Abstract

Inflammation plays a crucial role in neurodegenerative diseases, but the irritants responsible for this response remain largely unknown. This report addressed the hypothesis that hypochlorous acid reacts with dopamine to produce melanic precipitates that promote cerebral inflammation. Spectrophotometric studies demonstrated that nM amounts of HOCl and dopamine react within seconds. A second-order rate constant for the reaction of HOCl and dopamine of 2.5 × 104 M−1 s−1 was obtained by measuring loss of dopaminergic fluorescence due to HOCl. Gravimetric measurements, electron microscopy, elemental analysis, and a novel use of flow cytometry confirmed that the major product of this reaction is a precipitate with an average diameter of 1.5 µm. Flow cytometry was also used to demonstrate the preferential reaction of HOCl with dopamine rather albumin. Engulfment of the chlorodopamine particulates by phagocytes in vitro caused these cells to release TNFα and die. Intrastriatal administration of 106 particles also increased the content of TNFα in the brain and led to a 50% loss of the dopaminergic neurons in the nigra. These studies indicate that HOCl and dopamine react quickly and preferentially with each other and to produce particles that promote inflammation and neuronal death in the brain.

Keywords: Inflammation, Brain, Parkinson disease, Dopamine, Hypochlorous acid

1. Introduction

The impetus for the studies described herein was the observation of 3-chlorotyrosine in the brains of Alzheimer Disease (AD) patients [1]. 3-Chlorotyrosine is uniquely formed by the reaction of hypochlorous acid (HOCl) with tyrosyl residues [2,3]. HOCl is powerful two-electron oxidant produced by myeloperoxidase while reducing hydrogen peroxide to water:

| (1) |

Thus, 3-chlorotyrosine serves as a biomarker of the production of HOCl and indicates that the myeloperoxidase expressed in AD brains is active [1]. Since dopamine is derived metabolically from tyrosine, it is plausible that this catecholamine might be chlorinated by HOCl under the same conditions that give rise to 3-chlorotyrosine in the diseased brain, thereby providing a mechanism for the oxidative loss of dopamine. While losses of dopamine do occur in AD [4], the loss of this catecholamine is a defining characteristic of Parkinson Disease (PD). Myeloperoxidase is also active in PD [5]. These observations suggested the hypothesis that the loss of dopamine in PD may be due, in part, to chlorination by HOCl.

In the course of testing the above hypothesis, we observed that mixtures of HOCl and dopamine rapidly formed precipitates. This was to expected as neutral and basic solutions of catecholamine are known auto-oxidize and form precipitates [6]. The oxidation and precipitation of dopamine is also thought to resemble the formation of neuromelanin in the substantia nigra [7–10]. Zecca and his colleagues demonstrated that injection of neuromelanin into the substantia nigra of mice resulted in significant inflammation and loss of nigral neurons [11–13]. The importance of these studies was the identification of a possible irritant, namely neuromelanin, for the initiation and promulgation of inflammation in PD. Neuromelanin is a dark pigment that occupies so much of the cytoplasm of nigral cells that it accounts for the dark coloration of this nucleus [14]. The cells that bear neuromelanin are also those most vulnerable to loss in PD [15,16]. Thus – on the basis of amount and cell origin – neuromelanin released from dying neurons is likely to act as an irritant of inflammatory cells in PD [11,12]. Based on these observations, we hypothesized that the precipitates resulting from the reaction of HOCl and dopamine were a tainted form of melanin capable of damaging neurons and promoting inflammation. The possibility that PD involves the generation of tainted neuromelanins had been postulated earlier by Halliday and her colleagues [17]. In this report, we examined the propensity of HOCl and dopamine to react and precipitate, as well as the inflammatory and toxic nature of the resulting precipitates.

2. Results

2.1. Physiological amounts of HOCl and dopamine react within seconds

Dopamine concentrations in the cytosol or synapses of nigral neurons range from 10−5 to 10−8 M [18–21]. The amount of HOCl produced in the diseased brain, however, is not known but local amounts of 10−8 M are a reasonable estimate given that 106 neutrophils – the main source of HOCl in the body - generate 10−5 M amounts [22]. Given these considerations, we sought to determine the likelihood of HOCl and dopamine reacting at physiologically-relevant concentrations by spectrophotometric methods.

The UV-visible spectrum of 50 nM dopamine exhibits prominent absorbance from 210 to 240 nm and 255 to 295 nm attributed to the amine and catechol moieties respectively (Fig. 1) [23] HOCl increased these absorbances with no demonstrable isobestic points. Addition of either 25 or 50 nM HOCl increased the absorbance from 210 to 320 nm within the period taken to record the first spectrum: 5 to 45 s (Fig. 1A). The magnitude of this change remained the same for the ensuing 10 min (not shown) indicating that the reaction of HOCl was essentially complete within seconds. This was not the case for the reaction with 100 nM HOCl and 50 nM dopamine which continued to increase in absorbance over 10 min (Fig. 1B). For example, 100 nM HOCl produced 4.0, 8.9 and 9.8-fold increases in absorbance at 309 nm with 10 min (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that nM amounts of HOCl and dopamine react with each other to a significant extent within seconds.

Fig. 1.

HOCl alters the UV-visible spectrum of dopamine. The spectrum of 50 nM dopamine in PBS is presented along with spectra obtained 5 sec following the addition of HOCl (to the final concentrations of 25, 50 and 100 nM) at 22 °C (A). Spectra obtained 5, 300 and 600 s after the addition of 100 nM HOCl to 50 nM dopamine, in PBS and at 22 °C, are also shown (B). Each line represents the mean of at least four spectra that did not vary by more than 5% of the mean absorbance at all wavelengths.

To estimate the rate of at least one of the reactions between HOCl and dopamine we took advantage of the inherent fluorescence of dopamine [24] and the fact that chlorination of the catechol ring quenches aromatic fluorescence (Fig. 2). This figure shows that 50 µM HOCl completely quenched the fluorescence of an equimolar amount of dopamine within seconds. The loss of dopamine fluorescence due to HOCl proceeded with decaying exponential kinetics indicative of a first-order reaction between these molecules. The rates of quenching were also linearly related to the tested HOCl concentrations: 25 (Fig. 2A), 37.5, 50 and 75 µM (not shown) and allowed a determination of the second-order rate constant for this reaction of 2.5 × 104 M−1 s−1.

Fig. 2.

HOCl quenches the fluorescence of dopamine. Shown are representative traces of the quenching of 50 µM dopamine by 25, 50, and 75 µM HOCl. The fluorescence of dopamine under the conditions of the experiments was ~18,000 fluorescence units; which was normalized to 100% and used to calculate the percentage changes due to HOCl.

2.2. HOCl chlorinates the catechol and amine groups of dopamine

Particles formed in mixtures of dopamine and HOCl clogged a number of chromatographic matrices that were employed in attempts to analyze the products of this reaction. The potential for clogging was amplified by the addition of organic solvents to aqueous preparations of chlorodopamine which accelerate precipitation from these mixtures. Chlorodopamine particles can be solubilized in NaOH, but the resulting solutions forma clear gel when the pH is raised. Given these difficulties, we sought to retard the aggregation of chlorodopamine. Aggregate formation was retarded by acidic conditions and performing the reactions in acidified methanol was found to be the more efficient method of slowing the precipitation of chlorodopamine. The products of dopamine reacting with HOCl in acidified methanol were similar to those formed in aqueous solution, as indicated by diode UV-spectrometry and thin layer chromatography. This allowed a 1H-NMR study of reaction of dopamine and HOCl in acidified deuterated methanol (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

1H-NMR spectra of dopamine and the moieties chlorinated by HOCl. The upper tracings show the major resonances due to the aromatic and aliphatic regions of dopamine, while the lower tracings show the changes due to the addition of HOCl.

The 1H-NMR spectrum of dopamine is shown in Fig. 3 (top). The chemical shift assignments are based on literature values [25,26]. The lower-field portion of the spectrum (right) contains 2 triplets corresponding to the two methylene groups on the ethylamine portion of the molecule. The high field region (left) shows the aromatic protons. The addition of equimolar amounts of HOCl to dopamine in deuterated water resulted in the immediate formation of a dark precipitate, however no change was observed in the NMR spectrum. When HOCl was added to dopamine in acidified methanol, immediate precipitate formation was also observed, but the slowing of the reaction allowed the formation and chlorinated intermediates, which were identified from the NMR spectrum in Fig. 3 (bottom). In the aliphatic region, two additional triplets could be seen (2′-NH-Cl at 2.96 ppm and 2′-N-Cl2 3.02 ppm at which represent mono-chlorination (~10%) and di-chlorination (~1%) of the amine group. The formation of multiple species results in a broadening of the triplet in position 1. In the aromatic region, we see NMR spectra consistent with chlorination at the 5 position. The intensity of the signal from proton 5 is reduced, and two new peaks are formed, labeled 3* and 6*, appearing as singlets as the coupling to the 5 position is lost. Thus, the major compound formed by the addition of HOCl to dopamine in presence of acidified deuterated methanol was 5-chloro-4-(2-aminoethyl)benzene-1,2-diol. Significant amounts of N,5-Dichloro-4-(2-aminoethyl)benzene-1,2-diol and N-chloro-4-(2-aminoethyl) benzene-1,2-diol were also formed under these conditions.

2.3. The major products of the reaction of HOCl and dopamine is a chlorine-containing precipitate

Neutral and alkaline solutions of dopamine auto-oxidize and form precipitates [6]. The addition of HOCl to dopamine, at final concentrations of 20 and 10 mM respectively, also resulted in measurable precipitation (Fig. 4). Moreover, precipitation was favored by neutral and not acidic pH conditions (Fig. 4A, p < 0.01). Melanic precipitates also formed in solutions of dopamine in PBS, but at a much slower rate than solution containing dopamine and HOCl in PBS (not shown). Precipitates formed within min of the addition of HOCl to dopamine and attained a mass greater than that of the initial amount of dopamine within 24 h (Fig. 4B). This increase in mass is most likely due to the incorporation of chlorine into the reaction products as indicated by elemental analysis (Table 1). These data indicate that the major product of HOCl and dopamine is precipitate containing C:H:O:N:Cl with an approximate molecular ratio of 22: 20:10:3:1 (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

The major product of the reaction of HOCl and dopamine is a precipitate. Shown are the amounts of precipitates resulting from the mixing of HOCl and dopamine at final concentrations of 10 mM and 20 mM respectively. The reaction was carried in PBS at 22 °C for the indicated periods. Panel A depicts the later event in the reaction while panel B depicts both the earliest time points in the reaction and the effect of acidifying the reaction mixture. The amounts of precipitates are expressed relative to initial dopamine mass. Precipitate masses were determined gravimetrically from five mL aliquots of the dopamine/HOCl mixture filtered through glass fiber (≤32 min) or paper discs (>32 min). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM from four to six independent experiments. Note: the abscissa and ordinate scales vary between the panels in this figure.

Table 1. Elemental Analysis of chlorodopamine precipitates.

Elemental mass values are depicted as the mean ± SEM of three independent observations. Molecular proportions were obtained by dividing the mass values by themolecular weights of the atoms. These values were then normalized relative to the amount of chloride.

| C | H | O | N | Cl | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass (%) | 51.0 ± 0.69 | 3.84 ± 0.10 | 30.7 ± 0.37 | 7.57 ± 0.08 | 6.89 ± 0.31 |

| Molecular proportions |

21.9 | 19.7 | 9.91 | 2.79 | 1.00 |

2.4. HOCl and dopamine react to form 1.5 µm diameter aggregates

The particulate material produced by the reaction of dopamine and HOCl was composed of aggregated particles (Fig. 5A). Each particle had an approximate diameter of 100 nm. The arrangement of particles within the aggregates suggested that the process of aggregation proceeded by the successive addition of particles as depicted in Fig. 4B. Support for this idea was provided by flow cytometric analysis of the aggregates, which demonstrated the existence of a range of aggregate subpopulations (Fig. 5C). The smallest measurable aggregates form a distinct subpopulation corresponding to an approximate diameter of 50 nm and the first or leftmost peak in Fig. 5C. The next 10 subpopulations appear as discrete peaks representing the successive addition of particles as shown in Fig. 5B. As the size of the aggregates increase in size the peaks begin to crowd and form a dominant peak at 433 Forward Scatter units corresponding to a size of 1.5 µm (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

HOCl and dopamine react to form 1.5 µm diameter aggregates. Panel A depicts the ultrastructure of three aggregates produced by a 24 h reaction of HOCl and dopamine, at final concentrations of 10 mM and 20 mM respectively, in PBS at 22 °C. These aggregates consist of particles (A), which suggests that aggregation involves the successive addition of particles (B). The range of detectable aggregates, as measured by flow cytometry, is shown in panel C. These aggregates were produced by a 4 h reaction of HOCl and dopamine, 10 mM and 20 mM final concentrations respectively, in PBS at 22 °C. The black bars in panel C represent the mean of four separate experiments that varied less than 10% of the mean for each value of Forward Scatter. Supplemental Fig. 1 shows both the mean ± SEM for panel C. The peak position of 50 nm and 1.5 mm size markers is indicated in panel C (the distribution of these size markers is shown in Supplemental Fig. 2).

2.5. HOCl reacts with dopamine to produce aggregates in the presence of immobilized protein

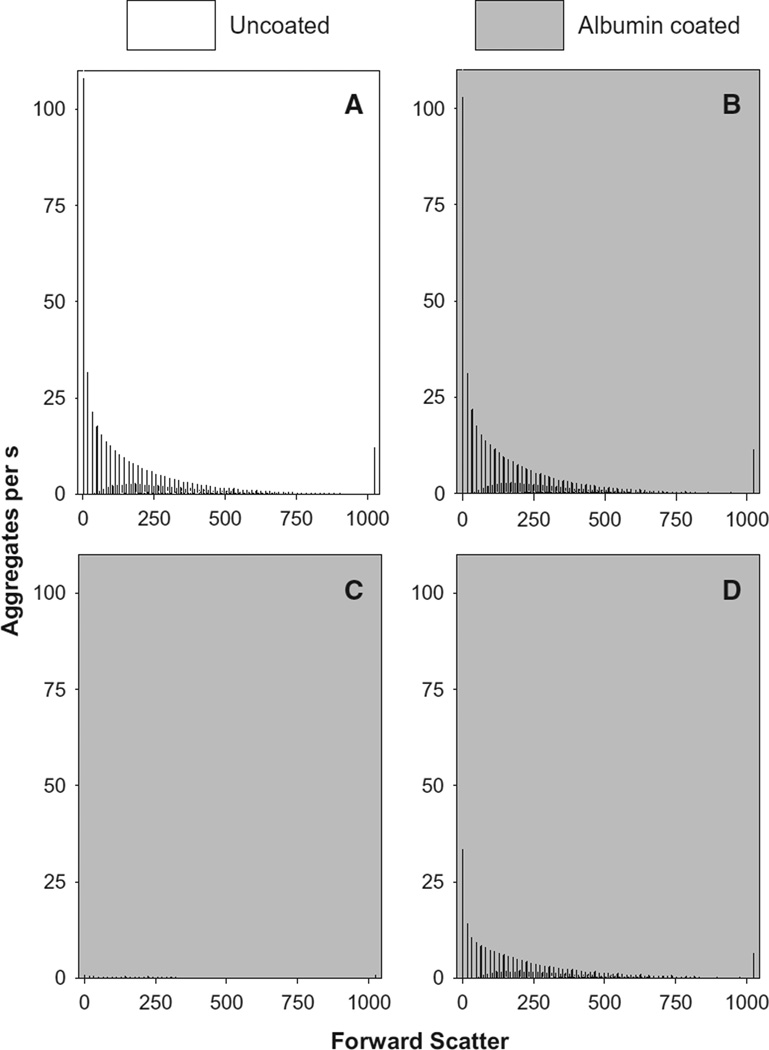

The studies depicted in Fig. 5 were performed using dopamine and HOCl at 10−2 M concentrations. Having demonstrated the possibility of measuring aggregate formation by flow cytometry, we then sought to determine the likelihood this formation at physiologically-relevant or 0.2 mM concentrations of dopamine (Fig. 6A). A similar distribution was obtained at 2 h (not shown) whereas few aggregates were detected in the first h of the reaction (not shown). In contrast to the distribution of aggregates obtained using 10−2 M concentrations of reactants (Fig. 5C), the distribution produced by 10−4 M amounts of HOCl and dopamine was skewed in favor of smaller-sized aggregates and lacked a 1.5 µm-sized peak.

Fig. 6.

HOCl and dopamine at 10−5M amounts produce aggregates in the presence of a HOCl scavenger. HOCl and dopamine were reacted in PBS at 22 °C for 4 h in either non-coated (A) or albumin-coated (B–C) reaction vessels. In the case of panels A and B, HOCl and dopamine were added concurrently. HOCl, however, was added to an albumin-coated plate 10 min prior to the addition of dopamine in experiments shown in panel C. The distribution of aggregates arising from the auto-oxidation of dopamine on albumin plates is shown in panel D. These distributions are shown as black bars representing the mean of four experiments that varied no more than 10% of the mean for each value of Forward Scatter. The final concentrations of HOCl and dopamine in these experiments were 100 and 200 µM respectively.

One possible barrier to the formation of aggregates in vivo is scavenging of HOCl and the chlorinated forms of dopamine by proteins and other moieties. This possibility was tested by coating the reaction vessels with albumin to scavenge chlorinating species [27]. Approximately 45 µg of albumin were attached to the surface of each reaction vessel. This coating, however, did not influence the formation of aggregates by dopamine and HOCl, at final concentrations of 200 and 100 µM respectively, after 4 h (c.f. Fig. 6A and B). Similar results were obtained with reactions of 1 and 2 h durations (not shown). The albumin coating was able to scavenge the amount of HOCl added to the reactions as shown in Fig. 6C. In these experiments, HOCl was added to the reaction vessel 10 min prior to the addition of dopamine which resulted in the formation of very few aggregates. Incubation of 200 µM dopamine on albumin-coated wells for 4 h at 22 °C also led to the generation of aggregates (Fig. 6D). The amount of aggregates formed by dopamine alone (Fig. 6D) was less than the amount produced by the combination of dopamine and HOCl (Fig. 6B) and supports the notion that the chlorination of dopamine by HOCl favors precipitation. Incubation of dopamine on albumin-coated wells, however, produced more aggregates than similar incubations on albumin-coated wells that had scavenged HOCl (c.f. Fig. 6C and D) and suggests that the reaction of HOCl and albumin had produced a surface that bound dopamine and prevented the formation of aggregates.

2.6. Dopamine and HOCl at 10−8 M concentrations react to produce aggregates

The successful observation of chlorodopamine aggregates arising from the reaction of 10−5 M amounts of dopamine and HOCl suggested the possibility of observing similar aggregates arising from 10−8 M amounts of these reactants. Our initial experiments with dopamine and HOCl - at final concentrations of 20 and 10 nM respectively – reacting at 22 °C produced no aggregates as detected by flow cytometry. Increasing the temperature of the reaction to 37 °C, however, resulted in the production of detectable aggregates after 3 h (Fig. 7A). A maximum of 1,455 ± 245 (14) aggregates/s was reached by 5 h (Fig. 6A) after which aggregates were apparently then lost from the reaction. Two possibilities might account for this loss of aggregates: formation of large aggregates or adherence to the reaction vessel walls. A comparison of the distributions presented in Fig. 7B and C support the latter mechanism. The furthermost right peak represents the largest aggregates and is smaller for 24 h reaction than the 5 h reaction. Indeed all of the peaks for the 24 h reaction are smaller than the 5 h reaction. These observations coupled with darkening of reaction vessel walls indicate that over time the aggregates adhere to plastic and are lost from the measurable population. Even so, these studies indicate nM amounts of dopamine and HOCl produce measurable quantities of aggregates.

Fig. 7.

HOCl and dopamine at 10−8M concentrations produce aggregates. Aggregates were produced by reacting HOCl and dopamine, at final concentrations of 10 and 20 nM respectively, in PBS at 22 °C for periods of up to 72 h. Panel A depicts the aggregates produced in either PBS or chlorodopamine mixtures as a function of reaction time and expressed as aggregates per s. The data in panel A is a summation of distributions of the type shown in panels B and C. These values are shown as the mean and SEM of 14 experiments (A). Panels B and C depict the distributions arising from the reaction of HOCl and dopamine for five (B) and 24 (B) h; the black bars in these panels represent the mean of 14 experiments that varied no more than 10% of the mean for each value of Forward Scatter. The inserts exhibit expanded views (Forward Scatter: 295–550) from the corresponding panels. Note: the abscissa and ordinate scales vary between the panels and inserts.

2.7. Aggregates of chlorinated dopamine inflame and kill cells

Since phagocytosis is the most likely mechanism for the activation of glial cell by the aggregates, THP-1 cells were used to investigate the ingestion of these structures – and the consequences thereof – by phagocytic cells. As expected, differentiated THP-1 cells engulfed aggregates within four h as shown in Fig. 8A and B. The detail from Fig. 8B illustrates that the phagocytosed aggregates resemble the structures shown in Fig. 5A. Prior to engulfment the aggregates migrate through the medium until contact with cells is made, followed by a significant congregation on or within the phagocytes (Fig. 8C and D). The uptake of aggregates by THP-1 cells resulted in the death of these cells as indicated by the incorporation of propidium Iodide into the DNA of damaged cells (Fig. 8F–H). Dead cells were evident after 4 h incubation with the aggregates (Fig. 8F). By 17 h, no viable cells remained (Fig. 8G and H) as evidenced by the crescents of deposited aggregates (indicated by arrows in Fig. 8G and F); the DNA of these cells had either degraded or diffused away. The cells in these studies were also incubated with the apoptosis indicator Annexin V Alexa Fluor®, but only exhibited staining for the propidium iodide indicative of necrosis.

Fig. 8.

Phagocytic cells engulf chlorodopamine aggregates and then die. Shown are electron micrographs of differentiated THP- 1 cells incubated in the absence (A) and presence (B) of aggregates. In each case, the large organelle dominating the left side of the cells is the nucleus, while the phagocytic vacuole dominates the right side. The dark globular structures present within the phagocytic vacuole are engulfed aggregates (B). These aggregates are also shown at 2.5× greater magnification in the detail taken from panel B and resemble the assemblages shown in Fig. 2A. THP-1 cells were incubated with 48 aggregates per cells for varying times (e.g. 4 h in B). The association of the particles with THP-1 cells after 2.5 h is shown in panels C and D at 100 and 400×magnifications respectively. Panels E and F represent the while light and red fluorescence (propidium iodide) images of the same visual field after 4 h incubation with aggregates. The arrows indicate the same cell in each field (E and F). Similarly, THP-1 cells stained with propidium iodide after 17 h incubation with aggregates is shown in panels G and H at 100 and 200× magnifications respectively. The arrows indicate the same cell in both fields as a deposit of engulfed aggregates but lacking a stained nucleus.

The loss of cellular viability due to aggregates was also confirmed by the measurement of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in the medium bathing the cells (Fig. 8A). LDH release from THP-1 cells was apparent after 24 h incubation with 6 aggregates per cell and complete at the higher densities of 24 and 48 aggregates per cell (Fig. 9A). These aggregates also induced a loss of LDH from differentiated SH SY5Y cell, an in vitro model of dopaminergic cells, but only at the highest density of aggregates tested: 100 aggregates per cell (Fig. 9A), indicating a marked difference in the sensitivity of THP-1 and SH SY5Y cells to the toxicity of aggregates. Incubation of differentiated THP-1 cells with 24 aggregates per cells also led to a release of TNFα (Fig. 9B). This release was apparent within two and half h of incubation and prior to any significant loss of viability (data not shown).

Fig. 9.

Chlorodopamine aggregates cause cells to release of LDH and TNFα. Differentiated THP-1 cells were incubated with 0, 3, 6, 12, 24 or 48 aggregates per cells whereas differentiated SH SY5Y cells were incubated with 0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50 or 100 aggregates per cells for 24 h. LDH release into the cell media after 24 h incubation was expressed as a percentage of the LDH content present (A). The basal amounts of LDH released into the media of THP-1 and SH SY5Y cells were 4.78 ± 2.68% and 6.02 ± 0.49% of the total cellular content of LDH respectively. Panel B shows the cell media concentrations of TNFα after a 2.5 h incubation of THP-1 cells with and without 24 aggregates per cells. Shown are the mean ± SEM for three independent experiments performed using THP-1 cells and five experiments using SH SY5Y cells.

The responses of THP-1 cells and cultured microglia to aggregates are similar with regards to phagocytosis and TNFα production [28,29]. Given this similarity, we elected to test the toxicity and inflammatory nature of the aggregates by injecting these assemblages into the brain of mice rather than testing other cell culture models. Consequently, 106 aggregates were injected into the striatum and the extent of neuronal loss estimated using the methods of Petroske et al. [30] and Laloux et al. [31]. The dopaminergic neurons present in three representative sections of the substantia nigra were enumerated: a section rostral to the incipient medial terminal nucleus of the accessory optic tract (MT) at −3.1 bregma, a section between incipient MT and caudal portion of the MT at −3.4 bregma, and a section between the caudal portion of the MT and the caudal portion of the interfasicular nucleus (IF) at−3.7 bregma. These sections represent the rostal, intermedial, and caudal portions of the substantia nigra and the values we obtained for the control animals (those injected with ACSF) were comparable to those reported by Laloux et al. [31]. In contrast, the injection of aggregates resulted in a significant loss of dopaminergic neurons (Fig. 10A–C). This loss was accompanied by increased amounts of TNFα in the brain three days after the injection of aggregates (Fig. 10D). The amounts of TNFα in the whole brain were still significantly elevated, albeit at lower levels, 28 days post injection. These later changes were also accompanied by increased immunohistochemical and Western blot staining for ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1 [32,33], a marker of activated microglia in the brain, throughout the brain (not shown). At this late stage, the ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1 staining is diffuse through brain and not shown for this reason. These findings are consistent with the activation of inflammatory response by the injected aggregates leading to the death of neurons in brain.

Fig. 10.

Intrastriatal administration of chlorodopamine aggregates results in inflammation and neuronal loss. Representative micrographs of tyrosine hydroxylase staining in the substantia nigra 4 weeks after the intrastriatal injections of either ACSF (A) or 106 chlorodopamine particles (B). SN: substantia nigra, cp: cerebral peduncle, MN: mamillary nucleus Bar = 250 µm. Magnification at 400×, 40 µm thick sections. The neuronal loss due to the injection of particles was quantified and presented in panel C as the mean and SEM for three mice treated with ACSF and five mice with 106 particles. The TNFα production induced three and 28 days after the administration of particles is given the panel D as the mean and SEM of thee experiments.

3. Discussion

Our interest in the possibility that HOCl contributes to encephalitic diseases stems from an appreciation of the destructive power of this specie [34–37] and the lack of adequate defenses against this destruction by the brain [38–41]. Here we reported that the major product of the in vitro reaction of HOCl and dopamine is a melanic precipitate capable of damaging the brain. In addition, we described the use of flow cytometry to measure the aggregation responsible for the formation of these precipitates. The formation of aggregates was not inhibited by albumin, a known scavenger of chlorination, suggesting that HOCl preferentially reacts with dopamine. A determination of the rate at which HOCl chlorinates the catechol moiety further supported the idea that this oxidant reacts preferentially with dopamine in vivo. Extracellular precipitates are typically removed by phagocytosis and the aggregates were engulfed by phagocytic cells in vitro. This event led to the release of TNFα from these cells and followed by necrosis. Intrastriatal administration of 106 aggregates resulted in cerebral inflammation and the loss of dopaminergic neurons from the substantia nigra.

The concept that dopamine is oxidized into harmful species has antecedents in the studies by Bisaglia et al. (2014) and Leong et al. (2014), and is explicable given both its amounts within the nigra and the tendency of this catecholamine to oxidize. Nigral dopamine concentrations range from 10−8 to 10−1 M. Synaptic vesicles enclose 33,000 molecules of dopamine which equates to a local concentration of 0.3 M [42], vesicular release results in extrasynaptic accumulations of up to 50 nM dopamine [18,19], and the cytosol of dopaminergic neurons contains 50 µM amounts of this neurotransmitter [20,21]. Dopamine readily oxidizes to a variety of reactive species that undergo polymerization and aggregation to form melanins [6,7]. Here we demonstrated that the oxidation of dopamine by HOCl - a reactive oxygen species known to be produced in neurodegenerative diseases [1,5,43,44] - produced melanic aggregates capable of damaging the brain. This damage is likely to be due to the phagocytosis of the particles by microglia near the injection sites. Incubation of differentiated THP-1 cells with as little as six aggregates per cell was sufficient to damage these cells (Fig. 9A). THP-1 cells phagocytose up to 40 latex particles per cell with no ill effects [45]. The toxicity of the aggregates is probably due to the incorporated chloride incorporated (Table 1). Treatment of aggregates with hydrogen sulfide removed some of the chloride atoms and generated particulate material that neither killed THP-1 cells nor caused these cells to secrete TNFα (Jeitner and Kalogiannis: unpublished findings).

HOCl is formed in the AD and PD brain as evidenced by the production of HOCl-modified proteins [2,3,5] and 3-chlorotyrosine [1]. The pathological production of HOCl in the brain is also indicated by the availability of myeloperoxidase and its substrate H2O2 (Reaction 1). Myeloperoxidase is present in the glial cells affected by AD and PD [1, 43,44,46–48] as well as neurons in the AD brain [1]. Moreover, Choi et al. [5] demonstrated this enzyme is catalytically active in nigral extracts from parkinsonian mice. Hydrogen peroxide is released from the nigral neurons in a pulsatile manner with amplitude of 4.8 µM and a frequency 8.2 min−1 [19]. The levels of this peroxide are expected to be higher in PD since the majority of disease-causing gene mutations and toxins prompt mitochondrial complex I to reduce oxygen to superoxide and ultimately forming H2O2 [49]. In support of this contention, the addition of rotenone to nigral neurons increased the amount of H2O2 released by these cells above the aforementioned basal levels [19]. Myeloperoxidase is usually constrained within cells or to the glycocalyx when released [50]. Therefore, the amount of Cl− oxidized to HOCl is limited by the diffusion of H2O2 to the enzyme. In practice this is not a significant limitation because H2O2 diffuses with the same ease as water. Even so, conversions 1 to 10% of the 4.8 µM H2O2 produced by dopaminergic neurons [19] would still generate between 48 to 480 nM amounts of HOCl, which as we have demonstrated is sufficient to chlorinate dopamine (Figs. 1 and 2). The presence of 3-chlorotyrosine and HOCl-modified proteins indicates that at least a portion of the H2O2 produced in the parkinsonian and AD brain is used to oxidize Cl− to HOCl [1,5].

HOCl and dopamine are likely to react in vivo based on our determination of the second-order rate constant for this reaction of 2.5 × 104 M−1 s−1. This constant lies within the range of the values derived for the oxidation of amines by HOCl, namely 103–105 M−1 s−1 [36, 51]. Since amines are oxidized by HOCl in vivo [36], dopamine must also be chlorinated under same conditions. The congruence of the constants for the reactions of amines and dopamine with HOCl indicates that some amines will compete with dopamine for reaction with HOCl, which we confirmed with ethanolamine and NH4Cl (not shown). While this competition may limit the reaction between dopamine and HOCl, it should be noted that chloramines are also potent chlorinating agents [52,53]. The rate at which dopamine is chlorinated by HOCl is also at least 300 times faster than the rate at which tyrosyl resides are converted to 3-chlorotyrosine by HOCl: 71 M−1 s−1 [54]. Since 3-chlorotyrosine levels [2,3] are elevated in the brains of AD patients and parkinsonian mice [1,5] HOCl must react with catecholamines if formed in the vicinity of these neurotransmitters.

1H-NMR spectrometry revealed that the major product of the reaction of HOCl and dopamine was 5-chloro-4-(2-aminoethyl)benzene-1,2-diol followed by the production of N,5-dichloro-4-(2-aminoethyl)benzene-1,2-diol, N-chloro-4-(2-aminoethyl)benzene-1,2-diol, and trace amounts of N-dichloro-4-(2-aminoethyl)benzene-1,2-diol (compounds I–IV, respectively, in Fig. 11). These products were observed when the reaction was performed in acidified methanol. Even so, the formation of compound I in aqueous solutions was indicated by the loss of dopamine fluorescence following the addition of HOCl. The catechol ring of dopamine is primarily responsible for the fluorescence of this molecule and the loss of this fluorescence due to HOCl is probably due to ring chlorination. This reaction may result from interactions with HOCl or one of the chloramines formed by the reaction between HOCl and the amine group of dopamine: compounds II–IV (Fig. 11). Compound I could also arise from chlorination of the ring at the 5 position by the neighboring chloramine in compound III. This aryl carbon can react with the alkyl amine as indicated by the facile formation of 5,6-hydroindole under oxidizing conditions [6]. Interestingly, 5,6-hydroindole was not detected following the reaction of dopamine and HOCl in acidified methanol (using 1H-NMR spectrometry) or aqueous solutions (using thin-layer chromatography). 5,6-hydroindole was of interest because it participates in the production of melanins [6] and the spectral properties of this dye [55] are comparable to those reported in Fig. 1.

Fig. 11.

Compounds formed by the reaction of HOCl and dopamine. The products shown were based on the 1H-NMR studies (see text and Fig. 3). RCl refers to either HOCl or the chloramines indicated in the figure: compounds II–IV.

The products of the reaction of HOCl and dopamine rapidly polymerized to form the spherical structures with diameters of approximately 50 nm. These dimensions are comparable to those reported for the smallest particles contained in human neuromelanin [56,57] and suggest that the polymerization of oxidized dopamine is limited. This is explicable given the wealth of compounds resulting from the chlorination or oxidation of dopamine as described here and elsewhere [6]. The polymers arising from these products are expected to contain significant amounts of amorphous regions and therefore unlikely to grow beyond a certain size [58]. The presence of chloride in the aggregates and the rapid polymerization of acidified solution of chlorinated dopamine brought to neutrality, support the notion that the chlorinated forms of dopamine polymerized to form nm-sized particles.

The above particles self-associated to form a wide variety of differently-sized aggregates as demonstrated by flow cytometry and electron microscopy. To our knowledge, this report is the first to describe the use of flow cytometry to study the in vitro formation of aggregates. The current methods available for such studies are limited to studying the assembly of a few aggregates (e.g., dynamic light scattering and chromatography) or of aggregation in bulk (e.g., turbidity measurements). Flow cytometry performs light scattering measurements on an aggregate-by-aggregate basis to yield a frequency distribution of aggregates ranging from nm to µm dimensions. Moreover, the light scattering properties of hundreds of thousand aggregates can be collected within minutes. Here we demonstrated that flow cytometry can detect the aggregates arising from as low as 10−8 M amounts of reactants, and that aggregation proceeds by the successive addition of particles to yield a dominant population of aggregates with an average diameter of 1.5 µm.

The above arguments and the data presented herein vindicate the notion that HOCl – when formed in the vicinity of dopamine – will react with this catecholamine to form melanic species that participate in the development of PD. The ease with which aggregates form under the in vitro conditions cited here is a good indicator that these assemblages form in vivo and likely to be plentiful given the relative abundance of dopamine, H2O2, Cl− and myeloperoxidase in the diseased substantia nigra. Myeloperoxidase is expressed in AD [1,43] as well as PD. This enzyme is also delivered to the brain by neutrophils and macrophage following strokes and other injuries [46,59]. The possibility that HOCl is produced in a variety of neurodegenerative disorders and produces species that are both inflammatory and toxic suggests that chlorinative stress contributes significantly to these diseases. Aggregates formed from the reaction of HOCl and catecholamines may be both important remnants and propagators of this stress, and as such, deserve further consideration.

4. Methods

4.1. Materials

The Diff-Quik staining kit was obtained from Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc. (Newark, DE). Primary antibodies were bought from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) whereas the secondary antibodies were supplied in the kits purchased from ImmunoCruz (Santa Cruz, CA) for immunohistochemical staining and the Amersham ECL Western Blotting Analysis System (GE Healthcare). Ladd industries (Burlington, VT) supplied the Epon epoxy resin. Annexin V Alexa Fluor® 488 and propidium iodide were bought from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The ELISA kit for Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNFα was obtained from (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Pre-cast 15% gels were bought from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) and Immbilon PDVF membranes from Millipore (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The Halt protease inhibitor cocktail mix was obtained from Thermo Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). PlasticsOne (Roanoke, VA) supplied the cannulae for microinjection. Duke Standards (0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 µm) were obtained from Thermo Scientific. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

4.2. Animals

Adult male C57/Bl6 mice aged 8–10 weeks old (20–26 g) were housed individually. Mice were acclimated to the institution's Animal Care Facility for 1week prior to surgery and allowed one week to recover post-surgery. All protocols used in this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Winthrop University Hospital and were compliant with NIH guidelines for ethical treatment of animals.

4.3. Preparation of aggregates from the reaction of HOCl and dopamine

Aggregates were prepared in 10 ml lots with dopamine and HOCl in PBS at final concentrations of 20 and 10 mM, respectively. The reactants were allowed to react for 24 h at 22 °C (room temperature) and with 30 rotations per min of the reaction vessels. The HOCl concentration was determined by titration with 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate as described by Jeitner et al. [60]. Particulate material forms in most standing solutions. Consequently the PBS used for these studies was filtered through 0.2 µm pores prior to its use. Precipitates resulting from the aforementioned reaction were collected with centrifugation at 600 ×g for 15 min at 4 °C. Nine mL of the supernatant resulting from this centrifugation was discarded and the remainder used to transfer the aggregates to 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes for centrifugation at 10,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 1.5 mL H2O and centrifuged again. This process was repeated for a total of three centrifugations at 10,000×g. The final pellet was resuspended in artificial cerebrospinal fluid artificial (ACSF: 124 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, 2.7 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 26 mM NaHCO3 and 10 mM D-Glucose), tissue culture medium, or H2O depending on final use of the aggregates. In the case of the elemental analysis and embedding studies, the aggregates were dried by rotary evaporation.

4.4. Elemental analysis

The elemental analyses were performed by Micro-Analysis, Inc. Wilmington, DE 19808.

4.5. Flow cytometric determination of aggregation

Flow cytometry was performed using a BD FACSArray with the flow rate adjusted to 0.5 mL/min and the power of the laser adjusted to the lowest values that distributed the aggregates as a diagonal in a dot plot of Forward Scatter and Side Scatter. A total of 105 light scattering events were analyzed for each sample. The maximum time for sample collection, however, was limited to 200 s to avoid exceeding the sample volume per well. This limit meant that some samples contained less than 105 events. Thus, the data was normalized by dividing the number of events by the collection time for each sample.

The aggregation studies performed at 22 °C utilized 35 mm diameter vessels, typically in six well plates. Each well contained 2 mL of filtered PBS and various combinations of dopamine and HOCl. The reactions were performed at 30 rotations per min and started with the addition of HOCl. Samples of 0.2 mL were removed later for the analysis of 105 events as described above. In some experiments the wells were coated with bovine serum albumin (Cohn Fraction V), which was applied as 5 mg/mL 100 mM carbonate (pH 9.6) solution and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The coated wells were washed three times with filtered PBS immediately prior to the start of the experiments.

The aggregation studies performed at 37 °C utilized 15 mL polypropylene tube. A total of 10 mL filtered PBS containing 20 nM dopamine was rotated at 30 rotations per min following the addition of HOCl to a final concentration of 10 nM. Samples of 0.2 mL were removed later for the analysis of 105 events as described above.

4.6. Spectrophotometry

UV-visible specta for dopamine were collected using a Shimadzu UV – 1601PC spectrometer and UVProbe software (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments Inc., Columbia, MD). All reactions were performed in quartz cuvettes and at 22 °C.

The loss of dopamine fluorescence due to chlorination by HOCl was monitored at an emission wavelength of 315 nm due to excitation at 270 nm (slit width for both wavelengths was 5 nm). These studies were carried out using a Photomultiplier Detection System 710 and the FelixGX software (Photon Technology International, Birmingham, NJ). The reactions were performed in quartz cuvettes and a volume of 2.5 mL at 22 °C.

4.7. 1D 1H-NMR

1D 1H-NMR spectra were obtained on a Varian INOVA 500 MHz spectrometer using the following acquisition parameters: 90° pulse, 32 transients of 32 K data points were collected with a sweep width of 6,000 Hz (12 ppm), 8 sec relaxation delay during which presaturation of the water signal was applied for 2 sec. The total acquisition time was 6 minutes. Data were analyzed using MacNUTS (Acorn Software, Livermore, CA).

4.8. Cell culture

The human monocytic cells THP-1weremaintained in a medium containing RPMI medium, bovine calf serum and 10,000 U/mL Penicillin/Streptomycin (v:v:v, 89:10:1), at between 2.5 × 105 and 106 cells per mL. For each experiment, the cells were diluted at a density of 2.5 × 105 per mL and treated with 100 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate to induce differentiation to phagocytic phenotype. Immediately following the addition of the phorbol ester, the cells were seeded in a volume of 0.5 mL per well of 24 multiwell plates to yield 6.25 × 104 cells per cm2. Forty eight hours later, the medium was removed and replaced with either 0.3 mL fresh medium or medium containing graded amounts of aggregates. After a further 24 h of incubation, 0.25 mL of the medium bathing the cells was removed and assessed for lactate dehydrogenase activity as a measure of cell viability. Care was taken to ensure to not disturb the settled aggregates while removing the medium. In one group of cells treated with medium alone, the medium was removed and replaced with 0.3 mL RIPA buffer to lyse the cells to quantify the intracellular lactate dehydrogenase activity. The activity present in the medium was expressed as a function of the total cellular activity.

Neuroblastoma-derived SH SY5Y cells were maintained in medium composed of F12/MEM (1:1), bovine calf serum and Penicillin/Streptomycin (89:10:1). In preparation for the experiments, the cells were diluted a density of 6.0 × 104 per mL and seeded in a volume of 0.5 mL per well of 24 multiwell plates to yield 3 × 104 cells per cm2. The next day the medium was replaced with medium containing 10 µM retinoic acid to induce cellular differentiation. This treatment was repeated four more times every other day for a total of five treatments over 10 days. The differentiated cells were used between six and 48 h of the last retinoic acid treatment. Retinoic acid was prepared as a 10 mM solution in ethanol and stored at −20 °C.

4.9. Enzymatic assay of cell viability

The release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) into the medium conditioned by cells was used to measure the toxicity of aggregates to THP-1 and SH SY5Y cells. These experiments began with replacement of the culture medium with 0.3 mL fresh medium containing either 0, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10 or 20 × 103 aggregates per µL per well. Twenty four h later 0.25 mL of the medium was removed and combined with 2.5 µL 10% Triton X-100. Two hundred µL of this solution was assayed for LDH activity as described by Beutler [61]. THP-1 and SH SY5Y cells were seeded at 6.25 × 104 and 3 × 104 cells per cm2 and differentiated within 24 h. Since the cell density did not alter significantly during the course of the experiments the seeding densities were used to calculate the aggregates added per cell values.

4.10. Electron microscopy

The electron micrographs of aggregates were prepared using mixtures of dopamine and HOCl (at final concentrations of 20 and 10 mM, respectively) that reacted for at least 24 h at 22 °C and 30 rotations per min. A drop of this mixture was added onto an aluminum block and left undisturbed to allow the aggregates within the drop to settle on to the block surface, after which the excess fluid was wicked off with absorbent filter paper. Another drop was then added and procedure repeated for a total of four drops. The resulting grids were then post-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and visualized on a Zeiss EM 10 transmission electron microscope retro-fitted with an SIA L3C digital camera (SIA, Duluth, GA).

The cells used in these studies were fixed in 4% glutaraldehyde buffered in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, washed with the same buffer, post-fixed in buffered 1% osmium tetroxide, en-bloc stained with a saturated solution of uranyl acetate in 40% ethanol, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, infiltrated with Epon epoxy resin, and embedded in the culture dish. Upon curing, the resin containing the samples was removed from the plastic culture dish, a small piece removed with a jeweler's hacksaw and glued to an aluminum block for en-face thin sectioning. The resulting grids were then post-stained and visualized as described earlier.

4.11. Stereotaxic microinjections

Mice were surgically implanted with guide cannula (Plastics1) following a modified protocol adapted from Gao et al. [62]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg)/xylazine (3.5 mg/kg) i.p. and placed in a Kopf model 962 stereotaxic frame (Tujunga, CA, USA) to enable the placement of 26 gauge stainless steel guide cannulae (Plastics 1, Roanoke, VA) 0.26 mm anterior to bregma, 1.5 mm lateral to the midline and 2.0 mm ventral to the surface of the skull [63]. One week later, 32 gauge internal cannulae were placed into the guide cannulae to enable the injection of either ACSF or 106 aggregates in ACSF. The internal cannulae extended 0.5 mm past the guide to access the striatum. A total of 2 µL was delivered over a 6 min period via a positive displacement microinjector (Tritech Research, Los Angeles) and a 10 µl Hamilton syringe series 7000 (Hamilton, Reno NV). Two minutes later the internal cannulae were removed to prevent backflow and were replaced with dummy cannulae.

4.12. Tissue preparation for histology and Western blotting

Mice were killed by an overdose of euthasol (150 mg/kg) i.p. and the brains excised and bisected. The hemisphere ipsilateral to the cannula was submerged in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline overnight, followed by immersion in 30% sucrose prepared in phosphate buffered saline. This tissue was then sectioned as 40 µm sections and processed for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) staining. The remaining brain hemisphere was homogenized in ice cold lysis buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl, 0.25 M sucrose, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, and 10 µL/mL Halt protease inhibitor cocktail mix (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA)) at 100 mg tissue/mL, centrifuged at 12, 000×g for 20 min at 4 °C, and resulting supernatants analyzed for protein and cytokine content. Protein concentrations were determined with the Bradford assay [64].

4.13. Tyrosine hydroxylase immunocytochemistry

Free floating sections were pretreated with peroxidase block and incubated for 1 h in goat serum using the ImmunoCruz staining system. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with rabbit anti-TH (1:1000). The following day sections were treated with the biotinylated secondary, the HRP-streptavidin complex and visualized with diaminobenzidine. Cells were counted as described previously [30,65] using stereotaxic coordinates defined by Franklin and Paxinos [63]. Stained sections were visualized by light microscopy (Nikon Eclipse TE300, Nikon USA, Melville, NY). Images were taken with the Nikon DS-Ri1 and processed with the NIS-Elements 3.2 (Nikon). The substantia nigra boundaries were established as previously described [30]. Microphotographs for TH neurons were taken at a 40× magnification. Neurons were counted under a light microscope at a magnification of ×400. A neuron was counted if nucleus was visible and one or more clearly defined processes tapered gradually from the cell body. This number was considered to be representative of the number of dopaminergic nigral cells in each animal. The counts were taken of three individual sections from each mouse.

4.14. TNFα ELISA

TNFα levels in the brain tissue and tissue culture medium were measured with the mouse TNFα ELISA kit.

4.15. Statistics

The differences between experimental groups were assessed by ANOVA and any significant differences are indicated by * and ** for p values < 0.05 and 0.01, respectively. Graphical fittings were performed using the SigmaPlot program (Systat Software).

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by RO3-NS074286 and the Theresa Pantnode Santmann Foundation Award. The authors are grateful to Drs. Mark Stecker and Kevin Battaile for their insightful comments on these studies and ensuring manuscript, as well as Shadab Kalim, M.D. and Jim Mathew, B.Sc. for their assistance with the experiments. Mr. M. Patrick, BA help with the preparation of the manuscript is also gratefully acknowledged. The concepts for these studies were developed by TMJ, IG and EJD. TMJ, MK and DB wrote the manuscript. JM and SK determined the mass of chlorinated dopamine a function of time. JM and TMJ conducted the flow cytometric studies. The light microscopy was performed by TMJ while the electron microscopy was done by TP and LR. JM, MK and TMJ performed the LDH release studies while MK assayed the amounts of TNFα in vitro and in vivo. MK was primarily responsible for the design, performance and analysis of the in vivo studies. PAP performed and consulted on the statistical analysis. All other experiments were designed and analyzed by TMJ.

Abbreviations

- ACSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- IF

interfasicular nucleus

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- MT

medial terminal

- PD

Parkinson disease

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest with respect to these studies.

References

- 1.Green PS, Mendez AJ, Jacob JS, Crowley JR, Growdon W, Hyman BT, Heinecke JW. Neuronal expression of myeloperoxidase is increased in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 2004;90:724–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hazen SL, Crowley JR, Mueller DM, Heinecke JW. Mass spectrometric quantification of 3-chlorotyrosine in human tissues with attomole sensitivity: a sensitive and specific marker for myeloperoxidase-catalyzed chlorination at sites of inflammation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1997;23:909–916. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitt AR, Spickett CM. Mass spectrometric analysis of HOCl- and free-radical-induced damage to lipids and proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008;36:1077–1082. doi: 10.1042/BST0361077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker Z, Costa DC, Walker RW, Shaw K, Gacinovic S, Stevens T, Livingston G, Ince P, McKeith IG, Katona CL. Differentiation of dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer's disease using a dopaminergic presynaptic ligand. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2002;73:134–140. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi DK, Pennathur S, Perier C, Tieu K, Teismann P, Wu DC, Jackson-Lewis V, Vila M, Vonsattel JP, Heinecke JW, Przedborski S. Ablation of the inflammatory enzyme myeloperoxidase mitigates features of Parkinson's disease in mice. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:6594–6600. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0970-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Napolitano A, Manini P, d'Ischia M. Oxidation chemistry of catecholamines and neuronal degeneration: an update. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011;18:1832–1845. doi: 10.2174/092986711795496863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sulzer D, Bogulavsky J, Larsen KE, Behr G, Karatekin E, Kleinman MH, Turro N, Krantz D, Edwards RH, Greene LA, Zecca L. Neuromelanin biosynthesis is driven excess cytosolic catecholamines not accumulated by synaptic vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:11869–11874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakamatsu K, Fujikawa K, Zucca FA, Zecca L, Ito S. The structure of neuromelanin as studied by chemical degradative methods. J. Neurochem. 2003;86:1015–1023. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bisaglia M, Filograna R, Beltramini M, Bubacco L. Are dopamine derivatives implicated in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease? Ageing Res. Rev. 2014;13:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leong SL, Cappai R, Barnham KJ, Pham CL. Modulation of alpha-synuclein aggregation by dopamine: a review. Neurochem. Res. 2009;34:1838–1846. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-9986-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zecca L, Wilms H, Geick S, Claasen JH, Brandenburg LO, Holzknecht C, Panizza ML, Zucca FA, Deuschl G, Sievers J, Lucius R. Human neuromelanin induces neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in the rat substantia nigra: implications for Parkinson's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:47–55. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Phillips K, Wielgus AR, Liu J, Albertini A, Zucca FA, Faust R, Qian SY, Miller DS, Chignell CF, Wilson B, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S, Joset D, Loike J, Hong JS, Sulzer D, Zecca L. Neuromelanin activates microglia and induces degeneration of dopaminergic neurons: implications for progression of Parkinson's disease. Neurotox. Res. 2011;19:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9140-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Zecca L, Wilson B, Ren HW, Wang YJ, Wang XM, Hong JS. Human neuromelanin: an endogenous microglial activator for dopaminergic neuron death. Front. Biosci. 2013;5:1–11. doi: 10.2741/e591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halliday GM, Fedorow H, Rickert CH, Gerlach M, Riederer P, Double KL. Evidence for specific phases in the development of human neuromelanin. J. Neural Transm. 2006;113:721–728. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0449-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch EC, Graybiel AM, Agid Y. Selective vulnerability of pigmented dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 1989;126:19–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1989.tb01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kastner A, Hirsch EC, Lejeune O, Javoy-Agid F, Rascol O, Agid Y. Is the vulnerability of neurons in the substantia nigra of patients with Parkinson's disease related their neuromelanin content? J. Neurochem. 1992;59:1080–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb08350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Double KL, Halliday GM. New face of neuromelanin. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 2006:119–123. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-45295-0_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmidt AC, Wang X, Zhu Y, Sombers LA. Carbon nanotube yarn electrodes for enhanced detection of neurotransmitter dynamics in live brain tissue. ACS Nano. 2013:7864–7873. doi: 10.1021/nn402857u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spanos M, Gras-Najjar J, Letchworth JM, Sanford AL, Toups JV, Sombers LA. Quantitation of hydrogen peroxide fluctuations and their modulation of dopamine dynamics in the rat dorsal striatum using fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013;4:782–789. doi: 10.1021/cn4000499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mosharov EV, Gong LW, Khanna B, Sulzer D, Lindau M. Intracellular patch electrochemistry: regulation of cytosolic catecholamines in chromaffin cells. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:5835–5845. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05835.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woods LA, Powell PR, Paxon TL, Ewing AG. Analysis of mammalian cell cytoplasm with electrophoresis in nanometer inner diameter capillaries. Electroanalysis. 2005;17:1192–1197. doi: 10.1002/elan.200403240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lampert MB, Weiss SJ. The chlorinating potential of the human monocyte. Blood. 1983;62:645–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barretoa WJ, Ponzonib S, Sassic P. A Raman and UV–vis study of catecholamines oxidized with Mn(III) Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 1998;55:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang HY, Sun Y, Tang B. Study on fluorescence property of dopamine and determination of dopamine by fluorimetry. Talanta. 2002;57:899–907. doi: 10.1016/s0039-9140(02)00123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demura M, Yoshida T, Hirokawa T, Kumaki Y, Aizawa T, Nitta K, Bitter I, Toth K. Interaction of dopamine and acetylcholine with an amphiphilic resorcinarene receptor in aqueous micelle system. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:1367–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bisaglia M, Mammi S, Bubacco L. Kinetic and structural analysis of the early oxidation products of dopamine: analysis of the interactions with α-synuclein. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:15597–15605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610893200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwao Y, Ishima Y, Yamada J, Noguchi T, Kragh-Hansen U, Mera K, Honda D, Suenaga A, Maruyama T, Otagiri M. Quantitative evaluation of the role of cysteine and methionine residues in the antioxidant activity of human serum albumin using recombinant mutants. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:450–454. doi: 10.1002/iub.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ajit D, Udan ML, Paranjape G, Nichols MR. Amyloid-beta(1–42) fibrillar precursors are optimal for inducing tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in the THP-1 human monocytic cell line. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9011–9021. doi: 10.1021/bi9003777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paranjape GS, Terrill SE, Gouwens LK, Ruck BM, Nichols MR. Amyloidbeta(1–42) protofibrils formed in modified artificial cerebrospinal fluid bind and activate microglia. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:312–322. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9424-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petroske E, Meredith GE, Callen S, Totterdell S, Lau YS. Mouse model of Parkinsonism: a comparison between subacute MPTP and chronic MPTP/probenecid treatment. Neuroscience. 2001;106:589–601. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00295-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laloux C, Derambure P, Houdayer E, Jacquesson JM, Bordet R, Destee A, Monaca C. Effect of dopaminergic substances on sleep/wakefulness in saline- and MPTP-treated mice. J. Sleep Res. 2008;17:101–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Depboylu C, Stricker S, Ghobril JP, Oertel WH, Priller J, Hoglinger GU. Brain-resident microglia predominate over infiltrating myeloid cells in activation, phagocytosis and interaction with T-lymphocytes in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson disease. Exp. Neurol. 2012;238:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imai Y, Kohsaka S. Intracellular signaling in M-CSF-induced microglia activation: role of Iba1. Glia. 2002;40:164–174. doi: 10.1002/glia.10149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozgen U, Soylu H, Onal SC, Mizrak B, Turkoz Y, Kutlu NO, Kocak A, Ozcan C, Koltuksuz U, Erten SF, Akcin U. Potential salvage therapy for accidental intrathecal vincristine administration: a preliminary experimental study. Chemotherapy. 2000;46:322–326. doi: 10.1159/000007305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yap YW, Whiteman M, Cheung NS. Chlorinative stress: an under appreciated mediator of neurodegeneration? Cell. Signal. 2007;19:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hawkins CL, Pattison DI, Davies MJ. Hypochlorite-induced oxidation of amino acids, peptides and proteins. Amino Acids. 2003;25:259–274. doi: 10.1007/s00726-003-0016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klebanoff SJ, Kettle AJ, Rosen H, Winterbourn CC, Nauseef WM. Myeloperoxidase: a front-line defender against phagocytosed microorganisms. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013;93:185–198. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0712349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whiteman M, Cheung NS, Zhu YZ, Chu SH, Siau JL, Wong BS, Armstrong JS, Moore PK. Hydrogen sulphide: a novel inhibitor of hypochlorous acid-mediated oxidative damage in the brain? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;326:794–798. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang ML, Klaidman LK, Adams JD., Jr The effects of oxidative stress on in vivo brain GSH turnover in young and mature mice. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 1997;30:187–197. doi: 10.1007/BF02815097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu RM. Down-regulation of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase regulatory subunit gene expression in rat brain tissue during aging. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002;68:344–351. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eto K, Asada T, Arima K, Makifuchi T, Kimura H. Brain hydrogen sulfide is severely decreased in Alzheimer's disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;293:1485–1488. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00422-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Omiatek DM, Bressler AJ, Cans AS, Andrews AM, Heien ML, Ewing AG. The real catecholamine content of secretory vesicles in the CNS revealed by electrochemical cytometry. Sci. Reports. 2013;3:1447. doi: 10.1038/srep01447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reynolds WF, Rhees J, Maciejewski D, Paladino T, Sieburg H, Maki RA, Masliah E. Myeloperoxidase polymorphism is associated with gender specific risk for Alzheimer's disease. Exp. Neurol. 1999;155:31–41. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maki RA, Tyurin VA, Lyon RC, Hamilton RL, DeKosky ST, Kagan VE, Reynolds WF. Aberrant expression of myeloperoxidase in astrocytes promotes phospholipid oxidation and memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:3158–3169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807731200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones P, Gardner L, Menage J, Williams GT, Roberts S. Intervertebral disc cells as competent phagocytes in vitro: implications for cell death in disc degeneration. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2008;10:R86. doi: 10.1186/ar2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jefferson AL, Massaro JM, Wolf PA, Seshadri S, Au R, Vasan RS, Larson MG, Meigs JB, Keaney JF, Jr, Lipinska I, Kathiresan S, Benjamin EJ, DeCarli C. Inflammatory biomarkers are associated with total brain volume: the Framingham Heart Study. Neurology. 2007;68:1032–1038. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000257815.20548.df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryu JK, Tran KC, McLarnon JG. Depletion of neutrophils reduces neuronal degeneration and inflammatory responses induced by quinolinic acid in vivo. Glia. 2007;55:439–451. doi: 10.1002/glia.20479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang CY, Song MJ, Jeon SB, Yoon HJ, Lee DK, Kim IH, Suk K, Choi DK, Park EJ. Dual functionality of myeloperoxidase in rotenone-exposed brain-resident immune cells. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;179:964–979. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koopman WJ, Nijtmans LG, Dieteren CE, Roestenberg P, Valsecchi F, Smeitink JA, Willems PH. Mammalian mitochondrial complex I: biogenesis, regulation, and reactive oxygen species generation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010;12:1431–1470. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klebanoff SJ. Myeloperoxidase: friend and foe. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2005;77:598–625. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1204697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deborde M, von Gunten U. Reactions of chlorine with inorganic and organic compounds during water treatment-Kinetics and mechanisms: a critical review. Water Res. 2008;42:13–51. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeitner TM, Xu H, Gibson GE. Inhibition of the alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex by the myeloperoxidase products, hypochlorous acid and mono-N-chloramine. J. Neurochem. 2005;92:302–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peskin AV, Winterbourn CC. Taurine chloramine is more selective than hypochlorous acid at targeting critical cysteines and inactivating creatine kinase and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;40:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Curtis MP, Hicks AJ, Neidigh JW. Kinetics of 3-chlorotyrosine formation and loss due to hypochlorous acid and chloramines. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011;24:418–428. doi: 10.1021/tx100380d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murphy BP, Schluz TM. Synthesis and physical properties of 5,6-dihydroxyindole. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:2790–2791. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bush WD, Garguilo J, Zucca FA, Albertini A, Zecca L, Edwards GS, Nemanich RJ, Simon JD. The surface oxidation potential of human neuromelanin reveals a spherical architecture with a pheomelanin core and a eumelanin surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:14785–14789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604010103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zecca L, Bellei C, Costi P, Albertini A, Monzani E, Casella L, Gallorini M, Bergamaschi L, Moscatelli A, Turro NJ, Eisner M, Crippa PR, Ito S, Wakamatsu K, Bush WD, Ward WC, Simon JD, Zucca FA. New melanic pigments in the human brain that accumulate in aging and block environmental toxic metals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:17567–17572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808768105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carraher CE. Introduction to polymer chemistry. 2nd. Boca Raton, Fl: CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Breckwoldt MO, Chen JW, Stangenberg L, Aikawa E, Rodriguez E, Qiu S, Moskowitz MA, Weissleder R. Tracking the inflammatory response in stroke in vivo by sensing the enzyme myeloperoxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:18584–18589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803945105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jeitner TM, Kalogiannis M, Mathew J. Preparation of 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate for the routine determination of reagent hypochlorous acid concentrations. Anal. Biochem. 2013;441:180–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beutler E. Red cell metabolism. New York: Churhill Livingstone; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gao HM, Kotzbauer PT, Uryu K, Leight S, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Neuroinflammation and oxidation/nitration of alpha-synuclein linked to dopaminergic neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:7687–7698. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0143-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Third. New York: Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharma SK, Babitch JA. Application of Bradford's protein assay to chick brain subcellular fractions. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods. 1980;2:247–250. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(80)90039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Laloux C, Derambure P, Kreisler A, Houdayer E, Brueziere S, Bordet R, Destee A, Monaca C. MPTP-treated mice: long-lasting loss of nigral TH-ir neurons but not paradoxical sleep alterations. Exp. Brain Res. 2008;186:635–642. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1268-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]