Abstract

A tumor vasculature that is functionally abnormal results in irregular gradients of metabolites and drugs within the tumor tissue. Recently, significant efforts have been committed to experimentally examine how cellular response to anti-cancer treatments varies based on the environment in which the cells are grown. In vitro studies point to specific conditions in which tumor cells can remain dormant and survive the treatment. In vivo results suggest that cells can escape the effects of drug therapy in tissue regions that are poorly penetrated by the drugs. Better understanding how the tumor microenvironments influence the emergence of drug resistance in both primary and metastatic tumors may improve drug development and the design of more effective therapeutic protocols. This chapter presents a hybrid agent-based model of the growth of tumor micrometastases and explores how microenvironmental factors can contribute to the development of acquired resistance in response to a DNA damaging drug. The specific microenvironments of interest in this work are tumor hypoxic niches and tumor normoxic sanctuaries with poor drug penetration. We aim to quantify how spatial constraints of limited drug transport and quiescent cell survival contribute to the development of drug resistant tumors.

Keywords: Anticancer drug resistance, Hypoxic niche, Drug sanctuary, Tumor microenvironment, Agent-based model

1. Introduction

There is an ongoing discussion about the origin of anti-cancer drug resistance [1,13,25,47]. Clinically, drug resistance is defined as a reduced effectiveness of treatment during or after the course of therapy. As a result, a cancer can progress even months or years after treatment, leading to tumor recurrence. Currently, no pretreatment tests or analyses can predict whether or not a particular patient will develop resistance.

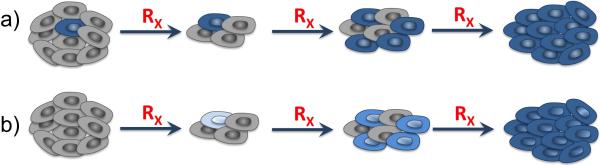

Further, the contribution of two potential modes of resistance – pre-existing and acquired – is also challenging to determine. The term pre-existing resistance refers to the fact that, before the therapy is applied, the tumor may harbor some cells or cell clones that will not respond to the treatment. These cells are passively selected by the therapy, expand and overtake the population of non-resistant cells. In contrast, acquired resistance means that all cells are initially sensitive to the treatment, and that mechanisms of resistance develop during the therapy. The cells will then become progressively more tolerant to the drug as a result of treatment, and the end result is similar to what occurs in the case of pre-existing resistance: the population of non-resistant cells is overtaken by resistant ones. (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematics of the development of pre-existing and acquired drug resistance in tumor tissue under continuously administered treatment. (a) In the pre-existing resistance case, the resistant cells are selected for and overgrow the sensitive cells. (b) In the acquired resistance case, the cells progressively acquire resistance as a result of being exposed to the drug. The final outcome in both cases is a resistant tumor, which makes it difficult to determine what mechanism(s) of resistance a given tumor possesses.

In this chapter we will concentrate on the case of drug resistance that is induced by treatment (acquired resistance). Many experimental results support the idea that cancer cells may harbor the potential to acquire a variety of drug-resistance mechanisms activated in response to therapy [23,50,57,60]. In the in vitro experiment described in [57], a lung cancer cell line was exposed to a targeted therapy, and a small population of cells that remained alive was subsequently cultured in the presence of that drug for a year. This created a handful of “persister” cells that survived a prolonged drug exposure with almost no population growth. These cells attained protection from lethal drug levels and, finally, gained ability to proliferate in spite of the drug. The extensive screening of drug-tolerant cell colonies that arose from persister cells revealed that they exhibit diverse resistance mechanisms. This experiments showed that heterogeneous resistance mechanisms can emerge in cells derived from the same cell line and exposed to identical selective pressures. Another example is DNA damage caused by anticancer methylating agents that is typically processed by methyltransferases or directed for mismatch repair (MMR). Progressive inactivation of MMR by reducing or inhibiting the expression of repair proteins, for example under hypoxic conditions, leads to increased tumor cell tolerance to this intended damage [28]. Similarly, in the case of DNA-crosslinking cisplatin, the tumor cell may bypass cisplatin-DNA adducts by translesion synthesis polymerases [65,14].

The focus in this work is on a DNA damaging drug. The mechanism through which cancer cells could acquire resistance to such a drug arise from the natural tendency of cells to preserve their genomic integrity—even normal cells continuously fight against endogenous metabolic products and exogenous damaging compounds through various repair mechanisms. Agents damaging DNA on the level of a single base, a dinucleotide, strand crosslinks, strand breaks, or alkylating agents all activate the response from DNA damage repair machinery (DDR) [10]. DDR activates various mechanisms, such as nucleotide excision repair, base excision repair or MMR. These repair mechanisms work individually or in parallel to maintain genomic stability. Under normal conditions they should lead the cell to arrest in one of the cell cycle checkpoints that will resume only after the damage is repaired or, they should result in a permanent cell-cycle arrest and cell apoptosis if the damage is unrepairable [6]. The cytotoxic agents used in many anticancer therapies are designed to target various DNA sites with the ultimate goal to overcome repair mechanisms and lead to cell death. Nonetheless, as a part of a natural cell response to damage, cells try to escape the arrest and maintain genomic stability. Here, in addition to transcription-related DDR pathways, the replication-related DNA-damage tolerance (DDT) mechanisms are activated leaving unrepaired or misrepaired DNA modifications to be repaired later and the cell proceeds with its cell cycle [9,19]. This increases cell tolerance to accumulation of DNA damage and, although highly disadvantageous for therapeutic outcomes, such effect is commonly observed in anticancer therapies.

2. Microenvironmental Niches and Sanctuaries

It has been postulated that tumor cells can survive in dormant niches in a growth-arrested state for many years before they re-enter proliferation [17]. Tumor niches are specialized regions in tumor microenvironment that can provide required factors for tumor cell survival, and may be permissive either for tumor initiation, growth or progression to metastasis. Several kinds of microenvironmental niches have been identified and are subject of an ongoing research, among these are pre-cancerous, pre-metastatic or stem-cell niches [3,5,18,27,38,39,49,51]. Such regions allow the tumor cells to survive and maintain a quiescent state while regulating their metabolic needs and immune cell surveillance. The niche conditions can also influence specific changes in gene expression levels and can induce DNA mutations or cell differentiation mechanisms that may lead to tumor cell invasion and metastatic spread [8,20,21,40].

Tumor tissues may also contain regions that are poorly penetrated by therapeutics, forming what are termed drug-limited or pharmacologic sanctuaries [11,56]. One of the main sanctuary sites in our body is the central nervous system [48,56]. Since the blood-brain barrier (BBB) prevents tumor cells from drug exposure, the cells are able to escape the effects of drug therapy and maintain fast growth forming brain metastases. Beyond this organ-level sanctuary, the non-uniform distribution of drugs within a specific tissue can form tissue-level sanctuaries.

Multiple factors can contribute to the formation of these tissue-level sanctuaries. For instance, drug interstitial transport depends not only on physicochemical properties of the drug, but also on the structure of the extracellular matrix that may hinder drug transport, for example in regions of higher fiber density or cross-linking. Cellular architecture of the tissue may also prohibit free diffusion of drug molecules. Moreover, drug internalization may vary between individual cells. While measurements of drug concentrations in blood plasma are easy to obtain, the distribution within a tissue compartment is more difficult to quantify. Recent developments in in vivo imaging techniques now allow for the visualization of heterogeneous drug distributions within tissue, as well as the visual assessment of cells’ response to fluorescently labeled drugs or fluorescent non-therapeutic imaging agents [43,64,63,55].

In an effort to better understand the impact of drug sanctuaries, attempts have been made to quantify tumor cell response in various conditions. A comprehensive set of in vitro experiments looked at three different tumor cell lines grown in 54 homogeneous microenvironments that differed from one another in the levels of glucose and oxygen, and with diverse concentrations of the clinically used drug erlotinib [44]. Quantitative time series data were collected and subsequently used to calibrate a non-spatial stochastic branching model containing populations of drug-sensitive and drug-resistant cells. Simulations of this experimentally-calibrated model showed that the tumor microenvironment has a strong influence on tumor evolutionary dynamics under the pulsed drug administration schedule. In particular, the computational model demonstrated that under heterogeneous microenvironmental conditions there was no reduction in tumor burden. On the other hand, the same tumors in homogeneous conditions responded positively to the therapy.

Therefore, heterogeneities in the tumor microenvironment, such as tumor-associated niches and sanctuaries, may play a crucial role in tumor promotion, survival, progression, and response to therapies. Can these niches (formed due to actions of drug and/or stromal cells) and/or sanctuaries (formed as a result of limited drug penetration) that emerge within the tumor microenvironment promote anti-cancer drug resistance by enabling drug-induced tolerance? In this chapter we will address this question by studying tumor response to a simulated DNA damaging agent using a spatial agent-based model with explicit heterogeneous tissue morphology.

3. The mathematical model of the tumor and its microenvironment

In order to create a heterogeneous tumor microenvironment, we consider a small patch of tissue with four non-evolving blood vessels placed inside the tissue in an irregular pattern as shown in Figure 2. These vessels supply both oxygen and drug that subsequently diffuse through the domain and are absorbed by tumor cells. Additionally, we assume that the drug is subjected to decay due to its half-life. Tumor cells are modeled as individual entities whose behavior is modulated by both the properties inherited from their mother cells (the age at which the cells can divide, the initial tolerance to DNA damage, the amounts of accumulated drug and DNA damage), and by their immediate environment (the levels of extracellular oxygen and drug, and their interactions with the neighboring cells). For example, cell division and cell relocation can be suppressed due to lack of free space and cellular overcrowding. Another example is that cells can become dormant if they move to a tissue region with hypoxic levels of oxygen. A cell's initial viability is also inherited from its mother cell because both the DNA damage and the cell's tolerance to DNA damage are passed from a mother to both daughter cells. This model setup enables tracing of both cells’ ancestry and how the cell properties evolve upon treatment.

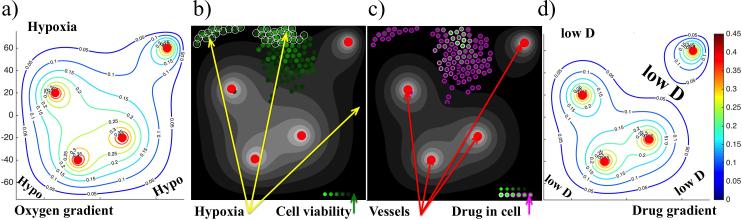

Figure 2.

Schematics of the tumor microenvironment with metabolic and drug gradients. a) oxygen supplied by four vessels (red circles) creates a gradient (color-coded contours lines) due to its diffusion through the tissue and cellular uptake—the levels of low oxygen (hypoxia) are indicated; b) the corresponding oxygen gradient (shades of gray) with hypoxic cells circled and cell viability levels (based on how much cell's DNA has been damaged) are represented by shades of green; c) the corresponding drug gradient (shades of gray) with intracellular drug accumulation represented by shades of purple; d) color-coded contours of drug gradient—the levels of low drug concentration are indicated by lowD.

A distorted tumor vasculature such as the one we are considering results in irregular gradients of metabolites. This includes significant regions of low oxygen content (hypoxia), which is often observed in animal tumors and in biomedical images used in the clinic for diagnostic purposes [31,62]. In our model, we placed blood vessels in order to create regions that contain no more than 5% of the oxygen level found in the most oxygenated areas near the blood vessels (Figure 2(a)). Since both oxygen and drug are supplied by the same vascular system, it may seem that the resulting gradients will also be similar. However, the actual levels of oxygen and drug at the same spatial location may be different since the interstitial transport of oxygen and drug depend not only on their vascular influx and interstitial diffusion, but also on cellular uptake (which may be different), and the decay in the case of the drug.

Figures 2(a) and 2(d) show contours of both extracellular gradients in the same scale. These figures indicate that the regions near the domain boundaries are hypoxic and contain low concentrations of drugs (we call such regions the hypoxic niches), and that the region in between the vessel in the top-right corner and three other vessels have normoxic levels of oxygen but low levels of the drug (we call such tissue regions the sanctuaries). Figures 2(b) and 2(c) show cellular response to the gradients in these specific tissue regions (grey-scale gradients in these figures are identical to the contours shown in Figure 2(a) and (d), respectively). In Figure 2(b) the hypoxic cells are circled, and the gradient of oxygen from Figure 2(a) is shown in the background. The same cells in Figure 2(c) are color-coded according to the accumulated levels of drug, and the extracellular gradient of the drug from Figure 2(d) is shown in the background. The cells that were recently born are colored in light purple, since they inherited half of the drug accumulated in the mother cell. Upon exposure to the drug, cells accumulate damage and become less viable, which is color-coded in Figure 2(b)—the lighter the color the more viable the cell is. Note that the clusters of cells in the hypoxic areas are more viable, while the cells near the vasculature are close to reaching the DNA damage tolerance level that will result in cell death.

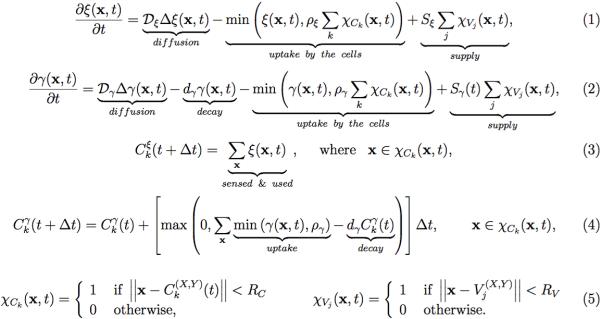

Mathematically, our modeling approach combines the off-lattice agent-based model of individual cells with physical cell-cell interactions, and the continuous description of extracellular nutrients and metabolites, as well as stiffness/viscous properties of the extracellular matrix. The temporal and spatial changes in oxygen ξ and drug γ concentrations in the interstitial space are given in equations (1) and (2). These metabolites are supplied from the vessels with the supply rates Sξ and Sγ(t), respectively. They diffuse through the extracellular space with diffusion coefficients Dξ and Dγ. They are absorbed by the cells with uptake rates ρξ and ργ. Additionally, drug decays with the decay rate dγ. Each cell Ck(t) is defined by its position Ck(X,Y)(t), and is characterized by several properties, such as current cell age Ckage(t), and cell maturation age at which the cell is ready to divide Ckmat. Moreover, cell behavior depends also on the level of sensed oxygen Ckξ(t), the amount of accumulated drug Ckγ(t), the duration of cell exposure to high drug concentration Ckexp(t), the level of accumulated damage Ckdam(t), and the level of damage that the cell can withstand without committing to death (also called the level of tolerated damage or the death threshold) Ckdeath(t). The quantity of oxygen taken up by the cell is described in equation (3), and that of drug in equation (4). Both of these metabolites are obtained from the local cell neighborhood χCk, as defined in equation (5).

Equations 1.

Continuous equations for the interstitial kinetics of oxygen (1) and drug (2); cellular uptake of the oxygen (3) and drug (4); definition of the cellular Ck and vascular Vj neighborhoods with radii RC and RV for cellular uptake and vascular supply, respectively (5).

The drug-induced damage depends on the current increase in drug consumed by the cell (drug uptake minus drug decay) and on damage repair that is proportional to the current damage with rate p (equation (6)). The damage level tolerated by the cells increases when the cell is exposed to high enough drug concentrations γexp for a prolonged time texp (equations (7)-(8)). When the cell Ck(t) divides, one of its daughter cells takes the coordinates of its mother: Ck1(X,Y)(t)=Ck(X,Y)(t), whereas the second is placed randomly near the mother cell: Ck2(X,Y)(t)= Ck(X,Y)(t)+RC(cosθ,sinθ), where RC is the cell radius. The current age of both daughter cells is set to 0, and the cell maturation age is inherited with a small noise term. The cell damage, damage tolerance and the current drug exposure time are all inherited from the mother cell. On the other hand, the level of accumulated drug is split in half between both daughter cells. Finally, the level of sensed oxygen is determined independently for each cell based on the oxygen concentration in the cell's vicinity.

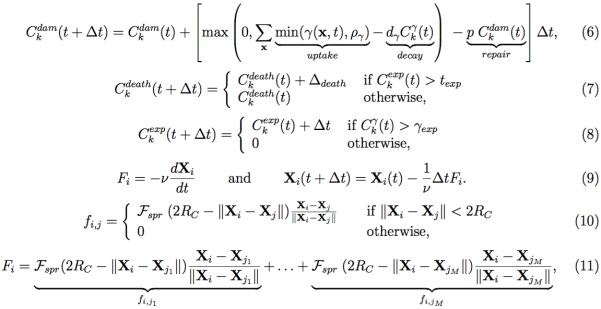

Equations 2.

Equations defining accumulation of cell damage (6), increase in cell tolerance to damage (7), and cell exposure time to the drug (8); mechanical equations of cell movement (9) determined by repulsive forces between two (10) and multiple (11) neighboring cells.

In order to keep the neighboring cells from overlapping, repulsive forces are applied as described in equation (9). These overdamped springs (ν is a damping coefficient) allow the whole multicellular system to return to equilibrium without oscillations. The repulsive forces with spring stiffness Fspr are used to move the cells apart until they reach the distance equal to cell diameter (2RC) as defined in equation (10) for two neighboring cells, and in equation (11) for multiple cells. For simplicity, we do not include other microenvironmental components, such as stromal cells and other metabolites. More details of the model, its implementation, and the parameter self-calibration can be found in [16].

4. Non-resistant tumor dynamics under treatment

In the model described here, the drug is supplied continuously from four blood vessels inside the tumor. We consider a small cluster of tumor cells, as could arise in a micrometastasis. In the case of non-resistant cells, cell tolerance to the drug-induced damage does not change in time. Thus continuous drug exposure will eventually cause each cell to accumulate a damage level in excess of the threshold, which will result in tumor eradication. The time course of tumor progression in this example is shown in Figure 3.

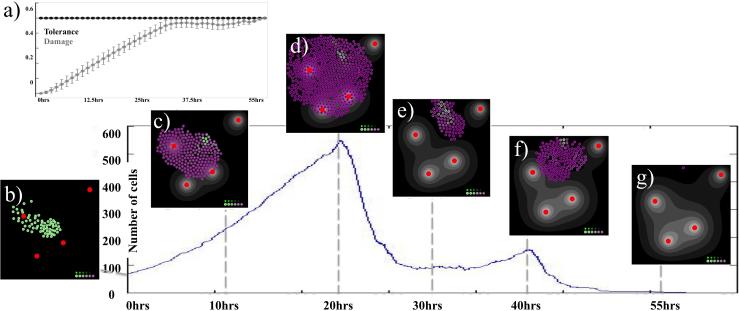

Figure 3.

Time course of non-resistant tumor progression. The curve indicates the total number of cells over time. The left-top inset (a) shows the time course in both accumulated damage (grey) and damage tolerance (black) averaged over all tumor cells at a given time (standard deviation also shown); note, that the averaged damage tolerance is constant for non-resistant cells. The insets (b-g) show tumor morphology at the specific time points with the internally accumulated drug (shades of purple).

At the initiation of the simulation there is no damage, and there is a uniform (as indicated by a standard deviation of zero) damage tolerance level of 0.5, as shown in Figure 3(a). The initial 65 cells shown in Figure 3(b) proliferate extensively while the absorbed drug leads to the accumulation of drug-induced damage—note the steady increase in the average damage levels in Figure 3(a). Cells primarily located near the vessels quickly accumulate damage levels above their tolerance level, and as a result die. Dying cells give the remaining cells space to divide, and the net result is steady tumor growth during the first 20 simulated hours (Figure 3(c)-(d)), with the tumor reaching its maximal size of 528 cells after 20 hours (Figure 3(d)). The newly divided cells are indicated by a light purple color, since daughter cells inherit half of the drug accumulated by the mother cell.

Most of the newly divided cells are located on the rim of the tumor cluster. However, during the 20 hours of drug exposure, many cells have accumulated such high levels of damage that they rapidly died after that time (Figure 3(e)). At 30 hours, a small cluster of surviving cells is located in the area of low drug content (the tissue sanctuary) that allows for a short rebound in tumor growth between 30 and 40 hours (Figure 3(f)). During this time, the DNA damage averaged over the total number of cells is very close to the value of cell tolerance to DNA damage shown in Figure 3(a) (note, that for the non-resistant tumor the tolerance to DNA damage is identical for all cells and is constant in time). However, the accumulated damage of the 153 surviving cells after 40 hours is very high and the whole tumor is eradicated within 55 hours (Figure 3(g)). In Figure 3(a) this is confirmed by the close proximity of both averaged curves over this time with, finally, the damage curve intersecting the damage tolerance curve at the time when all tumor cells die.

5. Tumor dynamics with acquired resistance under the treatment

In contrast to the non-resistant case in which tumor cells have a constant tolerance, in the case of acquired resistance the tolerance of individual cells to DNA damage can increase as a result of prolonged drug exposure. The cells can still die when they are damaged beyond the tolerance threshold, but cell fate depends on whether or not the cell tolerance level grows faster than the level of cell damage. The time course of tumor progression when the individual cells can acquire resistance to the drug (at rate 9.5×10−5 per iteration) is shown in Figure 4. The initial 65 cells seen in Figure 4(a) proliferate extensively, reaching about 800 cells in 115 hours as shown in Figure 4(b). Note that the non-resistant tumor was completely eradicated in less than half of this time. This indicates that cell tolerance levels, at least in some cells, have increased above the level of non-resistant cells leading to a 10-fold expansion of the tumor.

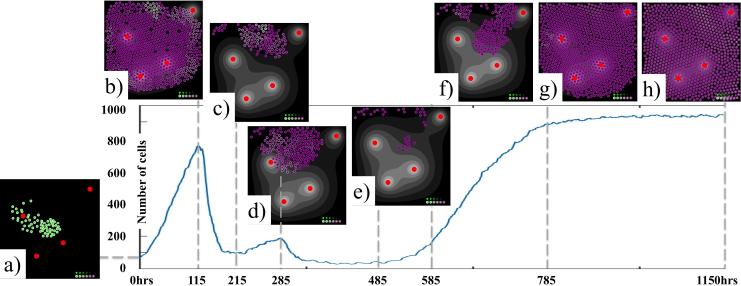

Figure 4.

Time course of progression of a tumor with acquired resistance. The curve indicates the total number of cells over time. The insets (a-h) show tumor morphology at the specific time points with the internally accumulated drug (shades of purple).

Although tolerance levels are increasing in many cells, it has not necessarily increased fast enough for a subpopulation of the cells to evade death. In fact, a large subpopulation of tumor cells has died, and the tumor shrunk to about 100 cells in 215 hours, as shown in Figure 4(c). In the next period of time it is evident that a competition between increasing cell tolerance to the drug-induced damage and increasing cell DNA damage due to the drug exposure takes place. This is evidenced by fluctuations in tumor size: the tumor grows to about 200 cells in next 70 hours (shown in Figure 4(d)), and then rapidly retreats to about 30 cells. This small cell population is located in the hypoxic niches, in which drug concentrations are negligible. As a result, no significant damage is induced in these dormant cells, yet the cells can continue to repair DNA damage. With lower cell damage and increased tolerance, these cells expand 5-fold in a short amount of time when the local oxygenation changes slightly (e-f). Since the damage and tolerance properties are passed to the daughter cells, the tumor is able to avoid complete eradication. While individual cells can still die, the tumor as a whole overtakes the available tissue space – it reaches about 950 cells Figure 4(g), and remains at that size for the rest of the simulation as shown in Figure 4(h).

6. Development of a drug resistant tumor

The lack of tumor shrinkage at the end of the simulation shown in Figure 4 does not directly imply that the tumor became resistant. However, here we prove that the tumor in Figure 4 is resistant to the simulated DNA damaging agent by analyzing tumor cell viability. In our model cell viability is defined as how close the level of accumulated damage is to reaching the level of damage that the cell can tolerate (damage tolerance minus damage accumulated). In case of the non-resistant tumor shown in Figure 3, the tolerance level was the same for every cell and constant during the entire simulation. Thus, with the increase of drug-induced damage, cell viability was continually decreasing, eventually leading to death of the whole tumor.

In the case of the resistance-acquiring tumor shown in Figure 4, cell tolerance to damage can be amplified for each cell independently in response to the local drug concentration (i.e., damage tolerance is no longer constant). Therefore, for a tumor to be resistant, its tolerance to damage has to increase faster than the accumulated damage (on average). In this way, the average cell viability would eventually become a monotonically increasing function in time. Figure 5 graphically shows changes in tumor viability (Figure 5(a)), and changes in the viability of each individual cell during the same simulation as shown in Figure 4. Each vertical cylinder in Figure 5(b-f) represents a cell and is placed spatially where the cell is found within the tissue (red cylinder represent the vessels). The height of the cylinder is equal to the cell viability; that is, the height represents difference between cell tolerance level and cell damage level. Thus the lower the cylinder is, the closer the cell is to death. The taller the cylinder, the larger the gap between cell damage and the tolerance level, and the more viable the cell is.

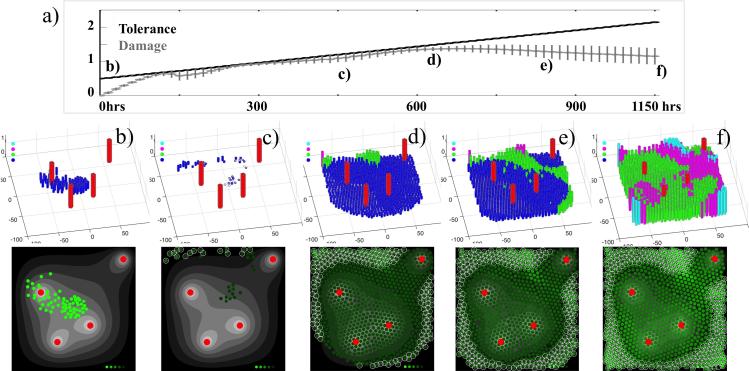

Figure 5.

Cell viability graphs showing the emergence of a resistant tumor. (a) The averaged levels of cell tolerance to damage (black) and cell accumulated damage (grey) shown over 1150 hours of simulated time. The vertical lines indicate standard deviations. (b-f) Five snapshots showing individual cell viability levels defined as a difference between cell tolerance to damage and cell damage; top row: color-coded from blue (low viability) to green, to magenta, to cyan (high viability); bottom row: the corresponding images show cells which viability is color-coded from light green (more viable cells) to dark green (less viable cells). Circled cells represent cells hypoxic cells, and red cylinders and circles represent four vessels.

The cell viability plots in Figure 5 help us to study the emergence of drug resistance. The initial 65 cells shown in Figure 5(b) have no damage, and all cylinders have a height equal to the non-resistant damage tolerance level. However, upon exposure to the drug the damage level in most cells increases at a faster rate than their tolerance levels increase. Therefore most of cells die, leaving only a small population of viable cells Figure 5(c), the same as in Figure 4(e). As it has been shown in Figure 4(f), the cells in hypoxic regions have negligible exposure to the drug, thus cell damage does not increase for these cells, and the cell damage repair is relatively more effective leading to increased viability. This is illustrated by the taller green cylinders in Figure 5(d), again with a taller height being indicative of an increase in cell viability. This is also illustrated by lighter green cells in the corresponding image in the bottom row of Figure 5. Note that these more tolerant cells are located within the hypoxic region. Subsequently, it is visible in Figure 5(e) that cells with increased viability are located along an off-diagonal region between the vessel in the right top corner and the three remaining vessels. Lower levels of drug and low but normoxic levels of oxygen characterize this region, and represent common features of a tissue sanctuary, where drug penetration is limited.

The remaining cells, indicated by blue cylinders in Figure 5(f), are sensitive to the drug and die, leaving space for the more tolerant cells to divide. With time, this allows the population of more tolerant cells to expand. This is clearly indicated in the time course plot in Figure 5(a) in which we observe a progressively increasing divergence between the averaged damage tolerance and the average accumulated damage (compare Figure 5(e) and (f)). Since the disparity between two curves (and therefore, the cell viability) is continuously increasing, we interpret that as the emergence of acquired drug resistance. Moreover, in this particular case chemotherapy could not overcome acquired resistance. While individual cells can still be killed by the DNA damaging drug, the tumor as a whole survives and becomes nonresponsive to the drug.

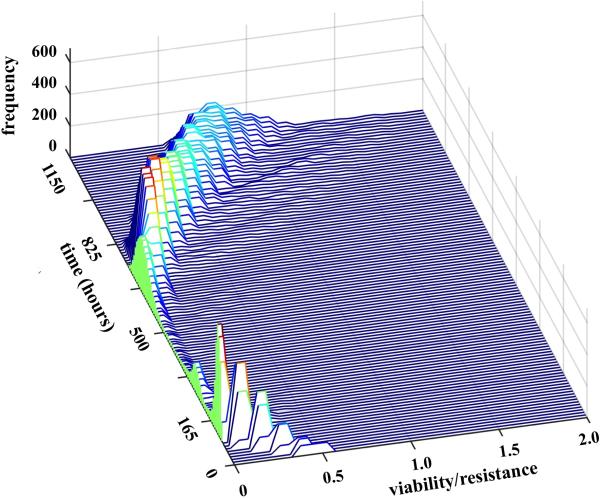

Our observations are further confirmed by the histogram surface of cell viability shown in Figure 6. Here, for the consecutive time points (from 0 to 1150 hours) we constructed the histograms for cell viability with centers from 0.1 to 2.0 in intervals of 0.1. At the beginning of the simulation all cells had viability of 0.5. At early times, the viability of a large fraction of cells decreases (is in the range 0.1-0.5) due to increased drug-induced cell damage. However, with more time, cell viability increased in a majority of cells, and the fraction of cells with low viability drastically decreased (after 825 hours, there are no cells with near zero viability). Again, the trend of increasing cell viability indicates that the tumor cells individually and as a whole population acquired resistance to the drug.

Figure 6.

Histogram surface of cell viability (with values between 0 and 2) recorded over the time of 1150 hours (with frequency of 15 hours). Initially, cell viability is diminished due to damage induced by the drug, leading to significant tumor reduction (between 165 and 500 hours); however, at the later stages (after 825 hours), there is a steady increase in cell viability leading to tumor resistance.

7. Tissue Niches and Sanctuaries and their Relation to Resistance

Model simulations presented in this chapter showed that two tumor regions play an important role in the emergence of drug resistance - one with a low content of oxygen and drug (a hypoxic niche), and a second with limited drug penetration, but normoxic oxygenation (a tumor sanctuary). In particular, we have shown that when the tumor cells reach hypoxic niches they attain a dormant, non-proliferative state, which allowed them to overcome accumulated damage due to still active DNA repair mechanisms. Some such “persister” cells in our simulation were able to survive for more than 80 hours. Our computational study also pointed to tissue sanctuaries in which tumor cells are protected from lethal effects of the drug. We showed that in these regions the tolerance to drug-induced damage is rising faster than the damage itself, which, in turn, leads the cells to acquire drug resistance.

While the concept of a tissue sanctuary has previously been reported in cancer biology, it was mostly used in reference to metastatic brain sanctuaries that arise due to the blood brain barrier [48,56] and bone marrow sanctuaries that arise due to their protective structure [12,41]. Recently, this concept of drug sanctuaries has been adopted in the context of acquired drug resistance [15]. In this work the authors argued that, in contrast to the belief that the development of resistance is caused by genetic heterogeneity, spatial heterogeneity in drug concentrations can be a driving force in the emergence of drug resistance. They showed that resistance is likely to arise in cells found in sanctuaries with poor drug penetration, and later these cells can invade non-sanctuary compartments. They also suggested that cell migration may be pivotal to this process, and that a certain combination of cell migration rate and spatial heterogeneity level can accelerate the development of resistance. Although our model does not include migration, the fact that resistance arises in low-drug sanctuaries and can later result in resistance in high-drug regions is consistent with our findings.

The concept of dormant persister tumor cell phenotype has been reported experimentally [23,50,57,60], though not in hypoxic niches. In in vitro experiments, dormant persister tumor cells were able to survive treatment for a long time before gaining the ability to grow and proliferate in the presence of drug. Moreover, the surviving clones acquired various drug-induced resistance mechanisms. This has an important clinical application. The fact that they can survive in treatment for a prolonged time and develop various forms of resistance indicates that novel approaches should be developed towards exploiting vulnerabilities of such drug-tolerant persister cells. If such persister cells are not removed or suppressed, the typical anti-cancer chemotherapy will lead to the emergence of heterogeneously resistant persister-derived clones instead of leading to tumor eradication.

8. Summary and Outlook

The work presented in this chapter is a more detailed analysis of one particular example from the model developed by us in [16]. We considered a tumor with a parameter Δdeath (defining how cell tolerance to drug-induced damage is changing) equal to 9.5×10−5, which we previously showed to be in a parameter regime that results in the emergence of a drug resistant tumor. As first discovered in [16] and detailed here, hypoxic niches and low drug sanctuaries play a very important role in the dynamics of acquired drug resistance.

However, in [16] we also showed that the microenvironment plays a less significant role in the tumor dynamics when resistance to the drug is pre-existing. In the pre-existing resistance case, a certain (small) population of tumor cells was not responsive to the drug even before the treatment was applied. We demonstrated that a simplified, spatially-invariant version of this model can predict long-term tumor response (tumor eradication, survival of only drug resistant clones, complete treatment failure) when resistance is preexisting, indicating that the spatial (microenvironmental) considerations are not a key driving force in long-term dynamics. This occurs because the inherent fitness advantage that the cells with pre-existing resistance possess in the presence of drug can dominate (in the long-term) over any spatial considerations. In contrast for the acquired resistance case, the dynamics predicted by the spatially-invariant model are vastly different than those predicted by the full spatial model [16]. These differences point to the key role of niches and sanctuaries in treatment dynamics when drug resistance is acquired.

It is worth noting that in the recent years, various mathematical approaches have been developed to model drug resistance. Most of them deal with resistance on a whole tumor cell population level and they usually do not incorporate any components of tumor microenvironment. If the microenvironment is incorporated, it is typically treated as a homogeneous medium. Some excellent overviews of such methods can be found in [7,13,29,30,34,54], and in our previous publications [16,59]. There are only a few mathematical models that deal with microenvironmental heterogeneity in the context of chemotherapy and drug resistance, using either agent-based approaches [42,52,53,61] or continuous equations [22,26,35,37].

There is also an increasing interest in developing experimental and computational methods, to predict a tumor's potential for drug resistance before it emerges. We recently postulated a concept of Virtual Clinical Trials to assess tumor chemoresistance based on patient-specific biopsy data and computer simulations of therapeutic treatments [58]. While it is difficult and costly to perform extensive scheduling experiments in a laboratory, it is relatively easy and inexpensive to run large numbers of computational simulations to test various dosing and timing schedules of mono- and multi-drug therapies. Of particular interest is whether a specifically designed treatment schedules would be able to prevent or delay the development of acquired drug resistance. Moreover, following findings described in this chapter, it is of interest to investigate whether such protocols would limit the survival or proliferation of persister cells, and the development of tissue sanctuaries. For instance, response to various treatment protocols including maximum tolerated dose, metronomic and fractioned, has been studied in the model described herein. It was found that for micrometastases that harbor pre-existing resistant cells (up to a certain level of resistance) and for those that can acquire resistance in response to drug (up to a certain rate), a small number of fractioned dose protocols proved to be optimal in limiting (and in some cases, preventing) the emergence of drug resistant micrometastases [59].

While here we specifically consider drug resistance in tumors, there are parallels to therapy resistance in populations of bacteria cells [2,32,33]. In particular, it has been experimentally shown that the emergence of bacterial antibiotic resistance was accelerated in heterogeneous microenvironments [66]. Further, various strains of bacteria were shown to possess the capability to actively form niches to adapt to different environments, such as changes in nutrient availability [45]. It is also worth noting that the concept of persister cells was first described in the context of bacterial infections in which a small number of antibiotic-resistant mutants survived in a dormant non-dividing state [4,36]. For bacteria, several factors such as growth stage [46], anaerobic adaptation [24], toxin–antitoxin modules as well as a number of genes and pathways [67], have been identified to be linked to persister formation.

However, in contrast to bacteria, it is not known how cancer persister cells arise. Nor is it known how the various mechanisms of resistance that have been observed experimentally can emerge in cell colonies arising from individual persisters. While it is likely that any adaptation strategies of drug-tolerant mother cells are passed along to daughter cells, why cancer persister cells remain dormant for months and what makes them finally leave the dormant state, has yet to be identified. More detailed investigations at the single cell level, such as tracking cell lineages to recreate different evolutionary dynamics: clonal, spatial, and pharmacological may shed light on these aspects (subject of ongoing work). Of particular interest is to correlate spatial dynamics of single cells and cell populations with the pre-existing and emerging microenvironmental niches and sanctuaries

The importance of the microenvironment in tumor initiation, growth, invasion and metastasis is now well appreciated. The role that the microenvironment plays in tumors response to therapies and in the development of anti-treatment resistance is currently under intense investigation, both experimentally and mathematically. In this chapter we presented a scenario in which tumor cells can gain drug resistance in specific microenvironmental conditions, namely tissue niches and sanctuaries. However, it is still an open question whether the tumor cells that acquired drug resistance happened to reach these specific environments, were actively adapting to these new conditions, or were actively engaged in microenvironment remodeling. Understanding the ways in which tumor cell communities thrive in heterogeneous microenvironments and their strategies for surviving under extreme stress can be used for the development of new therapeutic treatments that target or control these interactions instead of directly targeting the cells themselves. This can pave new directions for research in cancer biology.

Acknowledgments

This work was initiated during the Woman in Applied Mathematics (WhAM!) Research Collaboration Workshop at the Institute of Mathematics and Its Applications (IMA). KAR was supported in part by the U01 CA202229-01 grant from the National Institute of Health. The Bavarian State Ministry of Education and Culture, Science and Arts joint with the Technical University of Munich provided funding for JPV through the Laura Bassi Award. JPV also wants to thanks the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) for providing a travel grant (CE 243/1-1) to facilitate the initiation of this cooperation.

Contributor Information

Judith Pérez-Velázquez, Mathematical Modeling of Biological Systems, Centre for Mathematical Science, Technical University of Munich, Garching, Germany, cerit@ma.tum.de.

Jana L. Gevertz, Department of Mathematics and Statistics, The College of New Jersey, Ewing, NJ, USA, gevertz@tcnj.edu

Aleksandra Karolak, Integrated Mathematical Oncology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, Tampa, FL, USA, Aleksandra.Karolak@moffitt.org.

Katarzyna A. Rejniak, Integrated Mathematical Oncology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, Tampa, FL, USA, Department of Oncologic Sciences, College of Medicine, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA, Kasia.Rejniak@moffitt.org

References

- 1.Baguley BC. Multiple drug resistance mechanisms in cancer. Molecular biotechnology. 2010;46(3):308–316. doi: 10.1007/s12033-010-9321-2. doi:10.1007/s12033-010-9321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baquero F, Coque TM, de la Cruz F. Ecology and evolution as targets: the need for novel eco-evo drugs and strategies to fight antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(8):3649–3660. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00013-11. doi:10.1128/AAC.00013-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Lyden D, Wang TC. The evolution of the cancer niche during multistage carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(7):511–518. doi: 10.1038/nrc3536. doi:10.1038/nrc3536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bigger JW. Synergic action of penicillin and sulphathiazole on Bacterium typhosum. Lancet. 1946;1(6386):81–83. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(46)91224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borovski T, De Sousa EMF, Vermeulen L, Medema JP. Cancer stem cell niche: the place to be. Cancer Res. 2011;71(3):634–639. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3220. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branzei D, Foiani M. Regulation of DNA repair throughout the cell cycle. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2008;9(4):297–308. doi: 10.1038/nrm2351. doi:10.1038/nrm2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brocato T, Dogra P, Koay EJ, Day A, Chuang YL, Wang Z, Cristini V. Understanding Drug Resistance in Breast Cancer with Mathematical Oncology. Curr Breast Cancer Rep. 2014;6(2):110–120. doi: 10.1007/s12609-014-0143-2. doi:10.1007/s12609-014-0143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmeliet P, Dor Y, Herbert JM, Fukumura D, Brusselmans K, Dewerchin M, Neeman M, Bono F, Abramovitch R, Maxwell P, Koch CJ, Ratcliffe P, Moons L, Jain RK, Collen D, Keshert E. Role of HIF-1alpha in hypoxia-mediated apoptosis, cell proliferation and tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 1998;394(6692):485–490. doi: 10.1038/28867. doi:10.1038/28867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang DJ, Cimprich KA. DNA damage tolerance: when it's OK to make mistakes. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5(2):82–90. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.139. doi:10.1038/nchembio.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung-Ong K, Giaever G, Nislow C. DNA-damaging agents in cancer chemotherapy: serendipity and chemical biology. Chemistry & biology. 2013;20(5):648–659. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.04.007. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cory TJ, Schacker TW, Stevenson M, Fletcher CV. Overcoming pharmacologic sanctuaries. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2013;8(3):190–195. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32835fc68a. doi:10.1097/COH.0b013e32835fc68a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.David E, Blanchard F, Heymann MF, De Pinieux G, Gouin F, Redini F, Heymann D. The Bone Niche of Chondrosarcoma: A Sanctuary for Drug Resistance, Tumour Growth and also a Source of New Therapeutic Targets. Sarcoma. 2011;2011:932451. doi: 10.1155/2011/932451. doi:10.1155/2011/932451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foo J, Michor F. Evolution of acquired resistance to anti-cancer therapy. Journal of theoretical biology. 2014;355:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.02.025. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedberg EC. Suffering in silence: the tolerance of DNA damage. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2005;6(12):943–953. doi: 10.1038/nrm1781. doi:10.1038/nrm1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu F, Nowak MA, Bonhoeffer S. Spatial heterogeneity in drug concentrations can facilitate the emergence of resistance to cancer therapy. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11(3):e1004142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004142. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gevertz JL, Aminzare Z, Norton KA, Perez-Velazquez J, Volkening A, Rejniak KA. Emergence of Anti-Cancer Drug REsistance Exploring the Importance of the Microenvironmental Niche via a Spatial Model. In: Radunskaya A, Jackson T, editors. Applications of Dynamial Systems in Biology and Medicine. Vol. 158. Springer; 2015. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghajar CM. Metastasis prevention by targeting the dormant niche. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(4):238–247. doi: 10.1038/nrc3910. doi:10.1038/nrc3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghajar CM, Peinado H, Mori H, Matei IR, Evason KJ, Brazier H, Almeida D, Koller A, Hajjar KA, Stainier DY, Chen EI, Lyden D, Bissell MJ. The perivascular niche regulates breast tumour dormancy. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(7):807–817. doi: 10.1038/ncb2767. doi:10.1038/ncb2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghosal G, Chen J. DNA damage tolerance: a double-edged sword guarding the genome. Translational cancer research. 2013;2(3):107–129. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-676X.2013.04.01. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2218-676X.2013.04.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilkes DM, Semenza GL, Wirtz D. Hypoxia and the extracellular matrix: drivers of tumour metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(6):430–439. doi: 10.1038/nrc3726. doi:10.1038/nrc3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordan JD, Bertout JA, Hu CJ, Diehl JA, Simon MC. HIF-2alpha promotes hypoxic cell proliferation by enhancing c-myc transcriptional activity. Cancer cell. 2007;11(4):335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.006. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greene J, Lavi O, Gottesman MM, Levy D. The impact of cell density and mutations in a model of multidrug resistance in solid tumors. Bull Math Biol. 2014;76(3):627–653. doi: 10.1007/s11538-014-9936-8. doi:10.1007/s11538-014-9936-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hata AN, Niederst MJ, Archibald HL, Gomez-Caraballo M, Siddiqui FM, Mulvey HE, Maruvka YE, Ji F, Bhang HE, Krishnamurthy Radhakrishna V, Siravegna G, Hu H, Raoof S, Lockerman E, Kalsy A, Lee D, Keating CL, Ruddy DA, Damon LJ, Crystal AS, Costa C, Piotrowska Z, Bardelli A, Iafrate AJ, Sadreyev RI, Stegmeier F, Getz G, Sequist LV, Faber AC, Engelman JA. Tumor cells can follow distinct evolutionary paths to become resistant to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition. Nat Med. 2016;22(3):262–269. doi: 10.1038/nm.4040. doi:10.1038/nm.4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hemsley CM, Luo JX, Andreae CA, Butler CS, Soyer OS, Titball RW. Bacterial drug tolerance under clinical conditions is governed by anaerobic adaptation but not anaerobic respiration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(10):5775–5783. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02793-14. doi:10.1128/AAC.02793-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holohan C, Van Schaeybroeck S, Longley DB, Johnston PG. Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(10):714–726. doi: 10.1038/nrc3599. doi:10.1038/nrc3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson TL, Byrne HM. A mathematical model to study the effects of drug resistance and vasculature on the response of solid tumors to chemotherapy. Math Biosci. 2000;164(1):17–38. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(99)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaplan RN, Psaila B, Lyden D. Niche-to-niche migration of bone-marrow-derived cells. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13(2):72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.12.003. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karran P. Mechanisms of tolerance to DNA damaging therapeutic drugs. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22(12):1931–1937. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.12.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Komarova NL, Wodarz D. Drug resistance in cancer: principles of emergence and prevention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(27):9714–9719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501870102. doi:10.1073/pnas.0501870102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Komarova NL, Wodarz D. Stochastic modeling of cellular colonies with quiescence: an application to drug resistance in cancer. Theor Popul Biol. 2007;72(4):523–538. doi: 10.1016/j.tpb.2007.08.003. doi:10.1016/j.tpb.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koong AC, Mehta VK, Le QT, Fisher GA, Terris DJ, Brown JM, Bastidas AJ, Vierra M. Pancreatic tumors show high levels of hypoxia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48(4):919–922. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00803-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korolev KS, Xavier JB, Gore J. Turning ecology and evolution against cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(5):371–380. doi: 10.1038/nrc3712. doi:10.1038/nrc3712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambert G, Estevez-Salmeron L, Oh S, Liao D, Emerson BM, Tlsty TD, Austin RH. An analogy between the evolution of drug resistance in bacterial communities and malignant tissues. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(5):375–382. doi: 10.1038/nrc3039. doi:10.1038/nrc3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavi O, Gottesman MM, Levy D. The dynamics of drug resistance: a mathematical perspective. Drug Resist Updat. 2012;15(1-2):90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2012.01.003. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lavi O, Greene JM, Levy D, Gottesman MM. The role of cell density and intratumoral heterogeneity in multidrug resistance. Cancer Res. 2013;73(24):7168–7175. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1768. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis K. Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(1):48–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1557. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorz A, Lorenzi T, Clairambault J, Escargueil A, Perthame B. Modeling the effects of space structure and combination therapies on phenotypic heterogeneity and drug resistance in solid tumors. Bull Math Biol. 2015;77(1):1–22. doi: 10.1007/s11538-014-0046-4. doi:10.1007/s11538-014-0046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu H, Clauser KR, Tam WL, Frose J, Ye X, Eaton EN, Reinhardt F, Donnenberg VS, Bhargava R, Carr SA, Weinberg RA. A breast cancer stem cell niche supported by juxtacrine signalling from monocytes and macrophages. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(11):1105–1117. doi: 10.1038/ncb3041. doi:10.1038/ncb3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu P, Weaver VM, Werb Z. The extracellular matrix: a dynamic niche in cancer progression. J Cell Biol. 2012;196(4):395–406. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102147. doi:10.1083/jcb.201102147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luoto KR, Kumareswaran R, Bristow RG. Tumor hypoxia as a driving force in genetic instability. Genome integrity. 2013;4(1):5. doi: 10.1186/2041-9414-4-5. doi:10.1186/2041-9414-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meads MB, Hazlehurst LA, Dalton WS. The bone marrow microenvironment as a tumor sanctuary and contributor to drug resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(9):2519–2526. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2223. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Menchon SA. The effect of intrinsic and acquired resistances on chemotherapy effectiveness. Acta Biotheor. 2015;63(2):113–127. doi: 10.1007/s10441-015-9248-x. doi:10.1007/s10441-015-9248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minchinton AI, Tannock IF. Drug penetration in solid tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(8):583–592. doi: 10.1038/nrc1893. doi:10.1038/nrc1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mumenthaler SM, Foo J, Choi NC, Heise N, Leder K, Agus DB, Pao W, Michor F, Mallick P. The Impact of Microenvironmental Heterogeneity on the Evolution of Drug Resistance in Cancer Cells. Cancer Inform. 2015;14(Suppl 4):19–31. doi: 10.4137/CIN.S19338. doi:10.4137/CIN.S19338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ni L, Yang S, Zhang R, Jin Z, Chen H, Conrad JC, Jin F. Bacteria differently deploy type-IV pili on surfaces to adapt to nutrient availability. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes. 2016;2 doi: 10.1038/npjbiofilms.2015.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nierman WC, Yu Y, Losada L. The In vitro Antibiotic Tolerant Persister Population in Burkholderia pseudomallei is Altered by Environmental Factors. Frontiers in microbiology. 2015;6:1338. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01338. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.01338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oxnard GR. The cellular origins of drug resistance in cancer. Nat Med. 2016;22(3):232–234. doi: 10.1038/nm.4058. doi:10.1038/nm.4058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palmieri D, Chambers AF, Felding-Habermann B, Huang S, Steeg PS. The biology of metastasis to a sanctuary site. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(6):1656–1662. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2659. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peinado H, Lavotshkin S, Lyden D. The secreted factors responsible for pre-metastatic niche formation: old sayings and new thoughts. Semin Cancer Biol. 2011;21(2):139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.01.002. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pisco AO, Huang S. Non-genetic cancer cell plasticity and therapy-induced stemness in tumour relapse: 'What does not kill me strengthens me'. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(11):1725–1732. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.146. doi:10.1038/bjc.2015.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Plaks V, Kong N, Werb Z. The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16(3):225–238. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Powathil GG, Adamson DJ, Chaplain MA. Towards predicting the response of a solid tumour to chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatments: clinical insights from a computational model. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9(7):e1003120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003120. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Powathil GG, Gordon KE, Hill LA, Chaplain MA. Modelling the effects of cell-cycle heterogeneity on the response of a solid tumour to chemotherapy: biological insights from a hybrid multiscale cellular automaton model. Journal of theoretical biology. 2012;308:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.05.015. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Powathil GG, Swat M, Chaplain MA. Systems oncology: towards patient-specific treatment regimes informed by multiscale mathematical modelling. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;30:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.02.003. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Primeau AJ, Rendon A, Hedley D, Lilge L, Tannock IF. The distribution of the anticancer drug Doxorubicin in relation to blood vessels in solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 11 (24 Pt 1):8782-8788. 2005 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1664. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Puhalla S, Elmquist W, Freyer D, Kleinberg L, Adkins C, Lockman P, McGregor J, Muldoon L, Nesbit G, Peereboom D, Smith Q, Walker S, Neuwelt E. Unsanctifying the sanctuary: challenges and opportunities with brain metastases. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(5):639–651. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov023. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nov023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramirez M, Rajaram S, Steininger RJ, Osipchuk D, Roth MA, Morinishi LS, Evans L, Ji W, Hsu CH, Thurley K, Wei S, Zhou A, Koduru PR, Posner BA, Wu LF, Altschuler SJ. Diverse drug-resistance mechanisms can emerge from drug-tolerant cancer persister cells. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10690. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10690. doi:10.1038/ncomms10690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rejniak KA, Lloyd MC, Reed DR, Bui MM. Diagnostic assessment of osteosarcoma chemoresistance based on Virtual Clinical Trials. Med Hypotheses. 2015;85(3):348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2015.06.015. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shah AB, Rejniak KA, Gevertz JL. Limiting the development of anti-cancer drug resistance in a spatial model of micrometastases. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2016038. https://arxivorg/abs/160103412 under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Sharma SV, Lee DY, Li B, Quinlan MP, Takahashi F, Maheswaran S, McDermott U, Azizian N, Zou L, Fischbach MA, Wong KK, Brandstetter K, Wittner B, Ramaswamy S, Classon M, Settleman J. A chromatin-mediated reversible drug-tolerant state in cancer cell subpopulations. Cell. 2010;141(1):69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.027. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Silva AS, Gatenby RA. A theoretical quantitative model for evolution of cancer chemotherapy resistance. Biol Direct. 2010;5:25. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-5-25. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-5-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun JD, Liu Q, Wang J, Ahluwalia D, Ferraro D, Wang Y, Duan JX, Ammons WS, Curd JG, Matteucci MD, Hart CP. Selective tumor hypoxia targeting by hypoxia-activated prodrug TH-302 inhibits tumor growth in preclinical models of cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(3):758–770. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1980. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thurber GM, Yang KS, Reiner T, Kohler RH, Sorger P, Mitchison T, Weissleder R. Single-cell and subcellular pharmacokinetic imaging allows insight into drug action in vivo. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1504. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2506. doi:10.1038/ncomms2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vinegoni C, Dubach JM, Thurber GM, Miller MA, Mazitschek R, Weissleder R. Advances in measuring single-cell pharmacology in vivo. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20(9):1087–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.05.011. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Waters LS, Minesinger BK, Wiltrout ME, D'Souza S, Woodruff RV, Walker GC. Eukaryotic Translesion Polymerases and Their Roles and Regulation in DNA Damage Tolerance. Microbiol Mol Biol R. 2009;73(1):134. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00034-08. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00034-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang Q, Lambert G, Liao D, Kim H, Robin K, Tung CK, Pourmand N, Austin RH. Acceleration of emergence of bacterial antibiotic resistance in connected microenvironments. Science. 2011;333(6050):1764–1767. doi: 10.1126/science.1208747. doi:10.1126/science.1208747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang Y. Persisters, persistent infections and the Yin-Yang model. Emerging microbes & infections. 2014;3(1):e3. doi: 10.1038/emi.2014.3. doi:10.1038/emi.2014.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]