Abstract

Background

The Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) has been recommended as the core patient‐reported outcome measure for trials of eczema treatments. Using data from the Choice of Moisturiser for Eczema Treatment randomized feasibility study, we assess the responsiveness to change and determine the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of the POEM in young children with eczema.

Methods

Responsiveness to change by repeated administrations of the POEM was investigated in relation to change recalled using the Parent Global Assessment (PGA) measure. Five methods of determining the MCID of the POEM were employed; three anchor‐based methods using PGA as the anchor: the within‐patient score change, between‐patient score change and sensitivity and specificity method, and two distribution‐based methods: effect size estimate and the one half standard deviation of the baseline distribution of POEM scores.

Results

Successive POEM scores were found to be responsive to change in eczema severity. The MCID of the POEM change score, in relation to a slight improvement in eczema severity as recalled by parents on the PGA, estimated by the within‐patient score change (4.27), the between‐patient score change (2.89) and the sensitivity and specificity method (3.00) was similar to the one half standard deviation of the POEM baseline scores (2.94) and the effect size estimate (2.50).

Conclusions

The Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure as applied to young children is responsive to change, and the MCID is around 3. This study will encourage the use of POEM and aid in determining sample size for future randomized controlled trials of treatments for eczema in young children.

Keywords: atopic eczema, minimal clinically important difference, paediatrics, Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure, responsiveness

Background

Eczema is the most common inflammatory skin disorder in childhood 1, 2. However, there is a lack of randomized controlled trial (RCT) evidence for many of the commonly used treatments, such as emollients. Crucial to the design of RCTs is the choice of outcome measures which should cover the spectrum of effects important to clinicians and patients and should be a valid measure and responsive to change in eczema severity. Furthermore, it is difficult to interpret the body of evidence from research that has been carried out because of the variety of different outcome measures that have been used. The Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) initiative 3, 4 has recommended that Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) 5, 6 and, more recently, the Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) 7 are included as core clinical and patient‐reported outcome measures, respectively, in clinical eczema trials.

However, there are limited studies determining the minimal clinically important difference (MCID, the smallest change in an outcome score that is important to clinicians and or caregivers) of these measures, especially in populations of children with mild‐to‐moderate eczema, hindering the planning and design of trials. The number of participants in trials (sample size) is determined on the basis of probability (power) to detect a true clinically important difference in the chosen primary outcome. In securing funding and to support the design and delivery of trials of eczema treatments, it is important to be able to bring together a coherent summary of the existing evidence and to justify the choice of outcome measures and present a convincing research plan.

To address these issues using data from the Choice of Moisturiser for Eczema Treatment (COMET) randomized feasibility study 8, we assess the responsiveness to change and determine the MCID of POEM according to parents with the use of the Parent Global Assessment (PGA).

Participants, data and outcome measures

COMET 8 was a randomized feasibility study designed to determine the feasibility of recruiting young children (from 1 month to <5 years of age) with eczema from primary care within the UK. Details of the study are published elsewhere (Ridd et al., under submission BMJ Open), but in summary, 197 participating children were randomized to one of four commonly prescribed emollients and followed up for 3 months. Parent‐completed diaries of outcome measures were collected which included the weekly POEM (Box 1) and monthly PGA measures.

Box 1. Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM).

Over the last week …

… on how many days has your child's skin been itchy because of their eczema?

… on how many nights has your child's sleep been disturbed because of their eczema?

… on how many days has your child's skin been bleeding because of their eczema?

… on how many days has your child's skin been weeping or oozing clear fluid because of their eczema?

… on how many days has your child's skin been cracked because of their eczema?

… on how many days has your child's skin been flaking off because of their eczema?

… on how many days has your child's skin felt dry or rough because of their eczema?

Reponses:

No days (score of 0)

1–2 days (score of 1)

3–4 days (score of 2)

5–6 days (score of 3)

Every day (score of 4)

The POEM measure 7 comprises seven questions each asking the parent about their experience of their child's eczema in the last week. Each question is rated on a five‐point scale from either no days (scoring 0) to every day (scoring 4). The seven question's scores are added together to create a total POEM score with a minimum score of 0 and a maximum of 28, where a lower score is a better outcome. If one question is unanswered, it is scored as 0 and a total score is still calculated; however, if more than one question is missing, then a total score is not calculated and it is assumed to be missing.

The Parent Global Assessment asks ‘How is your child's eczema compared with one month ago?’ with a response of ‘Much better’ (score of 2), ‘Better’ (score of 1), ‘No difference’ (score of 0), ‘Worse’ (score of ‐1) or ‘Much worse’ (score of ‐2). Therefore, the PGA is a measure of change in eczema severity where a higher score represents an improvement.

Analysis

The POEM outcome measure was compared with the PGA because it is a simple yet meaningful external anchor. The responsiveness of the POEM to change was compared with the PGA at each month by presenting global responsiveness curves of mean change scores over time 9. As the POEM was asked weekly, the month's score was taken as the final week's score, that is month 1 is week 4, month 2 is week 8 and month 3 is week 12. Change over a month on the POEM measure was defined as the previous month's score minus the current month's score (e.g. week 0‐week 4), which was compared with the corresponding monthly PGA score.

The POEM outcome measure defines a lower score as a better outcome; therefore, a positive change score (as defined here) is an improvement over time. The PGA score represents a change in eczema severity over one month, and a higher score represents a better outcome.

We employed five methods aimed at determining the MCID for the POEM measure. The three anchor‐based approaches used were the within‐patient score change method, between‐patient score change method and the sensitivity and specificity method. All anchor‐based methods require an ‘anchor’ measure and use subgroups defined by the scores of this anchor measure to determine the MICD. In our study, the ‘anchor’ measure is the PGA.

The within‐patient score change method used the mean change in POEM scores of those classified as being in minimal‐change subgroup of the PGA. We defined the minimal‐change subgroup as those parents that report their child (the participant) being ‘better’ than the previous month 10. It has been suggested that the minimal‐change subgroup should also include those that report their child becoming ‘worse’ on the PGA compared with the previous month 11. However, to combine the POEM scores of these two subgroups, an assumption must be made that the distribution of POEM change scores is identical except for the sign. This assumption can be tested using a Mann–Whitney U‐test [Wilcoxen rank‐sum 12] for two independent samples on the absolute values (disregarding the sign) of the POEM change scores. Revicki et al. 11 suggest that definition of the within‐patient score change MCID should be those within the smallest improvement group, those who respond ‘better’ to the PGA, as long as those participants have larger changes in outcome score than the stable ‘no difference’ group.

The between‐patient score change method used the difference in the mean POEM change scores of two adjacent subgroups of the PGA 13. The two subgroups selected were those parents that responded that their child was ‘better’, or there was ‘no difference’ in their eczema compared with one month ago.

The sensitivity‐ and specificity‐based method selects the MCID which most optimally discriminates between groups of participants classified using their response to the PGA. The area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to identify the cut‐off score of the POEM which represent the greatest correct classification between those with a PGA response of ‘better’, and ‘no difference’. The MCID is defined as the POEM score which maximizes Youden's J statistic 14, defined as sensitivity‐(1‐specificity).

Two distribution‐based approaches were also used to determine the MCID of the POEM measure. The effect size (ES) estimate is a standardized measure of change defined as the change in the outcome measure scores between baseline and follow‐up, divided by the SD of the baseline scores. It represents the number of standard deviations by which the scores have changed from baseline to follow‐up; with an ES of 0.2 being considered small, 0.5 moderate and 0.8 large 13, 15, 16. Half of the standard deviation of the baseline POEM scores was also calculated as this is a metric routinely used when determining sample size for clinical trials 17.

All of these five methods to determine the MCID were carried out using data from the baseline assessment and the first follow‐up; one month after the baseline assessment. This was chosen as it was hypothesized that the most visible change in eczema severity would have been seen one month after treatment was started. The results are reported for all participants and not separated by treatment allocation, as any treatment difference in outcome would not confound the analysis presented here.

Results

The study participants were of mean age 21.7 months at baseline (SD 12.8, n = 197). The majority were White (85%, n = 182) and male (57%, n = 197). According to the POEM thresholds of eczema severity defined by Charman et al. 18, the distribution of participants baseline eczema severity showed that 14% had clear or almost clear, 33% mild, 42% moderate and 11% severe eczema (n = 196). About 3% (5/196) of the participants scored the lowest, and 1% (1/196) scored the highest POEM score possible at baseline.

As can be seen from Table 1, the decrease in average POEM scores suggests an improvement over time. The numbers analysed decrease because of missing data (raw POEM scores <1% to 28%, first follow‐up PGA 23%, change in POEM over first follow‐up month and PGA at first follow‐up month 25%). However, this attrition is unlikely to have altered the relationship between the POEM and PGA measures and is therefore not likely to have confounded the anchor‐based estimates of the MCID. However, this attrition may lead to some underestimation of the distribution‐based MCID estimates if, for example those for whom treatment is least effective do not respond. No methods were used to impute the missing data. There is little evidence of skewness as the means are similar to the median values. There is evidence of a moderate‐to‐strong correlation (Pearson's correlation coefficients 0.48 to 0.74) between the parent‐reported POEM measure at different time‐points. This shows that children in the study cohort with the most severe symptoms at baseline are still relatively worse at each follow‐up visit.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) and Parent Global Assessment (PGA) outcome measure at each time‐point

| POEM | PGA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (25th, 75th percentile) | N responding (% missing) | Modal response | Number giving modal response/number responding | |

| Baseline | 8.80 (5.87) | 8.00 (4.00, 12.00) | 196 (<1% missing) | NA | |

| Month 1 (week 4) | 5.73 (5.38) | 4.00 (2.00, 8.00) | 153 (22% missing) | No difference | 53/152 |

| Month 2 (week 8) | 5.32 (5.81) | 3.00 (1.00, 8.00) | 144 (27% missing) | Better | 48/139 |

| Month 3 (week 12) | 4.31 (4.67) | 3.00 (1.00, 7.00) | 142 (28% missing) | Better | 50/142 |

Responsiveness

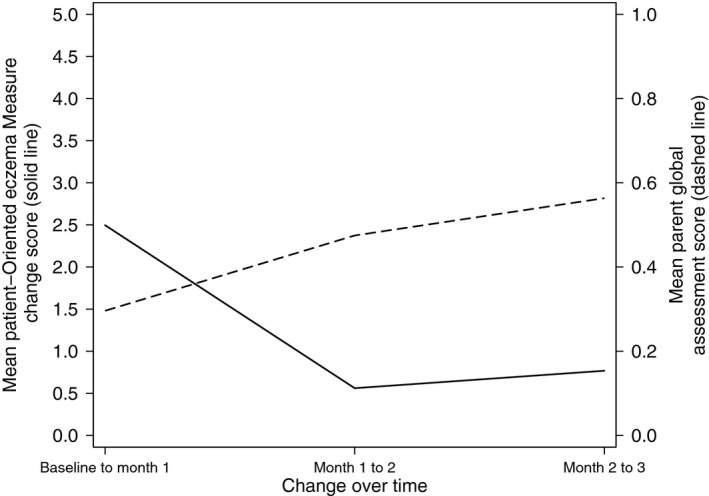

Figure 1 illustrates the responsiveness of the POEM measure compared with the PGA measure. It shows the mean change score of the POEM measure against the mean score of the PGA at each time‐point. As the PGA question asks how the parents view their child's eczema compared with one month ago, the mean scores presented here can be interpreted as a change in eczema severity.

Figure 1.

Responsiveness of Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure outcome measure over time compared with Parent Global Assessment (PGA). Higher positive score indicates greater improvement on both measures. PGA is an ordered categorical variable, analysed here as continuous.

It can be seen that the POEM appears to respond to changes in underlying eczema severity as measured by PGA as the anchor. Both measures show improvement at each time‐point compared with previous; however, the timing of the biggest improvement differs between the two measures. The largest change in POEM score is seen between baseline and month 1 with a mean change of 2.50. There is a marked increase in mean PGA scores between month 1 and month 2 (representing an improvement in overall eczema severity) mirroring the more modest improvement in mean POEM change scores during this period.

The Pearson's correlation coefficient between the POEM change score and the PGA at month one is 0.48 which shows there is modest agreement between the two measures of change. The children who show the greatest improvement on POEM also tend to show the greatest improvement on the PGA score.

Anchor‐based approaches of determining the MCID

Within‐patient score change

The minimal‐change subgroup of the PGA for this method was those who report their child (the participant) becoming ‘better’ compared with the previous month. The results of the Mann–Whitney U‐test of equality 12 of distributions of those in the ‘better’ and ‘worse’ subgroups of the PGA shows that there is strong evidence that these subgroup samples are from populations with different distributions (P < 0.001), and therefore, we cannot confidently combine these two subgroups into the same minimal‐change subgroup.

The mean POEM change score for those participants in the ‘no difference’ PGA subgroup is 1.38 (Table 2), which is smaller than the change score in the smallest improvement, ‘better’ subgroup of the PGA, and therefore, the MCID is 4.27 (95% CI 3.32–5.22) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) raw and change scores by Parent Global Assessment (PGA) response at month 1

| POEM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGA | Mean (SD)a | Mean (SD)a | Mean change score (SD)b | |

| Response at month 1 | Baseline | Month 1 | Baseline ‐Month 1 | Number analysed |

| Much worse | 19.00 (12.73) | 21.00 (8.49) | ‐2.00 (4.24) | 2 |

| Worse | 7.50 (5.58) | 7.97 (5.46) | ‐0.47 (5.34) | 30 |

| No difference | 7.90 (5.72) | 6.52 (5.44) | 1.38 (4.42) | 52 |

| Better | 8.31 (4.70) | 4.04 (3.97) | 4.27 (3.27) | 48 |

| Much better | 9.56 (5.05) | 2.81 (3.58) | 6.75 (4.55) | 16 |

A lower POEM score is more positive.

A positive change score shows improvement over time.

Between‐patient score change

The between‐patient score change MCID is defined as the difference in outcome scores of those within two adjacent groups of the PGA. We calculated this as the difference in mean POEM change scores of those in the ‘better’ subgroup and those in the ‘no difference’ subgroup. The MCID using this definition is 2.89 (95% CI 1.33–4.44, n = 100). Table 2 shows the POEM scores by PGA response at month 1, and it can be seen that the POEM scores are decreasing as the PGA response improves.

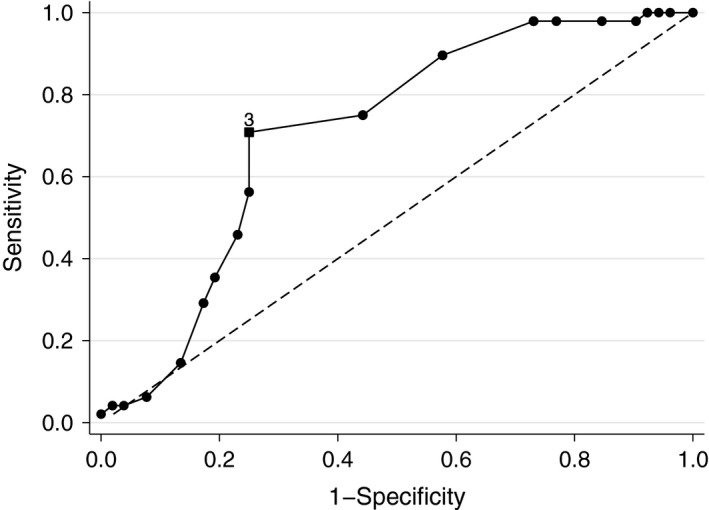

Sensitivity‐ and specificity‐based approach

Comparing those participants in the ‘better’ and ‘no difference’ subgroups of the PGA, the AUC of the ROC curve is acceptable at 0.71 (95% CI 0.61–0.81, n = 100) 13. The MCID by this method, which can be defined as the POEM change score which maximizes Youden's J statistic [sensitivity‐(1‐specificity)] 14, is 3 with 0.71 sensitivity and 0.25 false‐positive rate (1‐specificity) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of within‐patient Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure change scores in classifying according to Parent Global Assessment subgroups of ‘better’ vs ‘no difference’.

Distribution‐based approach of determining the MCID

Effect size and half standard deviation of baseline scores

The ES is calculated by dividing the change in outcome measure scores from baseline to the first follow‐up month by the SD of the baseline scores; the result is 0.43 (95% CI 0.29–0.56). The change score equivalent to this ES is the mean change score of all the participants; the result is 2.50 (n = 153). Half the standard deviation of the baseline POEM scores is 2.94 (half of baseline SD of 5.87) (Table 1) with 95% CI 2.67–3.26.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This is the first published study of the responsiveness and MCID of POEM for young children within primary care. We found that POEM was responsive to change in eczema severity over the three time‐points, shown by comparison with the PGA measure (Fig. 1) with a trend of a decrease in overall symptom severity over time. The three different anchor‐based approaches (using the PGA as the anchor) used to calculate the MCID of POEM all gave different values of the MCID of a slight improvement in the POEM change score of either 4.27 (within patient method), 2.89 (between patient) or 3 (AUC generated from the ROC curve). Whilst the distribution‐based methods use data from the whole cohort rather than only those experiencing modest change, all five methods broadly concur with an MCID of 3.

In conclusion, The Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) as applied to young children is responsive to change and the MCID is around 3. This improvement of 3 points in the POEM outcome measure could be achieved by a change on one question (symptom of eczema) equal to a reduction in number of days the symptom occurred from every day (score of 4) to 1–2 days (score of 1) or from 5–6 days (score of 3) to no days (score of 0).

Strengths and weaknesses

This study used the responsiveness, interpretability and generalizability checklists within the Consensus‐based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) guidelines 19.

The anchor‐based methods for calculation of the MCID have greater face validity as they define the MCID as a contrast between those perceived on a global scale as not having changed and those having improved a modest amount. However, the five contrasting methods each gave estimates of the MCID of around 3 for the POEM measure in young children.

The children that participated in this study were recruited from a range of different GP surgeries amongst areas varying in levels of deprivation (Index of Multiple Deprivation ‘deciles’ 2 to 10), and therefore, we believe that these participants were representative of young children with eczema within the UK.

Important criticisms of the methods used are that the distribution‐based approaches are calculated using data from all participants, and therefore, this result is not easily comparable with the estimates of the MCID from the anchor‐based methods which are based on subgroup(s) of participants stratified by their response to the PGA, and these results do not take into account the improvement or decline in eczema severity as seen by parents.

The PGA scale has not been validated or tested for reliability; parents may struggle to recall their child's previous health state at a specified time‐point to determine whether their state has changed. Therefore, global measures of change are usually more strongly correlated with the current state compared with the previous state 20. This hypothesis is supported within these data by the larger absolute Pearson's correlation coefficient of 0.4 seen between the raw POEM score and the PGA at month 1, than that observed between the raw POEM score at baseline and the PGA at month 1 of 0.03.

These results demonstrate that repeated administrations of a parent‐completed assessment of a child's eczema symptoms (POEM) are sensitive to that parent's recall of change in symptoms over the same period (PGA). Indeed, for the reasons mentioned above, repeated administrations of POEM may be more accurate. Furthermore, we have used parent recall of change to determine the MCID for the POEM.

Our estimate of the MCID is similar to that found by Schram et al. 9. of 3.4 using results from 80 participants in two trials (MAcAD and PROVE); however, our results are based on a larger sample of participants (n = 148). They also found the POEM to be responsive to change over time compared with their constructed PGA which was not phrased as a change over time, as in our study, and was scored on a six‐point Likert scale of disease severity. However, these were trials of adult populations with severe eczema, and therefore, the results may not be comparable with our study in young children from the primary care population where the majority of the participants were classified as suffering from moderate eczema (42% of 196, baseline POEM classification).

Clinical and research implications

The MCID of the POEM score has not previously been established in young children with eczema; however, it has been used as an outcome measure and for sample size calculations of randomized controlled trials without knowing the magnitude of the effect that it can show 21, 22, 23. This study will therefore help to more accurately determine sample size calculations for future RCTs looking to use POEM as an outcome measure and will aid interpretation of differences in POEM scores.

Author contributions

DMG carried out the analysis, wrote the first draft of the manuscript and subsequently edited all versions incorporating revisions and comments from all co‐authors. CM oversaw the analysis, revised and edited the manuscript. MR was the CI of the COMET feasibility study and contributed to discussions on the presentation of the findings and all revisions of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interests

All authors have completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This article uses data from independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (Research for Patient Benefit Programme, PB‐PG‐0712‐28056). The views expressed in the publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health. This study was designed and delivered in collaboration with Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration (BRTC), a UKCRC Registered Clinical Trials Unit in receipt of National Institute for Health Research CTU support funding. We would like to thank all the participants and their parents of the COMET trial and the COMET trial team for contributing, collecting and entering the data.

Gaunt DM, Metcalfe C, Ridd M. The Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure in young children: responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy 2016; 71: 1620–1625

Edited by: Stephan Weidinger

References

- 1. Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2016;387:1109–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, Feldman SR, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Part 1: diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70:338–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schmitt J, Spuls P, Thomas K, Simpson E, Furue M, Deckert S. The Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) statement to assess clinical signs of atopic eczema in trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;134:800–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schmitt J, Spuls P, Boers M, Thomas K, Chalmers J, Roekevisch E et al. Towards global consensus on outcome measures for atopic eczema research: results of the HOME II meeting. Allergy 2012;67:1111–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tofte S, Graber M, Cherill R, Omoto M, Thurston M, Hanifin J. Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI): a new tool to evaluate atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1998;11:S197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, Cherill R, Tofte SJ, Graeber M et al. The eczema area and severity index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol 2001;10:11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The patient‐oriented eczema measure: development and initial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from the patients’ perspective. Arch Dermatol 2004;140:1513–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ridd M, Redmond N, Hollinghurst S, Ball N, Shaw L, Guy R et al. Choice of Moisturiser for Eczema Treatment (COMET): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015;16:304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schram ME, Spuls PI, Leeflang MMG, Lindeboom R, Bos JD, Schmitt J. EASI (objective) SCORAD and POEM for atopic eczema: responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy 2012;67:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Walters S, Brazier J. What is the relationship between the minimally important difference and health state utility values? The case of the SF‐6D. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Revicki D, Hays RD, Cella D, Sloan J. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient‐reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilcoxon F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biometr Bull 1945;1:80–83. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Copay AG, Subach BR, Glassman SD, Polly DW Jr, Schuler TC. Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: a review of concepts and methods. Spine J 2007;7:541–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950;3:32–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liang M, Fossel A, Larson M. Comparisons of five health status instruments for orthopaedic evaluation. Med Care 1990;28:632–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health‐related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care 2003;41:582–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Charman CR, Venn AJ, Ravenscroft JC, Williams HC. Translating Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) scores into clinical practice by suggesting severity strata derived using anchor‐based methods. Br J Dermatol 2013;169:1326–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res 2010;19:539–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Norman G, Stratford P, Regehr G. Methodological problems in the retrospective computation of responsiveness to change: the lesson of Cronbach. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:869–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Santer M, Rumsby K, Ridd MJ, Francis NA, Stuart B, Chorozoglou M et al. Bath additives for the treatment of childhood eczema (BATHE): protocol for multicentre parallel group randomised trial. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Santer M, Muller I, Yardley L, Burgess H, Selinger H, Stuart BL et al. Supporting self‐care for families of children with eczema with a web‐based intervention plus health care professional support: pilot randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thomas KS, Dean T, O'Leary C, Sach TH, Koller K, Frost A et al. A randomised controlled trial of ion‐exchange water softeners for the treatment of eczema in children. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1000395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]