Abstract

Living tissues consist largely of cells and extracellular matrices (ECMs). The mechanical properties of ECM have been found to play a key role in regulating cell behaviors such as migration, proliferation, and differentiation. Although most studies to date have focused on elucidating the impact of matrix elasticity on cell behaviors, recent studies have revealed an impact of matrix viscoelasticity on cell behaviors and reported plastic remodeling of ECM by cells. In this study, we rigorously characterized the plasticity in materials commonly used for cell culture. This characterization of plasticity revealed time-dependent plasticity, or viscoplasticity, in collagen gels, reconstituted basement membrane matrix, agarose gels, alginate gels, and fibrin gels, but not in polyacrylamide gels. Viscoplasticity was associated with gels that contained weak bonds, and covalent cross-linking diminished viscoplasticity in collagen and alginate gels. Interestingly, the degree of plasticity was found to be nonlinear, or dependent on the magnitude of stress or strain, in collagen gels, but not in the other viscoplastic materials. Viscoplastic models were employed to describe plasticity in the viscoplastic materials. Relevance of matrix viscoplasticity to cell-matrix interactions was established through a quantitative assessment of plastic remodeling of collagen gels by cells. Plastic remodeling of collagen gels was found to be dependent on cellular force, mediated through integrin-based adhesions, and occurred even with inhibition of proteolytic degradation of the matrix. Together, these results reveal that matrix viscoplasticity facilitates plastic remodeling of matrix by cellular forces.

Introduction

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a complex assembly of structural proteins with distinctive physical and biochemical properties, which provides a local microenvironment in which cells reside. The structural composition of ECM varies between different tissues and locations. One particularly important component is type I collagen, which primarily determines mechanical functions of connective tissues (1). Type I collagen is highly organized into thin fibrils that are subsequently aggregated to fibers, and these fibers can form gels in vitro. In contrast to the type-I-collagen-rich connective tissues, basement membrane, a thin layer of matrix that connects the epithelium to the connective tissues, does not contain type I collagen and is composed primarily of laminin and collagen IV. A mix of these proteins extracted from the Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm tumor forms a nonfibrous matrix when reconstituted in vitro (2). In addition, fibrin is a fibrous protein involved in blood clotting and forms a gel when polymerized in vitro (3). These ECM components have been widely used as three-dimensional culture models to mimic physiological environments and understand cell-matrix interactions, with collagen gels, reconstituted basement membrane (rBM) matrix, and fibrin gels serving as standard models for connective tissues (4), culture of epithelium (5), and wound healing (6), respectively. In addition to these materials, hydrogels of natural or synthetic polymers have been developed as synthetic extracellular matrix. Agarose and alginate are natural polymers derived from seaweed and gels of agarose and alginate have been used for cancer cell spheroid assays (7) and 3D cell culture (8). Finally, polyacrylamide gels have been synthesized for use as two-dimensional substrates for cell culture (9, 10).

It has been established that cells sense and respond to the mechanical properties of the ECM. Studies investigating the influence of mechanical properties of ECM on cells have found that the elastic modulus of the ECM plays a key role in regulating cell behaviors such as differentiation, proliferation, migration, and malignancy (9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14). These studies have broadly suggested that sensing of these mechanical properties, or the process of mechanotransduction, is mediated through cells gauging resistance to traction forces that they exert on the substrate (11, 12). However, many ECMs are viscoelastic, or exhibit a time-dependent elastic modulus (15). Viscoelastic materials display both viscous and elastic responses to a deformation or a force (16). Recent studies have revealed that ECM viscoelasticity can also influence cell behaviors such as proliferation, spreading, and stem cell fate (15, 17, 18, 19). Viscoelasticity arises from dissipation of energy, which could occur from a variety of molecular mechanisms, including movement of fluid (20, 21) and breaking of weak bonds (3, 22, 23) in matrices. In the case of viscoelasticity associated with weak bonds, deformations can be plastic, with bonds unbinding, allowing matrix to flow, and later forming or rebinding, leading to the property of viscoplasticity, or time-dependent plasticity, in the materials (24). However, there has been almost no characterization of viscoplasticity in materials that are commonly used for cell culture.

Recent evidence indicates that matrix plasticity may be relevant to cell-matrix interactions, with cells having been found to induce plastic remodeling when cultured in some materials. It has been reported that the orientation of matrix fibers near cells is realigned for cells cultured within collagen and fibrin gels (25, 26, 27). Importantly, realignment persisted after the cells were removed in one study, demonstrating that the structural reorganization was plastic or permanent (26). The origins of this plastic remodeling are likely to be from the physical forces generated by the cells that are applied to the ECM. However, cells also secrete matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), enzymes that biochemically degrade matrices, to facilitate remodeling of the adjacent ECM (28). For example, it is thought that cancer cells infiltrate local tissues by using MMPs to cleave impending collagen fibers and negotiate the structural barriers of ECM (29, 30, 31). The contributions of protease degradation and cellular force to plastic remodeling of the ECM by cells remain unclear.

Here, we characterized the viscoplasticity of various cell-culture materials and found that collagen gels, rBM matrix, fibrin gels, agarose gels, and alginate gels exhibit viscoplasticity, whereas covalently cross-linked polyacrylamide and alginate gels do not. Interestingly, collagen gels displayed stress-dependent plasticity in contrast to the stress-independent plasticity in the other viscoplastic materials. Mechanical models with a nonlinear plastic flow element captured the stress-dependent plasticity in collagen gels, whereas mechanical models with a linear plastic flow element described stress-independent plasticity in the other materials. Furthermore, we demonstrated the capability of cellular force to plastically deform collagen fibers and developed a new method, to our knowledge, to quantify the degree of plastic remodeling in the collagen gels. By inhibiting protease activity, we attributed the observed plastic remodeling to cellular force, not proteolytic degradation. Together, the mechanical measurements, modeling, and quantitative assessment of ECM remodeling provide a framework for characterizing the viscoplasticity of ECM and assessing the role of ECM plasticity in cell-ECM interactions.

Materials and Methods

Material preparation for mechanical testing

All materials were gelled within the rheometer geometry for mechanical testing. Collagen type Ι (Corning, Corning, NY) was prepared in ice by diluting with 10× and 1× Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) to achieve a final concentration of 1 mg/mL (25). The collagen solution was immediately deposited on the rheometer plates before experiments and heated to 37°C. Matrigel (Corning) was used as the rBM matrix at a concentration of 9.2 mg/mL. The gelation of rBM was initiated by heating to 37°C. Low-gelling-temperature agarose (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in 1× DMEM to a final concentration of 1% w/v at pH 7.4, and the solution was heated before the experiments. The gelation of agarose was performed on the rheometer cooled to 25°C. Polyacrylamide gels were prepared by mixing acrylamide (3%, v/v) and bis-acrylamide (0.15%, v/v) with tetramethylethylenediamine and ammonia persulfate. Sodium alginate rich in guluronic acid blocks and with a high molecular weight (280 kDa, LF20/40) was puchased from FMC BioPolymer (Philadelphia, PA), and prepared according to a previously described method (15). Briefly, alginate was dialyzed against deionized water for 2–3 days (molecular weight cutoff of 3500 Da), filtered with activated charcoal followed by sterile filtration, lyophilized, and then reconsituted at 2.5 wt % in serum-free media or in MES buffer (0.1 M MES and 0.3 M NaCl, pH 6.5) for a stock solution. Alginate gels were formed by either covalent cross-linking or ionic cross-linking. For ionically cross-linked gels, 0.8 mL of alginate in serum-free DMEM was rapidly mixed with 0.2 mL DMEM containing the ionic cross-linker (CaSO4) to a final concentration of 2% alginate and 15.5 mM CaSO4. For covalently cross-linked gels, 0.8 mL of alginate in MES buffer was mixed with 0.2 ml MES buffer containing 2.5 mg/mL of 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (Sigma Aldrich), 50 mg/mL EDC and 0.8 mg/mL adipic acid dihydrazide (Sigma Aldrich). The mix for ionically or covalently cross-linked gels was deposited directly on the surface plate of the rheometer immediately after mixing and allowed to gel for 2 h for ionically cross-linked gels or 12 h for covalently cross-linked gels. For preparation of fibrin gels, human fibrinogen with factor XΙΙΙ (Enzyme Research Labs, South Bend, IN) diluted by 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer at pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl and 10 mM CaCl2, was mixed with human thrombin (Enzyme Research Labs) to a final concentration of 2 mg/mL fibrinogen and 0.6 U/mL thrombin.

Covalent cross-linking of collagen gels

To covalently cross-link collagen gels, glutaraldehyde (GTA; Sigma Aldrich) and tissue transglutaminase (tTG; Sigma Aldrich) were used as cross-linking agents. GTA was diluted to 0.2% in 1× DMEM and deposited around the collagen gels between the plate of the rheometer after the collagen had gelled for at least 20 min. After deposition of the GTA, the GTA was allowed to diffuse into the collagen gels and cross-link it for 2 h before experiments. After the storage modulus of the collagen gels cross-linked by GTA reached an equilibrium value, creep and recovery tests were performed. To cross-link collagen gels with tTG, the tTG was pretreated in 2 mM dithiothreitol in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) for 10 min at room temperature before adding to a final buffer containing 5 mM CaCl2. Collagen stock solution was directly mixed with the pretreated tTG solution containing 2 mM dithiothreitol and 5 mM CaCl2 in 50 mM Tris buffer to a final concentration of 1 mg/mL collagen and 20 μg/mL tTG immediately before deposition on the rheometer plates. After gelation for 5 h, the creep and recovery tests were performed with the collagen gel cross-linked by tTG.

Creep and recovery tests

Creep and recovery tests were performed to assess plasticity in the different materials. These tests were performed using an AR-G2 stress-controlled rheometer (TA Instruments, Newcastle, DE) equipped with 25-mm-diameter top and bottom plate geometry. The stainless steel surfaces of the plates were used for all of the materials except for collagen gels, since collagen gels can slip on stainless steel surfaces (3). Poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips (25 mm; Neuvitro, El Monte, CA) were glued to the surface to improve the attachment of collagen gels and prevent their slippage from the surface (3). All the materials were deposited onto the bottom surface of the plate immediately before gelation, and the top plate was brought down rapidly to form a 25-mm-diameter disk of sample with a thickness of ∼400 μm between the two plates. Mineral oil (Sigma Aldrich) was deposited around the exposed gel surface between the rheometer plates to prevent dehydration of the samples, except in the experiments with cross-linked collagen gels. During gelation, the storage modulus was monitored with continuous oscillations at a strain of 0.01 and frequency of 1 rad/s. Creep and recovery tests were performed after the storage modulus reached an equilibrium value. In creep and recovery tests, a constant stress ranging from 1 to 100 Pa was applied for 300–3600 s while strain in response to the stress was measured over time. Then, the stress was removed in recovery tests and the strain was monitored until it reached equilibrium. The degree of plasticity is defined as the ratio of irreversible strain after recovery tests to the maximum strain at the end of the creep tests, or

| (1) |

where εmaximum and εirreversible represent the maximum strain at the end of the creep test and the irreversible strain after the recovery test, respectively.

Mechanical modeling

To describe the mechanical behaviors of the cell-culture materials measured in the creep and recovery tests, we incorporated viscoplastic elements into traditional linear viscoelastic models. Linear viscoelastic models consist of combinations of springs and dampers that describe viscoelastic behaviors of materials, whereas viscoplastic models are only engaged when the materials are subjected to plastic deformation. For the viscoelastic models, the standard linear solid (SLS) model and the Burgers model were employed. The governing equation (16) for the SLS can be described as

| (2) |

whereas that for the Burgers model can be written as

| (3) |

where σ and ε represent stress and strain, and η1, η2, μ1, and μ2 represent viscosities of dashpots and spring constants of springs, respectively. The instantaneous elastic modulus of a material at initial creep tests is determined by μ2, whereas the characteristic time for viscous response is determined as . Under creep and recovery tests, the input of the governing equations started with a constant stress, σ = σ0, for the creep test, followed by removal of the stress, σ = 0, for the recovery. After establishing a viscoelastic model to use with a given material, a viscoplastic element is added. The linear plastic flow model, the Bingham plastic model (32), is described as

| (4) |

where is the plastic strain rate to induce plasticity in mechanical models. In contrast to the linear plastic flow model, the nonlinear plastic flow model, the Norton-Hoff model (33), can also be incorporated as

| (5) |

where N is the nonlinear factor for the plastic flow. If N = 1, the response is the same as for the linear plastic flow model. The total strain, ε, is then composed of εe, elastic strain, εv, viscoelastic strain, and εP, plastic strain.

| (6) |

Cell culture, transfection, and cell lines

3T3 mouse fibroblast cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in DMEM (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone) and pen/strep (Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). For cells with fluorescently labeled F-actin, 3T3 cells were stably transfected with a PiggyBac vector containing RFP-Lifeact (34) to make a clonal 3T3:RFP-Lifeact cell line. Briefly, 3T3 cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At 24 h after transfection, the transfection medium was replaced with antibiotic selection medium, which consisted of complete medium containing 500 μg/mL G418 (Geneticin, InvivoGen, San Diego, CA), as in a previously published protocol (35). Transfected cells were maintained in selection medium for 10 days to select for stably transfected cells. Cells were then replated as single cells to form clonal cell lines. One clonal cell line confirmed for RFP-Lifeact expression was chosen and maintained in 500 μg/mL G418.

Cell experiments

For cell experiments, 3T3 cells were first suspended in complete medium containing 500 μg/mL G418. Type I collagen was diluted with 10× DMEM and the cell suspension to a final concentration of 1 mg/mL (25). The collagen solution was polymerized at 37°C and the cells within the collagen gels were incubated for a day before imaging. For blocking β1 integrin, a blocking antibody (ab24693, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) for β1 integrin was added in the medium to 20 μg/mL dilution. For MMP inhibition, GM6001 (Millipore, Billerica, MA) was added to the medium to a final concentration of 10 μM (36). For inhibition of actin polymerization, cytochalasin D (CytoD) was titrated in the medium to a concentration of 10 μM and 1 μM for high and medium CytoD experiments, respectively. To lyse cells, a lysing solution was made by adding 1% Triton X-100 and 50 μM Cyto D to the medium.

Imaging cells and collagen fiber architecture

Live-cell imaging and imaging of collagen fiber architecture were conducted using confocal microscopy. To analyze fiber orientation and plasticity of networks, images of collagen fibers were taken using a confocal reflectance microscopewith a 25×/0.95 NA water immersion objective (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and imaging at a wavelength of 639 nm. Fluorescence imaging of fluorescently labeled actin was conducted using the same objective. For the live-cell imaging in Movie S1 in the Supporting Material, a 63×/1.4 NA oil immersion objective (Leica) was used for imaging both collagen fibers and cells. All imaging experiments were conducted for cells in gels placed in a chamber slide system geometry (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica SP8), and images were taken at least 30 μm away from the bottom surface of the chamber slides.

Image analysis for collagen fibers

To quantify the orientation of collagen fibers, the images of collagen gels were analyzed using a previously described algorithm to detect fibers in the networks (23, 37). Briefly, a Gaussian filter was first used to smooth the images, and the smoothed images were transformed to binary images with a threshold so that fibers become foreground pixels. Next, the distance of each foreground pixel from the nearest background pixel was calculated. The calculated distances were evaluated to find the local maximal ridges, which were used as nucleation points. The trajectory of the fibers was defined by connecting nucleation points. The orientation of each fiber was calculated as the angle of the line connecting the end points of each fiber.

Visualization of collagen-gel structure under shear

To visualize the structural change in collagen gels under bulk shear, a customized shearing device was used (23). The device was composed of a transparent shear cell in which collagen gels were polymerized and planar shear deformation was applied and released. The device was mounted on a confocal microscope (Leica SP8) to allow simultaneous imaging of collagen fibers. The collagen-gel structure was imaged on the xy plane (Fig. S9) with confocal reflectance microscopy using a 25×/0.95 NA water immersion objective and a wavelength of 488 nm for excitation. A shear deformation of γ = 0.2 was applied to the gels for 5 min and then released. The images were analyzed using the method described above.

Characterization of collagen-gel remodeling by cells

Image analysis was used to quantitatively assess the extent to which remodeling of collagen gels by cells was plastic. First, the orientations of fibers with respect to specific points on the cell membrane were calculated. Fluorescent images of actin were used as a reference to select local points around the cell membrane. A few hundred local points were selected randomly along the cell periphery. The fiber orientation with respect to each local point around cells was calculated as the inner product of two unit vectors: one is the original unit vector of fibers and the other is the unit vector pointing each fiber from each local point (see Fig. 8 A). The absolute value of the inner product of the two unit vectors becomes closer to 1 as the angle of the two unit vectors becomes smaller, or when the collagen fiber is aligned in the direction of the specific point on the cell. The absolute values of the inner products were averaged along with distances and represented as the fiber orientation index (FOI). The FOI for an ideal random network can be calculated as ≈ 0.637, since the fiber orientation in the ideal random network has the same likelihood across all the range of angles. Then, plasticity is assessed based on comparison of the difference between the FOI after lysis of cells and the FOI at the beginning of culture to the difference between the FOI before lysis of cells and the FOI at the beginning of culture, or:

| (7) |

where rms represents the root mean square. This quantity gives the degree to which cell-induced reorientation of the collagen gels is plastic. As plasticity can only be determined given a sufficient level of deformation and realignment of the collagen gels, assessment of plasticity was performed only when the FOI was >0.647 before lysis. Both deformation and plasticity of the networks were significantly diminished with increased distance from cells, as the influence of cellular force is reduced at longer distances (Fig. S4). Therefore, network plasticity was only evaluated within 30 μm of the cells.

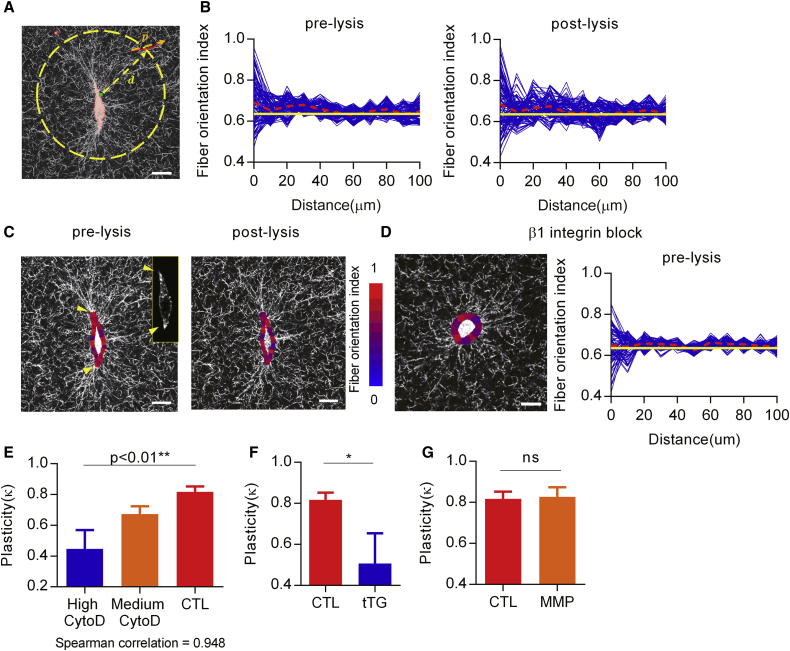

Figure 8.

Quantitative assessment reveals that plastic remodeling of collagen gels by cells is mediated by β1 integrin, the cross-linking state of the collagen gel, and the magnitude of cellular force, but not by proteolytic activities. (A) A schematic to describe the analysis of fiber orientation. Each fiber is represented with a vector, , that connects the end points of the fiber. Given a selected point along the cell periphery, another vector, , connects the point along the cell periphery to the center of vector . The length of this vector is used as a measure of the distance from the cell periphery to the fiber. (B) FOI as a function of distance from cells (left) before and (right) after lysing cells. Red dotted lines indicate the average value of the FOI at each distance, and yellow lines indicate the average value of the FOI at random networks, which is ∼0.637 (see Materials and Methods). (C) Image of cells in collagen gels prelysis (left) and postlysis (right) with a graphical representation of the FOI evaluated at local points on the cell boundary superimposed on the image. Yellow arrows represent the regions where collagen fibers are highly aligned and high FOI is measured; the scale bar for the FOI is located on the right. (Inset) a fluorescent image of actin. Yellow arrows inset indicate the regions where strong actin fluorescent emissions are detected. (D) Image of a cell in collagen gel under inhibition of β1-integrin binding with a blocking antibody, with a graphical representation of the FOI around the cell superimposed on the image. (E–G) Plasticity around cells assessed under inhibition of actin polymerization with CytoD (E), in covalently cross-linked collagen gels (F), and under inhibition of MMP activity with GM6001 (G). p-values are calculated by Spearman’s correlation in (E) and by Student’s t-test in (F) and (G). ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ns, no significant difference. Scale bar, 10 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

Measurements of plasticity in tissues

To assess the degree of plasticity in tissues, heart, lung, liver, and brain tissues were isolated from mice. Unconfined compressive creep and recovery tests were then performed using a mechanical tester (5848 MicroTester, Instron, High Wycombe, United Kingdom). The thickness of tissues was measured before the creep tests. In creep tests, a stress of ∼1 kPa was applied to the tissues for 5 min, and strain was recorded over time. Once creep tests had been completed, the tissues were allowed to recover for 10 min and the thickness of the tissues was measured after the recovery. The degree of plasticity of tissues was determined as the ratio of strain after the recovery to the maximum strain after the creep tests.

Results

Viscoplasticity of cell-culture materials

Plasticity is defined as the permanent strain remaining in a material after application and release of a stress, and it arises from irreversible changes in material structure induced by the stress. Plasticity in cell-culture materials can be assessed using creep and recovery tests. These tests involve measurement of strain during imposition of a constant stress (creep) over a certain period of time, followed by removal of the stress (recovery) (Fig. 1 A) (38, 39). Under a creep test, a viscoelastic material is initially strained, due to an elastic component, and then the strain can gradually increase over time in a process referred to as creep. Once the stress is removed to initiate the recovery test, the strain can exhibit an instantaneous reduction due to the elastic component of the material response and then gradually decrease over time due to viscoelastic behavior of the material. If the strain does not reach zero, then the material has undergone irreversible, or plastic, deformation due to the initially imposed strain.

Figure 1.

Creep and recovery tests characterize plasticity of cell-culture materials. (A) The schematic explains general features of the material response in a creep and recovery test. Initially, materials exhibit instantaneous elastic response to applied stress, and strain of materials gradually increases over time. At the end of the creep test, materials exhibit a maximum or total strain. After release of the creep test, materials undergo elastic and viscoelastic recovery, but may leave a residual, or irreversible, strain, which is indicative of plastic deformation. Also shown are typical mechanical responses of (B) collagen gels, (C) rBM matrix, (D) agarose gels, (E) alginate gels, (F) fibrin gels, and (G) polyacrylamide gels (PAM) under creep and recovery tests at different stresses. To see this figure in color, go online.

Creep and recovery tests on various cell-culture materials revealed a diverse set of responses (Fig. 1, B–G). Collagen gels and rBM matrix show higher levels of irreversible deformation than do agarose gels, ionically cross-linked alginate gels, and fibrin gels at similar levels of stress (Fig. 1, B–F) or strain (Fig. S1; Table S1). However, polyacrylamide gels do not exhibit any degree of irreversible deformation (Fig. 1 G). The degree of plasticity of these materials can be quantified based on the ratio of irreversible deformation to maximum deformation, or total strain, that the materials exhibit under the creep tests (Fig. 1 A). When increasing the timescale in the creep tests, the degree of plasticity of the plastic materials increased over time, whereas the polyacrylamide gels maintained an elastic response (Fig. 2). These results indicate the time dependence of plasticity, or viscoplasticity, in the cell-culture materials.

Figure 2.

Degree of plasticity in cell-culture materials is enhanced at increasing timescales of imposed stress. The degree of plasticity of (A) collagen gels, (B) rBM matrix, (C) agarose gels, (D) alginate gels, (E) fibrin gels, and (F) polyacrylamide gels are obtained as a function of different times of imposed creep, or creep time, during creep and recovery tests. To see this figure in color, go online.

Next, we tested the dependence of plasticity on the magnitude of stress. It has been reported that cells are able to exert stresses of up to hundreds of pascals in three-dimensional culture (40, 41, 42). A range of stresses up to 100 Pa were applied in creep tests while preserving the timescale of the creep and recovery tests. The degree of plasticity of collagen gels exhibited dependence on the stress; it was enhanced when stress increased and then became saturated at higher stresses (Fig. 3 A). In contrast, the degree of plasticity of the other materials did not depend on stress (Fig. 3, B–E). Collectively displaying the degree of plasticity as a function of stress at different timescales highlighted the distinct classes of plastic behavior and the different levels of intrinsic plasticity in the cell-culture materials (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Degree of plasticity is enhanced with increasing stress in collagen gels, but not in the other materials. The degree of plasticity of (A) collagen gels, (B) rBM matrix, (C) agarose gels, (D) alginate gels, and (E) fibrin gels, was obtained by creep and recovery tests at different stresses. Data are shown as the mean ± SD; n = 4. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 4.

Different cell-culture materials exhibit distinct behaviors of viscoplasticity. Shown is a plot of the degree of plasticity in tested materials as a function of stress for collagen gels (blue), rBM matrix (green), agarose gels (red), alginate gels (orange), and fibrin gels (purple). The type of line indicates the timescale for the creep test in the creep and recovery tests. Solid lines represent a creep time of 3600 s for all the tested materials except rBM matrix. The dash-dotted line for rBM matrix indicates a creep time of 1200 s, and the dashed lines represent a creep time of 300 s for all the tested materials. At increasing timescales, all the materials exhibit higher degrees of plasticity. To see this figure in color, go online.

After finding distinct behaviors of plasticity in collagen gels, we investigated the molecular origins of plasticity. Collagen gels form networks through weak bonds between fibers (3, 22, 23). Thus, we tested whether forming rigid covalent cross-links would impact the plasticity of collagen gels. Collagen gels covalently cross-linked with GTA or tTG displayed a diminished degree of plasticity (Fig. 5). Similarly, covalently cross-linked alginate gels are essentially elastic and exhibit a substantially reduced plasticity, compared to ionically cross-linked gels (Fig. S2). These results indicate that the plasticity is associated with weak bonds in the networks.

Figure 5.

Degree of plasticity is regulated by covalent cross-linking in collagen gels. The degree of plasticity for untreated, GTA-cross-linked, and tTG-cross-linked collagen gels was obtained by creep and recovery tests with a creep time of 3600 s. To see this figure in color, go online.

Mechanical modeling of plasticity in cell-culture materials

To model the mechanical response of the cell-culture materials during the creep test (Fig. 4), linear viscoelastic models were applied. The linear viscoelasticity of a material can be described by modeling the material as a combination of elastic springs and viscous dashpots. Two different viscoelastic models, the SLS (16) and the Burgers model (17), are often applied to biomaterials (Fig. S3 A). Strain in the SLS model reaches an equilibrium value under a creep test, whereas strain in the Burgers model continues to increase indefinitely. The creep behaviors of collagen gels, agarose gels, ionically cross-linked alginate gels, and fibrin gels matched the SLS, whereas the creep behavior of rBM matrix matched the Burgers model (Fig. S3, B–F). Thus, we employed the SLS for collagen gels, agarose gels, alginate gels, and fibrin gels and the Burgers model for rBM matrix.

We next incorporated viscoplastic elements into the established viscoelastic models to explicitly describe the plastic behavior of the materials (Fig. 6, A and B). Two different viscoplastic elements, the Bingham plastic flow model (linear) and the Norton-Hoff model (nonlinear), were used to represent the two different types of plastic flow. The Bingham plastic flow model is a viscoplastic model that triggers linear plastic flow when the applied stress exceeds a yield stress, a criteria stress over which plastic deformation is produced ((32), see Materials and Methods). In contrast, the Norton-Hoff model describes plastic flow as nonlinear with respect to stress (33) (see Materials and Methods); thus, the Bingham plastic flow model combined with the Norton-Hoff model can describe nonlinear plastic flow when an exerted stress exceeds a yield stress. As all the tested materials exhibit plasticity even at low stresses (Fig. 3, A–E), their yield stresses are considered to be negligible or 0. A model incorporating the Bingham plastic flow model combined with the Norton-Hoff model into the SLS model captures the experimentally observed stress-dependent plasticity in collagen gels (Fig. 6 C). In contrast, the addition of the Bingham plastic flow model alone captures stress-independent plasticity for the other cell-culture materials (Fig. 6 D). To establish the validity of these models, these models were then used to predict the time-dependent response of the materials (Fig. 6 E). Even though the model parameters were determined by fitting the stress-dependent response, they also accurately predict the time-dependent response of collagen gels and rBM matrix.

Figure 6.

Standard viscoelastic models combined with viscoplastic elements capture the viscoplastic behaviors of materials. The schematics describe mechanical models incorporating a viscoplastic element into (A) the SLS and (B) the Burgers model. The normalized degree of plasticity from experimental results is compared with the corresponding computational results from the mechanical model embedding nonlinear plastic flow (the Norton-Hoff plastic element) for collagen gels (C) and linear plastic flow (the Bingham plastic element) for rBM matrix, agarose gels, alginate gels, and fibrin gels (D). A comparison of the degree of plasticity from experimental and computational results at different timescales for (E) collagen gels (blue) and (F) rBM matrix (green) is shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

Reorientation of collagen fibers around cells

Next, we conducted experiments with cells cultured in collagen gels to establish the relevance of collagen-gel viscoplasticity to cellular remodeling of the collagen networks. For cell studies, the 3T3 mouse fibroblast cell line was selected, as 3T3 fibroblasts were previously found to reorganize collagen fibers in ECM (26). Cytoskeletal actin networks, which primarily determine the mechanical properties of many cell types, play a key role in generating cellular force on ECM (43). To observe the physical cell-matrix interaction along with actin dynamics, we stably transfected the 3T3 fibroblasts with RFP-Lifeact (see Materials and Methods) and performed live-cell imaging in three-dimensional collagen gels over several hours (Movie S1). The live-cell imaging showed that actin was enriched at the regions where cells were pulling and realigning collagen fibers.

We then qualitatively examined the irreversibility, or plasticity, of collagen-gel realignment by cells (37) (see Materials and Methods). To assess the permanence of fiber reorientation, cells were cultured for 1 day in collagen gels (Fig. 7 A) and then lysed to remove the cells, releasing any cellular forces on the ECM (Fig. 7 B). This process is conceptually similar to the mechanical creep and recovery tests, as stresses are applied to and then removed from the matrix. As a first pass to assessing plasticity of ECM remodeling and collagen realignment, regions of interest for the evaluation of fiber orientation were selected at regions of the collagen gel adjacent to actin-rich extensions from the cells (Fig. 7, A, inset, and C, left and center) and at regions that were far from the cells (Fig. 7 C, right). Although there were only small changes in the evenly distributed fiber orientation far from the cells (Fig. 7, C–F, right), collagen fibers near the cells were highly aligned toward the cells, demonstrating the reorientation of the collagen fiber networks by the cells. Importantly, the alignments of fibers toward the cells in these regions were sustained even after lysing the cells, indicating plastic remodeling and structural rearrangement of the collagen gels by cells (Fig. 7, C–F, left and center). This analysis provides a proof-of-principle demonstration that cells induce plastic remodeling of collagen fibers, and that plastic remodeling is enhanced near regions where actin strongly accumulates.

Figure 7.

Cells locally realign collagen fibers, and the reorientation of fibers is retained after cells are removed. Images are shown of collagen gels (A) containing cells transfected to express RFP-actin, and (B) after lysing of cells. The inset in (A) shows a fluorescent image of actin. (C) Collagen fibers at regions of interest (ROIs) near cells (left and center), where strong actin fluorescent emissions are detected, and far from cells (right). (D) Polar distribution of fiber orientation at the corresponding ROI in (C). (E) Collagen fibers after lysing cells at the same ROIs shown in (C). (F) Polar distribution of fiber orientation at the ROIs in (E). Red and blue polar distributions represent the fiber orientation at the regions near and far from cells, respectively. Scale bar, 10 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

Next, we quantitatively characterized the degree to which cellular remodeling of the collagen fiber networks was plastic. Broadly, this involved first an analysis of the local remodeling of collagen networks near live cells, which could include both plastic and elastic components. Next, to determine the extent to which this local remodeling was plastic, analysis of collagen gel remodeling was conducted after lysis of the cells, at which point elastic re-orientations of the fibers are released. The ratio of plastic remodeling, postlysis, to total remodeling, prelysis, provides a measurement of the degree to which cell remodeling of the collagen gel was plastic (see Materials and Methods). Fiber orientation with respect to each of the local points around the cell boundary was calculated as the inner product of the two unit vectors of each fiber and the line connecting the analysis point to the fiber center (Fig. 8 A; see Materials and Methods). The FOI for each analysis point was then defined as the average of this inner product as a function of distance (Fig. 8 B). The FOI for an ideal random network is ∼0.637 (see Materials and Methods). Interestingly, a graphical representation of the FOI confirmed that the fibers are highly aligned to the regions on the cell boundary with a high density of actin (Fig. 8 C, inset). Next, the degree to which cell remodeling of the collagen gels was plastic was assessed by comparing the difference between the FOI postlysis and the FOI of the random network, which corresponds to plastic remodeling of the collagen gels, to the difference between the FOI prelysis and the FOI of the random network, which corresponds to total remodeling of the collagen gels by an active cell (see Materials and Methods, Eq. 7). Analysis was restricted to regions along the cell boundary at which fibers are aligned, presumably adhesion points, defined as having an FOI of >0.647 over 30 μm (Fig. S4). This is because some minimal level of deformation and realignment of the collagen gels is needed to assess plasticity. If network deformations are purely plastic, and do not exhibit any elastic response, then the FOI of the network pre- and post-lysis would be identical, so that the plasticity would be calculated as one. In contrast, for purely elastic reorientations, the FOIpostlysis will be identical to FOIrandom network due to elastic recovery of the original orientation, and thus the plasticity becomes zero. The FOIprelysis around cells was found to be ∼0.68 on average immediately adjacent to cells, but as high as 0.95 near actin-dense regions in the cell, and it decreased over distance, eventually reaching the value of FOIrandom network (Fig. 8 B, left). FOIpostlysis around cells was found to be similar to FOIprelysis (Fig. 8 B, right). Values of plasticity were found to be 0.82 ± 0.04, indicating that remodeling of the collagen gels was largely plastic. This measure facilitates quantification of the plastic remodeling in the collagen gels due to cells.

Role of cellular forces, β1 integrin, collagen gel cross-linking, and proteolytic degradation in mediating plastic remodeling of collagen gels

One plausible explanation of the observed results is that cells apply forces to matrix through adhesions, and these physical forces result in plastic remodeling in the collagen gels over time due to unbinding of bonds between the collagen fibers, and subsequent collagen fiber realignment, flow, and rebinding. To test this interpretation, we sequentially perturbed cell-matrix adhesion, force generation, and network cross-linking and assessed plasticity. Further, the role of proteolytic degradation in plastic remodeling of the collagen gels was examined.

We first perturbed integrin binding to collagen gels to test whether plastic remodeling of collagen fibers was dependent on cell-matrix adhesions. It has been found that the force generated by actin networks is transmitted to ECM through integrins, transmembrane receptors binding to ECM proteins (14). It is thought that β1 integrin in particular plays an important role in forming matrix adhesion in collagen gels (44). Inhibition of β1 integrin significantly reduces force transmission to ECM (45). Thus, a blocking antibody of β1 integrin was applied to inhibit β1-integrin-mediated adhesion to the matrix. Inhibition of β1 integrin reduced cell spreading and diminished fiber alignment prelysis (Fig. 8 D). This result suggests the importance of β1 integrin in transmitting forces generated by cells to ECM.

Next, we investigated the influence of cellular force on the plastic remodeling of the collagen gels. Generation of force by actin networks, known to mediate cell contractility and protrusion, can be perturbed by introducing cytochalasin D (CytoD), an inhibitor of actin polymerization, into the media (46). Increasing the concentration of Cyto D, which reduces cellular force, decreases the level of plastic remodeling of the collagen gels (Figs. 8 E and S5). This indicates that the degree of plastic remodeling of collagen gels by cells is dependent on stress, consistent with the results from the creep and recovery tests on the collagen gels (Fig. 3 A).

In addition to assessing the influence of cellular force, we examined the effect of covalent cross-linking of the collagen gels on plastic remodeling. Cells were cultured in collagen gels covalently cross-linked by tTG (47). Plastic remodeling of collagen gels cross-linked by tTG was significantly reduced (Figs. 8 F and S6), a finding consistent with the results from the creep and recovery tests on the collagen gels (Fig. 5). This suggests that the plastic remodeling of collagen gels by cells involves breaking of weak bonds between fibers.

Finally, the role of MMP activity in plastic remodeling of collagen gels was established. MMP activity was inhibited during cell-culture experiments, and the impact on plastic remodeling was assessed. GM6001, a broad spectrum MMP inhibitor that is commonly employed to block the activity of MMPs (30, 36, 48, 49), was applied to inhibit MMP activity during cell-culture experiments. In the presence of MMP inhibition by GM6001, the degree of plastic remodeling of collagen gels by cells stayed at levels similar to those in control conditions (Figs. 8 G and S7). This indicates that the plastic remodeling arises from physical forces and did not rely substantially upon biochemical degradation of the matrix.

Plasticity in tissues

To complement our measurements of plasticity in cell-culture materials, we assessed the physiological relevance of plasticity by measuring plasticity in various tissues. Heart, liver, lung and brain tissues were isolated from mice and tested under compressive creep and recovery tests. The tissues were found to exhibit different levels of compliance and plasticity (Fig. S8). The degree of plasticity in the tissues varies between tissue types and the values of plasticity range from 0.1 to 0.6. Heart tissue was relatively elastic, with a degree of plasticity of 0.1–0.4, whereas brain tissue exhibited substantial plasticity, with a degree of plasticity of 0.4–0.6 (Fig. S8 B). These results reveal viscoplastic properties of tissues and establish the biological relevance of plasticity.

Discussion

In this study, viscoplasticity in cell-culture materials was characterized using creep and recovery tests, a common mechanical test in polymer science used to measure plasticity (38, 39, 50). Other mechanical tests, including stress relaxation tests, frequency-dependent rheology, creep tests, and cyclic strain tests have been widely used to examine the time-dependent, or viscoelastic, mechanical responses of biomaterials (3, 16, 23). However, these techniques do not measure plasticity. A recent study measured the plasticity of collagen gels using AFM (25). Although the AFM-based approach has the advantage of probing the mechanical properties of the material at a submicron scale (51), the creep and recovery tests conducted here facilitate a precise characterization of the stress and time dependence of plasticity in the cell-culture materials In our studies, plasticity was enhanced with increasing timescale of creep in collagen gels, rBM matrix, agarose gels, alginate gels, and fibrin gels, so that these materials can be considered as viscoplastic. Interestingly, viscoplasticity was dependent on the magnitude of stress or strain in collagen gels, but not in other materials, so that collagen gels can be considered as nonlinear viscoplastic.

A similarity among the materials that exhibit viscoplasticity is that they form gels through weak bonds. Gels of rBM, agarose and collagen form gels through noncovalent interactions such as hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions (3, 23). The fibrin gels formed here exhibit a mixture of weak bonding and covalent cross-linking by factor XIII (3, 23). Alginate gels are formed through ionic cross-linking by divalent cations such as calcium (Ca2+). These weak bonds in the materials can unbind during a creep test, allowing matrix flow and plastic deformation in networks, and then later reform or rebind. Stress dependence of plasticity in collagen gels could arise from force-dependent unbinding of weak bonds between fibers, as a greater force is more likely to unbind fibers and lead to plasticity (23). In contrast to these weak bonds, covalent cross-links have a much greater strength and were found to diminish plasticity in the gels. Addition of covalent cross-links to collagen gels reduces the degree of plasticity (Fig. 5), and covalently cross-linked alginate gels and polyacrylamide gels do not display any plasticity (Figs. 1 G, 2 F, 3, and S2). Conversely, reducing the level of covalent cross-linking by factor XIII in the fibrin gels (3) could lead to higher degrees of plasticity. Taken together, these suggest that weak bonds in the networks underlie the observed plasticity in the different materials.

We also develop appropriate models to capture the mechanical response of viscoplastic materials, as standard viscoelastic models do not always capture viscoplastic behaviors accurately. For example, in creep and recovery tests, the SLS model always fully recovers due to the elastic components, yet materials such as collagen gels, agarose gels, alginate gels and fibrin gels, whose viscoelastic response in creep or stress relaxation is captured by the SLS, do not. To better describe plastic behaviors of the cell-culture materials, we incorporated a plastic element into standard viscoelastic models. The elongation of the plastic element is irreversible when the yield stress is exceeded, corresponding to plastic deformation in the materials. We used two different plastic flow models to capture the plasticity of cell-culture materials. The linear plastic flow model describes the linearly stress-independent plasticity of rBM matrix, agarose gels, alginate gels, and fibrin gels regardless of the SLS or the Burgers model to which it is incorporated, whereas the nonlinear plastic flow model describes the nonlinear stress-dependent plasticity measured in collagen gels. These results confirm that the plastic behaviors of the materials can be captured with traditional viscoelastic models combined with an additional viscoplastic element.

Given the measured plasticity of the cell-culture materials from the bulk measurements, we examined whether cell-matrix interactions resulted in plastic remodeling of materials, using collagen gels as a model viscoplastic material. Previous studies have demonstrated fiber realignment to cells in collagen and fibrin gels (25, 26, 27, 28, 52). Here, we confirmed that the fiber realignment induced by cells was plastic through lysis experiments, consistent with previous work (26). Cellular force generation is driven by actin-network dynamics (25, 53) and coupled to matrices through integrins (14). Inhibition of actin (54, 55) dynamics or integrin binding was found to decrease plastic remodeling of collagen gels, confirming the role of cellular forces in remodeling. Further, covalent cross-linking of the collagen gels diminished the extent of plastic remodeling by cells. The dependence of the extent of plastic remodeling of collagen gels by cells on magnitude of force and covalent cross-linking mirrors findings made in bulk measurements, indicating that collagen gel viscoplasticity measured in bulk underlies plastic remodeling of collagen gels by cells. Indeed, fiber reorientation in collagen network at the microscale was observed due to bulk shear (Fig. S9). Cells are known to secrete proteolytic enzymes such as MMPs to degrade ECMs, thereby leading to irreversible changes in the structure of the matrices (28, 29, 30, 56). However, a similar level of plastic remodeling was observed in the presence of the MMP inhibitors, suggesting only a minimal role for proteolytic degradation in this study. The role of proteolytic degradation of the matrix in plastic remodeling may be more important in matrices that contain high levels of covalent cross-links. We note that it is possible that there are other factors beyond cellular forces, such as cell-mediated cross-linking of collagen or secretion of type I collagen, that might contribute to plastic remodeling of collagen gels by cells. Taken together, the rigorous quantification of fiber realignment we introduce here provides a framework to assess the degree to which remodeling of collagen gels by cells is plastic, and it reveals that cell-generated forces play a major role in plastic remodeling of matrices by cells.

Although the work here has focused on cell-culture materials, there is evidence that organs and tissues also exhibit plasticity. Various studies have reported that mechanical testing induces irreversible deformation or structural changes in tissues, including skin, bone, and connective tissues, though the tissue plasticity was not explicitly quantified (57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62). To complement these studies, we measured plasticity of heart, lung, liver, and brain tissues isolated from mice, finding a range of values of plasticity comparable to the range measured in different cell-culture materials. These results highlight the relevance of plasticity to tissues.

Conclusions

In conclusion, many of the biomaterials typically used for 3D cell culture, including collagen gels, rBM matrix, agarose gels, alginate gels, and fibrin gels, are viscoplastic. Interestingly, collagen gels were found to be nonlinearly viscoplastic. The mechanical behaviors of these materials were modeled using a combination of traditional viscoelastic models with linear or nonlinear viscoplastic elements. The relevance of these viscoplastic behaviors to cell-matrix interactions was confirmed in collagen gels by assessing plastic remodeling of the collagen gels by cells. Collagen networks were plastically deformed and realigned to cells at regions of high density of actin. Plastic remodeling of collagen gels was mediated by force generation by actin networks, β1-integrin-containing adhesions, and weak cross-linking in the collagen gels, but not by proteolytic degradation of the matrix. Overall, this work provides insight into viscoplastic behaviors of the cell-culture materials and highlights the importance of plastic remodeling in cell-matrix interactions.

Author Contributions

S.N. and O.C. designed the experiments and developed the models. S.N. conducted the experiments and ran the computational models. S.N. and J.L. performed transfection for cells. D.G.B. isolated tissues. S.N. analyzed the data. S.N. and O.C. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marc Levenston for use of the rheometer.

This work was supported by a Samsung Scholarship for S.N., and grants from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (D14AP00044) and the National Science Foundation (CMMI-1536736) to O.C.

Editor: Charles Wolgemuth.

Footnotes

Nine figures, one table, and one movie are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)30887-6.

Supporting Material

Time-lapse video of a 3T3 fibroblast expressing RFP-Lifeact (red) in a collagen gel. Collagen fibers were taken by confocal reflectance and labeled as white. Note that collagen fibers are significantly aligned toward the cell when the cells exert forces to pull the collagen fibers. RFP-actin and collagen fibers were captured at 1 frame/3min using confocal microscopy. The video plays at 10 frames/s.

References

- 1.Fratzl, P., editor. 2008. Collagen: Structure and Mechanics, Springer.

- 2.Kleinman H.K., McGarvey M.L., Martin G.R. Isolation and characterization of type IV procollagen, laminin, and heparan sulfate proteoglycan from the EHS sarcoma. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6188–6193. doi: 10.1021/bi00267a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Münster S., Jawerth L.M., Weitz D.A. Strain history dependence of the nonlinear stress response of fibrin and collagen networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:12197–12202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222787110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomasek J.J., Gabbiani G., Brown R.A. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:349–363. doi: 10.1038/nrm809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Debnath J., Brugge J.S. Modelling glandular epithelial cancers in three-dimensional cultures. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:675–688. doi: 10.1038/nrc1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreno-Arotzena O., Meier J.G., García-Aznar J.M. Characterization of fibrin and collagen gels for engineering wound healing models. Materials (Basel) 2015;8:1636–1651. doi: 10.3390/ma8041636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L., Price J.E., Fidler I.J. Correlation of growth capacity of human tumor cells in hard agarose with their in vivo proliferative capacity at specific metastatic sites. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1406–1412. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.18.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rowley J.A., Madlambayan G., Mooney D.J. Alginate hydrogels as synthetic extracellular matrix materials. Biomaterials. 1999;20:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engler A.J., Sen S., Discher D.E. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelham R.J., Jr., Wang Y.-L. Cell locomotion and focal adhesions are regulated by substrate flexibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:13661–13665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Discher D.E., Janmey P., Wang Y.L. Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science. 2005;310:1139–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.1116995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogel V., Sheetz M. Local force and geometry sensing regulate cell functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:265–275. doi: 10.1038/nrm1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaudhuri O., Koshy S.T., Mooney D.J. Extracellular matrix stiffness and composition jointly regulate the induction of malignant phenotypes in mammary epithelium. Nat. Mater. 2014;13:970–978. doi: 10.1038/nmat4009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DuFort C.C., Paszek M.J., Weaver V.M. Balancing forces: architectural control of mechanotransduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:308–319. doi: 10.1038/nrm3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaudhuri O., Gu L., Mooney D.J. Hydrogels with tunable stress relaxation regulate stem cell fate and activity. Nat. Mater. 2016;15:326–334. doi: 10.1038/nmat4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flugge W. 2nd ed. Springer; New York: 2013. Viscoelasticity. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhuri O., Gu L., Mooney D.J. Substrate stress relaxation regulates cell spreading. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6364. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKinnon D.D., Domaille D.W., Anseth K.S. Biophysically defined and cytocompatible covalently adaptable networks as viscoelastic 3D cell culture systems. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:865–872. doi: 10.1002/adma.201303680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cameron A.R., Frith J.E., Cooper-White J.J. The influence of substrate creep on mesenchymal stem cell behaviour and phenotype. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5979–5993. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao X., Huebsch N., Suo Z. Stress-relaxation behavior in gels with ionic and covalent crosslinks. J. Appl. Phys. 2010;107:063509. doi: 10.1063/1.3343265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fung Y.C. Springer; New York: 2013. Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurniawan N.A., Wong L.H., Rajagopalan R. Early stiffening and softening of collagen: interplay of deformation mechanisms in biopolymer networks. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:691–698. doi: 10.1021/bm2015812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nam S., Hu K.H., Chaudhuri O. Strain-enhanced stress relaxation impacts nonlinear elasticity in collagen gels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:5492–5497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523906113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schapery R.A. Nonlinear viscoelastic solids. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2000;37:359–366. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohammadi H., Arora P.D., McCulloch C.A. Inelastic behaviour of collagen networks in cell-matrix interactions and mechanosensation. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2015;12:20141074. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2014.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petroll W.M., Cavanagh H.D., Jester J.V. Dynamic three-dimensional visualization of collagen matrix remodeling and cytoskeletal organization in living corneal fibroblasts. Scanning. 2004;26:1–10. doi: 10.1002/sca.4950260102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Notbohm J., Lesman A., Ravichandran G. Quantifying cell-induced matrix deformation in three dimensions based on imaging matrix fibers. Integr Biol (Camb) 2015;7:1186–1195. doi: 10.1039/c5ib00013k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsen M., Artym V.V., Yamada K.M. The matrix reorganized: extracellular matrix remodeling and integrin signaling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2006;18:463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabeh F., Ota I., Weiss S.J. Tumor cell traffic through the extracellular matrix is controlled by the membrane-anchored collagenase MT1-MMP. J. Cell Biol. 2004;167:769–781. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabeh F., Shimizu-Hirota R., Weiss S.J. Protease-dependent versus -independent cancer cell invasion programs: three-dimensional amoeboid movement revisited. J. Cell Biol. 2009;185:11–19. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark E.S., Whigham A.S., Weaver A.M. Cortactin is an essential regulator of matrix metalloproteinase secretion and extracellular matrix degradation in invadopodia. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4227–4235. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nirmalkar N., Chhabra R.P., Poole R.J. Laminar forced convection heat transfer from a heated square cylinder in a Bingham plastic fluid. Int. J. Heat Mass Tran. 2013;56:625–639. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gwiazda P., Klawe F.Z., Świerczewska-Gwiazda A. Thermo-visco-elasticity for Norton-Hoff-type models. Nonlinear Anal. Real World Appl. 2015;26:199–228. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riedl J., Crevenna A.H., Wedlich-Soldner R. Lifeact: a versatile marker to visualize F-actin. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:605–607. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun X.G., Rotenberg S.A. Overexpression of protein kinase Cα in MCF-10A human breast cells engenders dramatic alterations in morphology, proliferation, and motility. Cell Growth Differ. 1999;10:343–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santiskulvong C., Rozengurt E. Galardin (GM 6001), a broad-spectrum matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor, blocks bombesin- and LPA-induced EGF receptor transactivation and DNA synthesis in rat-1 cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2003;290:437–446. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stein A.M., Vader D.A., Sander L.M. An algorithm for extracting the network geometry of three-dimensional collagen gels. J. Microsc. 2008;232:463–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2008.02141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koplin C., Rodriguez G., Jaeger R. Multiaxial strength and stress forming behavior of four light-curable dental composites. J. Res. Pract. Dent. 2014;2014:396766. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonakdar N., Gerum R., Fabry B. Mechanical plasticity of cells. Nat. Mater. 2016;15:1090–1094. doi: 10.1038/nmat4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maskarinec S.A., Franck C., Ravichandran G. Quantifying cellular traction forces in three dimensions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:22108–22113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904565106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Legant W.R., Pathak A., Chen C.S. Microfabricated tissue gauges to measure and manipulate forces from 3D microtissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:10097–10102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900174106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Legant W.R., Miller J.S., Chen C.S. Measurement of mechanical tractions exerted by cells in three-dimensional matrices. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:969–971. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoffman B.D., Grashoff C., Schwartz M.A. Dynamic molecular processes mediate cellular mechanotransduction. Nature. 2011;475:316–323. doi: 10.1038/nature10316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harunaga J.S., Yamada K.M. Cell-matrix adhesions in 3D. Matrix Biol. 2011;30:363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meshel A.S., Wei Q., Sheetz M.P. Basic mechanism of three-dimensional collagen fibre transport by fibroblasts. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:157–164. doi: 10.1038/ncb1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Casella J.F., Flanagan M.D., Lin S. Cytochalasin D inhibits actin polymerization and induces depolymerization of actin filaments formed during platelet shape change. Nature. 1981;293:302–305. doi: 10.1038/293302a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chau D.Y., Collighan R.J., Griffin M. The cellular response to transglutaminase-cross-linked collagen. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6518–6529. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bodiga V.L., Eda S.R., Bodiga S. In vitro biological evaluation of glyburide as potential inhibitor of collagenases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014;70:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolf K., Te Lindert M., Friedl P. Physical limits of cell migration: control by ECM space and nuclear deformation and tuning by proteolysis and traction force. J. Cell Biol. 2013;201:1069–1084. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201210152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jia Y., Peng K., Zhang Z. Creep and recovery of polypropylene/carbon nanotube composites. Int. J. Plast. 2011;27:1239–1251. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kloxin A.M., Kloxin C.J., Anseth K.S. Mechanical properties of cellularly responsive hydrogels and their experimental determination. Adv. Mater. 2010;22:3484–3494. doi: 10.1002/adma.200904179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim A., Lakshman N., Petroll W.M. Quantitative assessment of local collagen matrix remodeling in 3-D culture: the role of Rho kinase. Exp. Cell Res. 2006;312:3683–3692. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petroll W.M., Ma L. Direct, dynamic assessment of cell-matrix interactions inside fibrillar collagen lattices. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2003;55:254–264. doi: 10.1002/cm.10126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tan J.L., Tien J., Chen C.S. Cells lying on a bed of microneedles: an approach to isolate mechanical force. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:1484–1489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0235407100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Legant W.R., Choi C.K., Chen C.S. Multidimensional traction force microscopy reveals out-of-plane rotational moments about focal adhesions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:881–886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207997110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Even-Ram S., Yamada K.M. Cell migration in 3D matrix. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:524–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang W., Sherman V.R., Meyers M.A. On the tear resistance of skin. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6649. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quinn K.P., Winkelstein B.A. Preconditioning is correlated with altered collagen fiber alignment in ligament. J. Biomech. Eng. 2011;133:064506. doi: 10.1115/1.4004205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akhtar N., Zaman S.U., Ebrahimzadeh M.A. Calendula extract: effects on mechanical parameters of human skin. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2011;68:693–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dobrev H.P. A study of human skin mechanical properties by means of Cutometer. Folia Med. (Plovdiv) 2002;44:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burstein A.H., Zika J.M., Klein L. Contribution of collagen and mineral to the elastic-plastic properties of bone. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1975;57:956–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ettema G.J.C., Goh J.T.W., Forwood M.R. A new method to measure elastic properties of plastic-viscoelastic connective tissue. Med. Eng. Phys. 1998;20:308–314. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(98)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Time-lapse video of a 3T3 fibroblast expressing RFP-Lifeact (red) in a collagen gel. Collagen fibers were taken by confocal reflectance and labeled as white. Note that collagen fibers are significantly aligned toward the cell when the cells exert forces to pull the collagen fibers. RFP-actin and collagen fibers were captured at 1 frame/3min using confocal microscopy. The video plays at 10 frames/s.