Abstract

Objective

To compare educational, occupational, legal, emotional, substance use disorder, and sexual-behavior outcomes in young adults with persistent and desistent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms and a local normative comparison group (LNCG) in the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA).

Method

Data were collected 12, 14, and 16 years post-baseline (mean age 24.7 years at 16 years post-baseline) from 476 participants with ADHD diagnosed at age 7–9, and 241 age- and sex-matched classmates. Probands were subgrouped on persistence vs. desistence of DSM-5 symptom count. Orthogonal comparisons contrasted ADHD vs. LNCG and Symptom-Persistent (50%) vs. Symptom-Desistent (50%) subgroups. Functional outcomes were measured with standardized and demographic instruments.

Results

Three patterns of functional outcomes emerged. Post-secondary education, times fired/quit a job, current income, receiving public assistance, and risky sexual behavior showed the most common pattern: the LNCG fared best, Symptom-Persistent ADHD worst, and Symptom-Desistent ADHD between, with largest effect sizes between LNCG and Symptom-Persistent ADHD. In the second pattern, seen with emotional outcomes (emotional lability, neuroticism, anxiety disorder, mood disorder) and substance use outcomes, the LNCG and Symptom-Desistent ADHD did not differ, but both fared better than Symptom-Persistent ADHD. In the third pattern, noted with jail time (rare), alcohol use disorder (common), and number of jobs held, group differences were not significant. The ADHD group had 10 deaths compared to one in the LNCG.

Conclusion

Adult functioning after childhood ADHD varies by domain and is generally worse when ADHD symptoms persist. It is important to identify factors and interventions that promote better functional outcomes.

Keywords: ADHD, adult outcomes, follow-up, MTA, functional outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Controlled prospective follow-up studies of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) generally document significantly worse adult educational, occupational, social, and emotional impairment than in matched non-ADHD controls.1–5 Previous prospective follow-up studies of children with ADHD have also indicated that adult outcome is not uniform, with many having continuing symptoms and impairment, some being severely functionally impaired while others (about 30%) functioning comparably to matched controls.1–7 What characterizes these different subgroups is not always clear.

Recent reports3,7 have suggested functional outcome differences between participants with persisting vs. desisting ADHD symptoms. However, persistence of ADHD symptoms in these studies is not always optimally defined8 and small sample sizes make subgrouping on symptom persistence difficult.

The seven-site MTA study followed 579 children aged 7–9 with systematically diagnosed (using DSM-IV criteria via parent DISC and teacher reports) ADHD (combined-type) and 258 age- and sex-matched classmates without ADHD comprising a Local Normative Comparison Group (LNCG). Assessments were performed at 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 years post-baseline. This provides a highly diverse,9 representative, generalizable sample,10 and the largest to date.

DSM-5 symptom-count criteria for adults from multiple informants on the Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS)11 were used to define persistence of symptoms. The diagnostic properties of the CAARS vs. DISC were compared and the CAARS was superior in its diagnostic specificity and sensitivity.8 Evaluating functional outcomes in many domains (educational, occupational, legal, emotional, substance use, and sexual behavior) can provide a comprehensive view of the long-term impairments of ADHD vs. LNCG groups and between ADHD subgroups with persistent vs. desistent symptoms.

We formulated two hypotheses based on previous MTA follow-ups12 and the accumulated literature:1–4 (a) adults with childhood-diagnosed ADHD will be significantly worse than the LNCG on multiple functional outcomes; (b) ADHD cases with continuation of symptoms (symptom persistence) will have worse outcomes in multiple functional domains than those with symptom remission (symptom desistence).

METHOD

Sample

The MTA was originally designed to evaluate effects of treatments in a 14-month randomized clinical trial of 579 children (7–9.9 years old) assigned to 4 conditions: systematic medication management, multicomponent behavioral treatment, their combination, and treatment as usual in community care. After this treatment-by-protocol phase, the MTA continued as a naturalistic follow-up study. At the first follow-up (2 years post-baseline), the LNCG – 289 classmates (258 without ADHD) matched on age and sex– was added when the ADHD participants were 9–12 years old. Follow-up assessments continued during childhood (3 years post-baseline), throughout adolescence (6, 8, and 10 years post-baseline), and into adulthood (12, 14, and 16 years post-baseline). Age range in adulthood was 19–28 years (mean=24.7). Written informed consent was obtained with procedures approved by local IRBs. Overall retention in adulthood (assessed at least once in the three adult assessments) was 476/579 (82%) for the ADHD group and 241/258 (93%) for the non-ADHD LNCG. Similar to adolescent attrition,12 participants lost at 16-year follow-up had, at baseline, significantly lower family income, younger maternal age, less maternal and paternal education, more paternal mental health problems, lower IQs, and higher teacher-rated ADHD and Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) scores than those retained.

Measurement

At age 18 and after, the Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS)11 and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children – Parent version (DISC-P)13 and Young Adult version (DISC-YA)13, instruments documented to have good reliability and validity, were completed by participants and parents. We used the oldest adult assessment point (12, 14, or 16 years) at which data were available. For the educational domain, we analyzed participant report of current educational attainment. Within the occupational domain, number of jobs, average job length, times fired or quit, current income, and public assistance status were chosen a priori. Military service counted as employment. Within the emotional functioning domain, the Impulsivity/Emotional Lability subscale of the CAARS (participant and parent report) and the Neuroticism subscale of the NEO-Five-Factor Inventory (participant report)14 were analyzed. We also examined past-year presence of any of eight DSM anxiety disorders or three DSM mood disorders from the DISC-YA. Within the substance use domain, participant report of DSM-IV substance use disorder in the past year from the DISC-YA included Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD), Marijuana Use Disorder (MUD), ‘other Substance Use Disorder’ (other SUD), including cocaine and hallucinogens, and ‘any Substance Use Disorder’ (any SUD), excluding nicotine. Within the legal domain, participant report of police contact (yes/no) and jail time (yes/no) during the past two years were analyzed. Within the sexual behavior domain, four outcomes were derived from the MTA Health Information and Demographic Survey: age of first sexual intercourse, number of sexual partners, number of pregnancies fathered or experienced by age 18, and number of offspring. Deaths were reported by site staff on a retention/attrition form.

Determination of ADHD Symptom Persistence

DSM-5 symptom-count criteria, i.e., 5 symptoms reported either by the participant or the parent in either the Inattention and/or Hyperactive-Impulsive domain on the CAARS, identified the symptom-persistent ADHD group. Symptom desistence was defined as neither ADHD domain threshold being exceeded by either source. In 23 cases in which self-report suggested no symptoms and parent report was missing, the case was excluded due to concerns of symptom under-reporting by participants.3,15 The rate of symptom persistence under this definition was 50% (n = 226), with symptom desistence characterizing the remaining 50% (n = 227). Impairment, though measured, was not used to define symptom persistence/desistence because functional outcomes, which reflect levels of impairment, are the focus of this paper.

Analyses

We used orthogonal comparisons to evaluate differences across multiple adult functional outcomes, comparing childhood diagnosis (ADHD vs. LNCG) and persistence subgroups of ADHD (Symptom Persistence vs. Symptom Desistence). Age at outcome assessment was covaried to adjust for “opportunity time” for educational attainment and number of jobs, sexual partners, pregnancies, etc. For binary outcomes, we used binary logistic regressions; for dimensional outcomes, linear regressions. Poisson regressions were used for non-normal distributions (e.g., number of offspring). The CAARS DSM-IV Hyperactive-Impulsive Symptom subscale was a covariate for analysis of the Impulsivity/Emotional Lability subscale to partial out impulsivity from emotional lability. We used the Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) method to correct for multiple comparisons within each domain.16 All analyses were repeated, separately covarying for SES (income) and initial conduct disorder.

RESULTS

Educational Outcomes

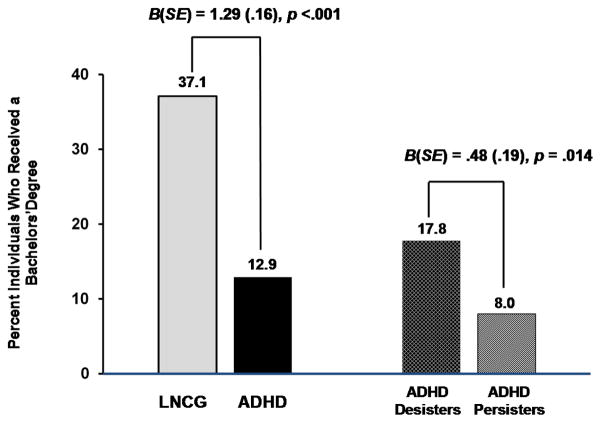

Overall, the LNCG had higher educational attainments than participants with ADHD (Table S1, available online). The majority of ADHD participants (61.7%) had a high school degree or less while the majority of LNCG participants completed at least some college (60.8%). Showing a stepwise pattern, 37.1% of the LNCG obtained a Bachelor’s degree compared to 17.8% (OR=2.7) of the Symptom-Desistent subgroup, and 8.0% of the Symptom-Persistent subgroup (OR=7.4) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Educational outcomes. ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; LNCG = local normative comparison group.

Occupational Outcomes

In four of five analyses, the ADHD group differed significantly from the LNCG (number of jobs since previous assessment was not different) (Table 1). Effect sizes were small for average job length, number of times fired/quit since last assessment, and current income, but large for percentage receiving public assistance: 16.0% of ADHD participants vs. 3.2% of LNCG participants. For comparisons of the ADHD subgroups, a stepwise pattern emerged for the three significant outcomes: the subgroup with Symptom Persistence showed the worst outcomes and the LNCG participants the best (effect sizes were always largest between these two groups), with the Symptom-Desistent subgroup intermediate. Most group differences were statistically significant at p<.05 after correcting for multiple comparisons, but effect sizes were small (up to d =.41), except for receipt of public assistance in the past year (OR=8.7), for which Symptom Persistence =22.2%, LNCG=3.2%, and Symptom Desistence fell between at 9.6%.

Table 1.

Occupational Outcomes

| LNCG (L) | ADHD | Ba (SE) | p | ADHD Symptoms | Ba (SE) | p | ΔR2 | Effect Sizesb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desistence (D) | Persistence (P) | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | D-L | P-L | P-D | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Work History | ||||||||||||

| Number of jobsc | 2.1(1.3) | 2.2(1.6) | .08(.12) | .495 | 2.3(1.6) | 2.1(1.6) | .20(.14) | .151 | .004 | .11 | .03 | .13 |

| Avg. job lengthc | 422(325) | 381(341) | 60.14(27.4) | .028 e | 410(389) | 351(291) | 59.1(31.8) | .063 | .012 | .03 | .23 | .17 |

| Times fired/quitc | .32(.64) | .61(1.06) | .29(.07) | <.001e | .47(.78) | .70(1.17) | .24(.08) | .005e | .033 | .20 | .40 | .23 |

| Past year income | 4.0(2.20) | 3.4(1.8) | .81(.15) | <.001e | 3.6(1.7) | 3.2(1.7) | .44(.17) | .011e | .046 | .19 | .41 | .26 |

| Public assistanced | 3.2% | 16.0% | 1.69(.42) | <.001e | 9.6 % | 22.2% | .98(.30) | .001e | .122 | 3.2 | 8.7 | 2.7 |

Note. ΔR2 is the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by contrasts between local normative comparison group (LNCG), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) desistence and ADHD persistence after controlling for participant age. For categorical dependent variables, the Nagelkerke R2 is reported.

Betas presented in absolute value format.

Effect sizes for continuous dependent variables are Cohen’s d, calculated using a pooled standard deviation weighted by group size. Effect sizes for categorical dependent variables are odds ratios.

Since last assessment or high school, whichever is more recent.

Currently receiving public assistance or not, reported as a percentage who are. B coefficients are log-odds estimates from logistic regression.

Indicates that the contrast is statistically significant after applying the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate correction for multiple comparisons.

Emotional Outcomes

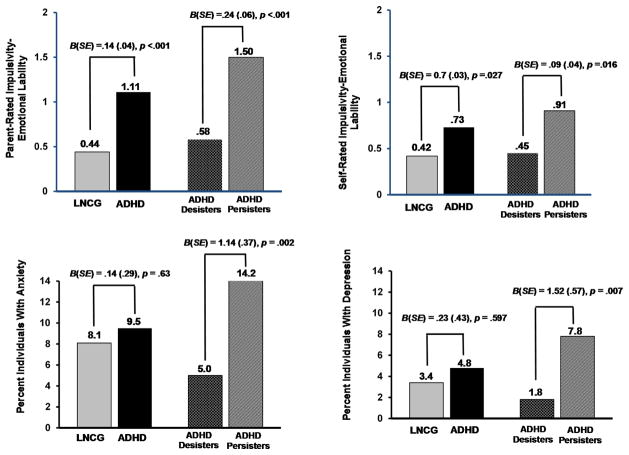

The ADHD group scored significantly worse than the LNCG on Impulsivity/Emotional-Lability (self- and parent-report) and Neuroticism, but not rates of mood or anxiety disorders (Table S2, available online). The Symptom-Persistent subgroup scored worse on Impulsivity/Emotional Lability (self- and parent-report) and Neuroticism, and endorsed higher rates of mood (7.8 % vs. 1.8%, OR=4.58) and anxiety disorders (14.2% vs. 5.0%, OR=3.12), than the Symptom-Desistent subgroup, which exhibited outcomes similar to the LNCG (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Emotional outcomes. Note: ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; LNCG = local normative comparison group.

Legal Outcomes

Participants with ADHD (13.6%) were more likely (p=.028) to report police contact than the LNCG (9.4%), but this difference was no longer significant after controlling for multiple comparisons (Table 2). Jail time did not differ significantly. Symptom-Persistent and Desistent subgroups did not differ significantly on any legal outcome.

Table 2.

Legal and Substance Use Outcomes

| LNCG (L3) | ADHD | Ba (SE) | p | ADHD Symptoms | Ba (SE) | p | ΔR2 | Effect Sizesb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desistence (D) | Persistence (P) | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| % | % | % | % | D-L | P-L | P-D | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Legal | ||||||||||||

| Any police contact | 9.4 | 13.6 | .58(.26) | .028c | 13.3 | 13.7 | .06(29) | .844 | .014 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| Jail Time | 2.3 | 3.6 | .56(.50) | .259 | 3.9 | 3.3 | .15(.51) | .765 | .008 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 0.9 |

| Substance Use | ||||||||||||

| AUD | 20.4 | 20.3 | .07(.21) | .734 | 20.4 | 20.2 | .03(.24) | .886 | <.001 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| MUD | 12.3 | 20.1 | .44(.24) | .070 | 14.7 | 26.7 | 1.05(.26) | <.001d | .055 | 1.1 | 2.6 | 2.3 |

| Other SUD | 2.1 | 4.8 | .29(.59) | .621 | 1.9 | 8.3 | 2.32(.76) | .002d | .100 | 0.8 | 4.3 | 5.5 |

| Any SUD | 26.0 | 33.1 | .26(.19) | .157 | 28.7 | 38.5 | .61(.21) | .004d | .023 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

Note. ΔR2 is the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by contrasts between local normative comparison group (LNCG), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) desistence and ADHD persistence after controlling for participant age. The Nagelkerke R2 is reported. “Other SUD” (where SUD is substance use disorder) includes such substances as cocaine and hallucinogens; “Any SUD” includes alcohol use disorder (AUD), marijuana use disorder (MUD), and Other SUD.

Betas presented in absolute value format.

Effect sizes are odds ratios.

Indicates that the contrast is statistically non-significant after applying the Benjamini-Hockberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons.

Indicates contrast is statistically significant after applying the Benjamini-Hockberg FDR correction for multiple comparisons.

Substance Use Outcomes

The LNCG and ADHD groups did not differ significantly on any substance use measures (Table 2). The Symptom-Persistent subgroup displayed higher rates of MUD (26.7 % vs. 14.7%, p < .001), ‘other SUD’ (8.3% vs. 1.9%, p = .002) and ‘any SUD’ (38.5% vs. 28.7%, p = .004) than the Symptom-Desistent subgroup, which exhibited similar rates to the LNCG. The Symptom-Persistent subgroup was 2.6 times as likely as the LNCG to meet criteria for the MUD diagnosis, and 4.3 times as likely to have an ‘other SUD’.

Sexual Behavior Outcomes

All four ADHD-LNCG comparisons were significant: ADHD was associated with younger age at first intercourse, more sexual partners, increased risk of pregnancy, and greater number of offspring by age 18, covarying age (Table 3). Probands reported more multiple offspring (6.9% vs. 1.7% for LNCG). The Symptom-Persistent subgroup was significantly different from the Symptom-Desistent subgroup on age of first intercourse and marginally different on number of partners, but not risk of early pregnancy or number of offspring. Effect sizes were small/medium.

Table 3.

Sexual Behavior Outcomes

| LNCG (L) | ADHD | Ba (SE) | p | ADHD Symptoms | Ba (SE) | p | ΔR2 | Effect Sizesb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desistence (D) | Persistence (P) | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | D-L | P-L | P-D | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Age first intercourse | 17.2(2.3) | 16.3(2.6) | 1.31(.24) | <.001d | 16.6(2.6) | 16.0(2.5) | .55(.240) | .037d | .019 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| # of Partners | 9.45(13.3) | 15.7(25.0) | 7.96(2.1) | <.001d | 13.5(18.1) | 17.8(30.0) | 4.4(2.1) | .052 | .006 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Pregnancy by 18c | 3.7% | 9.1% | 1.05(.41) | .030d | 7.2 % | 11.0 % | .47(.36) | .256 | .004 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| # of Offspring | .113(.37) | .298(.67) | -1.07(.26) | <.001d | .249(.57) | .348(.77) | .330(.18) | .067 | .005 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

Note. ΔR2 is the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by contrasts between local normative comparison group (LNCG), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) desistence and ADHD persistence after controlling for participant age. For categorical dependent variables, the Nagelkerke R2 is reported.

Betas presented in absolute value format.

Effect sizes for continuous dependent variables are Cohen’s d, calculated using a pooled standard deviation weighted by group size. Effect sizes for categorical dependent variables are odds ratios.

Categorical dependent variable. Percentages are reported instead of means and standard deviations. B coefficients are log-odds estimates from logistic regression.

Indicates that the contrast is statistically significant after applying the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate correction for multiple comparisons.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses for all outcomes covaried SES (income) and initial conduct disorder separately (details are available in Supplement 1, available online). These did not alter the results except that job length was no longer significant after covarying conduct disorder, and risk of pregnancy and self-reported impulsivity-emotional lability on the CAARS were no longer significant when income was covaried.

Deaths

Although not statistically significant, the group comparison is striking, with 10 deaths in the ADHD group (3 suicides, 4 homicides, 2 driving-under-the-influence accidents, 1 hit-and-run) versus one LNCG death (suicide).

DISCUSSION

The MTA, with 579 childhood-diagnosed, combined-type ADHD participants and 258 sex- and age-matched comparison participants without ADHD, provides the largest sample of prospectively-followed young adults to date; it is very ethnically and socioeconomically diverse, and thus by and large generalizable to an ADHD (combined-subtype) population. However, one needs to keep in mind that the subjects lost to follow-up (18% of the ADHD sample) were characterized by lower family income and parental education, more parental mental health problems, lower participant IQ, higher ADHD scores and higher rates of ODD than those retained. Because these are risk factors for poorer outcome, it is possible that a higher proportion of ADHD subjects would have had more negative outcomes had these subjects been retained.

The large sample size allowed comparison not only of the ADHD vs. LNCG groups but also of subgroups of ADHD participants defined by persistence vs. desistence of symptoms into early adulthood. Symptom persistence was defined by DSM-5 symptom criteria for adults, making it clinically relevant and permitting comparison with other outcome studies.

Our findings extend those of previous studies by showing three patterns of outcomes. The most common pattern is characterized by the LNCG group having the best outcomes, the Symptom-Persistent ADHD subgroup the worst, and the Symptom-Desistent subgroup falling between them. Obtaining a Bachelor’s degree, times fired/quit a job, current income, receiving public assistance, and risky sexual activity all followed this pattern, with moderate to large effect sizes between the LNCG and Symptom-Persistent ADHD groups, and smaller effect sizes between Symptom-Desistent ADHD and the other two groups. This pattern shows that continuing ADHD symptoms have a significant negative impact on educational, occupational, and sexual functional domains by adulthood. Even if ADHD symptoms desist, however, the negative impact of earlier ADHD symptoms can still be seen, though the functional effects are less marked. It appears important both to treat continuing symptoms of ADHD and to focus on improving these functional outcomes early.

In the second pattern, the LNCG and Symptom-Desistent ADHD group did not differ significantly but both functioned significantly better than the Symptom-Persistent ADHD group. This pattern was seen for emotional lability, neuroticism, anxiety and mood disorders, and substance use disorders. In this pattern, persistent ADHD symptoms continue to have a significant negative impact on emotional and substance use domains, but past ADHD symptoms do not appear to have a residual effect as found in the first pattern. Here, when ADHD symptoms desist, the functioning of young adults with previous ADHD approaches that of the comparison participants. This pattern illustrates the value of differentiating Symptom-Persistent vs. -Desistent ADHD subgroups in examining functioning and outcome. Persisting symptoms of ADHD may contribute to SUD risk either directly (e.g., impulsive decision-making) or indirectly (e.g., poor coping skills)17 or as a misguided attempt at self-medication. Moreover, Barkley and Fisher (2010)3 linked emotional impulsivity to persistence of ADHD symptoms in adulthood, and Swanson et al. (2014)7 linked poor response inhibition to increased self-harm in women with ADHD. Thus, continuing to treat ADHD symptoms to “remission” and not just “improvement” is clinically important because current symptom remission appears somewhat protective against anxiety, depression, and SUD.

In the third pattern, no significant differences were noted among the three groups. Number of jobs held, alcohol use disorder, and jail time followed this pattern. Notably, the number of jobs held was not significantly different across groups although the times fired/quit, current income and receiving public assistance were significantly worse for the Symptom-Persistent subgroup. Possibly, with less education, greater emotional lability, and more SUD, this subgroup found it more difficult to find another job after being fired or impulsively quitting, such that the number of jobs held did not differ despite shorter job length. In fact, the increased use of public assistance suggests more time unemployed in the Symptom-Persistent subgroup. Details of work history and unemployment will be explored in depth in a future paper.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) was not higher for the ADHD vs. LNCG. Overall levels of AUD are high at this age18 which, coupled with social impairments that predict less drinking for some with ADHD,19 may explain our findings for alcohol. The illegal nature of marijuana use (at the time these data were collected) may partly be driving our findings due to the oft-cited contribution of conduct problems to ADHD-related risk of SUD. Issues related to self-control and impulsivity as well as self-medication for hyperactive-impulsive symptoms are also often implicated in marijuana use.20,21 More research is needed as the societal context of this drug changes. Similarly, incarcerations were rare and did not differ across the groups, possibly because the young adults may have been considered first time offenders and not generally given jail time early on.

Our findings on the comparison of LNCG and ADHD groups are similar to other long-term prospective controlled follow-up studies.2–5,22 These studies all showed that adults who had childhood ADHD are more impaired, relative to comparison participants, in educational, occupational, and emotional domains. Some studies also showed similar findings for sexual behavior,3 whereas others did not.2 Mixed findings have also been reported for substance use.2,3,22

Several studies6,7 have suggested a minority of children with ADHD have early adult outcomes comparable to children without ADHD. It may well be that these groups are characterized by ADHD symptom desistence. Generally, anxiety and mood disorder rates were not elevated in our ADHD group compared to the LNCG, but were higher in the Symptom-Persistent subgroup, and thus more tightly linked to current ADHD symptoms than to history of ADHD. Similar findings were reported in some previous adult ADHD outcome studies.2,4 However, other studies3,22 reported high rates of mood disorders in adults with ADHD compared to matched comparison participants. These discrepancies across studies may, once again, be a function of the proportion of Symptom Persisters vs. Desisters in their ADHD samples. Participant age, as well as time frame (lifelong, current, or past 6 months) and locations of such investigations could also account for different findings.

Few studies have explored the differences in multiple outcome areas in adulthood between ADHD subjects for whom symptoms persisted vs. desisted vs. a non-ADHD comparison group. Our large sample size allowed for these comparisons, providing insight into which functional areas are related to earlier ADHD symptoms, e.g., educational, occupational, and sexual behavior domains, and which are particularly influenced by current symptomatology, e.g., SUD and emotional domains.

The large number of deaths in the ADHD group compared to the LNCG is striking (10 vs. 1) though it does not reach statistical significance. The higher death rates in participants with ADHD have also been documented in other follow-up studies,2,4 and alert us to the possible increased early mortality via accidents, suicides, or homicides in the ADHD population.

The association of persistence of ADHD symptoms and negative adult outcomes is clear. However, we should point out that the persistence group also has more comorbidity, e.g., anxiety, depression, MUD, and these comorbidities may also be contributing to negative outcomes. A recent paper by Roy et al.23 explored childhood factors that may be associated with or contribute to persistence of ADHD symptoms in adulthood. Important predictive factors included baseline initial ADHD symptom severity, parental mental health, and parenting practices. Caye et al.24 identified severity of ADHD, treatment and comorbid conduct disorder and major depression as important predictors of persistence of ADHD into adulthood.

A large, diverse, fairly representative sample and a matched local normative comparison group with a respectable retention rate are all strengths of the study. Whenever possible, standardized validated age-appropriate measures were used, with more than one informant. Clinically relevant DSM-5 symptom criteria were used to distinguish symptom persistence and desistence ADHD subgroups. Finally, sensitivity analyses covaried all results separately on SES (income) and initial conduct disorder, which did not significantly alter most results, suggesting these factors were not responsible for the differences we documented.

In the young adult follow-up period, the participants themselves were the principal informants of functional outcomes. Their reports may not have been completely accurate or objective because self-report biases are not uncommon in this population.25 However, more objective sources may also have flaws. Police records and other official records are often the “tip of the iceberg,” as many acts are either not detected or not officially reported.26 Furthermore, parents become less knowledgeable about certain aspects of the young adult’s life as their children age. Thus, conducting thorough assessments for adults with ADHD remains challenging.

DSM-5 symptom criteria were used to define symptom persistence and desistence subgroups because of clinical relevance and future comparisons but alternative definitions (e.g., clinician gold standard) may offer additional insights. The contributions of psychiatric comorbidities both as predictors and as correlated outcomes are important areas that are being explored in other papers.

Another limitation is that personality disorders, particularly antisocial personality disorders, were not evaluated as outcomes. It is thus unclear if this diagnosis differed in the persistent, desistent and LNCG groups, although other studies4 clearly suggest that antisocial personality disorder and symptom persistence often coexist.

Effects of treatment on outcome were not specifically explored in this paper as this was addressed in detail by Swanson et al (submitted for review).27 In that paper, the authors showed that there were no treatment group differences after 3 year follow-up. Furthermore, after 14 months, all participants went to the community for treatment, where there may have been self-selection biases and documented less than optimal medication treatment.9 Lastly, there is a marked decline in medication use in adolescence and adulthood with only 3–10% of the subjects using medication, often very intermittently.

A final limitation is that the LNCG was recruited at 2 years rather than initially. It is unclear whether this would impact study results as the LNCG group were matched for age and sex, and attended the same schools.

This study extends previous longitudinal studies of ADHD by documenting three different patterns of adult outcomes. The most common, seen in educational, occupational, and sexual/reproductive domains, was characterized by LNCG participants functioning best, Symptom-Persistent ADHD participants worst, and Symptom-Desistent ADHD participants between. Thus, some important outcomes are influenced additively by both current symptoms and residual effects of past symptoms.

In the second pattern, seen with emotional lability, neuroticism, anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders, the LNCG and Symptom-Desistent ADHD group did not differ significantly, and both were significantly better than the Symptom-Persistent ADHD group. This suggests that some negative outcomes are linked mainly to residual symptoms, so symptoms need to be treated to “remission” not just “improvement.”

The third pattern showed no significant differences among the three groups on number of jobs, AUD and jail time, probably due mainly to very high or very low frequency.

These findings suggest that functional outcomes in adults who were diagnosed with ADHD in childhood are not uniform but differ across domains, giving rise to different patterns of outcomes. The persistence or desistence of ADHD symptomatology in adulthood appears to influence these patterns of outcomes. Thus, both ADHD symptoms and functioning need to be targets of appropriate, innovative, and ongoing intervention in this chronic condition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work reported was supported by cooperative agreement grants and contracts from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to: University of California–Berkeley: U01-MH50461, N01MH12009, and HHSN271200800005-C; DA-8-5550; Duke University: U01-MH50477, N01MH12012, and HHSN271200800009-C; DA-8-5554; University of California–Irvine: U01MH50440, N01MH12011 and HHSN271200800006- C; DA-8-5551; Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene (NY State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University): U01-MH50467, N01-MH12007, and HHSN271200800007-C; DA-8-5552; Long Island–Jewish Medical Center: U01-MH50453; New York University: N01MH 12004 and HHSN271200800004-C; DA-8-5549; University of Pittsburgh: U01 MH50467, N01 MH 12010, and HHSN271200800008-C; DA-8-5553 and DA039881; McGill University: N01MH12008 and HHSN271200800003-C; DA-8-5548. Funding support for Dr. Mitchell was provided by NIDA K23-DA032577.

The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA) was an NIMH cooperative agreement randomized clinical trial, continued under an NIMH contract as a follow-up study and finally under a NIDA contract. Collaborators from NIMH: Benedetto Vitiello, MD (Child and Adolescent Treatment and Preventive Interventions Research Branch), Joanne B. Severe, MS (Clinical Trials Operations and Biostatistics Unit, Division of Services and Intervention Research), Peter S. Jensen, MD (currently at REACH Institute and the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences), L. Eugene Arnold, MD, MEd (currently at Ohio State University), Kimberly Hoagwood, PhD (currently at Columbia); previous contributors from NIMH to the early phases: John Richters, PhD (currently at National Institute of Nursing Research); Donald Vereen, MD (currently at NIDA). Principal investigators and co-investigators from the sites are: University of California, Berkeley/San Francisco: Stephen P. Hinshaw, PhD (Berkeley), Glen R. Elliott, PhD, MD (San Francisco); Duke University: Karen C. Wells, PhD, Jeffery N. Epstein, PhD (currently at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center), Desiree W. Murray, PhD; previous Duke contributors to early phases: C. Keith Conners, PhD (former PI); John March, MD, MPH; University of California, Irvine: James Swanson, PhD, Timothy Wigal, PhD; previous contributor from UCLA to the early phases: Dennis P. Cantwell, MD (deceased); New York University: Howard B. Abikoff, PhD; Montreal Children’s Hospital/McGill University: Lily Hechtman, MD; New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University/Mount Sinai Medical Center: Laurence L. Greenhill, MD (Columbia), Jeffrey H. Newcorn, MD (Mount Sinai School of Medicine); University of Pittsburgh: Brooke Molina, PhD, Betsy Hoza, PhD (currently at University of Vermont), William E. Pelham, PhD (PI for early phases, currently at Florida International University). Follow-up phase statistical collaborators: Robert D. Gibbons, PhD (University of Illinois, Chicago); Sue Marcus, PhD (Mt. Sinai College of Medicine); Kwan Hur, PhD (University of Illinois, Chicago). Original study statistical and design consultant: Helena C. Kraemer, PhD (Stanford University). Collaborator from the Office of Special Education Programs/US Department of Education: Thomas Hanley, EdD. Collaborator from Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention/Department of Justice: Karen Stern, PhD.

Footnotes

Supplemental material cited in this article is available online.

Disclosures:

Dr. Hechtman has received research support, served on advisory boards, and served as a speaker for Eli Lilly and Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Ortho-Janssen, Purdue, Shire, and Ironshore.

Dr. Arnold has received research funding from Curemark, Forest, Eli Lilly and Co., Neuropharm, Novartis, Noven, Shire, YoungLiving, NIH, Autism Speaks, and Supernus; has consulted with or been on advisory boards for Arbor, Gowlings, Neuropharm, Novartis, Noven, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Seaside Therapeutics, Sigma Tau, Shire, Tris Pharma, and Waypoint; and has received travel support from Noven.

Dr. Jensen has received unrestricted educational grants from Shire, Inc., has served as a consultant to Shire, Inc., and is a shareholder of an evidence-based practices consulting company (CATCH Services, LLC).

Drs. Swanson, Sibley, Owens, Mitchell, Molina, Hinshaw, Abikoff, Perez Algorta, Howard, Hoza, Lakes, Mss. Stehli, Etcovitch, Houssais, and Mr. Nichols report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr. Lily Hechtman, Division of Child Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal Children’s Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Dr. James M. Swanson, Child Development Center, School of Medicine, University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Margaret H. Sibley, Florida International University, Miami.

Ms. Annamarie Stehli, University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Elizabeth B. Owens, Institute of Human Development, University of California, Berkeley.

Dr. John T. Mitchell, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

Dr. L. Eugene Arnold, Ohio State University, Nisonger Center, Columbus.

Dr. Brooke S.G. Molina, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Dr. Stephen P. Hinshaw, University of California, Berkeley.

Dr. Peter S. Jensen, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, and The REACH Institute, New York.

Dr. Howard B. Abikoff, Child Study Center at New York University Langone Medical Center, New York.

Dr. Guillermo Perez Algorta, Division of Health Research, Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK.

Dr. Andrea L. Howard, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Dr. Betsy Hoza, University of Vermont, Burlington.

Ms. Joy Etcovitch, McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, Quebec.

Ms. Sylviane Houssais, McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, Quebec.

Dr. Kimberley D. Lakes, University of California, Irvine.

Mr. J. Quyen Nichols, University of Vermont, Burlington.

References

- 1.Cherkasova M, Mongia M, Errington T, Ponde M, Hechtman L. Clinical Management of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. London: Future Medicine Ltd; 2013. Long-term outcome in ADHD and its predictors; pp. 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss G, Hechtman LT. Hyperactive Children Grown up: ADHD in Children, Adolescents, and Adults. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barkley RA, Murphy KR, Fischer M. ADHD in Adults: What the Science Says. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein RG, Mannuzza S, Olazagasti MAR, et al. Clinical and functional outcome of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder 33 years later. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:1295–1303. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuriyan AB, Pelham WE, Jr, Molina BSG, et al. Young adult educational and vocational outcomes of children diagnosed with ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41(1):27–41. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9658-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: adaptive functioning in major life activities. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:192–202. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000189134.97436.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swanson EN, Owens EB, Hinshaw SP. Pathways to self-harmful behaviors in young women with and without ADHD: A longitudinal examination of mediating factors. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(5):505–515. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sibley MH, Swanson JM, Arnold LE, et al. Defining ADHD Symptom Persistence in Adulthood: Optimizing Sensitivity and Specificity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12620. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MTA Cooperative Group. A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(12):1073–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens J, Kelleher K, Greenhouse J, et al. Empirical evaluation of the generalizability of the sample from the multimodal treatment study for ADHD. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34:221–32. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connors C, Erhardt D, Sparrow E. Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales: CAARS. Toronto: MHS; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molina BSG, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, et al. The MTA at 8 years: prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:484–500. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819c23d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone M. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costa P, Jr, McCrae RR. Neo Personality Inventory Revised (neo-Pi-R) and Neo Five-Factor Inventory (neo-Ffi) Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, et al. Diagnosing ADHD in adolescence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(1):139–150. doi: 10.1037/a0026577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molina BSG, Pelham WE. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Risk of Substance Use Disorder: Developmental Considerations, Potential Pathways, and Opportunities for Research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:607–639. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molina BSG, Walther CAP, Cheong J, Pedersen SL, Gnagy EM, Pelham WE. Heavy alcohol use in early adulthood as a function of childhood ADHD: Developmentally specific mediation by social impairment and delinquency. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;22:110–121. doi: 10.1037/a0035656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance-use disorders: findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elkins IJ, McGue M, Iacono WG. Prospective effects of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, and sex on adolescent substance use and abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1145–1152. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biederman J, Petty CR, Woodworth KY, Lomedico A, Hyder LL, Faraone SV. Adult outcome of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a controlled 16-year follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:941–950. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roy A, Hechtman L, Arnold LE, et al. Childhood factors affecting persistence and desistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in adulthood: results from the MTA. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55:xx–xx. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caye A, Spadini AV, Karam RG, et al. Predictors of persistence of ADHD into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Mar 28; doi: 10.1007/s00787-016-0831-8. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Owens JS, Goldfine ME, Evangelista NM, Hoza B, Kaiser NM. A critical review of self-perceptions and the positive illusory bias in children with ADHD. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2007;10(4):335–351. doi: 10.1007/s10567-007-0027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loeber R, Farrington DP. Young children who commit crime: Epidemiology, developmental origins, risk factors, early interventions, and policy implications. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12(04):737–762. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swanson JM, Sibley MH, Hechtman L, et al. Outcomes in the 16-year Follow-up of the Multimodal Treatment Study of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (MTA): Persistence of Symptoms and Medication Side Effects in Early Adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. Revised and resubmitted. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.