Abstract

Six2cre-mediated deletion of Frs2α (Six2creFrs2αKO), a major fibroblast growth factor receptor (Fgfr) docking protein in mouse nephron progenitors results in perinatal renal hypoplasia; however, postnatal Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys develop cysts. We sought to determine the pathogenesis of Six2creFrs2αKO cyst formation. We performed histological assays, Western blots, and quantitative PCR (qPCR). While embryonic day (E) 18.5 Six2Frs2αKO kidneys were hypoplastic and not cystic, postnatal day (P) 7 mutants had proximal tubular-derived cysts that nearly replaced the renal parenchyma by P21. Mutants had high proximal tubular proliferation rates and interstitial fibrosis, similar to known polycystic kidney disease (PKD) models. Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys also had upregulation of Wnt/βcatenin signaling, macrophage infiltration and chemokine production (e.g. ectopic Ccl2 in non-dilated proximal tubules), and augmented hedgehog signaling, features also seen in other PKD models. We saw increased Gli1 (hedgehog readout) in postnatal Six2creFrs2αKO interstitium and ectopic sonic hedgehog (Shh) in subsets of non-dilated P7 mutant proximal tubules (likely driving the stromal Gli expression). As ectopic tubular Shh and Ccl2 expression is seen after acute kidney injury (AKI), we interrogated another bone fide AKI marker, Kim1 and noted ectopic expression in P7 non-dilated proximal tubules. These observations suggest that aberrantly activated “AKI” pathways may drive pathogenesis in PKD.

Fgfr signaling is mediated by docking proteins, including fibroblast growth factor receptor substrate 2α (Frs2α)1. Upon Fgf ligand binding and receptor dimerization, Frs2α becomes phosphorylated, leading to activation of Erk, Akt, and alternative forms of protein kinase C1. While global deletion of Fgfr1, Fgfr2 or Frs2α in mice is early embryonic lethal, many investigators have shown critical roles for this pathway in renal development using ligand and/or conditional receptor knockouts1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Recently, our laboratory generated an allelic series of Six2cre-mediated conditional knockout mice that remove Fgfr(s) and/or Frs2α expression and function specifically in the nephron progenitor population10. Nephron progenitors, expressing the transcription factor Six2, give rise to glomeruli and all nephron tubular segments including proximal convoluted tubules. Six2cre-mediated deletion of both Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 in mice resulted in early depletion of nephron progenitors due primarily to excessive apoptosis and loss of stemness markers such as Cited 1; these mice developed severe renal cystic dysplasia resulting in perinatal lethality. Other mutants with ablation of Frs2α expression/activity, including Six2cre;Frs2αfl/fl (Six2creFrs2αKO), had a later loss of nephron progenitors at E14.5. Frs2α-deficient nephron progenitors were found to have lower Cited 1 expression and increased notch activity. While surviving progenitors made nephrons leading to hypoplastic kidneys by E18.5, Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys became very cystic postnatally leading to death by 6 weeks of age.

Ciliopathy is a key feature of renal cystogenesis11,12,13. In humans with, and animal models of polycystic cystic kidney disease (PKD), causative mutations have often been identified in genes encoding for proteins that associate with primary cilia and/or that are critical for ciliary assembly and/or intraflagellar transport14,15,16,17,18,19. While these ciliary-associated proteins are often predicted act in concert, the exact role of primary ciliary dysfunction remains unknown and/or controversial. Given the association of hedgehog signaling proteins with cilia, aberrant activation of this pathway is often thought to indicate ciliary dysfunction in PKD models12. Moreover, there are renal cystogenesis models in which causative mutations encode for proteins with no known ciliary association20,21,22,23,24. Thus, while cilia are a central feature of renal cystogenesis, there are likely other critical factors driving cyst formation.

Other common features of PKD models are dysregulation of β-catenin signaling and inflammation, including excessive chemokine production and macrophage infiltration25,26,27,28,29,30. Mouse models of PKD with mutations in KIf3α (a gene encoding for a protein necessary for ciliary formation), or Pkd1 (leading cause of human autosomal dominant PKD) develop excessive tubular β-catenin accumulation31,32. Transgenic mice with activating mutations in β-catenin have been shown to develop a PKD phenotype27. Infiltrating macrophages have often been identified in PKD models and macrophage depletion often results in amelioration of cyst growth29. Chemokines, such as Ccl2 (major chemotactic factor for macrophages) and Tnfα (secreted by activated macrophages) have been detected in PKD models and appear to have causative roles28,33,34.

In this study, we sought to determine whether Six2creFrs2αKO mice shared features common to other PKD models. The mutants developed cysts derived from proximal tubules that were hyperproliferative and displayed interstitial fibrosis, similar to other models. Mutant kidneys also had upregulated Wnt/β-catenin expression, macrophage and chemokine production and excessive hedgehog activity, like other models. Given the latter and that Fgf signaling in other contexts regulates cilia formation35 we were surprised that ciliary formation appeared intact. Moreover, we noted that subsets of non-dilated proximal tubules in young postnatal mutants ectopically expressed Shh, Ccl2, and Kim1, all known to be activated by acute kidney injury. Thus, aberrantly activated “AKI” pathways may drive renal pathogenesis in PKD.

Results

Cystogenesis in Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys

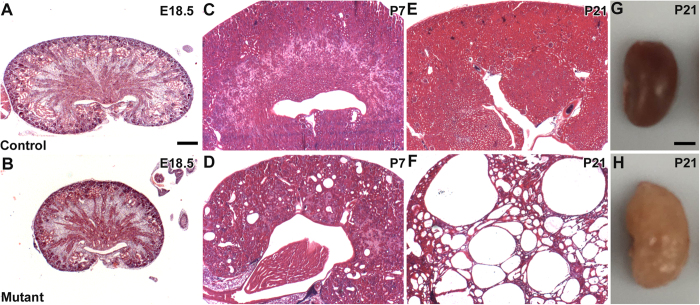

We sought to characterize the origin and progression of cystogenesis in Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys. Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections reveal that E18.5 mutant kidneys are hypoplastic but non-cystic compared to controls (Fig. 1A,B). In contrast, P7 Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys had numerous small cysts (Fig. 1C,D), and P21 mutant parenchyma was almost completely replaced by cysts of varying size (Fig. 1E–H). Morphometric analysis of Six2creFrs2αKO mice showed reduction in the kidney weight (KW) and body weight (BW) with unaltered KW/BW ratio versus controls (Supplementary Fig. 1A–C). Six2creFrs2αKO mice showed marked upregulation in plasma blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels in comparison to controls indicating impaired kidney function in mutants. (Supplementary Fig. 1D). Immunostaining in P7 and P21 Six2FRSK2αKO kidneys with LTL and DBA, proximal tubule and collecting duct markers, respectively, revealed that virtually all of the Six2creFRS2αKO cysts were LTL positive/proximal tubule-derived (Supplementary Fig. 2 and not shown).

Figure 1. Tissue sections and gross images show progressive cyst formation in Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys.

(A–F,H,E) Stained sections of control (A,C,E) and Six2creFRS2αKO (B,D,F) kidneys show that the mutants are hypoplastic at E18.5 (A vs. B), develop small cysts dispersed in normal appearing parenchyma at P7 (C vs. D), and have cysts replacing most of the parenchyma by P21 (E vs. F). (G,H). Dissected kidneys from P21 control (G) and Six2creFRS2αKO (H) mice show that the mutant kidneys are enlarged and have multiple fluid-filled cysts. (A–F) scale bar = 200 μm; G, H scale bar = 0.25 cm.

Epithelial cell proliferation, apoptosis, and interstitial fibrosis in Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys

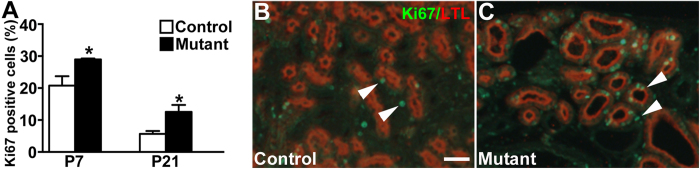

We next assessed Six2creFrs2αKO mice for increased epithelial cell proliferation, apoptosis, and interstitial fibrosis, other prominent features in PKD15,36,37,38,39,40. Co-staining of kidney sections with LTL, and the proliferation marker, Ki67, revealed increases in mutant proximal tubular cell proliferation rates at both P7 and P21 versus controls (Fig. 2 and not shown). TUNEL staining shows apparent increases in P21 mutant proximal tubular-derived cells vs. controls; however, the overall number of TUNEL positive cells was relatively low in both (Supplementary Fig. 3). Quantitative PCR also revealed significant increases in fibrotic markers, αSMA, Col1a (collagen 1a), and Col3a in E18.5, P7, and P21 mutants that worsened with age versus controls (Fig. 3A). Immunofluorescence revealed prominent αSMA staining in an expanded stromal compartment in P7 and P21 Six2creFrs2αKO mice versus controls, which had staining confined to peri-arteriolar smooth muscle (Fig. 3B–E). Trichrome-stained sections from P21 Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys showed increased collagen deposition numbers of interstitial cells versus controls (Fig. 3F,G). Together, these data show that postnatal Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys share histological features found in other PKD models.

Figure 2. Six2creFrs2αKO proximal tubular-derived epithelia have increased proliferation.

(A) Graph reveals increased percentages of Ki67 positive-nuclei in P7 and P21 mutant LTL positive tubular epithelial cells versus littermate controls (*p < 0.05). (B,C) Representative sections from a P21 control (B) and mutant (C) showing increased numbers of Ki67-positive nuclei (green, arrowheads) in LTL-positive cells (red) in the latter versus the former (DAPI staining is not shown). (B,C) scale bar = 25 μm.

Figure 3. qPCR and staining reveals increased interstitial fibrosis in postnatal Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys.

(A) Graphs of qPCR assays show increases in expression of fibrotic markers αSMA, Col1a, and Col3a in E18.5, P7 and P21 mutant kidneys versus controls. (*p < 0.05). (B–E) Representative immunofluorescence images for αSMA (SMA, red) and DAPI (blue) reveal that αSMA expression is mostly in peri-arteriolar smooth muscle in controls (arrowheads) at P7 (B) and P21 (C), whereas it is strongly expressed in the interstitium of mutants (concave arrowheads) at P7 (D) and P21 (E). (F,G) Representative Trichrome-stained sections (TRICH) shows no fibrosis in P21 controls (F), but significant collagen deposition in the expanded interstitium of the mutants (G, asterisks). (B–E) scale bar = 25 μm; (F,G) scale bar = 25 μm.

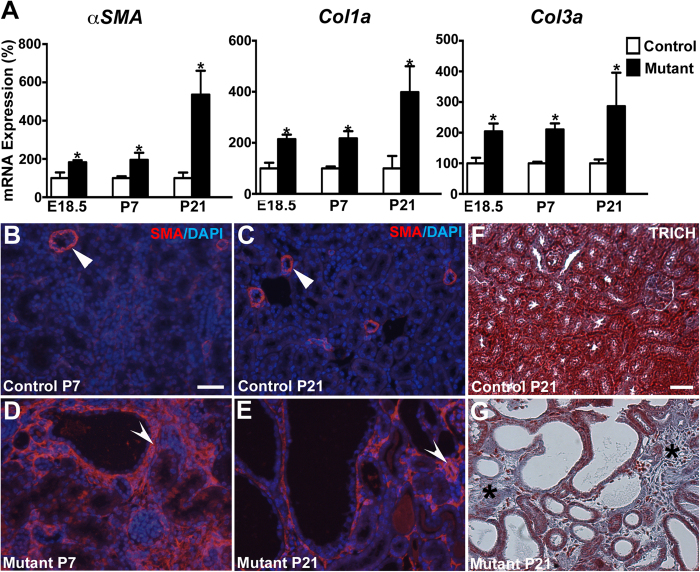

Increased and ectopic β-catenin expression in Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys

Aberrant increases in β-catenin signaling have been identified in many PKD models25,26,32,41. In our study, immunofluorescence showed that while β-catenin was only expressed in LTL-negative control tubules at P7 and P21, it was ectopically expressed in LTL-positive cysts in P7 and P21 Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys (Fig. 4A–F and not shown). Furthermore, while Western blots revealed equivalent β-catenin levels in E18.5 mutant and control kidneys, protein levels were marginally higher in P7 mutants and were clearly upregulated in P21 mutants versus controls (Fig. 4G). To determine whether the augmented β-catenin expression was likely driving canonical Wnt signaling, we performed qPCR for the canonical Wnt target genes Axin2 and Lef1 in P7 whole kidneys. Indeed, we observed increased Axin2 and a trend for increased Lef1 mRNA in mutant kidneys versus controls (Supplementary Fig. 4D). Quantitative PCR for Wnt ligands, Wnt4, Wnt7b and Wnt9b revealed correlative increases in mutant mRNA levels starting at E18.5 and continuing through P21 versus controls (Supplementary Fig. 4A). In situ hybridization revealed patches of ectopic Wnt4 expression in P21 mutant cortical tubules/cysts and interstitium versus controls (Supplementary Fig. 4B,C). Together, these data show Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys have aberrant upregulation of Wnt ligands and canonical β-catenin signaling.

Figure 4. Postnatal Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys have ectopic and increased β-catenin expression versus controls.

(A–C) Co-immunofluorescence for β-catenin (red) and LTL (green) in controls at P21 reveals β-catenin (A) expression in LTL-negative tubules (likely collecting ducts) (B) on merged images (C, arrowheads) (D–F). Immunofluorescence in mutants shows ectopic β-catenin expression (D) in LTL-positive cysts (E) on merged images (F, concave arrowheads). (G) Western blots reveal equivalent β-catenin protein levels in E18.5 mutants (M1–3) and controls (C1–3), but gradually increasing levels in P7 and P21 mutants versus controls (β-cat = β-catenin, GAP = GAPDH, actin = β-actin) (cropped blots are shown as indicated by the lines- these blots were run under the same experimental conditions). (A–F) scale bar = 25 μm.

Macrophage infiltration and inflammatory genes in Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys

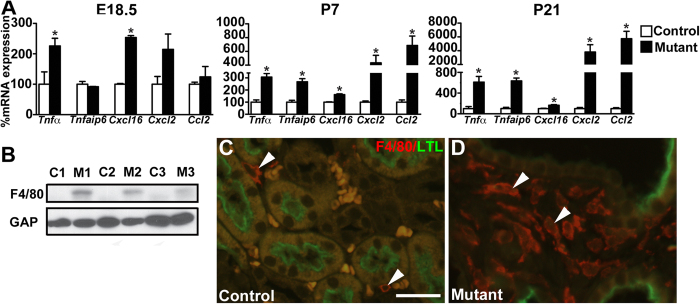

We next examined whether Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys had increased expression of inflammatory cytokines, particularly those that recruit monocytes/macrophages (e.g. Ccl2) or that are secreted by activated macrophages (e.g. Tnfα and Cxcl2), as in other PKD models28,29,30,33,40,42. From E18.5 to P21, we noted increasing mutant kidney Tnfα, Tnfaip6 (a Tnfα readout), Cxcl16, Cxcl2, and Ccl2 expression versus controls by qPCR (Fig. 5A). The most striking increases were in P21 mutant Cxcl2 and Ccl2 levels. We then examined Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys for macrophage infiltration, which is also seen in other PKD models29. We observed increased F4/80 protein expression in P21 mutant kidneys by Western blot (Fig. 5B) and many more F4/80-positive macrophages by immunofluorescence in P7 and P21 mutant interstitium (Fig. 5C,D and not shown) than controls.

Figure 5. Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys have increases in inflammatory cytokines and macrophage infiltration.

(A) Graphs of qPCR assays from whole kidneys shows up-regulation in mutant TNFα, Tnfaip6, Cxcl16, Cxcl2, and Ccl2 mRNA versus controls, that worsens with age (note Cxcl2 and Ccl2 relative expression levels at P21) (*p < 0.05). (B) Western blot reveals that P21 mutants (M1-3) have increased F4/80 protein expression than controls (C1-3) (cropped blots are shown as indicated by the lines- these blots were run under the same experimental conditions). (C,D) Co-immunofluorescence for F4/80 (red) and LTL (green) shows that while P21 controls have few red-staining macrophages in the interstitium (C, arrowheads), mutants have many macrophages in the interstitium (D, arrowheads); note that the orange-staining cells in the control image are red blood cells. (GAP = GAPDH). Scale bar = 25 μm.

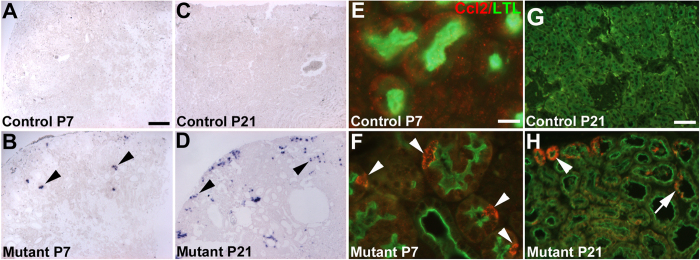

We then sought to determine the source of the increased mutant Ccl2 expression (that was likely driving macrophage infiltration). In controls, we detected no obvious Ccl2 expression by in situ hybridization; however, P7 mutants had punctate ectopic staining exclusively in non-dilated renal cortical epithelial cells. P21 mutants had more widespread Ccl2 expression, mostly in minimally dilated tubules, but occasionally in cyst lining cells (Fig. 6A–D). Dual-label immuno-fluorescence for Ccl2 and LTL revealed no Ccl2 protein expression in controls at any age or mutant kidneys at E18.5 (Fig. 6E,G, Supplementary Fig. 8E,F); however, at P7 individual Ccl2-positive cells were present within non-cystic LTL-positive mutant proximal tubules (Fig. 6F). At P21, Ccl2 protein was ectopically expressed most robustly in minimally-dilated mutant proximal tubules, and to a lesser degree in LTL-positive cyst-lining cells (Fig. 6H). Thus, the ectopic Ccl2 signal in Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys emanates from non-dilated proximal tubules at P7 and from both LTL-positive non-dilated and cyst lining cells later.

Figure 6. Ccl2 is ectopically expressed initially in non-dilated Six2creFrs2αKO proximal tubular cells.

(A,B) At P7, in situ hybridization reveals no apparent Ccl2 expression in controls (A), but diffuse punctate staining exclusively in non-dilated cortical tubular cells in mutants (B, arrowheads). (C,D) At P21, in situ hybridization again shows no Ccl2 staining in controls (C), but reveals a larger number of mostly non-dilated mutant cortical cells with ectopic expression of Ccl2 (D, arrowheads). (E,F) At P7, co-immunofluorescence for LTL (green) and Ccl2 (red) reveals no Ccl2 expression in controls (E), but ectopic Ccl2 expression in individual cells within non-dilated LTL-positive proximal tubules in mutants (F, arrowheads). (G,H) At P21, co-labeling immunofluorescence reveals no signal in controls (G), but strong labeling of minimally-dilated LTL-positive tubules in the outer cortex (arrowhead) and of individual cells within LTL-positive cyst lining cells (arrow). (A–D) scale bar = 100 μm; (E,F) scale bar = 12.5 μm; (G,H) scale bar = 25 μm.

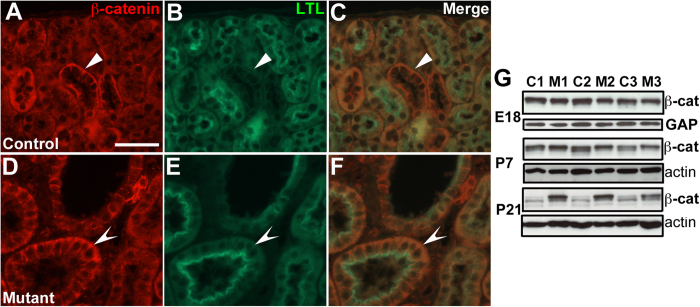

Cilia and Hedgehog signaling in Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys

We next determined whether cilia are present in Frs2α-deficient proximal tubular cells, given that disruption of cilia formation or function are often associated with PKD15,31,43. Co-staining of tubular epithelial cells isolated from P21 Six2creFRS2αKO and control kidneys with aquaporin-1 (proximal tubular marker) and acetylated α-tubulin (ciliary marker) revealed normal-appearing cilia in mutants versus controls (Supplementary Fig. 5A–D). Also, qPCR showed that P21 Six2creFRS2αKO and control kidneys have equivalent expression of several genes critical for cilia formation (Supplementary Fig. 5E).

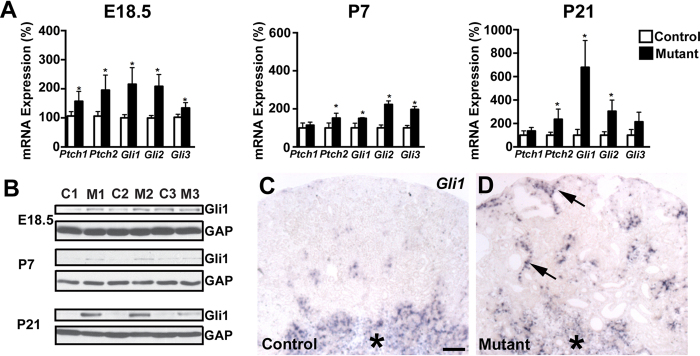

Normal appearing cilia can be dysfunctional and augmented hedgehog signaling has been thought to indicate ciliary dysfunction in cyst lining cells in PKD models12. Thus, we determined whether hedgehog signaling is mis-regulated in Six2creFRS2αKO cystic kidneys. Quantitative PCR revealed increases (or trends for increases) in mutants from E18.5 to P21 for multiple readouts of hedgehog activity, including Patched 1–2, Gli1–3, and Smoothened mRNA (Fig. 7A). Western blots confirmed increased Six2creFrs2αKO kidney Gli1 expression, a strong indicator of hedgehog signaling versus controls, increasing from E18.5 to P21 (Fig. 7B). To determine the target cells of the increased hedgehog activity in the mutant kidneys, we examined Gli1 expression by in situ hybridization. In P7 controls and mutants, we observed similar medullary Gli1 staining; however, mutants had ectopic Gli1 expression in the renal cortical interstitium, usually adjacent to cysts, but almost never in cyst lining cells (Fig. 7C,D). At P21 and P28, we again found that virtually all of the ectopic mutant Gli1 expression was in the expanded interstitium near cysts, and excluded from the cyst lining cells (Supplementary Fig. 6 and not shown). Thus, the primary target of the mutant ectopic hedgehog signaling appears to be interstitial cells and not cyst lining cells, suggesting that the augmented hedgehog activity is not likely a readout of cyst lining cell ciliary dysfunction.

Figure 7. Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys have evidence of augmented hedgehog signaling.

(A) Graphs of quantitative PCR analyses from control and mutant kidneys reveal relative age-dependent increases in mRNA of hedgehog signaling components, Ptch1, Ptch2, Gli1, Gli2, and Gli3. (B) Western blot analysis reveals increases in mutant (M1–3) kidney expression of Gli1 protein, a strong readout of hedgehog activity, starting at E18.5, but increasing at P7 and P21 versus controls (C1–3) (cropped blots are shown as indicated by the lines- these blots were run under the same experimental conditions). (C,D) in situ hybridization at P7 reveals similar medullary Gli1 expression in controls (C, asterisk) and mutants (D, asterisk), but ectopic expression in mutant cortical interstitium, often adjacent to cyst lining cells (D, arrowheads). (GAP = GAPDH). (C,D) scale bar = 100 μm.

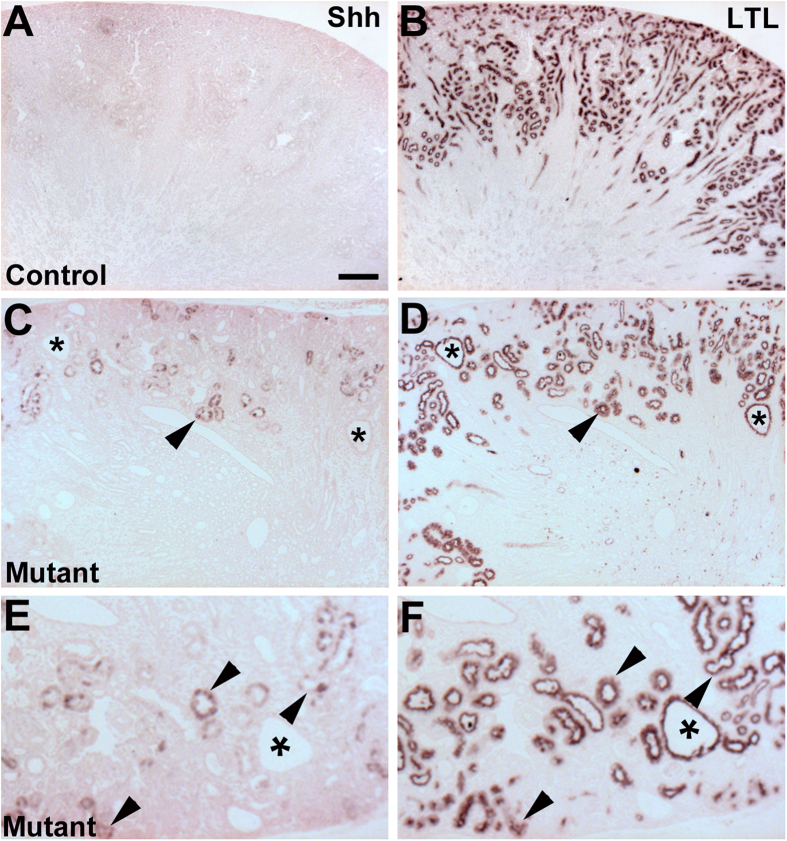

We then sought to determine the source driving the increased Six2creFrs2αKO kidney hedgehog signaling. Quantitative PCR analysis from mRNA isolated from P7 mutant and control kidneys showed a significant increase Sonic Hedgehog transcript levels in the mutant vs. control whereas, Indian and Desert Hedgehog mRNA levels were not significantly different (Supplementary Fig. 7A). Furthermore, immunostaining for Shh and LTL in adjacent sections at P7 revealed no Shh expression in control cortex (Fig. 8A), but many mutant cortical tubules with ectopic staining that were also all LTL-positive (Fig. 8C–F). Moreover, the ectopic staining was only noted in non-dilated proximal tubules and excluded from cyst lining cells. Notably, we could not detect any ectopic increase in Shh expression in E18.5 mutant kidneys by immunostaining, making this something that occurs in postnatal mature tubules (Supplementary Fig. 8A,B). At P21, we also did not observe any further ectopic Shh staining in Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys. Thus, it appears that ectopic mutant Shh protein in non-dilated proximal tubules in early postnatal kidneys likely triggers the ectopic Gli1 expression in the mutant interstitium (and that the cyst lining cells are not driving the augmented hedgehog response).

Figure 8. P7 Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys have ectopic Shh staining in non-dilated proximal tubules.

(A,B) Immunostaining for Shh and LTL in adjacent P7 control kidneys (A and B, respectively) reveals no obvious Shh expression (A). (C,D) Immunostaining in P7 mutant kidneys shows clusters of ectopic Shh staining in non-dilated tubules (C, arrowhead) that also express LTL in an adjacent section (D, arrowhead), but shows no Shh staining in LTL-positive cyst lining cells (asterisks). (E,F) Higher magnification from regions in panels (C,D) (respectively), confirm that non-dilated Shh-expressing mutant tubules are also LTL-positive (arrowheads), but that LTL-positive cysts do not express Shh (asterisks). (A–D) scale bar = 100 μm.

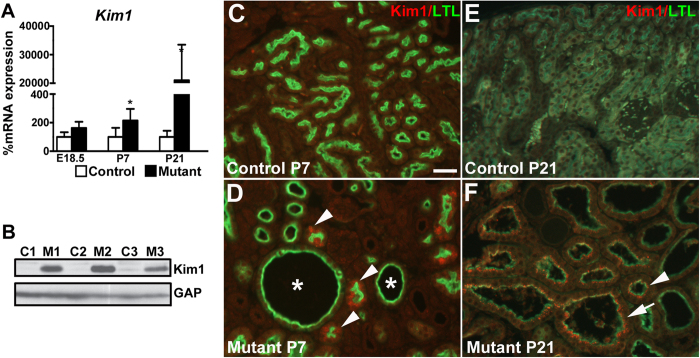

Six2creFrs2αKO proximal tubular-derived cells have upregulation of the acute kidney injury marker, Kim1

Given that ectopic proximal tubular Shh and Ccl2 expression has been observed in models of acute kidney injury44,45,46, we assessed whether Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys had ectopic expression of another bone fide marker of acute kidney injury, Kim147,48. Quantitative PCR from E18.5 to P21, revealed significantly elevated levels of mutant Havcr1 (the gene that encodes Kim1) versus controls by P7 and that were exaggerated by P21 (Fig. 9A). Western blot confirmed marked increases in P21 mutant kidney Kim1 levels versus controls. Although Kim1 expression was undetectable in control and mutant kidneys at E18.5 (Supplementary Fig. 8C,D), co-immunofluorescence in P7 mutants revealed patches of non-dilated LTL-positive/Kim1-positive cells, often near cysts, but excluded from the cyst lining cells, versus no staining in controls (Fig. 9C,D). By P21, we detected ectopic Kim1 staining in many LTL-positive mutant cells, including those present in minimally dilated tubules and in overt cysts (Fig. 9E,F). Together, it appears that many of the “normal” appearing non-dilated Six2creFrs2αKO proximal tubules at P7 have ectopic expression of acute kidney injury markers, some of which persist in the LTL-positive cyst lining cells at P21.

Figure 9. Kim1 is ectopically expressed initially in Six2creFrs2αKO non-dilated proximal tubular cells.

(A) Quantitative PCR analysis reveals increases in mutant kidney Kim1 mRNA expression versus controls starting at P7 and worsening at P21. (B) Western blot analysis at P21 confirms a significant increase in Kim1 protein in mutant kidneys (M1-3) versus controls (C1–3) (cropped blots are shown as indicated by the lines- these blots were run under the same experimental conditions). (C,D) Co-immunofluorescence for Kim1 (red) and LTL (green) at P7 reveals that while controls display no Kim1 expression (C), subsets of mutant non-dilated LTL-positive proximal cells ectopically express Kim1 (D, arrowheads), whereas mutant LTL-positive cysts (D, asterisks) do not. (E,F) Co-immunofluorescence for Kim1 (red) and LTL (green) at P21 again shows no obvious Kim1 expression in control kidneys (E), whereas many minimally-dilated and overtly cystic LTL-positive mutant cells ectopically express Kim1 (F, arrowhead and arrow, respectively). (A,B) scale bar = (C–F) scale bar = 25 μm.

Discussion

We found that kidneys lacking Frs2α in nephron progenitors develop rapid cyst growth after birth. The mutant kidneys show increased proliferation of proximal tubular cells, progressive interstitial fibrosis, and macrophage infiltration, consistent with other PKD models. While Six2creFrs2αKO kidney weight/body weight ratios were not increased versus controls (as happens with other PKD models), we suspect that this is due the fact that the mutants have perinatal renal hypoplasia due to the previously reported E14.5 loss of nephron progenitors10 (and thus make fewer nephrons that even when becoming cystic do not result in massively enlarged kidneys). There are no reports of nephron progenitor depletion in other PKD models, which makes this finding unique to this model. While there appears to also be an increase in apoptosis in postnatal mutant proximal tubular cells, the overall rates in both mutants and controls appear low, making excess apoptosis only a minor contributor to the mutants not having significantly enlarged kidneys. Older Six2creFrs2αKO mice do have signs of advanced kidney failure with the elevated BUN levels versus littermate controls, consistent with what happens at advance stages of PKD. At the molecular level, Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys show aberrant upregulation of many signaling components, including β-catenin, inflammatory chemokines (e.g. Tnfα, Ccl2), and hedgehog, all of which are observed in other PKD models15,28,32,33,42. A novel finding in our model is that at early stages, we observe increases in tubular acute kidney injury markers (Shh, Ccl2, and Kim1), which likely has a significant role in driving disease pathogenesis.

Dysregulated β-catenin signaling, excessive chemokine production and macrophage infiltration are often seen in PKD models25,26,31,32,41. Excessive β-catenin accumulation has been observed in cystic models, including Pkd1 and Kif3α mutants, and appears to drive cystogenesis25,26,27,31,32,41. Thus, is it likely that ectopic β-catenin expression in Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys, which appears to be stimulated by increased Wnt ligand expression and appears to be a readout of canonical Wnt signaling, contributes to cyst growth. Excessive production of inflammatory chemokines that recruit macrophages (e.g. Ccl2) and that are secreted by activated macrophages (e.g. Tnfα) have been identified in and appear to have a causative role in many PKD models28,33,42. As in these models, Six2creFrs2αKO mice have excessive chemokine production and macrophage infiltration, which likely also drive cystogenesis. Thus, Six2creFrs2αKO mice share many features seen in other bone fide PKD models, and offer a novel model to interrogate mechanisms driving cystogenesis.

Another molecular pathway perturbed in Six2creFrs2αKO mice and in other PKD models is hedgehog. The qPCR profile in Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys revealed increases in hedgehog readouts (Fig. 7A) and has a marked resemblance to the profile in conditional knockouts of Pkd1 and Thm1 (a ciliary associated gene), established PKD models15. Furthermore, Thm1 mutants with concomitant deletion of Gli2 have diminished cystogenesis, indicating that increased hedgehog signaling contributes towards cyst progression in that model15. How aberrant hedgehog signaling contributes to cystogenesis in PKD remains to be defined.

Alterations in hedgehog signaling in PKD models are often thought to reflect ciliary dysfunction12. In Six2creFrs2αKO mice, however, ciliary structure in affected proximal tubular epithelial cells appeared normal, based on histology and in the qPCR profile for genes critical for ciliary formation12,15. While normal ciliary structure does not mean normal function, the ectopic Gli1 expression in Six2creFrs2αKO was most notable in the expanding interstitium and was rarely observed in cyst lining cells. This makes it unlikely that aberrant hedgehog signaling is a readout of ciliary dysfunction in our model (and perhaps in other PKD models).

Another question not often addressed in most PKD models is what drives the ectopic Gli1 expression. Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys have what appears to be ectopic Shh protein in subsets of non-dilated proximal tubular cells at P7 (and again, not in cystic epithelium). The protein expression most likely reflects Shh as opposed to Ihh or Dhh, given that qPCR only shows increases in mutant Shh transcripts (and not the others) versus controls at P7. The proximity of the ectopic Shh expression to the ectopic Gli1 in the interstitium makes it likely that the former drives the latter. Moreover, many data show that enhanced renal interstitial Gli1 activity leads to fibrosis44,49,50, making it likely that the ectopic hedgehog in Six2creFrs2αKO kidneys contributes to interstitial fibrosis. Perhaps ectopic Shh expression in non-dilated tubules has not been appreciated in other models (e.g. homozygous Pkd1 or Pkd2 mutants) due to early and rapid cyst progression making it difficult to assess non-dilated tubules.

Given that ectopic tubular Shh and Ccl2 expression has been noted after acute kidney injury44,45,46, we interrogated Kim1, a bone fide marker of AKI47,48, and noted ectopic expression early in subsets of Six2creFrs2αKO proximal tubules. While ectopic Kim1 production has been noted in other PKD models, its expression in non-cystic renal epithelium has not to our knowledge been documented48. Moreover, Kim1 can drive Ccl2 expression and thus may play an active role in driving pathogenesis in our and other PKD models51. Perhaps Six2creFrs2αKO tubules (and tubules in other PKD models) are “sensitized” to otherwise non-injurious stimuli, leading to the ectopic production of the aforementioned proteins. Moreover, the potential for overt AKI having a deleterious role in driving PKD pathogenesis is supported by studies showing that ischemic AKI superimposed on postnatal mice with induced Itf88 or Kif3α homozygous deletion (leading to deciliation) or with a one-allele loss of Pkd1 accelerates cyst progression compared to non-ischemic mice36,52,53. In mouse models and in human forms of dominant PKD, there has long been an assertion that a “second hit” is required for cyst growth that often starts later in life54. Perhaps subclinical injuries in sensitized tubules and/or overt AKI may often be that second hit.

Methods

Mice

Frs2αfl/fl and transgenic Six2creEGFP mice55,56, were bred to generate Six2creEGFP;Frs2αfl/fl mice (Six2creFrs2αKO) mice as described10. Cre negative littermates were used as controls. All experiments were carried out with the approval of the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the guidelines of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Whole mouse, kidney and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) measurements

P29 Six2creFrs2αKO and control mice (n = 4) were subjected to general anesthesia and blood removed by ventricular puncture leading to euthanasia. The mice were weighed after which kidneys were dissected and weighed. Blood was placed in heparinized tubes and plasma was obtained after centrifugation at 2000 rcf for 15 min. Plasma was sent to the Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, which performed BUN levels.

Western blot

Briefly, as described57,58,59, whole cell lysates were prepared from kidneys isolated from E18.5, P7 and P21 control and mutant mice and homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) with a protease inhibitor cocktail, sonicated for 10s and rocked for 15 min at 4 °C and then pelleted at 12,000 × g for 15 min. Supernatant was mixed in 2X Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad #161–0737). Whole-cell extracts were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and resolved proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which were then washed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Membranes were blocked and probed with primary antibodies (at dilutions listed in Supplementary Table 1) followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit or mouse second antibodies. The antigen-antibody complex was visualized with AmershamTM ECLTM prime Western blotting detection reagent. (GE Healthcare UK Limited Buckinghamshire UK, # RPN2232).

Immunofluorescence

Briefly, as described2,57, 4 μm paraformaldehyde (PFA)-fixed paraffin embedded kidney sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and subjected to antigen retrieval in citrate buffer (10 mm citrate, 0.1% Tween-20, pH 6.0) at 95 °C for 30 min and then kept at room temperature for 30 min. The sections were blocked for 1 h in donkey serum at room temperature and incubated for 12–24 h with primary antisera (see Supplemental Table 1). Alexa Fluor 594 and Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibodies were used and nuclei were stained with 4′6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Staining was detected using a Leica DM 2500 fluorescence microscope.

Cell proliferation and apoptosis

To determine proliferation rates of LTL positive cells, cross sections through the midpoint of mutant and control kidneys (n = 3 per genotype) were co-stained with the proliferation marker Ki67 and LTL. Ki67/LTL double positive cells and DAPI/LTL double positive cells were counted and proliferation rates were determined by dividing the former by the latter. To assay for apoptosis, Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated UTP end labeling (TUNEL) was performed with ApopTag Plus In Situ Apoptosis Fluorescein Detection kit (EMD Millipore S7111-Kit) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. To identify LTL-positive cells, the sections were incubated with biotinylated LTL followed by staining with Alexa Flour 594 streptavidin.

Proximal tubule-enriched primary cells

Briefly, as described60, P21 kidney cortices were digested with collagenase for 20 min at 37 °C and passed sequentially through 180 μm, 90 μm and 40 μm diameter sieves. Tubules between 40 and 90 μm were plated on fibronectin coated coverslips in DMEM/F12 medium with insulin, transferrin, selenite, hydrocortisone, Egf, triiodothyronine and penicillin-streptomycin for 7 days. Cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized, and immunostained as above (see Supplemental Table 1 for primary antibodies).

In situ hybridization

Briefly, as described6,10,58, 7 μm PFA-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and treated with proteinase K (10 μg/ml) for 30 minutes, re-fixed in PFA, incubated in 0.1% HCl for 10 min followed by rocking in 0.14 M triethanolamine and 0.25% acetic anhydride for 10 min. Slides were washed and blocked with hybridization buffer and incubated with digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled riboprobe for 12–15 h at 68 °C. Slides were washed, treated with RNase, blocked, and incubated with anti–DIG-AP antibody (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) overnight. Slides were then washed and developed with chromogenic substrate (BM Purple; Roche) for a maximum of 3 days, fixed and mounted with Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech, Birmingham. Al). Probe templates were generated by in vitro transcription from plasmids containing bases 34–587 of Wnt4 (NM009523.2) and 48–556 of Ccl2 (NM011333) coding regions, respectively. The Gli1 template was gifted by Dr. Alexandra Joyner61. Digoxigenin labeled antisense probes were generated with DIG labeling kits (Roche).

Quantitative real time PCR

RNA was extracted from snap frozen kidneys (n = 3 for E18.5 and P21; n = 4 for P7 samples) using the RNAeasy Plus MicroKit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 2. The Superscript First Strand cDNA kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) and a C1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were used to perform the qPCR assays. Reactions were conducted in a total volume of 12.5 μL containing 2.5 μL of cDNA, 6.25 μL of 2X Sso advanced SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, #1725261), and each primer at a concentration of 0.1 μM. Primer pairs were independently validated for use by melt curve analysis and gel electrophoresis to confirm the amplification of a single PCR product of expected size. For negative controls, a qPCR reaction was performed using cDNA obtained from reverse transcription reactions lacking reverse transcriptase. The qPCR analysis was initiated by melting of cDNA at 95 °C for 3 min and followed by 40 amplification cycles of 30 sec at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C. Dissociation-curve analysis was performed and Ct values were recorded and analyzed via the ΔΔCt method to characterize relative fold-changes in mRNA expression between treatment groups. Gapdh was used for normalization.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses of qPCR experiments were performed on biological replicates using a Student’s t-test. Values are represented as means ± standard error with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Puri, P. et al. Six2creFrs2α knockout mice are a novel model of renal cystogenesis. Sci. Rep. 6, 36736; doi: 10.1038/srep36736 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Sunder Sims-Lucas and Dr. Jacqueline Ho for their helpful suggestions with this study. This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants R01 DK095748 (C.M.B.), P01 DK093424 (A.K), and the Pittsburgh Center for Kidney Research, P30

Footnotes

Author Contributions C.M.B. and P.P. designed and supervised the project. P.P., D.B. and C.M.S. conducted and analyzed the experiments. C.M.B. and P.P. contributed to writing and editing of the manuscript.

References

- Hadari Y. R., Gotoh N., Kouhara H., Lax I. & Schlessinger J. Critical role for the docking-protein FRS2 alpha in FGF receptor-mediated signal transduction pathways. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98, 8578–8583 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poladia D. P. et al. Role of fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 and 2 in the metanephric mesenchyme. Developmental biology 291, 325–339 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims-Lucas S. et al. Three-dimensional imaging reveals ureteric and mesenchymal defects in Fgfr2-mutant kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol 20, 2525–2533, doi: ASN.2009050532 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims-Lucas S. et al. Fgfr1 and the IIIc isoform of Fgfr2 play critical roles in the metanephric mesenchyme mediating early inductive events in kidney development. Dev Dyn 240, 240–249, doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22501 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims-Lucas S. et al. Independent roles of Fgfr2 and Frs2alpha in ureteric epithelium. Development 138, 1275–1280, doi: 10.1242/dev.062158 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims-Lucas S. et al. Ureteric morphogenesis requires Fgfr1 and Fgfr2/Frs2alpha signaling in the metanephric mesenchyme. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 23, 607–617, doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011020165 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barasch J. et al. Ureteric bud cells secrete multiple factors, including bFGF, which rescue renal progenitors from apoptosis. Am J Physiol 273, F757–F767 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieshammer U. et al. FGF8 is required for cell survival at distinct stages of nephrogenesis and for regulation of gene expression in nascent nephrons. Development (Cambridge, England) 132, 3847–3857 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng C. X. et al. Murine FGFR-1 is required for early postimplantation growth and axial organization. Genes & development 8, 3045–3057 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovanni V. et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor-Frs2alpha signaling is critical for nephron progenitors. Dev Biol 400, 82–93, doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.01.018 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V., Chowdhury R. & Igarashi P. Advances in the pathogenesis and treatment of polycystic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18, 99–106, doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283262ab0 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winyard P. & Jenkins D. Putative roles of cilia in polycystic kidney disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812, 1256–1262, doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.04.012 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder B. K. Role of primary cilia in the pathogenesis of polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 18, 1381–1388, doi: ASN.2006111215 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt F. & Otto E. Cilia and centrosomes: a unifying pathogenic concept for cystic kidney disease? Nat Rev Genet 6, 928–940, doi: 10.1038/nrg1727 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran P. V. et al. Downregulating hedgehog signaling reduces renal cystogenic potential of mouse models. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 25, 2201–2212, doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013070735 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauli S. M. et al. Loss of polycystin-1 in human cyst-lining epithelia leads to ciliary dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol 17, 1015–1025, doi: 17/4/1015 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonassen J. A., San Agustin J., Follit J. A. & Pazour G. J. Deletion of IFT20 in the mouse kidney causes misorientation of the mitotic spindle and cystic kidney disease. The Journal of cell biology 183, 377–384, doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808137 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonassen J. A., SanAgustin J., Baker S. P. & Pazour G. J. Disruption of IFT complex A causes cystic kidneys without mitotic spindle misorientation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 23, 641–651, doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011080829 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazour G. J. et al. Chlamydomonas IFT88 and its mouse homologue, polycystic kidney disease gene tg737, are required for assembly of cilia and flagella. The Journal of cell biology 151, 709–718 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condac E. et al. Polycystic disease caused by deficiency in xylosyltransferase 2, an initiating enzyme of glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 9416–9421, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700908104 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciano D. K. et al. p120 catenin is required for normal renal tubulogenesis and glomerulogenesis. Development (Cambridge, England) 138, 2099–2109, doi: 138/10/2099 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veis D. J., Sorenson C. M., Shutter J. R. & Korsmeyer S. J. Bcl-2-deficient mice demonstrate fulminant lymphoid apoptosis, polycystic kidneys, and hypopigmented hair. Cell 75, 229–240 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karner C. M. et al. Wnt9b signaling regulates planar cell polarity and kidney tubule morphogenesis. Nature genetics 41, 793–799, doi: ng.400 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdeguer F. et al. A mitotic transcriptional switch in polycystic kidney disease. Nat Med 16, 106–110, doi: 10.1038/nm.2068 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal M. et al. Polycystin-1 C-terminal tail associates with beta-catenin and inhibits canonical Wnt signaling. Human molecular genetics 17, 3105–3117, doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn208 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster M. A. et al. Impaired Wnt-beta-catenin signaling disrupts adult renal homeostasis and leads to cystic kidney ciliopathy. Nature medicine 15, 1046–1054, doi: nm.2010 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadi-Kheddouci S. et al. Early development of polycystic kidney disease in transgenic mice expressing an activated mutant of the beta-catenin gene. Oncogene 20, 5972–5981 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley B. D. Jr., Ricardo S. D., Nagao S. & Diamond J. R. Increased renal expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and osteopontin in ADPKD in rats. Kidney international 60, 2087–2096, doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00065.x (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karihaloo A. et al. Macrophages promote cyst growth in polycystic kidney disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 22, 1809–1814, doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011010084 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson-Fields K. I. et al. Macrophages promote polycystic kidney disease progression. Kidney international 83, 855–864, doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.446 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin F. et al. Kidney-specific inactivation of the KIF3A subunit of kinesin-II inhibits renal ciliogenesis and produces polycystic kidney disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100, 5286–5291, doi: 10.1073/pnas (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I. et al. Conditional mutation of Pkd2 causes cystogenesis and upregulates beta-catenin. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 20, 2556–2569, doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009030271 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. et al. A tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated pathway promoting autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Med 14, 863–868, doi: 10.1038/nm1783 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoja C. et al. Effects of MCP-1 inhibition by bindarit therapy in a rat model of polycystic kidney disease. Nephron 129, 52–61, doi: 10.1159/000369149 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer J. M., Amack J. D., Peterson A. G., Bisgrove B. W. & Yost H. J. FGF signalling during embryo development regulates cilia length in diverse epithelia. Nature 458, 651–654, doi: nature07753 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V. et al. Acute kidney injury and aberrant planar cell polarity induce cyst formation in mice lacking renal cilia. Human molecular genetics 17, 1578–1590, doi: ddn045 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassane S. et al. Elevated TGFbeta-Smad signalling in experimental Pkd1 models and human patients with polycystic kidney disease. J Pathol 222, 21–31, doi: 10.1002/path.2734 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman J. Fibrosis and progression of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). Biochim Biophys Acta 1812, 1327–1336, doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.06.012 ( 2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. J. et al. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products inhibits disease progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease by down-regulating cell proliferation. FASEB J 29, 3506–3514, doi: 10.1096/fj.15-272302 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. C. & Torres V. E. Genetic mechanisms and signaling pathways in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. The Journal of clinical investigation 124, 2315–2324, doi: 10.1172/JCI72272 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster M. A. & Gleeson J. G. Cystic kidney disease: the role of Wnt signaling. Trends Mol Med 16, 349–360, doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.05.004 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor promotes cyst growth in polycystic kidney disease. The Journal of clinical investigation 125, 2399–2412, doi: 10.1172/JCI80467 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauli S. M. et al. Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nature genetics 33, 129–137 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H. et al. Sonic hedgehog signaling mediates epithelial-mesenchymal communication and promotes renal fibrosis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 23, 801–813, doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011060614 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishihara K. et al. Urinary chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1) as a tubular injury marker for early detection of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Biochemical pharmacology 85, 570–582, doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.12.019 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munshi R. et al. MCP-1 gene activation marks acute kidney injury. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 22, 165–175, doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010060641 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W. K., Bailly V., Abichandani R., Thadhani R. & Bonventre J. V. Kidney Injury Molecule-1 (KIM-1): a novel biomarker for human renal proximal tubule injury. Kidney international 62, 237–244, doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00433.x (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn E. W., Park K. M., Somlo S. & Bonventre J. V. Kidney injury molecule-1 expression in murine polycystic kidney disease. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology 283, F1326–F1336, doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00166.2002 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian S. L. et al. Hedgehog-Gli pathway activation during kidney fibrosis. The American journal of pathology 180, 1441–1453, doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.12.039 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D. et al. Sonic hedgehog is a novel tubule-derived growth factor for interstitial fibroblasts after kidney injury. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 25, 2187–2200, doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080893 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys B. D. et al. Chronic epithelial kidney injury molecule-1 expression causes murine kidney fibrosis. The Journal of clinical investigation 123, 4023–4035, doi: 10.1172/JCI45361 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N. et al. Proximal tubule proliferation is insufficient to induce rapid cyst formation after cilia disruption. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 24, 456–464, doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012020154 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos A. P. et al. Pkd1 haploinsufficiency increases renal damage and induces microcyst formation following ischemia/reperfusion. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 20, 2389–2402, doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008040435 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. C. What is the role of somatic mutation in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease? Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN 21, 1073–1076, doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010030328 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y., Zhang J., Zhang Y. & Wang F. Generation of an Frs2alpha conditional null allele. Genesis 45, 554–559 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A. et al. Six2 defines and regulates a multipotent self-renewing nephron progenitor population throughout mammalian kidney development. Cell Stem Cell 3, 169–181, doi: S1934-5909(08)00347-0 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri P. & Walker W. H. The tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 regulates Sertoli cell junction complexes. Biol Reprod 88, 59, doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.104414 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates C. M., Merenmies J. M., Kelly-Spratt K. S. & Parada L. F. Insulin receptor-related receptor expression in non-A intercalated cells in the kidney. Kidney international 52, 674–681 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phua Y. L. & Ho J. MicroRNAs in the pathogenesis of cystic kidney disease. Current opinion in pediatrics 27, 219–226, doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000168 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattila P. E., Raghavan V., Rbaibi Y., Baty C. J. & Weisz O. A. Rab11a-positive compartments in proximal tubule cells sort fluid-phase and membrane cargo. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology 306, C441–C449, doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00236.2013 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt K. A., Michaud J. & Joyner A. L. Expression of the mouse Gli and Ptc genes is adjacent to embryonic sources of hedgehog signals suggesting a conservation of pathways between flies and mice. Mechanisms of development 62, 121–135 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.