Abstract

Advanced atherosclerotic lesions contain senescent cells, but the role of these cells in atherogenesis remains unclear. Using transgenic and pharmacological approaches to eliminate senescent cells in atherosclerosis-prone low-density lipoprotein receptor–deficient (Ldlr−/−) mice, we show that these cells are detrimental throughout disease pathogenesis. We find that foamy macrophages with senescence markers accumulate in the subendothelial space at the onset of atherosclerosis, where they drive pathology by increasing expression of key atherogenic and inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. In advanced lesions, senescent cells promote features of plaque instability, including elastic fiber degradation and fibrous cap thinning, by heightening metalloprotease production. Together, these results demonstrate that senescent cells are key drivers of atheroma formation and maturation and suggest that selective clearance of these cells by senolytic agents holds promise for the treatment of atherosclerosis.

Atherosclerosis initiates when oxidized lipoprotein infiltrates the subendothelial space of arteries, often due to aberrantly elevated levels of apolipoprotein B–containing lipoproteins in the blood (1). Chemotactic signals arising from activated endothelium and vascular smooth muscle attract circulating monocytes that develop into lipid-loaded foamy macrophages, a subset of which adopt a proinflammatory phenotype through a mechanism that is not fully understood. The proinflammatory signals lead to additional rounds of monocyte recruitment and accumulation of other inflammatory cells (including T and B cells, dendritic cells, and mast cells), allowing initial lesions, often termed “fatty streaks,” to increase in size and develop into plaques (2). Plaque stability, rather than absolute size, determines whether atherosclerosis is clinically silent or pathogenic because unstable plaques can rupture and produce vessel-occluding thrombosis and end-organ damage. Stable plaques have a relatively thick fibrous cap, which largely consists of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and extracellular matrix components, partitioning soluble clotting factors in the blood from thrombogenic molecules in the plaque (3). In advanced disease, plaques destabilize when elevated local matrix metalloprotease production degrades the fibrous cap, increasing the risk of lesion rupture and subsequent thrombosis.

Advanced plaques contain cells with markers of senescence, a stress response that entails a permanent growth arrest coupled to the robust secretion of numerous biologically active molecules and is referred to as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). The senescence markers include elevated senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA β-Gal) activity and p16Ink4a, p53, and p21 expression (4, 5). However, whether and how senescent cells contribute to atherogenesis remains unclear (6, 7). Human plaques contain cells with shortened telomeres, which predispose cells to undergo senescence (8). Consistent with a proatherogenic role of senescence is the observation that expression of a loss-of-function telomere-binding protein (Trf2) in VSMCs accelerates plaque growth in the ApoE−/− mouse model of atherosclerosis, although in vivo evidence for increased senescence in plaques was not provided. On the other hand, mice lacking core components of senescence pathways, such as p53, p21, or p19Arf (7, 9–11), show accelerated atherosclerosis, implying a protective role for senescence. Studies showing that human and mouse polymorphisms that reduce expression of p16Ink4a and p14Arf (p19Arf in mice) correlate with increased atheroma risk support this conclusion (7, 12, 13). Thus, whether senescent cells accelerate or retard atherogenesis is unclear.

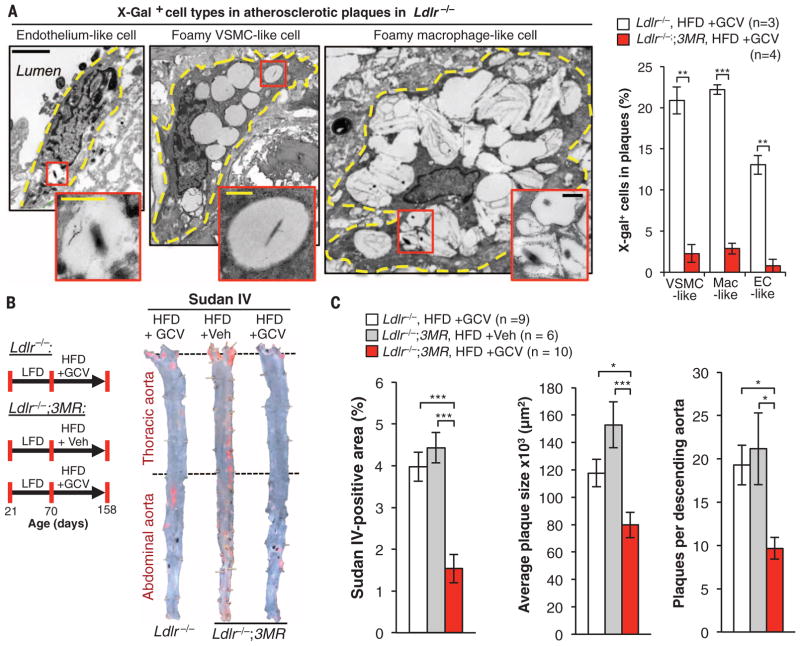

We used genetic and pharmacological methods of eliminating senescent cells to examine the role of naturally occurring senescent cells at different stages of atherogenesis. First, we verified that senescent cells accumulate in low-density lipoprotein receptor–deficient (Ldlr−/−) mice, a model of atherogenesis. We fed 10-week-old Ldlr−/− mice a high-fat diet (HFD) for 88 days. We then performed SA β-Gal staining, which revealed that senescent cells are present in atherosclerotic lesions but not in the normal adjacent vasculature or aortas of Ldlr−/− mice fed a low-fat diet (LFD) (fig. S1A). In addition, plaque-rich aortic arches had elevated transcript levels of p16Ink4a, p19Arf, and various canonical SASP components, including the matrix metalloproteases Mmp3 and Mmp13 and the inflammatory cytokines Il1α and Tnfα (fig. S1B). To eliminate senescent cells from plaques, we used p16-3MR (3MR) mice (14), a transgenic model that expresses the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase under the control of the p16Ink4a gene promoter and kills p16Ink4a+ senescent cells upon administration of ganciclovir (GCV). Plaques of Ldlr−/−;3MR mice fed a HFD for 88 days and then treated short term with GCV had low levels of SA β-Gal activity compared with Ldlr−/− mice (fig. S1C), indicating efficient clearance of senescent cells. Examination of the plaques by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed that three morphologically distinct cell types—elongated, vacuolated cells located in the endothelial layer; spindly foam cells with histological properties of VSMCs; and large foamy cells resembling lipid-loaded macrophages—produced X-galactosidase (X-Gal) crystals (Fig. 1A). We refer to these cells as endothelial-like, foamy VSMC–like, and foamy macrophage–like cells, respectively, because cells within plaques change shape and lineage markers, precluding accurate assessment of cell origin (15, 16). All three senescent cell types were efficiently eliminated by treatment with GCV (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. p16Ink4a+ senescent cells drive formation of atherosclerotic plaques.

(A) (Left) X-Gal electron microscopy images showing three types of senescent cells in plaques of Ldlr−/− mice on a HFD for 88 days. Cell outlines are traced by dashed yellow lines. Endothelial-like cells are elongated and adjacent to the lumen. VSMC-like cells are elongated spindle-shaped cells or irregularly shaped ramified cells. Macrophage-like cells are highly vacuolated circular cells. (Right) Senescent cell quantification in plaques. Mac, macrophage; EC, endothelial cell. (B) (Left) Experimental design for testing the effect of senescent cell clearance on atherogenesis. Veh, Vehicle. (Right) Sudan IV–stained descending aortas (not including the aortic arch). (C) Quantification of total descending aorta plaque burden, number, and lesion size. Scale bars: 2 μm (A); 500 nm [(A), insets]. Data represent mean ± SEM (error bars) [biological n is indicated on graphs and refers to individual plaques in (A) (one per mouse) and aortas in (C)]. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (unpaired two-tailed t tests with Welch’s correction).

To assess the impact senescent cells have on plaque development, we placed 10-week-old Ldlr−/−;3MR mice on a HFD for 88 days and simultaneously treated them with GCV or vehicle during this period (Fig. 1B) to intermittently remove p16Ink4a+ cells. To control for potential effects of GCV, independent of 3MR expression, we also examined GCV-treated Ldlr−/− mice on a HFD. En face staining of descending aortas with Sudan IV revealed that plaque burden was ~60% lower in GCV-treated Ldlr−/−;3MR mice than in vehicle-treated Ldlr−/−;3MR or GCV-treated Ldlr−/− mice, owing to decreases in both plaque number and size (Fig. 1C). Similarly, GCV-treated Ldlr−/−;3MR mice showed reduced plaque burden and destruction of aortic elastic fibers beneath the neointima in the brachiocephalic artery (fig. S2, A to C), a site that rapidly develops advanced atherosclerotic plaques (17). Compared with vehicle-treated Ldlr−/−;3MR mice, GCV-treated Ldlr−/−;3MR mice expressed lower amounts of p16Ink4a mRNA and other senescence-marker mRNAs in aortic arches, confirming that p16Ink4a+ senescent cells were efficiently cleared by GCV (fig. S3A). Expression of 3MR, as measured by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis of monomeric red fluorescent protein transcripts, increased in HFD-fed mice but remained at baseline levels with GCV treatment. Complementary en face SA β-Gal staining of aortas confirmed that p16Ink4a+ senescent cells were effectively cleared (fig. S3B). GCV-treatment of Ldlr−/− mice did not alter SA β-Gal staining or other senescence markers (fig. S3, B and C). GCV-treated Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−;3MR mice did not differ in body weight, fat mass, and fat deposit weight (fig. S4, A to D). Circulating monocytes, lymphocytes, platelets, and neutrophils, all of which are involved in atherogenesis, were unaffected (fig. S4, E to H). Levels of atherogenic lipids in the blood of GCV-treated Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−;3MR mice and vehicle-treated Ldlr−/−;3MR mice were highly elevated compared with levels in LFD-fed controls, with no differences between the distinct HFD-fed cohorts (fig. S4I). Thus, the atheroprotective effect in GCV-treated Ldlr−/−;3MR mice is due to the killing of p16Ink4a+ senescent cells rather than changes in feeding habits, blood lipids, or circulating immunocytes. Reductions in plaque burden, number, and size observed with p16-3MR were reproducible with two independent transgenic systems [INK-ATTAC (fig. S5) (18, 19) and INK-Nitroreductase (NTR) (fig. S6)] designed to kill p16Ink4a+ senescent cells through distinct mechanisms, as well as with the senolytic drug ABT263, which inhibits the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL and selectively kills senescent cells (fig. S7) (20).

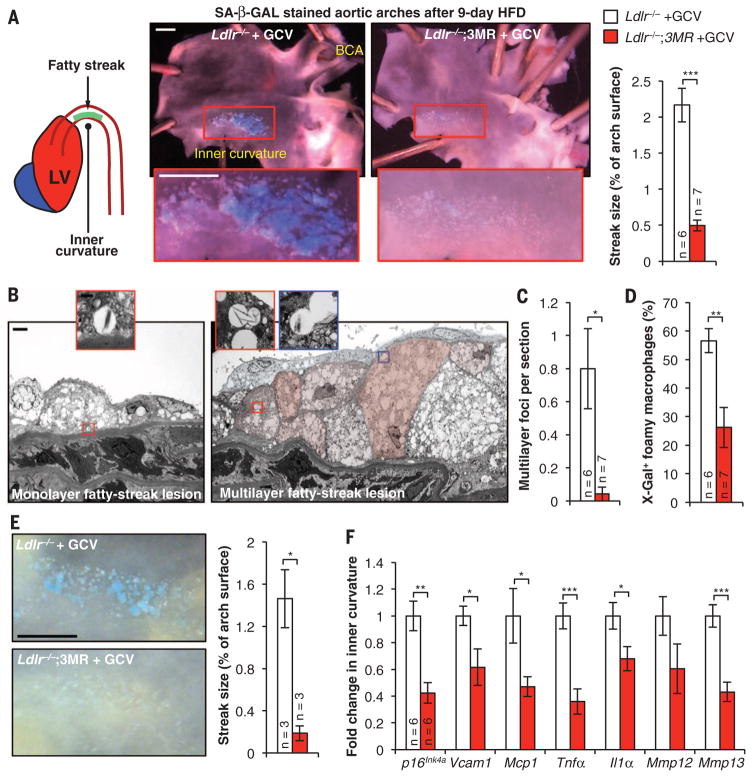

To investigate how senescent cells drive plaque initiation and growth, we focused on atherogenesis onset at lesion-prone sites of the vasculature (21). After just 9 days on an atherogenic diet, Ldlr−/− mice had overtly detectable fatty-streak lesions solely in the inner curvature of the aortic arch (Fig. 2A and fig. S8A). Surprisingly, these early lesions were highly positive for SA β-Gal activity (Fig. 2A). By contrast, Ldlr−/− mice containing 3MR and treated daily with GCV during the 9-day HFD-feeding period had low levels of SA β-Gal activity and much smaller fatty streaks (Fig. 2A). Histological examination by TEM of the SA β-Gal–stained samples revealed that fatty streaks of HFD-fed Ldlr−/− mice consisted of foci of foam cell macrophages arranged in mono- or multilayers (Fig. 2, B and C). The lesions had intact elastic fibers and no fibrous cap. X-Gal crystals were detectable exclusively in foam cell macrophages, irrespective of lesion size (Fig. 2, B and D). Foam cell macrophages in foci of 9-day lesions of Ldlr−/−;3MR mice receiving daily, high-dose GCV were rarely arranged in multilayers and had a much lower incidence of crystals (Fig. 2, C and D). Elevated SA β-Gal activity in fatty streaks correlated with increased levels of p16Ink4a and various other senescence markers, including Mmp3, Mmp13, Il1α, and Tnfα (fig. S8B). Nine-day treatment of HFD-fed Ldlr−/− mice with ABT263 confirmed that senolysis reduces atherogenesis onset (fig. S8C).

Fig. 2. Intimal senescent foamy macrophages form during early atherogenesis and foster production of proatherogenic factors.

(A) (Left) Schematic of the inner curvature of the aortic arch. LV, left ventricle. (Middle) Examples of SA β-Gal–stained 9-day fatty streaks with and without senescent cell clearance and quantification. (Right) Measurements of streak size. Treatment involved the administration of 25 mg/kg of GCV once daily. BCA, brachiocephalic artery. (B) TEM images of Ldlr−/− mice after 9-day HFD feeding, showing fatty-streak foci with X-Gal–positive foam cell macrophages (artificial coloring articulates cell boundaries in the multilayer). (C) Quantification of multilayer foci in day-9 fatty streaks with and without senescent cells. (D) Quantification of foam cell macrophages with X-Gal crystal–containing vesicles without and with clearance. (E) (Left) Representative SA β-Gal–stained 12-day fatty streaks without and with GCV treatment (25 mg/kg of GCV three times daily) for the last 3 days. (Right) Quantification of lesion burden. (F) RT-qPCR analysis of senescence marker expression in fatty streaks collected from Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−;3MR mice on a 12-day HFD and treated with GCV for the last 3 days. Scale bars: 1 mm (A) and (E); 2 μm (B); and 500 nm [(B), insets]. Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM (error bars) [biological n is indicated directly on all graphs and refers to individual aortic arches in (A) and (C) to (E) or dissected aortic arch inner curvatures in (F)]. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (unpaired two-tailed t tests with Welch’s correction).

To determine how senescent foamy macrophages contribute to early atherogenesis, we established 9-day fatty streaks in Ldlr−/− and Ldlr−/−;3MR mice and then administered high-dose GCV for 3 days while continuing to feed the mice a HFD. Short-term clearance of senescent cells markedly reduced streak size and SA β-Gal positivity (Fig. 2E). TEM images showed that cleared foci were drastically remodeled, with acellular debris retained in the subendothelium and few foamy macrophages containing X-Gal crystals (fig. S8, D and E). RT-qPCR revealed a stark reduction in p16Ink4a and SASP components (including Mmp3, Mmp13, Il1α, and Tnfα), as well as two key molecular drivers of monocyte recruitment (the chemokine Mcp1 and the leukocyte receptor Vcam1), whose expression is partly driven by Tnfα (Fig. 2F). These data suggest that subendothelial senescent foamy macrophages arising in early lesions enhance Tnfα-mediated Vcam1 expression, as well as the Mcp1 gradient, to perpetuate monocyte recruitment from the blood.

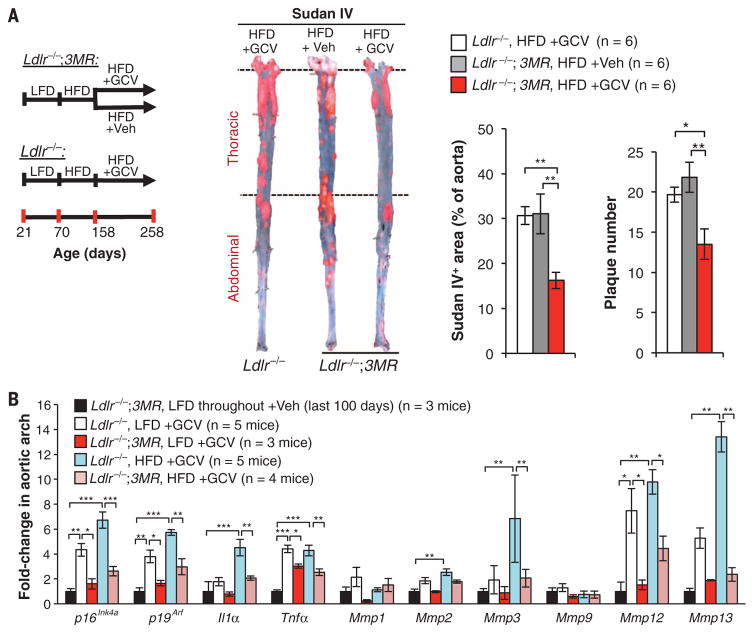

Next, we examined the role of senescent cells in the maturation of benign plaques to complex advanced lesions. Although mouse models for atherosclerosis do not develop clinical symptoms associated with plaque ruptures, plaque maturation in these mice can be studied using surrogate markers of plaque instability, including fibrous cap thinning (22, 23), decreased collagen deposition, elastic fiber degradation, and plaque calcification (24). To assess the effect of senescent cell clearance on the maturation of existing plaques, we employed late-disease senescent cell clearance protocols in which we placed Ldlr/− and Ldlr −/−;3MR mice on a HFD for 88 days to create plaques, followed by 100 days of GCV treatment. During GCV treatment, mice were fed a HFD or LFD to promote continued plaque advancement or stasis, respectively (Fig. 3A and fig. S9). Ldlr−/−;3MR mice maintained on the HFD and receiving GCV showed attenuated disease progression, as evidenced by a lower plaque number and size compared with GCV-treated Ldlr−/− or vehicle-treated Ldlr−/−;3MR controls (Fig. 3A). Whereas plaques of GCV-treated Ldlr−/−;3MR mice on a LFD had markedly reduced Sudan IV staining compared with plaques of control mice, the lesion-covered aortic area did not change (fig. S10A), even though 3MR-mediated senescent cell killing was confirmed by SA β-Gal staining (fig. S10B) and RT-qPCR for senescence markers (Fig. 3B). Regardless of diet, senescent cell clearance reduced expression of inflammatory cytokines (Fig. 3B) and monocyte recruitment factors (fig. S10C). GCV treatment decreased expression of matrix metalloproteases linked to plaque destabilization, including Mmp3, Mmp12, and Mmp13 (25, 26) (Fig. 3B), which suggests that senescent cell elimination stabilizes the fibrous cap.

Fig. 3. Removal of p16Ink4a+ cells in established plaques perturbs the proatherogenic microenvironment.

(A) (Left) Experimental design. (Middle) Sudan IV–stained descending aortas (not including the arch). (Right) Quantification of Sudan IV+ areas and plaque number. (B) RT-qPCR for senescence markers in aortic arches from indicated cohorts. Aortic arches from Ldlr−/−;3MR females fed a LFD until 258 days of age and treated with Veh for the last 100 days were used to assess baseline expression levels. Treatments in (A) and (B) involved daily injections of 5 mg/kg of GCV (or Veh) for 5 days, followed by 14 days off; this cycle was repeated for 100 days. Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM (error bars) [biological n is indicated directly on all graphs and refers to individual aortas in (A) or aortic arches in (B)]. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 [analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Sidak’s post-hoc correction for family-wise error in (A) and unpaired two-tailed t test with Welch’s correction in (B)].

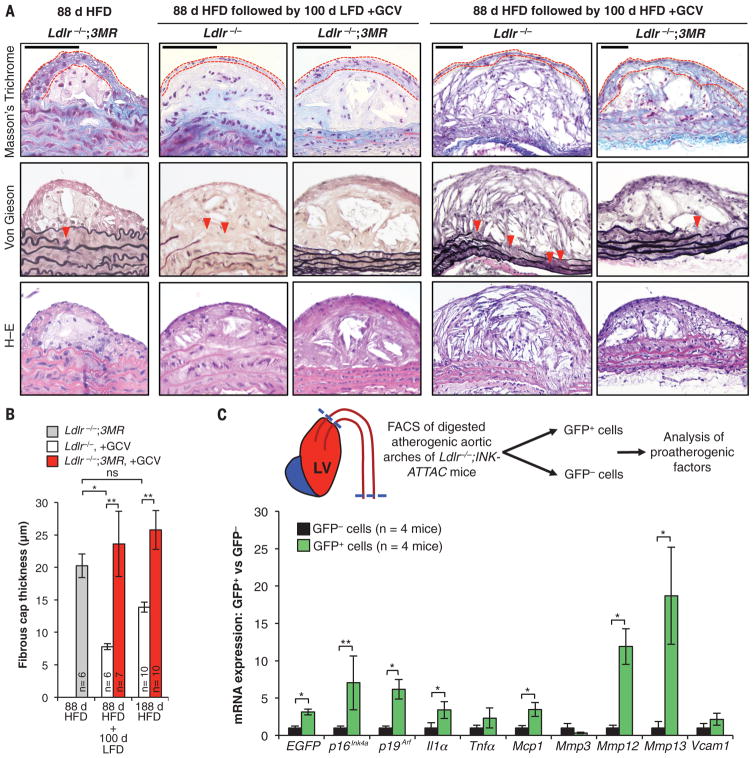

To investigate this and other features of plaque maturation, we conducted histopathology on plaques collected from the above cohorts. When Ldlr−/− mice originally fed a HFD for 88 days were left on the diet for an additional 100 days, their descending aorta plaques showed reduced cap thickness, diminished collagen content (by Masson’s trichrome staining), and more disrupted aortic elastic fibers (by Voerhoff von Gieson staining) in comparison with those of LFD-fed mice (Fig. 4, A and B, and fig. S11). In contrast, all of these markers of plaque instability were decreased with clearance of p16Ink4a+ cells, regardless of diet, during the 100-day GCV treatment period. Similarly, clearance of p16Ink4a+ cells increased cap thickness and collagen content in brachiocephalic arteries from mice reverted to LFD (fig. S12). We extended these studies by switching Ldlr−/−;3MR and Ldlr−/− mice after 88 days of HFD feeding to a LFD with GCV injections for 35 days (fig. S13A). In this experiment, senescent cell elimination preserved fibrous cap thickness (fig. S13, B and C). Furthermore, lesional foamy macrophage–like cell content was reduced, whereas VSMC-like cell content increased (fig. S13, D and E), resulting in plaques with a higher VSMC-like/macrophage-like cell ratio, a marker for greater stability (fig. S13F) (27). Clearance markedly reduced monocyte attachment to plaque-adjacent endothelium (fig. S13G), thus supporting our conclusion from early fatty-streak experiments that enhanced monocyte chemotaxis may partially explain the proatherogenic nature of senescent cells. These results strongly suggest that eliminating p16Ink4a+ cells promotes plaque stability.

Fig. 4. Senescent cells promote plaque instability by elevating metalloprotease production.

(A) Representative sections from descending aorta plaques of mice with the indicated genotypes, treatments, diets, and histological stainings. Red dashed lines trace the fibrous cap; red arrowheads indicate ruptured aortic elastic fibers. H–E, hematoxylin and eosin. (B) Quantification of fibrous cap thickness in plaques from (A). (C) (Top) Experimental overview. (Bottom) RT-qPCR analysis of senescence markers in GFP+ and GFP− cells. EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein. Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM (error bars) [biological n is indicated directly on all graphs and refers to individual descending aorta mouse plaques in (B) and flow-sorted cell fractions isolated from individual mice in (C)]. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns, not significant [ANOVA with Sidak’s post-hoc correction for familywise error in (B) and ratio paired t test in (C)].

To further investigate the mechanism by which senescent cells drive atherogenesis, we tested the possibility that senescent cells in plaques express proatherogenic factors. We dissected lesion-bearing tissue from HFD-fed Ldlr−/−; ATTAC mice, prepared single-cell suspensions, and exploited p16Ink4a-dependent expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) by ATTAC to collect GFP+ senescent and GFP− nonsenescent cell populations for analysis by RT-qPCR (Fig. 4C). Senescent cells expressed a broad spectrum of proatherogenic factors, including Il1α, Tnfα, Mmp3, Mmp12, Mmp13, Mcp1, and Vcam1 (Fig. 4C). A subset of these factors (including Il1α, Mmp12, Mmp13, and Mcp1) was expressed at markedly elevated levels compared with expression in nonsenescent cells.

Using both transgenic and pharmacological approaches to clear p16Ink4a+ cells without interfering with the senescence program, we showed that senescent cells are uniformly deleterious throughout atherogenesis. Very early fatty streaks contain abundant senescent foam cell macrophages, which create an environment conducive to further lesion growth by up-regulating inflammatory cytokines and monocyte chemotactic factors. Removal of p16Ink4a+ foamy macrophages from fatty streaks led to marked lesion regression. In contrast, advanced plaques contain three morphologically distinct senescent cell types that not only drive lesion maturation through inflammation and monocyte chemotaxis but also promote extracellular matrix degradation. Clearing senescent cells from advanced lesions inhibits both plaque growth and maladaptive plaque remodeling processes associated with plaque rupture, including fibrous cap thinning and elastic fiber degeneration. Furthermore, senescent cells in lesions show heightened expression of key SASP factors and effectors of inflammation, monocyte chemotaxis, and proteolysis, including Il1α, Mcp1, Mmp12, and Mmp13. These data suggest that senescent cells can directly influence core proatherogenic processes through specific secreted factors. By comparison, the expression of other factors such as Mmp3, Tnfα, and Vcam1 is reduced with senolysis, but these factors are not enriched in p16Ink4a+ cells, which implies that senescent cells also can influence the proatherogenic milieu indirectly. Collectively, our results show that senescent cells drive atherosclerosis at all stages through paracrine activity and raise the possibility that druglike molecules that remove senescent cells from patients without toxic side effects could contribute to therapeutic management of the disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R.-M. Laberge and M. Demaria for sharing data on the senolytic properties of ABT263, as well as N. David, Y. Poon, M. Hofker, B. van de Sluis, and the van Deursen lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported by a grant from the Paul F. Glenn Foundation (to J.M.v.D. and D.J.B.) and NIH grants R01CA96985 and CA168709 (to J.M.v.D.). J.M.v.D. and J.C. are cofounders of Unity Biotechnology, a company developing senolytic medicines including small molecules that selectively eliminate senescent cells. J.M.v.D., D.J.B., B.G.C., and J.C. are co-inventors on patent applications licensed to or filed by Unity Biotechnology. The p16-3MR mice are available from J.C. under a material transfer agreement. INK-ATTAC and INK-NTR mice are available from J.M.v.D. under a material transfer agreement.

Footnotes

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Tabas I, García-Cardeña G, Owens GK. J Cell Biol. 2015;209:13–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201412052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber C, Noels H. Nat Med. 2011;17:1410–1422. doi: 10.1038/nm.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakakura K, et al. Heart Lung Circ. 2013;22:399–411. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorenne I, Kavurma M, Scott S, Bennett M. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minamino T, et al. Circulation. 2002;105:1541–1544. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013836.85741.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang JC, Bennett M. Circ Res. 2012;111:245–259. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.261388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muñoz-Espín D, Serrano M. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:482–496. doi: 10.1038/nrm3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J, et al. Circulation. 2015;132:1909–1919. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khanna AK. J Biomed Sci. 2009;16:66. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mercer J, Figg N, Stoneman V, Braganza D, Bennett MR. Circ Res. 2005;96:667–674. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000161069.15577.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.González-Navarro H, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2258–2268. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wouters K, et al. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e32440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo CL, et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2483–2492. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.234492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demaria M, et al. Dev Cell. 2014;31:722–733. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feil S, et al. Circ Res. 2014;115:662–667. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shankman LS, et al. Nat Med. 2015;21:628–637. doi: 10.1038/nm.3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams H, Johnson JL, Carson KG, Jackson CL. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:788–792. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000014587.66321.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker DJ, et al. Nature. 2011;479:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker DJ, et al. Nature. 2016;530:184–189. doi: 10.1038/nature16932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang J, et al. Nat Med. 2016;22:78–83. doi: 10.1038/nm.4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakashima Y, Raines EW, Plump AS, Breslow JL, Ross R. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:842–851. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.5.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson JL, Jackson CL. Atherosclerosis. 2001;154:399–406. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00515-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarke MC, et al. Nat Med. 2006;12:1075–1080. doi: 10.1038/nm1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maldonado N, et al. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H619–H628. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00036.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silvestre-Roig C, et al. Circ Res. 2014;114:214–226. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghaderian SM, Akbarzadeh Najar R, Tabatabaei Panah AS. Coron Artery Dis. 2010;21:330–335. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e32833ce065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finn AV, Nakano M, Narula J, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1282–1292. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.