Abstract

AIM

To summarize clinical presentations and treatment options of spinal gout in the literature from 2000 to 2014, and present theories for possible mechanism of spinal gout formation.

METHODS

The authors reviewed 68 published cases of spinal gout, which were collected by searching “spinal gout” on PubMed from 2000 to 2014. The data were analyzed for clinical features, anatomical location of spinal gout, laboratory studies, imaging studies, and treatment choices.

RESULTS

Of the 68 patients reviewed, the most common clinical presentation was back or neck pain in 69.1% of patients. The most common laboratory study was elevated uric acid levels in 66.2% of patients. The most common diagnostic image finding was hypointense lesion of the gout tophi on the T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scan. The most common surgical treatment performed was a laminectomy in 51.5% and non-surgical treatment was performed in 29.4% of patients.

CONCLUSION

Spinal gout most commonly present as back or neck pain with majority of reported patients with elevated uric acid. The diagnosis of spinal gout is confirmed with the presence of negatively birefringent monosodium urate crystals in tissue. Treatment for spinal gout involves medication for the reduction of uric acid level and surgery if patient symptoms failed to respond to medical treatment.

Keywords: Spinal, Gout, Tophi, Monosodium urate

Core tip: Gout is a common inflammatory arthritis that rarely affects the spine. In such cases, patients may experience back pain, myelopathic symptoms and radiculopathy. Clinical findings are non-specific. Therefore, it is necessary to have an awareness of the diagnosis, especially in patients with a clinical history of gout and/or elevated inflammatory markers and hyperuricemia. While magnetic resonance imaging is the major non-invasive diagnostic method, all suspicious findings on imaging require surgical sampling for pathological confirmation. While typical uric acid lowering medications are first-line therapy, cord compression or continued symptoms may necessitate operative intervention if medications fail.

INTRODUCTION

Gout is a common inflammatory arthritis with an increase in prevalence over the last 20 years. It currently affects over 8 million Americans. The clinical presentation of gout depends on the site of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals precipitation and the subsequent inflammatory response that ensues in the synovial joints and soft tissues. Gout usually manifests as a monoarticular arthritis in the lower extremities. If untreated, nodular masses of MSU crystals called tophi may eventually deposit in extraarticular locations, such as, the axial skeleton. Although traditionally thought of as a rare complication, recent study suggests that axial gout may be more prevalent than suspected[1]. Gout affecting the spinal column will typically present with neurological compromise, localized pain, and lytic vertebral lesions[2,3]. Spinal gout can affect the facet joint, laminae, ligamentum flavum, as well as the epidural space[4].

From 2000 to 2014, approximately 68 case reports have been published on spinal gout. The current manuscript summarizes the most common presenting features, imaging findings, and treatment choices based on the 68 published cases. A case is also presented to provide illustration on the topic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature review

A PubMed literature search using the key words spinal gout, from January 2000 to December 2014, limited to human studies and restricted to English language literature resulted in 221 publications. Abstracts and articles were then reviewed for content. Articles kept for review included patients who underwent treatment for spinal gout. Furthermore, data required for inclusion in the study included: Patient demographics, clinical presentation, laboratory findings, imaging studies, and treatment methods were collected (Table 1). Articles excluded from the study were those that did not have patients diagnosed with spinal gout and those that did not include patient demographics, clinical presentation, laboratory findings, imaging studies, and treatment methods. After review, a total of 54 peer reviewed articles met the above criteria and were included for data collection.

Table 1.

List of patient cases of spinal gout in the literature since 2000

| No. | Year | Ref. | Age/sex | Site | Sx/Signs | Duration | Hx Gout | Tophi | Relevant Hx | Hi Urate | MRI T1 | T2 | Gad | Tx |

| 1 | 2000 | Kao et al[5] | 82 M | T10-T11 | LE weakness | 1 mo | Y | NA | NA | Y | Iso | Hypo | NA | T9-T11 lamina |

| 2 | 2000 | Mekelburg et al[6] | 60 M | L2-3 | Back pain | 5 mo | Y | NA | NA | Y | NA | NA | NA | Cervical lamina |

| 3 | 2000 | Paquette et al[7] | 56 M | L3 | Back pain, radicular pain | 6 yr | N | NA | Arthritis | NA | NA | Hypo | NA | Surgery |

| 4 | 2000 | Thornton et al[8] | 27 M | L3-L4 | Back pain | 1 d | Y | NA | RT | Y | Hypo | NA | Y | Medical NOS |

| 5 | 2001 | Barrett et al[9] | 70 M | L5-S1 | Back pain, radicular pain, fever | 2 d | Y | NA | RI | N | NA | Hyper | Y | Lamina |

| 6 | 2001 | St George et al[10] | 60 M | T1-T2 | LE weakness, BBD | 6 wk | Y | N | NA | NA | NA | Hypo | NA | T1-T2 lamina |

| 7 | 2001 | Wang et al[11] | 28 M | T9-T10 | LE weakness | 1 d | Y | N | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | T9-T10 lamina |

| 8 | 2002 | Hsu et al[12] | 72 M | L4-S1 | Back pain, radicular pain | 18 mo | Y | NA | NA | Y | Hypo | Hyper | Y | Lamina |

| 9 | 2002 | Hsu et al[12] | 77 M | L3-L5 | Back pain, radicular pain | 12 mo | N | NA | NA | Y | Hypo | Hypo | Y | Lumbar lamina |

| 10 | 2002 | Hsu et al[12] | 83 M | T9-T11 | LE weakness | 1 mo | Y | NA | NA | N | Hypo | Hypo | Y | Lamina |

| 11 | 2002 | Hsu et al[12] | 27 M | L2-S1 | Back pain | 6 mo | Y | NA | NA | Y | Hypo | Hyper | Y | Medical NOS |

| 12 | 2002 | Souza et al[13] | 49 M | T9-T10 | Back pain, LE weakness | 6 mo | Y | NA | NA | NA | Iso | Hypo | Y | T9-T11 lamina |

| 13 | 2002 | Yen et al[14] | 68 M | C4-C5 | Quadriparesis | 2 wk | Y | NA | RI | Y | Hypo | Hypo | NA | Surgery |

| 14 | 2003 | Diaz et al[15] | 74 M | C4-C5 | Quadriparesis | 1 wk | Y | Y | NA | Y | NA | NA | NA | C4-C5 lamina |

| 15 | 2004 | Draganescu et al[16] | 48 F | L4 | Radicular pain | 1 d | Y | Y | Diuretic | Y | NA | Hetero | Y | L4-L5 lamina |

| 16 | 2004 | El Sandid et al[17] | 32 M | T7-T9 | Back pain, fever | Acute | Y | NA | NA | Y | NA | NA | NA | Lamina |

| 17 | 2004 | Nakajima et al[18] | 39 M | L4-5 | Low back pain | NA | Y | Y | Arthritis | Y | NA | NA | Y | Medical |

| 18 | 2005 | Beier et al[19] | 29 M | L4-L5 | Back pain, L5 radiculopathy | Acute | N | N | NA | Y | NA | NA | NA | L4-L5 lamina |

| 19 | 2005 | Celik et al[20] | 48 M | C1-C2 | Neck pain, radiculopathy, paresthesias | 2 mo | N | Y | Alcohol | Y | Hypo | Hyper | Y | Medical NOS |

| 20 | 2005 | Chang[21] | 60 M | L3-L4 | B/L L4 radiculopathy | NA | Y | NA | NA | Y | Hypo | Hypo | Y | Surgery |

| 21 | 2005 | Chang[21] | 72 M | L4-S1 | Back pain, claudication | 2 wk | Y | NA | NA | Y | Hypo | Hypo | Y | Surgery |

| 22 | 2005 | Chang[21] | 66 F | L4-L5 | Back pain, claudication | 1 mo | Y | NA | NA | Y | Hypo | Hypo | Y | Surgery |

| 23 | 2005 | Chang[21] | 63 M | L3-S1 | Back pain, claudication, fever | 2 wk | NA | NA | NA | N | Hypo | Hypo | Y | Surgery |

| 24 | 2005 | Kelly et al[22] | 56 F | L4 | Back pain, LE weakness | 1 mo | Y | NA | RA, DM, RI | NA | Iso | Hypo | Y | L4-L5 lamina |

| 25 | 2005 | Mahmud et al[23] | 47 M | L4-L5 | Radiculopathy | 3 mo | Y | NA | NA | Y | NA | NA | NA | L4-L5 lamina/facet |

| 26 | 2005 | Mahmud et al[23] | 71 F | L4-L5 | Back pain, radiculopathy | 4 mo | N | NA | NA | N | NA | Hetero | NA | L4-L5 lamina/fusion |

| 27 | 2005 | Mahmud et al[23] | 58 M | L4-L5 | Back pain, claudication | 6 mo | N | NA | NA | N | NA | Hyper | NA | L5 lamina |

| 28 | 2005 | Wazir et al[24] | 66 F | C1-C2 | Chronic neck pain, A-A subluxation, quadriparesis | 2 mo | N | N | Arthritis | Y | NA | NA | NA | Lamina/fusion |

| 29 | 2005 | Yen et al[25] | 65 F | L5-S1 | Back pain, LE weakness | 10 mo | N | NA | NA | NA | Iso | Hetero | Y | L5-S1 lamina |

| 30 | 2006 | Dharmadhikari et al[26] | 66 F | C3-C7 | Cord compression, quadriparesis, falls | 2-3 mo | N | N | NA | NA | Hypo | Hypo | N | C3-C6 vertebrectomy |

| 31 | 2006 | Hou et al[27] | 37 M | L5-S1 | Back pain, fever | 5 d | Y | N | RT | Y | Iso | Iso | Y | Medical NOS |

| 32 | 2006 | Oaks et al[28] | 32 M | T5-T8 | Back pain, myelopathy | NA | Y | NA | NA | NA | Hetero | Hetero | Y | Lamina |

| 33 | 2006 | Pankhania et al[29] | 68 M | C4-C5 | Neck pain, quadriparesis, sensory dysfunction | 1 mo | N | N | NA | N | Iso | Hetero | Y | Lamina |

| 34 | 2006 | Popovich et al[30] | 36 F | T2-T9 | Paraplegia | 2 wk | Y | NA | NA | Y | Hypo | Hypo | Y | T5-T7 lamina |

| 35 | 2007 | Adenwalla et al[31] | 77 M | L5-S1 | Severe low back pain, LE weakness | 1 wk | N | N | Diurectic | Y | NA | NA | NA | Prednisone and colchicines |

| 36 | 2007 | Lam et al[32] | 65 M | L3-L4 | LE pain and numbness, BBD | Acute | Y | Y | RI | Y | NA | NA | NA | L3-L4 lamina |

| 37 | 2007 | Lam et al[32] | 63 M | L4-S1 | Chronic LE pain and paresthesia, claudication | 1 yr | Y | N | NA | N | NA | NA | NA | L4-L5 lamina/fusion |

| 38 | 2007 | Suk et al[33] | 55 M | L4-L5 | Back pain, LE weakness and paresthesia, fever | 1 wk | N | N | Alcohol | Y | Hypo | Hetero | Y | L4-L5 lamina/fusion |

| 39 | 2008 | Fontenot et al[34] | 85 F | L3-L4 | Low back pain | 2 mo | N | N | Diuretics | Y | NA | Hyper | NA | Prednisone and colchicines |

| 40 | 2009 | Chan et al[35] | 76 M | T8, T10 | LE weakness | Y | Y | NA | Y | Iso | Hetero | NA | Medical NOS | |

| 41 | 2009 | Nygaard et al[36] | 75 M | L4-L5 | Low back pain, fever | 5 d | Y | N | NA | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 42 | 2009 | Tsai et al[37] | 64 F | T8-T9 | Fever, low back pain, LE weakness | 1 d | N | N | DM, RI | N | Hypo | Iso | Y | T8-T9 discectomy and partial corpectomy |

| 43 | 2010 | Coulier et al[38] | 62 F | C6-C7 | Neck pain | NA | N | Y | NA | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 44 | 2010 | Ko et al[39] | 63 M | L5-S1 | Low back pain | 2 mo | N | N | NA | Y | Hypo | Hypo | Y | Lamina |

| 45 | 2010 | Murphy et al[40] | 82 M | NA | Back pain | 3 mo | N | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 46 | 2010 | Ntsiba et al[41] | 43 M | T9-T10 | Spastic paraplegia | 6 mo | Y | Y | Alcohol | NA | Hypo | Hyper | NA | T10 lamina |

| 47 | 2010 | Samuels et al[42] | 75 M | L5-S1 | Low back pain, radiculopathy, b/l groin pain | Acute | Y | N | DM, RI, arthritis | NA | NA | NA | NA | Steroid injection and allopurinol |

| 48 | 2011 | Ibrahim et al[43] | 70 F | T1-T2 | UE and LE weakness | 1 yr | Y | N | RI | Y | Hypo | Hyper | NA | Lamina/fusion |

| 49 | 2011 | Levin et al[44] | 34 M | T2-T5 | Paraplegia | Acute | Y | N | RI, DM | Y | NA | NA | NA | Lamina |

| 50 | 2011 | Thavarajah et al[45] | 57 M | C1-C2 | Neck pain, UE and LE tingling | 1 yr | Y | N | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | C0-C6 fusion |

| 51 | 2011 | Tran et al[46] | 73 M | C1-C2 | CN IX, X, XII palsies, fever, cough, | 3 d | Y | Y | RI | Y | NA | Hetero | NA | Allopurinol, rasburicase |

| 52 | 2012 | Federman et al[2] | 66 M | C4-C6 | Neck pain | 4 mo | N | N | DM | Y | Hypo | Hetero | NA | Allopurinol, colchicine, narcotic analgesics |

| 53 | 2012 | Hasturk et al[4] | 77 F | L4-L5 | Low back pain, radiculopathy | 5 mo | N | N | NA | N | Hypo | Hypo | Y | Surgery |

| 54 | 2012 | Sakamoto et al[3] | 69 M | L1-L2 | Back pain, radiculopathy | Acute | N | N | Heart Failure | Y | Hypo | Hypo | Y | Medical NOS |

| 55 | 201 | Yamamoto et al[47] | 58 F | C4-C7 | Malaise, fever, back pain | 3 yr | N | Y | Arthritis, RI | Y | NA | NA | NA | Prednisolone, allopurinol, benzbromarone |

| 56 | 2012 | Lu et al[48] | 29 M | L4-S1 | Severe pain, paresthesia, acratia of LLE | 3 yr | Y | Y | Chronic alcohol abuse, chronic gout | Y | Hypo | Hypo | NA | L4-L5/L5-S1 decompression/fusion |

| 57 | 2012 | Sanmillan et al[49] | 71 M | C3-C4 | Progressive Quadriparesis | 4 mo | Y | Y | Hypertension, dislipidemia | Y | Hypo | Hyper | NA | C3-C4 microdiscectomy/fusion |

| 58 | 2013 | Wendling et al[50] | 54 M | C5-C6 | Inflammatory neck pain and cervicobrachial neuralgia | Acute | Y | N | Hyperch- olesterolemia | Y | Hypo | NA | Y | Colchicine |

| 59 | 2013 | Wendling et al[50] | 52 F | Lumbar posterior facet joint | Low back pain | NA | N | Y | Polychondritis | N | NA | NA | NA | Surgery |

| 60 | 2013 | Wendling et al[50] | 72 M | C5-C6 | Acute neck pain, knee arthritis | Acute | Y | N | Hypertension | Y | NA | NA | NA | Colchicine |

| 61 | 2013 | Wendling et al[50] | 65 M | L4-L5 | Inflammatory low back pain | Acute | Y | Y | Cardio- myopathy, hypertension | Y | NA | NA | NA | Colchicine |

| 62 | 2013 | Wendling et al[50] | 87 M | L3-L5 | Inflammatory low back pain | Acute | N | Y | Hypertension, heart failure, chronic kidney failure | Y | Hypo | NA | Y | Colchicine |

| 63 | 2013 | Komarla et al[51] | 69 F | L3-S1 | Back pain, fever | Acute | N | Y | Alchohol abuse, chronic low back pain | N | NA | Hyper | NA | Allopurinol, colchicine, glucocorticoids |

| 64 | 2013 | de Parisot et al[52] | 60 M | C1-C2 | Walking disorders, urinary and bowel incontinence | 6 mo | Y | Y | NA | Y | Hypo | Hyper | Y | C1-C2 Arthrodesis |

| 65 | 2013 | Kwan et al[53] | 25 M | T9-T10, L3-S1 | Pain, swelling, and decreased ROM in multiple joints | 1 wk | N | Y | CKD | Y | Hypo | Hetero | NA | Prednisone, allopurinol |

| 66 | 2013 | Yoon et al[54] | 64 M | T5-T7 | Weakness B/L LE, back pain rad to left anterior chest, paraparesis | Weakness: 1 wk; back pain 1 mo | Y (8 yr ago) | Y | Acute gout arthritis 8 yr prior | Y | Hypo | Hetero | Y | T5-T7, laminectomy, facetectomy, pedicle screw fixation w/PL fusion |

| 67 | 2013 | Jegapragasan et al[55] | 24 M | L4-S1 | Progressively worsening LBP w/rad, weakness of RLE, fever | 3 yr LBP rad lat thight | Y (4 yr Hx) | 4 yr Tophaceous gout, CKD, 3 yr LBP, rad pain down later thigh (Rt > Lf) | Y | Iso | Hetero | NA | Decompressive laminectomy L4-S1, resection of intraspinal canal and perineural lesion; post-op: colchicine, allopurinol, brief burst of prednisone | |

| 68 | 2014 | Cardoso et al[56] | 69 W | L4-5, SI joints | LBP rad to buttocks and hips, low fever | NA | N | Y | Constrictive pericarditis, chronic renal insufficiency, HTN, DM | Y | Hypo | Iso | Y | Colchicine, allopurinol |

M: Male; F: Female; Sx: Symptoms; Hx: History; RT: Renal transplant; Hi: High; R: Right; LE: Lower extremity; RI: Renal insufficiency; BBD: Bowel/bladder dysfunction; Y and N: Yes and no; Hypo: Hypointense; Iso: Isointense; Hyper: Hyperintense; Hetero: Heterointense; UE: Upper extremity; Lamina: Laminectomy; Tx: Treatment; Gad: Gadolinium.

RESULTS

The 54 articles accounted for 68 cases of spinal gout with 51 (75%) males and 17 (25%) females and an average age of 59.2 years, 41(60.3%) had prior history of peripheral gout (Table 1).

Clinical presentations

Of the 68 spinal gout patients reviewed, 47 (69.1%) presented with localized back/neck pain, 38 (55.9%) with some form of spinal cord compression, defined as weakness, numbness, loss of bladder or bowel control, and decreased sensation below the compression level, 17 (25%) with spinal nerve root compression or radiculopathy, defined as motor dysfunction or dysesthesia along the course of a specific nerve caused by compression of its root, 13 (19.1%) with fever, 1 (1.5%) with cranial nerve palsy, and 2 (3.0%) with atlanto-axial subluxation (Table 2). Furthermore, among the sites of involvement in the 68 spinal gout patients, 38 (55.9%) were located in the lumbar region, 15 (22.1%) in the thoracic region, 15 (22.1%) in the cervical region, and 1 (1.4%) in an unspecified region (Table 3). One patient demonstrated soft tissue nodularity consistent with gouty tophi on biopsy in both the thoracic and lumbar spinal segments.

Table 2.

Clinical features

| No. of patients | |

| Localized back/neck pain | 47 |

| Spinal nerve root compression, in general | 14 |

| Radicular pain | 6 |

| Radiculopathy NOS | 8 |

| Spinal cord compression, in general | 38 |

| LE weakness | 19 |

| Quadriparesis | 6 |

| Claudication | 5 |

| Paraplegia | 4 |

| BBD | 3 |

| Myelopathy NOS | 1 |

| Cranial nerve palsy | 1 |

| Atlanto-axial subluxation | 2 |

| Fever | 13 |

NOS: Not otherwise specified; UE: Upper extremity; LE: Lower extremity; BBD: Bowel/bladder dysfunction.

Table 3.

Anatomic location of spinal gout

| No. of patients | |

| Lumbar spine | 38 |

| Thoracic spine | 15 |

| Cervical spine | 15 |

| Not mentioned | 1 |

| Total1 | 68 |

Patient No. 65 had gout in two sites, thoracic and lumbar regions.

Laboratory studies

Laboratory studies of the 68 recorded cases showed 45 (66.2%) with elevated uric acid level at the time of diagnoses, 17 (25%) had elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rates (ESR), 19 (27.9%) had increased C-reactive proteins (CRP) level, 11 (16.2%) had renal insufficiency, 9 (13.2%) had leukocytosis, and 5 (7.4%) had anemia (Table 4).

Table 4.

Laboratory studies

| No. of patients | |

| Elevated uric acid | 45 |

| Elevated ESR | 17 |

| Elevated CRP | 19 |

| Renal insufficiency | 11 |

| Leukocytosis | 9 |

| Anemia | 5 |

ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein.

Imaging studies

On the T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images, 28 (41.2%) did not report findings, 31 (45.5%) were hypointense, 8 (11.8%) were isointense, and 1 (1.5%) was heterointense. On T2-weighted images, 24 (35.3%) did not report findings, 18 (26.5%) were hypointense, 12 (17.6%) were heterointense, 11 (16.2%) were hyperintense, and 4 (5.9%) were isointense. A gadolinium (Gd)-enhanced MRI scan was obtained from 32 (47.1%) patients. These findings are referenced in (Table 5).

Table 5.

Imaging studies

| No. of patients | |

| X-ray | |

| Not performed | 37 |

| Spondylosis/-listhesis | 12 |

| Bony erosion | 8 |

| Unremarkable | 6 |

| Degenerative changes | 5 |

| CT | |

| Not performed | 35 |

| BE and HDA | 13 |

| BE only | 13 |

| Lytic lesions | 5 |

| Unremarkable | 2 |

| MRI | |

| T1 | |

| Not reported | 28 |

| Hypointense | 31 |

| Isointense | 8 |

| Heterointense | 1 |

| T2 | |

| Not reported | 24 |

| Hypointense | 18 |

| Heterointense | 12 |

| Hyperintense | 11 |

| Isointense | 4 |

| Gadolinium enhancement | |

| No | 36 |

| Yes | 32 |

BE: Bony erosion; HAD: High density attenuation; CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

Thirty-seven cases (54.4%) did not report X-ray findings, 12 (17.6%) showed spondylosis or spondylisthesis, 8 (11.8%) showed bony erosion, 6 (8.8%) were unremarkable, and 5 (7.4%) showed degenerative changes. In addition, 35 (51.5%) did not report computed tomography (CT) findings, 13 (19.1%) showed bony erosion and high density attenuation, 13 (19.1%) displayed bony erosion only, 5 (7.4%) demonstrated lytic lesions, and 2 (2.9%) were unremarkable.

Treatments

Forty-five (66.2%) patients had surgical treatment. Thirty-five (51.5%) patients had laminectomies, 8 (11.8%) of whom also had fusions with laminectomies, 7 (10.3%) had surgeries not otherwise specified, 1 (1.5%) had a vertebrectomy, 2 (2.9%) had discectomies with partial corpectomies. Twenty (29.4%) received medical treatment alone and 3 (4.4%) did not report any treatment (Table 6).

Table 6.

Treatment

| No. of patients | |

| Laminectomy only | 24 |

| Nonsurgical treatment | 20 |

| Surgery not specified | 7 |

| Laminectomy and fusion | 5 |

| Not reported | 3 |

| Fusion only | 2 |

| Laminectomy and facetectomy | 3 |

| Laminectomy and facetectomy and fusion | 1 |

| Vertebrectomy | 1 |

| Discectomy and partial corpectomy | 2 |

| Total | 68 |

Case illustration

A 58-year-old female presented with a chief complaint of low back and radicular pain over left L4, 5 dermatomes that had been progressively worsening over a four-month duration to the point where she was unable to walk. The patient denied any saddle paresthesia or change in bowel and bladder function. She has a history of cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease (stage I), type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, and obstructive sleep apnea. The patient also described an acute gouty arthropathy that was diagnosed in her right hand about 4 mo prior for which she was taking colchicine. An inflammatory workup was ordered which showed CRP of 3.58 (n < 1.0), ESR 25 (0-20), WBC 6.2 (4.0-10.0), uric acid 11.4 (2.5-6.8); HLA-B27, anti-DNA, Rheumatoid factor, and complement labs were negative.

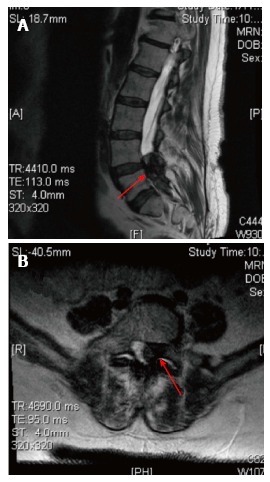

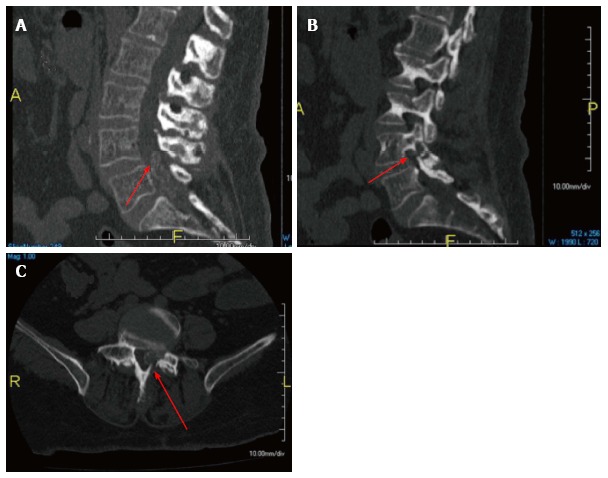

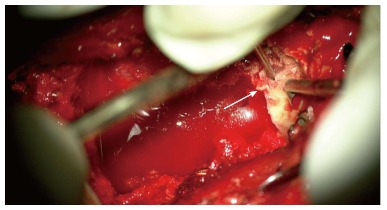

Plain radiograph of the lumbar spine was unremarkable. Plain radiograph of the right hand showed osseous erosive changes at the 4th finger distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint (Figure 1). MRI showed intraspinal extradural lesion causing spinal canal stenosis at L4-S1 (Figure 2). A CT showed that the lesion was calcified with erosive changes noted at the left L4-5 facet joint and L 4 lamina (Figure 3). The patient was treated with L4-S1 decompression, instrumentation and fusion. The surgical microscope was used during excision of the intraspinal lesion, which appeared chalky white, non-adherent and easily pealed off the thecal sac without sustaining dural tear (Figure 4). Postoperatively the patient noted significant improvement in both low back and radicular pain. The patient received allopurinol treatment for gout and remained asymptomatic at the last follow up two years after the index procedure.

Figure 1.

Plain radiograph anteroposterior view right hand showed osseous erosive changes at the 4th finger distal interphalangeal joint (arrow).

Figure 2.

T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging scan mid sagittal (A) and axial (B) showed intraspinal extradural hypodense lesion causing spinal canal stenosis at L4-S1.

Figure 3.

Computed tomography scan mid sagittal (A), left parasagittal (B), and axial (C) views showed the intraspinal lesion was calcified with erosive changes at the left L4-5 facet joint and L4 lamina (arrows).

Figure 4.

Intraoperative photograph taken by the surgical microscope showed a well-demarked chalky white tophous lesion (arrow).

DISCUSSION

Gout is a common form of inflammatory arthritis caused by the deposition of MSU crystals in synovial joints that result into erosion and joint damage. Soft tissue masses of MSU crystals known as tophi are usually found in the hand and extensor surface of the forearm[4,32,57]. Tophi are seen in patients with long-standing gout, but can also be one of the first symptoms amongst a cluster of metabolic disorders leading to hyperuricemia, especially among those with long-standing renal impairment[2,33]. Tophi are a common manifestation of gout, but spinal manifestations are considered rare. Recent research by de Mello et al[1], however, suggests that tophi in the axial skeleton may be more prevalent than first suspected.

Although no studies have been able to conclude the exact mechanism for axial involvement in gout, the likely theory is, as gout usually involves joint spaces, facet joint may be the initial deposition location for MSU crystals. Another theory is based on the fact that high uric acid and other inflammatory markers are often elevated in gout. This increase in uric acid in the blood could signal a corresponding increase in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leading to the obstruction of the canal or foramen.

Literature review showed that the lumbar spine was the most commonly involved region followed by thoracic and cervical regions. The most common clinical presentation was back pain associated with lumbar radiculopathy, or neurogenic claudication. The most frequent laboratory finding was hyperuricemia defined as uric acid above 7 mg/dL. Renal insufficiency was also found in many patients. Plain radiograph findings are usually non-specific. The most consistent image findings of the intraspinal extradural tophi were hypointense signal on the T1-weighted MRI and heterointense signals on the T2-weighted MRI. Spinal gout is usually diagnosed with cytological or histopathological studies. However, for patients treated with surgery, a pasty chalk-white mass are usually present. Clinical presentations and radiological findings of spinal gout are often non-specific and one has to consider the differential diagnoses of intraspinal extradural mass. The most frequent etiology with similar clinical presentations and imaging findings is herniated disc. Other causes include synovial cyst, tumor, epidural abscess, arteriovenous malformation.

Pharmacotherapy for spinal gout is the same as those used for gout involving typical joints. Acute gouty attack is most often treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as, naproxen or indomethacin. In patients with chronic kidney disease, duodenal or gastric ulcer, heart disease or hypertension, NSAID allergy, or anticoagulant treatment, colchicine is an alternative treatment. While NSAIDs and colchicine are effective in symptomatic reduction during an acute attack, they do not prevent the development of bony erosions or tophi deposits in tissues. To prevent further gouty attack, maintenance medications are often prescribed with the goal of keeping uric acid level less than 6 mg/dL. Xanthine oxidase inhibitors, such as allopurinol, febuxostat, and oxypurinol, are the first line choices for reduced production of uric acid. Allopurinol can precipitate gouty attack or worsen current attack, thus, it is used for maintenance after acute attack has resolved. Uricosuric agents, such as, probenecid and sulfinpyrazone, are second line prophylactics aimed to increase uric acid excretion since decreased uric acid excretion is responsible for 85% to 90% of primary or secondary hyperuricemia[58].

Surgical interventions may be needed if patient has symptoms of spinal cord or nerve root compression. The mainstay of surgical treatment is decompression and excision of the tophi. The role of fusion at the time of the decompression remains controversial. The need for fusion is influenced by symptomatic preoperative instability as evidenced by dynamic radiographs, erosion of the facet joint seen on CT scan, or intraoperative instability that may be created by iatrogenic resection of spinal structures such as the pars interarticularis or the facet joints.

Although this article provides a broad overview of cases involving spinal gout since January 2000, there are some limitations. The absence of certain information, such as the post-treatment outcomes, limited the depth of our analysis in certain cases. Furthermore, the literature review could not always account for individual variation among the 68 cases reviewed including the particular method of diagnosis, which was not standardized across all patients included in the study. In addition, the individual articles did not provide information regarding prior uric acid lowering treatments, which could possibly inflate the number of spinal gout cases with normal uric acid levels.

The majority of clinical features for spinal gout such as back pain and neurological symptoms are nonspecific. Thus, one must rule out other common diagnoses, such as disc herniation, tumor, infection prior to diagnosing a patient with spinal gout. Laboratory study indicative of gout is elevated uric acid levels. In this literature review, the majority of the cases utilized MRI as the radiological study of choice in detecting spinal gout. While MRI was the major non-invasive diagnostic method, all suspicious findings on imaging required surgical sampling for pathological confirmation of negatively birefringent MSU crystals presence.

COMMENTS

Background

Gout is a common inflammatory arthritis with an increase in prevalence over the last 20 years. It currently affects over 8 million Americans. The primary aim of this review is to summarize the most common presenting features, imaging findings, and treatment choices based on the 68 published cases.

Research frontiers

Literature review showed that the lumbar spine was the most commonly involved region followed by thoracic and cervical regions. The most common clinical presentation was back pain associated with lumbar radiculopathy, or neurogenic claudication. The most frequent laboratory finding was hyperuricemia defined as uric acid above 7 mg/dL.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Traditionally gout thought of as a rare problem characterized by a sudden, severe attacks of pain, redness and tenderness in joints, often the joint at the base of the big toe. Recent studies suggest that axial gout may be more prevalent than suspected. Spinal gout can affect the facet joint, laminae, ligamentum flavum, as well as the epidural spaces.

Applications

The majority of clinical features for spinal gout such as back pain and neurological symptoms are nonspecific. Suspicious findings on MRI imaging required surgical sampling for pathological confirmation of negatively birefringent monosodium urate crystals presence.

Peer-review

It is a good review concerning the spinal gout consisting of the symptom and signs, treatment option and lab data analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: None of the authors have any financial or other conflicts of interest that may bias the current study.

Data sharing statement: The technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset are available from the corresponding author at hossein.elgafy@utoledo.edu.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: April 28, 2016

First decision: July 6, 2016

Article in press: August 18, 2016

P- Reviewer: Hammoudeh M, Pan HC S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.de Mello FM, Helito PV, Bordalo-Rodrigues M, Fuller R, Halpern AS. Axial gout is frequently associated with the presence of current tophi, although not with spinal symptoms. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39:E1531–E1536. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Federman DG, Kravetz JD, Luciano RL, Brown JE. Gout: what a pain in the neck. Conn Med. 2012;76:143–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakamoto FA, Winalski CS, Rodrigues LC, Fernandes AR, Bortoletto A, Sundaram M. Radiologic case study. Orthopedics. 2012;35:353–437. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120426-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasturk AE, Basmaci M, Canbay S, Vural C, Erten F. Spinal gout tophus: a very rare cause of radiculopathy. Eur Spine J. 2012;21 Suppl 4:S400–S403. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1847-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kao MC, Huang SC, Chiu CT, Yao YT. Thoracic cord compression due to gout: a case report and literature review. J Formos Med Assoc. 2000;99:572–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mekelburg K, Rahimi AR. Gouty arthritis of the spine: clinical presentation and effective treatments. Geriatrics. 2000;55:71–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paquette S, Lach B, Guiot B. Lumbar radiculopathy secondary to gouty tophi in the filum terminale in a patient without systemic gout: case report. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:986–988. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200004000-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thornton FJ, Torreggiani WC, Brennan P. Tophaceous gout of the lumbar spine in a renal transplant patient: a case report and literature review. Eur J Radiol. 2000;36:123–125. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(00)00214-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrett K, Miller ML, Wilson JT. Tophaceous gout of the spine mimicking epidural infection: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:1170–1172. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200105000-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.St George E, Hillier CE, Hatfield R. Spinal cord compression: an unusual neurological complication of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:711–712. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang LC, Hung YC, Lee EJ, Chen HH. Acute paraplegia in a patient with spinal tophi: a case report. J Formos Med Assoc. 2001;100:205–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu CY, Shih TT, Huang KM, Chen PQ, Sheu JJ, Li YW. Tophaceous gout of the spine: MR imaging features. Clin Radiol. 2002;57:919–925. doi: 10.1053/crad.2001.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Souza AW, Fontenele S, Carrete H, Fernandes AR, Ferrari AJ. Involvement of the thoracic spine in tophaceous gout. A case report. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20:228–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yen HL, Cheng CH, Lin JW. Cervical myelopathy due to gouty tophi in the intervertebral disc space. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144:205–207. doi: 10.1007/s007010200026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz A, Porhiel V, Sabatier P, Taha S, Ragragui O, Comoy J, Leriche B. [Tophaceous gout of the cervical spine, causing cord compression. Case report and review of the literature] Neurochirurgie. 2003;49:600–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Draganescu M, Leventhal LJ. Spinal gout: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Rheumatol. 2004;10:74–79. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000120898.82192.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Sandid M, Ta H. Another presentation of gout. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:W32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00037-w2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakajima A, Kato Y, Yamanaka H, Ito T, Kamatani N. Spinal tophaceous gout mimicking a spinal tumor. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1459–1460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beier CP, Hartmann A, Woertgen C, Brawanski A, Rothoerl RD. A large, erosive intraspinal and paravertebral gout tophus. Case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:485–487. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.3.6.0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Celik SE, Görgülü M. Tophaceous gout of the atlantoaxial joint. Case illustration. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:230. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.2.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang IC. Surgical versus pharmacologic treatment of intraspinal gout. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(433):106–110. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000151456.52270.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly J, Lim C, Kamel M, Keohane C, O’Sullivan M. Topacheous gout as a rare cause of spinal stenosis in the lumbar region. Case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:215–217. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.2.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahmud T, Basu D, Dyson PH. Crystal arthropathy of the lumbar spine: a series of six cases and a review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:513–517. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B4.15555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wazir NN, Moorthy V, Amalourde A, Lim HH. Tophaceous gout causing atlanto-axial subluxation mimicking rheumatoid arthritis: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2005;13:203–206. doi: 10.1177/230949900501300220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yen PS, Lin JF, Chen SY, Lin SZ. Tophaceous gout of the lumbar spine mimicking infectious spondylodiscitis and epidural abscess: MR imaging findings. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12:44–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dharmadhikari R, Dildey P, Hide IG. A rare cause of spinal cord compression: imaging appearances of gout of the cervical spine. Skeletal Radiol. 2006;35:942–945. doi: 10.1007/s00256-006-0088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hou LC, Hsu AR, Veeravagu A, Boakye M. Spinal gout in a renal transplant patient: a case report and literature review. Surg Neurol. 2007;67:65–73; discussion 73. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2006.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oaks J, Quarfordt SD, Metcalfe JK. MR features of vertebral tophaceous gout. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W658–W659. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pankhania AC, Patankar T, Du Plessis D. Neck pain: an unusual presentation of a common disease. Br J Radiol. 2006;79:537–539. doi: 10.1259/bjr/28763793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popovich T, Carpenter JS, Rai AT, Carson LV, Williams HJ, Marano GD. Spinal cord compression by tophaceous gout with fluorodeoxyglucose-positron-emission tomographic/MR fusion imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:1201–1203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adenwalla HN, Usman MH, Baqir M, Zulqarnain M, Shah H. Vertebral gout and ambulatory dysfunction. South Med J. 2007;100:413–414. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3180374de1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lam HY, Cheung KY, Law SW, Fung KY. Crystal arthropathy of the lumbar spine: a report of 4 cases. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2007;15:94–101. doi: 10.1177/230949900701500122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suk KS, Kim KT, Lee SH, Park SW, Park YK. Tophaceous gout of the lumbar spine mimicking pyogenic discitis. Spine J. 2007;7:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fontenot A, Harris P, Macasa A, Menon Y, Quinet R. An initial presentation of polyarticular gout with spinal involvement. J Clin Rheumatol. 2008;14:188–189. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e318177a6b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan AT, Leung JL, Sy AN, Wong WW, Lau KY, Ngai WT, Tang VW. Thoracic spinal gout mimicking metastasis. Hong Kong Med J. 2009;15:143–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nygaard HB, Shenoi S, Shukla S. Lower back pain caused by tophaceous gout of the spine. Neurology. 2009;73:404. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b04cb1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai CH, Chen YJ, Hsu HC, Chen HT. Bacteremia coexisting with tophaceous gout of the spine mimicking spondylodiscitis: a case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:E106–E109. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818d051a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coulier B, Tancredi MH. Articular tophaceous gout of the cervical spine: CT diagnosis. JBR-BTR. 2010;93:325. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ko KH, Huang GS, Chang WC. Tophaceous gout of the lumbar spine. J Clin Rheumatol. 2010;16:200. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181c51ea9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy DJ, Shearman AL, Mascarenhas R, Haigh RC. Lucent lesions of the spine--a case of spinal gout. Age Ageing. 2010;39:660. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ntsiba H, Makosso E, Moyikoua A. Thoracic spinal cord compression by a tophus. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:187–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samuels J, Keenan RT, Yu R, Pillinger MH, Bescke T. Erosive spinal tophus in a patient with gout and back pain. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2010;68:147–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ibrahim GM, Ebinu JO, Rubin LA, de Tilly LN, Spears J. Gouty arthropathy of the axial skeleton causing cord compression and myelopathy. Can J Neurol Sci. 2011;38:918–920. doi: 10.1017/s031716710001252x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levin E, Hurth K, Joshi R, Brasington R. Acute presentation of tophaceous myelopathy. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1525–1526. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thavarajah D, Hussain R, Martin JL. Cervical arthropathy caused by gout: stabilisation without decompression. Eur Spine J. 2011;20 Suppl 2:S231–S234. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1604-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tran A, Prentice D, Chan M. Tophaceous gout of the odontoid process causing glossopharyngeal, vagus, and hypoglossal nerve palsies. Int J Rheum Dis. 2011;14:105–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2010.01565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamamoto M, Tabeya T, Masaki Y, Suzuki C, Naishiro Y, Ishigami K, Yajima H, Shimizu Y, Obara M, Yamamoto H, et al. Tophaceous gout in the cervical spine. Intern Med. 2012;51:325–328. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.6262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu F, Jiang J, Zhang F, Xia X, Wang L, Ma X. Lumbar spinal stenosis induced by rare chronic tophaceous gout in a 29-year-old man. Orthopedics. 2012;35:e1571–e1575. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120919-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanmillan Blasco JL, Vidal Sarro N, Marnov A, Acebes Martín JJ. Cervical cord compression due to intradiscal gouty tophus: brief report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:E1534–E1536. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31826f2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wendling D, Prati C, Hoen B, Godard J, Vidon C, Godfrin-Valnet M, Guillot X. When gout involves the spine: five patients including two inaugural cases. Joint Bone Spine. 2013;80:656–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Komarla A, Schumacher R, Merkel PA. Spinal gout presenting as acute low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2660. doi: 10.1002/art.38069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Parisot A, Ltaief-Boudrigua A, Villani AP, Barrey C, Chapurlat RD, Confavreux CB. Spontaneous odontoid fracture on a tophus responsible for spinal cord compression: a case report. Joint Bone Spine. 2013;80:550–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwan BY, Osman S, Barra L. Spinal gout in a young patient with involvement of thoracic, lumbar and sacroiliac regions. Joint Bone Spine. 2013;80:667–668. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoon JW, Park KB, Park H, Kang DH, Lee CH, Hwang SH, Jung JM, Han JW, Park IS. Tophaceous gout of the spine causing neural compression. Korean J Spine. 2013;10:185–188. doi: 10.14245/kjs.2013.10.3.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jegapragasan M, Calniquer A, Hwang WD, Nguyen QT, Child Z. A case of tophaceous gout in the lumbar spine: a review of the literature and treatment recommendations. Evid Based Spine Care J. 2014;5:52–56. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1366979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cardoso FN, Omoumi P, Wieers G, Maldague B, Malghem J, Lecouvet FE, Vande Berg BC. Spinal and sacroiliac gouty arthritis: report of a case and review of the literature. Acta Radiol Short Rep. 2014;3:2047981614549269. doi: 10.1177/2047981614549269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hasegawa EM, de Mello FM, Goldenstein-Schainberg C, Fuller R. Gout in the spine. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2013;53:296–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bull PW, Scott JT. Intermittent control of hyperuricemia in the treatment of gout. J Rheumatol. 1989;16:1246–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]