Abstract

Background:

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is one of the common emergencies encountered in the emergency department (ED) of any hospital. Although several studies have reported the predictors of CPR outcome in general, there are limited data from the EDs in India.

Materials and Methods:

This retrospective study included all patients above 18 years with SCA who were resuscitated in the ED of a tertiary care hospital with an annual census of 60,000 patients between August 2014 and July 2015. A modified Utstein template was used for data collection. Factors relating to a sustained return of spontaneous circulation and mortality were analyzed using descriptive analytic statistics and logistic regressions.

Results:

The study cohort contained 254 patients, with a male predominance (64.6%). Median age was 55 (interquartile range: 42–64) years. Majority were in-hospital cardiac arrests (73.6%). Only 7.4% (5/67) of the out-of-hospital cardiac arrests received bystander resuscitation before ED arrival. The initial documented rhythm was pulseless electrical activity (PEA)/asystole in the majority (76%) of cases while shockable rhythms pulseless ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation were noted in only 8% (21/254) of cases. Overall ED-SCA survival to hospital admission was 29.5% and survival to discharge was 9.9%. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed age ≥65 years (odds ratio [OR]: 12.33; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.38–109.59; P = 0.02) and total duration of CPR >10 min (OR: 5.42; 95% CI: 1.15–25.5; P = 0.03) to be independent predictors of mortality.

Conclusion:

SCA in the ED is being increasingly seen in younger age groups. Despite advances in resuscitation medicine, survival rates of both in-hospital and out-of-hospital SCA remain poor. There exists a great need for improving prehospital care as well as control of risk factors to decrease the incidence and improve the outcome of SCA.

Keywords: Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, emergency department, sudden cardiac arrest, survival

INTRODUCTION

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) is the sudden cessation of cardiac activity leading to unresponsiveness in patients with or without cardiac disease. If corrective measures are not instituted rapidly, the outcome is fatal and is a common presentation in the ED. In the general population, the incidence of SCA ranges from 50 to 100/100,000 and accounts for 15%–20% of all deaths.[1] In some studies, nearly one out of four patients presenting to the ED had an SCA.[2] It has been established that success after cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is determined by various factors including patient characteristics, time of onset of basic and advanced life support, and continuing facilities.[3] It has also been shown that in-hospital setting SCA and related CPR have better survival outcomes than out-of-hospital setting SCA (7.4%–27.0% vs. 2.0%–10.0%).[4,5,6] Survival rates have been reported to be better in patients who have an initial arrest rhythm that is shockable and in those with a primary underlying disease of cardiac origin than noncardiac origin.[7] However, most of the studies done on SCA are hospital-based studies; there are not many studies exploring the association between the causes and outcomes in India. Hence, this study was done with the largest cohort of SCAs in the ED of a large tertiary care hospital in India to describe the profile of cardiac arrest patients and the associated factors of outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective cohort study was carried out in the adult ED of a 2700-bedded medical college hospital in South India. The adult ED is equipped with 45 beds with an average of 200 adult patients per day including all trauma and adult emergencies, except patients with chest pain of cardiac origin, which is managed by a Chest Pain Unit under the Department of Cardiology. An SCA was defined as the absence of a pulse in an unconscious individual with no respiration or with agonal breaths only. A “code blue” alarm is triggered off for all SCAs in the ED. The resuscitation room consultant or senior registrar attends to immediately at all times of the day and heads the resuscitation team. The American Heart Association's Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) protocol is adhered to. All the ED consultants and registrars are ACLS certified, and most of the members of the team are basic life support (BLS) certified.

All adult patients >18 years old who had an SCA and underwent CPR in the ED between August 2014 and July 2015 were included in the study. Patients who were brought and declared dead on arrival and those with a standing “do not resuscitate” order with prior consent were excluded from the study. A person was declared dead on arrival if there is no electrical activity of the heart and pupils are dilated or if there are signs of rigor mortis. The patients were identified using the cardiac arrest audit register maintained by the ED. A retrospective chart review was performed on all the above said patients using the hospital's electronic medical database. The following data were extracted: demographic details, first documented rhythm, duration and details of CPR, return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), outcome in ED, in-hospital outcome, and the cerebral performance category (CPC) score before discharge from the hospital. The probable etiology of SCA was judged by the team leaders and the investigating team by analyzing the circumstances leading to the event and the patient's medical history. The predictors of sustained ROSC and predictors of mortality were analyzed.

Statistical methods

The clinical research form was made based on the modified Utstein template. Data were analyzed using STATA 12.1 for Windows (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) software. Mean (standard deviation) was calculated for the continuous variables, and t-test or Mann–Whitney test was used to test the significance. The categorical variables were expressed in proportion, and Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used to compare dichotomous variables. For all tests, a two-sided P = 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. Factors determining sustainability of ROSC and mortality were analyzed by univariate analysis and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. The variables that were clinically relevant were considered for inclusion in the final multivariate models. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed using backward stepwise method. Predictability of the multivariate analysis model (goodness of fit) is 33%.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Christian Medical College, Vellore (IRB Min No: 9292; dated 21/01/2015), and patient confidentiality was maintained using unique identifiers and by password protected data entry software with restricted users.

RESULTS

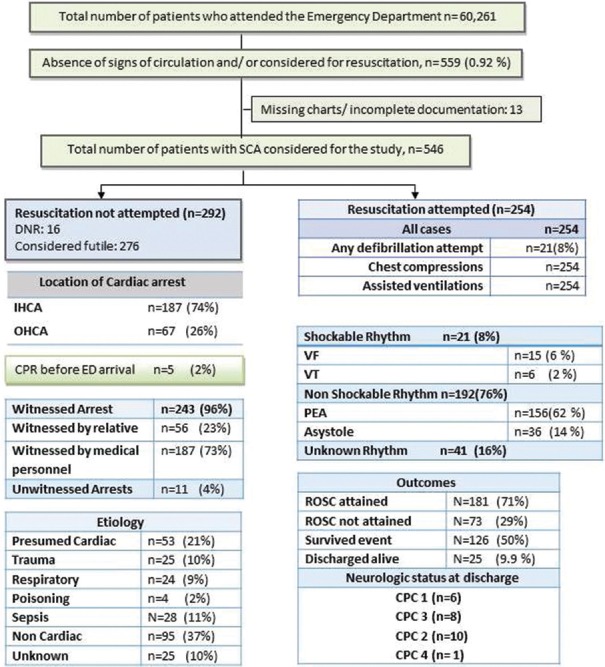

During the study period, a total of 60,261 patients attended the ED among who 559 patients were brought with signs of absent circulation. Details of 13 patients were not available because of missing charts or incomplete documentation. Two hundred and ninety-two patients were either declared as brought dead on arrival or had a standing “do not resuscitate” order with prior consent and hence were excluded from the analysis. The study cohort contained 254 patients who satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Baseline characteristics and details of cardiac arrest

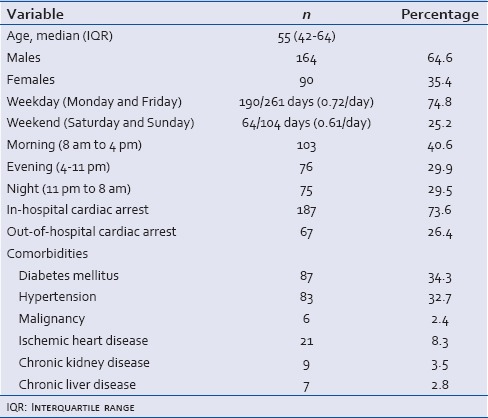

The study revealed a predominantly male population (64.6%) among the recruited patients. The median age was 55 (interquartile range [IQR]: 42–64) years. Nearly one-third (31%) of the patients were <45 years old. The number of SCA did not differ much between weekdays and weekends (0.72/day vs. 0.61/day; P = 0.27). There were more cardiac arrests during the morning shifts (40.6%) as compared to the evening (29.9%) or night (29.5%) shifts. Majority (88.9%) of the patients had at least one comorbid condition while 29.1% had two or more comorbidities. Diabetes mellitus (34.3%) and hypertension (32.7%) were the most common comorbidities [Table 1].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (n=254)

Majority were in-hospital cardiac arrests (73.6%) with only 26.4% (67/254) being out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. Five of the 67 out-of-hospital cardiac arrests received bystander resuscitation before ED arrival. At arrival in the ED, 50.3% (128/254) of patients were found to be conscious. These patients had a cardiac arrest after ED arrival during the period of fluid resuscitation or airway, breathing, circulation stabilization. Most of the cardiac arrests were witnessed (96%), with medical personnel (73%) and relatives (23%) being the most common witnesses. The common presumed etiologies were noncardiac including sepsis, hypovolemia, hyperkalemia (48%), cardiac including ischemia, infarction, and congestive cardiac failure (21%), trauma (10%), respiratory (9%), poisonings (2%), and unknown causes (10%) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Modified Utstein template

Details of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and outcome

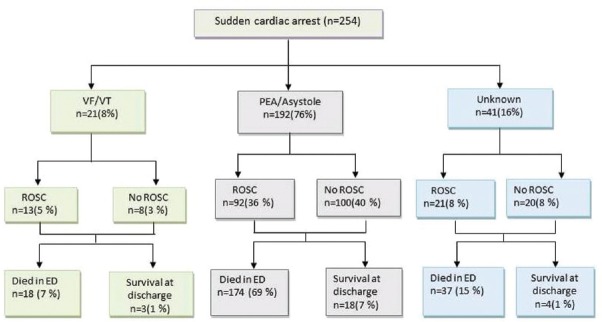

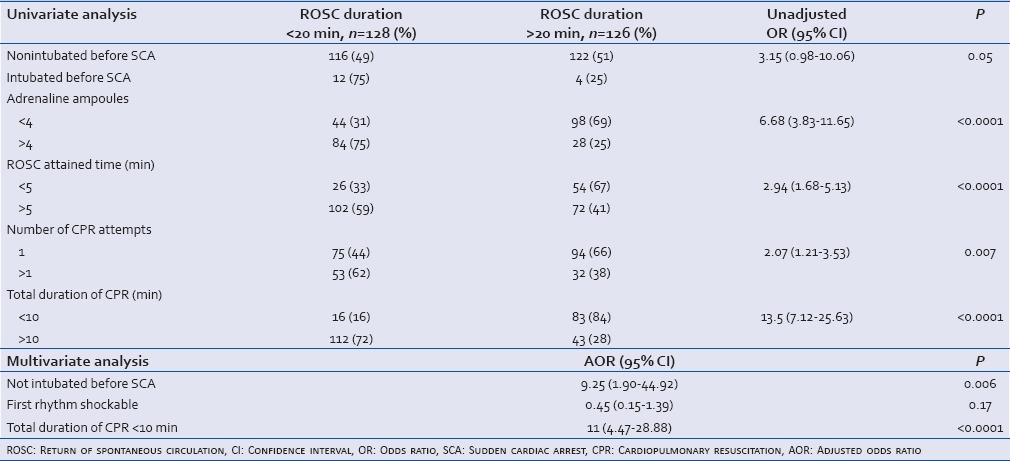

The initial documented rhythm was pulseless electrical activity (PEA)/asystole in the majority (76%) of cases while shockable rhythms (pulseless ventricular tachycardia [VT]/ventricular fibrillation [VF]) were noted in only 8% (21/254) of cases [Figure 2]. There was no observed initial rhythm in 16% (41/254) of cases. After CPR, ROSC was attained in 71% (181/254) of patients but was sustained for >20 min in only 49.6% (126/254) of patients. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed the total duration of CPR >10 min (11; 95% CI: 4.47–28.88; P < 0.0001) and intubation before ED arrival (9.25; 95% CI: 1.90–44.92; P = 0.006) to be independent predictors of an ill sustained ROSC [Table 2].

Figure 2.

Details of return of spontaneous circulation and outcome from emergency department and hospital

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with sustained return of spontaneous circulation (>20 min)

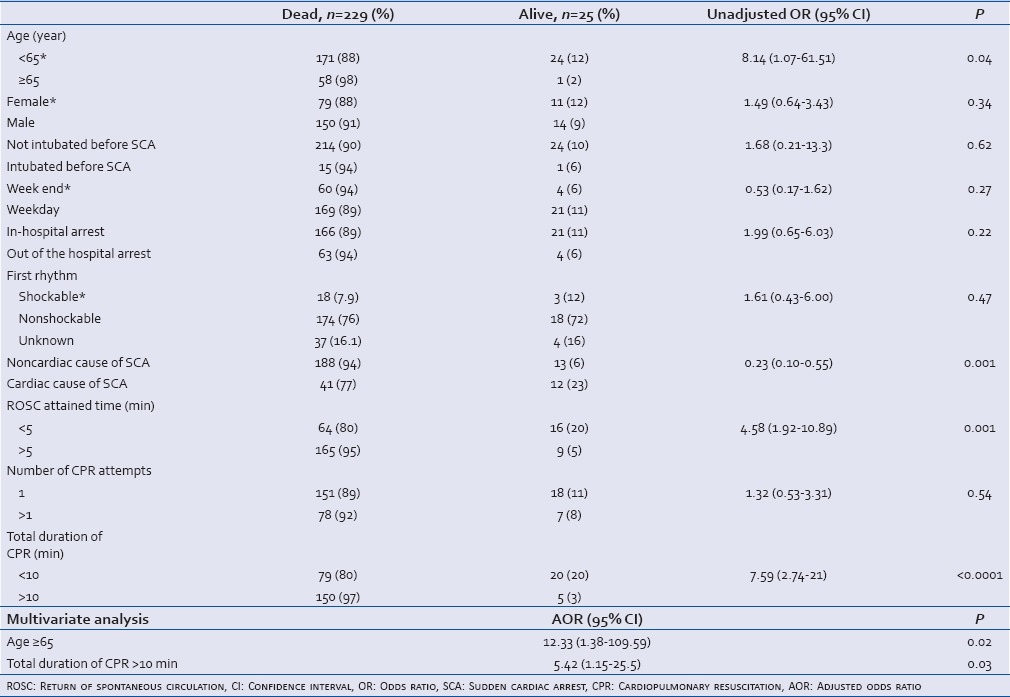

After initial CPR, 50% of the patients (126/254) survived the event; however, further 51 patients either died in the ED due to subsequent cardiac arrests or the relatives left against medical advice due to poor prognosis. A total of 75 patients (29.5%) were admitted to the medical or surgical intensive care units of our hospital after ED survival. The overall SCA survival to discharge from the hospital rate was 9.9%. At hospital discharge, CPC scores of 1, 2, 3, and 4 were seen in 6, 10, 8, and 1 patients, respectively. Univariate analysis showed age ≥65 years (8.14; 95% CI: 1.07–61.51; P = 0.04), total duration of CPR >10 min (7.59; 95% CI: 2.74–21; P < 0.0001), and ROSC attained time >5 min (4.58; 95% CI: 1.92–10.89; P = 0.001) to be significant predictors of mortality. Male/female sex, intubation before the SCA, day of the week, out-of-hospital arrest, and presence of a shockable rhythm did not seem to have any significant correlation with mortality. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed age ≥65 years (odds ratio [OR]: 12.33; 95% CI: 1.38–109.59; P = 0.02) and total duration of CPR >10 min (OR: 5.42; 95% CI: 1.15–25.5; P = 0.03) to be independent predictors of mortality [Table 3].

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with mortality

DISCUSSION

SCA is one of the leading causes of mortality in the ED. Despite advances in resuscitation medicine, the survival rates are low even in developed countries. This is till date the largest study done in India on SCA in the ED aimed at assessing the outcome. The assessment of sudden cardiac deaths has always been difficult to accomplish as this is a dynamic event that occurs in the general population in an unpredictable manner. The most accepted definition is sudden and unexpected death within an hour of onset of symptom.[8]

SCA is more common in the elderly as the risk factors increase with increasing age. The median age of 55 years (IQR: 42–64) in our study is a cause for concern as it is lesser than the average age reported in studies from Thailand, Middle East, and the West.[4,9,10] Rajaram et al. in 1999 reported 52% of patients being below 60 years of age while our study showed that 62% of our patients were below the age of 60 and nearly a third were lesser than 45 years of age.[6] This shows that SCA is increasingly becoming common in the middle age groups. The present day urban lifestyle with its contributing psychosocial factors along with factors such as low educational levels, greater alcohol consumption, obesity, and cigarette smoking has been implicated in the increased risk of SCA.[11,12] Hence, the need for early initiation of lifestyle modifications and early screening for risk factors for SCA.

In our study, 76% of patients had a nonshockable rhythm while only 8% had a shockable rhythm. Most previous studies have shown shockable rhythms to be the predominant initial rhythms during an SCA.[12,13] In our study, among survivors, 72% had a nonshockable rhythm compared to only 12% (3 patients) with a shockable rhythm. This is in contrast to many other studies where the majority of survivors had a shockable rhythm.[2,3,4] Asystole/PEA is considered an agonal rhythm and has seldom been showed to be associated with a successful outcome as compared to VF/VT as the initial rhythm.[7] The predominance of nonshockable rhythms in our study can be explained by the fact that in our study, only 21% of the patients had a presumed cardiac etiology. This is because most patients with chest pain are attended to by the chest pain unit directly and hence were not included in our study. In the studies that showed VF/VT as the predominant initial rhythm, cardiac etiology of SCA comprised 56%–80% of the cases.[2,6,14]

Our ED SCA survival to hospital admission rate of 29.5% was slightly better than the survival rates described by Johnson et al. (26.2%) but much lesser compared to the rate described by Ozcan et al. (58.8%).[2,7] The overall survival to discharge rate in our study was 9.9% with survival rates varying from 11% for in-hospital cardiac arrests to 6% for out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. These results are consistent with findings of other studies where the in-hospital survival rates varied from 7.4% to 27.0% and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival rates varied from 2.0% to 10.0%.[4,5] Among in-hospital SCA, those occurring the coronary care unit or ED are expected to have better outcomes.[7] What is of concern is the fact that despite significant advances in medical care, training, and technology, outcomes after CPR have not changed much in the last 3–4 decades, especially for SCA occurring in the hospital.[11,14]

Many factors are known to influence the outcome of CPR: age, prearrest hypotension, witnessed cardiopulmonary arrest, interval between resuscitation and arrest, early initiation of ACLS, including shock delivery, initial rhythm, intubation and vasopressor use, premorbidities such as sepsis, malignancy, diabetes mellitus, and renal disease.[2,3,4,15,16] Our study showed age ≥65 years and longer duration of CPR to be significant predictors of mortality. In our study, intubation before SCA was associated with an ill sustained ROSC but has no association with mortality. Most of these patients were intubated elsewhere and referred to our hospital for further management. This may reflect the extremely poor prehospital transport service that exists in most parts of India.[17,18] Many ambulance services in India lack basic equipment for ventilation and availability of trained paramedical personnel is extremely rare and this may contribute to significant deterioration of the medical condition of the patients during transfer.[17,18] This may be the reason why early intubation and referral from other secondary hospitals did not seem to have any survival benefit in this group of patients.

The fact that only 7.4% (5/67) of the out-of-hospital cardiac arrests received bystander resuscitation before ED arrival also shows the lack of awareness and grossly inadequate training in BLS in the community. This is not a significant improvement from the 4.4% bystander resuscitation rate reported from India in 1999.[6] This emphasizes the urgent need to initiate basic medical emergencies awareness programs in the society.

Limitations

A major limitation of this study is the retrospective study design. Missing or incomplete data (2.3%) were other limitations. The presence of a separate chest pain unit in our hospital resulted in some patients with SCA due to cardiac etiology being excluded from the analysis. The presumed etiology was determined based on the history and the immediate circumstances leading to the event and hence was mostly based on consensus between the investigators. In many cases, there was no investigation-proven or autopsy-proven diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

SCA in the ED is being increasingly seen in a younger age group. Despite advances in resuscitation medicine, survival rates of both in-hospital and out-of-hospital SCA remain poor. There exists a great need for improving prehospital care, training in BLS in the community, and control of risk factors to decrease the incidence and improve the outcome of SCA.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deo R, Albert CM. Epidemiology and genetics of sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 2012;125:620–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.023838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson NJ, Salhi RA, Abella BS, Neumar RW, Gaieski DF, Carr BG. Emergency department factors associated with survival after sudden cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2013;84:292–7. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beuret P, Feihl F, Vogt P, Perret A, Romand JA, Perret C. Cardiac arrest: Prognostic factors and outcome at one year. Resuscitation. 1993;25:171–9. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(93)90093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sittichanbuncha Y, Prachanukool T, Sawanyawisuth K. A 6-year experience of CPR outcomes in an emergency department in Thailand. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2013;9:377–81. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S50981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairbanks RJ, Shah MN, Lerner EB, Ilangovan K, Pennington EC, Schneider SM. Epidemiology and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Rochester, New York. Resuscitation. 2007;72:415–24. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.06.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajaram R, Rajagopalan RE, Pai M, Mahendran S. Survival after cardiopulmonary resuscitation in an urban Indian hospital. Natl Med J India. 1999;12:51–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozcan V, Demircan C, Engindenizi Z, Turanoglu G, Ozdemir F, Ocak O, et al. Analysis of the outcomes of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in an emergency department. Acta Cardiol. 2005;60:581–7. doi: 10.2143/AC.60.6.2004931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myerburg RJ, Castellanos A. Cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Braunwald E, editors. Braunwald's Heart Disease. A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. pp. 865–908. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairbanks RJ, Bisantz AM, Sunm M. Emergency department communication links and patterns. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:396–406. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saghafinia M, Motamedi MH, Piryaie M, Rafati H, Saghafi A, Jalali A, et al. Survival after in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a major referral center. Saudi J Anaesth. 2010;4:68–71. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.65131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zipes DP, Wellens HJ. Sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 1998;98:2334–51. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.21.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chugh SS, Reinier K, Teodorescu C, Evanado A, Kehr E, Al Samara M, et al. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death: Clinical and research implications. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;51:213–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmgren C, Bergfeldt L, Edvardsson N, Karlsson T, Lindqvist J, Silfverstolpe J, et al. Analysis of initial rhythm, witnessed status and delay to treatment among survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Sweden. Heart. 2010;96:1826–30. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.198325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider AP, 2nd, Nelson DJ, Brown DD. In-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A 30-year review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1993;6:91–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasson C, Rogers MA, Dahl J, Kellermann AL. Predictors of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:63–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.889576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honnekeri BS, Lokhandwala D, Panicker GK, Lokhandwala Y. Sudden cardiac death in India: A growing concern. J Assoc Physicians India. 2014;62:36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramanujam P, Aschkenasy M. Identifying the need for pre-hospital and emergency care in the developing world: A case study in Chennai, India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2007;55:491–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy N, Murlidhar V, Chowdhury R, Patil SB, Supe PA, Vaishnav PD, et al. Where there are no emergency medical services-prehospital care for the injured in Mumbai, India. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2010;25:145–51. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00007883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]