Abstract

Background. For Tis and T1a gallbladder cancer (GbC), laparoscopic cholecystectomy can provide similar survival outcomes compared to open cholecystectomy. However, for patients affected by resectable T1b or more advanced GbC, open approach radical cholecystectomy (RC), consisting in gallbladder liver bed resection or segment 4b-5 bisegmentectomy, with locoregional lymphadenectomy, is considered the gold standard while minimally invasive RC (MiRC) is skeptically considered. Aim. To analyze current literature on perioperative and oncologic outcomes of MiRC for patients affected by GbC. Methods. A Medline review of published articles until June 2016 concerning MiRC for GbC was performed. Results. Data relevant for this review were presented in 13 articles, including 152 patients undergoing an attempt of MiRC for GbC. No randomized clinical trial was found. The approach was laparoscopic in 147 patients and robotic in five. Conversion was required in 15 (10%) patients. Postoperative complications rate was 10% with no mortality. Long-term survival outcomes were reported by 11 studies, two of them showing similar oncologic results when comparing MiRC with matched open RC. Conclusions. Although randomized clinical trials are still lacking and only descriptive studies reporting on limited number of patients are available, current literature seems suggesting that when performed at highly specialized centers, MiRC for GbC is safe and feasible and has oncologic outcomes comparable to open RC.

1. Introduction

The role of laparoscopic surgery in the management of digestive tract tumor is increasingly accepted worldwide [1, 2]. However, although laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) began the era of laparoscopic surgery and is one of the most frequently performed mini-invasive procedures, the use of laparoscopic surgery is skeptically considered in the management of gallbladder cancer (GbC) [3]. GbC represents the most aggressive malignancy of the biliary tract and is characterized by an extremely poor prognosis. While increasing evidence shows that, for Tis and T1a GbC with clear margins and unbroken gallbladder, simple cholecystectomy, either laparoscopic or open, can be curative [4–7], for patients affected by resectable T1b or more advanced GbC, radical cholecystectomy (RC), consisting in liver resection (liver bed resection or segment 4b-5 bisegmentectomy) with locoregional lymphadenectomy, is the only available treatment to positively affect the prognosis [8–12].

Minimally invasive RC (MiRC) is skeptically considered by the majority of HPB surgeons, mainly due to the fear of tumor dissemination during laparoscopy, to difficulty in achieving adequate lymphadenectomy, and to complexity of laparoscopic liver resection.

The aim of this study is to review the available literature on feasibility and postoperative and oncologic outcomes of MiRC for patients affected by T1b or more advanced GbC.

2. Materials and Methods

Clinical case studies reporting on patients affected by GbC who underwent MiRC, meaning that laparoscopic or robot-assisted approach was used for both liver resection and locoregional lymph nodes excision, were included in the current review. Case reports, case series of MiRC, and case-control studies of MiRC versus open approach RC were reviewed. We included studies describing MiRC both elective, that is, performed when GbC was suspected before cholecystectomy, and revisional, that is, performed as a completion treatment after a GbC was diagnosed following a simple cholecystectomy. Articles reporting on patients undergoing simple LC for GbC, as well as those undergoing minimally invasive locoregional lymphadenectomy without liver resection, were excluded from this analysis. We systematically searched Medline (through PubMed) [13, 14] for all years to June 2016 (last PubMed search was performed on June 10, 2016).

Initially, searches employing MeSH terms were performed for keywords and text (title or abstract). As shown in Table 1, search terms were organized in three main groups (search number: 3, 11, and 12), which were further combined with each other finally resulting in the identification of 242 manuscripts. In addition, a “manual” research using the “related articles” function was used in order to “explode” research, and results were supplemented by further searches of reference lists of other articles, resulting in the identification of additional 24 manuscripts. Titles, abstracts, and full texts of resulting 266 manuscripts were independently reviewed by two authors (GZ and AM) to assess whether the studies met the eligibility criteria. Contrasting results between GZ and AM were discussed case by case, until an agreement was found. Included articles could be classified in case reports and series of MiRC for GbC and case-control studies comparing results of MiRC versus open radical cholecystectomy. An intention-to-treat analysis was performed; consequently, cases converted to open procedures were included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Search strategy for Medline.

| Search number | Search term | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mininvasive surgical procedures [MeSH] | 411011 |

| 2 | Laparoscopy [MeSH] | 77653 |

| 3 | 1 OR 2 | 411011 |

| 4 | Hepatectomy [MeSH] | 24427 |

| 5 | Liver resection | 46716 |

| 6 | Hepatic resection | 15180 |

| 7 | Segmentectomy | 8995 |

| 8 | Radical cholecystectomy | 479 |

| 9 | Extended cholecystectomy | 419 |

| 10 | Lymphadenectomy | 47649 |

| 11 | 4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 OR 9 OR 10 | 56877 |

| 12 | (Gallbladder OR Gall bladder) cancer OR tumor OR carcinoma OR neoplasm | 13250 |

| 13 | 3 AND 11 AND 12 | 242 |

3. Results

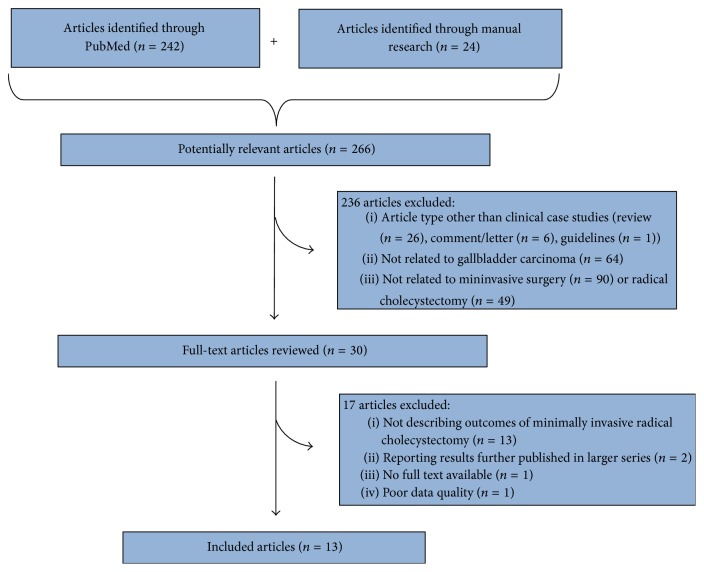

According to the aforementioned criteria, of 266 manuscripts identified by Medline (through PubMed) and by manual research, 236 were initially excluded by title or abstract analysis, leading to 30 articles. Such articles, if available, were further reviewed by full text analysis, finally leading to 13 articles [15–26,13] whose content was considered relevant for the current review (Figure 1). Table 2 shows characteristics of articles included in our study.

Figure 1.

Strategy for article search and selection.

Table 2.

Type of articles included in this review.

Of 168 patients included in the 13 aforementioned studies, 16 underwent a LC according to study protocol [22, 27]. Of the remaining 152 patients who underwent an attempt of MiRC, minimally invasive approach was laparoscopic in 147 patients and robotic in 5 patients. Overall, 15 (10%) patients were converted to an open procedure according to study protocol in one case [17], due to postcholecystectomy adhesions which made peritoneal laparoscopic exploration unfeasible in 11 cases [17], due to intraoperative portal bleeding in one case [21], and due to intraoperatively detected persisting bile leak from the liver bed in the remaining case [17]. MiRC was attempted as an elective procedure for a preoperative suspicion of GbC in 110 patients and as a completion procedure following diagnosis of GbC on a cholecystectomy specimen in the remaining 42 patients. MiRC included at least a resection of the liver bed in all but 5 patients who, according to the corresponding study protocol [23], underwent simple cholecystectomy because the GbC was located on the peritoneal side of the gallbladder. Liver resection consisted in liver bed resection in 98 patients (with a liver bed thickness ranging between 2 mm [22] and 3 to 5 cm [18, 19]), segment 4b-5 resection in 49 patients [15, 24, 26], and extended right hepatectomy in 2 patients [21]. Laparoscopic intraoperative ultrasonography was performed during MiRC in seven studies. Locoregional nodal excision was performed in all patients and represented the initial resective procedure in 7 studies. Port site excision was performed in 8 out of 42 (19%) patients who underwent completion MiRC (Table 3).

Table 3.

MiRC for GbC: surgical technique details.

| Author, year of publication | Study period | Patients number | Attempted MiRC | Conversion to open RC, rate | Completion/ elective |

Liver resection | LIOUS | Liver transection technique | Type of liver resection | LB thickness | Nodal excision | Port site excision | Nodal excision first | Pringle | CBD resection (patients number) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cho et al., 2008 [16] | NS | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0/3 | Yes | Yes | Harmonic scalpel, clips | LB | 2 cm | Yes | — | Yes | No | No |

| de Aretxabala et al., 2010∗ [17] | 2005–2009 | 18 | 18 | 13/18 | 18/0 | Yes | No | Harmonic scalpel, clips, vascular stapler | LB | NS | Yes | No | Yes | Only if needed | No |

| Gumbs and Hoffman, 2010 [18] | NS | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1/2 | Yes | Yes | Harmonic scalpel, bipolar, clips | LB | 3–5 cm | Yes | 1/1 | Yes | No | No |

| Gumbs and Hoffman, 2010 [19] | NS | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0/6 | Yes | Yes | Harmonic scalpel, bipolar, clips | LB | 3–5 cm | Yes | — | Yes | No | Yes (1) |

| Belli et al., 2011 [25] | 2006–2008 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4/0 | Yes | NA | NA | Wedge | 2 cm | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 0 |

| Shen et al., 2012£ [20] | 2010-2011 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 2/3 | Yes | No | Harmonic scalpel, electric hook | LB | 2 cm | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Gumbs et al., 2013# [21] | 2005–2011 | 15 | 15 | 1/15 | 5/10 | Yes | Yes | NS | LB& | 1 cm | Yes | No | No | NS | No |

| Machado et al., 2015 [15] | 2015 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1/0 | Yes | No | Bipolar forceps | S4b-5 | — | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Yoon et al., 2015 [22] | 2004–2014 | 45 | 32 | 1/32 | 0/32 | Yes | Yes | NS | LB | 2 mmç | Yes | — | No | No | No |

| Shirobe and Maruyama, 2015 [23] | 2001–2013 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 7/4 | 6/11∧ | Yes | Harmonic scalpel, BiClamp | LB | 1 cm | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes (2) |

| Agarwal et al., 2015 [26] | 2011–2013 | 24 (versus 46 open) | 24 | 0 | 4/20 | Yes | No | Harmonic scalpel, ultrasonic aspirator | S4b-5 | — | Yes | 4/4 | No | No | No |

| Itano et al., 2015# [27] | 2007–2013 | 19 (versus 14 open) | 16 | 0 | 0/16 | Yes | Yes | Harmonic scalpel | LB | 1 cm | Yes | — | No | No | No |

| Palanisamy et al., 2016 [24] | 2008–2013 | 14 | 14 | 0 | 0/14 | Yes | No | Harmonic scalpel, ligasure, ultrasonic aspirator | S4b-5 | — | Yes | — | Yes | No | No |

MiRC: minimally invasive radical cholecystectomy, RC: radical cholecystectomy, GbC: gallbladder cancer, LIOUS: laparoscopic intraoperative ultrasonography, LB: liver bed, NS: not specified, and S4b-5: liver segments 4b + 5.

∗Patients who underwent only laparoscopic exploration were excluded from the current analysis.

£Robot-assisted radical cholecystectomies.

#Multicenter retrospective study.

&Two patients underwent extended right hepatectomy.

çData reported in a previous paper from the same study group [28].

∧Liver bed resection not performed if tumor located on the peritoneal side of the gallbladder.

Mean intraoperative blood loss was 150 cl (range: 0–1500 cl); mean operation duration was 235 minutes (89–490 min). Overall, 15 patients (10%) out of 152 who underwent an attempt of MiRC experienced postoperative morbidity, while postoperative mortality was nil. Following MiRC, mean length of hospital stay was 5 (2 to 19) days. Final pathology data were available for 144 patients and revealed T0-1a, T1b, T2, and T3 GbC in 9, 36, 81, and 18 cases, respectively. Mean retrieved lymph node number ranged between three and 13; lymph node status was N0 in 115 patients, N1 in 21, and NX in the remaining 8. R0 resection was obtained in all patients undergoing MiRC. Long-term survival outcomes were reported in 11 studies: after a mean follow-up duration ranging between 11 and 84 months, 14 patients experienced disease recurrence, whose location was specified in 10 cases. No port site recurrence was observed during follow-up (Table 4).

Table 4.

MiRC for GbC: intraoperative and postoperative outcomes and pathologic findings.

| Author, year of publication | Mean blood loss, mL (range) | Mean operation duration, min (range) | Morbidity | Mortality | Mean LOS, days (range) | Mean f-up duration, months | DFS at last f-up, rate | Recurrence location | T0-T1a/T1b/T2/T3 | Mean number of resected nodes, (range) | NX/N0/N+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cho et al., 2008 [16] | Minor | 102 (89–146) |

0 | 0 | 5 (4–7) |

15 | 100% | — | 1/0/2/0 | 4 (4-5) |

0/3/0 |

| de Aretxabala et al., 2010 [17] | NS | NS | 0 | 0 | 3 NS |

22 | 80% | Peritoneum (case 1) | 3/13/5/2$ | 6 (3–12) |

8/14/1$ |

| Gumbs and Hoffman, 2010§ [18] | 117 (50–200) |

227 (120–360) |

0 | 0 | 4 (3–5) |

NS | NS | NS | 0/1/0/0 | 3 (1–6) |

0/1/0 |

| Gumbs and Hoffman, 2010§ [19] | 137 (50–300) |

204 (95–360) |

0 | 0 | 4 (3-4) |

NS | NS | NS | 0/0/0/1 | 3 (1–6) |

0/0/1 |

| Belli et al., 2011 [25] | 85 | 162 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 33 | 100% | No | NA | NA | NA |

| Shen et al., 2012£ [20] | 210 (50–400) |

200 (120–360) |

0 | 0 | 7 | 11 | 80% | NS | 0/0/2/3 | 9 (3–11) |

0/2/3 |

| Gumbs et al., 2013# [21] | 160 (0–400) |

220 (120–480) |

0& | 0 | 4 (2–8) |

23 | 87% | Hep pedicle (case 1) Liver (case 2) |

0/8/4/3 | 4 (1–11) |

0/12/3 |

| Machado et al., 2015 [15] | 240 | 300 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 12 | 100% | — | 0/1/0/0 | 9 | 0/1/0 |

| Yoon et al., 2015 [22] | 100 (10–1500) |

205 (90–360) |

6/32 | 0 | 4 (2–13) |

60 | 95% | Liver (case 1) Lung (case 2) Liver + lung (case 3) Colon (case 4) |

0/7/25/0 | 7 (1–15) |

0/27/5 |

| Shirobe and Maruyama, 2015 [23] | 92 (10–643) |

196 (150–490) |

1/11 | 0 | 6 (4–19) |

84 | 82% | Hep pedicle + pleural (case 1) Hep pedicle (case 2) |

0/3/8/0 | 13 (9–18) |

0/11/0 |

| Agarwal et al., 2015∗ [26] | 200 (100–850) |

270 (180–340) |

3/24 | 0 | 5 (3–16) |

18 | 96% | Hep pedicle (case 1) | 4/1/11/8 | 10 (4–31) |

0/19/5 |

| Itano et al., 2015% [27] | 152 (±90) |

368 (±73) |

1/16 | 0 | 9 (±1.6) |

37 | 100% | — | 1/2/13/0 | 13 (±3.1) |

0/16/0 |

| Palanisamy et al., 2016% [24] | 196 (±73) |

212 (±26) |

4/14 | 0 | 5 (±0.9) |

51 | 75% | NS | 0/0/11/1 | 8 (4–14) |

0/9/3 |

MiRC: minimally invasive radical cholecystectomy, GbC: gallbladder cancer, f-up: follow-up, DFS: disease-free survival, NS: not specified, and LOS: length of hospital stay.

§Pathologic findings available for only one patient.

#Multicenter retrospective study.

$Data regarding 23 patients affected by GbC initially included in the study (including 5 patients who underwent only laparoscopic exploration, without attempt for MiRC).

& The absence of postoperative bile leak, abdominal collection, and need for reoperation.

∗Blood loss, operation duration, LOS, and resected nodes # are expressed in median (range).

%Blood loss, operation duration, LOS, and resected nodes # are expressed in mean (±standard deviation). Only 12 patients affected by GbC were included in pathological and survival analysis.

4. Discussion

In the current review, we retrospectively analyzed perioperative and oncologic outcomes of 152 patients, from the 13 studies reporting on MiRC for GbC available in PubMed up to June 2016. Despite the absence of randomized clinical trial comparing results of MiRC with open RC and the limited number of patients included in this review, current evidence seems to support MiRC, both in an elective setting, when RC is performed in case of suspected GbC before cholecystectomy is performed, and in a completion setting, meaning that RC is performed after GbC has been incidentally diagnosed on a cholecystectomy specimen. Available studies report low rates of conversion to open procedure and of intraoperative complication for MiRC with limited intraoperative blood loss, paralleled by nil mortality, acceptable morbidity rates, and short length of stay following surgery, making MiRC feasible and safe. In addition, two comparative studies reported a comparable number of retrieved lymph nodes and a comparable survival rate between MiRC and open RC, supporting oncological validity of MiRC [26, 27].

The ideal surgical management of patients affected by GbC is related to the tumor stage, being simple cholecystectomy sufficient for patients affected by Tis or T1a tumor. In this context, increasing scientific evidence has shown that oncologic outcomes of LC are similar to open cholecystectomy for Tis and T1a GbC [7]. In contrast, for patients affected by T1b or higher stage tumor necessitating RC, a minimally invasive approach is questioned by majority of HPB surgeons.

Skepticism concerning MiRC is mainly related to historical studies which have previously associated tumor recurrence with laparoscopic approach among patients affected by incidental GbC, undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy [29–32]. In particular, reports concerning port site recurrence and peritoneal dissemination of cancer cells [33–40] brought about a cautionary note about the use of laparoscopy in patients in whom GbC was suspected, making GbC a formal contraindication for laparoscopy. Additional reports correlated the occurrence of port sites and peritoneal implantation to the association of CO2 pneumoperitoneum effect and imprecise handling of gallbladder during laparoscopy leading to accidental perforation of gall bladder [36, 40–42]. Port site and peritoneal recurrence may occur through direct and indirect implantation of tumor cells, during the laparoscopic procedure [43]. Direct implantation may depend on seeding of exfoliated malignant cells during tumor extraction without a protective bag or on contact with instruments contaminated with tumor cells. Indirect contamination may be related to pneumoperitoneum, based on an “aerosol” effect with dissemination of exfoliated tumor cells to the port sites during the turbulence of insufflation or to a “chimney” effect with tumor cells wound implantation during desufflation [44]. However, increasing evidence highlights the role of gentle manipulation of gallbladder and of the use of plastic bag for specimen extraction in reducing the rate of port site and peritoneal tumor implantation [23, 24, 40], while pneumoperitoneum per se seems to have a limited role in the development of such complications. Consistent with this hypothesis, we currently found that, among 10 patients whose disease recurrence following MiRC was specified in detail, no peritoneal or port site recurrence occurred, further supporting the hypothesis that laparoscopic approach is not directly responsible for increasing the risk of peritoneal and port site dissemination, provided that gallbladder wall is not damaged and GbC is not exposed during MiRC.

RC is a complex procedure, consisting in liver bed or more extended anatomic liver resection, associated with hepatic pedicle lymph node dissection, eventually extended to peripancreatic and para-aortic lymph nodes, and, eventually, in selected cases, to common bile duct resection and reconstruction. Intrinsic technical difficulty of performing such procedures by minimally invasive approach represents an additional factor slowering MiRC acceptance. Concerning liver resection, the technique of laparoscopic liver resection has already been established [45], and radical laparoscopic surgeries for liver diseases have been demonstrated to show outcomes equal to those of open surgeries [46, 47]. Although the thickness of liver parenchyma to resect during RC remains a matter of debate, current evidence supports safety and feasibility of a minimally invasive approach for liver bed resection, as well as for segmentectomy 4b-5.

GbC has a high tendency to lymphatic invasion; thus, an adequate lymphadenectomy, commonly identified as the retrieval of at least six lymph nodes, is required to obtain a proper tumor staging [10, 38, 48]. Hepatic portal pedicle is a complex structure, containing important and delicate elements whose damage during lymphadenectomy may result in uncontrollable bleeding or injury to bile duct. This has brought about question of safety and adequacy of laparoscopic lymphadenectomy for GbC, representing an obstacle to the advancement of MiRC for GbC. However, current evidence suggests that laparoscopic lymphadenectomy may yield outcomes similar to those following open approach RC, with a mean number of dissected lymph nodes ranging between three [18, 19] and 13 [23, 27] among 13 studies analyzed in the current review. In addition, two studies [26, 27] comparing results of MiRC and of open RC did not show statistical difference between two approaches concerning the mean number of lymph nodes retrieved.

Finally, concerning bile duct resection and reconstruction, this can be indicated during RC only if the cystic duct margin is positive and although in some of the analyzed studies such situation represented an indication to open RC [22, 27], it does not represent an absolute contraindication to MiRC. Two of the 13 studies reviewed in the current analysis report on overall 3 patients who underwent a MiRC associated with common bile duct resection and biliojejunal reconstruction, none of them developing postoperative complications related to the procedure.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, available data on MiRC for GbC show encouraging results in terms of perioperative and oncologic outcomes. However, the limited number of descriptive studies reporting on patients undergoing MiRC, as well as the absence of randomized clinical trials comparing MiRC and open RC, does not allow for recommending MiRC outside highly specialized centers with adequate experience in hepatobiliary and laparoscopic surgery.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group. A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(20):2050–2059. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa032651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colon Cancer Laparoscopic or Open Resection Study Group, Buunen M., Veldkamp R., et al. Survival after laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: long-term outcome of a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Oncology. 2009;10(1):44–52. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(08)70310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiland S. T., Mahvi D. M., Niederhuber J. E., et al. Should suspected early gallbladder cancer be treated laparoscopically? Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2002;6(1):50–57. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(01)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin K., Lan H., Zhu T., He K., Teng L. Gallbladder carcinoma incidentally encountered during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: how to deal with it. Clinical and Translational Oncology. 2011;13(1):25–33. doi: 10.1007/s12094-011-0613-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Misra M. C., Guleria S. Management of cancer gallbladder found as a surprise on a resected gallbladder specimen. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2006;93(8):690–698. doi: 10.1002/jso.20537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toyonaga T., Chijiiwa K., Nakano K., et al. Completion radical surgery after cholecystectomy for accidentally undiagnosed gallbladder carcinoma. World Journal of Surgery. 2003;27(3):266–271. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6609-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang J. Y., Heo J. S., Han Y., et al. Impact of type of surgery on survival outcome in patients with early gallbladder cancer in the era of minimally invasive surgery. Oncologic Safety of Laparoscopic Surgery. Medicine. 2016;95(22):1–7. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000003675.e3675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon E., Vollmer C. M., Jr., Sahajpal A., et al. An aggressive surgical approach leads to improved survival in patients with gallbladder cancer: a 12-year study at a North American Center. Annals of Surgery. 2005;241(3):385–394. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000154118.07704.ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kondo S., Takada T., Miyazaki M., et al. Guidelines for the management of biliary tract and ampullary carcinomas: surgical treatment. Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 2008;15(1):41–54. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito H., Ito K., D'Angelica M., et al. Accurate staging for gallbladder cancer: implications for surgical therapy and pathological assessment. Annals of Surgery. 2011;254(2):320–325. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e31822238d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi S. B., Han H. J., Kim C. Y., et al. Fourteen year surgical experience of gallbladder cancer: validity of curative resect. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59(113):36–41. doi: 10.5754/hge10297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aloia T. A., Járufe N., Javle M., et al. Gallbladder Cancer: expert consensus statement. HPB. 2015;17(8):681–690. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahid S. S., Hornung C. A., Minor K. S., Turina M., Galandiuk S. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis for the surgeon scientist. British Journal of Surgery. 2006;93(11):1315–1324. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews. 2015;4(1) doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Machado M. A., Makdissi F. F., Surjan R. C. Totally Laparoscopic Hepatic Bisegmentectomy (s4b+s5) and Hilar Lymphadenectomy for Incidental Gallbladder Cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2015;22:336–339. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4650-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho A., Yamamoto H., Nagata M., et al. Total laparoscopic resection of the gallbladder together with the gallbladder bed. Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 2008;15(6):585–588. doi: 10.1007/s00534-008-1363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Aretxabala X., Leon J., Hepp J., Maluenda F., Roa I. Gallbladder cancer: role of laparoscopy in the management of potentially resectable tumors. Surgical Endoscopy and Other Interventional Techniques. 2010;24(9):2192–2196. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0925-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gumbs A. A., Hoffman J. P. Laparoscopic completion radical cholecystectomy for T2 gallbladder cancer. Surgical Endoscopy. 2010;24(12):3221–3223. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gumbs A. A., Hoffman J. P. Laparoscopic radical cholecystectomy and Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy for gallbladder cancer. Surgical Endoscopy and Other Interventional Techniques. 2010;24(7):1766–1768. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0840-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen B. Y., Zhan Q., Deng X. X., et al. Radical resection of gallbladder cancer: could it be robotic? Surgical Endoscopy. 2012;26(11):3245–3250. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gumbs A. A., Jarufe N., Gayet B. Minimally invasive approaches to extrapancreatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surgical Endoscopy. 2013;27(2):406–414. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoon Y.-S., Han H.-S., Cho J. Y., et al. Is laparoscopy contraindicated for gallbladder cancer? A 10-year prospective cohort study. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2015;221(4):847–853. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shirobe T., Maruyama S. Laparoscopic radical cholecystectomy with lymph node dissection for gallbladder carcinoma. Surgical Endoscopy. 2015;29(8):2244–2250. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3932-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palanisamy S., Patel N., Sabnis S., et al. Laparoscopic radical cholecystectomy for suspected early gall bladder carcinoma: thinking beyond convention. Surgical Endoscopy. 2016;30(6):2442–2448. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belli G., Cioffi L., D'Agostino A., et al. Revision surgery for incidentally detected early gallbladder cancer in laparoscopic era. Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques. 2011;21(6):531–534. doi: 10.1089/lap.2011.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agarwal A. K., Javed A., Kalayarasan R., Sakhuja P. Minimally invasive versus the conventional open surgical approach of a radical cholecystectomy for gallbladder cancer: a retrospective comparative study. HPB. 2015;17(6):536–541. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Itano O., Oshima G., Minagawa T., et al. Novel strategy for laparoscopic treatment of pT2 gallbladder carcinoma. Surgical Endoscopy and Other Interventional Techniques. 2015;29(12):3600–3607. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4116-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho J. Y., Han H.-S., Yoon Y.-S., Ahn K. S., Kim Y.-H., Lee K.-H. Laparoscopic approach for suspected early-stage gallbladder carcinoma. Archives of Surgery. 2010;145(2):128–133. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koshenkov V. P., Koru-Sengul T., Franceschi D., Dipasco P. J., Rodgers S. E. Predictors of incidental gallbladder cancer in patients undergoing cholecystectomy for benign gallbladder disease. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2013;107(2):118–123. doi: 10.1002/jso.23239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan K.-M., Yeh T.-S., Jan Y.-Y., Chen M.-F. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for early gallbladder carcinoma: long-term outcome in comparison with conventional open cholecystectomy. Surgical Endoscopy. 2006;20(12):1867–1871. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun C. D., Zhang B. Y., Wu L. Q., Lee W. J. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for treatment of unexpected early-stage gallbladder cancer. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2005;91(4):253–257. doi: 10.1002/jso.20318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cavallaro A., Piccolo G., Panebianco V., et al. Incidental gallbladder cancer during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: managing an unexpected finding. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;18(30):4019–4027. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i30.4019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaeff B., Paolucci V., Thomopoulos J. Port site recurrences after laparoscopic surgery. A review. Digestive Surgery. 1998;15(2):124–134. doi: 10.1159/000018605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohmura Y., Yokoyama N., Tanada M., Takiyama W., Takashima S. Port site recurrence of unexpected gallbladder carcinoma after a laparoscopic cholecystectomy: report of a case. Surgery Today. 1999;29(1):71–75. doi: 10.1007/s005950050360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Z'graggen K., Birrer S., Maurer C. A., Wehrli H., Klaiber C., Baer H. U. Incidence of port site recurrence after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for preoperatively unsuspected gallbladder carcinoma. Surgery. 1998;124(5):831–838. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(98)70005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee J.-M., Kim B.-W., Kim W. H., Wang H.-J., Kim M. W. Clinical implication of bile spillage in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy for gallbladder cancer. The American Surgeon. 2011;77(6):697–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto H., Hayakawa N., Kitagawa Y., et al. Unsuspected gallbladder carcinoma after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 2005;12(5):391–398. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-0996-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shirai Y., Yoshida K., Tsukada K., Muto T. Inapparent carcinoma of the gallbladder. An appraisal of a radical second operation after simple cholecystectomy. Annals of Surgery. 1992;215(4):326–331. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199204000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Aretxabala X., Roa I., Burgos L., et al. Gallbladder cancer: an analysis of a series of 139 patients with invasion restricted to the subserosal layer. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2006;10(2):186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evrard S., Falkenrodt A., Park A., Tassetti V., Mutter D., Marescaux J. Influence of CO2 pneumoperitoneum on systemic and peritoneal cell-mediated immunity. World Journal of Surgery. 1997;21(4):353–357. doi: 10.1007/pl00012252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varshney S., Buttirini G., Gupta R. Incidental carcinoma of the gallbladder. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2002;28(1):4–10. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2001.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paolucci V. Port site recurrences after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. 2001;8(6):535–543. doi: 10.1007/s005340100022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drouard F., Delamarre J., Capron J.-P. Cutaneous seeding of gallbladder cancer after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;325(18):1316–1319. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110313251816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neuhaus S. J., Texler M., Hewett P. J., Watson D. I. Port-site metastases following laparoscopic surgery. British Journal of Surgery. 1998;85(6):735–741. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Itano O., Ikoma N., Takei H., Oshima G., Kitagawa Y. The superficial precoagulation, sealing, and transection method: a ‘bloodless’ and ‘ecofriendly’ laparoscopic liver transection technique. Surgical Laparoscopic Endoscopic Percutaneous Technology. 1097;25(1):e33–e36. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han H. S., Yoon Y. S., Cho J. Y., Hwang D. W. Laparoscopic liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: korean experiences. Liver Cancer. 2013;2(1):25–30. doi: 10.1159/000346224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nguyen K. T., Gamblin T. C., Geller D. A. World review of laparoscopic liver resection-2,804 patients. Annals of Surgery. 2009;250(5):831–841. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b0c4df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Negi S. S., Singh A., Chaudhary A. Lymph nodal involvement as prognostic factor in gallbladder cancer: location, count or ratio? Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2011;15(6):1017–1025. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1528-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]