Abstract

Study Design.

A 14-week, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled study of Japanese patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP) who were randomized to either duloxetine 60 mg once daily or placebo.

Objective.

This study aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of duloxetine monotherapy in Japanese patients with CLBP.

Summary of Background Data.

In Japan, duloxetine is approved for the treatment of depression, diabetic neuropathic pain, and pain associated with fibromyalgia; however, no clinical study of duloxetine has been conducted for CLBP.

Methods.

The primary efficacy measure was the change in the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) average pain score from baseline to Week 14. Secondary efficacy measures included BPI pain (worst pain, least pain, pain right now), Patient's Global Impression of Improvement, Clinical Global Impressions of Severity, and Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, among other measures, and safety and tolerability.

Results.

In total, 458 patients were randomized to receive either duloxetine (n = 232) or placebo (n = 226). The BPI average pain score improved significantly in the duloxetine group compared with that in the placebo group at Week 14 [−2.43 ± 0.11 vs. −1.96 ± 0.11, respectively; between-group difference (95% confidence interval), − 0.46 [−0.77 to−0.16]; P = 0.0026]. The duloxetine group showed significant improvement in many secondary measures compared with the placebo group, including BPI pain (least pain, pain right now) (between-group difference: −1.69 ± 0.10, P = 0.0009; −2.42 ± 0.12, P P = 0.0230, respectively), Patient's Global Impression of Improvement (2.46 ± 0.07, P = 0.0026), Clinical Global Impressions of Severity (−1.46 ± 0.06, P = 0.0019), and Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (−3.86 ± 0.22, P = 0.0439). Adverse events occurring at a significantly higher incidence in the duloxetine group were somnolence, constipation, nausea, dizziness, and dry mouth, most of which were mild or moderate in severity and were resolved or improved.

Conclusion.

Duloxetine 60 mg was effective and well tolerated in Japanese CLBP patients.

Level of Evidence: 2

Keywords: Brief Pain Inventory, chronic low back pain, duloxetine, efficacy, Japan, placebo, randomized clinical trial, safety, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

Low back pain (LBP) has an estimated lifetime prevalence of 83%, and approximately 25% to 35% of Japanese patients complain of LBP.1,2 Chronic LBP (CLBP) is usually defined as pain persisting for at least 3 months. Patients with acute LBP show rapid improvement within 1 month after onset, followed by gradual improvement until 3 months after onset; however, a high incidence of protracted treatment has been reported along with low patient satisfaction with treatment.3,4

Treatment strategies for LBP include drug therapy, physical and orthotic therapy, exercise, nerve block injection, and surgery. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, anxiolytics, muscle relaxants, antidepressants, and opioids are recommended by international5,6 and Japanese LBP treatment guidelines.7 In Japan, NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and some opioids have been approved for the treatment of LBP. First-line treatment with NSAIDs has been demonstrated to be effective for acute LBP, but its efficacy for CLBP has not been confirmed,8 and possible gastrointestinal, cardiac, and renal9 adverse drug reactions (ADRs) should be considered with long-term use. The evidence of the effectiveness of other drugs is insufficient, and concerns about ADRs remain.

Duloxetine, a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), inhibits the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, which are neurotransmitters of the descending pain inhibitory pathways. Although the exact mechanisms of central pain inhibition by duloxetine in humans are unknown, it is believed that duloxetine increases synaptic cleft levels of these neurotransmitters in the spinal and supraspinal pathways, activating the descending pain inhibitory systems and producing an analgesic effect.10 Three clinical studies in patients with CLBP have been conducted overseas.11–13 Two of these provided clinical evidence that duloxetine significantly reduces pain compared with placebo and is well-tolerated. Based on these results and those of clinical studies of osteoarthritis patients, duloxetine has been approved for “chronic musculoskeletal pain” or “chronic low back pain and chronic pain associated with osteoarthritis” in the United States and 28 other countries. Furthermore, in the field of pain management, it has been approved for diabetic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia.

In Japan, duloxetine is approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder, diabetic neuropathic pain, and pain associated with fibromyalgia;14–16 however, no clinical study of duloxetine has been conducted in Japanese patients with CLBP. Therefore, the current study aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of duloxetine monotherapy in Japanese patients with CLBP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Treatment

This randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase III study was conducted in 58 medical institutions in Japan from May 2013 to July 2014. This study consisted of four study periods: a 1-week to 2-week pretreatment period, 14-week treatment period, 1-week taper period, and 1-week follow-up period. In the pretreatment period, patients were withdrawn from analgesics (including NSAIDs) and other therapeutic drugs (including muscle relaxants, antidepressants, sedatives, and benzodiazepines) for CLBP, and concomitant use of these drugs was prohibited during the study. Additional details of allowed or prohibited treatments are provided (see text, Supplemental Digital Content 1).

Patients who met the inclusion criteria were randomized to treatment with duloxetine 60 mg once daily or placebo, orally, after completion of the pretreatment period, using a stochastic minimization procedure. The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) average pain score at baseline (<6, ≥6) was used as the allocation factor. Patients and investigators were blinded to the treatment; the appearance and labeling of the doses were indistinguishable between placebo and the study drug. The investigator in charge of allocation randomly assigned patients to treatment or placebo based on an assignment table developed using the SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) PLAN procedure. After allocation, the assignment table was sealed by the investigator in charge of allocation, and remained inaccessible by all involved parties until after finalization of the clinical report. After randomization, patients received treatment after breakfast under double-blind conditions.

In the treatment period, the duloxetine group received duloxetine at 20 mg/day for 1 week and then at 40 mg/day for 1 week, followed by 60 mg/day for 12 weeks. The placebo group received placebo during the 14-week treatment period. Patients underwent tapering after completion of the treatment period or after discontinuation after 2 weeks of treatment.

Informed consent was obtained from all patients before the study start. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each medical institution. This study was conducted in compliance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines and was registered in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01855919).

Patients

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) male and female outpatients of age 20 to <80 years who had LBP persisting for at least 6 months; (ii) had used NSAIDs for at least 14 days per month for an average of 3 months before the start of the study and for at least 14 days during the 1-month period before the start of the study, regardless of dose of NSAIDs and route of administration; (iii) did not have radiculopathy symptoms or other specific low back diseases; and (iv) had a BPI pain (average pain)17 of ≥4 at Visit 1 (Week −1 to −2) and Visit 2 (Week 0).

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) patients with a history of low back surgery; (ii) those receiving invasive treatment for the relief of LBP within 1 month before Visit 1; (iii) those requiring crutches or a walker; and (iv) those diagnosed as having major depressive disorders according to the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview18 or suicidal tendencies according to the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).19

Efficacy

The primary efficacy measure was the BPI average pain score, which measures average pain during the past 24 hours on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (pain as bad as you can imagine).17 The secondary efficacy measures were (i) the worst, least, and pain right now item scores of BPI and pain interference with seven daily activities (general activity, mood, walking ability, normal work, relations with other people, sleep, and enjoyment of life); (ii) the 24-hour average pain and 24-hour worst pain score (weekly mean); (iii) Patient's Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I)20 and Clinical Global Impressions of Severity (CGI-S) scores; (iv) LBP-specific quality of life (QOL) using the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ-24)21–23; (v) the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36; Japanese version 2) score24,25; (vi) the European QOL Questionnaire-5 Dimension (EQ-5D) score26; and (vii) the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Instrument (WPAI) score.27 Additional details on the assessment of the secondary efficacy measures are provided (see text, Supplemental Digital Content 2).

Safety

For safety, the incidences of adverse events (AEs), serious adverse events (SAEs), discontinuation because of AEs, and ADRs during the study period were calculated. AEs and SAEs were monitored from the beginning of administration till the end of the follow-up period. In addition, laboratory tests (hematology, clinical chemistry, and urinalysis), electrocardiogram, and measurements of body weight, blood pressure, and pulse were performed. The occurrence of falls was investigated, and the presence of suicidal tendencies was assessed using the C-SSRS.

Statistical Analyses

The between-group difference in the change in BPI average pain at 14 weeks was estimated to be −0.60 with a standard deviation (SD) of 1.94, in reference to the study by Skljarevski et al,11 in which the conditions of use for NSAIDs during the study period were similar to those of the current study. Under this assumption, 450 patients (225 per group) would provide at least 90% power at a two-sided significance level of 0.05.

All efficacy and safety analyses were performed on the full analysis set (FAS) and safety analysis set, respectively. Unless otherwise noted, the treatment effects were tested with a two-sided significance level of 0.05.

A mixed-effects model repeated measures approach (MMRM analysis) was used to compare the change in BPI average pain score from baseline to Week 14 between duloxetine and placebo groups. The model included the fixed effects of treatment, time point, and treatment-by-time point interaction as well as a covariate of baseline BPI average pain. The unstructured covariance was applied in this primary analysis.

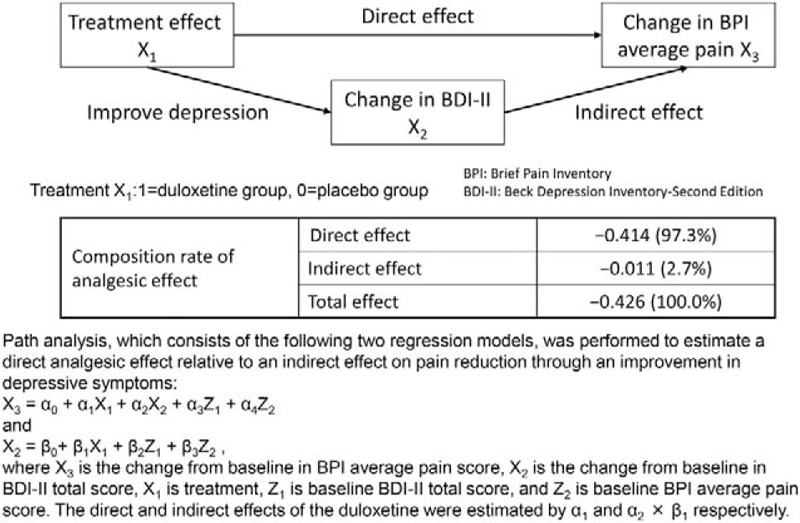

The response rate was examined as another analysis of the primary efficacy measure. In the responder analysis, the number of responders and the response rate were calculated in each group in terms of 30% pain reduction, 50% pain reduction, and sustained pain reduction, which was defined as BPI average pain reduction of at least 30% from baseline at any point before the last visit, and remaining at least >20% below baseline for the remainder of the study period. These response rates were compared between the groups using a Mantel-Haenszel test with baseline BPI average pain score as the stratification factor. The categorical distribution of the PGI-I results at the final evaluation were also investigated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Path analysis was performed to estimate the ratio between the direct analgesic effect of duloxetine and its indirect analgesic effect through antidepressant action.

In the analyses of the change in secondary efficacy measures, MMRM analysis was performed using longitudinal data on BPI pain (worst pain, least pain, pain right now), BPI interference, 24-hour average and worst pain score (weekly mean), and CGI-S to compare the change at Week 14 between the two treatment groups. The PGI-I was analyzed using an MMRM model as a covariate of baseline PGI-S score. For the RDQ-24, SF-36, EQ-5D, and WPAI, ANCOVA was performed to compare the change from baseline to Week 14 between both treatment groups. In the safety analysis set, the incidence of AEs and ADRs was compared between the groups using Fisher's exact test. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.2. Additional details of the statistical analysis are provided (see text, Supplemental Digital Content 3).

RESULTS

Patient Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

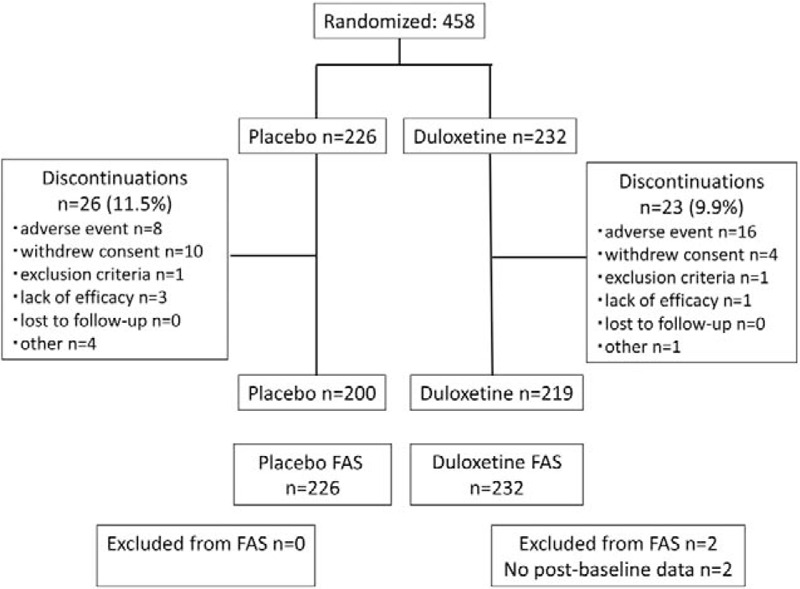

A total of 458 patients were enrolled in the study and randomized to the duloxetine (n = 232) and placebo groups (n = 226) (Figure 1). Discontinuation during the treatment period occurred in 23 (9.9%) and 26 (11.5%) patients in the duloxetine and placebo groups, respectively. The most common reason for discontinuation during the treatment period was the development of AEs in the duloxetine group (16 patients: 6.9%) and consent withdrawal in the placebo group (10 patients: 4.4%). In total, 428 patients entered the taper period. Only one patient in the duloxetine group requested discontinuation of treatment and was withdrawn from the study during the taper period.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition.

The baseline characteristics of the 456 patients included in the FAS are shown in Table 1. The distribution of patient baseline characteristics showed no imbalance (significance level: 0.15) between the duloxetine and placebo groups, except for age. However, this difference was not considered to have affected the study results.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics (Full Analysis Set)

| Placebo (n = 226) | Duloxetine (n = 230) | P* | |

| Age, years | 57.8 ± 13.7 | 60.0 ± 13.2 | 0.0745 |

| Male | 104 (46.0) | 115 (50.0) | 0.4007 |

| Female | 122 (54.0) | 115 (50.0) | |

| Weight, kg | 63.15 ± 13.42 | 63.56 ± 12.75 | 0.7377 |

| Height, cm | 159.81 ± 9.23 | 161.05 ± 9.43 | 0.1558 |

| Duration of CLBP, years | 10.3 ± 10.6 | 9.8 ± 10.1 | 0.6442 |

| BPI average pain (0–10) | 5.1 ± 1.0 | 5.1 ± 1.1 | 0.6165 |

| Pretreatment (physical therapy) | 120 (53.1) | 119 (51.7) | 0.7793 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

BPI indicates Brief Pain Inventory; CLBP, chronic low back pain.

*The data were analyzed using Welch's t test for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for categorical variables at the significance level of 0.15.

Efficacy

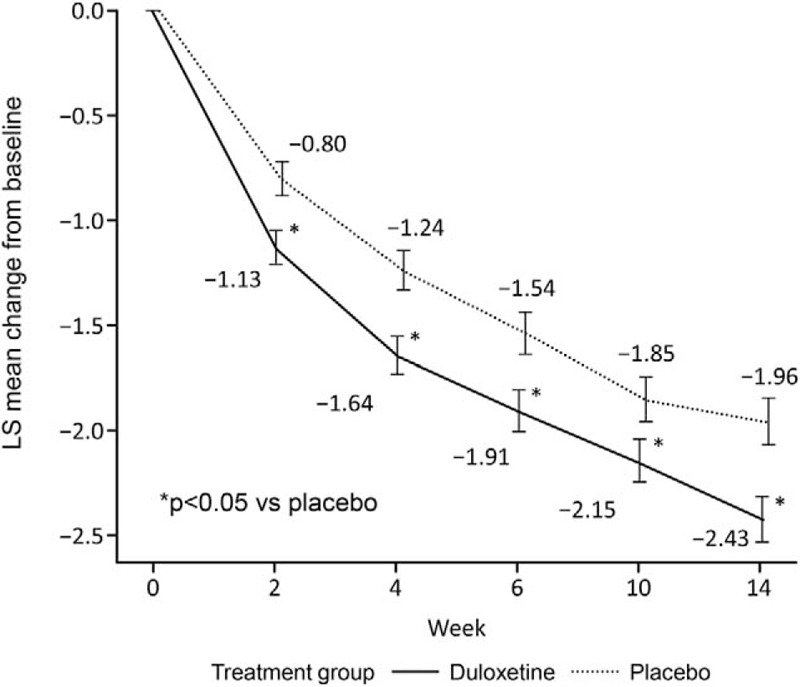

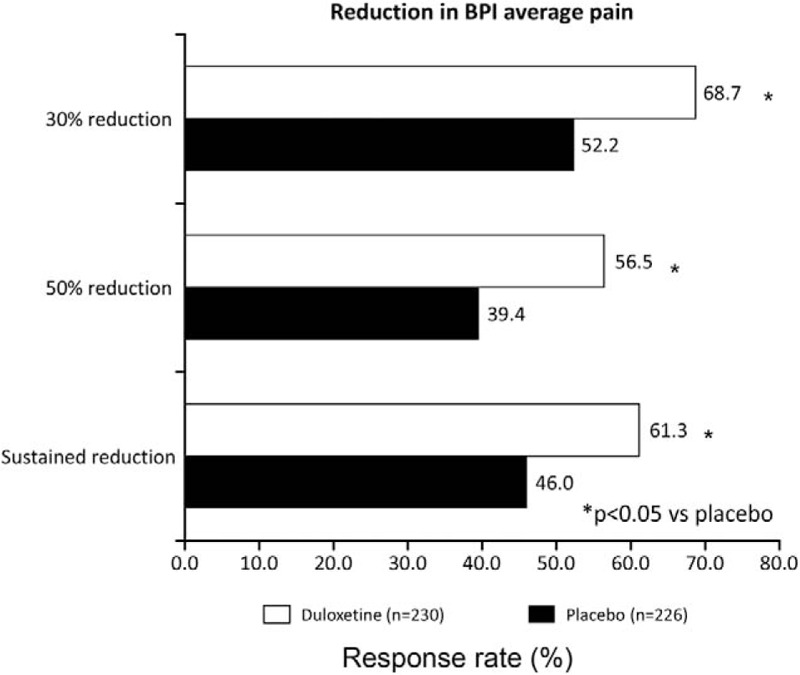

Figure 2 shows the changes over time in least squares (LS) mean ( ± SE) BPI average pain score up to Week 14 (primary endpoint) in both groups. The change in BPI average pain from baseline to Week 14 was −2.43 ± 0.11 in the duloxetine group and −1.96 ± 0.11 in the placebo group, with a between-group difference (95% confidence interval) of −0.46 (−0.77 to −0.16) (P = 0.0026). Furthermore, at all other evaluation time points, a significantly greater improvement in BPI average pain was observed in the duloxetine group than in the placebo group. The proportions of patients with 30% reduction, 50% reduction, and sustained reduction of the BPI average pain score in each group are shown in Figure 3; in each of the three response rate categories, the proportion of patients was significantly higher in the duloxetine group than in the placebo group (P = 0.0003, 0.0003, and 0.0012, respectively) (Figure 3). Moreover, in the post hoc analyses, the proportion of patients with a reduction in the BPI average pain score of ≥2 points at Week 14 was 69.6% and 54.4% in the duloxetine and placebo groups, respectively (P = 0.0010 by the Mantel-Haenszel test).

Figure 2.

Change in the Brief Pain Inventory average pain score in the full analysis set (MMRM analysis). Data are presented as adjusted mean ± standard error. LS indicates least squares; MMRM, mixed-effects model repeated measures.

Figure 3.

Response rates according to the BPI average pain score in the full analysis set. BPI indicates Brief Pain Inventory.

Changes in the secondary efficacy measures at Week 14 are shown in Table 2. Significantly, higher improvement in PGI-I and CGI-S was observed at Week 14 in the duloxetine group compared with the placebo group. In addition, in most of the secondary efficacy measures related to pain, significant pain reduction was observed in the duloxetine group compared with the placebo group, with significant improvement in the RDQ-24. Table 3 shows the categorical distribution of the PGI-I results at the final evaluation. The ratio between the direct and indirect effect of duloxetine is shown in Figure 4.

TABLE 2.

Least-squares Mean Changes in Secondary Efficacy Measures From Baseline to Week 14 of Treatment

| Placebo N = 226 | Duloxetine N = 230 | ||||

| Baseline Mean ± SD (n) | Week 14 LS Mean Change ± SE (n) | Baseline Mean ± SD (n) | Week 14 LS Mean Change ± SE (n) | ||

| BPI-average pain | |||||

| MMRM | 5.09 ± 1.04 (226) | −1.96 ± 0.11 (200) | 5.14 ± 1.11 (230) | −2.43 ± 0.11 (209) | 0.0026‡ |

| LOCF | 5.09 ± 1.04 (226) | −1.83 ± 0.11 (226) | 5.14 ± 1.11 (230) | −2.29 ± 0.11 (230) | 0.0024‡ |

| BOCF | 5.09 ± 1.04 (226) | −1.74 ± 0.11 (226) | 5.14 ± 1.11 (230) | −2.19 ± 0.11 (230) | 0.0034‡ |

| m-BOCF | 5.09 ± 1.04 (226) | −1.78 ± 0.11 (226) | 5.14 ± 1.11 (230) | −2.23 ± 0.11 (230) | 0.0034‡ |

| BPI-other pain | |||||

| Worst pain, MMRM | 6.60 ± 1.26 (226) | −2.33 ± 0.13 (200) | 6.63 ± 1.30 (230) | −2.63 ± 0.13 (209) | 0.1010 |

| Least pain, MMRM | 3.41 ± 1.58 (226) | −1.19 ± 0.11 (200) | 3.53 ± 1.63 (230) | −1.69 ± 0.10 (209) | 0.0009‡ |

| Right now pain, MMRM | 4.87 ± 1.45 (226) | −2.03 ± 0.12 (200) | 4.76 ± 1.61 (230) | −2.42 ± 0.12 (209) | 0.0230‡ |

| Diary (24-h average pain), MMRM | 4.88 ± 1.07 (226) | −1.73 ± 0.11 (202) | 4.94 ± 1.15 (230) | −2.15 ± 0.10 (210) | 0.0049‡ |

| Diary (worst pain), MMRM | 6.30 ± 1.20 (226) | −1.91 ± 0.12 (202) | 6.32 ± 1.22 (230) | −2.25 ± 0.12 (210) | 0.0442‡ |

| BPI interference, MMRM | |||||

| Activity | 4.05 ± 2.11 (226) | −2.16 ± 0.13 (200) | 4.36 ± 2.17 (230) | −2.46 ± 0.13 (209) | 0.0874 |

| Mood | 3.31 ± 2.27 (226) | −1.83 ± 0.11 (200) | 3.43 ± 2.39 (230) | −2.15 ± 0.11 (209) | 0.0436‡ |

| Walk | 3.53 ± 2.36 (226) | −1.92 ± 0.11 (200) | 3.40 ± 2.37 (230) | −2.05 ± 0.11 (209) | 0.3902 |

| Work | 3.91 ± 2.30 (226) | −2.17 ± 0.12 (200) | 3.93 ± 2.37 (230) | −2.17 ± 0.12 (209) | 0.9910 |

| Relate | 2.10 ± 2.22 (226) | −0.98 ± 0.10 (200) | 1.91 ± 2.12 (230) | −1.02 ± 0.10 (209) | 0.7848 |

| Sleep | 2.65 ± 2.42 (226) | −1.40 ± 0.11 (200) | 2.63 ± 2.33 (230) | −1.41 ± 0.11 (209) | 0.9424 |

| Enjoy | 2.86 ± 2.41 (226) | −1.48 ± 0.11 (200) | 2.77 ± 2.30 (230) | −1.52 ± 0.11 (209) | 0.7932 |

| Average of 7 questions | 3.20 ± 1.92 (226) | −1.70 ± 0.10 (200) | 3.20 ± 1.90 (230) | −1.83 ± 0.10 (209) | 0.3761 |

| CGI severity, MMRM | 4.22 ± 0.71 (226) | −1.17 ± 0.06 (200) | 4.23 ± 0.66 (230) | −1.46 ± 0.06 (209) | 0.0019‡ |

| PGI improvement, MMRM | − | 2.76 ± 0.07 (200)* | − | 2.46 ± 0.07 (209)* | 0.0026‡ |

| RDQ-24, LOCF | 7.77 ± 4.77 (226) | −3.23 ± 0.22 (226) | 7.59 ± 4.38 (230) | −3.86 ± 0.22 (230) | 0.0439‡ |

| EQ-5D, LOCF | 0.69 ± 0.10 (226) | 0.08 ± 0.01 (226) | 0.69 ± 0.11 (230) | 0.09 ± 0.01 (230) | 0.5237 |

| SF-36, LOCF | |||||

| Physical functioning | 72.52 ± 19.53 (226) | 7.20 ± 0.80 (226) | 71.87 ± 18.30 (230) | 8.47 ± 0.79 (230) | 0.2581 |

| Role-Physical | 71.79 ± 22.07 (226) | 10.00 ± 1.16 (226) | 70.41 ± 22.28 (230) | 10.58 ± 1.15 (230) | 0.7208 |

| Bodily pain | 48.96 ± 11.76 (226) | 11.01 ± 0.95 (226) | 49.11 ± 12.24 (230) | 12.56 ± 0.94 (230) | 0.2487 |

| General health | 58.35 ± 16.78 (226) | 3.78 ± 0.86 (226) | 58.54 ± 16.53 (230) | 6.72 ± 0.85 (230) | 0.0151‡ |

| Vitality | 57.44 ± 17.35 (226) | 4.41 ± 0.97 (226) | 59.78 ± 17.61 (230) | 5.56 ± 0.97 (230) | 0.4000 |

| Social functioning | 82.25 ± 20.83 (226) | 4.77 ± 1.01 (226) | 81.79 ± 20.78 (230) | 6.40 ± 1.00 (230) | 0.2529 |

| Role-emotional | 80.57 ± 22.57 (226) | 6.18 ± 1.14 (226) | 82.14 ± 23.22 (230) | 5.78 ± 1.13 (230) | 0.8042 |

| Mental health | 72.99 ± 16.69 (226) | 2.42 ± 0.82 (226) | 73.67 ± 16.37 (230) | 5.63 ± 0.81 (230) | 0.0058‡ |

| WPAI, LOCF† | |||||

| Work time missed | 0.01 ± 0.05 (140) | 0.02 ± 0.01 (143) | 0.02 ± 0.08 (135) | −0.01 ± 0.01 (140) | 0.0460‡ |

| Impairment at work | 0.31 ± 0.24 (140) | −0.09 ± 0.02 (143) | 0.29 ± 0.24 (136) | −0.13 ± 0.02 (140) | 0.0753 |

| Work productivity loss | 0.31 ± 0.25 (140) | −0.09 ± 0.02 (143) | 0.30 ± 0.24 (135) | −0.13 ± 0.02 (140) | 0.0795 |

| Work activity impairment | 0.35 ± 0.22 (226) | −0.12 ± 0.01 (226) | 0.34 ± 0.23 (230) | −0.14 ± 0.01 (230) | 0.1466 |

BOCF indicates Baseline Observed Carried Forward; BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; CGI, Clinical Global Impressions; EQ-5D, European QOL Questionnaire–5 Dimension; LOCF, Last Observation Carried Forward; m-BOCF, modified BOCF; MMRM, mixed-effects model repeated measures; PGI, Patient's Global Impression; RDQ-24, Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire; SF-36, 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey; WPAI, Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Instrument.

*LS mean ± SE at week 14.

†Work time missed, impairment at work, and work productivity loss were assessed only in patients who were actively employed throughout the examination period.

‡Indicates statistical significance.

TABLE 3.

Categorical Distribution of Patient's Global Impression of Improvement Results at the Final Evaluation

| Category | Placebo n = 226 | Duloxetine n = 230 | P |

| Improved* | 163 (72.1) | 191 (83.0) | 0.0067 |

| Unchanged | 59 (26.1) | 34 (14.8) | |

| Worsened† | 4 (1.8) | 5 (2.2) |

Data are presented as n (%).

*The “Improved” category included patients who responded “Very much improved”, “Much improved”, or “Minimally improved”.

†The “Worsened” category included patients who responded “Very much worse”, “Much worse”, or “Worse”.

Figure 4.

Ratio between direct and indirect effects.

Safety

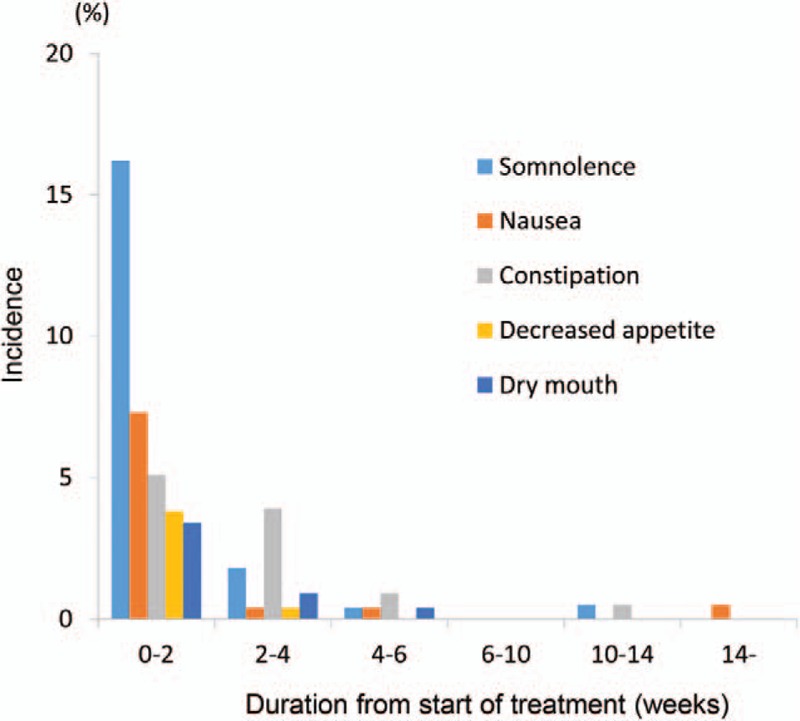

No deaths were reported during the study. SAEs occurred in four patients (cerebral hemorrhage, gastric polyps, urethral calculus, and intervertebral disc protrusion) in the duloxetine group and four patients (osteoarthritis, pneumococcal pneumonia, bacterial pneumonia, and hemothorax) in the placebo group. A causal relationship with the study drug was denied for all events. AEs occurring at a significantly higher incidence in the duloxetine group compared with the placebo group were somnolence, constipation, nausea, dizziness, and dry mouth (Table 4). The most common ADRs (at an incidence of ≥3%) observed within the first 2 weeks after treatment initiation occurred in the early phase of treatment in most patients, and their incidence tended not to increase with dose escalation. (Figure 5). No obvious changes attributable to duloxetine were observed in laboratory tests; blood pressure, pulse, and body weight measurements; or electrocardiogram findings. In the post hoc analyses, falls occurred in 10.3% (24/232) and 8.0% (18/224) of patients in the duloxetine and placebo groups, respectively (P = 0.4217). No apparent suicide risk was observed according to the C-SSRS.

TABLE 4.

Adverse Events That Occurred at an Incidence of ≥5%

| Placebo n = 224 | Duloxetine n = 234 | P | |

| Constipation | 5 (2.2) | 25 (10.7) | 0.0002* |

| Nausea | 6 (2.7) | 21 (9.0) | 0.0049* |

| Dry mouth | 0 (0.0) | 14 (6.0) | 0.0001* |

| Nasopharyngitis | 39 (17.4) | 26 (11.1) | 0.0610 |

| Contusion | 7 (3.1) | 16 (6.8) | 0.0867 |

| Somnolence | 16 (7.1) | 45 (19.2) | 0.0002* |

| Dizziness | 2 (0.9) | 15 (6.4) | 0.0020* |

Data are presented as n (%).

*Indicates statistical significance.

Figure 5.

Incidence of the most common adverse drug reactions (ADRs) (those that occurred at an incidence of 3% or higher within 2 weeks of starting administration).

DISCUSSION

The current study found that duloxetine was superior to placebo in the primary and many secondary efficacy measures, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies conducted overseas.11–13 The difference (95% confidence interval) in the change in BPI average pain at 14 weeks of treatment between the treatment groups was −0.46 (−0.77 to −0.16) (P = 0.0026), confirming the superiority of duloxetine over placebo. In addition, regarding pain reduction, a reduction of 2 points or at least 30% in the Numeric Rating Scale is generally considered as a clinically significant change.28 In this study, the proportion of patients with a reduction of 2 points or more in BPI average pain at Week 14 and that of patients with a 30% or 50% pain reduction were significantly higher in the duloxetine group than in the placebo group (P = 0.0010, 0.0003, and 0.0003, respectively). Regarding the category analysis of PGI, improvement was reported by a significantly higher proportion of patients in the duloxetine group than in the placebo group (P = 0.0067). In the current study, the ratio of the direct analgesic effect of duloxetine was as high as 97.3%, suggesting that duloxetine has analgesic activity independent of its antidepressant effect.

The goal of chronic pain treatment is QOL improvement. In this study, RDQ-24 scores, a low back pain-specific QOL measurement, improved significantly in the duloxetine group compared with the placebo group, which suggests that duloxetine is an effective medication for CLBP patients.

Significant improvements in the primary and many secondary efficacy measures were shown with duloxetine administered once daily compared with placebo. In general, patient adherence increases as dosing frequency decreases.29 The dosage regimens of many drugs approved for LBP in Japan require multiple daily doses. Therefore, a once-daily dosing regimen of duloxetine may be useful from the standpoint of patient adherence.

This is the first study to report the efficacy of an SNRI in Japanese CLBP patients. A similar pattern and magnitude of pain reduction with duloxetine treatment was also observed in studies of other chronic pain conditions, including diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain,15,30–32 pain associated with fibromyalgia,16,33,34 and pain caused by osteoarthritis.35,36 This consistent finding suggests that the analgesic efficacy of duloxetine across distinctively different chronic pain states may be caused by a single, common central mechanism of action-potentiation of descending inhibitory pain pathways.37 The current study reported the effectiveness of duloxetine as monotherapy in patients responding poorly to NSAIDs. Because duloxetine has a different mechanism of action from NSAIDs and acetaminophen, used as the first-line treatment for LBP, duloxetine is expected to provide a new treatment option for patients with CLBP. Moreover, previous studies conducted overseas have reported its effectiveness in NSAID-naïve patients. Taken together, these findings suggest that duloxetine may play a significant role in the future treatment of CLBP in Japan. In the current study, the safety profile of duloxetine was similar to that from previous studies in patients with approved indications.14–16 Although the discontinuations because of AEs did not differ significantly between duloxetine and placebo, the discontinuations because of ADRs were significantly more frequent in the duloxetine group.

The current study has some limitations. First, the treatment period was relatively short, and the treatment for CLBP requires a longer period. Second, the current study only included patients responding poorly to NSAIDs, and no confirmation was made regarding the efficacy of duloxetine in Japanese NSAID-naïve patients. A long-term extension study that included NSAID-naïve patients was conducted separately and will be submitted for publication in the near future. Finally, this study lacks an active comparator arm, which would perhaps have allowed for comparison of duloxetine efficacy with at least one of the commonly used therapeutic options.

In conclusion, the current study findings suggest that duloxetine 60 mg once daily is effective and well tolerated in the treatment of Japanese patients with CLBP.

Key Points

This is the first study to report the efficacy and safety of duloxetine 60 mg once daily for the treatment of Japanese patients with CLBP.

In this 14-week, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled study, 458 Japanese patients with CLBP were randomized to treatment with either duloxetine 60 mg once daily or placebo.

The duloxetine group showed a significantly greater improvement in the BPI average pain score at Week 14 (primary efficacy measure) than the placebo group, and in many secondary measures such as BPI pain (least pain, pain right now), PGI-I, CGI-S, and RDQ.

The safety profile of duloxetine was similar to that from previous studies in patients with approved indications.

The current study findings suggest that duloxetine 60 mg once daily is effective and well tolerated in the treatment of Japanese patients with CLBP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the investigators from the following 58 study sites who cooperated in this research (in no particular order): Hakodate Ohmura Orthopedics, Asano Orthopedic Clinic, Takahashi Orthopedic Clinic, Maehara Orthopedics, Higashimaebashi Orthopedics, Segawa Hospital, Saitamakinen Hospital, Wakasa Clinic, Kobayashi Orthopedics, Ozawa Orthopedics, Saino Clinic, Hanazono Orthopedics and Internal Medicine Clinic, Yamazaki Orthopedics Clinic, Jin Orthopedic Clinic, Shiraishi Orthopedic Clinic, Masaki Orthopedics, Sekimachi Hospital, Sato Orthopedics, Tsukahara Orthopedics, Koenji Orthopedics, Kyobashi Orthopedics, Musashino Clinic, Otakibashi Orthopedics, Wada Orthopedic Clinic, Oimachi Orthopedic Clinic, Nishiwaseda Orthopedics, Meguro Yuai Clinic, Miya Orthopedics, Ando Orthopedics, Morinosato Hospital, Kubodera Orthopedics, Shibata Orthopedics, Akiyama Orthopedics, Aoki Orthopedics, Keyaki-dori Orthopedics, Nakatsu Hospital, Amagasaki Central Hospital, Yamamoto Rheumatology Clinic, Omuro Orthopedic Clinic, Mitta Orthopedics, Ohta Orthopedic Clinic, Takagi Hospital, Nagata Orthopedic Hospital, Morooka Orthopedic Clinic, Nakayama Orthopedics, Shinkomonji Hospital, Sata Orthopedic Hospital, Matsunaga Orthopedics, Kuroda Orthopedics, Fukahori Orthopedic Clinic, Fukushima Orthopedic Clinic, Hyakutake Orthopedic Hospital, Metabaru Orthopedics, Suga Orthopedic Hospital, Fukuda Orthopedics, Fujigaki Clinic, Nagamine Orthopedics, and Hashiguchi Orthopedics.

The authors would also like to acknowledge the editorial assistance provided by Dr. Michelle Belanger of Edanz Group Ltd. in the preparation of this article.

Footnotes

The drug that is the subject of this article is being evaluated as part of a Japanese national protocol for assessing the efficacy and safety of duloxetine monotherapy in Japanese patients with chronic low back pain.

Shionogi & Co. Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., and Eli Lilly and Company funds were received in support of this work.

Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work: consultancy, employment.

References

- 1.Fujii T, Matsudaira K. Prevalence of low back pain and factors associated with chronic disabling back pain in Japan. Eur Spine J 2013; 22:432–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshimura N, Muraki S, Oka T, et al. Epidemiology of low back pain: from a large scale epidemiologic survey “ROAD”. Nippon Seikei Geka Gakkai Zasshi 2010; 84:437–439. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamura M, Nishiwaki Y, Ushida T, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic musculoskeletal pain in Japan: a second survey of people with or without chronic pain. J Orthop Sci 2014; 19:339–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pengel LH, Herbert RD, Mather CG, et al. Acute low back pain: systematic review of its prognosis. BMJ 2003; 327:323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, et al. COST B13 Working Group on Guidelines for Chronic Low Back Pain. Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J 2006. S192–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou R, Huffman LH. American Pain Society. Medications for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147:505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA). Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Low Back Pain Nankodo Co., Ltd., Tokyo 2012 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Tulder MW, Scholten RJ, Koes BW, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000; 25:2501–2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gor AP, Saksena M. Adverse drug reactions of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in orthopedic patients. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2011; 2:26–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones CK, Peters SC, Shannon HE. Efficacy of duloxetine, a potent and balanced serotonergic and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor, in inflammatory and acute pain models in rodents. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2005; 312:726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skljarevski V, Zhang S, Desaiah D, et al. Duloxetine versus placebo in patients with chronic low back pain: a 12-week, fixed-dose, randomized, double-blind trial. J Pain 2010; 11:1282–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skljarevski V, Desaiah D, Liu-Seifert H, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010; 35:E578–E585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skljarevski V, Ossanna M, Liu-Seifert H, et al. A double-blind, randomized trial of duloxetine versus placebo in the management of chronic low back pain. Eur J Neurol 2009; 16:1041–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higuchi T, Murasaki M, Kamijima K. Clinical evaluation of duloxetine in the treatment of major depressive disorder—placebo-and paroxetine-controlled double-blind comparative study. Jpn J Clin Psychopharmacol 2009; 12:1613–1634. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hitoshi Yasuda, Hotta N, Nakao K, et al. Superiority of duloxetine to placebo in improving diabetic neuropathic pain: results of a randomized controlled trial in Japan. J Diabetes Investig 2011; 2:132–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murakami M, Osada K, Mizuno H, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of duloxetine in Japanese fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Res Ther 2015; 17:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uki J, Mendoza T, Cleeland CS, et al. A brief cancer pain assessment tool in Japanese: the utility of the Japanese Brief Pain Inventory—BPI-J. J Pain Symptom Manage December 1998; 16:364–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N. I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry 2011; 168:1266–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare publication (ADM). Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976. 76–338. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1983; 8:141–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukuhara S. RDQ (Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire) Japanese Manual. Tokyo: Iryobunkasha, 2004. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzukamo Y, Fukuhara S, Kikuchi S, et al. Validation of the Japanese version of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire. J Orthop Sci 2003; 8:543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fukuhara S, Bito S, Green J, et al. Translation, adaptation, and validation of the SF-36 Health Survey for use in Japan. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51:1037–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukuhara S, Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, et al. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity of the Japanese SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51:1045–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kind P. Spilker B. The EuroQoL instrument: An index of health-related quality of life. Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials 2nd ed.Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 1993; 4:353–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008; 9:105–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther 2001; 23:1296–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldstein DJ, Lu Y, Detke MJ, et al. Duloxetine vs. placebo in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy. Pain 2005; 116:109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raskin J, Pritchett YL, Wang F, et al. A double-blind, randomized multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain Med 2005; 6:346–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wernicke JF, Pritchett YL, D'Souza DN, et al. A randomized controlled trial of duloxetine in diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Neurology 2006; 67:1411–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnold LM, Clauw DJ, Wohlreich MM, et al. Efficacy of duloxetine in patients with fibromyalgia: pooled analysis of 4 placebo-controlled clinical trials. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 11:237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choy EH, Mease PJ, Kajdasz DK, et al. Safety and tolerability of duloxetine in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia: pooled analysis of data from five clinical trials. Clin Rheumatol 2009; 28:1035–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chappell AS, Ossanna MJ, Liu-Seifert H, et al. Duloxetine, a centrally acting analgesic, in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis knee pain: a 13-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pain 2009; 146:253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chappell AS, Desaiah D, Liu-Seifert H, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of duloxetine for the treatment of chronic pain due to osteoarthritis of the knee. Pain Pract 2011; 11:33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson MJ, Edwards SE, Iyengar S, et al. Depression and pain. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2009; 14:5031–5051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.