Casabonne D, Carpenter L, Gold BD, Owens M, Beral V, Mbidde E, Parkin DM, Wabinga H. Helicobacter pylori and cancer among adults in Uganda. Infect Agent Cancer. 2006:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forman D, Newell D, Fullerton F, Yarnell J, Stacey A, Wald N, Sitas F. Association between infection with Helicobacter pylori and risk of gastric cancer: evidence from a prospective investigation. British Medical Journal. 1991;6788:1302–1305. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6788.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawasaki M, Kawasaki T, Ogaki T, Kobayashi S, Yoshimizu Y, Aoyagi K, Takahashi S, Sharma S, Acharya GP. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Nepal: low prevalence in an isolated rural village. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 1998;10:47–50. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199801000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torres J, Leal-Herrera Y, Perez-Perez G, Gomez A, Camorlinga-Ponce M, Cedillo-Rivera R, Tapia-Conyer R, Mu±oz O. A community-based seroepidemiologic study of Helicobacter pylori infection in Mexico. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1998;178:1089–1094. doi: 10.1086/515663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Longstreth GF, Lacy BE, Talley NJ, Grover S. Approach to the adult with dyspepsia. UpToDate. 2013 [Google Scholar]