Abstract

Objectives

To present the baseline patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) in the Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) randomized trial comparing active monitoring, radical prostatectomy and external‐beam conformal radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer and to compare results with other populations.

Materials and Methods

A total of 1643 randomized men, aged 50–69 years and diagnosed with clinically localized disease identified by prostate‐specific antigen (PSA) testing, in nine UK cities in the period 1999–2009 were included. Validated PROMs for disease‐specific (urinary, bowel and sexual function) and condition‐specific impact on quality of life (Expanded Prostate Index Composite [EPIC], 2005 onwards; International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire‐Urinary Incontinence [ICIQ‐UI], 2001 onwards; the International Continence Society short‐form male survey [ICSmaleSF]; anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS]), generic mental and physical health (12‐item short‐form health survey [SF‐12]; EuroQol quality‐of‐life survey, the EQ‐5D‐3L) were assessed at prostate biopsy clinics before randomization. Descriptive statistics are presented by treatment allocation and by men's age at biopsy and PSA testing time points for selected measures.

Results

A total of 1438 participants completed biopsy questionnaires (88%) and 77–88% of these were analysed for individual PROMs. Fewer than 1% of participants were using pads daily (5/754). Storage lower urinary tract symptoms were frequent (e.g. nocturia 22%, 312/1423). Bowel symptoms were rare, except for loose stools (16%, 118/754). One third of participants reported erectile dysfunction (241/735) and for 16% (118/731) this was a moderate or large problem. Depression was infrequent (80/1399, 6%) but 20% of participants (278/1403) reported anxiety. Sexual function and bother were markedly worse in older men (65–70 years), whilst urinary bother and physical health were somewhat worse than in younger men (49–54 years, all P < 0.001). Bowel health, urinary function and depression were unaltered by age, whilst mental health and anxiety were better in older men (P < 0.001). Only minor differences existed in mental or physical health, anxiety and depression between PSA testing and biopsy assessments.

Conclusion

The ProtecT trial baseline PROMs response rates were high. Symptom frequencies and generic quality of life were similar to those observed in populations screened for prostate cancer and control subjects without cancer.

Keywords: prostate cancer, treatment, functional status, quality of life, protect trial, ISRCTN 20141297

Abbreviations

- PROM

patient‐reported outcome measure

- ProtecT trial

Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment trial

- NIHR

National Institute for Health Research

- QoL

quality of life

- EPIC

Expanded Prostate Index Composite

- ICIQ‐UI

International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire‐Urinary Incontinence

- MID

minimal clinically important difference

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- ERSPC

European Randomised Screening for Prostate Cancer

- PCOS

Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study

- CEASAR

Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation

- UCLA‐PCI

University of California Los Angeles Prostate Cancer Index

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most commonly detected male malignancy in many countries and accounted for 10 837 deaths in the UK in 2012 (Cancer Research UK: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/prostate-cancer). Prostate cancer screening with PSA has been shown to identify predominantly clinically localized disease in two randomized trials of screening 1, 2. The main treatments for localized prostate cancer are active surveillance, brachytherapy, external‐beam or intensity‐modulated radiotherapy and open or robot‐assisted radical prostatectomy 3. The optimum treatment that balances the risks of the intervention and disease control remains uncertain, although two randomized trials of surgery and watchful waiting (supportive care with treatment of symptoms as required) showed a disease‐specific survival benefit for radical intervention in the Scandinavian SPCG‐4 trial 4, but only for some men in the US PIVOT trial 5.

Clinicians and patients selecting prostate cancer treatments need robust information to enable them to balance symptom and broader impact on quality of life (QoL) against mortality and disease progression outcomes. Validated patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) 6 are the recommended tools to assess the specific impacts of prostate cancer treatment on incontinence, urinary irritation and obstruction, bowel‐related symptoms, sexual function and hormone therapy 7, 8; however, there has been limited use of validated PROMs in localized prostate cancer trials, although recent radiotherapy trials have incorporated PROMs 9. One of the comparative trials of surgery and watchful waiting for localized disease measured symptoms with a Scandinavian questionnaire 10, whilst the other trial used single items for urinary symptoms, bowel and sexual function 5.

The UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) trial compares the effectiveness of active monitoring (a surveillance strategy), radical prostatectomy and external‐beam conformal radiotherapy with neoadjuvant androgen suppression for localized prostate cancer. The primary outcome of prostate cancer‐specific and intervention‐related mortality will be reported at a median 10 years’ follow‐up in 2016. The present paper reports the baseline PROMs results to assess their comparability with other studies and to investigate the generalizability of the randomized population, which will assist interpretation of the trial outcome results.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

The ProtecT trial design, baseline socio‐demographic and clinical results have been published elsewhere (Lane et al.; protocol (http://www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hta/962099)]. A feasibility pilot trial (recruitment: 1999–2001) preceded the main trial (recruitment: 2001–2009) 11. In brief, the trial aimed to establish the effectiveness of radical prostatectomy, external‐beam conformal radiotherapy or active monitoring for men with clinically localized prostate cancer. Men aged 50–69 years were invited for PSA testing in primary care, and those with a PSA level ≥3.0 to 19.95 ng/mL proceeded to further diagnostic tests, including prostate biopsies. Men with clinically localized prostate cancer were eligible for randomization if there were no major contra‐indications for the radical treatments (exclusions detailed previously) 11. In total, 2417 participants were identified with localized disease (of 82 849 men PSA tested) and, of these, 1643 participants were randomized to three treatments. The primary outcome of definite or probable prostate cancer mortality (including intervention related‐mortality) at a median of 10 years’ follow‐up and the secondary clinical, health economic and patient‐reported outcomes will be published in 2016 (trial registration: ISRCTN 20141297, http://www.isrctn.com, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02044172).

Ethics

Approval was obtained from the UK National Health Service Health Research Authority Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (01/04/025).

Patient‐Reported Outcomes Measures

Validated PROMs and their specific items (Table 1) were selected using literature reviews and qualitative interviews with participants 12 to capture the major impacts related to prostate cancer treatments: urinary symptoms of incontinence and erectile function after surgery; bowel function after radiotherapy and anxiety or depression from living with untreated cancer during active monitoring 7. We also aimed to assess the effects of ageing on urinary symptoms over time and wider health issues using generic QoL measures. The trial focused on treatments for localized disease so the Expanded Prostate Index Composite (EPIC) hormonal domain was not used, but this did not impact on the use of other domains, which were scored separately 13. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C‐30 (EORTC‐QLQC‐30) 14, which has symptom and functional scales, generic QoL and single items, was used at 5 and 10 years’ follow‐up (added in 2007).

Table 1.

ProtecT trial patient‐reported outcome measures and completion rates at first prostate biopsy by randomized participants

| Outcome | PROM focus (timeframe)* | PROM scales/items presented (range/categories): [domain MID]† | Completion by randomised participants (n = 1643) (n completed/ n given the PROM)‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary | ICIQ‐UI: incontinence (4 weeks) |

Incontinence score (0–21): [1.2] Number of continent men (score of 0, 0–100%) QoL impact (0–10, moderate: 2–6, large: 7–10) |

76% 82% (1244/1508) |

| EPIC: PCa treatment (4 weeks) |

Summary, function and bother scores (0–100): [4.6, 4.2, 5.9] Incontinence and irritative/obstruction scales (0‐100): [5.7, 4.6] Pad use (≥one/day) |

45% 88% (745/849) |

|

| ICSmaleSF: LUTS (4 weeks) |

Incontinence score (0–24): [1.0] Voiding score (0–20): [1.5] Daytime frequency (≤2 h/void), nocturia (>1/night), QoL impact (little, somewhat/a lot) |

86% (1413/1643) | |

| Bowel | EPIC: PCa treatment (4 weeks) |

Summary, function and bother scores (0–100): [4.2, 4.4, 5.0] Bloody stools (ever), loose stools (≥50% of time), faecal incontinence (≥1/week), QoL impact (very small/small, moderate/big) |

46% 88% (748/849) |

| Sexual | EPIC: PCa treatment (4 weeks) |

Summary, function and bother scores (0–100): [11.6, 11.5, 14.8] Erectile function (not firm enough for intercourse), QoL impact (very small/small, moderate/big) |

44% 85% (719/849) |

| Psychological | HADS: anxiety and depression (1 week) |

Anxiety and depression scores (0–21): [1.8, 1.3] Potential clinical cases of anxiety or depression (≥8) |

85% (1399/1643) |

| SF‐12: overall mental health (4 weeks) | Mental component sub‐score (0–100): [3.8] | 77% (1260/1643) | |

| Physical | SF‐12: overall physical health (4 weeks) | Physical component sub‐score (0–100): [4.0] | 77% (1260/1643) |

| Generic health | EQ‐5D‐3L: health utility (today) | Health utility score (‐0.594‐1.0 scored as perfect health): [0.09] | 86% (1413/1643) |

| Cancer‐related QoL | EORTC‐QLQC30 4 (1 week) | Global health, five functional and three symptom scales, five single items, completed after randomization | – |

EPIC, Expanded Prostate cancer Index Composite; EORTC‐QLQC30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C‐30; EQ‐5D‐3L, EuroQol quality‐of‐life survey; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ICIQ‐UI, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire‐Urinary Incontinence; ICSmaleSF, International Continence Society short‐form male survey; MID, minimal clinically important difference; PROM, patient‐reported outcome measure; QoL, quality of life; SF‐12, 12‐item short‐form health survey. *Questionnaire‐specific recall period; †MID taken as 0.5 sd of baseline values; ‡excludes men with insufficient items to calculate scales.

Data Collection and Analysis

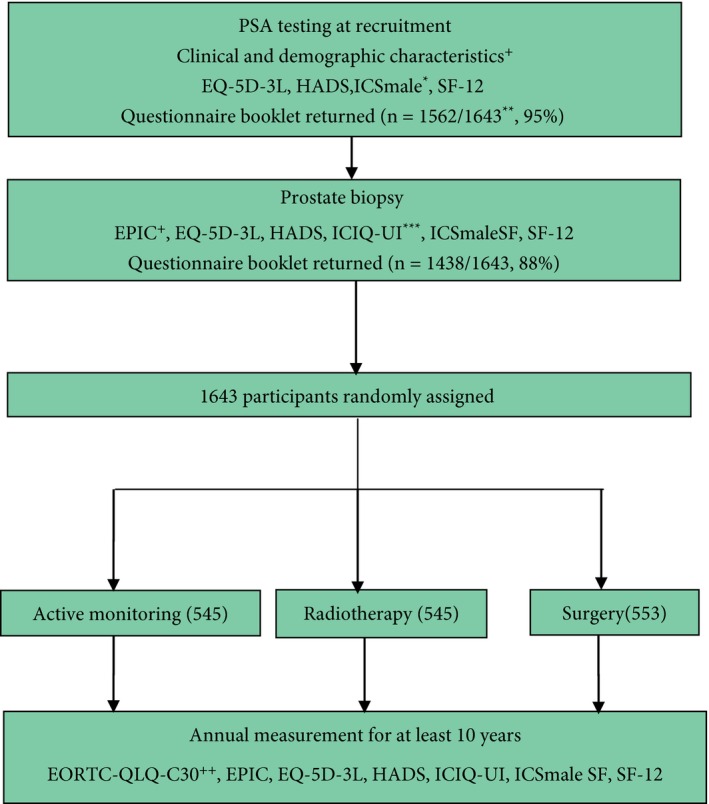

Participants completed paper questionnaires at initial PSA testing (trial recruitment) and at first prostate biopsy clinics, without reminders to non‐responders (Fig. 1). The more comprehensive set of assessments completed at first biopsy were taken as the baseline for subsequent trial outcome analyses. Randomized participants completed postal questionnaires at 6 months and then annually for at least 10 years (ongoing in 2016). Randomized non‐responders received reminder letters and questionnaires, followed by telephone calls from trial nurses and then a shortened version of the questionnaire with fewer measures. Some men were not given the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire‐Urinary Incontinence (ICIQ‐UI; n = 135) or EPIC (n = 794) measures as they were introduced in the trial during 2001 and 2005, respectively. Data are presented for the return of the PROMs questionnaire booklet and the numbers which could be analysed for each PROM.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of PROMs completed by ProtecT randomised participants. +Collected by research nurses, *selected ICSmale‐SF items, **SF‐12 and ICSmale as EQ5D‐3L and HADS omitted for first 118 participants, +EPIC introduced in 2005, ***ICIQ‐UI introduced in 2001, ++EORTC QLQ‐C30 [19] introduced in 2007.

The PROMs were analysed as specified by the developers with no additional imputation for missing data. To aid interpretation of the results, the minimal clinically important difference (MID) was calculated as half a standard deviation of baseline values (a commonly used distribution‐based method), but unspecified by the PROMs developers because MIDs are a more recently utilized concept (Table 1). Categorical symptom variables were dichotomized to ‘never or low/rarely’ vs ‘ever’ and International Continence Society short‐form male survey (ICSmaleSF) items were dichotomized as previously in the ProtecT trial pilot phase 20. The number of men without incontinence was defined as those with an ICIQ‐UI score of 0. Symptom‐related QoL items were categorized as none, small and a moderate/severe problem attributable to expected low prevalence of symptoms before treatment. Age was categorized into five‐year groups (49–54 years to 65–69 years, with one 49‐year‐old who was eligible at recruitment). Self‐reported ethnicity was categorized using UK Office of National Statistics census groupings (http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160105160709/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/measuring-equality/equality/ethnic-nat-identity-religion/ethnic-group/index.html). Socio‐economic position was based on men's current or last paid occupation at recruitment, and was grouped into professional or managerial (e.g. doctor), intermediate (e.g. secretary) and routine or semi‐routine (e.g. postman) using the UK Office of National Statistics categories 21.

Numbers and percentages are presented for categorical data, means and sd values for continuous data, and medians and interquartile ranges for skewed data. Those PROMs with a skewed distribution of results (EPIC, ICIQ‐UI) as a result of few participants reporting symptoms are presented as means to aid comparison with other studies. Comparisons across age and occupational social class used Cuzick's test for trend whilst Wilcoxon's matched‐pairs signed‐rank tests (ordinal/continuous data) and McNemar's test (nominal data) were used for comparisons of recruitment and biopsy data. Variation in selected PROMs completed at first biopsy (EPIC, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS] and a 12‐item short‐form health survey [SF‐12]) was explored according to men's age at recruitment and occupational social class and whether any differences exceeded the MID. PROMs data collected at PSA testing and biopsy time points were compared, and a sensitivity analysis subsequently assessed the impact of adding PSA testing data if the data from the biopsy time point were missing. All analyses were performed in stata (version 13).

Results

Study and Participant Characteristics and PROMs Completion

The median age of randomized participants was 61 years, the majority were married or co‐habiting (84%, 1375) and of white ethnicity (99%, 1606; full baseline demographic and clinical details published elsewhere) 11. Approximately two fifths of participants reported a professional or managerial occupation (42%, 684/1643), 16% (259) an intermediate occupation and 42% (678) a routine or semi‐routine occupation. Most randomized participants had low‐risk disease features at diagnosis, as the median PSA at PSA testing was 4.6 ng/mL and around three quarters had a Gleason score of 6 (77%, 1266) and clinical stage of T1c (76%, 1249).

The majority of participants returned a questionnaire booklet at PSA testing (recruitment, 95%) and first biopsy clinics (88%, Fig. 1). Data that could be analysed for measures completed at first biopsy ranged from 77% for the SF‐12 to 88% for EPIC bowel and urinary function (Table 1). As EPIC was introduced during the trial, 52% of randomized participants were asked to complete all PROMs at baseline (849/1643). Response rates for all PROMs were similar by randomized treatment allocation (Tables 2, 3, 4).

Table 2.

Urinary function by randomized allocation in ProtecT trial participants

| PROMs*, summary scores and specific symptoms or QoL impact | Active monitoring N = 545 | Radiotherapy N = 545 | Surgery N = 553 | Total N = 1643 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICIQ‐UI minimum analysed/asked, n/N (%) | 422/500 (84) | 408/498 (82) | 414/510 (81) | 1244/1508 (82) |

| Incontinence mean score (sd) | 1.3 (2.5) | 1.2 (2.0) | 1.3 (2.4) | 1.3 (2.3) |

| No incontinence, n (%) | 305 (72) | 280 (69) | 288 (70) | 873 (70) |

| Moderate QoL impact, n/N (%) | 28/428 (7) | 24/413 (6) | 29/418 (7) | 81/1259 (6) |

| Large QoL impact, n/N (%) | 3/428 (1) | 0/413 (0) | 1/418 (<1) | 4/1259 (<1) |

| EPIC minimum analysed/asked, n/N (%) | 244/280 (87) | 246/283 (87) | 255/286 (89) | 745/849 (88) |

| Urinary summary (sd) | 93.0 (9.6) | 93.2 (8.3) | 91.9 (9.4) | 92.7 (9.1) |

| Function score (sd) | 95.6 (8.0) | 94.7 (8.3) | 94.8 (8.9) | 95.1 (8.4) |

| Bother score (sd) | 91.2 (12.3) | 92.1 (10.3) | 89.9 (12.2) | 91.0 (11.7) |

| Incontinence score (sd) | 93.5 (11.3) | 92.8 (11.0) | 92.8 (11.6) | 93.0 (11.3) |

| Irritative/obstructive score (sd) | 93.2 (9.5) | 93.8 (7.9) | 92.0 (9.9) | 93.0 (9.2) |

| Pad use | 1/250 (<1%) | 0/248 (0%) | 4/256 (2%) | 5/754 (1%) |

| ICSmaleSF minimum analysed, n/N (%) | 471/545 (86) | 462/545 (85) | 480/553 (87) | 1413/1643 (86) |

| Incontinence score (sd) | 1.9 (2.1) | 1.8 (1.8) | 1.8 (1.8) | 1.8 (1.9) |

| Voiding score (sd) | 3.4 (2.9) | 3.1 (2.9) | 3.3 (3.1) | 3.3 (3.0) |

| Daytime frequency, n/N (%) | 147/470 (31) | 150/457 (33) | 163/483 (34) | 460/1410 (33) |

| Nocturia, n/N (%) | 111/475 (23) | 89/463 (19) | 110/485 (23) | 312/1423 (22) |

| Little urinary QoL impact, n/N (%) | 109/475 (23) | 99/466 (21) | 115/486 (24) | 323/1427 (23) |

| Somewhat/a lot QoL impact, n/N (%) | 20/475 (4) | 14/466 (3) | 10/486 (2) | 44/1427 (3) |

ICIQ‐UI, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire‐Urinary Incontinence; ICSmaleSF, International Continence Society short‐form male survey. *Details of PROMs and their administration in Table 1 and Fig. 1, the minimal clinically important difference (MID) was not exceeded for any domain between randomized groups.

Table 3.

Bowel and sexual function by randomized allocation in ProtecT trial participants

| EPIC* summary scores (SD) and specific symptoms (%) | Active monitoring (n = 545) | Radiotherapy (n = 545) | Surgery (n = 553) | Total (n = 1643) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowel function | ||||

| Minimum analysed/asked, n/N (%) | 247/280 (88) | 247/283 (87) | 254/286 (89) | 748/849 (88) |

| Summary score | 92.8 (9.1) | 94.8 (6.9) | 93.1 (8.9) | 93.6 (8.4) |

| Function score | 91.6 (9.0) | 92.9 (8.0) | 91.4 (9.3) | 92.0 (8.8) |

| Bother score | 94.0 (11.8) | 96.8 (7.1) | 94.7 (10.3) | 95.1 (10.0) |

| Bloody stools, n/N (%) | 18/247 (7) | 18/250 (7) | 16/255 (6) | 52/752 (7) |

| Loose stools, n/N (%) | 43/249 (17) | 39/250 (16) | 36/255 (14) | 118/754 (16) |

| Stool leakage, n/N (%) | 10/249 (4) | 3/250 (1) | 10/255 (4) | 23/754 (3) |

| Overall bowel problems: small, n/N (%) | 32/249 (13) | 18/247 (7) | 35/255 (14) | 85/751 (11) |

| Moderate/big bowel problems, n/N (%) | 11/249 (4) | 4/247 (2) | 5/255 (2) | 20/751 (3) |

| Sexual function | ||||

| Minimum analysed/asked, n/N (%) | 236/280 (84) | 241/283 (85) | 240/286 (84) | 719/849 (85) |

| Summary score | 60.3 (23.5) | 63.6 (23.1) | 61.4 (22.7) | 61.8 (23.1) |

| Function score | 53.5 (22.8) | 55.7 (23.0) | 54.4 (22.9) | 54.5 (22.9) |

| Bother score | 76.0 (30.5) | 80.5 (29.2) | 77.6 (28.9) | 78.0 (29.5) |

| Erectile function, n/N (%) | 79/243 (33) | 78/247 (32) | 84/245 (34) | 241/735 (33) |

| Erectile problems: small | 70/239 (29) | 55/245 (22) | 63/247 (26) | 188/731 (26) |

| Erectile problems: moderate/big | 39/239 (16) | 39/245 (16) | 40/247 (16) | 118/731 (16) |

| Overall sexuality problem: small | 55/239 (23) | 58/244 (24) | 69/245 (28) | 182/728 (25) |

| Moderate/big sexuality problems | 44/239 (18) | 31/244 (13) | 39/245 (16) | 114/728 (16) |

Table 4.

Health‐related quality of life and psychological status in men randomized in the ProtecT trial

| Summary EPIC* scores (sd) or case (%) | Active monitoring N = 545 | Radiotherapy N = 545 | Surgery N = 553 | Total N = 1643 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF‐12 minimum analysed, n (%) | 418 (77) | 410 (75) | 432 (78) | 1260 (77) |

| Mental health score | 53. 4 (8.2) | 54.5 (6.3) | 53.9 (7.9) | 53.9 (7.5) |

| Physical health score | 50.4 (8.7) | 51.7 (7.0) | 51.4 (7.9) | 51.2 (7.9) |

| HADS minimum analysed, n (%) | 469 (86) | 454 (83) | 472 (85) | 1399 (85) |

| Anxiety score | 5.1 (3.6) | 4.5 (3.2) | 5.0 (3.6) | 4.9 (3.5) |

| Depression score | 2.7 (2.7) | 2.3 (2.4) | 2.4 (2.5) | 2.5 (2.5) |

| Anxiety possible case, n/N (%) | 107/472 (23) | 74/454 (16) | 97/477 (20) | 278/1403 (20) |

| Depression possible case, n/N (%) | 37/469 (8) | 17/458 (4) | 26/472 (6) | 80/1399 (6) |

| EQ‐5D‐3L analysed, n (%) | 474 (87) | 458 (84) | 481 (87) | 1413 (86) |

| Health utility | 0.87 (0.19) | 0.90 (0.16) | 0.88 (0.17) | 0.89 (0.17) |

EPIC, Expanded Prostate cancer Index Composite; MID, EQ‐5D‐3L, EuroQol quality‐of‐life survey; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SF‐12, 12‐item short‐form health survey. *Details of PROMs and their administration in Table 1 and Fig. 1; the MID was not exceeded for any domain between randomized groups.

Urinary, Bowel and Sexual Dysfunction and their QoL Impact

Levels of incontinence were low, indicating few problems, and at baseline <1% of men reported incontinence as a large problem (4/1259 [Table 2]) at diagnosis. Fewer than 1% of men reported using at least one pad per day (5/754). Seventy percent of the participants reported being incontinence‐free (873/1244). Urinary function was good (EPIC score 95.1) and bother related to urinary symptoms was low (EPIC score 91.0), with few irritative or obstructive symptoms (EPIC score 93.0), as measured by EPIC. Nocturia was reported by around one fifth of men (312/1423; ICSmaleSF) and around one third also reported a regular daytime frequency (460/1410), although only 3% of men (44/1427) reported these LUTS as being a moderate or severe problem (ICSmaleSF).

Bowel symptom EPIC scores were good (i.e. few problems) and only 3% of men (20/751) reported a moderate or large problem attributable to bowel symptoms (Table 3). The frequency of faecal incontinence or bloody stools was also low, although 16% of participants reported having loose stools at least half of the time (118/754).

Around one third of men (241/735) reported erectile dysfunction and for 16% of participants this was a moderate or large problem (118/731) with the EPIC measure. Sexual function and bother scores were much lower than for urinary and bowel symptoms as assessed by EPIC (Tables 2 and 3).

Generic Health Status, Anxiety and Depression

Generic physical and mental health sub‐scores were similar with UK normative data (SF‐12 sub‐scores of 50 [Table 4]) 18. The EuroQoL health utility scale, the EQ‐5D‐3L, also indicated good overall health (score 0.89). Mean anxiety and depression scores were low, although one fifth of men (278/1403) had possible clinical levels of anxiety and ~6% of men had depression (80/1399 [Table 4]).

Symptoms and Quality of Life by Age and Occupational Social Class

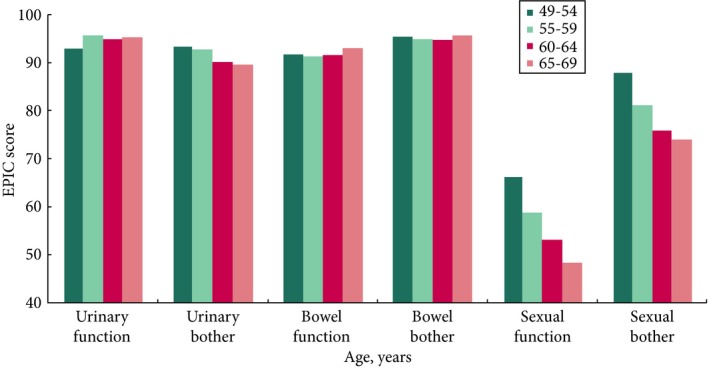

Urinary EPIC summary and bother scores were generally worse in older men than younger men, unlike urinary function, and all bowel scores (where there was no difference with age), but differences in urinary scores did not exceed the MID (Table 5 and Fig. 2). The EPIC sexual summary, function and bother scores were better in the youngest (49–54 years) men compared with the oldest age group (65–69 years), and these differences in summary and functional scores exceeded the MID (Table 5). Anxiety was less frequent in older men, unlike depression which was similar across all age groups. In older men, physical health was worse than in younger men, whilst mental health was better (Table 5) although none of these differences exceeded the MID for HADS and SF‐12. There were no strong associations of socio‐economic status with quality of life, although there was some evidence of higher levels of depression and reduced bowel function with lower status, but neither exceeded the MID (Table S1). There was no evidence that physical health differed by socio‐economic status.

Table 5.

Symptoms and quality of life by age group in men randomized in the ProtecT trial

| Age group | 49–54 years | 55–59 years | 60–64 years | 65–70 years | P * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms (MID)† | |||||

| Minimum analysed/asked, n/N (%) | 76/87 (87) | 200/225 (89) | 220/270 (81) | 223/267 (84) | |

| Urinary summary (4.6) | 93.1 (9.9) | 94.0 (7.2) | 92.2 (9.5) | 92.0 (9.9) | 0.022 |

| Urinary function (4.2) | 92.9 (12.8) | 95.7 (7.0) | 94.9 (8.0) | 95.3 (8.1) | 0.627 |

| Urinary bother (5.9) | 93.3 (10.3) | 92.7 (9.2) | 90.2 (12.4) | 89.6 (13.1) | <0.001 |

| Bowel summary (4.2) | 93.7 (10.3) | 93.1 (8.6) | 93.1 (8.2) | 94.4 (7.6) | 0.357 |

| Bowel function (4.4) | 91.7 (11.1) | 91.3 (9.0) | 91.6 (8.7) | 93.0 (7.9) | 0.170 |

| Bowel bother (5.0) | 95.4 (11.6) | 94.9 (9.8) | 94.7 (10.0) | 95.7 (9.7) | 0.755 |

| Sexual summary score (11.6) | 72.9 (20.6) | 65.8 (21.0) | 60.0 (23.2) | 56.2 (23.8) | <0.001 |

| Sexual function score (11.5) score | 66.1 (21.2) | 58.8 (20.3) | 53.0 (22.4) | 48.3 (24.0) | <0.001 |

| Sexual bother score (14.8) | 87.9 (24.1) | 81.1 (28.0) | 75.9 (30.8) | 74.0 (30.4) | <0.001 |

| Mental/physical health†(MID), n/N (%) | 142/189 (75) | 346/418 (83) | 403/532 (76) | 369/504 (73) | |

| Anxiety score (1.8)‡ | 5.5 (3.5) | 5.2 (3.5) | 4.8 (3.6) | 4.5 (3.3) | <0.001 |

| Depression score (1.3)‡ | 2.5 (2.8) | 2.4 (2.7) | 2.5 (2.5) | 2.4 (2.3) | 0.123 |

| Mental health score (3.8)§ | 51.9 (9.2) | 53.3 (7.3) | 53.9 (7.7) | 55.3 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| Physical health score (4.0)§ | 52.9 (7.6) | 51.6 (7.8) | 50.9 (8.0) | 50.3 (7.9) | <0.001 |

HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MID, minimal clinically important difference; PROM, patient‐reported outcome measure; SF‐12, 12‐item short‐form health survey. Data are EPIC summary scores (sd), unless otherwise indicated. *Cuzick's test; MID 0.5 sd of baseline values with domains in bold where exceeded between youngest and oldest age groups. †Details of PROMs and their administration in Table 1 and Fig. 1; ‡HADS; §SF‐12;

Figure 2.

Urinary, bowel and sexual function and bother by age in randomized participants in the ProtecT trial. Details of Expanded Prostate Index Composite (EPIC) administration in Table 1 and Fig. 1, y‐axis 0–40 not shown.

Generic Physical and Mental Health at PSA Testing and Biopsy

There were no differences in overall mental health (SF‐12), and minor differences which did not exceed the MID in physical health (SF‐12 < 2 scale points), nor in anxiety (<0.2 points) and depression (0.5 points) at PSA testing and first biopsy clinics (data not shown). The addition of PSA testing PROM data if biopsy PROM data were missing (e.g. an extra 188 participants for the anxiety score) did not alter the biopsy results (data not shown), so this approach was used in the trial outcome analyses (R. Pickard, M. Fabricus & E. McColl, unpublished data).

Discussion

There was good completion of a comprehensive range of validated PROMs at diagnostic biopsy before randomization to treatments for localized prostate cancer in the ProtecT trial. Urinary and bowel symptoms were generally infrequent (apart from storage LUTS), whilst sexual dysfunction was reported by around one third of men. Urinary and sexual function were generally worse in older men (65–69 years) than younger men (49–54 years) with clinically important reductions (MID) in sexual function, unlike bowel function where there were no age‐related effects. Anxiety and depression were reported in around one fifth and one twentieth of participants, respectively. Overall physical and mental health scores were similar to national normative data. There were no large differences in mental or physical health, anxiety or depression between PSA testing and biopsy assessments. These data, therefore, confirm that the men randomized in the ProtecT study were generally healthy and mostly asymptomatic.

Interpretation of the ProtecT trial clinical results will be enhanced by the use of validated PROMs with pretreatment measurements (recommended by the CONSORT‐PRO guidelines) 6 and high response rates. The ProtecT trial results are based on men identified by community‐based PSA testing and are hence analogous to screen‐detected patients with largely low‐risk disease, which reflects contemporary practice in many countries, unlike the earlier SPCG‐4 trial 4. The comprehensive range of PROMs encompasses the domains identified to assess treatments for prostate cancer by the National Cancer Institute prostate cancer working group 7, the International Consortium for Health Outcome Measurements for prostate cancer 8 and the ongoing core outcome set for localized prostate cancer trials which used mixed methods to reach consensus (MacLennan SJ et al. Core outcome set for trials of interventions for localized prostate cancer, unpublished data). The EPIC‐26 PROM (a shorter version of EPIC) is now recommended for assessing prostate cancer treatments 8 and EPIC was added to the trial in 2005, so the majority of participants will have outcome assessments using this measure. Overall QoL and psychological PROMs also assessed the broader impacts of prostate cancer treatment, unlike in many previous studies 22, 23, 24.

There are some potential limitations to these baseline results in that the characteristics of non‐responders to questionnaires were not compared with those of responders, although major differences are unlikely given the high response rates. Less severe psychological impacts may have been overlooked as the HADS was developed to detect clinical depression and anxiety 17. Psychological distress was reported by around one fifth of ProtecT trial participants (33/171) completing the Impact of Events Scale at PSA testing and biopsies in a sub‐study 25, which was similar to the frequency of anxiety reported with HADS in the present study by randomized participants. Baseline PROMs assessments occurred during the diagnostic process, which may have influenced participants’ perceptions of symptoms but were needed before randomization and there were also only minor differences between PSA and biopsy assessments. Furthermore, we present MIDs to aid interpretation and comparison with other findings but these PROMs were developed before the MID concept was widespread and this had not been validated nor was it in the prespecified trial analysis plan.

The applicability of the present results to men of non‐white ethnicity is unclear, as ProtecT trial participants were mostly of white ethnicity. The percentage of white participants in the trial was broadly similar to the older male population at seven of the cities in the ProtecT trial (UK census data), whilst the percentage of black participants was lower than in the population of one city and Asian men in two cities. Participants in screening trials are often healthier than the general population and, in the European Randomised Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) trial screened arm, cardiovascular mortality was lower than in the unscreened arm 26. The ProtecT trial baseline overall physical and mental health and HADS scores in randomized participants were similar to UK population data 18, 27, as was broadly the dietary energy intakes of ProtecT participants with prostate cancer 28. The socio‐economic distribution of randomized participants in the ProtecT trial is similar to national data (e.g. 39% of men aged 55–64 years with a professional occupation in census data compared with 42% in ProtecT trial participants) 21.

The ProtecT trial baseline PROM results could be compared either with men undergoing prostate cancer screening prior to prostate cancer treatment or men with benign urological conditions or community‐based populations. ERSPC participants without prostate cancer reported good urinary and bowel function, low bother (EPIC score) and reduced sexual function, which worsened in older men (Dutch questionnaire) 29 in a similar manner to randomized participants in the ProtecT trial. There were few changes in quality of life and anxiety during ERSPC screening 30, 31 and their SF‐36 scores were consistent with the ProtecT trial SF‐12 scores at PSA testing and biopsy (scoring equivalency exists between questionnaires 32). Men with high levels of anxiety during ERSPC screening were predicted to have high anxiety at recruitment 33, which was also observed in the wider ProtecT trial cohort 25. Non‐cancer controls in the American Prostate Lung and Colorectal Cancer screening trial showed similar patterns of bowel, sexual and urinary symptoms (EPIC score) to those of men in ProtecT trial at baseline 34.

None of the major localized prostate cancer trials 4, 5, 35 comparing treatments include baseline assessments made before treatment, unlike several prostate cancer cohorts. Rates of erectile function, pad use (1%) and problematic urinary symptoms (2%) in US patients before treatment, measured with EPIC‐26 36, were similar to baseline ProtecT trial findings. Dutch patients subsequently undergoing surgery or radiotherapy also had similar levels of pad use, a slightly lower frequency of loose stools (10%) and greater erectile dysfunction (~50%) 37 than results presented here. American prostate cancer cohorts that recruited either in 1994 to 1995 (Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study [PCOS]) or 2011 to 2012 (Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation [CEASAR]), with baseline assessments made by recalling symptoms before diagnosis with the University of California Los Angeles Prostate Cancer Index (UCLA‐PCI, a precursor to EPIC) and EPIC‐26, respectively, were compared for patterns over time 38. Incontinence was relatively frequent but was higher in the newer cohort (CEASAR: 27%, PCOS 19%), whilst pad use was higher in both cohorts than reported here (CEASAR: 7%, PCOS 3%). Erectile dysfunction was very prevalent in the recent CESAR cohort (45%, PCOS: 24%) and the ProtecT trial baseline results at around one third of men was broadly similar to both cohorts. Bowel function was good in the CESAR cohort 39 but was not compared with PCOS because the UCLA‐PCI did not include all the bowel questions included in the EPIC score.

An Australian cohort of men without prostate cancer (matched to men with the disease) 40 showed similar levels of incontinence (1% pad use), a slightly higher percentage of major bowel problems (6%) and similar erectile dysfunction (22%), assessed using the UCLA‐PCI, to those seen in the participants of the ProtecT trial men at baseline. The prevalence of LUTS increased with age and was up to 30% in men aged >80 years, based on UK general practice data 41. Some symptom PROMs used in the ProtecT trial were validated with clinical or community populations, e.g. ICIQ‐UI where the community sample incontinence score (1.6) was similar to the ProtecT trial results in the present study, and was lower than for urology clinic attendees (2.4) 15. Men listed for surgery for LUTS had a mean incontinence score of 4.0 and a voiding score of 8.9 (ICSmaleSF) 16, which indicated worse symptoms than for participants in the ProtecT trial before treatment. The UCLA‐PCI results for US men without cancer were very similar to ProtecT trial baseline results 42, except that bowel function and bother were worse in older men, possibly because the mean age of older men completing UCLA‐PCI was 79 years, which exceeded the upper age limit for ProtecT trial men (69 years). The EPIC sexual function scores of older men in the ProtecT trial were below a clinical threshold for potency (EPIC sexual domain score of <60) 43.

In conclusion, there were generally low levels of urological and bowel symptoms but more erectile dysfunction in participants before randomization and treatment for localized prostate cancer in the ProtecT trial. Symptom frequencies and trends with age were similar to those found in other cohorts. These results help characterize the trial population and will facilitate the robust evaluation of treatment impacts when the ProtecT trial outcomes are published in 2016.

Conflict of Interest

Chris Metcalfe reports grants from UK NIHR Health Technology Assessment and Health Services Research Programme and Clinical Trials Unit Support Funding, outside the submitted work. Jane Blazeby, Jenny L. Donovan, Tim J. Peters and Athene Lane reports grants from National Institute for Health Research and Clinical Trials Unit Support Funding during the conduct of the study. Jenny L. Donovan, Freddie C. Hamdy, David E. Neal and Tim J. Peters are NIHR senior investigators. Some of Jenny L. Donovan's time is supported by the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust. The remaining authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Table S1 Symptoms and quality of life by occupational social class in men randomised in the ProtecT trial.

Acknowledgements

The ProtecT trial is funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme (projects 96/20/06, 96/20/99, http://www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hta/962099) with the University of Oxford as sponsor. Department of Health disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health.

Appendix 1.

The authors acknowledge the tremendous contribution of all study participants and the study group: Nurses: leads: Sue Bonnington, Lynne Bradshaw, Debbie Cooper, Emma Elliott, Pippa Herbert, Peter Holding, Joanne Howson, Mandy Jones, Teresa Lennon, Norma Lyons, Hilary Moody, Claire Plumb, Tricia O'Sullivan, Liz Salter, Sarah Tidball, Pauline Thompson; others: Tonia Adam, Sarah Askew, Sharon Atkinson, Tim Baynes, Jan Blaikie, Carole Brain, Viv Breen, Sarah Brunt, Sean Bryne, Jo Bythem, Jenny Clarke, Jenny Cloete, Susan Dark, Gill Davis, Rachael De La Rue, Jane Denizot, Elspeth Dewhurst, Anna Dimes, Nicola Dixon, Penny Ebbs, Ingrid Emmerson, Jill Ferguson, Ali Gadd, Lisa Geoghegan, Alison Grant, Collette Grant, Catherine Gray, Rosemary Godfrey, Louise Goodwin, Susie Hall, Liz Hart, Andrew Harvey, Chloe Hoult, Sarah Hawkins, Sharon Holling, Alastair Innes, Sue Kilner, Fiona Marshall, Louise Mellen, Andrea Moore, Sally Napier, Julie Needham, Kevin Pearse, Anna Pisa, Mark Rees, Elliw Richards, Lindsay Robson, Janet Roxburgh, Nikki Samuel, Irene Sharkey, Michael Slater, Donna Smith, Pippa Taggart, Helen Taylor, Vicky Taylor, Ayesha Thomas, Briony Tomkies, Nicola Trewick, Claire Ward, Christy Walker, Ayesha Williams, Colin Woodhouse, Elizabeth Wyber and others. Urological Surgeons: Jonathan Aning, Prasad Bollina, Jim Catto, Andrew Doble, Alan Doherty, Garett Durkan, David Gillatt, Owen Hughes, Roger Kocklebergh, Anthony Kouparis, Howard Kynaston, Hing Leung, Param Mariappan, Alan McNeill, Edgar Paez, Alan Paul, Raj Persad, Philip Powell, Stephen Prescott, Derek Rosario, Edward Rowe, Hartwig Schwaibold, David Tulloch, Mike Wallace. Oncologists: Amit Bahl, Richard Benson, Mark Beresford, Catherine Ferguson, John Graham, Chris Herbert, Grahame Howard, Nick James, Alastair Law, Carmel Loughrey, Malcolm Mason, Duncan McClaren, Helen Patterson, Ian Pedley, Angus Robinson, Simon Russell, John Staffurth, Paul Symonds, Narottam Thanvi, Subramaniam Vasanthan, Paula Wilson. Radiotherapy: Helen Appleby, Dominic Ash, Dean Aston, Steven Bolton, Graham Chalmers, John Conway, Nick Early, Tony Geater, Lynda Goddall, Claire Heymann, Deborah Hicks, Liza Jones, Susan Lamb, Geoff Lambert, Gill Lawrence, Geraint Lewis, John Lilley, Aileen MacLeod, Pauline Massey, Alison McQueen, Rollo Moore, Lynda Penketh, Janet Potterton, Neil Roberts, Helen Showler, Stephen Slade, Alasdair Steele, James Swinscoe, Marie Tiffany, John Townley, Jo Treeby, Joyce Wilkinson, Lorraine Williams, Lucy Wills, Owain Woodley, Sue Yarrow Histopathologists: Selina Bhattarai, Neeta Deshmukh, John Dormer, Malee Fernando, John Goepel, David Griffiths, Ken Grigor, Nick Mayer, Jon Oxley, Mary Robinson, Murali Varma, Anne Warren. Data Management, Research and Statistics: Lucy Brindle, Michael Davis, Dan Dedman, Liz Down, Hanan Khazragui, Chris Metcalfe, Sian Noble, Tim Peters, Hilary Taylor, Marta Tazewell, Emma Turner, Julia Wade, Eleanor Walsh, Grace Young; Administration: Susan Baker, Elizabeth Bellis‐Sheldon, Chantal Bougard, Joanne Bowtell, Catherine Brewer, Chris Burton, Jennie Charlton, Nicholas Christoforou, Rebecca Clark, Susan Coull, Christine Croker, Rosemary Currer, Claire Daisey, Gill Delaney, Rose Donohue, Jane Drew, Rebecca Farmer, Susan Fry, Jean Haddow, Alex Hale, Susan Halpin, Belle Harris, Barbara Hattrick, Sharon Holmes, Helen Hunt, Vicky Jackson, Donna Johnson, Mandy Le Butt, Jo Leworthy, Tanya Liddiatt, Alex Martin, Jainee Mauree, Susan Moore, Gill Moulam, Jackie Mutch, Alena Nash, Kathleen Parker, Christopher Pawsey, Michelle Purdie, Teresa Robson, Lynne Smith, Jo Snoeck, Carole Stenton, Tom Steuart‐Feilding, Chris Sully, Caroline Sutton, Carol Torrington, Zoe Wilkins, Sharon Williams, Andrea Wilson and others. Data Monitoring Committee: Chairs: Adrian Grant and Ian Roberts; Deborah Ashby, Richard Cowan, Peter Fayers, Killian Mellon, James N'Dow, Tim O'Brien, Michael Sokhal. Trial Steering Committee: Chair: Michael Baum; Jan Adolfson, Peter Albertsen, David Dearnaley, Fritz Schroeder, Tracy Roberts, Anthony Zietman.

A.L. and C.M. contributed equally to the paper.

ProtecT Study group members are given in Appendix 1.

References

- 1. Schroder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ et al. Screening and prostate‐cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 1320–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL III et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate‐cancer screening trial. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 1310–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chou R, Croswell JM, Dana T et al. Screening for prostate cancer: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155: 762–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holmberg L, Bill‐Axelson A, Helgesen F et al. A randomized trial comparing radical prostatectomy with watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 781–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilt TJ, Brawer MK, Jones KM et al. Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 203–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG et al. Reporting of patient‐reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA 2013; 309: 814–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen RC, Chang P, Vetter RJ et al. Recommended patient‐reported core set of symptoms to measure in prostate cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014; 106: 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martin NE, Massey L, Stowell C et al. Defining a standard set of patient‐centered outcomes for men with localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2015; 67: 460–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wilkins A, Mossop H, Syndikus I et al. Hypofractionated radiotherapy versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with intermediate‐risk localised prostate cancer: 2‐year patient‐reported outcomes of the randomised, non‐inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1605–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johansson E, Steineck G, Holmberg L et al. Long‐term quality‐of‐life outcomes after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group‐4 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12: 891–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lane JA, Donovan JL, Davis M et al. Active monitoring, radical prostatectomy, or radiotherapy for localised prostate cancer: study design and diagnostic and baseline results of the ProtecT randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 1109–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donovan J, Hamdy F, Neal D et al. Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) feasibility study. 2003. Report No.14: 7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13. Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health‐related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 2000; 56: 899–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ‐C30: a quality‐of‐life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85: 365–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, Shaw C, Gotoh M, Abrams P. ICIQ: a brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2004; 23: 322–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Donovan JL, Peters TJ, Abrams P, Brookes ST, de aRJ, Schäfer W. Scoring the short form ICSmaleSF Questionnaire. J Urol 2000;164:1948–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67: 361–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK et al. Cross‐validation of item selection and scoring for the SF‐12 health survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51: 1171–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. EuroQol Group . EuroQol ‐ a new facility for the measurement of health‐related quality of life. Health Policy 1990; 16: 199–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brindle LA, Oliver SE, Dedman D et al. Measuring the psychosocial impact of population‐based prostate‐specific antigen testing for prostate cancer in the UK. BJU Int 2006; 98: 777–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hall C. A picture of the United Kingdom using the National Statistics Socio‐economic Classification. Popul Trends 2006;125:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bellardita L, Valdagni R, van den Berg R et al. How does active surveillance for prostate cancer affect quality of life? A systematic review Eur Urol 2015; 67: 637–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Whiting P, Moore T, Jameson C et al. Symptomatic and quality of life outcomes following treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer: a systematic review. BJU Int 2016; 118: 193–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baker H, Wellman S, Lavender V. Functional quality‐of‐life outcomes reported by men treated for localized prostate cancer: a systematic literature review. Oncol Nurs Forum 2016; 43: 199–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Macefield RC, Metcalfe C, Lane JA et al. Impact of prostate cancer testing: an evaluation of the emotional consequences of a negative biopsy result. Br J Cancer 2010; 102: 1335–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Otto SJ, Schröder FH, de Koning HJ. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in prostate cancer patients in the Rotterdam randomized screening trial. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 4184–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Breeman S, Cotton S, Fielding S, Jones G. Normative date for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Qual Life Res 2015; 24: 391–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Avery KN, Donovan JL, Gilbert R et al. Men with prostate cancer make positive dietary changes following diagnosis and treatment. Cancer Causes Control 2013; 24: 1119–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Korfage IJ, Roobol M, de Koning HJ, Kirkels WJ, Schröder FH, Essink‐Bot ML. Does “normal” aging imply urinary, bowel, and erectile dysfunction? A general population survey Urology 2008; 72: 3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Essink‐Bot ML, de Koning HJ, Nijs HG, Kirkels WJ, van der Maas PJ, Schröder FH. Short‐term effects of population‐based screening for prostate cancer on health‐related quality of life. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998; 90: 925–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vasarainen H, Malmi H, Määttänen L et al. Effects of prostate cancer screening on health‐related quality of life: results of the Finnish arm of the European randomized screening trial (ERSPC). Acta Oncol 2013; 52: 1615–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jenkinson C, Layte R, Jenkinson D et al. A shorter form health survey: can the SF‐12 replicate results from the SF‐36 in longitudinal studies? J Public Health Med 1997; 19: 176–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Carlsson S, Aus G, Wessman C, Hugosson J. Anxiety associated with prostate cancer screening with special reference to men with a positive screening test (elevated PSA) ‐ Results from a prospective, population‐based, randomised study. Eur J Cancer 2007; 43: 2109–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Taylor KL, Luta G, Miller AB et al. Long‐term disease‐specific functioning among prostate cancer survivors and noncancer controls in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 2768–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crook JM, Gomez‐Iturriaga A, Wallace K et al. Comparison of health‐related quality of life 5 years after SPIRIT: Surgical Prostatectomy Versus Interstitial Radiation Intervention Trial. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 362–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate‐cancer survivors. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1250–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van Tol‐Geerdink JJ, Leer JW, van Oort IM et al. Quality of life after prostate cancer treatments in patients comparable at baseline. Br J Cancer 2013; 108: 1784–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Resnick MJ, Barocas DA, Morgans AK et al. The evolution of self‐reported urinary and sexual dysfunction over the last two decades: implications for comparative effectiveness research. Eur Urol 2015; 67: 1019–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Resnick MJ, Barocas DA, Morgans AK et al. Contemporary prevalence of pretreatment urinary, sexual, hormonal, and bowel dysfunction: defining the population at risk for harms of prostate cancer treatment. Cancer 2014; 120: 1263–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smith DP, King MT, Egger S et al. Quality of life three years after diagnosis of localised prostate cancer: population based cohort study. BMJ 2009; 339: b4817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Logie J, Clifford GM, Farmer RD. Incidence, prevalence and management of lower urinary tract symptoms in men in the UK. BJU Int 2005; 95: 557–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Litwin MS. Health related quality of life in older men without prostate cancer. J Urol 1999; 161: 1180–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schroeck FR, Donatucci CF, Smathers EC et al. Defining potency: a comparison of the International Index of Erectile Function short version and the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite. Cancer 2015; 113: 2687–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Symptoms and quality of life by occupational social class in men randomised in the ProtecT trial.