Abstract

The translation system (the ribosome and associated factors) is the cell's factory for protein synthesis. The extraordinary catalytic capacity of the protein synthesis machinery has driven extensive efforts to harness it for novel functions. For example, pioneering efforts have demonstrated that it is possible to genetically encode more than the 20 natural amino acids and that this encoding can be a powerful tool to expand the chemical diversity of proteins. Here, we discuss recent advances in efforts to expand the chemistry of living systems, highlighting improvements to the molecular machinery and genomically recoded organisms, applications of cell-free systems, and extensions of these efforts to include eukaryotic systems. The transformative potential of repurposing the translation apparatus has emerged as one of the defining opportunities at the interface of chemical and synthetic biology.

Background

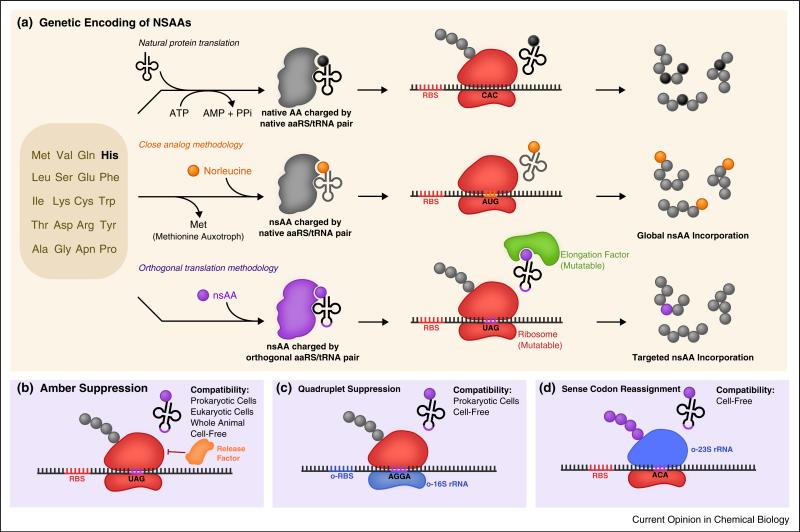

Proteins represent a crucial class of biomolecules, universally employed by all living organisms to fulfill essential structural, functional, and enzymatic roles necessary to support life. In nature, these polymers are composed generally of twenty natural amino acid (AA) building blocks, which can be combined in a near-infinite number of combinations to generate an impressive level of structural and functional diversity (Figure 1). However, many interesting chemistries cannot be accessed using only these natural building blocks; accordingly, for some time there has been an interest in the incorporation of nonstandard amino acids (nsAAs) featuring novel functional sidegroups to expand the repertoire of protein functions.

Figure 1.

Methods for genetic code expansion. (a) Two general paradigms exist for the genetic incorporation of nonstandard amino acids into proteins contrasted with the natural process of encoding the canonical amino acids. The close analog methodology complements a natural amino acid auxotrophy with a close nonstandard analog, enabling global protein labeling by native translational machinery. The orthogonal translation methodology introduces orthogonal translational machinery engineered to charge an orthogonal tRNA with a nonstandard amino acid, enabling site-specific targeted genetic incorporation. Certain nsAAs may require additional mutations in the elongation factor or the ribosome. (b) For targeted genetic incorporation, amber suppression is the most widely used technique. Competition with release factors limits efficiency, and methods are discussed to overcome this. (c) Quadruplet suppression can be performed with appreciable efficiency with the use of an engineered orthogonal 16S ribosomal subunit [27••]. (d) Sense codons can be reassigned by using an orthogonal 23S ribosomal subunit, engineered to accept a synthetic set of tRNAs [60].

Broadly speaking, nsAAs can be divided into two classes. Synthetic nsAAs are chemically synthesized, and can bear little resemblance to their naturally occurring counterparts. Posttranslational modifications (PTMs) are modified derivatives of canonical amino acids. In recent years, two distinct approaches for the incorporation of nsAAs into proteins have emerged (Figure 1(a)). One such approach is global suppression. This method uses auxotrophic strains that are incapable of synthesizing a particular AA. When grown in the presence of a nsAA that bears close structural resemblance to the ‘missing’ AA, the organism's native translational machinery incorporates the nsAA instead [1,2]. An alternative approach uses orthogonal translation systems (OTSs) to genetically encode an nsAA of interest site-specifically by reassignment of codons, typically the amber stop codon (TAG) in a strategy known as amber suppression [3].

To date, >150 nsAAs have been incorporated by OTSs into polypeptides [4] for a wide range of applications including the introduction of bioorthogonal handles for protein tagging [5,6], alteration of protein stability [7,8], monitoring of protein localization, and genetic encoding of PTMs [9•,10–12]. As a result of these impressive efforts and the transformative potential to construct bio-based products beyond natural limits, expanding the genetic code has emerged as one of several major defining opportunities and points of synergy in chemical and synthetic biology.

This review focuses on recent developments in repurposing the translation system for novel functions, with a focus on codon reassignment. We first examine development of the molecular machinery at the heart of genetic code expansion. Next, we discuss nsAA incorporation in several contexts, including whole-genome recoding, prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems in vivo as well as in vitro. We end with a discussion of current challenges in the field and provide commentary on future opportunities.

Genetic code expansion using OTSs

Amber suppression seeks to ‘hijack’ the amber translational stop codon (TAG), recoding it into a sense codon corresponding to a nsAA of interest. Generally, this is accomplished using a suppressor tRNA that has been mutated to decode the amber codon and an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS) that has been mutated to accept the nsAA of interest and covalently load it onto the suppressor tRNA. These components are typically sourced from distant archeal species to ensure orthogonality to host translation machinery, undergoing directed evolution to improve their compatibility with a new nsAA and enable its site-specific incorporation into proteins.

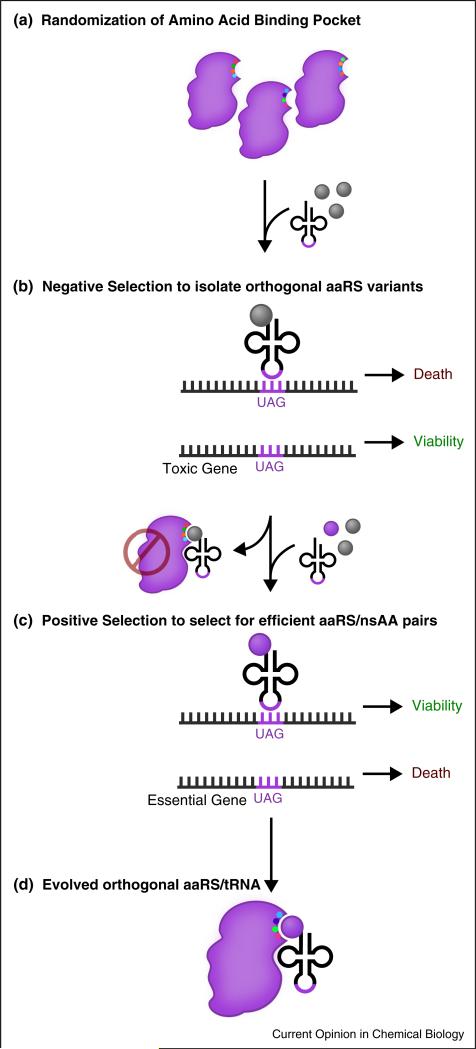

Directed evolution is the most widely used approach for the generation of novel OTS components [13–15] (Figure 2). These efforts start with the selection of a scaffold aaRS/tRNA pair. To date, several aaRS/tRNA pairs have been used in the creation of new OTSs. The Methanocaldococcus jannaschii TyrRS/tRNATyr pair is arguably the most common pair used, but is generally limited to aromatic amino acids and is not orthogonal in eukaryotes [4,15,16•]. The PylRS/tRNAPyl pair from Methanosarcina species (M. mazei, M. barkeri) has shown compatibility with eukaryotic systems [16•,17], and is an especially attractive starting point for evolution as the native PylRS natively demonstrates polysubstrate specificity [18] and tRNAPyl natively decodes the amber codon [19]. Other starting components have included the o-phosphoserine (Sep)RS from Methanococcus maripaludis [9•] and the TrpRS/tRNATrp pair from Saccharomyces cerevisiae [20]. The TyrRS/tRNATyr and LeuRS/tRNALeu pairs from Escherichia coli have also been used in OTS development for use in higher organisms [21,22]. After selecting a scaffold pair, crystal structural data is commonly used to identify specific residues in the aaRS that interact with the amino acid and the tRNA [13,23]. These residues are randomized to create a library of mutant aaRS variants in vitro and subsequently transformed in vivo. Finally, alternating rounds of selection identify mutant variants that are both functional and orthogonal to native machinery [13,15]. Negative selections eliminate variants that can charge the o-tRNA with native amino acids based on the synthesis of a toxic gene (e.g., barnase) in the absence of the cognate nsAA. Positive selections in the presence of the nsAA isolate variants that can charge the nsAA of interest onto the o-tRNA based on the suppression-dependent synthesis of a selectable marker (e.g., antibiotic resistance gene) or reporter (e.g., GFP). By subjecting ‘winners’ to alternating rounds of these screens, a nsAA-specific aaRS/tRNA pair can be identified.

Figure 2.

General methodology for engineering orthogonal translation systems for novel nsAAs. (a) Scaffold orthogonal aaRS/tRNA pairs are selected from distant organisms. Residues in the amino acid binding pocket of the aaRS are randomized. (b) A negative selection is performed to exclude aaRS variants capable of charging natural amino acids. In the absence of the nsAA, clones are selected by the inability to suppress a toxic gene. (c) A positive selection is performed to retrieve aaRS variants capable of charging the nsAA, selecting for the ability to suppress a selectable marker gene, such as an antibiotic resistance marker. (d) The selected orthogonal translation system consists of the orthogonal aaRS, tRNA, and nsAA.

While most new OTSs have focused on the generation of new nsAA–aaRS–tRNA pairs, some efforts have expanded OTSs to include additional components. In an exemplary study, incorporation of Sep was only possible after the development of a Sep-specific elongation factor [9•]. More recently, researchers were able to increase incorporation efficiency of selenocysteine (Sec) to >90% by engineering an elongation factor optimized for Sec [24]. nsAA incompatibility with the ribosome may also be an impediment to incorporation [25]. Platforms for ribosomal engineering and evolution will be integral to the elucidation and optimization of ribosome/nsAA interactions. Two recent approaches permit construction of modified ribosomes by decoupling organism fitness from ribosome function. In the first, researchers engineered a 30S subunit that is made orthogonal to natural components by a mutant 16S rRNA; this orthogonal subunit can be mutated to evolve novel function without impairing host viability [26,27••]. In a parallel approach, a system for the in vitro assembly of functional modified ribosomes has been developed [28–30]. We still await the development of a fully orthogonal ribosome in vivo.

Prokaryotic strain engineering tailored for genetic code expansion

Historically, nsAA incorporation via natural codon suppression has been limited by native translational components that have evolved essential function to faithfully decode all codons within an open reading frame. In the case of amber suppression, release factors are a class of proteins responsible for facilitating the termination of translation in response to ribosomal stalling at a stop codon. Competition between loaded suppressor tRNAs and release factor proteins at amber codons meant to encode nsAAs severely hinders successful suppression, with release factor activity resulting in the premature truncation of most of the protein product [31]. Resultant yields of the target nsAA-containing protein under these conditions are very low, especially for proteins containing multiple instances of the same nsAA [32•]. Conversely, the presence of OTSs on high copy plasmids in the presence of high concentrations of nsAA in vivo can also drive the incorporation of nsAAs at >300 amber codons that terminate native genes, resulting in cellular toxicity [33••].

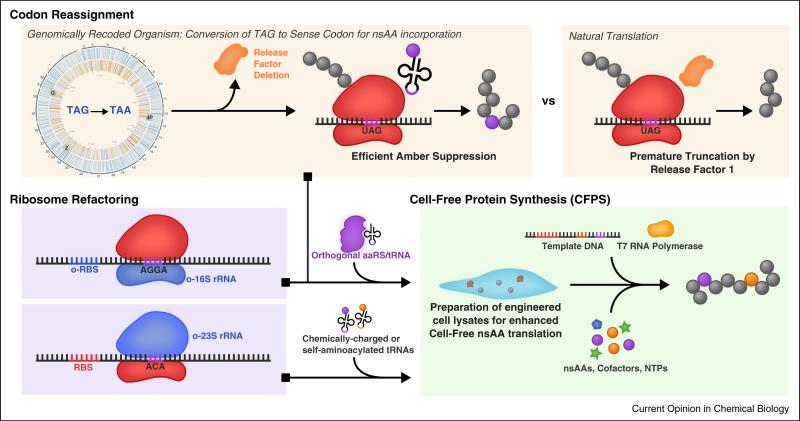

Consequently, much effort has gone into the elimination of release factor activity to improve nsAA incorporation. Initial attempts to outright delete the essential gene prfA that encodes release factor 1 (RF1) were stymied by cell inviability. Several early approaches, including release factor engineering [34] and supplementation in trans with partially recoded versions of the amber-dependent essential genes [35] permitted subsequent removal of prfA from the organism. More recent efforts have recoded the genome of E. coli. In such efforts, researchers edited the amber-dependent essential genes to terminate instead with the synonymous ochre codon (TAA) and deleted prfA from the organism. Incorporation of Sep was greatly enhanced in one such RF1-deficient recoded strain [36]. More recently, a recoded RF1-deficient strain was used in the preparation of cell lysates to improve the incorporation of the nsAA p-propargyloxy-l-phenylala-nine (pPaF) in vitro [32•,37].

These strain engineering efforts culminated with the recently reported completion of the first completely genomically recoded organism (GRO), an E. coli-derived strain that lacks all amber codons and RF1 [33••,38]. In this study, the authors systematically reassigned all 321 native instances of the amber (TAG) codon to the ochre (TAA) codon and deleted the prfA gene (Figure 3). In the resulting strain (C321ΔA) the amber codon is orthogonal and unrecognized by the remaining translational machinery, freeing it for use as a dedicated codon for nsAA incorporation. This strain has demonstrated improved properties for incorporation of nsAAs [33••] and has more recently been engineered to depend on nsAAs as a 21st synthetic biochemical building block [39•,40•].

Figure 3.

Genomically recoded organisms (GROs), strain engineering and in vitro nsAA translation. A genomically recoded organism reassigns the TAG stop codon to an open sense coding channel for enhanced nsAA amber suppression. Ribosomal engineering promotes other classes of codon suppression. These engineered strains can be used in vivo and via cell lysate, to develop in vitro translation systems with open coding channels for the production of nsAA-containing proteins.

Beyond amber suppression, some effort has been made to access additional codons for nsAA assignment, such as the ‘ochre’ (TAA) [41] and ‘opal’ (TGA) stop codons [42]. In a parallel approach, researchers instead sought to access non-natural quadruplet codons to encode nsAAs [43,44]. Combined with amber suppression, quadruplet suppression has enabled the incorporation of multiple distinct nsAAs into a single polypeptide [45••,46,47].

Cell-free systems for genetic code expansion

Cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) systems offer another approach for the incorporation of nsAAs (Figure 3). CFPS is the in vitro synthesis of proteins without using intact cells [48–50]. A lack of physical boundaries permits precise manipulation of reaction contents, simplifies product purification, and enables efficient incorporation of bulky/charged nsAAs that typically exhibit poor membrane permeability in vivo (e.g., pPaF) [51•]. Additionally, cell viability is no longer a constraint — reactions may be supplemented directly with purified OTS components, which have known toxicity effects in vivo [52]. These advantages, when combined with recent improvements to chassis strains and energy regeneration systems that have enabled high-yielding (>1 g/L) [49] and long-lasting (>10 h batch mode) [37] synthesis, have led to increased interest in the use of CFPS for nsAA incorporation into proteins [32•,37,51•,53–55].

One particularly exciting area for CFPS is in genetic code reassignment. For instance, translation systems reconstituted from purified components [56] or crude cell extracts depleted of native tRNAs [57] can be selectively supplied with purified tRNAs to essentially create a custom genetic code with select sense codons left ‘blank’ for nsAA reassignment [58,59]. Alternatively, in a recent effort a 50S ribosomal subunit was developed with mutations at the peptidyl transferase center that abolish its ability to use several native tRNAs for translation [60]. The use of this ribosome together with tRNAs containing compensatory point mutations enabled reprogramming of the genetic code, providing proof of concept for a potential new strategy for genetic code rewriting and expansion in vitro. Finally, in vitro nsAA-incorporation efforts uniquely benefit from the use of self-aminoacylating tRNAs featuring flexizyme ribozymes to extend the genetic code without the need for laborious nsAA–aaRS–tRNA cognate pair development [61].

Genetic code expansion in eukaryotic systems

Amber suppression has been adapted to eukaryotic systems as a tool for the interrogation of cellular biology. Engineered orthogonal aaRS/tRNA pairs have been used to genetically encode nsAAs that modulate PTMs by photocaging lysine [62] and serine [63] residues, promote chromatin condensation with crosslinking residues [64], introduce chemical handles for fluorescent protein labeling and live cell imaging [65], among many other applications. Most often, OTS components are scaffolded on M. mazei PylRS/tRNAPyl, E. coli TyrRS/tRNATyr or E. coli LeuRS/tRNALeu pairs, engineered in E. coli or S. cerevisiae [21], and then ported to mammalian vectors.

In addition to unicellular organisms and tissue culture, amber suppression with engineered PylRS/tRNAPyl derivatives has been demonstrated in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans [66••]. Similar work has been successful in the fly Drosophila melanogaster, where nsAAs could be incorporated both site-specifically and tissue-specifically into proteins [67].

As with prokaryotic systems, competition with release factors remains a major barrier for efficient amber suppression in eukaryotes. Though orthogonal ribosomes or genome-wide codon reassignment have not yet been demonstrated in these systems, efforts are being made in this direction. Recently, a de novo synthesis of S. cerevisiae chromosome III included TAG → TAA stop codon reassignments [68••]. As this effort is extended to the remaining chromosomes, the resulting synthetic strain will lack native TAG codons, motivating the need to engineer the specificity of the single eukaryotic release factor to exclude amber recognition.

An additional challenge is native quality control machinery. Nonsense mediated decay (NMD) surveys transcripts for nonsense codons excessively distal from the 3′ end, triggering degradation in response to their presence [69]. Addressing this limitation, the pathway has been knocked out in C. elegans to boost amber suppression efficiency [66••].

A final consideration in these systems is the expression of the orthogonal tRNA, as eukaryotic RNA polymerase III is typically recruited to intragenic A and B-box promoter sequences. One solution has been to identify orthogonal aaRS/tRNA pairs containing A and B-like elements. For instance, E. coli's TyrRS/tRNATyr is orthogonal in S. cerevisiae and contains its consensus A and B-box [21]. However, OTSs scaffolded on PylRS/tRNAPyl, lack such intragenic sequences. Instead these tRNAs have been successfully expressed by co-opting dicistronic tRNA scaffolds such as tRNAArgUCU [70], or by using the extragenic U6 RNA polymerase III promoter [71].

Current challenges and future outlook

Looking forward, three major challenges define the trajectory of this field: the development of more efficient OTSs, accession of more open coding channels to enable multi-site incorporation of multiple nsAAs, and the generation of OTSs engineered for more exotic nsAAs.

Engineered OTSs suffer poor enzymatic efficiencies relative to native translational machinery [25]. Overall, this represents a problem of insufficient aaRS evolution, as typically only 6–8 residues proximal to the amino acid binding pocket are mutagenized. Further diversification is limited by library size constraints — the randomization of six residues results in a library of nearly 108 members, quickly saturating standard screening techniques. The use of computational protein modeling may enable more rational engineering, guided by in silico binding predictions [72]. Further, during evolution OTSs are screened for the ability to suppress just a few codons in selectable markers, whereas native translational machinery faces a load of thousands of codons. Increasing the load on OTSs may promote the selection of more catalytically active enzymes. Amber suppression of native essential genes has proven to be an effective strategy to tie strain viability to nsAA incorporation [39•,40•], offering a potential route to drive protein evolution under more stringent selective conditions.

Multi-site incorporation of a single nsAA at high levels (>10) has remained elusive due to the use of codons that have their cognate translation components (e.g., RF1) out-competing the incorporation of the nsAA, as well as the impaired activity of OTSs. These limitations are compounded in efforts to achieve multi-site incorporation of multiple distinct nsAAs. This pursuit will require advances in our ability to suppress multiple codons simultaneously, and in the development of mutually orthogonal OTSs. In vivo, the field is currently limited to suppressing two distinct codons simultaneously. The use of nonstandard nucleotide bases [73] may enable crossing this barrier in the near future. Alternatively, radical recoding strategies that extend off the RF1-deficient GRO may provide a route to more codons. Even with more codons, new advances in orthogonal OTSs are needed. OTSs have been selected against interactions with native translational machinery, but not necessarily against other OTSs. This raises the potential for OTS cross-reactions when expressed simultaneously. Work is being done to develop orthogonal tRNA acceptor stems [74] and additional aaRS/tRNA scaffolds to mitigate this cross-orthogonality.

Finally, certain biological constraints limit the scope of nsAA diversity. These include limitations on cell membrane permeability and steric incompatibility with the ribosome and other translational components such as elongation factors. Further engineering these components with cell-free systems or synthetic ribosomes is necessary for increasing the available nsAA chemical space.

Overcoming some of these technological barriers will better enable the creative potential of nonstandard protein development in producing the next wave of highly functionalized biomaterials and protein therapeutics [75] with broad applications in medicine, materials science and biotechnology.

Acknowledgements

MCJ gratefully acknowledges the National Science Foundation (MCB-0943393), the Office of Naval Research (N00014-11-1-0363), the DARPA YFA Program (N66001-11-1-4137), the Army Research Office (W911NF-11-1-0445), the NSF Materials Network Grant (DMR-1108350), the DARPA Living Foundries Program (N66001-12-C-4211), the David and Lucile Packard Foundation (2011-37152), ARPA-E (DE-AR0000435), and the Chicago Biomedical Consortium with support from the Searle Funds at the Chicago Community Trust for support. BJD is an NSF Graduate Fellow. FJI gratefully acknowledges support from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (N66001-12-C-4020, N66001-12-C-4211); Department of Energy (152339.5055249.100); Gen9, Inc., DuPont Inc. and the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.van Hest JCM, Kiick KL, Tirrell DA. Efficient incorporation of unsaturated methionine analogues into proteins in vivo. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:1282–1288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/Ja992749j. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ngo JT, Tirrell DA. Noncanonical amino acids in the interrogation of cellular protein synthesis. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:677–685. doi: 10.1021/ar200144y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ar200144y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chin JW. Expanding and reprogramming the genetic code of cells and animals. Annu Rev Biochem. 2014;83:379–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035737. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dumas A, Lercher eL, Spicer CD, Davis BG. Designing logical codon reassignment — expanding the chemistry in biology. Chem Sci. 2014;6:50–69. doi: 10.1039/c4sc01534g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chin JW, et al. Addition of p-azido-L-phenylaianine to the genetic code of Escherichia coli. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9026–9027. doi: 10.1021/ja027007w. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/Ja027007w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang H, Srivastava P, Zhang C, Lewis JC. A general method for artificial metalloenzyme formation through strain-promoted azide–alkyne cycloaddition. Chembiochem. 2014;15:223–227. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300661. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cbic.201300661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho H, et al. Optimized clinical performance of growth hormone with an expanded genetic code. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9060–9065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100387108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1100387108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tada S, et al. Genetic PEGylation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0049235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9•.Park HS, et al. Expanding the genetic code of Escherichia coli with phosphoserine. Science. 2011;333:1151–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.1207203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1207203. [By adding phosphoserine to the protein engineer's toolkit, this work facilitated study of one of the most important and ubiquitous classes of PTMs in all of protein biology. This work also highlights an important consideration for future OTS development with the first instance of a nsAA-specific engineered elongation factor.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S, et al. A facile strategy for selective incorporation of phosphoserine into histones. Angew Chem. 2013;52:5771–5775. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300531. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201300531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neumann H, Peak-Chew SY, Chin JW. Genetically encoding N(epsilon)-acetyllysine in recombinant proteins. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:232–234. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ai HW, Lee JW, Schultz PG. A method to site-specifically introduce methyllysine into proteins in E. coli. Chem Commun. 2010;46:5506–5508. doi: 10.1039/c0cc00108b. http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c0cc00108b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Brock A, Herberich B, Schultz PG. Expanding the genetic code of Escherichia coli. Science. 2001;292:498–500. doi: 10.1126/science.1060077. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1060077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L, Xie J, Schultz PG. Expanding the genetic code. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:225–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.101105.121507. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.101105.121507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santoro SW, Wang L, Herberich B, King DS, Schultz PG. An efficient system for the evolution of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase specificity. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:1044–1048. doi: 10.1038/nbt742. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nbt742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16•.Nozawa K, et al. Pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase-tRNA(Pyl) structure reveals the molecular basis of orthogonality. Nature. 2009;457:1163–1167. doi: 10.1038/nature07611. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature07611. [Orthogonal in many prokaryotic and eukaryotic translation systems, the discovery and characterization of the pyrrolysine PylRS/tRNAPyl pair was a tremendous boon to nsAA incorporation efforts. This work elucidates the molecular underpinnings of the orthogonality of PylRS/tRNAPyl in its various hosts.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fekner T, Chan MK. The pyrrolysine translational machinery as a genetic-code expansion tool. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 201115:387–391. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.03.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wan W, Tharp JM, Liu WR. Pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase: an ordinary enzyme but an outstanding genetic code expansion tool. Biochim Biophys Acta. 20141844:1059–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.03.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li WT, et al. Specificity of pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase for pyrrolysine and pyrrolysine analogs. J Mol Biol. 2009385:1156–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.032. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellefson JW, et al. Directed evolution of genetic parts and circuits by compartmentalized partnered replication. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2714. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chin JW, et al. An expanded eukaryotic genetic code. Science. 2003;301:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.1084772. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1084772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ai HW, Shen W, Brustad E, Schultz PG. Genetically encoded alkenes in yeast. Angew Chem. 2010;49:935–937. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905590. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.200905590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Wang L, Schultz PG, Wilson IA. Crystal structures of apo wild-type M. jannaschii tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (TyrRS) and an engineered TyrRS specific for O-methyl-L-tyrosine. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1340–1349. doi: 10.1110/ps.041239305. http://dx.doi.org/10.1110/ps.041239305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haruna K, Alkazemi MH, Liu Y, Soll D, Englert M. Engineering the elongation factor Tu for efficient selenoprotein synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:9976–9983. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku691. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Donoghue P, Ling J, Wang YS, Soll D. Upgrading protein synthesis for synthetic biology. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:594–598. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rackham O, Chin JW. A network of orthogonal ribosome mRNA pairs. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:159–166. doi: 10.1038/nchembio719. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nchembio719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27••.Wang K, Neumann H, Peak-Chew SY, Chin JW. Evolved orthogonal ribosomes enhance the efficiency of synthetic genetic code expansion. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:770–777. doi: 10.1038/nbt1314. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nbt1314. [This important manuscript demonstrates the feasibility of using orthogonal ribosomes to evolve novel function without impacting host viability, providing crucial guidance for potential future projects that attempt to reconcile nsAA incorporation bottlenecks based in ribosomal incompatibility.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jewett MC, Fritz BR, Timmerman LE, Church GM. In vitro integration of ribosomal RNA synthesis, ribosome assembly, and translation. Mol Syst Biol. 20139:678. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/msb.2013.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fritz BR, Jewett MC. The impact of transcriptional tuning on in vitro integrated rRNA transcription and ribosome construction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:6774–6785. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y, Fritz BR, Anderson MJ, Schoborg JA, Jewett MC. Characterizing and alleviating substrate limitations for improved in vitro ribosome construction. ACS Synth Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1021/sb5002467. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/sb5002467. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Hong SH, Kwon YC, Jewett MC. Non-standard amino acid incorporation into proteins using Escherichia coli cell-free protein synthesis. Front Chem. 20142:34. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00034. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2014.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32•.Hong SH, et al. Cell-free protein synthesis from a release factor 1 deficient Escherichia coli activates efficient and multiple site-specific nonstandard amino acid incorporation. ACS Synth Biol. 2014;3:398–409. doi: 10.1021/sb400140t. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/sb400140t. [Building on earlier success in nsAA incorporation using cell-free systems, these authors rationally modify a partially recoded E. coli strain to improve productivity in vitro via the knockout of putative negative effectors of cell-free protein synthesis. Their improved strain was able to synthesize 550 mg/L of nsAA-containing protein in batch mode.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33••.Lajoie MJ, et al. Genomically recoded organisms expand biological functions. Science. 2013;342:357–360. doi: 10.1126/science.1241459. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1241459. [Using state-of-the-art genome engineering technologies, these authors replaced every endogenous instance of the amber (TAG) stop codon in the genome of E. coli MG1655 with the synonymous ocher (TAA) stop codon and deleted prfA (RF-1) from the host genome. The amber codon is orthogonal to the remaining translational machinery in this strain, which could be transformative in the area of nsAA incorporation via amber suppression.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson DB, et al. RF1 knockout allows ribosomal incorporation of unnatural amino acids at multiple sites. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:779–786. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.657. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukai T, et al. Codon reassignment in the Escherichia coli genetic code. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:8188–8195. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq707. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkq707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heinemann IU, et al. Enhanced phosphoserine insertion during Escherichia coli protein synthesis via partial UAG codon reassignment and release factor 1 deletion. FEBS Lett. 2012586:3716–3722. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.08.031. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong SH, et al. Improving cell-free protein synthesis through genome engineering of Escherichia coli lacking release factor 1. Chembiochem. 2015 doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402708. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cbic.201402708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Isaacs FJ, et al. Precise manipulation of chromosomes in vivo enables genome-wide codon replacement. Science. 2011;333:348–353. doi: 10.1126/science.1205822. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1205822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39•.Rovner AJ, et al. Recoded organisms engineered to depend on synthetic amino acids. Nature. 2015;518:89–93. doi: 10.1038/nature14095. http://dx.doi.org/101038/nature14095. [By adding orthogonal translation systems to the chromosome of a GRO and site-specifically introducing amber codons into functionally conserved sites (Ref. [39•]) or core domains (Ref. 40•]) of essential proteins, these studies were able to generate organisms that are dependent on nsAAs for survival. These studies demonstrate unprecedented levels of biocontainment and establish these GROs as useful hosts for the evolution of more efficient OTS components.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40•.Mandell DJ, et al. Biocontainment of genetically modified organisms by synthetic protein design. Nature. 2015;518:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature14121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature14121. [See note Ref. [39•].] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wan W, et al. A facile system for genetic incorporation of two different noncanonical amino acids into one protein in Escherichia coli. Angew Chem. 2010;49:3211–3214. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000465. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201000465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Odoi KA, Huang Y, Rezenom YH, Liu WR. Nonsense and sense suppression abilities of original and derivative Methanosarcina mazei pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase-tRNA(Pyl) pairs in the Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cell strain. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057035. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson JC, et al. An expanded genetic code with a functional quadruplet codon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7566–7571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401517101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0401517101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chatterjee A, Lajoie MJ, Xiao H, Church GM, Schultz PG. A bacterial strain with a unique quadruplet codon specifying non-native amino acids. Chembiochem. 2014;15:1782–1786. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cbic.201402104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45••.Neumann H, Wang K, Davis L, Garcia-Alai M, Chin JW. Encoding multiple unnatural amino acids via evolution of a quadruplet-decoding ribosome. Nature. 2010;464:441–444. doi: 10.1038/nature08817. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature08817. [Accessing additional codons for the incorporation of multiple distinct nsAAs into a single peptide is one of the great challenges still facing the field of nsAA incorporation. This work provides a brilliant approach, tapping into non-natural quadruplet codons for nsAA encoding.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang K, et al. Optimized orthogonal translation of unnatural amino acids enables spontaneous protein double-labelling and FRET. Nat Chem. 20146:393–403. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1919. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nchem.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sachdeva A, Wang K, Elliott T, Chin JW. Concerted, rapid, quantitative, and site-specific dual labeling of proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:7785–7788. doi: 10.1021/ja4129789. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja4129789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jewett MC, Calhoun KA, Voloshin A, Wuu JJ, Swartz JR. An integrated cell-free metabolic platform for protein production and synthetic biology. Mol Syst Biol. 20084:220. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/msb.2008.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caschera F, Noireaux V. Synthesis of 2.3 mg/ml of protein with an all Escherichia coli cell-free transcription–translation system. Biochimie. 201499:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.11.025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carlson ED, Gan R, Hodgman CE, Jewett MC. Cell-free protein synthesis: applications come of age. Biotechnol Adv. 201230:1185–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.09.016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51•.Bundy BC, Swartz JR. Site-specific incorporation of p-propargyloxyphenylalanine in a cell-free environment for direct protein–protein click conjugation. Bioconj Chem. 2010;21:255–263. doi: 10.1021/bc9002844. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/bc9002844. [This work highlights one of the unique advantages of using cell-free systems for nsAA incorporation. The authors exploit the barrier-free nature of these systems to improve incorporation of a nsAA that suffers from low bioavailability in vivo due to its poor water solubility, surpassing previous in vivo yields by 27-fold.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nehring S, Budisa N, Wiltschi B. Performance analysis of orthogonal pairs designed for an expanded eukaryotic genetic code. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031992. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loscha KV, et al. Multiple-site labeling of proteins with unnatural amino acids. Angew Chem. 2012;51:2243–2246. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201108275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gerrits M, et al. Kudlicki W, Katzen F, Bennerr R, editors. Cell-free Protein Expression. Landes Bioscience. 2007:166–180. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goerke AR, Swartz JR. High-level cell-free synthesis yields of proteins containing site-specific non-natural amino acids. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;102:400–416. doi: 10.1002/bit.22070. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bit.22070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimizu Y, et al. Cell-free translation reconstituted with purified components. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:751–755. doi: 10.1038/90802. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/90802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahn J-H, et al. Preparation method for Escherichia coli S30 extracts completely dependent upon tRNA addition to catalyze cell-free protein synthesis. Biotechnol Bioproc Eng. 2006;11:420–424. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Forster AC, et al. Programming peptidomimetic syntheses by translating genetic codes designed de novo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6353–6357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1132122100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1132122100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cui Z, Stein V, Tnimov Z, Mureev S, Alexandrov K. Semisynthetic tRNA complement mediates in vitro protein synthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:4404–4413. doi: 10.1021/ja5131963. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja5131963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Terasaka N, Hayashi G, Katoh T, Suga H. An orthogonal ribosome-tRNA pair via engineering of the peptidyl transferase center. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:555–557. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1549. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ohuchi M, Murakami H, Suga H. The flexizyme system: a highly flexible tRNA aminoacylation tool for the translation apparatus. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 200711:537–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.08.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gautier A, Deiters A, Chin JW. Light-activated kinases enable temporal dissection of signaling networks in living cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:2124–2127. doi: 10.1021/ja1109979. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja1109979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lemke EA, Summerer D, Geierstanger BH, Brittain SM, Schultz PG. Control of protein phosphorylation with a genetically encoded photocaged amino acid. Nat Chem Biol. 20073:769–772. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.2007.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilkins BJ, et al. A cascade of histone modifications induces chromatin condensation in mitosis. Science. 2014;343:77–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1244508. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1244508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Uttamapinant C, et al. Genetic code expansion enables live-cell and super-resolution imaging of site-specifically labeled cellular proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:4602–4605. doi: 10.1021/ja512838z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja512838z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66••.Greiss S, Chin JW. Expanding the genetic code of an animal. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:14196–14199. doi: 10.1021/ja2054034. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja2054034. [With success in both prokaryotes and unicellular eukaryotes, nsAA incorporation in multicellular organisms was a logical next step. This paper is the first reported instance of nsAA incorporation via amber suppression in an animal, setting the stage for the development of molecular tools for the study of complex processes in whole organisms.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bianco A, Townsley FM, Greiss S, Lang K, Chin JW. Expanding the genetic code of Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:748–750. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1043. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68••.Annaluru N, et al. Total synthesis of a functional designer eukaryotic chromosome. Science. 2014;344:55–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1249252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1249252. [In an impressive triumph of DNA synthesis and assembly, these authors build a functional synthetic yeast chromosome. Importantly for nsAA incorporation efforts, the synthetic chromosome has undergone global UAG/UAA reassignment. This work thus lays the foundation for a recoded yeast strain, which has the potential to be as transformative in the area of eukaryotic amber suppression as the recoded E. coli strain has been in prokaryotic amber suppression.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Longman D, Plasterk RH, Johnstone IL, Caceres JF. Mechanistic insights and identification of two novel factors in the C. elegans NMD pathway. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1075–1085. doi: 10.1101/gad.417707. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.417707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hancock SM, Uprety R, Deiters A, Chin JW. Expanding the genetic code of yeast for incorporation of diverse unnatural amino acids via a pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pair. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14819–14824. doi: 10.1021/ja104609m. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja104609m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ma H, Zhang J, Wu H. Designing Ago2-specific siRNA/shRNA to avoid competition with endogenous miRNAs. Molecular therapy. Nucleic Acids. 20143:e176. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2014.27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/mtna.2014.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meiler JBD. ROSETTALIGAND: protein–small molecule docking with full side-chain flexibility. Proteins. 2006 doi: 10.1002/prot.21086. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/prot.21086. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Malyshev D, Lavergne DK, Chen T, Dai T, Foster N, Corrêa J, Romesberg IF. A semi-synthetic organism with an expanded genetic alphabet. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13314. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature13314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Neumann H, Chin SALJW. De novo generation of mutually orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pairs. J Am Chem Soc. 2010 doi: 10.1021/ja9068722. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja9068722. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Zimmerman ES, Heibeck TH, Gill A, Li X, Murray CJ, Madlansacay MR, Tran C, Uter NT, Yin G, Rivers PJ, et al. Production of site-specific antibody–drug conjugates using optimized non-natural amino acids in a cell-free expression system. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014;25:351–361. doi: 10.1021/bc400490z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]