Abstract

Background:

Chronic respiratory diseases such as asthma, allergic rhinitis (AR), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and rhinosinusitis are becoming increasingly prevalent in the Asia-Pacific region. The Asia-Pacific Burden of Respiratory Diseases study examined the disease and economic burden of AR, asthma, COPD, and rhinosinusitis across the Asia-Pacific and more specifically India.

Objectives:

To estimate the proportion of adults receiving care for asthma, AR, COPD, and rhinosinusitis and assess the economic burden, both direct and indirect of these chronic respiratory disease.

Subjects and Methods:

Consecutive participants aged ≥18 years with a primary diagnosis of asthma, AR, COPD, or rhinosinusitis were enrolled. Surveys comprising questions about respiratory disease symptoms, healthcare resource utilization, work productivity, and activity impairment were completed by treating physicians and participants during one study visit. Costs, indirect and direct, that contributed to treatment for each of the four respiratory diseases were calculated.

Results:

A total of 1000 patients were enrolled. Asthma was the most frequent primary diagnosis followed by AR, COPD, and rhinosinusitis. A total of 335 (33.5%) patients were diagnosed with combinations of the four respiratory diseases; the most frequently diagnosed combinations were asthma/AR and rhinosinusitis/AR. Cough or coughing up sputum was the primary reason for the current visit by patients diagnosed with asthma and COPD while AR patients reported a watery, runny nose, and sneezing; patients with rhinosinusitis primarily reported a colored nasal discharge. The mean annual cost per patient was US$637 (SD 806). The most significant driver of direct costs was medications. The biggest cost component was productivity loss.

Conclusions:

Given the ongoing rapid urbanization of India, the frequency of respiratory diseases and their economic burden will continue to rise. Efforts are required to better understand the impact and devise strategies to appropriately allocate resources.

KEY WORDS: Economic cost, healthcare resource utilization, India, productivity, respiratory disease

INTRODUCTION

Asthma, allergic rhinitis (AR), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and rhinosinusitis are chronic diseases of the airways and other structures of the lungs. Chronic respiratory diseases account for 4% of the global and 8.3% of the overall burden of chronic diseases, having a major adverse impact on sufferers' quality of life (QoL), disability, and productivity, and resulting in increased economic burden for both the individual and community.[1] In recent years, the Asia-Pacific region has undergone a period of rapid growth, urbanization, and economic change. Recent studies have shown that the prevalence of asthma, allergic disorders, and COPD has increased, becoming a major health priority for the region.[2,3,4,5] Although the underlying reasons for this increase remain unclear, it is thought that environmental, population, genetic, and socioeconomic factors may play a significant role.[1]

There are limited data on the burden of respiratory disease in India. Two recent reviews report the prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma in adults in the Asia-Pacific region as varying from 0.7% in Korea to 32.8% in Australia; studies in India report prevalence from 2.05% to 3.5%.[6,7,8,9] Approximately 55% of all allergies seen in India are attributed to AR.[10] The estimated prevalence in adults for the Asia-Pacific region is between 10% and 32% although it is frequently underdiagnosed or mistreated.[5] COPD remains the third leading cause of mortality worldwide, responsible for 5.5% of deaths annually.[11] Rigorous estimates of the current prevalence of COPD in India are not well-understood due to the size and diversity of the Indian populations; however, data indicate that prevalence may vary from 3% to 8%.[12,13] The economic impact of respiratory disease in India remains largely unknown; however, 2011 estimates of the annual treatment cost of COPD is 350 billion rupees rising to 480 billion in 2016 using current treatment practice trends.[14] The annual treatment cost associated with asthma is estimated to be one-tenth of that of COPD.[15]

Understanding the socioeconomic burden on healthcare resources arising from these respiratory diseases is essential to identify effective interventions, plan priorities, and strategically allocate funds and resources to reduce the burden of these respiratory diseases in India. While several studies have addressed prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment of the above respiratory diseases in India, no studies to date have explored the burden of care in adults who present to healthcare professionals (HCP) using one standard protocol. As such, the present cross-sectional, observational study was conducted with the aim of estimating the proportion of adults receiving care for asthma, AR, COPD, and rhinosinusitis and assessing the economic burden, both direct and indirect of these chronic respiratory disease in India.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study design

This study formed part of the Asia-Pacific Burden of Respiratory Diseases study, a large multi-country, cross-sectional, observational study of adult patients receiving care for respiratory diseases across six countries in the Asia-Pacific region – India, Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand.[16,17] The study consisted of site-based surveys administered to patients presenting with a new or existing primary diagnosis of respiratory disease during a single visit. Respiratory diseases were considered as any conditions affecting the upper and lower airways.

Subjects were recruited from four sites in India between October 31, 2012, and October 13, 2013. Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committees at the National Allergy Asthma Bronchitis Institute, BYL. Nair Ch. Hospital and T. N. Medical College, St. John's Medical College and Dr. Paras Gangwal's Clinic.

Patients

Consecutive adult patients presenting to a healthcare provider during a routine consultation were assessed and screened for eligibility to participate in the study. Patients receiving care for a new or existing diagnosis of asthma, AR, COPD, and rhinosinusitis were considered eligible and provided with a written study description and informed consent form. Eligibility criteria included ≥18 years of age and receiving care for a new or existing diagnosis of asthma, AR, COPD, and/or rhinosinusitis. Patients were excluded if they had participated in an interventional clinical study within the last 12 weeks. A patient could only participate in the study once and no follow-up visits were recorded. Study information was provided prior to enrollment and informed consent was obtained for each. The patient's present medical management was not influenced by recruitment to the study.

Data collection

Physician and patient surveys were developed specifically to meet the objectives of the study as no suitable validated instruments existed for the four diseases of interest. The physician survey was non-interventional and comprised questions relating to the primary diagnosis of asthma, AR, COPD, or rhinosinusitis, reason for the patient's visit, new and existing diagnoses for the four diseases, family history of the four diseases, referrals to other medical services, medication use 4 weeks prior, and intended medication use after the study visit. For patients with a new diagnosis, physicians reported the clinical criteria used to make the diagnosis. The International Classification of Diseases-10 classifications were used in the diagnosis of respiratory disease.[18] This excluded some infectious and parasitic diseases that may affect the respiratory system (e.g., tuberculosis) and also excluded neoplasms of the respiratory system. The study relied on a diagnosis made by the attending physician using criteria based on international guidelines.[19,20,21,22] The physician was asked to indicate the clinical criteria used to make the diagnosis from a list of criteria for each disease adapted from international clinical practice guidelines for asthma, AR, COPD, and rhinosinusitis for patients who had a new diagnosis of any of the four diseases. Although the study was not intended to influence the patients' clinical management and physicians' usual diagnostic practices, some patients may have been diagnosed using a more standardized and rigorous approach than before commencement of the study. Attempts to independently verify or confirm the patient's diagnosis were not made.

Patient surveys were self-administered and included questions relating to demographics and disease history, respiratory symptoms, healthcare resource use, work productivity, and QoL. Validated surveys that assessed work productivity[23] and health-related QoL (HRQoL) included work productivity and activity impairment – specific health problem (WPAI-SHP), 12-item short form health survey version 2.0, and disease-specific HRQoL measures (i.e., Mini Asthma QoL Questionnaire, Mini Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire, Sino-Nasal Outcomes Test-20, COPD Assessment Test). The recall period for WPAI-SHP was 7 days. All study-related data were collected during the single study visit.

Costing analysis

To adopt a broad societal perspective, cost calculations were based on the direct costs (e.g., medical services or healthcare providers, medication use, patient-reported healthcare provider, and hospital visits), and indirect costs (e.g., lost productivity). As insurance companies and/or patients pay the majority of healthcare costs in India, government, insurance, and patient out-of-pocket cost estimates were used to conduct the cost analysis. Unit costs for healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) by practice type (e.g., general practitioners [GP] visit, specialist consultation, pharmacist visit, and hospitalization for respiratory patient) and primary diagnosis (asthma, AR, COPD, and rhinosinusitis) were collected. Average HCRU costs were calculated using the unit cost of the healthcare resource use item multiplied by reported healthcare resource use in the previous 4 weeks, plus the current visit to the GP or specialist. Local unit costs and assumptions were derived by local experts and affiliates.

The dosing and duration of medication use were based on international therapeutic guidelines. During the 4 weeks before the index consultation, patient medication use was collected for each medication class (e.g., antibiotic, inhaled anticholinergic, etc.). Medication costs were calculated using one representative medication from the most commonly prescribed medication for that respiratory disease and the general assumption was that patients would incur the cost of therapy over the full 28-day (4 weeks) period.

Work productivity was assessed using the WPAI-SHP questionnaire which measured the amount of absenteeism, presenteeism, overall work productivity lost, and daily activity impairment attributable to a specific health problem. The recall period for this questionnaire was 7 days and work productivity costs were only calculated on the proportion of participants who were reportedly employed during the study period. The value of lost productivity was assumed to be equal to the gross average monthly wage (estimated at INR 6399 from ILO Global Wage Database 2012), which were extrapolated to year 2014 values using linear regression. Lost productivity costs were calculated by multiplying the overall productivity lost from the WPAI questionnaire by the average monthly wage.

For all direct and indirect costs, the 4-week costs were multiplied by 13 to estimate the annual cost. The costs presented were calculated for the respiratory disease for which the patient had a primary diagnosis. Costs were presented in USD using the exchange rate for September 15, 2014 (1 USD = 61.0278 INR).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS® for Windows, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA). Descriptive analyses were conducted. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables or as a number (percentage) for categorical variables. The percentage and 95% confidence interval (CI) of patients with each disease were calculated using the exact (Clopper–Pearson) method.

RESULTS

Patient demographics

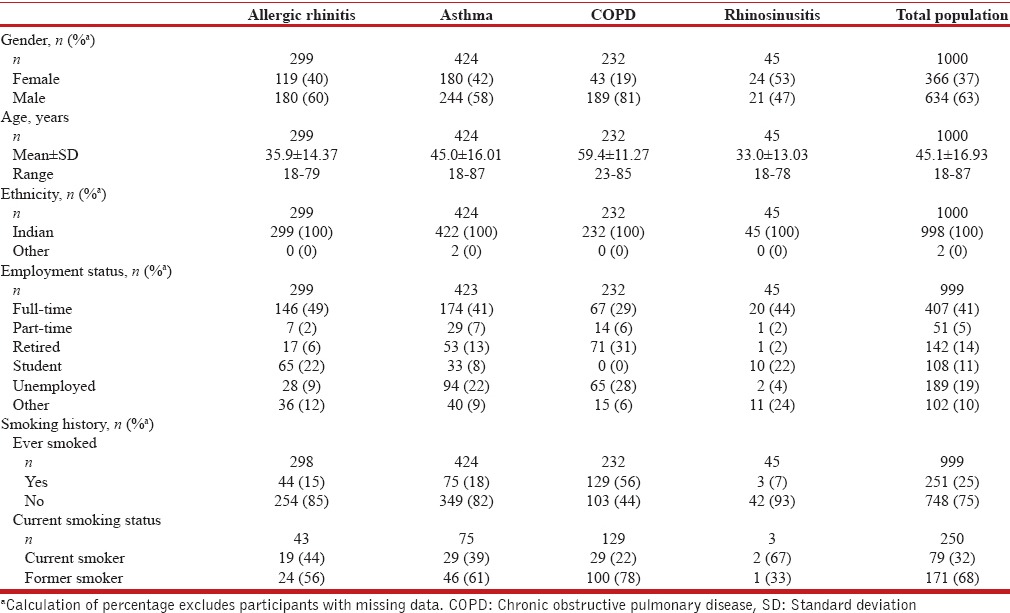

A total of 1337 patients across four study sites were diagnosed with a respiratory disease and screened for inclusion in the study. The total eligible patients presenting with a primary diagnosis of one of the four diseases was 1034 (77.3% of those screened), of which 1000 (96.7%) patients consented and enrolled in the study.

The patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean (SD) age of enrolled patients was 45.1 (SD 16.93) years and 63% were male. Forty-six percent of patients were in full- or part-time employment. Twenty-five percent of study patients reported ever smoking. About 32% (n = 79) of these patients were current smokers, with a primary diagnosis of AR (24%), asthma (37%), COPD (37%), and rhinosinusitis (3%).

Table 1.

Patient demographics by primary diagnosis for India

Frequency of respiratory disease

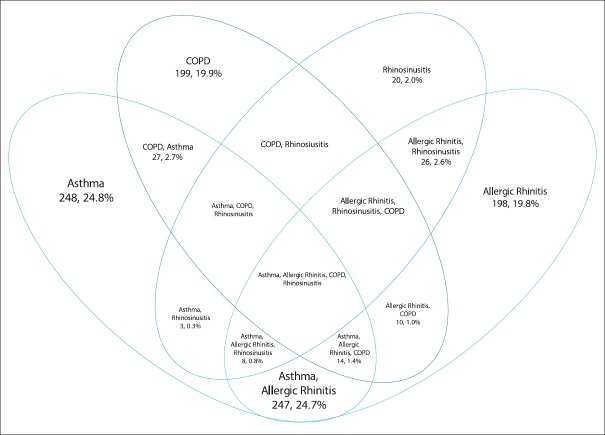

Asthma (42.4%, 95% CI: 39.3%, 45.5%) was the most frequent primary diagnosis among enrolled patients, followed by AR (29.9%, 95% CI: 27.1%, 32.8%), COPD (23.2%, 95% CI: 20.6%, 25.9%), and rhinosinusitis (4.5%, 95% CI: 3.3%, 6.0%). The study identified patients who presented with concomitant respiratory diseases as shown in Figure 1. About 33.5% (n = 335) of patients were diagnosed with various combinations of the four respiratory diseases; the majority (80.0%) of patients presented with a combination of asthma and AR, with or without other conditions. Of those patients presenting with a primary diagnosis of asthma (n = 424), 41.5% were diagnosed with a combination of respiratory diseases, including 165 (38.9%) patients with AR, with or without other conditions. For patients presenting with AR as the primary diagnosis (n = 299), 33.8% were diagnosed with more than one respiratory disease, of which 96 (32.1%) were diagnosed with asthma, with or without other conditions. COPD accounted for 23.2% (n = 232) of the primary diagnosis of patients, of which 14.2% were diagnosed with more than one disease, including asthma (11.2%) with or without other conditions. Rhinosinusitis was the least frequently diagnosed respiratory condition, with a primary diagnosis in 45 patients (4.5%). Of these patients, 55.6% were also diagnosed with AR.

Figure 1.

Percentage of enrolled patients (n = 1000) with a combination of diseases

Respiratory symptoms

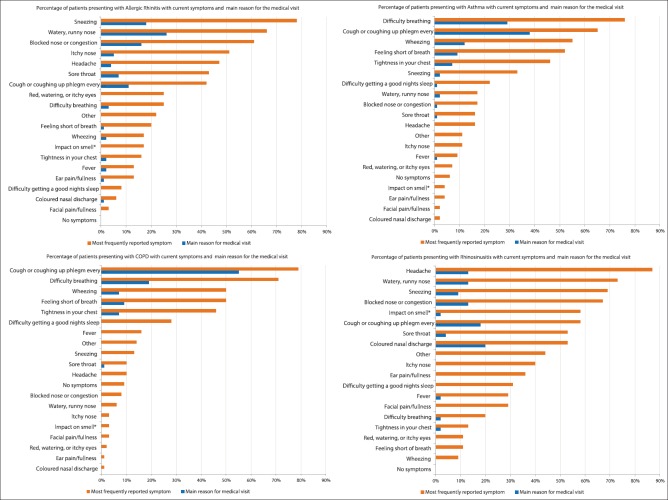

Patients were required to report the symptom that was the main reason for their current visit and list all their current symptoms and main reason for the current medical visit [Figure 2]. Cough or coughing up phlegm was the main reason for the current visit by patients who were diagnosed with asthma (38%) and COPD (55%), followed by difficulty in breathing (29% and 19%, respectively). For patients with a primary diagnosis of rhinosinusitis, the main reason for the current medical visit was colored nasal discharge (20%) followed by cough or coughing up sputum every day (18%). Patients with AR reported a watery, runny nose (26%), and sneezing (18%).

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients reporting current symptoms and main reason for the current medical visit by primary diagnosis (n = 951). *Loss of smell, reduced smell or foul smell

Healthcare resource utilization

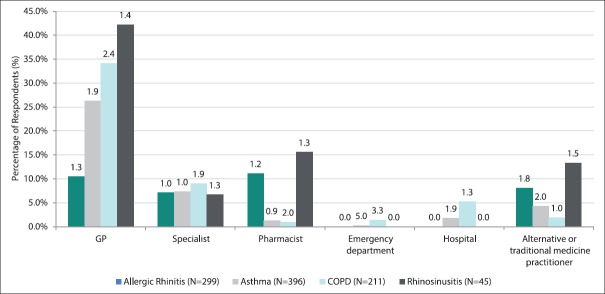

Patients reported their HCRU associated with their main respiratory symptom for the 4 weeks before the current medical visit [Figure 3]. GPs were the most frequently utilized healthcare resource by patients with a primary diagnosis of rhinosinusitis (42.2%), COPD (34.1%), and asthma (26.3%). Patients with AR reported more frequent utilization of the pharmacist (11.1%) than GP (10.4%) and patients with rhinosinusitis reported greater use of the pharmacist (15.6%) and alternative or traditional medicine practitioners (13.3%) than specialists (6.7%). Specialist visits were reported by <10% of patients across all four respiratory diseases. The use of the hospital or emergency department was minimal, reported predominantly in patients with COPD and asthma (5.2% and 1.4%, respectively).

Figure 3.

Percentage of patients with healthcare resource utilization in previous 4 weeks by primary diagnosis (n = 951)

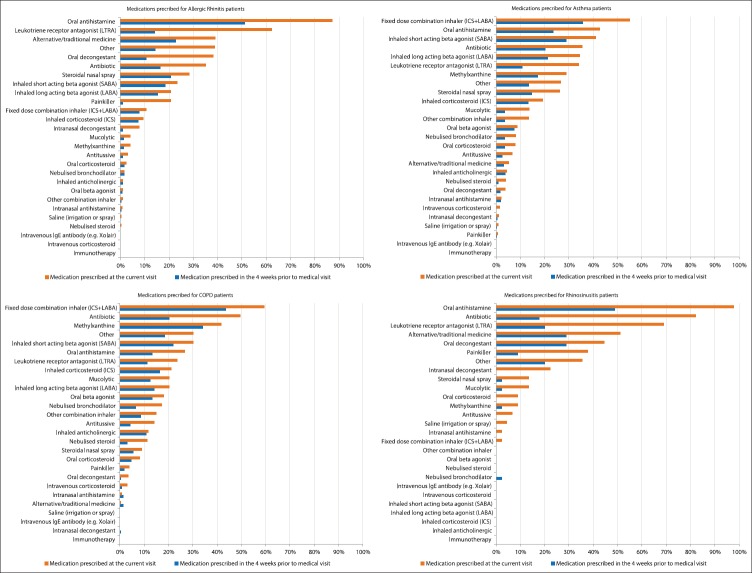

Study patients were asked about their history of medication use in the 4 weeks before the study visit [Figure 4]. Eighty percent of patients reported using medication for their respiratory disease in the previous 4 weeks. Prior medication use was highest among patients with a primary diagnosis of COPD (90.1%), followed by AR (78.6%), asthma (76.9%), and rhinosinusitis (66.7%). The use of oral antihistamines was greatest among patients with AR (51%) and rhinosinusitis (49%). Of interest was the use of alternative or traditional medicines among patients with AR (23%). Study patients with COPD and asthma reported the highest use of fixed-dose combination inhalers (44% and 36%, respectively).

Figure 4.

History of medication use in 4 weeks before medical visit and medication prescribed at the current medical visit by primary diagnosis (n = 1000)

Medications prescribed to study patients during the medical visit were recorded [Figure 4]. The main medications prescribed by the treating healthcare provider generally reflected patient medication use in the previous 4 weeks. Antibiotics were prescribed more frequently at the current visit than were used in the previous 4 weeks, with antibiotic prescribing highest in patients with a diagnosis of rhinosinusitis (82%), followed by COPD (50%). The prescribing of leukotriene receptor antagonists was more frequent in all diseases except COPD when compared to the medication use in the previous 4 weeks.

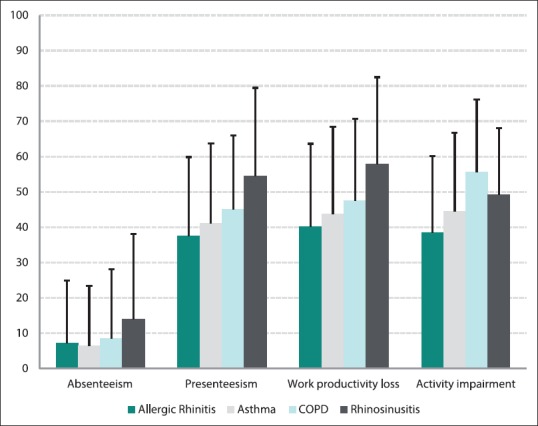

Work productivity and activity impairment

The WPAI questionnaire was completed by study patients and assessed the impact of the four respiratory diseases on activity impairment and work productivity loss [Figure 5]. Presenteeism (percentage impairment at work) when compared to reported absenteeism (percentage work time missed) was the biggest contributing factor to reported productivity loss. This was particularly evident in patients with rhinosinusitis where the impact on productivity loss (57.9%, SD 24.5) and activity impairment (49.1%, SD 18.9) was high when compared to asthma and AR. The impact of COPD on study patients was also evident in reported activity impairment (55.6%, SD 20.7) and work productivity loss (47.5%, SD 23.1).

Figure 5.

Mean percentage work productivity and activity impairment scores by primary diagnosis

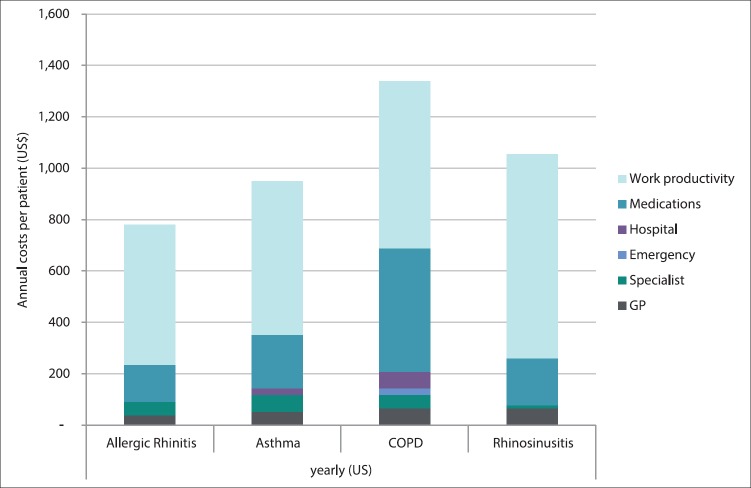

Costs

The annualized direct and indirect costs captured in the study by primary diagnosis are presented in Figure 6. The overall mean cost for patients with a respiratory disorder was US$637 (SD 806) per patient annually. For the working population, the most significant cost component attributed to all four diseases was productivity loss (62.2% of total costs) with a mean cost per patient of US$598 (SD 325). Rhinosinusitis sufferers followed by COPD incurred the highest loss of productivity cost with a mean of US$793 (SD 338) and US$650 (SD 312), respectively.

Figure 6.

Annual direct and indirect costs for study population by primary diagnosis (India)

The highest direct medical costs were in patients with a primary diagnosis of COPD (50% of direct costs), followed by asthma (36.7%), AR (29.6%), and rhinosinusitis (24.4%). Medication use was the main driver of these direct medical costs for patients with COPD (72.5% of direct costs), rhinosinusitis (69.6%), AR (61.1%), and asthma (59.5%) [Supplementary Table 1 (203.4KB, pdf) ]. Specialist and GP visits were the main drivers of nonmedication direct expenses [Supplementary Table 2 (143.4KB, pdf) ].

Cost of medications by primary diagnosis per month in INR and USD

Cost of healthcare resource use by primary diagnosis per month in INR and USD

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to report the burden of care in adults of the four respiratory diseases using one standard protocol. The results highlight both the economic and social impact of these respiratory disorders.

The most frequent primary diagnosis in this study was associated with asthma (42.4%), whose growing prevalence has been particularly pronounced in India due to increasing industrialization, rapid urbanization, and adoption of the western lifestyle.[24] Almost a third (29.9%) of study patients reported a primary diagnosis of AR, and although rhinosinusitis only accounted for a small percentage of respiratory conditions, its association with AR were common. COPD as primary diagnosis was attributed to almost a quarter (23.2%) of patients in this study, almost half that of asthma. This may be attributed to the severity of disease as many COPD patients may have been managed at a tertiary rather than primary level. It is also possible that COPD may have been under-diagnosed due to its progressive nature, which may have contributed to fewer cases seen in this study despite its higher prevalence. It was interesting to note that over half of COPD study participants had smoked, significantly higher than for other respiratory diseases, although fewer were current smokers than asthma and AR patients. Evidence of associations between smoking and asthma/COPD has been found although is not conclusive.[14,15]

Patients were frequently diagnosed with multiple respiratory conditions, which may be associated with greater morbidity and HCRU.[25] The high rate of comorbidity associated with asthma and AR is supported by several studies and is consistent with our findings, with 80% of enrolled patients with a primary diagnosis of asthma being diagnosed with AR with or without other conditions.[10,26,27] The reciprocal relationship was also evident, as 32.1% of patients with a primary diagnosis of AR were diagnosed asthma, however this was less than previously reported.[10]

The primary reason for the medical visit for COPD and asthma patients was due to symptoms of cough or coughing up sputum; this was also common in patients with a primary diagnosis of rhinosinusitis and to a lesser extent AR. Global healthcare expenditure related to the treatment of cough is estimated to be >$10 billion annually.[28] Healthcare resource utilization is substantial with estimates indicating patients with chronic cough account for 10–38% of respiratory outpatients and the average number of visits to a medical service >20 per patient.[29,30] Given the frequency of concomitant respiratory conditions reported in this study the presence of cough, particularly in AR and rhinosinusitis, may act as a key signaling symptom to prompt further investigation for more serious disorders such as COPD and asthma, and initiate early and appropriate treatment interventions.

This study provides new data on the economic cost of respiratory diseases in India. The socioeconomic burden arising from symptoms of respiratory diseases contributes directly to healthcare system costs and adding a significant burden on patients QoL, work performance, and daily activities.[27] The results demonstrated that lost work productivity is the most important indirect cost driver, accounting for the majority of expenditure in respiratory disease. Presenteeism was found to be a far bigger contributor to lost productivity than absenteeism. Factors such as loss of income, inability to care for family, and psychological factors have not been accounted for but may add significantly to the societal burden.

Medications were the most significant direct cost, reflecting the increased availability of effective medications and treatment options in India. Despite limited efficacy, there was high use of alternative medicine practitioners and medicines in patients with AR and rhinosinusitis, which may reflect lack of resources or access, cultural beliefs, or perceived lack of disease severity.[31,32] Understanding HCRU, particularly medication use, may assist in targeting the under or incorrect utilization of medicines and lead to the adoption of improved treatment practices and evidence-based strategies that are targeted, cost-effective, and lead to optimal health outcomes.

Certain study limitations were inevitable and should be considered when interpreting the results. Study participants may not be representative of the broader population with these respiratory diseases as it was not the intention of the study to measure prevalence estimates that are generalizable to the entire population, country, or region. Furthermore, the results may not be generalizable to either patients under 18 years of age or rural populations as only adult patients were recruited from urban centers. The method of diagnosing respiratory disease was not standardized. The patients' clinical management and physicians' usual diagnostic practices were not intended to be influenced by participation in the study; however, some patients may have been diagnosed using a more rigorous and standardized approach than may have occurred before commencement of the study. Patients were segregated by the experts in the field based on the patient's symptoms. No interventional or any other investigation was done to verify the diagnosis. The reported frequency in symptoms may have been influenced by factors such as age, smoking rate, and environment and seasonality which may have resulted in variations between diseases. The study did not aim to establish prevalence rather to provide a description of the extent of the four diseases of interest in patients presenting to primary and specialist HCPs with respiratory symptoms within a restricted period. The cost analysis provides only estimates of the average cost per patient and major cost drivers. Publicly available data or information provided by local experts or affiliates were used where available to estimate cost estimates; however, where this information was not available certain assumptions were adopted.

CONCLUSIONS

Given the ongoing rapid expansion, development, and urbanization of India, the frequency of respiratory diseases and the associated economic impact may continue to rise, resulting in an increasing burden on scarce healthcare resources. The findings contribute to efforts to better understand the socioeconomic impact of respiratory disease and the development of tailored strategies such as early diagnosis of respiratory disease and optimization of treatment, to ensure appropriate targeting and allocation of funds to minimize the impact of these diseases in India.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by Merck and Co.

Conflicts of interest

Kim K Hamrosi provided consulting services for the conduct of this research and manuscript preparation. Shalini Bagga and Shiva Sajjan are employees of Merck and Co., Rab Faruqi was an employee of Merck and Co., at the time of the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Surveillance, Prevention and Control of Chronic Respiratory Diseases: A Comprehensive Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong GW, Leung TF, Ko FW. Changing prevalence of allergic diseases in the Asia-Pacific region. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2013;5:251–7. doi: 10.4168/aair.2013.5.5.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wouters EF. Economic analysis of the confronting COPD survey: An overview of results. Respir Med. 2003;97(Suppl C):S3–14. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(03)80020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braman SS. The global burden of asthma. Chest. 2006;130(1 Suppl):4S–12S. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1_suppl.4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pawankar R, Bunnag C, Khaltaev N, Bousquet J. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma in Asia Pacific and the ARIA update 2008. World Allergy Organ J. 2012;5(Suppl 3):S212–7. doi: 10.1097/WOX.0b013e318201d831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song WJ, Kang MG, Chang YS, Cho SH. Epidemiology of adult asthma in Asia: Toward a better understanding. Asia Pac Allergy. 2014;4:75–85. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2014.4.2.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sembajwe G, Cifuentes M, Tak SW, Kriebel D, Gore R, Punnett L. National income, self-reported wheezing and asthma diagnosis from the World Health Survey. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:279–86. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00027509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aggarwal AN, Chaudhry K, Chhabra SK, D’Souza GA, Gupta D, Jindal SK, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for bronchial asthma in Indian adults: A multicentre study. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jindal SK, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D, Agarwal R, Kumar R, Kaur T, et al. Indian study on epidemiology of asthma, respiratory symptoms and chronic bronchitis in adults (INSEARCH) Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:1270–7. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deb A, Mukherjee S, Saha BK, Sarkar BS, Pal J, Pandey N, et al. Profile of patients with allergic rhinitis (AR): A clinic based cross-sectional study from Kolkata, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:67–70. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/6812.3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. The Top 10 Causes of Death. Fact Sheet No. 310 (Updated May 2014) 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKay AJ, Mahesh PA, Fordham JZ, Majeed A. Prevalence of COPD in India: A systematic review. Prim Care Respir J. 2012;21:313–21. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2012.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhome AB. COPD in India: Iceberg or volcano? J Thorac Dis. 2012;4:298–309. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.03.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murthy KJ, Sastry JG. Burden of disease in India: Economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. New Dehli, India: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murthy KJ, Sastry JG. Burden of disease in India: Economic burden of asthma. New Dehli, India: Ministry of Health & Welfare, Government of India; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho SH, Lin HC, Ghoshal AG, Bin Abdul Muttalif AR, Thanaviratananich S, Bagga S, et al. Respiratory disease in the Asia-Pacific region: Cough as a key symptom. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2016;37:131–40. doi: 10.2500/aap.2016.37.3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang DY, Ghoshal AG, Muttalif AR, Lin HC, Thanaviratananich S, Bagga S, et al. Quality of life and economic burden of respiratory disease in Asia-Pacific – Asia-Pacific burden of respiratory diseases (APBORD) study. Value Health. 2016;9:72–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, Denburg J, Fokkens WJ, Togias A, et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA (2) LEN and AllerGen) Allergy. 2008;63(Suppl 86):8–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fokkens W, Lund V, Mullol J. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps Group. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2007. Rhinol Suppl. 2007;20:1–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention 2011 (update) 2011. [Last accessed on 2015 Sep 09]. Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org/guidelines-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma.html .

- 22.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2010. [Last accessed on 2015 Sep 09]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-resources.html .

- 23.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353–65. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson PJ, Salvi S, Lin J, Cho YJ, Eng P, Abdul Manap R, et al. Insights, attitudes and perceptions about asthma and its treatment: Findings from a multinational survey of patients from 8 Asia-Pacific countries and Hong Kong. Respirology. 2013;18:957–67. doi: 10.1111/resp.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bousquet J, Gaugris S, Kocevar VS, Zhang Q, Yin DD, Polos PG, et al. Increased risk of asthma attacks and emergency visits among asthma patients with allergic rhinitis: A subgroup analysis of the improving asthma control trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:723–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin J, Su N, Liu G, Yin K, Zhou X, Shen H, et al. The impact of concomitant allergic rhinitis on asthma control: A cross-sectional nationwide survey in China. J Asthma. 2014;51:34–43. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2013.840789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meltzer EO, Blaiss MS, Naclerio RM, Stoloff SW, Derebery MJ, Nelson HS, et al. Burden of allergic rhinitis: Allergies in America, Latin America, and Asia-Pacific adult surveys. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012;33(Suppl 1):S113–41. doi: 10.2500/aap.2012.33.3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morice AH. Epidemiology of cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2002;15:253–9. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2002.0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai K, Pan J, Chen R, Liu B, Luo W, Zhong N. Epidemiology of cough in relation to China. Cough. 2013;9:18. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung KF, Pavord ID. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and causes of chronic cough. Lancet. 2008;371:1364–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Passalacqua G, Bousquet PJ, Carlsen KH, Kemp J, Lockey RF, Niggemann B, et al. ARIA update: I – Systematic review of complementary and alternative medicine for rhinitis and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1054–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.12.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muthu C, Ayyanar M, Raja N, Ignacimuthu S. Medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Kancheepuram district of Tamil Nadu, India. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:43. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cost of medications by primary diagnosis per month in INR and USD

Cost of healthcare resource use by primary diagnosis per month in INR and USD